Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1030

August 22, 2012

The jarring word ‘ajar’

All modern dictionaries state that the adverb ajar goes back to the phrase on char, literally “on the turn” (= “in the act of turning”). This is, most probably, a correct derivation. However, such unanimity among even the most authoritative recent sources should be taken with caution because reference books tend to copy from one another. Recycling a plausible opinion again and again produces an illusion of solidity in an area notorious for debatable results. That is why it is so interesting to read books published before Skeat’s dictionary (1882) and the OED came out. After their appearance, the lines of English etymological research hardened and few people took the trouble of questioning the giants’ conclusions.

First, let us look at the accepted explanation. The etymon of ajar is said to be on char (1510; cf. at char, 1708; Jonathan Swift). Char(e) is related to Old Engl. cierran “to turn.” Its root can be detected in charwoman and chore. Today we remember the latter word only with the sense “an unpleasant task” (“a job of work”), and it usually occurs in the plural (chores). Its meaning accords well with that of charwoman, even though the cause of the variation char ~ chore remains unclear (but see below).

[image error]

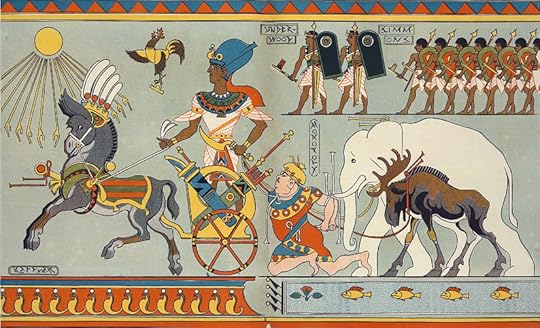

Five things you may not know about leadership PACs

Political Action Committees, or PACs, get considerable attention in our current debate about how we finance American elections. When most Americans think of a PAC, they think of the campaign contribution arm of interest groups, like the National Rifle Association’s “National Rifle Association of America Political Victory Fund,” or large corporations, like Honeywell International’s aptly named “Honeywell International Political Action Committee.” But as political satirist Stephen Colbert’s “Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow” super PAC illustrates, individual people can also create PACs. Personal PACs are increasingly a weapon in the arsenal of Members of Congress themselves. Members of Congress gave each other more than $41 million in the 2010 election cycle, and are on pace to best that number in 2012. So why would the recipients of PAC donations create their own PACs? And what can we learn about our legislators by studying their own campaign contributions?

(1) Leadership PACs exist because they solve a problem in the flow of money from contributors to the candidates who actually need them. Big-money donors want to give to sure winners, but sure winners don’t need big money donations. Big money donors are attempting to buy access to Members of Congress, so any money that goes to a losing candidate is wasted. (It bears noting, however, that there is virtually no evidence that lobbyists actually buy votes, or even try to buy votes.) But candidates who might lose are exactly the ones who need money, and leadership PACs solve this problem. Safe candidates with big campaign bank accounts — like those in the party’s leadership — can give their extra money to their partisan brethren, whose victories will help the safe candidate keep or maintain the majority for their own party (cross-party contributions are vanishingly rare). And marginal candidates can find their much-needed place in the flow of campaign dollars.

(2) Leadership PACs make small contributions but they can have big payoffs. No one is going to win an election on contributions from Members of Congress only. Sure, leadership PACs made more than $41 million in contributions in 2010, and that’s serious money to you and me. But it is a tiny portion of the $3.6 billion in total campaign contributions in the 2010 Congressional election. Leadership PACs really matter as signaling mechanisms to the big donors. An early donation from a powerful Member of Congress may send a message to larger contributors: “Contributions to this candidate will make me happy.” So those same contributors who seek to give money to a leadership PAC may also give to the candidates that PAC supports for exactly the same reason. In this sense, leadership PAC contributions are not instrumental. It is not the money they provide, but rather the road map they offer to the deeper-pocketed contributors.

(3) Leadership PACs might be more aptly renamed “Path to the Leadership PACs.” It was notable in 2001 when Hillary Rodham Clinton filed the paperwork for her HILLPAC before she was even sworn in as Senator, and the reasons are clear. More senior legislators attracted the money, since most freshman Senators have nowhere near Clinton’s rolodex. But now, early forays into controlling leadership PACs are de rigueur, especially among Members of the House. These newly-minted members of Congress are trying to build history of helping the party’s marginal candidates, which is now essential for climbing the rungs of the party leadership ladder. Like Clinton in 2001, many of these legislators have sources of financing that exceed their own re-election needs. This is particularly true for legislators in “safe” districts, whose certainty of re-election makes them nearly as valuable to traditional contributors as are their colleagues who have already reached the leadership. Of course, this is not meant to imply that deep pockets provide the only path to power. But it is worth noting that recently nominated GOP vice presidential candidate Paul Ryan gave more from his Prosperity PAC in 2010 than did either Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid or Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell that same year.

(4) Browsing leadership PAC behavior is actually very easy and kind of fun. The Federal Election Campaign Act mandated that direct campaign contributions be public and they are now searchable online. The trouble is a lot of Members of Congress are shy about their association with a leadership PAC, and it is tough to tell whose is whose, or even if a particular PAC is associated with a Member of Congress at all. For example, if you go to the FEC’s website for the Nutmeg PAC, you can download forms revealing how much it received and spent, and even the name of the treasurer in charge and the address, but not who controls the PAC. A better bet is to go to OpenSecrets.org, where you can learn not only that Nutmeg PAC belongs to Senator Richard Blumenthal, but also that he made contributions to a number of Democratic Senate candidates in 2012. Be warned: you can kill a lot of hours clicking links on OpenSecrets.org. Even the names legislators select for their PACs are interesting. Many names reflect the home district or state of their controlling legislator. For example, Max Baucus of Montana has Glacier PAC and Mary Landrieu of Louisiana has Jazz PAC. Others, like Eric Cantor’s “Every Republican is Crucial PAC,” have names that more closely reflect their purpose (but also note that the acronym for Cantor’s PAC spells out his first name).

(5) Sometimes, Members of Congress make leadership PAC contributions just because they like the recipient. Consider the donation patterns of New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand in the 2010 election. She gave to two types of candidates: Senate Democrats, who could help her party keep the majority, and House Democrats from her home state of New York. There was one deviation to this pattern in the entire election: Gillibrand gave $1000 to her dear friend Gabrielle Giffords of Arizona.

Kristin Kanthak is an associate professor of political science at the University of Pittsburgh. Her book, The Diversity Paradox, co-authored with George A. Krause, draws on leadership PAC contribution data to show that Members of Congress differentially value their colleagues based on the size of minority groups in Congress. You can follow her on Twitter at @kramtrak.

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for the next four weeks in anticipation of the Republican and Democratic National Conventions, and American presidential race. This week our authors are tackling the issue of money and politics. Read the previous post in this series: “The Declaration of Independence and campaign finance reform” by Alexander Tsesis and “Money for nothing? The great 2012 campaign spending spree” by Andrew Polsky.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about the book on the

Image credit: “The tariff triumph of pharaoh Wilson” by Udo Keppler in Puck, 1913. Source: Library of Congress.

Claude Debussy at 150

One hundred and fifty years ago today, one of the titans of the musical world was born. Claude Debussy’s innovative compositions influenced generations of composers and helped defined 19th century music. We’re celebrating his birth with an extract from the Claude Debussy entry by Robert Orledge (2002) in The Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham.

Debussy, (Achille-)Claude (b St Germain-en-Laye, 22 Aug 1862; d Paris, 25 March 1918). French composer.

The Early Years

Debussy’s early life was unsettled because of his father’s numerous occupations and his imprisonment after the Commune of 1871, and he received no formal education until he entered the Paris Conservatoire the following year. Piano lessons with Mme Mauté, who claimed to be Chopin’s pupil, led to early hopes of a virtuoso career, but Debussy decided in favour of composition with Ernest Guiraud in 1880 and won the Prix de Rome in 1884 with his cantata L’Enfant prodigue. The most promising work to emerge from this early period was a setting of part of Act II of Banville’s Diane au bois (1883–6), which anticipated the forest dream world of the Prélude à ‘L’Après-midi d’un faune’ (1894), his first great success.

The year 1893 proved a turning-point for Debussy: La Damoiselle élue at the Société Nationale on 8 April brought his music to public attention, and on 17 May he saw the premiere of Maurice Maeterlinck’s Symbolist play Pelléas et Mélisande (1892). In the shadowy, suggestive, and apparently simple world of Pelléas, Debussy realized he had found his ideal opera libretto, and he set the play directly, in prose (with only four scenes cut), between August 1893 and 17 August 1895. After Albert Carré finally agreed to produce Pelléas at the Opéra-Comique in May 1901, Debussy completed its orchestration, adding extra interludes at the last moment to facilitate the complex scene changes. Like Wagner, Debussy gave the orchestra a substantial commentatorial role and used recurring themes. But the latter were subtly adapted to the characters’ changing states of mind and feelings rather than being mere ‘visiting-cards’ announcing their entry.

Otherwise, Debussy’s theatrical career was one of ‘compulsive inachievement’ (Holloway). He never again found an ideal source, and his one-act Edgar Allen Poe operas Le Diable dans le beffroi (1902–?12) and La Chute de la maison Usher (1908–17) remain unfinished, as does his music for Le Roi Lear (1904) and No-ja-li (1913–14). Other dramatic projects were accepted for financial reasons and often required outside assistance to complete their orchestration.

After ‘Pelléas’

The performance of Pelléas et Mélisande forms a watershed in Debussy’s career. While his songs are evenly spread before and after in terms of quality, his best piano music dates from after he left his first wife Rosalie (Lilly) Texier for Emma Bardac in June 1904. Their daughter Claude-Emma (Chouchou) was born on 30 October 1905. The piano pieces inspired by their ‘honeymoon’ in Jersey and Dieppe in the summer of 1904 included Masques and the unusually extrovert L’Isle joyeuse. Chouchou’s infant world inspired the Children’s Corner suite (1906–8) with its celebrated Tristan parody in Golliwogg’s Cake-Walk, but Debussy is best known for his two books of Préludes (1909–10, 1911–13), which evoke a series of widely varied natural subjects from the antics of Christy ‘minstrels’ at Eastbourne in 1905 to dead leaves and the sounds and scents of the evening air. They are wrongly termed impressionistic, for Debussy’s inspiration owed far more to the painter J. M. W. Turner and to the literary symbolist movement. But in his orchestral Images (Gigues, 1909–12; Ibéria, 1905–8; and Rondes de printemps, 1905–9), Debussy told his publisher Jacques Durand that he was ‘attempting something different — in a sense, realities’, and he delightedly described to Caplet in 1910 how natural the join between the last two parts of Ibéria sounded, almost as if it were improvised, though such moments of complete artistic optimism were sadly rare.

Claude Debussy au piano l'été 1893 dans la maison de Luzancy (chez son ami Ernest Chausson). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Debussy’s style

‘Music is made up of colours and barred rhythms’, Debussy told Durand in 1907, and in his experiments with timbre and his efforts to free music from formal convention he tried many different solutions — from proportional structures based on the Golden Section (La Mer; L’Isle joyeuse) to the cinematographic form of Jeux, with its constant motivic renewal in which undulating fragments gradually evolve into a scalar theme which is itself broken off at its violent climax. As elsewhere in Debussy’s works, this climax is approached by a series of lesser ones and is placed as near to the end as he dared. Debussy’s earlier orchestral music includes the Nocturnes (1897–9), with their exceptionally varied textures ranging from the Musorgskian start of Nuages, to the wordless female chorus in Sirènes, whose study of ‘sea-textures’ is a kind of preparation for La Mer (1903–5). Here, the ever-changing moods of the sea are fully explored and the three ‘symphonic sketches’ together make up a giant sonata-form movement with its own Franckian cyclic theme.

After La Mer, the woodwind increasingly carried the main thematic burden, and the percussion gradually gained in importance via Ibéria to the subtleties of Jeux. Here, Debussy attempted to find an orchestra ‘without feet … lit from behind’ as in Wagner’s Parsifal. In spite of its radical nature, Jeux was overshadowed in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes season (15 May 1913) by the succès de scandale of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring a fortnight later. The cordial relations between the two composers deteriorated after this, though Stravinsky’s rising genius had earlier influenced Debussy. His career as a songwriter culminated in the sensitive and witty Trois ballades de François Villon (1910) and in the Trois poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé (1913). Two of the latter (Soupir and Placet futile) were also set by Ravel in the same year (to Debussy’s annoyance).

Debussy’s career in chamber music had had an auspicious beginning with his cyclic String Quartet (1893), the influential scherzo of which, with its cross-rhythms and flying pizzicatos, recalled the gamelan sonorities he had heard at the Paris Exhibition of 1889. But apart from the Première rapsodie for clarinet and piano (1909–10), written for the Paris Conservatoire, it was not until his final years that Debussy reverted to the medium. Ever concerned with the necessity for French music to be true to itself, he planned a series of six chamber sonatas in a nationalistic spirit looking back to Rameau. Before finally succumbing to rectal cancer, he completed three of them: the Cello Sonata (1915,), the Sonata for flute, viola, and harp (1915), and the Violin Sonata (1916–17). All three sonatas anticipated neo-classicism in their simplicity, clarity, and stylistic restraint.

First published in 1938, The Oxford Companion to Music has been the first choice for authoritative information on all aspects of music. Embracing the world of music in all its variety — including jazz, popular music, and dance — the Companion offers a concentrated focus on the Western classic tradition, from the Middle Ages to the present day. More than 8,000 articles sweep across an extraordinary range of subjects: composers, performers, conductors, individual works, instruments and notation, forms and genres. From the study of music–theory, aesthetics, scholarship — to the way it is performed and disseminated, the Companion provides comprehensive, accessible coverage of music in all its artistic, historical, cultural, and social dimensions. The Oxford Companion to Music is also available online as part of Oxford Music Online (along with Grove Music Online, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music) and Oxford Reference Online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Are crimes morally wrong?

Are crimes morally wrong?

Yes and no; it depends. It’s easy to think we know what we’re talking about when we ask this question. But do we? We need to know what we mean by ‘crimes’. And we need to know what we mean by ‘morally wrong’. This turns out to be trickier than we may at first think.

First of all, there are two different conceptions of crimes, and the answer to our question will be different depending on which conception we have in mind.

One conception sends us to the law books, where crimes are defined in terms of the conduct, the consequences, and the circumstances that are required for a crime to be committed. Here, it is liability to criminal punishment that is of concern, and I will call this the criminal liability conception of crime.

The other conception, which I will call the narrative conception of crime, is quite different. When a crime is the subject of a story there are many things included that are legally irrelevant, yet often they turn out to be at the very heart of the story. The story will almost always include some account of what prompted the crime as well as interesting facts about perpetrator, victim, and others who are in one way or another related to the crime. News stories fit this conception of a crime, and so do the accounts in books that tell the story of the crime as a human narrative. Not all stories of crimes are equally interesting, yet each and every crime that interests the legal system has such a story to be told to anyone who will listen.

Just what is it that makes a crime morally wrong, if indeed it is morally wrong? Looking first at crimes as the law conceives them – the criminal liability conception of crime – I suggest there are three considerations to make:

The suffering a crime causes marks it as morally wrong.

Then there is the violation of rights when a crime is committed, such as a right to life, a right to be secure in one’s person and one’s property, and a host of other rights the law is intended to protect. Such violation of a right seems a good reason for regarding a crime as morally wrong.

And finally, admittedly more controversial, but not implausible, a third reason for saying a crime is morally wrong is the act of bad faith it represents in failing to observe a presumed undertaking to abide by the law, an undertaking that every member of society is bound to adhere to as a condition of enjoying the benefits of living in the society.

Crimes are of various sorts, and when subjected to moral scrutiny, different sorts turn out to be different morally. The most serious crimes, such as murder, rape, robbery, satisfy all three conditions. Other crimes satisfy only one or two conditions, which is enough to mark them as morally wrong, though less so. At the other extreme we have a myriad of crimes, created to enforce some special regulatory policy of government, where commission of the crime causes no suffering, violates no rights, and can not be said to be a breach of a mutual undertaking to abide by the law since the law is not of general benefit. Such crimes are therefore not morally wrong, though this does not mean that it is morally wrong to enforce them. That is quite a different matter. Though a crime may not be morally wrong, it is morally permissible for the law that creates it to be enforced so long as the policy the enforcement supports is a morally sound policy, and there is no alternative to criminalization to achieve compliance. Incidentally, and paradoxically, many crimes designated as morals offenses are not morally wrong. These crimes, which typically are related to sexual taboos, do not satisfy any of the three conditions and, furthermore, are often expressions of policies who soundness is questionable, as evidenced by their rapid disappearance with changes in social attitudes.

Now for what I have called the narrative conception of crime. Think of Billy Budd, Jesus Christ, Raskolnikov, and Colonel von Stauffenberg. This odd assortment each has his own very different story of a crime he committed. Asking whether the crime was morally wrong takes us into territory that the law itself knows nothing of, nor is there any reason why it should. The business of the law in determining criminal liability is a concern with the harm that has allegedly been produced or threatened by the conduct of the accused. Literature and history abound with examples of indisputable legal guilt and equally indisputable moral innocence welded together. Even in the humble everyday workings of criminal justice, the truth of tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner resides in the very different moral assessment that the fuller context produces, for now we are judging human life, and not simply an abstraction from it that suits legal purposes. The case for moral exoneration is often stronger than the case for moral condemnation if all of the morally relevant elements bearing on the criminal conduct is given due consideration. It is not that the legal system means to be morally parsimonious or morally perverse, only that its role as protector and enforcer would be fatally compromised if what seemed the best case to be made morally, with everything of moral relevance admissible, were allowed to prevail in a court of law.

While determinations of guilt or innocence must adhere rigorously to the criminal liability conception of a crime, elements of the narrative conception show themselves at other stages of the criminal process where discretion is needed. In deciding whether to prosecute, and on what charges, a fuller picture of the person and the events will inevitably have significant influence. An even greater influence is exerted when sentencing decisions are made. And even during the course of a trial, a great deal of the evidence will influence a jury’s view of the defendant’s moral standing as that evidence tells a larger story even though the evidence is introduced just to determine whether he committed the crime. The view of his moral standing will, in the jury’s mind, tend to replaced the question “Did he, or didn’t he” with the more comprehensive question “Should we, or shouldn’t we, find him guilty”.

Crimes may or may not be morally wrong. Even if they are, that is not a good reason for punishing the perpetrator. What is a good reason is an equally tricky question. But I leave that for another day.

Hyman Gross is a retired law professor, now living in Cambridge, England, and is sometime Arthur Goodhart Professor of Legal Science and a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. He is the author of Crime and Punishment: A Concise Moral Critique

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 21, 2012

Team Romney’s game change

In our fast-paced world where candidates throw everything but the sink at television and Internet audiences to see what sticks, Mitt Romney made a particularly gutsy move last week by adopting Medicare in his fight against Obama and Obamacare. Together with the selection of Paul Ryan as VP candidate, this was a game change revealing that Team Romney is going straight for demographics in this home stretch of the campaign.

For months, the Romney team has tried to make the election a referendum on Obama’s first term. They believe they have failed, in large part due to the Obama campaign’s very successful negative campaign on Romney’s tax returns and record with Bain. They now know that an unemployment rate hovering above 8% is the new normal and they need to be more aggressive to get through Obama’s Teflon hide.

The Medicare strategy is clearly targeted at states with an older population. It is a strategy made for Florida and Pennsylvania. The Paul Ryan pick, on the other hand, will not only help Romney in Wisconsin, but with young voters. If Romney can erode Obama’s popularity among the young, especially those between 18 and 24, and secure the support of the older in Florida, he may have a way to 270.

But as all game changers are, these are high risk strategies, very much like John McCain’s pick of Sarah Palin. Most Americans trust the Democrats more on Medicare than the Republicans. More importantly, most Republicans don’t know how to talk about Medicare. It is a convoluted argument indeed to lament that America is becoming an entitlement state while at the same time say that Romney would protect the entitlements of those above 55 (unlike Obama). Yet this is a problem surmountable with enough campaign advertisements which we know Team Romney can afford. A deeper challenge remains, however. Paul Ryan is young and likeable, but as we know from 2008, it isn’t easy to transfer charm upwards from the second person on the ticket.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Money for nothing? The great 2012 campaign spending spree

Money is a main subtext of the 2012 elections: how much will be spent, who donates and spends it, how quickly it may be exhausted and whether campaigns have enough. Before November, we may spend as much time talking about campaign spending as the issues and the candidates.

Some of this is a consequence of the Supreme Court decision in the Citizens’ United case that effectively tossed aside a longstanding regime of campaign finance regulation and opened the door to flood of dollars. We are now engaged in a grand experiment to test the effects of unlimited “independent” expenditures on our democratic politics. But it would be unfair to pin all the blame on the Court’s literalist reading of the First Amendment. Even before the decision, campaign spending was on an upward trajectory. Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign shattered the record for presidential campaign expenditures.

With the dollars flying around, we need to ask about the impact on the election of all of that spending. Overall, the Republicans and their super PAC allies will outspend the Democrats and their associated PACs by a significant margin. Yet better-funded candidates have often lost elections. So long as candidates reach a certain funding threshold that allows them to achieve media visibility, the marginal value of each additional dollar declines.

It may help to view campaign spending from the voters’ vantage point. By this point in the campaign, most voters have made up their minds, at least at the presidential level. The only thing that will stop them from casting a ballot for their preferred candidate will be obstacles that impede their opportunity to vote — something that Republicans this year are going all out to put in the way of likely Democratic voters.

For voters who have decided, campaign spending is unlikely to have any impact. They will filter out opposition messages, while the ones slanted in favor of their preferred candidates will merely reinforce their preferences.

Add to this the fact that much of the country won’t be exposed to the ad blitzes planned by the campaigns and the independent groups. In my own home region, the New York metropolitan area, the presidential campaign remains largely invisible because the media market doesn’t encompass any of the battleground states. Moreover, since congressional redistricting has reduced the number of contested House contests, even down ticket spending will be modest. Across the country, fewer than a dozen states will be closely contested. Most of America, then, will be distant spectators to the media deluge that will follow the conventions.

All of which means, at least for the presidential campaign, that phenomenal sums will be spent chasing a handful of undecided voters in a handful of swing states. The Obama campaign made an interesting choice to spend heavily early (a record total of $400 million from the beginning of 2011 through 30 June 2012), seeking to define Mitt Romney as uncaring and out of touch. The approach has damaged the Republican, raising his unfavorable rating in opinion polls. But now Democratic donors are tapped out. Romney in recent months has raised more money than has the president, and the conservative PACs still have suitcases of cash to pour into the race. From this point forward, then, the spending will tilt heavily in favor of the GOP, both at the top of the ticket and in contested congressional races.

I side with those who believe that beyond a certain saturation point, campaign advertising ceases to register. Some observers argue that the lack of movement in polling numbers in states like Ohio indicates voters have already tuned out the campaigns. Nevertheless, the average undecided voter in Ohio or Florida will continue to be assaulted by a barrage of ads by each side every week. By November, the opposing messages will cancel each other out. Yes, for the handful of voters who make up their minds just before Election Day, the last few messages may turn the tide, because these will be most readily recalled in the voting booth. But neither side can gain a significant edge when both sides pound away to the end, like two punch-drunk boxers waiting for the final bell.

What may make a difference is not the money but some event that reinforces or resonates with the story that one side is trying to tell about the campaign. It might be a particularly strong or weak economic report. Or it could be an international crisis. (For example, on the eve of the 1956 election, Great Britain, France and Israel provoked a crisis over the Suez Canal that allowed Dwight Eisenhower to demonstrate a commitment to international norms, reinforcing his image as a steady leader in dangerous times.) Events empower stories. They make it possible for a campaign or party to declare, “So, you see, it’s just as we said.” No amount of campaign spending can have the same impact.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for the next four weeks in anticipation of the Republican and Democratic National Conventions, and American presidential race. This week our authors are tackling the issue of money and politics. Read the previous post in this series: “The Declaration of Independence and campaign finance reform.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Macro shot of the seal of the United States on the US one dollar bill. Photo by briancweed, iStockphoto.

Arne Kalleberg reflects on 90 years of Social Forces

Sociology has adopted much more sophisticated methods and theories over the last one hundred years. The growth in specialization has made it difficult for many scholars to have a good sense of what is happening in areas in which they are not specialists. But Social Forces, a leading international social science research journal, has grown and changed along with it. The 90th anniversary issue has just published and is free for viewing for a limited time.

We sat down with Kenan Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Social Forces editor Arne Kalleberg to discuss the past, present, and future of sociology, social sciences, and the journal.

When did you join the journal?

I became Editor of Social Forces on 1 July 2010. My association with the journal began much earlier, however, in 1986, when I joined the editorial board upon being appointed as a Professor at the Sociology Department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (All faculty members at UNC-Chapel are on the editorial board.)

What do you know now that you wish you had known when you took over the editorship?

So far, my editorship has gone fairly smoothly (“knock on wood”). One thing I was very worried about was whether we could get timely reviews from referees. This has been a constant challenge, but I have been pleasantly surprised that this has not been as difficult as I feared.

How has your editorship impacted your own academic interests or methods?

Editing Social Forces has broadened my scholarly interests. Since Social Forces is a general sociology journal, I now regularly read papers on diverse set of topics, most of which I wouldn’t have ordinarily read. This has given me a much greater sense of the variety of research that is going on in sociology. Moreover, as Social Forces also encourages submissions from social science fields in addition to sociology (such as psychology, economics, history, among others), I have been able to keep up with some of the exciting in research in those fields as well.

My editorship has also impacted my teaching. I now teach an annual course for graduate students on “publishing in sociology.” In this course, we discuss the various aspects of publishing, from writing the paper, to reviewing, writing cover letters, and responding to reviews. Students come to the course with a paper they are working on, and the goal is to submit the paper to a real journal by the end of the semester.

What was one of the most unexpected things to come out of Social Forces in its 90-year history?

This is a hard question, as I have been associated with Social Forces for less than a third of its long history. For the 90th anniversary, I asked authors of the most highly cited articles in the past four decades to write recollections about their articles, reflecting on their impact on the field and on the direction research on their topics has taken since they wrote them. I was somewhat surprised that everyone I invited responded enthusiastically to this invitation and wrote very compelling reflections. (I was much less surprised by the latter than the former!)

What is the current state of research in this field?

Research in sociology is more sophisticated than ever. Sociology has always sought to incorporate the latest advances in methodology (both quantitative and qualitative) as well as from related social sciences (such as anthropology, economics, psychology, among others) in its pursuit of answers to the most pressing and interesting questions about social life.

What do you think the future holds for this field?

Sociology is alive and well, and is more vibrant and vital than ever. For example, membership in the American Sociological Association has been high in recent years. The number of baccalaureate degrees awarded in sociology has increased by 70 percent since 1990, the number of master’s degrees has increased by about two-thirds in the last fifteen years, and number of doctorates has increased steadily since 1990.

A major reason why sociology is so healthy is that it is increasingly relevant and essential to explanations of a growing number of issues and problems faced by societies and nations around the world. We need sociology now more than ever before because many of the challenges facing us in the 21st century involve social forces, often in interaction with physical and biological factors.

What do you think the future holds for academic journals?

Peer-reviewed academic journals are likely to continue to play a central role in the transmission of cutting-edge scientific research. Their form is likely to continue to evolve, however, as technological innovations create new opportunities to communicate this research to various audiences. For example, the life of print journals is likely to be limited, as journals move to on-line delivery. Moreover, social media is transforming markedly the ways in which we can inform the scientific community (and the public more generally) about the latest scientific advances. But regardless of the medium, peer review will continue to be essential to maintain the quality of research and thinking that is transmitted.

What’s your vision of Social Forces in 10 years for the 100th anniversary issue?

My goal is for Social Forces to become the leading international social science research journal in the world. There are four components of our internationalization strategy.

First, we have expanded our Editorial Board by adding members representing 23 countries in addition to the United States. We will rely heavily on these Editorial Board members to identify high quality research emanating in their countries and to encourage authors to submit their best work to Social Forces. The International Editorial Board — together with their American counterparts (both at UNC-Chapel Hill and elsewhere) — will be asked to review manuscripts, suggest potential reviewers and to advise the journal on a variety of issues.

Second, we will give priority to publishing research that is comparative and cross-national in content. I will also encourage authors to consider the comparative implications of their research, even though the data analyzed might be from a single country.

Third, we will seek to increase the journal’s readership by scholars in countries across the globe. Our efforts in pursuit of this goal will be aided considerably by our partnership with OUP, which has an extensive international marketing operation and a well-established presence and reputation around the world.

Finally, we are attempting to achieve all these goals in part by forming affiliations with a variety of national sociological associations. We will mark our progress toward this goal by locating affiliated national association on the world map that will appear in the front matter of the journal starting with the 90th anniversary issue.

Arne L. Kalleberg is a Kenan Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has published more than 100 articles and chapters and eleven books on topics related to the sociology of work, organizations, occupations and industries, labor markets, and social stratification. His most recent book is Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s (Russell Sage Foundation, 2011). He is currently working on projects that examine the growth of precarious work in Asia and institutional determinants of inequality in the United States. He served as President of the American Sociological Association in 2007-2008.

The 90th anniversary issue of Social Forces has just published and is free for viewing for a limited time. Published in partnership with the Department of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Social Forces is recognized as a global leader among social research journals. The journal emphasizes cutting-edge sociological inquiry and explores realms the discipline shares with psychology, anthropology, political science, history, and economics.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The king of instruments: Scary or sleepy?

Whenever I tell people I’m an organist, I usually get one of two reactions. The person I’m talking to hunches over and sings the formidable opening notes of J.S. Bach’s D minor prelude; or, the person relates the organ’s slumberous effect during seemingly interminable church services.

Why the disparity in reactions? Why would the pipe organ signify something scary for some people (cue the organ-accompanied Vincent Price monologue in “Thriller”), and something sleepy for others (cue “Nearer, My God, to Thee” played at half speed)?

When you think about it, the pipe organ is simultaneously pew-shakingly powerful and geographically limited. The organ can produce a wide range of sounds. As a composer friend said when I was showing him around the instrument: “The combinations almost seem limitless…” Nonetheless, I will only be able to play the composition he’s writing for me at the mostly religious, somber venues that house pipe organs — to the exclusion of the more hip New York City contemporary music venues.

Of course, adventurous composers like Bach (an organist practically from the time his feet could reach the pedal-board) have chosen to channel the unearthliness of reverberant religious locales into their music, composing powerful — at times, shocking — pieces of music.

Case in point, another composer friend wrote a piece for my Master’s recital several years ago, based on the hymn tune “Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.” He had worked this composition so that when the music reached the point at which the hymn text mentions Hell, the piece would reach its apex with an extremely loud and reverberant chord. When I played the Hell chord in my performance, an elderly woman jumped so violently she nearly fell out of the pew (and left my recital directly thereafter).

Click here to view the embedded video.

This recording of György Ligeti’s Volumina is also an excellent example of the organ’s potential for shattering the sobriety of its locale. (N.B. This is a somewhat abbreviated version of Volumina, which is usually around nine minutes long. I just couldn’t resist this particular monk’s interpretation.)

Whatever you think of when you think of the pipe organ (if you think of it at all), remember this: There’s a person behind that instrument! Very few of us live in church basements plotting evil schemes, and even fewer of us purposely set out to bore you to sleep. We’re just in love with the king of instruments.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog post “Saving Sibelius: Software in peril.”

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

August 20, 2012

Buddhism or Buddhisms? Lexical consequences of geo-political categories

In a previous post, we argued that the geo-political categories commonly employed in both popular and academic representations of Buddhism are problematic. The problems were grouped into rhetorical and lexical; the rhetorical consequences having been considered there, we now turn to the lexical. Specifically, the lexical distinction between mass nouns and count nouns clarifies how thinking about the subject of study logically (and implicitly) follow from ways of talking about that subject.

The term “Buddhisms” may feel awkward when uttered or written (my spell check certainly doesn’t like it). That very awkwardness points to the confusion that can result from failing to distinguish between mass nouns (“the gravel in that heap”) and count nouns (“the cars in the parking lot”). One speaks of gravel in the singular for a heap of it because there is no significant reason to distinguish each individual piece from all the others; one speaks of cars in the plural because each one is identifiably different, and that is the kind of difference that makes a difference. Buddhism as a mass-noun (e.g., Buddhism in China) implicitly treats Buddhism as a kind of whole, of which each instance is a part indistinguishable from the whole. Buddhisms as a count-noun clearly says that there are a whole bunch of different kinds of Buddhisms that happen to be located in China. A further problem with the mass-noun Buddhism, is that it in turn supports the kind of essentializing — “Chinese Buddhism” — discussed in the previous post.

Dance of the Lord of Death (Paro, Bhutan). Photo by Jean-Marie Hullot, 2008. Creative Commons License.

While this may be considered “merely” a grammatical issue (or even diminished to the level of an innocent stylistic usage), such a view fails to take into account the ways in which the logic of such grammar structures conceptualization within the discourse of Buddhist studies. For example, from accepting a category such as Tibetan Buddhism, treated as a mass noun, it would then follow that one could reasonably talk about the characteristics of Tibetan Buddhism, such as for example, the tulku system. From that, it would in turn follow that any form of Buddhism found in the Tibetan context that did not include a tulku system deviates from the norm. What follows then is that it is the abnormality itself that requires explanation, not the tulku system. Such judgments all too easily shift over into exercises of power and authority — who determines what is normal also determines what is abnormal. Normal and abnormal are themselves ambiguous descriptors. They are simultaneously capable of signifying a more literal value-neutral judgment as to “most common” (most frequently occurring), and a value-laden connotation implying unacceptably different, pathological. Normal in the “statistical” sense of typical is a matter of empirical verification or falsification, and therefore serves a valid intellectual function. Uncritically accepting characterizations that instantiate one form of Buddhism as more normal (in the symbolic sense of “healthy”) than another is, however, intellectually dysfunctional.

This is, of course, not to affirm the naïve belief that academic inquiry is separate from the travails of religious realpolitik. Certainly scholarship whether willingly or not becomes involved in practical religious issues, including sectarian conflicts. The geo-political categories that dominate the field of Buddhist studies are not natural ones, but rather social constructs. As social constructs they have been created in the service of many different purposes, not all of which are to the benefit of an academic inquiry. Of course, academics aren’t free from such purposes, and I’m not proposing some simplistic and idealized image of objective, value-neutral scholarship — an unnuanced “view from nowhere,” in Thomas Nagel’s phrase. Rather, the responsibilities of scholarship require self-critical reflection on its formulation, including reflecting on the lexical consequences of using a mass noun, when a count noun is more appropriate. No matter the discomfort that such critical self-reflection produces for those of us who have built our academic careers, not to mention personal identities, within the frameworks being questioned. It is still a matter of responsible scholarship to pursue such reflections.

Richard Payne is the Dean of the Institute of Buddhist Studies at the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley; serves as Editor-in-Chief of the Institute’s annual journal, Pacific World; is chair of the Editorial Committee of the Pure Land Buddhist Studies Series; and is Editor-in-Chief of Oxford Bibliographies in Buddhism. He also sporadically maintains a blog entitled “Critical Reflections on Buddhist Thought: Contemporary and Classical.”

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Read more about Buddhism on the OUPblog.

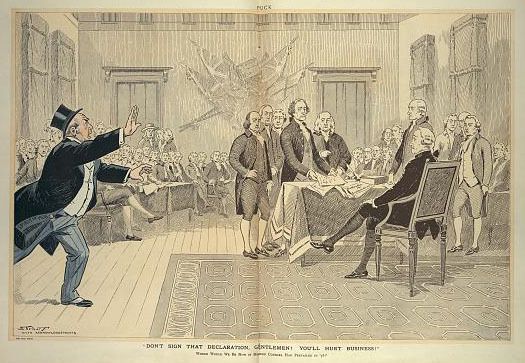

The Declaration of Independence and campaign finance reform

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for the next four weeks in anticipation of the Republican and Democratic National Conventions, and American presidential race. This week our authors are tackling the issue of money and politics.

By Alexander Tsesis

The Supreme Court’s recent equation of personal and corporate campaign contributions has vastly increased corporate and super PAC donations during this election year. The Court’s premise that corporations deserve the same right to political speech as ordinary people is a modernist interpretation that would have sounded completely foreign to the framers of the Declaration of Independence. It is particularly curious that self-proclaimed originalists — Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas — joined judicial opinions striking key provisions of the bipartisan McCain/Feingold Campaign Finance Reform Act and the Montana ban on corporate campaign spending. Political speech at the time of independence only applied to natural persons and had nothing to do with corporations. Indeed, in 1776 corporations were entities operating through personal charters granted by legislatures, not the general incorporated entities of today that shield shareholders and boards of directors from liability.

At the tail end of this year’s term, the Supreme Court reconfirmed its earlier holding in the well know Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case, which found that any campaign finance laws that treat corporations and individuals differently violate the First Amendment. These judicial opinions expressed a view that was incompatible with principles that informed the framers of the Declaration of Independence.

To many political insiders, the outcome of Citizens United was somewhat surprising because, unlike voters, corporations are only metaphorically persons; in reality, they are artificial entities that are governed by special laws. To search for the core value of political speech we need look no further than the Declaration of Independence. The founding generation insisted that government be based on the consent of the people. They rebelled for lack of representation in the British Parliament and determined to establish a nation where voting would be an inalienable right of qualified citizens. But corporations have no inalienable rights. The Declaration’s famous assertion that “all men are created equal… [and] they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights” simply doesn’t apply to entities with “perpetual life” that are created by articles of incorporation. As a creature that owes its existence, form, and structure to the state, no corporation has the inalienable rights that informed the Declaration of Independence’s framers’ notion of political community. Having no natural rights — but only positive regulations on creation, operation, and dissolution — corporations’ communications can be restricted differently than the speech of ordinary people.

"Don't sign that declaration, gentlemen! You'll hurt business!" by S. D. Ehrhart, Puck, 1908. Source: Library of Congress.

The Declaration of Independence insisted that ordinary people are the true sovereigns of a nation that is governed by principles and institutions that further “safety and happiness.” Elections are critical to achieving those ends. In many of the Declaration’s paragraphs, the framers renounced the British government for being unresponsive to the people and established the enduring principle that our country enjoy the benefits of popular sovereignty. Unchecked corporate expenditures on behalf of favored candidates can be used to curry political favors that benefits a small sector of the population but harm ordinary Americans already reeling from the economic hardships.

An essential feature of the newly founded nation was, and continues to be, government by consent of the people. While foreign citizens have no right to participate in representative elections, a corporation whose board of directors may be composed of foreigners with no legal status in the United States, can give freely to politicians’ even though they cannot vote in any election.

At the oral argument to Citizens United, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked rhetorically why Congress could not set different campaign finance standards for corporations and ordinary people given that, in her words, “[a] corporation, after all, is not endowed by its creator with inalienable rights.” She received no reply from the attorney, and her insight into the connection between the Declaration’s political ideals and constitutional interpretation didn’t enter into the majority or dissenting opinions.

Neglect of the Declaration of Independence is unfortunate. The document’s statement of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” as Justice William O. Douglas expounded, have “found specific definition in the Constitution itself, including of course freedom of expression.” The existence of an intrinsic right of citizens to pick leaders is presumed in the Declaration of Independence, but to this day corporate entities do not have voting privileges in general elections; and we can only hope that won’t change. In Citizens United and the more recent case striking Montana’s corporate finance law, the Court might have done well to follow its own assertion, made more than a hundred years ago, that “it is always safe to read the letter of the Constitution in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence.” That document speaks to us today as it did to the framers, but its protection of inalienable rights extends to natural persons not corporations.

Alexander Tsesis is Associate Professor of Law at the Loyola University, School of Law-Chicago. He is the author of For Liberty and Equality: The Life and Times of the Declaration of Independence; We Shall Overcome: A History of Civil Rights and the Law; The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom; and Destructive Messages: How Hate Speech Paves the Way for Harmful Social Movements.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers