Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1026

September 3, 2012

Paul Ryan and the evolution of the vice presidency

By Edward Zelinsky

By selecting Representative Paul Ryan as the Republican vice presidential nominee, Romney confirmed the decline of the traditional role of vice presidential candidates as providers of geographic balance. Ryan’s selection reinforces the shift to a more policy-oriented definition of the vice presidency. This shift reflects the nationalization of our culture and politics and the increased importance of the general election debate between vice presidential candidates.

Traditionally, a vice presidential candidate usually came from a large swing state in a section of the country removed from the presidential candidate’s home state. The classic (and most successful) instance of this once conventional pattern was John Kennedy’s selection in 1960 of Lyndon Johnson as Kennedy’s running mate. Johnson was picked to deliver the electoral votes of Texas and other southern states to a ticket headed by a candidate from Massachusetts. It worked.

Traditionally, a vice presidential candidate usually came from a large swing state in a section of the country removed from the presidential candidate’s home state. The classic (and most successful) instance of this once conventional pattern was John Kennedy’s selection in 1960 of Lyndon Johnson as Kennedy’s running mate. Johnson was picked to deliver the electoral votes of Texas and other southern states to a ticket headed by a candidate from Massachusetts. It worked.

A generation later, another Democratic presidential nominee from Massachusetts, Michael Dukakis, emulated Kennedy by selecting as his vice presidential nominee Texas Senator Lloyd Bentsen. This time it didn’t work, but the Dukakis-Bentsen ticket fell well within the tradition of geographic balancing.

The new, policy-oriented pattern commenced in the next election in 1992 when Bill Clinton of Arkansas named as his running mate the senator from next door, Tennessee’s Al Gore. In terms of geographic balance, a Clinton-Gore ticket made no sense — two southerners from neighboring states.

Clinton saw the role of the vice president differently. Gore possessed Washington experience and connections Clinton lacked. Gore thus provided, not geographic balance, but national experience and expertise. This departure from traditional geographic ticket balancing worked for the Democrats both in 1992 and in 1996.

When it was Gore’s turn to choose a running mate in 2000, Gore too departed from tradition, turning to Connecticut’s junior senator, Joe Lieberman. True, Lieberman came from a northern state, Connecticut. But the Nutmeg State, then with eight electoral votes, was not a great electoral prize nor was it in serious doubt for the Democratic ticket. Gore turned to Lieberman because the ethically-challenged image of the Clinton Administration was a problem for Gore. Lieberman’s reputation for ethical probity provided useful ballast to the Democratic ticket.

But it was the Bush-Cheney ticket in 2000 which truly broke the geographic balancing mold. Bush did not pick Cheney for the vice presidency to secure Wyoming’s three electoral votes. Rather, the Texas Governor selected Cheney to bring to the ticket Cheney’s perceived gravitas including his experience as Wyoming’s congressman, Secretary of Defense, and White House Chief of Staff.

By 2008, it was no longer innovative when Barack Obama selected Joseph Biden of Delaware as his vice presidential running mate. Biden was not placed on the ticket to secure Delaware’s three electoral votes or otherwise secure geographic balance. Like Gore and Cheney, Biden was perceived as a Washington insider and policy expert. Biden’s experience augmented a ticked headed by a presidential candidate whose tenure in the nation’s capital consisted of a single, not-yet-completed term in the US Senate.

Ryan fits comfortably within the newer, policy-oriented vision of the vice presidency. It doesn’t hurt that Ryan comes from Wisconsin, a state the Republicans are eager to put into play. But unlike some of the other individuals Romney considered for the vice presidential nomination (such as Senator Portman of Ohio or Senator Rubio of Florida), Ryan doesn’t come from a major swing state. Indeed, Ryan himself has never run for statewide office in Wisconsin.

Ryan was picked because he is a young, articulate conservative policy wonk. Romney chose Ryan because of Ryan’s ideas, not Ryan’s home state.

What has caused this evolution of the vice presidency? A key factor is the nationalization of our culture and our politics. Kennedy and Johnson (as well as Dukakis and Bentsen) were individuals deeply rooted in their respective home states. We have become a more mobile nation. Barack Obama (born and raised in Hawaii, educated in California, New York, and Massachusetts) was a senator from Illinois. But his biography is itself a story of geographic balance.

The same is true of Mitt Romney, born and raised in Michigan, educated in California, Utah, and Massachusetts. Romney’s business career occurred in Massachusetts as did his one term as the Bay State’s governor. But no one even expects Romney to carry Massachusetts in November.

Just as the life stories of the presidential candidates are no longer centered in their “home” states, the electorate reflects America’s mobility as a nation. Consequently, geographic ties mean less today than they did in the past; roughly 40% of Americans today live in a different state than the state in which they were born.

Moreover, modern communications instantly nationalize our political figures. Paul Ryan will soon be as well-known in Texas as he is in Wisconsin. In this world of mobility and instant national communications, geographic ticket-balancing is less compelling than it was in the past.

A second factor buttressing the evolution of the vice presidency is the emergence of the vice presidential debates. When Kennedy and Nixon conducted the first presidential debates in 1960, there was no vice presidential debate between Johnson and the Republican nominee, Henry Cabot Lodge.

Today, the vice presidential debate is an important event on the campaign calendar. In picking a running mate, a presidential candidate must consider this event. My son Aaron and his colleagues at the Presidential Debate Blog correctly observe that Senator Bentsen uttered the most famous line in presidential debating: “Senator, you are no Jack Kennedy.” However, debate skills don’t always correspond with geographic balance. Ryan was in large measure selected because of his ability to go toe-to-toe, rhetorically and intellectually, with Vice President Biden.

We will, no doubt, some day again see a presidential candidate select his or her vice presidential running mate from a large swing state in a section of the country far from the presidential candidate’s home state. But that geographic balancing mold is now longer dominant.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His column ‘EZ Thoughts’ appears on the OUPblog monthly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Seal of the Vice President of the United States. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Networked politics in 2008 and 2012

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for four weeks as the United States discusses the upcoming American presidential election, and Republican and Democratic National Conventions. Our scholars previously tackled the issues of money and politics, and the role of political conventions. This week we turn to the role of media in politics.

By Daniel Kreiss

A recent Pew study on the presidential candidates’ use of social media described Barack Obama as having a “substantial lead” over Mitt Romney. The metrics for the study were the amounts of content these candidates post, the number of platforms the campaigns are active on, and the differential responses of the public.

Metrics such as these often tell us very little about how campaigns are actually using social media and the Internet more generally, and their relative strategies for and success in doing so. If there is anything that I found in my last six years of researching new media and electoral campaigns, it is that much of what makes for the successful uptake of new media is often the organizational decisions that receive scant scholarly and journalistic attention. A focus on platforms and content tells us little about the issues of campaign organization, staffing, and coordination of digital and field efforts around electoral strategy that have much more impact on electoral success.

A screencap of twitter.com/MittRomney/status/2409704... on 30 August 2012.

For one, both the Obama and Romney campaigns have created organizational structures that make the heads of their respective new media teams senior leadership. The Romney campaign learned this by studying Obama’s 2008 campaign, which was among the first efforts to organize a campaign in this way.This organizational role, in turn, helps integrate new media operations within the larger electoral strategy of the campaign. This is important because effective campaigns take up new media in accordance with their electoral goals, and investments in new media have to be evaluated in light of overall campaign strategy. There are very real differences between the presidential candidates, their parties, their supporter and donor bases, and electoral strategies — so much so that we should not expect them to have the same goals for, strategies of using, and investments in their use of new and social media.

During the 2008 cycle, for example, the Obama team took to new media early on, with the specific goal of using an array of tools to overcome the institutional advantages of Senator Hillary Clinton. For the campaign, this meant using new media as a fundraising and especially organizing tool in accordance with the larger electoral goal of expanding the electorate among groups favorable to Obama with historically low rates of turnout: youth and African Americans. Above all, it meant using new media to translate the incredible energy of supporters gathering around the candidate into resources that campaigns need: money, message, volunteers, and ultimately, votes. And yet, while this worked for Obama, other candidates with essentially the same tools could not inspire the same supporter mobilization. The story of the 2008 Obama campaign is neatly summed up in what Michael Slaby, the 2008 campaign’s chief technology officer and the 2012 campaign’s chief integration and innovation officer, said to me: “We didn’t have to generate desire very often. We had to capture and empower interest and desire…. We made intelligent decisions that kept it growing but I don’t think anybody can really claim we started something.”

A screencap of twitter.com/BarackObama on 30 August 2012.

In this light, the continual hope, exemplified in the Pew Study, for “transforming campaigning into something more dynamic, more of a dialogue,” and the inevitable let down when this does not occur, is a case of our democratic aspirations placing undo expectations on campaigns. Campaigns have very concrete metrics for success given electoral institutions. Campaigns are temporal entities with defined goals: garnering the resources and ultimately the votes necessary to win elections. They are not about democratic renewal, although certainly that can happen. Furthermore, much of the discourse calling for dialogue ignores a fundamental fact: the goals of campaigns and their supporters on social media are often closely aligned around defeating opponents. Supporters embrace tasks and respond to one-way messaging because their goal is to win on election day, not remake democratic processes.

Indeed, a close look at the networked tools campaigns across the aisle are now routinely using in 2012 reveals an emphasis on electoral gain, and integrating tools within larger electoral strategy. The story of the last decade in electoral campaigning has been both about a reinvestment in old fashioned, shoe leather campaigning coupled with new data infrastructures designed to more efficiently and effectively coordinate volunteers and leverage their time, efforts, and social networks. As Rasmus Nielsen has analyzed in his recent book, in the face of widespread practitioner recognition of the diminishing returns of broadcast television ads, fragmented audiences, narrowly decided contests, and social science findings, campaigns have increasingly enlisted humans as media through what he calls “personalized political communication.” Campaigns deploy field volunteers on the basis of voter modeling and targeting supported by a vast, national data infrastructure stitched together from a host of public (voter registration, turnout, and real estate records), commercial (credit card information, magazine subscription lists), party (historical canvass data), and increasingly social network data.

A mobile phone screen cap of facebook.com/mittromney on 30 August 2012.

Leveraging people as media in the field complements the ways in which campaigns enlist supporters as the conduits of strategic communications to their strong and weak ties online. Campaigns seek to utilize the social affordances of platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to create what I call new “digital two step flows” of political communication, where official campaign content circulates virally through networks of supporters. On one level, geographic-based volunteering in supporters’ communities is now supported by networked devices, such as the Obama Dashboard volunteer platform that creates teams based on location, and mobile apps that display local voter contact targets and scripts for contacting them. On another, through networked media far-flung affinity, professional, and social ties can now serve as channels of political communication designed to mobilize donors and online volunteers. Campaigns believe that political communication coming from supporters contacting voters through their geographic and social networks is more persuasive.Alongside the fashioning of supporters into media and their social networks into channels, campaigns have developed sophisticated “computational management” practices that leverage media as internal and external coordination devices. New media is a closed loop; every expenditure can be tracked in terms of its return on investment given the ability to generate real time results of supporters’ interactions with networked media. If creating digital two step flows remains more art than science as campaigns struggle to make content go viral, optimizing web content and online advertising is data-driven to probabilistically increase the likelihood that supporters will take the actions campaigns want them to. Optimization is based around continually running experimental trials of web content and design in order to probabilistically increase the likelihood of desired outcomes. This means campaigns vary the format, colors, content, shapes, images, and videos of a whole range of email and website content based on the characteristics of particular users to find what is most optimal for increasing returns. In 2008, for example, the Obama campaign created over 2,000 different versions of its contribution page, and across the campaign optimization accounted for $57 million dollars, which essentially paid for the campaign’s general election budgets in Florida and Ohio.

At the same time, while television advertising has dominated campaign expenditures for much of the last half century, campaigns are increasingly investing in online advertising, which is premised on being able to access new sources of behavioral, demographic, and affinity data that allows for the more sophisticated targeting and tailoring of political messages. Campaigns can match online IP addresses with party voter files, allowing them to target priority voters. Campaigns use this matching, along with behavioral, demographic, interest, and look-alike targeting (matching voters based on the characteristics they share with others with known political preferences), to deliver online ads for the purposes of list-building, mobilizing supporters to get involved, and persuading undecideds.

Despite the best attempts of staffers, campaigns remain messy, complicated affairs. While it would be easy to see things such as computational management and online advertising in Orwellian terms, the reality is that campaigns are continually creating and appropriating new tools and platforms because their control over the electorate is limited. Candidates still contend with intermediaries in the press, opponents engaging in their own strategic communications, and voters who have limited attention spans, social attachments, and partisan affiliations that mitigate the effects of even the most finely tailored advertising. Millions, meanwhile, refuse to engage in the process, a massive silent minority that campaigns only spend significant resources on if they have them. There must always be political desire that exists prior to any of these targeted communications practices, or else supporters and voters will tune them out like much else that is peripheral to their core concerns.

In the end, as another presidential general election takes shape, we see continuities in electoral politics in the face of considerable technological change.

Daniel Kreiss is Assistant Professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Kreiss’s research explores the impact of technological change on the public sphere and political practice. In Taking Our Country Back: The Crafting of Networked Politics from Howard Dean to Barack Obama (Oxford University Press, 2012), Kreiss presents the history of new media and Democratic Party political campaigning over the last decade. Kreiss is an affiliated fellow of the Information Society Project at Yale Law School and received a Ph.D. in Communication from Stanford University. Kreiss’s work has appeared in New Media and Society, Critical Studies in Media Communication, The Journal of Information Technology and Politics, and The International Journal of Communication, in addition to other academic journals. You can find out more about Kreiss’s research at http://danielkreiss.com or follow him on Twitter at @kreissdaniel

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

What is the Higgs boson?

On 4 July 2012, scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) facility in Geneva announced the discovery of a new elementary particle they believe is consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson, or ‘god particle’. Our understanding of the fundamental nature of matter — everything in our visible universe and everything we are — is about to take a giant leap forward. So, what is the Higgs boson and why is it so important? What role does it play in the structure of material substance? We’re celebrating the release of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ with a series of posts by science writer Jim Baggott over the next week to explain some of the mysteries of the Higgs.

By Jim Baggott

We know that the physical universe is constructed from elementary matter particles (such as electrons and quarks) and the particles that transmit forces between them (such as photons). Matter particles have physical characteristics that we classify as fermions. Force particles are bosons.

In quantum field theory, these particles are represented in terms of invisible energy ‘fields’ that extend through space. Think of your childhood experiences playing with magnets. As you push the north poles of two bar magnets together, you feel the resistance between them grow in strength. This is the result of the interaction of two invisible, but nevertheless very real, magnetic fields. The force of resistance you experience as you push the magnets together is carried by invisible (or ‘virtual’) photons passing between them.

Matter and force particles are then interpreted as fundamental disturbances of these different kinds of fields. We say that these disturbances are the ‘quanta’ of the fields. The electron is the quantum of the electron field. The photon is the quantum of the electromagnetic field, and so on.

In the mid-1960s, quantum field theories were relatively unpopular among theorists. These theories seemed to suggest that force carriers should all be massless particles. This made little sense. Such a conclusion is fine for the photon, which carries the force of electromagnetism and is indeed massless. But it was believed that the carriers of the weak nuclear force, responsible for certain kinds of radioactivity, had to be large, massive particles. Where then did the mass of these particles come from?

In 1964, four research papers appeared proposing a solution. What if, these papers suggested, the universe is pervaded by a different kind of energy field, one that points (it imposes a direction in space) but doesn’t push or pull? Certain kinds of force particle might then interact with this field, thereby gaining mass. Photons would zip through the field, unaffected.

One of these papers, by English theorist Peter Higgs, included a footnote suggesting that such a field could also be expected to have a fundamental disturbance — a quantum of the field. In 1967 Steven Weinberg (and subsequently Abdus Salam) used this mechanism to devise a theory which combined the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces. Weinberg was able to predict the masses of the carriers of the weak nuclear force: the W and Z bosons. These particles were found at CERN about 16 years later, with masses very close to Weinberg’s original predictions.

By about 1972, the new field was being referred to by most physicists as the Higgs field, and its field quantum was called the Higgs boson. The ‘Higgs mechanism’ became a key ingredient in what was to become known as the standard model of particle physics.

Jim Baggott is author of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ and a freelance science writer. He was a lecturer in chemistry at the University of Reading but left to pursue a business career, where he first worked with Shell International Petroleum Company and then as an independent business consultant and trainer. His many books include Atomic: The First War of Physics (Icon, 2009), Beyond Measure: Modern Physics, Philosophy and the Meaning of Quantum Theory (OUP, 2003), A Beginner’s Guide to Reality (Penguin, 2005), and A Quantum Story: A History in 40 Moments (OUP, 2010). Read his previous blog post “Putting the Higgs particle in perspective.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

So what is ‘phone hacking’?

Over the past two years there has been much furore over journalists accessing the voicemail of celebrities and other newsworthy people, particularly the scandal involving Milly Dowler. As a result of the subsequent police investigation, ‘Operation Weeting’, some 24 people have since been arrested and the first charges were brought by the Crown Prosecution Service in July 2012 against eight people, including Rebekah Brooks and Andy Coulson. The leading charge was one of conspiracy “to intercept communications in the course of their transmission, without lawful authority.” But what does ‘phone hacking’ mean and has the CPS got it right?

The charge, under section 1 of the Criminal Law Act 1977, relates to an offence under the ominously worded Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (‘RIPA’), section 1(1). The RIPA is primarily concerned with the powers of law enforcement agencies to investigate criminality by listening into phone calls and other types of covert surveillance. The Act also criminalises the interception of communication by others, including journalists.

When drafting the 2000 Act, one of the objectives was to update the law of interception to reflect developments in modern telecommunication systems and services, especially email. One element of that reform was to recognise that telecommunication systems sometimes store messages on behalf of the intended recipient, to enable them to collect the message at their convenience. In such circumstances, according to section 2(7) of the RIPA, the communications shall be considered still ‘in the course of transmission’. One key issue to be decided in the forthcoming ‘phone hacking’ cases is therefore whether listening to somebody’s voicemail message falls within this exception.

So why does uncertainty arise? The issue for the court to decide is whether a distinction should be made between accessing voicemail messages that have been listened to by the intended recipient and those that have yet to be heard. In the former case, it can be argued, the communication is at an end and the voicemail service is simply being used as a storage medium. As such, no act of ‘interception’ has taken place.

Answering this seemingly simple question of interpretation is made more complex as a result of an apparent change of position on the part of the CPS. In November 2009, Keir Starmer QC, Director of Public Prosecutions, gave evidence before the Culture, Media and Sports Committee about the meaning of section 2(7). He argued, on the basis of the observations of Lord Woolf CJ in R (on the application of NTL) v Ipswich Crown Court [2002], that the provision should be interpreted narrowly, such that a message was only ‘in the course of transmission’ until it had been collected by the intended recipient. This statement led to a very public disagreement between Keir Starmer and John Yates, the then Acting Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan police, who argued for a wide interpretation of section 2(7). By July 2011, however, the CPS had committed a volte-face and decided to “proceed on the assumption that a court might adopt a wide interpretation.”

As a consequence of this legal uncertainty, there would appear to be a very real chance that the coming prosecutions may fail. As well as the considerable waste of police resource that would result, and the adverse impact on public confidence, this reliance on the crime of ‘interception’ seems unnecessary, as suggested by the moniker ‘phone hacking’. An alternative charge would seem to be available under section 1 of the Computer Misuse Act 1990, for ‘unauthorised access to computer material’. This was the original ‘hacking’ statute, and the offence carries the same maximum tariff as that for unlawful interception, i.e. two years imprisonment. There can be no question that a voicemail service is held on a ‘computer’, while it would seem relatively easy to show that the perpetrator, which can include both the private investigator and the requesting journalist, knew that such access was unauthorised.

The rationale for pursuing journalists for ‘intercepting’ rather than ‘hacking’ phones is not immediately clear, but the outcome of the forthcoming cases may simply represent another sorry stage in the long running saga of newspaper phone hacking.

Ian Walden is Professor of Information and Communications Law at the Centre for Commercial Law Studies, Queen Mary, University of London. His publications include Computer Crimes and Digital Investigations (2007), Media Law and Practice (2009) and Telecommunications Law and Regulation (4th ed., 2012). Ian is a solicitor and Of Counsel to Baker & McKenzie.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

You may also like: Can Ignorance Ever Be An Excuse?

September 2, 2012

To let you appreciate what sort of consul he professes himself to be

On 2 September 44 BC, Cicero launched into the first of the most blistering oratorical attacks in political history, attacks which ultimately cost him his life. The following is an excerpt of the Second Philippic, a denunciation of Mark Antony, from the Oxford World’s Classic Political Speeches. Do we hear echoes of contemporary political rhetoric in these harsh tones?

Conscript fathers, I have something to say in my own defence and much to say against Marcus Antonius. As to the former theme, I ask you to listen to me sympathetically as I defend myself; as to the latter, I shall myself make sure that you pay me close attention while I speak against him. At the same time I beg of you: if you agree that my whole life and particularly my public speaking have always been characterized by moderation and restraint, then please do not think that today, when I give this man the response he has provoked, I have forgotten my true nature. I am not going to treat him as a consul any more than he has treated me as a consular. And whereas he cannot in any sense be regarded as a consul, either in his private life, or in his administration of the state, or in the manner of his appointment, I am beyond any dispute a consular.

So to let you appreciate what sort of consul he professes himself to be, he attacked my consulship. Now that consulship, conscript fathers, was mine in name only: in reality it was yours. For what decision did I arrive at, what action did I take, what deed did I do other than by the advice, authority, and vote of this order? And now do you, as a man of wisdom, not merely of eloquence, dare to criticize those proceedings in the very presence of those by whose advice and wisdom they were transacted? But who was ever found to criticize my consulship except you and Publius Clodius? Indeed, Clodius’ fate awaits you, just as it did Gaius Curio, since you have at home the thing which did for both of them.

Cicero. Source: NYPL.

Marcus Antonius does not approve of my consulship. But Publius Servilius approved of it — of the consulars of that time I name him first, because his death is the most recent. Quintus Catulus approved of it, a man whose authority will always remain a living force in this country. The two Luculli, Marcus Crassus, Quintus Hortensius, Gaius Curio, Gaius Piso, Manius Glabrio, Manius Lepidus, Lucius Volcacius, and Gaius Figulus approved of it. Decimus Silanus and Lucius Murena, who were then consuls-elect, approved of it. Like the consulars, Marcus Cato approved of it — a man who in taking leave of life showed great foresight, especially in that he never saw you become consul. But Gnaeus Pompeius above all approved of my consulship in that, the moment he saw me on his return from Syria, he embraced me and congratulated me, saying that it was thanks to me that he would once again set eyes on his country. But why do I mention individuals? A packed senate approved my consulship so strongly that there was no one who did not thank me as if I were his parent, and who did not put it down to me that he was still in possession of his life, his property, his children, and his country.

But since the many distinguished gentlemen whom I have just named are all now lost to our country, I turn to the living. Out of the body of consulars, two are still with us. The gifted and judicious Lucius Cotta proposed a thanksgiving in the most complimentary terms for those very actions which you criticize, and the consulars I have just named, together with the entire senate, accepted the proposal — an honour which I was the first civilian since the foundation of our city to receive. Lucius Caesar, your uncle — what eloquence, what resolution, what authority he showed as he denounced his sister’s husband, your stepfather! He was the man you should have had as your guide and mentor in all your decisions throughout your life — and yet you chose to model yourself on your stepfather rather than your uncle! Although unrelated to him, I as consul accepted Caesar’s guidance — but did you, his sister’s son, ever ask his advice on any public matter at all?

Immortal gods, whose advice, then, does he ask? Those fellows, I suppose, whose very birthdays we are made to hear announced. ‘Antonius is not appearing in public today.’ ‘Why ever not?’ ‘He is giving a birthday party at his house outside the city.’ ‘Who for?’ I will name no names: just imagine it’s now for some Phormio or other, now for Gnatho, now for Ballio even. What scandalous disgrace, what intolerable cheek, wickedness, and depravity! Do you have so readily available to you a leading senator, an outstanding citizen, and never consult him on matters of public interest — while all the time consulting people who have nothing of their own, but sponge off you instead?

Your consulship, then, is a blessing, and mine was a curse. Have you so lost your sense of shame, together with your decency, that you dare to say such a thing in the very temple where I used to consult the senate in its days of greatness, when it ruled the world — but where you have now stationed thugs armed with swords? But you even dared (is there anything you would not dare?) to say that in my consulship the Capitoline path was packed with armed slaves. I was, I suppose, preparing violence to force the senate to pass those wicked decrees! You despicable wretch — whether you do not know what happened (since you know nothing of anything good) or whether you do — you who talk with such utter lack of shame before such men as these! When the senate was meeting in this temple, did any Roman equestrian, did any young noble except you, did anyone of any class who recalled that he was a Roman citizen fail to come to the Capitoline path? Did anyone fail to give in his name? And yet there were neither enough clerks nor enough registers to record all the names that were offered. After all, traitors were admitting to the assassination of their homeland, and were compelled by the testimony of their accomplices, by their own handwriting, and by the almost audible sound of the words they had written to confess that they had conspired to set fire to the city, to massacre the citizens, to devastate Italy, and to destroy their country. In such a situation, who would not be roused to defend the national security — particularly at a time when the senate and people of Rome had the sort of leader under whom, if we had a similar leader now, you would have met the same fate that those traitors did?

Cicero (106-43 BC) was the greatest orator of the ancient world and a leading politician of the closing era of the Roman republic. Political Speeches presents nine of his speeches that reflect the development, variety, and drama of his political career. Among them are two speeches from his prosecution of Verres, a corrupt and cruel governor of Sicily; four speeches against the conspirator Catiline; and the Second Philippic, the famous denunciation of Mark Antony, which cost Cicero his life. These new translations by D. H. Berry, Senior Lecturer in Classics, University of Leeds, preserve Cicero’s oratorical brilliance and achieve new standards of accuracy. A general introduction outlines Cicero’s public career, and separate introductions explain the political significance of each of the speeches. This edition also provides an up-to-date scholarly bibliography, glossary and two maps.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

September 1, 2012

Textual Variants in the Digital Age

The editing of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in the form in which we now read it took many decades of work by a number of different scholars, but there is as yet no readily available edition that takes account of all the different versions in which the Canterbury Tales survives. Some of this is purely pragmatic. There are over 80 surviving manuscripts from before 1500 containing all or some parts of the Tales (55 of these are complete texts or were meant to be). The great Oxford edition of the nineteenth century, by Walter William Skeat, relies mostly on a single manuscript (‘Ellesmere’) with corrections from only six other texts. The edition in which most people have read the Tales in recent decades, the Riverside Chaucer (also printed in the UK by Oxford), also relies on Ellesmere, although it consults many more manuscripts than six to establish its base text. This is also Jill Mann’s practice in the recent Penguin edition of the Tales. But what if someone wanted to edit Chaucer from all the manuscripts, accounting carefully for all the variations? What if a student simply wanted to get some sense of what sorts of variation were possible in a manuscript culture, where every copy of a text was different because every such copy had to be hand-written?

The editing of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in the form in which we now read it took many decades of work by a number of different scholars, but there is as yet no readily available edition that takes account of all the different versions in which the Canterbury Tales survives. Some of this is purely pragmatic. There are over 80 surviving manuscripts from before 1500 containing all or some parts of the Tales (55 of these are complete texts or were meant to be). The great Oxford edition of the nineteenth century, by Walter William Skeat, relies mostly on a single manuscript (‘Ellesmere’) with corrections from only six other texts. The edition in which most people have read the Tales in recent decades, the Riverside Chaucer (also printed in the UK by Oxford), also relies on Ellesmere, although it consults many more manuscripts than six to establish its base text. This is also Jill Mann’s practice in the recent Penguin edition of the Tales. But what if someone wanted to edit Chaucer from all the manuscripts, accounting carefully for all the variations? What if a student simply wanted to get some sense of what sorts of variation were possible in a manuscript culture, where every copy of a text was different because every such copy had to be hand-written?

Since 1940 such curiosity could be satisfied in John Manly and Edith Rickert’s seven-volume Text of the Canterbury Tales ‘on the basis of all the known manuscripts’. But this edition has been under a cloud ever since it first appeared because it used all these manuscripts to try to work back to the ‘original’ text of the Tales (the process is called ‘recension’), and accidentally demonstrated in the process that this is not possible. There probably never was such an original, not least because Chaucer never finished the Tales, and even if there had been, there are too many small errors in the extant manuscripts to eliminate all of them. A more practical obstacle for any curiosity about the nature of this variation, however, is the form in which Manly and Rickert had to present the information they assembled. Take just the 10th line of the portrait of the ‘clerk of Oxford’ in the General Prologue of the Tales, for example, in which the narrator tells us his library consisted of

Twenty bookes clad in black or reed

This line can be found on p. 14 of volume 3 of this edition, and if one looks down to the bottom of the page a set variants is displayed in this way:

or] and Ha4 –a –b* (-) cd* (-) Bo2 En3 Fi PS Py Ra3 Tc1

‘Or’ identifies the word for which variants exist; the close bracket marks the start of those variants; ‘and’ is the word that sometimes occurs instead of ‘or’; and the alphanumeric soup that follows ‘and’ consists of the identifiers (‘sigla’) for the manuscripts in which this variant can be found. As it happens, this list is a simplified account of the variants for this line in all of the manuscripts that Manly and Rickert consulted — what it seemed necessary to mention in order to justify the text they printed. The full variation of these variants is printed in the ‘corpus of variants’ that fills the last three volumes of this edition, and the entry for the line I have just quoted (on page 24 of volume 5) is as follows:

bookes] goode b. Ps2 | clad] clothed Ha4 Ii; clodde Ht | blak] whit Cx1 Fi N1 Py S12 Tc1 | or ] and a Bo2 c Cx1 D1 Fi En3 Ha2 Ha4 Ht Ii Ld1 Mg Mm N1 Ps Py ra3 Ry2 Se Tc1 | reed] in r. Dd Ht Ry1

This list shows that some manuscripts say ‘goode bookes’ rather than only ‘bookes’, that some say ‘clodde’ or ‘clothed’ rather than ‘clad’, and that some say ‘white’ rather than ‘black’. None of these differences is hugely consequential (though the last of them is certainly interesting), but the combination of triviality (to meaning) and complexity (of form) will itself be enough to explain why Manly and Rickert place them in separate volumes, or why an editor such as Skeat would narrow the range of manuscripts from which he chose his readings to 7, or why he too would limit the variants he printed to no more than the readings he corrected (few enough to fit in a narrow column at the bottom of each page). In fact, for the line on the clerk’s books, there is nothing at all at the foot of Skeat’s page, although the line printed is slightly different from Manly and Rickert’s:

Twenty bokes, clad in blak or reed

The difference consists of the spelling ‘bokes’ in place of ‘bookes’, and the insertion (this would have been Skeat’s editorial decision) of a comma. More important than the nature or size (or consequence) of this difference, however, is the way that the print technology that has determined how we read Chaucer for so long must always tend toward Skeat’s simplicity. Mann’s Penguin edition, the most user-friendly we now have — and therefore destined to be the most read in future years — does not include variants at all. The Riverside Chaucer includes some variants in its ‘Textual Notes’ but it moves all of these to the back of the book. Complicate things as much as Manly and Rickert did with all the variants, and no one will read your text.

Online editions open out new possibilities for marrying simplicity to completeness. One can imagine a hypertext edition in which all the variants associated with a particular word, phrase, or line, would simply appear as a cursor passed over the text (much as the contents of a footnote will appear in a bubble when the cursor moves across the reference in a text written in Word). The paradox seems stark: only when the words of the text are lifted entirely away from any page can the complexity of the page be fully preserved and disseminated. And yet it is not a paradox if we think of such a hypertext as finally overcoming the limits of print technology. No longer shackled by the limits of mechanical reproduction, the digital age gives us a text that, precisely because it lacks physical form is supple enough to represent the complexity of that form.

Such a hypertext is not yet with us because entering the variants in the marked-up form that would make them available in this way is itself a huge undertaking (digital technology is never more powerful than the information human labor can provide for it). But an online edition such as Oxford’s is already sufficient to the task of making the complex simple in all the ways that a medieval text with many variants requires. If books must separate variants from the text of the Tales in precise proportion to their detail (include many and they must be placed at the back of the book; include all of them and you need several more books), but simply give yourself the virtual page in which an infinite amount of information may un-scroll in one column while the text sits happily, unmoved, in another, and all the variants of a text can accompany every word and phrase and line of that text at all times. Such an edition can also put the complexity of these variants in the hand of everyone — student and scholar alike — who has a computer and an internet connection.

Many libraries own neither Manly-Rickert nor Skeat. And even the copyright library in which I write these remarks, the Cambridge University Library, requires that the volumes of Manly-Rickert be fetched to its ‘West Room’, but keeps Skeat in its Rare Books Room (because it was published before 1900). To bring Manly-Rickert’s variants to Skeat’s text they must be couriered by a member of staff (a reader cannot transport them from West to Rare Books Room himself). Since neither set of volumes circulates I could not bring them home to compare with my own copies of the Riverside and Mann’s Penguin edition. These common editions should have been available on the open shelves (and I could have found them there and brought them to the Rare Books room myself) but, as it happened, on the day I was gathering these volumes together, the Penguin edition of the Tales was checked out.

None of these movements is anything more than tedious, and careful scholarship moves greater mountains of inconvenience very day. And yet these are obstacles that might well defeat the undergraduate or post-graduate who simply wanted to explore what variation might exist in the text of the Tales. And a scholar focused on the variants in the text of the Tales might more easily go beyond those variants (to thoughts about the patterns they display; to theories about the nature or reliability of the edited text itself) if it was easier to consult them. What everybody who reads the Canterbury Tales has lacked up until this point, in other words, is a way of accessing all the richness of the material form in which the Tales survives as a constant and necessary concomitant of a readable text. The representational power of digital technology enriches the works we have long known and loved by just such elaborations.

Christopher Cannon is a Professor of English at New York University and member of the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online editorial board. He teaches Middle English literature at New York University. He took his BA, MA and PhD at Harvard University, and then taught, successively, at UCLA, Oxford, and Cambridge. His PhD dissertation and first book, The Making of Chaucer’s English (1998) analyzed the origins of Chaucer’s vocabulary and style using an extensive database and purpose-built software to demonstrate that Chaucer owed much more to earlier English writers than had been recognized before. His second book, on early Middle English, The Grounds of English Literature (2004), developed these discoveries by means of a new theory of literary form. Most recently he has written a cultural history of Middle English.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online is coming soon. To discover more about it, view this series of videos about the launch of the project or read a series of blog posts on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

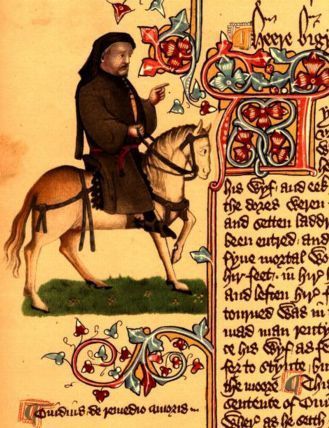

Image credit: Image of Chaucer as a pilgrim from Ellesmere Manuscript in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. The manuscript is an early publishing of the Canterbury Tales. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

August 31, 2012

Understanding Olympic design

After attending the “Because” event at the Wolff Olins office on July 4th, I was once again reminded of the big disconnect that lies between designers and their public. Wolff Olins is the firm that designed the London 2012 brand, a multifaceted design campaign that included much more than the London 2012 logo. Readers may remember the numerous complaints that the logo generated. As my research revealed, this was caused partly due to International Olympic Committee (IOC)’s restrictions and the corporate unwillingness to allow for the full application of what might be seen as a “no logo” campaign.

Wolff Olins proposed an open-source framework that would integrate the public by providing a design language that could be shaped into new forms and messages. The designers’ intention was to “hand over some tools that would allow people to make everything they wanted.” Design would be “off the podium, onto the streets.” But neither the public nor the broader designers’ community were ready to accept that the Wolff Olins team showed no compliance to the usual set of corporate instruction and that what they were trying to achieve lied beyond the creation of beautiful forms.

London 2012 event. Photo by Gary Etchell. Used with permission. All rights reserved. http://www.flickr.com/photos/gary8345...

The designers’ goal was to evoke an effect similar to that of the Mexico 1968 design: a visual language designed by Lance Wyman that was not only appropriated by the counter-Olympic movement, but also marked future visual languages developed by local designers in Mexico. In a way, Wolff Olins’ design succeeded in its adaptability, even though its multiple viral deconstructed versions that appeared on the streets and online were meant to primarily express conspiracy and protest, or even a disdain for the very visual language that the designers provided (and which these “dissidents” are now using).

But why would designers today strive for openness and participation? And why should IOC, London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (LOCOG), or the general public be indifferent or even hostile to these intentions? After all, are there any designs that would meet the aspirations of all stakeholders: Olympic organizers, designers, and their multiple publics? The Olympics, as indeed most public events, are complex platforms that bring to the surface deep social conflicts and generate heated debates about the notion of public good. The new temporary or permanent configurations that are designed for the Olympics express these tensions and often become the targets of opposing voices.

Everyone today recognizes that the modern Olympics only partly concern sports. Few, though, are aware of the multiplicity of the design engagements that are mobilized for their realization. Being characterized as something between urban festivals and quasi-religious events, the Olympics have a strong ceremonial character that design generates. Hundreds of designers are mobilized to create a series of objects (logos, posters, uniforms, mascots, souvenirs) that are indispensable for the Olympic ensemble. This may seem to some a contemporary distortion to the original 19th century idea of the modern Olympics’ founder, Pierre De Coubertin, but Coubertin was keenly aware of the importance of design for the identity of the Games. He designed what has been credited as the most recognizable logo in the word, the Olympic rings, and spent considerable energy in prescribing the ceremonial characteristics of the event, with writings on subjects that ranged from attention to lighting and decoration, to specifications on the architecture of the venues.

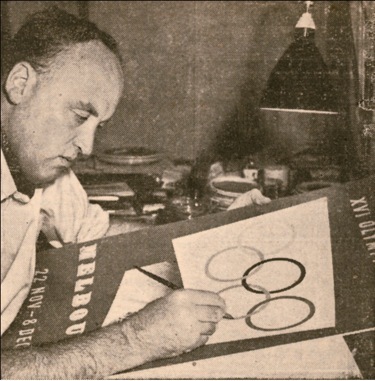

Photograph in newspaper (unspecified) of Richard Beck working on the design for the Olympic poster. This proto-version differs from the final design, particularly in its typography. Collection: Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, 92/1256–1/4. Used with permission.

The design for the Olympics has been an overlooked subject in the fields of design history and Olympic studies alike. Olympic design’s role as an instrument of modernity becomes obvious, for instance, in the way British athletes’ uniforms were designed for the early Opening Ceremonies, expressing but also helping to shape the identity of modern Britain. The Melbourne 1956 poster designer, Richard Beck, abandoned the neoclassical body of the male athlete that characterized earlier Olympic posters for a non-figurative composition along the tenets of modern design.As it has become only too obvious with the current case of London, in late modernity the Olympics are also an opportunity for new infrastructure projects and major real estate enterprise, which leave a debatable legacy to the host-city. Planners, architects, and urbanists play a major role in this process, as well as those who sponsor, lease, or invest in the projects in the longue durée of the post-Olympic era. The design for the Mexico 1968 Olympics had significant ideological implications for the social segregation that marked the future of Mexico City. The architecture of the Athens 2004 Olympics is emblematic of ‘instant monumentality’ and a lack of legacy planning that has characterized many modern Olympics.

At the same time, the high visibility, budget, and scale of the Olympics have provided designers with opportunities to realize ambitions that are not possible through ordinary projects, and to envision ideas that are often too advanced for their times. Katsumi Masaru for instance insisted in compiling a design manual for the Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games (a set of prescriptions that would secure the unified application of the graphics, and thus a cohesive Olympic image), even though he knew too well that it could hardly be applied in the Tokyo Olympics per se. Indeed it was completed just before the start of the Games leaving nevertheless an important legacy for all forthcoming Olympics for which a design manual became a staple. Should we similarly expect that the “no logo” idea of the London 2012, with its openness and lack of corporate compliance, is signaling a new paradigm shift?

Jilly Traganou is Associate Professor in Spatial Design Studies at the School of Art and Design History and Theory, at Parsons The New School for Design in New York. She has published widely in academic journals, has authored The Tokaido Road: Traveling and Representation in Edo and Meiji Japan (Routledge, 2003) and co-edited Travel, Space, Architecture (Ashgate, 2009). She is currently working on a new book Designing the Olympics: (post-) National Identity in the Age of Globalization. Traganou has recently edited a special issue titled “Design Histories of the Olympic Games” for the Journal of Design History, where she also serves as Reviews Editor.

The new issue of the Journal of Design History titled “Design Histories of the Olympic Games” introduces the Olympics as a multifaceted design operation that generates diverse, often conflicting, agendas. Who creates the rhetorical framework of the Olympics, and how is this expressed or reshaped by design? What kind of ambitions do designers realize through their engagement with the Olympics? What overall purposes do the Olympics and their designs serve? ‘The Design Histories of the Olympic Games’ brings together writings by a new generation of scholars that cross the boundaries between traditional disciplines and domains of knowledge. Some of the articles look at the role of Olympic design (fashion design and graphic design) in representing national identity. Other articles look at the interconnected area of architecture, urbanism and infrastructure and the permanent legacy that these leave to the host city. You can view more on the Journal of Design History’s Design Histories of the Olympic Games Pinterest board too.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Read more blog posts about the London 2012 Summer Olympic Games.

Finding the right word

How do you choose the right word? Some just don’t fit what you’re trying to convey, either in the labor of love prose for your creative writing class, or the rogue auto-correct function on your phone.

Can you shed lacerations instead of tears? How is the word barren an attack on women? How do writers such as Joshua Ferris, Francine Prose, David Foster Wallace, Zadie Smith, and Simon Winchester weigh and inveigh against words?

We sat down with Katherine Martin and Allison Wright, editors of the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus, to discuss what makes a word distinctive from others and what writers can teach you about language.

Writing Today, the Choice of Words, and the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

Reflections in the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Use and Abuse of a Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

Katherine Martin is Head of US Dictionaries at Oxford University Press. Allison Wright is Editor, US Dictionaries at Oxford University Press.

Much more than a word list, the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus is a browsable source of inspiration as well as an authoritative guide to selecting and using vocabulary. This essential guide for writers provides real-life example sentences and a careful selection of the most relevant synonyms, as well as new usage notes, hints for choosing between similar words, a Word Finder section organized by subject, and a comprehensive language guide. The third edition revises and updates this innovative reference, adding hundreds of new words, senses, and phrases to its more than 300,000 synonyms and 10,000 antonyms. New features in this edition include over 200 literary and humorous quotations highlighting notable usages of words, and a revised graphical word toolkit feature showing common word combinations based on evidence in the Oxford Corpus. There is also a new introduction by noted language commentator Ben Zimmer.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language, lexicography, word, etymology, and dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

How and why do myths arise?

Myth: A Very Short Introduction

By Robert A. Segal

It is trite to say that one’s pet subject is interdisciplinary. These days what subject isn’t? The prostate? But myth really is interdisciplinary. For there is no study of myth as myth, the way, by contrast, there is said to be the study of literature as literature or of religion as religion. Myth is studied by other disciplines, above all by sociology, anthropology, psychology, politics, philosophy, literature, and religious studies. Each discipline applies itself to myth. For example, sociologists see myth as something belonging to a group.

Within each discipline are theories. A discipline can harbor only a few theories or scores of them. What makes theories theories is that they are generalizations. They presume to know the answers to one or more of the three main questions about myth: the origin, the function, or the subject matter.

The question of origin asks why, if not also how, myth arises. The answer is a need, which can be of any kind and on the part of an individual, such as the need to eat or to explain, or on the part of the group, such as the need to stay together. The need exists before myth, which arises to fulfill the need. Myth may be the initial or even the sole means of fulfilling the need. Or there may be other means, which compete with myth and may best it. For example, myth may be said to explain the physical world and to do so exceedingly well — until science arises and does it better. So claims the theorist E. B. Tylor, the pioneering English anthropologist.

Function is the flip side of origin. The need that causes myth to arise is the need that keeps it going. Myth functions as long as both the need continues to exist and myth continues to fulfill it at least as well as any competitor. The need for myth is always a need so basic that it itself never ceases. The need to eat, to explain the world, to express the unconscious, to give meaningfulness to life – these needs are panhuman. But the need for myth to fulfill these needs may not last forever. The need to eat can be fulfilled through hunting or farming without the involvement of myth. The need to express the unconscious can be fulfilled through therapy, which for both Sigmund Freud and his rival C. G. Jung is superior to myth. The need to find or to forge meaningfulness in life can be fulfilled without religion and therefore without myth for secular existentialists such as Albert Camus.

For some theorists, myth has always existed and will always continue to exist. For others, myth has not always existed and will not always continue to exist. For Mircea Eliade, a celebrated Romanian-born scholar of religion, religion has always existed and will always continue to exist. Because Eliade ties myth to religion, myth is safe. For not only Tylor but also J. G. Frazer, author of The Golden Bough, myth is doomed exactly because myth is tied to religion. For them science has replaced religion and as a consequence has replaced myth. “Modern myth” is a contradiction in terms.

The third main question about myth is that of subject matter. What is myth really about? There are two main answers: myth is about what it is literally about, or myth symbolizes something else. Taken literally, myth is usually about gods or heroes or physical events like rain. Tylor, Eliade, and the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski all read myth literally. Myth taken literally may also mean myth taken historically, especially in myths about heroes.

The subject matter of myth taken symbolically is open-ended. A myth about the Greek god Zeus can be said to symbolize one’s father (so Freud), one’s father archetype (so Jung), or the sky (so nature mythologists). The religious existentialists Rudolf Bultmann and Hans Jonas would contend that the myth of the biblical flood is to be read not as a explanation of a supposedly global event from long ago but as a description of what it is like for anyone anywhere to live in a world in which, it is believed, God exists and treats humans fairly.

To call the flood story a myth is not to spurn it. I am happy to consider any theory of myth, but not the crude dismissal of a story or a belief as a “mere myth.” True or false, myth is never “mere.” For to call even a conspicuously false story or belief a mere myth is to miss the power that that story or belief holds for those who accept it. The difficulty in persuading anyone to give up an obviously false myth attests to its allure.

Robert A. Segal is Sixth Century Chair in Religious Studies at the University of Aberdeen. He is the author of Myth: A Very Short Introduction and of Theorizing about Myth. He is presently at work editing the Oxford Handbook of Myth Theory. He directs the Centre for the Study of Myth at Aberdeen.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Who Was Who online, part of Who’s Who online, has granted free access for a limited time to the entries for the philosophers and scholars mentioned in the above article.

Image credit: Thetis and Zeus by Anton Losenko, 1769. Copy of artwork used for the purposes of illustration in a critical commentary on the work. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

August 30, 2012

What’s so super about Super PACs?

Back in January we published a short glossary of the jargon of the presidential primaries. Now that the campaign has begun in earnest, here is our brief guide to some of the most perplexing vocabulary of this year’s general election.

Nominating conventions

It may seem like the 2012 US presidential election has stretched on for eons, but it only officially begins with the major parties’ quadrennial nominating conventions, on August 27–30 (Republicans) and September 3–6 (Democrats). How can they be called nominating conventions if we already know who the nominees are? Before the 1970s these conventions were important events at which party leaders actually determined their nominees. In the aftermath of the tumultuous 1968 Democratic convention, however, the parties changed their nominating process so that presidential candidates are now effectively settled far in advance of the convention through a system of primaries andcaucuses, leaving the conventions themselves as largely ceremonial occasions.

Purple states, swing states, and battleground states

These three terms all refer to more or less the same thing: a state which is seen as a potential win for either of the two major parties; in the UK, the same idea is expressed by the use of marginal to describe constituencies at risk. The termbattleground state is oldest, and most transparent in origin: it is a state that the two sides are expected to actively fight over. Swing state refers to the idea that the state could swing in favor of either of the parties on election day; undecided voters are often called swing voters. Purple state is a colorful metaphorical extension of the terms red state and blue state, which are used to refer to a safe state for the Republicans or Democrats, respectively (given that purple is a mixture of red and blue). Since red is the traditional color of socialist and leftist parties, the association with the conservative Republicans may seem somewhat surprising. In fact, it is a very recent development, growing out of the arbitrary color scheme on network maps during the fiercely contested 2000 election between George W. Bush and Al Gore.

Electoral vote

What really matters on election day isn’t the popular vote, but the electoral vote. The US Constitution stipulates that the president be chosen by a body, theelectoral college, consisting of electors representing each state (who are bound by the results of their state election). The total number of electors is 538, with each state having as many electors as it does senators and representatives in Congress (plus 3 for the District of Columbia). California has the largest allotment, 55. With the exception of Maine and Nebraska, all of the states give their electoral votes to the winner of the popular vote in their state on a winner-takes-all basis, and whichever candidate wins the majority of electoral votes (270) wins the election. This means it is technically possible to win the popular vote but lose the election; in fact, this has happened three times, most recently in the 2000 election when Al Gore won the popular vote, but George W. Bush was elected president.

Veepstakes

The choice of a party’s candidate for vice president is completely in the hands of the presidential nominee, making it one of the big surprises of each campaign cycle and a topic of endless media speculation. The perceived jockeying for position among likely VP picks has come to be known colloquially as theveepstakes. The 2012 veepstakes are, of course, already over, with Joe Biden and Paul Ryan the victors.

Super PAC

If there is a single word that most characterizes the 2012 presidential election, it is probably this one. A super PAC is a type of independent political action committee (PAC for short), which is allowed to raise unlimited sums of money from corporations, unions, and individuals but is not permitted to coordinate directly with candidates. Such political action committees rose to prominence in the wake of the 2010 Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission and related lower-court decisions, which lifted restrictions on independent political spending by corporations and unions. Advertising funded by these super PACs is a new feature of this year’s campaign.

501(c)(4)

It isn’t often that an obscure provision of the tax code enters the general lexicon, but discussions of Super PACS often involve references to 501(c)(4)s. These organizations, named by the section of the tax code defining them, are nonprofit advocacy groups which are permitted to participate in political campaigns. 501(c)(4) organizations are not required to disclose their donors. This, combined with the new Super PACs, opens the door to the possibility of political contributions which are not only unlimited but also undisclosed: if a Super PAC receives donations through a 501(c)(4), then the original donor of the funds may remain anonymous.

The horse race

As we’ve discussed above, what really matters in a US presidential election is the outcome of the electoral vote on November 6. But that doesn’t stop commentators and journalists from obsessing about the day-to-day fluctuations in national polls; this is known colloquially as focusing on the horse race.

The online magazine Slate has embraced the metaphor and actually produced an animated chart of poll results in which the candidates are represented as racehorses.

This article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Katherine Connor Martin is a lexicographer in OUP’s New York office.

Oxford Dictionaries Online is a free site offering a comprehensive current English dictionary, grammar guidance, puzzles and games, and a language blog; as well as up-to-date bilingual dictionaries in French, German, Italian, and Spanish. The premium site, Oxford Dictionaries Pro, features smart-linked dictionaries and thesauruses, audio pronunciations, example sentences, advanced search functionality, and specialist language resources for writers and editors.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language, lexicography, word, etymology, and dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers