Oxford University Press's Blog, page 6

April 23, 2025

The salt of the earth and salt in a saltcellar

The salt of the earth and salt in a saltcellar

First of all, my thanks to those who commented on the previous posts. Don’t miss the note about the ancient Romans’ view of babies on the father’s knee and the suggestion that the idiom to pull one’s leg may be of nautical origin. If this suggestion is correct, to pull one’s leg will align itself with to pay through the nose. From what I have read, to pay through the nose is indeed a technical expression coined by sailors. As concerns the Greek origin of the verb moan, I found no confirmation of this idea in the books I consulted.

Now on to today’s topic, but first, an acknowledgment. Below, I’ll use the material of several publications, without referring to them. Such is my usual practice in this blog. When I write a scholarly paper, I supply it with a detailed bibliography, but for a popular exposition like the present one such details will probably only bore the readers. Anyway, I found the names for “salt” all over the world in a 2009 paper by Václav Blažek and some useful information in a 2010 paper by L. P. Dronova, in Peter Schrijver’s 1995 paper, and in Victor Hehn’s 1873 book Das Salz, to mention a few.

In Eurasia, all the forms look similar: sāle, sāl, sol’, and the like. The forms elsewhere usually have a root ranging in meaning from “good” to “sour.” Here is a short list of such “exotic” forms: bera, hmog, jot, kiho, melakh, mbulano, sipo, tabtu, tirdi, and úogo. However, surprises may occur even closer to home. Thus, Latvian (Latvian is of course an Indo-European language!) druskà “salt” means “something small, crumbly.” In dealing with the name of such a product, one never knows whether it goes back to some extremely ancient protoform or is a migratory word, that is, a term traveling from place to place with the object it designates. Of course, in their migration westwards, Indo-European tribes found great deposits of salt on the shores of the Aral and the Caspian Sea. Be that as it may, a common Indo-European name of salt probably existed and looked like s-l, with a vowel between them.

Vegetarian food needs salt.

Vegetarian food needs salt. Female kudu visiting a saltlick. Image by Prosthetic Head. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

One notices that the word meaning “salt” often resembles the word for “sea.” Thus, the Latin for “open sea” is salum. As studies of the British Iron Age show (to cite just one example), salt was produced on the coast. Seawater was probably let in in spring and allowed to sit until autumn, when a salt crust was formed. An important observation is in order here: the spread of salt is inseparable from the spread of agriculture, because salt is an indispensable condiment only in the food of those who depend on vegetable products. (See the image of deer salt licks!) By contrast, meat-eaters can do without salt. To give just one example: as late as the nineteenth century, some Bedouins did not use salt.

Germanic also contains some words that point to the connection between salt and sea water. In Old Scandinavian, we find hit eystra salt (literally, “the eastern salt”) for the Baltic Sea. Not improbably, English silt, which is a borrowing from Scandinavian, contains the same root. But English silt means only “sediment,” while in modern Norwegian and Danish dialects, similar words have wider currency, and the related verbs usually mean “to pickle.” German Sülze “pork jelly” belongs here too, although it’s not so much salt, the crystalline compound NaCl, that interests us in this context as its use in food preparation.

Let us return to the ties between salt and agriculture. In the Indo-European language family, the root sal– is widespread in the area in which also the root ar– “plow” is known. (The English adjective arable “fit for tillage” is a borrowing from Old French or directly from Latin, but whatever the source, it gives English speakers an idea of that root. Incidentally, Old English also had the verb arjan “to plow,” and to ear is still known in some dialects.) The point of this short excursus is obvious: plowing presupposes agriculture, and that is why in language, the plow and salt as a food product go together.

Two historical allies.

Two historical allies. Image 1: circa 1937, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Public domain via Flickr. Image 2: salt cellar. Jacques Seligmann, Paris, by purchase; Henry Walters, Baltimore, 1912, by purchase; Walters Art Museum, 1931, by bequest. CC0.

A striking detail in the history of the word salt is that its seemingly ubiquitous cognates (so in Greek, Latin, Slavic, Germanic, and Celtic) do not show up in the Indo-Iranian group. They are absent from Sanskrit. If such a word had existed, it would have shown up in Rigveda and Avesta. The perennial question that bothered medieval scholars and often bothers us is whether the absence of a word means the absence of the object it designates. This is not a good place for going into philosophical depths, but the fact remains that a cognate of salt is absent from a most important language group.

An old salt.

An old salt. Image: Old Salt. CC-BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The etymology of salt is perhaps known. Of interest are a few words whose phonetic shape resembles that of salt and which refer to the dirty-grey color. Such are English sallow, German Sal(weide) “willow” (Latin salix), and Russian solovei “nightingale” (stress on the last syllable; if so, then “a grey bird”). They have often been compared with salt. (There is no justice in the world: of all the memorable qualities of the nightingale only its color was singled out by the Slavic speakers of long ago!). Thus, salt “grey substance”? It also easy to notice that the root sal– sounds like the Latin word sōl “sun.” According to a bold and rather adventurous hypothesis, salt is related to sōl and meant “the sediment left after the water had evaporated.”

Whatever the distant origin of salt, an amazing twist in its history deserves our attention. Some close cognates of our word mean “sweet”! Here, Baltic languages (Lithuanian and Lettish) and Slavic provide the most striking evidence. In Russian, slad– means “sweet” and solod means “malt.” The root must have had a rather indeterminate sense, just “something adding good taste to the consumed food,” that is, “condiment.” Ambiguity in this sphere is common. Sweet is probably related to sap. Both salty and sweet must have meant (rather vaguely) “making the food more edible.” Sour goes back to the sense “wet” (but in Lithuanian, the related adjective changed its sense to “salty”!), and bitter is, most probably, from a historical point of view, “biting” (yet the metaphor underlying “bitter” is different in other languages). All our words designating taste are metaphors, whose origin we usually no longer remember. But even knowing the general principle, one cannot help admiring the infinite resourcefulness of language. Language is great, while etymology, we should admit, is sweet and sour, and most of what etymologists say should be taken with a grain of salt.

Featured image: Location of the Baltic Sea in the region. Image by Aplaice. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

April 22, 2025

Crafting the queer citational turn

Crafting the queer citational turn

It’s a crisp summer morning, and I’ve just made the half hour walk from Sommerville, Massachusetts, to Harvard University. The grounds are majestic, as you’d expect, but everything is fragmented by iron fence railings (gates all locked or staffed by security) and garish white tents that have been installed for graduation festivities. I show my ID and make my way into the Houghton Library reading room where I’ll continue my research on craftwork for a project on queer modernist materialities. As a fan of the show Dickinson, which aired on Apple TV+ for three seasons from 2019-2021, I’ve asked to see the scrapbook set designer Marina Parker made for the archive. I’m fascinated by contemporary adaptations of literary pasts, and Parker’s scrapbook suggests how craft itself might be fundamental to those queer reworkings.

As I carefully flip through the scrapbook’s pages, I’m struck by the care Parker has taken in assembling a material record of the show, which pays particular attention to Emily Dickinson’s queerness and the cultural and literary pasts of American activism. Wallpaper swatches are pasted in alongside sources of flooring inspiration, such as the checkered black and white floor she discovered while on a meditation retreat held in an old Massachusetts mansion. Correspondence with some of the oldest continually operating artisan design businesses (like lacemakers and carpet weavers) intwine with Parker’s record of her research rabbit holes. These imbricated textual and material records form a kind of citational archive—in recording her sources, Parker shows in very real terms how the work of a single set designer depends on a network of collaborators.

Page from Set Decorator Scrapbook.

Page from Set Decorator Scrapbook. Harvard University, Houghton Library MS Am 3372 Box 6 Folder 1. Author’s Image.

One particularly unique set of citations emerges in the various “shout outs” Parker records in the scrapbook. For example, on one page she writes about the task of curating the artworks in Dickinson’s brother and sister-in-law’s house, The Evergreens. She names the Assistant Set Decorator, acknowledges her specific contributions, and writes, “SHE DID A FANTASTIC JOB!”

Page from Set Decorator Scrapbook.

Page from Set Decorator Scrapbook. Harvard University, Houghton Library MS Am 3372 Box 6 Folder 1. Author’s Image.

In an email (my gratitude to curator Christine Jacobson for connecting us), I asked Parker to reflect on the place of these notably enthusiastic scrapbook citations. In her reply, she described her difficulty finding a place in the film industry earlier in her career and moving towards collaboration as a core principle:

The path to creative satisfaction seemed to be to seek as much creative control as possible. The reality though, is—the pace, breadth, & scope of film work, makes it unrealistic and impossible to truly work alone. And inspiration is often nurtured by exchange. In subsequent years I’ve slowly discovered / am discovering a community of people whose inspired ideas & work ethic I admire. Collaborating with talented, generous, delightful people has become one of my favorite parts of working in film; I now consider collaboration a real gift. I very much want to lift up, acknowledge, and appreciate the many hands and hearts behind the work.

This scrapbook, in addition to Parker’s ethical and artistic commitments to generous citation, align with larger trends in feminist and queer scholarship. In more particular terms, this approach to not just acknowledging—but actively celebrating—a collaborative process takes its cues from the history of craft. While writing Crafting Feminism from Literary Modernism to the Multimedia Present, I also aspired to represent the “many hands and hearts” that contributed both practically and intellectually to what is ultimately a single-author monograph.

Sara Ahmed has described her own citation practices (not citing any white men in Living a Feminist Life, for example) as a way of building new structures for belonging. She suggests that, “Citation is feminist memory,” a way to craft community when departure seems like a necessary path. The theorist becomes a craftsperson as “Citations can be feminist bricks: they are the materials through which, from which, we create our dwellings. My citation policy has affected the kind of house I have built.” Ahmed describes the intellectual work of feminist writing as deeply predicated on her own willingness to be vulnerable and to respond reciprocally in encounters with readers or audiences of various kinds. In that way, she changes the materials of her craft to capture this dynamic of exposure: “Perhaps citations are feminist straw: lighter materials that, when put together, still create a shelter but a shelter that leaves you more vulnerable.” The house of scholarship, therefore, seems made of bricks—and other times, straw strikes Ahmed as the more appropriate material.

The artisanal properties of citation emerge in Susan Howe’s work on archives as a kind of serendipitous encounter with craft. She describes the processes by which “Often by chance, via out-of-the-way-card catalogues, or through previous web surfing, a particular ‘deep’ text, or a simple object (bobbin, sampler, scrap of lace) reveals itself here at the surface of the visible, by mystic documentary telepathy.” To illustrate the dynamic interplay of this telepathy, Howe engages in rigorous citation across texts and archives, both public-facing and personal. In one section, Howe quotes Stein’s invocation to “Think in stitches,” prompting the reader to understand the queer encounter at play in the archive, mediated by craft: “In looking up from her embroidery she looks at me.” Instead of bricks or straw, textile knots become her source material for crafting a creative-critical text such as Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives. She writes:

Quotations are skeins or collected knots. “KNOT, (n., not…) The complication of threads made by knitting; a tie, union of cords by interweaving; as, a knot difficult to be untied.” Quotations are lines or passages taken at hazard from piled up cultural treasures. A quotation, cut, or closely teased out as if with a needle, can interrupt the continuous flow of a poem, a tapestry, a picture, an essay; or a piece of writing like this one. “STITCH, n. A single pass of a needle in sewing.”

Howe’s vision of the quotation-as-knot both interrupts the flow of an essay or poem while also holding it together—like a binding. (Here I must admit to checking the Index of my book for my own reference to Virginia Woolf’s “heaped up things” in The Years, which in a footnote I describe as “a temporal phenomenon and a record of trauma recall[ing] Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History […] in which ‘His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage.’ It reminds me of Howe’s “piled up cultural treasures”…This line of quotations, or knots, extends between disparate texts, connecting them—stitching these references in a row.)

Multimedia scholars such as Storm Greenwood are crafting the queer citational turn quite literally through the project of “Devotional Citation,” a praxis Greenwood started in 2017 at the “intersection of visual art and decolonial feminist scholarship.” “Devotional Citation” is predicated on a praise framework that is reciprocal and resists the “commodification of study.” Many of Greenwood’s Citations are circulated in a gift economy of stitched quotations that are given back to the author, their words transformed into a new textual artwork. As the recipient of a Devotional Citation that quotes Crafting Feminism, I am struck by the ways in which quotes are remade through contact with Greenwood’s craftwork. Not only are the pieces illuminated—as in, illustrated and decorated with gold metallic pigment—they are illuminating; this citational practice reveals new dimensions of writing on craft through the very stitched nature of each word.

Artwork by Storm Greenwood.

Artwork by Storm Greenwood. Author’s Image.

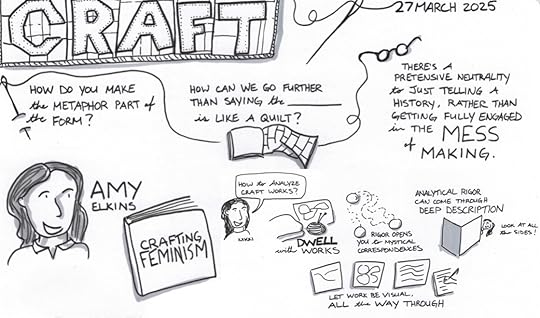

Scholars are increasingly thinking about the shape their work takes, with citation as a collaborative process that can be made visible or even ritualized—such as the authors of “Feminist Citational Praxis and Problems of Practice” who describe the process of co-authoring a dissertation and engaging in citation practices, or rituals, that “provide an opportunity to ‘flip the scrip’ on CisHeteroPatriarchy.” Or on the topic of “Collabowriting,” Suzanne Churchill and Adam McKible argue that, scholarship is “collaborative in nature: the term ‘monograph’ actually belies the exchange of ideas that occurred through print and over time to produces the work. Collaboration animates and personalizes the scholarly exchange.” Or, one final example: I was recently delighted to see that Danielle Taschereau Mamers had taken visual notes of my exchange with a group of graduate students at the University of Toronto (thank you to Claire Battershill for this joyful invitation). In these notes, Mamers cites me as the speaker but also interweaves her own perspective on the conversation and represents the students’ various questions and prompts, too. The topic of craft and scholarship is enlarged by the visual-verbal patchwork.

Visual Notes (selection) by Danielle Taschereau Mamers.

Visual Notes (selection) by Danielle Taschereau Mamers. Used with permission of Danielle Tascherearu Mamers (DTM Studio).

Writing a book is a process of encounter between voices and ideas throughout history—and our citational rituals form a thread, stitching the project together as a crafted object. As those conversations become more intentionally oriented towards variously inclusive methods, craft’s tactile, transhistoric metaphors and practices will form an important stitch in the future of scholarship.

April 20, 2025

Ten transformative Andraé Crouch tracks that shaped gospel music [playlist]

Ten transformative Andraé Crouch tracks that shaped gospel music [playlist]

At his passing in 2015, President Barack Obama celebrated Andraé Crouch as the “leading pioneer of contemporary gospel music.” The Guardian UK newspaper’s obituary called him the “foremost gospel singer of his generation.” Ten years after his death, Andraé Crouch’s songs are still found in more hymnals—Black and white—than any African American composer, save Thomas Dorsey (and Dorsey had a 30-year head start!).

While Crouch’s live performances galvanized audiences in venues ranging from Madison Square Garden and Carnegie Hall to Explo ’72, it is his compositions that are best remembered today. As Obama suggested, Crouch all but created contemporary gospel music. He’s also credited as the founder of the Praise & Worship music phenomenon. He was an innovative evangelist, a restless composer, musical experimenter, and a perfectionist whose gospel songs are still sung today around the world.

Choosing among Crouch’s many recordings from a 50-year career in music is an exercise in frustration but we have identified 10 songs that we believe can truthfully be said to be “transformative”:

1. “The Blood (Will Never Lose Its Power)”While watching the Rev. James Cleveland pour barbecue sauce on a brisket at a cookout, Crouch, still just in his teens, was inspired to write his first gospel song, “The Blood (Will Never Lose Its Power).” Frustrated, Crouch initially tossed the hastily scribbled lyrics, but twin sister Sandra Crouch fished the sheet from the trash and Billy Preston quickly fleshed-out Andréa’s melody. Crouch recorded two versions of “The Blood,” this one sung by Billy Thedford (later Bili Redd) from the album Take the Message Everywhere (1969).

2. “I’ve Got Confidence”The most pop-oriented of all of Crouch’s hits, this happy, upbeat number caught the ear of Elvis Presley, who recorded it in 1972 on his final and best-reviewed religious album, He Touched Me. The song was quickly recorded by dozens of other artists. “I’ve Got Confidence” appears on Andraé and the Disciples’ Keep on Singin’ (1970).

3. “My Tribute (to God be the Glory)”One of Crouch’s most symphonic—and beloved—compositions, “My Tribute” owes a spiritual debt to the beloved hymn writer Fanny Crosby’s “To God be the Glory.” The song’s soaring chorus comes to a dramatic crescendo and has become a part of the evangelical church’s core repertoire since its first appearance on Keep on Singin’ but it is Alfie Silas Durio’s heart-stoppingly stratospheric recording on the Finally album (1982) that remains the definitive version.

4. “Through It All”In his short biography by the same name from 1974, Crouch tells the heartbreaking story of his first and greatest love, Tramaine Davis, who left the Disciples and married famed gospel singer Walter Hawkins. The loss threw Andraé into a deep depression that only lifted when the words and music to this triumphant ballad came to him, though he couldn’t bring himself to record it until the release of the Soulfully album in early 1972.

5. “Satisfied”One of the defining moments of the Jesus Music movement and the beginnings of contemporary Christian music is Andraé Crouch and the Disciples’ electrifying performance of “Satisfied” before 80,000 screaming fans at Explo ’72 in Dallas—still one of the largest religious music festivals ever. The Disciples turned what was a pop song on Soulfully into a Holiness piano-driven gospel vamp/stomp. The Explo ’72 version is available on YouTube via a professionally-produced video that includes footage of the massive festival.

6. “Bless His Holy Name”Perhaps the first recording of a song in the style of what would come to be called Praise & Worship music, “Bless His Holy Name” is the highlight of Crouch’s first “solo” album, Just Andrae (late 1972). Andraé would return to his format throughout his career, with gentle, reverent hymns like “Hallelujah,” “It Won’t Be Long,” and “Praises.”

7. “Jesus is the Answer”Though recorded before Just Andrae, “Live” in Carnegie Hall was not released until a year later, in 1973. The album, which served as his breakthrough in both the Black and white Christian markets, showcases Andrae’s reliance on the Holy Spirit to “lead” the services. “Jesus is the Answer” was still only partially completed when he introduced it on the Carnegie Hall stage. Paul Simon found the happy, bouncy tune so appealing that he recorded it on Live Rhymin’ later that year.

8. “Take Me Back”By the release of the Take Me Back album in 1975, “A-list” studio musicians were clamoring to record Crouch’s innovative, instantly memorable songs. The song showcases Billy Preston’s inspired work on the Hammond B3 organ and the brilliant vocals of Danniebelle Hall. Whatever musical adventures Crouch might explore elsewhere, he always included at least one triumphant, memorable gospel song like “Take Me Back.”

9. “Soon and Very Soon”Though released on the It’s Another Day album (late 1976), “Soon and Very Soon” is based on a timeless Church of God in Christ chant—or perhaps an even older spiritual. It is compelling, haunting and irresistible, especially when the senior members of his father’s Christ Memorial Radio Choir, led by 80-something Mother Dora Brackins, join the chorus on the close.

10. “Just Like He Said He Would”Live in London (1978), with its iconic cover of a spaceship piano hovering over the United Kingdom, was Andrae’s last great release. Over the course of the two LPs, Crouch preaches, testifies, re-visits, and re-imagines beloved favorites, unpredictably introduces old hymns, and improvises several new songs on the spot. “Just Like He Said He Would,” originally released on Take Me Back, brilliantly synthesizes jazz, funk, R&B, rock, and gospel into a seamless whole—and thrills the stunned English audience.

Featured image by Matt Botsford via Unsplash.

April 16, 2025

On a limb

One can teach an advanced course on etymology, while climbing up the leg, ant-wise. On foot we reach the territory of Indo-European, but it is not every day that an English word finds itself in such respectable company. Greek pod– and Latin ped– are of course related to foot (the variation p ~ f and d ~ t goes back to the First Consonant Shift, a familiar motif in this blog; compare pater ~ father and duo ~ two). The Latin root turns up in English pedal, pedestrian, and so forth. We walk pad-pad-pad, and so did people millennia ago. The most ancient word for “foot” was obviously sound-imitative. Probably the same holds for path, despite some hurdles, not worthy of discussion in the present context.

By contrast, leg is a loan from Scandinavian. What a surprise! For about a thousand years, English speakers have been out on a (borrowed) limb and are none the worse for it! So it goes… To exacerbate matters, we discover that the etymology of Old Norse leggr is unclear and that its original meaning must have been simply “limb,” because it turns up in such transparent compounds as armleggr and handleggr. Arm-limb and hand-limb look like so-called tautological compounds of the pathway type (both constituents mean almost or exactly the same). Leggr could also mean “bone hollow”!

A human leg in all its glory.

A human leg in all its glory. Image from Cunningham’s Text-book of anatomy. Public domain via Flickr.

The once popular comparison of Old Norse leggr with Latin lacerta “lizard” should be dismissed, because the origin of the Latin animal name is unknown and can therefore shed no light on another obscure word. Even if Latin lacertus “arm” has the same root as lacerta, the etymology of those two words does not become clearer. Leggr is related to Old Norse lær “hip” (the Swedish cognate is lår, and English once had lire, with the same sense), but this is where the story ends, though some Greek nouns have been cited as possibly related. Leg, we should admit, is a word of obscure origin. Nor does the history of German Bein “leg” shed even the weakest light on leggr, because it too is a word of unclear etymology.

We should move on, but we immediately stumble at ankle, another loan from Scandinavian! This is an especially unexpected case, because Old English had the word anclēow. Chaucer still used it in a slightly modernized form, but then the Scandinavian very similar competitor took over. Anclēow, a compound, was related to such words as Latin angulus “angle,” which, considering the shape of the ankle, makes perfect sense.

We seem to have reached the shin but have nothing to boast of. Old English had two closely related words for “shin”: scīa and scina, both “less than fully transparent,” which means “of unknown” or “of unclear origin.” The now accepted derivation of the word from the root for “cut” (as in German schneiden) is, in my opinion, doubtful, and I am glad that the OED online does not mention it. Shin resembles German Schenkel “thigh,” another rather obscure word. The Germanic cognates of shin mean “splint, a thin piece.” Skeat, hesitatingly, admitted that shin might be related to skin (skin, with its characteristic initial sk– is still another borrowing from Scandinavian: the native English word for “skin” is hide). The connection is dubious but not improbable. Once again, consider Russian golen for “shin,” that is, a bare place (goly “naked”). The association between the shin and a place covered only by skin is not improbable. However, all this is clever guesswork and speculation.

Pad, pad, pad.

Pad, pad, pad. Image: Walk Alone… by Thomas Leuthard. CC-BY-2.0, via Flickr.

Onward, only onward! With knee we are again on solid Indo-European soil: Latin genu, Greek gónu, and others. However, the soil is swampy. Several words, once they are reduced to protoforms, sound alike (almost indistinguishable). Such are knee, chin, and kin. Kin is particularly intriguing. For clarity we may compare such English words as genuflection “bending the knee” and generation. Both are of Romance origin. Genu– in genuflection obviously refers to knees. The etymology of generation needs no comment. Is there a connection between generation and knee? Though in some languages this connection is obvious, speakers do not notice it. For instance, the Russian for “knee” is koleno (stress on the second syllable), while the word generation (as in the first generation of…) is po-kolen-ie.

The shortest history of genealogy.

The shortest history of genealogy. Photo by Keira Burton via Pexels.

It has been suggested and more or less accepted in both linguistics and anthropology that the connection is not fortuitous. An old ritual has been cited, according to which when a baby is born, the father puts it on his knee and thus recognizes the newcomer as belonging to the kin. This ritual, which has been observed in several cultures, naturally, presupposes the patriarchy. The somewhat puzzling tie between generation and knee has also been recorded in a few languages not belonging to the Indo–European family.

We have finally reached the thigh and the hip. With thigh “the upper part of the leg” one is again on firm ground. The word has unmistakable Indo-European cognates and contrary to the well-known idiom, here, we do have a leg to stand on. The word’s root seems to mean “fat, thick.” Now on to the hip! But first, it might be of some use to give a few definitions, in order to avoid misunderstanding: thigh “part of the human leg between the knee and the hip”; hip “part on either side where the bone of a person’s leg is joined to the trunk.” For highbrows: perineum “the region between the scrotum and the anus in males, and between the posterior vulva junction and the anus in females.” In bilingual dictionaries, thigh and hip are sometimes confused. With so much light shed on the subject, I am pleased to add that the only English minimal pair illustrating the difference between th, voiceless, and th, voiced, is thigh versus thy.

Like thigh, hip is well-connected. Greek kúbos “hollow above the hips on cattle; cubical die” is probably the most transparent cognate of hip outside Germanic (h-p versus k-b is again due to the Consonant Shift). Of course, we do not know why some ancient sound group like kew– (the reconstructed root) suggested to people the idea of bending and thus of a hole or in general something round. We don’t even know whether such “roots” existed, but it appears that the words listed as cognate in our dictionaries are indeed related, unless the entire procedure is an aberration of vision, the result of looking at an incredibly remote object through the wrong end of the binoculars. Mission accomplished! Ant-wise, we have crawled all the way up the leg and ignored only the toes and sitting in one’s lap.Leg is a part of numerous idioms, most of which are transparent. Only pull one’s leg, fist recorded in texts in 1821, is enigmatic. Even about a hundred years later, many British speakers had never heard it, though both Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde used it in their plays. In the Victorian epoch, leg was avoided in polite conversation (the more reason, of course, for the phrase to be widely known!). It appears that the idiom enjoyed more popularity overseas (in India and in the US) than in Great Britian. It has also been suggested that its home is Scotland, but no evidence at my disposal supports this idea. Of course, such a vulgar idiom must have a well-hidden origin. Consider British English you are having me on!

April 14, 2025

What actually happened during the 1970s?

What actually happened during the 1970s?

Working-class politics is back in vogue in the West, but for whom does it speak? An AfD candidate in Germany won over 14% of the vote after claiming the SPD was ‘no longer a workers’ party in the classic sense’ and that his organisation was ‘taking on this role’. The US Vice President, JD Vance, emphasises he is a ‘a working-class boy, born far from the halls of power’ and promises to reshore industrial jobs. Marine Le Pen claims to lead the ‘party of French workers’ and Fratelli d’Italia wins a majority of manual workers after asking if ‘the Left is now no longer in the factories and amongst the workers, where can you find it?’ (its answer: a Pride parade). These political visions define themselves against an identity politics of the urbane, the educated, and the socially liberal. They seek to reverse the impacts of deindustrialisation, globalisation, and social liberalisation which began in the mid twentieth century and rapidly accelerated after the 1970s.

Histories of contemporary Europe tend to argue that the defeat of a certain kind of industrial politics associated with the Left was both inevitable, permanent, and an event long in the making. Viewed from the year 2000, the dividends of adaption to broadened social bases, reformulated programmes, and a post-class image seemed self-evident to many. Twenty-five years later, this consensus has been challenged. The British Labour Party’s chief strategist believes winning back working-class voters is the fundamental test of power. Others stress the polarisation of values between graduates, professionals, and ethnic minorities and pensioners, school leavers, and workers. Though many trace the origins of contemporary uncertainty to the 1970s, fewer have concretely analysed what actually happened in that decade.

West Europeans experienced that decade differently to its retrospective representation. The trade unions and social democratic and Communist parties grew and a diverse new generation entered the labour movement. Marginalised young, female, and immigrant workers led strikes to gain rights. White-collar workers unionised and sections of a previously hostile middle class appeared to be switching allegiances. Immigration, women’s entry into the workforce, widening educational access, increasing service employment, and minority movements were believed to have expanded the reach and magnetism of the Left. Many on the other side of politics thought that this trajectory would continue. Successful strikebreaking movements, new automation technologies, and organisational recasting helped to interrupt this momentum. A generation of workers felt bewildered, unable to understand their predicament, and bereft of the means to resist the shift to a new era. Only under specific circumstances at the end of the 1970s and early 1980s did the old Left’s expanded coalition fracture with enduring and sometimes traumatic results. The reliance on ideas of decline has contributed to the flattening of a complex history.

Asking different questions of the 1970s may require experimentation with methods, incorporation of neglected forms of evidence, and analysis of various cases within unitary frameworks. Archivally-driven accounts rooted in spaces of common deliberation and action can address the absence of a certain kind of working-class voice in existing narratives. Combining transnational and comparative approaches can provide insights on periods where the forces of change traverse states and delimited frameworks, institutions, and cultures channel their energies, manage their impact, and decide on priorities. Looking beyond that decade, it might be worth developing more granular accounts of the relations between technology and society, following the scholarship of David Edgerton and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, and establishing a deeper understanding of how machines are used at work. The conditions of possibility of a moment when the Right seeks to occupy the space where classical working-class politics once stood merits further study.

Feature image by André Cros. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

April 12, 2025

How to be a good lawyer in an AI world

How to be a good lawyer in an AI world

“AI is an amazing legal assistant that will cut out all the boring work and make you three times as efficient.”

“AI is a copyright thief that will take your work and reproduce it without attribution or remuneration.”

“AI produces great value for your clients.”

“AI gets things wrong and will make you a global laughing stock if you cite imaginary cases in your court pleadings.”

Sounds familiar? There is no shortage of opinions on generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI) and its uses in the legal space. If you are a lawyer, it is probably dominating your office meetings and working dinner conversations. Many firms are taking a cautious approach but, with legal technology providers pouring hundreds of millions of pounds into developing ever faster, more accurate tools, it feels only a matter of time before the use of Gen AI is an integral part of most lawyers’ working days. That has interesting, if uncertain, implications for how young lawyers learn their craft and the kind of roles available to legal professionals, as well as for the delivery of justice.

There is something else that merits attention in the AI debate: what is the value of human thinking about the law? Law doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It is shaped and applied in a social, political, and economic reality created by humans. It is a deeply human endeavour. How can the law evolve if algorithms use statistics to apply legislation and precedent to the facts and produce pleadings—or even decisions—based on the most probable outcome? What is the role of lawyers and judges if their work can be mined by a large language model (LLM), which can then create its own legal advice, pleadings, and judgments, as well as legal scholarship, for anyone who knows how to write the right prompts? What does it mean to be a good lawyer when AI can do your work in seconds—for free?

We are not quite in that world yet but it is not a far-fetched scenario. Numerous tests have shown that the differences between student- or AI-written essays can be imperceptible even to experienced lecturers. Some of the steps to be taken are deeply practical: establish the right guardrails to stop the sharing of protected information with LLMs that will ingest that information and reuse it; train lawyers and legal scholars on how to use AI responsibly and to always check the source material; and press tech companies to be transparent about how their LLMs are trained and users’ data and privacy are protected. Ensuring LLMs are free from bias is particularly important. No single lawyer can achieve this but, collectively, lawyers’ advocacy for responsible, safe AI will make a difference.

Perhaps even more important is this: among everything AI promises, let us not lose sight of the importance of human thinking and creativity to the law. Sometimes a completely new line of argument or a highly creative interpretation is required to adapt the law to changing circumstances or shifts in society. AI cannot, or perhaps should not, do this. The best thinking is often slow, maturing over time as a lawyer or judge mulls a case over. Or it emerges in conversations with others, sometimes in unexpected ways. It is often sparked by something you read. Legal publishing has a crucial role here: helping to disseminate the best legal analysis and commentary across the globe and create a permanent record of every book, article, and short form piece. Being a good lawyer in an AI world involves placing enduring value on the quality and originality of human thought and scholarship.

Featured image by Ground Picture and licensed via Shutterstock.

April 11, 2025

How did English literature become a university subject?

How did English literature become a university subject?

Even if you didn’t ‘read English’ at university yourself, you almost certainly know plenty of people who did, and more or less everyone has had to study English literature at school at some point or other. As a subject, ‘English’ (an adjective masquerading as a noun) has been central to educational arrangements in Britain for well over a century, seeming for much of that time to occupy a privileged place in the wider culture as well.

Yet literature may seem the most unlikely candidate for becoming a recognized academic discipline. For the most part, science and scholarship have operated with implicit canons of enquiry that have emphasized objectivity, verified knowledge, causal analysis, and impersonal, replicable forms of argument and presentation. But the reader’s encounter with works of imaginative literature does not easily lend itself to such treatment, involving instead subjectivity, degrees of responsiveness, evaluative judgement, and highly individual forms of imaginative re-creation.

As a result, there was initially scepticism about, even considerable resistance to, the idea that the study of vernacular literature might merit a place alongside the new disciplines being established in the expanding universities of the nineteenth century, and even when it had secured a foothold in the curriculum it continued to be derided in some quarters as ‘a soft option’. Surely the reading of enjoyable works of literature in one’s native language, so the objection went, was an activity to be pursued in one’s leisure hours? A university concerned itself with matters of exact scholarship and rigorous reasoning, as in the established disciplines of Classics and Mathematics: appreciation of the beauties of poetry had no claim to rank alongside these strenuous exercises, and, besides, it was clearly impossible to devise an objective way to examine achievement in such a personal, even emotional, activity.

So how did the improbable marriage of beauty and the footnote came to pass; or in other words, how did English, despite these and other objections, establish itself within British universities so successfully that it could sometimes be spoken of by the beginning of the 1960s as the ‘central’ subject in those institutions—even, in some hard-to-define way, as central to the culture at large? The answer to this question cannot take the form of a seamless narrative. We need, for example, to think about some of the larger enabling contextual conditions—the prior reverence for an established canon of English literature, the authority of Classics as a model and a rival, the formative role of history and philology as exemplars of serious scholarship. We also need to examine the relevant institutional developments between the late eighteenth and mid-twentieth centuries: how far was the Scottish tradition of teaching ‘rhetoric and belles-lettres’ a genuine precursor of ‘Eng Lit’; what were the early civic universities actually like; why were Oxford and, especially, Cambridge comparatively late in establishing courses in English; why was English disproportionately prominent in the institutions founded for the higher education of women; and how did these developments relate to what was going on in schools?

Shifting the focus, we need to think about the roles played by some of those who are regarded as among the ‘founding figures’ of the discipline—some who are well-known, such as Matthew Arnold and A.C. Bradley, but also some who are not, such as John Churton Collins, George Saintsbury, Walter Raleigh, and Arthur Quiller-Couch, as well as thinking about the status of the ‘professorial estate’ more generally, looking at its economic circumstances, its recruitments patterns, and so on. And what about the everyday forms of departments, journals, professional associations and so on? They can’t be left out of the story, can they?

Once we’d done all this, we’d be in a position to challenge the conventional accounts of ‘the rise of English’, showing, for example, that I.A. Richards’s supposedly transformative effect on the discipline was in reality more limited, and that the vogue for ‘criticism’ spread more slowly and more unevenly than has been assumed. In fact, we would eventually discover that most English departments at the beginning of the 1960s still had very traditional-looking syllabuses.

At present, ‘Eng Lit’ is widely seen as a discipline in crisis, with reductions in courses and even closures of whole departments being reported across the country. These problems are systemic and there is no one answer to them, but whatever view we take of the current position and future prospects of the study and teaching of English literature, the essential starting point has to be a more adequate account of the history of the enterprise, one that does not reductively depict it in either sinister or salvationist terms.

Feature image by Patrick Tomasso via Unsplash.

April 9, 2025

A grim shadow of a broad grin

While working on the post about mean and moan, I decided to write something about groan, but I did not realize how far this word would take me. Gr– is one of the best-known sound-imitative (onomatopoeic) complexes. Greedy animals in fairy tales and disgruntled shopkeepers in novels say gr-gr. They grunt and growl. Grinding and the monster Grendel (from the Old English poem Beowulf) are not “far behind.” All is grist that comes to this mill, even perhaps groin, let alone great. Yet when one looks up groan in an etymological dictionary, one learns with surprise that the answer will appear in the entry grin. We certainly don’t grin when we groan. People seem to have once had the “root” gr-n, which was like a bag into which any vowel might be put for the production of a rather unpredictable sense.

We find the same situation all over the Germanic-speaking world, and exploring the roots of groaning and grinning resolves itself into an almost endless list. This list is not uninteresting, because it probably shows how millennia ago people coined their “first words.” To be sure, we are not witnessing the production of primordial cries, but even a later process is instructive. Old Norse grína meant “to grimace, to distort one’s face in joy or disgust” (note that though by devious ways, grimace has the root grim!). The numerous cognates of grína mean “to snarl; growl, groan.”

And what about grunt? The same story. To be sure, pigs are famous for grunting, but each of us may sometimes give a grunt. Grunt is an old verb. German grunzen, Latin grunnire, and Greek grúzein mean the same. One sees such words in a dictionary and does not give them another thought. Yet this list should cause surprise. If everybody from Old England to Ancient Greece had practically the same sound-imitative verb, how can we account for this phenomenon? Granted, primitive noises make the same impression on people everywhere, but still: almost the same verb, not just gr-gr-gr! It has been a long time since I mentioned Wilhelm Oehl, a Swiss linguist, who once wrote a series of papers about what he called primitive word creation. I find his examples “thought-provoking” (in quotes, because this epithet has been trampled to death: every time I open my computer, someone offers me another thought-provoking story). Similar impulses produce similar reactions (and words) everywhere, but in this case, the uncanny similarity of the form comes as a surprise.

A particularly onomatopoeic domestic animal.

A particularly onomatopoeic domestic animal.Image by Dr. Roland Klemmderivative. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Can such words be borrowed? Is it possible that Latin borrowed the verb from Greek, and the “Germans” borrowed it from Latin? Yes, indeed. In the Romance-speaking world, we find the verbs grigner, grinar, and their likes meaning “to grunt, growl, snarl.” Not only Oehl but also the great German philologist Wilhelm Braune has been mentioned more than once in this blog. He was the author of the main textbooks of Gothic and Old High German and the coeditor of a deservedly famous journal. His given names were Wilhelm Theodor, and, amusingly, he published all his Germanic works under the name Wilhelm and a whole series of etymological papers about the Germanic etymology of Romance words under the name Theodor. Our gr– words belong here: from Germanic to Romance.

From Victor Hugo: A man with a famous grin.

From Victor Hugo: A man with a famous grin. Universal Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Braune (in this case, Theodor) reconstructed the initial meaning of gr-n words as “gnash one’s teeth, crack.” This protomeaning looks realistic. After all, crack begins with kr-, and in the situation that interests us not much difference can be found between gr– and kr-. Braune also offered a detailed essay on the origin of the word grimace, which traveled from Germanic to Romance and back to Germanic. My impression is that Braune’s contributions to etymology have not been noticed. In any case, I never see references to them. I discovered the entire series only in the process of compiling my database for a new etymological dictionary of English. It was clear that Romance periodicals would contain numerous works on Germanic words, but I did not expect to discover a veritable treasure house of etymological musings by someone who is remembered as one of the founders of Germanic comparative grammar. As regards today’s topic, Braune’s essay on grimace deserves special mention, but we have to go on.

It seems that gr is just a typical onomatopoeic sound complex. However, this complex suddenly begins to offer other possibilities. Gr-gr fills us with fear, and we are ready to add gruesome to our list. Gruesome is a northern word in English, but German grausam “cruel” and the impersonal verb grauen “to fill with horror” show that the word was also known in West Germanic. In its wanderings, it crossed the path of the color name gray/grey. Grimalkin means “cat” (-malkin goes back to a female personal name, originally from Mathilda, but later, typical of lower classes; hence Daniel Defoe’s novel Moll Flanders) and is understood as “grey Malkin,” but the sense “frightening, terrible” is behind it. Gray-Malkin is one of many names Shakespeare used for “Devil.” Though the most belligerent cats were also called grey in Old Norse myths, the adjective’s original sense was as in German grausam and English gruesome. This is the way of all things: you grin, and your grin inspires people with awe or fear.

When we grin, the mouth opens and a space is formed. Several words in Scandinavian owe their origin to this situation. One of them is “branch” (compare “a branch of knowledge,” that is, a separate area). Such are Swedish gren and its cognates. A branch separates itself from the trunk! This is how language works. A sound complex is produced, and its message is unmistakable. For instance, gr-gr (noise). Then more abstract senses begin to weave around it (fear, fright). Still later, people remember that to produce a grunt, the mouth should open (grins and grimaces appear), and the lips separate (branches join the crowd). For some reason, at some time, the sound complex goes abroad, and the same words begin to wander from Greece to Germany, and from the Germanic world to France and Italy. To add insult to injury, the word meets its twin (this happened with gray), and more confusion is the result. Grimalkins begin to jump all over the place. I doubt that AI will beat humans at this game. In my opinion, historical linguists, though largely unemployed, will always have something to do. On another note, my home team has just lost the home opener, and I cannot resist the temptation of quoting the title of the newspaper article about this disaster: “Home…Groan.” Most certainly, the editor of the sports section will not read this post.ave an exchange of comments. Exchange, let it be remembered, is the root of societal life, be it the Stock Exchange, suffering, or love.

A solitary branch: a symbol of separation.

A solitary branch: a symbol of separation. Photo by Yitzilitt. CC-BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Illustration of the Cheshire Cat, a character from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1916) by Arthur Rackham. Public domain via rawpixel.

April 8, 2025

Ultra-processed foods are making us old beyond our years

Ultra-processed foods are making us old beyond our years

In recent years, ultra-processed food (UPFs) consumption has surged globally, raising concerns about its impact on health.

Ultra-processed foods are industrial formulations typically containing ingredients not commonly used in home cooking, such as hydrogenated oils, high-fructose corn syrup, flavour enhancers, and emulsifiers. Examples of these types of foods include chips, soft drinks, instant noodles, ice cream, chocolate, biscuits, ready-to-eat meals, sausages, burgers, chicken and fish nuggets, sweet or savoury packaged snacks, and energy bars.

These foods, and the ingredients they contain, are designed for convenience and long shelf life, and to enhance palatability, but often come at the cost of nutritional value.

Now, a groundbreaking study, led by Monash University, has shed light on a particularly alarming consequence – the acceleration of biological ageing.

Biological age refers to how old a person seems based on various molecular biomarkers, compared to chronological age, which is the number of years a person has lived.

A person’s biological age is a relatively new way of measuring a person’s health, and can be traced back to 2013, when geneticist Steve Horvath developed the epigenetic clock, which measures DNA methylation levels. DNA methylation is a process that modifies the function of genes.

A second generation of epigenetic clocks was developed a few years later that incorporated environmental variants such as smoking or chronological age. Among these was the PhenoAge and GrimAge clocks.

As well as diet, biological age can be influenced by genetics, general lifestyle, and environmental factors, and it can differ significantly from chronological age.

A person with a healthy lifestyle may have a biological age younger than their chronological age, while poor lifestyle choices, such as a diet high in UPFs, can accelerate biological ageing.

The Monash University study, published in the journal Age and Ageing, was led by nutritional biochemist Dr Barbara Cardoso, a senior lecturer in the University’s Department of Nutrition, Dietetics and Food. It involved 16,055 participants from the United States aged 20-79, whose health and lifestyles were comparable to those in other Western countries such as Australia. The study used the PhenoAge clock to assess biological ageing.

It found a significant association between increased UPF consumption and accelerated biological ageing. For every 10% increase in UPF consumption, the gap between biological and chronological age widened by approximately 2.4 months.

Participants in the highest UPF consumption quintile (68-100% of energy intake in their diet) were biologically 0.86 years older than those in the lowest quintile (39% or less of energy intake in their diet).

Dr Cardoso said the findings underlined the importance of eating as many unprocessed and minimally-processed foods as possible.

“The significance of our findings is tremendous, as our predictions show that for every 10% increase in total energy intake from ultra-processed food consumption there is a nearly 2% increased risk of mortality and 0.5% risk of chronic disease over two years,” she said.

“Assuming a standard diet of 2000 calories [8500 kilojoules] per day, adding an extra 200 calories of ultra-processed food, which roughly equals an 80-gram serving of chicken bites or a small chocolate bar, could lead to the biological ageing process advancing by more than two months compared to chronological ageing.”

The study used data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2010. Diet quality was assessed with the American Heart Association (AHA) 2020 and the Healthy Eating Index 2015 (HEI-15).

The association between UPF intake and biological ageing remained significant after adjusting for diet quality and total energy intake, using the above data as a baseline.

This suggested the association could be due to other factors such as lower intake of flavonoids or phytoestrogens, which occur in natural foods such as fresh fruit and vegetables, or higher exposure to packaging chemicals and compounds formed during food processing.

“Adults with higher UPF tended to be biologically older,” the study found. “This association is partly independent of diet quality, suggesting that food processing may contribute to biological ageing acceleration. Our findings point to a compelling reason to target UPF consumption to promote healthier ageing.”

The results also support earlier research linking UPF consumption to ageing markers such as telomere length (a shorter telomere length is a sign of cell ageing), frailty, cognitive decline, and dementia.

Dr Cardoso said while the study participants were from the US, the relevance of the findings apply to Australians too – on average, ultra-processed foods represented almost 40% of total energy intake among Australian adults.

She said given the global population continued to age, demonstrating the adverse effects of UPFs reinforced the need for dietary-focused public health strategies to prolong a healthy lifespan.

“Our findings indicate that reducing ultra-processed foods in the diet may help slow the biological ageing trajectory, bringing another reason to target ultra-processed foods when considering strategies to promote healthy ageing,” she said.

Mechanisms behind UPFs and ageingMechanisms by which UPFs may accelerate biological ageing include:

Nutrient deficiency: UPFs are often low in essential nutrients such as vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, which are crucial for maintaining cellular health and preventing oxidative stress.Chemical additives: Many UPFs contain artificial additives and preservatives that may have adverse effects on health, including promoting inflammation and disrupting metabolic processes.Packaging chemicals: Exposure to chemicals from food packaging, such as bisphenol A (BPA), has been linked to various health issues, including accelerated ageing.Practical steps to reduce UPF intakeTo mitigate the adverse effects of UPFs, individuals can take several practical steps:

Increase whole foods: Emphasise whole, minimally processed foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and seeds in your diet.Read labels: Be mindful of food labels and avoid products with long lists of unfamiliar ingredients.Cook at home: Preparing meals at home allows for greater control over ingredients and cooking methods.Limit convenience foods: Reduce reliance on ready-to-eat meals and snacks, opting instead for healthier alternatives.This work was carried out in collaboration with senior author Euridice Martinez Steele, from the University of Sao Paulo (Brazil), Daniel Belsky, from Columbia University (US), Dayoon Kwon, from the University of California at Los Angeles, Priscila Machado, from Deakin University, and Junxiu Liu, from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (US).

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article.

Featured image credit by Fabricio_Macedo_Photo via pixabay.

April 4, 2025

12 key titles to read this Jazz Appreciation Month [reading list]

12 key titles to read this Jazz Appreciation Month [reading list]

In honor of Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM), we celebrate the extraordinary history and heritage of jazz, exploring its music, culture, and people who made it thrive. Jazz, despite its distinctly American roots, resonates globally across cultures, languages, and musical traditions. Often described as a musical conversation between band members, with improvisation, rhythm, and swing, jazz is a powerful unifying force that builds bridges, connecting people from all walks of life. Whether it’s the soulful strains of a saxophone in New York or the lively rhythms of a jazz band in Paris, jazz brings us together and celebrates our shared humanity.

We hope that this reading list of 12 stimulating and inspiring books—like the number of keys in an octave—will spark your interest and encourage your participation in this truly original American art form—to read books about it, to study the music, to play and perform, and ultimately to listen to all things jazz.

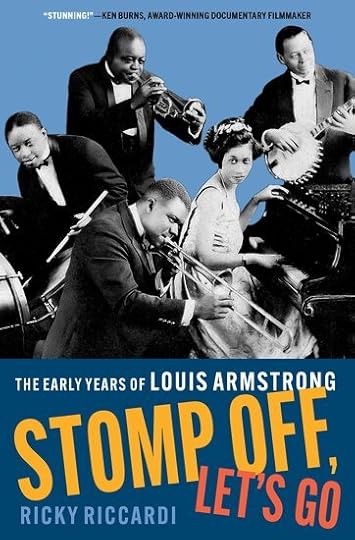

1. Stomp Off, Let’s Go by Ricky Riccardi

1. Stomp Off, Let’s Go by Ricky RiccardiTwo-time GRAMMY award-winning author and Louis Armstrong expert Ricky Riccardi tells the enthralling story of the iconic trumpeter’s meteoric rise to fame. Beginning with Louis Armstrong’s youth in New Orleans, Riccardi transports readers through Armstrong’s musical and personal development, including his initial trip to Chicago to join Joe “King” Oliver’s band, his first trip to New York to meet Fletcher Henderson, and his eventual return to Chicago, where he changed the course of music with the Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings.

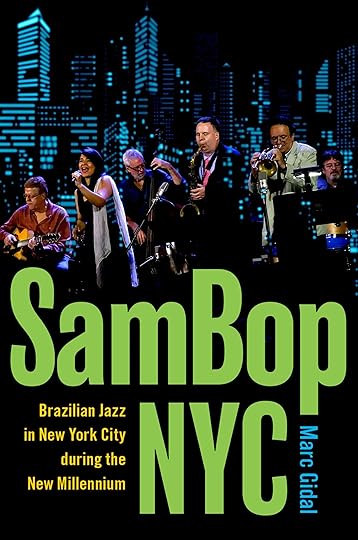

2. SamBop NYC by Marc Gidal

2. SamBop NYC by Marc GidalIn New York City during the first decades of the new millennium, over two hundred professional musicians play music that combines jazz with Brazilian genres. Blending American and Brazilian music, these musicians continue the legacies of bossa nova, samba jazz, and other styles, while expanding their skills, cultural understandings, and identities.

3. The Classroom Guide to Jazz Improvisation by John McNeil and Ryan Nielsen

3. The Classroom Guide to Jazz Improvisation by John McNeil and Ryan NielsenThis book provides what music educators have sought for decades: an easy, step-by-step guide to teaching jazz improvisation in the music classroom. Offering classroom-tested lesson plans, authors John McNeil and Ryan Nielsen draw on their combined 54 years of teaching experience and extensive work as professional jazz musicians to remove the guesswork and mystique from the teaching process.

4. James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” by Tom Jenks

4. James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” by Tom JenksTom Jenks’s reading of James Baldwin’s short story follows a scene-by-scene, sometimes line-by-line, discussion of the pattern by which Baldwin indelibly writes “Sonny’s Blues” into the consciousness of readers. It provides ongoing observations of the story’s aesthetics and musical progression, with references to Edward P. Jones, Charlie Parker’s music, Billie Holiday’s “Am I Blue?,” and John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.” Jenks pays attention to Baldwin’s oratorical gifts, the biblical references in the story, its time structure, characterizations, dramatic action, and its total effect.

5. Chasin’ the Sound by Brian Levy and Keith Waters

5. Chasin’ the Sound by Brian Levy and Keith WatersWritten for all experience levels, Chasin’ the Sound encourages hands-on learning with activities that highlight the intangible yet key aesthetics of sound, groove, and feel. Studying jazz fundamentals alongside well-known examples of those fundamentals in practice, students and instructors will gain a broader and more meaningful understanding of the art of improvisation.

6. Rhythm Man by Stephanie Stein Crease

6. Rhythm Man by Stephanie Stein CreaseIn this first comprehensive biography of Chick Webb, author Stephanie Stein Crease traces his story in full, showing how his skills and innovations as a bandleader helped catalyze the music of the Swing Era and the growing big band industry, allowing Webb to become one of the most influential musicians in jazz history. Crease explores Webb’s personal and professional struggles as he rose to the top of the increasingly competitive world of big band jazz.

7. Hearing Double by Brian Kane

7. Hearing Double by Brian KaneWhen we talk about a jazz “standard” we usually mean one of the many songs that jazz musicians repeatedly play as part of their core repertoire. Unlike classical music, standards are transformed in performance, rearranged, improvised upon, and altered with new chords and melodies. These transformations can be minor or radical revisions. Brian Kane explores what gives a standard its identity by offering a new theory of musical works, addressing the unique challenges presented by standards.

8. The Gerry Mulligan 1950s Quartets by Alyn Shipton

8. The Gerry Mulligan 1950s Quartets by Alyn ShiptonFounded in Los Angeles in 1952, The Gerry Mulligan Quartet was the first small jazz ensemble without a chordal instrument like a piano or guitar. Using original scores and detailed transcriptions of Mulligan’s work, Shipton offers an intimate look at Mulligan’s musical development from the initial quartet with Chet Baker to its successors with Bob Brookmeyer, Jon Eardley, and Art Farmer. Featuring original interviews, and presenting a fresh take on Mulligan’s harmonic creativity, this book traces the ups and downs of his heroin addiction, imprisonment, sobriety, and eventual musical triumph.

9. Rabbit’s Blues by Con Chapman

9. Rabbit’s Blues by Con ChapmanJohhny Hodges’ celebrated technique and silky tone marked him then, and still today, as one of the most important and influential saxophone players in the history of jazz. In this first ever biography, Rabbit’s Blues details Hodges’ place as one of the premier artists of the alto sax and his role as co-composer with Duke Ellington.

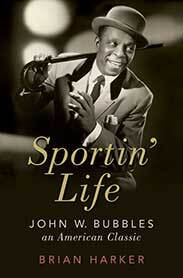

10. Sportin’ Life by Brian Harker

10. Sportin’ Life by Brian HarkerJohn W. Bubbles was the ultimate song-and-dance man. In this compelling and deeply researched biography, his dramatic story is told for the first time. Coming of age with the great jazz musicians like of Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, and Ella Fitzgerald, he influenced jazz with his rhythmic ideas. A groundbreaking tap dancer, he provided inspiration to Fred Astaire, Eleanor Powell, and the Nicholas Brothers. His vaudeville team “Buck and Bubbles” captivated theater audiences for more than thirty years. Most memorably, in the role of Sportin’ Life, he stole the show in the original production of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess.

11. Instrument of the State by Benjamin J. Harbert

11. Instrument of the State by Benjamin J. HarbertInterweaving oral history and archival research, Benjamin J. Harbert expands on folkloric definitions of “prison music” to show how incarcerated musicians found small but essential freedoms by performing jazz, R&B, country, gospel, rock, and fusion throughout the twentieth century. This book considers the ways in which music manifests among the incarcerated and the prison administration as a lens to better understand state power and the fragments of hope and joy that exist in its wake.

12. The History of Jazz by Ted Gioia

12. The History of Jazz by Ted GioiaUniversally hailed as the most comprehensive and accessible history of the genre of all time, and acclaimed by jazz critics and fans alike, this magnificent work covers the latest developments in the jazz world and revisits virtually every aspect of the music.

Explore even more great jazz titles over on Bookshop:

Bookshop USBookshop UKOxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers