Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1031

August 20, 2012

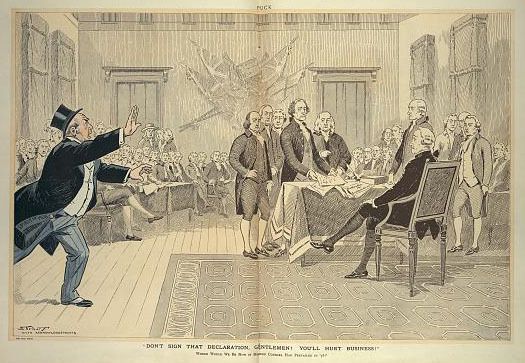

The Declaration of Independence and campaign finance reform

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for the next four weeks in anticipation of the Republican and Democratic National Conventions, and American presidential race. This week our authors are tackling the issue of money and politics.

By Alexander Tsesis

The Supreme Court’s recent equation of personal and corporate campaign contributions has vastly increased corporate and super PAC donations during this election year. The Court’s premise that corporations deserve the same right to political speech as ordinary people is a modernist interpretation that would have sounded completely foreign to the framers of the Declaration of Independence. It is particularly curious that self-proclaimed originalists — Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas — joined judicial opinions striking key provisions of the bipartisan McCain/Feingold Campaign Finance Reform Act and the Montana ban on corporate campaign spending. Political speech at the time of independence only applied to natural persons and had nothing to do with corporations. Indeed, in 1776 corporations were entities operating through personal charters granted by legislatures, not the general incorporated entities of today that shield shareholders and boards of directors from liability.

At the tail end of this year’s term, the Supreme Court reconfirmed its earlier holding in the well know Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case, which found that any campaign finance laws that treat corporations and individuals differently violate the First Amendment. These judicial opinions expressed a view that was incompatible with principles that informed the framers of the Declaration of Independence.

To many political insiders, the outcome of Citizens United was somewhat surprising because, unlike voters, corporations are only metaphorically persons; in reality, they are artificial entities that are governed by special laws. To search for the core value of political speech we need look no further than the Declaration of Independence. The founding generation insisted that government be based on the consent of the people. They rebelled for lack of representation in the British Parliament and determined to establish a nation where voting would be an inalienable right of qualified citizens. But corporations have no inalienable rights. The Declaration’s famous assertion that “all men are created equal… [and] they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights” simply doesn’t apply to entities with “perpetual life” that are created by articles of incorporation. As a creature that owes its existence, form, and structure to the state, no corporation has the inalienable rights that informed the Declaration of Independence’s framers’ notion of political community. Having no natural rights — but only positive regulations on creation, operation, and dissolution — corporations’ communications can be restricted differently than the speech of ordinary people.

"Don't sign that declaration, gentlemen! You'll hurt business!" by S. D. Ehrhart, Puck, 1908. Source: Library of Congress.

The Declaration of Independence insisted that ordinary people are the true sovereigns of a nation that is governed by principles and institutions that further “safety and happiness.” Elections are critical to achieving those ends. In many of the Declaration’s paragraphs, the framers renounced the British government for being unresponsive to the people and established the enduring principle that our country enjoy the benefits of popular sovereignty. Unchecked corporate expenditures on behalf of favored candidates can be used to curry political favors that benefits a small sector of the population but harm ordinary Americans already reeling from the economic hardships.

An essential feature of the newly founded nation was, and continues to be, government by consent of the people. While foreign citizens have no right to participate in representative elections, a corporation whose board of directors may be composed of foreigners with no legal status in the United States, can give freely to politicians’ even though they cannot vote in any election.

At the oral argument to Citizens United, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked rhetorically why Congress could not set different campaign finance standards for corporations and ordinary people given that, in her words, “[a] corporation, after all, is not endowed by its creator with inalienable rights.” She received no reply from the attorney, and her insight into the connection between the Declaration’s political ideals and constitutional interpretation didn’t enter into the majority or dissenting opinions.

Neglect of the Declaration of Independence is unfortunate. The document’s statement of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” as Justice William O. Douglas expounded, have “found specific definition in the Constitution itself, including of course freedom of expression.” The existence of an intrinsic right of citizens to pick leaders is presumed in the Declaration of Independence, but to this day corporate entities do not have voting privileges in general elections; and we can only hope that won’t change. In Citizens United and the more recent case striking Montana’s corporate finance law, the Court might have done well to follow its own assertion, made more than a hundred years ago, that “it is always safe to read the letter of the Constitution in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence.” That document speaks to us today as it did to the framers, but its protection of inalienable rights extends to natural persons not corporations.

Alexander Tsesis is Associate Professor of Law at the Loyola University, School of Law-Chicago. He is the author of For Liberty and Equality: The Life and Times of the Declaration of Independence; We Shall Overcome: A History of Civil Rights and the Law; The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom; and Destructive Messages: How Hate Speech Paves the Way for Harmful Social Movements.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Waking the Giant at Edinburgh International Book Festival

The world famous Edinburgh International Festival has kicked off, beginning three weeks of the best the arts world has to offer. The Fringe Festival has countless alternative, weird, and wacky events happening all over the city, and the Edinburgh International Book Festival is underway. Throughout the Book Festival we’ll be bringing you sneak peeks of our authors’ talks and backstage debriefs so that, even if you can’t make it to Edinburgh this year, you won’t miss out on all the action.

By Bill McGuire

If it’s August, it must be Edinburgh. Doing the rounds of the UK’s book festivals is always great fun, but the Edinburgh International Book Festival is almost inevitably the annual highlight. While the book festival is exciting in its own right, this is in large part because the Edinburgh Festival and Fringe are in full spate, packing this great city with visitors from far and wide, and with acts and events that boggle even the most unflappable mind. Where else can you stroll down a street of 10-storey high rises more than 300 years old to watch a unicyclist juggling blindfolded or an entertainer whose speciality is popping his joints and rearranging his limbs into unlikely and somewhat unsettling configurations? Away from the Royal Mile, however, the book festival is located in the calmer setting of Charlotte Square, in the so-called ‘new town’, where it is the English language and not elements of the human body that are manipulated.

Bill and Fraser at EIBF (snapshot by editor Nicola)

My visit to the festival this year formed part of a tour to linked to my new book, Waking the Giant, which has previously taken me to London, Keswick, Aberystwyth, Liverpool, Hay-on-Wye, and coincidentally Edinburgh (for the Science Festival earlier in the year). This time, with 8-year old son, Fraser, in tow, I was booked to do a joint gig with lauded environmental journalist Fred Pearce, a stalwart contributor to the Guardian and New Scientist, and prolific author. Putting the two of us together was a smart move, given that we have new books out that address different disturbing environmental issues. I have a feeling, however, that the combination might have made for a somewhat depressing hour for an audience who, nevertheless, looked pretty chipper at the end. While Fred examined the devastating consequences for indigenous populations of the wholesale buying up of prime African farmland by foreign states, my focus was how climate change has before and may well again trigger earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions.

If this is the first time you have heard about this possibility, your reaction will probably be the same as most people’s: “He must be mad.” Surprisingly, however, the idea isn’t even new and we have a huge amount of evidence for past changes in our world’s climate eliciting a potentially hazardous response from the solid Earth. “But how can this possibly be the case?” I hear you say. Surely climate change is confined to the atmosphere, with perhaps the oceans involved too. What has the ground we walk and live upon got to do with it? The best way to find out is to head back to the transition from icehouse to greenhouse that followed the end of the last ice age. As the world warmed dramatically between about 18,000 and 5,000 years ago, rapid melting of the great continental ice sheets that covered much of Europe and North America resulted in the decanting of a staggering 52 million cubic kilometres of water from the land and into the oceans.

At high latitudes, particularly across Scandinavia and Canada, the removal of the colossal weight of an icy carapace up to three km thick liberated active faults beneath, which ruptured violently to release the accumulated strain of many thousands of years of imprisonment in the form of huge earthquakes. In northern Norway and Sweden, magnitude eight quakes as large as those we see today within the Pacific ‘Ring of Fire’ shook the region. Around 8,000 years ago, one of these great seismic events seems to have provided the trigger for the Storegga Slide — a monumental submarine landslide that cascaded off the Norwegian continental shelf and into the North Atlantic, spawning a giant tsunami that battered the region’s coastlines, including those of the Shetland Isles and mainland Scotland. As the one km-thick ice cover across Iceland progressively vanished, molten magma incarcerated beneath was able to force its way to the surface, leading to a ‘volcano storm’ that saw eruptive activity climb by more than 50 times.

Even far from the poles the Earth shifted. As meltwater from the vanishing ice sheets poured into the ocean basins, so water levels rose by 130m; the added weight bent ocean margins across the planet. In response, magma was squeezed upwards to explode forth from the many volcanoes that occupy coastal and island locations, while faults such as California’s San Andreas, reacted by rupturing more frequently to produce earthquakes.

Well, this all sounds pretty reasonable, but what has it to do with us right now, you might ask? Quite a bit in fact. Worryingly, climate change due to human activities is driving the loss of ice in Alaska that is already garnering a rise in earthquake activity, while thawing permafrost means that giant landslides are becoming increasingly common in mountainous regions around the world. So far there has been no global burst of volcanic or seismic activity as sea levels driven by contemporary global warming continue to climb, but if we continue to pump out greenhouse gases at current rates, it might only be a matter of time before the restless giant beneath our feet wakes once again. Be afraid. Be very afraid!

Bill McGuire is an academic, science writer, and broadcaster. He is currently Professor of Geophysical and Climate Hazards at UCL. Bill was a member of the UK Government Natural Hazard Working Group established in January 2005, in the wake of the Indian Ocean tsunami, and in 2010 a member of the Science Advisory Group in Emergencies (SAGE) addressing the Icelandic volcanic ash problem. He was also a contributing author on the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC) report on extreme events. His books include Waking the Giant: How a changing climate triggers earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes, Surviving Armageddon: Solutions for a Threatened Planet, and Seven Years to Save the Planet. Read his previous blog posts: “Climate change: causing volcanoes to go pop” and “Will climate change cause earthquakes?”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Logo courtesy of Edinburgh International Book Festival

August 19, 2012

A Spice Girl Symphony: The Olympic Closing Ceremony

The 2012 Olympic games concluded on Sunday 12 August with choreographer Kim Gavin’s musical extravaganza. As with ’s opening ceremony, Gavin was intent on impressing his vision of British music to the world. To underscore its significance, he titled the closing “A Symphony of British Music.” This title was a peculiar choice considering that classical historical musicology considers the “symphony” as a specific genre of classical music: a serious multi-movement work composed by a renowned composer, and performed by an orchestra.

No, Gavin’s extravaganza was not a “symphony” in the classical sense, but more a musical “revue.” But by tagging the closing ceremonies as a “symphony,” Gavin is participating in the postmodern agenda of flattening the musical register — the traditional defined hierarchies that distinguish “high art” from “low art.” On Sunday, Gavin leveled the musical playing field by elevating British pop and rock music to “symphonic” status. This was particularly notable by the reverence shown to the Beatles, John Lennon in particular (McCartney was so honored in Boyle’s opening show). The changing status of pop music was also shown in the performance of the teen idol group Take That during the extinguishing of the Olympic flame, a ceremonial moment traditionally reserved for solemn, orchestral-based music. (By the way, Take That is one of Gavin’s employers for choreography projects.)

Though rhapsodic rather than symphonic, there were two musical threads that shaped the closing ceremony. First, there was the veneration of ‘classic’ British pop artists, performed either through pre-recordings by the artists themselves, or covered by lesser-known (at least by American TV standards) contemporary artists. Of these classic artists, the Beatles loomed large. John Lennon was honored by the Liverpool Philharmonic Youth Choir and Liverpool Signing Choir’s singing of “Imagine”, along with a jumbo-tron video of Lennon himself.

“I am the Walrus” was sung (or more likely lip-synched) by comedy actor Russell Brand. George Harrison’s “Here Comes the Sun” was also performed, but didn’t make it on air in the NBC broadcast.

Other ‘classical’ British musical luminaries were featured, notably David Bowie, in a brief pre-recorded collage that introduced the British fashion industry. The Who (who actually appeared later), Pink Floyd, and The Bee Gees were all covered by younger artists. The Kaiser Chiefs sang “Pinball Wizard”; Ed Sheeran with Nick Mason, Mike Rutherford, and Richard Jones covered Pink Floyd; and Fatboy Slim, Jessie J, Tinie Tempah, and Taio Cruz covered the Bee Gees. Queen performed with band members Roger Taylor and Brian May, along with the virtual presence of the late Freddie Mercury on the big screen.

The other structural thread of the show consisted of artists who performed their own works, either in a live TV-show-like direct address performance or through fanciful vignettes. These artists are perhaps lesser known than their classical counterparts, but have fan bases, longevity, and familiarity with the TV audience. In this group, we saw and heard Emeli Sandé, One Direction, The Pet Shop Boys (wearing conical hats while riding bicycles), Annie Lennox (on a giant ship), George Michael, Beady Eye, and of course, the Spice Girls, which NBC commentators thought the highlight of the show.

Classical music did make an appearance with Julian Lloyd Webber playing Elgar’s “Salut d’amour” for cello, although he was drowned out by actor ’s Churchill monologue. The British choral tradition reprised its role from the opening ceremonies through the youth choir singing Lennon (mentioned above), and the London Welsh Male Voice Choir and London Welsh Rugby Club Choir — both top-notch Welsh male choruses — singing of the Olympic anthem.

The one group that performs actual “symphonies” — the London Philharmonic Orchestra — was also present, but was mostly lost in the circus-like atmosphere of the finale.

So, Gavin picked up where Boyle left off, with his veneration and valorization of British rock music of the past fifty years. For many in the audience this is the new British symphony, Spice Girls and all.

Parting shots

Speaking of the London Philharmonic, it is reported that members of the orchestra recorded the national anthems for all 205 participating nations in the Olympic games in a little under 52 hours of studio time.

Click here to view the embedded video.

After the “handoff” of the Olympic flag to Brazil, the Brazilians performed a well-choreographed piece to the famous “Aria” to Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5 by native composer Heitor Villa-Lobos.

NBC edited out performances by at least two notable Britpop artists: Muse’s Matt Bellamy and The Kinks’ Ray Davies, and the broadcast of The Who’s performance at the closing party was delayed by NBC’s promotion of a sitcom about an animal hospital. All of these decisions led to many complaints to the network.

Ron Rodman is Dye Family Professor of Music at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. He is the author of Tuning In: American Television Music, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. Read his previous blog posts “Music and the Olympic Opening Ceremony: Pageantry and Pastiche” and “Music and the Olympics: A Tale of Two Networks.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

World Humanitarian Day

Cynical observers, of the kind who always scoff at the UN and its aims, may regard World Humanitarian Day (19 August) as just another high-minded but meaningless annual event. Yet the day has a very specific origin, which should remind us that humanitarianism is not just a fine principle but a hard struggle against the opposing forces of violence and war.

Cynical observers, of the kind who always scoff at the UN and its aims, may regard World Humanitarian Day (19 August) as just another high-minded but meaningless annual event. Yet the day has a very specific origin, which should remind us that humanitarianism is not just a fine principle but a hard struggle against the opposing forces of violence and war.

The event was established by the UN General Assembly in December 2008, after several years of diplomatic effort, as a tribute to all those who have risked and sometimes lost their lives to help the victims of inequality and conflict, and as an encouragement for those out in the field who continue to work for this cause.

The actual day commemorates the death of the senior official Sérgio Vieira de Mello and 20 other UN colleagues who were killed when the UN office in Baghdad was blown up by a terrorist bomb. At one level we may deplore the extremist violence targeted against humanitarian workers who were trying to help restore Iraqi civilian society. Yet the real lesson to be drawn goes much deeper.

The Iraq War of March 2003 was, in the simple but accurate description by then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, an “illegal war.” Annan had warned the US and its allies a week before the invasion began that it would be a breach of the charter. It was also a war which, as its critics also warned in advance, was likely to increase rather than decrease instability in the region and of course within Iraq itself.

It quickly became apparent that the invasion, while successful in overthrowing Saddam Hussein, had stirred up an internal storm of protest and violence. Not for the first time, the UN was then called in to tackle the problems created or exacerbated by the unilateral action of some of its member states. De Mello, who had been in Iraq since May, listened to scores of complaints from Iraqis who lamented that their country had lost control of its own sovereignty, that living conditions were getting worse, not better, and that the security situation was becoming “precarious… particularly in Baghdad.”

The UN had already been struggling for more than ten years, since the Gulf War of 1991, to tackle an on-going humanitarian crisis in Iraq. Their workers were frustrated not only by Saddam Hussein, but also by the harsh sanctions on which the US and its allies had insisted and which hit the innocent Iraqi civilians rather than the regime. In summer 2003, though with many misgivings, Kofi Annan and his officials decided to re-commit the UN to Iraq. The resolution authorising the UN Assistance Mission (UNAMI) was passed on 14 August, just five days before the fatal bomb.

The story of Iraq illustrates a wider problem with international humanitarian action which often finds itself invoked by forces which at the same time are undermining it. Afghanistan is another current example, where the amount of non-military aid given from 2001 to 2010 has been only one-twelfth of the total of military aid.

It is a truism that we live in a globalised world, but world leaders need to understand that this also means sharing a global responsibility to tackle poverty and inequality. Development and aid should not merely be used to patch up the wounds left by conflict and war: they should move to the top of policy priorities to prevent those wounds being created.

As long ago as 1919, when the International Labour Organisation was set up by the League of Nations, it was explicitly recognised that — as in the opening words of its constitution — “universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based on social justice.” The same spirit inspired the establishment of the United Nations whose agencies have been seen for decades as bearing primary responsibility for addressing poverty and inequality, and tackling disasters whether natural or man-made. The UN system, as its passionate advocate the late Erskine Childers argued (in his Challenges to the United Nations, 1994), “has accomplished vastly more than (we) have ever been told about” and we should give it the means to do even more.

John Gittings worked at The Guardian (UK) for twenty years as assistant foreign editor and chief foreign leader-writer. He is on the editorial team of the new Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace (2010) and is author of The Glorious Art of Peace: from the Iliad to Iraq (2012). Read Gittings on the real lessons of the Cuban Cold War crisis.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

World Humanitarian Day pin image via WHD

August 18, 2012

Grammar sticklers may have OCD

It used to be we thought that people who went around correcting other people’s grammar were just plain annoying. Now there’s evidence they are actually ill, suffering from a type of obsessive-compulsive disorder/oppositional defiant disorder (OCD/ODD). Researchers are calling it Grammatical Pedantry Syndrome, or GPS.

Maybe you’ve heard of the grammar gene — its technical name is the FOXP2 gene — which may be responsible for a variety of grammatical ills, such as the inability to construct compound/complex sentences or to effectively deploy the passive voice. Now there’s evidence that a variant of that gene, FOXP2.1, may actually cause us to obsessively correct other people’s grammar, or should that be, to correct their grammar obsessively? The discovery of this gene, alongside new evidence from fMRI scans of brains exposed to real-time grammatical errors, has led some scientists to predict that soon we may be able to find a cure for GPS, for many sufferers a debilitating, off-putting, sociopathic syndrome.

At least that’s the conclusion of two researchers writing in the current issue of the Journal of Syntactic Cognition. A team led by L. Malevich and H. D. Lo studied the fMRIs of self-identified grammar sticklers as they were exposed to a variety of solecisms ranging from split infinitives and sentence-final prepositions to phrases like between you and I and apple’s $2.49 a bag.

The fMRIs of the language purists showed markers of brain activity also commonly observed in OCD/ODD patients, along with several surprises: Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas, the parts of the brain associated with language, were actually smaller, or exhibited reduced activity, in grammar sticklers and language purists, than in normal subjects. DNA analysis showed they also had a higher likelihood of having the FOXP2.1 gene than the general population (Len Malevich, Hi Ding Lo, et al., “Correlation of instances of grammatical pedantry with the expression and suppression of an underlying FOXP2.1 gene” JSynCog 34.3: 1135-39).

[image error]

fMRI scans of normal and GPS brains, from the Journal of Syntactic Cognition, used by permission.

Malevich and Lo found, paradoxically, that compulsive correctors of other people’s grammar had smaller Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, or their brain language centers exhibited reduced activity when shown grammatical errors, compared with a control group having a more relaxed attitude toward language correctness (see image above). In contrast, nonpurists, lacking FOXP2.1, showed increased activity in those same cerebro-cortical regions, and a significant number of control-group participants showed particularly strong fMRI evidence of language activity when texting. “We expected just the opposite,” Malevich told reporters at last month’s annual Symposium on Syntactic Therapy in Toronto. “After all, texting is usually seen as signaling decreased morphosyntactic competence. We don’t know what this data means.” And then he added, “or is it, what these data mean?”

According to Malevich, identification of an underlying physiological basis for this alienating disorder could eventually lead to curative stem-cell treatment plus, in the near term, the development of pharmacological palliatives. There’s even a push to add GPS to the DSM-5, the latest edition of the standard catalogue of psychological disorders, scheduled for publication in 2013.

Malevich and Lo, as well as other cognitive syntacticians, are convinced that classifying linguistic purists and grammatical pedants as obsessive-compulsive could go a long way toward explaining why a group of people so convinced that they are right can be regarded by the rest of us as, well, a bit off. Interpreting the data, Malevich concludes, “grammar rules feed the desire of OCD sufferers to impose normative order on language that seems to them to be out of control,” and those exhibiting oppositional defiant disorder “revel in their ability to flout social conventions and correct other people’s language even when it is perceived to be rude or insensitive to do so.” “Or,” he asked, “are they flaunting those conventions?”

On a more positive note, the authors suggest that strict adherence to grammar rules is a safety valve for GPS sufferers, helping them avoid full-blown OCD/ODD episodes: “If you mark out sentence-final prepositions with a red pen and regularly change the passive voice to active, that’s more socially acceptable than repetitive hand washing, the incessant touching of doorknobs and parking meters, or refusing to step on sidewalk cracks.”

Pathologizing correctness in grammar may not win over all of those who are symptomatic. After all, the purists are convinced that they’re the ones rooting out the language ills of others. Bob Lowth, founder and president of the Society for the Propagation of Pure English (SPoPE), strongly objects to this kind of medicalization of grammatical correction. “It’s bad English that’s sick, not correcting it,” Lowth complained. “I suppose the next thing is that workers will want health insurance coverage for their misplaced modifiers.”

But with the shuttering in recent years of many of our mental health facilities, and an increased focus on patients’ rights, more and more compulsive grammar correctors are roaming our streets unchecked. GPS goes a long way towards finding, explaining, and helping us deal with, their obsession with enforcing on the hapless public an idiosyncratic and often undertheorized idea of what’s right or wrong in speech and writing. If defining this kind of intrusive purism as a psychological syndrome helps us find a cure, then ultimately both society, and language itself, stands to benefit. Or is it that they stand to benefit?

[Editor's Note: This is a joke article. However, if you're worried you're suffering from GPS, Dr. Grammar recommends why we mis-read for treatment.]

Dennis Baron is Professor of English and Linguistics at the University of Illinois. His book, A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution, looks at the evolution of communication technology, from pencils to pixels. You can view his previous OUPblog posts here or read more on his personal site, The Web of Language, where this article originally appeared. Until next time, keep up with Professor Baron on Twitter: @DrGrammar.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only dictionary, lexicography, language, etymology, and word articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

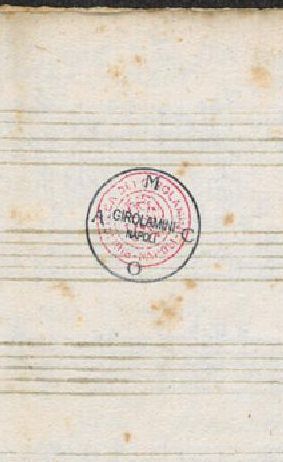

The difficulty of insider book theft

On Sunday, the New York Times reported on the wholesale looting of the prestigious Girolamini Library in Naples, Italy, by its director, Marino Massimo de Caro. He seems to have treated the place as his own personal collection, stealing and selling hundreds — maybe thousands — of rare and antiquarian books during his 11 month tenure. This has provoked the normal amount of head-shaking and hand-wringing. But what is most striking — aside from the embarrassing appointment of the unqualified de Caro to the job in the first place — is how terrible a thief he was.

On Sunday, the New York Times reported on the wholesale looting of the prestigious Girolamini Library in Naples, Italy, by its director, Marino Massimo de Caro. He seems to have treated the place as his own personal collection, stealing and selling hundreds — maybe thousands — of rare and antiquarian books during his 11 month tenure. This has provoked the normal amount of head-shaking and hand-wringing. But what is most striking — aside from the embarrassing appointment of the unqualified de Caro to the job in the first place — is how terrible a thief he was.

For an insider, stealing rare books, maps and documents is easy. It takes no talent and very little planning. But turning those stolen items into cash while also staying out of jail requires skill, and a great deal of effort. De Caro, like many insiders before him, seems not to have properly thought this through.

The first step in the successful insider heist is to identify items unlikely to be either missed by the institution or recognized by buyers as stolen. For the same reason that stealing the Mona Lisa is a bad idea, taking the most famous or in-demand items in a library or archive is ill-advised. They’ll be likely recognized as missing and, in any event, will raise suspicions in anyone knowledgeable enough to pay full price for them.

Witness Rebecca Streeter-Chen, curator at the Rockland County Historical Society, who stole the jewel in her institution’s crown — a $60,000 Tanner Atlas. It was quickly recognized as missing, the requisite warnings sent out and Streeter-Chen clapped in chrome mere hours after she offered it for sale to a Philadelphia antiquarian map dealer. On the other hand, Daniel Lorello, archivist at the New York State Library, had a long career stealing and selling historical documents primarily because he focused on low-value items of the sort he referred to as “shit.” He assumed these things would be neither missed nor recognized when put up for sale — and he was right about that. But he eventually went up-market and was caught.

The more theoretical value an item has (think Shakespeare, Gutenberg, Caxton, Audubon, etc.) the less actual value it has when stolen.

The second step is a careful scrubbing of the catalogue record. This is important for two reasons. First, by getting rid of an item’s catalogue entry, it is more difficult to detect that it has been stolen. Not only will patrons be unable to request an item for which no record exists — thereby postponing discovery — but even if the item is known to be affiliated with the institution, it is difficult to prove in a court of law without an actual record. Unfortunately for would-be thieves, whose track-covering often ends with destroying a catalogue entry, item records sometimes show up in the darndest places.

Skeet Willingham, head of Special Collections at the University of Georgia, did a fairly comprehensive job of destroying evidence of his serial thefts. This included, he thought, any indication at all that UGA owned an eight-volume set of floral prints by 19th century artist Pierre-Joseph Redoute. Unbeknownst to him, a photocopy of the library’s catalog card had been made for, and stored at, the university’s science library as a cross-reference. Lester Weber, Director of Archives at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia, did a similar job of destroying the records of the items he stole. That is, he missed some. In one case, a collection he pilfered had been, before he arrived at the museum, on loan. That meant a separate set of records he neither knew about nor had access to.

But for would-be thieves it is even worse than that. The record of every potential stolen item needs to not only be purged from the system — and any various card-catalog hard copies tracked down and destroyed — but it must never have been consulted by a researcher or author and made its way, via citation, into a book or article. David Breithaupt, night supervisor at Kenyon College’s Olin Library, was outed as a thief when he tried to sell on eBay a Flannery O’Connor letter that appears in the reference book American Literary Manuscripts. A savvy Georgia librarian made the connection.

The third step, finding a market, might be trickiest of all. While eBay seems to have gone a long way toward mitigating this problem, it has proven a double-edged sword. Too many knowledgeable collectors or nosy librarians have spotted something amiss, and placed a phone call. So the savvy thief, especially with big ticket items, eschews the auction site. Not that approaching dealers and auction houses is less risky. They do research, too, before handling expensive items, a lesson Edward Renehan, director of the Theodore Roosevelt Association, found out when he tried to sell important presidential letters he’d stolen.

So a discreet, trustworthy fence is essential. And while many antiquarian booksellers have served this role — witting or unwitting — over the years, many more have proven to be valuable allies in the fight against library and archive theft. If staying out of jail is the goal, random queries to members of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America is a bad idea. Unless an insider thief is very lucky, it will take years to cultivate the sorts of contacts needed to safely sell stolen material without risking jail.

In short, getting away with it has never been more difficult. More importantly, the criminal penalties are as harsh and consistently imposed as they’ve ever been. So, to the de Caro’s of the world, who find themselves in possession of keys to the vault, I say this: Congratulations, you’ve cleared the shortest hurdle. If you want to stay out of jail, you have years of work ahead of you, and many more yet of looking over your shoulder.

Travis McDade is Curator of Law Rare Books at the University of Illinois College of Law. He is the author of The Book Thief: The True Crimes of Daniel Spiegelman and a book on a Depression-era book theft ring operating out of Manhattan forthcoming from Oxford University Press in spring 2013. He teaches a class called “Rare Books, Crime & Punishment.” Read his previous blog post: “Barry Landau and the grim decade of archives theft.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Headline image via spxChrome, iStockphoto. Stamp of the Biblioteca dei Girolamini via Wikimedia Commons.

August 17, 2012

Shark sensory mechanisms

Sharks always draw a crowd. We have a macabre fascination with these creatures because of their commanding presence and predatory lifestyle. Such a lifestyle demands high quality sensory systems, something sharks have had millions of years to develop.

The class Chondrichthyes arose and separated from other fish in the Silurian, over 400 million years ago. It includes all fish having a cartilaginous skeleton. Evolutionarily, these fish followed a different path by separating from bony fish and evolving into two different groups: elasmobranchs (including modern sharks, skates, and rays) and a much smaller group of fish called holocephalans (including elephant fishes and chimeras).

Some of the elasmobranchs, and in particular the sharks, have perhaps the best olfactory system of any group on the planet. Hammerhead sharks are particularly interesting in this regard; they have one of the largest olfactory bulb (collection of sensory cells for smelling) to brain ratio of any species and must rely heavily upon this sense. The scalloped hammerhead has an olfactory bulb that occupies 7% of its total brain mass as compared to approximately 3% for sharks in other families. Additionally, much of the forebrain in these sharks is devoted to the intrepretion of odors.

The unusual flattened head of hammerhead sharks, termed a “cephalofoil,” probably evolved for improved sensory perception although it isn’t clear for which sense. This unusual cephalofoil design allows for improved stereo-olfaction. Hammerheads have special grooves leading to the wide-spaced nares (essentially the nasal passages at the distal tips of the cephalofoil), which lead to enormous olfactory rosettes. Thus these sharks have true stereo-olfaction. These olfactory abilities, almost certainly lead this cartilaginous fish to its prey since hammerheads can detect one part per 25 million of blood in seawater. Other species of sharks have an excellent sense of smell, but hammerheads have to be among the best.

The cephalofoil of the hammerhead also houses electroreceptors, called the “ampullae of Lorenzini,” unique to elasmobranchs and the chimera. This unique organ senses low-level electric current in water with sampling done via pores distributed along the dorsal and ventral surface of the cephalofoil. The utility of the electrosensory abilities is poorly understood although prey location and migration have been proposed. While scything its way through the water, a hammerhead processes odors, weak electric currents, and visual inputs, although it is not clear how these signals are reconciled and integrated.

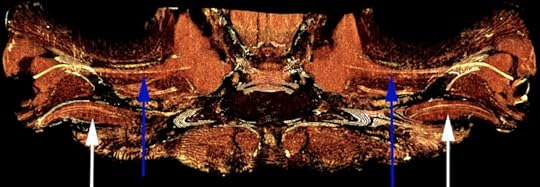

A Sphyrna lewini. A.Computerized Tomography (CT) scan of the head of S. lewini reveals large olfactory bulbs (white arrows) and long optic nerves (Blue arrows). Soft tissue is false colored to be a burgundy and the cartilage has been colored a light yellow. Image by J. Anthony Seibert, Ph.D.

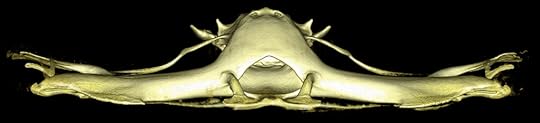

Computerized tomography scan of the same head of S. lewini. All soft tissue has been removed digitally leaving only the cartilaginous skeleton of the head. Image by J. Anthony Seibert, Ph.D.

What role does the morphology of the eye and vision play in the sensory abilities of hammerheads or other sharks?

Sharks and other elasmobranchs have different visual capabilities depending on their niche. Shark eyes have a rather typical vertebrate pattern and closely resemble fish eyes. Most, if not all sharks, have eyeshine, which is also called a tapetum, to increase light capture in dimmer environments. Most sharks have rods (night vision) and cones (daytime and color vision), although some sharks that live almost exclusively in dim or dark environments have only rod retinas. But those sharks, such as reef sharks, live in brightly sunlit environments will have a relatively high ratio of cones and probably have color vision. For example, the lemon shark (Negaprion brevirostris) and the silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) have rods and cones in roughly the same ratio, or even a higher ratio when compared to humans. In contrast, sharks that live in dim environments, such as benthic (ocean floor) sharks, may have an all-rod-retina and use vision for some purposes but rely on other senses for prey capture or predator avoidance.

Color vision in sharks is controversial. There is behavioral evidence that some coastal reef sharks have a form of color vision somewhat like color deficient male humans, but there is no universal agreement on this. Some sharks, especially those that live in darker environments certainly don’t have color vision and would have no reason for it. Some of the rays, however, definitely have color vision, so it is quite possible that at least some sharks do too.

Similarly, visual abilities and integration of the various sensory input into the brain in sharks is poorly understood, and very difficult to study. In hammerheads at least, a portion of the brain called the tectum receives input from the visual system as well as the auditory, mechanoreceptive, electroreceptive, somatosensory, and trigeminal nerves. It isn’t clear how these inputs are integrated, but the high degree of sensory input suggests that these creatures are tuned in to their surroundings with magnificent sensory perception.

Empirical evidence, though, tells us that sharks are inherently robust, vigorous, clever, and ultimately survivors. Sharks are ancient, inhabit all the oceans, and remain highly successful predators. Although the lineage has changed and radiated in many different directions, it has survived many global extinctions including the great dying of the Permian when 96% of all species were terminated. If it weren’t for shark–fin soup and massive fishing vessels, few sharks would be threatened by anything. These are magnificent animals with sensory mechanisms we are only beginning to understand.

Ivan R. Schwab M.D. is currently a professor at the University of California, Davis where he has worked as an Ophthalmologist for over twenty years, and was on the faculty at West Virginia University for seven years before coming to UCD. He is the author of Evolution’s Witness: How Eyes Evolved. His strong interest in biology and natural history has led him to investigate a diverse range of topics including ocular stem cells, bioengineered tissues for the eye and comparative optics and physiology. He has published extensively in these fields, with three previous books to his credit, and he was the winner of the 2006 IgNobel for Ornithology. He has combined those interests with one in evolution to produce this text on the evolution of the eye. If you are interested in more information on sharks or visual perception, go to www.evolutionswitness.com.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles about environmental and life sciences on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Knockoff fashion, trend-setting, and the creative economy

Conventional wisdom holds that copying kills creativity, and that laws that protect against copies are essential to innovation and economic success. But are copyrights and patents always necessary? Kal Raustiala and Christopher Sprigman approach the question of incentives and innovation in a wholly new way in The Knockoff Economy — by exploring creative fields where copying is generally legal, such as fashion, food, and even professional football.

The University of Virginia School of Law spoke with author Christopher Sprigman about the role of knockoffs in the fashion industry and their impact on the creative economy.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Christopher Sprigman is the Class of 1963 Research Professor at the University of Virginia School of Law. You can follow him on Twitter at @CJSprigman or on Facebook. Kal Raustiala is Professor of Law at UCLA and the author of Does the Constitution Follow the Flag? Together, they are the authors of The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation. Visit the Knockoff Economy website for more information, or like them on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Did we really want a National Health Service?

For most today, it’s difficult to imagine a British hospital system where treatment is not ‘free’ at the point of delivery, paid for out of national taxation, because in our imagination, the alternatives conjure pejorative images of the Americanisation of health. Those today opposed to decentralisation also echo the concerns of earlier health reformers like Dr Stark Murray, who thought the pre-nationalised hospital system simply disparate and chaotic. Others contemporaries drew attention to the “gloomy and depressing” hospital buildings, the “crowded, un-hygienic waiting rooms”, and the “unsympathetic and inhuman atmosphere” that pervaded public hospital wards. Public disquiet, it is widely suggested, drove forward demands for radical reform. Lawrence Jacobs, for example, argues that widespread dissatisfaction with existing standards of treatment, a strong public dislike of voluntary hospitals and their flag day systems of financing, and an aversion to workhouse-turned-municipal-hospitals pressured policy-makers into taking action. For Charles Webster the newly elected post-war Labour government simply “responded to public demand by decisively breaking with the gradgrind [utilitarian] health polices of the past.”

From the annual reports of Leicester Royal Infirmary.

But what do we really know, rather than think we know, about what ordinary people thought about hospitals before the NHS? Was there a strong demand for state nationalised medicine? Or were people generally satisfied with an already rapidly expanding but essentially localised service administered by voluntary hospitals, underpinned by a robust system of broadly based community fundraising activities and 2d per week mutualist contributory funds, and council-controlled public hospitals?

The Beveridge Report. Image courtesy of Nick Hayes.

In 1939 the British Institute of Public Opinion asked 1,523 men and women the question: “1,092 hospitals in Britain are dependent on charity for their support. Do you favour continuing this system, or should hospitals be a public service supported by public funds?” Seventy-one per cent favoured the latter. When later told about Beveridge’s “outstanding proposal that doctors’ and hospitals’ services should be extended, free of charge, to every person” — not surprisingly 88% thought it to be a good idea. Most thought a state-run medical service would benefit the nation, although surprisingly few knew why this might be. But most, too, felt old age pensions and family allowances the “most important” welfare concerns, while employment and housing, rather than health, consistently dominated questions on reconstruction priorities.

From the annual reports of Leicester Royal Infirmary.

The social survey organisation, Mass Observation, in conducting more detailed studies, shed a more nuanced light on public attitudes. It concluded that the “majority of people” were “satisfied with the available hospital services and treatment,” although maybe the “time was ripe for some changes on the hospital front.” Street collections, for example, unlike other forms of fundraising activity, were generally unpopular. As one factory manager commented: “I loathe flag days and resent the whole idea. I give to these because I am afraid to be rude to the vendor.” Many thought that essential services like hospitals should be state financed but not necessarily state run. Yet others simply offered an unreserved backing to voluntary provision. For one elderly working-class man voluntary hospitals were “exceptionally good. I don’t know what we would do without them places.” Others feared, reasonably or unreasonably, that state-run hospitals would be overcrowded — or depersonalised: “you won’t get the same interest taken in you.” Questioned about voluntary hospitals, “one person in two expressed unqualified approval, the greatest measure of support coming from working-class people in general and working-class women in particular.” Asked whether hospitals should remain as voluntary institutions, be run by a public authority or become partly voluntary and partly public, forty-two per cent supported a public system, but an equal number favoured wholly or partly retaining voluntary provision. Moreover, only a minority of the public (some 20%) wanted to see the hospitals funded directly through tax and/or the rates. Half of the people questioned opted instead for an improved form of state insurance, and a full 35 per cent wanted a system based on mutualist contributory payments.Where does this leave us? A number of recent studies have argued against notions of a wartime radicalisation, stoking demand for widespread social reform. Contemporaries surveying wartime public opinion, such as Mass Observation, similarly noticed such a reticence for change in health reform. It concluded:

On the surface, the evidence before us seems to indicate a fairly large amount of resistance to State interference in the field of medicine…. roughly half the population was opposed to any major change on the health front, a quarter disinterested and a quarter in favour of State intervention. But probing below the surface, we find that much of the feeling is simply in favour of no change, a fear of any change and feelings that existing conditions aren’t so bad after all, or that a change might be worse.

This poses the question as to why resistance to change by such a large margin should be dismissed simply as timidity, rather than as a positive vote for existing provision? Why should favouring the status quo be reconstructed in such a way? What we hear here are echoes of the progressive reformer’s voice at work; a voice that trumpets that “no less than three out of every seven questioned’ favoured the government taking over the hospitals,” while conveniently ignoring the fact that the other four did not. It was the same voice that asked such loaded questions in 1939, or prompted positive responses later. And it is this voice that still wrongly dominates our understanding of contemporary popular opinion of pre-NHS provision.

Nick Hayes is a Reader in Urban History at Nottingham Trent University. Having previously worked on post-war re-construction, and on civil society and voluntarism, he has recently focussed on the relationships between local hospitals and communities. He is the author of “Did We Really Want a National Health Service? Hospitals, Patients and Public Opinions before 1948″ in The English Historical Review, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

First published in January 1886, The English Historical Review (EHR) is the oldest journal of historical scholarship in the English-speaking world. It deals not only with British history, but also with almost all aspects of European and world history since the classical era: it covers the history of the Americas, including the foreign policy of the USA and her role in the wider world, but excludes the internal history of the USA since Independence, for which other scholarly outlets are plentiful.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

A British ante-invasion: “Telstar,” 17 August 1962

Many describe the 1964 arrival of the Beatles in New York as the beginning of the “British Invasion,” but UK rock and pop had begun culturally infiltrating our consciousness much earlier. Indeed, a London instrumental group topped American charts in the fall of 1962 with a recording that celebrated the first telecommunications satellite. Launched from Cape Canaveral on 10 July, Telstar initiated transatlantic telephone, television, and image transmissions by relaying beamed signals. The pace of multidirectional globalization in popular music increased almost immediately.

Joe Meek — one of the most iconoclastic figures in British music history — had managed to be fired by almost every employer he had ever had the opportunity to offend, even though his audio engineering intuition lay behind some notable hits, albeit hitherto only on British charts. He had designed the mixing board at Lansdowne Studios, one of London’s most successful independent recording facilities, and in 1960, he set up his own idiosyncratic studio on Holloway Road in North London. Here, he could experiment with the audio possibilities he heard in his head and not have to answer to anyone about how he achieved them.

The launch of Telstar appealed to Meek’s obsession with space travel and science fiction, nurtured in part by his National Service deployment at a radar station. He imagined the roar of the rocket, the missile racing into the sky, and a satellite perched high in the atmosphere. Wanting to capture and to transform this vision, Meek created a musical metaphor with a series of upward melodic leaps, but he lacked the skills to realize the song fully. Rummaging through his tape library, he came across the backing track to a recording (“Try Once More”) that had about the right tempo for his proto melody and superimposed his warbling voice over the music. He then turned to the Tornados, a group that normally backed the Liverpudlian singer-songwriter Billy Fury, but whom Meek often hired as session musicians for his studio. He expected them to translate his efforts into music and to realize his song.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Listening to the bizarre pastiche recording, the band members commenced to reworking the melody, realizing a harmonic structure to support it, and developing a rhythmic groove that articulated Meek’s optimistic excitement. Drummer Clem Cattini remembers that the band had to come to grips with a “melody that… had nothing to do with the actual chord structure that was on the backing track.” Nevertheless, none of the Tornados would receive any composing credit for their contributions, even though they were responsible for transforming Meek’s howls into music.

To add a futuristic touch to the recording, Meek had another musician, Geoff Goddard, double the melody on an early electronic keyboard, the Clavioline. The bright buzzing sound (already heard on recordings such as Del Shannon’s “Runaway”) helped to capture the spirit of the moment, but Meek still felt something lacking. Where was the rocket? Playing with a tight echo, he created a loop between the tape deck’s playback and record heads that transformed what sounds like rushing water (a flushing toilet?) into the roar of a Thor-Delta missile.

The recording soared to the top of the charts when released fifty years ago on 17 August 1962. Along with it, the Tornados rose to stardom in their own right and were excited to learn that they had an invitation to tour the United States to promote the disk; but their manager, Larry Parnes, insisted that the only way they could go would be as the backing band for Billy Fury. Given that few on the western side of the Atlantic knew or cared about Fury, tour dreams fizzled for the Tornados and, one by one, they disappeared into London’s session scene.

Although clarinetist Acker Bilk would have a transatlantic hit in 1963 with “Stranger on the Shore,” he hardly qualified as a rock musician and he certainly failed to generate much excitement. It would be over a year before another British recording would shatter the American musical consciousness when “I Want to Hold Your Hand” subverted its way into the Billboard charts. But in 1962, “Telstar” demonstrated what could be and hinted at what would be.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Thompson’s other posts here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers