Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1034

August 11, 2012

Enid Blyton

Happy Birthday Enid Blyton! This giant of children’s literature was born on 11 August 1897. To celebrate, here is an edited extract from the Enid Blyton entry by David Rudd in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature edited by Jack Zipes (© Oxford University Press 2006).

Enid Blyton (1897–1968), was an English children’s writer, born in London, who became one of the most prolific and best-selling children’s writers of all time, producing an estimated seven hundred books, including some four thousand short stories. She initially trained as a teacher, publishing her first book, Children’s Whispers, a book of verse, in 1922. In her early work, Blyton was regarded as an educator, writing a regular column for Teachers World (1922–1945) and producing books of stories, poems, and games, besides more substantial, multivolume works of school curricula.

Commercial Success

In 1926 she launched Sunny Stories for Little Folks, supported by her husband, Hugh Pollock, an editor at Newnes, the magazine’s publishers. She began by retelling traditional stories, gradually moving to her own, original works, such that by 1937 the magazine was retitled Enid Blyton’s Sunny Stories. It was in this year that Adventures of the Wishing Chair was serialized, to become her first full-length novel.

This was to augur Blyton’s most creative period, introducing many of her best-known series: the “Magic Faraway Tree” books, beginning with The Enchanted Wood (1939), the “Naughtiest Girl” (1940) and “St Clare’s” school series (1941), the “Find-Outers” (1943) and “Adventure” (1944) series and, most successfully, the “Famous Five,” beginning with Five on a Treasure Island (1942).

By the end of World War II, Blyton had become an institution. From then on, in the eyes of adult gatekeepers, her status began to decline — something that her three remaining major series, all first appearing in 1949, did nothing to challenge: “Barney” (The Rockingdown Mystery, etc), “Secret Seven,” and “Noddy.” It was the latter, the story of a wooden doll in Toyland, that was Blyton’s biggest commercial success. The books were groundbreaking in their design, with full-color illustrations on every page (by the Dutch artist Harmsen van der Beek), and sold an astonishing 20 million copies in the UK during the 1950s. Noddy, with his attempts at gaining recognition in an alien world, was immensely popular with young children. The character transferred to television and theater and generated extensive product merchandising—even though many adults resented the “witless, spiritless, snivelling, sneaking doll,” as Colin Welch described him. By 1970 some 125 Noddy titles had been produced.

Critical Response

Blyton’s productivity in the early 1950s was prodigious, averaging fifty publications a year (an amazing sixty-nine titles in 1955). This was aside from her fortnightly Enid Blyton Magazine, which she started in 1953, after leaving Sunny Stories. However, health problems forced her to abandon the magazine in 1959, and her current serials dried up soon thereafter, loss of memory clouding her final years.

It was during this period that criticism of her work became most vociferous. The child that grew up on Blyton was seen as a child at risk, her books being “slow poison.” A moral panic ensued, with claims that local authorities were banning her works. Most of this was media hype, but the criticism was unrelenting, and became increasingly focused on the social unacceptability of Blyton’s work. There were accusations of racism because of her use of golliwogs and representation of foreigners. She was accused of sexism because many of her female characters were seen as subservient, often enjoying domestic activities. Finally, she was accused of a general middle-class, little England snobbishness. Now that several generations of Blyton readers have healthily matured, including many respected writers, these criticisms seem ludicrous. However, the books have been revised to remove offending passages and images.

At her death, Blyton was the third most translated author in the world and, even today, her work continues to sell healthily in much of the world. Chorion, which bought Enid Blyton Ltd in 1996, has also successfully exploited new markets and new media, seeking to make her the British Disney. Imaginative marketing, however, cannot fully explain the “Blyton phenomenon.” Her persistent, widespread popularity over eighty years, has other facets. She certainly writes in a highly accessible manner, reinforced by her excellent pacing of story, deft plotting, and clear moral framework — all of which help to establish fluent reading in children, besides showing them the narrative conventions of story: how stories work. Blyton also uses many of the tried and tested conventions of the oral storyteller: stock characters, formulaic phrasing, action-driven plots, and magical outcomes in which protagonists triumph and “baddies” receive their “come-uppance.” These features give her work an immediacy, so that it unfolds like a reverie, seemingly fulfilling her young audience’s wishes. Her bare, uncluttered prose aids this, permitting almost any reader, regardless of sex or cultural background, to access her tales and sketch in their own local coloring, as they position themselves alongside the protagonists. Blyton furthered this notion of speaking directly to her audience by encouraging their involvement and feedback through her magazines and various clubs.

In this way she could hone her more successful creations, like the “Famous Five,” which ran to twenty-one books over as many years. The series features three siblings, Julian, Dick, and Anne, plus their cousin, George, and Timmy, her dog. This mix was to appeal to both boys and girls who, collectively, could unite against an untrustworthy adult world. The books certainly have enough page-turning adventure and mystery, but they also provide security, with an emphasis on building cosy hideaways and communal feasting. Anne has been much criticized for representing the little housewife, but the domestic power she manages to wield over her older, male siblings should not be belittled. She is also a useful foil for the tomboy, George (Georgina), whom many girl readers have found a liberating role-model, especially with her powerful canine ally, Timmy. Blyton’s school series, “St. Clare’s” and “Malory Towers,” push this empowerment further, creating an all-female world where girls, beyond the confines of patriarchy, can live more liberated lives.

So, for all Blyton’s poor writing and political incorrectness, she remains an author hugely popular with children, adult disapproval no doubt fueling their enjoyment. She not only offers the child imaginative space and a voice but also celebrates a world in which children can both disapprove of, and outwit, adults.

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature is the winner of a RUSA Best Reference of 2006, a Booklist 2006 Editor’s Choice, and a Library Journal Best Reference of 2006. In addition to print books, it is also available on Oxford Reference Online. It offers comprehensive coverage of children’s literature, from medieval chapbooks of moral instruction for children to J. K. Rowling’s immensely popular Harry Potter books. It documents and interprets every work, major and minor, that has played a role in the history of children’s literature in the world. General essays illuminate prominent trends, themes, genres, and the traditions of children’s literature in many countries. In addition, the Encyclopedia provides biographies of important writers, as well as extensive coverage of illustrators with numerous examples of their work. Sociocultural developments such as the impact of toys, films, animation, the Internet, literacy, libraries and librarians, censorship, the multicultural expansion of the field, and other issues related to the appreciation and dissemination of children’s literature are also addressed. The editor, Jack Zipes, is a Professor of German at the University of Minnesota, United States.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 10, 2012

Where are the ‘Isles of Wonder?’

’s spectacular opening ceremony at the London Olympics on 27 July 2012 was entitled Isles of Wonder. As many will have noticed, it was shot through with references to the medieval and early-modern past. Mike Oldfield’s performance of In Dulce Jubilo, a 1970s reworking of a late-medieval German-Latin carol, provided one of the most exuberant moments. In Stratford, dancing nurses accompanied it. There were many references to and quotations from Shakespeare as well. The focal point of the ceremony was a copy of Glastonbury Tor, the Somerset hill identified with the Arthurian Isle of Avalon, home of the magical sword Excalibur and King Arthur’s final resting-place. Boyle’s ceremony may have looked very contemporary, and certainly had a redeeming dose of postmodern irony, but the medieval and early-modern past is never far away in England. Even an Olympic mascot has a medieval name: Mandeville, named after Stoke Mandeville Hospital where the Paralympics originated. Mandeville is also an Anglo-Norman place-name (magna ville, large town) and the surname of one of the main writers of medieval wonders, Sir John Mandeville whose Book of Marvels and Travels I have just edited and translated.

Mandeville and Mandeville. London 2012 mascot and medieval traveller.

The idea of ‘isles of wonder’ has a long history indeed and we can trace some of the allusions used in the Olympic Opening Ceremony.

BERMUDA

It is perhaps the very title of Danny Boyle’s extravaganza, Isles of Wonder, which evokes a vanished olde worlde of prodigies, monsters, marvels, and miracles. This allusion was made clear in Kenneth Branagh’s turn; the actor took his words from the monster Caliban from Shakespeare’s romantic play of discovery, The Tempest (1611). Branagh started the ceremony by quoting Caliban, “Be not afeard, be not afeard.” These are the words Caliban, a ‘savage’ inhabitant of an island settled by Europeans after a shipwreck, says to explain the “noises, sounds, and sweet airs” that appear marvellously on his foreign island. It has been reported that Boyle wanted to frighten the audience at the opening ceremony. When the Olympic flame entered the stadium, the accompanying music by Underworld was called “Caliban’s Dream,” as fright turned to wonder.

Shakespeare’s isles of wonder were not British isles. Instead, most scholars agree that The Tempest seems to combine the Mediterranean with elements of Bermuda or the Caribbean. Shakespeare was writing in the era of Atlantic discovery, Bermuda having been settled by the Virginia Company in 1609. The play contains a reference to the “still-vexed Bermoothes,” calling this frightening novelty of an island to mind. The Tempest can be seen as staging the encounter between the Europeans and the native inhabitants, not least in the way the Europeans (shipwrecked in exile from Milan) try at once to flee, to tame, and to understand the various wonders on the island.

Shakespeare’s play variously describes Caliban as “legged like a man” with “fins like arms,” a “monster of the isle with four legs,” “no fish but an islander” with “a very ancient and fish-like smell,” a “moon-calf,” “a most perfidious and drunken monster,” and “a savage and deformed Slave.” Caliban, a misspelled Caníbal who can be read sympathetically as a fantasy of the Europeans, is a wonder, a marvel, a thing that fascinates the Europeans but one they struggle to identify. Gonzalo, one of the Europeans, says, “All torment, trouble, wonder and amazement inhabits here: some heavenly power guide us out of this fearful country!” Caliban, on the other hand, utters the lines repeated at the Olympics by Branagh: “be not afeard.”

AVALON

Boyle’s ceremony made many clever connections, not least between Caliban’s ‘isle of wonder’ and Glastonbury Tor — the original British ‘isle of wonder’ said to be the site of the Isle of Avalon. The legendary Avalon was largely invented by Geoffrey of Monmouth (d. c. 1155), who was also responsible for the stories of Arthur and Merlin as we know them today. Geoffrey described Avalon as “The Fortunate Isle” which “produces all things of itself” : growing it owns food, especially apples, so it’s not dependent on anyone else and so people who live there enjoy long, healthy lives. It is, then, a northern Paradise.

Glastonbury’s cone-shaped ‘tor’ became identified, thanks to the fanciful historian Gerald of Wales (d. c. 1223), with Avalon. Glastonbury Tor was a kind of ‘island’ surrounded by marshes, with a community of monks who sought to put themselves at the centre of an invented tradition of national origins. But, in the best medieval tradition, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s description of Avalon wasn’t original; it was actually taken from the writings of the godfather of marvels, Isidore of Seville (d. 636). Isidore described ‘isles of wonder’ (thought to be the Canary Islands), blessed with good fortune, growing their own food, and this passage was clearly Geoffrey’s source for his description of Avalon.

In Geoffrey of Monmouth’s history and in Shakespeare’s play, as in Danny Boyle’s Olympic ceremony, isles of wonder look marvellous, magical, and sometimes frightening but upon examination, isles of wonder turn out to be fantasies of home and nothing to be afraid of.

Anthony Bale is Professor of Medieval Studies at Birkbeck College, University of London. He has recently edited and translated Sir John Mandeville’s Book of Marvels and Travels for Oxford University Press’s Oxford World’s Classics, a text which deals with many wonders.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Mandeville (London 2012 mascot) photo by David Poultney for LOCOG (03.10.11 ). Courtesy of London 2012.

John Mandeville from Travels, c. 1459. Source: NYPL Digital Gallery.

The science behind drugs in sport

What is cheating? What drug compounds for performance enhancement are legal and why? Why do the sports drug classification systems change all the time? If all the chemicals were legal, what effect would this have on sport? Biochemist and author Chris Cooper explores the biological, moral, political, and ethical issues involved in controlling drug use in sports.

Below, you can listen to Chris Cooper talk about the topics raised in his book Run, Swim, Throw, Cheat. This podcast is recorded by the Oxfordshire Branch of the British Science Association who produce regular Oxford SciBar podcasts.

Listen to podcast:

[See post to listen to audio]

Chris Cooper is Head of Research, Sports and Exercise Science at the University of Essex and the author of Run, Swim, Throw, Cheat: The Science Behind Drugs in Sport. He is a distinguished biochemist with over 20 years research and teaching experience. He was awarded a PhD in 1989, a Medical Research Council Fellowship in 1992, and a Wellcome Trust University Award in 1995. In 1997 he was awarded the Melvin H. Knisely Award for ‘Outstanding international achievements in research related to oxygen transport to tissue’ and in 1999 he was promoted to a Professorship in the Centre for Sports and Exercise Science at the University of Essex. His research interests explore the interface of scientific disciplines. His current biochemical interests include developing artificial blood to replace red cell transfusions. His biophysics and engineering skills are being used in designing and testing new portable oxygen monitoring devices to aid UK athletes in their training for the London 2012 Olympics. In 1997 he edited a book entitled Drugs and Ergogenic Aids to Improve Sport Performance.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Did you know that we’re all made of stars?

Stars: A Very Short Introduction

By Andrew King

What are you made of? You may never have thought about it before, but every atom in your body was once part of a star, even several stars in succession. And almost all the elements that make up your body — carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and so on — would not exist at all without the stars.

How can I make such statements? Because astronomers know fairly well how stars work, and have overwhelming evidence to support these assertions and many others. Our understanding of how stars work has been growing for more than a century, in parallel with developments in physics, and is now very sophisticated.

We now know how stars live and how they die, and where to find their dead bodies. We understand how they make all the chemical elements beyond hydrogen, and how these elements are distributed through space, ultimately to make planets, and eventually in a few cases, life. We are learning how new stars are born from the ashes of older ones.

We know all this because stars are surprisingly simple physical systems, whose behaviour is governed by well-understood physical laws. Roughly speaking, we can model a star simply as a (very massive) ball of gas – almost entirely made of hydrogen, the simplest chemical element of all.

We can use physics to work out how a ball of gas like this would behave and evolve, and then compare these predictions with observations astronomers make of the stars around us.

Source: The Hubble Heritage Team (AURA / STScI / NASA).

We live very close to a star — the Sun — and our everyday experience immediately gives us some simple insights. First, we all know that the surface of the Sun is very hot, and gives us light and heat. This is after all what sustains almost all life on Earth, including our own. We survive by eating plant food which grew by absorbing sunlight, or by consuming meat from animals which ate plants.

The Sun is losing energy in sunlight all the time, and this fact already tells us that it must have a finite life; it must run out of energy at some point. Fortunately for us, it turns out that the Sun is only about halfway through an extremely long lifetime of about ten billion years, so we still have about five billion years to go.

You might wonder why, instead of gradually losing all this energy, the Sun does not simply cool down. Of course life itself would not exist on Earth after this happened, so we could never be there to see this melancholy event. But the Sun (fortunately for us) is actually forced to go on giving out sunlight in its prodigal way simply because its interior must be even hotter than its surface; if not, the pressure in the centre of the Sun would not be strong enough to support its enormous weight. The centre of the Sun must have a temperature of about 10 million degrees Celsius to stop the Sun collapsing to a much smaller (and dimmer) object.

A temperature like this is unimaginable, but has an enormous significance.

The gas in the centre of the Sun is so hot that hydrogen atoms can fuse together to make helium atoms. This fusion process is the same that gives the hydrogen bomb its frightening power. Every time it occurs, it releases huge amounts of nuclear energy. Normally this remains dormant, locked in the nucleus of every chemical element. The release is so enormous that just converting one kilogram of hydrogen into helium would supply the entire energy consumption of the entire world for 8 minutes, or the USA alone for about half an hour.

So fusing the nuclei of chemical elements together can release energy, and support the star against its own gravity. You can perhaps now guess how the other elements are made in stars. The temperature rises to the point where for example, helium atoms fuse, to make a combination of carbon and oxygen atoms, and so on. The centres of stars are the only places in the universe where gas is hot enough and dense enough to make these atoms. So take a look at the carbon atoms making up your skin; they were made in a star.

The Sun, and the myriad stars like it, shine because they can resist gravity by doing so. But in the end this resistance is futile: eventually every star exhausts its nuclear fuel and must collapse on itself under gravity, eventually making a cold dead star which can evolve no more.

Astronomers can find these stellar corpses as white dwarfs, neutron stars and black holes.

But these deaths can leave a legacy. As a star collapses towards death, it may throw off its outer layers of gas into space. These are enriched with the new elements created by fusion, and this process gradually adds these elements to all the matter in the universe. Eventually new stars, and often planets around them, form out of this material.

Which is where we came from.

Andrew King is Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Leicester.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 9, 2012

Komen leadership in flux

On Wednesday, Komen President Liz Thompson announced her plans to leave Susan G. Komen for the Cure next month. Founder Nancy Brinker will also give up her role as Komen CEO and serve as chair of the board as soon as a replacement is found, and two board members are stepping down, Brenda Lauderback and Linda Law.

The news comes exacly one week after Komen was criticized once again in a key public forum, this time by MDs who called out the organization for the exaggeration and distortion of medical information in its 2011 advertising campaigns about the benefits of screening mammography. The authors of the British Medical Journal, Steven Woloshin, MD, and Lisa M. Schwartz, MD, pointed out fallacies and exaggerations in Komen’s advertising and argued that “Women need much more than marketing slogans about screening: they need – and deserve – the facts.”

The fact is, this was not the first time Komen was criticized for failing to provide accurate and useful health information to improve the lives of those living with, and at risk for, breast cancer. The organization has also been denounced for overzealousness in protecting its trademarks, reducing its despite record revenues, profiting from a disease in the name of its cure, and putting corporate and political agendas in the way of patients’ rights and access to quality care.

By February of 2012 Komen’s decision to cut ties with Planned Parenthood (and then the semi-reversal of that decision following public outcry), sent the organization into a frenzied state of damage control. Attendance at Komen events declined. Donations dropped. Komen immediately sought advice from a former White House press secretary in the George W. Bush administration, Ari Fleischer, and hired a consulting firm founded by former Democratic pollsters to assess Komen’s reputation and identify the type of “apology” that would be most helpful for restoring credibility.

Komen founder Nancy Brinker apologized to Planned Parenthood, Congress, the public, and to Komen affiliates on behalf of the organization, but the vague “mistakes were made . . . we’ve learned a lot . . . let’s heal and get past this” storyline didn’t ring true. Eve Ellis, who served on Komen’s New York affiliate board for six years and raised over $250,000 for the group, publicly rebuffed Brinker’s apology. She said in an open letter that Brinker needed to take some “truth serum.” From Ellis’s experience, she did not believe Komen’s Planned Parenthood decision was apolitical, and she said the only way she would consider supporting the charity again would be for the organization to clean house, starting with the resignations of Nancy Brinker and the entire board of directors.

A petition on Change.org reiterated Ellis’s statement and the growing sentiment that Komen’s top leadership needed to go, citing “abuses of the public trust and failures of corporate governance (such as hiring Karen Handel to be vice president of public affairs knowing that she had run for governor of Georgia on a platform to defund Planned Parenthood; deceiving the public about the decision-making process that led to the defunding of Planned Parenthood; and misrepresenting to the public that reaction to the defunding decision, thus failing to disclose the true condition of the organization.) These failures were attributed to the leadership of Brinker and entire the board of directors. The petition, which had more than 2,000 signatures by the end of April 2012, not only called for the immediate resignations of Brinker and the board but also recommended a strong process for vetting replacement nominations that would involve all of Komen’s affiliates.

The managing director of the grants program, Mollie Williams, resigned in protest quickly after the board’s initial decision to defund Planned Parenthood. Not long after that, five executives from the national headquarters resigned, including the executive vice president and chief marketing officer, the vice president for global networks, the vice president of communications, a director for affiliate strategy and planning, and the organization’s chief fundraiser. Komen’s chairman of the board also stepped down as did Nancy Brinker’s son, Eric Brinker. Despite the shuffling, Nancy Brinker refused to leave her post and the Komen board cited full confidence in her leadership.

If Komen is really cleaning house, the organization would be wise to address the serious criticisms it has faced in the last several years, with transparency and accountability. It would benefit from charting a new direction to avoid conflicts of interest and threats to public health and to the public good. It would listen to the people on the ground who are working in their communities to fill gaps in care, include the affiliate organizations in decision making, change the conversation about breast cancer, and take action against the systemic factors that continue to impede progress in eradicating the epidemic.

Is the shuffle too little too late?

A version of this article originally appeared on the Pink Ribbon Blues Blog.

Gayle A. Sulik, Ph.D. is a medical sociologist and was a 2008 Fellow of the National Endowment for the Humanities for her research on breast cancer culture. She is author of Pink Ribbon Blues: How Breast Cancer Culture Undermines Women’s Health. You can read her previous OUPblog posts here and learn more on her website, where this article originally appeared.

View more about this book on the

Facts about the Silk Road

The “Silk Road” was a stretch of shifting, unmarked paths across massive expanses of deserts and mountains — not a real road at any point or time. Archeologists have found few ancient Silk Road bridges, gates, or paving stones like those along Rome’s Appian Way. In fact, the main defining features of the Silk Road are not man-made at all. They are best seen from the air — converging valleys, desert oases, and river chasms among towering mountain peaks. Although a physical road doesn’t exist, it is still a subject ripe for examination and study.

Foreign merchant in northern China, Tang Dynasty, 7th century. Musee Guimet, Paris. Photograph by PHG. Source: Wikimedia Commons

What kind of sources are there for the study of the Silk Road?What we know about the Silk Road isn’t mainly from ancient books or stone inscriptions, but from trash. The dry climate of the Taklamakan Desert has preserved different types of documents written on wood, paper, and cloth. Many of them survive because paper had a high value and was not thrown out. Craftsmen also used recycled paper to make paper shoes, statues, and other paper-maché objects to accompany the dead on their journey to the afterlife. The original documents have to be pieced together before anyone can make sense of them. Written in multiple languages and found in many different places, these documents contain an enormous amount of information about the Silk Road trade.

What goods were traded on the Silk Road?

Silk wasn’t the only good traded on these routes. Metals, spices, medicines, glass, leather goods, and paper all moved across Eurasia. Paper became the primary writing material for all of Eurasia, and surely had a far greater impact on human history than silk, which was used primarily for garments. Invented during the second century BCE, paper moved out of China, first into the Islamic world in the eighth century, and reached Europe via its Islamic portals in Sicily and Spain. People north of the Alps learned to make their own paper only in the late fourteenth century.

When was the term Silk Road coined?

The term “Silk Road” didn’t exist at the time of the Silk Road trade and there was no single route across Central Asia. The peoples living along different trade routes never referred to any particular route as the “Silk Road.” They referred to the different sections of the road as the “Road to Samarkand” (or whatever the next major city was). They did call the different routes around the Taklamakan either the “northern” or “southern” route.

In 1877, Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833-1905), a prominent geographer and the uncle of the World War I flying ace, produced a five-volume map of China. One map showed a single line connecting Europe and China, which he called the “Silk Road,” and the name stuck.

Which countries did the Silk Road connect?

The Silk Road connected China with the Iranian world, specifically the city of Samarkand (in today’s Uzbekistan) and the surrounding communities. This was the homeland of the Sogdians, who spoke an Iranian language called Sogdian, and many observed the teachings of the ancient Iranian teacher Zarathustra (ca. 1000 B.C.E., called Zoroaster in Greek), who taught that truth-telling was the paramount virtue. Some of the most exciting finds in the past decade have been the tombs of Sogdian leaders found in the main cities of interior China. The most common long-distance travelers, in fact, were the Sogdians who lived in and around modern-day Samarkand in today’s Uzbekistan.

Did the Silk Road connect China and Rome?

No. At least there was no direct traffic during the years of the Roman empire that we know of. Romans didn’t exchange their gold coins directly for Chinese silk. The earliest Roman gold coins found in China — so far only 48 gold coins (many are fakes) have been discovered after a century of intense investigations — are Byzantine solidus coins dated to the sixth century, several centuries after the capital shifted from Rome to Constantinople (modern Istanbul).

Valerie Hansen is Professor of History at Yale University. Her books include The Silk Road: A New History, The Open Empire: A History of China to 1600, Negotiating Daily Life in Traditional China: How Ordinary People Used Contracts, 600-1400, Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127-1276, and, with Kenneth R. Curtis, Voyages in World History.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Bob Chilcott and Charles Bennett on “The Angry Planet”

Composer Bob Chilcott and librettist Charles Bennett discuss their experiences of creating “The Angry Planet”, a large-scale cantata on the theme of the environment which was premiered at the 2012 Proms by the Bach Choir, the BBC Singers, the National Youth Choir of Great Britain, and London schoolchildren.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Listen to the premiere of “The Angry Planet” on BBC Proms.

Bob Chilcott has been involved with choral music all his life, first as a Chorister and then a Choral Scholar at King’s College, Cambridge. Later, he sang and composed music for 12 years with The King’s Singers. His experiences with that group, his passionate commitment to young and amateur choirs, and his profound belief that music can unite people, have inspired him both to compose full-time and, through proactive workshopping, to promote choral music worldwide. He is the composer of “The Angry Planet”. You can follow him on Twitter at @BobChilcott.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this sheet music on the

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition.

Angry Planet/BBC Proms image courtesy of BBC Proms.

The Doctrine of Discovery and Indigenous Peoples

Brasília - Líder da Nação Kayapó, Akyboro Kayapó, da Aldeia Moicaraku (PA), durante a 1ª Conferência Nacional dos Povos Indígenas. Valter Campanato/ABr, 2006. Creative Commons License.

Today is the United Nations International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. It is a day for action. An important part of this action must be to continue the work towards banishing racist international colonialism law including the Doctrine of Discovery. This Doctrine legitimated the notion that the first European country that discovered lands unknown to other Europeans could claim property and sovereign rights over Indigenous Peoples and their homelands. The Doctrine has been applied in countries around the world, including the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Brazil, and many African countries. All nations and peoples need to understand how this law developed; how it was used to denigrate Indigenous Peoples as human beings and then was used to steal their lands, assets, and rights; and how it has impacted Indigenous Peoples from the onset of colonization right up to 2012.This year, the Doctrine of Discovery was the declared theme of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues meetings in New York. Representatives from many countries spoke about the impacts of the Doctrine. At this event, we along with others, including high profile indigenous leaders, presented a paper and asked that the Permanent Forum adopt some initial steps to begin the process of repudiating and reversing the six hundred year old Doctrine of Discovery:

To adopt the Haudenosaunee, American Indian Law Alliance, and the Indigenous Law Institute conference room paper request for the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues to convene an Expert Group Meeting to create an international study of the Doctrine of Discovery and its effects on Indigenous Peoples, and to submit that study, along with recommendations, to the Permanent Forum in 2014.

To advocate that all states of the world adopt the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as binding national law.

To advocate that all states review their laws, regulations, and policies impacting Indigenous Peoples and to repeal laws, regulations, and policies which reflect the ethnocentric, feudal, and religious prejudices of the Doctrine of Discovery. Furthermore, states should undertake these reviews in full consultation with Indigenous Nations and Peoples and with their free, prior, and informed consent.

To call on all states to educate their citizens in school curricula and by other means about the true and complete history of colonization and the application of the international law Doctrine of Discovery.

To call on all churches to join with Indigenous Peoples in repudiating the Doctrine of Discovery and any role churches may have played in creating the Doctrine and in applying it against Indigenous Nations and Peoples. We recognize that several churches and church organizations have already done so: the Episcopal Church in 2009, the Anglican Church of Canada in 2010, and the World Council of Churches in 2012. We ask other churches to follow their lead.

Today offers an important opportunity to highlight the continued fictional nature of the Doctrine of Discovery especially to a wider global audience. For true, lasting reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples and colonial governments to occur, all citizens need to understand the complete history of colonization including the simple fact that in many countries Europeans arrived on lands already competently settled, owned, and governed by Indigenous Peoples.

Robert Miller is Professor of Law at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon. He serves as the chief justice for the Court of Appeals for the Grand Rone Community of Orego. He is an enrolled citizen of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma. Dr. Jacinta Ruru is Senior Lecturer at the University of Otago, and is of Ngati Raukawa (Waikato), Ngati Rangi and Pakeha descent. They are the authors of Discovering Indigenous Lands: The Doctrine of Discovery in the English Colonies with Larissa Behrendt and Tracey Lindberg.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

London’s Burning!

Today we are celebrating the UK publication of The Day Parliament Burned Down, in which the dramatic story of the nineteenth century national catastrophe is told for the first time. In this blog post, author Caroline Shenton presents the top ten London fires that have changed the face of the capital city.

On 16th October 2012, the anniversary of the day that Parliament burned down in 1834, we will be joining forces with Caroline Shenton to trace the gripping tale in real time. Follow us here: @parliamentburns.

By Caroline Shenton

1. Boudicca’s Revenge, 60-61

When Prasutagus of the Iceni tribe died, his queen Boudicca expected her daughters to become co-heirs to their East Anglian kingdom with the Emperor Nero. Instead she was flogged, the girls raped and their estates plundered. Boudicca rose in rebellion, teaming up with the neighbouring Trinovantes to lay waste to Roman settlements including Londinium — then a thriving, but not capital, town. Archaeological excavations in the City of London have revealed a layer of black ash over smashed pottery and roof tiles testifying to the utter destruction by fire and plunder which Boudicca inspired.

Boudicca. Photo by Kit36 via Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons License

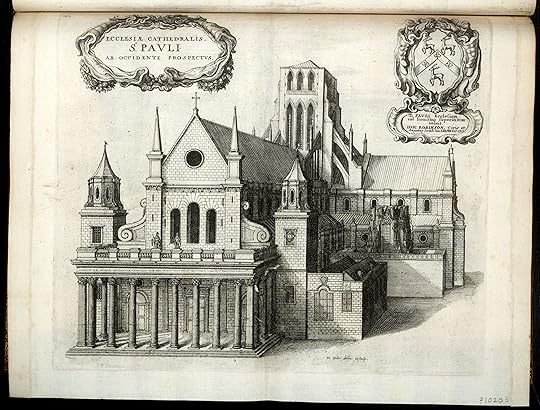

2. St Paul’s Cathedral, 1087

St Paul’s was founded in 604 by Bishop Mellitus of the East Saxons. It has been burnt four times over its 1400-year existence but has risen from the ashes each time: an enduring symbol of the City of London. The original wooden building was torched by Viking invaders in 962, then another fire led to a magnificent Norman rebuild in 1087. St Paul’s III was intended to be the largest and tallest church in Christendom and was finally consecrated in 1300. It was immortalised in the famous engravings by Wenceslas Hollar (1607-1677), showing the classical portico added by Inigo Jones in the seventeeth century.

Engraving of St Paul's Cathedral by Wenceslas Hollar. Source: University of Toronto Wenceslaus Hollar Digital Collection.

3. Savoy Palace, 1381

The London home of John of Gaunt, son of Edward III and Uncle of Richard II was burned to the ground by rebels during the Peasant’s Revolt. The gorgeous palace on the Strand was named after the original owner of the land in the 13th century, Peter of Savoy, and in 1889 the plot of land gave its name to the iconic Savoy hotel in London — the first to have electric lights, electric lifts, and hot and cold running water in all its bathrooms.

4. The Palace of Westminster, 1512

2012 marks the five hundredth anniversary of the major fire at the Palace of Westminster, which made Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon’s private apartments, known as the ‘Privy Palace’, uninhabitable. The royal family moved out of their principal London residence, and St Stephen’s Chapel of the ‘Great Palace’ was handed over to the House of Commons to use as its permanent home from 1548. The layout of the Chapel’s pews gave Parliament its characteristic seating arrangements, with government and opposition facing one another, seen on TVs the world over during Prime Minister’s Question Time.

5. Pudding Lane, 1666

“Tush, a woman might piss it out” said Thomas Bludworth, Mayor of London, when he first heard of the bakery accident which spread to become The Great Fire of London. After four days of inferno, 13,200 houses, 89 churches, 52 guildhalls had been destroyed and thousands were homeless. St Paul’s Cathedral was burnt to the ground along with 80% of the City, but the fire was an opportunity for architects such as Wren and Hawksmoor to create beautiful new baroque replacements. New regulations made domestic buildings more fireproof in the aftermath, and England became known for its fire-fighting innovations over the next hundred years.

The Great Fire of London by Thomas Willson via PD-Art

6. Whitehall Palace, 1698

The London palace favoured by the later Tudors and Stuarts was itself destroyed by fire in 1698, when a laundry maid left some linen to dry too close to a charcoal fire. But the name of the Palace still survives as the principal thoroughfare through the government quarter of London, leading from the Strand to Westminster. And ‘Whitehall’ has become a metonym for the British government and Civil Service.

7. The Gordon Riots, 1780

The mob violence that followed the 1778 Papists Act, legislation intended to relieve in a small way anti-Catholic discrimination in Britain, resulted in arson attacks on a wide range of targets. Catholic homes, foreign chapels, and continental embassies were fired, and then the rioters widened their attacks to the Bank of England and London’s prisons. After the Gordon Riots, the first calls were heard for a single metropolitan police force to keep order, which was finally formed in 1829, and whose officers are a familiar sight on the streets of London today.

8. The Houses of Parliament, 1834

This was the most significant fire between 1666 and the Blitz. It led to the creation of the world’s most famous gothic revival building, some great masterpieces by Turner, the recasting of the weights and measures of the kingdom and the Public Record Office. The massive blaze was fought by parish and private insurance companies with help from onlookers from all levels of society. Only a lucky change of wind and the bravery of the firemen saved Westminster Hall from destruction.

Parliament Burns: illustration of the UK Houses of Parliament on fire, 1834 - used with permission of Caroline Shenton

9. Tooley Street, 1861

When the Tooley Street jute, cotton and tea warehouses on the south bank of the Thames spontaneously combusted, they melted so much tallow inside that it ran into the river and blazed away on the surface for two weeks. Fire chief James Braidwood (who had helped to save Westminster Hall in 1834) lost his life when a wall collapsed and the authorities finally agreed to form a single, unified, public London Fire Brigade to protect the city in 1866.

10. The Blitz, 1940-1

The Luftwaffe’s aerial bombardment during the early years of World War II wreaked havoc and destruction on many London landmarks, changing the face of the East End and Docklands in particular. The Commons’ chamber took a direct hit in May 1941 and Westminster Hall’s roof was once again under threat from fire as in 1834. Christopher Wren’s new St Paul’s remained triumphantly intact in one of the most evocative images of the City on fire in 1940. The regeneration of the Docklands and the London 2012 developments at Stratford have in recent years finally revived areas that have lain derelict since that time.

Caroline Shenton is Director of the Parliamentary Archives at Westminster, and author of The Day Parliament Burned Down. You can follow Caroline on Twitter @dustshoveller, and read her blog about Parliamentary history.

Don’t forget that on 16th October 2012, the anniversary of the fire at the UK Houses of Parliament will be reconstructed in real time on Twitter: @parliamentburns.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 8, 2012

Edinburgh International Book Festival: Frank Close and Peter Higgs

Today the world famous Edinburgh International Festival kicks off, beginning three weeks of the best the arts world has to offer. The Fringe Festival has already begun in earnest with countless alternative, weird, and wacky events happening all over the city. The icing on the cake (for us at least) is the Edinburgh International Book Festival, which gets underway on Saturday. Throughout the Book Festival we’ll be bringing you sneak peeks of our authors’ talks and backstage debriefs so that, even if you can’t make it to Edinburgh this year, you won’t miss out on all the action.

First up: Frank Close prepares to interview Professor Peter Higgs in an event on Monday 13 August 2012. This will be the first time the pair will appear together at a public event since the announcement of the breakthrough boson discovery at the Large Hadron Collider.

By Frank Close

When I interviewed Peter Higgs at the Borders Book Festival in Melrose in June, he had been waiting 48 years to see if his eponymous boson exists. On July 4 CERN announced the discovery of what looks very much like the real thing. On August 13 I am sharing the stage with Peter again, this time in Edinburgh. We shall be discussing his boson and my book The Infinity Puzzle, which relates the marathon quest to find it. How has his life changed?

A century ago, Ernest Rutherford discovered the atomic nucleus. He did so with a piece of apparatus that sat on the top of a small bench, and shared in the experiments with two collaborators, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden. Half a century later, science was beginning to identify how matter was created in the aftermath of the big bang, 13.6 billion years ago. But why was the debris of that singular event not rushing hither and thither at the speed of light? How did structure emerge, such as atoms, which lead to molecules and even life?

In the space of a few months during the summer of 1964 Peter Higgs, and five others independently, discovered a mathematical answer to that question. That was itself a triumph, as any novel theory had to be consistent with the great pillars of physical wisdom: Einstein’s relativity theory and the laws of quantum mechanics. The theory of the “Gang of Six,” as they have become known, passed all the tests, but one strand remained. How could one make an experiment to verify if the theory was what nature actually uses, and not simply a piece of clever mathematics?

Peter Higgs uniquely answered that, with his insight that there should exist a massive particle, known in the trade as a “boson,” which has in consequence become known as the Higgs boson. The particle is unstable, so if you can produce many examples of it, and record what happens when they decay, you can hopefully prove the theory to be correct.

Higgs bosons were common in the first moments after the big bang, but have merged into an ubiquitous form of ether subsequently. The only effect of this all-pervading field, in theory, is that it gives fundamental particles mass, which leads to structure and form in bulk matter. However, if one could in a small region of space simulate the intense heat of the new-born universe, one might hope to make Higgs bosons bubble into view. To achieve such conditions, the Large Hadron Collider was built at CERN. Quite a contrast to Rutherford’s homely experiment, the LHC is 27 kilometres in circumference, the Higgs boson is detected by banks of electronic equipment the size of a battleship, and teams of thousands – engineers, physicists and computer scientists from around the world — collaborate to make it all possible.

The LHC is designed to recreate the early universe and reveal many profound truths, not just the Higgs boson. Nonetheless, many incorrectly associate it, including its total cost of billions of euros, with the Higgs alone.

In June I asked Peter: “If after all this effort you discovered a mistake in your calculations…” The question was left incomplete, as the audience laughed — nervously? In any event, Peter had no need to answer as on July 4, after 48 years, the wait was over. Next week I shall be asking him, like some interviewer at the Olympics with a gold medalist: “How does it feel?”

Perhaps more seriously, questions might include: Is it all signed sealed and delivered? Have you celebrated yet (and how)? What’s the future for the LHC? What’s the future for Peter Higgs? Or some other questions that you would like to pose… Post your suggested questions in the comments box below but be quick, I am on stage with Peter Higgs at noon, British Summer Time, on Monday 13 August 2012.

Frank Close is a particle physicist, author, and speaker. He is Professor of Physics at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford. He is the author of several books, including The Infinity Puzzle, Neutrino, Nothing: A Very Short Introduction, Particle Physics: A Very Short Introduction, and Antimatter. Close was formerly vice president of the British Association for Advancement of Science, Head of the Theoretical Physics Division at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and Head of Communications and Public Education at CERN. Read more of what Frank Close has to say about neutrinos here and here. Read Frank’s reflections on the Nobel Prize nominations for the 4 July discovery.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Logo courtesy of Edinburgh International Book Festival

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers