Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1020

September 21, 2012

Tariq Ramadan on the Arab Spring

News broke of the killing of Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans in Libya followed by numerous protests throughout the Arab World while Tariq Ramadan was in the United States to discuss one of the most important developments in the modern history of the Middle East, the so-called Arab Spring. One of the world’s leading Islamic thinkers, Tariq Ramadan, he has won global renown for his reflections on Islam and the contemporary challenges in both the Muslim majority societies and the West.

On Friday, September 14th Ramadan spoke at the Philadelphia Free Library. A podcast of that talk is available here. Listen to the podcast:

[See post to listen to audio]

Tariq Ramadan is Professor of Islamic Studies at Oxford University, and is President of the European Muslim Network in Brussels. His books include Islam and the Arab Awakening, What I Believe, Radical Reform: Islamic Ethics and Liberation, In the Footsteps of the Prophet: Lessons from the Life of Muhammad, Western Muslims and the Future of Islam, and Islam, the West, and the Challenges of Modernity.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

How the social brain creates identity

Who we are is a story of our self — a narrative that our brain creates. Like the science fiction movie, we are living in a matrix that is our mind. But though the self is an illusion, it is an illusion we must continue to embrace to live happily in human society. In The Self Illusion, Bruce Hood reveals how the self emerges during childhood and how the architecture of the developing brain enables us to become social animals dependent on each other.

Below, you can listen to Bruce Hood speak with Ginger Campbell, MD on the Brain Science Podcast, a regular podcast series on recent discoveries from the world of neuroscience.

Listen to the podcast:

[See post to listen to audio]

Bruce Hood is the author of The Self Illusion: How the Social Brain Creates Identity. He is currently the Director of the Bristol Cognitive Development Centre at the University of Bristol. He has been a research fellow at Cambridge University and University College London, a visiting scientist at MIT, and a faculty professor at Harvard. He has been awarded an Alfred Sloan Fellowship in neuroscience, the Young Investigator Award from the International Society of Infancy Researchers, the Robert Fantz Memorial Award and voted a Fellow by the Association for Psychological Science. He is the author of several books, including SuperSense: Why We Believe the Unbelievable. This year he was selected as the 2011 Royal Institution Christmas Lecturer — to give three lectures broadcast by the BBC — the most prestigious appointment for the public engagement of science in the UK. Read his previous blog post: “You are essentially what you wear.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The sustainability of civil engineering

By David Muir Wood

The definition of civil engineering is a historical curiosity. Originally so called to distinguish it from military engineering, it was particularly concerned (in the eighteenth century, for example) with the provision of infrastructure for transport, hence the French emphasis on ponts et chaussées in their organisation of education and professional activity. But there is really no difference in the nature of the engineering performed by civil engineers and military engineers; a bridge or an airfield is a bridge or an airfield, whether it is provided for the general benefit of mankind or to enable an army to advance. Perhaps the speed of construction and the intended lifetime will be different – the latter often linked to the former. Charles Coulomb, who is remembered today by schoolchildren for his work on electrostatics (which makes him an electrical engineer), was employed by the army designing and constructing fortifications in Martinique (which makes him a military engineer), an activity which led to a nice piece of analysis which is familiar to all students of civil engineering today.

As a catch-all term, civil engineering in the early nineteenth century covered the broadest range of engineering activities but, for whatever reason, in the United Kingdom various splinter groups formed – mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, municipal engineers, aeronautical engineers, naval architects – and the engineering profession is littered with ‘Institutions’ for each of these professional groups which would originally have fallen under the aegis of the Institution of Civil Engineers.

As a catch-all term, civil engineering in the early nineteenth century covered the broadest range of engineering activities but, for whatever reason, in the United Kingdom various splinter groups formed – mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, municipal engineers, aeronautical engineers, naval architects – and the engineering profession is littered with ‘Institutions’ for each of these professional groups which would originally have fallen under the aegis of the Institution of Civil Engineers.

The Institution of Civil Engineers was formed, we gather, in a coffee shop in Fleet Street (London) in 1818 by a group of engineers whose names are known but not familiar – it was only with the engagement of Thomas Telford as their first President that they gained some recognition, culminating in the award of a Royal Charter in 1828. Here for the first time an attempt was made by Thomas Tredgold to define civil engineering in words that have a wonderful nineteenth century beauty and resonance. The purpose of the newly fledged Institution was:

‘The general advancement of mechanical science, and more particularly for promoting the acquisition of that species of knowledge which constitutes the profession of a civil engineer; being the art of directing the great sources of power in nature for the use and convenience of man, as the means of production and of traffic in states, both for external and internal trade, as applied in the construction of roads, bridges, aqueducts, canals, river navigation, and docks, for internal intercourse and exchange; and in the construction of ports, harbours, moles, breakwaters, and light-houses, and in the art of navigation by artificial power, for the purposes of commerce; and in the construction and adaptation of machinery, and in the drainage of cities and towns.’

Many of those examples have been lost to other institutions but the phrase ‘the art of directing the great sources of power in nature for the use and convenience of man’ has remained. How would we describe civil engineering today? Can we continue to subscribe to this wonderful phrase of Thomas Tredgold’s? Prince Charles, in a recent lecture to the Institution of Civil Engineers, calls with typical gallo-principian passion for civil engineers committed to sustainability to turn Tredgold’s phrase around and seek to be ‘directed by nature’, ‘to understand and to work in harmony with nature’s underlying patterns of behaviour.’

The problem with words is that you never know where they have been – or as Humpty-Dumpty said, ‘When I use a word it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.’ The nuances associated with Tredgold’s words in 1828 are somewhat lost in dictionary definitions in 2012. It is the absence of any timescale that leaves the phrase open to attack. If we interpret ‘man’ as representing the human race, which implicitly includes our children and our children’s children, then ‘the use and convenience of man’ contains a future positive intention of sustainability with regard to the sources of power in nature which goes beyond the negative possibility of present exploitation.

Is it a lack of linguistic confidence which might make us reluctant to displace a well-loved nineteenth century phrase in favour of a twenty-first century revisionist version? Or is it a recognition that, as with the Book of Common Prayer, there is something special about the original words and language.? If we pause and seek to interpret them in our own time we will understand a deeper meaning relevant for us and for the future. If we insist on apparent instant sound-bite clarity we will be certain that we have understood without hearing and without thinking.

Prince Charles is right in urging civil engineers to concern themselves more vigorously with sustainability. But I do not think that we need to discard Thomas Tredgold as we do so.

David Muir Wood is Emeritus Professor of Civil Engineering at the University of Bristol and Professor of Geotechnical Engineering, University of Dundee. He is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering, and author of Civil Engineering: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Roman aqueduct Pont du Gard by rzdeb, iStockphoto.

September 20, 2012

Why are reference works still important?

Students, academics, and general readers around the world regularly look up a definition, check a fact, or read about an unfamiliar topic as a springboard to further research. How people find and use such information has changed enormously during the past 20 years. But looking at the growing use of our online products, we know that many still choose to reach beyond first impressions on the web to delve further in a reference work from Oxford. Why is it still so important to do so?

We tend to assume that ‘information overload’ is a modern problem. But the need to find reliable summaries of topics quickly in a messy and confusing world of knowledge has been with us a long time. As Richard Yeo’s entry for ‘encyclopedia’ in The Oxford Companion to the Book tells us:

Ephraim Chambers offered his Cyclopedia (2 vols, 1728) as a condensation of all useful knowledge, and thus a substitute for many other books. His two folio volumes would ‘answer all the Purposes of a Library, except Parade and Incumbrance’…

Even then, encyclopedias faced challenges to their authority. How could one alphabetical work, compiled by one individual, claim to present all human knowledge? Encyclopedia authors could always argue that their role is to distill the knowledge of other experts; but by the time Oxford University Press first put our general reference content online in 2003, the world of reference had changed. As Richard Yeo tells us:

H.G. Wells forecast…in the 1930s…an encyclopedia which looked nothing like a book. His ideal ‘World Encyclopedia’ was an archive of microfilm updated by a panel of international experts, simulating a ‘World Brain’.

Now we are used to living in an age where a single print work is no longer expected to provide ‘all the Purposes of a Library’. Online readers have embraced online search engines, Wikipedia, and other collections of data from many sources, and are accustomed to seeing answers from other users as much as relying on an ‘expert’ author.

So it’s never been easier to find a mass of facts. But readers are still faced with a confusing array of resources, where points of view and trust are hard to judge – and so we still value interpretation, guidance, and authenticity. Research in information studies and by OUP has shown in starting research from a general web search – as most of us now do — we are looking for immediate factual frameworks, context and vocabulary to shape further enquiry, and guidance on where to go next to deepen our understanding. And when it matters, we want to know we are getting answers from someone who really knows what they’re talking about, which are rooted in a framework of higher-level research in the subject.

The challenge for the ‘traditional’ reference work are to meet these needs while keeping content as up to date, and making it easy to find and use on the web where the questions are being asked. That’s why the new Oxford Reference service now provides masses of freely available ‘overview’ information that is easily discoverable from the web, and why our new update program works to monthly deadlines for key factual amendments.

Most journeys do not begin and end with reference information, however. People can need quick reference at any stage of their research journey, while exploring other content. The best reference can now provide not just a hub of information on a particular topic, but also a network of links which leads on to deeper content of all types. In the context of OUP, reference can guide users to a world of trusted scholarship in Oxford monographs, bibliographies, journal articles, and the like. Imagine finding an overview of a topic such as globalization, and seeing paths forward to explore its impact on economics, art, society, environment, policy, business, history … at whatever level you choose.

The need for good reference information has never been greater: not only for the ‘who, what, when, and how’, but for the trusted guidance and instant connection to the best deeper research. It has to be very easy to find, and quickly refreshed where necessary. However, to return to the Cyclopedia, and to Richard Yeo’s entry, we find that perhaps things haven’t changed quite as much as we first thought:

The second edition…(1738)…reinforced Chambers’s mantra: namely the call for ‘a reduction of the vast bulk of universal knowledge into a lesser compass’ so that essential knowledge of a range of subjects was accessible to all.

Reference is adapting for future generations of users, but we should not lose sight of that ambition.

Robert Faber is Editorial Director of Oxford Reference. Today Oxford University Press launches Oxford Reference, the new home of Oxford’s quality general reference publishing. Bringing together 2 million entries, we have integrated the superb reference content from Oxford Reference Online and the Oxford Digital Reference Shelf onto the new Oxford Reference platform. The new service enables users to access and cross-search Oxford’s prestigious reference works at the click of a button, and hugely extends its usefulness by opening up free material for general web searching and linking.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Five things you should know about Grove

There is a reference work on the subject of music to which English-speaking music students are referred every day. It has been around, in various editions, for over 130 years, and in its current online form it includes more than 40,000 full articles. As a 1955 article in Time put it, “For three-quarters of a century, the sun never set on Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians.”

When I was a music student, Grove Music Online (the expansive online version of the reference work) was the place my professors told me to begin looking for information, and I trusted their opinion. But I didn’t know a thing about how Grove had come to be in the first place, or when it first appeared on the web, or why it was called Grove. I just knew it as the first stop on my daily research commute.

Here are five cool things that, like me, you might not have known about Grove:

1. The first edition was created by George Grove, a civil engineer. He was not a formally trained musician, but had high-level experience as a music writer and editor, and had a great passion for the field. In his correspondence he wrote that “while I live nothing gives me greater pleasure than to work for music!”

1. The first edition was created by George Grove, a civil engineer. He was not a formally trained musician, but had high-level experience as a music writer and editor, and had a great passion for the field. In his correspondence he wrote that “while I live nothing gives me greater pleasure than to work for music!”

2. The original version of the dictionary has four volumes, whereas the most recent edition has a whopping 29. (I have the sagging bookshelf to prove it.)

3. Grove was also a leader in the founding of the Royal College of Music and was its first director. His role there and in the creation of the dictionary earned him a knighthood in 1883.

4. Though referred to as Grove’s (an abbreviation of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians) by many of its readers, its original title was simply A Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Replacing “A” with “Grove’s” in the title was a tribute by the editor of the second edition to the editor of the first, and the Grove name remained for all subsequent editions.

5. While Grove Music Online includes articles from the most recent print edition and is updated three times a year, it also includes entries contributed by Grove himself in the 19th century. My favorite? Couac, a term defined by Sir George as “a sudden horrible noise to which any clarinet is liable,” and which anyone who has been in the vicinity of a beginning clarinetist will immediately appreciate.

Grove Music Online’s Editor in Chief, Deane Root, has written a new “History of Grove Music,” now available to anyone on the public pages of Oxford Music Online. It tells the story of how the dictionary was created and how it has changed over its lengthy (and ongoing) history.

Jessica Barbour is the Associate Editor for Grove Music/Oxford Music Online. You can read her previous blog posts, “Wedding Music” and “Clair de Supermoon,” or learn more about George Grove on Grove Music Online.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of George Grove courtesy of Grove Music Online. Please request permission for any reuse.

Unravelling the life of Henry Cowell without unravelling the biographer

As I began to go through papers at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, I was buffeted by competing forces: the exhilaration of unravelling the stunning reality of a man’s life, and the growing fear that, should I actually live to read all of the documents, I might never be able to digest them. If I had known from the outset the true size of that archive, how many other sources I would have to consult, how much background information I would need, and how many interviews would be necessary, I would have quit at once. Fortunately, I didn’t know what I faced.

Henry Cowell’s life was so rich in extraordinary adventures and projects, miraculous encounters, and distressing misfortunes, that in a novel such a character would be considered implausible. And there is no shortage of information to bolster his story.

Reading through the Cowell papers — some 180 linear feet of paper — was enlightening, once I resigned myself to giving up so much of my life to it. The staggering cast of characters in the correspondence includes Presidents Roosevelt, Kennedy, and Johnson; Leon Trotsky’s sister; most of the significant composers of the first half of the twentieth century; masses of intellectuals, entrepreneurs, and performers; and perfectly ordinary people. The thousands of letters, however, were only the beginning. There are many hundreds of newspaper reviews and articles in many languages, Cowell’s own voluminous writings, his music, and the miscellany of his life, including unused Paris metro tickets from the 1920s. Furthermore, significant invaluable information turned up in libraries and archives from California to Moscow and in unending books and articles about musical life, urban development, and California law. Then I needed several years of what my son calls “pacing to the refrigerator” before I could begin writing.

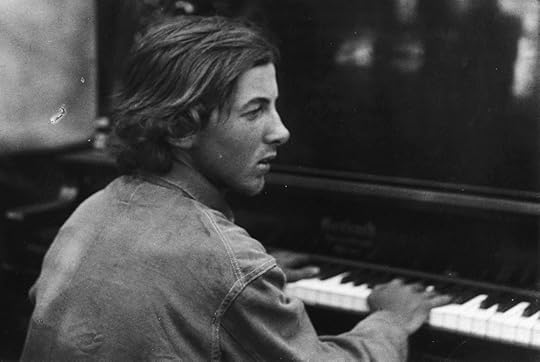

Henry Cowell playing the piano, ca. 1913. Copyright Sidney Robertson Cowell. Cowell Collection at the NYPL. Used with permission.

Some of the best sources — family, friends, and associates — could only be used with extreme caution. Contrary to long-lived rumors that Mrs. Cowell wanted to whitewash his life, she was so determined that a biography be accurate that she set down, on paper or on tape, an endless stream of memos and recollections. She must have typed continuously for 30 years! I knew her well enough to be convinced that she was incapable of lying. Some extremely negative statements reinforced my faith that she didn’t want to fabricate a false, glowing image of him but simply to make his amazing and selfless life, and his music, known again. It became tempting to take everything at face value, but that would have been a huge mistake. Serious questions arose as to whether her memories were accurate, especially when they were written as much as half a century after the events. Sometimes she would comment that she might be mis-recollecting; at other times she wrote with great assurance, even though she occasionally contradicted an earlier observation or unimpeachable evidence in the Cowell papers. Although I tried to avoid using statements that couldn’t otherwise be verified, many are unique sources for important facets of his life.

Two important sources of Henry Cowell’s own statements suffer from related problems. One of them is his witty, off-the-cuff lecture-recital, “Autobiography of a Composer,” which he delivered to great acclaim for more than 30 years, winning universal plaudits because of the nature of his career and his deadpan humor. Unfortunately, the only written version of it stems from the end of his life, when he had had several strokes. It is very difficult to determine whether some of the events that he described happened as recalled, or whether he had unconsciously been elaborating them over the years. (Sidney said that he never lied, but liked a good yarn.) The same is true of his 1962 interviews for the Columbia Oral History project, including priceless stories of his tennis games with Schoenberg. Although Nuria Schoenberg Nono told me that the general outline is doubtless true, the amusing details are unverifiable. In the end, although some stories were irresistible, I had to omit others, and always cautioned that some salt might be necessary. Even if those recollections were only “good yarns,” they illuminate his lovable personality.

How much easier it would have been if Henry Cowell had had fewer adventures, fewer accomplishments, and if all the information were clearly correct. And what a more monochrome tale it would have made.

Joel Sachs is Professor of Music History, Chamber Music, and New Music Performance at The Juilliard School, where he conducts the New Juilliard Ensemble. He is the author of Henry Cowell: A Man Made of Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Theirs to reason why? Literature, philosophy, and war

On the eve of the battle of Borodino, Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, one of the main characters in War and Peace and, in that scene at least, Tolstoy’s mouthpiece, describes war as follows:

But what is war? What is needed for success in warfare? … The aim of war is murder; the methods of war are spying, treachery, and their encouragement, the ruin of a country’s inhabitants, robbing them or stealing to provision the army, and fraud and falsehood termed military craft. … [Soldiers] meet, as we shall meet tomorrow, to murder one another; they kill and main tens of thousands, and then have thanksgiving services for having killed so many people (they even exaggerate the number) and they announce a victory, supposing that the more people they have killed the greater their achievement…

Compare with Wilfred Owen’s well-known rejection of the romanticism of war in Dulce and Decorum est.

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

For both Tolstoy and Owen, war really is about individuals maiming and killing each other, and it is precisely that which elicits the former’s cold fury and the latter’s bitter anger. And yet, it seems that war is also irreducibly collective: it is fought by groups of people and more often than not, as Owen himself painfully reminds us, for the sake of communal values such as territorial integrity and national self-determination.

The tension between the individual and the collective dimensions of war is nowhere more evident than in the ways in which the laws of war, and the moral norms which underpin those laws, treat soldiers and civilians. On the one hand, however unjust the cause for which they fight, soldiers are not to be held responsible for their participation in it, subsumed as they are under the group to which they belong – their country’s army – nor are they to be condemned for killing enemy soldiers. As Alfred Lord Tennyson famously has it in “The Charge of the Light Brigade” : ‘Theirs not to make reply, Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to do and die.’ By implication, as soldiers, and simply in virtue of belonging to that category, they are legitimate targets. On the other hand, soldiers may not deliberately kill innocent civilians, however just their war and however explicitly they might be ordered to do so: for that they are clearly and unambiguously responsible. By implication, civilians are not legitimate targets, simply in virtue of being civilians, and irrespective of what they actually do for the war.

Those two questions (whether the justness or unjustness of their cause makes any difference to soldiers’ permission to kill one another, and whether civilians who take part in the war are legitimate targets) are at the heart of the revival of the just war tradition in contemporary moral and political philosophy – a revival which started with the publication of Walzer’s seminal Just and Unjust Wars in 1977 and which has gone from strength to strength as leading philosophers have entered the fray.

Walzer sought to defend the tradition (though he did allow that civilians who work in munitions factory are legitimate targets.) Recently however, the tradition’s account of the moral status of soldiers and civilians during war has come under sustained attack. On that more recent view, the thesis that soldiers qua soldiers are legitimate targets whilst civilians qua civilians are not is profoundly at odds with a fundamental principle of morality, to wit, that whether or not individuals are liable to being killed is dependent both on what they do, as opposed to who they are, and on the moral status of their action. If Alan attempts to kill Bob at time t1 without just cause, and if Bob manages momentarily to thwart him at t2 by, e.g., shooting at him, we would certainly say that Alan is liable to being shot out, in virtue of wrongfully attacking Bob. Moreover, we would certainly not deem it permissible for Alan to kill Bob at t3 in his own defence: Alan, we would think, ought to stop attacking Bob. Why not hold soldiers up to the same standards of morality? Why not insist, then, that soldiers who kill in prosecution of an unjust cause, such as an unwarranted aggression on another country’s territory, act wrongly when so acting? By that token, civilians who make a significant contribution to an unjust war, though they are not themselves carrying out acts of killing, might also, at least at first sight, be legitimate targets. If Don Corleone orders Luca Brazzi to kill a member of the Tattaglia family, and if the only way for the latter to save his life is by killing Corleone, it seems that he may do so. If Charles gives a gun to Alan in the foreknowledge that Alan will use it to kill Bob unwarrantedly, and if the only way for Bob to save his life is by killing Charles, it seems that he may do so. Likewise, it would seem, with civilians.

Walzer sought to defend the tradition (though he did allow that civilians who work in munitions factory are legitimate targets.) Recently however, the tradition’s account of the moral status of soldiers and civilians during war has come under sustained attack. On that more recent view, the thesis that soldiers qua soldiers are legitimate targets whilst civilians qua civilians are not is profoundly at odds with a fundamental principle of morality, to wit, that whether or not individuals are liable to being killed is dependent both on what they do, as opposed to who they are, and on the moral status of their action. If Alan attempts to kill Bob at time t1 without just cause, and if Bob manages momentarily to thwart him at t2 by, e.g., shooting at him, we would certainly say that Alan is liable to being shot out, in virtue of wrongfully attacking Bob. Moreover, we would certainly not deem it permissible for Alan to kill Bob at t3 in his own defence: Alan, we would think, ought to stop attacking Bob. Why not hold soldiers up to the same standards of morality? Why not insist, then, that soldiers who kill in prosecution of an unjust cause, such as an unwarranted aggression on another country’s territory, act wrongly when so acting? By that token, civilians who make a significant contribution to an unjust war, though they are not themselves carrying out acts of killing, might also, at least at first sight, be legitimate targets. If Don Corleone orders Luca Brazzi to kill a member of the Tattaglia family, and if the only way for the latter to save his life is by killing Corleone, it seems that he may do so. If Charles gives a gun to Alan in the foreknowledge that Alan will use it to kill Bob unwarrantedly, and if the only way for Bob to save his life is by killing Charles, it seems that he may do so. Likewise, it would seem, with civilians.

One cannot underestimate how profoundly revisionist that view is. (Though it in fact resurrects the scholastic thought, as found notably in Vitoria’s writings, that ordinary soldiers can, at least sometimes, be expected not to fight for an unjust cause.) Put bluntly, it implies that the acts of killing committed by German soldiers in prosecution of Germany’s wrongful aggression against Belgium and France in 1914 were akin to acts of murder. It also implies that civilian leaders who take their country into an unjust war are legitimate targets – that, for example, if the 2003 war against Iraq was indeed unjust, then Iraqi forces would not have been guilty of wrongdoing towards then-Prime Minister Blair, let alone President Bush, had they killed them.

The view that leaders or weapons manufacturers who, respectively, authorize the war and supply troops are liable to being killed might not prove disquieting to many. But the claim that soldiers ought not to participate in an unjust war, and that their acts of killing, if they do participate, are wrongful in virtue of the unjustness of the war, has elicited considerable criticism from many moral philosophers, on two grounds (e.g., Walzer, 1977). Soldiers, it is often said, act under duress: they are ordered to go to war, and should therefore be seen as instruments of the state rather than autonomous agents. Moreover, it is also often said, soldiers are not capable of discerning whether the war which they are ordered to wage is a just war — indeed, they ought not to be expected to engage in such a reflective process — and it is unfair, therefore, to hold them responsible for their participation in it.

And yet, as some of the aforementioned proponents of the revisionist account have noted, the duress and the epistemic objections to holding ordinary soldiers responsible for their participation in an unjust war prove too much for they are thereby committed not to hold soldiers responsible for wrongful acts of killing committed under orders against civilians. Put differently, exonerating soldiers who are safely ensconced in their barracks from the burden of reaching a judgement as to the justness of the war and of acting on that judgement, while requiring of them that they reflect on the moral status of the orders they are given in the heat of battle, seems incoherent. Likewise, it is incoherent to deem them bound by an order wrongfully to cross the border into a neutral country and kill enemy soldiers who resist their ex hypothesi wrongful aggression, and at the same time to impose on them a moral and legal obligation to disobey an order deliberately to kill innocent civilians.

And so if the horror of war resides in what it leads individuals do to each other, as Tolstoy and Owen tell us, then it must be morally appraised as the concatenation of individual acts, committed by individual agents whom it is appropriate, much more often than is standardly thought, to regard as morally responsible for what they do – be they soldiers or civilians. Tennyson had got it wrong: it is theirs to reason why.

This article originally appeared in Oxford Philosophy Magazine.

Cécile Fabre is Professor of Political Philosophy at the University of Oxford, and a Fellow of Lincoln College. Her latest book, Cosmopolitan War, published in September 2012. She has written extensively on distributive justice, rights, and the ethics of killing. She has previously published two monographs with Oxford University Press: Social Rights under the Constitution (2000) and Whose Body is it Anyway? (2006). She is a Fellow of the British Academy.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Remembrance Day Red Poppy by NuStock, iStockphoto.

September 19, 2012

Do birds and fowls fly?

An etymologist is constantly on the lookout for so-called motivation. Why is a cat called cat, and why do English speakers say tree if the Romans called the same object arbor? As everybody knows, the “ultimate truth” usually escapes us. Once upon a time (about five thousand or even more years ago?) in a hotly debated locality there lived the early Indo-Europeans, and we still use words going back to their partly unpronounceable sound complexes. Close to the end of the nineteenth century, some brave scholars traced Engl. girl to the Indo-European form ghwerghu. The word sounds like something invented by Jonathan Swift, but even if it ever existed (I hope it never did) and could be whispered by a loving mother in addressing her baby girl, we would still not know why just this combination of consonants and vowels designated a female child.

My immediate concern in this post is the origin of the word fowl – not because it is such an important word but because attempts to find its “motivation” are instructive. In the past, fowl had the form fugol and meant “bird.” Dutch and German vogel ~ Vogel have retained the old meaning, and their Scandinavian cognates sound very much like fugol (compare Old Icelandic fugl). Engl. bird has no cognates either in Germanic or outside it and is usually dismissed in dictionaries as a word of unknown origin, though conjectures on its etymology abound. If my reconstruction is right, bridd “young bird” (such are the oldest attested form and sense of bird) meant “a born creature; animal” and is related to Engl. birth and Scots birky “child; fellow.” But why fugol was pushed from the center of the vocabulary to its periphery remains an unsolved mystery and in a way, the demotion of an old respectable word is a greater riddle than the emergence of bridd/bird. In present day English, fowl occurs mainly in connection with edible birds. However, such phrases as the fowls of the air (admittedly archaic), water fowl, and especially the alliterating triad neither fish, flesh, nor fowl (often reduced to neither fish nor fowl), remind us of the ancient sense of this noun.

Strangely, in many languages, the word for “bird” defies etymologists. Such is, among many others, Latin avis. The most appealing connection seems to be between avis “bird” and ovum “egg,” but it has been called into question, and for good reason. I cannot resist the temptation of quoting a line from Henry Cecil Wyld’s The Universal Dictionary of the English Language, which I often use and like very much: “…it is doubtful whether ‘egg’ or ‘bird’ is the primary meaning of the base” (the entry ovum; the reconstructed base, or root, is ówjon, in which both vowels are long). This is what editors sometimes call unconscious humor. While stating his opinion, Wyld did not hear that he rephrased the famous question about the chicken and the egg. Which comes first?

The story I decided to tell today has an important point, namely that the words for “bird” and “fly” are very seldom related. The case of Finnish lintu “bird” and lentää “fly” is an exception. And yet we define bird as a flying animal! Almost as though to mock us, in English a flying animal is the fly, not the bird (the same happens in German: fliegen and Fliege; English lost endings long ago, and that is why the noun and the verb are now homonyms). As a general rule, the two words have nothing in common: compare Latin avis “bird” and volare “to fly” (French oiseau and voler), Russian ptitsa (we will make use of it later) and letet’ (stress on the second syllable), Hungarian madár and szállni. Strange as it may seem, to our remote ancestors flying did not seem to be the most conspicuous feature of birds. Perhaps it happened because all kinds of insects also have wings or because the world of the ancients was thickly populated by supernatural flying creatures, as we know from the mythology of all races and the presence of angels in Christian tradition.

In this light it is instructive to observe how etymologists tried to explain the Germanic word for “fowl.” The reconstructed principal parts of the verb fly are fleugan—flaug (preterit singular)—flugun (preterit plural)—flugnaz (past, or perfect, participle). All strong verbs had four principal parts, a system of which Engl. be—was—were—been reminds us to this day. Allegedly, the noun fowl (traceable to fuglaz) derives from a form having the same structure as flugnaz (it is given in bold above). According to an old and attractive etymology, codified in the most authoritative dictionaries of the not too remote past, the form fuglaz developed from fluglaz, in which the first l was lost because of dissimilation, a common process in human speech (here, of two l’s in succession the first supposedly dropped out). If we look at the history of the English verb fledge, we will see that it goes back to fluggja. The German adjective flügge “fledged” and its Old English cognate reproduce fluggja almost to a letter. Old English also had the adjective flugol “fleeing.” The words for “fowl” and “fly” sounded so much alike that in the late history of German Gefügel “fowl” (collective) became Geflügel.

However, fluglaz has not been recorded, and, as noted, people did not seem to think that flying distinguished birds strongly enough to serve as the “motivation” for their name. The fuglaz/fluglaz etymology has been all but abandoned. In the more recent dictionaries one can read that the Indo-European root of fowl, from fuglaz, was pu- (because in the Germanic languages f corresponds to non-Germanic p, as in father ~ pater), known from Latin puer “boy,” pullus “hen,” putila “little bird,” many other similar words, and, surprisingly to the uninitiated, Russian ptitsa “bird,” mentioned above (it once had a kind of i between p and t). All of them denote small creatures. If fuglaz belongs with them, it must have had the sense “birdie.” But of course there is -g- (some suffix of unclear meaning) and -l- (a diminutive suffix?) before the ending -az. This is not a shining etymology, but perhaps it is better than the one that depends on the unrecorded form fluglaz.

An extension of the pu- etymology has been offered in Slavic studies and remained unnoticed by Germanic researchers. I cannot vouch for its correctness. My aim is to let it leave the obscurity of Russian publications. Early German vogel ~ fugel meant “embryonic spot in an egg.” This meaning may have been secondary and arisen when it was recorded but may have only surfaced so late. O. N. Trubachëv (it rhymes with Gorbachev; stress on the last syllable), the main Russian etymologist of the last fifty years (he died not too long ago), compared German vogel ~ fugel, Russian dialectal puga “the larger end of the egg” (I am sorry to conjure Swift’s spirit again), and both of them with Greek pygé “buttocks.” If puga ~ pygé are related to fowl, from fuglaz, this circumstance can breathe new life into the discussion of an old problem, and then, much to our joy, the bird and the egg will meet again.

The pictures below will convince the skeptics that birds, unlike the best etymologies, indeed do not fly.

Ostrich versus emu. Who can fly?

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Ostrich (Struthio camelus) at Colchester Zoo. Photo by Keven Law. Creative Commons License. Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) in Texas. Photo by Jak via Wikimedia Commons.

Karl Lagerfeld

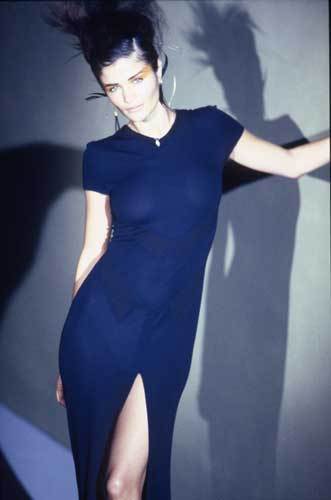

Karl Lagerfeld S/S 97, photograph by Niall McInerney, Bloomsbury Fashion Photography Archive. Used with permission.

Karl Lagerfeld: a name synonymous with high fashion and discerning taste, a name that also sends shivers down the spines of those that fall victim to his quick wit and cutting criticism. In the midst of Fashion Week chaos, Lagerfeld celebrated his birthday on September 10th. As he nears the end of his seventieth decade, 2013 will be a year to remember for one of the most iconic and important men in contemporary fashion.The Berg Fashion Library looks back at his numerous achievements that span decades and design houses with a free article documenting his outstanding career in the fashion industry. To whet your appetite, this photograph from the Bloomsbury Fashion Photography Archive comes from one of Lagerfeld’s earliest shows for his own label. Taken during Lagerfeld’s Spring/Summer 1997 collection, supermodel Helena Christensen wears a figure-hugging navy gown, exuding ease and elegance.

The early 90s were a period of transition for Lagerfeld as he notoriously lost over 100 pounds in weight so that he could wear one of fellow designer Hedi Slimane’s skinny suits, which now have become part of his iconic, signature style.

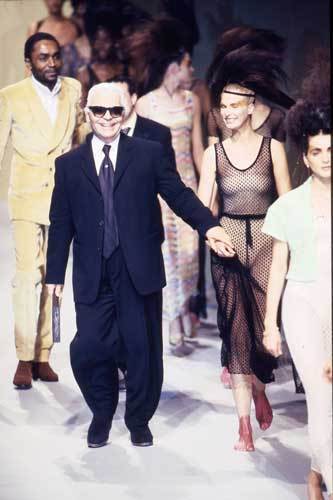

Karl Lagerfeld S/S 97, photograph by Niall McInerney, Bloomsbury Fashion Photography Archive. Used with permission.

Another rare photograph from Bloomsbury’s Fashion Photography Archive of the man himself taken during the finale of his Spring/Summer 1997 show shows his sunglasses and slicked-back hair are present as ever. Already a major player in the fashion world at this time, his dedication to fashion is still unparalleled. Turning eighty next year, he maintains his position as a doyen of contemporary style and remains a formidable fashion force to be reckoned with.Emily Ardizzone is the Editorial Assistant at Berg Publishers, an Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing, with responsibility for the Berg Fashion Library and other fashion projects including the recently acquired Fashion Photography Archive. Read previous Berg Fashion blog posts.

Informed by prestigious academic and library advisors, and anchored by the 10-volume Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, the Berg Fashion Library is the first online resource to provide access to interdisciplinary and integrated text, image, and journal content on world dress and fashion. The Berg Fashion Library offers users cross-searchable access to an expanding range of essential resources in this discipline of growing importance and relevance and will be of use to anyone working in, researching, or studying fashion, anthropology, art history, history, museum studies, and cultural studies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

September 18, 2012

Connecting with Law Short Film Competition Winners

We’re pleased to share the winning entries to Oxford University Press Australia and New Zealand’s annual film competition for law students. Now in its fifth year, the Connecting with Law Short Film Competition 2012 was open to all students currently enrolled in an Australian law school.

To enter, students chose at least one definition from the Australian Law Dictionary and created a two-to-five minute film based around the definition/s to educate and help students connect with the law. The winners were those judged to be the most creative, instructive, and original.

Winner of the Connecting with Law Short Film Competition 2012 : Bearly Legal

Julian Chant & Louis Aldred-Traynor (University of Melbourne and University of Notre Dame, Sydney)

Click here to view the embedded video.

Second Prize in the Connecting with Law Short Film Competition 2012 : You Better Watch Out

Jordan Tutton, Reuben White, James Trezise, Georgina Landon, Hannah Maccini, Cassie Byrnes & Jack Gillespie (Flinders University)

Click here to view the embedded video.

Third Prize in the Connecting with Law Short Film Competition 2012 : Snow Flake and the Huntsman

Louis Tang, Suet Yoong Leong, Yun Wei Wong & Ngoc Linh Pham (University of Adelaide)

Click here to view the embedded video.

The judges also selected three commendable films. All the students involved have won an OUP book voucher.

Puff Daddy

Ross Paull (University of New South Wales)

Marriage

Skye O’Dwyer, Jordan Sanderson, Scott Leary, Anneka Frayne, Ashleigh Schiemer, Peter Martin, Erin Garty, Kate Simpson, Peta Lisle & Savanna Stewart (University of New England)

Will of Fortune

Elly Brand, Allana Neumann & Gerard Forrest (University of Queensland)

The Australian Law Dictionary is the best reference for those who want familiarity with, and knowledge of, Australian legal terms. Designed in response to research, the ALD is structured to ensure comprehensive coverage of core legal content. Readers are encouraged to learn the meaning of a particular term, link it with any related concepts, and locate it within the larger body of law. it is the winner of the Australian Educational Publishing Award for Tertiary (Wholly Australian) Teaching and Learning 2010. Trisha Mann, the editor, has a BA and an LLB from the Australian National University, and a Graduate Diploma in editing and publishing from RMIT, and in Managing Legal Organisations from the University of Melbourne. She is currently undertaking a PhD in judicial education at the University of Melbourne.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers