Oxford University Press's Blog, page 15

October 24, 2024

Why Migrants Matter

“In Springfield, they are eating the dogs. The people that came in, they are eating the cats. They’re eating—they are eating the pets of the people that live here,” said Donald Trump during ABC’s presidential debate on September 10, 2024. His comments amplified false rumors spread by J.D. Vance, the vice-presidential nominee, who claimed that Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio were stealing and eating the pets of longtime residents. Dehumanizing and vilifying immigrants has been a mainstay in xenophobic rhetoric mobilized during elections in the US and Europe by mainstream and alt-right-wing parties alike.

Fabricated and baseless rumors about immigrants is nothing new. Like the Haitians of Springfield, the ancient Phoenicians—a Semitic population that had an extensive trade network that spanned from Assyria to Iberia—often faced negative stereotyping and prejudice. Ancient Greek sources describe the Phoenicians as wily traders and deceitful moneylenders. Even famous Phoenician immigrants suffered from such prejudice. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, one of antiquity’s most influential philosophical schools, was a Phoenician immigrant in fourth-century BCE Athens, originally from Kition on Cyprus. Although Zeno was a preeminent thinker in Athens, he was subjected to disparaging comments because of his migrant status and his Phoenician ethnicity. His teacher called him “little Phoenician,” a demeaning term. One of his biographers described him as stingy because he was a foreigner. A rival philosopher accused him of plagiarism, saying that Zeno would sneak in to listen to his lectures, steal his ideas, dress them in Phoenician style, and pass them as his own. Even after his death, one of his students wrote a funerary epigram trying to downplay Zeno’s Phoenician origin, writing: “What reproach is there if your fatherland is Phoenicia?”

If a prominent figure like Zeno experienced such discrimination, what indignities did most immigrants, who belonged to the lower classes, suffer? One political treatise from fifth-century BCE Athens complains that the notion of citizenship was eroding because immigrants and enslaved persons were indistinguishable from citizens in their looks, dress, and rights, when in fact enslaved persons had no rights and immigrants faced many legal constraints. A few decades later, several court cases dealt with similar issues. With flimsy evidence they accused the freedwoman Neaira of illegitimately claiming the rights of Athenian citizenship and alleged that Euboulides had unlawfully removed the plaintiff, a certain Euxitheus, from the citizen register. These and other texts discuss the supposed dangers posed by immigrants revealing the vulnerability of immigrant populations, even in a multiethnic city like Athens.

Such fears expressed by the more conservative parts of the Athenian population were reactions to Athens’ policies of rewarding immigrants with some or all citizen rights. Phoenician immigrants were among the non-Greek foreigners most frequently awarded with monetized gifts of gold wreaths, honorific positions, and a wide assortment of legal awards, such as the right to own property, tax exemptions, the privilege of better seats at the theater at state expense, the right to attend state-sponsored dinners alongside prominent citizens, the right to serve in the military, and even the rare grant of citizenship. Among the Phoenician immigrants who received some or all these awards was a certain Herakleides, who in 330/329 BCE had offered large quantities of wheat to Athens at a lower price and two years later donated money to Athens to help the state purchase grain, during a period of grain shortage. The Athenians eventually honored him with a gold wreath, honorific titles, the right to own property, and the privileges of participating in military service and paying capital taxes, as is recorded on a stele that survives today.

This system of award-giving was employed to attract immigrants, especially wealthy ones, like Herakleides, who could serve the state by carrying out various benefactions. Indeed, in a fourth-century BCE treatise on Athens’ revenue sources, the historian and philosopher Xenophon proposed that more social and legal privileges be given to immigrants because they would inject funds into the Athenian economy and would make Athens great again. All the legal rights Xenophon wanted to give to immigrants would allow “better” men to desire to live in Athens, where “better” stood for more useful to the state or wealthy.

This rhetoric of the good immigrants, immigrants who work hard and benefit the society in which they live, is a familiar trope today, too. Mike DeWine, the Springfield-born governor of Ohio, tried to put an end to the rumors regarding Haitian immigrants and ensuing bomb threats in schools, and hospitals. In an op-ed he wrote: “Springfield is having a resurgence in manufacturing and job creation … [in part] thanks to the dramatic influx of Haitian migrants … They are there legally. They are there to work.”

But migrants, documented or undocumented, are not just workers; they are also human beings. They mattered in antiquity, and they matter today, not because they revitalize the economy but because together with citizens they co-create and maintain the diverse societies in which they live. The Phoenician immigrants of the ancient Mediterranean introduced new ideas, such as Zeno’s Stoicism; they benefited Athens in times of need; they broadened what it meant to be a resident of a state; and they helped form multiethnic and diverse communities that thrived. While ancient Greek thought, politics, and society have been idealized, it is unlikely that they would have taken the form they did without the contributions of migrants in general and of Phoenician immigrants in particular.

Featured image by Henryy st via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

October 23, 2024

Out for lunch

Two weeks ago, I wrote about the word lump and promised to deal with lunch, but in between, following a reader’s request, I turned to east, with the intention to go on in the same vein (north, south, and west). The post on east did not reach my email. If you had the same trouble, search for “Oxford Etymologist: Light from the East.” Blinding rays will be your reward. And now I am returning to lump, that is, lunch. And for those interested in idioms: I am out for, not to, lunch.

Lunch appeared in dictionaries and books toward the end of the sixteenth century and remains “a wordof uncertain origin.” But the attempts to solve the riddle are curious and instructive. They were published in popular periodicals, most often in the indispensable Notes and Queries. As usual, the contributors to the NQ looked through old dictionaries and books, and I found nothing in my database they missed. Below, I’ll tell my story without detailed references, but to repeat: all the information in this post came from fugitive notes in journals between 1851 and 1904 and from various dictionaries.

Lunch rhymes with bunch, punch, hunch “tool,” munch, and crunch. This environment does not augur well: none of the five words has a reputable origin, and a homonym (or another sense?) of lunch “the sound made by the fall of a soft heavy body; fragment” has been recorded. Also, lunch is close to lump—another unpromising connection. Even before we make the first step, we suspect that lunch is perhaps onomatopoeic (sound-imitative). Two riddles complicate our search for the word’s origin. It is not immediately clear how lunch is connected with luncheon and with its other synonym nuncheon “refreshment, originally taken in the afternoon,” now dialectal.

A sumptuous luncheon.

A sumptuous luncheon.Image by FranHogan via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

As early as the seventeenth century, John Minsheu (1671) derived lunch from Spanish lonja “slice.” Stephen Skinner (1671), a later etymologist, had the same opinion. Minsheu’s otherwise mysterious explanation: “From the length thereof” makes it clear that he meant a big slice. The OED corroborates this conclusion and gives several citations of lunch “a piece, a thick piece, a hunch or hunk” between 1600 and 1786. Luncheon (in the same sense) occurred in books between 1580 and 1824. A contributor to NQ 1/III, 1851, p. 464, remembered “some verses of the younger Beattie [he meant the son of the Scottish poet James Beattie, 1735-1803], in which he uses the word ‘luncheon’ for the piece of bread placed beside the plate at dinner.” And Laurence Sterne, in his book A Sentimental Journey (1765), recollects how he once cut himself “a hearty lunchen” (sic). This sense of luncheon is now dead.

Time for lunch? Perhaps a bit too early.

Time for lunch? Perhaps a bit too early.Image by Florian Pépellin via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Later guesses traced lunch (among others) to Swedish luns ~ kluns “lump” (incidentally, clunch and especially cluncheon are common in some parts of England), Welsh llwnc “a gulp,” and especially to Spanish l’once “eleven” (with a definite article), allegedly pronounced as lonche, because that meal was taken at eleven o’clock. The phonetic basis of the Spanish etymology is suspicious (ch in once?). Yet the meaning fits the context. For comparison: the word bever (a homophone of beaver, still current in dialects) was explained to an uncomprehending outsider as “luncheon, a snack taken between meals,” and indeed, it was taken at eleven, even though it could also refer to an evening meal. Bever emerged long before lunch. It goes back to a French word referring to drinking (compare imbibe). As is well-known, English borrowed countless words from French, but why should lunch have a Spanish pedigree? The editor of NQ 4/IV, 1869, 118) summarized his findings so: “Obviously all these terms have sprung from a common but unknown source; and neither [sic] of them, therefore, can be said to be absolutely satisfactory…” He was, in principle, right, though few things are “obvious” in this story. Yet, as we now know, nuncheon is a so-called disguised compound (that is, we no longer recognize its components), from non(e) “noon” and shench “draught, cup” (compare German (ein)schenken “to pour”), a close contemporary of lunch.

Six years later, that is, in 1875, Walter W. Skeat, already an experienced editor of old texts but long before the appearance of the first installment of his etymological dictionary, wrote: “There was not only the term nonechenche for noon-drink, but nonemete for noon-meat, or noon-eating. The Spanish words… are hardly to the point. Mere resemblances prove little, and it is far more likely that luncheon was an extension of the provincial-English lunch, meaning ‘a lump,’ than that our labourers took to talking Spanish. The Spanish word loncha, meaning a slice of meat, not a lump of it, was suggested by Minshew [sic], and rejected by Richardson [the author of a detailed and once influential dictionary], and rightly, in my opinion.” Skeat never changed his opinion.

In 1901, the fascicle of the OED with lunch and luncheon appeared, which made letters about early and late citations redundant. Very cautiously, the OED sided with Skeat but added: “It is curious that the word first appeared as a rendering of the (at the time) like-sounding Sp[anish] lonja.” The plot thickened almost at once. In January 1904, a review of the fascicle appeared in the popular periodical Anthenæum. As usual at that time, the review was anonymous, but perhaps the identity of the reviewer is now known to the OED’s editorial staff.

King Charles II. Not everybody spoke Spanish in seventeenth-century England.

King Charles II. Not everybody spoke Spanish in seventeenth-century England.Image by John Riley, The Weiss Gallery via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

This is what was said there: “It is noteworthy that the five quotations of ‘lunch’, ‘luncheon’, earlier than 1650, are from a Spanish-English and a French-English dictionary, two translations, and a passage relating to the Netherlands… In Cotgrave’s [French-English] dictionary [1673] we find “Tronson, a truncheon or little trunk, a thick slice, luncheon, or piece cut off’; so that it is probable that the form ‘luncheon’ is due to the old synonymous ‘truncheon’. Either ‘lunch’ is short for ‘luncheon’ from Spanish ‘lonjon’, intensive of ‘lonja’ = slice (of bacon), or ‘luncheon’ is from ‘lonjon’, and ‘lunch’ for ‘lonja’. That ‘lonjon’ = thick slice does not appear in Spanish dictionaries goes for little, as their vocabularies are very incomplete.” I assume that this opinion exercised a decisive influence on later researchers. Ernest Weekley (1921) and The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (1966) supported it without discussion. However, the OED online returned, though cautiously, to the formulation, favored by Henry Bradley, the editor of that fascicle, but expunged the reference to Spanish.

This looks like a wise decision, because no one has ever answered Skeat’s question about why English laborers began to speak Spanish. Spanish did enjoy prestige at the time of Charles II, but lunch does not sound like a high society term. Though it is doomed to remaining “a word of uncertain origin,” some uncertainties are less dangerous than others. Only a few scattered remarks about lunch have appeared in scholarly publications since 1904. A final remark: truncheon “a piece broken off” has disappeared from Modern English, but lunch is all over the place, with luncheon being its formal or solemn relative. So far, so good.

Featured image by cottonbro studio via Pexels.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

October 22, 2024

Community, commerce, and open access experimentation

Community, commerce, and open access experimentation

You may have wondered why so many publishers are announcing pilot projects on open access (OA) publishing. The theme of Open Access Week (October 21-27), Community over Commercialization, hints at the reason: publishers want to engage with the community’s request for new models but can’t afford to make a loss on OA (and shouldn’t be expected to). So, the innovation challenge is taken up by means of pilots: experiments that can be reviewed and then either rejected, repeated, or adapted.

Two Innovative PilotsThis year OUP is trialling two different OA funding models. Up until now OUP’s gold OA publishing outside of journals has largely been funded by processing charges for individual books, paid for by research funders or individual institutions. The two new initiatives look to fund OA on a much larger scale via diamond OA models that OUP has adopted and refined:

Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO): Commit to Open seeks funding from the academic library community for the OA publication of 30 participating books. While other publishers have launched similar initiatives, the novelty here is our aim for radical openness:the 30 titles are announced up front. we have no minimum commitment threshold for publishing a book under an OA licence.progress will be publicized monthly. Max Planck Encyclopedias of International Law , the market-leading international law resource published by OUP, will be among the first non-journal publications to adopt the Subscribe to Open model (S2O). A range of publishers have tried out S2O with journals, where current subscribers are asked to continue to pay each year so that existing content can be made free to all, and new content is published under an OA license. So long as a high enough proportion of existing subscribers renew, the paywall is removed for a year, and then the process repeats the following year.Impact on the CommunityFor OUP, finding ways to expand our OA offering is a perfect fit with our mission. It helps us to seize the opportunity that digital distribution offers for the unlimited dissemination of scholarship. That said, we are also acutely aware that paid-for OA can present risks of lower quality thresholds, and that there is a perception that OA books in particular are in some sense lesser than non-OA books.

For that reason, each book in our Commit to Open program was carefully selected for this pilot. Each went through the same rigorous peer- and internal -review process and was slated for regular sale as part of OSO before being pulled into Commit to Open. All of them would fare very well as commercial projects but we are excited to bring these works to an even broader community of readers through the program, and we look forward to seeing how they contribute to this developing model. Another key community element of the initiative is the inclusion of authors and topics that still struggle to attract funding for OA publishing: a “Support New Voices” collection by authors who are within six years of their first academic appointment, and a Humanities collection.

In the case of the Encyclopedias, they are already the most trusted source in the field. The importance for the community here lies in the nature of the content. International law deals with highly topical issues of global justice and equality—knowledge of it has the potential to benefit students, scholars, civil society activists, and practitioners everywhere. To make such a trusted resource freely available to the whole world would represent a significant public good.

SustainabilityWhat determines whether a pilot becomes a program? As mentioned, we use pilots to answer questions of sustainability and replication. In the case of Commit to Open, it is very labour-intensive to do it the way we have chosen e.g. agreeing all of the titles upfront, and the manual processes needed to implement a novel funding model. If the pilot is successful, we will need to work out whether it is sustainable to carry it out again, whether to expand it, and what permanent systems need to be put in place to support the program.

With Subscribe to Open the challenge is a different one. Operationally it is simplicity itself—absolutely nothing changes other than that the paywall is removed, so long as renewals hold up. But therein lies the risk: the (understandable) temptation for some subscribers to wait and see and take advantage of free access.

But those are questions for further down the line. Our immediate concern is getting engagement from the community and hearing responses to these initiatives, something we are very much hoping to achieve in OA Week.

You can find out more about Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO): Commit to Open in our upcoming librarian webinar on Tuesday, November 26, 2024. Sign up here.

Featured image by Andrea Piacquadio via Pexels.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

October 18, 2024

The father of the party system

The father of the party system

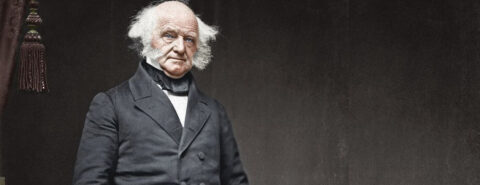

Martin Van Buren became president on March 4, 1837, at a time of great optimism. After an acrimonious eight years in the White House, Andrew Jackson was leaving office on a high note. The economy was strong and vibrant. The nation had avoided a civil war. Washington politicians were confident that “the abolitionist scourge” was in retreat. When Van Buren delivered his inaugural address before 20,000 people—nearly all of them there to pay tribute to Jackson, not to welcome Van Buren—he pledged to rule with a light touch. The nation, Van Buren said, had reached a stage where its citizens could govern themselves. They did not need Washington. He called upon the American people “to make our beloved land for a thousand generations that chosen spot where happiness springs from a perfect equality of political rights.” He used the words “happy” or “happiness” seven times in his speech.

He went on to serve for four unhappy years as president.

Weeks into his administration, the economy collapsed. Banks had run out of specie and could not redeem paper money, leaving many Americans broke. The Army brutally carried out the expulsion of the Cherokees and Seminoles from their homelands. Indian removal was not only a humanitarian disaster but a political debacle for Van Buren, whose support among northerners suffered as a result. Further weakening northern support were his frequent capitulations to the slave power. He sided with Spanish kidnappers in the Amistad case and backed efforts to suppress abolitionist literature in the mails and in Congress.

Van Buren had some successes as president. He showed courage and foresight in subduing skirmishes along the northern border that could have led to war with Great Britain. He wisely resisted those within his party calling to annex Texas. And he passed a treasury plan that moved the government away from using unstable state banks to manage the nation’s resources. Yet these victories were not enough to keep him in the White House. In 1840, Americans, for the first time, voted with their pocketbooks. He lost in a landslide to William Henry Harrison, a veteran from the War of 1812 nearing seventy years of age, in one of the most frenzied elections in US history (“Tippecanoe and Tyler too!”). Eighty percent of those eligible voted, still the highest percentage of voter turnout in the nation’s history.

Van Buren was the first of several undistinguished one-term presidents who failed to halt America’s descent into civil war. Pierce, Buchanan, Tyler, Fillmore—their names usually land at the bottom of presidential rankings. Among the antebellum chief executives, only Polk, who led the nation during the Mexican War, has won praise from some historians, although that is changing too. Few today see the Mexican War as an honorable affair.

Ranking presidents, it must be said, is a mug’s game. The practice reduces the presidency to simplistic and outdated notions of “leadership” and “character.” As a result, key moments in history are downplayed, if not ignored altogether. Van Buren served during a transitional period in US politics, when a more militant and defensive South emerged to dominate politics for a quarter century. Devoid of Jackson’s charisma and popularity, Van Buren was flummoxed by this turn of events, and his bumbling balancing act satisfied few. His presidency, therefore, reminds us of the perils of surrendering principles to a party’s worst elements.

A vibrant party system checked the forces of wealth and privilege seeking to manipulate government for private gain.

Because Van Buren was an unsuccessful president, his more significant contributions to the nation’s political life have also been obscured. His greatest legacy remains his role in building the nation’s party system (however destructive and dubious partisanship may seem today). Rejecting the Founders’ call for public officials to be “disinterested” (a favorite word of theirs), Van Buren saw parties as a positive good, a mechanism for resolving sectional disputes, keeping citizens engaged, and holding politicians accountable. Most important, a vibrant party system checked the forces of wealth and privilege seeking to manipulate government for private gain. In his unshakable view, strong parties led to sound government—and upheld the all-important principle of majority rule. His advocacy of a permanent party system led to the founding of the Democratic Party, the one still in existence today, albeit in a dramatically different form.

As Van Buren learned during his presidency and its aftermath, however, parties can serve sinister forces as well. In his time the Democratic Party became a vehicle for the expansion of slavery, the deracination of Native peoples, and imperial conquest of the West, better known as Manifest Destiny. Van Buren did not have the mettle to stand up to these forces when he was president. He found his voice in 1848, when he ran for president with the antislavery Free Soil Party, but the slaveocracy could not be stopped. Bitter and unhappy, he died in 1862, with the future of his nation very much in doubt.

The US has endured, though, and so has his party. Meanwhile, Americans are still quarreling over executive power, states’ rights, immigration, war, and economic inequality—issues dominating Van Buren’s time in politics as well. The history of our current discord is long and deep.

Featured image: Colorized portrait of Martin Van Buren from a Matthew Brady photograph. Daniel Hass, via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

October 16, 2024

Light from the East

I received a letter from a correspondent who wrote that she follows the blog and likes it but mentioned that she could not find anything in it on the four cardinal directions (points), namely east, west, north, and south. She asked if I intended to address them. I have never discussed those words because my usual aim is to say something that cannot be found online or in a good dictionary. Though my database on all four words is extensive, none of the articles contains a discovery, not known to recent lexicographers. That said, in what follows I’ll mention a few details, not entirely trivial, and check our readers’ reaction. If no one objects, I may deal with all four points.

East, like the other three terms, is an Old Germanic and even Indo-European word. By chance, a cognate of east did not occur in Gothic, the most ancient recorded Germanic language. Yet in the works of later historians, the Latin plural Ostrogothae occurred, and it was understood as “East Goths,” because those tribes did indeed occupy the eastern part of the territory ruled by the Goths. However, since the Gothic word is expected to begin with Au-, rather than O-, it has been rather plausibly interpreted as meaning “shining, brilliant” (if so, then “shining Goths”!). This display of self-admiration has no bearing on our story, except as a historical curiosity. The daughter of the emperor Theodoric the Great (the future hero of German epics; he is known there as Dietrich von Bern, with Bern referring to Verona, not today’s Bern!) bore the name Ostrogotha. She was, apparently, a shining “Lady of Ours,” as behooved an offspring of such a resplendent king. The male name Ostrogotho also existed.

A memorable tomb for a resplendent Gothic king.

A memorable tomb for a resplendent Gothic king.Image by Eulenjäger via Wikimedia Commons.

But even without the Gothic cognate, we can be certain that the root of the oldest Germanic word was aust-. Old English had ēast, an adjective and an adverb, not a noun (it meant “easterly” and “eastwards”), but in Old Norse, the noun austr did turn up. The fact that our word, regardless of phonetic differences, existed all over the map shows how early the people we call the Indo-Europeans coined it. The Germanic forms are so similar that they need no proof of relatedness. Dutch still has oost, and German has Osten. The ancient place name Ōstarrichi “eastern kingdom” is today’s Österreich “Austria.” We detect the root in Classical Greek (dialectal) aúōs “dawn” and the much more familiar Latin Aurora. The first r in Aurora need not bother us: voiced s (that is, z) sometimes became r (this process is called rhotacism). Its traces are visible, for example, in such pairs as English was ~ were and the related verbs raise ~ rear. Rhotacism affected English and many other languages, not only Germanic.

East or west….

East or west….Image by Curioso Photography via Pexels.

The words east, west, north, and south were needed for orientation and travel on land and at sea. Predictably, the guide for finding one’s way was the sun. But all those four words refer to rather abstract categories, and abstract notions usually go back to concrete, tangible ones. Strictly speaking, east applies to the point where the sun rises at the equinox, but more often it refers to the general direction, and that is why east is associated with dawn, as the names of the goddesses of dawn make clear. Aurora is the personified Dawn.

The Latin word auster has also come down to us but only with the unexpected meaning “south.” The Latin for “east” is oriens. We recognize it in orient(ation) and origin. But why south? Since Latin is in the minority here, its usage appears to have been an innovation. The cause of the new meaning can be only guessed at. Perhaps, as we read, people looked ahead and somehow confused the point at which the sun rises with the point at which it is at its brightest. Unfortunately, this explanation, though reasonable, is tautological. We are told that the speakers of Latin changed the sense “east” for the sense “south” because of reorientation. But we need the cause of the change in one particular language (Latin). Perhaps the premise is wrong. Latin auster, it should be noted, also meant “south wind.” Not improbably, the word acquired the sense “south” later. If so, it may have nothing to do with the Indo-European designation of “east” and joins the melancholy pool of words of unknown etymology.

An image of the Venerable Bede.

An image of the Venerable Bede.Image by British Library via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Austere (austerity) has nothing to do with our discussion (it has a different root), while Easter belongs to it. However, the connection is not absolutely clear. The great Old English church historian Bede (the Venerable Bede: 672/673 – 735), who wrote all his works in Latin, derived the Old English word ēastre (the plural form is ēastron) from the name of a pagan goddess Ēostre ~ Ēastre. Her feast was celebrated at the vernal equinox. Bede’s explanation contains many puzzles. To begin with, such a goddess is never mentioned in any other old text. This gap in Old English and Old High German does not cause surprise, because outside North Germanic, texts dealing with pagan mythology have come down to us in vanishingly few fragments. However, no similar name occurs even in Old Norse (Old Icelandic), though written monuments in that language contain a great number of divine names.

To be sure, Ēostre is a good match for Ēos and Aurora, and both Classical names must have been known to the clerics of the eighth century, but was there such a Germanic goddess? And why should the Christian holiday celebrating the resurrection of Christ have been called after a pagan divinity? Easter is called the same in all the Germanic languages (with the expected phonetic differences: German Ostern, and so forth). This fact does not prove that the goddess, mentioned by Bede, occupied a place in the Old Germanic pantheon. Medieval clerics worked in close contact and often agreed on the uniform terminology of the new faith across the borders. As could be expected, a different etymology of Easter has been proposed. The question is complicated, and I’ll refrain from discussing it here. Though my today’s topic is east, rather than Easter, it won’t harm anyone to know that the seemingly accepted origin of the word Easter is still debatable.

Only one short postscript is in order. The name of the Greek goddess of dawn is relevant to the etymology of east. But the Greek word for “east” (anatolē; stress on ē) has nothing to do with Olympus. It consists of the prefix ana-, which denotes “movement upwards,” and the root meaning “to rise.” Russian vo-stok “east” (stress on the second syllable; the word is perhaps still memorable from the name of the spacecraft of the Soviet era) is a morpheme-by-morpheme translation loan from Greek (such loans are called calques). Later, Anatole became a popular French name. Think of the writer Anatole France, a pseudonym for Jacques Anatole Thibault, and if you have not read his book Penguin Island, read it now, preferably before Election Day in the US. Later, the name reached Russia and became wildly popular in the middle of the twentieth century. But consider the excellent composer Anatoly Lyadov (1855-1914). The name of the handsome young man who seduced Natasha Rostova was still Anatole, not Anatoly. The Greek name of the peninsula Anatolia also belongs to our story.

Here we are with the first installment in the series East, West, North, and South. Comments are welcome.

Featured image by Adriansart via Pixabay.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

A generational divide: differences in researcher attitudes to AI

A generational divide: differences in researcher attitudes to AI

As part of our interest in helping academic researchers harness AI, we surveyed 2,300 researchers to understand their use of AI, as well as their attitudes and worries. Our findings show that a quarter (25%) of those in the early stages of their careers have reported having sceptical or challenging views of AI. However, this proportion falls to 19% among respondents who are later in their careers. Early Career Researchers also have more divisive opinions on AI, with fewer expressing neutral views than Later Career Researchers.

In a roundtable discussion we asked Dr. Henry Shevlin (Associate Director at Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, University of Cambridge) and Dr. Samantha-Kaye Johnston (Research Associate at the Department of Computer Science, University of Oxford) for their thoughts on why this might be:

Henry ShevlinThe survey findings were empirical evidence for something I have observed for some time. My dad is almost 80, and I introduced him to ChatGPT’s voice functionality. He absolutely loves it and uses it every day; he says he has had enough of typing on tiny buttons on a tiny phone screen. Now he just chats to ChatGPT every day.

So, it was really striking to me to see that the most enthusiasm (in terms of the largest number of “Pioneers”) was found in Boomers and Gen X, whilst younger generations were a lot more sceptical.

There are all sorts of theories for why that could be, but one I will explore here is an analogy with cars and mechanical skills. When I think back to my parents’ generation who got their first cars in the 1950s and 1960s, they really needed to have mechanical skills to run a car because cars were really unreliable and broke down all the time. By contrast, I can just about change the oil in my car. My car is pretty reliable and so I haven’t ever needed any more skills than this. Also, if I wanted to do anything fancy or impressive, car mechanics are so advanced these days that I would probably need to plug in a computer to get the diagnostics information.

I think we probably have seen something similar happen with the understanding of computers. For so many people these days (and particularly for young people), the primary way of accessing the internet is through a phone or a tablet. There’s far less need and far less opportunity for the kind of tinkering that my parents’ generation did in the 90s when you had to key in commands or use Boolean search. That kind of tinkering was crucial for building understanding of the fundamentals, and for giving people the confidence to experiment and learn.

We are seeing intergenerational differences in willingness to tinker showing up in the AI survey results.

These days, a lot of people try something on an LLM for the first time, find it doesn’t work as they expected or that they don’t find the output useful, and so they assume that the LLM can’t help as they needed. I think for most AI tools, there’s quite a steep skill curve because you need to spend a lot of time figuring out what questions to ask to get a reliable response.

If you approach AI tools like my parents approached cars, then setbacks like unhelpful responses are less likely to put you off. If you anticipate that tinkering and experimentation will be required (and you are confident in testing out different approaches), you will have better experiences with AI. We are seeing intergenerational differences in willingness to tinker showing up in the AI survey results.

Samantha-Kaye JohnstonIt’s important to contextualize the survey’s results within the broader concerns that Early Career Researchers tend to face—even before we consider the impact of AI. ECRs, particularly those who are non-tenured or on short-term contracts, are oftentimes grappling with the significant issues of job insecurity and work life balance. With this broader context in mind, an understanding of why Early Career Researchers might be more sceptical about the role of AI becomes quite a bit clearer.

Someone who is a Research Assistant might fear that AI could replace some of their research roles. These survey findings do show that Later Career Researchers are using AI for analysis that Research Assistants would normally take on. It’s not unreasonable for this to build on your worries around establishing yourself and getting recognition for your work.

And those aren’t unreasonable worries. If you type in “do you know this person” to an LLM (albeit, perhaps an unpaid version) then you typically won’t get responses about ECRs, unless they have already made a huge impact on your field. Many ECRs have not yet had the time or the opportunity to establish their name, nor the internet presence needed to appear in responses. The nature of citation websites is that they lead back to established researchers, to well-known studies, or to landmark papers. This means that ECRs are less likely to have been included in the data training pool that LLMs are built upon, and as people are using AI tools to discover research or summarize a research topic, then it becomes harder for ECRs to establish themselves.

What defines an excellent researcher in the age of AI?

In other cases, ECRs might also worry about being perceived as overly reliant on tools like ChatGPT, which can carry negative connotations. They may fear that this reliance could jeopardize their professional identity and credibility in the academic community because we have developed a fear-based narrative around using AI. Importantly, I think this may stem from the broader concern of not knowing when and how the use of AI will be accepted, even if there are clear benefits of using AI-driven tools.

If this is the case, and to quell fears around using AI, then I think it’s important for us to define as a community what excellence looks like when engaging with AI tools. What defines an excellent researcher in the age of AI? Is excellence characterized by seamlessly integrating AI into the academic workflow, enhancing productivity and innovation? Does an excellent researcher use AI selectively, leveraging it for specific tasks where it adds the most value? Is the mark of excellence knowing when not to use AI, maintaining a balance between human insight and technological assistance, or perhaps not using AI at all in certain contexts? Helping ECR researchers, and even more seasoned researchers, to understand these dynamics can help shape the future of AI acceptance, define what it means to excel in this evolving landscape, and reduce concerns around the role that AI plays in our academic journey—both presently and in the future.

Featured image by Tara Winstead via Pexels.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

October 11, 2024

Global mobility, bordered realities, and ethnocultural contact zones

Global mobility, bordered realities, and ethnocultural contact zones

Over the course of the last few weeks, public opinion in the U.S. and the U.K. has ignited in relation to issues of gender, race, religion, and place of origin. However, a closer look at this recent turmoil suggests that there is a clear concern regarding global migrations, inter-genetic contact zones, and the presence of Muslim communities across Western nations. During the first presidential campaign of Donald Trump in 2016, I felt the academic urgency to focus on global migrations as places of conflict and political contact, and today in 2024 this urgency has acquired a more defined intellectual and cognitive pervasion than back then.

On the surface, anti-immigration in the U.K. and the presidential candidacy in the U.S. of a woman with multiple cultural heritages that self-identifies as an African-American are unrelated and respond to different cultural anxieties. Nevertheless, global social reality provides quite a different perspective, particularly because migrations across the globe are triggering mainstream rhetorical responses that appeal to both nativism and genomic anxieties. Furthermore, the recent social media attacks focused on athletes from Algeria and China competing at the Olympics have put into question the western cultural protocols of trans-inclusion at such a competitive and global level as it is the case of the Olympic Games.

While these sociocultural phenomena seem to underscore different biopolitical trajectories (cultural difference, intersectional power dynamics, and postmodern gender re-configurations), they share a common rhetorical point of encounter. The proliferation of global bordering processes at all biopolitical levels emphasizes that our realities of interaction impose more borders than ever upon human experience. Borders no longer are mere fixed invisible divisions set under geopolitical rationales whose main objective is defining national territorialities. Moreover, the circulation of global migrants across national borders and global urban spaces has shifted the interplay between humans and borders internally. Thus, borders are not only serving as external points of biopolitical entry, particularly as cities in Europe and North America (thinking solely about the Western hemisphere) are experiencing an administrative reconfiguration of public spaces, as street policing has incorporated violent exclusionary practices to further distinguish between those who seem to belong from those who fall under the migrant/other category. In addition, public services targeting migrants are strengthening the protocols of national belonging while also defining the routes that migrants endeavor with administrative purposes, such as obtaining transit, residency, and employment permits.

Borders no longer are mere fixed invisible divisions set under geopolitical rationales whose main objective is defining national territorialities.

Back in 2016, while teaching at a very conservative liberal arts institution in the southern United States, I made the risky decision to bring into the classroom The Origins of Nazi Violence by Enzo Traverso. Traverso’s monograph rightfully maps the conflicting genealogy of the Nazi regime, framing the extermination camps as an early epitome of European modernity’s industrialization of dehumanization and killing. The reading provoked a blitzkrieg of disapproval among my students. Despite my efforts to situate the reading within contemporary ethical debates, most of them argued that Traverso’s book was dated because Nazis had been already defeated and therefore that kind of “evil” had been successfully eradicated. I clearly remember my anxiety when one of my students angrily expressed that if Traverso’s book was at all useful it was only to place the role of Barack Obama as the main culprit for constantly fueling waves of anti-white racism across the United States. From this particular vantage point, the current attacks of Donald Trump on Kamala Harris’ heritage and racial origins are not at all unfamiliar among the American electorate. These attacks have a precise epistemological origin and are also sanctioned by entire communities. Moreover, these attacks aim at very specific social and cultural places of exclusion, similarly to what Traverso exposes in relation to the Nazi regime.

Nevertheless, while there is undoubtedly an epistemic entanglement between the emergence of anti-immigration and the rejection to acknowledge the biopolitical rights of migrants, the future keeps promising more global migrations and acute social mobility. In this specific sense, a paradigmatic example of this global phenomenon is the Central America-Mexico-U.S. human migration corridor. Over the course of this new century, a shift has occurred in relation to what at some point was identified as the ground-zero level of undocumented migrations to the United States. The once regarded as dangerous Arizona desert and Río Bravo/Colorado River irregular crossing points have been replaced by the treacherous Darién jungle, which stretches across southern Panama and northern Colombia. One of the consequences of this rebordering process is the sudden amplification of global migrations to North America—as borders play a crucial role in the allocation of human rights and the redistribution of cosmopolitan ethical concerns. While people from all over the world are crossing the Darién jungle on their way to Mexico and the United States, this sudden relocation of the entry point to North America has transformed Central America into a human corridor where entire families invest their futures. In consequence, this phenomenon has transformed in a short period of time the paradigm that once characterized migrants going to the U.S. as lonely men that were often considered outliers in their home countries.

This recent “expansion” of the U.S. national border across Mexico and Central America not only fulfills the American neocolonialist agenda but also demands an ongoing administration aimed at establishing protocols for the control of human mobility. In this specific sense, although departing from a philosophical standpoint, Thomas Nail suggests the term kinopolitics as an approach to understand global mobility. In The Figure of the Migrant, Nail advances the idea that the conceptual understanding of the kinopolitical figure of the migrant underscores the multiplicity and multidirectionality of a global character, “the migrant,” that has become central in the reconfiguration of geopolitical and biopolitical borders. Moreover, Nail’s Theory of the Border proposes that everyday life is bordered in every single direction, including the human body, our mindsets, and material life itself.

Nail’s theoretical approach to both the figure of the migrant and global borders has encouraged me to wonder about the incipient emergence of global identities that in the coming years will challenge the nation-based experiences of belonging. Not only transnational experiences will become more prevalent across global spaces but also the conservative approaches to racial nationhood will be challenged by new genomic configurations inherent to global mobility. The recent Venezuelan and Haitian diasporas are already transforming the urban landscapes of global spaces like Mexico City, which is regarded as the most populous city in North America. Similarly to the ongoing disinformation campaign on social media regarding non-U.S. citizens registered to vote in the upcoming November election, during the recent presidential election celebrated in Mexico on June 2 there were also public opinion concerns regarding the false claim that South American and Haitian immigrants had been given voting cards by the ruling party MORENA, which consequently won the presidential election.

Even though anti-immigration seems to be on the rise across deeply polarized nation-states, the furthering of neoliberal postmodernity across the Global South is paving manifold routes to endeavor global migration with the clear intention to relocate as close as possible to the Global North. After all, the invisible guiding force of neoliberal postmodernity is transforming subjective, objective, and symbolic space into a spatial puzzle that could be understood as a global borderspace. And this process of spatial configuration within the global realm has positioned mobility across borders as a fundamental starting point to both access and understand the future of (inter)national borders.

Featured image by NASA via Unsplash

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

October 10, 2024

First observational evidence of gamma-ray emission in a proto-planetary nebula

First observational evidence of gamma-ray emission in a proto-planetary nebula

The gamma emission we observe in the sky through our telescopes involves a wide variety of astrophysical objects. That is why the understanding of the physical processes involved in the production of such emission requires the detailed study of objects like pulsar-wind nebulae, supernova remnants, active galactic nuclei, massive young stellar objects, X-ray binaries, and classic- and symbiotic-novae.

In particular, most of the gamma-ray emission in the Fermi-LAT 14-yr source catalogue is associated with pulsars or with blazars. However, many high energy sources remain unassociated—and unveiling their nature is quite a challenge when it comes to understanding these phenomena in depth. After ruling out possible associations with other sources, we propose for the first time that a nascent planetary nebula could be generating the observed gamma-ray emission of the Fermi-LAT source 4FGL J1846.9-0227.

A previous work towards the Fermi-LAT source 4FGL J1846.9-0227 suggested that the gamma-ray emission could be associated with a blazar; and another study, based on the presence of a massive protostar within the Fermi confidence ellipse, also proposed a possible association. However, neither of the two studies was conclusive regarding the nature of the source associated with the gamma emission. Therefore, with the primary objective of unveiling the nature of this source, we conducted a multispectral study of the region using different catalogs and observations from several telescopes like the Jansky Very Large Array (JVLA), the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), the XMM-Newton, the Spitzer, etc.

The Fermi-LAT source 4FGL J1846.9-0227 is located in a very complex region of the Galactic plane that includes several candidate sources lying within its confidence ellipse. After discarding the blazar nature of 4FGL J1846.9-0227, a multiwavelength and comprehensive study of all the candidate sources was carried out resulting in the final selection of two of them as the most likely to be generating the gamma-ray emission: a newly discovered symbiotic binary system and a likely planetary nebula with associated radio synchrotron emission. It is worth mentioning that both objects, the closest to the centre of the 95% confidence ellipse of the Fermi-LAT source 4FGL J1846.9-0227, are associated with the two brightest XMM-Newton sources in the region.

Regarding the first candidate source (the symbiotic binary system), we found a clear association between the XMM-Newton source 4XMM J184650.6-022907, whose soft X-ray spectra were well fitted by an optically thin thermal plasma model, and the spectroscopic binary star BD-02 4739 cataloged in Gaia. Our multi-wavelength analysis, which included infrared and optical data, indicated that the spectroscopic binary star BD-02 4739 is a non shell-burning β-type white dwarf symbiotic system with a sub-giant donor star. These objects are good candidates to produce gamma-ray emission under certain conditions. However, the lack of evidence of an optical nova event associated with the discovered symbiotic system prevents us from relating gamma emission to this object.

Having ruled out the symbiotic binary star as the possible source of the gamma-ray emission, we focused on the source IRAS 18443-0231, which was previously cataloged as a planetary nebula candidate. It is important to mention that we found strong evidence that this object was actually a proto-planetary nebula. The dominant radio continuum emission in proto-planetary nebulae, which is a short-lived transition (about 1000 years) from the asymptotic giant branch to the planetary nebula phase, is expected to be thermal—although some processes such as jets and magnetic fields could provide an environment for non-thermal emission. However, there are not many cases where non-thermal radio continuum emission was observed towards this kind of object.

Interestingly, IRAS 18443-0231 exhibits a bipolar morphology in centimetre radio continuum emission with a negative spectral index, compatible with synchrotron emission, suggesting the presence of particle acceleration taking place in the jets. The non-thermal radio emission in proto-planetary nebulae suggests that the emitting electrons arise at collisions between the fast and slow asymptotic giant branch winds that are observed predominantly on the front sides of the circumstellar shells. Moreover, we found a red-shifted molecular outflow arising from the central object in positional coincidence with one of the lobes, which supports the presence of jet activity, making this source the only one with strong evidence of particle acceleration in the analysed region. Additionally, IRAS 18443-0231 is associated with a water maser, which suggests that the source could be the kind of young planetary nebula known as “water fountains”.

In conclusion, based on the presence of radio synchrotron emission, the jet-like morphology at centimetre wavelengths, the presence of molecular outflows, the associated hard X-ray emission, and its location closer to the centre of the Fermi confidence ellipse, it is suggested that IRAS 18443−0231 is the most likely counterpart of the gamma ray source 4FGL J1846.9-0227. The presence of jets and molecular material in its surroundings could explain the gamma-ray emission through mechanisms such as proton-proton collisions and relativistic Bremsstrahlung. If this is the case, it would be the first reported proto-planetary nebula related to very high energy emission, and hence, multiwavelength dedicated observations and modelling would be necessary to understand the mechanisms of gamma-rays production in this kind of source. This discovery broadens the space for new kinds of gamma-ray sources to be recognized as such.

Featured image by Alexander Andrews by Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

October 9, 2024

Do you have lumps in your lunch?

Do you have lumps in your lunch?

All words are interesting to an etymologist, just as all children are supposedly equally dear to a parent. Yet especially intriguing are the words surrounded by numerous lookalikes, so that, in a way, a single etymology may cover them all. One such example was hunk, discussed in the post for September 18, 2024. An even more instructive case is the origin of lump, a word that, incidentally or not, looks a bit like hunk. While unraveling the etymology of lump, we again end up running into a host of similar forms and wonder whether their similarity should be taken seriously. Characteristically, in this case, even the most conservative sources hint at symbolism (I, of course, refer to sound symbolism all the time).

A few lumps of sugar of unknown origin.

A few lumps of sugar of unknown origin.Image by jackmac34 via Pixabay.

According to our records, lump first surfaced in an early fourteenth-century (that is, Middle English) poem, and there it already meant what it means today. We may probably assume that the word did not exist in Old English (or if it did, it failed to turn up in any of the extant texts). The word does not look like an import from Romance. Hence, the predictable conclusion is that it was borrowed from a neighboring Germanic language, such as Dutch or Scandinavian. The problem is that words like lump are numerous, and it is hard to decide whether we are dealing with similarity or affinity. Consider clump (evidently borrowed, but an Old English cognate existed), hump (discussed last week), bump (possibly from Scandinavian), dump (imitative?), thump (imitative), stump (imitative?), rump (borrowed?), and plump (borrowed). As we can see, none of them are early, and few seem to be native. Only trump does not belong to this group: it is an alteration of triumph; thus, an artificial formation. We probably have enough reason to believe that lump, wherever it was coined, is a word of symbolic origin.

Tony Lumpkin.

Tony Lumpkin.Image: John Quick as Tony Lumpkin in “She Stoops to Conquer” by P. Audinet and S. De Wilde via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

German dictionaries do not know much about the etymology of Lumpen “rag,” a close relative of English lump. Quite possibly, it reached today’s German from its Low (northern) German neighbor. Dutch lomp means the same and is equally obscure. But just as hunk seems to be related by ablaut to the German verb hinken “to limp,” lump is related to Old English (ge)limpan “to happen, occur, exist” and amusingly (considering the post referred to above), to Middle High German limpen “to limp.” Our story of hunk, it will be remembered, began with limping. The Scandinavian look-alikes appear to have the same northern German source. Yet not all the recorded senses match well. They begin to belong together only when we remember that the basic verb (ge)limpan meant “to happen.” Obviously, an event may have a good or a bad outcome. Though limping is not good, the Old High German verb (gi)limphan (gi– is a prefix) meant “to be proper,” and its modern cognate (the adjective glimpflich) also has positive connotations. Oliver Goldsmith knew why he called the rash but endearing protagonist of his comedy She Stoops to Conquer Tony LUMPKIN. Lumps, we should admit, are ambiguous.

Every time we deal with the origin of a common word, the ghost of s-mobile (movable s, an erratic, unpredictable prefix) rises to haunt us. Perhaps lump is related to slump? Slump was mentioned above and dismissed as perhaps imitative or borrowed. But there also is English slim, whose oldest form ended in b or p (Old High German slimb “crooked; slanting”). Today, German schlimm means only “bad.” Lump, limp, slimb… We also know that words with m and n in the middle may have cognates without those nasal infixes. Consider Latin fingo ‘to form, produce’, whose past participle is fixit. English lap, as in lap up, goes back to Old English lappian. Any connection with lump? Latin lambere, Greek láptein, and French laper mean approximately the same but may be independent imitative words.

It follows that lump enjoys an ambiguous status. As far as English is concerned, it is rootless. Yet it is surrounded by a well-adjusted similar-looking etymological crowd. Though ragtag and bobtail they all are, in some way, they may belong together. Semantic bridges can be drawn between practically any two words (concepts), given enough intermediate stages. Long ago, it was noted that such a process may, with some effort, connect “inkwell” and “the freedom of will.” One temptation is to rely on the entire web surrounding a word, and the opposite approach advises us to exercise caution. Words certainly interact and have always interacted, but for an etymologist it is hard to know where to stop. Most likely, lump is a rather arbitrary creation, whose structure (for some reason) suggests something compact but shapeless. Tony Lumpkin (note the diminutive suffix) may have been such a capricious but steady creation. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (1966) begins the entry on lump with the verdict: “Of unknown origin.” Perhaps this conclusion should be modified, even if slightly.

Haven’t we also been invited to lunch, another suspicious relative of lump? Yes, indeed. Wait until next week. Since the paucity of comments and questions I receive made me abolish monthly gleanings, I’d rather answer the few questions I have right now. To a few letters I have responded privately.

◄ What is the origin of hunky-dory? The Japanese origin of this word has been suggested many times, and the literature on hunky-dory need not be reviewed here. I’ll only quote without any changes part of the most recent note I have in my database: “During the years following Admiral Perry’s opening Japan, many ships stopped at Japanese ports and the sailors on shore leave trooped into the town and up into the surrounding hills looking for entertainment and perhaps companionship of sorts. The problem was how to return to the ship: having negotiated soberly the branching of narrow streets into narrower passages in the distant reaches on the outward trip, the return trip in an alcoholic fog was less certain. Nonetheless, once one reached the main street all was well, for that led straight to the wharf in many of the coastal towns, and Yokohama [see the header] in particular. The street in question is, of course, honcho dorii, or ‘main street’.” (Verbatim XIII, 1987, p. 12.) A similar etymology (folk etymology?) has been offered before. The competitive explanation returns us to Dutch hunk.

Our British friend moggy.

Our British friend moggy.Image by George E. Koronaios via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

◄ Moggy, a British word for “cat.” Of the several etymologies of moggy, the one deriving the word from mongrel is so unlikely that it should be discounted, while the derivation from a proper name (Maggie) is plausible. There is also a good precedent. From the opening scene of Macbeth, we know the word Grimalkin, that is, “gray Matilda.” Grimalkin, a witch, was a cat. Using personal names for animals and outcasts is common. Think of tomcat. Molly (Mary) is a widely used word all over Great Britain for various disreputable creatures, including prostitutes and scraggy animals. Hence Molly, the titular heroine of Defoe’s Moll Flanders. Moggy may well be a variant of Maggy. Such variants are hard to account for. Margaret becomes Peggy, Robert is Bob, while John and Jack are interchangeable.

◄ Don’t miss the comments on the idiom it is raining cats and dogs (the post on bootless cats, September 25, 2024) and the note on macaroons, following the most recent post on macaroni.

Featured image via Pixabay. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

October 2, 2024

Clowns, laughter, and macaroni

Clowns, laughter, and macaroni

My studies of medieval literature and folklore made me interested in tricksters, clown, jesters, and all kinds of popular entertainers. At least three essays in the Oxford Etymologist column bear witness to this interest: Clown (August 31, 2016) and Harlequin (September 16 and October 14, 2020).

The origin of Harlequin is now known, while clown partly languishes in limbo. Among other things, it remains a puzzle how clown has conquered half of the world. As a general rule, words travel with “things.” The street theater of late medieval Italy was popular in many countries, and that is why we know such words as buffoon (opera buffa “comic opera”), zany, scaramouch (Molière’s Scaramouche), Punch, and Harlequin. Harlequin has solid Germanic and even English roots but was made famous by Italian comedy. But how did clown transcend England’s borders? What itinerant companies spread its fame? The Italian word pagliaccio “clown” has more or less remained at home despite the fame of Leoncavallo’s opera Pagliacci. Against this predominantly Italian background, clown looks like a solitary guest from Germanic and English, and as noted, the origin of this word, to use the polite jargon of professional etymologists, remains debatable.

Most words mentioned above were recorded relatively late. Though they denote comedians, their names had nothing to do with witticisms in our sense of the word. Clowns provoked laughter by finding themselves in improbable situations. They paraded long noses, wore bizarre clothes, fell head over heels, pretended to have accidents, and when they were not mimes, indulged in obscenities. Medieval people also laughed in triumph at the sight of a vanquished enemy. That is why the words humor and witty have such unexpected origins. Witty means “having wits,” while humor refers to a liquid in the body (compare humid). The situation had to be incongruous, in order to be amusing. Even Shakespeare’s humor is still rude. Oscar Wilde, however earnest, would have had no success if transposed to the past.

Macaroni? No, Weimar

Macaroni? No, WeimarImage by Susanlenox via Flickr. Public domain.

I needed this long introduction to approach the subject of the forgotten word macaroni “dandy.” Those late eighteenth-century fops were perfectly ridiculous, but unlike such words as dandy, masher, and dude, macaroni (not the food, but the appellation) has an obvious origin, except for why macaroni? The appellation, as explained everywhere, goes back to the Macaroni Club, whose members introduced Italian macaroni (I mean the food) at Almack’s (the name of several fashionable clubs). Among other things, that establishment presaged, rather obviously, many clubs popular in the Weimar Republic and are reminiscent of today’s drag culture. All things that came from abroad enjoyed popularity among those affected busybodies. Foreign meant “great.” People’s tastes and predilections change slowly, but it must amuse us that macaroni happened to share the status of something exquisite and fashionable. However, there is a hitch. The word macaron or macaroon “blockhead; buffoon; fop” antedates the popularity of the club.

Merry Andrew.

Merry Andrew.Image by W.J. Taylor and M. Laroon, Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons. CC by 4.0.

The connection between the coxcombs of long ago and macaroni cannot be questioned, but one point needs clarification. The idea, as we have seen, is that in the beginning the macaroni members of the fashionable club chose to call themselves macaroni because of their predilection for this food. And here I have some doubts. Let us see what Joseph Addison wrote in The Spectator, No. 47 (178/2), Tuesday, April 24, 1711, that is, more than half-a century before the emergence of the Club:

“In the first Place I must observe that there is a Set of merry Drolls whom the Common People of all countries admire, and seem to love so well that they could eat them, according to the old Proverb: I mean those circumfareneous [traveling from place to place, from market to market] wits whom every Nation calls by the Name of that Dish which it loves best. In Holland they are called Pickled Herrings; in France Jen Pottages [sic]; in Italy Maccaronies [sic], and in Great Britain Jack Puddings. These merry Wags, from whatsoever Food they receive their Titles, that they may make Audiences laugh, always appear in Fool’s Coats, and commit such Blunders and Mistakes in every Step they take, and every Word they utter, as those who listen to them could be ashamed of.”

Still earlier John Donne wrote in one of his satires: “I sigh and sweat / To hear this Makaron [sic] talk.”

The German Hanswurst.

The German Hanswurst.Image via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

The explanation in bold is unnecessary, but Addison’s statement is usually disregarded, because, allegedly, the word maccaronies never existed in the sense he attributed to it and because the Italian word is maccheroni. The second objections is irrelevant, but the evidence of Donne and Addison cannot be shaken off too easily. A correspondent to Notes and Queries (7/VII, April 13, 1889, p. 298) wrote: “I find in such an ordinary book of reference as Graglia’s ‘Pocket Dictionary’, besides ‘maccheroni, a sort of pastemeat’, un maccherone ‘a blockhead’; also maccheronea, macaronicks.” The reference is accurate (I checked it), and Addison’s train of thought deserves attention. Clowns were supposed to be (pretended to be) abnormally fat and arouse laughter. This is certainly true of the German Hanswurst, Hans Wurst (“Hans Sausage”), who, five hundred years ago, appeared in front of the audience, the very picture of obesity. He was a near-contemporary of the English Jack Pudding. As already noted, those spectators had a rather primitive sense of humor. Real humor is contemporary with the emergence of metaphorical thinking. Mocking people for their food has always been people’s favorite entertainment. Someone eats macaroni, others eat frogs, still others gorge themselves on pumpernickel. So funny!

Therefore, I would like to suggest that macaroni existed as an ethnic slur and perhaps as a euphemism for “penis.” When a group of Londoners founded the club and proclaimed (rather than chose) macaroni as its favorite dish, they might use macaroni in defiance of the word’s opprobrious sense, to stress their “otherness,” as we would today say. No one has seen their earliest menu cards, even if later they began to live up to their name. The quotation from The Scots Magazine for 1772, reproduced by Gerald Cohen in 2017, says that macaroni “was imported by our connoscienti in eating, as an improvement to the subscription-table at Almack’s. In time, the subscribers to those dinners became to be distinguished [sic] by the title of Macaronies.” In time! It does not look as though the impulse for the club’s name came from the food. Rather, the association appeared in retrospect. Obviously, all this is mere guessing.

That history is forgotten, and only a British song ridiculing an American country bumpkin who wanted to look like a London swell is its reminder: “Yankee doodle went to town / A-riding on a pony. /Stuck a feather in his cap / And called it macaroni.” And we also have macaronic verse (a mixture of native and Latin words; any bilingual mixture of this type in poetry), another invention of the late Middle Ages. Macaroni seems to have always evoked laughter, a fact that may perhaps boost my guess that the word macaroni once had an opprobrious meaning. But the Greek jester Maccus has nothing to do with our story.

Featured image by I.W., Metropolitan Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons. CC0 1.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers