Oxford University Press's Blog, page 7

April 2, 2025

From meaning to moaning

Few people realize how troublesome the word mean is. We have mean as in meaning (“what do you mean?”); mean “ignoble, base” (as in such a mean fellow), and mean, as in the meantime and meanwhile. The last of those three mentioned has a Romance root, related to median and medium, and need not bother us. But the first two seem to be related, though it is not clear how. We may argue that they are. Yet we should remember that as a famous linguist said a century or so ago, a connection can be found between any two concepts, even between an inkwell and freedom of will. He was right. Semantic bridges are easy to reconstruct and equally easy to demolish.

An inkwell and freedom of will.

An inkwell and freedom of will. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, A Venetian Lawyer at His Desk. CC0 via the National Gallery of Art.

From the phonetic point of view, the verb mean and the adjective mean go back to identical forms. As just stated, it is hard to decide whether we are dealing with the same word or with two homonyms. I will join the majority of today’s etymologists and try to explain why the sought-for connection may and perhaps does exist. The situation in English is the same as elsewhere in Germanic: Dutch, German, and Scandinavian. For instance, in German, we find a similarly incongruous combination: meinen “to mean,” gemein (ge– is a prefix) “shared, common,” and “base, perfidious.” Even the German noun Meineid “perjury” (that is, “a false oath”; Eid “oath”) turns up. If we accept the hypothesis that “common,” “base, abject,” and “to mean, signify” are connected, we should try to find some explanation for this union in the customs of old communities and then move from some concrete sense to the most abstract one. “To mean, signify” is, of course, an abstract concept.

As usual, we should look for the cognates (related forms) of the verb mean in other Indo-European languages. They turn up in Slavic and Baltic, where the sought-for verbs mean “to change, exchange, barter.” (Take note!) For instance, we find the Russian verb meniat (stress on the second syllable; the vowel was once long) “to (ex)change,” but the gloss for a closely related form in Sanskrit is “to barter” and (!) “deception.” No surprise: trade is impossible without occasional fraud.

Digging for buried treasure.

Digging for buried treasure. Photograph by Portable Antiquities. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

I would like to add a detail not mentioned in dictionaries. The famous French scholar Claude Lévi-Strauss based his model of old societies on the idea of exchange. In the remote past (in medieval Europe, until approximately the fifteenth century), money did not exist. People did not buy or sell things: they exchanged them. Hence the culture of reciprocal gift giving and the curse laid on a buried treasure (a motif known from the mythology and folklore of all Eurasia). This is the point: treasure should move from hand to hand, rather than lying intact. Consequently, at one time, exchange was more than a detail of societal life: it determined life’s entire structure. Today, it often remains unclear how far historians should go in ascribing the events of the past to the system of exchange. Lévi-Strauss tended to make too much of it, but no one will probably doubt that trade (exchange, barter) presupposed both honest dealers and swindlers.

The most ancient Germanic form of the adjective mean was main-, as in Gothic ga-main-s “common” and (!) “unclean.” Was the implication “pawed over”? (Gothic, a Germanic language, is known to us from a fourth-century translation of the New Testament from Greek.) The sense “unclean” also comes to the fore in the Gothic verb –mainjan “to defile.” All kinds of unexpected references in the words that interest us did not bother Old Germanic speakers. Nor do they bother us. We say: “what do you mean?” and “such a mean person”—and experience no discomfort. This is the same thing with all homonyms: unless a pun is intended, the context makes everything clear.

Of some interest is also Latin mūnus “duty, public office,” familiar to us from commune and also related to the root of English mean. As explained long ago, the semantic development of the Latin word is based on the institution of hospitality, because a public official had the responsibility, in exchange for his honored position, to give games and public spectacles. Whenever we look, we find the root of mean with positive connotations (as in “duty”) and their opposite, often submerged in generalities (“to transform; exchange”) or appearing in words of negative semantics (“to falsify”; so again, in Gothic). “Change” is a broad concept: its reference may be neutral, but it need not be. We have witnessed a striking development from “change, exchange” to “declare; have an opinion,” and finally, to “intend” and “signify.”

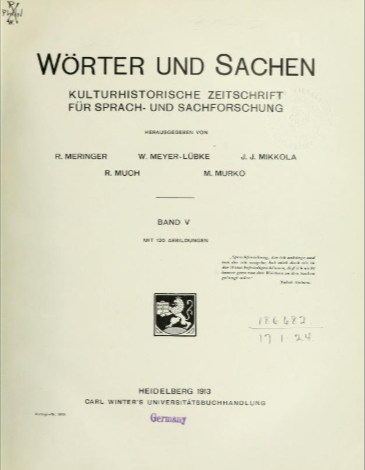

This essay has two messages. First, we observed a close connection between language history and the history of society. Words name things, and no one doubts that the connection exists, and that is why historical linguists study material culture. Last week, I referred to the old periodical Wörter und Sachen (“Words and Things”). Obviously, one cannot discover the etymology of the word plow, without knowing what plow means and what one looks like. Yet time and again, we run into the most ridiculous etymologies of fish names by the people who have never seen the fish in question.

Second, language develops according to its own capricious laws. Any action may be beneficial or detrimental, and the result of the sematic development of words cannot be predicted. “Trade” and “exchange” did not have to produce so many offshoots, but they turned up, and we do our best to account for them. In German, one of the offshoots of meinen “to mean” probably gave birth to the old word for “love.” Of course, why not? If “exchange” can produce “perfidy” and “fraud,” why cannot it produce “love”? Medieval German literature is famous (among other things) for its love poetry, known as Minnesang. German meinen has survived with the sense “to mean,” but at one time it was also a synonym of “to love.” We began our journey with a word for “exchange.” Isn’t love (Minne) an exchange of feelings between the one who loves and the one loved?

The most bizarre possible cognate of mean is English moan, which at one time even existed in the form mean. From a phonetic point of view, the match is perfect. It is the senses that again look incompatible. Yet by this time, it must have become clear that given freedom of will, a semantic bridge can always be constructed between almost any two points. If “exchange” can beget “love,” why not “suffering and grief”? We don’t moan when we are happy. Opinions on the etymology of moan are divided, and I have touched on it, mainly to emphasize how intricate and interesting the study of historical semantics is. Our colleges have all but abolished courses like Old English and Old Norse. No one loves us, specialists in such areas, except the public. Why then doesn’t the public fight for the restitution of historical linguistics?

The meaning of moaning.

The meaning of moaning. Image by Michal Jarmoluk from Pixabay.

It would be interesting to hear what our readers think about such things. Perhaps between the two Wednesdays, we will have an exchange of comments. Exchange, let it be remembered, is the root of societal life, be it the Stock Exchange, suffering, or love.

Featured image: Orr, John William, Engraver. Indian princess presenting a necklace of pearls to de Soto / J.W. Orr, N.Y. [Published] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. No known restrictions.

March 30, 2025

Slow down your writing

Sentences that are clear in our heads may be less clear when they come out of our mouths. When we talk, we get feedback from our audience or conversational partners. We observe facial expressions and body language. People may ask for clarification when something is not clear or they may correct us when we misspeak. Understanding is never perfect, but it’s doable in many face-to-face instances. On the page or the screen, it’s a different story.

I did a double-take when a fiftyish friend posted that she was marrying her “16-year-old boyfriend.” I figured out from the photo that it was her long-time boyfriend, not a minor, and I did a quick mental adjustment. Her attempt at specificity created a misunderstanding, but I just offered my congratulations without editorial commentary.

An announcement of a new hire at my university read, “She was hired to fill a position that was left vacant when her successor left the university at the end of July.” Something seemed wrong. It was only on rereading the announcement that I realized that “successor” should have been “predecessor.”

I was trying to schedule a meeting and one invitee sent his regrets. The time wouldn’t work, he explained. He already had plans to have coffee “with a friend and former colleague.” I assumed it was just the two of them, but I wasn’t sure.

On a discussion board in the early days of the COVID pandemic, someone posted a question about cleaning protocols, phrasing it this way: “Should we use students to clean the classrooms?” I almost posted a reply that, “No, we should use alcohol wipes,” but everyone was too nervous for jokes, so I bit my tongue.

Posts and emails are typically ephemeral, but we also fumble when we write for posterity. If we are lucky, beta readers or editors will gently point out confusing phrases. Here are a couple of examples of potential confusion from The Copy Editor’s Handbook. I like to think that they are real manuscript examples that got corrected.

This novel is a haunting tale of deception, sexual domination, and betrayal by one of South America’s most important writers.

The Century Building has been reincarnated after years of disuse as a beautiful bookstore.

The by– and as-phrases can be connected in more than one way to other parts of the sentence. For a writer not attempting humor, this sort of ambiguity is dangerous. Many readers will find such sentences clumsy even if they are not confusing.

And, recently, I wrote this sentence, citing a book I found interesting:

In Not Exactly: In Praise of Vagueness, the computer scientist Kees van Deemter shows how many of the concepts that we think are quite precise, scientific, and “crisp” (as he calls them) are actually rather vague.

Rereading it aloud, I stumbled over the phrase “how many.” Was I referring to a number? I changed “how” to “that.”

If you write something confusing once, your reader may be momentarily distracted. If you do it a lot, they will lose confidence in your writing. For me, the lesson of such examples as these is to take a break after you draft something. Put it aside for a few minutes or a few days (or months), read it aloud as a stranger would, and revise anything that seems confusing, clumsy, or potentially ambiguous.

Take your time.

Featured image by Brett Jordan via Unsplash.

March 26, 2025

A dictionary dance around Hag

As usual, I’ll begin with a comment on the letters I have received. I never wrote that too few queries about words of unknown origin were coming my way: I complained that a stream of letters addressed to Oxford Etymologist had in principle become a trickle. Nor was this blog meant exclusively for words of unknown origin (of which there are thousands). It would be foolhardy to expect that I might be able to solve even some of the riddles. While looking for the themes of my essays, I only try to find interesting words of disputed origin. Whenever possible, I volunteer my opinion. Another letter indicated quite correctly that some dictionaries call the origin of witch uncertain, rather than unknown. Dictionaries have a rather impressive list of such euphemisms, but the situation is clear. About some words NOTHING is known (a lot of slang belongs here). More often some reasonable hypotheses exist and compete. This is when the ghost of “uncertain” is raised, but “uncertain” is not much more promising to the public than “unknown,” though from the scholarly point of view, a mirage of an oasis holds out greater promise than a desert. It is rather obvious that the ancient root of witch is either wit– or wik-, but we have no way of making the right choice, and we are not sure which women were millennia ago called witches. Hence “origin uncertain.”

Not your usual haggaday.

Not your usual haggaday.Image by Omar González from Pixabay.

And now back to hag and its environs. It is entertaining to see what words surround hag on a dictionary page. The most exotic of them is the dialectal (northern) noun haggaday “a latch to a door or a gate.” The original OED cited it but offered no etymology, Walter W. Skeat (1895) compared haggaday and work-aday “by day.” He explained the device as “a slight mode of fastening by day,” because “in the night one would bolt the door,” and suggested (rather warily for him) that hagg– was related to hook by ablaut (as in shake ~ shook). But one expects hag– to refer to something tangible, regardless of a possible vowel alternation. The OED online derives the word from the phrase have good day (sic). Latches do come in all kinds.

Next we find haggard. No one doubts that the word is of French origin. The earliest reference is to the look of an untamed hawk. The French word was also haggard. Most of us know only haggard “gaunt, emaciated.” The derivation of the French adjective from Germanic is rather certain (though often questioned), but the alleged Germanic source is hard to trace to its root. Any connections with hedges or hags? German hager “gaunt, thin,” rhyming with its synonym mager, is also opaque. “Of obscure etymology,” as dictionaries put it (alas).

Haggard men training haggards.

Haggard men training haggards. Illustration from De arte venandi cum avibus. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Haggle gives us a short relief. It certainly contains a so-called frequentative suffix, a suffix that points to repetitive actions, as in mumble, tickle, scribble, and their likes. Haggle once meant “to mangle with cuts (now the sense is rather “to cut clumsily”), and today it more often refers to persistent wrangling in bargaining. If –le in haggle is a suffix, what is hag? It is an unmistakable Scandinavian relative of hew “to cut,” familiar to us from hedge.

Unexpectedly, haggis turned out to be one of the hardest Middle English words, as regards the etymology. The earliest citation goes back to the year 1400, but William Rothwell, a great expert in Anglo-French, assures us that already by the middle of the thirteenth century, “the English were eating haggis, crackling and suet.” Haggis has been derived from hog (this is one of Samuel Johnson’s improbable suggestions, but Johnson was not an etymologist and borrowed most of his ideas from Stephen Skinner’s 1671 dictionary). Yet Johnson also suggested hack as the etymon, and later researchers compared haggis and hag “cut, chop.” In 1896, Skeat derived haggis from French haut goût, literally, “high taste.” In the final edition of his dictionary, he returned to the verb hag.

A detailed investigation of the intractable word appeared in 1959. Its author was Charles H. Livingston (1884-1966), a noted Romance philologist. What follows has been derived from his publication, though I dispensed with quotes around my statements. Several different varieties of the dish named haggis existed. The present-day northern English and Scottish haggis represents only one of them. The cookery of the Middle English period and its language were very strongly influenced by French, but the French word hachis “hash,” as the original OED noted, was not known (that is, not recorded in texts) so early. Obviously, what does not exist cannot influence anything. Several good dictionaries follow Skeat and keep referring to the verb hag. But Livingston noted that he had not seen a single example of hag in any Middle English recipes of the 14th and 15th centuries. Recipes describe the process of preparing a dish, and a phrase like hag (= chop) the meat would have been natural in this context.

Give her a haggis.

Give her a haggis. Photo by Tess Watson. CC-BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Livingston cited Ernest Weekley (“Apparently, by some strange metaphor from French agasse, agace ‘magpie’”) and disapproved of this vague reference. Though Weekley could not explain the connection, the OED online treats his idea with interest. (Do I remember correctly that in one of Beatrix Potter’s tales it is said that “a magpie is some kind of pie?”) Haggis has always been a dish of the commoners, and for that reason, the word did not turn up in the recipes meant for aristocratic guests, even if the English were indeed “consuming haggis” in the thirteenth century.

Livingston referred to the Old French verb haguier “to cut” as the root of haggis. He traced it to Middle Dutch hacken “to hack, cut up into pieces.” The verb is “amply attested” in the modern dialects of Normandy. An initial aspirate h is still (!) preserved there in words of Germanic origin. (This, I may add, is not an uncommon phenomenon: people will retain foreign sounds in their speech, to emphasize the words’ non-native origin.) The suffix is in haggis is also French. Thus, the name of the Scotch “native dish” turned out to be a culinary term of Norman or Anglo-Norman ancestry. This is a good explanation.

As far as I can judge, the OED online almost agrees with Livingston. But it mentions the possibility of another option (the derivation from English) and mentions the striking similarity between the names designating pies and magpies. Few things in etymology are carved in stone. Yet it appears that the origin of haggis is not “unknown.”

Yes Powers, wha mak mankind your care,And dish them out their bill o’ fare,

Auld Scotland wants nae skinking ware

Tha jaups in luggies;

But, if ye wish her gratefu’ prayer,

Gie her a haggis!

So Robert Burns.

(Skinking ware “thin stuff”; jaup “splash”; luggie “a small wooden dish with a handle.”)

On this joyful note, we’ll bid farewell to hags, haggards, hedges, and haggis.

Featured image: Cropped photo of Robert Burns statue by filippo_jean. CC-By-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 25, 2025

Ten ways to see the Elton story [playlist]

Ten ways to see the Elton story [playlist]

Sir Elton John is a living superlative, unequaled in music history in terms of global sales, awards, and career longevity. His catalogue is therefore vast, comprising some five hundred songs recorded over almost six decades. So why choose just these ten? Although the list overlaps with any greatest hits package or essentials playlist, it represents neither my claim for the best ten nor my personal ten favorites. Instead, I chose each track to kick off one of the ten chapters of On Elton John; each song prompts a story about Elton, each one is a window that offers a particular way of seeing him and his career.

1. I’m Still Standing (1983)

At 177 bpm, “I’m Still Standing” has the fastest tempo of any Elton single. An infectious global hit, it helped Too Low for Zero become John’s biggest album since his mid-1970s imperial phase. Elton called it confident and swaggering, and it landed as a bold comeback statement—even more so in his post-rehab 1990s. By the time of 2019’s Rocketman biopic, the song could be deployed as an exaltation of survival. But there is a twist. The title and lyrics are not about Elton at all. They were written by his lyricist, Bernie Taupin, and they refer to Bernie’s recovery from the end of a love affair. It was really Bernie who was “pickin’ up the pieces of my life,” who was “still standing.”

2. Someone Saved My Life Tonight (1975)

Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy’s sole single, “Someone Saved My Life” was a long and melancholy hit. It narrates the 1967 incident when Taupin rescued John from an ill-considered engagement to the woman with whom he had chastely cohabited for six months. Suicidally miserable, John’s life was literally saved. Or was it? The suicide attempt was, as John later admitted, unconvincing. And in the song, it is Long John Baldry, not Taupin, who intervened to save his old friend. Baldry, secretly gay by necessity, spotted that John needed saving not from marrying the wrong woman, but from marrying any woman—a fact as obvious now as it was hidden then.

3. Rocket Man (1972)

“Rocket Man,” John’s first global smash, boosted his career into the stratosphere of stardom. By the mid-70s, he was the planet’s biggest-selling recording artist—on top of the world, not “lonely out in space.” As a song and as a branding device, “Rocket Man” has had a long shelf life, its title used in everything from hits compilations to his 2019 biopic, from John’s record label and its film and TV offshoot, to his fan club and a funding initiative with the Elton John AIDS Foundation. Its bleak lyrics have been buried by positive associations; John even performed it live at the 1998 launch of the space shuttle Discovery. In contrast to David Bowie, whose Starman metaphor evokes an otherworldly spaceman, Elton is an earthly superstar.

4. Philadelphia Freedom (1975)

Billie Jean King is one of the few living people for whom John and Taupin have written a song. “Philadelphia Freedom” was created when King was the coach and leading player of a mixed-gender tennis team called the Philadelphia Freedoms. John gave the song an upbeat pop-disco vibe, imagining it as an anthem for his friend’s team. But Taupin was stumped. As he’d yet to meet King, knew nothing about tennis, and was unfamiliar with Philadelphia, he delivered ambiguous lyrics that lent themselves to various causes. In the US, the song caught a rising tide of patriotism in the build-up to the Bicentennial. In Philly, it served as a civic anthem. And, as both King and John went from being closeted to out, the song steadily grew into an anthem of gay pride.

5. Electricity (2005)

As Elton’s sixty-third and latest solo Top 40 hit in the UK, “Electricity” saw him enter his second decade as a highly successful composer of songs for musicals, which started with 1994’s The Lion King. Part of the score for Billy Elliot: The Musical—a film-based stage musical for which John wrote all the music (to lyrics by Lee Hall)—the song represents John’s evolution through genres to a natural destination for him. Echoing his origins as a composer-for-hire of piano melodies, “Electricity” also reflects his love and mastery of the genre that is one of his true homes: musical theatre pop.

6. Border Song (1970)

“Border Song” was the first John single to chart anywhere (#29 in the Netherlands, #34 in Canada) and his first to chart in the US (a week at #92). But it was also covered by Aretha Franklin. She made the song her own, embracing its gospel/R&B potential, adding to its title the phrase that begins the song— “Holy Moses.” Franklin’s recording was bigger than John’s, peaking at US #37, getting further attention when it was included as the closing track on her Grammy-winning 1972 hit album, Young, Gifted and Black. Franklin’s recording also drew attention to the final lines and its deeply resonant sentiment: “There’s a man over there / what’s his color, I don’t care / he’s my brother, let us live in peace.”

7. Bennie and the Jets (1973)

What an iconic opening chord! Elton’s fingers are on the keys for just a second before he pauses, that fleeting sound instantly recognizable. Concert crowds roar, taking collective delight in the recognition of a single, uniquely odd set of notes. Their noise fills the brief silence before the band comes in, four beats later, with Elton now playing the intended chord, the “right” one. For that initial chord was never intended for the final version of “Bennie and the Jets.” It was a mistake made as John was finding the right notes in the studio, the tape already rolling. The producer and engineer retained it as a production cue to “fake-live” the whole song. Elton approved, keeping the perfect mistake as his own opening cue for half a century through to the final concerts of his Farewell Yellow Brick Road tour.

8. Candle in the Wind (1973; 1987; 1997)

“Candle in the Wind” has enjoyed a long life: three dates, three versions, three hits. It was originally a threnody—an elegy—to Marilyn Monroe. The E major melody that John composed for Taupin’s lyrics perfectly matched the topic of tragic celebrity, sentimental but just shy of saccharine. As a 1974 single, it reached #11 in the UK but was unreleased in the US. Yet its haunting and gently anthemic melody made it a fan favorite, and in 1987 it was chosen to promote John’s Live in Australia with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, hitting UK #5 and US #6. Its 1997 iteration would be its biggest, with lyrics rewritten by Taupin in honor of Princess Diana, her life cut short like Monroe’s at 36. Never performed again by Elton after Diana’s funeral, the studio version quickly became the best-selling single of all time worldwide.

9. Cold Heart (2021)

“Cold Heart” helped Elton break yet more records. A Top Ten hit in more than 40 countries, it made him the first solo artist to reach the UK Top 10 in six consecutive decades, and the oldest artist (aged 74) to hit #1 on the Australian singles chart. And it gave him the longest span (50 years and 10 months) of appearances in the US Top 40. All of which matters not simply because it is more data to add to Elton’s superlativeness. It matters because it matters to John himself, the consummate chart-watcher, the ultimate collector—of everything from vinyl records to chart records, art to artists whom he can collaborate with or mentor (like Dua Lipa, his partner here in “Cold Heart”).

10. This Train Don’t Stop There Anymore (2001)

“This Train Don’t Stop There Anymore” is all about endings. A languid ballad built on Elton’s piano and vocals, the Songs from the West Coast closer was a single whose video featured Justin Timberlake as a young Elton— amusingly and poignantly invoking the theme of lost love and ageing. John leans into Taupin’s bitter-heartbreak lyrics, giving them his classic melodic piano treatment. Was this a perfect postscript to their lives and careers since the two first met in late-60s London—so full of promise and possibility, ready to be “riding on the storyline, furnace burning overtime”? It might have been, but John and Taupin kept writing together. John has repeatedly run out of steam, but he always gets going again. Musically and personally, Reg just keeps on striking back.

Featured image by Raph_PH. Cropped. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 23, 2025

Towards dynamic accountability

Towards dynamic accountability

Accountability is a fundamental component of governance, whether the governed entity is a country, a company, or indeed any other corporate entity, including charities, cooperatives, the NHS, or universities.

What is meant by governance? Most definitions of governance, particularly corporate governance, focus on what governance does (direct and control). An alternative definition considers what governance really is:

“Corporate governance describes the way that trust is achieved, power exercised, and accountability shown, in corporate entities, for the benefit of members, other stakeholders, and society.”

Consequently, accountability is a fundamental part of governance. Yet, accountability remains the least discussed aspect of the subject.

The corporate governance matrix

The well-known corporate governance matrix suggests that the process involves strategy formulation, policy-making, monitoring/supervising management, and providing accountability.

Matrix of corporate governance.

Matrix of corporate governance.Created by Kevin Hinton, used with permission.

The right-hand side of the matrix (strategy formulation and policy-making) is essentially forward-looking, covering the overall responsibility for corporate performance, whereas the left-hand demands (monitoring/supervision and accountability) are concerned with the present or past and reflect responsibility for corporate conformance and compliance with law and regulations.

On passive accountability

Many directors think of accountability as the last step in the governance process, reporting the result of recent corporate performance. The literature on accountability has focused predominantly on financial reporting, independently audited in line with the relevant accounting principles or standards. Recent calls for reporting non-financial information have added a further dimension, including, for example, reports on strategy, sustainability, and ESG (Environment, Society, and Governance).

Such reporting suggests a passive approach to accountability, which provides information in line with regulations. Passive accountability typically takes credit for good results but blames poor results on external circumstances, such as market conditions, economic developments, or geo-political issues.

Consider some examples of directors’ reports in such companies:

“Revenues this year increased by a satisfactory 8.3%”—ignoring the fact that a large part of that increase was due to price increases reflecting inflation and that, in fact, the company had lost market share to competitors.“This year the company has faced shortages of imported components and supply chain difficulties, which have adversely affected results”—taking no responsibility for the board policies which relied on imported components or strategies that approved the supply chains. “Shareholder value, reflected in our share price, has increased substantially this year, justifying higher dividends and directors’ remuneration”—ignoring the comparable rise in the stock market overall, and failing to recognise that dividends and directors’ bonuses depend more on cash flow than share price.Board reports showing good results under passive accountability too readily become congratulatory public relations exercises, rather than serious explanations or, worse, opportunities for self-promotion by the chief executive or board chair. However, if the results are less satisfactory, passive accountability blames unavoidable external factors, outside the board’s control.

Prior to each of their collapse, the boards of Northern Rock Bank, Enron, and Carillion produced congratulatory annual reports:

Northern Rock took credit for its significant growth, outpacing competitors, without recognising the increased risk associated with junk-bond rated financing.Enron took pride in its growth, which was based not only on supplying energy, but by creating a market for energy futures, without realising that, in the process, their strategic risk profile had changed from a low-risk energy producer to a high-risk financial institution.Carillion gave shareholders a stream of high dividends, based on profit growth, but did not draw attention to the funding of those dividends, which was based on increasing financial leverage (debt/equity ratio), relying on interest-bearing loans, which led to corporate collapse when interest rates rose.In other words, passive accountability tends to provide the minimum data required by reporting regulations, does not accept responsibility for poor results, and sees accountability as the final step in the corporate governance process.

On dynamic accountability

By contrast, dynamic accountability recognises that passive accountability, routine reporting, and compliance with regulatory demands is not enough. Dynamic accountability believes that reporting performance in terms of financial profit or loss, income and expenditure, or even Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), is insufficient: a complete picture needs to show not only what the results were, but how and why they occurred.

Overall transparency needs to provide information on the context in which the results were achieved. Only then can readers see the full picture. That might include, for example, comparing the entity’s performance with industrial sector norms, describing market conditions, even comparing competitors’ performance.

Accepting responsibility for performance follows in dynamic accountability. The governing bodies of all corporate entities should not only report their organisation’s performance, but accept responsibility for it—whether good or bad, above or below expectations—explaining why those results have occurred. Then, in dynamic accountability, boards describe how they intend to build on the reported results as the basis for future strategic developments, policies, projects, and plans.

It is apparent that the governance matrix (Figure 1) has an underlying dynamic—strategy formulation leads to policy-making, which underpins management plans, budgets, and decisions, which produce the outcomes monitored and supervised by the board, leading to accountability, which, in dynamic accountability feeds into future strategy formulation and policy-making.

In other words, dynamic accountability is concerned with transparency, making visible the entire picture. Moreover, dynamic accountability accepts responsibility for all results—good or bad. It also recognises the need to build reported outcomes into future strategies, policies, and projects.

The significance of culture in accountability

Much of the literature on accountability assumes Western accounting rules. Most countries following these Western practices are democracies, with judicial system and law courts independent of the state. Increasingly, however, economic activity, wealth creation, and associated governance practices are found in countries with autocratic or oligarchic systems of governance. In many of these countries, the law courts are not independent of the state, but respond to state demands, “in the interests of the people.”

Consequently, corporate entities operating in these states need to recognise political influences in their governance processes. Two examples from China illustrate such situations:

The Initial Public Offering (IPO) flotation of Ant Financial Services on the Shanghai and Hong Kong Stock Exchanges would have been the world’s largest IPO. But it was withdrawn by the Shanghai Exchange, at the last moment, following state intervention.Ant was originally the financial services arm of the vast Alibaba Group, which provides retailing/communication platforms, similar to, but larger, than Amazon. The board of Alibaba was forced to change its organisation structure and unusual governance processes following government intervention.China is a one-party state and companies operating there need to be sensitive to the political component of corporate governance. Similarly, companies in some countries in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East need to be aware of political and other cultural influences in their governance processes, including accountability.

AI support for dynamic accountability

We have seen that dynamic accountability can provide higher transparency, requires boards to take responsibility for results, and feeds these results into future strategies. Each of these processes can be enhanced with artificial intelligence (AI) tools. For example, Workiva combines, on one platform, financial with non-financial records to support regulatory requirements, ESG reporting, internal audit, and risk management routines. NICE Actimize can flag compliance with both financial and non-financial reporting needs. Diligent Boards is a suite of AI tools that can support board strategic thinking through data-driven insights that identify relevant competitive, economic, environmental, or socio-political issues.

AI can monitor news sources, social media, and internal systems for early warning of stress, which could result in financial or reputational loss. AI can also assess mass data to suggest money-laundering, bribery, insider dealing, and conflicts of interest. Nevertheless, when using AI, boards should ensure that their AI systems are compatible with their corporate strategies, ethics, and accountability goals.

The way ahead for dynamic accountability

In dynamic accountability, performance reports are not seen as the final step in the governance process, but as an ongoing phase in the corporate governance cycle. Responsibility is accepted by the board for all results, good or bad, explaining how and why these results have occurred. Boards with dynamic accountability also explain how they intend to build current results into future strategies, policies, and projects. Introducing dynamic accounting will need a change of attitude in some boardrooms.

Featured image by PublicDomainPictures from Pixabay.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 21, 2025

Oxford Intersections: research from all angles [quiz]

Oxford Intersections: research from all angles [quiz]

We’re excited to announce the launch of Oxford Intersections, a new interdisciplinary research tool from Oxford University Press. Containing original research from diverse disciplines, this tool provides a comprehensive approach to problem-solving, fostering innovation and collaboration.

Oxford Intersections aims to address some of the world’s most pressing challenges, such as AI in society, racism in different contexts, social media’s impact on culture, environmental change, and gender justice. By exploring these complex issues from multiple perspectives, Oxford Intersections offers innovative solutions and new insights.

Discover more about intersections, interdisciplinarity, and the advantages of interdisciplinary research with our short quiz.

You can find out more about Oxford Intersections by visiting the website.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 20, 2025

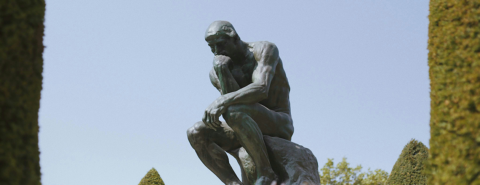

A thinker and her thought

Thinker statues form a fascinating, but little explored cultural theme. While we may be most familiar with Rodin’s thinker, thinker statues, both male and female, appear in many very diverse cultures. They include appearances in Roman art, the pensive bodhisattvas of Korea and China, the pensive Christ statues of Eastern Europe and Italy, the thinker statues of Kazakhstan and Africa, as well as the female thinkers of the pre-Columbian Tumaco-La Tolita culture.

Korean bodhisattva.

Korean bodhisattva. Used with permission from the National Museum of Korea.

What is common among all the thinker statues despite their different cultural and religious background is that they incorporate a mental attitude, thinking. At the same time the thinker statues are themselves objects. Now these two notions, attitudes and objects, of course, compose the title of my book (which also includes the Korean bodhisattva on its cover). This title targets the two facets of the topic of the book, which addresses what sorts of objects are involved in the various mental attitudes—thinking, doubting, imagining, inferring, questioning, hypothesizing—as well as their manifestations in speech, asserting, suggesting, asking, answering, and demanding.

The objects involved crucially play the role of content bearers (representing situations) or as things that can be satisfied or violated (a command can be satisfied or violated, a question can be satisfied by an answer). The standard philosophical view about mental attitudes and their linguistic manifestations (speech acts) is that they are all relations to the same sort of object, a proposition. A proposition is just the sort of thing that is taken to make up the content of a that-clause, with which verbs describing mental attitudes or speech acts generally go along: The thinker thought that life is a mystery; the speaker said that life is a mystery.

Kazakhstan thinker.

Kazakhstan thinker. Author’s personal photo.

Philosophers, starting with Bolzano and Frege in the nineteenth century, took the syntactic form of attitude reports and speech act reports to wear their logical form on their sleeves: attitude verbs like “think” and speech verbs like “say” take two arguments: an agent, and the thing that makes up the content of a that-clause, a proposition. Propositions, the putative objects of attitudes and contents of attitudes and speech acts, thus are considered the content bearers involved in attitudes and speech acts. However, as objects, propositions need to be abstract and mind-independent

since they are meanings of sentences and can be shared by different agents, and that raises lots of problems—how can an abstract object be grasped by the mind and why should an abstract object be able to be true or false or represent anything in the first place? Moreover, mental attitudes and speech acts just do not seem to be relations to mere content objects: we do not think or say propositions or any objects whatsoever.

This book takes a different approach. The objects involved in mental attitudes like thinking, imagining, and questioning are the things we refer to as thoughts, imaginations, and questions. Thinking thus means “engaging in a thought,” imagining means “engaging in an imagination,” etc. Since we make explicit reference to such attitudinal objects in natural language, we can let ourselves be guided by our linguistically manifest intuitions about such objects. All those objects have truth or satisfaction conditions: a belief can be true, a hypothesis correct, a command can be complied with or violated.

A female thinker statue from the Tumaco-La Tolita culture.

A female thinker statue from the Tumaco-La Tolita culture.Luz Miriam Toro Collection. Used with permission.

Different attitudinal objects, as one can quickly see, go along with different predicates of satisfaction and these can tell us a lot about what truth and representation consist in. For example, the selection of particular predicates of satisfaction indicates that truth is a norm some attitudinal objects come with (beliefs, assertions, hypotheses) and that actions are the sorts of things that other attitudinal objects may require for their satisfaction and may even qualify as “correct” (commands, suggestions). Lots of philosophically exciting views and options can be read off the linguistic manifestation of the ontology of attitudinal objects, as well as their more abstract kin, modal objects of the sort of obligations, permissions, needs, and options.

The thinker statue is an object and her thinking is an attitude that in turn involves an object, the bearer of truth. On the view developed in this book, that object is a thought, an object extremely well-reflected in natural language.

Featured image by Avery Evans via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 19, 2025

The end of the witch hunt

My sincere thanks to all those who commented on the recent posts. I have never heard about the rule about one day referring only to the future. Naturally, I immediately Googled for it and found that the rule does not exist. I also checked its equivalent in several other languages. The result was the same. Perhaps one day is indeed more often used about future events, but this is as far as we should go. Pedants are fond of enforcing such suspicious rules. Many years ago, an editor (not for this blog!) insisted that though should be used in the middle of the sentence, while for an opener only although is allowed. I refused to be bullied. Usage is in general a delicate matter, and before following someone’s advice, one should always check the source of the information. Even such things that are certainly wrong refuse to go away, stay, and (whether we like it or not) become the norm. The most instructive and entertaining book written about such matters is still Fowler’s Modern English Usage (especially the earliest editions).

With the ghost of one day laid to rest, we may pick up where we left off last Wednesday and return to the origin of the word witch. The Old English for “witch” was wicce. This form referred to females (Old English had three genders, like Latin and Modern German). The masculine counterpart of wicce was wicca, that is, “wizard,” and it turned up in texts more than a century before wicce. We will briefly return to wizards below.

This is the famous journal, mentioned in the text.

This is the famous journal, mentioned in the text. Image from the Internet Archive.

Two problems complicate the search for the etymology of wicce. In the previous post, I wrote that we don’t know (or at least, don’t know exactly) what women and men, endowed with supernatural powers, were called wicce ~ wicca, and it is hard (almost impossible!) to discover the origin of a word if the object it names remains unknown. At one time, an excellent journal with the German title Wörter und Sachen (“Words and Things”) existed. It was devoted to exactly such problems and read like a series of detective stories. The contributors were historical linguists, specialists in material culture, ethnographers, and more.

The second problem is the oldest extant form of witch, that is, wicce. In it, the letters cc designate a real long consonant (the technical term for such a sound is geminate: think of the constellation Gemini), as in Italian ecco “here” or in English book cover. Geminates were extremely rare (almost nonexistent) in Old English, and in wicce, cc may have been the product of assimilation (some consonant plus k; by way of analogy: when this shoe becomes thish shoe, as it always does, we witness assimilation). Thus, wicce might go back to witce or some other form like it. However, even this statement is not a hundred percent safe, because a few Old English geminates arose under emphasis, and a word for “wizard; witch” (whatever the original reference) aroused all kinds of associations and was, very likely, “emotional.” We can see that both the ancient meaning of wicce and its original form remain hidden. It is therefore no wonder that we still don’t know the exact answer to our riddle.

In search of a solution, language historians have wandered for ages in the thicket of similar Germanic and non-Germanic words. They compared wicce with Gothic weihs “holy” (the main Gothic language monument is an incomplete fourth-century text of the New Testament), Old English wiglian “to divine; to practice witchcraft” (though the vowel in its root might be long), and Latin victima “sacrifice.” Several verbs, related to English wiggle, have also been pressed into service, because völva, a mysterious prophetess, known from Old Scandinavian myths (see the post for last week!), was supposed to roll in the process of divination. But too little is known about such practices to justify a reliable etymology, and we cannot be sure that the Old English witch was supposed “to see into the future,” let alone “wiggle.”

An etymologist in search of the origin of the word witch after five centuries of looking for it.

An etymologist in search of the origin of the word witch after five centuries of looking for it. Photo by Ron Lach.

The oldest attempt to break the spell over the word witch involved the roots of wit (as in to wit and witty) “to know” and of wizard, the latter being always and correctly understood as “wise man.” But it is better to stay away from wizard, because this word surfaced only in the fifteenth century. Old English wīt(e)ga “a wise man” appears as the source of witch in many good dictionaries. Yet this etymology cannot overcome several phonetic difficulties, which I will not discuss here, since the effort to understand them will not pay off. I can only say that both the first edition of Skeat’s etymological dictionary and The Century Dictionary shared this etymology, and it was copied by multiple sources. (Beware of dictionaries and popular books that suggest etymologies without explaining how they were discovered.)

On the whole, two “schools” emerged as regards the origin of witch. One tried to connect the English word with the root wit-, while the other favored wik-. At the end of his career, Skeat favored the second option and referred to verbs, meaning “to tun away, divert.” The volume of the OED with the word witch appeared long after the death of James A. H. Murray and Henry Bradley, the two greatest editors of the original OED, who among other things, excelled in etymology, and witch was left almost without any hypothesis about its origin. Today’s OED online has a somewhat different format from the first edition. The problem is that most people look on the verdicts in the OED as examples of absolute truth. As I understand, today’s team wisely refuses to play God. When the problem defies a definitive answer, the OED now gives a brief summary of the state of the art in notes and refrains from taking sides.

Surprisingly, today, we don’t seem to know much more about the etymology of witch than our predecessors did four, three, and two centuries ago. The latest serious attempt to break the spell over this word goes back to 1979, but the proposal by the American linguist Martin Huld also left some important questions unanswered. Against this bleak background, I may risk offering my hypothesis, certain of being dismissed like my numerous “forerunners.” Whatever may happen, I’ll remain in good company. In my opinion, witch goes back to the form wit–ja– “divinator” or perhaps “healer.” The root wit meant “to know.” If this is correct, the negative connotations inherent in Modern English witch may have emerged later. The verb witan “to know” often referred to people’s familiarity with arcane things. Characteristically, Old Icelandic vitt meant only “witchcraft, charms.”

In good company (as noted). The Merry Family, by Jan Steen, 1668.

In good company (as noted). The Merry Family, by Jan Steen, 1668. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Two more words can be mentioned in a postscript. One of them, discussed above, is wizard, now understood to be a male counterpart of witch. But this late coinage is made up of the root of wisdom and a suffix, as in coward, drunkard, and the like. Wiseacre “smarty,” a late sixteenth-century word, is believed to be a borrowing from Middle Dutch. The ironic connotations that have always been present in this word make the idea of borrowing from Dutch credible. My Walpurgis night is over. Next week, I will discuss a few words that share the page with hag and go over to more mundane things.

Featured image: Illustration from the first edition of The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 16, 2025

We the Men

Amidst the flurry of headlines about the Trump administration’s first weeks in power, who will notice that the federal government’s largest agency no longer celebrates Black History Month or Women’s History Month? The Department of Defense’s January 31 guidance declaring “Identity Months Dead at DoD” may have been lost in the news cycle.

But Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth took the time to make this change because commemorations are important. They shape how Americans understand the past, think about the present, and envision the future. That is why the Trump administration has already launched its plans for marking America’s semiquincentennial in 2026. President Donald Trump himself chairs the task force.

Although the Trump administration is unlikely to acknowledge it, America’s commemorative landscape remains starkly uneven. Almost 250 years after the Declaration of Independence proclaimed “that all men are created equal,” only three women made a recent list of the 50 most frequently commemorated people in America’s public monuments. In comparison, the list includes 44 white men, many of them slaveholders. Congress has never designated a legal public holiday—the kind that closes federal offices—to celebrate an important woman in American history.

Reformers have been fighting for generations to expand America’s commemorations. Decades after the creation of Black History Month and Women’s History Month, efforts to include all Americans in the nation’s commemorations have had limited success—largely because these efforts continue to face vehement opposition.

Trump joined that opposition long before his current presidential term, speaking out against placing Harriet Tubman’s image on the $20 bill.

Only two women have ever appeared on America’s paper currency. Martha Washington graced the front of a $1 silver certificate that the United States first issued in 1886. Pocahontas knelt for baptism on the back of a $20 bill first issued in 1863.

Many Americans have noticed women’s absence. After years of activism from women in and out of Congress, the Obama administration announced a plan in 2016 to redesign the $20 bill, with Tubman replacing President Andrew Jackson on the front.

At the time, Trump was pursuing the Republican nomination for President. He immediately denounced the decision to place Tubman on the twenty as “pure political correctness,” as if Tubman did not merit such prominent recognition. In contrast, Trump insisted that Jackson had “a great history.”

To put Trump’s claims in context: Jackson was a slaveholder who removed Native American tribes from their lands. Tubman was an abolitionist and suffragist who freed herself and hundreds of others from bondage before becoming a Union scout, spy, and nurse during the Civil War. Each historical figure foregrounds different aspects of America’s past. To my mind, Tubman’s record is far worthier of celebration.

Trump, however, declared in 2016 that “it would be more appropriate” to have Tubman’s image on “another denomination,” suggesting “maybe we do the two dollar bill or we do another bill.” If you have rarely seen a $2 bill, there is a reason for that. The two is the least-used bill.

After Trump became President in 2017, his Treasury Department delayed introduction of the new $20 bill and spent years repeatedly refusing to indicate whether the redesigned twenty would feature Tubman.

One of Trump’s former White House staffers published a tell-all memoir in 2018. She recounted Trump’s reaction when she gave him a memo in 2017 about placing Tubman on the twenty. Trump reportedly looked at a photograph of Tubman and asked: “You want to put that face on the twenty-dollar bill?” The question implied that Tubman did not look like someone who belonged in that place of honor, or did not look like someone Trump found physically attractive, or both.

After Trump’s defeat in 2020, the Biden administration reported that it was committed to placing Tubman’s portrait on the front of the twenty. However, Trump’s victory in the 2024 presidential election has made that commemoration uncertain again.

America’s Constitution purports to speak for “We the People.” But too many of our commemorations include only We the Men. That usually means white men. Amidst the many other struggles that will mark the Trump presidency, it is well worth fighting to include all of us in the stories America tells about itself. The celebrations for the 250th anniversary of the United States are just one year away.

Featured image by Ben Mater via Unsplash .

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

March 13, 2025

At Elizabeth Peabody’s bookshop

At Elizabeth Peabody’s bookshop

Most histories situate the birth of feminism in the United States at the Seneca Falls Convention, held on 19-20 July 1848, in upstate New York. Yet as I researched and wrote Bright Circle: Five Extraordinary Women in the Age of Transcendentalism, I came to believe the movement had its roots almost a decade earlier and in a most unlikely place: the Boston bookshop owned and operated by Elizabeth Palmer Peabody.

That bookshop, which never had a proper name, was an extraordinary place. As soon as it opened in 1840, New England intellectuals began frequenting the ground-floor shop to browse through its choice selection of European books and journals. In the evenings, men and women gathered to discuss a wide range of topics, including abolition, metaphysics, poetry, or the latest scheme to settle a utopian community. Peabody’s bookstore was a stock exchange for ideas, a gathering place for the nascent transcendentalist movement. And it was the location of Margaret Fuller’s legendary Conversations.

Fuller, often referred to at the time as the best-read woman in the United States, possessed a ferocious mind and a gift for conversation. Her talk was mesmerizing, improvisatory, brilliant. She had the rare ability to sum up what everyone was thinking in pithy, memorable phrases. Although she would die at age 40 in a tragic shipwreck off the coast of Fire Island, she managed to cram a considerable amount of life into her brief, luminous existence. She wrote books and essays on a wide variety of subjects and was a member of the Transcendental Club. She wrote for a newspaper in New York, an occupation that eventually sent her to Italy, where she met and fell in love with a count named Giovanni Ossoli and gathered material for what was to have been her magnum opus, a history of the Italian Revolution in 1848.

Before all this, however, in the autumn of 1839, she came up with the plan for the Conversations. Keenly aware that women with intellectual interests had few outlets to discuss ideas, Fuller envisioned a group of some twenty-five women gathered each week to discuss Greek mythology, the arts and, most important of all, “to answer the great questions. What were we born to do? How shall we do it? which so few ever propose to themselves ‘till their best years are gone by.’” The Conversations began in November, and were initially held in an apartment, but they soon moved to Elizabeth Peabody’s new bookshop and included participants from as far away as Concord and New York.

It is difficult to recapture the substance of these talks. We know from the scattered testimony of its participants that many regarded the Conversations as life-changing. I took the title of my book from the comment of one woman whose identity remains unknown but whose appreciation for the gathering is obvious: “As I sat there, my heart overflowed with joy at the sight of the bright circle, . . . for I know not where to look for so much character, culture, and so much love of truth and beauty, in any other circle of women and girls.” That we know as much as we do about the Conversations can be attributed almost solely to Peabody, who diligently transcribed the talks for one season and then distributed them to friends who couldn’t attend. Those notes suggest that the women at her bookshop returned again and again to questions of female identity, to the unfair social arrangements that kept women from receiving the same education as men or of holding public positions, and to speculations about the way forward.

Ultimately, the Conversations yielded pathbreaking insights and writing. One of its members, Sophia Ripley, wrote an early feminist essay, “Woman,” which appeared in The Dial and argued, “In our present state of society woman possesses not; she is under possession. . . .Woman is educated with the tacit understanding, that she is only half a being, and an appendage.” But the most important byproduct of these remarkable exchanges was Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century, the first major work of feminist theory in America and a work still taught in American literature classes across the country. Fuller once again summed up and crystallized the ideas swirling around her, pushing them in new directions and formulating a powerful argument against unequal marriages and the restriction of women to the private sphere. The book concludes with a call for both sexes to engage in a program of mutual improvement and self-determination.

The Conversations lasted four years. By the time Fuller concluded them, she had already moved on to other commitments and concerns. Now less a transcendentalist than a cultural critic for a major newspaper, she turned her appraising eye to penal reform, the plight of immigrants, and the high art music of Beethoven, among many other topics. But by then, and from the unlikely platform of Elizabeth Peabody’s bookshop, she had already left an indelible mark on the history of American feminism.

Photo by Bozhin Karaivanov on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers