Oxford University Press's Blog, page 5

May 14, 2025

Speaking in and about tongues

First of all, let me thank those who commented on the previous posts and said so many kind words about the blog. Invigorated by this support, I am ready to ask the greatest question that should bother a philologist: Why is the tongue called tongue?

The tongue allows us to speak, and it seems that language historians should know how this word came into being. Perhaps they even solved the riddle (at least, to a certain extent). In any case, they reconstructed several long words that look like the searched-for protoform, the alleged ancestors of many related or seemingly related forms of tongue. Some such forms look fanciful, while others are more realistic. At the moment, this is all one can say about the situation at hand.

First: a digression is perhaps in order. It seems that when our very distant ancestors acquired the gift of articulate speech, their first utterances were short and either sound–imitative or at least sound-symbolic. Boom, crack, tread, and pat look like acceptable early words, while prestidigitation or imperturbability do not. Historical linguists reconstruct ancient roots, all of which are short, even very short. The reality of such roots has been questioned more than once, but their existence is probable. As time went on, short roots, we assume, acquired prefixes and suffixes, added sounds, lost sounds, and changed them according to “laws” or in violation of them, and finally acquired the shape familiar to us. This is the stuff of courses on historical linguistics.

Tongue in cheek. A group of linguists discussing the origin of tongue.

Tongue in cheek. A group of linguists discussing the origin of tongue. Photo by the Scottish Government. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

But a strange phenomenon attracts our attention. Some rather old languages are known to modern scholars. Tocharian, Hittite, and Sanskrit, let alone Classical Greek, Latin, and fourth-century Gothic have come down to us. To be sure, they are millennia away from the hypothetical date of the first articulate words. People hardly became glib talkers more than a hundred thousand years ago. For comparison: Hittite inscriptions are about 18,000 years old. We have no means to bridge the gap of ninety or so millennia, though we may, for the sake of the argument, agree that once upon a time one language existed and that (consequently) all the languages spoken today go back to that single primordial ancestor.

Fast forward from Hittie to Modern English. Wherever we look, we observe that words tend to become shorter and shorter. English is of course an extreme case in the Indo-European family (nearly all its old words are monosyllabic: come, go, do, see, and so forth). But abridgement characterizes the history of even the most conservative languages. The famous linguist Otto Jespersen called this change progress. It is more profitable to stay away from such emotional terms and speak only about development. There is no connection between the state of any given society and the structure of its language, but we note that some tribes living under primitive conditions have extremely long words. On the other hand, Old Chinese and Old Vietnamese were monosyllabic languages. To be sure, this could be the result of a long period of evolution.

Our modern word tongue is a short word and has almost the same form all over the Germanic-speaking world: Dutch tong, German Zunge, and their likes. The old forms were similar: compare Old Norse tong and Gothic tuggo (pronounced as tungo). The oldest Germanic form must also have been tungo-, but etymologists, naturally, want to know whether a common oldest Indo-European form can be reconstructed. And did it mean “tongue”? To accomplish this task, it is necessary to look at the name of the tongue in Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and everywhere. The search has been accomplished, but the results produced more questions than answers.

Finger lickin’ good.

Finger lickin’ good. Photo by Tom Fisk.

The Latin for “tongue” is lingua, familiar to us from bilingual, linguistics, and other words having this root. By the First Consonant Shift, Germanic t should correspond to non-Germanic d. Lingua certainly does not begin with a d, but fortunately, Latin also has dingua. The relation between these words has been an object of protracted debate. Two suggestions turn up again and again in the attempts to explain the origin of tongue in Latin and elsewhere. It seems that the sound shape of tongue has been influenced by the verb meaning “lick,” which rather regularly begins with the consonant l over a large territory. The tongue certainly licks. Analogy is a constant process, but one can only suggest, not prove, its role in such a case.

A different hypothesis refers to taboo. In days of yore, people were afraid to say certain words. You pronounce eye, and an evil spirit will attack it. Or you say bear, and the bear will come. Therefore, speakers deliberately maimed words (this is what is meant here by taboo). Perhaps the word for “tongue” also fell victim to this practice (hence lingua for dingua?). Unfortunately, I have to repeat what I said about analogy: taboo, unless observed in a modern society, can be suggested but not proved.

Other than that, the names for “tongue” vary greatly all over Indo-European. A few have some similarity to Latin, because they begin with l: for instance, Armenian lezu and Lithuanian liežùvis. Old Irish tengae may hold promise to a non-specialist, but Celtic is not Germanic, and where Germanic has t, Irish is expected to have d (by the just mentioned law of the First Consonant Shift). Or is the Celtic word a borrowing from Germanic? Though Sanskrit jihvā perhaps resembles Russian yazyk (stress on the second syllable), it is miles away from dingua/lingua. The Tocharian forms begin with k. To exacerbate our troubles, Greek glossa “language” looks very much like a square peg in this moderately round hole, and its etymology remain a riddle. I will pass over the numerous fanciful attempts to produce a protoform that allegedly yielded this almost infinite variety. Many dictionaries cite some form like dunghu or dunghawa (my transcription is simplified), with the d ~ l variation by taboo. This reconstruction is not wrong but it is uninspiring.

English bear means “brown.” The beast will never guess the origin of this taboo name.

English bear means “brown.” The beast will never guess the origin of this taboo name. Image: public domain via Picryl.

It was suggested long ago that the most ancient Indo-European form of the word for “tongue” was a compound, and that is why it was so long. A most ingenious reconstruction deciphers the original form of the word for “tongue” as dnt-ghua (this is again a simplified transcription), a compound consisting of a word for “tooth” (dnt) and a word for “fish.” The meaning emerged as “fish (or muscle) of the teeth.” A tongue does look like some fish! A similar proposal suggests that tongue was indeed a compound but made up of the words for “under” and “the roof of the mouth.”

Not every expert in the field believes that ancient Indo-European had a single protoform for “tongue,” and not everybody accepts the idea of a compound underlying the forms in different languages. The role of taboo in naming the tongue is reasonable, but of necessity, it remains a guess. A tie between the words for “tongue” and “lick” is not improbable, but it cannot be proved either. In this blog column, I have discussed the etymology of kidney, eye, ear, hand, finger, and leg. The riddles were tough but less menacing than the one to which the present post is devoted. There may be a bit of irony in the fact that of the many words whose origin linguists cannot discover, the word tongue proved to be the most intractable.

Featured image: A cow eating grass from a person’s hand. Public domain via Picryl.

May 12, 2025

Shining light on sun safety for Sun Awareness Week 2025

Shining light on sun safety for Sun Awareness Week 2025

Kicking off today, Sun Awareness Week (12-18 May) is the start of the British Association of Dermatologists’ (BAD) summer-long campaign to encourage everyone to protect their skin from sun damage and skin cancer, the most common cancer in the UK.

There are several types of skin cancer, with melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers being the most common. Melanoma develops from melanocytes, cells in deeper layers of the skin that give skin its colour. Non-melanoma skin cancers, such as basal and squamous cell carcinoma, develop from cells known as keratinocytes found in the outer layer of the skin. Simple steps like using sunscreen, avoiding sun in the middle of the day, wearing sun hats, and reducing the amount of direct sun exposure can lower your risk of both.

Recent research from the BAD journals—British Journal of Dermatology, Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, and Skin Health and Disease—offers new insights into preventing, diagnosing, and treating melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers. Here are some highlights:

Why sunscreen matters

Using sunscreen every day is one of the best ways to stay safe. The sun gives off ultraviolet (UV) rays that harm your skin and raise skin cancer risk, and regular use of high-SPF sunscreen can protect you. Sunscreen comes in many forms, like creams, lotions, sprays, and sticks. Apply it 15-30 minutes before going outside. Reapply every 2 hours, or after swimming or intense physical activity.

Sunscreen prevents skin cancer and premature ageing (called photoageing), but it’s good to know the facts. A recent narrative review found possible downsides of using sunscreen, like allergic skin reactions and concerns about endocrine disruption. Some ingredients, like preservatives and fragrances, may cause allergic skin reactions, though evidence suggests these reactions are rare. Concerns about hormone effects are low, as sunscreen stays mostly on the skin’s surface.

Photoageing: a key concern

UV rays don’t just increase skin cancer risk—they also age your skin early, causing wrinkles and spots. A recent survey across 17 countries found that people often worry more about photoageing than skin cancer. So, talking about photoageing in sun awareness campaigns could motivate more people to engage in sun protective behaviours.

A digital sun protection campaign for healthcare workers

Researchers from University of Limerick Hospital Group in Ireland tried a new digital campaign to promote skin cancer awareness among hospital staff. Their study found that staff became more positive about sun protective behaviours after the campaign, showing that digital tools could work for everyone in encouraging sun protection.

Figure from Emma Porter et. al, ‘The Impact of a Novel Digital Sun Protection Campaign on Sun-Related Attitudes and Behaviours of Healthcare Workers: A Prospective Observational Study’, Skin Health and Disease, Volume 4, Issue 6, December 2024, https://doi.org/10.1002/ski2.256

Figure from Emma Porter et. al, ‘The Impact of a Novel Digital Sun Protection Campaign on Sun-Related Attitudes and Behaviours of Healthcare Workers: A Prospective Observational Study’, Skin Health and Disease, Volume 4, Issue 6, December 2024, https://doi.org/10.1002/ski2.256Better sun habits, better outcomes

Campaigns like Sun Awareness Week make a real difference. A study from Austria found that people who improved their sun protection habits after being diagnosed with melanoma lived longer, showing that these behavioural changes can save lives.

Global melanoma trends

A population-level study across 162 countries found that melanoma diagnoses are rising over time, but death rates are steady or growing slowly. This may be related to improved screening and awareness programs for melanoma. However, this may be compounded by melanoma overdiagnosis, with some cases caught early that may not have been deadly. Researchers are still exploring this complex phenomenon.

Melanoma and gender

Men and women face different melanoma risks. This study from Australia found that, on average, women are often diagnosed with melanoma years earlier than men, especially on the torso and for thinner melanomas. Their findings suggest that sex-tailored approaches to melanoma control could improve prevention and care.

Sun safety policy in primary schools

As per the World Health Organization, school sun protection programmes may be the key to skin cancer prevention. This study carried out an online survey of primary schools in Wales to understand their sun safety policies and practices. Of 471 schools that responded, only 183 enforced their policy. Those who did not have a policy were ‘not aware of the need’ (34.6%); ‘need assistance with policy or procedure development’ (30.3%); or ‘not got around to it just yet’ (26.8%).

Skin cancer and blood cancers

This study in the Netherlands found that patients with blood cancers have a higher risk of developing skin cancers across their lifetime. This means that targeted awareness campaigns for sun protection are vital for this patient population.

Diabetes drugs and skin cancer

In this systematic review, the authors found that drugs for type 2 diabetes, especially metformin, may lower risk of non-melanoma skin cancer. This is good news for people with type 2 diabetes who are worried about developing skin cancer.

This Sun Awareness Week, we are urging everyone to prioritise sun protection to prevent skin cancer and premature skin ageing. Check your skin regularly and see a doctor if you notice any new or changing moles or other skin lesions.

Join the #SunAwarenessWeek conversation and share your sun safety tips! You can explore the latest research from the BAD journals here.

Featured image by Kaboompics.com via Pexels.

May 9, 2025

Excerpts from Electronic Enlightenment’s Spring 2025 update

Excerpts from Electronic Enlightenment’s Spring 2025 update

We have recently published five new blog posts on Electronic Enlightenment. These blogs cover a range of insightful topics and will be linked through our announcement newsletter, offering fresh insights and valuable information to you.

Each blog is crafted to enlighten and engage, providing you with information and discussions on the history of the Barham Family, Charles Bertram, William Stukeley, Phillis Wheatley Peters, and the history of slavery through the letters of well-known historical figures. Check out the excerpts below and read the full blog posts and more on Electronic Enlightenment.

“The Plantation Papers of the Barham Family” by Tessa van Wijk

After the survey of 300 letters and some legal papers, the 16 letters for this mini-edition were chosen to represent seven themes relating to the management of the sugar plantations and, specifically, the enslaved workers. The seven themes present in these letters are the following: (1) providing for enslaved people, (2) efficiency and purchasing of enslaved workers, (3) punishment and reward of enslaved workers, (4) enslaved workers rebelling, revolting and/or running away, (5) pregnancy, birth, and enslaved children, (6) illness & health of enslaved workers, and, lastly, (7) (anti-)slavery debate and sentiment….

Several of the 16 letters from the Barham Papers’ Jamaica Correspondence added to Electronic Enlightenment can tell us about the health and well-being of the enslaved people working on the Mesopotamia Estate and Island Estate….

These letters also shed light on important political developments at the time. Specifically, when it comes to the rise of anti-slavery sentiment, abolition, and the unstable political situation in European colonies.

Read the full blog here.

“Colonial Myth-making and Anti-Scottish Sentiment in Charles Bertram’s Letters to William Stukeley” by Sophie DicksonCharles Bertram urged William Stukeley to forgive his faults. These faults, he admitted, were his undying love for antiquities and his rude intrusion into Stukeley’s acquaintance. However, Bertram’s interruption of Stukeley’s professional and social circle birthed a collection of 32 letters spanning from 1746 to 1764, later collated by Stukeley. Early in their communication, Bertram revealed the spectacular discovery of what he claims were fifteenth-century manuscript fragments written by a “Ricardi Monachi Westmonasteriensis.” The manuscript detailed lost geographical information of Roman Britain, assembled from various contemporary Roman sources such as Beda, Orosius, Pliny, and Ptolemy. Through their correspondence, Bertram gradually shared fragments of the manuscript with Stukeley until its publication in 1757 as De Situ Britanniae(The Description of Britain).

Read about the manuscript here.

“Epistolary Form in the Letters from Charles Bertram to William Stukeley” by Olivia Flynn

Using the collection of 32 letters written by the literary forger Charles Julius Bertram to the Antiquarian William Stukeley between 1747 and 1763 as a case study, Flynn explores the different sub-genres of letters. The purpose and subject matter of letters of the eighteenth century vary greatly, according to the purpose and style of the letter. They included the consolation letter, familial letters, business letters, petitions, political missives, public letters to newspapers and periodicals, and, of course, love letters.

This blog post focuses on the introductory letter and the often overlooked medical diagnosis letter.

Read the blog post here.

“Slavery in the Electronic Enlightenment Collection” by Tessa van Wijk

According to Jean Le Rond d’Alembert to Voltaire [François Marie Arouet], 14 April 1760, the metaphorical use of terms such as ‘esclavage’ and ‘esclave’ is typical of eighteenth-century French authors. The connotation with the enslavement of African people or the Triangular Slave Trade was a lot less frequently present. Rather, the words ‘esclave’ and ‘esclavage’ are more often defined in opposition to freedom and liberty: “A slave, for the eighteenth century, is someone who was deprived of their freedom, whatever the form or cause of this deprivation”….

The top five letter writers with the most letters in the final list of results are Simon Taylor (57), Edmund Pendleton (42), William Cowper (23), William Fitzhugh (21), and Francis Fauquier (15). Except for William Cowper, these men all had interests in the continuation of the slave trade and slavery, and their letters can mostly be found in categories relating to the owning of and trading in enslaved people….

In Edmund Pendleton’s letters, we can clearly see that enslaved people are considered as personal property. Pendleton was an American plantation-owner and slaveowner, as well as an attorney. Several of his letters in Electronic Enlightenment discuss legal affairs, particularly inheritances.

Read the full blog post here.

“Phillis Wheatley Peters” by Kate Davies

Wheatley Peters’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) is one of the most important books to be published anywhere in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world. It is important because it is a book written by a black woman who was very well aware that her new professional status as an author held the key to her own freedom. It is important because it is a work of creative intellect, whose young writer displayed her imaginative prowess while revealing her adroit mastery of the contemporary literary forms of lyric, elegy, and ode. It is important because it is a work of faith that spoke profoundly to a committed culture of evangelical Christianity, out of which the humanitarian movement to abolish the transatlantic slave trade and chattel slavery was beginning to emerge….

What did this book contain? In her Poems, Wheatley Peters gathered a substantial collection of thirty-nine pieces, including a range of elegies and odes, and hymns. There were poems about the inspiration of breaking dawns, soft evening light and the power of memory; poems which took their cue from Old Testament verses; poems urging religious virtue upon wayward Harvard students; and poems in which Wheatley Peters shared the grief of members of her congregation at Boston‘s Old South Meeting House at the sad loss of friends and family members. One poem was importantly dedicated to Scipio Moorhead, the talented Boston artist, who, like Wheatley Peters, was one of the approximately 5,000 enslaved black people then living in Massachusetts.

Read the complete blog post here.

These excerpts have been lightly edited to fit the OUPblog’s style guide. No content was changed, and the full blog posts can be found at each of the above hyperlinks and on Electronic Enlightenment.

Featured image created in Canva.

May 7, 2025

In free fall, being also a story of and about love

In free fall, being also a story of and about love

This is a story of the adjective free, and the story is complicated. Let me begin from afar. English has the verb liberate, whose root goes back to līber, the Latin for “free.” This fact deserves our attention here because of an unexpected meaning of the plural noun līberī “children.” The word has nothing to do with liber “book,” whose origin is veiled in obscurity but from which we have library (it will be seen that liber “book,” unlike līber “free,” had a short vowel in the root). Līberī was a legal term, unlike puer and infāns (both meant “child”; for comparison’s sake, think of English puerile and infant/infantile). It was not used in the singular and consequently, could not be applied to one child. The unexpected connection between “children” and “freedom” seems to go back to the distinction between free (one’s own, “genuine”) children and the children born to the same father by a slave.

Michelangelo’s “Rebellious Slave.”

Michelangelo’s “Rebellious Slave.” Photo by Darafsh. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The second situation (slaves’ children) is known quite well from the history not only of Greece and Rome but also from medieval Europe, especially from Icelandic sagas. Such children, even if they were their parents’ favorites, were still unfree. “Free” has always been a legal term. In the past, it seems to have referred to those who enjoyed support and legal defense. Hence its connection with children (as in Latin). To repeat: the free were family members, the Old English frēobearn (“free bairns”), as opposed to slaves. The free were of course the offspring of free parents and therefore entitled to the privileges attached to legitimate birth. They had to be taken care of and protected. The phrase free life, occurring in an Old English poem, must also have meant “protected life.”

We should now look at the origin of the word free. The oldest recorded Germanic root of this word occurs, as so often, in the fourth-century Gothic Bible: it was freis (rhyming with English fees), from the more ancient frijaz. Multiple ties between freedom and kinship come to light at once. Both Old and Modern Icelandic frændi, a word containing the root of free, means not “friend” but only “relative.” Frændi, as well as Modern English friend and German Freund “friend,” looks like the present particle of a verb, related to Gothic frijon, Old English frēogan, and others, which is traditionally glossed as “to love.”

Caution is required when we approach the idea of love, because love, like many other words designating abstract concepts, has a long history. In our story, we should better ignore lovers and stay with relatives, as suggested by frændi. In the past, even more than today, relatives were the mainstay of an individual’s life. One’s safety and success depended on the support of the family (clan). Romantic love, instilled in us by poetry (“I cannot give you what men call love….”—Shelley), was alien to the oldest societies. No doubt, people had the same feelings we have, but the social context was different, and therefore they verbalized their attitudes in a different way. The Gothic verb frijon is surrounded by the words meaning “reconcile” and “take care of.” One of the Old Germanic goddesses was called Frija-Frigg (Friday commemorates her). Some dictionaries gloss her name as “the loved one,” but the older opinion that she was “the protecting one,” “the one guarding family members,” may be more to the point. Deities were not loved: they were “adored” and in return granted favors to their worshipers.

One of the most memorable Gothic words is freihals “free neck; freedom.” Its closest cognates occurred all over the Germanic speaking world and have been interpreted as “neck, unhampered by chains” or (less convincingly) as “one having legal protection and accordingly no requirement to bow his neck before a property owner.” Once again, we notice that the word free was a sober legal term that from an etymological point of view had nothing to do with love. Dictionaries no longer compare free with Greek prāús “gentle,” and this is good. By contrast, Slavic words beginning with p- and meaning “pleasant” do belong here. (Non-Germanic p corresponds to Germanic f by the so-called First Consonant Shift, often mentioned in this blog: compare English father and Latin pater.)

[image error]Wellcome Collection","created_timestamp":"0","copyright":"","focal_length":"0","iso":"0","shutter_speed":"0","title":"","orientation":"1"}" data-image-title="image-from-rawpixel-id-13958696-jpeg" data-image-description="" data-image-caption="A mouse is sitting in front of a trap with an inviting sign, contemplating the offer. Coloured aquatint.

More:

Original public domain image from Wellcome Collection

" data-medium-file="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa..." data-large-file="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa..." src="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa..." alt="" class="wp-image-151765" style="width:691px;height:auto" srcset="https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 1200w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 180w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 278w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 120w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 768w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 128w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 184w, https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploa... 31w" sizes="(max-width: 1200px) 100vw, 1200px" />Always free.Public domain image from Wellcome Collection.

The Germanic forms are also close to those in some Celtic languages. The Celts had a well-developed legal terminology, and it has been suggested that the speakers of Germanic borrowed some of it. Whether we are indeed dealing with a loanword or a cognate cannot be decided, but the similarity confirms the idea of free being a legal term and having nothing to do with love.

Gothic frijon did mean “to love,” but only insofar as it translates a verb from the New Testament, which tells us little in regard to Germanic. We observe that even in such late texts as Icelandic, ást (often in the plural), traditionally glossed as “love,” rarely, if at all, had the connotations, invoked by our word love. And its Gothic cognate ansts meant “thanks; grace; favor,” very much like Modern German Gunst (g- is a remnant of an old prefix).

By way of conclusion, I may add that since among the Germanic-speaking people free was a legal term, known to us only from comparatively late texts, it must have owed a great deal to its Latin counterpart, namely, liber (regardless of whether we should also reckon with the influence from the Celts). A legal term is the product of abstraction and should be understood in its context. In our research, we deal with both “words” and “things.” Above, many concepts have been invoked. The main one is free. A free person was not a slave. Freedom presupposed mixing and mingling with other free members of the community. People didn’t have to “love” their relatives, but they were supposed to be loyal to them. One’s great debt was to one’s children. Hence Latin līberī. Pagan deities took care of married couples. Here, too, no one was made to “love” one’s spouse, though being in love never hurt anyone.

Freedom means belonging to the family.

Freedom means belonging to the family. Greuze, Filial Piety, 1763. The Hermitage Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Most words we use today do not mean (or at least do not mean exactly) what they meant in the past. One of them is “love.” Also, words broaden and narrow their meanings. Today, free is an all-encompassing word. Birds are free to fly, animals are free to roam (see the previous post), and we are free to do what we want. It certainly was not so even fifteen hundred years ago. Perhaps one even had to learn a word for this concept from a neighboring tribe. Initially, I also wanted to discuss the etymology of the verb fall. But though this ancient verb occurs in practically the same form all over the Germanic-speaking world, nothing (nothing at all!) has been discovered about its etymology. People fall from grace and fall in love without knowing the origin of the verb. This is what I call a major accident. Feel free to offer your hypotheses.

Featured image: Homer, Alaska, United States – Bald Eagle in mid-air flight over Homer Spit Kenai Peninsula. Photo by Ragamuffin Brian. CC-BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

May 1, 2025

Elleke Boehmer’s seminal Colonial and Postcolonial Literature at 30

Elleke Boehmer’s seminal Colonial and Postcolonial Literature at 30

May 2025 marks the 30th anniversary of Elleke Boehmer’s seminal text Colonial and Postcolonial Literature: Migrant Metaphors, first published by OUP in 1995 with a second edition following a decade later. It remains a landmark publication in the field of colonial and postcolonial literature and beyond, read, studied, and taught the world over.

To mark this wonderful achievement, Elleke Boehmer reflects on her book and its longevity and shares some of her “must reads.” We are also pleased to offer chapter 4 “Metropolitans and Mimics”—as chosen by the author—free-to-read this May.

“I had no idea that, 30 years on, the book would still be globally read, cited, prescribed, and discussed…

Colonial and Postcolonial Literature: Migrant Metaphors continues to find its way to readers right around the world. In this sense, it is not unlike the migrating metaphors of the title—the images and motifs connecting imperial and postimperial texts that the book explores throughout.

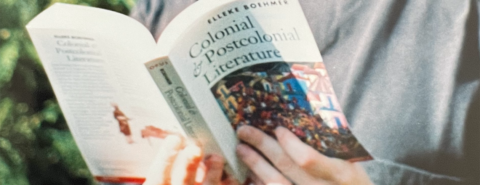

Elleke Boehmer holds a copy of the first edition on publication day, 1995.

Elleke Boehmer holds a copy of the first edition on publication day, 1995.Used with permission.

When I first published the book, I hoped that it would give greater profile to the great wealth and variety of postcolonial writing, alongside investigating its complicated roots in traditions of empire writing. On balance, I daresay that it has achieved those aims. But I had no idea that, 30 years on, the book would still be globally read, cited, prescribed, and discussed, as my academic news feeds tell me it is. I ask myself what its features are that have contributed to its ongoing success. From what I can tell, these include the book’s interest in empire as a system of textual circulation, and also its focus on the exchange of metaphors of land and belonging that interlink Anglophone postcolonial writings worldwide. Essays from across the postcolonial and world literature fields, including in French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch, have picked up on these aspects. The translation of the book into Mandarin in 1999 seems to have ensured the book’s position also as prominent critical text on university courses in China. About 15 years ago, when first I visited the country, wherever I went people said kind things about the book, and talked about its beautiful cover, based on a painting by the Australian artist Lisa Hill.

The second and expanded edition, published in 2005, offered an updated bibliography and timeline, and two brand-new chapters featuring more postcolonial women writers from the turn of the new century, and more coverage of Indigenous and First Nations authors from countries like Aotearoa/New Zealand and Canada.

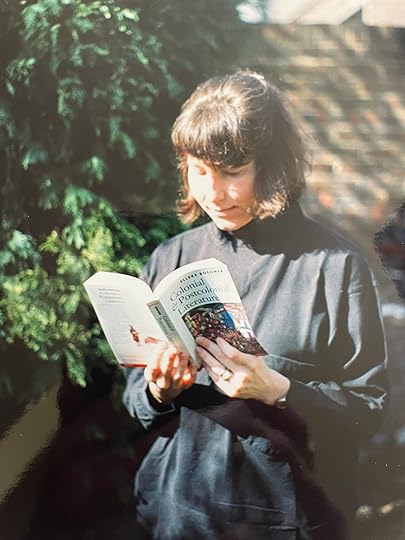

Elleke Boehmer, Oxford, 2025

Postcolonialism: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd edition

Robert Young

Postcolonialism: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd edition

Robert YoungFascinating for its treatment of the postcolonial as a mind-set, as expressed in a wide range of cultural forms.

Pacific Islands Writing: The Postcolonial Literatures of Aotearoa/New Zealand and Oceania

Michelle Keown

Pacific Islands Writing: The Postcolonial Literatures of Aotearoa/New Zealand and Oceania

Michelle KeownA sparkling and wide-ranging discussion of the postcolonial writing of a region that covers half the surface of the earth, oceanically-speaking.

Present Imperfect: Contemporary South African Writing

Andrew van der Vlies

Present Imperfect: Contemporary South African Writing

Andrew van der VliesA far-reaching account of post-millennial writing from South Africa, through the sometimes-unlikely lens of affect theory.

V.S. Naipaul, Caribbean Writing and Caribbean Thought

William Ghosh

V.S. Naipaul, Caribbean Writing and Caribbean Thought

William GhoshA compelling account of the towering figure of V.S. Naipaul set in relation to the layered Caribbean contexts from which his writing sprang.

Editor’s note: Read William Ghosh writing on the OUPblog: Homi K. Bhabha on V.S. Naipaul: in conversation with William Ghosh

Live Artefacts: Literature in a Cognitive Environment

Terence Cave

Live Artefacts: Literature in a Cognitive Environment

Terence CaveA provocative study of literary writing, postcolonial or otherwise, as an instrument through which we come to new understanding.

All books cited in this blog are available to read via Oxford Academic. Use your institutional access to sign in , or if you don’t have access, recommend Oxford Academic to your library .

Featured image by Elleke Boehmer and used with permission.

April 30, 2025

Sauntering is hard work

To saunter “to walk in a leisurely way, stroll” is a verb, famous for its etymological opacity. It is instructive and a bit frustrating to read the literature on this word, published between roughly 1874 and 1910, though a few amusing notes in my collection antedate the eighteen-seventies. No one knows where saunter came from. Charles II was seemingly fond of “sauntering.” That monarch seldom denied himself the pleasure of walking in the royal gardens and paying a visit to one of his mistresses. Saunter clung to Charles II, and probably for good reason. The obscurity of the verb and the playful connotations, attached to it, suggest that saunter might be seventeenth-century slang, a humorous neologism. If I am right, this may be the reason the verb’s origin is almost beyond reconstruction.

Sauntering.

Sauntering. Image: CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

Saunt(er) has a French look, like so many other words rhyming with its root (daunt, flaunt, gaunt, taunt, vaunt,andso forth), but may still be an English coinage: think of our nineteenth-century verb gallivant. John Minsheu (or Minshew), the author of the first etymological dictionary of English (1617), did not include saunter, most probably, because he had never heard it. Indeed, an earlier and much rarer verb saunter “to muse,” seems to have existed, but no one knows whether it was the same word. Something in the sound complex saunter, with its frequentative suffix –er (as in chatter or pitter–patter), must have suggested a leisurely activity.

The second etymological dictionary of English appeared in 1671. Its author, Stephen Skinner, included the verb and even had an idea of its origin: allegedly, the etymon of saunter was French sauter “to jump” (look up saltation in English dictionaries for the Latin root of sauter). But soon a hypothesis emerged that outlived many others. Sancta terra “Holy Land” was conjured up, “because when there were frequent Expeditions to the Holy Land many Idle Persons went from Place to Place upon pretence they had taken the Cross upon them or intended to do so, and to go thither.” This is Nathan Bailey (1721), whose dictionary was revised and reprinted countless times. His derivation of saunter from sancta terra (or its translation into French) stayed until the age of serious comparative philology.

However, not everybody rejected Bailey’s derivation of saunter. I’ll quote Ernest Weekley’s etymological dictionary. “SAUNTER: ‘From c. 1660, to roam loiter, and earlier and rare saunter, to muse to hesitate, being perhaps a different word.’ Etymologists of the 17th century agree in deriving from French sainte-terre, Holy Land. Although this etymology is now derided, it may be partly true [!]. I suggest as origin Spanish santero ‘sometimes an hermit, sometimes one that lives with the hermit, and goes about questing for him and his chappel’ [Stephens, a 1706 dictionary of Spanish]. This word is also used of a ‘shrine-crawler’ in general. We may compare Italian romigare, ‘to roame, to roave or goe up and downe solitarie and alone as an hermit’ (Florio [a 1598 Italian dictionary] ….” ROAM: “‘Traditionally from Rome, as place of pilgrimage’; cf. Old French romier, pilgrim to Rome, Spanish romero, Italian romeo ‘a roamer, a wanderer, a palmer.’ The NED [= OED] altogether rejects this and suggests Middle English ramen, a cognate with Old High German rāmen ‘to aim at, strive after.’ It is quite clear that roam was early associated with Rome, the earliest occurrence of ramen… being connected in the same line with Rom-leoden ‘people of Rome’. The word is also older than dictionary records, as roamer, quoted by NED from Piers Plowman, was a surname in 1273…, surviving as Romer. For another word that may have influenced roam see saunter.”

Roaming to Rome.

Roaming to Rome. Study for Pilgrims at Emmaus, Claude Lorrain. CC0 via the Art Institute of Chicago.

Walter W. Skeat kept returning to saunter and ended up saying “of unknown origin.” Those interested in the history of saunter waited with impatience for the appearance of the volume of the OED containing the mysterious word, but Henry Bradley, the volume’s editor, failed to solve the riddle. Nor did James A. H. Murray, the chief editor of the OED, ever write anything about saunter. The OED online offers no solution either, but it made one important concession. The original OED rejected any connection between roam and Rome, while the latest version of the great dictionary admits, even if without much enthusiasm, Weekley’s explanation (Weekley’s name does not appear in the entry, but this fact is irrelevant). If roam goes back to Rome, saunter con be derived from sancta terra!

Roaming and sauntering are not always the same activities.

Roaming and sauntering are not always the same activities. Photo by Kallie Calitz. CC0 via Pexels.

However, I don’t think the two are connected. Saunter “stroll” seems to have turned up too late to be derived from sancta terra, and if we add saunter “muse” to the equation, the senses won’t fit. Also, I keep thinking that saunter was coined or revived in the palace slang of King Charles II, and if so, at that time, everybody would have known the reference to pilgrims, but Skinner did not. Thus, roam may not throw light on saunter.

There has been a vague feeling that saunter consists of the prefix s and some Romance root. Hence the suggested etymon s’adventurer “to expose oneself to danger.” Skeat at one time reluctantly accepted this uninviting solution, though he admitted that no analog of such an odd derivation could be found. Auntre, the Old French for “adventure,” loomed large in various hypotheses, but no one could account for initial s, and of course, “to adventure oneself” sounded odd. The latest attack on saunter known to me was made in 1945. Leo Spitzer (Philological Quarterly 44, pp. 27-28) derived the verb from Old French cintrer “to mold an arch” (originally “to gird”) and then, allegedly, to “search, stroll, muse.” Perhaps saunter “to muse” and saunter “to stroll” do belong together, but it is rather unlikely that the verb that interests us has a long, complicated history between French and English.

Here are a few other suggestions, given below for amusement’s sake. “Is it possible that sauntering should be derived from sanitas, and have, when applied to a walk, the same meaning as our common word constitutional?” (1874). Our common word! Cornelia Blimber informed little Paul Dombey that she was going for a constitutional, and Paul wondered what that was. If you, too, wonder, (re)read the unforgettable Chapter 12 of the novel Dombey and Son. Constitutional, a piece of university slang (no citations predating 1829 in the OED; Dombey and Son was published in installments between 1846 and 1848), was not so short-lived, it appears. Another guess, antedating Weekley: “The dual signification of [Spanish] santéro, i.e. ‘one who collects alms for a holy man or hermit’ and ‘a hypocrite’, together with the lazy life led by like hangers-on of the Church, may serve to render such a supposition [santero as the etymon of saunter] plausible—at least on the surface” (1889). “Armstrong’s Gaelic Dictionary has sanntair, a stroller, a lounger—derived from sannt, lust or carnal inclination—and sanntach, lustful; whence to Santee—to prowl about and follow women with a lustful desire” (thus, saunter from Gaelic; 1875). And so it goes (one luminary after another): Hensleigh Wedgwood, Walter W. Skeat, Richard Morris, and even the indomitable Frank Chance. Etymological sauntering, it appears, is indeed hard work.

Featured image: English School, circa 1665. Double portrait of King Charles II and Catherine of Braganza. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

50 years after the fall of Saigon [reading list]

50 years after the fall of Saigon [reading list]

On 30 April 1975, the Vietnam War came to a historic end with the fall of Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, to North Vietnam forces, marking a significant turning point in world history. This day is remembered for the profound impact it had on the lives of millions, the geopolitical landscape, and the course of modern history. As we commemorate the anniversary of this pivotal event, we reflect on the sacrifices made, the lessons learned, and the enduring hope for peace and reconciliation.

Access the featured books and chapters on this reading list via your institution’s library or recommend to your librarian to gain access.

Fire and Rain by Carolyn Woods Eisenberg

This gripping account interweaves Nixon and Kissinger’s pursuit of the war in Southeast Asia and their diplomacy with the Soviet Union and China with on-the-ground military events and US domestic reactions to the war conducted in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Drawing upon a vast collection of declassified documents, Eisenberg presents an important re-interpretation of the Nixon Administration’s relations with the Soviet Union and China vis-à-vis the war in Southeast Asia.

Vietnam at War by Mark Philip Bradley

The Vietnam War tends to conjure up images of American soldiers battling an elusive enemy in thick jungle, the thudding of helicopters overhead. But there were in fact several wars in Vietnam, including an anticolonial war with France and a civil war between the North and South. Vietnam at War looks at how the Vietnamese themselves experienced all of these conflicts, showing how the wars for Vietnam were rooted in fundamentally conflicting visions of what an independent Vietnam should mean that in many ways remain unresolved to this day.

Death of a Generation by Howard Jones

For many historians and political observers, what John F. Kennedy would and would not have done in Vietnam has been a source of enduring controversy. Based on new evidence—including a revelation about the Kennedy administration’s involvement in the assassination of Premier Diem—Howard Jones argues in his book that Kennedy intended to withdraw the great bulk of American soldiers and pursue a diplomatic solution to the crisis in Vietnam.

Number One Realist by Nathaniel L. Moir

In a 1965 letter to Newsweek, French writer and academic Bernard Fall (1926-67) staked a claim as the “Number One Realist” on the Vietnam War. This is the first book to study the thought of this overlooked figure, one of the most important experts on counterinsurgency warfare in Indochina.

“Hanoi’s National Liberation Strategy, 1954–1975” by Pierre Asselin

This chapter from The Oxford Handbook of Late Colonial Insurgencies and Counter-Insurgencies considers the strategies and tactics used by Vietnamese communist leaders to defeat the United States and its allies in the Vietnam War. It demonstrates that the guerrilla warfare that has come to define the war in the West was in fact only one aspect of a highly sophisticated campaign to “liberate” the Southern half of the country and bring about national reunification under communist aegis.

“The Literature of Peace: A War Refugee’s ‘Orphaned Voice’ in The Sympathizer”by Pamela J. Rader

This chapter from The Oxford Handbook of Peace History considers The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen, a Vietnamese American refugee’s perspective on the war waged on Vietnamese soil. In the tradition of novels as vehicles for social change, the fictional confessional chronicles the lasting devastation of war, cultural imperialism, and nationalism through its eponymous, biracial, double-agent narrator who subscribes to the loyalty of two brothers instead of the two countries he serves.Art, specifically fiction, becomes an act of resistance to assert the loss of individualism and freedom of thought in promoting a culture of peace.

The Dragon in the Jungle by Xiaobing Li

Western historians have long speculated about Chinese military intervention in the Vietnam War. It was not until recently, however, that newly available international archival materials, as well as documents from China, have indicated the true extent and level of Chinese participation in the conflict of Vietnam. For the first time in the English language, this book offers an overview of the operations and combat experience of more than 430,000 Chinese troops in Indochina from 1968-73.

Feature image by USMC Photo by GySgt Russ Thurman. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

April 27, 2025

What to do with too many books?

What to do with too many books?

A while ago, my wife and I had some work done on our house, which entailed packing up a half-dozen bookcases until the work was done. We took the opportunity to sift through our books and to decide what we no longer needed. Deciding what to keep and what to let go of was a delicate negotiation. But equally tricky was deciding what to do with books we no longer needed.

As we thought through the winnowing process, we reached a handful of conclusions.

Don’t just try to dump all your unneeded books to your local public or university library. You are likely to be disappointed. Libraries don’t need your old textbooks, reference books, and popular fiction. If the books are important, the library may already have them or have a later edition. And remember, it costs libraries money to process circulating books, so they may actually lose money by putting your donations on the shelf. Some libraries will even encourage you to make a monetary donation to cover processing.If you do donate to libraries, don’t be too disappointed if your books end up on a booksale shelf in the library or are quietly discarded. Libraries too run out of space and they cannot keep every gift they receive. (I once knew a faculty member who found his esoteric treasures in the library’s dumpster, fished it out, and donated the books again. They were discarded once more, retrieved again, and re-donated until the library administrators finally put an end to it.) A more satisfactory way to donate is to research your target library’s collection. Figure out which of your books your library already has or has access to electronically. That way you can determine what they might actually need and want. We identified several boxes of books that fit our library’s collection and donated them along with a list of titles to make things easier. You don’t have to donate everything at once. If you have a little storage space, stagger your donations. We have another couple of boxes waiting to be researched and donated. But it doesn’t make sense to overwhelm the library staff or yourself.The flip side of deciding what to donate is deciding what not to donate. You want to keep things you are currently working with, of course. I’ve also kept books that my local libraries don’t have (and don’t necessarily want) but that are important to my work (classics of linguistics or older style guides are still on my shelves along with books from friends and former teachers). Be realistic. Don’t expect your donation to be on the shelf in the library the very next day. Books need to be processed, bar-coded, security-stripped, and entered into the circulation system, all of which takes time and staff. If you think you may still need a particular book in the near future, hang onto it a bit longer. The library will still be there.There will always be some books that your local libraries don’t need and that you don’t need to hold onto either. If they seem make to be a coherent collection—the history of detective fiction, food narratives, fabric arts, forensic linguistics, or American dialects, for example—you might find a specialized library that is interested in them, though you may have to pay for shipping (at the lower book rate). If your remainders are more thematically random, they may need to go to your local thrift stores or to the little free libraries in many neighborhoods. You can try to sell them to second-hand bookshops, but you’re likely to end up with just enough for coffee.Take your time, be strategic and realistic, and remember that once you’ve made your donations, you’ll have some room on your bookshelves for new acquisitions.

Featured image by Leora Dowling via Unsplash.

April 25, 2025

Subversion: history’s greatest hits

Subversion: history’s greatest hits

Subversion—domestic interference to undermine or manipulate a rival—is as old as statecraft itself. But most of what we know about the subject concerns the Cold War and focuses on big powers maliciously manipulating the domestic politics of small ones. To understand how subversion fits into the new epoch of great power rivalry, to know what’s really new and what’s old hat, we need a primer on great power subversive statecraft through the ages. And we need this history to look at all forms of subversive statecraft, not just conventional ones, such as election meddling or propaganda.

A Measure Short of War provides just that, revealing that most of today’s fears and hopes surrounding subversion would have been familiar to the statesman of earlier ages. Check out highlights from some of the cases detailed in the book:

Featured image by Daniele Levis Pelusi on Unsplash.

April 24, 2025

Organizations are our greatest achievement

Organizations are our greatest achievement

There are many contenders for the award of humanity’s greatest achievement. Some say its writing. Others say its agriculture. Electricity, space travel, and human rights are also possibilities. I disagree with them all.

It’s not that I don’t like writing, agriculture, human rights, and all the rest. They’re fab. It’s just that I think the greatest thing we humans ever did was figure out how to form ourselves into organizations. My vote goes to the weird and wonderful social structures we humans build to get more or less complicated stuff done, from launching spaceships to brewing craft beer.

Nothing really happens in the world without organizations. We enter the world in an organized way, with the help of hospitals and maternity wards. We also leave the world in an organized way, with the help of funeral homes and religious ceremonies. Everything in between is stuffed full of organizations of every kind imaginable—schools, universities, social clubs, gossip groups, government agencies, banks, tech companies, and so on. Even the time I set my alarm in the morning involves an organization. I don’t want to be up at seven, but the organization I work for starts early, so I fit in with that. It seems only fair.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that many of the things touted as our greatest achievements are intimately linked to organizations—even writing. In fact, especially writing, which was developed out of arithmetical techniques used in record keeping. The point here is that we figured out how to write, not to record the intricate beauty of human life, but to better process, store, and manage information. It is precisely because of organizations that our oldest written document is a list of ‘goods received’ at a brewery, not a love letter from some long-lost beau.

This might feel a touch tragic, but it says something very profound about what it is to be human. Most obviously, that we’ve always had a predilection for booze—but more importantly, that fundamentally we’re an organized species. It’s who we are. Humans build organizations, of all sorts of different shapes and sizes, and for all sorts of different reasons.

At some points in our history our capacity to build organizations has been really quite impressive. At other times, less so—the demise of the Roman Empire was a particularly dark period. The organizations we have today are arguably the most impressive that have ever existed—they’re incredibly complex and productive. The very biggest, like the UK’s National Health Service, have upwards of a million people in them. Some, like the US Department of Defense, have more than twice that, and they’re literally reshaping the world we live in right before our very eyes.

Yet, most of the organizations we have today have distinctly ancient origins. They’re not old, as such, but they’re based on some pretty ancient innovations. For example, bureaucracy can be tracked back to the invention of writing, while the concept of organizing for the ‘public good’ similarly dates back millennia. At the very least to a 5,000-year-old chain of left-luggage offices in Syria’s Balikh River valley.

State-run bureaucracies like the ones governments use to collect taxes today are basically a Chinese invention. The Qin Empire (c.220 BCE) gave us large large-scale public administration, as well as the concept of an HR department and entrance exams.

The corporation was invented by the Romans, where it was at least partly responsible for the meteoric rise and fall of their empire. Did you know that pretty much all the ancient Roman monuments we goggle over today (and indeed many of Europe’s major roads) were built by corporations under contracts from the Roman state?

Even the founding principles of the industrial revolution are not that new. Modern factories and the idea of mass-produced, standardized products can trace their linage back at least 4,000 years to the Harappans of the Indus River valley.

Of course, another part of the story of human organization is that most people in the world do not actually work in mainstream, ‘formal’ organizations. The truth is that most people on this planet will never hold a contract of employment in organization of any kind—they’ll work informally, in shadow factories and on pop-up market stalls. Indeed, a significant number will work in organizations that are explicitly banned in the countries they live in—they’ll work in criminal organizations, like the Japanese Yakuza or the Italian ‘Ndrangheta.

The point is that there are an infinite variety of different organizations out there, all doing different things in different ways. Sure, some of them aren’t that great, but the rest have done some pretty awesome things—like codify and disseminate the concept of human rights, put people into space, and build computers capable of outthinking us. Organizations define the world we live in, and they reflect the best and worst of what humanity is capable of.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers