Oxford University Press's Blog, page 8

March 12, 2025

Witches and witchcraft

Right after the appearance of the post on hag (March 5, 2025), I received a letter with a question about the origin of the word witch. Initially, I wanted to point to my old post for October 24, 2007, but then thought better of it, and I would like to explain my reasons, even though this untraditionally long introduction will take me too far. The column “Oxford Etymologist” (title and all) appeared for the first time on March 1, 2006, many years and many editors ago. It was part of a series of blogs, launched by Oxford University Press. (Incidentally, responding to an often-asked question, I hasten to state that the bloggers for OUP are not paid.) The format was new and had to be worked out. I suggested weekly installments, and we decided that each post would be one page long and that I would devote every fourth essay to the answers and comments, inspired by the first three. This format stayed unchanged for a long time (hence “Monthly Gleanings”). In the past eighteen years, I have not “recycled” a single essay, that is, never smuggled a slightly changed old piece as new, in the hope that the fraud would not be recognized.

The number of essays, published since 2006 and 2007, is slowly approaching 1,000. Over the years, the number of my readers has fluctuated between several hundred and more than a thousand, though “thousands” appeared only if I dared discuss some unprintable word. Along the way, there also were several innovations. One day, I wrote about something the adjective teetotal, and a letter came from Great Britian with a picture of a monument of Richard Turner (Preston, Lancashire), allegedly the first teetotaler. Much to my regret, I cannot find this post, though I have searched for it more than once. Anyway, when the letter arrived, I asked my editor (I still correspond with her every now and then, and it was she who recorded my short presentations about etymology for OUP in New York) whether it was possible to reproduce illustrations, and it turned out to be an easy task.

With time, the present-day format became the norm: a picture in the header, and three images in the text. Few people may realize how hard and time-consuming it is to find appropriate images (some essays do not presuppose any!). Usually I suggest the ideas, and the editor spends a lot of time following my timid suggestions. Then we discuss the options, and the result is the final product, posted on Wednesday. Incidentally, later, we sometimes also added music. I remember distinctly that we once had “The Flight of a Bumblebee” (but there were others). Much to my surprise, no one expressed any feelings about this bold innovation. Today, listen to Mussorgsky’s “Night on Bald Mountain” and enjoy. The piece is about witches, a version of Walpurgis Night.

In comparison to 2006, my correspondence has shrunk, and the “gleanings” have almost died. At present, those who are interested in word origins can find answers online (this was impossible two decades ago) and may not need my explanations. That is why I treasure every comment and every message. (However, books on etymology sell well!) As I have mentioned more than once, my main consolation is that I am not infallible (few people are), and every time I make a mistake, I am hauled over the coals. The corrections are usually testy but moderately polite. Just once, many years ago, I received a letter telling me that my discussion of the object at hand showed such depths of ignorance that the respondent could only throw up his (or was it her? I forget) hands in despair. There was some truth in that statement, though it pertained to history, not to etymology. As regards word origins and language usage, I manage to hold my own reasonably well.

And now I can explain why I decided to write a new post on witch. My old one-page essay on this word is not only short: it is skimpy. I reread it and decided to return to this subject. Though I devoted a detailed essay on witch in An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction, that essay is technical and addresses professional linguists. Also, the OED online does not commit itself to a definitive etymology of witch, while Etymoline mentions my contribution but does not summarize it (I see no point in this format). This then is a thank you note to my correspondent interested in the origin of witch, and as an additional gift to her, I’ll reproduce one more etymology of hag (I did not mention it last week).

It will be remembered that hag is usually believed to be a stump of an old compound (thus, the oldest recorded German form is hagazussa). In the previous post, I explained my reasons for disagreeing with this reconstruction. Here is a little-known suggestion by the Swedish scholar Erik Bergkvist (1937). He combined hag-, allegedly, “wolf; a shaggy creature,” and zussa “a kind of cloth” (named after its fabric: Old English tyse did mean “coarse cloth”) and obtained the gloss “a person in wolf’s clothing,” like Old Icelandic úlfheðinn “wolf cloak,” or berserkr “berserk,” if the Icelandic word can be understood as “bearskin,” rather than “bare-skin.” The question about the origin of berserk has never been answered to everybody’s satisfaction.

Walpurgis Night.

Walpurgis Night. A scene from Faust. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Old English wicca ~ wicce “witch,” though not a compound, does go back to a form longer than the one attested in the extant texts. Bergkvist’s almost fanciful suggestion may be a mere curiosity, but it brings us to one of the central questions of etymology. In order to know the origin of the word, we have to know what the word meant. This thesis sounds trivial, even silly. But of course! Well, no. For instance, the etymology of bed is so complicated, because we are not sure what object was once called bed. Our modern beds are a rather late invention (remember the biblical phrase: “Take up thy bed and go”? What did the sick man “take up”? Another version has: “Pick up thy mat”!), though flower beds are indeed ancient. What was the earliest reference we need today, that is, who was called a witch?

The range of powers attributed to witches in the Middle Ages and later, was wide. It went all the way from divinators (that is, sorceresses) and (presumably) wise soothsayers to charlatans and evil creatures, associated with the Devil. To repeat: what powers were attributed to witches? In a memorable Old Scandinavian myth, the god Othinn makes a dead seeress rise from the grave and prophesy. Was she a witch? In any case, today, as regards etymology, neither the folklore witch on a broom nor a creature sitting on a fence (discussed in detail in the previous post) will take us too far. From Old English texts, we have rather numerous examples of how learned people translated difficult Latin words into their native language, and we know which Latin words were glossed as “witch.” The variants are suggestive, but we cannot decide how those people understood the Latin words they saw. Those also had to be interpreted. Everybody more or less knew what was meant, but the Latin glosses (that is, translations of the word) fail to solve our problem. It is amazing how many etymologies of witch have been offered. We’ll look at them next week and decide whether we have made progress since the seventeenth century. If we ignore Isaac Casaubon (1554- 1614), our earliest source goes back to 1617.

Our modern idea of the Scandinavian völva. Via Picryl.

Our modern idea of the Scandinavian völva. Via Picryl.Featured image: Photograph by Soenke Rahn. Witch weather vane on the gable of Siemers Antik und Cafe near Finisberg (Flensburg April 2015), picture 05. CC BY SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 5, 2025

The hag’s revenge and vindication

The hag’s revenge and vindication

This is an essay on the word hag, but let me first thank those who have commented on the latest posts, corrected the mistakes, and made suggestions. I would also like to explain why I translated elf-shot as “lumbago”: this is how Elfschuß is glossed in at least some German dictionaries. In the Middle Ages, “Germanic” elves (not to be confused with the “Celtic” elves of Midsummer Night’s Dream) were believed to inflict all kinds of diseases, and German Alptraum “nightmare” (Traum “dream”) points in the same direction (-mare in nightmare is the name of another evildoer, prominent in old superstitions). I do not know why German authorities associated elf-shot with lumbago. Our information on elves is scanty. Once upon a time, as follows from the evidence of Old Icelandic poetry, they were equal to the pagan gods, known as Æsir (Thor, for instance, was one of them). This follows from the Old Icelandic alliterating formula: “How is it with the Æsir, how is it with the elves?” (The backbone of Old Icelandic and of the rest of Old Germanic poetry was alliteration, not rhyme, and all vowels were allowed to alliterate with one another. Hence the pairing off of æ and e).

Helpful elves.

Helpful elves. Image via Thomas Quine on Flickr; CC by 2.0.

Snorri Sturluson, our greatest authority on Scandinavian mythology from the thirteenth century, knew nothing about elves beyond the existence of two groups: light elves and dark elves. He was, however, fully aware of the popularity of elves in folk belief. They seem to have been a group of tutelary (guardian) spirits, kind, when treated with respect, and vengeful if offended.

Next to nothing is known about the etymology of elf, and the same holds for the “proto-hag,” the heroine of this post. The word surfaced as hegge ~ hagge in the thirteenth century but was rare for the next three hundred years. As suggested by the OED, “witch” (or “a female evil spirit”), the gloss, usually given as the earliest sense of our word, may be a secondary sense. Indeed, nothing is easier than to call a repulsive (cantankerous, querulous, vituperative—add more synonyms if you care) female a witch, and I would like to propose that such was indeed the case. I would even like to strengthen this suggestion and say (pointblank, as it were) that hag never meant “witch” in English. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (1966) gave as the earliest sense of hag “female evil spirit.” Very probably, this sense did not exist.

A somewhat modern idea of a hag.

A somewhat modern idea of a hag. From Irish Fairy Tales, 1920, illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The main theme of the extremely rich literature on the origin of the word hag resolves itself into the idea that hag is related to German Hexe and Dutch hecs “witch.” In written texts, Hexe emerged as hagazissa, obviously, a compound word (haga-zissa). It must have been very common if it lost half of its bulk with time. (The more frequent a word is, the easier it is for it to contract.) The Old English cognate of hagazissa is hægtesse ~ hegtes. Likewise, Dutch hecs “witch” goes back to haghetisse.

In a nutshell, the traditional conclusions about the etymology of hag are as follows. In the compounds cited above, the first half is related to the nearly forgotten English noun haw “fence” (from haga) but recognizable in hawthorn (which, too, would have been unknown to many, but for the last name Hawthorn) and hedge (from hegg ~ hecg). The second part of the compound (-tisse ~ –zissa) is almost hopelessly impenetrable, and most efforts have focused on its meaning and origin. However, the oldest recorded English forms of hag (hegge ~ hagge) have no traces of it, and we might have ignored it, but for one circumstance.

It is usually believed that hag also goes back to a compound like the Dutch and German words cited above, but that in English, this second part disappeared without a trace. The inspiration for the etymology of the Dutch-German word is Old Icelandic tún-riða (ð has the value of th in English the), with an exact analog in Middle High German. The word meant “fence-rider” (tún is of course a cognate of English town) and “witch,” because witches were supposed to rule fences, perhaps in the capacity of spirits from the wood, rather than “witches.” For millennia, separating inhabited spaces from the surrounding wilderness (forests) was a most important part of civilized life.

Certainly not a medieval witch guarding a fence!

Certainly not a medieval witch guarding a fence! The witch outside Witches Galore at Newchurch in Pendle. © Marathon, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Geograph.org.uk.

In the linguistic literature on hag, beliefs and superstitions have been discussed in an exemplary way, but all attempts to solve the riddle of hag traditionally turn around the meaning of the second component of the old compound. However, as noted above, we may perhaps ignore that part and the rich scholarship connected with it, because the English word has never been recorded with it. Its presence is a mere guess. I would risk suggesting that hag has nothing to do with German Hexe and its Dutch cognate. (Hag, “broken moss ground, etc.” is a different word, related to hew, and need not bother us.)

Hag, as we have seen, surfaced in English comparatively late and for a long time occurred very rarely. When it did turn up, it was hagge, and final –e is a mere ending (perhaps a letter not reflecting any pronounced sound), certainly, not a trace of a discarded component. The Dutch and the German words have also shrunk, but not so dramatically. In principle, shedding the entire second part of a compound is not impossible. Thus, hussy ~ huzzy, which is another term of abuse for women, goes back (surprisingly!) to the perfectly respectable word hūswīf “housewife.” But usually something is left of the discarded stump, as in husband (from hūs-bonda “master of the house”) becoming hubby.

If hag is not a stub of an old compound, what can it be? English words ending in g (like big, bag, bug, bog, dig, egg, cog, log, flog, fog, grog, and many others) are rarely old, and if they are old (like pig, hog, frog, and dog), they pose great difficulties to etymologists. Here are a few words rhyming with hag (the numbers refer to the century of the first attestation in texts): bag (XIII, borrowed), brag (see my post for October 2, 2013), crag (XIII, borrowed), fag (late, much discussed, including in An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology), flag (all homonyms are relatively late and of dubious origin), nag (very late, of unknown origin), rag (several homonyms, late or borrowed), snag (late, of unclear origin), stag (apparently native; obscure, like dog, frog, and a few other animal names of the same type), and tag (late, of unknown origin). Only shag (as in shaggy) is old and native. Also wag (verb, XIV) is native and may be a sound–symbolic formation. I suspect that hag belongs with fag, ragtag, and other words denoting undignified creatures. A word like hag seems to have grown on the rich soil of informal, unbuttoned English slang. It would be a relief to stop bothering about German and Dutch witches, hedges, and other matters that increase the bulk of publications on the etymology of hag but do not advance the subject at hand. Obviously, I am not so arrogant as to believe that I have solved an almost insoluble riddle, but perhaps my approach has some merit. It would be interesting to hear from our readers what they think about this etymological heresy.

Featured image: Illustration by Arthur Rackham from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 3, 2025

Does it matter if what I do doesn’t make a difference?

Does it matter if what I do doesn’t make a difference?

Moral vegetarians think that we should not eat meat because doing so wrongfully harms animals. One response is that, in any typical case, purchasing and eating meat will do no harm. The animal has already been killed, and markets are not so sensitive that an individual purchase or meat meal will lead to additional animals being killed.

This is one kind of case in which it seems that one’s actions are inconsequential, even though the aggregation of all such actions causes immense harm. This is sometimes called the problem of “causal inefficacy.” The same problem arises with carbon emissions. Taking a drive or a flight seems to make no difference to global warming, and yet we know that the sum of all carbon emissions is wreaking environmental havoc.

Does the apparent harmlessness of our individual actions mean that they are morally permissible? In arguing that they are not, some philosophers have noted that there is a difference between an action making no difference and an action making an imperceptible difference. The aggregation of actions which make no difference will also make no difference. Because the aggregation of meat purchases and carbon emissions makes a big difference, it cannot be the case that all the individual actions make no difference.

This does not prove that every individual action makes an imperceptible difference. It is still possible, even likely, that some individual actions make no difference at all. There may still be moral reason to desist from such actions. First, we do not know which of our individual actions will have an imperceptible effect, and which will have no effect. Second, even some actions that have no (direct) effect do contribute in some sense to the overall problem. For example, performing the action can contribute to normalizing meat purchases or flying.

That said, having a moral reason to desist from an action does not mean, by itself, that we have an all-things-considered duty to refrain from performing the action. Whether there is such a duty requires us to consider other factors. When we do that, we find that despite the similarities between a meat purchase and a flight, there are also important differences.

One difference is that driving or flying can sometimes have important benefits, whereas the benefits of eating meat are typically negligible. To be sure, some drives and flights are frivolous, and we have stronger reason to desist from those, but some are necessary to get to work, to purchase food, or to reach a loved one in need. Some people enjoy the taste of meat, but eating animal flesh is generally not nutritionally necessary. It is normally healthier to eat less of it.

Arguably even more important is the difference in how the problem of causal inefficacy arises in different cases. In the case of carbon emissions, the harm arises only as we scale up the emissions. If your flight was the only one, there really would be no problem. Global warming only results from the aggregation of flights and other emissions.

By contrast, in the case of eating meat, the harm is obscured as one scales up. When an individual meat meal requires killing an animal, the causal connection between the harm and the meal is patent. That connection becomes obscured when meat production reaches industrial proportions.

Consider an analogy involving a human victim. Imagine that a slaveholder acquired a taste for human tears. He flogs his slave and collects the tears that he then imbibes. That would clearly be wrong. Imagine next, that the taste for human tears grows. There is now an industry of slave flogging and tear collection. A customer in the lachrymal aisle of the local grocery store now faces the decision whether to purchase a vial of tears. May he do so, given that his purchase would make little or no difference to the harm that has been or will be done?

A positive answer, I suggest, would be sophistry. If the individual action is impermissible, then it does not become permissible merely because millions of others with similar tastes have collectively generated a causal inefficacy problem.

This does not mean that we may emit carbon with abandon. The fact that millions of other people are also emitting, and that this collectively is causing harm, provides one with a reason, even a duty, to limit one’s emissions. However, that is different from not emitting at all. Because any flight, by itself, is harmless, the total emissions need to be reduced. Individuals have duties to contribute towards this reduction, but that reduction need not be to zero.

Thus, while both eating meat and carbon emissions are alike in manifesting the problem of causal inefficacy, there are also key differences between the two cases. The similarities are what explain why, in both cases, individuals have duties to reduce either consumption or emissions. The differences explain why the extent of the duty varies. Individuals are not duty-bound to be carbon-neutral, although such a reduction would be praiseworthy. By contrast, individuals do have a moral duty to abstain completely from eating meat.

Featured image: Het slachthuis by Willem Bastiaan Tholen (1860-1931). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 2, 2025

Making economics more human

As the “official doctrine of neoclassical economics, enshrined in all respectable textbooks,” the esteemed game theorist Ken Binmore says, revealed preference theory “succeeds in accommodating the infinite variety of the human race within a single theory simply by denying itself the luxury of speculating about what is going on inside someone’s head. Instead, it pays attention only to what people do.”

So great is its reach that it doesn’t stop with the entire human race. The first papers on experimental economics I ever read as an undergraduate were about how pigeons and rats exhibit ordered preferences and downward-sloping demand curves. How absolutely thrilled was I to learn that I could apply intermediate microeconomics to the entire animal kingdom.

Economists and our students alike read Binmore’s statement and nod in agreement. It doesn’t seem to occur to us, as economists, to question what we ask of our first-year students: What are the benefits and costs of stretching a theory to accommodate all forms of human and animal life? Mid-twentieth-century economists like Paul Samuelson and Hendrik Houthakker developed the tool of revealed preferences to organize consumer behavior in markets. They were interested in the orderly way that consumer purchases change when budget constraints shift. They were not interested in why people switch from butter to margarine when the price of butter increases, just like the experimental economists Ray Battalio and John Kagel were not interested in why a rat switches from Tom Collins mix to root beer when the number of lever presses for Tom Collins mix increases.

Lest I be misunderstood, let me clearly state upfront, for the record, that utility maximization is both important and useful for understanding economics. But let’s also be clear-eyed and honest about its usefulness. Utility maximization is not a sufficient foundation for understanding economics. Economists designed the utility maximization problem to explain intelligible economic consequences—that is, outcomes and outcomes only. The tool provides answers to questions like: What happens to a consumer’s purchases when the price of a good increases? How much of the change is due to their purchasing power, and how much is due to switching to cheaper alternatives?

Economics, however, omits something rather important—namely, that which makes us human—when we do not study ourselves as purposeful beings. If a captor offers us either root beer or Tom Collins mix for pressing a lever, sure, to an observer from Mars, we would look just like a rat in a cage and prefer root beer to Tom Collins mix if and only if we choose root beer over Tom Collins mix. But to state the obvious, we, as human beings in our everyday lives, do much more than simply prefer good B to good A if and only if we choose B over A.

Human beings make meaningful decisions. We understand what one another does as intelligent conduct. We make sense of what people do by what they feel, think, know, and want. Human beings value A in the moment and value B in the future, and we imagine how good it would be for us to have B but not A in the future. We jointly imagine a better future and exchange A for B with another human being.

Human beings are the only species that routinely exchanges one thing for another thing, and all human communities do this. Primatologists have tried their hardest to create the conditions for captive chimpanzees to trade fruit they liked less for fruit they liked more. But chimpanzees would not give up something in this moment for something else they favored more in the next moment. For chimpanzees, there is no favored fruit in the future. There is only now and the fruit in their physical possession now.

Humans stand alone in nature as beings who purposefully turn natural-born enemies into exchanging friends. Humans stand alone as beings who deliberately extend their own average life expectancy and intentionally decrease their own rate of infant mortality. Humans stand alone as beings who actualize healthier and more comfortable lives for themselves. Humans are a marvel. We … are a marvel! Understanding humankind’s place in the world is key to understanding why economics is necessary to explain the wonder and surprise of the human condition.

Our common humanity tends to get lost, however, in modern social science. We doggedly search for quantitative differences among people—statistically significant differences, of course. The very foundation of economics, however, is about what all human beings do, a point that seems to go unmentioned in every principles of economics textbook. As Adam Smith clearly recognized, the nature and causes of the wealth of nations, however, rests on “the certain propensity in human nature … to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.” What sets us apart is not just what we choose or trade, but that we choose to trade—purposefully, imaginatively, and with an eye toward a future that only human beings can envision.

Featured image by sydney Rae on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 1, 2025

Five inspiring biographies for Women’s History Month [reading list]

Five inspiring biographies for Women’s History Month [reading list]

In honor of Women’s History Month, we are celebrating the lives and legacies of inspiring women that played path-breaking roles in shaping philosophy and literature. This reading list features five books that amplify the achievements of these women who were either overshadowed by men, or subject to hierarchical thinking. As we work to accelerate action for gender equality these five biographies show a defiance against systemic barriers and biases faced by women, both in personal and professional spheres. From the engrossing biographies of famous literary authors, to the eye-opening accounts of female thinkers who were silenced by the social norms of the times, these books are sure to inspire action, equality, and inclusion.

1. The Enlightenment’s Most Dangerous Woman by Andrew Janiak

Just as the Enlightenment was gaining momentum throughout Europe, philosopher Émilie Du Châtelet broke through the many barriers facing women at the time and published a major philosophical treatise in French. Within a few short years, she became famous. This was not just remarkable because she was a woman, but because of the substance of her contributions. However due to the threat that she posed, the men who created the modern philosophy canon (primarily Voltaire and Kant) eventually wrote Du Châtelet out of their official histories – her ideas were suppressed, or attributed to the men around her, and for generations afterwards, she was forgotten.

2. Bright Circle by Randall Fuller

Transcendentalism remains the most important literary and philosophical movement to have originated in the United States. Most accounts of it, however, trace its emergence to a group of young intellectuals (primarily Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau) dissatisfied with their religious, literary, and social culture. Yet there is a forgotten history of transcendentalism—a submerged counternarrative—that features a network of fiercely intelligent women who were central to the development of the movement even as they found themselves silenced by their culturally-assigned roles as women. Many ideas once considered original to Emerson and Thoreau are shown to have originated with women who had little opportunity of publicly expressing them.

3. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Very Short Introduction by E.J. Clery

Mary Wollstonecraft is widely hailed as the mother of modern feminism. The book that made her famous, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, is a work of worldwide renown. Yet the range of her achievements as a thinker and writer reaches far beyond this text. She was a multi-faceted author, and although the condition of women was a constant preoccupation throughout her life, she wrote on a wide variety of topics and in a range of literary forms, some of which she created herself. This Very Short Introduction examines the conditions for Wollstonecraft’s emergence as a feminist, but also her status as an educator, a political thinker, and a romantic.

4. Octavia E. Butler: H is for Horse by Chi-ming Yang

The figure of the horse, at once earthly and transcendent, represented the contradictions of freedom and captivity that enabled young Octavia to develop her nuanced sense of voice and place. Drawing on previously unknown archival research, this volume illustrates how Butler’s development as a writer was tied to her extraordinary resourcefulness and self-awareness growing up as an awkward, bookish Black girl in segregated, Cold War Pasadena. She persistently re-visited and revised her early writings on teenage angst, Martians, Westerns, and racial politics. In one way or another, her supernatural characters defied the constraints of gender, race, and class with equine-inflected resilience.

5. Marion Milner: On Creativity by David Russell

The British essayist, artist, and psychoanalyst Marion Milner thought deeply about how reading, drawing, and getting better related to each other. The guiding question of Milner’s life was of how people come to feel alive in, and feel creatively responsive to, their own lives. In pursuit of this, Milner explored fields as diverse as anthropology, folklore, education, literature, art, philosophy, mysticism, and psychology. She became one of the twentieth century’s most extraordinary thinkers about creativity. Key to all her writing is her search for creative practices of attention and how the interplay of past and present selves, allows us to find new ways of looking at, and experiencing, the world.

For more titles, you can also view our extended list on Bookshop:

Bookshop UKBookshop USFeatured image created in Canva.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 27, 2025

Elizabeth Taylor’s working women

Elizabeth Taylor’s working women

In the 1950s and 1960s, actress Elizabeth Taylor (1932-2011) was one of the most famous women on earth, someone to put alongside Queen Elizabeth II and Jackie Kennedy. Her complex marital history, many health crises, and love affairs were the stuff of front page headlines. She was, by any standard, the personification of the larger-than-life celebrity movie star. As a result, her long film career, for all its highs and lows, has not received the attention given to her private life.

When her career is unpacked, the results are surprising. Despite her long grip on media and public fascination, her acute business sense, native intelligence, and unflagging ambition, Taylor did not often play women of social or political power. In fact, her characters were rarely even employed. As the daughter of a well-connected Beverly Hills art dealer, Taylor was always privileged, and the public’s knowledge of that spilled into expectations of her film roles. Following her childhood stardom as plucky young heroines in such films as Lassie Come Home (1943) and National Velvet (1944), she blossomed into a young woman ready for suitors or husbands, if not careers, in Life with Father (1947), Julia Misbehaves (1948), Little Women (1949), and Father of the Bride (1950).

Taylor was a mere 17 when her home studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, cast her as a married woman in Conspirator (1949). She was heartachingly beautiful as a socialite in A Place in the Sun (1951) and as expatriated brides in Elephant Walk (1954) and The Last Time I Saw Paris (1954). Still she was somebody’s wife in many of her most acclaimed performances, including Giant (1956), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966). The trend continued, often accompanied by a neurosis or two, in Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), The Comedians (1967), X Y & Zee (1972), and Ash Wednesday (1973).

None of this is to say Taylor’s characters were idle, housebound, or subservient. Her fiery spirit and tendency toward confrontation wouldn’t allow it. Her women usually or always found ways to maximize their power and self-determination in a society hellbent on their subjugation. As early as National Velvet she was gleefully breaking rules, even cross-dressing for the film’s climactic scenes, and audiences cheered her for it. In Conspirator, when she learns her husband is a spy, she brazenly taunts him for his ethical misconduct. She rolls up her sleeves and risks everything during a cholera outbreak in Elephant Walk. In Giant, she plays the wife of a wealthy rancher and sets about to reform all of Texas in the ways of sexism, racism, and classism, joking with her husband that he “knew what a frightful girl I was when you married me.” Taylor never made her characters self-righteous or smug, but rather wholly committed to fulfilling their beliefs. Even in Suddenly, Last Summer (1959), she plays a quite sane mental patient who exposes the insanity and avarice in others.

What, then, did Taylor’s “working women” actually do when they were getting paid? A quick survey is telling. She played a dance instructor in Love Is Better Than Ever (1952), patiently guiding her young pupils in the art of rhythm and motion. She was a painter-sculptor in The Sandpiper (1965), defiant against the prescriptions of a restrictive society. She played a chorus girl in The Only Game in Town (1970), a waitress in Hammersmith is Out (1972), and an opera singer in Young Toscanini (1988), the later role accompanied by the expected preening and ego flares.

Taylor won an Oscar as a prostitute in BUtterfield 8 (1960), though she refused money from her johns in an ultimately futile effort at autonomy. She again played prostitutes in Secret Ceremony (1968) and Under Milk Wood (1971), though both were more gothic and poetic than her rather more lurid turn in BUtterfield 8.

On at least six occasions she played an actress: The V.I.P.s (1963), singing “Send in the Clowns” in A Little Night Music (1977), The Mirror Crack’d (1980), There Must be a Pony (1986), and Sweet Bird of Youth (1989), the last two made for television. Something about performing and her unending role as celebrity made actresses a good fit for Taylor. In her amusing cameo in the political thriller Winter Kills (1979), she plays a brothel madam and an actress-movie star.

Taylor’s eponymous epic Cleopatra (1963) was her one spectacular exception in a film that allowed her to negotiate and out-maneuver men on the highest level. But she is brought down by her fragile womanliness and her capacity to fall in love. “Without you, Antony, this is not a world I want to live in, much less conquer” she says soon before that fatal bite of an asp.

It’s remarkable that this protean actress and ultimate movie star so often played women lacking authority outside their domestic sphere. Yet Taylor’s film legacy includes a general memory of her characters’ ferocity, moral certainty, and sheer charisma. Many of her characters chafed at entrenched sexism and social inequities, but neither they nor Taylor herself were defeated by them.

Featured image of Elizabeth Taylor and Spencer Tracy in Father’s Little Dividend (1951). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 26, 2025

A wary approach to hemlock

Today’s story is about a deadly plant or rather, about its moribund etymology. And yet, when you reach the end, the word’s origin may appear somewhat more transparent, even though the plant will remain as deadly as ever. Hemlock, like dwarf, which I discussed in the post on February 12, 2025, has fallen into the etymological black hole. Today, few people would probably have recognized the very word hemlock if hemlock had not figured so prominently in the execution of Socrates. However, some might recall the 1952 novel Hemlock and After by Angus Wilson. It is amusing to observe how some books and films that once caused sensations, shocked audiences, and were even banned to protect the innocent, now seem harmless. The age of innocence is now behind us, and Socrates has for a long time been recognized as one of the most revered philosophers of all ages. But to return to our turf. Though hemlock is a very old word, dictionaries have little or nothing to say about its origin.

A sculpture of Socrates by Mark Antokolsky.

A sculpture of Socrates by Mark Antokolsky. Photo by Paradise Chronicle, CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Two main Old English variants of this plant name have come down to us as hymblicæ and hemlic. The b in hymblicæ is, most probably, not an inserted “parasitic” sound, as, for example, in nimble (from Middle English nemel) and fumble (from fummeln), but since its presence does not affect our understanding of the origin of hemlock, it will be left out of discussion. Our concern is the meaning of the root hem– and the suffix –lock, especially now that we know that this -lock goes back to –lic (see the two Old English forms, cited above). As usual, the first step in the search will be for the word’s possible cognates (or congeners, that is, related forms). A fully isolated old word rarely reveals its past.

Adam and Eve in Paradise. The world was also young one day.

Adam and Eve in Paradise. The world was also young one day. David Teniers the Younger. Public Domain via The Met.

Judging by the state of the art, hemlock is indeed isolated. However, it does have at least one overlooked cognate. I discussed it in An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology (2008). In Old High German, hemera “hellebore” is the name of another toxic plant. Though in German, it is also isolated, its cognates outside Germanic, namely, in Slavic and Baltic, have been found. They mean “misfortune; poison; bitterness; chagrin, disgust; fury; puss in a wound; gall; castrated ram; rebellious, evil; to hinder” or are the names of some devilish creatures in folklore—quite an array. The ancient Germanic root of both (!) hemlock and hemera is hem-. In Slavic and Baltic, kem– corresponds to hem- by the First Consonant Shift, so often evoked in this blog (compare what, from hwæt, and Latin quod, that is kwod, the same meaning). The most probable meaning of hemlock and hemera was “poison.”

The second element of hemlock is as obscure as the first. Two more plant names—charlock and kedlock—have the same suffix. Kedlock sometimes functions as a synonym of charlock and sometimes signifies “white mustard.” In both, the ancient suffix is –lick (from –lic). We observe the same suffix in barley, which began its life in English as bærlic. The origin of suffixes is often hard to explain. For example, take changeling and gosling. The roots are transparent (from change– and goose-, the latter with a shortened vowel), but what is –ling? We know that –ling is historically l + ing. But why were those sounds and sound groups chosen for naming diminutive creatures? Our chances of deciphering –lock from –lick aresmall, but at least we have found the oldest form of hemlock.

Another word that throws some light, however dim, on our word is Schierling, the German name for hemlock. The suffix –ling is common in German plant names, especially in the names of various mushrooms. It is a contraction of –l and –ing(a). Apparently, in the past, –ling alternated with –ig in plant names, at least in English. For instance, ivy goes back to īf-ig. Once again, we witness a sound group, whose ancient meaning remains impenetrable. What did –ing and- ig signify? At one time, all suffixes must have meant something. For example, it is gratifying to learn that –ly in adverbs like fully and wholly goes back to a word meaning “like.” (Think of our ineradicable like in sentences like (!) “The room was, like, empty, when I got there.” Is this how people spoke several millennia ago? Then short words shrank even more and became suffixes? Have we relapsed into our linguistic infancy? Very likely.)

Rather probably, hemlock goes back to hem-l-ick, a variant of hem-l-ing or hem-l-ig. In any case, leek, which appears in garlic (from gar– “spear” and leek) has nothing to do with our story. For some reason, the suffix (or rather a sum of two suffixes) -l-ic has been recorded only in Middle English hemlic and cyrlic. Quite early, approximately by the year 700, this suffix had become unproductive, that is, no new nouns were formed with it. When left in the dark, speakers often try to make sense of the words they use and are happy to alter them and thus make them look transparent. The result has nothing to do with true history. For instance, bridegrooms are not grooms (-groom is a replacement of a word meaning “man”), while bridal does not have a seemingly innocuous suffix (as in arrival and acquittal): in the past, it was ealu “ale,” with reference to a feast: bridal first emerged as a noun!

The dead suffix –lic, which must have meant something when it was coined, yielded to –lock, which did not fit this context but provided a semblance of common sense. The same happened in wedlock (in which the ancient suffix –lāc meant “play, sport”). Wedlock, with its –lock, seems to make perfect sense, but providing sense is of course what folk etymology is for. If Walter W. Skeat’s explanation of fetlock from fet-l-ock (with a double suffix) is correct, we have a case, reminiscent of hem-l-ic. Obviously, we still have no idea why the innocent-looking syllable kem– (Germanic hem-) was chosen to name all kinds of deadly things.

In Old English, the plant name hymele “hop” was recorded. It also had a variant with b after m. But this plant and the word seem to have reached Europe from the East, whereas hemlock is a native plant, and it is most probable that it has nothing to do with hop and that its name is also native. To quote Skeat, the first syllable of hemlock meant “something bad,” while the second is a suffix, whose meaning was forgotten even before the settlement of Britain by Germanic tribes. Thus, it seems that we do know something about the etymology of hemlock. Yet it is still reasonable to stay away from the plant.

Here are the images of hemlock, henbane, and hop, three characters of today’s story.

Here are the images of hemlock, henbane, and hop, three characters of today’s story. Hemlock, henbane, and hop, CC0 via rawpixel.

Featured image: poison hemlock, conium maculatum L. Photo by Eric Coombs, Oregon Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org. Via Wikimedia Commons, CC by 3.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 25, 2025

Moby-Dick and the United States of Aggrievement

Moby-Dick and the United States of Aggrievement

Like the white whale itself, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851) seems ubiquitous across time. For nearly a century, readers have turned to Captain Ahab’s search for the whale that took his leg to understand American crises. During the Cold War, commentators debated Ahab’s Stalin-like powers. After the September 11 terrorist attacks, the question of vengeance took center stage. Was Ahab Mohammad Attah crashing an American Airlines jet into the World Trade Center’s North Tower, or was he George W. Bush searching for weapons of mass destruction in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq?

Donald Trump’s return to the presidency offers a different question about Melville, domination, and US political life: How do Americans gain power by claiming that they have been wronged? Trump continues to shatter political norms, but complaining about mistreatment is part of the nation’s DNA. As erratic and self-indulgent as it may be, Trump’s sense of injury stretches back to the series of grievances that the Declaration of Independence itemized about King George III.

The first Trump administration cultivated comparisons to Andrew Jackson, the populist president whose election proclaimed the rise of the self-determined white man. Look behind the myths of Jacksonian democracy, however, and you will find a nation of teeming resentments. A nineteenth-century visitor observed that Americans had an unusual fondness for lawsuits and cheerfully took each other to court. Alexis de Tocqueville noted that while Americans were initially difficult to insult, their resentments, once ignited, took a long time to burn out. Ralph Waldo Emerson famously begrudged every dollar he gave to charity as an infringement on his “manhood” and individuality.

Against this backdrop Melville imagined Captain Ahab’s ruinous quest. The feeling of perpetual grievance animates the captain’s violent path through the world. “I’d strike the sun if it insulted me,” he tells Starbuck, warning the First Mate that power resides in collecting real and imagined wounds. Ahab seems so difficult to resist because the crew believe that in seeking retribution for his injuries, they will get justice for their own. Historian Timothy Snyder has used the phrase “anticipatory obedience” to describe the way populations capitulated to twentieth-century authoritarians without being asked or forced. Melville depicted this phenomenon a decade before the Civil War. Starbuck openly challenges Ahab’s desire for revenge, but with profound dread, he feels himself already succumbing to the captain’s “lurid woe.”

It is hardly surprising that the authoritarian-loving Trump employs the language of vengeance that Moby-Dick so brilliantly explores: “I am your justice,” he told the Conservative Political Action Conference in 2023. “And for those who have been wronged and betrayed: I am your retribution.” Trying to explain Trump’s appeal, pundits have identified multiple resentments among the white working class, but they should look deeper into his supporters’ belief that, long before the assassination attempts, he had been flagrantly wronged. Trump is a convicted felon, an accused sexual predator, a billionaire who ignores bills, accountability, and the most basic laws. For decades, he has ruined people’s lives with relish rather than remorse. And yet, from the oligarchs of Silicon Valley to the sycophants of Fox News, our politics seems addicted to the idea that Trump has been persecuted, cheated, and dispossessed.

Homer’s Iliad tells the story of Achilles, whose damaged pride leaves him sulking in his tent and refusing to join the Greek siege of Troy. For all his self-pity, though, Achilles does not convince his fellow warriors to withdraw their armies from the fight. His resentments remain his own. Melville recognized that in the turbulent world of American democracy, aggrievement was a powerful political tool. Seconds before he throws his final harpoon, Ahab exclaims what we might regard as a recipe for the “irresistible dictatorship” he exerts over the crew: “Oh, now I feel my topmost greatness lies in my topmost grief.”

Let me be clear: Ahab is too elevated, expressive, and philosophically self-aware to be explained by the MAGA movement. And yet, amid all his heroic complexity, the seeds of American aggrievement appear throughout his quest. When he inspires the harpooners, humiliates Starbuck, or tricks his crew, he revels in his own autocratic powers. Think of Trump nursing his bruises as he denies protection to his critics, threatens journalists with lawsuits, and fires the government workers who once held him to account. And think of all those accomplices lining up behind him, shamelessly claiming that he has been victimized by a deep state hoax.

The recent bans on DEI remind us that the grievances that count for this administration—and for too many administrations before it—primarily concern Christian nationalists and conservative white men. Moving further into the second Trump presidency, we need to interrogate the power the nation gives to their perceived injuries.

Ahab dies when he is strangled by the harpoon line attached to Moby Dick. In the aftermath, the whale sinks his ship. Every crewmember dies but one. I trust that Trump will come to a more peaceful, gilded end, but what happens to the rest of us? From Canada and Panama to Gaza, Greenland, and Ukraine (the list grows daily), the world seems stuck on an American ship bent on avenging the president’s wounded psyche.

A wreck seems inevitable. Surviving that wreck does not.

Featured image by Matthew Gonzalez on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 23, 2025

Fashion lingo

I am not a particularly fashionable dresser. My typical attire is jeans or khakis, a shirt with buttons or a sweater, and black running shoes (because black can go with everything). I’ve been described as non-descript. Therefore, it would make sense that I’ve only recently been exposed to some of the commentary on television’s Project Runway (and its numerous spin-offs).

For those of you unfamiliar with the series, think of it as The Great British Baking Show for fashion designers. Designers compete to meet various design challenges, and after each challenge, one designer is eliminated by the judges until a winner remains. The show has its formulaic catchphrases like host Heidi Klum’s signature line, “As you know, in fashion one day you’re in, and the next day you are out.” Each show, the judges greet the contestants as if they were meeting for the first time. And fashion design scholar Tim Gunn provides the contestants with sobering mentorship and brings a touch of professorial erudition with words like “mitigating,” “circuitous,” “placating,” and “consternation.”

For me, Project Runway was an introduction to a whole new professional jargon, one which I had previously had only a hazy awareness of. Clothes are “garments” and the finished projects on the models, with hair, shoes, and makeup, are “looks.” “Pants” show up as singular “pant.” Rather than fixing or tailoring clothes that aren’t working, the designers “edit” their garments.

The jargon extends to the challenges given to designers. These are sometimes straightforward enough, mandating a “red-carpet look,” “streetwear,” or a “cocktail dress.” Some are a bit more subjective, calling for something “sophisticated” or an “avant-garde design.” I didn’t know what that would entail, and often the designers didn’t seem to know either. Other challenges expanded my vocabulary: an “editorial look” is one that will look good in a fashion magazine (or on the web, presumably); “fashion-forward” is something has the potential of being trendy—what I would call “leading edge.” I’m still hazy about what a “couture gown” is.

The commentary on the looks by the judges are an education in the value system of fashionistas. Good designs are “impeccable and effortless,” “sophisticated, sharp, and architectural” or simply a “show-stopper.” Weaker designs get snark: a bad design might be “too matchy matchy,” “costumey,” “cliché,” “tacky,” or “kitsch.” A design’s construction could make it look “cheap” or “expensive.” Too many components might be “over the top,” “a mishmash,” or simply a “hot mess.” Other designs were “frumpy,” “overly commercial,” or “sad and boring.” Some were mocked as “matronly” or as “old lady” designs, which garnered some deserved pushback from more mature viewers. Over the course of the show, the vocabulary seems to have evolved to be less harsh, though that may just be my impression.

Looking over the show’s transcripts, I find myself hoping some enterprising scholar will construct a concordance of the Project Runway lexicon: the good, the bad, the metaphors, and the catchphrases.

As for me, I haven’t changed the way I dress much. But I’m thinking about it.

Featured image by Rudy Issa via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 21, 2025

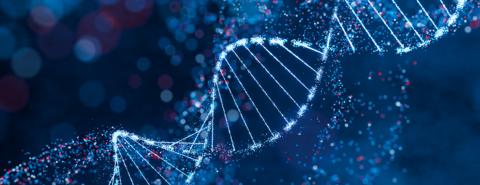

Searching DNA databases: cold hits and hot-button issues

Searching DNA databases: cold hits and hot-button issues

Many criminal investigations, including “cold cases,” do not have a suspect but do have DNA evidence. In these cases, a genetic profile can be obtained from the forensic specimens at the crime scene and electronically compared to profiles listed in criminal DNA databases. If the genetic profile of a forensic specimen matches the profile of someone in the database, depending on other kinds of evidence, that individual may become the prime suspect in what was heretofore a suspect-less crime.

Searching DNA databases to identify potential suspects has become a critical part of criminal investigations ever since the FBI reported its first “cold hit” in July 1999, linking six sexual assault cases in Washington, D.C., with three sexual assault cases in Jacksonville, Florida. The match of the genetic profiles from the evidence samples with an individual in the national criminal database ultimately led to the identification and conviction of Leon Dundas.

How the statistical significance of a match obtained with a database search is presented to the jury should, in my view, be straightforward but, given the adversarial nature of our criminal justice system, remains contentious. One view is that if the profiles of the evidence and a suspect who had been identified by the database search match, then the estimated population frequency of that particular genetic profile (equivalent to the Random Match Probability in a non-database search case) is still the relevant statistic to be presented to the jury. The Random Match Probability (RMP) is an estimate of the probability that a randomly chosen individual in a given population would also match the evidence profile. The RMP is estimated as the population frequency of the specific genetic profile, which is calculated by multiplying the probabilities of a match at each individual genetic marker (the “Product Rule”).

An alternative view, often invoked by the defense, is that the size of the database should be multiplied by the RMP. For example, if the RMP is 1/100 million and the database that was searched is 1 million, this perspective argues that the number 1/100 is the one that should be presented to the jury. This calculation, however, represents the probability of getting a “hit” (match) with the database and not the probability of a coincidental match between the evidence and suspect (1/100 million), the more relevant metric for interpreting the probative significance of a DNA match. Although these arguments may seem arcane, the estimates that result from these different statistical metrics could be the difference between conviction and acquittal.

There are many different kinds of DNA databases. Ethnically defined population databases are used to calculate genotype frequencies and, thus, to estimate RMPs but are not useful for searching. The first DNA searches were of databases of convicted felons. In some jurisdictions, databases of arrestees have also been established and searched. These searches have recently been expanded to include “partial matches,” potentially implicating relatives of the individuals in the database. This strategy, known as “familial searching,” has been very effective but contentious, with discussions typically focused on the “trade-offs” between civil liberties and law enforcement. In some jurisdictions, the “trade-off” has been between two different controversial criminal database programs. In Maryland, for example, an arrestee database (albeit one specifying arraignment) was allowed but familial searching was outlawed. Familial searching has been critiqued as turning relatives of people in the database into “suspects.” A more accurate description is that these partial matches revealed by familial searching identify “persons of interest” and that they provide potential leads for investigation.

Recently, searching for partial matches in the investigation of suspect-less crimes has expanded from criminal databases to genealogy databases, as applied in the Golden State Killer case in 2018. These databases consist of genetic profiles from people seeking information about their ancestry or trying to find relatives. Genetic genealogy involves constructing a large family tree going back several generations based on the individuals identified in the database search and on genealogical records. Identifying several different individuals in the database whose profile shares a region of DNA with the evidence profile allows a family tree to be constructed. The shorter the shared region between two individuals or between the evidence and someone in the database, the more distant the relationship. This is because genetic recombination, the shuffling of DNA regions that occurs in each generation, reduces the length of shared DNA segments over time. So, in the construction of a family tree, the length of the shared region indicates how far back in time you have to go to locate the common ancestor. Tracing the descendants in this family tree who were in the area when the crime was committed identifies a set of potential suspects.

The DNA technologies used in investigative genetic genealogy (IGG) are different from those typically used in analyzing the evidence samples or the criminal database samples, which are based on around 25 short tandem repeat markers (STRs). The genotyping technology used to generate profiles in genealogy databases is based on analyzing thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). With the recent implementation of Next Generation Sequencing technology to sequence the whole genome, even more informative searching for shared DNA regions can be accomplished. (Next Generation Sequencing of the whole genome is so powerful that it can now distinguish identical (monozygotic) twins!)

Investigative genetic genealogy (IGG) has completely upended the trade-offs and guidelines proposed for familial searching as well as many of the arguments. Many of the rationales justifying familial searching of criminal databases, such as the recidivism rate, and the presumed relinquishing by convicts of certain rights do not apply to genealogical databases. Also, the concerns about racial disparities in criminal databases don’t apply to these non-criminal databases either. In general, it’s very hard to draw lines in the sand when the sands are shifting so rapidly and the technology is evolving so quickly. And it is particularly difficult when dramatic successes in identifying the perpetrators of truly heinous unsolved crimes are lauded in the media, making celebrities of the forensic scientists who carried out the complex genealogical analyses that finally led to the arrest of the Golden State Killer and, shortly thereafter, to many others.

It’s still possible and desirable to set some guidelines for IGG, a complex and expensive procedure. It should be restricted to serious crimes. The profiles in the database should be restricted to those individuals who have consented to have their personal genomic data searched for law enforcement purposes. With the appropriate guidelines, the promise of DNA database searching to solve suspect-less crimes can truly transform our criminal justice system.

Featured image by TanyaJoy via iStock.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers