Oxford University Press's Blog, page 16

October 1, 2024

Five spooky story collections to keep you up this Halloween [reading list]

Five spooky story collections to keep you up this Halloween [reading list]

We all know Poe (though Eurovision fans might ask “Who the hell is Edgar?”). We’ve all heard of M.R. James and his wide range of ghost stories (watched The Haunting of Bly Manor yet?). We all love Lovecraft (unless you’re squeamish about tentacles).

But are we neglecting other authors just as capable of keeping us up at night? For centuries, writers have delved into the spooky and strange, the unusual and uncanny, the horrifying and heinous. Their stories deserved to be remembered too.

To celebrate the scariest day of the year, here’s five short story collections to widen your Halloween reading:

1. The Wendigo and Other Stories by Algernon Blackwood, edited by Aaron Worth

1. The Wendigo and Other Stories by Algernon Blackwood, edited by Aaron WorthTake this as your sign to never go camping in the Canadian wilderness. Or canoeing in Europe. Or on a tropical holiday to Egypt. Best to just stay inside with a copy of Algernon Blackwood’s greatest horror stories, their locations taken from Blackwood’s varied, whirlwind life and distorted into nightmarish borderlands. Enter at your peril…

Read: The Wendigo and Other Stories

2. The Virgin of the Seven Daggers and Other Stories by Vernon Lee, edited by Aaron Worth

2. The Virgin of the Seven Daggers and Other Stories by Vernon Lee, edited by Aaron WorthEver heard the saying “the past always comes back to haunt you?” It rings very true in Vernon Lee’s, aka Violet Paget’s, frightening short stories. Whether a haunted portrait, a long-dead poet’s lock of hair, or even a ghostly opera singer’s voice, the past is a lurking presence in all of Lee’s words. And digging it up might prove her character’s dooms.

Read: The Virgin of the Seven Daggers and Other Stories

3. The Great God Pan and Other Horror Stories by Arthur Machen, edited by Aaron Worth

3. The Great God Pan and Other Horror Stories by Arthur Machen, edited by Aaron WorthBefore Lovecraft there was Machen, a Welsh writer inspired by the Pagan ruins and misty forests surrounding his hometown Caerleon. His stories explore the unknown and unknowable, including “The Great God Pan” and his wicked daughter Helen Vaughan, the twisted, supernatural cult of “The White People”, and the tales within a tale told by “The Three Imposters”.

Read: The Great God Pan and Other Horror Stories

4. Gothic Tales by Arthur Conan Doyle, edited by Darryl Jones

4. Gothic Tales by Arthur Conan Doyle, edited by Darryl JonesYes, the creator of Sherlock Holmes also loved his horror! His “Gothic Tales” are some of the greatest put to paper. Try “The Case of Lady Sannox”, a story of deception and gory revenge. Or maybe “The Silver Mirror”, in which visions of a past murder haunt an innocent accountant. If you’re a fan of Conan Doyle’s mysteries, give his “Gothic Tales” a try this Halloween!

Read: Gothic Tales

5. Green Tea and Other Weird Stories by Sheridan Le Fanu, edited by Aaron Worth

5. Green Tea and Other Weird Stories by Sheridan Le Fanu, edited by Aaron WorthWith wonderful titles like “The Ghost and the Bonesetter” and “Wicked Captain Walshawe, of Wauling”, you know you’re in for a treat with this Irish author’s weird short tales. Don’t miss out on his most famous story, “Carmilla”, said to have inspired Bram Stoker when writing his own vampiric creation.

Read: Green Tea and Other Weird Stories

If you’ve enjoyed our recommendations, why not check out our full Halloween Reading List on Bookshop?

Bookshop UK Bookshop USFeatured image by Mathew MacQuarrie on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

September 30, 2024

An introduction to migration in the ancient world [interactive map]

An introduction to migration in the ancient world [interactive map]

Migration has played a vital role in shaping human history and continues to have profound effects on the world today. Historically, the movement of people across regions has facilitated the exchange of ideas, technologies, and cultures, leading to significant advancements and the enrichment of societies. The Silk Road, a network of trade routes connecting Asia with Europe, not only enabled the exchange of goods such as silk and spices but also facilitated the spread of religions like Buddhism. Similarly, the spread of the Islamic Empire across North Africa, the Middle East, and into parts of Europe brought about a flourishing of science, philosophy, and architecture, as well as the blending of diverse cultures and knowledge. Migration also occurred through slaverly, and as a result of warfare and oppressive rule.

This autumn, the OUP Classics and Archaeology team will be exploring migration across the classical world, sharing author insights on the OUPblog, and highlighting articles and chapters from our online products, which you can access through your institution. Discover recommended reading on migration in the ancient world with our interactive map.

Featured image by Alexis Antione via Unsplash. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

New Jerusalem to Blue Jerusalem: radical visions of Britain’s postwar future

New Jerusalem to Blue Jerusalem: radical visions of Britain’s postwar future

The last verse of William Blake’s epic poem written in 1804 reads:

I will not cease from Mental Fight,Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant Land.

Based on the theme of the Book of Revelations and its description of the Second Coming, it asks whether Jesus ever visited England and thus, for a brief moment, created Heaven on earth, while also imploring its readers to create an ideal society today.

Set to music by Sir Herbert Parry in 1916 as the hymn “Jerusalem”, today it is associated with a conventional, even establishment, idea of Englishness—hence being belted out at weddings, England cricket matches, and the last night of the proms. Yet, for much of the twentieth century, the hymn was the great anthem of British socialists in general and the Labour Party in particular. Blake’s revolutionary call to build a new City of God (Jerusalem) was an inspiration and rallying cry for generations of activists who dreamed of a more humane, equal, and cooperative commonwealth rising out of the wreckages of capitalism and the industrial revolution (these ‘dark satanic mills’).

Arguably, no one is more closely linked to this vision, than wartime Labour leader and Prime Minister between 1945 and 1951, Clement Attlee—who insisted “Jerusalem” be sung at his funeral. Winston Churchill’s deputy during the Second World War, Attlee and the Labour Party romped to victory at the postwar 1945 General Election promising to turn Blake’s vision into a reality and build a New Jerusalem out of the rubble of war. Some of Labour’s iconography at the Election literally depicted a new ‘city on a hill’ which Labour would build.

This vision of a New Britain—where the chaos of capitalism would be replaced with socialist economic planning, the fear of ill-health and unemployment with a universal welfare state, slums with new towns, Empire with Commonwealth, competition with amity—was what Labour sought to create during its 6 years in power after war. While, of course, the Attlee governments never lived up to their utopian promise, many of the institutions that they put in place—such as the National Health Service—and the changes they made to Britain’s position in the world—such as Indian independence and the formation of NATO—arguably set the scene for much of the rest of Britain’s postwar history. Not for nothing did Attlee introduce his Party’s manifesto at the 1951 General Election by telling his activists that they were ‘a great crusading body armed with a fervent spirit for the reign of righteousness on earth’ and that they should continue to ‘go forward in this fight in the spirit of William Blake’.

Yet, Labour were not the only radical thinkers and planners during the Second World War. Nor was the future that Attlee built for Britain the only one available. Rather, during the war, Conservatives developed their own set of radical, even utopian, ideas for the future of Britain and the postwar world. From dreams of world government to visions of workers going ‘back-to-the-land’ via their preference for developing a ‘warrior welfare state’ designed to properly reward those in uniform, Conservatives had their own dreams of a ‘Blue Jerusalem’—blue here a reference to the colour most usually associated with the Conservative Party. Equally, Labour activists and politicians were not alone in basing their plans on the creation of a more Christ-like polity and society—something sometimes forgotten in today’s largely secularised political parties. Conservatives too sought to use the Second World War to build their own vision of a new Christian Civilization. The most significant element of the Conservative Board of Education President R. A. Butler’s Education Act (1944) was not the raising of the school-age or even the formalisation of Britain’s tri-partite education system, but the fact that for the first time in British history, State compelled Christian religious education.

Conservatives were not at all happy about the kind of Britain that Labour was pledged to build in 1945—something which, contrary to much of the literature, did not emerge out of the way Britain was governed during the war but which was radically different to it. Instead, a wave of depression swept over much of the Conservative Party in 1945—the other type of ‘blue’ in Blue Jerusalem. Revealed in the thousands of letters sent to Winston Churchill after his defeat in in 1945, these writers described in often acute detail how the removal of Churchill and the election of a Labour government left them ‘depressed’, ‘despairing’, and ‘grieving’ for a Britain and a British Empire that they believed the Conservative Party had built up during the war and which Labour was intent on destroying; one vision of a new society giving way to an altogether different one.

Featured image by Levan Ramishvili via Flickr. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

September 29, 2024

The hidden language of crosswords

The hidden language of crosswords

I got a book of New York Times crossword puzzles, edited by Will Shortz, as a gift. I had never been a crossword addict or even an aficionado, but a gift is meant to be enjoyed, so I began working through the puzzles in the evenings as I watched the news.

It was fun and a bit of a challenge. Some clues required common, less common, or even esoteric knowledge, like:

Ark builder (4 letters)

Marilyn Monroe’s real first name (5 letters)

1960 chess champion Mikhail (3 letters)

Hawaii’s state bird (4 letters)

I knew NOAH because pretty much everyone does. NORMA I remembered thanks to the Elton John song “Candle in the Wind.” My misspent youth playing chess gave me Mikhail TAL, the magician of Riga. I had to look up Hawaii’s state bird, the NĒNĒ, or Hawaiian Goose. It’s fine to look stuff up, I learned. And I noticed that macrons and other diacritics are ignored in puzzles, as are apostrophes and hyphens.

Some other interesting linguistic patterns caught my attention too. Clues draw on a range of vocabulary knowledge, both hifalutin and lowfalutin:

Kiddy coop (6 letters)

Zilch (4 letters)

Big to-do (6 letters)

Call bad names (6 letters)

Slangy denial (4 letters)

Giggle, for example (5 letters)

The, grammatically (15 characters)

There are some tricks, of course: when puzzle clues use an abbreviation, that’s a signal that the answer is an abbreviation. There are fill-in-the-blank answers, some requiring a phrase rather than word. And when a place in another country is used, that signals a foreign word or phrase.

Code-braking org. (3 letters)

“_____ luck!” (5 letters)

“Put ___ good word for” (3 letters)

Nap, in Oaxaca (6 letters)

Most puzzles have some kind of theme that may manifest itself in the longest clues. A puzzle about relaxing had the clue:

Flops down (13 letters)

Some clues are efficient enough for puzzle-writers that they turn up a lot from puzzle to puzzle:

Midway alternative (5 letters)

Poker payment (4 letters)

Thin Man dog (4 letters)

Ukr. Or Lith., once (3 letters)

What especially caught my interest linguistically were clues that drew on ambiguity. Some ever so gently guide you in a false direction with clues that can go in several ways. For example, “blubber” might be the noun FAT or the verb CRY, and “restaurant handout” could be TIP or MENU depending on whether the server is the hander or handee. If your mind gets stuck in one direction, it may take you a while to find the right path. “Looker” turns out to not have to do with looks; the answer was EYER. “Right-leaning” has nothing to do with politics. The answer was ITALIC, as in the font. I wanted “Animal House” to be FRAT, but it turned out to be ZOO. And I was stumped by “Heel” until I got enough crossing letters to realize it was CAD rather than something anatomical.

Thinking my process through has helped to up my crossword game and to enjoy it even more. My nightly goal is to finish before the news is over.

And if any of the unanswered clues above have stumped you, here are the answers: PLAYPEN, NADA, HOOPLA, REVILE, NOPE, TEHEE, DEFINITEARTICLE, NSA, LOTSA, INA, SIESTA, TAKESALOADOFF, OHARE, ANTE, ASTA, and SSR.

Featured image by Ross Sneddon (@rosssneddon) via Unsplash

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

September 27, 2024

A new queer world: how poetry remade gay life [long read]

A new queer world: how poetry remade gay life [long read]

In San Francisco and Boston after the Second World War, gay and lesbian poets came together to build a new queer literature and a new queer world. They came together both as activists and as poets. When activism failed, or visibility was denied, poetry provided a through line with a deeper and longer sense of queer history, real or imagined, from Whitman to Wilde, Sappho to Gertrude Stein. The underground status of early queer activism was matched by the DIY publishing ethos of the poetic avant-garde associated with the ‘New American Poetry’, an umbrella term for a diverse set of writers brought together in a famed anthology edited by gay San Francisco writer and editor Donald Allen. Passed from hand to hand, smuggled into bookstores or in private mailing networks, the semi-samizdat activity of little magazines, small press pamphlets, and beautiful letterpress editions matched the distribution models of early gay and lesbian publications like One and The Ladder.

It was a poet who published the first public coming out essay in modern American letters. Written by poet, anarchist, and esoteric scholar Robert Duncan,’ ‘The Homosexual in Society’ appeared in 1944 when he was in his mid-20s. The poem was more a universalist critique of upper-class white gay male identity than it was a simple affirmation, using sexuality to challenge the established order of capitalist society, and this radical strain was essential to the work of the poets among whose Duncan’s work was central. Duncan was part of the self-declared ‘Berkeley Renaissance’, a group of anarchists, bohemians, and activists in California. Duncan and fellow poets Robin Blaser and Jack Spicer rubbed shoulders with a young Philip K. Dick and anarchist theorist Paul Goodman, as they created their own vision of a queer poetry that would reinvent ideas of love, sexuality, and human society.

Over in Boston, these poets had links to the so-called ‘‘Occult School’’, another group of gay poets who ha’d emerged amongst the scenes of sex work, bohemia, and queer love on Beacon Hill, a neighbourhood under early threat of gentrifying destruction. Circulating among queer bars, on the fringes of academia, and in the radical collective education experiment of Black Mountain College, poets John Wieners, Stephen Jonas, Ed Marshall and Gerrit Lansing gathered around queerness, magick, Aleister Crowley, and jazz. They produced their own magazines, reading groups, and ‘magic evenings’, reading and living poetry in an atmosphere of underclass solidarity, in the face of the police and the mental health institutions that sanctioned medical torture such as electroshock therapy. As the ‘50s became the ‘60s and the great social movements for race, sexuality, and class grew, some died, some disappeared, some kept writing.

At Howard University, Judy Grahn participated in the Civil Rights movement and discovered lesbian feminism when her teacher, Nathan Hare, showed his students the lesbian magazine The Ladder as an example of comparative activism. Moving to the Bay Area, where Hare had helped set up the first Black Studies department in the country on the back of student activism, she and others were involved in solidarity actions for the Black Panthers and consciousness raising groups, out of which emerged Bay Area Women’s Gay Liberation.

As it had for the gay writers of the Berkeley Renaissance, poetry proved central to the emerging lesbian movement. Grahn’s ‘The Common Woman Poems’ were printed and bootlegged on fridges, tacked to walls, and handed out on the streets. In this era, it was poems as much as speeches, manifestos, or novels that provided the movement with its theory and its practice. The Women’s Press collective, and gay magazines like Gay Sunshine in San Francisco and Fag Rag in Boston published with an open, anarchist-leaning focus. Anticipating the abolitionist goals of today, in 1972 Fag Rag presented a radical list of demands to the Democratic National Convention including prison abolition, the disbanding of the military, and recognition of gender fluidity.

Poetry and poets were at the centre of community-building institutions, whether through small presses such as Kitchen Table Press, through public readings or private discussions. The African American socialist feminist group Combahee River Collective pioneered intersectional analyses, organising around serial murders of Black women in Boston, with the support of Audre Lorde, who came down from New York and wrote her great and moving poem ‘Need’ in support. Lorde’s ‘sister love’ Pat Parker spoke out firmly in San Francisco. Good Gay Poets, the small press associated with Fag Rag, published the first book by an out gay Black male poet in the States, Adrian Stanford’s criminally ignored Black and Queer, alongside work by Combahee associate Stephania Byrd and Native American poet-activist Maurice Kenny.

As with the Civil Rights Movement from which it emerged, as queer institutions achieved mainstream success and legal gains, the emergence of a middle-class and of those in positions of power too often overlooked those from whom the movement had grown: the grass roots, the underclass, the poets, the junkies, the homeless. Poetry was a place for them to have a voice, against respectability politics and against selling out. In Boston, Fag Ragger Charlie Shively symbolically burned his bible, his Harvard degree, and his insurance card at a protest against the homophobia of the church and state. In San Francisco, the White Night Riots broke out after the murder of Harvey Milk, providing a symbol of resistance as the cultural backlash against a decade of gains from feminism, Black Power, and gay liberation, set in under the new cowboy president Ronald Reagan. Poets were at the centre of coalition-building efforts such as the Left Write conference in San Francisco, which brought together writers from diverse communities to challenge the rise of the far right.

In the midst of all this, the community was hit by a fresh crisis. At first little known or understood, the spread of HIV-AIDs gave weight to the Reaganite backlash and exposed the sharp divisions of healthcare provision that marginalized communities have always suffered. As AIDS became inescapable, poetry reflected the crisis, giving vent to what Douglas Crimp famously described as the twinned goals of “mourning and militancy”. Poetry (as well as song) testimonies became a central way for the community to gather and reflect at the all-too-frequent funerals and memorial ceremonies. In a recent book, poet Pamela Sneed describes her role as what she calls a “funeral diva” seeking to remember the dead and to inspire, exhort, and comfort the living. Bruce Boone, one of the co-founders of the San Francisco queer writing tendency known as ‘New Narrative’, worked as a carer at the Zen AIDS center run by Zen master and former drag queen Issan Dorsey.

As the joyous momentum of the gay liberation era was lost, others sought to retain the transgressive edge of early activism. Another New Narrative writer, Robert Glück was involved in the first act of civil disobedience against the government’s handling of AIDS. This action emerged from the Affinity Group movement of non-violent civil disobedience against the arms industry and the military industrial complex. Blockading the road near the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a nuclear weapons research lab, the Enola Gay Faggot Affinity Group—punningly named for the plane that dropped the A-bomb on Japan—staged a ‘Blood and Money‘ ritual, pouring blood on the road and chanting “money for AIDS, not war”. New Narrative writers wrote some of the great books of the AIDS era: Dodie Bellamy uses the metaphor of the vampire alongside cut-ups and snapshots of bohemian life in San Francisco in her Letters of Mina Harker; Kevin Killian’s Argento Series stages the pandemic through the giallo movies of Dario Argento; Glück’s own recent About Ed memorializes his former partner, the artist Ed Aulerich-Sugai, ending with an astonishing fifty-page sequence constructed from years’’ worth of Ed’s dream journals.

It’s easy to say that, now AIDS is relatively under control for white middle-class gay men, we have entered a new era. But, while these gains are very real, they are unevenly distributed. Today the victims of AIDS are overwhelmingly the poor and people of colour in the States, and across the African continent. The Military Industrial Complex continues apace, in bloody wars and the provision of arms for dictatorships and corrupt governments worldwide, as the Cold War positions of the past fifty years reassert themselves in new form. The poets of the past, and their inheritors today, refuse to be misled by superficial gains, producing writing that continues to remind us of the costs and inequalities of gay liberation. We live in a world of staggering inequality, an inequality revealed by the uneven handling of the Covid pandemic, and by the concentration of the majority of the world’s wealth in an ever-smaller percentile of the world’s population. The queer- and trans-phobic backlash in the United States continues apace as books are banned and the battleground shifts from the discourse of sexuality to that of gender, a replay of the old culture wars fought in the Reagan Era. Meanwhile, cities so central to gay liberation literature like Boston and San Francisco, have been transformed almost beyond recognition, with the surging wealth of big tech—and its ties to the Trumpian right—occurring just a few kilometers away from the worsening effects of the opioid crisis.

As gentrification continues to alter the communities and neighborhoods from which activism emerged almost beyond recognition, the poetry of the Berkeley Renaissance, the Occult School of Boston, Fag Rag, the Combahee River Collective, New Narrative and so many more accesses a different timeline, a different way of looking at history, a different embodiment of what it means to exist and to fight for another world. This poetry is no historical relic but a guide for how to survive and a spur for how to fight in the present.

Featured image by Roger W. via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

September 26, 2024

The creation of the US presidency

The creation of the US presidency

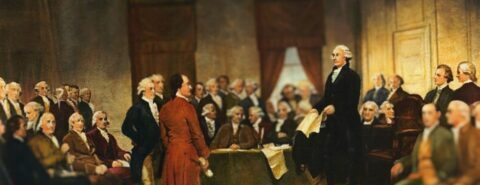

At no time in our history has there been so illustrious a gathering as the corps of delegates who came together in the State House (Independence Hall) on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia late in the spring of 1787 to frame a constitution for the United States of America. Yet, distinguished though they were, they had only the foggiest notion of how an executive branch should be constructed. Not one of them anticipated the institution of the presidency as it emerged at the end of the summer.

One frightful goblin haunted their deliberations. The study of history—ancient to modern—instructed them that republics were always short-lived, and they feared that America might quickly adopt kingship. From Paris, commenting on his experience of three years abroad, Thomas Jefferson wrote to George Washington: “There is scarcely an evil known in these countries which may not be traced to their king as its source.” Decades of struggle against royal governors had taught Americans that the executive was their enemy, that legislative assemblies spoke for the people.

Despite the fulminations of the Framers of the Constitution against George III, the idea of a strong executive struck a responsive chord. The theorists they read—Blackstone, Locke, Montesquieu—all accepted executive authority. John Locke had written, “The good of the society requires that several things should be left to the discretion of him that has the executive power.” Monarchy was the form of government with which Americans were most familiar and hence an inescapable template. Every one of the delegates had been born under the British Crown.

The scaffolding of a presidential office first presented to the delegates for their consideration by James Madison fell far short of majestic. The president was to be chosen not by popular election but by the National Legislature, and for only a single term. Foreign policy and the appointment of officials such as a national treasurer would also be entrusted to the legislature.

Though Madison was on his way toward recognition as father of the Constitution, Scottish-born James Wilson was staking a claim to be regarded as father of the presidency. Wilson, speaking with a marked Scottish burr, rose to move that a national executive of a single person be established, for a single magistrate could be held accountable to the people. Steel-rimmed spectacles low on the bridge of his nose, Wilson urged broad authority for an executive who would be a tribune of the people and would give “energy, dispatch, and responsibility to the office.” This motion brought the delegates up short, for numbers of them saw in a single executive “the foetus of monarchy,” but they accepted Wilson’s recommendation. Wilson had considerably less success in urging popular election of the executive. The assembly rejected Wilson’s motion resoundingly and approved instead choice of the executive by the national legislature (not yet called “Congress”) for a single term of seven years. In the course of the convention, the delegates were to go through sixty ballots before resolving how to choose a president. No sooner did they come to a conclusion than they voted to undo it.

In the first week of September, the Framers revised many of their previous decisions, especially in order to adjust the imbalance between the chief executive and Congress. They authorized the president to appoint major officials, including ambassadors and Supreme Court justices, and they turned over to him the right to make treaties, though with the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate. By agreeing to a proposal that the president “shall, by Virtue of his Office, be Commander in Chief of the Land Forces of U.S. and Admiral of their Navy,” they gave him immense power to determine strategy in wartime and other national emergencies.

The convention made a critical move in taking choice of the president from Congress and vesting it in an “electoral college.” It refined a proposal that James Wilson had aired earlier by requiring that electors meet in their respective states. Thus “college” was a misnomer from the outset; it was never intended to be a deliberative body that debated the merits of candidates. The convention fixed a president’s term at four years, but, altering its previous arrangement, agreed that a president would be perpetually eligible for re-election.

Once these large matters had been disposed of, the delegates made a quick meal of the remaining details. The president was required to be “a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the adoption of this Constitution,” at least thirty-five years of age, and a resident of the United States for fourteen years. He could be removed by impeachment for, and conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

The delegates assigned the task of polishing the draft of the Constitution to a committee of style chaired by the redoubtable Gouverneur Morris. After a spat with the governor of New York, Gouverneur Morris had removed to Philadelphia. Despite a peg leg, “The Tall Boy,” stomping about on his wooden limb while brandishing a cane, cut an impressive figure. Commentators reported that he had numerous sexual conquests. (It was rumored falsely that he had lost his leg by leaping from a balcony to elude an irate husband. “I am almost tempted to wish,” commented John Jay, that the rake “had lost something else.”) No one doubted that he was bright. He had enrolled at King’s College (which would become Columbia University) at twelve and was graduated at sixteen. As the most important member of the Committee on Style and Arrangement, Morris did more than tidy up straggling sentences. He imparted his own ideas of proper government. In particular, Morris’s committee crafted the portentous opening sentence of Article II.

Article II begins, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” The sentence seems innocuous, merely descriptive. But it contrasts starkly with a companion sentence in Article I: “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.” Is the absence of the restriction “herein granted” in Article II merely chance phrasing, or is it evidence of Gouverneur Morris’s cunning? No matter—for presidents have seized upon this phrasing to claim powers not enumerated in the Constitution. They have issued proclamations, acted in emergencies without seeking Congressional approval, and entered into executive agreements with foreign nations. Article II further provides that “he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,” another innocent-sounding clause pregnant with potential for amplifying the presidential realm.

When the document drafted by the Framers was submitted to the states for ratification, relatively few of the ensuing objections voiced were directed at provisions for the presidency—in large measure because of the universal assumption that the first incumbent would be George Washington. If hesitant delegates brooded about granting authority that might be abused, all they needed to do was look at the reticent figure who took his seat in the high-backed chair on the dais each morning at the convention and quietly presided, almost never intruding into the debates. The prospect that Washington would be the country’s first chief executive may well account for why, though sometimes by very narrow margins, the states ratified the Constitution, a consummation formally announced on July 2, 1788.

Featured image by Junius Brutus Stearns, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

George Harrison: ten quintessential songs [playlist]

George Harrison: ten quintessential songs [playlist]

This playlist with annotations that I have put together is not intended to be a “best-of” George Harrison (although all the songs here would easily be on such a playlist). Nor is it meant to be exclusive—one could easily devise a playlist with ten different “quintessential” George Harrison songs: one that would include “My Sweet Lord,” “It’s All Too Much,” “I Me Mine,” “Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth),” “Blue Jay Way,” and, of course, “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun.”

Rather, these are ten songs that represent various aspects of George Harrison’s brilliance as a songwriter and recording artist. They tie together themes, concepts, and musical and lyrical approaches in a manner that represents some essential aspects of George’s genius and creativity.

1. Don’t Bother MeWritten while he was lying ill in a hotel bed in August 1963, “Don’t Bother Me” could well stand as a credo for George Harrison, an early manifesto capturing his personality and entire mindset about fame. Especially in the context of the Beatles’ 1963 album, With the Beatles—replete with typically sunny original numbers by Lennon and McCartney including “All My Loving,” “I Wanna Be Your Man,” and “Hold Me Tight,”—“Don’t Bother Me” introduced the world to a new invention: the ambivalent pop star. For George, the very first message he chose to impart as a Beatles songwriter was that of a back turned to the crowd, foreshadowing his conflicted feelings about Beatlemania and particularly about the highly excitable crowds that flocked to their concerts.

2. If I Needed SomeoneGeorge explored the ambiguities of love and the difficulties of relationships in songs including “You Like Me Too Much,” “If I Needed Someone,” “I Want to Tell You,” “Long, Long, Long,” and even “Something.” Harrison wrote about love with a more sophisticated, mature understanding of its complexities than what was typically found in pop music of the time. Written in the conditional tense (note the first word of the title), “If I Needed Someone” (included on Rubber Soul) finds George singing behind the beat; the disparity between the melody line and the song’s rhythm echoes and implies the ambivalence of the lyrics. Plus, the song was propelled by Harrison’s patented jangle-rock style created by using the then-new Rickenbacker 12-string electric guitar.

3. I Want to Tell YouWith “I Want to Tell You” (on Revolver), George Harrison continued to write about the impossibility of putting feelings into words. In this way, he was very “meta” or post-modern. As startling as the jagged, dissonant piano chords that color the song’s overall sound is how perfectly they replicate in music the lyrical meaning, echoing the narrator’s stated inability to communicate clearly, while introducing a discordant sound rather alien to pop music. In less than three years, the Beatles went from “I Want to Hold Your Hand” to “I Want to Tell You.” That alone speaks volumes of the difference between Lennon and McCartney’s songwriting and Harrison’s

4. Within You Without You“Within You Without You” on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was George Harrison’s most sophisticated Hindustani-pop fusion effort—commonly referred to as raga rock. The structure of the song adhered mostly to the Northern Indian classical format, albeit with verses and refrain organized in a recognizable Western pop style. Harrison was the only member of the Beatles to play on the track, which employed musicians from London’s Asian Music Circle and Western classical musicians for the orchestral background. With the opening line, “We were talking about the space between us all,” the song continues to explore the perennial theme of the impossibility of clear communication.

5. All Things Must PassGeorge Harrison had tried to get the Beatles to record this song, and they did rehearse it during the January 1969 “Get Back”/”Let It Be” sessions. It was even originally slated to be part of the setlist for the famed “rooftop” concert at Apple headquarters at the end of that month. But nothing ever came of it, Beatle-wise. George revived the tune for his first solo album, aptly choosing it as the title track, which could not help but be seen as a commentary on the breakup of the Beatles. Harrison self-consciously wrote and recorded the song in the style of The Band, with whom he had spent time in Woodstock, N.Y., in autumn 1968.

6. What Is LifeAlso included on All Things Must Pass, “What Is Life” is a perfect pop single— channeling Motown and early rock ’n’ roll even as it creates an entirely new sound, bright and effervescent, soulful and anthemic, and incredibly catchy, its multiple riffs circling in and around one another, building a glorious celebration of the power of music to express a gleeful combination of love, lust, and gospel-like prayer. As in so many of his best songs, Harrison kicks it off with an invocation of frustrated expression: “What I feel, I can’t say.”

7. Be Here NowFound on George Harrison’s second solo album, Living in the Material World, “Be Here Now” borrowed its title and concept from the 1971 book of that name by Baba Ram Dass (né Richard Alpert), one of the “bibles” of the Sixties counterculture. Its musical setting is vaguely reminiscent of Harrison’s Beatles numbers “Blue Jay Way” and “Here Comes the Sun,” although it was dialed down a few beats from the latter to make the music more meditative in keeping with the song’s message: that the past and future are illusory and that the only state of being that matters is the present. One of Harrison’s most profound and evangelical songs is thus delivered in one of the most quiet, gentlest performances of his career, one that is also, most appropriately, timeless—the most intimate performance on his most intimate album.

8. Dark HorseThe bouncy, rocking title track of his 1974 solo album served as an updated manifesto as well as an answer song to critics and former bandmates. Calling himself a “dark horse” (a name he also gave to his nascent record label), with the connotation of constantly being underrated and underappreciated, gave new meaning and focus to his work; it served to recontextualize his professional and personal lives with a new self-narrative. Whether it was as a Beatle or a solo artist or a lover or a husband, he seemed to be suggesting, he was “a blue moon,” as he sang in the song, something that only occasionally or rarely shows up, not unlike a “dark horse.” The smart money does not bet on a dark horse, as dark horses win only once in a blue moon. Harrison had a way of defying the odds.

9. You“You” was originally composed for a projected solo comeback album by Ronnie Spector, which was going to be co-produced by Harrison and Spector’s then-husband, Phil Spector. The project was aborted midway through, but Harrison made eventual use of several of the songs he wrote for Spector, including “You,” found on his 1975 solo album, Extra Texture, where it was transformed into a joyously upbeat Motown-style love song. It has an instantly recognizable quality to it, one full of happiness and movement and delirium—a perfect bit of pop that just happened to have been made by one of the most serious songwriters and musicians of the rock era. One can even hear echoes of the music and lyrics in Paul McCartney’s megahit, “Silly Love Songs,” released the following year, whose refrain, “I love you”—which also figures prominently in Harrison’s song—could be a pun on “I love ‘You,’” a reference to the Harrison tune.

10. This SongThe funniest song ever written about being accused of plagiarism.

Featured image by despoticlickbild on Pixabay

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

September 25, 2024

Bootless cats, curious idioms, and Kattegat

Bootless cats, curious idioms, and Kattegat

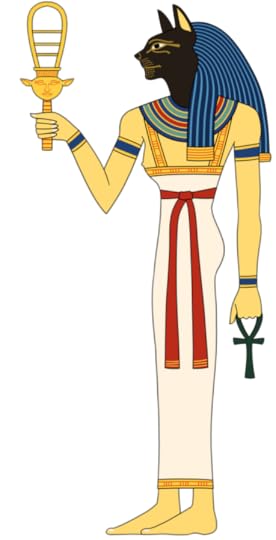

Bastet, the Egyptian cat goddess.

Bastet, the Egyptian cat goddess.Image by Eternal Space via Wikimedia Commons. CC0 1.0.

Over the years, I have discussed the origin of quite a few animal names. Despite my inroads, most of them—from heifer to dog—remain problematic. Yet no word is more enigmatic than cat. Two names for cat dominate the world: either some variant of kat or miu ~ mau (Ancient Egyptian) ~ mao (Chinese). Apparently, cats mewed ~ meowed in the remotest past, just as they do today. But the origin of the word cat is unknown, in contradistinction to puss, which may be onomatopoeic (sound imitative: compare the word piss). The word seems to have migrated to Eurasia from Africa, a statement that won’t surprise those who have heard something about the history of cats in Ancient Egypt. As far as etymology is concerned, we can only say with some certainty that cat has always referred to the domesticated cat, while at least in Latin, the name for the wild cat was fēlēs (hence English feline “related to cats”). The origin of fēlēs is also unknown (perhaps a borrowing from a lost Alpine language).

In folklore, cats are often evil, but benign examples are also known. Puss in Boots is the third son’s helper, and it is, most probably, for this reason, the friendly pet made its way to English folklore and assumed the role of Dick Whittington’s savior. (See a monument to Dick in the header of this post.) Since cats do not hunt rats and since one cat could not possibly kill hundreds of rats, it has been suggested that one of Whittington’s ship was called “Cat.” I will quote a passage from a letter by William Cole, an eighteenth-century antiquarian: “The commerce this worthy gentleman carried on was chiefly confined to our coasts. For this purpose, he constructed a vessel, which, for its agility and lightness, he aptly christened a cat. Nay, to this our day, gentlemen, all our coals from Newcastle are imported by nothing but cats. From thence it appears, that it was not the whiskered, four-footed, mouse-killing cat, that was the source of the magistrate’s wealth; but the coasting, sailing, coal-carrying Cat: that, gentlemen, was Whittington’s cat” (Notes and Queries, 2nd Series, N. 32, August 9, 1856, p. 117).

The helpful puss in boots.

The helpful puss in boots.Image by L. Bakst via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

This is a clever hypothesis, but, to use James A. H. Murray’s favorite phrase, it is at odds with chronology. The real Dick Whittington, whose biography is known reasonably well, died in 1453, while, according to the OED, the earliest attestation of the nautical sense of cat does not antedate 1799, and the ship did not get its name because it resembled the familiar pet. There is, of course, a beam, “the tackle used for hoisting the anchor to the cat-head,” known as the cat-tackle. It projects from the bows of the ship, called cat head. Yet nothing connects this object with the supposed name of Dick Whittington’s vessel, allegedly (!), sailing to distant lands.

It is amazing how many idioms celebrate cats. Some, for example, to let the cat out of the bag have been explained reasonably well. A few such have figured in this blog. See the posts for March 21, 2007; July 22, 2015, and February 15, 2017 (the latter on the grinning Cheshire cat, and in this context, I cannot help citing the phrase enough to make a cat laugh.) Even forgetting about bags, we can see that cats find themselves in all kinds of strange places. To cast the cat in the kirn (the date for it in my database is 1868) seems to refer to a desired situation (kirn is the northern variant of churn, a vessel or machine for making butter). Presumably, a cat will enjoy being inside such a vessel! Walter Scott knew the idiom, and we read in Chapter 35 of his novel The Monastery (1820) that …it is ill done to teach the cat the way to the kirn, meaning approximately that it is wrong to teach one’s grandmother to suck eggs or to teach a fish how to swim. Yet in 1889, an American cited the phrase cat in the cream pot, almost identical to the previous one, but stated that it meant “a row [that is, a noisy disturbance] in the house”!

Not improbably, such idioms tend to circulate in the community, with no one knowing for sure what they mean, and more or less arbitrary interpretations appear and even stay. Perhaps the most often discussed phrase featuring cat is it is raining cats and dogs. If the suggestion I favor is correct, cats and dogs in that idiom do not refer to animals. Those interested in my ideas will find an explanation in the first of the posts mentioned above, in the post for November 13, 2019, and in my book Take my Word for It (at lie doggo).

Many idioms referring to cats are widely known, for instance, that cat won’t jump, curiosity killed the cat, and so forth, while others may be misleading, like kitty-corner (from), which contains no reference to cats. The most amazing cat phrase I know is dog my cats, a synonym of blow me down with a feather, that is, an exclamation of utter surprise. I first saw dog my cats in David Copperfield and later in Mark Twain and O. Henry but never heard it in real life. The idiom is an ideal case of teaching students grammar: dog is a verb (an imperative), while cats is a noun.

Despite the near-ubiquity of syllables kot, cat, and the like in the name of the cat, many more variants exist. One of them is puss. It has counterparts in Germanic, Celtic, Baltic, and elsewhere. As suggested above, it may be sound-imitative. The German scholar M. T. E. Seitz and the British linguist Alan S. C. Ross published impressive lists of the words for “cat” all over the world. The variety of names is astounding. Numerous verbs for “bending” sound like kat (because the cat tends to arch its back), but cica, kisa, kot, beku, and many, many others abound too. Incidentally, words used for calling animals is also an extremely interesting chapter in the study of etymology. I don’t know how proficient Russian cats become in Russian, but they react to kis-kis-kis.

By way of postscript, I would like to mention an old hypothesis for what it is worth. The name of the strait Kattegat is usually explained as meaning “cat’s gate,” with reference to the animal’s arched back. In 1940, W. Kaspers suggested in Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung 67, pp. 218-19, that the reference in such place names as Kattegat, Katwik, Katwijk, Kattsund, and quite a few others is not to the cat but to the boomerang-like weapon, known in Latin as cateia. Though the origin of the word cateia is obscure, medieval descriptions show that this weapon did look like a boomerang, a bent or angular device. I am not a specialist in this area, but my experience shows that such stray notes are easily lost in the never-ceasing torrent of publications, and worthwhile ideas are sometimes disregarded. If Kasper’s hypothesis is known and has been refuted (no refutation came my way), sorry, but if it is reasonable and forgotten, then, as Captain Cuttle taught us, “when found, make a note of.” And a final flourish: if you never heard Rossini’s “Duetto bufo di duo gatti,” this is the right time to do so.

A boomerang and a strait.

A boomerang and a strait.Image 1 by Maximilian Dörrbecker (Chumwa) via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.5. Image 2 by Bellezzasolo via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

PS. Thank you for sending me questions. There were two of them. 1. The name Ernest is indeed derived from the adjective earnest. 2. Hunks “miser” is an obsolete word, though still current in some dialects. I cannot remember where I saw it for the first time and why it attracted my attention.

Featured image by Internet Archive Book Images via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

The precedents of the presidency

The precedents of the presidency

The United States Constitution drafted in 1787 is one of the shortest written governing charters in the world. The majority of the 4,000 words are devoted to Congress, leaving a relatively scant description of the presidency in Article II. In many ways, the presidency we have today barely resembles the office outlined in the Constitution. Instead, the office was created and defined by the early office holders who viewed the Constitution as a good first step, but not the end game.

When George Washington took the oath of office and became the first president on April 30, 1789, he began to fill out all the fuzzy bits of the presidency overlooked or ignored in the Constitution. He determined how the president would work with the other branches of government, interact with average citizens, manage domestic crises, and dictate foreign policy. He filled the Supreme Court, created the cabinet, and asserted executive privilege for the first time. He then retired, crafting the two-term precedent for the presidency, which was codified into law with the 22nd Amendment.

But when Washington went home, the presidency was still largely undefined. Washington had offered one possible definition, but it was unclear if his model would work for anyone else. Washington’s stature was unparalleled. No one else would ever enjoy the same vaunted and unchallenged position. Would Congress, the executive departments, and foreign nations respect the presidency if someone else occupied it? Would the American people recognize it?

The presidency of John Adams was equally as pivotal, therefore, because he defined the presidency for everyone else. He changed the presidency in two ways: he fully embraced and defended the powers of the presidency, and he lost and went home.

First, Washington had mostly wielded presidential authority with little pushback. As a result, many executive powers were still theoretical until tested. Adams faced tests from extreme voices in his cabinet and Congress. The Arch Federalists, the radical wing of Adams’s political party, attempted to create an executive-by-committee presidency, like the British cabinet today. Adams pushed back on these efforts and asserted his sole right to pursue diplomacy and define foreign policy. The secretaries had a right to share their opinion; they could not demand the president follow their advice.

Adams also insisted on the right to change cabinet personnel at will. The Constitution mentions department secretaries, but it does not say how many, what kind, how they will be appointed, or how they will be removed. In the summer of 1789, the First Federal Congress created the first three departments (war, state, and treasury) and the attorney general. They determined that the president would appoint secretaries but could not find consensus on how they would be removed, so they simply left it out of the bill.

Both Washington and Adams assumed the president had the unilateral power to remove a secretary, but Washington never tested this theory. He never fired a secretary. Instead, his secretaries voluntarily resigned or retired. In May 1800, Adams removed Timothy Pickering and appointed John Marshall the next secretary of state. Congress considered this unprecedented step before ultimately confirming Marshall and tacitly approving the president’s right to fire a secretary. Until Adams tested this authority, it was theoretical. Every president since Adams, except Andrew

Johnson, has enjoyed this privilege and the Supreme Court affirmed the president’s right to remove secretaries at will in Myers v. United States (1926).

Second, Washington had taken the first and hardest step when he willingly gave up power in 1797. He was still wildly popular and could have easily won a third term. But as the violent insurrection on January 6, 2021 reminded us, we can never take for granted that the losing candidate will go home quietly and peacefully. For context, when Adams went home on March 4, 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte was on the throne in France. In 1815, Napoleon staged a wild escape from the Isle of Elba to seize the throne for an additional 100 days. Unlike his more violent contemporaries, Adams did everything in his power to ensure a smooth transition. He then returned to his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, where he wrote to President Thomas Jefferson, “This part of the Union is in a state of perfect Tranquility and I see nothing to obscure your prospect of a quiet and prosperous Administration, which I heartily wish you.”

A republic is characterized by the peaceful transfer of power. John Adams knew that sometimes in a democracy, you lose. He loved the republic even when he lost and set an example for all his successors to uphold and defend the peaceful transfer of power. The presidency would not be the same without him.

Featured image: Official Presidential Portrait of John Adams, painted by John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

September 24, 2024

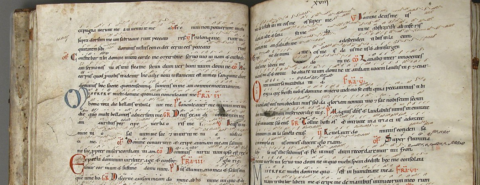

Prophetic libraries and books in ancient Israel

Prophetic libraries and books in ancient Israel

For most readers of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, the question of the ancient material forms of the biblical books rarely comes up. When it does, readers tend to imagine the large scrolls made famous by the discoveries around the Dead Sea. Even the Dead Sea scrolls, however, are centuries newer than most of the Hebrew Bible, which may well have been written on different materials and in different formats.

Rethinking the materiality of the biblical books before they were books opens up intriguing new possibilities for understanding the ancient texts.

At least some of the biblical prophetic literature started out as collections or libraries of scrolls rather than as what we call books. Considering these material forms of biblical literature is important because the materials and formats of texts play a crucial role in how both authors and readers encounter and think about them. Consider the difference, for example, between reading a hardbound book by a famous author and a small mass market paperback. Even before you crack the cover, the material form and format of each book contribute to your expectations as a reader. Thinking about the material and format of texts, therefore, is always important and is especially so when considering media cultures whose forms would have differed so markedly from our own. Rethinking the materiality of the biblical books before they were books opens up intriguing new possibilities for understanding the ancient texts.

One interesting possibility concerns the prophetic books of Isaiah and Jeremiah. The book of Isaiah was written over a long period of time and involved multiple authors. Isaiah 1–39 is more or less attributed to the titular prophet of the 8th century BCE. Due to a discernible difference in context, scholars generally understand Isaiah 40–55 and 56–66 to belong to two different anonymous prophets nearly two centuries later. Around the same time, scribes were also recording and collecting traditions that would eventually become the book of Jeremiah.

I argue that at this early stage, the literary traditions that would eventually become the books of Isaiah and Jeremiah were libraries of short scrolls rather than complete books. We can imagine in the 6th-5th centuries BCE something like an Isaiah-library and a Jeremiah-library, both of which would have included multiple scrolls and other short media. These libraries were the locus of growing prophetic tradition, elaborated on and expanded by the scribes responsible for them. By their nature, these libraries were fluid and open to texts being added, rearranged, removed, and revised.

One intriguing hint about the fluidity of these prophetic libraries appears in a reference to a supposed prophecy of Jeremiah that concludes the book of Chronicles (2 Chronicles 36:20–23) and is partially repeated at the beginning of the book of Ezra (Ezra 1:1–2). The passage in 2 Chronicles describes two prophecies that were fulfilled with the restoration from exile. The first identifies the end of the exile as the completion of Jeremiah’s promise of restoration after seventy years of exile (2 Chronicles 36:20–21, which is clearly referring to Jeremiah 25:11–12; 29:10). This reference to an oracle of Jeremiah is straightforward, but the author continues with the fulfillment of a second prophecy of Jeremiah:

But in the first year of Cyrus, king of Persia, in order to complete the word of YHWH through the mouth of Jeremiah, YHWH roused the spirit of Cyrus, king of Persia, and he sent a message through his entire domain … saying, “Thus says Cyrus, king of Persia, YHWH God of Heaven has given to me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has appointed me to build on his behalf the temple in Jerusalem.” (2 Chron 36:20–23)

What is so intriguing about this prophecy is that nothing in the book of Jeremiah corresponds to it. Jeremiah never speaks of rousing a foreign king or of the rebuilding the temple. By contrast, not only does Isaiah 40–55 mention both of these elements, it provides the name of the foreign king: “He says concerning Cyrus: ‘My shepherd. He will accomplish all I desire.’ And he says concerning Jerusalem: ‘it will be rebuilt, and the temple will be reestablished’” (Isaiah 44:28). Furthermore, the language used in 2 Chronicles of “rousing Cyrus” appears to be a direct reference to a repeated motif that appears in Isaiah (Isaiah 41:2, 25; 45:13).

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the author of Chronicles and Ezra attributed Isaiah 40–55 to the prophet Jeremiah. How could this happen? It is hard to explain if we assume the books of Jeremiah and Isaiah were already books. But if they were prophetic libraries, it is not difficult to imagine an anonymous prophetic text like Isaiah 40–55 finding its way into two libraries, one associated with Isaiah and one with Jeremiah. The author of Chronicles knew it as part of the Jeremiah library and attributed it to him. Through an accident of history, it ultimately found its way into the book of Isaiah.

Before they were books, these compositions were very different than the unified texts that we can find today in printed editions of the Bible. In some cases, the texts that would later be curated into single books were likely part of larger libraries with fluid boundaries. The transformation of these libraries into books profoundly transformed the texts—and altered the experience of later readers.

Featured image from Metropolitan Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons. CC0 1.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers