Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1024

September 10, 2012

Religion’s “return” to higher education

This fall about ten million undergraduate students will be heading back to America’s 2500 four-year colleges and universities, and they will be attending schools that are significantly more attuned to religion than they were ten or twenty or thirty years ago. Today’s students encounter religion in a wide variety of forms and settings, both on campus and off. They participate in traditional religious activities, they take classes about the history and sociology of culture wars and religious extremism, they interact with friends from diverse religious backgrounds, and they experiment with different forms of personal spirituality. Religion has “returned” to higher education, and the scope and nature of the learning taking place on campuses today is being enriched by this development.

We use the word “return” in quotes when referring to religion because the religion that is returning to higher education is a new kind of religion. In the past, religion usually meant historic religion or what is sometimes called “organized” religion. Many of the Ivies and older universities had been founded for the purpose of training students as ministers, and Christian or Judeo-Christian values and beliefs retained their strong influence on many colleges and universities until well into the twentieth century. But by the last half of the 20th century, secularization had become the academic norm, and religion was intentionally shunted aside, relegated to the private worlds of individuals.

In the last two or three decades religion in America has changed. Religion in America is now pluriform, a term we use to refer to the fact that American religion is now both pluralistic (because it includes all of the world’s historic religions) and spiritually brackish (meaning the boundary line between what is religious or spiritual and what is not religious has been thoroughly blurred). Some atheists may describe themselves as spiritual, and those who are non-religious (about 30% of the traditional-college-age population) often actively seek a religious-like sense of grounding, purpose, and meaning in their lives. As for trying to restrict religion to some kind of purely private or personal dimension of life, the terrorist attacks of 9/11 halted that myth once and for all.

Almost everyone now agrees that religion plays a major role in just about every aspect of American and global culture. For the past five years we have studied the ways colleges and universities are responding to religion’s return. At Harvard, it meant debating the inclusion of religion in general education requirements, while MIT appointed the first-ever Chaplain to the Institute. At the University of North Dakota, “spiritual wellness” was added to the list of major educational goals, and on dozens of campuses space was set aside for Muslim prayer rooms.

Based on conversations with hundreds of faculty, students, and administrators at colleges and universities as varied as Penn State, Vassar, and Brigham Young University, we have isolated six religious questions that are central to higher education. The first two questions deal with “historic religion” (i.e. traditional organized religion), the next two questions focus on “public religion,” and the last two are related to “personal religion” (i.e. spirituality):

What should an educated person know about the world’s religions?

What are appropriate ways to interact with those of other faiths?

What assumptions and rationalities — secular or religious — shape the way we think?

What values and practices — religious or secular — shape civic engagement?

In what ways do the personal convictions of students and faculty enter into the teaching and learning process?

How might colleges and universities point students toward lives of meaning and purpose?

These questions capture a mix of knowledge-based items (like religious literacy) and more reflective concerns about how religion functions in the world and in individual lives. Devoting time and energy to answering these questions will strike some critics as a luxury that simply can’t be afforded when college costs are soaring, student debt is mounting, and graduates are not getting jobs. But higher education in America has always been about more than jobs and about more than the merely practical. It has also been about understanding oneself and the world. In today’s religiously pluriform era, it may be that these “softer” competencies are precisely the ones that colleges and universities cannot afford to ignore.

Douglas “Jake” Jacobsen (Ph.D., History of Christianity, University of Chicago) and Rhonda Hustedt Jacobsen (Ed.D., Social Foundations of Education, Temple University), members of the faculty at Messiah College, are co-directors of the Religion in the Academy Project and co-authors of No Longer Invisible: Religion in University Education (Oxford, 2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: This building is Stuart Hall, in the main quadrangle of the University of Chicago campus. Photo by peterspiro, iStockphoto.

Jericho: The community at the heart of Oxford University Press

We’re delighted to announce that the Oxford University Press Museum, based at OUP’s Oxford publishing office, reopens today following extensive refurbishment. Archivist Martin Maw celebrates the occasion by taking a look at the historic links between OUP and Jericho, the local area.

By Martin Maw

Almost 200 years ago, Oxford University Press relocated its printing house to the area known as Jericho in Oxford. The neighbourhood’s history has been closely connected to the Press ever since. In the 19th century its streets were home to hundreds who worked at Oxford’s printing house and bindery, and the close family ties in the area formed what was almost a village inside the growing city.

The Press is much older than Jericho itself; Oxford University has been involved with the book trade since the 15th century. Earlier print shops were set up in Broad Street in the centre of Oxford, at the Sheldonian Theatre and the Clarendon Building. When these became too small for its business, building work began in Jericho in the 1820s at what is today Walton Street. Construction was overseen by two architects: Daniel Robertson (who allegedly worked best after two bottles of sherry, and had to be transported around the Press site in a wheelbarrow) and Edward Blore. The new printing house was finished in 1830, and looked out to the north over the orchards and meadows that flanked the canal.

This landscape soon changed, as the neighbourhood began to mushroom around the Press. Never a planned community, Jericho quickly became a nest of houses and pubs with a bad reputation. The area already had a deprived air about it; Walton Street was home to the Victorian workhouse, on a plot of land known as Rats and Mice Hill. The Printer to the University, Thomas Combe (1796-1872), felt the area needed a moral makeover.

THE PRESS BUILDING IN JERICHO, 19TH CENTURY

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

THOMAS COMBE AND STAFF, C.1870

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

THE PRESS QUADRANGLE, EARLY 20TH CENTURY

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

INSIDE THE PRINT SHOP, EARLY 20TH CENTURY

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

ST BARNABAS' CHURCH IN JERICHO, AS SEEN FROM OUP, 1955

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MUSEUM TODAY

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

');

');tid('spinner').style.visibility = 'visible';

var sgpro_slideshow = new TINY.sgpro_slideshow("sgpro_slideshow");

jQuery(document).ready(function($) {

// set a timeout before launching the sgpro_slideshow

window.setTimeout(function() {

sgpro_slideshow.slidearray = jsSlideshow;

sgpro_slideshow.auto = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.nolink = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolinkpage = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.pagelink="self";

sgpro_slideshow.speed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.imgSpeed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.navOpacity = 25;

sgpro_slideshow.navHover = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.letterbox = "#000000";

sgpro_slideshow.info = "information";

sgpro_slideshow.infoShow = "S";

sgpro_slideshow.infoSpeed = 10;

// sgpro_slideshow.transition = F;

sgpro_slideshow.left = "slideleft";

sgpro_slideshow.wrap = "slideshow-wrapper";

sgpro_slideshow.widecenter = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.right = "slideright";

sgpro_slideshow.link = "linkhover";

sgpro_slideshow.gallery = "post-28704";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbs = "";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbOpacity = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.thumbHeight = 75;

// sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.spacing = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.active = "#FFFFFF";

sgpro_slideshow.imagesbox = "thickbox";

jQuery("#spinner").remove();

sgpro_slideshow.init("sgpro_slideshow","sgpro_image","imgprev","imgnext","imglink");

}, 1000);

tid('slideshow-wrapper').style.visibility = 'visible';

});

Thankfully, Combe was in a financial position to accomplish it. Appointed in 1838, he subsequently earned a fortune through the University’s paper mill at nearby Wolvercote. Without any immediate family but instilled with a devout sense of charity, he and his wife Martha spent much of their money on good works. Inside OUP, Combe funded night schools and social groups, such as a brass band, and became a patron of the arts. He and Martha were fond of the Pre-Raphaelite painters, and bought many early works by Rossetti, Millais, and Holman Hunt, including The Light of the World, which they displayed at their home in the main Press quadrangle.

Outside OUP, Combe was a churchwarden and he felt a similar Christian beacon should be shone across the road in Jericho. As a result, Combe paid for the endowment of St. Barnabas. It was completed in 1869, and must surely have exceeded all his expectations. Despite controversy over its ‘high’ Anglican air, ‘Barny’s’ (as it became known) emerged as a homely focus for the community, attracting a regular congregation from the surrounding streets and from members of the University. Combe’s own funeral took place there, and visitors can still see the carving of his favourite dog, Jesse, on the base of one church pillar.

This carving reflects the common practice of men at the Press to bring a dog or a fishing rod into the print shop, ready for the end of the working day. In Combes’ time, Jericho was semi-rural, and after work the men would head for the fields or the canal around Port Meadow, as families still relied on whatever could be locally caught or grown. This feature of life was drawn into the Press as well. Much of Port Meadow was given over to agriculture during the First World War, and by the 1920s an annual Gardening Association was active at the Press, with employees from Jericho exhibiting their prize produce at a summer fête that included music, skittles, and demonstrations by the Press’s own fire brigade.

The First World War, however, left terrible scars on the Jericho community. More than 300 men entered the forces from the Press. As the memorial in the main quadrangle of OUP records, 45 of these died. Many more returned wounded or traumatised, and few talked of their experiences. The impact on families and friends in Jericho must have been devastating. At the Armistice, gas lamps across the main gate of OUP spelt out “God Save the King” but it was a bittersweet moment of glory. The Press and Jericho had seemed dependably changeless. Now both were exposed as fragile, and damaged by events.

Perhaps as a result, Press employees began to take a keen interest in preserving their history. A staff magazine, The Clarendonian, first appeared in 1919, and featured many articles on the Combes, Jericho, social activities, and local families who had been involved with the Press for generations. Their close association proved even more valuable during the Second World War. The Press became essential to the war effort, producing naval code books in conditions of utmost secrecy. Its walled-off quadrangle proved ideal for the work. Likewise, the tight Jericho family structure that filled the printing house added to the security involved: everybody knew everybody else, and could keep an eye on them.

Despite local ups and downs, that community survived and flourished late into the 20th century. It was only interrupted by the end of book printing at the Press in 1989. Computerization and harsh markets conditions finished Oxford’s grand, in-house printing tradition. Gradually, the neighbourhood around the Press changed, and ceased to house its employees. Nevertheless, the ties between OUP and Jericho stand as an extraordinary example of a unique institution depending on a neighbourhood with an equally unique character.

Martin Maw is an Archivist at Oxford University Press. The Archive Department also manages the Press Museum at OUP in Oxford. Read his previous blog post: “Sir Robert Dudley, midwife of Oxford University Press.”

OUP welcomes visitors to its museum, which traces the history of Oxford University’s involvement in printing and publishing from the 15th century to the present day. The OUP museum has recently undergone a complete refurbishment, incorporating new cases, panels, and activity stations. Anyone wishing to visit the museum must book a timeslot in advance. For more information visit the OUP Archives website.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography has granted free access for a limited time to Thomas Combe’s biography.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

All images courtesy of OUP Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

September 7, 2012

Top 3 differences between The Colbert Report and The Daily Show

How does being a guest on The Colbert Report compare to being a guest on The Daily Show? Here’s a breakdown!

More Face Time with Everyone: Backstage at The Daily Show was a blur; I had no sooner arrived than I was in make-up, met Jon, and was heading out into the lights. By contrast, I had lots of time at The Colbert Report to see the stage, meet the producers, and chat with sundry tech people. And I got way more face time with Stephen Colbert! “I’m not my character!” was pretty much the first thing he said to me. He explained that he would feign willful ignorance and my job was to educate him and the audience. And of course we talked about Ayn Rand. Colbert told me he read Anthem in a Christian ethics class in college, and then while backpacking in Europe traded somebody for Atlas Shrugged. But he only made it to the scene where Dagny discovers world renowned philosopher Dr. Hugh Akston flipping burgers at a roadside diner and recognizes his genius by the way he handled a spatula — this stretched credulity for Colbert and he gave up on reading the rest!

The Audience: The audience was a much more intimate part of The Colbert Report than The Daily Show, where guests make a grand entrance and can’t even see the audience because of the blinding lights. This time, I was seated on the set for about a minute beforehand in full view of the audience, and their laughter and response seemed a bigger part of the interview. While I was waiting to go on, I could hear everyone laughing uproariously, clearly having a great time, and that made me feel excited and ready.

The Host: The biggest difference, of course, is Jon vs. Stephen, but I had an unexpected reaction. Where most people seem to think Stephen Colbert would be a more difficult interview, I actually found him to be personally warmer and easier to talk to than Jon Stewart. Some of this was because I felt more confident the second time around. But the interview itself was also less serious and more of a performance, whereas on The Daily Show I felt I was being grilled by a formidable intellect. Before The Daily Show interview, the producer told me it would be extemporaneous, and that Jon didn’t have notes. But as I was waiting for my interview with Colbert to start, I was told he was finalizing his jokes. When I was seated on the set, I could see a detailed note card on Stephen’s side of the table. I’m pretty sure we veered off the script, but that level of planning was reassuring. The Colbert producer also did a great job of helping me understand what would create a good interview. Her top piece of advice (which I also heard at The Daily Show): “Don’t be funny!”

Author Jennifer Burns on The Colbert Report

The Colbert Report

Get More: Colbert Report Full Episodes,Political Humor & Satire Blog,Video Archive

Author Jennifer Burns on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart

The Daily Show with Jon Stewart

Get More: Daily Show Full Episodes,Political Humor & Satire Blog,The Daily Show on Facebook

Jennifer Burns is Assistant Professor of History at Stanford University and the author of Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. A nationally recognized authority on Rand and conservative thought, she has discussed her work on The Daily Show, The Colbert Report, Book TV, and has been interviewed on numerous radio programs. Read her previous blog post: “Top Three Questions About My Interview On The Daily Show”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Behind the scenes at ‘OUP Studios’

The New York office’s 13th floor conference room — a quiet, large space with no outside light — functions surprisingly well as miniature studio. Within a few hours of the film crew arriving, the office chairs and table have been removed, a green screen unfurled, camera, lights, and mic all assembled, and the Publisher of Scholarly and Online Reference is sitting in the spotlight, prepped for his interview. Things are running pretty smoothly. There’s been a small glitch with the equipment, but a new lighting piece has been ordered and is on its way. At least no one is wearing white (“it’s harsh on the face,” says the producer) or something stripy (“harsh on the camera”).

Damon Zucca, Publisher of Scholarly and Online Reference at Oxford University Press. Photo by Georgia Mierswa.

When I started as a Marketing Assistant for Online Products, my first assignment was to coordinate with a film company to develop four-five minute videos about each of our top online scholarly resources. The UK-based HobsonCurtis production team fit the bill exactly. They had already worked with Oxford to create a company video, and their work was high quality, creative, and accessible. Since our initial meeting, the online marketing team has commissioned nearly a dozen projects and completed two full-length videos, the most recent of which features Oxford’s new discovery service the Oxford Index.

Before the shooting even begins for a video like the Oxford Index promo, our to-do list looks something like this:

Brainstorm with the team to decide which voices and perspectives are most important in shaping the film. What story do we want to tell? Who are the key players?

Communicate this story in a meeting with Florence Curtis (Producer) and James Hobson (Editor) to get them on board with our vision. Set up a schedule with appropriate deadlines.

Send them the web address, key facts, and any other materials to familiarize them with the online product, so they feel as comfortable talking about it as we do.

Seek out Oxford staffers involved with the product, international scholars, and librarians with a passion for digital publishing and invite them to participate. Stress to the participants outside Oxford that they have no obligation to promote Oxford’s products — we just want them to talk about what they know!

Schedule the participants who accept (by far the most time-consuming step, but nit-picky organization now is better than a chaotic, stressed-out crew on the day of filming. I’m just guessing…).

Block off a location in the New York offices for a week of filming. Notify all key staff that they may see a cameraman walking around and not to worry. This is not for a reality TV show.

Plan out the filler shots (i.e. students working at computers in the library, staffers in discussion at an editorial meeting) to intersperse between interviews. Book those locations.

When the week of the shoot rolls around, take a deep breath, keep an eye on your Blackberry for last minute changes, and make sure everyone is comfortable and relaxed. A happy interviewee is a good interviewee. The best, according to Florence, are not only experts in their field, they’re also openly passionate and enthusiastic about sharing their “world” with an audience.

This whole process takes one to two months and is really only the groundwork for the creative stages of the project. Once the interviews have been completed, Florence and James put all the various sound bites together and come up with a ‘rough cut’ of the video. “Soundbites are weaved into a full script to complement key messages,” explained Florence. “We normally opt for opinions rather than facts and stats, but we also look for sections that are delivered well, with energy.”

Once the narrative is clearly outlined, that’s when the really polished pieces are added in, including screenshots of the web pages, a professional voiceover, and graphical representations of site features, like this:

A screengrab from the Oxford Index teaser.

A screengrab from the University Press Scholarship Online video.

Our team can feel free to give feedback, alter the order of shots (as long as it doesn’t compromise the story structure), or make edits to the voiceover script. Typically these changes are minimal. After months of prep work, the crew and our staff are almost always on the same page. If the video is clear and conveys the key messages about the product and its purpose, we consider it successful.

After the final sign off from our team’s director, we’re good to go! The video’s off to YouTube, OUP.com, our Twitter feed, and more. The sky’s the limit.

Full length videos:

University Press Scholarship Online

Click here to view the embedded video.

Oxford Index

Click here to view the embedded video.

Mini video projects:

University Press Scholarship Online for Librarians

Click here to view the embedded video.

University Press Scholarship Online for Partners

Click here to view the embedded video.

Oxford Index Teaser

Click here to view the embedded video.

Damon Zucca, Publisher of Scholarly and Online Reference, reviews his notes before the interview: “We always prefer natural conversation,” said Florence (right) “and no scripting, as this can be a little contrived.”

Damon Zucca, Publisher of Scholarly and Online Reference, with Florence Curtis, Producer at Hobson Curtis. Photo by Georgia Mierswa.

A graduate of Hamilton College and the Columbia Publishing Course, Georgia Mierswa is a marketing assistant at Oxford University Press and reports to the Global Marketing Director for online products. She began working at OUP in September 2011.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Close-up shot of a lens from high-end DV camcorder. Photo by TommL, iStockphoto.

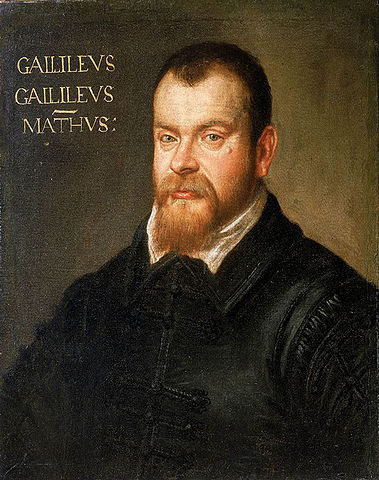

The literary and scientific Galileo

Galileo Galilei by Domenico Tintoretto, 1605-1607.

Galileo is not a fresh subject for a biography. Why then another? The character of the man, his discovery of new worlds, his fight with the Roman Catholic Church, and his scientific legacy have inspired many good books, thousands of articles, plays, pictures, exhibits, statues, a colossal tomb, and an entire museum. In all this, however, there was a chink.Galileo cultivated an interest in Italian literature. He commented on the poetry of Petrarch and Dante and imitated the burlesques of Berni and Ruzzante. His special favorite was Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, which he prized for its balance of form, wit, and nonsense. His special dislike was Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (The Liberation of Jerusalem), which violated his notions of heroic behavior and ordinary prosody. Galileo tried his hand at sonnets, sketched plots in the style of the Commedia dell’Arte, and delivered much of his science in dialogues.

The literary side of Galileo is not a discovery; a large specialist literature is devoted to it. But there is a gap in scholarship between the literary Galileo and the rest of him. How were his choices in science and literature complementary and reinforcing? What might be learned from his pronounced literary preferences about the unusual and creative features of his physics? How does Galileo’s praise of Ariosto and criticism of Tasso, on the one hand, parallel his embrace of Archimedes and rejection of Aristotle on the other?

Usually Galileo enters his biography already possessed of most of the convictions and concerns that prompted his discoveries and precipitated his troubles. One reason for endowing him with such precocity is that the documentation for his life before the age of 35 is relatively sparse. In contrast, a quantity of reliable information exists for his later life, after he had transformed a popular toy into an astronomical telescope and himself from a Venetian professor into a Florentine courtier (that happened in 1609/10 when he was 45). By paying attention to his early literary pursuits and associates, however, it is possible to tease out enough about his circumstances as a young man to give him a character different from the cantankerous star-gazer, abstract reasoner, and scientific martyr he became.

A quarrelsome philosopher, half-professor and half-courtier, whose discoveries refashioned the heavens and whose provocative use of them brought him into hopeless conflict with authority, is an attractive subject for portraiture. Add Galileo’s life-long engagement with imaginative writing and the would-be portraitist has his or her hands full. But the resultant picture, even if well-executed, would be a caricature. Galileo initially made his living and gained his reputation as a mathematician. Leave out his mathematics and you may have a compelling character, but not Galileo.

The mathematician and the littérateur have different ways of arguing. To fit together, one sometimes must give way. Galileo’s great polemical work, Dialogue on the two chief world systems, which misleadingly resembles a work of science, frequently privileges rhetoric over mathematics. When the scientific arguments are weakest, the two protagonists in the Dialogue who represent Galileo (his dead buddies Salviati and Sagredo) outdo one another in praising his contrivances and in twitting the third party to the discussions, the bumbling good-natured school philosopher Simplicio, for ignorance of geometry.

The mathematical inventions of the Dialogue that Galileo’s creatures noisily rate as unsurpassed marvels are precisely those that have given commentators the greatest difficulty. These inventions are extremely clever but evidently flawed if taken to be true of the world in which we live. Commentators tend either to interpret the cleverness as shrewd anticipations of later science or to condemn the shortfalls as just plain errors. From my point of view, these marvels should be interpreted as literary devices, conundrums, extravaganzas, inventions too good not to be true in some world if not in ours. They are hints at the form, not the completed ingredients, of a mathematical physics. Galileo’s old Dialogue and today’s Physical Review belong to different genres. Unfortunately, just as the Dialogue was not intended to meet the requirements of accuracy and verisimilitude of modern science journals, so the journals don’t reward the sort of wit and style with which Galileo brought together his literary aspirations, polemical agenda, and scientific insights.

John Heilbron is Professor of History and Vice Chancellor Emeritus of the University of California at Berkeley. One of the most distinguished historians of science, his books include Galileo, The Sun in the Church (a New York Times Notable Book) and The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

What happens next in the search for the Higgs boson?

We’re celebrating the release of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ with a series of posts by science writer Jim Baggott over the week to explain some of the mysteries of the Higgs boson. Read the previous posts: “What is the Higgs boson?”, “Why is the Higgs boson called the ‘god particle’?”, “Is the particle recently discovered at CERN’s LHC the Higgs boson?”, and “How does the Higgs mechanism create mass?”

By Jim Baggott

The 4 July discovery announcement makes it clear that the new particle is consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson. The next step is therefore reasonably obvious. Physicists involved in the ATLAS and CMS detector collaborations at the LHC will be keen to push ahead and fully characterize the new particle. They will want to know if this is indeed the Higgs boson.

How can they tell?

I mentioned in the third post in this series that the physicists at Fermilab’s Tevatron and CERN’s LHC have been searching for the Higgs boson by looking for the tell-tale products of its different predicted decay pathways. The current standard model of particle physics is used to predict the rates of production of the Higgs boson in high-energy particle collisions and the rates of its various decay modes. After subtracting the ‘background’ that arises from all the other ways in which the decay products can be produced, the physicists are left with an excess of events that can be ascribed to Higgs boson decays.

Now that we know the new particle has a mass of between 125-126 billion electron-volts (equivalent to the mass of about 134 protons), both the calculations and the experiments can be focused tightly on this specific mass value.

So far, excess events have been observed for three important decay pathways. These involve the decay of the Higgs boson to two photons ( H → γγ), two Z bosons (H → ZZ → ι+ι-ι+ι-) and two W particles (H → W+W- → ι+υ ι-υ). You will notice that these pathways all involve the production of bosons. This should come as no real surprise, as the Higgs field is responsible for breaking the symmetry between the weak and electromagnetic forces, giving mass to the W and Z particles and leaving the photon massless.

The decay rates to these three pathways are broadly as predicted by the standard model. There is an observed enhancement in the rate of decay to two photons compared to predictions, but this may be the result of statistical fluctuations. Further data on this pathway will determine whether or not there’s a problem (or maybe a clue to some new physics) in this channel.

But the Higgs field is also involved in giving mass to fermions (matter particles, such as electrons and quarks). The Higgs boson is therefore also predicted to decay into fermions, specifically very large massive fermions such as bottom and anti-bottom quarks, and tau and anti-tau leptons. Bottom quarks and tau leptons (heavy versions of the electron) are third-generation matter particles with masses respectively of about 4.2 billion electron volts (about 4 and a half proton masses) and 1.8 billion electron volts (about 1.9 proton masses).

These decay pathways are a little more problematic. The backgrounds from other processes are more significant and considerably more data are required to discriminate the background from genuine Higgs decay events. The decay to bottom and anti-bottom quarks was studied at the Tevatron before it was shut down earlier this year. But the collider had insufficient collision energy and luminosity (a measure of the number of collisions that the particle beams can produce) to enable independent discovery of the Higgs boson.

ATLAS physicist Jon Butterworth, who writes a blog for the British newspaper The Guardian, recently gave his assessment:

If and when we see the Higgs decaying in these two [fermion] channels at roughly the predicted rates, I will probably start calling this new boson the Higgs rather than a Higgs. It won’t prove it is exactly the Standard Model Higgs boson of course, and looking for subtle differences will be very interesting. But it will be close enough to justify [calling it] the definite article.

When will this happen? This is hard to judge, but perhaps we will have an answer by the end of this year.

Jim Baggott is author of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ and a freelance science writer. He was a lecturer in chemistry at the University of Reading but left to pursue a business career, where he first worked with Shell International Petroleum Company and then as an independent business consultant and trainer. His many books include Atomic: The First War of Physics (Icon, 2009), Beyond Measure: Modern Physics, Philosophy and the Meaning of Quantum Theory (OUP, 2003), A Beginner’s Guide to Reality (Penguin, 2005), and A Quantum Story: A History in 40 Moments (OUP, 2010). Read his previous blog posts.

On 4 July 2012, scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) facility in Geneva announced the discovery of a new elementary particle they believe is consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson, or ‘god particle’. Our understanding of the fundamental nature of matter — everything in our visible universe and everything we are — is about to take a giant leap forward. So, what is the Higgs boson and why is it so important? What role does it play in the structure of material substance? We’re celebrating the release of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ with a series of posts by science writer Jim Baggott over the week to explain some of the mysteries of the Higgs. Read the previous posts: “What is the Higgs boson?”,“Why is the Higgs boson called the ‘god particle’?”, “Is the particle recently discovered at CERN’s LHC the Higgs boson?”, and “How does the Higgs mechanism create mass?”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Innovating with technology

Innovation: A Very Short Introduction

By Mark Dodgson and David Gann

The next big thing in innovation lies in the ways we innovate using technology. We’re used to thinking about innovations that are technologies — the computer, the Internet, the laser, and so on. But technology is now being used to produce better innovations than ever before. By better, we mean innovations that meet our personal, organizational, and social requirements in new and improved ways, and aren’t just reliant on the technical skills and imagination of corporate engineers and marketers.

Here’s some examples of what we mean. If you have ever been lucky enough to design and build a home, you would have been confronted by technical drawings that are incomprehensible to anyone but trained architects. Nowadays you can have a computerised model of your house that lets you move around it in virtual reality so that you get a high fidelity sense of the layout and feel of rooms. You get to know what it really will look like, and make changes to it, before a brick is laid.

Move up a level and consider the challenges confronting the redesign of Cannon Street station in London. This project involved not only redesigning the station, but also building an office block above it, whilst maintaining access to the fully operational Underground station beneath it. The project used augmented reality technology to assist the design and planning process. Using a smartphone or tablet, augmented reality overlays a digital model on the surrounding real world, so you can see hidden infrastructure such as optical fibers, sewers, and gas lines — and get a sense of what things will look like before work begins. This is especially valuable for dealing with various vintages of infrastructure in busy city environments and when there are concerns about maintaining the integrity of listed buildings.

The key principle in these examples is that non-specialists can become involved in decisions that were previously only made by experts.

Other technologies that encourage this ‘democratization’ of innovation include rapid prototyping. This technology changes the economics of manufacturing, so it becomes feasible to make bespoke, individualized products cheaply. If you design something yourself, you don’t need expensive molds, dies, and machine tools to make it. We are quickly developing technologies that can produce your designs on the spot on your desk.

The Internet underlies much of the advance in the ways we innovate. It allows us to collect information from a massively increased population of designers, producers and users of innovation. It connects ideas, people and organizations. Also important is the ‘Internet of things’ that is the vast number of mobile devices and sensors that are connected together and produce data that can be valuably used to make better decisions. Drivers’ mobile phones, for example, can locate cars and traffic jams and allow better planning of transport flows. We have it from a reputable source that more transistors — the building blocks of sensors and mobile devices — were produced last year than grains of rice were grown. And they were produced at lower unit cost.

We’re all much better attuned at processing images rather than text and data. Half our cerebral cortex is devoted to visualization. Technologies developed in the computer games and film industries — think Toy Story and World of Warcraft — are being used to help innovators in areas ranging from pharmaceuticals to emergency response units in cities. The capacity, which these new technologies bring to produce dynamic images of what was previously opaque technical information, underlies the greater engagement in innovation by a wider range of people.

The technology that seems likely to have the greatest impact globally on innovation is the smartphone. Just think how short a period of time we’ve been using them and yet how much we use them for. Quite apart from putting us in direct contact with the majority in the world’s population, we use them to shop, bank, pay bills, and map our way. We use a myriad of apps for all sorts of productive and entertaining purposes. Nearly 6 million of the world’s 7 million people have mobile phones and in many developing countries there are more mobiles than people.

These devices provide opportunities for innovation amongst billions of people that have previously been excluded from the global economy for lack of information and money. Smartphones provide everyone with access to all the staggering amount of information available on the web. They can also allow access to finance, especially small amounts of money. Less than 2 million people in the world have bank accounts and banking on smartphones allows billions of previously disenfranchised people to borrow, trade, and be reimbursed for their ideas and initiative. In this way, technology makes innovation more inclusive and less the privilege of corporations with research and development departments. We look forward to a massive wave of exciting new and unimaginable ideas from all sorts of people from everywhere around the world.

is Director of Technology and Innovation Management Centre, University of Queensland Business School, and David Gann is Head of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Imperial College London. They co-authored Innovation: A Very Short Introduction.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Above Cannon St Station, London, by Tom Morris (Creative Commons License). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

September 6, 2012

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online launches today: but why?

Today sees the launch of a major new publishing initiative from Oxford University Press: Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO). OSEO will provide trustworthy and reliable critical online editions of original works by some of the most important writers in the humanities, such as William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, as well as works from lesser-known writers such as Shackerley Marmion. OSEO is launching with over 170 scholarly editions of material written between 1485 and 1660, and annual content additions will cover chronological periods until it contains content from Ancient Greek and Latin texts through to the modern era. This is exciting stuff, and here Project Director Sophie Goldsworthy explains why!

By Sophie Goldsworthy

Anyone working in the humanities is well aware of the plethora of texts online. Search for the full text of one of Shakespeare’s plays on Google and you’ll find hundreds of thousands of results. Browse popular classics on Amazon, and you’ll find hundreds available for free download to your device in 60 seconds or less. But while we’re spoilt for choice in terms of availability, finding an authoritative text, and one which you can feel confident in citing or using in your teaching, has paradoxically never been more difficult. Texts aren’t set in stone, but have a tendency to shift over time, whether as the result of author revisitings, the editing and publishing processes through which they pass, deliberate bowdlerization, or inadvertent mistranscription. And with more and more data available online, it has never been more important to help scholars and students navigate to trusted primary sources on which they can rely for their research, teaching, and learning.

Oxford has a long tradition of publishing scholarly editions — something which still sits at the very heart of the programme — and a range and reach unmatched by any other publisher. Every edition is produced by a scholarly editor, or team, who have sifted the evidence for each: deciding which reading or version is best, and why, and then tracking textual variance between editions, as well as adding rich layers of interpretative annotation. So we started to re-imagine how these classic print editions would work in a digital environment, getting down to the disparate elements of each — the primary text, the critical apparatus, and the explanatory notes — to work out how, by teasing the content of each edition apart, we could bring them back together in a more meaningful way for the reader.

We decided that we needed to organize the content on the site along two axes: editions and works. Our research underlined the need to preserve this link with print, not only for scholars and students who may want to use the online version of a particular edition, but also for librarians keen to curate digital content alongside their existing print holdings. And yet we also wanted to put the texts themselves front and centre. So we have constructed the site in both ways. You can use it to navigate to a familiar edition, travelling to a particular page, and even downloading a PDF of the print page, so you can cite from OSEO with authority. But you can also see each author’s works in aggregate and move straight to an individual play, poem, or letter, or to a particular line number or scene. Our use of XML has allowed us to treat the different elements of each edition separately: the notes keep pace with the text, and different features can be toggled on and off. This also drives a very focused advanced search — you can search within stage directions or the recipients of letters, first lines or critical apparatus — all of which speeds your journey to the content genuinely of most use to you.

As a side benefit — a reaffirmation, if you like, of the way print and online are perfectly in step on the site — many of our older editions haven’t been in print for some time, but embarking on the data capture process has made it possible for us to make them available again through on-demand printing. These texts often date back to the 1900s and yet are still considered either the definitive edition of a writer’s work or valued as milestones in the history of textual editing, itself an object of study and interest. Thus reissuing these classic texts adds, perhaps in an unanticipated way, to the broader story of dissemination and accessibility which lies at the heart of what we are doing.

For those minded to embark on such major projects, OSEO underlines Oxford’s support for the continuing tradition of scholarly editing. Our investment in digital editions will increase their reach, securing their permanence in the online space and making them available to multiple users at the same time. There are real benefits brought by the size of the collection, the aggregation of content, intelligent cross-linking with other OUP content — facilitating genuine user journeys from and into related secondary criticism and reference materials — and the possibility of future links to external sites and other resources. We hope, too, that OSEO will help bring recent finds to an audience as swiftly as possible: new discoveries can simply be edited and dropped straight into the site.

Over the past century and more, Oxford has invested in the development of an unrivalled programme of scholarly editions across the humanities. Oxford Scholarly Editions Online takes these core, authoritative texts down from the library shelf, unlocks their features to make them fully accessible to all kinds of users, and makes them discoverable online.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sophie Goldsworthy is the Editorial Director for OUP’s Academic and Trade publishing in the UK, and Project Director for Oxford Scholarly Editions Online. To discover more about OSEO, view this series of videos about the launch of the project.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The life of Ford Madox Ford

This year’s television adaptation of Parade’s End has led to an extraordinary surge of interest in Ford Madox Ford. The ingenious adaptation by Sir Tom Stoppard; the stellar cast, including Benedict Cumberbatch, Rebecca Hall, Alan Howard, Rupert Everett, Miranda Richardson, Roger Allam; the flawlessly intelligent direction by award-winning Susanna White, have not only created a critical success, but reached Ford’s widest audience for perhaps fifty years. BBC2 drama doubled its share of the viewing figures. Reviewers have repeatedly described Parade’s End as a masterpiece and Ford as a neglected Modernist master. Those involved in the production found him a ‘revelation’, and White and Hall are reported as saying that they were embarrassed that their Oxbridge educations had left them unaware of Ford’s work. After this autumn, fewer people interested in literature and modernism and the First World War are likely to ask the question posed by the title of Alan Yentob’s ‘Culture Show’ investigation into Ford’s life and work on September 1st: “Who on Earth was Ford Madox Ford?”

Sylvia and Christopher Tietjens, played by Rebecca Hall and Benedict Cumberbatch in the BBC2 adaptation of Parade's End.

It’s a good question, though. Ford has to be one of the most mercurial, protean figures in literary history, capable of producing violent reactions of love, admiration, ridicule or anger in those who knew him, and also in those who read him. Many of those who knew him were themselves writers — often writers he’d helped, which made some (like Graham Greene) grateful, and others (like Hemingway) resentful, and some (like Jean Rhys) both. So they all felt the need to write about him — whether in their memoirs, or by including Fordian characters in their fiction. Ford himself thought that Henry James had based a character on him when young (Merton Densher in The Wings of the Dove). Joseph Conrad too, who collaborated with Ford for a decade, is thought to have based several characters and traits on him.

I’d spent several years trying to work out an answer that satisfied me to the question of who on earth Ford was. The earlier, fairly factual biographies by Douglas Goldring and Frank MacShane had been supplanted by more psycho-analytic studies by Arthur Mizener and Thomas C. Moser. Mizener took the subtitle of Ford’s best-known novel, The Good Soldier, as the title of his biography: The Saddest Story. He presented Ford as a damaged psyche whose fiction-writing stemmed from a sad inability to face the realities of his own nature. Of course all fiction has an autobiographical dimension. A novelist’s best way of understanding characters is to look into his or her own self. But there is an element of absurdity in diagnosing an author’s obtuseness from the problems of fictional characters. This is because if writers can make us see what’s wrong with their characters, that means they understand not only those characters, but themselves (or at least the traits they share with those characters). John Dowell, the narrator of The Good Soldier, appears at times hopelessly inept at understanding his predicament. His friend, the good soldier of the title, Edward Ashburnham, is a hopeless philanderer. If Ford saw elements of himself in both types, he had to be more knowing than them in order to show them to us. And anyway, they’re diametrically opposed as types.

Ford’s psychology needs to be approached from a different angle. Rather than seeing his fiction as displaying symptoms that give him away, what if it is diagnostic? What if, rather than projecting wishful fabrications of himself, he turns the spotlight on that process of fabrication itself — on the processes of fantasy that are inseparable from our subjectivities? To answer the question of who Ford was, we have to look at the ways his work explores how we understand ourselves through stories: the stories that are told to us, the stories we tell ourselves; the myths and histories and anecdotes that populate our imaginations. Where Moser had concentrated on what he called The Life in the Fiction of Ford Madox Ford — trying to identify biographical markers in episodes in novels — I found myself in quest of ‘the fiction in the life’.

Ford’s psychology needs to be approached from a different angle. Rather than seeing his fiction as displaying symptoms that give him away, what if it is diagnostic? What if, rather than projecting wishful fabrications of himself, he turns the spotlight on that process of fabrication itself — on the processes of fantasy that are inseparable from our subjectivities? To answer the question of who Ford was, we have to look at the ways his work explores how we understand ourselves through stories: the stories that are told to us, the stories we tell ourselves; the myths and histories and anecdotes that populate our imaginations. Where Moser had concentrated on what he called The Life in the Fiction of Ford Madox Ford — trying to identify biographical markers in episodes in novels — I found myself in quest of ‘the fiction in the life’.

Compared to some of the canonical modernists like Joyce or Eliot, Ford is unusual in writing so much about his own life — a whole series of books of reminiscences. They’re full of marvelous stories. Take the one with which he ends his book celebrating Provence. He describes how, when he earned a sum of money during the Depression, he and Janice Biala decided it was safer to cash it all rather than trust to failing banks. They visit one of Ford’s favourite towns, Tarascon on the Rhone. Ford has entrusted the banknotes to Biala. “I am constitutionally incapable of not losing money,” said Ford. But as they cross the bridge, the legendary mistral starts blowing:

And leaning back on the wind as if on an upended couch I clutched my béret and roared with laughter… We were just under the great wall that keeps out the intolerably swift Rhone… Our treasurer’s cap was flying in the air… Over, into the Rhone… What glorious fun… The mistral sure is the wine of life… Our treasurer’s wallet was flying from under an armpit beyond reach of a clutching hand… Incredible humour; unparalleled buffoonery of a wind… The air was full of little, capricious squares, floating black against the light over the river… Like a swarm of bees: thick… Good fellows, bees….

And then began a delirious, panicked search… For notes, for passports, for first citizenship papers that were halfway to Marseilles before it ended… An endless search… With still the feeling that one was rich… Very rich.

“I hadn’t been going to do any writing for a year,” mused Ford, recognising what an unlikely prospect it was. “But perhaps the remorseless Destiny of Provence desires thus to afflict the world with my books….” Yet for all the wry cynicism of this afterthought Biala remembered that “Ford was amused for months at the thought that some astonished housewife cleaning fish might have found a thousand-franc note in its belly.”

Ford’s stories, for all their playfulness, also earned him notoriety for the liberties they took with the facts. Indeed, Ford courted such controversy, writing in the preface to the first of them, Ancient Lights, in 1911:

This book, in short, is full of inaccuracies as to facts, but its accuracy as to impressions is absolute [....] I don’t really deal in facts, I have for facts a most profound contempt. I try to give you what I see to be the spirit of an age, of a town, of a movement. This can not be done with facts. (pp. xv-xvi)

He called his method Impressionism: an attention to what happens to the mind when it perceives the world. Ford is the most important analyst in English of Impressionism in literature, not only elaborating the techniques involved, but defining a movement. This included writers he admired like Flaubert, Maupassant and Turgenev, as well as his friends James, Conrad, and Crane. He also used the term to cover writers we now think of as Modernist, such as Rhys, Hemingway, or Joyce. Though most of these writers were resistant to the label, they wrote much about ‘impressions’ and their aesthetic aims have strong family resemblances.

One feature that sets Ford’s writing apart is his tendency to retell the same stories, but with continual variations. This creates an immediate problem for a literary biographer wanting to use the subject’s autobiographical writing to structure the narrative upon. Which version to use? Which to believe? They can’t all be true. And their sheer proliferation and multiplicity shows how he couldn’t tell a story about himself without it turning into a kind of fiction. In one particularly striking example, which Ford tells at least five times, he is taking the train with Conrad to London to take to their publisher corrected proofs of their major collaborative novel, Romance. Conrad is obsessively still making revisions, and because he’s distracted by the jolting of the train, he lies down on his stomach so he can correct the pages on the floor. As the train pulls into their London station, Ford taps Conrad on the shoulder. But Conrad is so immersed in the world of Cuban pirates, says Ford, that he springs up and grabs Ford by the throat. Ford’s details often seem too exaggerated for some readers. Would Conrad really have gone for his friend like that? Would he really have hazarded his city clothes on a train carriage floor? The fact that the details change from version to version shows how fluid they are to Ford’s imagination, but there’s at least a grain of plausible truth. Here it’s the power of literature to engross its readers, so that one could be genuinely startled when interrupted while reading minutely. So, as with many of Ford’s stories, it’s a story about writing, writers, and what Conrad called “the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel… before all, to make you see.” And perhaps one of the things Ford wants us to see in this episode is how any aggression between friends who are writers needs to be understood in that context — as motivated as much by their obsession with words, as by any personal hostilities.

That is why a writer’s life — especially the life of a writer like Ford — is a dual one. As many of them have observed, writers live simultaneously in two worlds: the social world around them, and world they are constantly constructing in their imaginations. Impressionism seemed to Ford the method that best expressed this:

I suppose that Impressionism exists to render those queer effects of real life that are like so many views seen through bright glass — through glass so bright that whilst you perceive through it a landscape or a backyard, you are aware that, on its surface, it reflects a face of a person behind you. For the whole of life is really like that; we are almost always in one place with our minds somewhere quite other.

Ford’s life was dual in another important way, though. Like many participants, he felt the First World War as an earthquake fissure between his pre-war and post-war lives. It divided his adult life into two. His decision to change his name (after the war, which he had endured with a German surname), and to change it to its curiously doubled final form, surely expresses that sense of duality. Ford was in his early forties when he volunteered for the Army — something he could easily have avoided on account not only of his age, but of the propaganda writing he was doing for the Government. His experience of concussion and shell-shock after the Battle of the Somme changed him utterly, and provided the basis for his best work afterwards. Though he wrote over eighty books, most of them with brilliance and insight, two masterpieces have stood out: The Good Soldier, which seems the culmination of his pre-war life and apprenticeship to the craft of fiction, and then the Parade’s End sequence of four novels, which drew on his own war experiences to produce one of the great fictions about the First World War, or indeed any war.

Max Saunders is Director of the Arts and Humanities Research Institute and Professor of English and Co-Director at the Centre for Life-Writing Research at King’s College London. He is the author of Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life, editor of the Oxford World’s Classic edition of The Good Soldier, and editor of Some Do Not… (the first volume of Ford’s series of novels Parade’s End).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about The Good Soldier on the

View more about Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life on the

Image credits: Still from BCC2 adaption of Parade’s End. (Source: bbc.co.uk); Portrait of Ford Madox Ford (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

Mourning and praising Colony Records

Colony Records, which will close on Saturday, September 15th after 64 years of business, is no mere record store. A cavernous, crowded, and never particularly tidy place, Colony has kept one foot firmly in its Tin Pan Alley past, and the other in its media-saturated present. The largest and easily most famous provider of sheet music in New York City, Colony also houses cassettes, CDs, DVDs, karaoke recordings, an absolutely enormous collection of records, and all kinds of memorabilia: pop music action figures and Beatles mousepads; signed, fading photographs of A-, B-, and C-list celebrities from every decade that the store has been open; novelty key chains and promotional buttons from countless Broadway musicals; old concert programs, playbills, and t-shirts; Ramones coffee mugs and “Glee” lunchboxes; and locked shrines in dank corners, filled with dusty Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, and Elvis Presley collectibles. The staff, depending on whom you talk to, is comprised either of snobbish, standoffish jerks or brilliant, walking encyclopedias who can help you locate a piece of sheet music within seconds of your humming a few notes from the song in question, no matter how obscure. I suppose that genius and churlishness, just like Tin Pan Alley and rock and roll, are hardly mutually exclusive; the owners’ understanding of this is, in the end, likely why Colony managed to last as long as it did.

Photo by William Ruben Helms. Used with permission.

Colony Sporting Goods became Colony Records when its owners, Harold S. (“Nappy”) Grossbardt and Sidney Turk, took it over in 1948. Their sons, Michael Grossbardt and Richard Turk, are the current and will be the last owners. Initially located at 52nd Street and Broadway, Colony moved in 1970 to the Brill Building, at Broadway and 49th Street, where it has remained. On a typical day, visitors to the store include tourists from all over the world, members of the theater industry, professional and amateur musicians, and record and memorabilia collectors. Countless celebrities have patronized Colony in its six decades: Benny Goodman, Miles Davis, Frank Sinatra, John Lennon, Elton John, Neil Diamond, and Jimi Hendrix. The bizarrely image-conscious Michael Jackson used to make furtive visits via a back entrance, specifically to buy up enormous amounts of his own memorabilia. According to lore, both Bernadette Peters and Dusty Springfield decided to become entertainers after merely walking by the store and hearing music emanating from it. When James Brown visited, he apparently exclaimed, “This smells like a music store!”

He’s right; it does. And before paying my last visit to Colony this past week, I’d completely forgotten what a music store smells like. Also, what one looks like and feels like.

I am no stranger to Colony. I’ve bought plenty of sheet music from them in the 25 years that I’ve called myself a New Yorker. In that stretch of time, I have been, at various times and sometimes simultaneously, a reasonably good vocalist, a truly terrible pianist, a middling guitar player, and a music scholar who writes frequently about the post-1960 stage musical. I’m not an atypical patron, I think. In the weeks since news of Colony’s closing broke, I’ve heard plenty of people mention that they used to go there regularly when they dabbled in trumpet or in cello, or taught guitar or voice lessons, or before they decided to quit pursuing a career in the theater, or before Amazon started carrying everything they needed.

Yet despite how much it has served us New Yorkers — not to mention the millions of tourists who stroll, sometimes maddeningly slowly, through Times Square at some point during their visit here — I wasn’t terribly surprised by the news that Colony had fallen prey to declining sales, the Internet, and (the final straw) a landlord who plans to quintuple the rent of the store. None of this is shocking, especially when it comes to commercial real estate in Manhattan, which at this point heavily favors conglomerates. Really, the big news to me, at least initially, was not that Colony was closing. It is that Colony has managed to stay open for so very long.

Think about it: Colony opened in 1948. During the 1950s, rock and roll arrived, purportedly to destroy Tin Pan Alley in one fell swoop. During the 1960s, again purportedly, young people en masse abruptly turned their backs on the musical tastes of their elders. During these decades, Colony only grew in size — —so large, in fact, that its owners had to relocate. Its move, in 1970, coincided with one of the darkest periods in New York City’s history. Mired in financial crisis, and inching dangerously close to bankruptcy, New York was hardly a happy place in the 1970s. Times Square, Colony Records’ new home, had become internationally notorious — a sleazy, crime-ridden example of everything that had gone wrong with the urban jungle.

And yet Colony survived it all. It outlasted Beatlemania, psychedelia, disco, punk, hair metal, and hip-hop, MTV, VH1 and the first two decades of the Internet. It outlasted Napster and the dot-com boom. It outlasted Tower Records, HMV, Patelson’s, and Footlight Records. Arguably, it even outlasted, for a while at least, the neighborhood around it; Times Square was given a Disneyfied “facelift” in the early 1990s, which has resulted in a more tourist-friendly and seemingly safer, if also increasingly generic and corporate urban environment. Since it first opened in the postwar era, Colony has grown with and adapted to the times in ways that none of its past competitors managed. My initial reaction, then, was merely to praise Colony — not to mourn it for a second — because in the end, sixty years is a pretty impressive run for a family-owned business in the middle of Times Square.

But then I went to visit, and my logic gave way to a surprisingly emotional wave of nostalgia.

James Brown was right: it’s the smell of the place that gets you first — a mix of old, comfortably dusty things; of vinyl and paper and cool, musty formica. The sounds, too: a mix of Beatles songs blasted through the speaker, competing with several languages being spoken by as many tourists. “Look, honey, a Lady Gaga backpack!” a woman with a thick Long Island accent shouted down the aisle at her absolutely mortified pre-teen son. A man in a suit and sunglasses paced back and forth through the brass section while he talked shop on his phone. “We need to give them more bang for the buck this year,” he said. “Maybe we could get another few animals up on the stage this time around?” As “Strawberry Fields” came on over the speakers, I wandered through the aisle of picked-over cassette tapes, passed a group of Italian women looking at Beatles memorabilia, and found a huge basket of promotional pins from past Broadway musicals. I grabbed three, almost at random, from shows that all flopped at least a decade ago: Nick and Nora, Mayor, James Clavell’s Shogun: The Musical. The producers of those shows would have killed for even a fraction of the run that Colony has had.

Photo by William Ruben Helms. Used with permission.

I was about to leave, but then I started rifling through music books for the sake of rifling through music books. New ones, used ones, ones for woodwinds, piano, violin, voice, and guitar. They are, I am sure, all available online should I ever decide to become a terrible violinist or a horrible oboeist. But wandering through so much sheet music, being able to reach out and touch it, page through it, admire the quality of the paper is — much like spending an hour or two in a store flipping through records, or cassettes, or CDs — something I’d completely forgotten the pleasure of. I’ve spent a great deal of my life killing time in stores like these. I miss them, even as I understand that times change and modes of commerce with them. The automats are gone, too, from Times Square. So are the dime museums, the grindhouses, the arcades and the penny restaurants, and yes, the notorious if occasionally hilarious XXX theaters (a favorite marquee post from the early 1980s: “Hot As Hell! A Potent Groin Grabber!!”). I am sure that whatever chain store opens up in the place of Colony — be it a Gap, an Urban Outfitters, or a particularly snazzy Applebees — will, someday, also eventually close up shop.

I ended up purchasing the three pins, along with two used books of classic rock and pop songs “for very easy guitar,” which is about my speed these days. Warren, the longtime Colony employee who rang me up, gave me one of the pins for free, and then called my attention to the song that had come on over the speakers. “Man, this is the Beatles before they even sounded like the Beatles, you know?”

“Sure,” I replied, snapping out of my fog of nostalgia to focus on his. “Because it wasn’t their song, right? It was one of the songs they covered. It was originally by — by –”

“It’s ‘Matchbox,’” he said. “Carl Perkins. 1955? No. 1956.”

I chuckled. “Thanks.” I said, taking my bag and preparing to leave Colony for the last time, and realizing that my eyes were welling up. “For everything. I’ll miss you.”

He didn’t look surprised at all. “I know,” he said, gently. “We’ll miss you, too.”

Elizabeth L. Wollman is Assistant Professor of Music at Baruch College in New York City, and author of Hard Times: The Adult Musical in 1970s New York City and The Theater Will Rock: A History of the Rock Musical, from Hair to Hedwig. She also contributes to the Show Showdown blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers