Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1037

August 1, 2012

Two English apr-words, part 1: ‘April’

The history of the names of the months is an intriguing topic. Most of Europe adopted the Roman names and some of them are trivial: September (seventh), October (eighth), November (ninth), and December (tenth). (Though one would wish the numerals to have reached twelve.) But there is nothing trivial in the division of the year into twelve segments and the world shows great ingenuity assigning names to them.

The Romans dedicated most of their months to the gods and one doesn’t need a dictionary to guess who was honored in January or March. (We still have janitors and plenty of martial arts.) February and May are less transparent to modern speakers, but the principle behind naming them was the same. Before the Anglo-Saxons adopted the names still in use, they had their own system. King Alfred’s calendar looked so:

Geola se æftera “later Yule” (æ has the value of Modern Engl. a in at)

sol-monað, approximately “mud month” (that is, if sol had a short vowel; sol with a long vowel meant “sun,” but the name of a winter month was unlikely to contain reference to the sun; Old Engl. ð and þ designated the sounds we hear in Modern Engl. thy and thigh respectively, but for simplicity’s sake I will use only ð here)

hreð-monað (several doubtful interpretations: glorious month?)

Easter-monað “Easter month” (Easter is a pre-Christian word; people may have believed in a goddess called Eostre, but the evidence is scanty)

ðrimilce (monað) (a month in which cows can be milked three times)

liða se ærra (liða meant “month,” apparently, related to liðe “mild”; the term was more specific than monað, and the whole meant “the earlier liða”)

liða se æfterra “the later liða,” “the liða after”

weod-monað “grass month” (weod has yielded Modern Engl. “weed”)

hærfest-monað “harvest month”

winterfylleð (fylleð from fyllan “to fell”?)

blot-monað “sacrificial month”

ærra geola “earlier Yule”

Other Germanic speaking peoples had their own names of the months, some of which defy interpretation. For instance, German Hornung “February” has been the object of much clever guessing. Even when the year is divided into twelve segments, the beginning and end of each month doesn’t necessarily coincide with our first and last day. For example, in Iceland, one of the traditional months lasted from the middle of Europe’s January to the middle of February, and the next from the middle of February to the middle of March. Now Iceland has the same system as the rest of the Western world and the old words are being remembered less and less. Capricious dictators liked changing the names of the months. Among the Roman names, July and August stand out as not being dedicated to any god. And indeed, Latin Julius replaced quin(c)tilius after Caius Julius Cæsar’s death and apotheosis. Obviously, it would have been tactless not to honor his illustrious successor in a similar way, so the sixtilis of Republican Rome was named after Emperor Augustus. At the height of the French Revolution, all the months were renamed. Of those, most people (at least outside France) will easily recall only Germinal (from March 21 to April 19, a month of “germination”), thanks to the title of Émile Zola’s famous novel or the film(s) based on it.

A marked man by F. M. Howarth. Source: NYPL.

Of all our names of the months, April has the most convoluted history. The Romans called it Aprilis mensis, and it seems natural to suppose that in the adjective Aprilis the name of some deity is hidden, but none of the Roman gods or goddesses provides a good match. Aphrodite has been suggested as a possible candidate. Although the match is far from perfect, we will return to it below. Other suggestions have also been made.

In Ancient Rome, April was the second month of a year and the calendar made some use of ordinal numerals before the word mensis. (Compare quintilis (July) and sextilis (August), mentioned above.) Such colorless names devoid of religious connotations were easy to replace with new ones. Hence the idea that originally the first syllable of Aprilis was ab “from,” a prefix and a preposition with ties in and outside Germanic (of is one of its cognates, as is its late doublet off) and present in numerous English borrowings from Latin and Old French, such as abdicate, abduct, abscond, absolve, and the rest. The Latins allegedly forgot the meaning of aprilis, whereupon folk etymology connected it with aperire “opening” (compare Engl. aperture) and took it for a contraction of aperilis (unrecorded). We will return to ap- next week in connection with another apr-English word. (Can you guess it? Not much to choose from. If you cannot, stay in unbearable suspense.)

Skeat probably found the aprire etymology plausible. In any case, he wrote that April is said to be so named because the earth then opens to produce new fruit. “Is said” served him as a safeguard, but since he mentioned this idea, he could not look on it as totally indefensible. Medieval German had the noun æber “snow-free place,” related to Latin apricum “sunny,” a tolerably good sense to associate with April. But if at any time the word in question began with ab, what did the rest of it mean? What is ril-?

The Century Dictionary usually followed Skeat. However, in this case it added the necessary qualification: “…usually but, fancifully, regarded as if… from aperire, the month when the earth ‘opens’ to produce new fruits.” (The emphasis is of course mine; note fruits for Skeat’s fruit.) The English word was first borrowed from Latin and later reborrowed from Anglo-French (hence the Middle English variants with v: averil, averel, and others). The Modern French for April is avril, but the Modern English form was made to look like its distant Latin source.

When a Latin word defies all attempts at explaining its origin, it is customary to resort to Etruscan. Unlike the pre-Germanic substrate about which something was said in the post on herring, the Etruscan language has not been completely lost. Several hundred Etruscan words, including a few divine names (theonyms, as they are called in special works), have come down to us and their meaning has been ascertained with a fair degree of confidence. One of such words is allegedly apru, from Greek Aphro- “Aphrodite.” Referring to Apru is the only way to etymologize April as “the month of Venus” (Venus being the Roman counterpart of the Greek goddess). This hypothesis takes a good deal for granted. No other month of the Roman calendar owes its name to Etruscan. So why just April? If at the time of presumed borrowing the Latins understood the meaning of apru (Apru), why didn’t they replace it with Venus? All things considered, the Etruscan origin of April is hardly more convincing than the others we have examined here. None of the tentative suggestions discussed above looks pervasive. The Romans had no clearer idea of the etymology that interests us than we do (a small comfort).

I’ll finish by adding insult to injury. The origin of All Fools’ Day is unknown too and there are as many conjectures about it as about the etymology of April. But it isn’t fortuitous that the festival is held at the vernal equinox, when “the earth opens to receive new fruit(s)” and the world rejoices. This is the time for carnivals, tomfoolery, and relaxation. So let us not take our etymological ignorance too seriously. What else could be expected of the name of such a month?

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Moby Dick Lives!

Moby-Dick is alive and doing quite well. It serves as inspiration for cultural creation of all sorts. As much an adventure story as a metaphysical drama, the novel raises questions about the nature and existence of God, about the quest for knowledge, about madness and desire, about authority and submission, and much more. Its style, at once bold and impassioned, erratic and windy, somehow still manages to entrance and inspire readers a century and a half after its publication. It is, as critic Greil Marcus remarks, “the sea we swim in.”

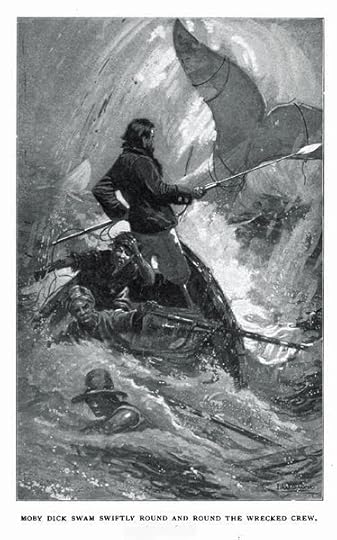

Illustration of the final chase of Moby-Dick by I. W. Taber, 1902. Charles Scribner's Sons.

After a less than enthusiastic reception in 1851, the novel and its author drifted out of sight, except for pockets of aesthetes in the United States and England. By the turn of the century, the novel was being rediscovered and by the 1920s it had become a full-blown American success story. In the 1930s it entered into the canon of American literature — the yardstick from which novelists as varied as Norman Mailer, Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, Charles Johnson, Cormac McCarthy, Chad Harbach, and China Miéville have begged, borrowed, and stolen as a means of equaling its sweep. Poets as varied as Hart Crane, Charles Olson, and Beachy-Quick have waded into its oceans of possibility.Don’t, however, confine the influence of the novel and its characters — a mysterious White Whale, a maniacal captain Ahab, a loquacious shipmate Ishmael, and his friend, the harpooner and divine savage Queequeg — only to the realm of literature. Moby-Dick has been, and continues to be, inspirational for film, art, and as an enduring source for metaphors and comedy routines. It has become as much a part of American popular culture as hamburger and Walt Disney productions.

The first motion picture version of Moby-Dick in 1926 was a silent, starring Lionel Barrymore. Forget about the whale vanquishing Ahab. In this film, Ahab — although he is dismasted — gets both the girl and the whale. Many other renditions of the novel in film followed. Perhaps the most famous was directed by John Huston, co-written by Huston and Ray Bradbury, and starring Gregory Peck as Ahab. Although Peck hardly sizzled with Ahab’s philosophical gravitas, the film did challenge polite 1950s codes about racial relations and hinted at blasphemy. A more recent film version, 2010: Moby Dick may strike Moby Dickians as blasphemous in its own manner. Renee O’Connor (once Gabrielle on the hit television show Xena: Warrior Princess) plays a scientist who is the only one that lives to tell the tale of a massive white whale, capable of flight, that once ripped a submarine in half and caused a Navy officer to lose his leg!

Almost no American artist of note — from Jackson Pollock to Rockwell Kent, Mark Bradford to Red Grooms — has failed to rise to Melville’s challenge that the White Whale shall remain “unpainted to the last.” Two years ago, an amateur artist of talent named Matt Kish, completed a project inspired by the book. Each day, on a piece of found paper, he made a drawing based on a single page from his Signet edition, for a total of 552 drawings! In addition to artists, composers and songwriters as varied as Laurie Anderson, Bob Dylan, Bernard Hermann, Jake Heggie, and rapper MC Lars have danced to its rhythms. Can we forget Dylan’s Captain Arab who alights upon the shores of America in surrealistic fashion?

"Blue (Moby Dick)" by Jackson Pollock, 1943. Ohara Museum of Art. Source: Wikipaintings.org

Abbott and Costello had a comedy routine featuring the White Whale, certain that its popularity was deeply ingrained in the American popular imagination. Says Costello to Abbott, at one point in their repartee, “It’s a spout time you keep your mouth shut.” Phyllis Diller referred to her obese mother-in-law as ‘Moby Dick.’ Since 1942, youngsters have gained entry into the marvels of the tale via Classics Illustrated Comics, as well as commix versions, one of which was drawn by Sam Eisner. Sam Ito has made a marvelous Pop Up version of Moby-Dick, with moving parts.

The novel offers an endless stream of metaphors and meanings. Imprisoned members of the Baader-Meinhoff terrorist group used the names of characters to mask their identities. Political strategist Karl Rove once complained that a bunch of Ahab-like democrats pursued George W. Bush as if he were the White Whale, and Edward Said in the wake of 9/11 warned Americans away from seeking vengeance as Ahab had against the Moby Dick.

Gay critics and artists have long been drawn to Moby-Dick for the homoerotic relationship between Ishmael and Queequeg, and how Melville (who was probably bisexual) was willing in this novel to break with literary expectations to dive deeper into his talent and soul. Forget about the dearth of women characters in the novel. Sena Jeter Naslund created a story about an adventurous young woman that was Ahab’s wife, while Christian author Louise M. Gouge, in three volumes, not only imagines Ahab’s wife, but has his son fall into a state of sin, save the life of Starbuck’s son, lose his leg, and then be redeemed.

Where Moby-Dick will be in 100 years is impossible to predict. But its evolution indicates that what we today find meaningful may someday be seen as peripheral. In the early twentieth-century, Ishmael was often shunned as a problematic narrator and uninteresting character. A Knopf 1926 abridged version of the novel deleted what is now often considered the most resonant, or at least recognizable, first sentence in literature: “Call Me Ishmael.” That line, that clarion call into a novel of adventure, is now so embedded in our culture that cartoonists have employed it as a pick-up line used by guys in a bar, or shown Melville at writing desk, struggling to start his novel. Strewn around him are discarded pieces of paper with the words, “Call Me Larry,” or “Call Me Al.”

Moby-Dick lives, as Nathaniel Philbrick has noted in Why Read Moby-Dick, because it captures the American “genetic code” of concerns and conceits. It also contains so many elements of a great novel; one could mine its pages for years without exhausting its meanings. Finally, the novel endures because it lives fully in all the nooks and crevices of American popular culture.

There is no indication of that changing anytime in the near future.

George Cotkin is Professor of History at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, and author of the forthcoming book, Dive Deeper: Journeys with Moby-Dick.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Seduction by contract: do we understand the documents we sign?

We are all consumers. As consumers we routinely enter into contracts with providers of goods and services — from credit cards, mortgages, cell phones, cable TV, and internet services to household appliances, theater and sports events, health clubs, magazine subscriptions, and more.

But do we understand the contracts that we sign? Do we really know how much we will end up paying for the privilege of using a cellphone or a credit card? Many consumer contracts feature complex, multidimensional pricing schemes. Think of the common cellular service contract with its three-part tariff pricing—a fixed monthly fee, a number of included minutes, and an overage fee for minutes used beyond the plan limit—further complicated by distinctions between peak minutes, night and weekend minutes, in-network and out-of-network minutes, minutes used to call a pre-set list of “friends,” and minutes used to call everyone else. Then add the equally complex pricing structures for messaging and data services. With such complex pricing, how many consumers can accurately anticipate their annual wireless bill?

Beyond complexity, sellers and service providers often backload costs onto long-term price dimensions that are underestimated by consumers. Think of low “teaser” interest rates on credit cards, which then reset to much higher rates at the end of the introductory period. Or think of the many cell phones that are given away for free, so long as the consumer signs a two-year service contract. Why do consumer contracts bestow short-term perks and then hit us with long-term costs?

The design of consumer contracts, and specifically the common complexity and deferred-cost features, can be explained as the result of the interaction between market forces and consumer psychology. We consumers are imperfectly rational, our decisions and choices influenced by bias and misperception. Moreover, the mistakes we make are systematic and predictable. Sellers respond to those mistakes. They design products, contracts and pricing schemes to maximize not the true (net) benefit from their product, but the (net) benefit as perceived by the imperfectly rational consumer. The result: a behavioral market failure.

The interaction between market forces and consumer psychology explains many of the complex design features so common in consumer contracts. The temporal ordering of costs and benefits — with benefits accelerated and costs deferred — is linked to consumer myopia and optimism. Complexity responds to bounded rationality, to the challenge of remembering and then aggregating multiple dimensions of costs and benefits. These two features — complexity and cost-deferral — serve one ultimate purpose: to maximize the (net) benefit from the product, as perceived by the imperfectly rational consumer.

This behavioral market failure hurts consumers and undermines efficiency. Policymakers are paying increasing attention to these problems, and they are responding with increasingly sophisticated regulatory tools. The idea is to empower consumers by giving them information that they can use to make better product-choice and product-use decisions. In the UK, the Cabinet Office published the Consumer Empowerment Strategy, featuring the “mydata” initiative, which “will enable consumers to access, control and use data currently held about them by businesses.” In the USA, Cass Sunstein, Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs at the White House, and co-author of Nudge, is promoting “Smart Disclosure” policies, designed to help “provide consumers with greater access to the information they need to make informed choices.”

These policies are not just about disclosing more information. Sellers already provide heaps of information that most consumers cannot read or understand. The challenge is to design disclosures that can really empower consumers and solve the behavioral market failure. To accomplish this goal, disclosure regulation must adopt one of the following two strategies:

Simple disclosures target consumers. The idea is to design aggregate, one-dimensional disclosures that facilitate comparison between competing products. For example, cell phone companies could be required to disclose the total annual cost of using a cell phone. The disclosure would combine both product-attribute information and product-use information. The annual cost of cellular service would combine rate information with the consumer’s use-pattern information. Such simple, aggregate disclosures would help imperfectly rational consumers make better choices.

Re-conceptualized disclosure is aimed not at imperfectly rational consumers, but at sophisticated intermediaries. Accordingly, this disclosure could be more comprehensive and complex. Consider a consumer who is considering switching from her current cell phone company to a competing provider. Consider also an intermediary who wishes to help the consumer identify the best plan for her needs. The intermediary has information on the different plans offered by all cell phone companies. The intermediary, however, has little information on how the specific consumer uses her cell phone. Since different plans can be optimal for different consumers, depending on their use patterns, not having product-use information substantially reduces the ability of the intermediary to offer the most valuable advice. Now, the consumer’s current cell phone company has a lot of information on the consumer’s use patterns. It could be required to disclose this information in electronic form so that the consumer could forward it to the intermediary. The intermediary could then combine the product use information with the information it has on different plans and provide the consumer with valuable advice.

Consumer contracts are ubiquitous. They produce substantial benefits, but can also cause substantial harm. Policymakers can help by mandating, or encouraging, disclosure of information that would empower consumers to make better choices. The challenge is to design effective disclosure policies.

Oren Bar-Gill is Professor of Law and co-Director of the Center for Law, Economics and Organization at the New York University School of Law. He is the author of Seduction by Contract: Law, Economics, and Psychology in Consumer Markets. For his work on consumer contracts, Bar-Gill received the inaugural Young Scholar Medal from the American Law Institute.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 31, 2012

Reading Tea Leaves

With Mitt Romney’s trip abroad to visit Israel, Poland, and Great Britain, the focus of the 2012 presidential campaign shifts briefly to foreign policy. The Romney people hope to project the image of their candidate as a credible head of state and commander-in-chief, as well as to score some political points at home. The visit to Israel, a nation President Obama hasn’t visited during his first term, seems designed to stir doubts about the incumbent among American Jews, long one of the most reliable Democratic voting blocs. This is all pretty standard fare for presidential candidates. We are unlikely to learn much during the trip about what kind of foreign policies Romney would pursue if elected.

Indeed, his campaign seems determined to steer the public conversation away from international questions, preferring to contest the election on the sluggish American economic recovery. His surrogates have resisted calls that he clarify his Afghanistan policy, on the curious grounds that “real Americans” don’t care about it. In a July 24th speech to the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Romney condemns the president and his administration for national security leaks that serve administration political purposes. (Under a Romney administration, one presumes, leaks will cease and horses will learn to fly.) And the Republican candidate also warns against the looming defense expenditure reductions that would be required under sequestration, another stance that the GOP hopes will have some political traction in November. None of this adds up to anything like a coherent foreign policy stance.

The avoidance of foreign policy encourages campaign observers to try to tease out Romney’s foreign policy views based on fragments of evidence. One recent line of speculation focuses on the people around the candidate, his foreign policy advisers. This approach has given rise to alarmist concerns that a Romney victory would usher in the Second Coming of the Bush 43 neoconservatives who gave us the mishandled wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Thus in a piece in The Nation, Ari Berman concludes that Romney’s policy statements during the primaries and his cast of advisers “suggest a return to the hawkish, unilateral interventionism of the George W. Bush administration should he win the White House in November.” Similarly, Colin Powell cautions about the foreign policy people around the GOP candidate, “I don’t know who all of his advisers are, but I’ve seen some of the names and some of them are quite far to the right. And sometimes they might be in a position to make judgments or recommendations to the candidate that should get a second thought.”

Not so fast. Others who scan the names of the Romney foreign policy team see not Bush 43 resurgent but the more sober realism of Bush 41. They maintain that longtime Republican administration stalwarts such as Henry Kissinger, James Baker, and George Shultz have the candidate’s ear; another adviser is John Lehman, Secretary of the Navy in the Reagan administration. According to some “insiders” (itself an ambiguous term), the realists, though hawkish, offset the influence of extreme neocons such as John Bolton.

That Romney would draw on a spectrum of Republican foreign policy hands makes sense, of course. Were he to tilt strongly in one direction, he would be committing himself sooner than he needs, and the resulting political fall-out would damage his campaign with some segment of the electorate.

More fundamentally, we should ask whether we can tell much about a president’s foreign policy from the cast of characters he installs around him. In part, they are intended to send signals about the new administration. George W. Bush, who appreciated his lack of foreign policy experience, sought to offset this weakness by picking seasoned advisers such as Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and Colin Powell. The public, along with the international community, could take comfort from the presence of these “grown-ups”; the neoconservative ideologues occupied second-tier positions in his administration, removed from the seat of power. Rumsfeld seemed to be on the same page as Bush, too, in their shared distaste for nation building. Before 9/11, few would have predicted that the president and his team (Powell and Rumsfeld both partly excepted) would have signed on for the most ambitious effort to remake a society that the United States has attempted since the end of the Second World War.

The more serious question about Mitt Romney as a possible president, then, is how much space he would have to reshape American foreign policy. He faces serious budget constraints that will mock his call to increase defense spending, not to mention a lack of public support for higher outlays. Although he has questioned the pace of American troop withdrawals from Afghanistan, here, too, he is out of step with public opinion. On a series of issues, ranging from USA-China relations to Iran sanctions to North Korea, it is difficult to see that a “hard line” approach would differ significantly from what the Obama administration and its predecessors have done. Notwithstanding the worries in some quarters that a Romney victory would mean a return to the “Bush-Cheney doctrine” that “eagerly embraces military force without fully considering the consequences,” that time has passed. No set of advisers can bring it back in 2013.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

AURORA, CO – JUNE 20: Republican presidential hopeful Mitt Romney speaks with the media after visiting the Brewery Bar IV on June 20, 2011 in Aurora, Colorado. Romney met with a group of small business owners at the Colorado bar on a campaign stop before attending an evening fundraiser. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images) Source: Photo by EdStock2, iStockphoto.

The advantages and vanity of Moll Flanders

On 31 July 1703, Daniel Defoe was placed in a pillory for the crime of seditious libel. A bold businessman, political satirist, spy, and (most importantly) writer, he had a sympathetic crowd who threw flowers instead of rocks or rotten fruit. We’re celebrating this act with an excerpt from another bold soul, this time from Defoe’s imagination. In a tour-de-force of writing, Moll Flanders tells her own story, a vivid and racy tale of a woman’s experience in the seamy side of life in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century England and America. Let’s hear from Moll on her advantages and vanity.

By this means I had, as I have said above, all the Advantages of Education that I could have had, if I had been as much a Gentlewoman as they were, with whom I liv’d, and in some things I had the Advantage of my Ladies, tho’ they were my Superiors; but they were all the Gifts of Nature, and which all their Fortunes could not furnish. First, I was apparently Handsomer than any of them. Secondly, I was better shap’d, and Thirdly I Sung better, by which I mean, I had a better Voice; in all which you will I hope allow me to say, I do not speak my own Conceit of myself, but the Opinion of all that knew the Family.

I had with all these the common Vanity of my Sex. That being really taken for very Handsome, or if you please for a great Beauty, I very well knew it, and had as good an Opinion of myself, as any body else could have of me; and particularly I lov’d to hear any body speak of it, which could not but happen to me sometimes, and was a great Satisfaction to me.

Thus far I have had a smooth Story to tell of myself, and in all this Part of Life, I not only had the Reputation of living in a very good Family, and a Family Noted and Respected every where, for Vertue and Sobriety, and for every valuable Thing; but I had the Character too of a very sober, modest, and virtuous young Woman, and such I had always been; neither had I yet any occasion to think of any thing else, or to know what a Temptation to Wickedness meant.

But that which I was too vain of, was my Ruin, or rather my vanity was the Cause of it. The Lady in the House where I was, had two Sons, young Gentlemen of very promising Parts, and of extraordinary Behaviour; and it was my Misfortune to be very well with them both, but they manag’d themselves with me in a quite different Manner.

The eldest a gay Gentleman that knew the Town, as well as they Country, and tho’ he had Levity enough to do an ill natur’d thing, yet had too much Judgment of things to pay too dear for his Pleasures; he began with that unhappy Snare to all Women, take Notice upon all Occasions how pretty I was, as he call’d it; how agreeable, how well Carriaged, and the like; and this he contriv’d so subtilly, as if he had known as well, how to catch a Woman in his Net, as a Partridge when he went a Setting; for he wou’d contrive to be talking this to his Sisters when tho’ I was not by, yet when he knew I was not so far off, but that I should be sure to hear him: His Sisters would return softly to him, Hush Brother, she will hear you, she is but in the next Room; then he would put it off, and Talk softlier, as if he had not known it, and begun to acknowledge he was Wrong; and then as if he had forgot himself, he would speak aloud again, and I that was so well pleas’d to hear it, was sure to Lissen for it upon all Occasions.

After he had thus baited his Hook, and found easily enough the Method how to lay it in my Way, he play’d an opener Gamel and one Day going by Sister’s Chamber when I was there, doing something about Dressing her, he comes in with an Air of gayty, O! Mrs Betty said he to me, How do you do Mrs. Betty? don’t your Cheeks burn, Mrs Betty? I made a Curtsy, and blush’d, but said nothing; What makes you talk so Brother, says the Lady; Why, says he, we have been talking of her below Stairs this half Hour; Well says his Sister, you can say no Harm of her, that I am sure, so ‘tis no matter what you have been talking about; nay, says he, ‘tis so far from talking Harm of her, that we have been talking a great deal of good, and great many fine Things have been said of Mrs. Betty, I assure you; and particularly, that she is the Handsomest young Woman in Colchester, and, in short, they begin to toast her Health in the Town.

Moll Flanders, whose real name we never discover, cleverly defies the traditional depiction of women as helpless victims. First published in 1722, and one of the earliest novels in the English language, its account of opportunism, endurance, and survival speaks as strongly to us today as it did to its original readers. This new edition offers a critically edited text and a wide-ranging introduction by Linda Bree, who sheds light on the circumstances out of which the novel grew, its strengths and weaknesses as fiction, and the social and cultural issues examined in the novel. Daniel Defoe was a prolific writer of pamphlets, journals, and books, including some of the earliest novels. Read a previous post on Daniel Defoe and the Journal of the Plague Year by David Roberts, Professor and Head of English at Birmingham City University.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Wedding Music

The summer wedding season is in full swing and many of us will have attended a ceremony or two by the time it’s over. My little sister was married on July 15, and the months leading up to the event were very busy ones for my family members, who planned and prepared the entire event themselves.

Like many brides, my sister paid particular attention to the ceremony music. She chose the processional on her own (the second movement of “Winter” from the Four Seasons by Antonio Vivaldi), and the other pieces were suggested either by the organist or by me, the singer. After some deliberation, she ended up with a combination of the more well-known (George Frideric Handel’s “Hornpipe” from Water Music) with the fairly obscure (“Hands, Eyes, and Heart” from Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Four Last Songs, which I first heard in an art song repertoire class in graduate school).

If a bride and groom don’t wish to spend time creating a personalized repertoire, they can always default to the standard fare for the ceremony—pieces like the astutely nicknamed “Here Comes the Bride,” an organ arrangement of the bridal chorus (“Treulich geführt”) from Richard Wagner’s 1850 opera Lohengrin.

This excerpt can seem to be either an obvious selection for a wedding or a ridiculous one, depending on how you look at its context in the opera. In Lohengrin’s third act, this chorus accompanies the newly married Elsa and Lohengrin’s entrance to the bridal chamber, “where the blessing of love shall preserve you.” This is shortly followed by the bride declaring her misgivings about the groom, the groom’s mounting remonstrations, and (not surprisingly, for a 19th-century opera), a homicide.

As you may have guessed, Elsa and Lohengrin’s marriage doesn’t turn out to be a long lasting one. So while a couple looking for a musical benediction of wedlock may find “Treulich geführt” a perfect choice for their wedding ceremony, those looking for something that in its original context augured a long, happy, murder-free union may find it doesn’t quite fit the bill. (Images of Hans Neuenfels’ 2010 production of the opera at Bayreuth, in which members of the cast were costumed as giant lab rats, make the bridal chorus feel like an even more unnerving selection.)

Click here to view the embedded video.

The tradition of incorporating Lohengrin’s bridal chorus into wedding ceremonies began only eight years after the opera’s première. The wedding ceremony of Princess Royal Victoria and Crown Prince Frederick of Prussia on 25 January 1858 was followed by a concert offered by Queen Victoria of nine musical selections, including “Treulich geführt”. Wagner, who was in exile in Switzerland for his participation in the Dresden insurrection when the opera was first performed, didn’t hear the work in performance himself until 1861.

In spite of tradition (or perhaps because of it), some presumptive brides and grooms consider the piece too much of a cliché to use in their own weddings. In 1963, Jessica Kerr put an ad in the Musical Times asking ministers and organists to write in with information on the kinds of music they used in weddings. In her resulting 1965 article on English weddings, she wrote that many reported using processional hymns instead of “Treulich gefürht,” which “provides a solution (among other advantages) for those who object to the Lohengrin Bridal Chorus, either because they consider it hackneyed, or because of its secularity.” For those who didn’t want to include expressly secular music in the wedding service, Kerr wondered why the bridal chorus, which is sung as Elsa and Lohengrin enter their bedroom, wasn’t replaced by the Procession to the Minster from the opera’s second act.

Yet almost 50 years after Kerr’s article was published, “Treulich gefürht,” continues to be requested. An organist friend of mine says she plays it for about 30–40% of the weddings she accompanies. It’s often paired with the “Wedding March” from Felix Mendelssohn’s incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, another work Queen Victoria requested for her daughter’s wedding celebration.

For most of us, the bridal chorus doesn’t conjure up the story of Elsa and Lohengrin any more than the Mendelssohn makes us think of Oberon or Titania. What both pieces do bring to mind is weddings in general — a vaguer, happier idea that’s still congruous with the original musical narratives. What’s more, I don’t know that most people preparing to get married care about the context in which the music they pick was written anyway. (The ones I’ve known that did care were musicians themselves and couldn’t help it.)

For that reason, and for the sake of tradition, I imagine “Treulich geführt” will continue to be used in wedding processionals for some time. May the marriages be happy ones, and may the subsequent rat attacks be few.

Jessica Barbour is the associate editor for Grove Music Online. You can read more about Wagner and Lohengrin on Oxford Music Online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

July 30, 2012

An ODNB guide to the people of the London 2012 opening ceremony

Where do you stand on Friday’s opening ceremony for the 2012 Olympic Games. Delighted, inspired, a little bit baffled?

There’s a possibility, we realize, that not all of the show’s 1 billion-strong audience will have caught every reference. So here’s the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography guide you to some of those who made it possible.

Top hat & Tor

After Isambard Kingdom Brunel (replete with top hat & cigar), you’ll find Hubert Parry, composer of the Jerusalem which evoked the ‘green and pleasant land’ from William Blake’s poem “Milton”. Brunel’s speech (on Glastonbury Tor) was accompanied by Edward Elgar’s ‘Nimrod’ suite, dedicated to the music critic August Jaeger.

Golly GOSH

In the aftermath of ‘Pandemonium’ came the suffragettes, led by Emmeline Pankhurst and with reference to the suffrage ‘martyr’ Emily Wilding Davison. The evening’s celebration of the NHS would no doubt have been appreciated by Nye Bevan — so too J.M. Barrie who gave the rights of Peter Pan to Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Bond & Beckham

Then things got stranger still. A march past of Pearly Kings and Queens, a starring role for Ian Fleming’s James Bond, a shower of Mary Poppinses, and a chance to pogo with “Pretty Vacant”.

Things were very different in the past as the story of the Edwardian pageant master, Frank Lascelles, reminds us. And though we don’t do power boats at the ODNB, we can give you a foretaste of David Beckham glamour: step forward Cornelius Drebbel, the first man to ‘speed’ down the Thames (in a submarine), in 1620.

Philip Carter is Publication Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. The Oxford DNB online is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day. In addition to 58,000 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 130 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @ODNB on Twitter for people in the news.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles about British history on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The medieval origins of 20th century anti-semitism in Germany

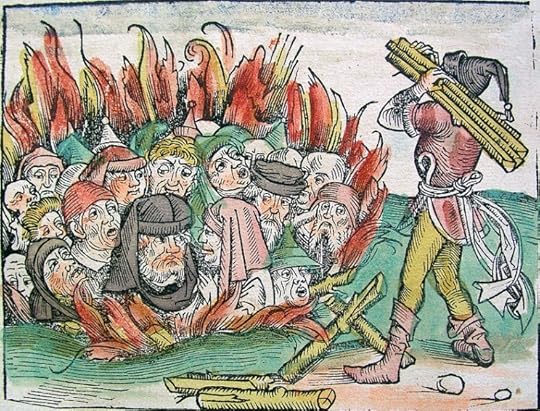

The burning of the Jews during the Black Death. Source: Liber Chronicarum, 1493.

When the Black Death struck in Europe, it killed between 30 and 70 percent of the population. What could account for such a catastrophe? Quickly, communities started to blame Jews for the plague. Pogroms occurred all over Switzerland, Northern France, the Low Countries, and Germany. Typically, the authorities in a location would be alerted to the “danger” by a letter sent from another town (Foa 2000). In typical cases, the city council then ordered the burning of the entire Jewish community.In 320 towns that had Jewish settlements during the 14th century, nearly three quarter (73%) saw pogroms; 88 did not. Many of these locations — with many annihilating their Jewish communities, and others leaving them untouched — are only a few kilometres apart.

In one case, we know more about what tipped the balance: Strasbourg. The city council originally refused to give credence to letters received, warning them of the danger of Jews poisoning the wells. A mob led by the tanner’s guild then deposed the ruling council. Its successor’s first act in office was to order the burning of Strasbourg’s Jews, over 2,000, on St. Valentine’s Day 1349. Here, it is clear what made the crucial difference — the willingness of a violent mob to effectively overthrow the established authorities in order to attack the Jewish minority (Cohn 2007).

Anti-Semitism in Interwar Germany

We compare local events in 1349 with anti-Semitism in the 1920s and 1930s because two shocks had similar effects. The plague lowered the threshold for violence against Jews; Germany’s defeat in World War I played a similar role. Blamed on revolutionaries and pacifists (many of them Jewish), political anti-Semitism revived with a vengeance after 1918. During the 1920s, several parties adopted anti-Semitic platforms; student associations voted to ban Jewish members; cemeteries were attacked; entire Spa towns declared themselves off limits to Jews.

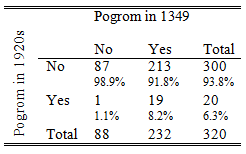

Remarkably, we find that a whole host of indicators of anti-Semitism in the 1920s and 1930s is closely correlated with events in 1349 — almost 600 years earlier. Our first measure is pogroms during the 1920s. We collect data from an encyclopedia on Jewish life in Germany (Alicke 2008), and use it as one indicator for the strength of anti-Semitic sentiment (Voigtländer and Voth 2011). The table on the left shows how their frequency stacks up, depending on whether a locality had witnessed attacks in the 14th century.

Remarkably, we find that a whole host of indicators of anti-Semitism in the 1920s and 1930s is closely correlated with events in 1349 — almost 600 years earlier. Our first measure is pogroms during the 1920s. We collect data from an encyclopedia on Jewish life in Germany (Alicke 2008), and use it as one indicator for the strength of anti-Semitic sentiment (Voigtländer and Voth 2011). The table on the left shows how their frequency stacks up, depending on whether a locality had witnessed attacks in the 14th century.

Of the 20 pogroms recorded, fully 19 took place in towns and cities with a record of medieval violence against Jews. The chances of attacks on Jews go up from 1/88 (1.1%) in locations without attacks in the 14th century to 19/232 (8.2%), an increase by a factor of 6.

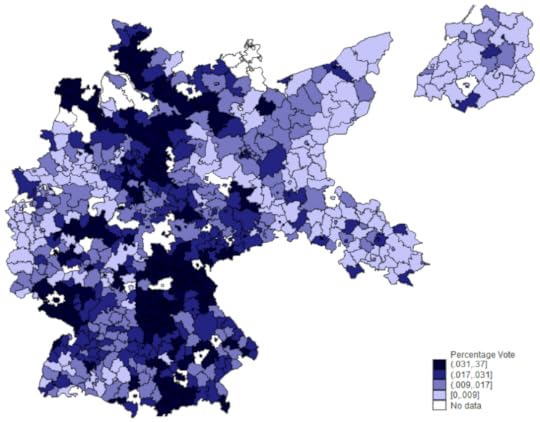

Other indicators confirm this conclusion. We use the Nazi Party’s performance at the polls in 1928 as an alternative indicator. This is the last election before it became a mass-movement attracting many protest voters; anti-Semitism was a relatively more important factor behind its appeal than in later years (Heilbronner 2004). The figure below shows the distribution of NSDAP vote shares in 1928. There is substantial variation even in close geographic proximity; counties with high vote share often have neighbors with low Nazi votes. We exploit this variation in our econometric analysis. While the overall share of the vote was not high (3.3%), we find that in places with a history of Jew-burning, the Nazi Party received 1.5 times as many votes as in places without it.

Votes for the Nazi Party, 1928.

Letters to Der Stürmer, a famously anti-Semitic Nazi paper, tell a similar story. Many of these urge more drastic action against Jews, denounce neighbors still having contact with Jews, etc. We hand-collected the location of each writer of a letter to the editors published in 1935, 1936 and 1937. After adjusting for differences in population size, there is a clear, strong association with 14th century attacks on Jews.

Similar effects exist for the number of Jews deported after 1939, which in our view reflects at least in part the energy of local party officials in finding those in hiding, and the strictness with which racial criteria were applied, appeals for exceptions turned down, etc (figure 3). Finally, we also find that towns and cities where Jews were murdered in 1348-50 saw more attacks on synagogues in 1938, during the so-called Night of Broken Glass. In combination, there is a consistent pattern of association across all five indicators of anti-Semitism between attitudes and actions in the 1920s and 1930s on the one hand, and medieval pogroms on the other.

Frequency of deportations of Jews, in locations with and without 14th century progroms.

Understanding the Link

Why did Germans hate Jews so violently in some places — but not in others — over such a long period? The question is puzzling. Jews largely disappeared from Germany after the 15th century, and only returned in large numbers in the 19th century.

To explain our finding of extremely long-term persistence, we emphasize three factors. First, Jew-hatred may have formed part of a broader pattern of beliefs about the role of outsiders vs. insiders. Where local populations generally convinced their children to mistrust foreigners, blame mishaps on outsiders, etc., the inclination to blame the Jews in times of misfortune, once they were present again, may have persisted for a long time. Second, the typical locality in our study is quite small. The median town had around 18,000 inhabitants in the 1920s. Where few migrants arrived, local culture can be extremely “sticky”. Third, Christians had to have some view on Jews, whether physically present or not. Jew-hatred was often an integral element in local cultural practices. One Bavarian town, Deggendorf, for example celebrated the destruction of its Jewish community in 1337 in every single year thereafter, until 1968.

Our findings thus reinforce recent research in economics that documents just how persistent culture is. Raquel Fernandez and Alessandra Fogli (2009) show that the fertility of the children of immigrants to America is still influenced by what is happening in the home countries from which their parents came; Nathan Nunn and Leonard Wantchekon (2009) argue that areas in Africa affected by the slave trade in the 19th century still show lower levels of trust; and Saumitra Jha (2008) found that Indian cities with a history of peaceful coexistence between Muslims and Hindus had lower levels of inter-ethnic violence in the recent past.

Our results transcend the existing literature by asking what factors can undermine persistence. We show that cities with a rich mercantile history — such as member states of the Hanseatic League, an association of trading cities — show no persistence; medieval pogroms have no predictive power for the 1920s and 1930s. Also, where population growth was particularly rapid in the 19th century, the link between the medieval and modern-day attitudes broke down.

The obvious next question is how much of persistent anti-Jewish culture is still around in Germany today. After 1945, the mass exodus of Germans from the East should have weakened cultural transmission; Jew-hatred changed from official policy to taboo. In related work, we investigate the link by examining surveys about racial attitudes in Germany conducted in the 1990s and 2000s, which ask question like “Are Jews responsible for their own persecution?” or “Would you mind if a Jew married into your family?” (Voigtländer and Voth 2012).

Nico Voigtländer is Assistant Professor, UCLA-Anderson, and a Faculty Research Fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Hans-Joachim Voth is ICREA Research Professor of Economics, UPF and CREI, Barcelona, and a CEPR Research Fellow. They are the authors of “Persecution Perpetuated: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Semitic Violence in Nazi Germany” in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Finding and classifying autism for effective intervention

People are finding autism in their families, pediatric offices, day cares, preschools, playgrounds, and classrooms. Individuals with autism are now portrayed in movies, television shows, news reports, and documentaries. The diagnosis of autism is being hotly debated in the media, academic medical centers, universities, autism centers, and advocacy agencies.

Autism, or soon-to-be-called Autism Spectrum Disorder, is a developmental neurobiological disorder, characterized by severe and pervasive impairments in reciprocal social interaction skills and communication skills (verbal and nonverbal) and by restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behavior, interests, and activities. The current DSM-IV-TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association) applies Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD) as the diagnostic umbrella, with five subtypes. With the upcoming proposed changes in DSM-5, the separate diagnostic classifications under PDD may be subsumed under one category Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). This puts autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, and childhood disintegrative disorder under ASD. The new proposed ASD diagnostic category would include specifiers for severity and verbal abilities, and also include associated features such as known genetic disorders, epilepsy, and intellectual disability. The new proposed ASD diagnostic category would also combine the current three domains (social, communication and behaviors) into two domains (social and communication deficits, and fixated interests and repetitive behaviors), based upon the belief that deficits in communication and social behaviors are inseparable. Much debate has been triggered by these proposed changes, especially regarding inclusion or exclusion of individuals currently diagnosed with autism, feared loss of school placement and funding, and the loss of identity of Asperger’s Disorder into the broader ASD.

Autism, or soon-to-be-called Autism Spectrum Disorder, is a developmental neurobiological disorder, characterized by severe and pervasive impairments in reciprocal social interaction skills and communication skills (verbal and nonverbal) and by restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behavior, interests, and activities. The current DSM-IV-TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association) applies Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD) as the diagnostic umbrella, with five subtypes. With the upcoming proposed changes in DSM-5, the separate diagnostic classifications under PDD may be subsumed under one category Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). This puts autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, and childhood disintegrative disorder under ASD. The new proposed ASD diagnostic category would include specifiers for severity and verbal abilities, and also include associated features such as known genetic disorders, epilepsy, and intellectual disability. The new proposed ASD diagnostic category would also combine the current three domains (social, communication and behaviors) into two domains (social and communication deficits, and fixated interests and repetitive behaviors), based upon the belief that deficits in communication and social behaviors are inseparable. Much debate has been triggered by these proposed changes, especially regarding inclusion or exclusion of individuals currently diagnosed with autism, feared loss of school placement and funding, and the loss of identity of Asperger’s Disorder into the broader ASD.

Reports from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) show an increase in prevalence of children identified with autism, emphasizing the need to sharpen the focus on early identification and improve accurate diagnostic assessment and evidence-based interventions, which will result in more successful outcomes. In addition, long-range planning and support throughout the developmental years and into adulthood is critical.

There has been considerable emphasis in recent years on the use of evidence-based practices in most fields, and especially in autism interventions. Interventionists represent many disciplines including education, psychology, psychiatry, pediatrics, neurology, speech and language, occupational therapy, and others. The National Research Council reported that services should include a minimum of 25 hours a week, 12 months a year, in which the child with autism is engaged in systematically planned, developmentally appropriate activity aimed toward identified objectives determined on an individual basis. Intervention should start early and continue through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

There is a strong push to develop and increase essential services for adults with autism after the school years (usually after age 21). Transition planning should begin by age 14 to maximize success. The transition process uncovers, develops, and documents the skills, challenges, goals, and tasks that will be important for a person with autism to promote movement from childhood supports to adult services. This can range from vocational training to supported employment to college preparatory, and many other possibilities. The development of social competency and independence skills are critical to success and an enhanced quality of life.

Martin J. Lubetsky, MD is Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and the Chief of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Services and Center for Autism and Developmental Disorders at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic of UPMC, and Chief of Behavioral Health at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Dr. Lubetsky is a past recipient of the Grandin Award from the Advisory Board On Autism and Related Disorders (ABOARD). He is co-editor and co-author of Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

How radioactivity helps scientists uncover the past

Radioactivity: A Very Short Introduction

By Claudio Tuniz

Neanderthal was once the only human in Europe. By 40,000 years ago, after surviving through several ice ages, his days (or, at least, his millennia) were numbered.

The environment of the Pleistocene epoch was slightly radioactive, the same way it is today, but this was not Neanderthal’s problem. The straw that broke the camel’s back was the arrival of a new human, during an already stressful period of extreme and rapid environmental change. The new humans were slender, talkative, and had a round head with a straight face and no protruding brow. They rapidly conquered the steppes, tundra and forests, stretching from Gibraltar to Siberia, where the Neanderthal had been happily striving for hundreds of thousands years, moving around to cope with the vagaries of the weather.

The Neanderthals had broadened their carnivorous diet to include fish, particularly seashells and mollusks. A variety of naturally occurring radioactive atoms contaminated the food that Neanderthals ingested — about the same radioisotopes we eat today, except for some bias introduced by recent accidents like that of Chernobyl and Fukushima. They included uranium, thorium, their decay products and potassium-40, naturally present in rocks and soils. Their ingestion would contribute an absorbed dose of about 300 microsievert per year to Neanderthal’s body, similar to the dose you receive from your meals today.

As uranium accumulated in Neanderthal’s bones, scientists are now able to determine their age, back to 500,000 years ago, measuring the residual radioactivity. This can be done in a non-destructive way analyzing the weak flux of gamma rays emitted by the skull or other bone remains, using sophisticated germanium detectors and other nuclear physics tools. Ideally, these measurements should be performed in special laboratories like those under the Gran Sasso Mountain, in Italy, run by the Italian Institute of Nuclear Physics. The noise from cosmic rays and environmental radioactivity is so low in these underground laboratories that scientists can reveal the neutrinos emitted by the uranium burnt in nuclear reactors thousands of kilometers away, with useful applications. For example, one could detect whether plutonium, a key ingredient for nuclear bombs, is illegally produced somewhere on the globe.

We will resume below the discussion on nuclear bombs and artificial radioactivity. First, let’s complete the inventory of natural radioactivity sources during Neanderthal times. Like in the present, a radiation of cosmic origin was bombarding the atmosphere, creating new natural radioisotopes that would enter the food cycle. One of these products was radiocarbon. After being produced 40,000 years ago, a fraction of the radiocarbon atoms that were originally present in the bone, about 8 per thousand, survived to the present. The fact that carbon-14′s half-life is 5,730 years makes it the perfect clock to measure with high precision the ages of bones during the last 50,000 years. Indeed, it can be used to study not only the history of the Neanderthals, including the length of their overlap with modern humans, but also that of other human species that existed 40,000 years ago, like Homo floresiensis, nicknamed the ‘hobbit’, whose bones were found in 2003 on a small Indonesian island.

Only the round-headed humans, who arrived in Europe from Africa 40-45,000 years ago, eventually survived. These humans become a global species. Their powerful minds allowed them to conceive art, music, new ways of hunting animals, and fighting different humans. Radioactivity-based clocks confirm that their appearance coincided with the demise of other human species and the extinction of the large animals of the Pleistocene, like Diprotodon and Genyornis in Australia and Smilodon in America.

By discovering natural radioactivity at the end of the nineteenth century, the so-called ‘modern humans’ became capable of reconstructing the detailed history of their ancestors, providing exact dates for the rock art of Chauvet in France and the ‘Venus’ of Hohe Fels in Germany 35,000 to 40,000 years ago.

These humans also learned, in the twentieth century, how to create their own form of radioactivity. While my generation was listening to the first songs of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, the US and USSR were exploding nuclear bombs in the atmosphere, the ultimate expression of human insanity. Many of the techniques, including mass spectrometers and radiation detectors, useful for dating hominids, were developed by the same scientists who built these nuclear bombs.

The radiation produced by the explosions increased the amount of radiocarbon in the terrestrial environment until 1962, when it reached a concentration that was twice that of the pre-nuclear era. This was the time when Kennedy and the other representatives of the nuclear powers of the time signed the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

As a teenager, I received this spike of man-made radiocarbon in my bones. Since then, the concentration of the artificial radiocarbon in the environment has been decreasing, with a half-life of 15 years, due to the exchange of carbon with the biosphere and the oceans.

The radiocarbon bomb pulse offers new applications as a chronometer in forensic science, as shown in popular TV series like CSI and Cold Case. The radiocarbon analysis of a bone sample provides the time of death of an individual during the last 50 years with a precision of a few months. In recent years, this method was applied to investigate the mass killings carried out by the Nazis in Ukraine at the end of World War II and the war crimes perpetrated in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

Some believe the destructive attitude of H. sapiens has deep roots.

Claudio Tuniz leads a programme on advanced x-ray analyses for palaeoanthropology at the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics. He was Assistant Director of the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste . Previously he was Nuclear Counsellor at the Australian Embassy to the IAEA in Vienna and Director of the Physics Division at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organization in Sydney. He is co-author of the book The Bone Readers (2009), and the recently published Radioactivity: A Very Short Introduction (2012).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers