Oxford University Press's Blog, page 13

November 29, 2024

Don’t be afraid to switch tenses

Don’t be afraid to switch tenses

Somewhere in the recesses of my red-pencil memories is being told not to shift between past and present tense. This makes sense as a warning not to switch tenses clumsily, as in the example, “I was really hungry, so I make a sandwich.” It’s no better the other way around: “I am really hungry, so I made a sandwich.” Both actions are intended to be in the same time frame, so mixing past and present creates a jarring clash of tenses.

However, like many writing prescriptions, “Don’t shift tenses” is too simple. Writers shift tenses all the time, often using the present tense to refer to past events. This use of the present tense to narrate a story is called the historical present tense, or sometimes the dramatic present or the narrative present. The linguist Otto Jespersen, in his 1929 book An International Language, described it this way:

the present tense is used in speaking of the past … the speaker, as it were, forgets all about time, and imagines or recalls what he is recounting as vividly as if it were now present before his eyes. (19)

If you ever told a joke that begins “A man walks into a bar …,” you’ve used the dramatic present. Of course, writers often find it useful to set the clock when they use the dramatic present, as Alice Walker does in her essay “Beauty: When the Other Dancer Is the Self”:

It is a bright summer day in 1947. My father, a fat, funny man with beautiful eyes and a subversive wit, is trying to decide which of his eight children he will take with him to the county fair.

Walker transports you to the summer of 1947.

And here is the opening of writer Victor Lodato’s New Yorker piece “My Mother, the Gambler”:

“Give me three numbers, baby.” My mother made this request often—so often, in fact, that when I try to remember her voice this is what I hear. I can see her, too. She’s in the kitchen, sitting at the white Formica table, the green wall phone behind her, the phone she’ll soon pick up to place her bet.

Lodato cues the reader to the dramatic present with the phrase “when I try to remember this is what I hear.” Then we are in his childhood, a flashback that we see as though it were the present.

The fluidity of tense is not just a feature of narrative fiction. We find it in expository prose as well. Here is philosopher James Rachels in The Elements of Moral Philosophy:

Moral philosophy is the study of what morality is and what it requires of us. As Socrates said, it’s about “how we ought to live”—and why. It would be helpful to begin with a simple, uncontroversial definition of what morality is, but that turns out to be impossible.

He shifts to a future tense “will” to outline what he will do next (“First, however, we will examine some moral controversies … “) and then uses the past tense to discuss the controversies themselves:

Theresa Ann Campo Pearson, an infant known to the public as “Baby Theresa,” was born in Florida in 1992. Baby Theresa had anencephaly, one of the worst genetic disorders. Anencephalic infants are sometimes referred to as “babies without brains,” but that is not quite accurate.

Rachels shifts from past tense (“was born” and “had anencephaly”) back to the present tense (“infants are sometimes referred to” and “is not quite accurate”). He continues shifting seamlessly from past tense (discussing what people did, said, and thought) to present tense (unpacking the ethical principles involved in the discussion, such as “we are interested in more than what people happen to think. We want to know what’s true.”) He goes back to the past (“Were the parents right or wrong to volunteer their baby’s organs for transplant?”) and then to the present (“To answer this question, we have to ask what reasons, or arguments, can be given on each side.”) These are all necessary tense shifts in service of the exposition: setting out questions, narrating a case study, and identifying current issues, commentary, and conclusions.

Linguist Nessa Wolfson has studied the way that people switch into the present it in storytelling. She calls this use the conversational historical present. Here’s an example:

Well, we were getting dressed to go out one night and I was, we were just leaving, just walking out the door and the baby was in bed, and all of a sudden the doorbell rings and Larry says, ‘There’s somebody here for you’ and I walk in the living room and she’s there with both kids.

The shift in tense after “all of a sudden” breaks up the action between the leaving and the arrival of the visitor. It’s a rhetorical shift in the direction of immediacy and boldness.

So if you have been troubled by the writerly advice not to shift tenses, it might be time to reconsider that schoolroom proscription.

Look for opportunities to use shifts in tense strategically to amplify the narrative.

Featured image by Rain Bennett via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

How to escape from a maze

Assume you know nothing about the First World War, but had heard the name and wish to learn about it. Reasonably, you turn to the latest scholarship on the subject, only to find fundamental differences of view among professional historians. Some argue that the war had occurred in the early twentieth century; others, in the mid nineteenth. Some assert that important battles had been fought in northern France; others, in northern Spain. Some contend that Scotland was a participant, but that England had never been one; others, that England had indeed been a participant, indeed the first.

You might reasonably conclude that something was seriously amiss in the world of scholarship. In reality there are no such inconsistencies among military or diplomatic historians; but exactly such disparities of interpretation exist among historians of the Enlightenment. One historian says ‘the Enlightenment was this’; another replies ‘No! the Enlightenment was that’; a third trumps them: ‘No! No! The Enlightenment was the other.’ These incompatible interpretations show no signs of being reconciled in any new synthesis; instead, they proliferate.

Where did ‘the Enlightenment’ originate? Its parentage is still disputed. How did it end? Historians search the American Revolution in attempts to sight this phenomenon. Did it triumph in, or was it terminated by, the French Revolution? There are no intelligible answers, since these and others are questions mal posées.

Many historians formerly took the category for granted, without defence or even an index entry; this assumption is now untenable.

Readers escape from this maze if they accept that the term ‘the Enlightenment’ lacked an eighteenth-century referent and was a much later coinage, projected backwards for much later polemical purposes. Without such a referent, present-day writers are free to make the term mean what they wish it to mean. On the contrary, the belatedly developing history of the concept is itself the only history of the subject that can be written. Many historians formerly took the category for granted, without defence or even an index entry; this assumption is now untenable.

These previous usages were idealistic attempts to identify with a single term some vision of human happiness and progress. I nowhere argue against peace and bread, or for any Counter-Enlightenment. But I contend that in the eighteenth-century there was not one interesting and important thing happening, but many (the spread of literacy and the print culture; communication; international exploration; scientific discovery; economic growth). Even ‘Europe’ was too loose a term to generate much sense of unity; instead, wars between European powers became ever more destructive.

Those many interesting and important things were not reinforced by being seen as aspects of a common cause, swept on by a vast international movement. Indeed the absence of any such unifying movement was a leading reason why reforming causes were so difficult to frame and to carry forward to success. No concept, no movement.

At the time it was known that the famous figures recently depicted as champions of a unified ‘Enlightenment’ often argued for very different things (for example, Locke and Hume); moreover, when they met they were often at each other’s throats (for example, Voltaire and Rousseau). Their cosmopolitanism or tolerance was usually a vain boast. Their mutual hostility is often traceable to those figures’ intolerant views on religion (specifically, Christianity) rather than to differences over forward-looking programmes of social reform.

The great Cambridge classicist Dr Richard Bentley once encountered England’s then most famous poet, Alexander Pope, who in 1715 had just published an acclaimed English verse translation of the Iliad. Pope fished for compliments. Bentley responded with the memorable put-down: ‘It is a pretty poem, Mr. Pope; but you must not call it Homer.’ I adapt this as my courteous response to those who repeat the old orthodoxy: ‘It is a pretty story, Mr Historian; but you must not call it the Enlightenment’.

Feature image by Joshua Sortino via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

November 28, 2024

The risks of dopamine agonists for the treatment of restless legs syndrome

The risks of dopamine agonists for the treatment of restless legs syndrome

An extraordinary breakthrough of modern medicine occurred in 2005 when the FDA approved ropinirole for the treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS). With the first drug ever approved for this misery-inducing condition, patients finally had a highly effective treatment with relatively few side effects. Nearly 20 years later, ropinirole and its cousin pramipexole are among the most prescribed treatments for RLS, and they have been considered first-line therapy for over a decade.

Restless legs syndrome is an unpleasant sensation, typically described as an intense urge to move, that worsens later in the day, is provoked by holding still, and improves while moving. It can affect people of all ages, but it gets more common around middle age. For people with this condition, life can become unbearable. They are unable to sit long enough to enjoy a meal or watch a movie. Taking a flight or a long car ride is torture. Having an effective treatment like ropinirole and pramipexole was beyond a miracle for patients with severe symptoms.

Ropinirole and pramipexole fall under the drug category of dopamine agonists. This means that these drugs stimulate dopamine receptors in the brain. While it was known long before 2005 that dopamine-related drugs could improve RLS symptoms, those drugs had unacceptable risks. The two new dopamine agonists—which were joined in 2008 by a third drug, rotigotine—were considered much safer, and doctors who treated RLS flocked to them. Dopamine agonists were how RLS was treated. Problem solved, apparently.

Another extraordinary event is taking place in 2024, though. Dopamine agonists are not only being removed as first-line treatment for RLS, new guidelines by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine place dopamine agonists on the “do not use” list. This complete about-face is a result of years of observing that dopamine agonists are not the RLS saviors they were once thought to be. In fact, they have almost certainly caused even more suffering.

Dopamine agonists have two major problems: augmentation and impulse control disorders. Augmentation occurs when consistent use of a dopamine agonist starts to make RLS symptoms worse. This might manifest as patients having symptoms earlier in the day or having symptoms in other body parts, such as the arms.

Dopamine agonists are not the RLS saviors they were once thought to be.

Augmentation is thought to be the result of the brain shutting down its own natural dopamine production to rely more and more on the pills to stimulate dopamine receptors. As a result, patients require higher or more frequent doses to achieve the same degree of relief. Eventually, even those doses don’t provide relief, and the suffering starts to spread throughout the day. These drugs are particularly insidious because each time the dose is increased, patients feel better. Temporarily. If they try to decrease their dose, they feel worse. Essentially, patients become dependent on these drugs; they’re addictive.

The only treatment for augmentation is to stop the offending medication. Dopamine agonists must be weaned off, and the process can be brutal: insomnia, severe pain, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide, and more. When it’s over, though, the RLS symptoms are inexorably better.

The elevated doses of dopamine agonists that patients with augmentation often take can also cause a highly destructive condition called impulse control disorders (ICDs). ICDs are a form of compulsive behavior in which patients find it difficult or impossible to stop doing things that are harmful to them. The most common ICDs related to dopamine agonists are eating, shopping, gambling, and pornography consumption. Patients with a gambling ICD, for example, might spend 24 straight hours at a blackjack table. Those with a shopping ICD might start buying gifts they can’t afford for all their friends and family members just because an advertisement came on TV. The financial and social losses incurred by these patients can be massive, and many of them have no idea that their RLS medication is the cause.

With decades of experience, it became clear to physicians treating RLS that dopamine agonists were a seductive enemy to RLS patients. Exposing patients to the risks of augmentation and ICDs could no longer be justified, and they are no longer recommended for daily use. If patients do take dopamine agonists, the doses must be kept low, and ideally, used only sparingly for situations likely to trigger the RLS, like a long flight.

Fortunately, there are highly effective alternatives to dopamine agonists now. The most important treatment, bar none, is iron. A low level of iron in the brain is a very common cause of RLS and a very treatable one. Successful treatment of RLS begins with ensuring adequate levels of brain iron. After that, first-line drug therapy is now gabapentin, a drug originally approved for seizures that is highly effective for RLS, along with its related drug gabapentin enacarbil and their counterpart pregabalin. The other highly effective class of medications for RLS is opioids, including methadone and buprenorphine. Dipyridamole, a drug that used to be used to help prevent strokes, is starting to be used for RLS now. And earlier this year, a nerve stimulator band worn below the knees entered the American market for a drug-free treatment option. Each of these therapies can be considered for the treatment of RLS.

It is crucial for doctors and patients to understand the risks of dopamine agonists, including augmentation and ICDs. There are many alternatives to help this long-suffering group of people without the threat of making them worse over time. Patients who suffer with RLS should know they need not suffer forever.

Featured image by corelens via Canva

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

November 27, 2024

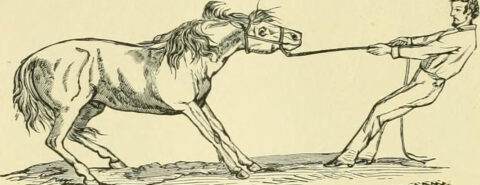

A ride on an unbroken colt

Animal names come up in this blog with some regularity, and our readers may remember that no one has trouble with them except etymologists. Colt is no exception. Despite its age (the word was known in Old English), it has been relegated to the words of unknown or uncertain origin. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (1966) cites a few possible cognates (or lookalikes) and says “…of obscure origin.” The OED online says the same. However, one thing is known: the old word also referred to a young donkey and a young camel. Consequently, the root was never bound up with only “a young stallion” or “a young horse.” If we succeed in discovering the sought-for original sense, it will probably refer (in some general way) to an unspecified hoofed creature, not fully-grown.

With regard to sounds, we should remember that vowels often alternate in the root (as in ride ~ rode ~ ridden, speak ~ spoke, come ~ came, riffraff, ping-pong, and so forth), and the common term, referred to in my posts, is ablaut. Consequently, with all due respect to the vowels, our search should mainly concentrate on the root k-l, assuming that t in colt is a possible remnant of an old suffix. One might object that we are playing a game of giveaway: with so many preconditions, who won’t discover an etymology? This objection would be wrong: words are not soldiers on parade, wearing the same uniform and marching in step. Variation is the very soul of word history. The problem is that a linguist should know the laws of the variation: not everything is allowed to alternate with everything else!

This Colt, named after the inventor’s last name, is harder to break.

This Colt, named after the inventor’s last name, is harder to break.Image by Metropolitan Museum of Art, via Wikimedia Commons. CC0 1.0.

Several perfectly reasonable suggestions about the words related to colt were made long ago. In Gothic, a fourth-century Germanic language (now dead), the noun kilthei “womb” occurs (-ei had the value of ee in Modern English thee and was not part of the root). An easily recognizable cognate of kilthei is Modern English child, from Old English cild. A child is then the fruit of the womb, and colt emerges as another “child,” but with a specialized meaning. The cautious Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology says: “…but cf. Sw[edish] kult, kulter, kulting, applied to half-grown animals and boys.” Few things are less informative than this perennial cf., used in dictionaries. How are we supposed to compare (“confer”) those forms? It appears that the Scandinavian words are related or at least seem to be related to colt. Anyway, let us “confer.” Indeed, besides the forms listed above, we discover Swedish kull (from kolder) “boy,” Swedish dialectal kullt “boy”; Danish kuld “brood” and Danish dialectal koltring “lad”; Norwegian kuld “siblings, children born to the same parents”; Old Icelandic kollr “round tip; head, skull,” and Middle Dutch poggenkuller “a frog’s clutch” (that is, the eggs laid by a female). The Old Icelandic place name Kolli may belong here too. My list is even longer, but we hardly need more words, because all of them point in the same direction. Even if some forms, cited above, only seem to be related and have to be disregarded, it is clear that all over the Germanic-speaking world, the complex k-l tends to refer to round (roundish) objects and children.

It has been a long time since I mentioned the First Consonant Shift in this blog. Germanic is an Indo-European language, but it changed the old consonants b, d, and g to p, t, and k (b is problematic, but we need not worry about it here). The classic examples are Latin duo, related to English two, and Latin genus, related to English kin. It follows that if the root k-l has cognates outside Germanic, it should have the form g-l. An incontestable example has been found only in Sanskrit, but it needs a long explanation, and I’ll skip it. However, see below! While examining the k-l root, it does not seem to be too adventurous to add calf to our herd. The animal name calf has even more close relatives than colt: its exact cognates occur in Gothic, German, Dutch, and Scandinavian. Etymologists feel a bit safer while dealing with calf than with colt and cite Scottish Gaelic galba “a very fat man” and Latin globus “globe; heap” (note the g-l group in those two non-Germanic languages!). Here, too, they encounter several tough questions (common when one goes into the Indo-European antiquity), none of which is of prime importance in this context. My only point is that Germanic col–t and cal-f are rather probably related and that col– and cal– referred to round things (remember globe!) and by inference, to young animals. If this conclusion is valid, then colt will no longer be a word “of unknown origin.”

Not necessarily a mooncalf.

Not necessarily a mooncalf.Image by Peter Hoogmoed via Unsplash.

Of course, the only question that is really worth asking is why the complex g-l (in Germanic, k-l) acquired such a meaning. Here, I’ll repeat what everybody says when confronted by this question. We connect sound and meaning only when the word in question is either sound-imitative (crash, crush, sizzle, giggle, yelp, bow–wow, and so forth) or sound-symbolic (a much less transparent case than the first). Why g-l? In a way, this is the question about the origin of language (incidentally, a much-discussed question today!). It is rather unlikely that we’ll ever be able to go beyond the supposition that once upon a time language was wholly sound-imitative and sound-symbolic. Today, neither comparative linguistics nor psycholinguistics can explain why the group g-l evoked associations with round things, but it apparently did. So much for colts and calves.

And here is a small note “for dessert.” Colt is related to kilt! Kilt surfaced in texts only in the early eighteenth century, and there is no doubt that it is of Scandinavian origin. In Old Icelandic, we find kilting “skirt.” Modern Scandinavian languages and especially dialects display a wide array of closely related nouns and verbs. Opinions about the origin of kilting diverge (who has ever seen etymologists agree on the source of an old word?), but if I am right, those opinions complement, rather than contradict one another.

Kilts in full display.

Kilts in full display.Image by William Murphy via Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Three suggestions have been offered with regard to kilting. Perhaps kilting is related to Old English cild “child.” This suggestion makes perfect sense and returns us to Gothic kilthei “womb.” Or perhaps the closest cognate of kilting is calf. Since I have a strong suspicion that cild “child” and calf belong together, I have no objections. Finally, kilting has been compared with colt. Again, as could be expected, I concur! No one has thought of combining all three suggestions, because the words discussed above (child, calf, and colt) are usually referred to different roots. Anyway, a kilting is a skirt, and it is only natural that the word’s root refers to the lap (as in sit in one’s lap) and the womb. The calf, the colt, and the child come from the womb. The tie among the three words and kilt looks natural. If I am forced to choose the best connection among those three, I’ll vote for kilt and cild “child,” but I’d rather abstain.

PS. I also wish to thank those who have commented on my post “Westward Ho.”

Featured image by Internet Archive Book Images via Flickr. CC0 1.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

We need to support our health and social care system

We need to support our health and social care system

Do you remember when we Clapped for Carers?UK health and social care systems are world leaders in so many ways. Whether it’s leading in medicine and treatments, to providing a social justice-based social care, the system does a great job in supporting the health and additional needs of some of the most vulnerable individuals in society. However, there is no doubt that UK health and social care systems are experiencing significant stress. Virtually every week we are hearing new initiatives from political parties about how they will save the system, or how record amounts of money are being put into the NHS.

The health and social care workforce face difficulties at almost every turn. They are often blamed when serious and distressing events occur, despite doing everything in their power to support those experiencing distress. They have difficulties in workload, satisfaction, looking after extreme events … all of which is against the backdrop of UK Covid lockdowns, where we were implored to stand on our doorstep and ‘Clap for Carers’ all while they were being disproportionately affected by Covid.

The Political Blame GameIn late 2023, the former UK prime minister stated that “we were making progress on bringing the overall numbers [of those on NHS waiting lists] down—what happened? We had industrial action and we got strikes”. Despite NHS waiting lists increasing steadily since 2012, with obvious increases during and following the end of Covid lockdowns, and December 2023 having some of the longest waiting lists ever (although there had been a small decline in that month), the blame is on the workforce for waiting lists that had been increasing year on year since 2012.

Far too often health and social care workers are blamed. The decision of the Conservative government to prevent social care workers from bringing their families to this country from abroad, for example, suggests that the immigration which is needed to keep the care system afloat is a problem. Indeed, nearly one in five of the social care sector are international, and The King’s Fund suggests that without them the sector will struggle to function. As such, governmental actions have inevitably had knock-on effects on the availability of care provision in this country.

We need a political system that supports and guides health and social care workers—not one which demonises and detracts from them.

The Organisational Effects on the WorkforceWhen health and social care professions go on strike, evidence from studies across the health and social care (and wider public services) sectors suggest that pay is only one of the myriad issues fuelling their discontent—even though we have seen teachers and social workers face amongst the worst fall in wages of all professions in the UK.

What would make more of a difference is decent support, at a level which provides the resources they need to make a difference.

Perhaps amongst the most damning evidence comes from national surveys and research which look at the impacts of organisational working conditions on the health and social care workforce. For example, since 2018/19 we have seen that social workers have among the worst working conditions of any occupation and profession in the country. These conditions have been consistently poor, and are undoubtedly contributing to the continually high levels of sickness absence and high turnover rates in the sector. These conditions are typified by high caseloads and long working hours. For example, Ravalier found that social workers worked, on average, over 8 hours per week more than they were contracted to. The picture is similar in other social and health care roles.

I would bravely suggest that, even if our health and social care workers could have regular decent wage increases, what would make more of a difference is decent support, at a level which provides the resources they need to make a difference. After all, study after study has shown that this is why they join the sector—to make a difference in the lives of the ill and vulnerable people who live in their very communities.

So what do we need to do to support our health and social care workforce? Well, firstly, claps don’t work. While they started as a nice gesture, they do not make up for the political, societal, and/or organisational issues highlighted above. We need better investment and support of the workforce which is so vital to the UK and beyond. We need to allow health and social care workers to have the resources they need to make a real difference. This will reduce turnover, improve satisfaction, and reduce sickness absence.

Featured image by cottonbro studio via Pexels.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

November 22, 2024

What does democracy look like?

What does democracy look like?

“This is what democracy looks like!” is a popular rallying cry of engaged democratic citizens across the globe. It refers to outbreaks of mass political action, episodes where large numbers of citizens gather in a public space to communicate a shared political message.

That we associate democracy with political demonstration is no surprise. After all, democracy is the rule of the people, and collective public action is a central way for citizens to make their voices heard. As it is often said, democracy happens “in the streets.”

Yet there’s more to democracy than meets the eye. Although democracy indeed involves collective action, it is also a matter of what goes on inside of us—the dispositions and values we bring to it.

To see what I mean, conduct an internet search of the phrase “this is what democracy looks like.” Select your favorite of the pictures. Now imagine discovering that the people in the photo are all paid actors who were given political signs, taught chants, and sent into a public space to enact a political demonstration. Suppose further that but for the pay, none of them would have shown up.

Notice how your attitude to the image shifts. The photo depicts citizens gathered in a public space to communicate a political message, yet something’s amiss. Democracy isn’t acting. Citizenship isn’t a paying gig. Astroturfed political engagement isn’t what democracy looks like.

Mass public action manifests democracy only when citizens are informed.

From this, we might say that mass public action depicts democracy only when the participants are sincere about the message their group activity aims to communicate. They must be advocates who are engaged in the demonstration for the purpose of communicating that message.

Now consider another example. Return to the image you selected. But instead of imagining the participants to be actors motivated by a paycheck, suppose that they are fundamentally mistaken about the political message they are conveying. Let’s assume they’re carrying signs supporting a policy that they believe will make certain medications more affordable, but which actually proposes to make them more expensive.

Notice that according to democracy’s historical opponents, this is exactly what democracy looks like: mobilized but ignorant mobs demanding political results they do not comprehend. But one need not embrace this negative assessment of democracy to recognize that certain brazen forms of ignorance sully the democratic character of a demonstration. We might conclude, then, that mass public action manifests democracy only when citizens are informed (or at least not wildly misinformed).

A democratic society is one that strives to become a self-governing society of equals.

Putting the two examples together, we can say that in order for an instance of mass public political action to depict democracy in any laudable sense, the participants must be both motivated by their message and adequately informed about what their message means. The notable feature of these two requirements is that neither can be captured in a picture. We can’t discern a person’s motives or degree of informedness simply by looking. Democracy can’t be depicted in a photograph. It has largely to do with the attitudes and habits that underlie our political activities.

This thought can be captured by saying that democracy is centrally a civic ethos. This ethos derives its content from the fundamental democratic ideal of self-government among equals. To be clear, this ideal identifies an aspiration. A democratic society is one that strives to become a self-governing society of equals. And that aspiration calls upon us as citizens to cultivate within ourselves the competencies that enable us both to advance justice and duly recognize the equality of our fellow citizens by attempting to understand their political values, priorities, and concerns.

Democracy’s civic ethos, then, invokes the need for citizens to be engaged participants who are also politically reflective. The dual aspect of democracy’s civic ethos gives rise to conflict. Engaged political participation exposes us to group dynamics that artificially escalate partisan animosity, intensify in-group conformity, and tether our political imagination to the categories and rivalries of our current political world. That is, in the ordinary course of meeting our civic duty to be democratic participants, we undermine our reflective capacities.

This conflict within the democratic ethos has become especially difficult to manage because our everyday social environments are saturated with triggers of our political reflexes. To reclaim the democratic aspiration, we need to critically reexamine our own political habits, and this reexamination calls for moments of solitary reflection on political ideas and circumstances that lie beyond the familiar landscape of contemporary democracy. Democracy indeed happens “in the streets” when citizens engage in collective political action. But democracy also happens in public libraries, parks, and museums—in spaces where citizens can be alone to refresh their political imaginations by contemplating unfamiliar and distant democratic possibilities.

Featured image by Colin Lloyd via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

November 20, 2024

Westward Ho

The blog Oxford Etymologist is resuming its activities. I expected multiple expressions of grief and anxiety at the announcement that I would be away from my desk for a week, but no one seems to have noticed. Anyway, I am back and ready to finish the series on the four cardinal points. Since it is in the west that the sun sets, I relegated this post to the end of my long story. Despite what I said above, I did hear from two readers. One added a comment to the post “Up North” and summarized his views on the origin of all four words. His summaries are fine, but no one should conclude that they represent the ultimate truth. As I tried to make clear, the etymology of the words in question is debatable. The main dictionary of Indo-European etymology by Julius Pokorny is a source every historical linguist consults, but this does not mean that it contains the final answers to our questions. Pokorny’s data and suggestions should be treated with all the respect they deserve and used as material and stimulus for further research.

The second letter that has recently reached me came from a professional lexicographer. The writer seems to have taken issue with my attitude toward comments on my blog. She wrote that I sneer at amateurs who dabble in etymology and yet admire the person who once wrote a letter to Notes and Queries about the origin of the word oof “money” (see my post for May 21, 2014). Incidentally, I often criticize people’s unprofessional views but never sneer at them. Years of teaching made me very cautious and all but killed my sense of humor. Oof is slang. With a bit of luck, anyone may discover the source of such a word, even though this kind of luck is a rare commodity. But in order to find the origin of words like house, big, read, yet, and thousands of others, one needs a huge stock of special knowledge, so that when someone without such knowledge or after reading one popular book expresses “an opinion,” I, naturally, protest. The same person would never have dared confront a physicist, a biologist, or an engineer on their turf. But we all speak. Doesn’t that mean that we are all natural etymologists? No. I am sorry that a lexicographer, my colleague, could disagree with such a reasonable attitude.

Back to the cardinal points. I wonder whether anyone still reads Charles Kingsley’s novel Westward Ho. But the phrase is familiar from the names of cafes, casinos, and their likes. Ho is an exclamation, meant to call attention to something that appears on the horizon. I too say: “Westward ho” and turn to the origin of the word west.

Westward ho!

Westward ho!Image by Stjanss and mriedel via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

As understood long ago, the points of the compass may have once been called “morning,” “noon,” “evening,” and the like. Alternatively, they often got their names from the winds. One also seems to find the looked-for etymons in words like front, back, warm, cold, bright, moist, left, and so forth. The English name for the west sounds almost the same all over the Germanic-speaking world, though once again the story began not with a noun but with an adverb of orientation (here, westan “from the west”). The noun was later “abstracted” from it. Not only Germanic but also all the Indo-European words for “west” sound somewhat (!) alike: Greek hésperos, Latin vesper, Irish fescor, Old Slavic vecheru, Lithuanian vâkaras, and so forth. Once, they must have begun with hwe-. This first syllable recurs all over the place, but the remainders diverge. Why do they? With regard to Slavic sever “north”, the idea of taboo has been pressed into service: perhaps people were afraid to call the cold wind by its “real” name and garbled it beyond recognition. The same may be true of some Germanic words that interest us, but this process is doomed to remain guesswork and therefore presents minimal interest. (Elsewhere, taboo is an important factor in the history of words.)

Stormy sky: a strong wind from the sea.

Stormy sky: a strong wind from the sea.Image by giorgos kalogridis via Pexels.

Etymologists always try to reconstruct the oldest form, and in the study of west, it is just such an ancient protoform that evades us. It certainly makes sense to suggest that west refers to something below or perhaps behind us. Compare the English phrase the westering sun. A clever conjecture connected west and Greek ústeros “the hind one,” but it presupposed the vowel alternation e : u (ablaut, mentioned earlier in this series), and this is perhaps the reason it has never been discussed, let alone accepted. Yet it is worthy of consideration, especially in light of the Slavic parallel. Russian vecher “evening” is related to vchera (stress on the second syllable) “yesterday” and, quite probably, to veko “eyelid,” with reference to things behind us or able to close. Lithuanian Vókia “Germany,” literally, a land behind, means “a western land.” (This train of thought is old and almost forgotten.) According to a competing hypothesis, the root of west is Indo-European hews- “to be, stay; live,” with reference to having a rest. This is perhaps too abstract and less appealing than the previous conjecture.

In Pokorny’s dictionary (see the reference to it above), west is derived from the root au– “away, downward,” in accordance with the idea of the great German historical linguist Karl Brugmann. The problem with such short, reconstructed roots is that they tend to multiply. Allegedly, the most ancient Indo-European had eleven (!) roots sounding as au-, including one meaning “wet.” Since rain falls from the sky, couldn’t “wet” and “downward, away, fall, drip, water” be variants of one root? Yes, indeed. Another one of the eleven homonymous roots allegedly meant’ “wind; to blow.” Viktor Levitsky (his name also turned up in the earlier essays) preferred to trace west to the concept of the wind from the west. As we have seen, the names of the cardinal points are closely connected with the names of the winds and often derive from them. But in this case, the proposed tie is rather weak.

Among homonymous Indo-European roots.

Among homonymous Indo-European roots.Image by Ritesh Man Tamrakar via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.0.

To sum up: what is the main takeaway from the four previous essays? The rationale behind coining the words north, south, east, and west often seems rather clear. East and west go back to a common Indo-European root; south and north are more narrowly Germanic. In all four cases, the impulses that resulted in coining the words in question seem to be almost within reach, but every time we think we have captured our prey, it evades us. Though some hypotheses look persuasive, we never or very seldom reach the point at which we may say that we have hit the nail on the head. (This is also true of west.) But such is the way of most etymological riddles. In our case, dictionaries either list a few cognates and stop or cite the protoform suggested by Pokorny (someone who, to cite Plato, seems to have the protection of the wall). Only the most detailed sources present the entire picture. Yes, deep are the roots, but east or west, home is best. Westward ho!

Featured image by Jason Mavrommatis via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Understanding fossil-fuel propaganda: a Q&A with Genevieve Guenther

Understanding fossil-fuel propaganda: a Q&A with Genevieve Guenther

2024’s UN climate summit in Azerbaijan is a key moment for world leaders to express their convictions and plans to address the escalating stakes of the climate crisis. This month we sat down with Genevieve Guenther—author of The Language of Climate Politics, and founder of End Climate—to discuss the current state of climate activism and how propaganda from the fossil fuel industry has shaped the discourse.

Sarah Butcher: How did you first get involved in climate change activism?

Genevieve Guenther: I got really concerned about climate change after I had a child and started to worry about what kind of world he would inherit after I died. So I utilized my training as a scholar to master the field of climate communication, while learning about climate science and economics, in the hopes of using my expertise in the political effects of language to help move our climate politics forward. Eventually I began working on The Language of Climate Politics, and while I was writing it I also founded the group End Climate Silence to help push the news media to cover climate change with the urgency it deserves.

SB: How did you come to recognize that the language people–and more importantly the media—use was having an impact on efforts to actually create change?

GG: As recently as 2018, public-opinion surveys showed that even many Democrats felt some doubt that climate change was real. I could see that this doubt tracked very neatly onto the rise of the disinformation that there was a lot of scientific “uncertainty” around the issue. (Scientists were projecting a range of possible outcomes from rising carbon emissions, but they were definitely not saying that climate change was fake.) I realized that voters had heard about this supposed uncertainty because, at the time, news outlets were platforming so-called “climate skeptics” to provide what they called “a balance of opinion” about climate change. Later I discovered that most Americans learn everything they know about climate change from the news media. So it became apparent to me that how journalists talk about climate change had, and still has, a great deal of influence over America’s climate politics!

SB: Do you have any examples of fossil-fuel propaganda that you share with people to illustrate the scope of the problem?

Guenther presented her book The Language of Climate Politics at the book’s launch event at The UN bookshop.

Guenther presented her book The Language of Climate Politics at the book’s launch event at The UN bookshop.Image courtesy of Genevieve Guenther, used with permission.

GG: Fossil-fuel propaganda is a huge phenomenon! There are many lies about climate change and clean energy floating around. You may have heard that developing off-shore wind turbines is killing whales (it isn’t), or that fossil fuels are the most reliable form of energy (they aren’t), or that focusing on your personal carbon footprint is the most important thing you can do to fight climate change (it definitely isn’t). But the propaganda I investigate in my book is the complex of lies, myths, and incorrect assumptions that create the false and dangerous belief that we can keep using coal, oil, and gas but still deal with climate change anyway. We cannot! So I expose the scientists, economists, lobbyists, and journalists who propagate this false belief, illuminating the bankruptcy of their ideas and giving readers clear, actionable messages to counter mis- and disinformation in their own conversations about climate change. Focus-group polling shows that these messages increase concerned Democrats’ and Republicans’ support for phasing out fossil fuels by up to ten points.

SB: What are the biggest misconceptions you see around fossil-fuel propaganda?

GG: That it spreads only among the uneducated or the right wing. My book shows how some scientists, economists, journalists, and even climate advocates sometimes inadvertently echo the core fossil-fuel propaganda and thereby normalize it, shaping mainstream views about climate change.

SB: What sets your book on the climate change crisis apart?

GG: I think my book is personal and accessible, but also has a real scope. I try to sort out the whole kaleidoscope of climate disinformation, so we can see and counter it clearly. The book discusses what the science says will happen to the US and the UK if we don’t phase out fossil fuels; how past economic models have low-balled climate damages and what the new economic models project for the future; the promise and challenges of climate technologies; the recent history of US and international climate politics; advice for coping with climate change emotionally and helping to build a more powerful climate movement; and more! The climate journalist Amy Westervelt said in her endorsement that the book “takes the whole overwhelming universe of fossil-fuel propaganda and distills it,” providing “one of the best explanations I’ve read of how the heck the climate crisis has gone unchecked for so long.” And Kieran Setiya, who’s not even a climate person, but a Professor of Philosophy at MIT, said: “if you want to understand the climate crisis and you only have time to read one book, this should be it.” I’m pretty proud of that, honestly.

SB: What was the most surprising thing you discovered working on this book?

GG: That China has enacted a whole-of-government, whole-of-society climate policy, called the “1 + N” policy, to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060. That was a huge surprise! I hadn’t known that China had passed comprehensive climate legislation. I don’t think many people in the West know this either. But I describe the provisions of China’s climate policies in Chapter 4, so hopefully now more people will understand the depth of China’s commitment to decarbonization.

SB: Is there anything in the current debate that gives you hope about our climate future?

GG: I try not to deal in hope. Hope keeps my focus on things I cannot control. Instead, I try to embrace what I think of as intellectual humility—I don’t know what’s going to happen politically, because no one does—and I try to accept what I take to be my duty. That is, I feel like, being alive with relative privilege at this historical moment, I have a responsibility to help resolve the climate crisis, so that at the end of the day I can say I did my best. I mean, that’s all that can be asked of us, right?

SB: What do you hope readers take away from your book?

GG: I hope they feel equipped to resist the dominant forms of climate disinformation in public discourse and feel empowered to talk about the climate crisis in ways that will focus the conversation on phasing out fossil fuels. And I hope they feel fortified and inspired to do that work!

Featured image by USGS on Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

November 18, 2024

“Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow”: tragedy and the environmental crisis

“Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow”: tragedy and the environmental crisis

Our environmental crisis is often described in tragic terms. Weather events shaped by global warming are deemed tragic for the communities affected. Declines in fish populations are attributed to the so-called tragedy of the commons. Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of England, has spoken of a “tragedy of the horizon”: that the “catastrophic impacts of climate change will be felt beyond the traditional horizons of most actors – imposing a cost on future generations that the current generation has no direct incentive to fix”.

Literary theorists point out that, when used in non-literary contexts such as these, the word tragedy often loses its distinct meanings. Nonetheless, working with tragic theory can, I think, help us reflect on the environmental crisis.

If, for example, we assume—as some commentators have—that the tragic figure is always somehow implicated in their suffering, then this brings into focus issues of climate justice: tragic narratives’ concern with accountability, that is, may illuminate the responsibility some global communities have to compensate others for the impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Working with tragic theory might also help us reflect on our difficulty in responding to the crisis. In arguing that literary genres struggle to grapple with the timespans of environmental catastrophe (drawn attention to by Carney), the author Amitav Ghosh takes the realist novel as his example. As Jennifer Wallace points out, tragic catastrophe tends, similarly, to play out within a relatively short period—according to Aristotle’s strictures, a single day. This may render it unsuitable for representing environmental degradation and its impact on the world’s poor, a process influentially described by Rob Nixon as “slow violence”. Equally, Wallace argues, it may inhibit our capacity to see the environmental crisis as tragic.

Ascribing tragic suffering to fate or to the gods risks mystifying actions and consequences that should, in fact, be laid at the door of humans and their ideologies.

Tragedy may also appear an unhelpful frame through which to approach the environmental crisis because, again like the realist novel, it’s a genre tightly focused on human experience rather than—like pastoral or the georgic—on human interactions with the natural world. Tragedy is, we might say, created through the interplay of strong human emotions (ambition, love, grief) and situations where individual desires come into conflict with social—that is, manmade—systems.

Or so we’ve been told. Many scholars of tragedy have been wary of discussing other-than-human agency, and with good reason. Ascribing tragic suffering to fate or to the gods risks mystifying actions and consequences that should, in fact, be laid at the door of humans and their ideologies. Just as speaking of “natural” disasters—such as hurricanes—diverts attention from the political decisions—such as failing to maintain flood defences—that are responsible for human misery (and its inequitable distribution), so blaming tragic catastrophes on more-than-human forces might constitute an evasion of political responsibility.

But what if we were to take tragedy as a genre uncertain about human imbrication in the more-than-human world?Shakespeare’s Macbeth offers a helpful example. For some critics, this play needs to be understood in human terms: for all its supernatural paraphernalia and gestures towards the natural world, it’s at heart a play interested in how toxic ideas about gender and human worth create conflict and suffering. Any attempt to explain its tragedy in more-than-human terms—for example, to see the storm that surrounds Duncan’s murder as indicative of a “natural” order violated by regicide—risks reiterating the damaging ideology that the play itself works to expose.

In my recent book, I argue instead that the tragic energy of Macbeth and a clutch of other plays from the period lies in their restless interrogation of a world whose shape and operations remain indecipherable. Precisely what bewilders varies from play to play: in some, it’s what happens after death; in others, it’s the source of human desires (including one’s own). But in certain plays, in particular Macbeth and John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, what remains beyond understanding is precisely how the more-than-human world relates to the human one.

An unwillingness to appreciate this dimension of English Renaissance tragedy might, perhaps, be ascribed to a broader failure … to recognise human entanglement in the more-than-human world.

In what respects, then, can seeing tragedy in these terms speak to our environmental crisis? In a more general sense, I think, there is value in attending to how tragedies written by Shakespeare and his contemporaries present characters in dialogue with the wider worlds through which they move. An unwillingness to appreciate this dimension of English Renaissance tragedy might, perhaps, be ascribed to a broader failure (at least in the West) to recognise human entanglement in the more-than-human world. Any response to our environmental crisis needs to begin with this recognition.

More specifically, though also perhaps more obliquely, reading tragedy in this way may be helpful because responding to the environmental crisis requires the jolt in conventional wisdom often experienced by tragic figures: it asks us to acknowledge (to paraphrase Hamlet) there that are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in the dominant philosophies of the present. Tragedy has the power to shatter our usual ideas of the world, and to replace these ideas with something more complex and expansive.

These plays do not hold out an optimistic message. But they do, I think, point to the problem: they show us how difficult it is to move beyond our usual horizons of thought, how much easier it is—to return again to Carney’s claim—to think about today than about “[t]omorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow”, to borrow Macbeth’s words.

Macbeth’s apocalyptic and nihilistic vision of the future is hardly a torch to guide us. But it might, perhaps, be considered a lightning strike illuminating the reorientation of perspective required of us.

Feature image by Marée-Breyer (Ivry, Val-de-Marne), Bibliothèque nationale de France via Wikimedia Commons. CC0 1.0

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

November 8, 2024

The crisis in the palm of our hand: smartphones in contexts of conflict and care

The crisis in the palm of our hand: smartphones in contexts of conflict and care

Smartphones are everywhere, present in daily life, yet their impact on global crises and conflicts often goes unnoticed. Research published in the July 2024 issue of International Affairs shows how these devices influence crises and the way they unfold. Held by billions across the globe, smartphones are far more than tools for communication—they shape how we experience and react to the major events around us.

The Smartphone: A Security Device?Smartphone devices have moved beyond simple communication tools and become a critical part of modern security landscapes. Their influence on international affairs is profound, woven into our lives in ways no previous device has managed. As of 2029, it’s predicted that more than 6 billion people will use smartphones, making them a major channel for accessing information and staying connected, especially during times of upheaval.

Across global conflict zones from Ukraine, Somalia, and Mali, smartphones have become an integrated part of conflict and crisis. In Somalia, upon arrival in a rural village, elders who would once greet outsiders with a stick in one hand, would now greet us with a stick in one hand and a smartphone in the other. The widespread adoption of smartphone technology, particularly the messaging app WhatsApp, has led to the emergence of “platform kinship”, a phenomenon that significantly challenges the state’s authority and traditional governance structures. In Ukraine, civilians utilize smartphone apps like e-Vorog and ePPO to report Russian troop movements, aircraft activity, and even missile launches, blurring the lines between citizen and combatant. And in Mali, influencers—so-called videomen—through smartphone technology play a central role in building popular support for Mali’s military regime and its intensified military cooperation with Russia. So, whether it’s keeping up with breaking news, sending warnings, or mobilizing resources, this handheld technology plays a pivotal role in how crises are both managed and experienced.

Looking Beyond Social MediaWhile research often focuses on the role of social media during conflict, the smartphone itself deserves attention. Its unique blend of capabilities influences how crises unfold. Some key aspects we highlight in this Special Section are:

Speed: Smartphones have drastically increased the speed of communication, especially in emergencies. Information is now transmitted almost instantly, shaping the public’s perception of events and affecting responses as they happen. This rapid flow of news can mobilize support, raise awareness, or, conversely, fuel tensions and escalate violence.Audiovisual Capabilities: Communication is no longer just text messages and phone calls. The ability to capture and share images and videos has transformed the way crises are perceived. A single photo or video clip, shared on a platform, can expose human rights violations, shape international opinion, and impact the outcome of conflicts. Yet this is not always positive. These same visuals can distort facts, spread misinformation, and leave lasting psychological effects on those who witness the horrors of war through their screens.Scalability: With smartphones, distance is no longer a barrier to participation. People far from the physical site of a conflict can still contribute, raise funds, or join protests. Indeed, the proliferation of apps makes it possible for hundreds and thousands of people to communicate and organise collective action. This global participation has fundamentally changed how crises play out. Movements are no longer confined to those physically present in affected areas—anyone with a smartphone can take part.Together, we argue, these three features produce new degrees of global interconnectedness that shape how contemporary crises unfold.

Global Crisis EcologiesThis interconnectedness has led to a new way of thinking about crises—where events are not contained by borders but shared, followed, and influenced by people worldwide. These devices have helped blur the lines between those in conflict zones and those far from them, creating what we call global crisis ecologies.

As smartphones link people across continents, they challenge traditional ideas about the geography of crises. A conflict in one region can be experienced in real-time by people on the other side of the globe, making it a truly global event. This expanded participation can shape the course of events, as those far removed from the physical site of a conflict can influence narratives, provide aid, or even fuel further tensions.

Conflict and CareSmartphones are tools of both care and conflict. They have proved essential in coordinating humanitarian aid, documenting abuses, and providing communities with vital information during disasters. Through apps, instant messages, and group chats, those in crisis zones can connect with resources and share their stories with a global audience.

Yet, these same devices can be used in harmful ways. Misinformation spreads as quickly as facts, and online platforms can fuel hate speech and violence, whether in the UK or the DRC. The ability to track, record, and manipulate through smartphones has also raised concerns about surveillance and the loss of privacy.

On 17 September 2024, we observed this in Lebanon, where pager attacks targeting Hezbollah have deepened mistrust among the Lebanese population and heightened social anxiety. In the months leading up to these attacks, Hezbollah leader Sheik Hassan Nasrallah had warned that smartphones were being used as surveillance tools by Israel, prompting Hezbollah commanders to abandon smartphones in favour of pagers.

Implications for Policy and ResearchThe rise of smartphones has significant consequences for policymakers and academics alike. It requires a shift in thinking, recognizing that these devices are not just means of communication, but integral parts of modern conflicts. To address the challenges posed by this new digital reality, there needs to be a deeper understanding of the link between smartphones and global crises.

For governments and international organizations, this means adapting policies to better regulate digital tools in crisis settings. For scholars, the widespread influence of smartphones suggests a need for more interdisciplinary research. These devices affect international relations, conflict studies, media analysis, and more. The smartphone, in its many roles, must be examined as part of the broader landscape of global crises.

ConclusionThe smartphone, once seen as a simple communication device, is now a key player in shaping how crises unfold across the globe. From speeding up the spread of information to connecting people far and wide, these devices have redefined how we experience global events. As billions of people hold this technology in their hands, the way we understand, react to, and engage with crises has fundamentally changed.

Featured image by Marwan Ahmed via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers