Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1022

September 15, 2012

Political dramaturgy and character in 2012

In the wake of the party conventions, the shape of the Presidential contest has crystallized. Shocking to pundits and purveyors of conventional wisdom, Barack Obama has stretched his lead, narrowly in the national polls, more decisively in the critical swing states. Campaigns are all about hope and bluff. Though “no one will hear a discouraging word” from the Romney campaign, the writing is on the wall. The reason is not the actual state of the economy or nation. It’s about the state of our political drama, our symbolic and emotional selves.

From the Greeks and American Founding Fathers to modern political scientists, democracy has been misunderstood as an exercise in rationality. Voters are portrayed as employing unencumbered intellects, as looking at issues and weighing their interests, as having the ability to understand “truth” and see through the “distortions” of the other side. But this simply isn’t the way society works.

Voters don’t decide whom to vote for by weighing their objective costs and benefits. They are not calculating machines, but emotional and moral human beings. Searching for the meanings of things, they want to make sense of political life, working out a grand narrative of where we’ve been, where we are now, and where we’re going in the future.

Candidates are characters in this social drama, casting themselves as heroic protagonists and opponents as wearing black hats. Citizen-audiences evaluate these shape-shifting performances, making identifications, not calculations. They support characters who seem life-affirming and hopeful, and oppose those who appear evil and dangerous.

Those auditioning for Presidential power aim to become collective representations, symbols that embody the best qualities of citizens and nation. If a candidate succeeds in symbolizing “America” for enough voters, he will be allowed to direct the government.

In 2008, Barack Obama succeeded in creating a truly inspiring character, becoming a collective representation that compelled mass identification. In the first two years of his presidency, the emotional fusion binding this character to the left and center became attenuated. In some part such loosening was inevitable. The symbolic intensity of Obama-character could not possibly be sustained as Obama-President manipulated the machinery of government. There were also self-inflicted wounds. Obama’s political autobiography was all about healing the polarizing wounds of the sixties, but he deeply underestimated the difficulty of creating a vital center inside the Congress and state. During the year-long health care debate, post-partisan compromise was demonstrated to be only a figment of the President’s imagination; he came away empty-handed, without a shred of Republican support. While Obama-character played the fiddle of reconciliation, the Tea Party made America burn. “Obama” now seemed cool and out of touch, and later acknowledged neglecting narrative for policy. The Republicans smashed the Democrats in 2010.

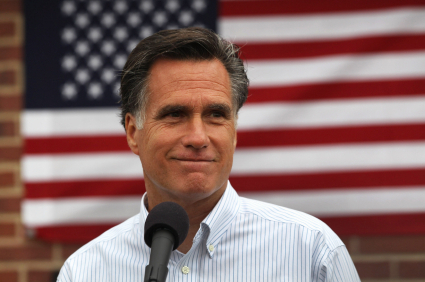

After that cathartic triumph, the emotional energy of millions of angry, disappointed Americans seemed there for the Republicans to take. They had only to find a vessel to hold it. Failing to rise to this dramaturgical moment, the Republicans emerge from months of primary with a cipher, not a symbol. Mitt Romney possessed a mile long CV and a well-oiled political machine, but nary a drop of charisma. He sees himself as a tool, not a vessel, an instrument of economic management rather than a vehicle for emotional and moral representation.

Incapable of symbolizing, Romney performs the role of the problem-solving businessman. But voters wrap practical promises inside gauzy cultural blankets. What matters is the character of the promiser and his story. These are what citizens can feel. They can’t scientifically evaluate the validity of his promise. Is candidate Romney one of us? Is he an up-from-the-bootstraps, self-made American hero, like Johnson, Nixon, or Clinton? Is he a warrior hero like Ike or Bush, Sr.? Is he an aristocratic hero sacrificing personal comfort to work for the American people, like Teddy Roosevelt, FDR, or JFK?

It doesn’t matter who Mitt Romney is really, only what his character seems to be. With Obama’s help, Romney-character emerged as Bain Capital(ist), the quarter-billionaire who won’t tell us about his taxes and parked his hidden money offshore. Romney may have brain power, but he lacks symbolic soul. Romney-character signifies self over community, a glad hander who’ll tell us what we want to hear, not what he deeply believes.

Obama-character presents a sharp contrast. Whatever his practical failings, he is still seen as idealistic and honest, devoted to helping others rather than feathering his own nest. The plot which this admirable character has inhabited, however, has terribly let us down. The 2008 campaign was poetry in motion, a hero promising salvation; President Obama governed in prose, with no relief in sight.

Would Americans see Obama-character as a good-hearted flop? The RNC performance team would have had it so. The dramaturgical challenge for DNC organizers was shifting the chronology so that Obama-character could be a hero again. The new narrative saw Obama as inheriting, not creating, our awful economic mess – “750,000 jobs were lost in January 2008 alone!” Since then, he’s been furiously digging us out. No human being could have done a better job, Bill Clinton assured us. In his acceptance speech, the President proclaimed we are only in the middle of the recovery, a story of suffering that will not be redeemed for several more years. But then there will be salvation, and American greatness will be restored.

The bounce from the DNC indicates Obama-character regained some traction with the center, and the coiled power of his invisible ground game suggests some re-fusion with the activist left. At least for now, Obama-character can no longer be a hero, but he can be represented as working heroically for our side.

Over the next sixty days, opportunities for performative failure and success remain — most conspicuously in the presidential debates, where ritual and dramaturgy, not rational argument, reign. There will also be unscripted events that can catch a character by surprise. During the financial crisis in September 2008, John McCain seemed to fall off the stage.

At this point in the “Performance of Politics 2012,” all signs point to the success of the Democratic play. Victory is not in the economic stars, but in our symbolic selves.

Jeffrey C. Alexander is the Lillian Chavenson Saden Professor of Sociology and co-Director of the Center for Cultural Sociology at Yale University. One of the world’s leading social theorists, he is the founder of the “strong program” in cultural sociology, which brings concepts from the humanities into social science in order to understand the centrality of meaning in modern social life. Among his recent books are The Meanings of Social Life: A Cultural Sociology (Oxford 2003), The Civil Sphere (Oxford 2006), The Performance of Politics: Obama’s Victory and the Democratic Struggle for Power (Oxford 2010), Performance and Power (Polity 2011), The Performative Revolution Egypt (Bloomsbury 2011), and Trauma: A Social Theory (Polity 2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credits:

U.S. President Barack Obama addresses Indiana residents during a town halll style meeting at Concord High School February 9, 2009 in Elkhart, Indiana. (Photo by Scott Olson) Image via EdStock, iStockPhoto.

Republican presidential hopeful Mitt Romney speaks with the media after visiting the Brewery Bar IV on June 20, 2011 in Aurora, Colorado. (Photo by John Moore) Image via EdStock2, iStockPhoto.

September 14, 2012

Theodore Roosevelt, family man as political strategy

Oxford University Press USA has put together a series of articles on a political topic each week for four weeks as the United States discusses the upcoming American presidential election, and Republican and Democratic National Conventions. Our scholars previously tackled the issue of money and politics, the role of political conventions, and the role of media in politics. This week we turn to the role of family in politics. The following is an excerpt from Lewis L. Gould’s Grand Old Party: A History of the Republicans on Theodore Roosevelt.

You will have hard work to keep the pace with Roosevelt and sometimes I fancy you must be frightened at the spirit you have helped to unchain.

—Eugene Hale

Theodore Roosevelt was forty-two years old when he became the twenty-sixth president of the United States. He had been a Republican since his boyhood, but his allegiance to the Grand Old Party was not that of a regular partisan. He had little interest in the protective tariff and was not a fan of businessmen or the process by which they made their money. Instead, as a member of the New York aristocracy, he saw his duty as representing the American people in their adjustment to the promises and perils of industrial growth.

For Roosevelt the Republicans were the party of constructive nationalism, and the new president believed that government power could be employed to enable all citizens to share in the bounty of an expanding economy. In time he would come to believe that some government regulation of the economy was also necessary. Democrats were the party of ineptitude and states’ rights who could be counted on to thwart the constructive work of Roosevelt and his party. While Roosevelt was adroit at the political maneuvering that allowed him to win the Republican nomination in 1904, over the long haul he was not skilled at persuading his fellow party members to follow his policies.

Where Roosevelt excelled was in the public conduct of his office. He governed with energy and excitement. For the first time the president became a celebrity in his own right, and the newspapers avidly followed the president’s frenetic schedule, the antics of his brood of young children, and the social life of his daughter from his first marriage, Alice Roosevelt. When a friend told him that his daughter’s lifestyle, which included a pet snake, fast cars, and many parties, needed restraint, Roosevelt replied, “I can be President of the United States, or I can control Alice. I can’t possibly do both.” Roosevelt was the first president to use his family in a conscious way to enhance his own appeal.

When law is part of the problem

The law is often an ass. More often than ever. Modern governments, their hands tied by the robber-barons of global finance, often try to assert their power with their feet: by kicking out at another supposed social problem with another big policy initiative. Usually they come up with an accompanying raft of new laws. Legislative incontinence prevails. Not only is much of the legislation futile and even counterproductive from the start, we are also left with ever more relics of now-forgotten reforms. Between 1997 and 2006, for example, more than 3000 new criminal offences were enacted for England and Wales, while only a tiny number were repealed. In spite of promises from the current government to turn over a new leaf, the trend towards throwing new laws at everything continues apace.

Most of us escape the consequences of this massive but pathetic display of governmental machismo only because the law is erratically enforced. This means that in two distinct ways we are not living under the rule of law in Britain today. First, there is so much law, touching on so many aspects of our lives, that it would be impossible for us to grasp it all, or to follow it even if we could grasp it. Even as a lawyer I can’t keep up with the politicians in their impotent zeal to put a stop to things. Second, we increasingly rely on petty officials such as tax inspectors and police officers to turn a blind eye to some violations while coming down hard on others. Since there is no way that all this junk law could be enforced, there is increasing pressure for it to be enforced selectively, and increasing latitude for the selection to be done by fear or favour. So big corporations can enjoy cozy relations with the police that are denied to those who inconveniently protest against corporate power. This kind of selectivity is also anathema to the rule of law. Under the rule of law, it shouldn’t be one law for the powerful and another for the rest of us. Even News International is pursued only because they made the silly mistake of upsetting some very big cheeses. You may say it was always thus. I don’t deny it. I only say that the huge expansion of legal regulation is part of what props it up so effectively today. So much law means lots of extra openings to enforce it unevenly, including for reasons that are dubious, shadowy, or downright corrupt.

The ideal of the rule of law is the ideal according to which it is the law that should rule. Some people (I call them ‘law and order types’) believe that we live under the rule of law only when everyone obeys the law. So student unrest in Parliament Square is as much of a threat to the rule of law as police brutality in quelling it. This makes it possible to justify the police brutality (although illegal) in terms of the rule of law itself — better a bit of summary punishment from the boys in blue than a whole lot of burnt-out cars. This is the symmetrical interpretation of the ideal; it condones the authorities in meeting illegality with illegality on a level playing field. Bernard Williams has some interesting things to say about this ‘level playing field’ in his posthumously published book In the Beginning Was the Deed. He thinks that a goverrnment that meets terror with terror fails in respect of what he calls the ‘Basic Legitimation Demand’. I agree. Such a government has ‘become part of the problem.’

So I favour, instead, the asymmetrical interpretation of the ideal of the rule of law. On this interpretation, the rule of law requires an unequal struggle between officialdom and the rest of us. The law should be such that ordinary people can obey it, whether or not they do. The rule of law is threatened when the law becomes so arcane, so vast, or so vague, that people can’t be guided by it even when they try. But the rule of law is also threatened, in a different way, when people can’t rely on the law to predict how officials will react to their breaches of it. It follows that officials, as distinct from ordinary people, need to follow the law scrupulously for the rule of law to survive. Their disobedience — including their fear or favour in upholding the law — is a threat to the rule of law in a way in which, or to an extent to which, ordinary law-breaking by you or me is not. We could put this in different terms by saying officials of the law have an obligation to obey the law that most of us don’t have. That is because, as officials of the law, they have an obligation to uphold the rule of law that the rest of us don’t have. We are the beneficiaries of the rule of law; they, when in official capacity, are its functionaries. We should laugh at stupid laws. They should uphold them.

This asymmetry creates an intriguing moral problem for the law, especially but not only the criminal law. On many occasions police officers, prosecutors, lawyers, and judges have a moral obligation to call me to account for breaking a law that, as they well know, I had no moral obligation to obey. I have written about some aspects of this particular moral problem in a couple of recent articles (‘Relations of Responsibility’ and ‘Criminals in Uniform’.) For those who are interested in such things I have also lately attempted a more abstract and general defence of the asymmetrical conception of the rule of law, showing how it connects with timeless philosophical puzzles about the very nature of law. It is a surprisingly short step from thinking about these timeless philosophical puzzles to thinking about the most severe delusions of our age, including the delusion that more law and more law-abidingness could help us to mitigate, maybe even to heal, the social ills of rapacious contemporary capitalism.

John Gardner is Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Oxford. He has also taught at Columbia, Princeton, Yale, the Australian National University, and the Universities of London, Texas, and Auckland. Called to the English Bar in 1988, he has been a Bencher of the Inner Temple since 2002. He is the author of Law as a Leap of Faith: And Other Essays on Law in General, in chapter eight of which he defends the ‘asymmetrical conception’ that he sketches here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles on law and politics on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Empathizing toward human unity

According to ancient Jewish tradition traced back to the time of Isaiah, the world rests upon thirty-six just men — the Lamed-Vov. For these men who have been chosen and must remain unknown even to themselves, the spectacle of the world is insufferable beyond description. Eternally inconsolable at the extent of human pain and woe, so goes the Hasidic tale, they can never even expect a single moment of real tranquility. From time to time, therefore, God himself, in an expansively sympathetic gesture designed to open their souls to Paradise, sets forward the clock of the Last Judgment, by exactly one minute.

There are several discernible meanings to this extraordinary tradition, one of which may offer some redemptive hope in relieving our sobering nearness to global catastrophe. Soon, we will have to create the unique conditions whereby each and every one of us is personally able to feel the excruciating anguish and dreadful portents of the Lamed-Vov. Then, we will be able to take the necessary steps back from defilement to sanctification. Faced with the ultimate choice between life and death, between “the blessing and the curse,” then shall we “choose life.”

How could we hope to endure, both as individuals and as nations, if we were to feel, with the same palpable pain and sorrow, the immeasurable distress of all others? Shall we imagine that the more-or-less consuming empathy we now display viscerally toward our closest relatives and friends could be extended, much more generally, to the very broadest possible radius of human affinities? Or perhaps, without the suffering Lamed-Vov as intermediaries, we couldn’t even begin to survive such a protracted torment.

There exists a pertinent dilemma, a most unenviable paradox. To survive as a species, we must first survive as individuals. But the most glaringly evident requirement of species survival – a sine qua non that calls for much deeper and wider expressions of human empathy — could simultaneously render each individual life unbearable.

Sometimes, truth emerges through paradox. To survive, must we all have to first experience the terrible dizziness of the existentially irremediable? How shall we respond?

In the end, meaningful redemption is the core expectation of all societies on earth. The Swiss psychologist, Carl G. Jung, once remarked that “Society is the sum total of individual souls seeking redemption.” To redeem the whole world, he understood, we must unhesitatingly call forth certain indispensable metamorphoses. But, the “success” of these transformations would also place us squarely within a new and equally destructive trajectory of harms. It may be hard to understand that an imagined death can somehow sustain life. Still, all things move in the midst of death, and an individual life must always be recognized as an intended part of a larger whole.

It is unlikely that we may ever actually have to face up to this dilemma. After all, evidence abounds that the human capacity for empathy seems fixedly limited, and that for all practical purposes, we will need to construct our best global survival ideologies with substantially less ambitious assumptions in mind.

In the Jewish tradition, there are vital elements that appear to warn us against taking on too much of the suffering of others. Although Jews are certainly obligated to feel such suffering, to learn from, and be elevated by such torment (Toras Avraham), they must also guard against too much empathy. That is, strong feelings could occasion their own personal destruction. We may yet learn, from the instructive legend of the Lamed-Vov, not only that empathy is essential, but also that too much empathy is beyond human endurance.

Truth can emerge through paradox. It may also emerge from an awareness that, sometimes, reason alone is incapable of revealing to us what is most important. Such a keen awareness was deeply embedded in the thought of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, who, in the dreadfully serious matter now before us, would urge us to seek not “concepts of truth,” but “truth itself.” This is a strange, but still consequential, distinction.

In the fashion of his thoughtful Swiss colleague, Carl G. Jung, Sigmund Freud spoke frequently of “souls.” He understood that a mystery of eternity always hovers meaningfully above and beyond the temporal world. The deepest reality of human love and empathy, he already knew, whether or not as determinable manifestations of God’s love, can never be adequately elucidated through science, by rigorous analysis, or by consciously systematic thought. Rather, Freud argued, it may be discovered in virtually every element of our day-to-day reality, including even that which is manifestly impure.

To Rabbi Kook, a Divine redemption must finally be undertaken by and through the Jewish People. An integral part of such redemption must inevitably be a greater awareness of indispensable human unity. This therapeutic awareness, if undimmed, should ultimately give rise to the light of loving kindness, and ultimately, to forgiveness. In turn, a “lofty” soul is needed to first generate a greater awareness of human unity: “The loftier the soul, the more it feels the unity that there is in all.”

We may all learn from Rabbi Kook that empathy and hence justice can bring forth a vast healing, and that such feeling “flows directly from the holy depth of the wisdom of the Divine soul.” Rabbi Kook’s thinking doesn’t stand in any stark or self-conscious opposition to rational investigation, nor does it intend to oppose pure feeling to raw intellect. Instead, it identifies a usefully creative tension, between an abstract and too-formal intellectualism, and a distinctly promising form of reason, one that lies well beyond the normal limits of utterly abstract investigations.

Influenced and informed by Buddhism, Kook envisioned humankind with a natural evolutionary inclination to advance and perfect itself. The course of this human evolution, he surmised, must be directed toward a progressively increased spirituality. In the final analysis, he understood the Torah as a concrete manifestation of Divine Will here on earth.

In consequence, at some point, the people and State of Israel must play a cosmic and redemptive role in saving us all. This mending role, however, will be contingent upon first fulfilling many challenging expectations (mitzvot), fulfillments wherein the redemption of Israel can produce the redemption of all humanity. Here, Jewish nationalism is presented as much more than a highly-valued secular ideology. It is, rather, represented as a fully sacred phenomenon. This representation is worth bearing in mind by both Jews and gentiles, indeed, by all those who might intentionally be dismissive of Israel’s special place among the nations. As goes Israel, so shall go the world.

Louis René Beres was educated at Princeton (Ph.D., 1971), and is interested in special connections between traditional Jewish sources and Israeli security affairs. He is the author of ten major books and several hundred articles dealing with international relations and international law. Professor Beres was born in Zürich, Switzerland, at the end of the War, the only son of Viennese Jewish survivors. He is a regular contributor to OUP Blog.

If you are interested in the subject of Jewish philosophy, you may be interested in The Discipline of Philosophy and the Invention of Modern Jewish Thought by Willi Goetschel. Examining the thought of Spinoza, Moses Mendelssohn, Heinrich Heine, Hermann Cohen Franz Rosenzweig, Martin Buber, Margarete Susman, Hermann Levin Goldschmidt, and others, Goetschel highlights how the most philosophic moments of their works are those in which specific concerns of their “Jewish questions” inform the rethinking of philosophy’s disciplinarity in principal terms.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Keeping movies alive

Film: A Very Short Introduction

Film is considered by some to be the most dominant art form of the twentieth century. It is many things, but it has become above all a means of telling stories through images and sounds. The stories are often offered to us as quite false, frankly and beautifully fantastic, and they are sometimes insistently said to be true. But they are stories in both cases, and there are very few films, even in avant-garde art, that don’t imply or quietly slip into narrative. This story element is important, and is closely connected with the simplest fact about moving pictures: they do move.

Even the older meanings of the word ‘film’ – a membrane, a covering, a veil, an emanation – now seem to have something to do with moving pictures. Many people believe films are an instrument of illusion, an emphatic way of seeing what is not there; and this capacity has been both celebrated and condemned. ‘Like a movie’ mostly means like some sort of fairy-tale. But what about the reverse proposition: that more than any other invention film brings us close to the world as it actually is? ‘Photography is truth,’ a character says in a film by Jean-Luc Godard, ‘And cinema is the truth twenty-four times per second.’

In this short video, Michael Wood sets the scene by explaining what first made him fall in love with film:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Here, Michael muses on the mysterious and magical creation of movement in film, and embraces the filmic possibilities afforded by new technologies.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Finally, Michael explores the different ways in which we can view films and how this has altered our experience of creating – and watching – them.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Michael Wood is Charles Barnwell Start Professor of English and Professor of Comparative Literature at Princeton University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only cinema and television articles on the OUPblog via via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

September 13, 2012

The Joy of Sets

In recent days, the pro-mathematics portion of the Internet has been buzzing over the following paragraph, taken from the website of Christian publishing company A Beka Book:

Unlike the “modern math” theorists, who believe that mathematics is a creation of man and thus arbitrary and relative, A Beka Book teaches that the laws of mathematics are a creation of God and thus absolute….A Beka Book provides attractive, legible, and workable traditional mathematics texts that are not burdened with modern theories such as set theory.

As a result of recent legislative activity in the state of Louisiana, these curricular materials will now be supported with taxpayer money.

In more than a decade of socializing with creationists and other religious fundamentalists, I frequently encountered blinkered arguments about mathematics. This attack on set theory, however, was new to me. I cannot even imagine why anyone would think set theory is relevant to discussions of whether it is man or God who creates math. Perhaps the problem is that set theorists often speak a bit casually about infinity, which some people think is tantamount to discussing God. Alas, this line of criticism is too blinkered to take seriously.

Whatever their objection, they are really missing out on something great. Set theory is fascinating.

By a “set” we mean simply any collection of objects. You walk into a grocery store and see a pile of grapefruits over here and a pile of apples over there. A mathematician might then refer to the set of grapefruits on the one hand and the set of apples on the other. This provides a useful way of talking about all the apples (or grapefruits) combined as one unit, as opposed to discussing any specific apple (or grapefruit).

Of course, we can identify many other sets. We might wish to distinguish the set of Gala apples from the set of Granny Smiths. Or we might want to make a larger set by combining the set of apples and the set of grapefruits together to form part of the set of all fruit. For any description you would care to give, it is reasonable to talk about the set of all things that fit that description.

This seemed obvious, for example, to Gottlob Frege, a German mathematician/philosopher who did pioneering work in logic and set theory in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Bertrand Russell pointed out that this notion is fundamentally flawed. He first observed that some sets answer to their own descriptions while others don’t. The set of all grapefruits isn’t itself a grapefruit. Therefore, this set doesn’t contain itself among its members. On the other hand, the set of all abstract ideas is, indeed, an abstract idea. So it contains itself.

Russell now considered the set whose members are precisely the sets that are not contained within themselves. The set of all grapefruits is contained in Russell’s set, for example, while the set of all abstract ideas isn’t. He now wondered whether his set did or didn’t answer to its own description. If we suppose that it does so answer, then it must be contained within itself. But Russell’s set only contains sets that aren’t contained within themselves. This is a contradiction. You see, if we assume that Russell’s set answers to its own description then it both contains itself and doesn’t contain itself. Impossible.

Alas, the alternative assumption fares no better. If we suppose that Russell’s set doesn’t answer to its own description, then it must be among the sets that aren’t contained within themselves. But this is precisely the criterion you must satisfy to get into Russell’s set in the first place. Either way you have a contradiction, meaning this isn’t a properly defined set.

Nor is this the only way to get into trouble with sets. Consider the set of counting numbers {1, 2, 3, 4, …} that cannot be uniquely identified with fewer than two hundred characters. For example, a number such as 1000 can be identified by writing “ten multiplied by one hundred,” but I can do it more efficiently by writing “one thousand,” and more efficiently still by writing “ten cubed.”

Now, since there are only finitely many phrases having fewer than 200 characters, and infinitely many counting numbers, it is clear that my set must contain something. And since it must contain something, it must also contain a smallest number. (In the math biz, this curious fact of counting numbers is known as the “well-ordering principle.”) That smallest number in the set is therefore uniquely identified by the phrase, “The smallest counting number that cannot be described with fewer than two hundred characters.” But did I not just describe it with fewer than 200 characters? Prolonged consideration of such things can be harmful to your mental health.

Actually, my favorite application of the well-ordering principle is this: Consider the set of all the boring counting numbers. This set must have a smallest member, let us call it X. But then X is the smallest boring counting number, which makes it very interesting indeed! Surely this contradiction shows that all counting numbers are interesting?

Indeed they are. And sets are as well. Just don’t be too ingenious about how you define them.

Jason Rosenhouse is Associate Professor of Mathematics at James Madison University. His most recent book is Among The Creationists: Dispatches from the Anti-Evolutionist Front Lines. He is also the author of Taking Sudoku Seriously: The Math Behind the World’s Most Popular Pencil Puzzle with Laura Taalman and The Monty Hall Problem: The Remarkable Story of Math’s Most Contentious Brain Teaser. Read Jason Rosenhouse’s previous blog articles.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

How much do you know about the piano?

In its three centuries of existence, the piano has become one of the most popular instruments in the world. In a quick poll of our music social media team here at Oxford University Press, nine out of eleven of us have had piano training. (Of course, we are the music social media team, so our results may be a bit skewed from other departments!) To celebrate National Piano Month in the USA, we’ve put together a short quiz about the piano and its history. Good luck, and be sure to leave any fun piano facts you know in the comments.

Where did the name “piano” come from?

Who constructed the first working piano, before any other maker was even experimenting in this field?

True or false: On a piano, the naturals have always been white, and the sharps/flats have always been black.

Invented in the 18th century, a “square piano” was a small piano in a horizontal, rectangular case (a descendant of the clavichord in its shape and design). When did Steinway produce its last square piano?

What was the single most important development in the sound of the Romantic piano?

Automatic piano players were first developed at the end of the 18th century. At the peak of its production in 1923, what was the percentage of automatic pianos out of the total American output of pianos?

True or false: by 1969, Japanese production of pianos outstripped that of all other countries.

True or False: Beethoven and Chopin approved of the pianist’s right in a performance to make changes to the composition.

How much tension do the strings in a modern piano impose?

How long is a concert grand?

In the late 20th century, Fazioli made the largest grand in production. How long was it?

Who was the performer believed to first turn the piano sideways on the stage, so the audience could see his profile?

Who was the first performer to perform regularly in public from memory?

Steinway & Sons concert grand piano. Photo: © Copyright Steinway & Sons. Creative Commons License.

AND NOW THE ANSWERS:

Where did the name “piano” come from?

The instrument’s modern name is a shortened form from its first published description by Scipione Maffei in 1711—“gravecembalo col piano, e forte” (“harpsichord with soft and loud”)

Who constructed the first working piano, before any other maker was even experimenting in this field?

There seems to be no doubt that it was Bartolomeo Cristofori, a keeper of instruments at the Medici court in Florence. An inscription made by Federigo Meccoli (a court musician in Florence) in a copy of Gioseffo Zarlino’s Le istitutioni harmoniche states that the “arpi cimbalo del piano e forte” was invented by Cristofori in 1700.

True or false: On a piano, the naturals have always been white, and the sharps/flats have always been black.

False. On Johann Andreas Stein instruments from 1781 to 1783, the key slips for naturals were ebony and the sharps were made of dyed pearwood topped with bone or ivory.

Invented in the 18th century, a “square piano” was a small piano in a horizontal, rectangular case (a descendant of the clavichord in its shape and design). When did Steinway produce its last square piano?

Steinway, which had made its first uprights in 1862, produced its last square in 1888. Interesting fact: In 1904, the association of American piano manufacturers gathered together all the squares they could find at their meeting in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and burnt them in a bonfire.

What was the single most important development in the sound of the Romantic piano?

The most important development in the sound of the Romantic piano was the new emphasis on the sustaining (or damper) pedal. Up to the first quarter of the 19th century, the damper pedal was mostly regarded as a special effect.

Automatic piano players were first developed at the end of the 18th century. At the peak of its production in 1923, what was the percentage of automatic pianos out of the total American output of pianos?

56%

True or false: by 1969, Japanese production of pianos outstripped that of all other countries.

True. In the late 1970s, Yamaha alone was making more pianos than all American companies combined, with an output of about 200,000 annually, sold mostly in Japan.

True or False: Beethoven and Chopin approved of the pianist’s right in a performance to make changes to the composition.

False. While some believed that the pianist reserved the right to introduce minor changes in a performance, it is known that both Beethoven and Chopin objected to such practices. These practices still flourished.

How much tension do the strings in a modern piano impose?

Approximately 18 tons or 16,400 kg.

How long is a concert grand?

The concert grand is about 275 cm long.

In the late 20th century, Fazioli made the largest grand in production. How long was it?

It was 308 cm long.

Who was the performer believed to first turn the piano sideways on the stage, so the audience could see his profile?

Jan Ladislav Dussek (1760-1812)

Who was the first performer to perform regularly in public from memory?

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

All the answers to this quiz come from Oxford Music Online.

Alyssa Bender joined Oxford University Press as a marketing assistant in July 2011. She works on academic/trade history, literature, and music titles, and tweets @OUPMusic.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Grandfather Erasmus Darwin: written out of history

Darwin and evolution go together like Newton and gravity or Morse and code. The world, he wrote, resembles ‘one great slaughter-house, one universal scene of rapacity and injustice.’ Competitive natural selection in a nutshell? Yes – but that evocative image was coined not by Charles Darwin (1809-1882), but by his grandfather Erasmus (1731-1802). Although Charles Darwin is celebrated as the founding father of evolution, his neglected ancestor was writing about evolution long before he was even born.

Erasmus Darwin’s views on evolution, politics and religion were so controversial that he was written out of history for nearly two centuries. Historians are now restoring him to his rightful place as an Enlightenment philosopher who, like Karl Marx, believed that the point is to change the world, not just interpret it. Recent research makes it clear how well-known Darwin was among his political contemporaries. A radical campaigner for equality, he condemned slavery, supported female education and opposed conventional Christian ideas on creation. Energetic and sociable, this corpulent tee-totaller was, as Samuel Taylor Coleridge put it, “the most inventive of philosophical men…He thinks in a new train on every subject.”

On top of running a successful medical practice, Darwin was a Fellow of the Royal Society, promoted industrial innovation in the Midlands, and was famous for his long poems on gardens, technology and evolution. The father of fourteen children by two wives and his son’s governess, he envisaged a cosmos fuelled by sexual energy and dominated by a perpetual struggle between the powers of good and evil. Pledging his faith in progress, he maintained that mechanical inventions would make life better for everybody and that over the millennia, a minute strand of life had evolved into insects, animals and finally people.

Modern readers (including me) can find Darwin’s poetry excruciating, but it was extremely popular at the end of the eighteenth century. His first success was The Loves of the Plants (1789), in which he personified plants as sexy mythological characters. In page after page of clunky couplets and learned footnotes, Darwin exploited the erotic connotations of botanic reproduction. Unsurprisingly, not everybody approved of his ‘blushing beauties’ frolicking with a ‘wanton air’, or his ‘hundred virgins’ flirting with their Tahitian swains amidst ‘promiscuous arrows’ shot from Cupid’s bow. But despite – or perhaps because of – the protests from scandalized reactionaries, The Loves of the Plants established Darwin as one of Britain’s leading literary figures.

As Darwin grew older, his opinions became increasingly radical. Six months after the French Revolution, he exclaimed to the engineer James Watt, “Do you not congratulate your grandchildren on the dawn of universal liberty? I feel myself becoming all French both in chemistry and politics.” His next long poem, The Economy of Vegetation (1791), was a paean to progress, strikingly illustrated by William Blake, in which Darwin hymned industrial innovation and welcomed revolutionary politics. He also castigated slavery, paying tribute to his close friend Josiah Wedgwood (Charles Darwin’s other grandfather), who invented the world’s first political icon. Some plantation owners justified their cruelty by insisting that Africans had been created separately from Europeans. In contrast, the chained slave on Wedgwood’s plaque demonstrates his intrinsic humanity by asking a question – ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’

As Darwin grew older, his opinions became increasingly radical. Six months after the French Revolution, he exclaimed to the engineer James Watt, “Do you not congratulate your grandchildren on the dawn of universal liberty? I feel myself becoming all French both in chemistry and politics.” His next long poem, The Economy of Vegetation (1791), was a paean to progress, strikingly illustrated by William Blake, in which Darwin hymned industrial innovation and welcomed revolutionary politics. He also castigated slavery, paying tribute to his close friend Josiah Wedgwood (Charles Darwin’s other grandfather), who invented the world’s first political icon. Some plantation owners justified their cruelty by insisting that Africans had been created separately from Europeans. In contrast, the chained slave on Wedgwood’s plaque demonstrates his intrinsic humanity by asking a question – ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’

Compassionate and caring, Darwin knew that his patients adored him, but he found it hard to cope with pain. Having watched his first wife follow her father into alcoholism, he regarded drink as poison, imposing such a strong ban that his grandson could never touch a glass of wine without feeling guilty. Witnessing the suffering of local children with measles, he questioned the Christian concept of a beneficent God, concluding that evil arises as a consequence of the struggle for existence – but good triumphs because it is associated with the health and happiness essential for survival.

In his influential medical text, Zoonomia (1794), Darwin aimed to classify animal life and hence “to unravel the theory of diseases” by dividing them into four categories. Towards its end, Darwin dared to formulate an early version of evolution, suggesting “that in the great length of time, since the earth began to exist…warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament.” Parodists fantasised about vegetables growing wings, or people rubbing off their tails by sitting in caves. Facile jokes, maybe, but this book was deemed so subversive that it was put on the Vatican’s banned list. Evolution implied that the Bible was not literally true, and – potentially more dangerous – that the working classes might improve themselves to gain positions of power.

In his most contentious poem, The Temple of Nature (1803), Darwin developed his controversial ideas still further. This manifesto for progressive evolution reveals him to be a materialist who believed in natural laws of creation. To the horror of his critics, he insisted that life stemmed originally not from some divine spark infused by God, but directly from matter. His account shocked his readers but now sounds familiar: first appearing deep in the ocean, over successive generations living organisms gradually grew larger, acquiring new forms and functions until whales governed the seas, lions the land, and eagles the air. Human beings appeared last, the culmination of continuous development, related to lowly worms and insects as well as to apes.

In public, Charles Darwin denied his grandfather’s influence, but he read Zoonomia during his short-lived spell as a medical student at Edinburgh University. A decade later, after returning from his voyage around the world, he bought a small leather-bound notebook for jotting down his nascent ideas on transformation – and at the head of the first page, he underlined his title: Zoonomia. Over twenty years after that, he eventually released On the Origin of Species (1859), his landmark account of evolution by natural selection. Can it be mere coincidence that the sub-title of his grandfather’s book on evolution was The Origin of Society?

Patricia Fara is the Senior Tutor of Clare College, Cambridge, and she specializes in eighteenth-century history of science. Prize-winning author of Science: A Four Thousand Year History (Oxford University Press, 2009), her latest book is Erasmus Darwin: Sex, Science and Serendipity (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Fara will be speaking at Lichfield Literature Festival and Manchester Science Festival in October 2012. For more information visit the OUP events website. You can also see Fara explaining the important of sex in her biography of Erasmus Darwin over on the OUPAcademic YouTube channel.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography has granted free access for a limited time to Erasmus Darwin’s ODNB entry.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Erasmus Darwin, in public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Wedgwood Anti-Slavery Medallion. Used for the purposes of illustrating the work examined in this article. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

September 12, 2012

The oddest English spellings, part 21: Phony from top to bottom

I have written more than once that the only hope to reform English spelling would be by doing it piecemeal, that is, by nibbling away at a comfortable pace. Unfortunately, reformers used to attack words like have and give and presented hav and giv to the irate public. This was too radical a measure; bushes exist for beating about them. Several chunks of orthographic fat are crying to be cut off. One of them is the digraph ph. Dictionaries still cite phantasy and fantasy as admissible variants, but hardly anyone feels offended by fantasy, and probably no one is so steeped in classical scholarship as to advocate the spelling phantastic. (For more than a century there has been no progress in the movement of spelling reformers, but certain things should be said again and again for the record, even if they fall on deaf ears; “one doesn’t always fight to win.”)

Along with so many other learned spellings, ph appeared in English during the Renaissance. The digraph made sense (I am not saying “was needed”; it just made sense) in Greek words like orphan and physician and perhaps in names like Philip. But the scribes of that epoch inherited from their medieval predecessors the pernicious belief that the more letters one wrote in a word, the more the reader would be impressed. The easiest trick was to double consonants (and they doubled like a house on fire), but ph served their purpose too. So turph ‘turf’ and other monsters began to embellish manuscripts and books. The emergence of ph, apart from complicating spelling, introduced a good deal of confusion. For example, Anglo-French Estevene became Stephen (Greek Stephanos), while the shorter form and the family name (Steve, Stevenson) have v. However, don’t expect logic from English; Stephanie is spelled with ph and pronounced accordingly.

The history of nephew, with its puzzling ph, is full of adventures. Old English had the kin term nefa, a cognate of Latin nepos, which denoted “grandson; descendant.” Nefa too exhibited a broad spectrum of senses: “nephew; grandson; stepson; second cousin” (all of them united by the idea “less close than a son”). Nepos is the etymon of the corresponding words in the Romance group, including French. Middle English borrowed Old French neveu, though it could very well do with the native term, as happened in the other Germanic languages. Nefa continued into the sixteenth century (neve) and then disappeared. Nephew is a modern reflex of neveu, which, as can be seen, did not have either f or ph. The same holds for its Greek cognate anepsiós. We are at a loss to explain why scribes replaced v with ph in what eventually became nephew. Did this outburst of scholarly enthusiasm have a phonetic base? Despite the spelling, most people evidently pronounced nephew with v, so that in “Bev, you heard it, has a nephew” the italicized words made a perfect rhyme; this variant is still the most common one in British English.

According to the nearly universal opinion, f in nephew owes its existence to spelling. “Nefew” people would rhyme “Chef, you heard it, has a nephew.” However, the situation is far from clear. The example of original v being rendered by ph is unique. Phial and vial are etymological doublets, but then they are pronounced differently. The variation f ~ v in French words is extremely rare. In the eighteenth century some people pronounced prophecy as provecy, but in nephew v is primary, while in prophecy it is f. Also, f in nephew occurs in some British dialects, where the influence of book culture would be hard to expect. Additionally, most speakers of American English rhyme nephew with chef you, not with Bev you. This pronunciation was recorded in England in 1777, but it may have existed considerably earlier.

Since I teach linguistic courses, I regularly use the word diphthong. It takes me quite some time to explain the difference between monophthongs and diphthongs, because today’s students have no exposure to the basic concepts of phonetics (the spellchecker in my computer does not even recognize the word monophthong) and because the pronunciation of diphthongs varies from area to area. For example, in the Midwest we work from nine to five, in the south of the country they toil from nahn to fahv, and in London, Cambridge, and in many other parts of the United Kingdom one is kept busy from noin to foiv. Be that as it may, lie, lay, loud, low, and ploy are supposed to be pronounced with dipthongs. Once my students succeed in storing up this piece of valuable information, a losing battle begins against the pronunciation diphthong. The same substitution of p for f before th occurs in diphtheria, but I seldom hear that word and know about its phth problem only from books. The pronunciation dipthong was also known in England at the end of the eighteenth century, but French dipthongue testifies to the old age of the “substandard” variant in English. For comparison, check your pronunciation of phthisis, naphtha ~ naptha, and ophthalmologist. In Greek diphthoggós, di-, from dis-, means “twice,” and phthoggós, pronounced as phthongós, means “voice”; hence a sound consisting of two parts.

The Big Phony

To be sure, most English words beginning with ph- are of Greek origin or reached English via Greek (like Pharisee), but consider the interjections phew (spelled so, to avoid confusion with few?), phit, and phut in go phut “go bust” (phut, a twin of phit, is a loan from Hindustani; thus, Anglo-Indian). Supposedly, in words like phew ph designates the voiced partner of w, but does it? English borrowed fantasy ~ phantasy from Old French, where it was spelled with initial -f, though its ancestor was Latin phantasia (from Greek). The modern Romance languages also have f- (French fantasie, Italian fantasia), but Engl. fancy, a contraction of fantasy, has always been spelled with f-. In telephone, a late word in which one might risk deviating from the spelling of its ancient etymon, only Italian boldly (and wisely) chose the form telefone, while French and Spanish stick to ph. In the Germanic group, the Scandinavian languages, Dutch, and Frisian have abolished ph (except in some foreign proper names). By contrast, German has Phonetik “phonetics,” but Telefon. “All things considered,” the digraph ph is absolutely useless, and no one will weep if it goes away.Perhaps the height of absurdity is the spelling of the English adjective phony ~ phoney, popularized at the beginning of the twentieth century. Its source remains a matter of dispute. Most etymologists derive it from the cant word fawney “gilt ring,” ultimately from Irish. But there are other conjectures. Whatever the origin of this adjective, it did not come to English from Classical Greek, so why ph-? By association with phone?

Linguists make wide use of the concept of iconicity. The term refers to situations in which a word’s form corresponds to its meaning. For instance, longer is the comparative degree of long, and the word longer is indeed longer than long. Or you hear the verb crack, and its sound shape makes you think of cracking. Phoney illustrates the triumph of the iconic principle. The word means “false, counterfeit” and its spelling is phoney. It suggests Greek origin, but the suggestion is a hoax.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Soviet propaganda poster. “Study the Great Path of the Party of Lenin and Stalin!”. A relief depicting Lenin and Stalin, along with other Communist leaders, can be seen in the background, behind the inspired student of the Way of Lenin and Stalin. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Red families v. blue families revisited

The 2012 presidential election may turn on marriage. Not marriage equality, though President Obama may garner campaign contributions and enthusiasm from his endorsement of same-sex marriage, and Mitt Romney may garner financial support and emotional resonance from his opposition. And not concern about family instability, though the GOP’s grip on those concerned about family values is unlikely to loosen. Instead, this election may turn on the changing balance between the married and the unmarried. Marriage, especially when combined with parenthood, primes even committed liberals for more conservative views. A lot less marriage — with the Great Recession accelerating the move away from formal unions — increases Democratic chances.

The clash in perspectives is stark. Romney leads among married voters by 13%, 51-38. It will not be close. And while Romney lags far behind Obama among women, he is ahead by 10 points among married women. Among singles, however, Obama will win in a landslide. In a July poll, 54% of single voters favored President Obama compared to 34% for Mitt Romney, and single women (who constitute 26% of the population) were almost twice as likely to favor Obama as Romney. Obama’s lead with this group could increase; a fifth of single women are still undecided, one of the largest undecided groups in the population.

Some of the differences in preference reflect age; young people are less likely to be married and more likely to be Democratic. Some reflect race. African-Americans are more likely to be single and their support for Obama is close to unanimous. But the figures also reflect something else: the emergence of marriage as a marker of class and political perspectives.

Marriage rates in the United States have been profoundly influenced by the increase in economic inequality. Over the last thirty years, only college graduate men have gained in income, all other males have lost ground. In addition, employment stability has steadily worsened for men, declining for working class men since the eighties and other men more recently. In the last ten years, only the very top of the income ladder has continued to see their circumstances improve. The result has been a decline in marriage, but not one that has been evenly distributed.

One of the dramatic changes over the last thirty years has been the growing class division that underlies family formation. In the baby boom fifties, the elite and the working class both saw unplanned pregnancies and shot gun marriages increase. During the seventies, marriage rates declined, divorce increased, and birth rates plunged for the country as a whole. Starting in the nineties, however, families’ patterns diverged. The salaries for college graduates rose sharply, while the gender gap in incomes for the group increased. All but the wealthiest men found two incomes to be a major advantage in making it to the middle class. During the same period, college graduate men and women increasingly postponed marriage into the late twenties and beyond. The net result: college graduates became less like to marry non-grads. Both men and women placed more emphasis on the incomes of potential spouses. The larger number of high income men sought to choose a spouse from the relatively smaller group of high income women. Divorce rates for the group fell back to the rates of the early thirties — before no-fault divorce, the sexual revolution, or the widespread availability of the pill. The non-marital birth rates of college graduate whites stayed at 2%. And college graduates, the group that led the way into the sex revolution and the women’s movement, became marginally more conservative about family values.

Something very different happened to the rest of the country. Blue collar wages stagnated. Male employment instability increased. The gendered wage gap narrowed, decreasing most for high school dropouts and more modestly for the middle of the educational and income spectrum. As this happened, marriage rates fell, divorce rates increased, and non-marital births skyrocketed. Today, for African-American high school drop-outs, the non-marital birth rate is 96%. Sociologist Bill Wilson explained that in urban ghettos in the nineties, marriageable women outnumbered marriageable men by two-to-one. The result, as sociologists Marcia Guttentag and Paul Secord predicted almost 30 years ago, depressed the marriage rates not only of unemployed men, but of everyone else. With relatively few “good men,” the desirable men could enter into sexual relationships on terms of their choosing. The women, recognizing the unfavorable odds, came to distrust the men. They were slow to commit, more interested in immediate returns (the high priced dinner at a fancy restaurant or the contribution to the children’s winter coats), and warier about men generally. The men responded by becoming that much more willing to cheat or to move on. Marriage rates plummeted.

Today this dynamic characterizes not only minorities and the poor, but increasing segments of the middle. Greater income inequality has meant more men at the top, chasing a relatively smaller group of high status women, and more men at the bottom, who are for all practical purposes unmarriageable. That leaves more women and fewer men in the middle. Moreover, the men in the middle, faced with stagnating wages and less stable employment, have become less reliable partners. The loss of employment tends to produce higher rates of substance abuse and domestic violence. These traits make white working class males risky as marital partners. The remaining men with decent incomes find that they can play the field, and as they do so the more their potential partners become wary of them and of marriage.

The figures on the change in attitudes are stunning. Today, over 40% of the moderately educated say that “marriage has not worked out for people they know” in comparison with approximately 53% of the least educated but only 17% of the high educated. The number of fourteen-year-olds being raised in two parent families has increased for college graduates and fallen for everyone else. The net result: the working class is increasingly likely to reside in households that don’t consist of married biological parents. Such voters either vote Democratic or are ripe for conversion.

Does this mean that demography seals the deal for Obama? Not quite, for at least two reasons. First, while marriage affects political views, so does region. As we argued in Red Families v. Blue Families, the more traditionalist (read “red”) parts of the country interpret these trends through an ideological lens that calls for a doubling down on traditional values. This part of the country still produces high rates of marriage, followed by high rates of divorce and remarriage, and GOP support. In every state, income correlates with marriage rates and conservative views, but voters stay conservative (and more likely to marry) farther down the income ladder in red states. Second, those who are married and well-off vote. More economically marginal singles are less likely to get to the polls. The rhetoric of family is important to both political parties, but today’s political efforts are more focused on energizing the base and suppressing the opposition than creating dialogue that might produce shared values.

President Obama has reached out to single women, and they were critical to his election in 2008. If this group were to gain a voice proportionate to its numbers, then the support for more liberal policies is likely to increase. The revolution cometh.

Naomi Cahn and June Carbone are the authors of Red Families v. Blue Families: Legal Polarization and the Creation of Culture. Naomi Cahn is the John Theodore Fey Research Professor of Law at George Washington University Law School, a Senior Fellow at the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, and a member of the Yale Cultural Cognition Project, for which she and her co-investigators have received outside funding to conduct research on public attitudes towards gay and lesbian parenting. She is the author of Test Tube Families and the co-author of several other books, including a leading family law textbook. June Carbone is the Edward A. Smith/Missouri Chair of Law, the Constitution and Society at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Professor Carbone writes extensively about the legal issues surrounding marriage, divorce, and family organization, especially within the context of the recent revolutions in biotechnology. She is the author of From Partners to Parents: The Second Revolution in Family Law and co-author of the third edition of Family Law, with Leslie Harris and the late Lee Teitelbaum.

Oxford University Press USA has put together a series of articles on a political topic each week for four weeks as the United States discusses the upcoming American presidential election, and Republican and Democratic National Conventions. Our scholars previously tackled the issue of money and politics, the role of political conventions, and the role of media in politics. This week we turn to the role of family in politics. Read the previous post in this series: “Work-life balance and why women don’t run.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Young couple in bed. Photo by 101dalmatians, iStockphoto.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers