Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1044

July 5, 2012

50 years of Algerian independence

On July 5, 1962 Algeria became independent from France. 2012 marks the 50th anniversary of Algerian independence. In this video, Martin Evans, author of Algeria: France’s Undeclared War, talks about the complexities of Algerian colonial history and the country’s fight for independence.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Martin Evans is Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Portsmouth and author of Algeria: France’s Undeclared War. You can read more by Professor Evans here and here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Edmund Spenser: ‘Elizabeth’s arse-kissing poet?’

Edmund Spenser‘s innovative poetic works have a central place in the canon of English literature. Yet he is remembered as a morally flawed, self-interested sycophant; complicit in England’s ruthless colonisation of Ireland; in Karl Marx’s words: “Elizabeth’s arse-kissing poet” — a man on the make who aspired to be at court and was prepared to exploit the Irish to get what he wanted.

In the first biography of the poet for 60 years, Andrew Hadfield finds a more complex and subtle Spenser. How did a man who seemed destined to become a priest or a don become embroiled in politics? If he was intent on social climbing, why was he so astonishingly rude to the good and the great: Lord Burghley, the earl of Leicester, Sir Walter Ralegh, Elizabeth I, and James VI? Why was he more at home with ‘the middling sort’ — writers, publishers and printers, bureaucrats, soldiers, academics, secretaries, and clergymen — than with the mighty and the powerful? How did the appalling slaughter he witnessed in Ireland impact on his imaginative powers? How did his marriage and family life shape his work?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Andrew Hadfield is Professor of English at the University of Sussex and the author of Edmund Spenser: A Life (OUP, 2012). He is the author of a number of works on early modern literature, including Shakespeare and Republicanism; Literature, Travel and Colonialism in the English Renaissance, 1540-1625; Spenser’s Irish Experience: Wilde Fruyt and Salvage Soyl; and Literature, Politics and National Identity: Reformation to Renaissance. He was editor of Renaissance Studies (2006-11) and is a regular reviewer for The Times Literary Supplement. Read his previous blog post “10 facts and conjectures about Edmund Spenser.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 4, 2012

Frank Close reflects on the new boson find

Now that the boson has been found (yes, I know we physicists have to use science-speak to be cautious, but it’s real), I can stop hedging and answer the question that many have been asking me for months: how do six people who had an idea share a Nobel Prize that is limited to three? The answer is: they don’t. To paraphrase George Orwell: All may appear equal, but some are more equal than others.

A review of the original edition of The Infinity Puzzle in The Economist graciously said the following: “Mr Close’s magisterial work is sure to become the definitive account of the story. It offers no unambiguous advice to the Nobel committee. But the judges would be wise to give it a thorough read anyway.”

First and foremost, today is a triumph for engineering — the design, construction and successful operation of the most extensive complex precision instrument in history. If the new Engineering Prize that has ambitions to rival the Nobel were to honour Lyn Evans, who led the design and construction of the Large Hadron Collider, few would argue. Also, the discovery is testament to the skills of hordes of experimenters, who used this to find the nature of reality, and I addressed the problems of dealing with their recognition in The Infinity Puzzle. It is the six (sadly now five) theorists where the manouevring begins.

Higgs’ name is a household word, but he was beaten into print by Robert Brout and Francois Englert. Even they had been anticipated by two young Russian theorists: Sacha Migdal and Sacha Polyakov. The latter duo, having received negative and incorrect criticisms from some skeptical senior scientists, published nothing until after the above had done so. Gerry Guralnik, Dick Hagen and Tom Kibble, independently aware of the basic ideas around the same time and ignorant of what Brout, Englert and Higgs had done, were also scooped.

Brout sadly died in 2011, unaware that in his intellectual dreams he had glimpsed reality. Today, this leaves Englert undisputed as first to have published the mass mechanism in relativistic quantum field theory. While it is wrong to refer to the “Higgs mechanism,” the eponymous boson is fairly named as Higgs uniquely since he alone mentioned the massive boson that now carries his name. By 1966 he had noted that its decays may prove whether the mechanism is truly in Nature’s lexicon. Finally, there is the singular role of Tom Kibble.

In 1967, Kibble used the pieces of intellectual lego that he had earlier constructed with his collaborators, Guralnik and Hagen, to build the empirical model whose truth is now being revealed. He showed how the photon of the electromagnetic force stays massless, while other bosons (now realized to be the W and Z, carriers of the weak force) gain mass. Kibble’s work also inspired Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam to incorporate his ideas in the works that led to their Nobel awards in 1979. Also, as one of the Guralnik, Hagen, and Kibble team — which was so narrowly beaten to the tape in 1964 — Kibble is also special in having been involved throughout the entire construction.

As for Jeffrey Goldstone, who started all this; James Bjorken, who first showed the way; thousands of engineers who made the Large Hadron Collider the most remarkable scientific instrument in history; and the experimentalists who have used it so successfully, they all have touched the mystery of knowing Nature. The solution to the infinity puzzle is now becoming clear. But of the theorists who wrote papers in 1964, showing how the carriers of the fundamental forces gain mass, Englert, Higgs, and Kibble in my judgment have special roles.

Peter Higgs today said how happy he is to see the results in his lifetime. These scientists have been waiting 48 years and hopefully the Nobel Committees will not delay further. Whether they will agree with my assessment at all, hopefully will become clear by October.

Frank Close is a particle physicist, author, and speaker. He is Professor of Physics at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford. He is the author of several books, including The Infinity Puzzle, Neutrino, Nothing: A Very Short Introduction, Particle Physics: A Very Short Introduction, and Antimatter. Close was formerly vice president of the British Association for Advancement of Science, Head of the Theoretical Physics Division at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and Head of Communications and Public Education at CERN. Read more of what Frank Close has to say about neutrinos here and here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Presidents, protest, and patriotism

In the midst of a military conflict, domestic antiwar opposition always vexes a president. This reaction is understandable. He sees the criticism as a risk to national security, something that will give aid and comfort to the enemy, demoralize American troops in combat, and weaken the resolve of the public. What he fails to appreciate is how protest serves as a warning that something has gone very wrong with his war.

Sherman's Grand Army. Looking up Pennsylvania Avenue from the Treasury buildings. Maj. Gen. Jeff. C. Davis and staff and 19th Army Corps passing in review. 1861-1865. Source: NYPL.

Our adversaries have long appreciated that public opinion is a point of vulnerability in the American arsenal. They have tried to exploit this weakness. During the Civil War, Confederate political and military leaders saw war weariness in the North as their best chance for victory. They understood they could never match the military resources of the Union; their armies would always be outnumbered. Instead they counted on the mounting casualty lists and the perception that the Union forces were making no progress to sap the will on the Northern home front. The Confederacy probably came closest to victory in the summer of 1864 when Union armies stalled outside Petersburg and Atlanta amid horrific battlefield losses. Even Abraham Lincoln concluded he could not win reelection unless the military situation improved.In recent wars in which the United States finds itself fighting insurgents, the American people are again very much a part of the struggle. The US military speaks of “winning hearts and minds” in places such as Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. In fact, however, the hearts and minds of the American people are just as much at stake. The insurgents we oppose recognize that they will prevail if they wear down public support back in the States.

The Vietnam War demonstrates the important role played by the domestic “second front.” To the chagrin of both Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, communist leaders in Hanoi reached out to American antiwar activists and sought to manipulate public opinion in the United States and elsewhere. Civilian casualties from American bombing raids became the subject of propaganda campaigns; the communists kept careful track of the size of peace demonstrations and invited peace advocates to visit North Vietnam to witness the damage done to civilian targets by the air attacks.

Faced with mounting antiwar opposition, a president tends to lash out at his critics. He questions their patriotism. In some instances, he backs efforts to silence the opposition, as when the Wilson administration pushed through the 1918 Sedition Act that permitted jailing anyone who said anything disloyal or abusive about the government or the army. During the Vietnam War, peace groups were investigated to determine whether they were acting on instructions from Hanoi.

A president’s great fear is that as a conflict drags on, the protests will gain traction within the political mainstream. So long as the critics remain isolated on the fringes of political discourse, their voices can be dismissed. Once they find mainstream patrons, however, they gain a platform that makes the challenge difficult to ignore. This happened in 1966 when Senator J. William Fulbright used his position as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to hold televised hearings on the Vietnam War that let critics of the Johnson policy voice their reservations to a national audience. Similarly, the debate over Iraq changed in November 2005 when Representative John Murtha, a Vietnam veteran, urged a prompt withdrawal.

Natural though it may be for a president to see antiwar protest as a threat to American security, his reaction is misguided. The critics are actually performing a vital function. Like the proverbial miner’s canary, they send a crucial signal; when the bird expires, something has gone very wrong. In the case of a growing peace movement, the spreading protest points to the president’s mishandling of the war itself.

Consider Vietnam and Iraq. In the former, opposition became widespread in 1967 as it became clear that the war had reached a stalemate on the battlefield, something that key administration figures such as secretary of Defense Robert McNamara had recognized, but President Johnson refused to address by changing his policy. Protest surged again in 1970 amid President Nixon’s Cambodian incursion, an operation that his defense secretary Melvin Laird also regarded as misconceived. In the case of Iraq, President Bush needed the strong wake-up call delivered by the public rebuff of the Republicans in the 2006 election and the Iraq Study Group report that proposed a specific withdrawal timetable. Bush followed with the troop surge that helped stem the violence in Iraq.

The lesson is clear. Wartime presidents may wrap themselves in the flag, but they need their critics more than they would ever admit.

Andrew J. Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read his previous blog posts: “Obama v. Romney on Afganistan strategy,” “Mitt Romney as Commander in Chief: some troubling signs,” “Muddling counterinsurgency’s impact,” and “To be Commander-in-Chief.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Real ‘spunk’

There was no word spunk in Swedish until Pippi coined it (an event recently celebrated in this blog), but in English it has existed since at least the sixteenth century. It is surrounded by a host of equally obscure look-alikes (that is, obscure from the etymological perspective). To deal with them, I should remind our readers that English, like all the other Indo-European languages, is full of words in which initial s- looks like a gratuitous addition. It pretends to be a prefix but carries no meaning; it does not even make words more expressive. It appears and disappears at will, and no one knows its origin. Linguists call this enigmatic prop s mobile “movable s.” Therefore, when one deals with a suspicious item like spunk, the question arises: “Can it be related to punk?” And if punk has something to do with spunk, where do funk and fungus come in? Etymologists flounder in this net of homonyms and near synonyms, and, as we will see, did not succeed in extricating themselves.

First of all, let us examine all the senses of the words to be discussed below. Spunk means “spark” and “touchwood.” Touchwood is what becomes of wood when certain fungi convert it into a soft mass; once ignited, it can burn for hours like tinder. Touchwood is defined in dictionaries by means of its synonym tinder. “Spark” and “flammable substance” are compatible senses. Spunk “spirit, mettle” can be understood as a figurative extension of “tinder.” The slang sense “semen” (“not in delicate use,” as the OED said about such things in the past) is an obvious extension of “sprit, virility,” though one can say, “You are a spunk,” without overt sexual connotations (the verb to spunk is more explicit).

Since touchwood is not particularly picturesque and spunk is hard or embarrassing to portray, here is an image of Shakespeare's Touchstone, the wise fool in As You Like It. James Lewis as Touchstone in As You Like It, Rehan and Drew production. Source: NYPL.

Next comes punk , again “touchwood.” In Shakespeare’s days, punk meant “prostitute.” The word seems to have gone underground and resurfaced in the memory of the people still living. (No longer “prostitute” but still a derogatory term.) Despite the opinion that punk “strumpet; ruffian” is a coinage of unknown origin, in my opinion, it is not as opaque as most etymologists believe. Multiple words like Puck and buck go back to primitive formations denoting “something swollen.” They often have n in the middle. In Scandinavian languages and dialects, punk refers to all kinds of trash and occasionally stands for “thingy.” Its twin is bunk(e). Whether Engl. punk traces to Scandinavian is immaterial in the present context. Since touchwood is porous and looks swollen, perhaps all the senses of punk belong together (“something bloated, a big fat thing”).It is harder to tell whether punk and spunk are related. Spunk may be punk with s mobile added. If so, the development was from “swollen thing” to “touchwood” and “spark; fiery temperament, mettle; virility.” The story might have had a happy end if alongside punk and spunk, funk did not exist. The noun funk has been recorded with the following senses: “spark; touchwood (the same as spunk),” “strong smoky smell, especially tobacco smell,” “kick, stroke; anger,” and “fear, panic” (for example, to be in a blue funk). The etymology of each of these senses is problematic, and there can be no certainty that any one of them is connected with any other.

How is it possible that punk, spunk, and funk mean exactly the same? We are, naturally, interested in funk “spark; touchwood.” To be sure, burning spunk might have aroused associations with an offensive smell. While inhaling it, people would become angry, panicky, and, if one is allowed to mention the somewhat overused modern slangy adjective, funky. Such steps are easy to reconstruct, for in semantics no river is so broad that it cannot be crossed by an ingeniously built bridge.

Skeat believed that spunk “tinder’ and fungus are related to sponge (because fungus is spongy). From a phonetic point of view, nothing can be said against his conclusion. Greek had the form sphoggos (gg designated ng) “sponge,” and spunk would be an acceptable adaptation of Latin spongia. However, only the fungus-sponge equation is irrefutable, for none of three English words — punk, spunk, and funk – look like a learned borrowings from Latin. Funk “panic” seems to have originated in eighteenth-century university slang. Although a close analog of the phrase to be in a funk has been found in older Flemish, one wonders how it got there and how it made its way to Oxford, where no one would be fluent in Flemish.

A play on some Latin noun suggests itself, but no such noun exists. To give an example of puns and games in this area, I will retell the entry on the slang word fug from The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Fug means “stuffy atmosphere”; it turned up in printed texts only in the nineteenth century and may be a blending of funk and fogo, both meaning “offensive smell” and recorded also in the nineteenth century. Compare fogus “tobacco,” a seventeenth-century word, perhaps a jocular latinization of fog, but fug exists as a variant of fog in Scots. We are in a maze with no thread to show us the way.

I keep repeating that a good etymology is like a jigsaw puzzle; all the pieces must find their places. Skeat was a great etymologist, but he left his problem in the middle. Spunk and sponge form a natural union only if we forget about funk. Yet we are not allowed to forget it. Perhaps punk, spunk, and funk interacted at one time. Some senses of all three words were “low” and their figurative senses were probably better known than their reference to tinder. They rhyme, a factor that plays an important role in the history of words, for words do not live in isolation; they fight, fall prey to fatal attraction, and tend to behave like spiders in a jar. Although I am unable to disentangle the knot of punk, spunk, and funk to my or anyone’s satisfaction, my tentative conclusion may not be entirely fanciful. Punk, an almost generic name of a swollen object with analogs outside English, was evidently the “progenitor” of this group. Spunk, according to this hypothesis, is punk with “movable s” added to it, a younger word, despite the fact that some inconclusive evidence points to its earlier attestation. Funk may have a prehistory independent of those two (but it hardly goes back to an Indo-European word like sponge). Yet when it arose, it began to play lobster quadrille with them. Today they are inseparable, even though some senses are obsolete and little remembered. Too bad, there is no spunk “a funky glowworm” in Swedish to help us out.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Alice in Wonderland in Psychiatry and Medicine

Written by Oxford mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson under the pen name Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was published on 4 July 1865. The book has remained in print ever since, becoming one of the most popular and influential works in all of literature. Alice has been translated into nearly a hundred languages, appeared in countless stage and screen adaptations, and continues to resonate throughout both academia and popular culture.

"At this the whole pack rose up into the air and came flying down upon her" ; Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1907.

Psychiatric interest in Carroll’s work began in the 1930s as disciples of Freud subjected his writings and their author to psychoanalytic scrutiny. Viennese-born NYU professor Paul Ferdinand Schilder savaged both in a 1938 issue of the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, dismissing Carroll as leading “a rather narrow and distorted life” and introducing the unsubstantiated yet persistent idea that he had an unhealthy attraction to little girls. (“We are reasonably sure that the little girls substitute incestuous love objects.”) Schilder was equally scathing about Alice itself, describing it as “the expression of particularly strong destructive tendencies, of very primitive character” and labeling its author “a particularly dangerous writer.” Other psychoanalysts such as John Skinner and Martin Grotjahn, writing in American Imago in 1947, were less hostile toward Wonderland yet continued to interpret the book (and Carroll’s personality) in psychodynamic terms.The analysts’ ruminations were replaced in 1960 with a literary and scientific analysis of Alice in Wonderland and its 1871 sequel Through the Looking-Glass published by Carroll scholar and amateur mathematician Martin Gardner as The Annotated Alice. Commenting on the Red Queen’s “constant orders for beheadings,” Gardner suggests that “violence with Freudian overtones” is quite harmless to children, but that the book “should not be allowed to circulate indiscriminately among adults who are undergoing analysis.”

Meanwhile in the medical literature the analysts were supplanted by neurologists and neuropsychiatrists with the introduction in the 1950s of the Alice in Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS).

In 1952 migraine investigator Caro W. Lippman reported in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease on patients experiencing transitory “hallucinations of the sense of body image, in which the patient has the feeling that the entire body, or certain parts of the body, have become distorted in size or shape” in connection with their migraines. One patient compared her sensation of being abnormally short and wide to a “Tweedle-Dum or Tweedle-Dee feeling” (referencing the rotund twins from Looking Glass) and Lippman remarked on the “migraine hallucinations” which Carroll himself described and recorded “in immortal fiction form.”

Three years later British psychiatrist John Todd described “The syndrome of Alice in Wonderland” in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, adopting the name “not only because it is germane as a descriptive term” but also relevant to Carroll’s history of migraines, which “arouses the suspicion that Alice trod the paths and byways of a Wonderland well known to her creator.” Todd expanded the list of diseases in which the symptoms occur to include “epilepsy, cerebral lesion, intoxication with phantastica [hallucinogenic] drugs, the deliria of fevers, hypnagogic states and schizophrenia.” He likewise expanded the list of possible symptoms to include “illusory changes in the size, distance, or position of stationary objects in the subject’s visual field; illusory feelings of levitation; and illusory alterations in the sense of the passage of time.”

Subsequent reports on AIWS in the medical literature have come from various specialties. Infectious diseases related to the condition include mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr virus, and most recently H1N1, the virus responsible for the Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome (“SARS”). Neuroscientists are beginning to employ new technologies including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), functional MRI (fMRI), and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to diagnose and treat the condition.

Psychiatrists continue to find rare cases associated with depression and psychotic disorders, and on a lighter note Dublin psychiatrist Brendan D Kelly provided a “Psychiatric Perspective” on Alice in as 2008 letter to the Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The story is riddled throughout with psychopathology, he claims, diagnosing the weeping Mock Turtle as “clinically depressed” and the Young Crab as displaying “the first case of oppositional defiant disorder ever described in a juvenile crustacean.”

The most imaginative medical application of Alice in Wonderland, however, occurs as the jocular prologue to a more serious examination of breathing disorders described in several of Shakespeare’s historical dramas. In an essay titled “Sleep of the Great,” published in 2000 in the journal Respiratory Physiology, William A. Whitelaw and A.J. Black of the University of Calgary identify the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party as an early report of obstructive sleep apnea and its treatment. “You might just as well say… that ‘I breathe when I sleep’ is the same thing as ‘I sleep when I breathe’” says the Dormouse (“which seemed to be talking in its sleep”), to which the Hatter replies “It is the same thing with you.” Whitelaw and Black interpret the Dormouse’s “severe daytime somnolence” as “a cardinal symptom of obstructive sleep apnea…. The dormouse cannot breathe and sleep at the same time because… his pharynx falls closed the moment he falls asleep.” The episode ends with Alice walking off in disgust (“It’s the stupidest tea-party I ever was at in all my life!”) as the Hare and the Hatter stuff the Dormouse head first into a teapot. Referring to the accompanying illustration by Sir John Tenniel, Whitelaw and Black explain that the teapot “fits tightly around his neck, thus compressing the air in the pot and producing continuous positive airway pressure, which is the best treatment for obstructive sleep apnea.”

Edward Shorter is Jason A. Hannah Professor in the History of Medicine and Professor of Psychiatry in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. He is the author of numerous books on psychiatric history including A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry and Before Prozac: The Troubled History of Mood Disorders in Psychiatry. Susan Bélanger is Research Coordinator with the History of Medicine Program, University of Toronto, and a keen student of interactions between literature and medicine. Read their previous blog post on “Anti-psychiatry in A Clockwork Orange.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Have you appointed your Privacy Officer yet?

Have you appointed your Privacy Officer yet? And how is your privacy compliance program coming along?

The European Commission’s proposal for a new Data Protection Regulation represents a landslide in data protection law since the 1995 Privacy Directive came into force. Regulations, other than Directives, are directly applicable in the member states and will not require national implementation. The Commission announced its intention to finalise the legislative process before the end of 2012, after which the Proposed Regulation will take a further two years to come into effect.

One of the key innovations of the Proposed Regulation is “accountability.” The Commission recognises that the current Privacy Directive has not been successful in delivering real protection to individuals. To improve this situation the Commission is introducing an accountability provision requiring companies to adopt policies and implement appropriate measures to ensure data protection compliance and to demonstrate these measures to the data protection authorities of the member states when requested. The Proposed Regulation clearly expects companies to implement a comprehensive privacy compliance program. But what does a comprehensive privacy program actually look like?

Guidance is given by the advisory committee on privacy to the Commission (the Working Party 29) which issued an opinion on the concept of accountability. The Working Party 29 indicates that the regime for Binding Corporate Rules can be used as a general template for corporate data protection compliance programs.

But what are Binding Corporate Rules, or BCR?

BCR are a form of corporate self-regulation introduced by multinationals to facilitate their global inter-company data transfers. Review of the accountability requirements identified by the Working Party 29 as now reflected in the Proposed Regulation, indeed shows a nearly complete overlap with the requirements set for BCR. In the words of the Working Party 29: “Indeed BCR are codes of practice, which multinational organisations draw up and follow, containing internal measures designed to put data protection principles into effect (such as audit, training programmes, network of privacy officers, complaint handling system).”

Reviewing the accountability requirements, it seems to have been rather the other way around. The work on BCR by the Working Party 29 seems to have been the basis for the listing of the accountability measures as now reflected in the Proposed Regulation. As practice shows that introduction of a BCR compliance program in most cases takes a period of at least two years, companies are well advised to embark on their privacy compliance project to ensure compliance before the Proposed Regulation comes into force. With proposed fines of up to 2% of your company’s global annual turnover, you may even get the required budget from management to do so.

[image error]Lokke Moerel is a Partner at the international law firm De Brauw Blackstone Westbroek, and chairs its global data privacy and security practice. She provides strategic advice to multinationals on their global ICT compliance. Her book, Binding Corporate Rules: Corporate Self-Regulation of Global Data Transfers, publishes in the UK this month.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 3, 2012

Spending power bargaining after Obamacare

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s Affordable Care Act (ACA) decision, it’s easy to get lost in debate over the various arguments about how the commerce and tax powers do or don’t vindicate the individual mandate. But the most immediately significant portion of the ruling — and one with far more significance for most actual governance — is the part of the decision limiting the federal spending power that authorizes Medicaid. It is the first time the Court has ever struck down congressional decision-making on this ground, and it has important implications for the way that many state-federal regulatory partnerships work.

These partnerships reflect the complex way that the Constitution structures federal power, through both specific and open-ended delegations of authority. Specific congressional powers include the authority to coin money, establish post offices, and declare war. More open-ended grants of federal authority are conferred by the Commerce, Necessary and Proper, and Spending Clauses, about which we have heard so much in recent weeks. Whatever isn’t directly or reasonably indirectly covered by these delegations is considered the realm of state authority. (Of course, there is some overlap between the two, but that’s another story and a previous blog.)

The Spending Clause authorizes Congress to spend money for the general welfare. Congress can fund programs advancing specific federal responsibilities (like post offices or Naval training), but it can also fund state programs regulating beyond Congress’s specifically delegated authority (such as education or domestic violence). Sometimes, Congress just funds state programs that it likes directly. But it can also offer money conditionally — say, to any state willing to adopt a particular rule or program that Congress wants to see. In these examples, Congress is effectively saying, “here is some money, but for use only with this great program we think you should have” (say, health-insuring poor children).

In this way, the spending power enables Congress to bargain with the states for access to policymaking arenas otherwise beyond its reach. A fair amount of interjurisdictional governance takes place within such “spending power deals,” addressing matters of mixed state and federal interest in realms from environmental to public health to national security law. Federal highway funds are administered to the states through a spending deal, as are funds for public education, coastal management, child welfare, the Medicaid insurance program, and countless others.

Congress can’t just compel the states to enact its preferred policies, but spending power partnerships are premised on negotiation rather than compulsion, because states remain free to reject the federally proffered deal. If they don’t like the attached strings, they don’t have to take the money. Members of the Court have sporadically worried about undue federal pressure, but only in dicta and without much elaboration. In 1987, in South Dakota v. Dole, the Court famously upheld the spending bargaining enterprise, so long as the conditions are unambiguous, reasonably related to the federal interest, promote general welfare, and do not induce Constitutional violations. No law has ever run afoul of these broad limits, which have not since been revisited until now.

In challenging the ACA, 26 states argued that Congress had overstepped its bounds by effectively forcing them to accept a significant expansion of the state-administered Medicaid program, even though Congress would fund most of it. All states participate in the existing Medicaid program and many feared losing that federal funding (now constituting over 10% of their annual budgets) if they rejected Congress’s new terms. Congress had included a provision in the original law stating that it could modify the program from one year to the next, as it had done nearly fifty times previously. But the plaintiff states argued that this time was different, because the changes were much bigger and because they couldn’t realistically divorce themselves from the programs in which they had become so entangled. Even though they really wanted out, they claimed, now they were stuck. The feds maintained that congressional funds are a conditional gift that states are always free to take or refuse as they please.

In deciding the case, the Court stated a new rule limiting the scope of Congress’s spending power in the context of an ongoing regulatory partnership. Chief Justice Roberts began by upholding the presumption underlying spending power bargaining, that the states aren’t coerced because they can always walk away from the table if they don’t like the terms of the deal. We mostly dispel concerns about coercion by relying on the states to “just say no” when they don’t like the federal policy. (In a choice rhetorical moment, he offered: “The States are separate and independent sovereigns. Sometimes they have to act like it.”) Accordingly, he concluded that the Medicaid expansion was constitutional in isolation, because states that don’t want to participate don’t have to. No coercion, no constitutional problem.

But then the decision takes a key turn. What would be a problem, he explained, would be if Congress were to penalize states opting out of the Medicaid expansion by cancelling their existing programs. Given how dependent states have grown on the federal partnership to administer these entrenched programs, this would be unconstitutionally coercive. By his analysis, plaintiffs chose the original program willingly, but were being dragooned into the expansion. To make the analysis work, though, he had to construe Medicaid as really being two separate programs: the current model and the expansion. Congress can condition funding for the expansion on acceptance of its terms, but it can’t procure that acceptance by threatening to defund existing programs (analogizing to gun-point negotiating tactics). The decision requires Congress to allow dissenting states to opt out of the Medicaid expansion while remaining in the older version of the program.

Justice Ginsburg excoriated this logic in dissent, arguing that there was only one program before the Court: Medicaid. For her, the expansion simply adds beneficiaries to what is otherwise the same partnership, same purpose, same means, and same administration: “a single program with a constant aim — to enable poor persons to receive basic health care when they need it.” She criticized the Chief Justice for enforcing a new limitation on coercion without clarifying the point at which permissible persuasion gives way to undue coercion, and she pointed out the myriad ways this inquiry requires “political judgments that defy judicial calculation.”

On these points, Justice Ginsburg is right. The decision offers no limiting principle for future judges or legislators evaluating coercive offers. “I-know-it-when-I-see-it” reasoning won’t do when assessing the labyrinthine political dimensions of intergovernmental bargaining, but neither the decision nor the conservative justices’ dissent provides more than that. Moreover, the rule is utterly unworkable. No present Congress can bind future congressional choices, so every spending power deal is necessarily limited to its budgetary year as matter of constitutional law. But after this decision, Congress can never modify a spending power program without potentially creating two tracks—one for states that like the change and another for those that prefer the original (and with further modifications, three tracks, ad infinitum). The decision fails to distinguish permissible modifications from new-program amendments, leaving every bargain improved by experience vulnerable to legal challenge. And it’s highly dubious for the Court to assume responsibility for determining the overall structure of complex regulatory programs — an enterprise in which legislative capacity apexes while judicial capacity hits its nadir.

Nevertheless, the decision exposes an important problem in spending power bargaining that warrants attention. How the analysis shifts when the states aren’t opting in or out of a cooperative federalism program from scratch, but after having developed substantial infrastructure around a long-term regulatory partnership. It’s true that the states, like all of us, sometimes have to make uncomfortable choices between two undesirable alternatives, and this alone should not undermine genuine consent. But most of us build the infrastructure of our lives around agreements that will hopefully last longer than one fiscal year (lay-offs notwithstanding). The Chief’s analysis should provoke at least a little sympathy for the occasionally vulnerable position of states that have seriously invested in an ongoing federal partnership that suddenly changes. (Indeed, those sympathetic to the ACA but frustrated with No Child Left Behind’s impositions on dissenting states should consider how to distinguish them.)

It’s important to get these things right because an awful lot of American governance really is negotiated between state and federal actors this way. Federalism champions often mistakenly assume a “zero-sum” model of American federalism that emphasizes winner-takes-all competition between state and federal actors for power. But countless real-world examples show that the boundary between state and federal authority is really a project of ongoing negotiation, one that effectively harnesses the regulatory innovation and interjurisdictional synergy that is the hallmark of our federal system. Understanding state-federal relations as heavily mediated by negotiation betrays the growing gap between the rhetoric and reality of American federalism—and it offers hope for moving beyond the paralyzing features of the zero-sum discourse. Still, a core feature making the overall system work is that intergovernmental bargaining must be fairly secured by genuine consent.

Supplanting appropriately legislative judgment with unworkable judicial rules doesn’t seem like the best response, but the political branches can also do more to address the problem. To ensure meaningful consent in long-term spending bargains, perhaps Congress could provide disentangling states a phase-out period to ramp down from a previous partnership without having to simultaneously ramp up to new requirements — effectively creating a COBRA policy for states voluntarily leaving a state-federal partnership. Surely this beats the thicket of confusion the Court creates in endorsing judicial declarations of new congressional programs for the express purpose of judicial federalism review. But in the constitutional dialogue between all three branches in interpreting our federal system, the Court has at least prompted a valuable conversation about taking consent seriously within ongoing intergovernmental bargaining.

Erin Ryan is currently a Fulbright Scholar in China. She is a professor of law at Lewis & Clark Law School, where she will return this summer. Ryan is also the author of Federalism and the Tug of War Within. Read her previous post “Health care reform and federalism’s tug of war within.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The dawn of a new age of government?

Senator Edward Kennedy called healthcare reform the “the great unfinished business of our time.” Now it is finished. Every branch of the US government has had its say. The Supreme Court decision also marks the end of the Rehnquist era. No longer can we reliably predict that it would always send powers back to the states. Indeed, it said “No” to 26 states which had challenged the Affordable Care Act.

This is also, incontrovertibly, a victory for Obama. Today, John Boehner called the Act a “harmful” law. Mitch McConnell called it “terrible.” Romney called it “bad.” But none of them can call it “unconstitutional” anymore, taking the wind out of the Tea Party‘s sails.

Sure, this is now a rallying and fund-raising issue for Romney, but it’s always been an issue. The conservative base now knows that the only way to repeal the Affordable Care Act is to take out Obama. The difference between a conservative and an independent voter, however, is that only the former looks back. Swing voters at the presidential lever will appreciate a conservative Chief Justice’s endorsement of the Affordable Care Act and won’t care anymore after this. This is now a done deal. It re-establishes Obama as a leader because he joins Lincoln and FDR as a winner in tumultous politics.

If Obama follows up and wins the election this year, we may be in for a resurgent Age of Government after three decades of retrenchment. FDR caused the nine (justices) to switch in time in 1937. Obama caused only one, but then again he pushed through a law that FDR knew he couldn’t do. And the one justice to switch was a Chief Justice appointed by his Republican predecessor no less.

To be sure, the Court did reject the administration’s argument that the Interstate Commerce clause legitimated the individual mandate. Chief Justice Roberts, however, argued that the Supreme Court’s job is to mine the Constitution for arguments — even when the administration failed to find or emphasize them — to sustain acts passed by Congress. In ruling that the mandate is constitutional under the taxing and spending powers of the Congress, he exercised, in his mind, the duty of judicial restraint and deference to the elected branches. In this, he acted like the Justice George W. Bush thought he had nominated to the bench.

However, the constitutional reasoning Roberts proffered — that the individual mandate is a tax (and the Attorney General explicitly said it was not) — is way beyond what Bush or any conservative would have liked. People aren’t quite coming to grips with this fact yet. The congressional power to tax is a massive power and by failing or refusing to make a clear and distinct separation between what is a tax and what is penalty (Roberts gave three very weak reasons), this decision delivered a huge victory for “big government” liberals. Almost anything can henceforth be classified a tax and therefore permissible under the taxing and spending clause of the Constitution.

The Anti-Federalists of 1787/88 were right; where the purse lies, so does sovereignty. Publius, or at least Hamilton, knew it too, but he kept mum about it because his goal had always been a “consolidation” of federal authority. Today, Justice Roberts unknowingly but effectively extinguished the (already specious) distinction between a tax and a penalty. When Republicans now turn their argument to calling “Obamacare” “Obamatax,” they are fighting on much weaker ground than before because the taxing and spending powers of Congress are massive. Yet this power was among the principal reasons for why the Constitution was written in the first place. What John Roberts did, in effect, was to force conservatives back their original ground and show their true colors. They are, at heart, Anti-Federalists who are no more appreciative of a powerful federal government in 1787 than in 2012.

Liberals shouldn’t get too smug yet though. The individual mandate is not the panacea of our still very flawed health-care system. Thirty million or so people are now going to be in the system in 2014 and they will move from emergency rooms to already crowded primary care physician offices. This is the start of healthcare reform, not the end. But it is also the start of an era where government is no longer seen as the problem. It may yet prove to be the solution again.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears here each week.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Living Anthems

The Fourth of July, aka “Independence Day” (the annual federal holiday in the United States marking the 1776 signing of the Declaration of Independence from Britain), is cause for national celebration and certainly the celebration of nationalism. Fireworks, orchestral concerts, parades, 5-K runs, carnivals, family picnics, and political speeches are common holiday happenings. Many are accompanied by music, especially by a haphazard class of folk tunes known as patriotic song that often defy historical logic, but nevertheless have become potent cultural symbols.

The social resonance of patriotic song is impossible to create artificially. Attempts to compose new patriotic anthems have historically been doomed to failure. Rather, patriotic song ferments over decades in shifting concoctions of social, political, and cultural practice. They grow not in time or place or even in a particular composer or epic event but in a people. Patriotic songs are not things so much as living cultural processes, ever changing and more often than not shrouded in the collective amnesia of myth and legend.

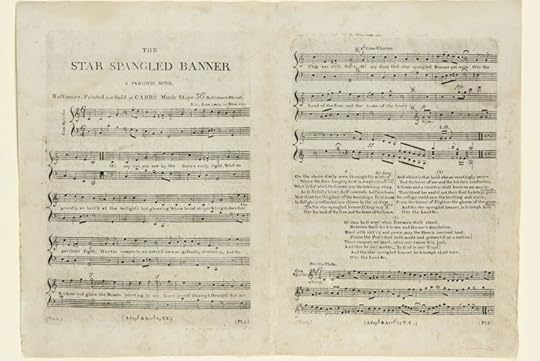

The United States national anthem — “The Star-Spangled Banner” — offers an instructive example of a patriotic song that is very much a living anthem, made and re-made both daily at sporting events, high school graduations, and political rallies. The song has its origins in a particular time, place, person and event, yet its import derives from countless performances over the past century and more. Its history defies symbolic logic. A musician setting out to compose an anthem for any nation today would never borrow a jaunty tune from a former colonial overseer that’s hard to sing, bloodied by war, and steeped in alcohol. Yet this is precisely the case for the national anthem of the United States.

“The Star-Spangled Banner,” as Francis Scott Key’s poem is now known, was written in mid-September 1814 to celebrate the defeat of the British navy at the Battle of Baltimore during the War of 1812. The event was a critical American victory as Britain had only days before marched all but unopposed through the young nation’s capitol of Washington, DC, burning the city to the ground. A lawyer as well as amateur poet, Francis Scott Key had been aboard a British ship negotiate a successful prisoner release. As the enemy’s plans for attacking Baltimore had been discussed within earshot, Key was detained for the duration of the battle and wrote his now famous lyric in ecstatic response to America’s unanticipated victory.

Published in fall 1814, the first edition imprint of the sheet music for Key's poem was retitled "The Star Spangled Banner." Only about 11 copies are known to survive with one selling recently for $500,000--reportedly the largest sum ever paid for a piece of printed music. The original edition is readily identified by a typo below the title that reads "A Pariotic Song," rather than "Patriotic" with a "T."

Key’s poem was published almost immediately as a broadside ballad in newspapers along the Atlantic coast, with the lyric accompanied by some variation of the note “Tune: Anacreon,” indicating a well-known melody to which the words could be sung. This title referred to the club song of London’s Anacreontic Society, an amateur musicians and singing association. Some including contemporaries of Key, claimed that it was only after the lyric had been written that it was noticed how words fit the British melody, yet the poem’s rare metric structure and the fact that Key had written a previous poem, “When the Warrior Returns,” in 1805 to the same tune make this happenstance less than likely. (Key’s earlier poem, in fact, shares both sentiment and specific lines with the new version, including the key phrase “the star spangled flag of our nation.”)

The tune is indeed a strange choice for a national anthem. Its melodic compass from lowest note to highest is an octave plus a fifth (known to musicians as a twelfth) making the melody awkward at best for group singing. Its British origins dilute nationalist pride. Its continuing reputation as a drinking song sullies any potential idealism, but results from both a misunderstanding of the Anacreontic Society, really a rather elite professional association (which indeed met for a time at London’s Crown and Anchor Tavern), as well as a series of contrafact New World lyrics more in keeping with its use as a boisterous pub ditty. Yet we can’t really blame Key for these problems. Key, of course, was not writing a national anthem. He was writing a lyric to celebrate “The Defense of Fort McHenry,” as the poem was first known, and toasting the young nation’s heroic victory at the pub might well have been part of the intent.

That Key left no first-hand account of the poem’s origins lends further proof to his limited aspirations. He didn’t expect the lyric to survive long in the popular imagination; most broadside ballads didn’t. As a result unfortunately, we likely will never know for certain if Key’s selection of a British tune had been intentional. Certainly it adds a bit of parody and satire to the lyric’s mocking of a vanquished foe. In this spirit, the song was originally sung relatively quickly in the cause of celebration. Early sheet music imprints indicate “Con Spirito” [with spirit] as a tempo marking. The melody’s characteristic dotted rhythms had yet to be added. Their later appearance served to cut the tempo and thus lend gravitas to its performance as anthem.

While Key’s authorship was never in question, knowledge of who composed the music was uncertain as late as 1977 when William Lichtenwanger, head of the Reference Section in the Music Division of the Library of Congress, published “The Music of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’: From Ludgate Hill to Capitol Hill.” Lichtenwanger built upon research by earlier music specialists employed by the Library of Congress, notably Oscar Sonneck and Richard S. Hill, but with the added good fortune to run across an obscure diary entry that finally and unambiguously connected authorship of the tune with John Stafford Smith, an English composer and keyboardist employed by The Anacreontic Society for its instrumental dinner prelude concerts. Not being a member of the club, Smith presumably did not merit his name’s inclusion on Anacreon’s eventual sheet music imprint.

It wasn’t until 1931 that Key’s song became the official anthem of the United States of America by act of Congress. Prohibitionists, nationalists, pacifists, and even music teachers opposed the choice, suggesting alternatives including “Hail Columbia” and “America, the Beautiful.” While these objectors each had good reasons to forward an alternative to Key’s Banner, the choice had long been made. President Herbert Hoover’s signature on Statute 1508 was less legislative creativity than simple recognition of the ever-developing role “The Star-Spangled Banner” already had in US life. Advanced by its association with the flag, especially in military ceremony during the Civil War, Spanish American War, and World War I, the Banner had long replaced “Hail Columbia” and “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean” as the de facto anthem of the nation. Thus the real decision was made not by Congress but by living cultural practice.

(Had “God Bless America” been well known at the time, it might have proved a significant challenger. But Irving Berlin’s song was invisible until 1938, when it was performed as a prayer for continued peace in the face of Nazi aggression by singer Kate Smith for an Armistice Day radio broadcast remembering the end of World War I.)

The tale of “The Star-Spangled Banner” thus celebrates the myriad ways in which Americans, from kindergartners to military veterans and baseball fans to newly naturalized immigrants, have used the song to give voice to citizenship. That we as Americans lose track of who wrote the song, when, and why is less a criticism of our historical memory, than a signal of the song’s continued relevance as living ritual. “The Star-Spangled Banner” thrives as a symbol of the nation in performances both expert and amateur, accurate and not-so-much, in the everyday re-creative acts of countless individuals. In concert by the New York Philharmonic performing in North Korea or as sung by a young girl at a hockey game whose microphone cuts out inspiring the crowd to finish the song, “The Star-Spangled Banner” is alive and well.

is Associate Professor for Music (Musicology), American Culture, Afro-American Studies, and Non-Profit Management at the University of Michigan. He serves as Project and Cities and Institutions Editor of the New Grove Dictionary of American Music, Second Edition (OUP, 2013). As Director of the American Music Institute at the University of Michigan, he is active on Twitter as @usmusicscholar and contributes to the blog O Say Can You Hear on the history of the U.S. national anthem, which will develop into a book.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Oxford Sheet Music in the United Kingdom has several arrangements of “The Star-Spangled Banner” available. Two arrangements as vocal scores by Frank Sargent and by Jerry Rubino. There is also an arrangement by William Walton in one of the scholarly Walton Edition volumes, including this critical commentary: “Like ‘God Save the Queen’, Walton also orchestrated the American Anthem for the Philharmonia Orchestra’s first tour of the United States. Answering a query from Alan Frank in a postcard to him of 10 March 1975, Walton wrote: ‘Yes I did orchestrate the S.S.B. for Karajan when he took the Philharmonia to the U.S. years ago [. . .]. It was not my best effort of [sic] scoring and I don’t think it was ever played or paid for! I’ve no idea where the sc. & parts are but it is best destroyed if discovered’.” Oxford Sheet Music and a small number of books about music and hymn books are distributed in the US by Peters Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers