Oxford University Press's Blog, page 12

December 18, 2024

Rethinking migrations in late prehistoric Eurasia

Rethinking migrations in late prehistoric Eurasia

People move. Whether at an individual or group level, migrations have been a constant and fundamental component of the human journey from its very beginnings to the present. To paraphrase the French scholar Jean-Paul Demoule, the story of humankind is one of three million years of emigration and immigration. While news about migrations have become a daily feature in the media, discussions concerning the regulation of the flow of people across countries and continents represent a key issue in current political discourse. Due to its time depth, archaeology is in an advantageous position to provide long-term insights on the topic. Thus, a deep history approach can counteract isolationist narratives, show the complexity of human mobility in the past and present, and illustrate the challenges and opportunities that can arise.

Over the last few decades, archaeologists have made enormous progress in the study of past migrations. This is largely due to the development of new, and the improvement of existing, biomolecular scientific methods that are revolutionising our knowledge of past mobility.Ancient DNA and stable isotope analyses are particularly important in this regard, although their results need to be interpreted in combination with theoretically-informed approaches and a good understanding of the archaeological record. This requires a truly interdisciplinary approach, incorporating the humanities, and social and natural sciences.

Humans have always been mobile. Even travelling to foreign lands in order to stay there for a long period of time (a more permanent migration) has been part of human existence over the millennia. However, the scales, rhythms, motivations, and characteristics of these migrations can take very different forms. Where bioarchaeological approaches have been applied, they have contributed to identifying previously unimagined scales of mobility, but sometimes also to uncovering subtle nuances at a local, even individual level. A good example is the study carried out by Philipp Stockhammer and Ken Massy in the Lech Valley (southern Germany). Their comprehensive bioarchaeological analysis of graves dating from the 3rd and early 2nd millennia BCE has allowed the identification of several female individuals of non-local origin, as well as the determining of the biological relatedness of the people buried in the cemeteries. While this represents an example of a very detailed study of a microregion, on the other end of the spectrum we have Volker Heyd’s contribution analysing several large-scale migratory processes of the 3rd millennium BCE at a European scale. This was a period of significant population mobility, which the author compares with the historical Migration Period of the 4th to 6th centuries AD. Bioarchaeology does not only allow these sorts of prehistoric migrations to be traced, but can also shed light on other aspects such as marriage and motherhood, as Katharina Rebay-Salisbury explores.

When we move into the 1st millennium BCE, the increasing availability of written sources allows fruitful comparisons between archaeology and texts. While this task is not without challenges, it can offer new perspectives on topics such as the ‘Celtic’ migrations to Italy. The latter are addressed by Peter Wells in a paper that also includes comparisons with later historical population movements, including the Early Medieval Anglo-Saxon migrations to Britain and the Early Modern migrations of Puritan English to New England. Demographic fluctuations and migratory processes could sometimes be the result of aggressive policies by expanding imperial powers, illustrated by Nico Roymans and Diederick Habermehl’s work on the impact of Rome on the Lower Rhine frontier region in the period from Caesar to Augustus.

The selection of examples mentioned above clearly demonstrate the potential of archaeology to contribute to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of past migrations. Although lookingat the past, in itself, does not necessarily guarantee the right answers to current global challenges, it at least allows us to place debates into perspective, helping to counteract simplistic approaches and modern political misuses.

Featured image by Klearchos Kapoutsis via Flickr.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Jolly Yule

As I have said so many times in the past, I avoid discussing words and phrases whose origin can be found in any dictionary or (even better) online: one click, and all the information is there. But today, I could not resist the temptation. This is the last post of 2024. As usual, at this time of year, we’ll have a break until early January, and this is the time for the Oxford Etymologist not only to thank our readers and correspondents for their interest and loyalty but also to express the hope that 2025 will be (if possible) even happier than 2024. When we meet (“reconvene”) next time, nights will be a bit shorter, the sun a bit higher, and some etymologies (or so I hope) more transparent. And perhaps someone will explain to me why, in the phrase this time of year no article is needed before year. So already in Shakespeare’s immortal Sonnet 73: “That time of year thou mayst in me behold…”

A Happy New Year!

A Happy New Year!Image by Kelly Sikkema via Unsplash.

And now back to jolly Yule. It is a disconcerting circumstance that both words in that phrase are of unknown origin. Let us begin with Yule. Apparently, all or most of the earliest speakers of Germanic knew this word. I constantly mention fourth-century Gothic in this blog. But it is not only parts of the Gospels that have come down to us in that old (now dead) language. Miraculously, a fragment of the Gothic calendar, from October 23 to November 30, is also extant, and in it, we find the phrase fruma jiuleis and its equivalent in Latin, namely, naubamibair. It may not be immediately obvious that the odd-looking last word is “November.” By contrast, fruma is a well-known Gothic preposition or adverb, meaning “before.” Thus, November precedes Yule. Everybody will agree.

Words related to jiuleis have come down to us from Old English and Old Icelandic. The Old Icelandic noun jól is especially well-known because of its common occurrence in the texts. The festival lasted twelve days. (Think of Epiphany and Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.) The noun was a neuter plural, and it is still that in Modern Icelandic, where it means “Christmas” (one reads on Christmas cards: “Gleðileg Jól”). Icelandic is full of such neuter forms that never existed in the singular. The Old English cognate of jól was also neuter. The word’s story seems to have begun with the plural. For comparison: the Russian word svyatki “Yule” exists, likewise, only in the plural. Its Old Russian singular form must have been a secondary formation.

To repeat, the origin of the word Yule has not been discovered. The reason may be that no one knows what to look for. When the etymology of a word like yell or yelp is discussed, the clue immediately suggests itself. Sound-imitative? Perhaps. But what was gēol ~ jól? We only know that in Old English the forms gehhol ~ geohhol also occurred and that the word was borrowed into Finnish as juhla “festival; holiday.” But geohhol, which must have developed from jehwla or jegwla, is fully opaque. Since Yule is an ancient pagan festival, it cannot be synonymous with epiphany, but may allude to the movement of the sun, light, winter, spring, among others.

Predictably, the words that have been suggested as possible cognates of Yule follow that line of thought. Among them, we find a few for “sacrifice,” “(religious) festival,” and “joy.” One candidate is joke, from Latin iocus, but the origin of iocus is far from clear. The common reference to a verb of speaking as the etymon of joke looks unconvincing because words for “joke” usually come from a lower register and imply vulgar fun, entertainment, and the like (“speak” is too colorless for this situation). Thus, joke looks like a poor choice. Besides, let us repeat: a word of unknown origin cannot throw light on a similarly obscure word.

The other suggestions are seldom more promising. Among the candidates for the sought-for etymon, we find words referring to “darkness” (that is, the end of darkness?); “witchcraft” (because pagan rituals were associated with supernatural forces?); “shaft, pole” (with reference to turning, that is, to the turn of the season); “wheel” (this suggestion again reminds us of turning, but it has to overcome a few almost insurmountable phonetic difficulties); “game, amusement” (another fine idea, but Greek epsía “entertainment,” cited in this connection, is again a word of unknown origin and can provide no help in our search). One of the hypotheses listed above may be correct, but proof is wanting. Therefore, most dictionaries remain noncommittal (“origin unknown/uncertain”). A noticeable exception is the great and authoritative dictionary of Indo-European etymology by Julius Pokorny. It refers Yule to the verb of speaking (see above). Some sources repeat this suggestion, but despite Pokorny’s fame, it should be taken with a grain of salt.

A jolly good fellow.

A jolly good fellow.Image by Townsend Walton via Unsplash.

And where does English jolly come from, and why is it part of our story? This word was borrowed into Middle English from French (today, the French form is joli; originally, it was jolif). Therefore, we are interested only in the etymology of that French adjective. Friedrich Christian Diez, one of the founders of Romance historical linguistics, derived the adjective from Old Icelandic jól (that’s why jolly is mentioned in this post!), and his etymology can be found in many dictionaries, both Romance and English. It aroused a mixture of amazement and anger in Henry Sweet because he failed to understand how Scandinavian j (that is, the first sound we hear in English Yule) became English j. Of course, one can imagine that jolly was influenced by words like joy, but this is a risky hypothesis. The phrase Merry Christmas postdates the appearance of jolly in English by many centuries. A Christmas Carol by Dickens was published in 1843, and strange as it may seem to us, the extravagant celebration of Christmas in the English-speaking world goes back to the unparalleled popularity of that tale, though of course, even earlier, no one believed that Christmas is “humbug,” as Scrooge put it.

William W. Skeat, our great etymologist, shared Diez’s derivation of jolly. By contrast, Ernest Weekley did not. He wrote in his dictionary: “The Old French and Middle English meanings are very wide, and intensive senses, e. g. jolly good hiding, jolly well mistaken, can be paralleled In Modern French.” He also devoted a short piece to the word in a letter to Notes and Queries. Modern dictionaries usually mention the derivation of jolly from Scandinavian but predictably, with some hedging. This seems to be a proper attitude. Good etymology is based on good phonetics (see also above).

Enjoy!

Enjoy!Image by Mathieu MD via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

What a way to finish a year of blogging, what a miserable gift: two words of unknown origin! But look at it from a different point of view: it is better to be busy than bored, and here we have another twelvemonth and so much interesting work to do. Among other things, we are called upon to discover the TRUE origin of Yule and jolly! To follow this call will be a perfect New Year’s resolution. And to be sure, our present ignorance cannot spoil our enjoyment of the inimitable julkage ~ Yule log ~ Yule cake. Jolly St. Nick says: “Bon appétit!” I join him.

Featured image by Michael Rivera via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 16, 2024

A look behind the curtain at the best books of 2024

A look behind the curtain at the best books of 2024

Every year, Oxford University Press’s trade program publishes 70-100 new books written for the general reader. The vast audience for these trade books comprises everyone from history buffs, popular science nerds, and philosophy enthusiasts pursuing intellectual interests, as well as parents and caregivers seeking crucial advice or support—all readers browsing the aisles of their local bookstore (or the Amazon new releases) for literature that deepens their insight into the world around them.

Oxford editors from across our press submit books for catalog consideration; our sales team evaluates forecasts and sales patterns to determine the market for each title; and the trade marketing and publicity teams coordinate, plan, and pitch to get these titles in front of readers. Each year, when December rolls around, we excitedly wait to see which titles will be featured in the year end “Best Books” lists put out by the major media outlets including The Telegraph, The New Statesman, The Economist, The New Yorker, TLS, and more. Inclusion on these lists serves as yet another seal of approval, highlighting the quality of the content, wide appeal, accessibility, and novelty of the books we publish. Being featured in such reputable lists and selected by the top critics and thinkers reinforces the press’s reputation for publishing high-quality, impactful work.

This year’s list includes the first ever history of the transition from the Tudors to the Stuarts by a Professor at the University of Oxford; the final book by the prolific writer John L. Heilbron—the definitive account of the great Bohr-Einstein debate; a collection of nine tales of romance and wonder from early Irish literature; and a deep dive into the mysterious origins of words by arguably the greatest living English word-hunter.

As the world’s oldest and largest university press, OUP holds an important place in the publishing landscape. The press’s mission is an extension of the university’s—we strive for excellence in research, scholarship, and education through our global publishing program. A crucial aspect of the trade team’s role is making sure that the work of Oxford’s academics and scholars isn’t kept solely within the confines of academia, but instead is shared with the wider population. Through the use of accessible and engaging writing, OUP’s trade books share the expertise of highly qualified researchers with the general public, allowing new ideas to spread and reshape our knowledge of the world.

The ‘Best Books’ lists which numerous major media outlets share annually represent the capstone of yearly book coverage. All year, publicists submit books to hundreds of newspapers, magazines, radio stations and other outlets for review, excerpt, author interviews and news coverage. In the last 12 months, the New York Times (with its 153 million reported unique visitors per month) covered 18 of OUP’s titles—including a review of Making the Presidency which drew comparisons between John Adams and Kamala Harris’s legacy, and an Op-Ed by the authors of Wreckonomicswhich asked when liberals became so comfortable with war.

Beyond the Times, in the last year 11 books were featured or reviewed on the BBC, 19 in the Wall Street Journal, 15 in the Times Literary Supplement, 11 in the Financial Times, 8 in the London Review of Books, another 11 in Time Magazine, and to the delight of the author, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order was recommended on Oprah Daily. These reviews are truly just the tip of the iceberg in publicity campaigns that also include hundreds of podcasts, local media coverage, and events that bring authors directly into communities. The additional visibility a book receives when it is reviewed in major outlets often translates to significant boosts in sales and allows authors to extend the size of their audience and the reach of their message. This visibility is also many authors’ first exposure to OUP’s range of publishing and can be instrumental in attracting future authors that help the program grow and diversify.

Each year’s list of best book serves as a distillation of our collective questions and priorities as a society. Trade publishing must be more agile than traditional academic publishing because every title has to tap in to at least a certain portion of the zeitgeist. As a reflection of preoccupying questions, last year’s list was topped by Kirkus’s selection of Trans Children in Today’s Schools, as well as both Defectors and The Ruble from our Russian and Soviet history lists. This year, different trends have clearly risen to the top of readers’ consciousness. The New Statesman (in their seasonal lists released throughout the year) have selected not one but two Oxford books on AI. The AI Mirror by Shannon Vallor—a former AI ethicist at Google—offers advice on reclaiming our humanity in the approaching age of machine thinking. AI Morality edited by David Edmonds is a collection of essays from leading philosophers exploring some of the nearly endless questions about our changing relationship with AI.

Similarly, this year’s list includes two titles about China. The former prime minister of Australia Kevin Rudd’s book On Xi Jinping and Oriana Sklyar Mastro’s Upstart both provide informed perspectives on China’s role in the global world. When asked why she chose to write her second book for a general audience, Dr. Mastro points out that China’s power has impact far outside of academia and she wanted to make sure her work could reach readers in all walks of life.

The support that the trade marketing and publicity teams provides authors is crucial to strengthening their careers. Debut authors utilize our platform to both benefit their scholarly careers through the academic prestige the Oxford brand provides while simultaneously developing their presence as a noted subject matter expert in the media. This recognition grows in tandem with the author’s career, allowing the Oxford trade program to retain successful authors as well as attract well-established authors who haven’t previously published with us.

This year, COMBEE by Edda L. Fields-Black was selected as one of The New Yorker’s recommended titles and among The Civil War Monitor’s Best Civil War Books. Dr. Fields-Black is a direct descendent of one of the hundreds of formerly enslaved men who liberated themselves after the Battle of Port Royal and joined the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers to fight in the Combahee River Raid along with Harriet Tubman. Only her second book, and her first written for a wide audience, it was essential to Dr. Fields-Black that she had an opportunity to share both her research and also her family’s story.

On the other end of the spectrum, the trade team works with many authors and scholars who are well-established in their careers and come to OUP with ample experience and high expectations of the publishing process. Our team was honored to have the opportunity to work with Noel Malcolm on his 12th book Forbidden Desire which was named by both The Times Literary Supplement and History Today as one of the best books of 2024. Malcolm has published across academic and trade publishing houses during his long career, and it was important that we be able to provide him with the highest level of marketing and publicity possible.

All of the books published by Oxford are the culmination of years of work on the part of the authors, research assistants, editors, designers, marketers, and publicists. Each one is an accomplishment that has the potential to move knowledge forward. The books in our trade program—with their potential to speak to all readers—represent a unique opportunity to inform, illuminate, and entertain. Join us in celebrating the best books of 2024.

Featured image by clu, Getty Images via Canva. Image modified in Canva.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 15, 2024

Does “the” get italics?

One of the idiosyncrasies of copy editing that befuddles me involves the word “the”. Should it be capitalized and italicized when one refers to newspaper titles in a piece of writing?

The Chicago Manual of Style will tell you no. Its advice, which I always have to recheck to be sure, is that:

When newspapers and periodicals are mentioned in text, an initial the, even if it is part of the official title, is lowercased (unless it begins a sentence) and not italicized.

CMOS illustrates with a hometown example: “She reads the Chicago Tribune on the train.”

Something nags at me though. Isn’t the “the” part of the title? If you look at the mastheads of newspapers, from Seattle to Boston to Atlanta, you’ll often find “the” capitalized, in blackletter gothic font. So why not treat it that way?

Puzzling over this, I’ve come up with four reasons. One is that “the” is omitted when another article or a possessive is used. We write “a Chicago Tribune reporter” and “her New York Times (that is, her copy), but never “a The Chicago Tribune reporter” or “her The New York Times.” Ugh. And when we write something like “the Boston Globe story that won the Pulitzer,” the “the” is modifying “story” not Boston Globe. Since the titular “the” drops away in such cases, it would create confusion (and a lot of work) to sometimes italicize it and sometimes not.

In addition, not all newspapers use a “The” in their mastheads. Take a look at the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the Arizona Republic, all of which eschew “The.” It would be confusing to italicize “the” for some newspapers and not for others—and writers would need to look up which is which. That’s too much.

Then there is the index factor. When you create a book index containing lots of titles that begin with “the”, that little word is conveniently suppressed. Otherwise, the section of the index beginning with “the” would be large, unwieldy, and simply ridiculous. Omitting italics and capitals in the main text and in references is consistent with the necessary suppression of “The” in indexes.

And finally consider the fact that many other names of institutions, bands, bits of topography or geography, like the Rolling Stones, the White House, the Washington Monument, the Pyrenees, the Great Lakes, the Capitol, and so on all use a lowercase “the.”

Occasionally we find exceptions where “The” is capitalized as part of a name such as The Hague (a city in the Netherlands) or The Dalles (a city in Oregon) or The Ukraine (back when it was a Soviet region rather than an independent state). But such exceptions are few and far between. “The” is generally lowercase.

One prominent exception is The Ohio State University, which insists on the “The” being present and capitalized. Presumably it does not wish be confused with other OSUs, like Oklahoma State University or Oregon State University. The institution has been using a “The” for many years and even trademarked “The” in 2022. Unfazed, The Chicago Manual of Style, writes that it “disregards such outliers for the sake of consistency with other such names.”

You’ll notice that in the last sentence, The Chicago Manual of Style got both italics and capitals. According to them, that’s because “The” is part of a book title, so the first word is capitalized and the italics extend through the title.

Perhaps the New York Times should look into this.

Featured image by Gabriele de Sanctis via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 11, 2024

Varia

In addition to a huge database (the physical files stand in my office, while the juice of the papers has been preserved on my computer), I have a heap of curious notes on language and etymology that I can use for neither my publications nor for this blog: just odds and ends. Sometimes I feel sorry that they are dying in their obscurity. For example, I walk into a store and read: “Bright, juicy and a beloved staff favorite citrus.” Quite a gem: a beloved citrus! Or is the staff beloved? Beloved-staff or staff-favorite? And why did the indefinite article crop up only in the middle of the phrase? In another store, I read: “Employees only beyond this post.” What is meant: “Employees: only beyond this post” or “Employees only—beyond this post”?

Of course, I am saying it all tongue in cheek, pretending that I cannot understand those signs, but still…. Incidentally, the phrase tongue in cheek surfaced in print only in the nineteenth century (Walter Scott was the first to use it) and does not seem to have analogues in other European languages. I have been unable to find any discussion of its origin. Was the gesture meant to be obscene? A variant of “giving one thefinger”? Any protruding part of the body may arouse similar associations. Sex and humor are inseparable.

Or to return to a paper by Jeremy Bergerson (2004) about emphatic –s in Modern Germanic (I referred to it in the post on buddy of June 21, 2023). The paper is full of curious and non-trivial data. One of the most memorable -s words is the interjection shucks! (an expression of embarrassment or disappointment). Its etymology is known. The OED online devotes one short line to its origin and refers to the source, but I think the word deserves a more detailed explanation. Old English scucca ~ scocca meant “devil” (see the image in the header!). The long consonant (-cc-) was used for emphasis (a typical feature of “emotional” words). Like many old religious terms, scucca has a respectable ancestry. The word skohsl “evil spirit, demon” occurs In the fourth-century Gothic text of The New Testament (Gothic is a Germanic language; it is now dead); –sl is a suffix. Scocca and skohsl share the same root.

A work hard to overlook.

A work hard to overlook.Image by Philafrenzy via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Surprisingly, even the 1986 etymological dictionary of Gothic says, “no Germanic cognates,” though scucca ~ scocca can be found in all dictionaries of Old English. Moreover, shuck “evil spirit” is still known in British dialects, and in 1936, Mary S. Serjeantson, a first-rate specialist in the history of English words, mentioned it in the widely read periodical Folklore. Finding such crumbs of information is hard. I keep returning to this subject because I know from bitter experience how much precious information on etymology lies fallow in runaway sources. Now an exhaustive bibliography of English etymology exists, but some researchers keep ignoring it. Last week, I mentioned the sad fact that in the not-too-distant past, some people interested in etymology were unaware of the OED, a work hard to overlook. See also the end of this essay, which is very much in tune with what I have just said.

A thicket, coppice, copse, shaw.

A thicket, coppice, copse, shaw.Image by Shankar S. via Flickr. CC BY 2.0.

Even though specialists in Gothic missed the evidence of English, Celtic cognates of skohsl were discovered long ago, and several hypotheses explaining the origin of the word exist. They need not bother us here. Perhaps the reference was to shaking (shake goes back to skak-) or to the root of a word like the little remembered English noun shaw “thicket, copse” (hence the family name Shaw: compare the family name Wood). Skohsl as a forest spirit? Perhaps. Today, copse is as obscure as shaw, though its doublet coppice still occurs in printed sources. However, it is not shaw but shucks that interests us. Here is a fact worthy of surprise. An ancient demon of Indo-European (or at least Germanic-Celtic) antiquity survived in English rural dialects (shuck), migrated to our colloquial speech, and developed into an interjection. Did shucks! once have an apotropaic function? Did people say shuck-shuck-shuck to avert evil? Today, that sense is perhaps still discernible in shucks, but -s adds a tinge of familiarity to it, so obvious in digs, Boots (the youngest son in British folklore: no connection with any type of “footwear”), and names like Toots (Mr. Toots is an endearing character in Dickens’s novel Dombey and Son).

Many etymologies are probable but not certain, and it is useful to know all conjectures, even if they are dubious. Here is a case in point. A colloquial expression dry beating exists. It means “a sound beating.” In the past, the phrase was common. Why dry? The usual explanation suggests that a dry beating does not (did not) involve bloodshed. In 1915, G. C. Macaulay (Cambridge) published a note in the periodical Modern Language Review (Vol. 10, 224-225), in which he questioned this etymology, and indeed, in the sentences from Middle English he cited, dry beating means only “severe” and has nothing to do with avoiding blood. Consider his dynttes were full dreghe “his blows were very dry/severe.” Dreghe is of course “dry” (plural). Dynt has also survived, but only in the phrase by dint of, that is, “by means of.”

This is a dry beating. How dry?

This is a dry beating. How dry?Image by British Library, Europeana via Picryl. Public domain.

It is indeed strange that dry (“bloodless”?) developed the sense “severe,” even though stranger things happen in historical semantics. G. C. Macaulay suggested that this dry “is connected of course with the stem of Old English drēogan.” The verb drēogan meant “to endure, suffer.” It disappeared from Modern English and was revived by Walter Scott in the form dree. To dree one’s weird means “to accept and surrender to one’s fate” (the tremendously overworked modern adjective weird is the same word). Macaulay should not have said of course. This obnoxious word often means: “There is no proof, but what proof is needed? Isn’t everything quite obvious?” At the moment, I have no opinion on dry beating and only have trouble with Macaulay’s treatment of vowels, but I believe that his conjecture should not be lost. To repeat: astute conjectures are strewn all over the place, and many of them go to waste.

On the same note, consider the following. In 2015, Juha Janhunen wrote a short article, titled “Etymology and the Role of Intuition in Historical Linguistics” (Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia 20, 9-15). He connected two words that on the face of it have nothing in common and thought that he was the first to offer this reconstruction. But later he stumbled on a 1933 publication that contained the same idea (and the journal was not one of those obscure sources nobody remembers!). However, he writes, this “publication was totally ignored by the standard textbooks. Only after I had independently arrived at the same conclusion half a century later, has the idea become more widely known. It may be another half a century for the correct explanation to win its place in the pool of generally accepted etymologies.” Shucks! Or should I say: “Fie!”

And now back to the previous post on the word bloody. The comments suggested that the word might be connected with menstruation. If it originated in Norman French, we may indeed think of taboo on everything, connected with the woman’s periods, but is the sense under discussion so old?

Featured image by Aden Kowalski via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 10, 2024

Morality without metaphysics

Let’s talk about morality. There is stuff we think is okay to do and there is stuff we think is not okay to do. Human relationships work (when they do work) when we are all more or less on the same page about what stuff is and is not okay to do; as we often are. We all agree, for example, that it is not okay to beat people to death because you do not like the way they dress. We expect others to obey such rules and our relationships with them are shaped by whether or not they do so. We hold each other responsible for what we do in ways that inform how we distribute, on the one hand, our love and esteem and, on the other, our condemnation and resentment.

This is the everyday world of moral common sense but there are always sceptical voices: perhaps it’s just nonsense. Can there really be truths, proper objective truths about what is and isn’t okay just the way there are objective truths about chemistry and geology? Some people argue that it makes no sense to suppose there are moral truths somehow baked into the constitution of the universe, radically independent of human beings and our moral experience, and so morality is nonsense.

I argue that while that rather grandiose metaphysical picture is indeed false, the best way of understanding our moral common sense presupposes nothing so fancy nor so fanciful. There need only be human beings jointly committed to a shared enterprise of living together in peaceful and orderly moral community regulated by norms of justice and civility that we can justify to each other in a shared currency of reasons shaped by and expressive of our passionate natures. It is not so complicated. For many good reasons, I don’t want to live in a world where we say it is okay to beat someone to death because you do not like the way they dress. Neither do you. So let’s not.

All the moral reality we need is something far more human, far closer to home.

This enterprise is hard and many problems challenge it on every side. Moral consensus can be fragile and imperfect. (Shamefully, some people — the late Mahsa Amini comes to mind — have been beaten to death by people who did not like the way they dressed.) But it is nonetheless not an enterprise whose intelligibility and feasibility require our moral norms to be ratified by any such radically independent domain of moral reality. All the moral reality we need is something far more human, far closer to home, something that, if we get it right, can be as true and as objective as it needs to be.

Responsibility is another headache. Here the most familiar problem concerns what is often called free will. Can I be responsible for what I do if I am not the author of what I do? It may seem obvious that ordinarily I am. Only a worry sets in. What I do is shaped and determined by me, my choices, my desires, my plans and my values. But I, along with my choices, desires, plans and values, was in turn shaped and determined by the social and natural forces that made me what I am — forces ultimately external to me that were already decisively in play long before I was born. Many are troubled by the pressure of such metaphysical reasoning that seems to rob us of the authorship of our own agency responsibility would seem to require.

I was shaped and determined by the ultimately remote social and natural forces that made me what I am. And yet, that may not always matter. I am no less, for that, the author of these words in these sense that they express what I believe and who I am and I am willing to sign my name to them, to own them, to accept that you act justly and properly in holding me responsible for framing them.

I don’t, for many good reasons, want to live in a world where it is deemed okay to beat someone to death because you do not like the way they dress. And neither do you. We didn’t chose for our moral sensibilities to have the long causal histories that made them what they are. But we can nonetheless choose now to sign up to them and why wouldn’t we? Of course we don’t want that world. I am happy enough to be in a social contract with you where we undertake to refrain from such sartorial homicides and where I accept my liability to be held responsible should I ever break that undertaking. I didn’t choose to be the person that I am but the person that I am can choose to embrace such a norm, and he enjoys, in normal circumstances, sufficient self control for his choices to determine what he will do. (And the norms that govern responsibility make due allowances for abnormal circumstances.)

The enterprise of making a moral community is still hard. But the difficulties are practical, not metaphysical. The things that we do and say to each other are not arbitrary. We justify them inside the space of reasons. The space of reasons as a whole is expressive of the contingency of who we are and what we are like. Does that contingency entail a kind of ultimate arbitrariness without a strange domain of morality guaranteeing our cheques? Do we just happen to be the kind of animals to prefer justice and kindness to injustice and cruelty? I guess we do but it is a contingent thing we nonetheless cheerfully embrace and own. We did not ultimately choose to be this way, valuing these things, but, being as we are this way, we still sensibly chose to live in a community of responsibility which these values shape. We don’t stop loving the things we love just because it is ultimately contingent that we are the kind of creature that loves the kind of things we do.

Featured image by FlyD via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 9, 2024

The idea of Europe

In the decades around 1800—when the European past was (as in the present) the topic of fierce discussion, contestation, and political (ab)use—ideas of Europe were dominated by the shocking events of the French Revolution and its violent aftermath in Europe and beyond. The European order as well as Europe’s place in the world, was destroyed, rebuilt, and redefined at this moment. Perhaps comparable to the memory of the Second World War and the Holocaust in the twentieth century, the French Revolution and in particular the Terror, acted as a ‘foundational past’ for inhabitants of the long nineteenth century until the First World War.

In the age of eighteenth-century revolutions—just as after the world wars of the twentieth century—contemporaries turned to history, that of their own lives as well as that of society, to make sense of a confusing and troubling world, where previously unimaginable possibilities as well as horrors had opened up. The European past and the idea of Europe as an essentially ‘historical continent’ was (re)invented by the critics of the French Revolution as part of their ideological struggle against the Revolution: an imagined ‘Europe’ was positioned against ‘the Revolution’.

For these ‘counter-revolutionaries’, the Revolution stood for a false idea of freedom and democratic sovereignty, which led to anarchy and despotism at the same time. In opposition to the new revolutionary world of universal principles, the counter-revolutionary publicists proclaimed the concept of a gradually developing European society and political order, founded on a set of historical and—ultimately divine—institutions that had guaranteed Europe’s unique freedom, moderation, diversity, and progress since the fall of the Roman Empire.

[A]n imagined ‘Europe’ was positioned against ‘the Revolution’.

These counter-revolutionaries (ab)used and transformed an older historical narrative that had been developed in the preceding century by enlightened historians. Both the ‘Enlightenment’ and what is conventionally called the ‘Counter-Enlightenment’, or more historically accurate ‘anti-philosophy’, were sources of this counter-revolutionary construction of the European past. The importance of the decades around 1800 lay in the fact that these older Enlightenment histories became politicized in response to the perceived threat of Revolution to this European society.

It is clear that the counter-revolutionary Europeanists of the revolutionary age differed markedly from their self-appointed successors in later centuries. Counter-revolutionaries around the turn of the century were certainly not ardent nationalists, who were as horrified by ‘cosmopolitanism’ as the new ‘national conservatives’ of the twenty-first century. On the contrary, they regarded unqualified expressions of ‘nationalism’ and ‘patriotism’ as excessive, immoderate, and fanatical. The counter-revolutionary authors strove for a new synthesis of ‘enlightened cosmopolitanism’ with loyalty to the patria, whether this was a country, a city, or an entity like the Holy Roman Empire.

[O]lder Enlightenment histories became politicized in response to the perceived threat of Revolution to this European society.

Counter-revolutionary Europeanists, perhaps counter-intuitively, did not aim for a return to a primordial order of European civilisation, as the twenty-first century ‘conservatives’ often do. They regarded the Revolution instead as a threat to the gradual development and improvement of European institutions, whose reform they generally applauded. Often being migrants, refugees, and exiles themselves, they did not entertain an anti-immigration discourse. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these counter-revolutionary ideas of European history and civilisation were rediscovered and adapted to new political contexts, shaping in manifold ways our contested idea of European history and memory until today.

Featured image by Dragos Gontariu via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 6, 2024

Culture sounds the alarm: Tbilisi at the crossroads

Culture sounds the alarm: Tbilisi at the crossroads

This fall has been a season of momentous elections—and not just in the United States. Over the past several weeks, after two rounds of voting, Moldova voted to return to office its pro-EU President, Maia Sandu, as well as (despite noted Russian interference) narrowly approving a referendum in favor of Moldova joining the European Union. By contrast, in the Republic of Georgia, in a parliamentary election held on October 26 dogged with similar claims of internal and external vote-rigging, the ruling Georgian Dream party claimed a majority of the vote. These results have been strongly contested by Georgian opposition parties as well as by non-governmental observers within and outside of Georgia, who have provided numerous pieces of evidence of fraud and stolen votes. The Georgian president told multiple new outlets: “We were not just witnesses but also victims of what can only be described as a Russian special operation – a new form of hybrid warfare waged against our people and our country.” She also said, “So this is an election that has been stolen.” As a result, since the election, there have been a few protests in Tbilisi, with promises of more to come. The groundwork for these results and these events was laid well in advance: starting, arguably, in May 2024 (if not March 2023).

May 2024 was a pivotal month for the country of Georgia, marked by significant cultural events interwoven with the political and social upheavals of the time. The events that we witnessed in Tbilisi during the ongoing protests and other collective actions against the so-called “Foreign Agents Law” offer another case for testing music’s political valence. Although scholars have often discussed the politicization of music during the USSR (and, in Russia, after), Georgian music and cultural life has never been approached from the perspective of its political dimensions, even as after 1991 each successive Georgian government has continued Soviet political paradigms of music and culture.

Georgian music and cultural life has never been approached from the perspective of its political dimensions

In March 2023 the ruling Georgian Dream Party, which first came to power in 2012, first introduced the “Law about transparency of foreign influence,” colloquially known as the “Foreign Agents Law” or “Russian Law,”—legislation that aimed to require that any organization receiving more than 20% of its funding from non-Georgian sources register with the Georgian government as a Foreign Agent. A similar law had been introduced in Russia in 2011 and was one highly visible marker of that country’s recent slide toward authoritarianism. Yet in Georgia in 2023, under pressure from large demonstrations and rallies against it, Georgian Dream withdrew the law. Moreover, they promised never to bring it back.

Image courtesy of Peter Schmelz, used with permission.

Image courtesy of Peter Schmelz, used with permission.The calculated reintroduction, at the beginning of April 2024, of this law ignited a powerful response from the Georgian people. Large, at times unprecedented, numbers of protesters took to the streets of Tbilisi, engaging in near-constant, daily demonstrations (see video 1, shot by Nana Sharikadze at the Woman’s March on April 20, 2024). Once re-introduced, the law sparked a series of events that threatened the very foundations of Georgian society, both its fundamental values and its generations-long aspirations. Once again, Georgia was forced to reckon with its colonial past, specifically with the tensions between that past, the decolonizing wishes of much of its citizenry, and its potentially recolonized future, yet again in the shadow of its dominating northern neighbor. As the Georgian president, Salome Zourabishvili remarked at a concert on May 9, 2024, “Georgia is at the crossroads between its European future and its Russian past.” As Georgia stood at this crossroads, the voices of its people, amplified through music and protest, made it clear that their fight for a democratic and European future was far from over.

The political amplifications arose largely through coincidence: no one could have predicted that concerts planned well in advance would overlap with such a political and social crisis. Prime examples were concerts in Tbilisi by the Berlin Philharmonic on May 1 and 2, 2024 along with a Europe Day concert on May 9, 2024, featuring assembled dignitaries from both Georgia and the European Union. (And note that this day is celebrated by Russia, and previously by the USSR, as Victory over Fascism day, the end of World War II.)The Berlin Philharmonic visited Georgia as part of a pan-European tour of cultural and historical landmarks; the concert in Tbilisi, the EuropaKonzert, was its final destination. The orchestra played at the well-known Tsinandali Estate in Eastern Georgia on May 1. The next day they repeated the concert at the Tbilisi Opera House. These performances illustrated how established musical pieces, with their multifaceted, often contradictory historical connotations, can gain deeper and additional meanings during times of profound crisis.

Video courtesy of Nana Sharikadze. Used with permission.I (Nana Sharikadze) attended the concert at the Opera House and found it difficult to remain purely professional. By that time, I had already participated in 20 days of protests, and as I sat in the opera house, I was surrounded by many friends, acquaintances, and even strangers who I had frequently seen in the streets during those protests. The music on the program by Schubert (“Die Zauberharfe,” Overture, D. 644); Brahms (Violin Concerto, op. 77, played by Lisa Batiashvili); and Beethoven (Symphony no. 5) acquired additional resonances in such a context. (The conductor was Daniel Harding, who substituted for Daniel Barenboim.) And not just for me. The powerful, triumphant motifs and message of fate in Beethoven’s symphony drove the audience at its conclusion to shout out, in one voice, “No to the Russian law.” Their chanting filled the hall of the Opera Theatre, symbolizing the dramatic social disruptions and the enduring impact of these events on Georgian society today.

[M]usical pieces, with their multifaceted, often contradictory historical connotations, can gain deeper and additional meanings during times of profound crisis.

At that time in Tbilisi, nearly every event carried extra significance. Another such landmark was the gala concert held a week later on May 9, 2024 a few steps down the street from the Opera Theatre, at the Rustaveli National Theatre, in celebration of Europe Day. This concert featured a diverse, all-star roster of Georgian musicians from such genres as classical music, jazz, and various traditional music genres, among them jazz pianist Beka Gochiashvili, violinist Lisa Batiashvili, mezzo-soprano Anita Rachvelishvili, cellist Lisa Ramishvili, violist Giorgi Tsagareli (wearing a Georgian soccer jersey), the Georgian Philharmonic Orchestra, the Gory Girl’s Choir, pianist Giorgi Gigashvili, and pianist and composer Tsotne Zedgenidze. The concert included, among other selections, a jazz arrangement of Giya Kancheli’s “Herio Bichebo” (ჰერიო ბიჭებო, an important patriotic song, whose title is difficult, if not impossible, to translate); the Habanera from Bizet’s “Carmen”; and Nikoloz Rachveli’s “The Way Back Home” (გზა შინისაკენ). (Rachveli was the organizer and conductor of the entire concert). Again, a program of works selected long before the concert spoke profoundly to the present circumstances, using nostalgia, for home and a sense of European classicalness. And it is important to know that in the days before the concert, the violence against protesters had escalated: prominent figures found their residences defaced with graffiti labeling them enemies of the state; others were assaulted. Furthermore, just a day earlier, on May 8, the government had announced the establishment of an online registry of its enemies. (Just before the concert, one of the other audience members said to me [Peter Schmelz] in passing, “This is a bad time to visit Tbilisi.”)

We both attended this Europe Day concert and recall vividly the electric energy in the hall. It was part group therapy, prayer, and requiem, for a dream, for the hope of European integration. The press gathered in front of the building and the European delegates and Georgian President greeted concertgoers in a receiving line as they entered. Significantly, several rows of seats had been reserved for members of the government, who pointedly did not attend. Zourabishvili was the sole Georgian government representative in attendance and its sole voice. She was then, and continues to be today, a prominent voice publicly supporting Georgia’s pursuit of European values. These visibly empty seats in the center of the hall were a constant reminder throughout the concert of the tensions gripping the country over the proposed legislation, highlighting the deep disconnect between the government and the people in attendance at the concert, and by extension, large numbers of Georgian citizens. The “Ode to Joy,” the anthem of the European Union paired at the start of the concert with the Georgian anthem, formed an audible symbol of Georgia’s alignment with European values, standing in stark contrast to its Soviet past and its Georgian Dream present.

In order to reach more citizens than had been able to attend the concert, Zourabishvili organized an outdoor event with the same artists that was held immediately after the Europe Day concert in front of the Orbeliani Palace, a landmark in central Tbilisi. Unlike the concert before the more elite viewers at the theater, this one involved more audience participation. The gathered listeners became part of the performance itself, whistling in approval, and joining in song at several moments, among them, yet again, the “Ode to Joy,” when the building energy of the concert reached a peak. Before the Orbeliani Palace the diversity of contemporary Georgian society, and pointedly its youth, was on full display, unified under the idea of a European Georgia.

An essential new element also emerged in Georgia during this period of turmoil: protest music. Koka Nikoladze (b. 1989), a Georgian-born, now Oslo-based sound artist, composer, and inventor, created a piece called People. His music, an urgent, desperate cacophony, served as a powerful auditory representation of the collective plight. When I (Nana Sharikadze) first heard the sample of the music (see, esp. from 4:48 and 8:11 onward) on Facebook on May 17, I commented: “This is Georgia in the last month. I don’t know when you started working on this or what concept you have, but the whole country feels like this. This is an alarm, we have reached the point of screaming, and yet they still do not hear us. Their doors are deaf, they have welded shut, not opening; The silence of some is even more deafening.” Koka created it in April, and noted: “I was born, grew up, and have become exhausted in this environment [i.e., Georgia]. I have never felt such a sense of helplessness. I am sitting here (in Oslo), my thoughts are not responding anymore, thinking but unable to communicate.” The piece is a scream, as Nikoladze said, composed of recorded natural voices sourced and sequenced with care.

The final, third vote by 84 deputies, a majority of parliament, in favor of the bill, ensuring its passage, on 28 April 2024, felt like a betrayal of generations of long devotion and centuries of resistance, while in the streets we, including my colleagues and I (Nana Sharikadze), were screaming to be heard. The law went into effect on August 1, 2024.

Culture and politics, despite the dreams and wishes of many, remain closely intertwined.

Yet as a result of the mounting crises of 2024, and especially after the October 26 parliamentary election, Georgian society is confronting dramatic, uncertain times. The country has a clear, existential choice: between the colonial past and the decolonial future. It is a choice about surviving as a country, about whether we want to live where we belong (in the country of our birth) or emigrate. I (Nana) refuse to become an emigrant. Artists, musicians, writers, and other members of Georgian society are seriously concerned about their future in a country that has already demonstrated its intolerance of critical opinions or, indeed, of any sort of dissent. Culture and politics, despite the dreams and wishes of many, remain closely intertwined. That is why culture, artists, civil society, and all who value our democratic future are unifying on different platforms in support of Georgia’s European path, for developments free from the shadows of our colonial Soviet past.

Featured image by Giorgi Chokheli (Photographer of the United National Movement), Press Department of the United National Movement via Wikimedia Commons. CC0 1.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 4, 2024

The once unpronounceable word “bloody”

The once unpronounceable word “bloody”

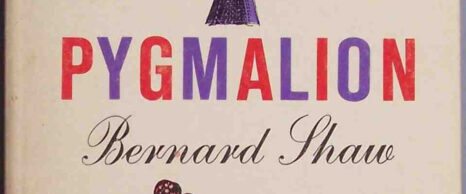

It is almost certain that the main event in the reception in England of the formerly unpronounceable “low” word bloody (which first turned up in texts in 1540 and, consequently, existed in colloquial speech earlier) goes back to 1914, when Eliza Dolittle, the heroine of George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion, uttered it from the stage. Nowadays, when in “public discourse,” the rich hoard of English adjectives has been reduced to the single F-word (at least so in the US), this purism of an age gone by cannot but amuse us. Obviously, times change, and we are changing with them. The original OED could not yet include the F-word, but bloody did make it into the B fascicle of the dictionary (1887), and a suggestion about the etymology of the vulgarism appeared there. Since that time, the entry has been revised, as anyone can see in the online edition of the OED, and I can add nothing of substance to it, but since I have a good database on bloody (collected for my Bibliography of English Etymology, 2009), some snippets from old publications may entertain those who have no better reading in their hours of indolence. I also have something to say about the word’s early history.

Bloody cold weather.

Bloody cold weather.Image by Kenny, via Flickr. CC BY 2.0.

“I think the origin of this vulgar and very revolting epithet may be very satisfactorily traced.” The writer derives this word, “which is now so prevalent with the lower classes,” “from by the Blood and Wounds of our Blessed Redeemer” (1868). A somewhat similar hypothesis traced bloody to “by’r Lady.” More to the point, at the same time, Dutch bloedig “excessive; difficult,” along with the synonymous German blutig, and the obsolete English epithet woundy “hard, very difficult,” were cited. No doubt, Murray’s OED possessed all the necessary data, but the precious slips had to wait for their hour.

Outside English, almost identical words evoked no horror, and the reference to by’r Lady did not satisfy everybody. Additionally, “Celtic, Cymric, or Gaelic bloide ~ bloighd, which signifies a piece, a fragment, a bit, or the adverb ‘rather’” (1874) came up in the discussion, but this was a dead-end suggestion. l always admire the correspondents to the British and American popular press of a hundred and fifty years ago for their knowledge of English ethnography, literature, and history: quite often, their results have not been improved since that time. Several correspondents pointed out that bloody had not always been a taboo word. For instance, it was acceptable to Jonathan Swift (1667-1745), who wrote: “It grows bloody cold.” But of course, Swift is the last author to be praised for gentility, especially in his unbuttoned moments. The adverb bloodily is also old. “He swears bloodily he loves none but my daughter” (1655, cited in 1898; the OED online has a slightly earlier example: 1649).

Bloodily in love.

Bloodily in love.Image by Gad Samuel via Pexels.

Many authors complain that the public ignores their writings. True, it is not easy to make oneself heard. But some people who express “opinions” about word origins never noticed even the existence of the OED. Both the irascible Walter W. Skeat and the much more reserved Ernest Weekley could not conceal their surprise at such a display of ignorance. In Notes and Queries 12/VI, 1920, p. 87, Weekley mentioned this phenomenon in connection with an exchange on bloody in the Observer. The OED said that though the origin of bloody is uncertain, the word probably goes back to the habits of “young bloods” (that is, young inexperienced men). Consequently, bloody drunk would have meant “as drunk as a blood.” “There is no ground” the OED continued, “for supposing that ‘bloody’… has connection with the oath ‘— ‘s blood!’.” As regards etymology, Weekley disagreed with Murray and called the word “an intensifier of the same type as awfully, thundering, etc., as suggested by the use of intensifying prefixes of Dutch bloed and German Blut.”

Weekley seems to have been close to the truth. A fine Romance scholar, he did of course mention Middle French sanglant “bloody” and noted that the word was used as an intensive, while earlier, it may have had stronger connotations. The OED did not miss sanglant either. Later research shed more light on this French word. At present, especially important is Emil Reed’s article in Notes and Queries for December 2017, pp. 517-24. He picked up where Dominique Lagorgette left off. The word seems to have emerged and flourished in Anglo-Norman, the medieval British dialect of Old French. We don’t know whether bloody also existed so early and thus served as the model for sanglant or whether the word was a genuine Anglo-French coinage. In any case, the reference to Anglo-French seems to point to the source of our word, which may have spread to medieval German and Dutch and become part of late West-European military slang. Incidentally, the previous edition of the otherwise excellent German etymological dictionary stated that the reinforcing German prefix blut– has nothing to do with blood and is related to bloß “only.” This is another “local” etymology that should be discarded. Among others, Henry Cecil Wyld doubted a connection between (young) bloods and bloody. Eric Partridge’s statement (in his etymological dictionary) that the slang use of bloody “results naturally [!] from the violence and viscosity of blood” is a bit puzzling.

A long article on bloody appeared in the periodical American Speech 6 (1930-31, 29-35) by Robert Withington. This is his opening statement: “The horror awakened by the adjective bloody, when used as an intensive in England, has long been a source of amused surprise to the American cousins across the water, who can see no reason for it….” Withington flaunted his democratic tastes with a bit of excessive fervor when he said: “To feel a distaste for a word merely because it had been employed by a rough and uncultured part of the population years ago—and for no other reason—is carrying etymological snobbery too far.” I wonder what he would have said about our laxity today. Be that as it may, he was right that the derivation of bloody from by Our Lady is most unlikely, “for who would say ‘shut your by-Our-Lady mouth’?” Of course, no one would, but the question is about the initial source of the word. Probably at no time, would by our Lady have deteriorated into bloody, and in the early seventeenth century, even the genteel speakers (that is, not only Swift) don’t seem to have been shocked by it. Withington, like Weekley, whom he quoted at length, also refused to trace bloody to (young) bloods.

Court fools were certainly not bloody fools.

Court fools were certainly not bloody fools.Image by Will R. Barnes, New York Public Library via Picryl. CC0 1.0.

In the now defunct American periodical Verbatim, one finds an amusing exchange on bloody between Eric P. Hamp and Robert A. Fowkes. Fowkes wrote: “It is even conceivable that the bloody in bloody warm is different in origin from that in bloody fool. Possibly the word belongs to that group never to be explained because the ‘special circumstances’ mentioned by Hamp have been forgotten. If they prove to be retrievable by some as yet unforeseen method, the word will obviously shed its obscurity” (No. 2, p. 21). Both Hamp and Fowkes were first-rate linguists. Unpredictable convergences do happen in word history, but reference to them will take us nowhere. For the moment, we may probably assume that the swear word bloody antedates the habits of “young bloods” by many centuries and progressed from Anglo-Norman to English, Dutch, and German (in all of which it was translated into the languages of the natives), but whether that Anglo-Norman epithet was coined by French speakers or translated from a lost Middle English swear word remains unknown.

Featured image by Dr Umm via Flickr. CC BY 2.0.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

December 2, 2024

Ten classics for your winter reading list

Ten classics for your winter reading list

One of the good things about spending more time indoors during the winter months is having more opportunities to spend an evening with a compelling book. If you are stuck on what to read this winter, we have put together a collection of ten riveting page-turners!

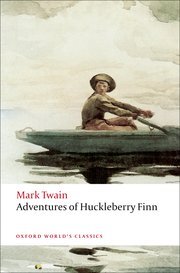

1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Get a cup of coffee and embark on an adventure with Huck, a rebellious boy, and Jim, a runaway slave. Join their thrilling escapade along the Mississippi river, where they outwit conmen, dodge danger, and challenge the unfair rules of society.

This great American novel explores a whole host of themes which are still controversial to this day, whilst taking you on a journey alongside two of fiction’s greatest characters. So, voyage with Huck and Jim and learn some life lessons along the way – and remember: “If you tell the truth, you do not need a good memory!”

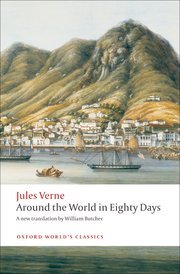

2. Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne

2. Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules VerneEver wanted to travel around the world, but just do not have the time? Join Phileas Fogg and his loyal valet Passepartout as they embark on an ambitious journey to circumnavigate the globe in just eighty days!

You will be engrossed in this novel, as Fogg and Passepartout face obstacles, navigate across diverse cultures, and build and burn bridges around the globe in this whirlwind race against time.

3. Barnaby Rudge by Charles Dickens

3. Barnaby Rudge by Charles DickensIf you enjoy historical novels, Barnaby Rudge – set during the tumultuous Gordon Riots of 1780 — is the perfect read for your winter season.

An innocent Barnaby is swept up in violent disorder, unsolved murders and dangerous, forbidden romances. You’re guaranteed to be in suspense as he paves his way through the chaos of eighteenth-century London in Dickens’ gripping tale of treachery and heroism.

4. Black Beauty by Anna Sewell

If you are looking for an emotionally sensitive and thought-provoking read, try this work of Victorian animal welfare literature. In Sewell’s socially conscious tale, the horse Black Beauty is the narrator, taking the reader from his carefree days as a foal to the harsh labour he was forced into under various owners, some crueller than others.

Through Black Beauty’s eyes, Anna Sewell explores themes of animal welfare, kindness, and the impact of human behaviour on animals.

5. Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

5. Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan SwiftEver dreamt of exploring fantastical lands? In Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift takes you on an exhilarating journey to lands of Lilliputians, giants, flying islands, and talking horses. From ridiculous rulers to topsy-turvy customs, it is a wild ride!

Each adventure is a satirical look at human nature and society. Are you ready to embark on this whimsical voyage with Gulliver?

6. The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe

6. The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann RadcliffeImagine being trapped in a mysterious, eerie castle filled with dark secrets, spine-chilling mysteries, and supernatural occurrences! In this seminal work of Gothic literature, the young Emily St. Auber faces ghoulish threats as she is imprisoned in the sinister Castle Udolpho.

Would you dare explore the castle’s darkest corridors and unravel the mysteries of Udolpho with Emily?

7. The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Step into the glittering world of 1870s New York! This is a captivating tale of love, societal expectations, and hidden desires.

The Age of Innocence follows Newland Archer, a young man torn between duty towards his fiancée and passion for the free-spirited Countess Olenska.

Will he choose his passion or conformity? Would he sacrifice his love for the rules of society? Settle in for this dazzling and heart-wrenching tale from the Gilded Age.

8. Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray

8. Vanity Fair by William Makepeace ThackerayAre you ready for a whirlwind of ambition and intrigue? Follow the cunning Becky Sharp and the sweet Amelia Sedley as they navigate love, ambition, and betrayal in the complex social milieu of 19th century England.

Thackeray’s satirical masterpiece incisively explores the moral deceit of Victorian society. Brimming with wit and drama, this book is a perfect read for your winter reading list!

9. The Romance in the Forest by Ann Radcliffe

9. The Romance in the Forest by Ann RadcliffeDo you enjoy the nights getting longer and the evenings getting darker? This is the perfect atmosphere for uncovering dark secrets in a haunted abbey! Pick up this thrilling tale of mystery and adventure and follow Adeline, an archetypical Gothic heroine, as she discovers a secret in a remote forest while fleeing danger.

Ann Radcliffe packs this tale with suspense, mysteries, hidden dangers, and Gothic intrigue. Are you ready to unravel eerie secrets with Adeline?

10. A Study in Scarlet by Arthur Conan Doyle

10. A Study in Scarlet by Arthur Conan Doyle Here’s where it all began! The grand debut of Sherlock Holmes and John Watson.

Together, the famous duo dive into the puzzling murder mystery of two Americans whose deaths have some mysterious connection to sinister groups gathering power in both Britain and America.

What starts with a baffling crime scene leads to revenge, romance, and a twisted tale across continents, marking their first iconic adventure together!

Featured image by Simon Berger via Unsplash.

OUPblog - Academic insights for the thinking world.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers