Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1041

July 16, 2012

Celebrating July: Ice Cream Month

This is an edited extract from The Oxford Companion to Food: second edition © the Estate of Alan Davidson 2012. Ronald Reagan designated July as National Ice Cream Month in 1984. You can see the official Proclamation here.

Ice cream, one of the most spectacularly successful of all the foods based on dairy products, has a comparatively short history. The first ice creams, in the sense of an iced and flavoured confection made from full milk or cream, are thought to have been made in Italy and then in France in the 17th century, and to have been diffused from the French court to other European countries. However, although the French did make some ice creams from an early date, they were more interested in water ices.

The first recorded English use of the term ice cream (also given as iced cream) was by Ashmole (1672), recording among dishes served at the Feast of St George at Windsor in May 167I ‘One Plate of Ice Cream’. The first published English recipe was by Mrs Mary Eales (1718).

The English, although they were consistently influenced by the French in adopting iced desserts and the techniques for making them, stubbornly kept to their preference for ice cream over the water ices which were more in vogue on the Continent. While they preferred ice creams, the English had remarkably few recipes for them. Mrs Eales was a pioneer with few followers; ice cream recipes remained something of a rarity in English-language cookery books (except for two which were translations from the French) until the end of the 18th century. Some authors gave no recipe; while others gave but one. The one notable departure from this pattern was by the little-known Mary Smith (1772), who gave ten recipes for ices, including Brown Bread Ice (which was in fact an ice cream) and Peach Ice Cream (which was really a water ice), thus illustrating the imprecision with which these terms were then used.

The English, although they were consistently influenced by the French in adopting iced desserts and the techniques for making them, stubbornly kept to their preference for ice cream over the water ices which were more in vogue on the Continent. While they preferred ice creams, the English had remarkably few recipes for them. Mrs Eales was a pioneer with few followers; ice cream recipes remained something of a rarity in English-language cookery books (except for two which were translations from the French) until the end of the 18th century. Some authors gave no recipe; while others gave but one. The one notable departure from this pattern was by the little-known Mary Smith (1772), who gave ten recipes for ices, including Brown Bread Ice (which was in fact an ice cream) and Peach Ice Cream (which was really a water ice), thus illustrating the imprecision with which these terms were then used.

As for America, ice cream is recorded to have been served as early as 1744, but it does not appear to have been generally adopted until much later in the century. Although its adoption then owed much to French contacts in the period following the American Revolution, Americans shared 18th century England’s tastes and the English preference for ice creams over water ices, and proceeded enthusiastically to make ice cream a national dish. In 1900, an Englishman, Charles Senn, would write: ‘Ices derive their present great popularity from America, where they are consumed during the summer months as well as the winter months in enormous quantities.’ The enormous quantities of which he wrote were of ice cream.

This phenomenon has had a curious side effect in Britain and on the Continent. In our own century the term ice cream came to mean, for many people on both sides of the Atlantic, a dish of American origin; to such a point as to reinforce the failure of antique dealers, and even of some museums, to identify their ice cream moulds for what they are.

This ‘phenomenon’ constitutes perhaps the greatest paradox of all in the history of ice cream in the English-speaking world. However, ice cream has acquired its own histories in many other regions, quite enough to fill a book but here exemplified by just a few paragraphs.

In the Indian subcontinent, where the art of milk reduction has been highly developed, ice cream is called kulfi and is made with khoya, i.e. greatly reduced milk. It is traditionally made in cone-shaped receptacles, to which Achaya (1994) refers in citing a 16th-century document about the preparation of ice cream in Emperor Akbar’s royal kitchens (with pistachio nuts and saffron). The same author suggests that the Moghuls had been responsible for introducing this frozen dessert to India, possibly bringing it from Kabul in Afghanistan, a country famous for being a crossroads between East and West. This is perhaps the place to mention the theory that early iced dairy products developed in China before AD 1000 could have travelled westwards, although not by the hand of Marco Polo, who is associated with so much culinary mythology.

In SE Asia, the prize for interesting ice creams must be awarded to the Philippines. Ice cream must have arrived there from Spain, because the old-fashioned ice cream (helado) was made in a grinder called garapinera, with rock salt and ice packed round a central container of milk etc. In modern times American-style ice creams have been dominant, but often with ‘native’ flavours such as ube (purple yam) and macapuno (a variety of coconut), but also corn (maize) and cheese — all these being sold by vendors from exceptionally colourful carts.

In the Near and Middle East there are a number of outstanding ice creams. In Iran an ice cream flavoured with salep, sprinkled with pistachios, and laced with rosewater is particularly popular although commercial production does not date back further than the 1950s. This may well have come from Turkey, where salepli dondurma (salep ice cream sometimes with mastic added) is a traditional delicacy. Salep and mastic turn up again in booza ala haleeb, the ‘milk ice cream’ of Lebanon, where another remarkable ice cream is made with apricot ‘leather’.

A world tour of ice creams could be continued indefinitely, but would probably lead always to the same conclusion, that Italy is the top country for this product. Certainly, the prevalence of ice cream parlours and vendors with Italian names, worldwide, is remarkable. However, a distinction must be drawn between the excellence of ice cream at good establishments in Italy and the quality of products sold with the benefit of Italian names outside Italy. The latter may be good, but has often been greatly inferior. The ‘hokey pokey’ which Italians sold to children in Glasgow, for example, at the turn of the century sounds fun and poses interesting etymological questions but, to judge by some contemporary descriptions, was of lamentable quality.

The Oxford Companion to Food was first published in 1999 and was followed by a second edition in 2006. Alan Davidson famously wrote 80 per cent of the Companion, which was acclaimed for its wit as well as its contents; the second edition retains almost every word Davidson wrote, and takes care that new contributions continue in the same style. It is edited by Tom Jaine, Jane Davidson, and Helen Saberi.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 15, 2012

Faith, politics, and the undocumented

The subject of illegal immigration continues to spark passionate debate across the nation, and as the 2012 election heats up, the issue can be expected to take a central role on the political stage. In a highly unusual turn of events, many religious groups — otherwise divided on social issues, such as gay marriage or abortion — have found themselves aligned in their support of immigrant rights, including brokering pathways to legality for the undocumented. While these organizations’ ideas concerning how to accomplish this goal vary (some support pushing legislation such as the DREAM Act, while others propose incorporating fines, probationary periods, straight away amnesty and other steps), Christian groups across denominational lines have backed humane immigration reform, while also condemning anti-immigrant laws such as Arizona’s SB 1070 and its copycat counterparts in other states.

For most of these groups, this pro-immigrant stance is rooted in their Christian faith and in core biblical principles such as love, mercy, hospitality, and the ethical imperative to help those who are less fortunate.

But is this position truly substantiated in the Bible? Or are the biblical stories, injunctions and teachings being taken out of context to support political claims?

Not all Christians exhibit such scripturally inspired generosity for the undocumented, as evidenced by the hard-line attitude of former GOP presidential candidate Herman Cain, who joked about constructing a fence along the whole border that would electrocute migrants, or that of Michele Bachmann, who said that even the children of the undocumented deserve nothing from us — not to mention Mitt Romney, whose unequivocal rejection of any path to legality for “illegal aliens” may cost him dearly in the election, according to many pundits.

Nonetheless, there are millions of American Christians — harkening variously from Catholic, mainline Protestant and evangelical traditions — who “share a set of common moral and theological principles that compel us to love, care for and seek justice for the stranger among us,” according to the umbrella group Christians for Comprehensive Immigration Reform.

These principles are rooted in Old Testament injunctions to love neighbor as self, including the “alien who shall be to you as a citizen among you,” as well as New Testament stories such as the Good Samaritan, which picks up on this call to love “the least of these,” whosever they may be, regardless of race, citizenship or social status. The coalitions also ground their arguments for humane border policies and merciful treatment of the undocumented in the many biblical narratives involving forced migration, uprootedness, exile, homelessness; in an egalitarian ethic rooted in the belief from Genesis that all humans are created equally in the image of God; and on the themes of justice, mercy and unconditional love woven consistently throughout the Scriptures. According to Jean Bethke Elshtain, Professor of Social and Political Ethics at the University of Chicago Divinity School, “Overwhelmingly, Scripture is filled with an imperative to offer succor and kindness to the stranger, to the bereaved, the homeless, et cetera.”

On the other hand, there are those Christians who turn to the Bible to support their anti-immigrant rhetoric, although their arguments are limited mostly to Romans 13, and a handful of other passages that emphasize the divine warrant for authority and a citizen’s duty to respect and obey the rule of law. But the faith-based immigrant advocacy groups believe that these passages are vastly outweighed by those urging radical hospitality for the stranger, as do many theologians and clergy.

“So much of the Bible and Christian tradition line up against this view; there really are not many places they [Christians opposing aid for the undocumented] can go to in the Bible,” says M. Daniel Carroll R., Professor of Old Testament at Denver Seminary and National Spokesperson on Immigration for the National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference.

Still, using the Bible to justify contemporary political convictions is inherently problematic. While the ethical impulse to dismantle unjust laws may be inspired from Scripture, as was the case, for example, when Martin Luther King engaged in civil disobedience, one must also guard against the pitfalls of proof texting — taking isolated passages out of context to legitimize a certain ideology. The problem with proof texting is that it disregards the original intent and context of the author. As Elshtain says, “Scripture could in no way have imagined the modern nation-state, issues of borders and citizenship and all the rest.” The idea of democracy, she points out, is a modern concept, and so too the idea of the state and meaningful membership in a state as a citizen; proof texting, then, can lead to irresponsible, even dangerous, conclusions.

“Since the Bible can be used to justify anything such as slavery, racism, bigotry, anti-Semitism, war and even anti-immigration sentiments, proof texting in immigration debates is futile. The Bible cannot be used as some kind of divine answer book for complex problems like migration. But it can challenge the operative narrative in our minds and hearts that affect how we evaluate the issues,” says Daniel Groody, Catholic priest and Associate Professor of Theology at Notre Dame.

As the National Association of Evangelicals’ latest immigration resolution put it: “The Bible does not offer a moral blueprint for modern legislation, but it can serve as a moral compass and shape the attitudes of those who believe in God.”

So while we cannot rely on Scripture to enact public policy per se, we can read the Bible — or other religious and humanist texts that grapple with the relationship between self and other, citizen and stranger, the fortunate and the less fortunate — as a means of awakening in us a heightened moral consciousness. We can hope that this exercise might inspire more humane discussion in the public sphere concerning the plight of migrants, and might lead to more just and equitable solutions at our borders.

This article originally appeared on Huffington Post.

Ananda Rose, a published poet and journalist, is author of Showdown in the Sonoran Desert: Religion, Law, and the Immigration Controversy. She recently received a doctorate in Religion and Society from Harvard Divinity School.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Who really deciphered the Egyptian Hieroglyphs?

The polymath Thomas Young (1773-1829) — physicist, physiologist, physician and polyglot, among several other things — became hooked on the scripts and languages of ancient Egypt in 1814, the year he began to decipher the Rosetta Stone. He continued to study the hieroglyphic and demotic scripts with variable intensity for the rest of his life, literally until his dying day. The challenge of being the first modern to read the writing of what appeared then to be the oldest civilization in the world — far older than the classical civilization of Young’s beloved Greeks — was irresistible to a man who was as equally gifted in languages, ancient and contemporary, as he was in science. He himself described his Egyptian obsession as being driven by “an attempt to unveil the mystery, in which Egyptian literature has been involved for nearly twenty centuries.” His epitaph in London’s Westminster Abbey states, accurately enough, that Young was the man who “first penetrated the obscurity which had veiled for ages the hieroglyphics of Egypt” — even if it was the linguist and archaeologist Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) who in the end would enjoy the glory of being the first actually to read the hieroglyphs in 1822-23.

From 1814 until the publication of his important Encyclopaedia Britannica article (‘Egypt’ in 1819), Young had had the field of hieroglyphic decipherment largely to himself. Champollion, though actively interested in the Rosetta Stone from 1808, did not tackle its decipherment in earnest until 1821. He quickly overtook Young and became the founder of Egyptology as a science.

During the 1820s, the two men sometimes cooperated with each other, but mostly they competed as rivals. Their relationship could never have been a harmonious one. Young claimed that Champollion had built his system of reading hieroglyphics on Young’s own discoveries and his tentative hieroglyphic ‘alphabet’, published in 1819. While paying generous and frequent tribute to Champollion’s unrivalled progress since then, Young wanted his early steps recognized. This Champollion was adamantly unwilling to concede, claiming that he had worked independently; and in his vehemence he determined to give all of Young’s work the minimum possible public recognition. Just weeks before Young’s death in May 1829, Champollion, writing in the midst of his 1828-29 expedition to ancient Egypt — he was then at Thebes in the Valley of the Kings — exulted privately to his brother in Paris: “So the poor Dr Young is incorrigible? Why stir up old matter that is already mummified? Thank M. Arago for the cudgels he has so valiantly taken up for the honour of the Franco-Pharaonic alphabet. The Briton can do as he pleases — it shall be ours: and all of old England will learn from young France to spell hieroglyphs by a totally different method.”

Such defiantly nationalistic overtones — at times evident in Young’s writings, too — have to some extent bedevilled honest discussion of Young and Champollion ever since those Napoleonic days of intense Franco-British political rivalry. Even Young’s loyal friend and admirer, the physicist Dominique Arago, turned against his work on hieroglyphics, at least partly because Champollion was an honoured fellow Frenchman.

Alongside this, Egyptologists, who are the people best placed to understand the intellectual nitty-gritty of the dispute, are naturally drawn to Champollion more than Young because he founded their subject. No scholar of ancient Egypt would wish to think ill of such a pioneer. Even John Ray, the Cambridge University Egyptologist who has done most in recent years to give Young his proper due, admits: “the suspicion may easily arise, and often has done, that any eulogy of Thomas Young must be intended as a denigration of Champollion. This would be shameful coming from an Egyptologist.”

Demotic script on a replica of the rosetta stone on display in Magdeburg. Photo by Chris 73. Creative Commons License. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Then there is the cult of genius to consider; many of us prefer to believe in the primacy of unaccountable moments of inspiration over the less glamorous virtues of step-by-step, rational teamwork. Champollion maintained that his breakthroughs in 1822-23 came almost exclusively out of his own mind, arising from his indubitably passionate devotion to ancient Egypt and his unrivalled knowledge of the Coptic language descended from ancient Egyptian. He pictured himself for the public in his writings as a ‘lone genius’ who solved the riddle of ancient Egypt’s writing single-handedly. The fact that Young was known primarily for his work in fields other than Egyptian studies, and that he published his studies on Egypt anonymously up to 1823, made Champollion’s solitary self-image easily believable for most people.

Lastly, in trying to assess the differing styles of Young and Champollion, there is no avoiding the fact that they were highly contrasting personalities and that this contrast sometimes influenced their research on the hieroglyphs. Champollion had tunnel vision (“fortunately for our subject,” says Ray); was prone to fits of euphoria and despair; and had personally led an uprising against the French king in Grenoble in 1821, for which he was put on trial. Young, apart from his polymathy and a total lack of engagement with party politics, was a man who “could not bear, in the most common conversation, the slightest degree of exaggeration, or even of colouring” (wrote his closest friend after Young’s death). Young and Champollion were poles apart intellectually, emotionally and politically.

Consider their respective attitudes to ancient Egypt. Young never went to Egypt and never wanted to go. In founding an Egyptian Society in London in 1817, to publish as many ancient inscriptions and manuscripts as possible so as to aid the decipherment, Young remarked that funds were needed “for employing some poor Italian or Maltese to scramble over Egypt in search of more.” Champollion, by contrast, had long dreamt of visiting Egypt and doing exactly what Young had depreciated, ever since he saw the hieroglyphs as a boy, and when he finally got there, he was able to pass for a native, given his swarthy complexion and his excellent command of Arabic. “I am Egypt’s captive — she is my be-all,” he thrilled from beside the Nile in 1828. Later he described entering the temple of Ramses the Great at Abu Simbel, which was blocked by millennia of sand: “I undressed almost completely, down to my Arab shirt and long linen underpants, and pushed myself flat on my stomach through the small opening in the doorway that, if cleared of sand, would be at least 25 feet in height. I thought I was entering the mouth of a furnace, and, when I had slid entirely into the temple, I found myself in an atmosphere heated to 52 degrees: we went through this astonishing excavation, Rosellini, Ricci, I and one of the Arabs holding a candle in his hand.”

Such a perilous adventure would probably not have appealed to Young, even in his careless youth as an accomplished horseman roughing it in the Highlands of Scotland. Unlike Champollion, Young’s motive for ‘cracking’ the Egyptian scripts was fundamentally philological and scientific, not aesthetic and cultural — in contrast with his attitude to the classical literature of Greece and Rome. Many Egyptologists, and humanities scholars in general, tend not to sympathize with this motive. They also know little about Young’s work in science and his renown as someone who initiated many new areas of enquiry (such as a theory of colour vision) and left others to develop them. As a result, some of them seriously misjudge Young. Not knowing of his fairness in recognizing other scientists’ contributions and his fanatical truthfulness in his own scientific work, they jump to the obvious conclusion that Young’s attitude to Champollion was chiefly one of envy. But not only would such an emotion have been out of character for Young, it would also not have made much sense, given his major scientific achievements and the fact that these were increasingly recognized from 1816 onwards — starting with French scientists, who awarded Young their highest honours.

For Champollion, the success of his decipherment was a matter of make or break as a scholar and as a man. For Young, his Egyptian research was essentially yet one more fascinating avenue of knowledge to explore for his own amusement. Both men were geniuses, though of exceptionally different kinds, and both deserve to be remembered in the story of the decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphs: Young for taking some difficult but crucial initial steps in 1814-19; and Champollion for discovering a coherent system in 1822-23, and thereafter demonstrating its validity with a vast array of virgin inscriptions.

Andrew Robinson is the author of the biographies Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion, and The Last Man Who Knew Everything: Thomas Young. . He has also written two Very Short Introductions for OUP: Writing and Script, published in 2009, and Genius, published in 2011.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe only history articles to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 14, 2012

Computers read so you don’t have to

Machines can grade essays just as well as human readers. According to the New York Times, a competition sponsored by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation produced software able to match human essay readers grade for grade, and a study of commercially-available automatic grading programs showed that computers assessed essays as accurately as human readers, but a whole lot faster, and cheaper, to boot. But that’s just the start: computers could lead to a reading-free future.

Not only are they cheap and efficient, computers grading essays do something human teachers can’t: they grade consistently. Because human readers disagree, the essay you grade B+ I might flunk, and someone else would give it a C-. Plus computers aren’t unionized, at least, not yet.

I have long been skeptical of machines grading essays. But now, in the face of incontrovertible scientific evidence, I think it’s time to welcome these newly-literate machines and find even more for them to do. After all, reading is a chore, which is why literacy scores on standardized tests are down (those tests are graded by machines, so we know they’re accurate).

The fact is that nobody reads books any more. Can you even find a bookstore on the rare occasion that you want one? So if machines can do our reading for us, like they do the laundry or the dishes, then we should celebrate this progress. We’re already using computers to check our spelling; some writers use them to check grammar as well. But give a computer a red pencil, and there may be no limit to what it can do.

Teachers can use computers not just to read student writing, but also to autorespond to student email: no, you can’t have an extension; yes, it’s on the final; I’m sorry about your goldfish. And not just student email. Let your computer tell the dean you’re not available at 10 on Thursday. Let it read the committee report for you and file it away. Let it read that book you agreed to review but could never find the time to read. It can do your professional reading. It can do your beach reading. So far as I know, computers are already generating book reviews on Amazon, the New York Times Book Review and TLS.

In fact, if the Hewlett data is correct, computers will soon replace human readers for just about all academic chores. A computer will read your dissertation and pass it, or suggest revisions. It will read your grant application and fund it, or suggest revisions. It will reject your manuscript. It will deny you tenure.

But computer readers are not just for academics. A well-programmed computer can take the drudgery out of all our daily reading tasks:

It can read your junk mail.

It can read your important mail.

When you’re at the movies it can read the subtitles and credits, get you the IMDb plot summary and list of continuity gaffes, and tell you whether you’ll miss something important if you go refill your popcorn.

It can read menus at restaurants and order for you based on your personal preferences or on Yelp reviews.

It can read signs, product labels, and assembly instructions both in English and Spanish, and tell you which parts should not be left over when you’re done (but it can’t read instructions that are all pictures and no words).

The literate computer can even read its own multi-screen terms of service, digital rights management, and end-user license agreements and click “Accept” for you so you can start using its reading services right away.

Plus a computer-reader can friend you on Facebook or follow you on Twitter, retweeting your posts or favoriting them. And since literate computers have a strong and consistent sense of what’s important in writing, they can also unfollow you, block you, or report you as spam. Computers, if they’re lazy, can even rely on other computers’ assessments: Deep Blue rates this essay 4.5 out of 5, so your computer will definitely want to read it.

Apparently, computer editors are replacing human editors in publishing as well. Given the annoying typos and spurious hyphens endemic to ebooks, I could save myself a lot of trouble by having my iPad read my iBook to itself. Then I can just go do something else while I wait for the movie version to appear in my Netflix queue.

But back to education. Writing teachers tell students, “Write for your audience.” But what if your audience is a machine? According to the latest scientific findings, that’s not a problem: computers and human readers agree with a statistical likelihood of P < 0.05. Fourteen years ago, at the dawn of the digital age, I saw the possibilities for computers replacing not just readers but writers as well:

Web sites now offer students the ability to download term papers free. If we’re going to eliminate the human reader, why not eliminate the writer too, and let the computer grading program interface directly with the computer-generated essay? In a way, they deserve each other. Besides, eliminating the drudgery of writing would allow students more free time that they could then spend with their newly-leisured instructors.

Now that I’m convinced about the value of computers reading writing, I’ve even developed a slogan for the computer reading machines to use: “We read, so you don’t have to.” Naturally, it will be up to a computer to decide whether that slogan is effective, though my roommate thinks it’s worth an A.

Computers: We read, so you don’t have to. The computer’s assessment? Nice work, Denny. Your essay shows mastery of 3 out of 5 skills. C+. But my roommate thought it was worth an A.

Dennis Baron is Professor of English and Linguistics at the University of Illinois. His book, A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution, looks at the evolution of communication technology, from pencils to pixels. You can view his previous OUPblog posts here or read more on his personal site, The Web of Language, where this article originally appeared. Until next time, keep up with Professor Baron on Twitter: @DrGrammar.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only dictionary, lexicography, language, etymology, and word articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Off with Their Heads! (Or not…)

Two hundred and twenty-three years ago today, the marquis de Launay looked out the window of the fortress of the Bastille and saw a large crowd of Parisians massing outside. Up until that moment, de Launay had possessed a rather cushy job, overseeing a “fortress” that, truth be told, probably held only six or seven prisoners, mostly lunatics and counterfeiters. The crowd expressed its intention to search the premises for gunpowder (to be used to defend the city from an imminent attack by royal forces which in fact never came), but de Launay refused them entry. He stalled for a while; he even invited representatives of the crowd inside the Bastille for refreshments, as he waited in vain for reinforcements. When the drawbridge suddenly opened (whether by design or by accident no one knows) and people streamed into the Bastille, they were fired upon by de Launay’s troops. The marquis was immediately suspected of having laid a trap. As he was being led toward the Hôtel de Ville for questioning, he was set upon, beaten, and stabbed. His head was severed from his body, placed on a pike, and paraded around the center of Paris. De Launay’s was not the only head paraded around that day and there would be more to follow.

The phrase “Off with their heads!” tends to be associated not only with the spontaneous violence of days like 14 July, but also with formal executions by guillotine, reflecting a widespread perception among historians and non-historians alike that Revolutionary crowds responded with great enthusiasm when the “enemies of the people” were guillotined before their eyes, and that they cheered and jeered as each aristocrat, counter-revolutionary, or traitor passed beneath “the avenging blade.” Perhaps even more perverse — at least from the vantage point of our modern sensibilities — were those women who supposedly sat at the base of the guillotine, knitting and wryly smiling as they counted the heads that dropped in front of them.

The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2682-320).

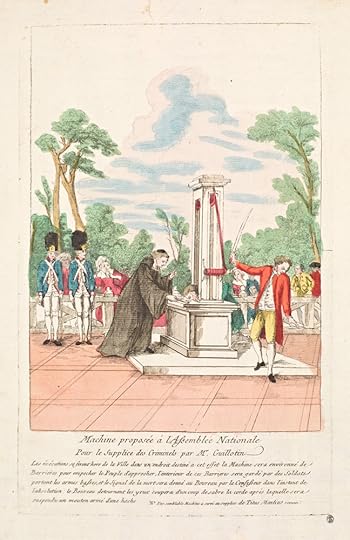

But do these images have any basis in fact?The guillotine has become so inextricably bound up with its unbridled use during the Terror, that it is easy to forget that it was initially conceived of as a great humanitarian innovation. No longer would executions be a spectacle of suffering, lasting for hours or even days. Dr. Guillotin, the legislator who first proposed the idea in 1789 (when no one imagined it would ever be used on anyone but criminals and murderers), reportedly promised that executions would take place “in the blink of an eye” and that victims would feel only “a slight cool breeze upon the neck.” France would be the first nation to accord criminals a “humane” death. In the image at left, produced before the machine was built and before it was known that the executioner would pull a cord rather than slice a rope, the executioner is portrayed as looking away at the final moment, exemplifying the ideal of death with discretion. (One can’t help wondering how this was supposed to work in actual practice.)

So, when the guillotine was first used on 25 April 1792, did spectators scream, “Off with their heads”? No, but they apparently did scream, or at least chant: “Give us back our wooden gallows!” Drawn in large numbers by the novelty of the machine, spectators were reportedly confused and disappointed by an execution that was over in a matter of seconds. Accustomed to the penal equivalent of a three act play, they felt cheated by a show that was over almost before it had begun. What was the point of attending a spectacle in which there was so little to see?

From a facsimile of the original in Hector Fleishchmann, La Guillotine en 1793 (Paris, 1908), 215.

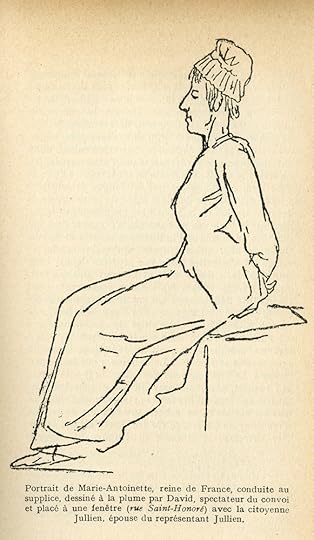

There is no denying that the guillotine enjoyed a brief heyday of popularity around 1792-93, and that some people went so far as to don guillotine earrings or put guillotine fruit slicers on their kitchen tables. There was undoubtedly a general fascination with the way the guillotine immediately transformed living enemies into lifeless heads, as if by magic. But this fascination never seemed to translate into enthusiasm and excitement at the spectacle of execution itself. It is certainly true that the executions of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette (as well as other notorious individuals such as Hébert, aka Père Duchesne, and Charlotte Corday) drew enormous crowds, probably numbering in the hundreds of thousands. But all credible first-hand accounts report that spectators simply shouted “Vive la République!” at the moment of death, followed by a kind of stunned silence. And those who truly wanted to get a good look at the victims knew better than to try to catch a glimpse of them in the few seconds between their descent from the cart and the moment of their death; instead, they gathered in the windows along the rue St. Honoré, where they could get a good long look as the condemned passed by in open carts. It was from one of these windows that the artist Jacques-Louis David drew his famous sketch of Marie-Antoinette on her way to the scaffold. As for the execution of more ordinary individuals, the most common reaction would seem to have been a kind of indifference. Particularly during the Great Terror of 1793-94, as executions became more frequent, most trustworthy accounts seem to suggest that Parisians grew weary of them.So where did we get the idea that spectators taunted victims, jeered at them or that they shouted rapturously as each head rolled? In part, we owe it to extremists on the left, who had a vested interest in making it appear that the public was wildly and enthusiastically behind the purging of their enemies. Mostly, though, we owe it to those on the right who were eager to portray Revolutionary crowds as having an insatiable lust for blood, denizens of a hellish world without decency or humanity. Many of the more colorful portraits were written long after the Revolution, contained in “memoirs” of dubious credibility. The following, rather lyrical description is from the supposed memoirs of the actor Fleury, published posthumously in 1836: “… [Radical] females, … shrews, had the work of surrounding the scaffolds, exciting people, and letting loose shrill cries during the spectacles. If they were old, they were called tricoteuses [knitting-women]; if they were young, they had the name furies of the guillotine. As for me, when I saw them assemble for the first time, the women and the men… it seemed to me that I was watching … uncoil a horrible legion of the damned, screaming, yelling, throwing their tangled hair into the wind, turning, ever turning…” Stories like this were picked up by Thomas Carlyle, and in turn by Charles Dickens, who in his Tale of Two Cities described women like Madame Defarge and her friend “The Vengeance” who sat in chairs directly in front of the scaffold, busily knitting while they methodically counted the heads that fell.

As for the phrase “Off with Their Heads!” that too would seem to have a provenance in British fiction rather than in the events of the French Revolution, owing its notoriety to Lewis Carroll’s Queen of Hearts in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Curiouser and Curiouser. Happy Bastille Day.

Paul Friedland is an affiliate of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard University, and currently a fellow at the Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies at Princeton University (2011-2012). He is the author of Seeing Justice Done: The Age of Spectacular Punishment in France, which explores the history of public executions in France from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Read his previous blog post: “The Last Public Execution in France.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 13, 2012

Titanic: One Family’s Story

At the time of the collision, Hanna Touma was standing in the doorway of the family’s cabin. She was talking to one of the other migrants from her village. It was just a jolt, but it made the door slam shut, cutting her index finger. Two of the men went to find out what had happened while Hanna went to the Infirmary to get her hand bandaged. Everyone she passed wondered what had caused the jolt and why the ship had stopped. The people looked worried, but Hanna could not understand what they said. The men returned and said the ship had struck an iceberg. They were told to stay in their cabins, to remain calm, and pray. The time was 11.40pm, the day Sunday, the date 14 April 1912.

It was four days earlier, on the evening of Wednesday 10 April, that the family had joined the ship at Cherbourg. They had been waiting in a hotel in the French port for six days. While the Titanic had been undergoing its sea trials, Hanna and the children had been travelling to Beirut, in the Lebanon, thousands of miles to the East. Hanna Youssef Razi was born in the tiny village of Tibnin on 10 April 1885 and her future husband Darwis Touma in 1870. They had got married in 1899. Hanna had been 14, Darwis 29. The couple had two children: Maria (born in October 1902) and Georges (born in February 1904).

Working in the onion fields, Darwis had saved a little money to pay for a passage to America. His brother Abraham had gone with him. They settled in the small town of Dowagiac, Michigan. Their plan, like that of most migrants, was to earn enough to send for their families to join them. Darwis had little success in this and seven years passed. He couldn’t save as he had been sending Hanna a little money from time to time. Abraham, on the other hand, had saved enough since he had no dependants to support. He sent his sister-in-law enough money for the trip, along with a piece of paper which said ‘Dowagiac, Michigan’. His intention was to surprise his brother.

Hanna treasured this piece of paper. Even though she had no idea where this place was, it was where her husband lived and that was where she was going. Hanna and the children travelled from Tibnin to Beirut by camel caravan. The days were long and exhausting, the nights short, and they did not have enough sleep or rest. The caravan company supplied the tents that they slept in and the food which they ate: yoghurt, cheese, and olives stuffed in pitta bread, spiced with onions and garlic. While this was a typical Arab meal, washed down with homemade wine, Hanna was a Christian. About a dozen other families accompanied the Touma family. Since the villagers brought their own musical instruments with them, the evenings were enjoyable. They had homemade flutes made from hollow pipes, and small hand drums covered with goat skins. Everyone, children and adults, danced in a circle with the men spinning their handkerchiefs high in the air.

When Hanna and the children reached Beirut, they left the camel caravan behind and took a freighter to Marseilles. On the voyage, the food was poor and the cabin cramped. It took five days. The migrants boarded a train in France and on the three-day journey to Cherbourg the children ran through all the carriages to see if there were any other children on the train besides the ones travelling with the villagers. Maria and Georges found that the other children spoke differently and they could not understand them, but they found ways to amuse themselves.

Half an hour after the collision, Hanna took Georges by the hand and headed for the top deck. She instructed Georges to stay put. She had to return for Maria, and the precious piece of paper that stated where her husband lived. She quickly helped Maria into her coat, grabbed her money and the slip of paper, and raced down the passageway that led out of Third Class. They climbed up from deck to deck, stopping only to grab three lifejackets, and they found Georges just where Hanna had left him. He related in tears how some of the people wanted to put him in a lifeboat, but he would not go without his mother.

When the Engelhardt C collapsible boat was lowered, the rowing started at once. The rowers then stopped, and the passengers could see the ship very clearly, badly down by the bow. It was freezing cold and the view was something Hanna would never forget. The enormity of the ship looked unreal, with hundreds of portholes all lit up and slowly being extinguished one by one. The cries of the people in the water soon stopped and it became very quiet. The sky was black with millions of stars all the way into the distance where the sky and waterline became one. It was so black you couldn’t see who else was in the lifeboat. They were all in a state of shock.

Although all the lights seemed to be on, suddenly they all went out and a loud explosion was heard. The tail end of the ship aimed straight up towards the stars. It stayed that way for several minutes. Then another slight noise was heard, it very slowly began to go lower, and then completely disappeared. Hanna covered Georges and Maria with her cloak so that they could not see. She cried for her fellow villagers: Fatima Mousselmani; the farm labourers Mustafa Nasr Alma, Raihed Razi, Amin Saad, Khalil Saad, and Assad Torfa; and Yousif Ahmed Wazli, a farmer.

Hanna and the other survivors were rescued by the Carpathia. Georges Touma was placed in a sack and pulled up on deck. After arriving in New York and having lost everything other than a few documents and mementos, St Vincent’s Hospital helped Hanna and the children. Meanwhile in Dowagiac, Abraham was shocked at the news of the disaster. How was he to tell his brother that his wife and children had been on the Titanic and now were gone? When he told Darwis, the two cried in sadness and rage, both devastated. Five days later, on Saturday 20 April, they received a telegram from a priest who spoke Arabic. He had a message for someone in Dowagiac that his wife and children had been saved. The little piece of paper had enabled Hanna to find her husband.

While the Touma family were reunited, Fatima Mousselmani was the only other survivor of the Tibnin villagers. The stories of the Titanic’s Third Class passengers are some of the most poignant. Unlike the Astors, the Guggenheims, the Thayers, and the Wideners, very little is known about their lives and it is only because of the Titanic that they have gained a place in history.

John Welshman is Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at Lancaster University. He is the author or editor of six books on twentieth-century British social history, including Churchill’s Children: The Evacuee Experience in Wartime Britain. He is also the author of Titanic: The Last Night of a Small Town (Oxford University Press, 2012). Read John Welshman’s previous posts: “One Voyage, Two Thousand Stories,” “Fellowes and the Titanic,” “Everyday people aboard the Titanic,” “Images from the Titanic Disaster” and “Tales of the Titanic Disaster,” and “Titanic Street.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Online editions in the classroom

Every year I teach a research seminar for English majors at Wellesley College. One of those seminars — “The Victorian Novel: Text and Context” — makes literary research its topic. For this course, the students choose one Victorian novel and that novel is the focus of the papers they produce on biography, transmission, editions, sources, and reception. I also pick a novel (by an author that no other student has picked) and we work together on research questions related to that novel.

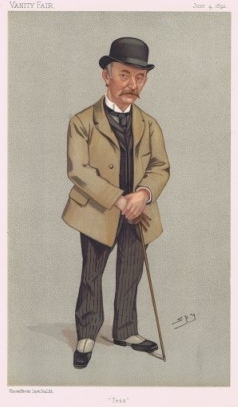

Caricature of Mr T Hardy by Leslie Ward in Vanity Fair, 1892. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

One year, for instance, I chose Tess of the D’Urbervilles because no one was researching Hardy. So far, so good — but, actually, it was difficult to do classroom research work. Juliet Grindle and Simon Gattrell’s Oxford World’s Classics edition (which I assigned) is first-rate (and uses the text established by the Clarendon, which they also edited), but it isn’t the Clarendon (nor was it meant to be). I could not copy the whole of the Clarendon Tess, nor could I ask them to purchase it (used copies, if you can find them, start at about $500). But doing classwork with the extensive textual material I imagined using was a struggle and often impossible. I’d copy particular pages of the Clarendon for a session, but inevitably a student would raise a question that would take us to some other part of the text. We were interested in the differences between the 1891, 1892, and 1912 editions, and though I had provided the pages on the infamous rape/seduction scene (the 1891 edition has Alec drugging Tess before the event), I hadn’t copied the description of Tess’s post-marital confession to Angel, which a student asked about. So we did the best we could with what we had. The questions they raised were the basic questions that undergraduates should raise as they start to learn how to do literary research. The process was all the more challenging without online resources.I was also committed to helping them make good use of Hardy’s Collected Letters and was bringing in copies of the letters to show them how to follow leads. Undergraduates don’t usually think about researching letters and instead simply rely on the quotations that other scholars call to their attention. That’s unfortunate. I aimed to teach them how helpful a good index is and how to follow leads that an editor’s notes might create (basic skills that good researchers have). But the task of bringing in the seven volumes of Hardy’s letters and then doing index work with them was, shall we say, awkward. What I needed was an online scholarly edition of the letters that I could use during class. I didn’t have that, so we accepted the limitations and we did the best we could with one set of the Hardy letters to share.

The course is also designed to teach undergraduates about editions. My experience is that when our students are deciding what edition to use (if such a choice is left up to them), the question they ask themselves is pretty straightforward: “Which is the cheapest?” Our classroom work involved discussing how the texts they chose had been edited. They brought the scholarly edition of their text to class, but it was often hard to do comparative work since each student had a different novel. If, during the session, a question arose that I knew might be addressed by having the whole class look at a particular section of the text (“Did Dickens’s punctuation change over the course of his career? Can we compare sample pages from Oliver Twist and Great Expectations?”), I knew that we couldn’t really look at the pages together. It was hard enough to figure out how to share the library resources that they all wanted to use at the same time.

At this point, readers of this blog entry can tell where I’m headed. Let’s just say that I am eager to have scholarly editions of texts online. As I imagine into a future with these online texts, I am rethinking what will be possible in and out of class. At the most basic level all my students will be able to access the same edition at the same time without needing to purchase personal copies or negotiate inter-library loans. Comparisons with antecedent or contemporary literature will be much easier, as will the opportunities to introduce material from letters or other sources (where available). With scholarly editions of texts online, students will hone their research skills by getting into the habit of following ideas in the secondary literature will find new ways to explore old texts.

Lisa Rodensky is the Barbara Morris Caspersen Associate Professor in the Humanities, Wellesley College and member of the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online editorial board. She has many research interests related to the Victorian period, and specifically the Victorian novel. Her publications include The Crime in Mind: Criminal Responsibility and the Victorian Novel (2003), and Decadent Poetry from Wilde to Naidu (edited volume, 2006). She is the editor of The Oxford Handbook of the Victorian Novel and is also preparing a monograph that investigates the relation between the novel and reviews.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online is coming soon. To discover more about it, view this series of videos about the launch of the project.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

What is the probability that you are dreaming right now?

Reality: A Very Short Introduction

By Jan Westerhoff

Most people think that even though it is possible that they are dreaming right now, the probability of this is very small, perhaps as small as winning the lottery or being struck by lightning. In fact the probability is quite high. Let’s do the maths.

Assume your life is made up of a finite number of moments of consciousness (we’ll call these mocs). For the sake of simplicity let there be one moc per second. If we get a healthy amount of eight hours of sleep every night we are left with sixteen hours = 57600 mocs that constitute our waking time. Every night we are asleep for 2880 seconds. We know that 20 to 25 percent of our sleep consists of REM sleep, the kind of sleep during which dreaming takes place. Assuming the lower figure of 20 percent this leaves us with 5760 mocs while we are dreaming. So one out of every ten mocs happens during a dream; the odds that your current moc is one of them is one in ten.

But is it reasonable to assume that there are moments of consciousness outside of the waking state? Norman Malcolm argued in 1956 that this was logically impossible, claiming that “if a person is in any state of consciousness it logically follows that he is not sound asleep.” But whether there is consciousness in dreams appears to depend entirely on what we take consciousness to be. We can hardly claim that a consensus on this has been reached, but if we understand consciousness in accordance with the contemporary discussion as something that can come in different strengths and constitutes at the very least an appearance of a world then dreams do constitute some form for consciousness, since in a dream some form of a world appears to us.

But even if dreams are conscious experiences we might think the above argument is a bit too quick. As experience confirms, one hour of carrying out a habitual boring task does not equal 3600 moments of consciousness; our consciousness might be elsewhere for most of the time. Moreover, time in dreams might not obey the rules of the waking world, a dream-second may correspond to fewer or more mocs than a waking-second. This is true, but if we spend more of our waking life unconscious the ratio of waking mocs to dreaming mocs increases. It becomes even more likely that your present moment of consciousness happens during a dream.

But even if dreams are conscious experiences we might think the above argument is a bit too quick. As experience confirms, one hour of carrying out a habitual boring task does not equal 3600 moments of consciousness; our consciousness might be elsewhere for most of the time. Moreover, time in dreams might not obey the rules of the waking world, a dream-second may correspond to fewer or more mocs than a waking-second. This is true, but if we spend more of our waking life unconscious the ratio of waking mocs to dreaming mocs increases. It becomes even more likely that your present moment of consciousness happens during a dream.

How dream-time relates to waking-time is indeed a difficult question. Sequences of events that take days can flash by in an hour’s dream; when you are dreaming, a lot can happen in a short time. Nevertheless we should note that as far as we can empirically determine the relation between dream-time and waking-time the two seem to be running at the same speed. Sleep researchers came up with a very clever way of testing this. Since the movement of our eyes is the only bodily action we can control during dreaming, experiments could be carried out with lucid dreamers asked to signal the beginning and end of an estimated time period by moving their eyes. These signals could then be tracked in a sleep laboratory. The average length of an estimated ten-second interval of dream-time was thirteen seconds of waking time, which is the same as the average length of an estimated ten-second interval of waking time. If this fact about lucid dreams can be generalized it seems to be the case that there is the same amount of moments of consciousness per unit of time during the waking state as there is in a dream.

Now a ten percent likelihood appears quite high. We usually regard the possibility that we are dreaming right now as something that is logically possible, but highly unlikely, i.e. as an event with probability of significantly less than 0.1 percent. Of course none of the above claims that we can never be more than 90 percent certain that we are presently not dreaming. We could, for example, employ some sort of reality-testing techniques to find out whether we are really dreaming. (Two techniques recommended by sleep researchers involve trying to jump into the air to check whether we stay airborne any longer than usual, and looking at a piece of printed text twice to see whether the letters have changed.) But it is not quite clear how the outcomes of these experiments should influence our credence. It is possible that they deliver a negative outcome (we fall to the ground immediately, the text stays constant) but we are still dreaming. Moreover, the very fact that we feel the need to carry out a reality-test may be a strong indication that we are dreaming. Philosophy tutorials aside, when we are awake we rarely wonder whether we are really awake.

Jan Westerhoff is Reader in Philosophy at the University of Durham and Research Associate at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. His research mainly concentrates on problems of metaphysics, both in the Western and in the Indo-Tibetan tradition. He is the author of the recently published Reality: A Very Short Introduction.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 12, 2012

Friday 13 July: Unlucky for some Conservative ministers

On Friday, 13 July 1962, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan sacked a third of his Cabinet. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Lord Chancellor, the Ministers of Education, Defence, Housing and Local Government, and the Ministers for Scotland and without Portfolio all lost their jobs in an episode that became known as the ‘Night of the Long Knives’. This dramatic phrase, most frequently used to describe Hitler’s bloody purge at the end of June 1934 of the leadership of the Sturmabteilung (his paramilitary Brownshirts), has since become political shorthand for any ruthless political manoeuvres and unexpectedly brutal reshuffles. Macmillan’s ministerial victims in July 1962 certainly considered his actions both ruthless and brutal. As the Liberal MP, Jeremy Thorpe, memorably put it: “Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life.”

During 1962 Macmillan had become increasingly frustrated by what he saw as the inability of his colleagues (particularly the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Selwyn Lloyd) to embrace the strategies he considered essential to restore the government’s fortunes at a time when both the economic and industrial outlook in Britain was troubled. The Conservative government, in power since 1955 under Eden and then Macmillan, was doing badly in the polls and in the spring of 1962 had some disastrous by-election results. The Party was divided on issues such as Britain’s application to the Common Market and the future of Northern Rhodesia. Ministers squabbled between themselves over defence and the economy. The Chancellor’s spring Budget — increasing taxes on sweets, soft drinks and ice cream and so denounced as a ‘kiddy tax’ — was a public relations disaster. But in the view of Lloyd and others, Macmillan’s proposals for a new approach based on an incomes policy went against the principles of prudent economy and Conservatism itself. Something had to give.

On the overseas front, things looked grim too. Relations with the United States were strained over nuclear policy and other issues. There were tensions with the Commonwealth about Britain’s application to the EEC, while negotiations with Brussels were deadlocked and De Gaulle working up to his first veto. In Laos, a renewed outbreak of civil war raised the spectre of Western intervention and the Central African Federation was breaking up. East-West tension, to reach its apogee a few months later in the Cuban missile crisis, was running high. As Macmillan later commented, while he accepted in principle Cowper’s line that “Variety is the spice of life,” he “sometimes felt that the flavouring could be a little overdone.”

Encouraged by his Home Secretary and long-standing rival, R.A. (Rab) Butler, the Prime Minister decided that the Chancellor of the Exchequer must go. But how did a change at the Treasury turn into a ministerial massacre? After the event, Macmillan claimed he was rushed into the sackings on 13 July by a mixture of political conspiracies against him and press speculation. The precise timing of his move certainly owed much to the stories that appeared in the press on 12 and 13 July, fuelled by Butler’s remarks to press baron Lord Rothermere at lunch on the 11th. But it is clear that the Prime Minister had had a major reshuffle in mind for some time. Indeed, as he complained afterwards when lambasted by the media, he had been urged by the press to sack ineffective ministers, then criticized for doing so. Macmillan, a very old and wily political hand, was not overly surprised at this contradiction. Meanwhile, he noted in his diary that there were “altogether 10 new faced in the administration” and a “sense of freshness and interest” in Cabinet.

It has often been said that Macmillan did most harm to his own reputation by the Night of the Long Knives, but there is surely an element of hindsight here. Things certainly got worse for his government at home and abroad; he was unable to carry through many of the policy changes he sought; and he was to resign as Prime Minister in October 1963, succeeded by Sir Alec Douglas-Home. In his memoirs, published in 1973, Macmillan claimed he had made a ‘serious error’ in July 1962 in combining the sacking of the Chancellor — which was inevitable — with a general reconstruction of his government. At the time, however, the evidence suggests he knew exactly what he was doing. Certainly he regretted it, in that he hated the personal element of the purge; telling old friends and colleagues they no longer had a job was undoubtedly painful. But in political terms he (and Butler, whose role in the episode is hardly benign) had been clear it was both necessary and desirable, even if events prevented the purgative from having the full effect he intended.

“At a time like this,” Macmillan had written in his diary on 18 June 1962, “we should follow Danton’s famous words” in his address to the revolutionary French Legislative Assembly in 1792: “Il faut de l’audace, encore de l’audace, toujours de l’audace.” And despite Macmillan’s famously languid patrician style, he was a politician who did not lack boldness when he thought it necessary. “Great national troubles, even disasters,” he wrote, “can be faced with calm and equanimity by Ministers of courage.” 13 July 1962 may not be an anniversary that the Conservative Party can look back on with pride, but nor is it correct to see it, as Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell did, merely as “the act of a desperate man in a desperate situation.” The execution was certainly clumsy, but Macmillan wasn’t the only one who thought the blow should fall. As Rab Butler told Press Secretary Harold Evans, “I do understand the Prime Minister’s motives and I am behind him…. But it wasn’t done properly.”

Macmillan’s actions on 13 July 1962 were the equivalent of putting his ministerial Scrabble letters back into the bag in the hope of getting a more useful set. In Macmillan’s view, drastic action was clearly needed to reverse the downward trend. But his colleagues had responded negatively to his proposals for a new approach and reform of the labour market. They did not share his feeling, as he later expressed in his memoirs, “that we were moving into a new situation where, as in the Einstein world, cause and effect seemed to follow different rules.” (An American journalist, visiting Britain in June 1962, put it more prosaically: Conservatives, he said, “don’t really smile.”) In that case, Macmillan seems to have decided, they should be given something to cry about.

Gill Bennett, MA, OBE was Chief Historian of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office from 1995-2005 and Senior Editor of the UK’s official history of British foreign policy, Documents on British Policy Overseas. She is the author of the upcoming book Six Moments of Crisis: Inside British Foreign Policy. As a historian working in government for over thirty years, she offered historical advice to twelve Foreign Secretaries under six Prime Ministers. A specialist in the history of secret intelligence, she was part of the research team working on the official history of the Secret Intelligence Service, written by Professor Keith Jeffery and published in 2010. She is now involved in a range of research, writing and training projects for various government departments.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles about British history on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Beyond Conventional Transitional Justice

After former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak was toppled in February 2011, the Supreme Council for the Armed Forces assumed executive power in Egypt, and launched the ‘transitional period.’ In the seemingly boundless space created by Mubarak’s absence, millions of citizens freely debated every aspect of the emerging political and social order, in public meetings, at home, in the media, and on the streets. It was a time of limitless imagination. Meanwhile, amongst international and Egyptian human rights organisations, a more contained conversation began on the practice and precedents of transitional justice.

Celebrations in Tahrir Square after Omar Soliman's statement that concerns Mubarak's resignation. February 11, 2011 at 10:15 p.m. Photo by Jonathan Rashad. Creative Commons License.

Cairo soon played host to major conferences on the subject. In these meetings, three central assumptions were regularly made, particularly by international participants. First, transitional justice precedents offer the necessary prescriptions for Egypt at this time. Second, the Egyptian people are unaware of this and need educating accordingly. Third, and underpinning the rest, the most deceptively straightforward premise: Egypt’s transition is underway. But as the conference proceedings showed and events since have confirmed, these premises should actually have been posed as questions.

Do international transitional justice precedents suit the Egyptian case?

In 2011, Egyptian demonstrators proclaimed revolution and not reform. The slogan they borrowed from their Tunisian forerunners was ‘The People Want the Fall of the Regime,’ where the Arabic word for ‘regime,’ al-nizam, also connotes ‘order’ or ‘system.’ By contrast, transitional justice offers mechanisms for a more conservative conception of transition, confined within the realms of criminal law and political reform. Several studies have reflected on the limits of this standardisation.

Two neglected areas resonate particularly in Egypt. First, as with the US occupation in Iraq, and NATO in Kosovo, transitional justice practice rarely highlights the accountability of external actors. American and European governments are often held up as ideal-types, while developing state actors are scrutinised, reinforcing existing imbalances of power. The Mubarak regime’s collaboration with London and Washington — not least on extraordinary rendition — is a case in point. Significantly, an American National Lawyers Guild delegation recently visited Egypt to document the role of US government and corporations in human rights abuses.

Another neglected question concerns the kind of injustice being righted. In Egypt, violations in the field of social and economic rights abound. Accepting his first IMF package in 1991, Mubarak had established a neoliberal order which flouted several international economic rights conventions on unionisation, child labour, gendered wage discrimination, and migrant labour. And yet, in transitional justice practice, critiques of crony capitalist interests as culpable are rare.

Do Egyptians need an education in transitional justice?

If the Mubarak regime’s violations outstrip conventional transitional justice provisions, then the assumption that Egyptian society needs an education in it appears flawed. Certainly, knowledge of international precedents only enriches public debate. Yet Egyptians’ intimate understanding of the crimes committed by the Mubarak regime, and of potential remedies, was made clear in the slogans and demands of the revolution’s opening 18 days. Protests were called against ‘Torture, Corruption, Poverty, and Unemployment’ on Police Day, and the chant ‘Bread, Freedom, Human Dignity,’ popularised. As rights activist Hossam Bahgat recalled, by condemning the authorities’ violation of political, civic, social, and economic rights together, Egyptians had ‘completely surpassed’ the artificial sequencing of rights debate.

Protesters’ earliest demands were for the trials of old regime members, overhaul of state institutions, and reparations for victims of state violence. They displayed a clear preference for retributive justice — al-qasas — over the non-judicial prescriptions of some international practitioners, such as truth and reconciliation commissions. But beyond these transitional justice-related themes, they also demanded representative government, autonomy from Washington in policymaking, and social justice. Civil society campaigns targeted military trials, state media, odious debt, stolen public funds, and injustice in the workplace. These millions of Egyptians envisioned fundamental socio-political change.

Is Egypt really ‘in transition’?

Clearly, then, there are differences in scope between reformist and revolutionary conceptions of transition. Yet the paradox that Egyptians are experiencing today is the sheer ephemerality of that transition. In most successful transitional justice cases, one common condition is the existence of the political will to propel the process. In Egypt, the military council simply lacks that political will, and has presided over a year and counting of military trials for civilians, repression of demonstrations, and media censorship.

As of their constitutional declaration in March 2011, the generals enjoyed full executive powers. Citizens have been disappointed at the outcomes of former regime members’ trials, and the lack of vetting, whether in Egypt’s police apparatus, prison system, or official media. Meanwhile, recently negotiated IMF packages carefully preserve the neoliberal status quo.

During the presidential elections in June 2012, the generals issued yet another constitutional declaration, which stripped the presidency of many of its powers. The elections themselves were invalidated in the eyes of many by the candidacies of two former regime members, and the lack of oversight regarding campaign funds and tactics. In this context, the victory of Muslim Brother Muhammad Mursi left both his powers and allegiances very much in question, particularly due to the Brotherhood’s silence during and perceived complicity in the military council’s repression.

Today, Egypt’s transition is at best suspended, and over the past months, transitional justice mechanisms like trials and reparations have been selectively developed by a state elite that is untransformed. Hence the activists’ mantra, ‘the revolution continues’ (al-thawra mustamira), and the continued protests against the ‘remnants’ (fulul) of the Mubarak regime.

Looking Forward

However well-intentioned their efforts then, a warning note must be sounded to those interested in transitional justice in Egypt today. Pushing this agenda when its principal precondition, political will, is absent risks legitimising a ‘transitional’ order little different from the old. Consequently, most Egyptian activists have maintained that the transition has yet to come, and have advised international colleagues not to engage the military council.

This situation has only been exacerbated by the election of Mursi, which should have signalled the end of the transition, but which has not been received as such, due to the flawed electoral process, and the military council’s ongoing domination of executive powers in Egypt. A case in point came with Mursi’s decree to reconvene parliament on Sunday – it had been dominated by members of his own organisation, and dissolved with the approval of the military council in June 2012. By Monday, the military council had shot down Mursi’s decision and issued the president a warning. Meanwhile, political and legal activists urged him to use his position to free those in military prisons since 2011, that is, to begin what might resemble a transitional justice process earnestly.

The Egyptian revolution’s demands, however contested, transcended the bounds of reformist transitional justice practice. Egyptian rights activists have resourcefully incorporated transitional justice principles into their campaigns, while aiming at more far-reaching goals and showing their international colleagues how to support them. Indeed, the revolution is further proof that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ remedy for transitional justice: it is preferable to promote ‘local’ formulae in light of global experience, rather than vice versa. Today, as varying levels of mobilization recall Mubarak’s last years in power, the call for transitional justice may have to become a strategy for political pressure in Egypt, before it can become a process for genuine change.

Reem Abou-El-Fadl is Jarvis Doctorow Junior Research Fellow in International Relations and Conflict Resolution in the Middle East at St Edmund Hall and the Department of Politics and International Relations, Oxford University. She is the author of “Beyond Conventional Transitional Justice: Egypt’s 2011 Revolution and the Absence of Political Will” in the International Journal of Transitional Justice, which is free to read for a limited time. Her research interests include Egyptian, Turkish and Palestinian political history, and the foreign policymaking of developing states. Her most recent publications examine Anti-Zionism and Palestine in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution and Arab perceptions of contemporary Turkish foreign policy. Her current research examines Egyptian support for the Palestinian cause in the 1960s and 1970s.

The International Journal of Transitional Justice publishes high quality, refereed articles in the rapidly growing field of transitional justice; that is the study of those strategies employed by states and international institutions to deal with a legacy of human rights abuses and to effect social reconstruction in the wake of widespread violence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers