Oxford University Press's Blog, page 2

August 12, 2025

The bordered logic behind the headlines

The bordered logic behind the headlines

‘Where do you want to go today?’ served as the tagline for software giant Microsoft’s global marketing campaign running through the mid-1990s. The accompanying advertisements were replete with flashy images of people around the world of all ages, ethnicities, and backgrounds engaging in a diverse range of activities, including business, education, video games, artistic expression, socializing, and research, to name some of the most prominent examples. The slogan ‘Where do you want to go today?’ implied that people were largely free to travel where they wished, but, of course, Microsoft was selling the power of its software to facilitate the free flow of information and communication, and by extension greater connectivity and collaboration, among people around the world, rather than the actual movement of people.

Yet combined with rapid advances in hardware and software, the tagline captured something of a popular mood of the time. Within many Western societies, the end of the Cold War, the continued liberalization of international trade and travel through a variety of supranational institutions and international agreements, and the growing clout of transnational corporations and nongovernment organizations heralded the coming of a borderless world. The prospect of unprecedented, unfettered mobility and connectivity for an ever-growing number of people seemed imminent.

Looking back thirty years later, those expectations were overly optimistic. It is impossible to deny the truly remarkable technological advances—personal computers, the internet, mobile phones, and wireless communications—that compress space and bridge territories. Yet far from a borderless world, the first decades of the twenty-first century have witnessed a resurgence of borders with impacts on a variety of political, socioeconomic, environmental, technological, and human rights issues.

In fact, borders have been central to two of the most significant events of the 2020s, namely the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The COVID-19 pandemic saw governments, with varying degrees of severity and effectiveness, impose border controls, restrict domestic and international travel, and implement systems of confinement and quarantine. These measures disrupted global supply chains and confined millions of people to their homes as their freedom to attend school, go to work, gather for worship, or even simply shop for daily essentials was restricted. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has also disrupted global trade networks, while ravaging large swathes of Ukrainian territory, displacing millions of civilians, and prompting massive increases in defense spending far beyond the direct combatants.

Unfortunately, there is no shortage of international and civil conflicts roiling the international scene. The attacks by Hamas militants from the Gaza Strip into Israel in 2023 prompted Israeli retaliatory attacks and eventually a full-scale invasion into Gaza. This, in turn, gave rise to a series of broader, overlapping regional conflicts involving dozens of state and non-state combatants, including Hezbollah and Houthi militants in Lebanon and Yemen respectively and Iranian and Israeli attacks and counterattacks. That turmoil provided at least proximate triggers for the rapid collapse of the Assad regime in Syria in 2024, leaving that country divided among a mixture of forces representing a provisional government, various sectarian militias with unclear allegiances, and remnants of Islamic State forces. Syrian territory also hosts American, Russian, and Turkish armed forces, in some ways resembling the proxy conflicts of the Cold War.

While the war in Ukraine and tensions in the Middle East have dominated headlines, other armed struggles have flared and persisted across the North African, Sahel, South Asian, and Central Asian regions. Afghanistan, Congo, India, Myanmar, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Yemen remain gripped, at least in part, by civil strife and border disputes stretching back years, if not decades. Beyond the battlefield death and destruction, these conflicts have broader consequences, including refugee flows, economic dislocation and poverty, and malnutrition and hunger, among other problems.

Looming menacingly in the background is the specter of renewed great power competition, primarily between the United States with its global alliance system and the burgeoning partnerships between China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia, as well as other like-minded authoritarian regimes. After years of forging economic interdependencies, China has been increasingly assertive in projecting power across the Indo-Pacific realm, especially regarding its claims over Taiwan, the South China Sea, and the Himalayas. The United States has responded with calls to ‘pivot to Asia’ based on targeted sanctions and a general decoupling from China’s economy, strengthening alliances stretching from East Asia through Southeast Asia and Oceania into the Indian basin, and more robust and forward military deployments across the region. Ramifications of great power conflict across the Indo-Pacific realm would greatly exceed the calamities of other ongoing wars.

This blog has summarized, admittedly in broad strokes, the shift from relative optimism in the 1990s—characterized by aspirations for a more collaborative and interconnected global community—to a world confronted by profound challenges in which borders will play central roles through the coming decades. Beyond this focus on larger-scale geopolitics and hard international power, borders are central to a variety of other issues across multiple scales, including debates about trade and tariffs, citizenship and immigration, crime, surveillance and privacy, and cultural change and human rights, to name a few. Headlines on any day offer striking examples of issues and events involving borders.

Given the salience of borders to such an array of pressing issues, Oxford University Press has launched Oxford Intersections: Borders to provide the latest border research, highlighting this field’s broad relevance. Borders are shown to be simultaneously positive and negative, often in the same place and at the same time to different people. Borders remain a prime modality of defining and enacting power across multiple scales. This collection seeks to reveal how, where, why, by whom, and to what effect that power and aspiration of territorial control is exercised. We hope readers will engage Oxford Intersections: Borders to encounter new perspectives on a topic that is elemental to human experience and foundational to the form and function of power.

Feature image by Greg Bulla on Unsplash.

August 7, 2025

A cultural history of the purse [timeline]

A cultural history of the purse [timeline]

In conducting research for The Things She Carried: A Cultural History of the Purse in America, Kathleen B. Casey discovered how one everyday object—the purse—could function as a portal to the past. She encountered purses in museum collections, photo albums, advertisements, trial transcripts, and much more.

Here are some highlights she discovered in the cultural history of the purse.

Featured image provided by Kathleen B. Casey.

August 6, 2025

Your Indo-European beard

It sometimes seems that the greater the exposure of a body part, the greater the chance of its having an ancient (truly ancient!) name. This rule works for foot, partly for eye and ear, and also for heart (even though the heart isn’t typically open to direct observation), but it breaks down for finger, toe, and leg. In any case, beards cannot easily be hidden, even with our passion for masks. Moreover, through millennia, beards have played a role far in excess of their importance, and beard is indeed a very old word. A beard used to manifest virility and strength in an almost mystical way. We remember the story of Samson: once deprived of his beard, he became a weakling and had to wait until the hair grew again on his chin, to wreak vengeance on his enemies. The earliest example of clean-shaven in The Oxford English Dictionary (OED online) goes back to 1863 (in a poem by Longfellow!), while beardless was usually applied to boy and young man.

Five years ago, I discussed, among other things, the origin of the idiom to go to Jericho, roughly synonymous with to go to hell. Judging by what turns up on the Internet, today, the origin of the phrase is known to those who are interested in etymology, but Walter W. Skeat (1835-1912) claimed that he could not find any explanation for it and referred to the Old Testament (2 Sam. X. 5 and 1 Chron. X. 5). He appears to have been the first to explain the phrase.

The story runs as follows: after the death of the king of the Ammonites, David sent his envoys to Hanun, the son of the deceased king, to comfort him. But Hanun’s counselors suspected treason, seized the envoys, had half of their beards cut off, and sent the men back. This incautious move resulted in a protracted war and the defeat of the Ammonites. When David’s envoys, deeply humiliated and almost beardless, returned home, David advised them to “tarry at Jericho till their beards were grown.” In their present shape, they were “emasculated” and could not be seen in public.

This is all that remains of Jericho today.

This is all that remains of Jericho today. Photo by Bukvoed. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Scandinavian god Thorr.

The Scandinavian god Thorr. Image: Thor, Hymir, and the Midgard Serpent, 1906. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Reference to the absence of a beard is familiar from various sources. Thus, Njál, the protagonist of the most famous Icelandic saga, was wise and virile but had almost no hair on his chin, and this defect became an object of obscene jokes. By contrast, the great Scandinavian god Thor (Þórr) did have a huge beard. More about the Scandinavians will be said below.

English beard has a few immediately recognizable cognates in Germanic, such as Dutch baard and German Bart. The Slavic and Baltic words sound nearly the same. Latin barba, despite some inconsistency in the correspondence between the final consonants, seems to belong here too. But barbarian does not. Barbarian was a Greek coinage (the Greek name for beard is quite different) and referred to foreigners and their incomprehensible babbling. Those people did say something (barabara), but who could understand them, and who cared? Perhaps it should be added that the Old Celtic name for the poet (bard) has nothing to do with beards either.

As usual, a list of cognates may not tell us anything about the ultimate origin of the word (in this case, beard), and as happens so often, we find ourselves in a linguistic desert. It is not for nothing that while discussing beard, our best dictionaries list several related forms and stop. There was indeed the Old Icelandic noun barð “edge, verge, rim” (ð has the value of th in English the), but whether it is cognate with beard is unclear. It may be: the affinity between “beard” and “edge” is obvious. If so, the association that gave rise to the coining of beard stops being obscure. (Though Icelandic barð “beard” also existed, it might be a later loan from German.)

The only other Germanic name of the beard occurred just in Icelandic, and its cognates continue into Modern Scandinavian. The word was skegg, related to Old English sceacga “rough hair or wool.” Its modern reflex shag still exists, but most will remember only the adjective shaggy, related to Old English sceaga “thicket of underwood and small trees; coppice, copse,” almost a doublet of sceacga, cited above.” (In my experience, no one recognizes the word coppice, and even the spellchecker does not know copse; hence my long gloss.) We have seen that in some societies, a beardless man was not really considered to be a true male, and in light of this fact we are not surprised to find that Old Icelandic skeggi meant “man” (boys of course waited for the time when they became men). Yet the famous Romans (as far as we can judge by the extant statues) were beardless, while the Greeks had sizable beards. No custom is or was universal.

George Bernard Shaw saved the word shaw from oblivion.

George Bernard Shaw saved the word shaw from oblivion. Image: Shaw, 1911. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Coppice and copse are almost dead words in Modern English, and the same holds for shaw “thicket,” the modern reflex of sceacga, though still common in dialects and place names. The word owes its fame to George Bernard Shaw. No need to feel surprised at the existence of such a surname: don’t all of us know the family name Wood?

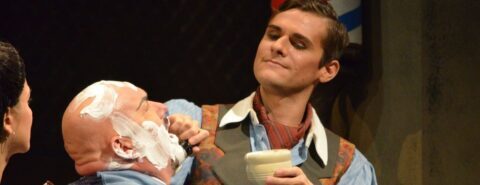

One of the curiosities of English is the verb beard “to oppose,” remembered, if at all, only from the idiom “to beard the lion in his den.” Is the implication “to face the enemy (beard to beard)” or “to catch the opponent by the beard”? An example of this phrase also occurs in the Authorized Version of the Bible, and again in connection with David. Beards, it appears, were famous, but they had to be cut and trimmed. Thorr was an obvious exception (but in the figurine that has come down to us, his beard merges with his male organ and emphasizes his potency, which is fair: an ancient thunder god was responsible for fertility). Having paid reference to shaggy males, let us also remember barbers. Today, a barber more often cuts hair than trims beards, but the etymology of barber is obvious. The Barber of Seville immortalized the profession. Long live Beaumarchais and Rossini!

Featured image: the Florida Grand Opera presents The Barber of Seville. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

August 1, 2025

A snapshot of genomics and bioinformatics in modern biology research

A snapshot of genomics and bioinformatics in modern biology research

I often tell my students that biology has become a data-driven field. Certainly, there’s a general sense that methods related to biological sequences (that is methods in genomics and bioinformatics) have become very widespread. But what does that really mean?

To put a little flesh on those bones, I decided to look in detail at all the biology-related articles in a single issue of the journal Nature (issue 8069, the one that was current when I started). I’m focusing here on articles, representing novel peer reviewed research. By my count, 16 of the 26 papers in this issue are related to biology in one way or another. (Those 16 also include neuroscience and bio-engineering related papers).

For each of these articles I went through the methods looking for genomics and bioinformatics related approaches. I sorted what I found into a few categories. Here’s a short summary:

Four of the papers (25%) used high throughput DNA sequencing.Four were doing phylogenetic reconstruction. (Two of these were doing both phylogenetic reconstruction and sequencing).Four were doing RNA seq, that is high throughput sequencing of RNA to study gene expression.Five used computational methods of sequence analysis (e.g. alignment or its derivatives).My “other high throughput methods” category also contained five papers.Considering all high throughput sequence-related methods together, I found that 10/16 papers fell into at least one of these categories. That is, just over 60% of biology papers in this issue were using one or another such method. Which is to say, these methods really are very common in modern research.

The papers in issue 8069 used these methods to study a huge diversity of questions. One paper used sequencing based approaches to better characterize variation in the pea plant studied by Gregor Mendel, using this to get insights into the basis of several of his traits (which had not previously been known). Another looked at deep phylogenetic relationships among eukaryotes. Still another compared patterns of methylation during development between eutherian and marsupial mammals. I could go on, but the message is that genomics and bioinformatics are used to answer many different kinds of questions.

The take-away is that these are foundational methods for modern biology. As such they should be basic training for any student interested in continuing with research in the biological sciences. This is not only so students can conduct research on their own, but also so they can understand papers they read in a deeper and more sophisticated way.

In our recent second edition of the book Concepts in Bioinformatics and Genomics, we try to balance biology, mathematics and programming, as well as build knowledge from the ground up. Topics range from RNA-Seq and genome-wide association studies to alignment and phylogenetic reconstruction. Our hope is that this approach will help students understand the research they encounter on a deeper level and prepare them to potentially participate in that enterprise.

Featured image: by CI Photos via ShutterStock.

July 30, 2025

A handful of remarks on hinting and hunting

A handful of remarks on hinting and hunting

Allow me to introduce a group of seemingly ill-assorted words. Each member of this group occupies a secure place in the vocabulary of English, but no one knows for sure whether they belong together. My pair of distinguished guests is hint and hunt. They look very much alike and, in a way, their meanings are not incompatible: both presuppose the existence of a searched-for target. One wonders whether they aren’t even variants of the same verb or at least related.

A hunt? A hint?

A hunt? A hint? The stolen kiss by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The Hermitage Museum. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

It is the third time that I am returning to the origin of English hunt. See especially the post for February 12, 2020, and the comments. There will be some overlap between that essay and the one I am offering today, but now that several years have passed, I think I have partly solved the riddle (for myself) and decided to return to that intractable word.

Like some older authors, I suspect that hint and hunt are related. They even resemble non-identical twins. Mark Twain wrote a little-remembered but very funny tale “The Siamese Twins.” In the final sentence, it informs the reader that the ages of the brothers were respectively fifty-one and fifty-three. The author apologized for not mentioning this fact earlier. I decided to avoid his mistake and to make things clear right away. Hunt (the verb) has been known since the days of Old English, that is, for more than twelve centuries. By contrast, hint (the noun) first surfaced in texts by Shakespeare.

Though hint is a relatively recent word without a respectable pedigree, it looks like it belongs with hunt and hand (we use the hand for seizing things; hence an association with hunting). As expected, opinions on their relationship differ. Hunt is a typical English verb for “chasing game.” It lacks obvious cognates, but in many other languages, words meaning “hunt” are also obscure. For example, German has jagen, about whose origin nothing definite is known either.

There may be a good reason for this seemingly unexpected opaqueness—unexpected, because hunting is such a common and seemingly transparent occupation. For millennia, hunting sustained early communities, and people’s survival depended on the success of the chase. Danger lurked everywhere: the hunter might get lost, killed by his prey, or return empty-handed. Words designating such situations often fell victim to taboo, just as, for example, many animal names did. Call the bear by its name, and it will come and destroy you. But if you speak about the bear as a honey-lover (that is what they do in Russian) or the brown one (that is the case in Germanic: from a historical point of view, bear means “brown”), the beast will be duped and stay away. (Talk of the Devil, and he will appear! Right?) The same practice prevailed for the names of several wild animals, body parts, and diseases. (My apology: taboo was also made much of in the earlier post.)

Common words were distorted, and today we usually have no way of guessing what the original form was. Yet we sometimes know the idea behind the euphemism: for example, not the Devil but the Evil One (or Flibbertigibbet, for variety’s sake); not the bear, but the honey-eater or the brown one. The main Latin verb meaning “to hunt” was vēnārī, related to Venus. The idea must have been “to do something with a will, full of desire.” (A digression: the most often hunted animal was the deer, so much so that Tier, the German cognate of deer, means simply “animal.” Deer is a Germanic word, but those who have read the anthologized opening chapter in Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe know that it was the Anglo-Saxons who killed deer, while the meat went to the table of the French barons. Hence venison, related to the Latin verb, cited above.)

The same seems to hold for Russian okhota (with cognates elsewhere in Slavic; stress on the second syllable): the root khot– means “to wish, desire.” The English verb hunt should probably be “deciphered” as “to catch, seize.” Perhaps, it was a vague taboo word, like its Latin and Slavic synonyms. If hint really appeared so late, it cannot be related to hunt, which, though devoid of relatives (and thus “local”), was already old even in Old English.

Fortunately, the situation is not hopeless. Hint, first recorded as a noun, meant “opportunity; slight indication or suggestion”; thus, just a dab, as it were. It was a mere reshaping (or an alternate form) of the now obsolete old verb hent “get, receive”! The desired time bridge has thus been restored. We can proceed with our chase, and while looking around, we notice the already mentioned hand, a Common Germanic word again (!) of uncertain origin, to quote some dictionaries (elsewhere in Indo-European, this extremity has quite different names.)

Could hand also be a taboo word for something like manus (manus is Latin for “hand”)? Indeed, it could. As just noted, the names of body parts are often products of taboo. Hand is an instrument of catching, grasping, “handling” things. It is an ideal member of our ill-assorted family. The scholarly literature on hunt and especially hand is huge, and many (but not all) language historians defend the ideas mentioned above. The bridge exists. Though it rests on unsafe supports, it may sustain the construction rather well.

The final actor in our drama is the Gothic verb fra-hinþan “to take captive” (fra– is a prefix; þ has the value of English th in thin). Gothic, a Germanic language (now dead), was recorded in the fourth century. Some of the Old Germanic words, related to –hinþan, mean “to reach” and “booty.” Though –hinþan and hand have often been compared, þ and d don’t match, and a reliable reconstruction depends on exact sound correspondences. Once such correspondences fail, etymologists are in trouble. However, here we seem to be dealing with a “special” taboo word, and it would be unrealistic to expect great precision in the coining of its forms. Obviously, I am pleading for special dispensation.

Taking captives.

Taking captives. Wood engraving by John Philip Newman, 1876. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

As usual, I refuse to press my point, but I also refuse to concede defeat. It sems that a special taboo word with the sense “grasp, seize, catch,” sharing the root hent/hint ~ hunt ~ hand did exist in Germanic, and its reflexes are still discernible today. Hinþan was a strong verb (that is, a verb, whose root vowels alternated by ablaut, as, for instance, in English bind ~ bound or run ~ ran). The nouns, related to it, were like English bend and band. If this conclusion deserves credence, hint (from hent), hunt, and hand are modern reflexes of that ancient taboo word. Let me repeat that numerous researchers think so, but the most cautious critics prefer to sit on the fence. This is fine. The fence is as good a support as any other.

The etymologist as a hunter.

The etymologist as a hunter. Leopard stalking by Greg Willis. CC-By-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image via Pixabay.

July 28, 2025

Knowledge and teaching in the age of information

Knowledge and teaching in the age of information

The advent of the World Wide Web in the turn of the last century completely transformed the way most people find and absorb information. Rather than a world in which information is stored in books or housed in libraries, we have a world where all of the information in the world is accessible to everyone via computers, and in the last decade or so, via their handheld mobile device. The young people currently in university or in school grew up in a world where information is not privileged and immediate access to all of it is taken for granted. In this age of immediate and readily accessible information on any subject, we must ask: What is the role of academic institutions in teaching? If anyone can find out anything at any time, why learn anything? Is there any value to knowledge in its own right?

The answer is that of course teaching and learning are still important, but they must change to reflect the way information is accessed. The fact is that information on its own is useless without a contextual framework. It may be possible to easily find a detailed account of all of the units and commanders that participated in the Battle of Regensburg in 1809, but if the reader has no understanding of military history, and no background on the politics leading to the Napoleonic wars, this information is no different from a shopping list. Similarly, it may be possible to find detailed information on the excretory system of annelid worms, but without an understanding of what excretory systems are and what their role is in the organism, and without a knowledge of the biology and evolution of annelid worms, this information is no more than a list of incoherent technical terms.

These two very different examples serve to highlight the difference between information and knowledge. Possessing knowledge about a subject means being able to place information into a broad framework and context. People who are knowledgeable about the Napoleonic wars do not necessarily know the names of every commander of every unit in the Battle of Regensburg, but if they need this information, they can access it and use it better than someone with no knowledge. A comparative zoologist may not know all the details about annelid excretory systems, but when needed, they will know what to look for.

With this distinction in mind, I suggest that teaching and textbooks need to shift their focus from transferring information to transferring knowledge. No textbook can compete with the wealth of information available at the students’ fingertips. No course can ever impart all that there is to know about a subject. However, a good teacher and a well-written textbook can provide a much better framework for knowledge and understanding than a search engine will ever be able to. Indeed, a course or module that overburdens the students with numerous bits of information is not only a misuse of resources, it is ultimately counter-productive, as the student will always be able to challenge the teacher with a new bit of information not included in the course.

Teaching in the age of information should focus on providing a working vocabulary of a subject and on building a robust framework of knowledge. Detailed examples can be used to demonstrate principles, but this should be done sparingly. The curious students can then fill in the details on their own, taking advantage of the information at their fingertips.

I have been following these principles in my teaching of evolution and organismic biology for as long as I have been a university professor. My frustration at the details-heavy zoology textbooks led me to write a new textbook, focusing on principles and on providing a conceptual framework to organismic biology, rather than on details. For example, I have written a chapter on excretory systems that outlines what the roles and functions of this system are, and gives a few demonstrative examples of how these functions are manifested in a small number of organisms. I have included similar chapters on other systems interspersed with chapters on individual animal phyla, which give an overview of the phylum and its diversity, and present the specific variations within each of the organ systems, and how these are adapted to the life history of members of the phylum.

As we and our students continue to have easier and more readily available access to information, this new approach will provide a more successful framework for students to continue to grow and learn as they step out into the world. Hopefully this approach will be picked up by authors of additional textbooks to provide a new generation of teaching resources, more suitable for the age of information.

Feature image credit: Ilya Lukichev via iStock.

July 27, 2025

What does one day mean?

A while ago, a reader pointed me to a comment on another writer’s OUPblog piece. The comment complained about a caption on a photo, an image of the painting “Adam and Eve in Paradise” by the seventeenth-century Flemish painter David Teniers the Younger. The original caption read “The world was also young one day,” and the comment read

The caption to Adam and Eve pic “the world was also young one day” should be “the world was also young once”. “One day” is only for indeterminate future time.

The reader who pointed this out to me wondered whether the claim that “One day” is only for indeterminate future time” was a legitimate correction or, as he put it “nonsense.” I responded that I was pretty sure that “one day” was not only for future tense. The blog editors didn’t get into the grammatical issue, but changed the caption to “Adam and Eve in Paradise. The age of innocence.”

The whole exchange got me curious about the expression “one day.” The original caption “The world was also young one day” does seem a bit odd, but certainly there are plenty examples of “one day” in the past sense, for example:

One day I was out walking, and passed by the calaboose; I saw a crowd about the gate, and heard a child’s voice…

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin

One day I was drawing a picture merely to fill in a blank space in the daily cartoon.

Rube Goldberg, The American Magazine, Jan 1922, 64

One day I was down on my knees polishing a man’s shoes on State Street when I happened to look up, and there was my teacher just passing.

Eddie Foy, “Clowning Through Life,” Colliers, Dec. 18, 1926, 7

In the examples, the one day signals something that that happened in the past. Try substituting once or one time and you’ll get a different, less specific narrative effect. One day is like Once upon a time, but without the fairy-tale feel.

Curious, I checked what dictionaries had to say. The Oxford English Dictionary is clear, telling us that one day means refers to “On a certain (but unspecified) day in the past.” It gives examples from Daniel Defoe and George Bernard Shaw, among others:

One Day walking with my Gun in my Hand by the Sea-side, I was very pensive upon the Subject of my present Condition.

Robinson Crusoe, 1881

I moralized and starved until one day I swore that I would be a full-fed free man at all costs.

Major Barbara, 1907

The OED notes as well that one day can refer to something occurring “On an unspecified day in the future” like the expression someday, as in this example from Tennessee Williams’s Twenty-seven Wagons Full of Cotton:

One day I will look in the mirror and I will see that my hair is beginning to turn grey.

The key feature, past or future, seems to be the idea of an unspecified day. The OED also contrasts one day with one of these days. The latter is described as also indicating an unspecified day in the future but as often “implying a more proximate or immediate future than the equivalent use of one day.” The OED gives an example from David Lodge’s 2009 Deaf Sentence:

It wouldn’t surprise me if we both turn up lightly disguised in a campus novel one of these days.

Try substituting one day or someday here and you’ll see contribution that one of these makes.

I didn’t find entries on one day in Garner’s Modern American Usage, Merriam Webster’s Guide to English Usage, The Chicago Manual of Style, in Websters Second or Third dictionaries or in the Random House Unabridged, all of which suggests that it is not a very contested bit of grammar.

Oddly though, the Cambridge Online Dictionary gives one day only as “at some time on the future,” citing the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary & Thesaurus and the Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary.Collins Dictionary also gives one day “at some time in the future,” with no mention of the past.

Merriam Webster’s online dictionary treats one day as an idiom (perhaps to distinguish it from the literal sense of one day as “a single day”). Like the OED, Merriam gives both definitions: “at some time in the future” and “on a day in the past.”

The positioning of one day can also be a factor. When I looked through the full list of Merriam-Webster citations, I was struck by this quote from college football player Justin Dedich “My old soccer coach became the coach of pole vaulting and asked me to try out one day.” Here it is possible to associate the one day with the asking (an unspecified days in the past) or with the trying out (an unspecified day in the future, relative to the asking). The context makes it clear which is intended.

One day can refer to past or future events, and is part of a host of temporal settings phrases like once, one time, once upon a time, someday, and one of these days. Each has its own nuance.

Featured image by Marco Meyer via Unsplash.

July 24, 2025

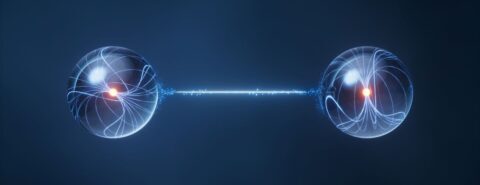

Quantum information theorists use Einstein’s Principle to solve “Einstein’s quantum riddle”

Quantum information theorists use Einstein’s Principle to solve “Einstein’s quantum riddle”

Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen introduced the mystery of quantum entanglement (entanglement) in 1935 and it has been called “Einstein’s quantum riddle.” Many physicists and philosophers in foundations of quantum mechanics (foundations) have proposed solutions to Einstein’s quantum riddle, but no solution has received consensus support, which has led some to call entanglement “the greatest mystery in physics.” There is good reason for this 90-year morass, but there is also good reason to believe that a recent solution using quantum information theory will end it in ironic fashion.

Simply put, entanglement is one way that quantum particles produce correlated measurement outcomes. For example, when you measure an electron’s spin in any direction of space you get one of two outcomes, i.e. spin “up” or spin “down” relative to that direction. When two electrons are entangled with respect to spin and you measure those spins in the same direction, you get correlated outcomes, e.g. if one electron has spin “up” in that direction, then the other electron will have spin “down” in that direction. Einstein believed this was simply the result of the electrons having opposite spins when they were emitted from the same source, so this was not mysterious. For example, if I put two gloves from the same pair into two boxes and have two different people open the boxes to “measure” their handedness, one person will find a left-hand glove and the other person will find a right-hand glove. No mystery there. The alternative (which some in foundations believe) is that the electron spin is not determined until it is measured. That would be like saying each glove isn’t a right-hand or left-hand glove until its box is opened. No one believes that about gloves! So, Einstein argued, if you believe that about electron spin, then explain how each electron of the entangled pair produces a spin outcome at measurement such that the electrons always give opposite results in the same direction. What if those electrons were millions of miles apart? How would they signal each other instantly over such a great distance to coordinate their outcomes? Einstein derided that as “spooky actions at a distance” and instead believed the spin of an electron is an objective fact like the handedness of a glove. No one knew how to test Einstein’s belief until nine years after his death, when John Bell showed how it could be done.

In 1964, Bell published a paper that tells us if you measure the entangled electron spins in the same direction, you can’t discern if Einstein was right or “spooky actions” was right. But if you measure the spins in certain different directions, then quantum mechanics predicts correlation rates that differ from Einstein’s prediction. In 1972, John Clauser (with Stuart Freedman) carried out Bell’s proposed experiment and discovered that quantum mechanics was right. Apparently, “spooky actions at a distance” is a fact about reality. Later, Alain Aspect and Anton Zeilinger produced improved versions of the experiment and, in 2022, the three shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for their work.

Given these facts, you might think that the issue is settled—quantum mechanics is simply telling us that reality is “nonlocal” (contains “spooky actions at a distance”), so what’s the problem? The problem is that if instantaneous signaling (nonlocality) exists, then you can show that reality harbors a preferred reference frame. This is at odds with the relativity principle, i.e. the laws of physics are the same in all inertial reference frames (no preferred reference frame), which lies at the heart of Einstein’s theory of special relativity. In 1600, Galileo used the relativity principle to argue against the reigning belief that Earth is the center of the universe, thereby occupying a preferred reference frame, and, in 1687, Newton used Galileo’s argument to produce his laws of motion.

Physicists loathe the idea of abandoning the relativity principle and returning to a view of reality like that of geocentricism. So in order to save locality, some in foundations have proposed violations of statistical independence instead, e.g. causes from the future with effects in the present (retrocausality) or causal mechanisms that control how experimentalists choose measurement settings (superdeterminism). But most physicists believe that giving up statistical independence means giving up empirical science as we know it; consequently, there is no consensus solution to Einstein’s quantum riddle. Do we simply have to accept that reality is nonlocal or retrocausal or superdeterministic? Contrary to what appears to be the case, the answer is “no” and the alternative is quite ironic.

The solutions that violate locality or statistical independence assume that reality must be understood via causal mechanisms (“constructive efforts,” per Einstein). This is the exact same bias that led physicists to propose the preferred reference frame of the luminiferous ether in the late nineteenth century to explain the shocking fact that everyone measures the same value for the speed of light c, regardless of their different motions relative to the source. Trying to explain that experimental fact constructively led to a morass, much like today, in foundations and here is where the irony begins—Einstein abandoned his “constructive efforts” to solve that mystery in “principle” fashion. That is, instead of abandoning the relativity principle to explain the observer-independence of c constructively with the ether, he doubled down on the relativity principle. He said the observer-independence of c must be true because of the relativity principle! The argument is simple: Maxwell’s equations predict the value of c, so the relativity principle says c must have the same value in all inertial reference frames to include those in uniform relative motion. He then used the observer-independence of c to derive his theory of special relativity. Today, we still have no constructive alternative to this principle solution to the mystery of the observer-independence of c.

The next step in the ironic solution occurred when quantum information theorists abandoned “constructive efforts” in the exact same way to produce a principle account of quantum mechanics. In the quantum reconstruction program, quantum information theorists showed how quantum mechanics can be derived from an empirical fact called Information Invariance and Continuity, just like Einstein showed that special relativity can be derived from the empirical fact of the observer-independence of c. The ironic solution was completed when we showed how Information Invariance and Continuity entails the observer-independence of h (another constant of nature called Planck’s constant), regardless of the measurement direction relative to the source. Since h is a constant of nature per Planck’s radiation law, the relativity principle says it must be the same in all inertial reference frames to include those related by rotations in space. So, quantum information theorists have solved Einstein’s quantum riddle without invoking nonlocality, retrocausality, or superdeterminism by using Einstein’s beloved relativity principle to justify the observer-independence of h, just as Einstein did for the observer-independence of c.

July 21, 2025

Why economists should learn machine learning

Why economists should learn machine learning

Economists analyze data. Machine learning (ML) offers a powerful set of tools for doing just that. But while econometrics and ML share a foundation in statistics, their aims and philosophies often diverge. The questions they ask and the tools they prioritize can differ dramatically. To clarify these differences—and the reasons economists might ultimately use ML—it helps to begin by deliberately sharpening the contrast between the two.

Quantifying vs. predictingAt its core, econometrics is about explanation. The typical economist is interested in quantifying the effect of a specific variable, often within a framework of causal inference. For example: What is the effect of raising the minimum wage on employment? Do peers influence students’ academic achievements? What is the average wage gap between men and women? These questions focus on estimating one or a few key parameters, with great attention to the rigor of the identification strategy. The emphasis is on the assumptions under which we can identify the parameters and on inference—constructing confidence intervals, testing hypotheses, and, above all, establishing causality.

This approach gained prominence in recent decades, culminating in Nobel Prizes for economists like Joshua Angrist, Guido Imbens, David Card, and Esther Duflo, whose work emphasizes empirical strategies to identify causal effects in natural, field, or experimental settings.

Machine learning, by contrast, is largely concerned with prediction. The primary goal is to develop models—or more precisely, algorithms—that deliver accurate predictions for new data points. Whether it’s recommending movies, classifying elements of an image, translating text, or matching job-seekers with firms, ML prioritizes predictive performance under computational constraints. Rather than focusing on a particular parameter, the goal is to learn complex patterns from data, often using highly flexible (sometimes opaque) models.

That said, forecasting is one area where econometrics and ML converge. Econometric forecasting often imposes structure on messy data to reduce noise, while ML emphasizes complexity and flexibility. Nevertheless, many traditional econometric tasks can be reframed as prediction (sub)problems or built upon them. Estimating a treatment effect, for example, involves building a counterfactual and is inherently a predictive exercise: being able to credibly predict what would have happened to this individual had they not been treated?

Models and assumptionsEconometric models tend to be simple, theory-driven, and interpretable. They often rest on strong assumptions—like linearity or exogeneity—that are difficult to verify but motivated by behavioral or economic theory. These models aim to isolate the effect of a particular variable, not to simulate the entire system.

In ML, simplicity is often sacrificed for performance. Black-box models, such as deep neural networks, are acceptable (and even preferred) if they generate more accurate predictions. A battery of performance metrics—like precision and recall—guide model selection, depending on the stakes. For instance, in fraud detection, a model with high precision ensures that flagged cases are likely real; in cancer screening, high recall ensures few real cases are missed.

Nevertheless, within a particular defined problem, ML offers algorithms whose predictive performance often surpass the standard (non)parametric toolkit in data-rich environments. For example, when selecting a model, they allow modeling complex interactions between variables or being robust to possibly high-dimensional nuisance parameters. The issue is that the theoretical behavior of these tools is often intractable, making them difficult to use within the classic econometric framework. Fortunately, over the past fifteen years, econometric theory has advanced to incorporate ML techniques in a way that enables statistical inference—allowing researchers to understand the working assumptions and their limits, construct tests, and build confidence intervals using ML-powered estimators.

Data and deploymentAnother important divergence lies in how data is used. Econometric models are typically built on a single dataset, intended for a specific study. Replication is possible, but each new dataset generally leads to a different model. The focus is on understanding a particular phenomenon using the data at hand.

In ML, models are developed to be deployed in production, where they will continuously generate predictions as new data becomes available. This makes it crucial to guard against overfitting—when a model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen data. This risk is mitigated by techniques like cross-validation, and by splitting data into training and test sets. Modern ML even grapples with new phenomena like “double descent” where larger models trained on more data can paradoxically generalize better.

Complex data, new frontiersML’s rise is partly fueled by its success in handling complex, unstructured data—images, text, audio—that traditional statistical approaches struggle to process. These data types don’t fit neatly into rows and columns, and extracting meaningful features from them requires sophisticated techniques from computer science. ML excels in these domains, often matching human-level performance on tasks like facial recognition or language translation. As such, ML is the key ingredient to compress or extract information from such unstructured datasets, unlocking new possibilities.

Think about it:

classifying the sentiment of an internet review on a numerical scale to enter a regression model,compressing a product image into a fixed-size vector (an embedding) to analyze consumer behavior,measuring the tone of a central banker’s speech.Text data is undoubtedly one of the richest sources of economic information that largely remains out-of-reach for traditional econometric approaches.

A two-way streetThe distinctions above are real, but they are not absolute. Economists have long used prediction tools, and ML researchers are increasingly concerned with issues that economists know well: fairness, bias, and explainability. Recent public controversies—from racial bias in criminal risk algorithms (e.g., the COMPAS tool) to gender stereotypes in language models—have underscored the social consequences of automated decision-making.

Likewise, econometrics is not immune to methodological pitfalls. The replication crisis, “p-hacking,” and specification searching can be seen as forms of overfitting problems that ML addresses through careful validation practices. Techniques like pre-analysis plans (committing to a set of statistical tests before receiving the data in order to reduce false positives) have been adopted by economists to mitigate these risks. However, possible solutions can draw inspiration from ML’s train/test split approach.

Bridging the divideSo, should economists learn machine learning? Absolutely. ML extends the standard econometric toolkit with methods that improve predictive performance, extract insights from text and images, and enhance robustness in estimation. For economists looking to stay at the frontier of empirical research—especially in a data-rich world—ML is not just useful. It’s essential.

July 16, 2025

An etymological knockout

We know that in English words beginning with kn– and gn– the first letter is mute. Even in English spelling, which is full of the most bizarre rules, this one causes surprise. But no less puzzling is the rule’s historical basis. At one time, know, knock, gnaw, and their likes were pronounced as they still are in related Germanic languages, that is, with k– and g- in the onset. What happened to those k- and g- sounds? The groups are hardly tongue twisters and give no one trouble in the middle of acne, acknowledge, magnet, and ignite. To be sure, in acne and their likes, k/g and n belong to different syllables, but one sometimes hears canoeing, pronounced as c’noeing, and the first consonant survives. Nor is the group kn endangered in the coda, as in taken and spoken. (Yet King Knut has become Canute: don’t expect justice from language!)

According to the evidence of contemporary observers, the destruction of k and g before n happened about five centuries ago, that is, shortly before and in Shakespeare’s time. Why did it? True, sounds undergo modification in the process of speech. For instance, most people pronounce a group like his shoes as hishshooz (this process is called assimilation), but kn– and gn– are word-initial groups, and no neighbors threaten k- and g-. As a most general rule, the cause of a systemic sound change is another major sound change. Obviously, this is not the case with initial kn– and gn– in English: no previous event triggered the loss of k and g before n.

A few analogs of the change in English have been found in German Bavarian dialects, but nothing even remotely resembling the loss of k and g before n has happened elsewhere in Germanic. In the remote past, many words began with hl– and hn-. Thus, listen and neck were at one time hlysta and hnecca, but h is a perishable sound, and “dropping” it causes little surprise. By contrast, k and g are sturdy. Our best books on the history of English describe in detail the loss of k and g before n but are silent on the causes.

Nor can I offer an airtight argument about why that process occurred, but I decided to look at the origin of the affected words and risk putting forward a hypothesis. Though knee and know have secure Indo-European cognates, most other items on the list are limited to Germanic. As usual, cognates shed little light on the prehistory of the words that interest us unless their senses diverge radically. In this case, they do not. Here are two instances. Knack: perhaps borrowed from Low German or Dutch; of imitative origin, because knack “sharp blow” exists, and in English (knack), we may be dealing with the same word. (German Knacks means “crack.”) Likewise, knapsack was taken over from the same sources, with knap perhaps being related to German knappen “to snap, crush”; thus, knap is a doublet of snap and snatch, both possibly sound-imitative.

The latest (cautious and conservative) German etymological dictionary says bluntly that kn– is a sound-symbolic group denoting pressure. The statement looks correct, but it is doomed to remain guesswork: since many words with initial kn– refer to pressure, we conclude that such is the nature of this group. The vicious circle in this reasoning (begging the question) is obvious. We are on safer ground with knell: all over Germanic, knell-, knoll-, and their look-alikes and synonyms are probably indeed sound-imitative.

Knitting implies increase.

Knitting implies increase. Photo by Adam Jones. CC-by-2.0, via Flickr.

Knot and knit perhaps make us think of some increase in size. Both evoke clear visual images and are thus in some way “expressive.” Knob and its near-synonym knub (both mean “a small lump”) align themselves rather easily with the rest of kn-words. The same holds for knop “a round protuberance.” The idea that Germanic kn– is expressive (whether sound-imitative or sound symbolic) is old, and I hope the suggestion I am about to advance has some merit. Couldn’t the semantics of kn-words, their constant use under emphasis, contribute to the simplification of kn-?

Every sound change has a cause, but none is necessary. The same words retained their initial kn– in Frisian, Dutch, and Scandinavian. Languages and dialects go their different ways. It is the system’s business to ignore and suppress or make use of the stimulus. The same is true of every change. For instance, some societies resolve crises peacefully, while others are famous for continual revolutions.

If my guess has any merit, it follows that once the group kn– lost its k, the non-symbolic knife (or is it sound-symbolic?!), knee, and know remained in isolation and followed suit under the pressure of the system. It would be interesting to observe whether they were indeed the last to succumb. But we cannot relive the past in such detail, and our spelling makes us blind to the change: we still write kn-, long after its loss of k. Kn- probably did not become n– as an instantaneous act: more likely, it went through the stage of initial hn-, and some kn- ~ hn– doublets indeed existed in Old Norse.

Are knives symbolic?

Are knives symbolic? Image by Michal Renčo from Pixabay.

The English gn– group is tiny: gnarled, gnash, gnat, gnaw, and a few bookish loan words: gneiss “a kind of rock,” gnome “a legendary creature,” gnosis (as recognizable in agnostic), and gnu “an African quadruped.” Gnarled is a misbegotten word, whose cognates begin with kn-. German Knorren means “knot, gnarl.” In any case, gnarled is from the historical point of view another kn-word. For the verb gnaw (Old Icelandic gnaga, German nagen) an ancient Indo-European root has been reconstructed, because similar words occur outside Germanic, but more probably, we are again dealing with a sound-imitative verb, and the same is true of gnash. It is curious that Old Icelandic gnat meant “noise.” The same is true of many Scandinavian words beginning with gn-.

In a nutshell.

In a nutshell. Image by Leopictures from Pixabay.

Incidentally, n- in the verb neigh goes back to Old English hn-, and we witness a curious set of variants: Old Icelandic gneggja, Modern Icelandic hneggja, and Swedish gnägga versus Swedish regional knäja. This unexpected variation perhaps confirms my guess that however English kn– may have lost its k, it went through the stage hn-. At present, English has retained initial h before a consonant only in the speech of those who distinguish between witch and which, but hn-, hl, and hr– are the norm in Modern Icelandic.

If some students of the history of English sounds happen to read this blog, it would be interesting to know their opinion about my hypothesis. Here it is in a nutshell: English words with kn– and gn– lost their k/g under emphasis, because nearly all of them had a strong expressive character.

Editor’s Note: We’re taking next week off, but Anatoly will be back the following week with a new post!

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers