Oxford University Press's Blog, page 11

January 22, 2025

Returning to Yule

Alexander Hislop.

Alexander Hislop.Image by DJKinsella via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

A reader, as I mentioned in one of the most recent posts, called my attention to the 1853 book The Two Babylons by the Reverend Alexander Hislop. The book, which has been reprinted many times since the middle of the nineteenth century and is still easily available, contains an original etymology of the word Yule (and this is why the comment was written). I have now read Chapter 3 “The Festivals.” Among other things, it deals with Yule. Hislop’s suggestion was new to me, because no linguistic sources mention it. His etymology of Yule is, most probably, indefensible, but ignoring it would be a mistake. In etymological research, wrong hypotheses should be refuted, rather than ignored. I’ll repeat this maxim at the end of the essay.

Chapter 3 begins with a reasonable idea that, given the description in the Gospels, Jesus could not be born on the 25th of December, because the shepherds of Judea were unlikely to watch their flocks in the open fields later than the end of October. I suspect that in the numerous critiques of the biblical text, similar doubts have been voiced more than once. Of course, here Hislop makes an obvious leap: Jesus could indeed be born on the day indicated. It is only the connection with the story of the shepherds that may not inspire confidence. In a broader context, this is a famous problem: if something in the Gospels is wrong, then anything can be wrong. Theology is not my area. I’ll only mention the fact that Hislop referred to several of his predecessors who had the same doubts about the date.

The Adoration of the Shepherds.

The Adoration of the Shepherds.Image by Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915, Metropolitan Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons. CC0 1.0.

Also, at the time of Christ’s birth, every woman and child, we are told, was to go to be taxed at the city to which they belonged, but, Hislop says, the middle of winter was not fitting for this business. Finally, according to the book, no such festival as Christmas was ever heard of till the third century. Hislop wrote: “Long before the fourth century, and long before the Chistian era itself, a festival was celebrated among the heathen, at that precise time of the year, in honour of the birth of the son of the Babylonian queen of heaven, and it may fairly be presumed that in order to conciliate the heathen and to swell the number of the nominal adherents of Christianity, the same festival was adopted by the Roman Church, giving it only the name of Christ.” Let us remember that the book was directed against Catholicism. Therefore, Hislop spared no arrows for his target. Also, the indebtedness of Christianity to pre-Christian beliefs is one of the most often discussed points of comparative religion. In a similar context, the name of some obscure female divinity also occurs in the book by the Venerable Bede (see the post on jolly Yule).

Hislop wrote that Christmas had originally been a pagan festival. This statement will again not surprise anyone: a new year is born, and the deity is supposed to be born on the same day, to mark the event. And here we are approaching the place for whose sake this short essay has been written: “The very name by which Christmas is popularly known among ourselves—Yule-day—proves at once its pagan and Babylonian origin. ‘Yule’ is the Chaldee name of an ‘infant’ or ’little child’; and the 25th of December was called by our Pagan Anglo-Saxon ancestors ‘Yule-day’ or the ‘Child‘s day’, and the night that precedes it, ‘Mother-night’, long before they came in contact with Christianity, that sufficiently proves its real character” (pp. 94-95). Hislop cites Chaldee Eöl “infant, little child.”

Chaldee takes us to southern Babylonia (now southern Iraq), and indeed, some parts of the Old Testament were written in Chaldean Aramaic. Not being a specialist, I cannot comment on the form Eöl, because I know only Hebrew yeled and olel ~ olal “infant, little child.” (Yeled has been more than once incautiously cited as the etymon of English lad.) Eöl does not look familiar, but even if this form is correct, Hislop’s etymology carries no conviction.

Let me repeat the basic facts. Yule is not an isolated English noun. The oldest English forms were geohhol and gehhol (g had the value of Modern English y, as in yes). Old Norse (Icelandic) jól, and Finnish juhla, borrowed from Scandinavian, prove that the word once had h in the middle. When that h was lost, the preceding vowel became long. The unrecorded protoform is a matter of reconstruction, but it probably sounded approximately like jehwla, that is, yehwla. If the form Eöl existed and had been borrowed, Germanic speakers would hardly have maimed it into jehwala, jeohol, or something similar. Hislop’s idea has, I think, a rather simple explanation.

When close to the beginning of the seventeenth century, European etymologists began their guessing game, they believed that the words of their languages were the continuations of words in either Hebrew, Greek, or Latin and suggested corresponding sources. To be sure, in 1832, a good deal was known about the origin of the Germanic languages, but though comparative philology had made great progress in Germany, it took a long time before it had reached Great Britain. Hislop, a Scotsman, was not a philologist and despite his erudition and proficiency in the languages of the Bible had probably never heard about Jacob Grimm’s contributions to historical linguistics. His first impulse must have been to trace an English word to Hebrew. I may add that he, who in other cases supplied his theses with numerous references, offered no discussion of the Chaldee derivation of Yule, as though it was self-evident.

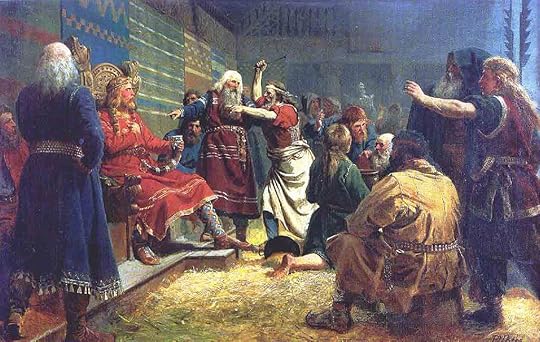

That Yule is a pagan festival needs no proof and has always been known. For example, in Scandinavia, Yule was celebrated in “midwinter,” on the twelfth of January. King Haakon the Good, who reigned in Norway from 935 to 960, spent his childhood and youth in Britain (he was King Athelstan’s foster child) and returned to Norway as an observing Christian but had to make all kinds of concessions to the earls, in order to retain the throne. Therefore, in Norway, he lived as a pagan, but at least he decreed that the celebration of Yule be moved to December 25th. Today, Yule and Christmas are inseparable.

Haakon the Good, a reluctant pagan.

Haakon the Good, a reluctant pagan.Image by Peter Nicolai Arbo via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Was it worth writing a post to debunk an etymology that is almost two centuries old? Obviously, if I did not think so, I would not have written it. Our correspondent knew Hislop’s idea but added that not everybody agrees with it. Apparently, Hislop’s suggestion is still current in some circles, even though dictionaries have either never heard about it or don’t (didn’t) think it worthy of refutation. Well, I have done all I could to refute it. And a last remark. The lifeblood of every blog is the readers’ questions and comments. I don’t receive enough of either, and this fact is to be regretted. Only when I make a stupid mistake, do I realize that everything goes per plan. Please write more. “To whet you blunted purpose,” we have put a picture of a mailbox in the header.

Featured image by Erik Mclean via Pexels.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

January 19, 2025

“My fellow Americans” [timeline]

“My fellow Americans” [timeline]

Every four years, the incoming president of the United States delivers an inaugural address in a tradition that dates back to 1789, with the first inauguration of George Washington. The address reiterates to Americans—and peoples around the world—what the country has been and what it has the potential to become. In a speech freighted with importance, the presidents express their fears, their hopes, and their most personal aspirations for the nation and for democracy.

As we enter a new presidential term, explore the timeline below to revisit some past inaugural addresses that capture snapshots of America at unique points in time:

Featured image by acaben via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

January 15, 2025

Beyond the paycheck

In the age of gig economy, remote work, and juggling multiple jobs, unpaid labour is no longer confined only to the domestic sphere or volunteerism. It is now an insidious undercurrent in paid employment, eroding worker rights and deepening inequality. From the creative freelancer logging extra hours to secure their next project, to the care worker stretching beyond paid duties to ensure a client’s wellbeing, unpaid labour permeates contemporary work. But why does it persist, and how can we confront the structural inequities it perpetuates?

This question lies at the heart of today’s most pressing debates on work and labour. The phenomenon of unpaid labour—work performed without direct or low compensation—is not merely a byproduct of precarious work; it can actively sustain and exacerbate it. It is time to unmask the political and structural forces behind this unpaid toil and demand systemic change.

Who benefits from unpaid labour?Unpaid labour operates as a hidden subsidy to employers. In many industries, workers are compelled to extend their working day without additional pay to meet deadlines, maintain job security, or adhere to “ideal worker” norms. Internships, unpaid overtime, and tight employer control over schedules are just a few examples. This trend is especially pronounced in gig and platform work, where freelancers compete in a global marketplace, often shouldering risks and costs previously borne by employers.

The irony is glaring: while unpaid labour generates profits for employers and value for markets, it disproportionately harms workers. Financial insecurity, job unpredictability, and the erosion of social benefits are direct consequences. The concept of “wage theft” and “income theft” captures this injustice aptly: workers are denied the full value of their effort, trapped in a cycle of intensifying precarity.

Precarity as a process, not just a conditionTo understand the entrenchment of unpaid labour, we must shift from viewing precarity as an isolated economic condition to recognizing it as a process shaped by systemic power imbalances. Neoliberal labour policies have deregulated employment, weakened unions, and heightened employer control over workers. These dynamics enable employers to extract unpaid labour under the guise of norms, even underpinning career advancements.

For instance, in care work—an industry already strained by privatization and cost-cutting measures—unpaid labour often takes the form of emotional labour and unpaid overtime to meet ethical or relational commitments to clients. Similarly, in creative sectors like dance or art, unpaid labour masquerades as “investment” in one’s career, pushing workers to accept unpaid gigs for visibility or future opportunities. Platform workers, on the other hand, endure unpredictable schedules and unpaid “waiting time” between tasks. Across these sectors, the pattern is clear: unpaid labour sustains an unequal distribution of risk and reward.

The inequities of unpaid labourThe ability to endure unpaid labour hinges on access to resources—financial, institutional, and social. Workers with familial wealth, spousal support, or robust welfare systems can buffer its impact, creating a divide between those who can afford to subsidize their work and those who cannot. This dynamic perpetuates inequality not only between individuals but also across class and identity lines, such as gender and race, as marginalized groups often lack the resources needed to sustain unpaid labour without severe consequences.

Treating unpaid labour as a personal sacrifice or a stepping stone to success obscures its broader societal harm. Instead, we must recognize it as a structural issue demanding systemic change.

Demanding systemic change: power redistributionUnpaid labour is not an individual failing or just a symptom of precarity but a result of the ways systemic forces—like policies, cultural norms, or economic structures—create and maintain unequal power relations. This approach highlights the interconnectedness of unpaid labour and structural conditions, moving beyond individual experiences to address the root causes. Within this context, unpaid labour is a symptom of deeper structural inequalities. Tackling it requires us to rethink the politics of work, from labour laws to norms and narratives. By exposing the hidden costs of unpaid labour and advocating for systemic change, we can create a fairer, more equitable world where work is dignified, compensated, and sustainable. It is time to reclaim the ‘value’ of labour and demand justice for all workers. If unpaid labour is a political issue, then addressing it requires political solutions.

Here are four concrete steps to counter its corrosive effects:

1. Make collective bargaining effective by including workers with insecure, irregular, and informal connections to paid work.

An inclusive approach should ensure that collective agreements apply across entire sectors, covering even small or informal businesses. This would prevent companies on the fringes of the formal economy from exploiting gaps in worker protections. It also requires trade unions to mobilize and organize across traditional divides by forging alliances with grassroots organizations that have strong connections to disadvantaged workers. For example, in Germany, migrant care workers fought to have their qualifications recognized, a struggle that could benefit from union support.

2. Reduce working time in paid employment for waged labour to give workers more time to manage personal and family responsibilities, reducing their reliance on unpaid labour to meet these needs.

This approach is particularly impactful for caregivers and those juggling multiple jobs, who often bear the brunt of unpaid work. By redistributing work across more employees, reduced working hours can also create formal employment opportunities for those in precarious or informal arrangements. To ensure this policy is effective, wage adjustments and income protections must accompany shorter hours to prevent workers from losing income or facing increased workloads within reduced timeframes.

3. Introduce government policies which subsidize reduced working hours through tax incentives or direct wage supplements.

For instance, caregivers taking on fewer paid hours could receive compensatory support to ensure financial stability. Employment laws must also prevent employers from imposing unreasonable productivity targets during shorter work periods, protecting workers from intensified labour demands. Additionally, investment in public services like affordable childcare, eldercare, and healthcare can alleviate the unpaid labour burden that disproportionately falls on women and marginalized groups.

4. Promote educational initiatives and public campaigns that challenge the narratives normalizing unpaid labour.

The myth of the “ideal worker”—endlessly available, self-sacrificing, and driven by passion—legitimizes exploitation and reinforces gendered divisions of labour, where unpaid work is disproportionately carried out by women. By questioning these harmful narratives and recognizing the social and economic value of all forms of labour, we can foster a culture that values humanity and sociality over mere productivity.

Featured image by Eric Muhr via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Year in, year out

As promised last week, the topic of this post is the history of the word year. It is hard to tell what hampers etymological discovery more. Consider two situations. If a word is relatively late and has no cognates, language historians are usually lost. This is what happens in dealing with slang and rare (isolated) regional words. For example, someone must have coined dweeb and nerd. Though the clues to their origin are lost, intelligent guessing is encouraged. In contrast (this is the second situation), some words are ancient and have numerous congeners (cognates). Now it is the embarrassment of riches that makes us stop dead in our tracks. Such is the case of year, a word with multiple related forms in and outside Germanic.

From the manuscript of Hildebrandslied.

From the manuscript of Hildebrandslied.Image by Wilhelm Grimm, Internet Archive via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

In our oldest texts, this word seems to have meant what it means today, but in the remotest past, who, we wonder, needed it? We understand why people coined words for “day,” “night,” “winter,” “spring,” “summer,” and “fall” (“autumn”). Given four seasons, each was used differently for cattle breeding and agriculture. But year? Why have a special name for the entire cycle? Though the oldest (that is, medieval) German poetry is almost lost, one famous song (“Hildebrandslied”) has come down to us, and in it, Hildebrand, its younger protagonist, says that he spent sixty summers and winters abroad (which probably means “thirty years,” that is, “thirty winters and thirty summers,” the sum being equal to sixty). Germanic people counted years by winters, and following the tradition, Sonnet 2 by Shakespeare opens with the warning: “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow….” Since there is only one winter in a year, the implication is obvious. By contrast, the Russian for “how old are you?” is “How many summers are yours?” (“Skol’ko tebe let?”; leto “summer.”) The Slavs measure time by summers. Both systems make perfect sense.

Those who read this blog with some regularity won’t be surprised that our first reference will be to Gothic, a language that preserved the oldest long text in a medieval Germanic dialect. The fourth-century Gothic Bible was translated from Greek, and for Greek étos, the Gothic text has jer, an obvious cognate of English year. But when the reference was to several years, the translator(s), for whatever reason, used wintrus “winter”! Moreover, when the translators came across Greek éniautós “of one year old,” the unexpected Gothic word aþn (read: athn) turned up, and apparently, it was not too exotic a term, because at-aþni “year” (again in the plural) has also been recorded, indeed once. Aþn is an obvious cognate of Latin annus “year” (from the root of annus English has annual, among a few others). Was it another everyday word for “year”? The origin of Latin annus is obscure. It seems to refer to the idea of regular change, and unexpectedly, in this case, classical scholars refer to the rare Gothic words for support, that is, lean on a broken reed. The case remains unresolved.

We may wonder why Gothic speakers needed three synonyms meaning “year.” To be sure, the translators suggested three different Gothic words for three Greek words in the original, but they did not invent or coin them. Nor was their translation of the Bible literal or slavish. The natural reference among the Goths, as among all the Germanic speakers, must have been to “winters,” but for “several (many) years” they preferred other words. We are confused. (Compare the beautiful English dialectal word twinter: “a domestic animal of two years [winters] old.”)

Happy twinters.

Happy twinters.Image 1 by Helena Lopes via Pexels, Image 2 Ellie Burgin via Pexels.

As regards our subject, the question is predictable. We want to know what Gothic jer, Old English gēar, Old Icelandic ár, and the rest of them meant originally. What is their etymology? Parallels from non-Germanic languages provide little help. Thus, Russian god “year” is related to English gather and together. The word seems to refer to regulating time, joining things, and the like. The main Slavic word for “year” is rok, whose basic sense must also have been “order.” In Modern Slavic, among the cognates of rok, we find “speech” (that is, “something ordered”), “allotted time,” and even “fate.” Neither those senses nor the senses in several other languages make the distant origin of year more transparent.

Etymologists have suggested two solutions. One of them has the support of Greek óra “time, season; spring” and óros “year,” safe congeners of year. We have seen that when Goths wanted to say “many years,” they referred to winters, rather than springs. But even if we disregard this discrepancy, the picture will not look quite neat, because Gothic jer, a poor synonym for “winter,” also sometimes occurred in the plural! One could say “many years” and “many winters.” We don’t know how Gothic differentiated between those plurals. That nicety aside, language historians look for ancient roots, and words like Sanskrit átati “goes” provided them with such a root. A year emerged from that comparison as a unit that “goes, passes.” However, this etymology has a hitch. When we look for the reconstructed (ancient) roots of our words, we usually find some concrete entitles. For instance, hammer is related to a word for “stone.” This makes perfect sense. “Go,” by contrast, is a vague general concept, and one could expect that it appeared as the result of later generalizations. Hence a search for a competing hypothesis.

Here is an interesting detail: though Old Icelandic ár did mean “year,” first and foremost, it referred to “fruitful season, economic prosperity.” One made sacrifices “til árs ok friðar,” that is, to a fruitful (!) year and peace. A poem in Old English contained the same message. Likewise, Greek ōra referred to several units of time (hour, day, and season), but its main senses were “prime, fruitful season; spring.” Slavic yar- also referred, first and foremost, to “spring.” Students of Slavic etymology traditionally compare this word with year. One notes that some scholars hardly ever bother to refute or even discuss the idea that “year” signifies “spring,” while others either stay on the fence or take the tie between year and yar (and spring) almost for granted.

Long live Primavera.

Long live Primavera.Image by Sandro Botticelli, Uffizi Gallery via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

This is not a rare situation. The literature on word origins is so full of incompatible hypotheses, and the authority of the best scholars is so strong that many excellent ideas are overlooked or ignored. Hence the benefits of etymological dictionaries that give a complete survey of all conflicting views. English dictionaries, at least beginning with Skeat’s, find the connection between “year” and “spring” probable but formulate their conclusions most cautiously. The original OED remained in this case non-committal.

Obviously, we will never know for sure how the word year was coined millennia ago. But if I were to choose, I would vote for the idea of “spring,” rather than for “pass, go” as its semantic base. I am pleased to report that Elmar Seebold, the latest editor of the most authoritative dictionary of German etymology, though hesitatingly, decided to support the “spring” version of the origin of the word year. By contrast, in the latest edition of the great Gothic dictionary, “year” is said to denote “moving, passing.” I respectfully disagree. Long live spring!

Featured image by Adam Chang via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

January 9, 2025

Racialized Commodities

In the mid-sixth century BCE, the Greek mystic Aristeas of Proconessus composed a hexameter poem recounting a journey deep into Eurasia. According to Herodotus, Aristeas set off from his island home in the Sea of Marmara to visit the “one-eyed Arimaspians, and beyond them the griffins which guard the gold, and beyond the griffins the Hyperboreans, whose land comes down to the sea.” Very little is known about Aristeas’ poem, which was already considered obscure in Herodotus’ time. At one time, some critics thought that Aristeas must have been initiated into a shamanic cult. At the very least, we can say that Aristeas’ poem was suffuse with insights about nomadism on the steppe.

One haunting fragment appears to report the first time a steppe nomad laid eyes on a Greek ship:

Now this is a great wonder in our hearts. Men dwell in the water, away from land, in the sea; they are wretched, for they have harsh toils; eyes on the stars, they have a heart in the sea. Often stretching their hands up to the gods, they pray for their turbulent hearts.

Around 700 BCE, Greek speakers fanned out across the Mediterranean in search of work, new land, and trade. In the densely settled eastern Mediterranean, Greek speakers slotted themselves into preexisting political and economic structures, as they would in Late Period Egypt. Greeks practically introduced the art of navigation into the Black Sea, instigating a long period of social upheaval as indigenous populations vied for the opportunity of trade.

Through a wide range of encounters—some exploitative, and others not—Greek newcomers transmitted a disorganized catalog of observations and reflections on foreign peoples into what I call a “racial imaginary.” Up until around 500 BCE, this imaginary was basically unstructured. But in the wake of Persia’s fifth century interventions in the Aegean, the “racial imaginary” would coalesce into the menacing barbarian “Other”—a cultural construct that would be mobilized to endorse conquest, enslavement, and unequal treatment all over Greece. It is in this sense that the otherwise-neutral physiognomic descriptions found in a sixth century author like Xenophanes, who speaks of “dark-skinned Ethiopians and gray-eyed Thracians” would later be repurposed into the buffoonish stereotype of enslaved Thracians that people Attic comedy.

Ceramic comic mask representing an enslaved Thracian, Hellenistic Period.

Ceramic comic mask representing an enslaved Thracian, Hellenistic Period.[Image courtesy of the Princeton University Art Museum, y1950-69. Public domain.]

“Race” is a controversial word in the study of premodernity. For most of the last eighty years, premodernists avoided it. The decades prior to World War II represented the highwater mark of racialism, a historiographic school that interpreted the competition between races as the main act of world history. (Aside from a general sense that northern Europeans were innately superior, there was substantial disagreement as to how these races should be defined). During the war, a generation of anti-racist historians including Eric Williams (1911-81) and Frank M. Snowden, Jr. (1911-2007) debunked the racialist thesis by turning to the social sciences, where revulsion towards Nazi atrocities had discredited previously-ascendent racial theories. According to these scholars, racism (which they tended to assimilate into anti-Blackness) is a discrete, historical development linked to efforts to legitimate the transatlantic slave trade using the language of human biology. To argue that it existed prior to the eighteenth century would be anachronistic.

This perspective on race and racism has dominated the premodern humanities ever since. Open any book and learn that ancient slavery was colorblind; even scholars who recognized the ubiquity of ancestry-based discrimination in Greece or Rome shied away from the language of race and racism, for instance offering circumlocutions like “proto-racism” when pressed. In the 2000-10s, pioneering scholars including Denise McCoskey, Susan Lape, and Geraldine Heng gravitated toward a school of American legal thought known as Critical Race Theory (CRT) in an effort to identify race as a social phenomenon across premodernity. The midcentury anti-racists had approached race from the perspective of science: the concept of race could not exist in societies that lacked a science of biology. But CRT defines race as a practice: to be a racist is to (in Heng’s words) enact “a hierarchy of peoples for differential treatment,” regardless whether one has a coherent ideology to justify such treatment or not. Simply put, the practice of racecraft long preceded the emergence of racial pseudo-science in late eighteenth century Europe. In any period of history, people who mistreated other classes of people based on perceived notions of ancestry, physiognomy, or both—even deeply confused ones—can be called racists.

When Aristeas arrived in what is now Ukraine or Russia in the early sixth century BCE, he did not bring the baggage of racism with him. People in Archaic Greece had a fluid vision of humanity, believing in hybridized beasts, gods in human form, and heroes among one’s ancestors. Some Greeks even believed they descended from Egyptian pharaohs. As Aristeas and his comrades unleashed forces of social transformation on the steppe, they brought with them a jumble of new visions of the human body. In the very first generation of Greek colonization, settlers were depositing Egyptian-style faience seals molded into the shape of human heads into graves. Greeks were learning to catalog, inspect, and curate images of the human body long before human diversity became an index of oppression. (FIGURE)

Seal in the form of a head of an African head. From sixth century BCE burial in Olbia, Ukraine. Excavated by B. Pharmakowski in 1908. After B. Toueaïeff, “Objets égyptiens et égyptisants trouvés dans la Russie méridionale.” Revue Archéologique 18 (1911): 20-35. [Public domain.]

Seal in the form of a head of an African head. From sixth century BCE burial in Olbia, Ukraine. Excavated by B. Pharmakowski in 1908. After B. Toueaïeff, “Objets égyptiens et égyptisants trouvés dans la Russie méridionale.” Revue Archéologique 18 (1911): 20-35. [Public domain.]And an index of oppression it would become. When Classical Athenians imagined the snowy lands to the north of the Black Sea, they saw a forbidding territory inhabited by wild ‘Scythians’ and ‘Thracians,’ names insisted upon despite the region’s multiplicity of cultures. To Athenians, the people of the north were archetypical slaves: light-skinned, prone to flush, dim-witted, and sexually available: evidence for their lives can be found everywhere from the literary sphere to auction records to the funerary markers inscribed not with names, but an expression like “Useful Scythian.” They were subject to ethnographic and medical speculation; they were subject to Athenian laws, but rarely protected by them. Rendered commodities by the slave trade, they were racialized in their everyday experience of Athenian life.

Featured image by Gary Todd via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

January 8, 2025

The year is new and young. Everything else is old

The year is new and young. Everything else is old

Happy New Year and welcome back! First of all, I wish to thank those who commented on the last post of 2024 and those who sent me emails about the words jolly and Yule. I still think that the first sounds of jolly and Yule are incompatible. I have not read Alexander Hislop’s book The Two Babylons (many thanks for the reference), but I will do so before 2025 becomes old. This is my first New Year resolution. On the face of it, the Chaldee etymology of Yule has moderate appeal. For the fun of it, I would like to refer to a letter of a Dutch correspondent that appeared in Notes and Queries in May 1868. He mentioned the Dutch verb jolen (at that time, it was spelled differently), pronounced with the vowel of English Yule. He glossed the verb with “to revel, make merry.” Dutch jolen is a sound-imitative word, like English yell, yawl, and a few others. It would be nice to suggest that Yule was a time of jubilation, yelling ~ yawling for joy, and so forth, but this “suggestion” is hopeless. Finally, in my post, I mentioned Greek epsía as a word of unknown origin. Its root (psía) is related to the root of psyche “breath, spirit,” and it is this root that is of dubious origin.

This baby is new and young!”

This baby is new and young!”Image by Oss Leos via Pexels.

And now to business. 2024 is gone. It is an old year. Why then (I am asking it tongue in cheek) is 2025 new, rather than young? For example, a newborn baby is of course a newcomer, but its main feature is its tender youth, rather than newness. Obviously, language views every next year as a replacement for the old one. Isn’t it puzzling? 2025, for example, was not substituted for 2024. Incidentally, “old” is also a complex notion. For instance, Latin vetus (its root is discernible in English veteran) referred to things that have succumbed to age (that is, things decrepit, dilapidated). When this epithet was applied to living creatures, it had the sense “feeble, infirm.” By contrast, senex (related to English senile) served as a stylistically neutral antonym of the word juvenis “young.” English juvenile will be mentioned below, and old too will be discussed. Naturally, both veteran and senile reached English via French.

Defying etymology: a young veteran.

Defying etymology: a young veteran.Image by RDNE Stock Project via Pexels.

As always, we would like to know why an ancient root like vet-, from wet-, made people think of old age. And as always, once we leave the area of sound-imitative and sound-symbolic words, we receive no answer. Yet we can sometimes notice curious associations. For example, in this case, we observe that the complex (or root) wet– regularly occurs in the names of animals. English wether, which occasionally turns up in this blog but is familiar to few modern speakers (unless they know the tongue twister “I wonder whether the wether will weather the weather or whether the weather the wether will kill”) means “a gelded ram,” apparently, “yearling,” because animals were gelded at the end of their first year. Latin vitilus “calf” (and unexpectedly, “heifer”) belongs with English wether.

Did the history of words sharing the root vet– (or wet-) begin with domestic cattle or with watching the calendar? We don’t know. In any case, let us repeat: no sound imitation or sound symbolism is detectable in the root, and we are left with a bunch of related words, a familiar handful of etymological dust. It would be nice if a time machine could carry us tens of thousands of years back and allow us to witness a farmer calling his young animals wet-wet-wet. Then everything would have become clear and we could have asked the man (naturally, in Proto-Proto-Indo-European) why wet-wet-wet had been chosen as a call to his grazing heifers and calves. Such a time machine is not yet available, and this is a blessing in disguise, because if it existed, the few etymologists who are still employed would have lost their jobs, and there would have been no need for this blog (the latter event would have been a catastrophe of global dimensions).

A calf and heifer, one of them unaware of its future.

A calf and heifer, one of them unaware of its future.Image 1 via Pickpik. Public domain. Image 2 by Jennifer Campbell (JENMEDIA) via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Curiously, on a more serious note, speakers avoided the connection, so obvious to etymologists. In the languages in which words like vetus referred to old age, they never referred to “year.” The opposite is also true. English offers a good example: the root of the word year (about which I’ll write a detailed essay next week) has nothing to do with old.

Let us now turnto old. As behooves such a venerable word, it has been known in English and Germanic for millennia. If we disregard the phonetic differences, we’ll see (or rather, hear) that it sounded the same in medieval Scandinavian, Old High German, and elsewhere. There is no need to cite the forms. The Gothic word was also very close, but it had some peculiarities that are of no importance in the present context. The German for “old” is alt, and the root of our adjective was al-, as in Gothic alan “to grow.” Even better matches are Old Icelandic ala “to beget” and Old English alan “to nourish.” Old emerges as “grown, fed properly.”

The opposites of old are new and young. Our year is new, and for the moment, this will be our point of departure. The adjective new, like old, goes back to hoary antiquity. Once, the adverb nu existed, and English now is its descendant. It sounds like an interjection for encouragement (nu-nu! “go ahead!”), but whether such is the origin of now remains unknown. Yet the link between new and now is certain. This link makes perfect sense: that is new which we now see before our eyes.

And now a few remarks about the adjective young, the aforementioned synonym of new. (Don’t forget: this essay has been inspired by the celebration of the New Year.) Young, like old, is another ancient adjective. Its Latin cognate is iuvencus, partly recognizable in English from juvenile and juvenilia (the second word means “works produced in one’s youth”). The origin of young has been a matter of debate for a very long time. Since new has its source in the adverb nu, perhaps young (from the older form iung) goes back to the ancient adverb iu “already.” But why already? Who waits for youth? Or perhaps young is akin to the root of Latin aevum “age, life” (think of English medieval ~ mediaeval “pertaining to the Middle Ages”). If so, then young should be understood (from an etymological point of view) as “full of stamina, endurance, vitality.” The other suggestions known to me are not worth mentioning. Young, unlike old, is a word of “contested origin.”

As we can see, the New Year will again be full of riddles and will not allow lovers of etymology to feel bored. New, young, old! And as promised, next Wednesday, we’ll look at the history of the word year and leave all the celebrations behind, regardless of whether you use the Julian or the Gregorian calendar.

Featured image by Matheus Bertelli via Pexels.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 23, 2024

Theories of Global Politics meet International Relations theories

Theories of Global Politics meet International Relations theories

The study of world politics developed via a series of famous encounters, sometimes called the ‘great debates’. The first major encounter, dating to the early twentieth-century, was between utopian liberalism and realism; the second between traditional approaches and behaviouralism; the third between neorealism/neoliberalism and neo-Marxism.

These encounters have always been emphasized among those who teach world politics: they provide a mental map of the way the academic subject has developed over the past century. But they are also substantially important. They have enriched the discipline because they have forced theorists of different stripes to further sharpen their arguments and, occasionally, to try to synthesize insights from other theories and approaches. The most recent encounter is between established International Relations (IR) theories and what we term theories of Global Politics (GP). This is where the action is in the study of world politics today.

The GP challengeGP theorists raise both methodological and substantial issues in their criticism of established theories and approaches. They argue against positivist methodology with its focus on observable facts and measurable data and its ambition to scientifically explain the world of international relations. GP theorists emphasize that IR theorists (like all other theorists of human affairs) are an integrated part of the world they study. There is no objective truth, no ‘gods-eye view’ standing above all other views.

GP theorists echo the French philosopher Michel Foucault, who famously argued that truth and power cannot be separated; indeed, the main task of these dissident approaches is to unmask that intimate relationship between truth and power. ‘Truth claims’ are always linked to historical context and especially to power. The broader task is to examine the world from a large variety of political, social, cultural, economic, and other perspectives.

The radicalness of this criticism can be illustrated by a brief comparison with one of the established IR approaches, social constructivism. Social constructivists argue that the international system is constituted by ideas, not material power. This focus on ideas and discourse is something constructivists share with post-structuralism, a GP theory. But for post-structuralists, it is ideas and discourse all the way down; there is not a world out there we can study independently of the observer.

When this is the case, general theories are not possible, because concrete, historical context is always decisive. Yet IR theories purport to be general theories about international relations. GP theorists find that a misleading claim; there are competing views about how the world hangs together and what makes it tick. Since there is no objective reality, say post-structuralists, knowledge cannot be neutral. Therefore, language and discourse must be in focus; they are essential for the construction of reality. The dominant theories of IR must be exposed for what they are; stories from a certain point of view that must be confronted with other, alternative stories.

On this basis, GP theorists have revisited some of the founding moments of the study of world politics, to expose what they see as myths and to show how very different stories can be told. A case in point is early liberalism, part of the first encounter mentioned above. This has traditionally been seen as a progressive approach to world politics, with the noble aim of making ‘a world safe for democracy’, in the words of the US president Woodrow Wilson, a key voice in early liberal thought.

[E]ven well-established points of consensus can be challenged by these alternative readings.

Postcolonial scholars point out how Wilson was a staunch defender of racial hierarchy in the United States and that he did not press for self-determination for non-European peoples. They argue more generally that imperialism and race played a very significant role in the early study of IR. The discipline’s first journal, founded in 1910, is what we know today as Foreign Affairs; but its original name was the Journal of Race Development. The early liberal hopes for peace and democracy, then, were confined to the ‘civilized’ West. From early on, they were combined with considerations of imperial domination and racist supremacy in other parts of the world. This shows how there are always different stories to tell, and how even well-established points of consensus can be challenged by these alternative readings.

In this pursuit, the substantial emphasis of GP-theorists differs: post-structuralists emphasize power and discourse, postcolonial scholars emphasize voices of the Global South, feminist and queer theory emphasize gender and sexuality, and green theory emphasizes the environment.

GP theories compared. Used with permission.Making the encounter productive

GP theories compared. Used with permission.Making the encounter productiveFor more than a century, the study of world politics has benefited from the different encounters between theories and approaches. Students of world politics should thus not lament or grieve over the many different, sometimes puzzling, approaches that have emerged in the discipline. Together, they create a vast and diverse field of opportunities for a better understanding of world politics.

However, to get a productive dialogue between different perspectives, it is important that the participants in the debates keep an open mind. The present intense and sometimes explosive debate between IR and GP theories has frequently not moved in that direction. There has often been a tendency to move towards confrontation in ways that belittle the opponent, creating strawmen which are easy to destroy.

[T]hey create a vast and diverse field of opportunities for a better understanding of world politics.

We find the tendency towards confrontation to be unproductive. The major dividing line in the discipline, in our view, is not between IR and GP. It is between, on the one hand, scholars on both sides who seek confrontation, often combined with reductionism and myopia, and, on the other hand, scholars on both sides who want to pursue cooperation which promises to advance our grasp and comprehension of what is going in the world and how we can understand it. Therefore, we should avoid an overemphasis on dividing lines between different approaches. Instead, we should look for possibilities of cooperation that promise to advance our knowledge and understanding of the world.

*Some sections of this blog post are taken from the chapters of Introduction to International Relations and Global Politics.

Featured image by Lara Jameson via Pexels.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 20, 2024

Meaningful economics

Human beings mean. We just do. Human beings contemplate the importance or significance of everything, be it a person or a place, an action or a consequence, a possession or an idea, a relationship or our well-being, an experience or our connection to something greater than ourselves. If it can be some kind of thing, we value it, inevitably and instinctively. Human life is imbued with meaning, and our conduct is guided by values and purpose. Economics is no different. It’s steeped in meaning.

Meaningful economics? The question is whether economic science is as much about purpose and human values as it is about describing and predicting the “what is” of economic events. Is economics in fact full of meaning? And what do meaning and value and purpose have to do with traditional talk about economics?

If there is something that almost all economists agree on, it’s that economics is about cost-benefit analysis, not moral human conduct. But why? Why must we separate economics and ethics such that never the twain shall meet? Both are about adjusting our actions to fit with everyone else’s in the everyday business of life. Economics and ethics, I contend, are two sides of the same coin, and, moreover, we can study both sides at the same time.

Since the late 1960s and the 1970s, economists have posed the fundamental question in the study of economics as a problem: “Economics,” they say, “is the study of how society manages its scarce resources,” or “how to arrange our scarce resources to satisfy as many of our wants as possible,” or “how agents choose to allocate scarce resources and how those choices affect society.”

In 1932, the British economist Lionel Robbins shifted the focus of economics from the study of wealth or economic welfare to examining how individuals make choices under conditions of scarcity. But the great Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith posits a different axiom in The Wealth of Nations: “the certain propensity in human nature . . . to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.” It is from this other self-evident starting point that he expounds upon the nature and causes of wealth of nations. Trade makes specialization possible, and together they are the cause of a “universal opulence” that “extends” to and of a “general plenty” that “diffuses” through all ranks of people.

Perhaps the human mind is the foundation for the study of economics.

What’s at stake from adopting Robbins’s axiom as opposed to Smith’s in economic science? For Robbins, the exchange of things is “subsidiary to the main fact of scarcity.” The exchange relationship between two people is “a technical incident;” it derives from its connection with scarcity.

Perhaps the human mind is the foundation for the study of economics. But must it be? Perhaps there is something else going on behind the rudiments of scarcity. Perhaps that something is the human mind. Perhaps the human mind is the foundation for the study of economics.

A meaningful economics would be about understanding human action in its origin rather than exclusively in its outcome. As a complement to the study of economic consequences, a meaningful economics would explain the roots of conduct, and not merely its economic effects, by going to the human capacity for moral sentiments that prompt human beings to act.

If there is something that almost everyone agrees on about the modern age, it’s that commerce is built on self-interest, if you’re being generous, or selfishness or greed, if you’re not. The credit or blame for the observation is almost universally attributed to Adam Smith in one of the most famous passages in economics:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

But the evidence is not there to support such a reading, or emendation, of “self-interest,” neither in Smith’s most famous passage specifically nor in The Wealth of Nations more generally. Smith says people act in “their own interest,” not their own self-interest. The difference means that the wealth of nations is not built on a disregard for others as we pursue our own interest or advantage, which is what self-interest meant in the eighteenth century and still means now.

In the very first sentence of his first great book, Smith famously sets the tone for The Theory of Moral Sentiments, saying:

“How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

There is no exception for economics, even when, or just because, we receive something in return when we truck, barter, and exchange. If economic science is about human conduct, then it is as much about purposes and human values as it is about incentives.

Featured image by CHUTTERSNAP on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 19, 2024

The concept of emotional disorder

The concept of emotional disorder

In August 2024, a special report on ‘ecological medicine’ was published in Psychiatry Online. The authors of the report describe ecological medicine as “the structured and deliberate use of connectedness and interaction with plants, animals, and other species to generate a therapeutic effect for individuals.” While few would doubt the value of spending time in the natural world, the suggestion that we need medicine to mediate our connection to nature is a striking one. Surely nothing could be more direct and immediate than the sense of awe we feel when we gaze upon the vast night sky, or the sense of renewal we feel when wandering in a spring meadow? And surely, too, it is more than just our health that is affected by this engagement; we are affected.

That the concept of ecological medicine seems to be pointing at something so familiar, and yet seems to be expressing it in such a striking and novel manner, gives us pause to reflect. How have we arrived at a point in our civilisation where it seems sensible to describe as a medical discovery the idea that “other species are worthy of respect”, and that the recognition of inter-species reciprocity that is enabled by participating in ecological medicine “serves to counteract some of the societal elements contributing to society’s epidemic of mental health problems”?

This manner of approaching our sense of connection with nature is, arguably, emblematic of a sweeping cultural trend:

We appear to be losing our grasp on ways of conceiving of human flourishing other than in medical terms.

Today, we speak of ‘mental health’, often treating this as synonymous with the notion of flourishing itself. To accept the notions of ‘mental health’ and ‘flourishing’ as synonymous with each other involves a commitment to the conjunction of the following two claims:

C1: To be mentally healthy is to flourish; andC2: To flourish is to be mentally healthy.C1 takes mental health to be sufficient for flourishing, whilst C2 takes it to be a necessary condition. C1 is the stronger of the two claims insofar as it asserts that nothing else—apart from being mentally healthy—is required for human flourishing. C2, unlike C1, allows for the possibility that there may be other conditions besides that of mental health that are also necessary for human flourishing—conditions pertaining to other domains of value such as ethics or aesthetics (domains that are of course salient in our connection with nature). But even the weaker claim, C2, imports a medical connotation into our conception of human flourishing that would have once seemed novel, perhaps even puzzling. Aristotle in the Eudaimian Ethics, for instance, takes health (like wealth or honour) to be a means by which we might come to flourish, rather than as tantamount to flourishing itself. How did this connotation appear, signalling the shift towards the medicalisation of our understanding of what it means to flourish?

Here is one story of the origin of this connotation (told by Martin Seligman, a founding father of the positive psychology movement): if (severely) distressing emotional experiences are cast as states of pathology, as contemporary psychiatry does, then it isn’t a huge leap (although it is a substantive one) from this claim to the idea that being in a state opposite to this—that is, enjoying a preponderance of pleasant emotional experiences—amounts to a state of wellness, a state of wellbeing, indeed a state of flourishing. This chain of inference is one of the major paths we have taken that has led us towards the medicalisation of our conception of flourishing. If this is right, then recovering alternate, non-medicalised conceptions of human flourishing, conceptions that might well return to us the expressive power to capture (amongst other things) our immediate connection with nature that we intuit, will involve a dissection of the concept of emotional disorder.

What, then, is the basis of the claim that (severely) distressing emotional states constitute states of pathology? From what general concept of disorder is this identification derived, and in light of what conception of our emotional lives might this identification be motivated? Surprising lines of inquiry emerge in the course of this exploration, all of which point to the pivotal role that our emotions play in the myriad ways we appraise our lives and make sense of ourselves. One particular line is worth mentioning here: it is often assumed that the medicalisation of our understanding of human flourishing signifies progress, at least in the sense that it yields an understanding that is informed by scientific knowledge. But this line of inquiry invites us to consider whether human flourishing is something we should seek to understand exclusively in scientific terms (as the invocation of the idea of progress implies). Indeed, is it something we should seek to understand in scientific terms at all? A systematic investigation of the value of emotions in human life suggests that there are visions of human flourishing that invite, indeed compel, not the detachment of the scientific gaze, but our immersion in life through the exercise of our rational agency. It is in appreciating the trade-offs between these alternative conceptions of human flourishing, and the appraisals they lead us to make of our emotional experiences, that we arrive at a clearer reflective understanding of our current predicament. It is in so doing that we may recover our power to express the immediate connection we feel with nature when we plant an acorn and tend its growth.

My aim is not to argue in favour of any particular conception of flourishing—and so I do not, for instance, claim that it is a mistake to medicalise our sense of connection with nature. It is rather to display as perspicuously as possible some of the conceptual structures that guide our ongoing quest to live happier and more enlightened lives. This quest has, for the most part, taken a very distinctive shape over the past half century: we pour billions of dollars each year into the enterprise of improving our ‘mental health’. It is ultimately for us to decide, individually and collectively, whether thinking of our flourishing in terms of the notion of ‘mental health’ is a good thing to do—rather than being, merely, something we’ve simply ended up doing.

Featured Image by Sébastien Bourguet on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Migration, colonization, and the shifting narratives of ancient Andean origins

Migration, colonization, and the shifting narratives of ancient Andean origins

In the Quechua-speaking highlands where the Incas built their empire more than 500 years ago, farmers and herders used the concept of pacha—movement across space and time—to shape local identities. They believed that their ancestors emerged onto wild landscapes in the South American Andes when the universe was created, and that they wandered until they found places they could transform for human habitation and subsistence. The first Cañaris descended from a sacred mountain in the Ecuadorean highlands; the ancestral Chancas of southern Peru followed the water flowing out of a high mountain lake. Daily tasks drew people from the here-and-now of their villages, into an ancestral tableau in which noteworthy landscape features recalled those original migrations.

The Inca nobility traced its origins to a cave located to the south of Cuzco, the imperial capital. During the mid-sixteenth century, Inca men told Spaniards of an ancient journey in which their powerful male ancestors turned to stone to establish Inca dominion over their city and its valley. Their female ancestors conquered and displaced local populations and helped to build the Coricancha, the temple-palace where the last surviving male ancestor founded his imperial house. Most Spaniards considered these dynastic stories to be factual, because Inca nobles used knotted-cord devices, painted boards, praise songs, and other memory aids to preserve oral histories.

Spaniards expressed a very different attitude when it came to the stories of universal creation that set ancestral Andean migrations in motion—they described them as fables or superstitions that were at best laughably misguided, and at worst constituted demonic misinformation that blinded Andean peoples to their true origins. Any account of universal creation that diverged from the stories found in Genesis posed a challenge to Spanish efforts to convert and colonize Andean peoples. Some of the anxiety over repeating Indigenous creation stories came from the lack of clarity regarding the origin of the peoples that Spaniards had come to call “Indians.” European Christians used biblical accounts of the Deluge and the Tower of Babel to help explain the diversity of cultures and languages that they lumped under that racialized rubric, but a fundamental question nagged at them: how did these people get to the Americas before we did?

To displace Andean creation stories and fit Native peoples into their own apocalyptic project of transatlantic colonization, Spanish writers concocted an array of apocryphal speculations. Some said that the first Indians were Phoenician or Carthaginian voyagers, while others claimed that they descended from a lost tribe of Israel or somehow originated in the mysterious lands of the Tatars or the Poles. The royal cosmographer Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa wrote in 1572 that the first Indians descended from Noah’s grandson Tubal, who settled in Spain and whose offspring peopled the island of Atlantis before moving into the Americas. In effect, that account leveraged Plato’s philosophical writings to render Native Americans as long-lost Spaniards. (Not to be outdone, the English explorer Walter Raleigh justified his search for El Dorado on the basis that the Incas—or “Ingas” as he called them—came from “Inglatierra” and were thus his own erstwhile countrymen.)

Amidst this cacophony of unfounded speculation, the Jesuit Bernabé Cobo hit much closer to the mark in 1653, arguing that “Indians” first crossed into the Americas via a yet-undiscovered land bridge from Asia. Although this speculation has proved prescient, it was built on a racialized argument that no archaeologist today would accept. Cobo devoted several chapters to reducing the vast human diversity native to the Americas into a few general “Indian” features—reddish skin, dark eyes, straight black hair, and pronounced phlegmatic and sanguine humors—that he considered similar to populations in east Asia. Cobo did more than describe phenotypic similarities, however: he claimed that both populations possessed similarly undesirable personalities, being cowardly, unreliable, and easily led astray.

Cobo’s natural history remained unpublished until the late 1800s, but a similar mix of physical stereotyping, medieval humoralism, and ethnocentrism resurfaced in the eighteenth century in the work of Carolus Linnaeus, the father of binomial taxonomy. In his Systema Naturae, Linnaeus distinguished the supposed red skin of Homo americanus rubescens (Indians) from the brownish tone of Homo asiaticus fuscus (Asians), noting supposed differences in their humoral imbalances, which made them choleric and phlegmatic, respectively. Linnaeus characterized the Indian race as governed by “custom,” and Asians as governed by “opinion.” This pseudoscientific classification helped to inspire later writers, such as the German physiologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and the American physician Samuel Morton, to collect human skulls and measure human bodies to demonstrate racial differences. In the Andes, skull collection and other racialized metrics were entangled with the earliest archaeological research—for example, when Hiram Bingham mounted his second Peruvian expedition to return to the ruins of Machu Picchu in 1912, he brought along an anatomist to measure the bodies of living Quechua people, to determine whence they had originated, and how long their ancestors had lived in Peru.

Archaeologists today reject the racial judgments that run through such work, but they continue to collect evidence about ancient migrations. Researchers now use a battery of geochemical methods to identify the origins of different kinds of pottery and stone tools, and new studies of stable isotopes and DNA from ancient human remains are adding unprecedented new data about the ways that people moved throughout and settled in the Andes. As scientific methods have improved, research practices have become more sensitive to the rights and interests of descendant populations, who continue to make ancestral claims to their local landscapes as a way to maintain identity and defend what is theirs. The increasing commitment to community engagement in Andean archaeology reminds scholars of the enduring power of narratives of origin and migration, whether they come from an oral tradition or laboratory science.

Featured image by Adèle Beausoleil via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers