Oxford University Press's Blog, page 10

February 5, 2025

Slow and fast worms, herring, and their linguistic kin

Slow and fast worms, herring, and their linguistic kin

I received several questions in connection with my post for January 29, 2025, on the origin of the word eel and decided to answer them right away and in doing will revive the format of “gleanings.”

Slowworm Another slowworm, once a worm-worm.

Another slowworm, once a worm-worm. Image © Hans Hillewaert. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The main question in need of elucidation concerns English slowworm. Why should slowworm be classified with tautological compounds, that is, with compounds consisting of two very close synonyms (like pathway, for example)? Obviously, the adjective slow is not a synonym of the noun worm! I wrote about slowworm in An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology (2008), but this dictionary is not “popular,” and anyway, my explanation does not seem to have been accepted by those few who have dealt with the word since 2008. Therefore, I will restate my conjecture, without going deep into the history of the question, and with as few technicalities as possible.

Slowworm will probably remain obscure regardless of my explanation. Though the word existed in Old English and had a few cognates elsewhere, the etymologist is left with several equally doubtful solutions and has to choose the one that looks the least troublesome, rather than the one that clinches the argument once and for all. As noted, slowworm is not an isolated formation in Germanic. For example, in some Scandinavian languages, words like ormslo correspond to slowworm. We can see at once that the elements of this compound can be reversed: orm + slo = slow + worm. It follows that both are or once were close synonyms. Otherwise, the puzzling variation slowworm ~ ormslo will remain unexplained. For instance, steam engine cannot mean the same as engine steam, but courtyard makes as much sense as yardcourt, even though yardcourt does not exist. It is my contention that a satisfactory etymology of slowworm should demonstrate that slow– in it once designated some kind of “worm.” If it is true, we’ll end up with worm-worm of some kind.

A charming courtyard. It would smell as good if it were called “yardcourt.”

A charming courtyard. It would smell as good if it were called “yardcourt.”Image by Fabien from Pixabay

To begin with, in the past, worm used to mean “snake” and not only “worm.” In all the oldest Germanic languages, “worm” referred not only to a serpent but even to a dragon. (See the header with an image of Fafnir, the dragon of Scandinavian mythology.) Anyway, the slowworm is neither a dragon nor a worm but a lizard, though Old English slāwyrm glossed various Latin names of serpents and lizards, as the first edition of the OED already indicated. Numerous older sources explain slowworm as “slay worm” or “worm striker.” But the slowworm does not feed on worms. Reference to slow makes no sense either, because sloth does not characterize the movements of this animal. Though some regional Norwegian and English words for “slime” have also been cited in this connection, none of them explains anything about the slowworm’s nature. And of course, this lizard is not a slow eater or a slow creature (a sluggard), or a slimy animal.

Among the rather many suggestions about the origin of slow– in slowworm, the one that compares slow– in this word with German Schlange (from the older form slango-) “snake” may be preferable to all the others. This etymology was offered as early as 1891, accepted by some, and ignored by other researchers. In Old English slang-o, n was lost after the vowel (this part of the reconstruction and the other phonetic details are secure), and what remained of the word was later changed to slow– and occasionally to slay– under the influence of folk etymology. Thus, “snake-snake.”

Greek aióllo and Germanic ǣlaz “eel”This comparison, offered in a comment on the previous post, looks tempting. The Greek verb meant “to turn over the fire; to change color (to become variegated),” but the basic sense was “to change,” as is obvious from the related adjective aiólos “nimble; many-colored; changeable.” The word is known to many from the name of the god of the wind, Latinized as Aeolus. Rather probably, the name did mean “changeable.” Odysseus met this god and received a bag with all the winds in it. Think also of the Aeolian harp. It is up to Classical philologists to explore this parallel in detail.

Conversely, I can say nothing new about the origin of the idiom slippery as an eel. Eels do have a smooth skin, and their ability to writhe and “slip away” is famous. No doubt, the phrase was coined by those who knew eels’ habits well. As indicated quite correctly in the letter, the English simile goes back to the fifteenth century. Perhaps something is known about the consumption of eels in Britain at that time. I found no references to this simile or its lookalikes elsewhere in my database.

The fish name carp and some Germanic words for “basket”Carp (in English, it is a French loanword) goes back to Latin carpa. All its Germanic cognates have the same source. In the sixth century, the carp was known as a fish of the Danube, and its name may be Germanic, but nothing is known about its origin, though similar-sounding fish names in Sanskrit,, Lithuanian, and Greek exist. A migratory substrate word? The question was whether carp has anything to do with words like German Korb, Dutch korf, and Swedish/Norwegian korg “basket.” The answer is “no.” Incidentally, most words for “basket” are of obscure origin. The immediate source of the Germanic words is Latin corbis. Its etymology also remains a matter of speculation.

Herrings and sieves in ScandinaviaThe oldest recorded Scandinavian name for “herring” is Old Icelandic síl-d. Also, síl “sand eel” is known (we seem to be unable to part with eels today!). No doubt, the two words are related, but the literature I have read on the origin of síl resolves itself into rather uninspiring guesswork. The word was and is widely known outside Scandinavia, and this is all I can say about it.

No, these herrings are not meant for a sieve.

No, these herrings are not meant for a sieve. Image by Jacob Bøtter, CC by 2.0, via Flickr.

For “sieve” we have Danish sold, Norwegian såld, and Old Icelandic sáld. The final consonant (d) in sáld and síld looks like a relic of an ancient suffix, but there is no way of demonstrating that the roots sál– and síl– are related. Besides, síl is a fish name of undiscovered origin and thus cannot throw light on an equally opaque word. Fish names are often hard to etymologize. They tend to travel from one speaking community to another, and what looks like a Germanic word my be of Latin origin and vice versa, or the source may be a third (unknown) language.

CleanersA reader asked me why the French use the word nettoyeur for “cleaner” and the Spanish prefer limpiador. I don’t think there is an answer to this question. Both words are transparent and were coined independent of each other. Incidentally, English cleaner is not based on German klein “small” (as implied in the letter). Its root is English clean.

Featured image: “Sigurd and Fafnir” by Hermann Hendrich. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 4, 2025

The meteoric rise of Louis Armstrong [playlist]

The meteoric rise of Louis Armstrong [playlist]

In the five years between his first recording session as a sideman with King Oliver in April 1923 to his final date as a leader in Chicago in December 1928, Louis Armstrong changed the sound of American popular music, with both his trumpet and with his voice. He perfected the art of the improvised solo, expanded the range of the trumpet, popularized scat singing, rewrote the rules of pop singing, and perhaps most importantly, infused everything he did with the irresistible feeling of swing. In surveying the landscape on Spotify alone, one can find 269 sides with Armstrong from this period, totaling 13 hours and 30 minutes of music. Trying to boil that output down to 12 representative tracks is not an easy task, but hopefully this playlist conveys a taste of just what made Armstrong so special in this decade—and every decade.

1. “Tears” – King Oliver’s Jazz Band – Chicago, 5-15 October 1923Armstrong moved to New York City in the fall of 1924 to join one of the top Black dance bands in the nation, Fletcher Henderson and His Orchestra. Though members of Henderson’s group initially looked down on Armstrong’s southern fried disposition, that all changed when they heard him play. “Shanghai Shuffle” is a perfect example of what Armstrong brought to New York, taking a short, explosive solo in the middle of a dated, quasi-exotic arrangement, much like a burst of sunshine emerging from the clouds. Henderson reedman Don Redman was paying attention and began transforming the orchestra into a pioneering swing band–using Armstrong’s improvisations as an inspiration.

2. “Shanghai Shuffle” – Fletcher Henderson and His Orchestra – New York City, 10-13 October 1924Armstrong moved to New York City in the fall of 1924 to join one of the top Black dance bands in the nation, Fletcher Henderson and His Orchestra. Though members of Henderson’s group initially looked down on Armstrong’s southern fried disposition, that all changed when they heard him play. “Shanghai Shuffle” is a perfect example of what Armstrong brought to New York, taking a short, explosive solo in the middle of a dated, quasi-exotic arrangement, much like a burst of sunshine emerging from the clouds. Henderson reedman Don Redman was paying attention and began transforming the orchestra into a pioneering swing band–using Armstrong’s improvisations as an inspiration.

3. “St. Louis Blues” – Bessie Smith – New York City, 14 January 1925Armstrong became quite adept at blowing obligatos behind various blues singers during his time in New York, climaxing with this iconic meeting with “The Empress of the Blues,” Bessie Smith. Calling what Armstrong does on “St. Louis Blues” an “obligato” is rather limiting; it’s really a duet, as his responses to Smith’s powerful vocal are note perfect, establishing the rules of how to properly accompany a singer, rules that are still adhered to this day.

4. “Gut Bucket Blues” – Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five – Chicago, 12 November 1925In the fall of 1925, Armstrong moved back to Chicago, where OKeh Records finally gave him the opportunity to make records under his own name. In addition to Lil on piano, Armstrong hired three of his elders from New Orleans and formed a studio group, the Hot Five. After feeling stifled by Oliver and Henderson, Armstrong unleashed his infectious personality on the very first Hot Five side to be released, “Gut Bucket Blues,” confidently introducing the members of the band and establishing the template for what would become one of the most influential series of recordings in the history of American popular music.

5. “Heebie Jeebies” – Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five – Chicago, 26 February 1926OKeh’s E. A. Fearn encouraged Armstrong to sing on “Heebie Jeebies,” which was originally conceived as an instrumental by Boyd Atkins. Armstrong wrote down some rudimentary lines but during the actual recording of the tune, he claimed to have dropped the lyric sheet. Instead of spoiling the take, Armstrong began using his voice like an instrument, something he did back when he was a kid singing on the streets of New Orleans, singing nonsense syllables, but phrasing them like one of his swinging trumpet solos. This type of singing didn’t have a name but Fearn began marketing it as “skat” and the result was Armstrong’s first legitimate hit record.

6. “Cornet Chop Suey” – Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five – Chicago, 26 February 1926After already impacting the course of pop singing with “Heebie Jeebies,” Armstrong next turned his attention towards writing the rules on how to take an effective solo with “Cornet Chop Suey,” recorded on the same day. This is Armstrong’s show from start to finish, opening with a dazzling unaccompanied intro before moving into the forward-looking melody, composed by Armstrong two years earlier. But it was the stop-time interlude in the middle of the record that made trumpeters, trombonists, pianists, and other instrumentalists around the country sit up and take notes on how to create a memorable solo.

7. “Stomp Off, Let’s Go” – Erskine Tate’s Vendome Orchestra – Chicago, 28 May 1926The Hot Five, as important as they are, was only a studio group and rarely performed in public. During this period, Armstrong performed nightly with Erskine Tate’s Vendome Orchestra, where he accompanied silent movies, did comedy routines, and was featured on classical numbers like the “Intermezzo” from Cavalleria Rusticana. Armstrong’s only recording session with Tate resulted in one of the decade’s hottest records, “Stomp Off, Let’s Go,” which showcases the piano work of Teddy Weatherford, in addition to offering a taste of Armstrong’s flashy style of the time.

8. “Big Butter and Egg Man” – Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five – Chicago, 16 November 1926Armstrong doubled for much of 1926, working with Erskine Tate at the Vendome Theater before heading to the Sunset Cafe, where he was featured trumpeter in Carroll Dickerson’s Orchestra. “Big Butter and Egg Man” was a Sunset Cafe specialty before being adapted by the Hot Five in what became known as a legendary recording. Armstrong’s solo is a marvel of storytelling, but he also gets to display his good humor and showmanship in his vocal spot, hallmarks of his later career that were already firmly in place in the 1920s.

9. “Hotter Than That” – Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five – Chicago, 13 December 1927By the end 1927, Armstrong was beginning to outpace the original members of the Hot Five. The records began featuring more and more of his solos, which were of a higher caliber than the work of his New Orleans elders. Armstrong needed new musicians to inspire him, such as guitar pioneer Lonnie Johnson, who made his presence felt on “Hotter Than That.” Armstrong solos over the rhythm section for a full chorus at the start, eschewing the group’s usual New Orleans polyphonic style, and embarks on a scat episode that is positively thrilling, his mastery of rhythm on full display. Towards the end, he even uncorks a two-note riff that would become a staple during the big band era. As a farewell to the original Hot Five, it doesn’t get any hotter.

10. “West End Blues” – Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five – Chicago, 28 June 1928In June 1928, Armstrong returned to the studio with a retooled Hot Five, made up of members of Carroll Dickerson’s Orchestra and the man known as the “Father of Modern Jazz Piano,” Earl “Fatha” Hines. On King Oliver’s composition “West End Blues,” Armstrong opened with an unaccompanied trumpet cadenza in which he utilized everything he had learned about the instrument since first picking it up 15 years earlier. The entire record, from the cadenza to Armstrong’s mournful scatting to Hines’s dazzling piano solo, is simply a masterpiece of twentieth century recorded music, one that is still being studied in the twenty-first (a #westendblueschallenge was all the rage on social media a few years ago).

11. “Beau Koo Jack” – Louis Armstrong and His Savoy Ballroom Five – Chicago, 5 December 1928By December 1928, OKeh Records realized the old trumpet-trombone-clarinet-banjo-piano sound was a thing of the past and began pushing Armstrong to record with slightly larger ensembles. On “Beau Koo Jack,” the addition of Don Redman’s alto saxophone and an arrangement by the song’s composer, Alex Hill, completely modernized the sound of Armstrong’s “Savoy Ballroom Five,” paving the way towards the Swing Era of the next decade. Armstrong shines in his setting, showing off every tool in his toolbox in a solo that still has the ability to astound in 2025.

12. “Tight Like This” – Chicago, 12 December 1928The final song recorded at Armstrong’s final Chicago session before relocating to New York, “Tight Like This” can be viewed as a summary of Armstrong’s entire life up to this point. There’s comedy in the discussion about whether or not “it” is “tight like that”; there’s a minor-key mood that allows Armstrong to tap into the music he learned from the Jewish Karnofsky family; and there’s hints of the “Spanish tinge” as Jelly Roll Morton called it, incorporating a different, but no less important, flavor from his hometown. But most importantly, Armstrong’s three-chorus solo tells a story, taking its time and building to a roof-shaking climax that would be the blueprint for future soloists ranging from B. B. King to Jimi Hendrix to Eddie Van Halen (and those are just the guitarists). Full pop star stardom awaited Armstrong in New York in 1929 but the records he made in the 1920s established him once and for all as one of the most influential musicians of the twentieth century—and beyond.

Featured Image From “Stomp Off, Let’s Go” Figure 27.1 1926 publicity photo of the original Hot Five. From left to right: Johnny Dodds, Louis Armstrong, Johnny St. Cyr, Kid Ory, Lillian Hardin Armstrong. Credit: Courtesy of the Louis Armstrong House Museum. Photo restoration by Nick Dellow.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 3, 2025

The best of Health Affairs Scholar 2024

The best of Health Affairs Scholar 2024

As we welcome 2025, we reflect on the milestones and achievements that shaped Health Affairs Scholar in 2024. Among the highlights, we introduced our first Calls for Papers, focusing on the critical topics of: Global Aging, Intersections of Social Policies and Health, and Policy Options for the 340B Discount Program. These ongoing series continue to invite submissions, fostering meaningful discourse on pressing policy issues.

The journal also launched its inaugural Featured Paper Series, Health Workforce Issues and Challenges in the Post-Pandemic Era, with contributions from each of the nine federally funded Health Workforce Research Centers. Building on this momentum, three additional Featured Paper Series are set to publish in 2025, each exploring distinct, timely topics and supported by different sponsoring organizations. The papers below kick-off two of these series, with the introduction to the third series on Emergency Room Care coming soon.

Health And Political Economy: Building A New Common Sense In The United States by Victor Roy, Darrick Hamilton, and Dave ChokshiEvidence To Inform Biopharmaceutical Policy: Call For Research On The Impact Of Public Policies On Investment In Drug Development by Sandra Barbosu, Kirsten Axelsen, and Stephen EzellIn addition to these exciting new initiatives, we’re pleased to share that the journal is now indexed in the Web of Science, as well as PubMed Central, The Directory of Open Access Journals, and Google Scholar.

As we look back on a successful year, we also want to highlight the top ten most read papers published in 2024. These papers reflect some of the timeliest issues of 2024, including contraceptive access and use in the post-Dobbs era, mapping pharmacy deserts across the country, prior authorization burdens and solutions, and much more.

1. Has the Fall of Roe Changed Contraceptive Access and Use? New Research from Four US States Offers Critical Insights by Megan L Kavanaugh and Amy Friedrich-Karnik

In this brief report, Megan Kavanaugh and Amy Friedrich-Karnik examine the broad impact the overturning of Roe v. Wade has had on contraceptive access and use. The report highlights decreased access to quality contraceptive care across four states and emphasizes the need for evidence-based policies and programs to better support people’s contraceptive needs in the post-Dobbs era.

2. The Evolution and Scope of Medicaid Section 1115 demonstrations to address nutrition: a US survey by Erika Hanson and others

Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration waivers offer states the opportunity to pilot coverage for nutrition-based services to address health disparities. Erika Hanson and coauthors provide insight into the evolution and current landscape of food-based initiatives supported by these demonstrations across 19 states.

3. Return On Investments In Social Determinants Of Health Interventions: What Is The Evidence? by Sayeh Nikpay, Zhanji Zhang, Pinar Karaca-Mandic

Sayeh Nikpay and coauthors quantify the return on investment for interventions focused on combating food and housing insecurity, emphasizing the role these estimates play in encouraging future investment by health plans and other private actors in the health care space.

4. Why Does The Cost Of Employer-Sponsored Coverage Keep Rising? Salpy Kanimian, Vivian Ho

Salpy Kanimian and Vivian Ho explore the rising gap between health insurance costs and wages, highlighting the role hospitals play in driving premiums. Between 2006 and 2023, hospital price index rose faster than insurance premiums, and hospitals consistently maintained high profit margins than insurers.

5. Life Cycle Of Private Equity Investments In Physician Practices: An Overview Of Private Equity Exits by Yashaswini Singh, Megha Reddy, Jane M Zhu

Yashaswini Singh and colleagues explore the often rapid turnover of private equity investments in physician practices. Their analysis reveals that private equity firms increase affiliated practices by 595% on average in just three years, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability of care and workforce investments.

6. Locations and Characteristics of Pharmacy Deserts in the United States: A Geospatial Study by Rachel Wittenauer and coauthors

Rachel Wittenauer and coauthors use pharmacy address data and Census Bureau surveys to map pharmacy deserts across the United States. Their findings show that 4.7% of Americans in both rural and urban communities live in these deserts, demonstrating an urgent need to improve access to pharmaceutical services.

7. Perceptions Of Prior Authorization Burdens And Solutions by Nikhil R Sahni and coauthors

Nikhil R. Sahni and colleagues examine the perceived challenges related to prior authorization processes and the barriers that impede the adoption of automated solutions including the use of artificial intelligence.

8. Balancing Innovation And Affordability In Anti-Obesity Medications: The Role Of An Alternative Weight-Maintenance Program by David D Kim, Jennifer H Hwang, Mark Fendrick

Anti-obesity medications have garnered significant attention for their effectiveness, but their high price poses a major challenge to accessibility. Using a policy simulation model, David Kim, Jennifer Hwang, and Mark Fendrick evaluate the impact of an economical weight-maintenance program after weight loss plateau as an alternative to continuous medication use.

9. Infant Mortality In Ghana: Investing In Health Care Infrastructure And Systems by Danielle Poulin and coauthors

A policy inquiry by Danielle Poulin and coauthors provides recommendations for policymakers to address the persistently high rates of infant and neonatal mortality in Ghana, despite efforts to improve financial accessibility to care. The authors suggest that a systems approach is needed to minimize barriers to pre- and post-natal care, including investment in medical facility and transportation infrastructure, increased workforce development, and improvement in claims reimbursement.

10. Physicians Working With Physician Assistants And Nurse Practitioners: Perceived Effects On Clinical Practice by Xiaochu Hu and coauthors

A national survey of US physicians reveals that most view working with physician assistants and nurse practitioners as positively impacting their clinical practice. Physicians in medical schools and with higher incomes were particularly likely to report benefits, while those in specialties with higher women’s representation had lower ratings.

Featured image by Viridiana Rivera via Pexels.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 2, 2025

The unknown A Complete Unknown

The unknown A Complete Unknown

Folk music is still and always with us. It is in the tap of the hammer to the music on the radio or, in older days, to the workers’ own singing. It is the rhythmic push of the cabinetmaker’s saw, the scan across the checkout station to the beat of songs inside the checker’s head. “Folk music is a river, always flowing, steady and heedless. It has always been the underground stream of American musical culture: the rhythms of daily life.”

In the Academy Award-nominated film A Complete Unknown, Bob Dylan stalks off the stage at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival as the crowd boos. The filmmakers present this as a momentous turn for American culture, when rock’n’roll (factually, folk-rock and blues) trounces the feel-good, all-together-now world of American folk music. The significance of this event, which climaxes the film, is far more subtle. And the private reactions from Pete Seeger, whom Dylan once revered, have yet to be told.

The folk music revival of the 1950s and 60s emerged from eighteenth-century religious revivals, emphasizing individual honesty and spirituality, such as the Great Awakening. In the twentieth century, the first folk music revival was led by researchers and collectors, as in Germany, inspired by nineteenth-century Romantics. Preservationists of stories, jokes, or tunes visited libraries; tromped out in the hills and hollers of Appalachia, down the damp and dusty byways to find a local storyteller or that “fiddler in the woods.”

Out of these efforts came a cultural preservation movement pioneered by John Lomax, a collector of cowboy ballads, and particularly by his son, Alan Lomax. When Alan met Pete Seeger, son of musicologist Charles Seeger (who was the first to teach a course in folk music at an American university), they shifted that movement from cultural antiquarianism to activism, to reflect their desire to use songs for social equality. This fusion of folk music and social justice is what the filmmakers characterize as dissolving in the chaos of “Dylan goes electric” in July 1965. At this point, many of what could be called his followers were disaffected by his apparent turn from liberal politics and from traditional songs in his compositions.

Though depiction of the scene in Greenwich Village is accurate, the film misreads both traditional music and its profound influence on all of Dylan’s tunes and lyrics. Anyone listening to his adaptation of “900 Miles,” or how he turned “The Twa Sisters” (tenth in the collection of traditional ballads of Francis J. Child) into a deeply personal tale, or the traditional ballads and songs on his first album, Bob Dylan, (dismissed here as “other people’s songs”) can only marvel at his genius of reworking tradition. This corresponded to the purpose of the Newport Folk Festival which, instead of a parade of “stars,” devoted most of its stages to songs originating hundreds of years prior.

Dylan, however, was far more than a folk purist. Many do not realize that his first single had a rock band playing behind a rockabilly cut (“Mixed Up Confusion” in 1962), or that soon after that, he released a country-rock tune, “Rocks and Gravel,” also with a band. Dylan didn’t “go electric.” He’d been there for years. The film also disregards the aegis of that festival, directly traceable to the Romantic belief in the music of down-home, everyday folks and its uncommercial roots. The Newport board included Pete Seeger (and his wife and de facto manager, Toshi Ohta), and it had long allowed electrified instruments, though this was usually reserved for traditional blues musicians who had always played that way.

The question at the heart of the film then becomes one of Dylan’s motivation at provoking the citadel of American folk music: was he interested only in headlines and establishing himself commercially? Was he serious about singing out for social justice? (No careful listener to “The Death of Hattie Carol” or “Masters of War” can dispute this.)

Pete Seeger, photo by David K. Dunaway used with permission.

Pete Seeger, photo by David K. Dunaway used with permission.In the film, viewers watch Dylan develop his chops—learning to work a mic, provoking interviewers, handling and at times dismissing baby boomers who sought him out as an oracle, singing alongside Seeger and Phil Ochs against injustice. We see him develop his performative, rebellious persona: mercurial, sullen, snarly, confrontational. Alongside him, we see his mentor Pete Seeger, here presented as benign but authentic, a citybilly singing hillbilly songs to syncretize them for urban audiences. Seeger was the Pied Piper of the folk revival introducing folk music, in one concert, to Dave Guard (Kingston Trio) and Joan Baez (for years Dylan’s partner to folk music). Seeger’s goal diverged from the commercializing instincts of Albert Grossman, Dylan’s manager, instead being rooted in the inherently democratic nature of folksong. And this is where A Complete Unknown stumbles. It captures the dress of folkies (Beat meets Hip) and their clubs: the Café Wha, Folk City, the Gaslight; but it fails to present folksongs as carriers of an important, centuries-long process. It presents Dylan as if he was unknowing and uncaring of folksong and the democratic, ground-up socialism implicit in them.

Finally, we arrive at the dramatic climax, with Dylan in leather jacket and boots (in contrast to Seeger’s flannel shirts) daring the folkies to accept him in his new coat of many colors. As usual, the search for truth through historical fiction requires fact separated from context and characters isolated from their motivation.

In this case, we must examine two issues with Dylan’s performance: a sound system unaccustomed to bands; and the distinctly non-folk, non-protest lyrics he sang. From the first booming chords of “Like a Rolling Stone,” conveniently released the week before this provocation, we hear the boos; objects tumble toward the stage. (Though the film presents audience reactions as mixed, in recordings derision clearly outnumbers cheers.) Seeger implores the sound mixers to turn down the volume; he wants the audience to hear Dylan clearly. “I just want to hear the words,” he kept repeating. Nevertheless, these were drowned out either because of the mix or because the sound system was never set up to handle instrumentation this loud. Add to this Dylan’s abandonment of civil rights and peace songs in favor of angry pop, and you have an audience and its leaders betrayed. That much is true. To many listening, Dylan should no more have a pop song on AM radio than Pete Seeger should replace Johnny Cash on late-night television.

There exist more published interpretations of this performance than of any other concert. (I’ve written mine in a biography of Seeger, How Can I Keep from Singing?) Some accused Dylan of prostituting himself for commercial success; or “I come to hear Dylan, not a pop group,” or, ineloquently: “Play folk music: You stink.” Dylan closed by returning to the stage with an acoustic guitar in place of his shiny Fender and played the prophetic, “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” He charged off the stage with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, passing Toshi, who at this juncture is allowed one of her disgracefully few comments in the film: “Bob!”

In private, Seeger was far more upset by Dylan rejecting traditional song than he was about the sound system massacring the lyrics: “Last week at Newport, I ran to cover my ears and eyes because I could not bear either the screaming of the crowd nor some of the most destructive music this side of hell,” he wrote in a letter to himself.In this never-published critique, he referred to Dylan’s new career as a cancer eating away at the musician he had introduced to the world. Later, he would return to this moment repeatedly, trying to understand what had gone wrong.

The last word about his disassociation with folk music—though in later albums he repeatedly recorded traditional songs—comes from Dylan himself at the close of his autobiography, Chronicles: “The folk music scene had been like a paradise that I had to leave, like Adam had to leave the garden. It was just too perfect.”

Featured image by Dave Gahr, used with permission.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

February 1, 2025

Voices of change for Black History Month [reading list]

Voices of change for Black History Month [reading list]

In honor of Black History Month, we celebrate the powerful voices that have shaped history and continue to inspire change in America and around the world. This reading list features eight books that amplify the diverse experiences and contributions of Black individuals. Eight unique stories of resistance, perseverance, empowerment, and transformation that deserve their place in the American narrative. From the riveting biographies of iconic musicians to a radical exploration of Black Twitter, and the final untold story of the civil rights movement, these books offer deep insights and celebrate the enduring legacy of Black excellence and resilience. Let these voices of change inspire you.

1. We Tried to Tell Y’All by Meredith D. Clark

1. We Tried to Tell Y’All by Meredith D. ClarkBlack Twitter carved out a vital space for commentary on Black life in America, shaping over a decade of discourse and giving voice to hundreds of thousands of Americans who felt shut out and misrepresented by the mainstream press. We Tried to Tell Y’All by Meredith D. Clark—a former journalist NPR calls “the go-to person about Black Twitter”—explains how Black social media users subverted the digital divide to confront centuries of erasure, omission, and mischaracterization of Black life in the media.

2. The Power of Black Excellence by Deondra Rose

2. The Power of Black Excellence by Deondra RoseFrom their founding, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) educated as many as 90% of Black college students in the United States. Although many are aware of the significance of HBCUs in expanding Black Americans’ educational opportunities, much less attention has been paid to the vital role that they have played in enhancing American democracy. Deondra Rose provides a powerful and revealing history of how HBCUs have been essential for empowering Black citizens in the ongoing fight for democracy in the United States.

3. Soon & Very Soon by Robert F. Darden and Stephen M. Newby

3. Soon & Very Soon by Robert F. Darden and Stephen M. NewbyThere are few voices in twentieth century gospel that are more recognizable or influential than Andrea Crouch. In the very first biography of the legendary artist, authors Robert Darden and Stephen Newby celebrate the countless ways that Crouch changed the course of gospel and popular music; not least among them was Crouch’s progressive pursuit to address the sociopolitical issues of his time, including AIDS, prejudice, abuse, housing insecurity, and addiction. The book is brought to life through interviews with his collaborators, friends, and family.

4. Bloody Tuesday by John M. Giggie

4. Bloody Tuesday by John M. GiggieThe people of Tuscaloosa have been searching for decades for someone to tell their story. On Tuesday, 9 June 1964, police attacked more than 600 Black men, women, and children inside First African Baptist Church, where Reverend Martin Luther King had launched the Tuscaloosa campaign for integration three months earlier. As the group gathered to march, they faced over seventy law enforcement officers and hundreds more deputized white citizens and Klansmen eager to end their protests for good. Police smashed the historic church’s stained-glass windows with water hoses and fired rounds of tear gas inside. As demonstrators streamed from the church, many choking and soaked, the white mob beat them with nightsticks, cattle prods, and axe handles, arrested nearly a hundred, and sent over thirty to the hospital. Drawing on over 150 unpublished interviews, Bloody Tuesday tells one of the last great untold stories of the civil rights movement.

5. James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” by Tom Jenks

5. James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” by Tom JenksTom Jenks’s reading of James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” follows a scene-by-scene, sometimes line-by-line, discussion of the pattern by which Baldwin indelibly writes “Sonny’s Blues” into the consciousness of readers. Drawing on Baldwin’s book-length essay The Fire Next Time, which Baldwin published six years after “Sonny’s Blues,” Jenks offers insight on some of the sources in Baldwin’s life and the logic and passion by which life may be meaningfully transformed into art.

6. Stomp Off, Let’s Go by Ricky Riccardi

6. Stomp Off, Let’s Go by Ricky RiccardiGrammy winning historian Ricky Riccardi looks at the early years of Louis Armstrong’s life to tell the story of the iconic trumpeter’s meteoric rise to fame. While this period of Armstrong’s life is perhaps more familiar than others, Riccardi enriches the existing narratives with recently unearthed archival materials, including a rare draft of pianist, composer, and Armstrong’s second wife Lillian “Lil” Hardin Armstrong’s autobiography.

7. COMBEE by Edda L. Fields-Black

7. COMBEE by Edda L. Fields-BlackEdda Fields-Black is a direct descendent of one of the hundreds of formerly enslaved men who liberated themselves and joined the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers to fight in the Combahee River Raid along with Harriet Tubman, and in COMBEE she tells the story of her own ancestors. COMBEE is the first detailed account of one of the most dramatic episodes of the Civil War and the role Harriet Tubman played in it. The New Yorker and Bloomberg named the book one of their highly recommended books for 2024.

8. Mutiny on the Black Prince by James H. Sweet

8. Mutiny on the Black Prince by James H. SweetIn 1768, the British slave ship Black Prince, departed the port of Bristol, bound for West Africa. It never arrived. Before reaching Old Calabar, the crew mutinied, murdering the captain and his officers. The mutineers renamed the ship Liberty, elected new officers, and set out for Brazil. By the time the ship arrived there, the crew had disintegrated into a violent mob and fired into the port city. After the Black Prince wrecked off the coast of Hispaniola, the rebels fled to outposts around the Atlantic world. An eight-year manhunt ensued. Mutiny on the Black Prince tells the dramatic story of the events onboard the ship as well as the way that British slavery shaped the industrializing Atlantic economy of the eighteenth century.

Featured image created in Canva; photograph by Ryandeberardinsisphotos.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

January 30, 2025

Librarian reflections: a retrospective on 2024

Librarian reflections: a retrospective on 2024

At OUP, we’re eager to foster discussion and reflection within the library community. So we took the opportunity to ask Eleanor Thomas, Acquisitions Coordinator for the University of Adelaide Library, to share her reflections on and experiences of the library sector over the past year, and her impressions of what the new year may bring.

There has been a lot of debate about the place of AI in academia. How has the progression of AI affected your library or role thus far?The library has been very conscious of the need to support students with AI literacy. We recently launched the Artificial Intelligence Literacy Framework (AILF), a collaboration between the library and academic and professional staff of the University. There is a common perception that you can do all sorts of clever things using AI and there aren’t any rules, but that is challenging in higher education. The AILF aims to assist with the development of essential skills for navigating this space. It describes competencies and provides examples for possible training content.

There has been an increase in the number of subscription resources offering add-on pricing to include AI functionality. It’s important to provide relevant resources in support of teaching and research but budgets are already tight, so managing the additional fee is difficult. It’s a complex space, with questions around quality and the added value provided, and it is one we’re only beginning to grapple with.

Describe an initiative your library has taken that you’re proud of.We’ve made some significant changes to our physical spaces, with a massive revamp of multiple floors of the library and the creation of our wonderful new cultural space, Tirkanthi Yangadlitya or ‘Learning for the future’. This new space focuses on learning, beauty, empowerment, and the celebration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and peoples. With nature-inspired furnishings and colour, it is a peaceful and reflective place. The Yarning Circle is a wonderful feature, but I’m always struck by the beauty and craftmanship of the beautifully hand-woven light shades made by Indigenous communities. The Yaitya Ngutupira ‘About Aboriginal knowledge’ collection is conveniently located nearby.

Image courtesy of the Barr Smith Library.

Image courtesy of the Barr Smith Library.Some parts of the library were looking so tired but now it looks fabulous! There were periods during the year when the walls shook, the ground heaved, and you really did wonder whether your feet would ever stop vibrating but the results have been worth every moment. We now have more accessible shelving, brighter spaces, new furniture, sleep pods, new carpet, and better wayfinding.

2024 was the University of Adelaide’s 150th birthday and the Barr Smith Library is looking better than ever.

What have you found the most challenging in your role over the past year?Time management and prioritization have been my greatest challenges! We’re spending a lot of time carefully planning for the merger of the University of Adelaide and University of South Australia in 2026. There are many factors to consider, so good planning is essential. At the same time, it is vital that we maintain our focus on the needs of our current students to ensure that they have the best possible experience here. There have also been significant positives as well, because I’m getting to work closely with former colleagues from my previous time at the University of South Australia. Experiencing challenges like these with a sense of fellowship has been very positive.

Looking ahead, can you name three things you are either excited about or daunted by for your library this year?2025 will be the final year of the University of Adelaide before we join with the University of South Australia. I’ve loved being part of the University of Adelaide, and I do feel a sense of loss for the things I have now which will no longer be. I have a great team here and I value the times we have together. Things will begin to change this year and I feel a little daunted by that.Excitingly though, 2025 will continue the job of finding our way to the new us. I’ve worked at both foundational institutions, and they are great in themselves, so surely together we will become even better. Increasingly we’ll get to meet our future colleagues and start working everything out. I’m looking forward to renewing old friendships and building new connections; it is a rare opportunity to be part of a university merger of this kind.I can’t quite believe I’m saying it, but it is exciting to start creating library workflows and processes from scratch! All librarians have been in the difficult position of trying to cram a new process into an existing situation with limitations. We make it work, and we make it the best it can be, but we’ve all had moments of wishing we could start from the ground up. As part of the future Adelaide University, we will have that opportunity.Featured image by Oporanhho via Unsplash

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

January 29, 2025

Slippery as an eel, merry as a grig

Slippery as an eel, merry as a grig

My post on Yule redux (January 22, 2025) engendered two responses. One, published as a comment, states that my essays give the correspondent a lot of joy, though he does not understand much of what I say. I never thought that my writings sound like some sort of glossolalia. He also referred to me as he/she. I am a simple, unhyphenated soul, a mere he. The other was a private letter. It cited Tolkien’s Dark Elf Eöl, that is, exactly the form Alexander Hislop used as the etymon of Yule. I too noticed this amazing coincidence and even did some research, if you can call it that: I looked through a list of Old Norse mythological names in the hope of finding something similar but discovered nothing. Perhaps some of our readers know the source of Tolkien’s inspiration. He could not have produced such a strange name (with ö in the middle!) out of thin air, but how likely is it that he read Hislop’s book? Any comment will be welcome.

Today’s post is about the word eel and the eel’s kin. Specialists will find very little or nothing new in it. However, others may not realize that eel is one of the most obscure fish names in our vocabulary. Though it has been discussed multiple times, current dictionaries say only: “Ultimate origin unknown.” We know the word is old. Predictably, it does not occur in the text of the Gothic Gospel (a fourth-century text), but elsewhere in Germanic, its cognates turned up quite early, and the root of the protoform must have been āl-. It is the etymology of this āl– that remains undiscovered. (Note that ā and á designate “long a,” that is, a vowel, more or less like a in Modern English spa.)

Incidentally, as the thesaurus provided by the OED online shows, even in English, this fish has been known under several names. Some of them, for example, snig and the long-forgotten fausen, are obscure. Yet snig, with its initial sn-, may be sound-symbolic, suggestive of the fish’s writhing movement (compare sneak!). Grig rhymes with snig, and its sound-symbolic origin is, likewise, not improbable. Fausen looks foreign. In Middle English, the word meant “dwarf”! Later, it turned up with the sense “short-legged hen” and “cricket” (one is almost tempted to write gricket). Grig “young eel” surfaced only in the seventeenth century, later than prig, with which it rhymes. During its long life in English, prig could designate anyone from “thief” to “an obnoxious snob,” but to an etymologist grig and prig belong together. It almost looks as if the sound complexes prig and grig were up for grabs, and speakers endowed them with any meaning they wanted.

Why is one merry as a grig? Grig, as just noted, is, among other things, a synonym for “cricket.” One can also be as merry as a pismire (pismire “ant”). In the past, merry meant “lively, nimble; vivacious,” and we might perhaps add “antsy.” Despite the common misconception, Greek has nothing to do with grig. As we can see, a word for “eel” does not have to refer only to the well-known fish. But eel, from āl-, is neither sound-imitative nor sound symbolic. It has always meant only what it does in the modern Germanic languages and needs a respectable etymology, that is, secure cognates and a solid ancient root. Sadly, it has neither, and that is why we are left with several ingenious hypotheses but no solution.

An awl winding its way through the surface like an eel?

An awl winding its way through the surface like an eel? Image by Willi Heidelbach from Pixabay.

Even though eel has always referred to the fish, Old Icelandic áll meant not only “eel” but also “a sprout,” “a deep narrow river or sea channel; gutter,” and “a narrow colored stripe along the back of a horse.” In at least one compound, áll seems to be a cognate of English awl. Even though no certainty exists that we are dealing with several senses of one word, rather than with several homonyms, we notice that all the words, glossed above, designate long or elongated objects. To repeat: are they chance homonyms of the fish name or various senses of the same word? Opinions on this score differ. In the past, the most knowledgeable scholars believed that the fish name and “stripe” are indeed two senses of the same word and that eels were called eels because they look like stripes. But nowhere outside Scandinavian do we find eel meaning “stripe.” Therefore, this attractive etymology, which seems to have been proposed as early as 1909, is, most probably, wrong.

When dealing with old words, historical linguists usually try to find some meaningful root. One such candidate was the verb eat. The eel in that reconstruction emerged as the provider of edible food, because “eater” fits the context even worse. Where were eels the main source of sustenance? This hypothesis is stillborn. Old Irish alam “fish roe” and a similar-sounding dialectal Norwegian word for “fish mucus” or something similar have also been pressed into service as possibly related to eel. Another blank shot. Yet one word has survived as a possible cognate of eel: it is English awl (which has similar cognates elsewhere in Germanic). Unfortunately, awl itself is a noun of undiscovered origin, and though several sources cite hesitatingly eel and awl in one breath, one mystery can give little help to another.

Most researchers have written off eel as a substrate word. The term substrate turns up with some regularity in this blog. It refers to the language of the native population that had occupied the land before the present-day settlers displaced it. The displacement may even be the result of a more or less peaceful amalgamation, but more often it follows conquest. For example, nothing is known about the language of the Picts. Perhaps some hopelessly opaque English words are Pictish, and that is why we cannot solve their etymology. One should be cautious in referring to a substrate, because such references answer no questions: they refer something unknown to another unknown factor. Eel has been repeatedly called a substrate word, that is, a word from an undiscovered language.

Illuyanka, a possible relative of our innocuous eel.

Illuyanka, a possible relative of our innocuous eel. Image from Georges Jansoone (JoJan), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Yet eel may be an Indo-European word after all! The boldest attempt to solve the riddle goes back to a series of essays by Dr. Joshua Katz, written in the 1990s. There is a Hittite myth about the storm demon Illuyanka, or Illyuyankaš. Ankaš is “snake,” and illuya is, according to Katz, a cognate of eel. I’ll skip the details and only say that the compound ends up meaning “snake-snake.” Katz missed a point in his favor. Snake-snake is a typical tautological compound, that is, a compound, both of whose elements meant the same. Indo-European is full of such words. (See my post of June 21, 2006.) They are often place names and words dealing with the landscape (when we decipher them, we end up with sea-sea, mountain-mountain, and so forth). But there are more. Modern English pathway and sledgehammer belong to this group. Also, English slowworm seems to have meant “snake-snake,” a close counterpart of the Hittite monster. The latest dictionaries ignore Katz’s etymology, but I think he was right. The discovery of a probable Indo-European cognate of eel probably buries the idea of a substrate origin of this fish name, but we still do not know what associations the ancient sound complex evoked. “Long and winding?” What is so special in the sound group āl? Alas, it is not sound-symbolic. In any case, a slowworm is not unlike an eel, a fact that bolsters up Katz’s etymology of eel and mine of slowworm.

There is more in common between a slowworm and an eel than meets the eye.

There is more in common between a slowworm and an eel than meets the eye. Left: Slow Worm by Bernt Rostad via Flickr; CC BY 2.0. Right: PublicDomainPictures via Pixabay.

Featured image by Krüger via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

January 27, 2025

Meditations in purple

Children may have less height, vocabulary, and power than adults do. But children’s books are not a lesser art form.

Consider Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon. At first glance, the book looks self-explanatory. What more can be said about a boy, a crayon, and the moon?

Quite a lot. The 1955 classic’s deceptively transparent aesthetic makes it an ideal case study in what we miss when we neglect the art and design of the picture book.

Paul Klee once described drawing as “taking a line for a walk,” and this is exactly how Harold and the Purple Crayon begins. Harold decides “to go for a walk in the moonlight,” draws a moon, and then an entire 64-page adventure in which no line is wasted, and nothing erased.

Johnson creates the illusion that Harold is just making this up as he goes along, but the book is actually one giant drawing, revealed one page at a time. Caught up in the narrative and the story’s apparent simplicity, we don’t notice Johnson’s meticulous design. The invisibility of his artifice makes it seem like we are witnessing artistic creation in real time, and is one reason why Harold and the Purple Crayon has captivated readers for the past 70 years.

…picture books are an ideal place to begin looking closely.

The book has held my attention for most of my life. I read it 50 years ago, began writing about Crockett Johnson 25 years ago, and published his biography 12 years ago. But you don’t need decades to look closely at art that interests you. You need only to focus and to ask questions.

If you read Harold and the Purple Crayon or any of its sequels when you were a child, how has your understanding of the books changed over time? Which left a greater impact on your memory—the books’ words or their images? (Former US Poet Laureate Rita Dove, who counts Harold and the Purple Crayon as her first favorite book, remembers it as wordless.) Why does Johnson give Harold a difficult-to-erase medium (the crayon) instead of an easily erasable one (say, chalk or pencil)? If Harold could erase, what might be the ripple effects of the erasures? Indeed, why does each Harold story conclude with our protagonist still in an imaginary realm, instead of returning him to a real bedroom—like Max in Where the Wild Things Are or the Darling children in Peter Pan—? Is the fact that Harold’s only home is the one he draws for himself a dream or a nightmare?

To ponder these questions (and others) is to accept an invitation to concentration, a practice that modern life discourages. The digital spaces of the social media multiverse thrive on immediacy, on the surprise of new information. They don’t grant us the distance from which to reflect, and to consider. We need to push aside that “heavy black rectangle of potentiality and dread”—to quote Jenny Odell’s description of cell phones—and pay attention to the world around us. Other people. Nature. Art.

And, of course, children’s books have much to say to those of us who are no longer children. Adults may discover insights unavailable to less experienced readers, just as children may arrive at interpretations lost to adults who have forgotten their own childhoods.

We need to push aside that “heavy black rectangle of potentiality and dread”

Though any art grows richer through the pleasures of sustained attention, I choose Harold and the Purple Crayon because picture books are an ideal place to begin looking closely. In addition to being many people’s introduction to visual art, a picture book is a portable art gallery. Perhaps because it arrives via a mass-produced object created for children, picture-book art does not always garner the respect that “fine art” does, even though fine artists Marc Chagall, David Hockney, Faith Ringgold, and Edward Lear (who made his living as a landscape painter) all created children’s books. And some of the finest artists have devoted their careers to creating picture books for young people: Maurice Sendak, Kadir Nelson, Beatrix Potter, Shaun Tan. But it is also fortunate that picture books are a more democratic art form, requiring only a library card, instead of, say, admission (and thus proximity) to a gallery.

Finally, as some of the first narratives we read (or have read to us), picture books show us how stories can make sense of the world and, in the case of Harold and the Purple Crayon, how we can create stories to guide us through that world. As Shaun Tan says of literature for children more generally, “Like a child daubing a paintbrush, it’s just enough to know that even the most modest scribble or wordplay can at any moment lead to a simple but profound realization: the world is just what you make of it, a big, unfinished picture book inside your head.”

The stories we encounter as children teach us whose stories are worth telling, which is one reasons I believe it’s important to explore the question of whether Harold is racially Black. Perhaps because his hands and face are tan, some readers have seen Harold as Black. His racial ambiguity is an inclusive choice—possibly also an intentional one, given Johnson’s early support for Civil Rights.

Since they enter our lives at such a formative time, the books we read when we are small can have a big impact on our imaginations. In this sense, children’s books are the most important books we read. They begin to establish the parameters for our dreaming, for the possible futures we can envision, and for the kind of life we might seek. As Ruha Benjamin puts it, “Who we imagine ourselves to be matters a great deal to who we become.”

Featured image by Townsend Walton via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

January 26, 2025

Some barely iconic, epic usages

Some barely iconic, epic usages

As a linguist, I understand that language shifts and changes. The voiced z sound of houses is being replaced by an unvoiced s sound. The abbreviation A.I. has become a verb, as in “He A.I.ed it.” Neologisms abound, tracked by the American Dialect Society, and new words often make us think of things in new ways.

But I don’t adopt all of the changes. I still say houses with a z. I avoid some new words that seem too flash-in-the-pan (like cheugy and delulu). By the time I might begin using them, they are probably already on their way out. Other neologisms are a bit too clunky for everyday use, like enshittification, or too far removed from my experiences, like stan, or too self-consciously fashionable for my taste, like cray and rizz (the Oxford Word of the Year in 2023). Some bits of neology, I used ironically at first, but soon found myself adopting as part of my everyday vocabulary, like adverbial because or receipts to mean proof. Still, there are some usages that I can’t quite bring myself to embrace.

One is iconic. Everywhere I turn, I hear something described as the most iconic: movies, songs, sports figures, fictional characters, vehicles, photographs. Iconic has shifted to mean “famous.” My experience with the word comes from the semiotic triad of icon, index, and symbol, three of the 66 categories of signs proposed by the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce. There is also the historical use of the term to refer to religious artworks in Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Catholicism. For me, icons are visual representations: they resemble something. Dictionaries have now added definitions like “widely recognized and well-established” or “widely known and acknowledged especially for distinctive excellence.” Iconic has widened its meaning, but I haven’t come along.

I also resist using epic to mean something that is impressive. Epic the adjective comes to us from epic the noun, referring to long narrative poems about heroes (think the Iliad) or to works or legends that are epic-like. As an adjective, it can also refer to deeds or stories that are like those of the classical epics, and it can mean something “extending beyond the usual or ordinary especially in size or scope,” as Merriam-Webster puts it. M-W adds that it has a “broadly, informal” sense meaning “extraordinary” or “impressive”: an epic party, sandwich, vacation, or nap. I can’t bring myself to use epic that way.

Some of the usages I avoid are ones that strike me as fraught with ambiguity rather than trendiness. The adverb barely has shifted for many speakers from meaning “scarcely” or “hardly” to meaning “recently.” But the possibility for misunderstanding became evident when a colleague referred to “a publication that barely came out.” I was barely able to suppress a smile. Barely too will make its way into the dictionary with the new meaning “recently.” It is a subtle enough change, like the generational shift from “by accident” to “on accident,” and will take hold without much fanfare.

I’m happy to be an appreciative bystander to these epic changes, even if I don’t adopt them. Yet.

Featured image by Ross Findon via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

January 24, 2025

The massacre at Fort Mystic and the Puritan “Wars of the Lord”

The massacre at Fort Mystic and the Puritan “Wars of the Lord”

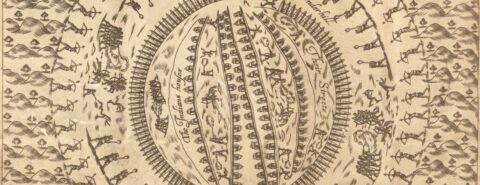

The first light of dawn flickered through the trees as soldiers rushed to take position around the fort. Twenty soldiers from Massachusetts commanded by Captain John Underhill prepared to storm the south gate. Another sixty from Connecticut under Captain John Mason would move against the northeast gate. Behind them, some three hundred Natives—Mohegans, Eastern Niantics, and Narragansetts—formed a perimeter surrounding the fort to prevent anyone from escaping.

It was Friday, 26 May 1637. Inside the fort, known as Mystic, in modern day eastern Connecticut, between four hundred and seven hundred Pequots lay sleeping. As the soldiers crept forward, a dog started barking. The soldiers opened fire. Although the Pequots had been taken by surprise, they offered bitter resistance. Soldiers cut their way into the fort, which they found crammed full of wigwams. Soon as many as twenty soldiers were killed or wounded.

Captain Mason made a snap decision: “We must burn them.” The wigwams were covered with mats made from “rushes and hempen threads” that lit easily. The soldiers withdrew, and the densely packed wigwams quickly became an inferno. Mason ordered his soldiers and their Indian allies to prevent anyone from escaping. While some Pequots fought on, others, including groups of women and children, tried to flee the fort. Soldiers cut them down with swords. “Down fell men, women, and children,” Captain Underhill recalled. “Not above five of them escaped out of our hands.” Only seven were taken prisoner. The rest were killed.

A relieved Mason later proclaimed that the victory belonged to God. “God was above them, who laughed his enemies and the enemies of his people to scorn, making them as a fiery oven,” he crowed. Thus did the LORD judge among the heathen, filling the place with dead bodies.” Like his soldiers, Mason viewed the massacre as vengeance on the Pequots for their brutal raid on the Connecticut town of Wethersfield, back in April, in which nine unsuspecting settlers had been killed. Puritan pastors had assured the soldiers that their cause was just and that God was with them: the heathen were servants of Satan who threatened not only their families and communities, but Christ’s nascent kingdom in the American wilderness.

This was not why the Puritans had come to America. When their leaders recruited potential colonists in England and lobbied the crown for permission to migrate, they had emphasized that their efforts would result in the salvation of the Natives. Indeed, the Massachusetts Bay colony charter, issued in 1629, declared that the “principal” purpose of the colony was to “win and incite the natives of [the] country to the knowledge and obedience of the only true God and Savior of mankind, and the Christian faith.” The colony seal depicted a humble Indian petitioning the English to “come over and help us,” which was exactly what most Puritans thought they were doing. They viewed their efforts as a sort of spiritual warfare in which they were saving Native souls from Satan’s tyranny.

Their efforts had begun peacefully enough. Alliances and trade relations had been established with many Native communities. But many Puritans had imagined that the Natives would embrace Christianity with open arms, and this did not happen. When Indians aligned with the Pequots killed an English trader, the English felt they had to retaliate with a raid against the Pequots. When the Pequots retaliated in kind, the English decided to destroy them. A spiritual war for Native souls devolved into a military campaign to obliterate a Native nation.

The massacre at Mystic was a low point in English-Native relations, and the Pequot War was relatively brief. The support of the Mohegans, Eastern Niantics, and Narragansetts for colonial forces is a reminder that more Indians supported the English during the Pequot War than opposed them. If anything, English military dominance enhanced the credibility of Christianity among Indians. A renegade Pequot named Wequash, who had guided colonial forces to Fort Mystic, was so stunned by English power that he became convinced their God was real, converted to Christianity, and began to evangelize other Natives. During the 1640s, numerous Native communities began to submit to the English and accept Christianity. Thanks to the efforts of missionaries like John Eliot and Thomas Mayhew, over the next three largely peaceful decades, thousands of Natives would accept Christianity. Some twenty “praying towns” were organized where Indians were guaranteed their land in exchange for submitting to Christian teaching and administering their own Christian governments.

Nevertheless, the massacre at Mystic was a constant reminder of what the English could do if America’s First People resisted them. The Puritans wanted to conquer the Indians for Christianity through love and justice, but they were willing to conquer them by force if provoked, and they were fully convinced that this too was in accord with God’s will. Conscientious Christians would protest cases of injustice, but there was never a doubt whose side they would take if war broke out.

It all came to a head in King Philip’s War, perhaps the bloodiest war per capita in American history, fought in 1675-1676. Once again, the English and their Indian allies–some Christian, others not–squared off with their Indian enemies. This time the conflict would rage across New England and beyond. Puritan ministers reminded their people that they deserved God’s wrath, but they also insisted that God would not abandon them if they repented and faithfully defended Christ’s kingdom. Their Christian Indian allies did not disagree. Some Indians believed their own welfare required supporting the English. Others were convinced that the English had to be defeated. Religion, culture, trade, government, even simple survival–everything was at stake. All came down to the catastrophe of a war that would decide the fate of New England.

Featured image Engraver unknown. Author of folio was John Underhill (1597-1672). Photo-Facsimile by Edward Bierstadt (1824–1906), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers