Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1019

September 25, 2012

Context clues in the American presidential campaigns

By Sandy Maisel

Presidential campaign watching is a great American game. Did Romney respond correctly when challenged on why he failed to mention our men and women in uniform in his convention speech? Does President Obama really like hanging out in sports bars and receiving giant bear hugs from pizza shop owners? How big was the Obama convention bounce and what does it mean?

However, those of us who view election watching as our favorite quadrennial sport are in a minority. Hard for us to believe, but true. The average American, and certainly the average citizen of the world, wants to know what’s going on in the presidential election, but not all that much. The day-to-day drumbeat of stories is wearing; they all start to sound the same. What do they really mean?

Separation of powers and a federal system. While Americans are electing a President on November 6th, we are also electing the entire House of Representatives and one-third of the United States Senate (and many state and local officials). These elections are all held on the same day, but citizens frequently vote for a candidate of one party for one office and of another party for another office. It is not only conceivable, but likely, that the election will result in a President of one party, one house of Congress controlled by his party, and the other house by the other party. Few legislators will feel beholden to their party’s presidential candidate for their victory — and this conclusion is equally true of Democrats to Obama and Republicans to Romney.

Listen to the campaign rhetoric. How often do you hear either presidential candidate urging voters to send him a Congress of his party. In point of fact, the public holds the Congress in very low esteem — the approval rating of the Congress has been at record low numbers for many months — so the presidential candidates more often than not try to distance themselves from their colleagues in the Congress.

The Electoral College. The presidential election is an indirect vote. As we saw in 2000, and three earlier times in our history, one candidate can win the popular vote while the other candidate wins the electoral vote. That is possible because the election is in fact 51 separate state elections (50 states plus the District of Columbia). Every state except for Maine and Nebraska gives all of its electoral votes to the plurality winner in that state. Thus, if one candidate wins many states narrowly, while the other candidate wins fewer (or smaller) states by wide margins, the electoral vote winner — and thus the new President — may well have received fewer votes than his opponent.

As a consequence, candidates spend an inordinate amount of time in relatively few states. With minor variations, those states remain the same from election to election. This year the emphasis has been and will be on New Hampshire in New England; Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida in the South; Ohio, Iowa, and Wisconsin in the Midwest; Colorado in the Mountain States; and Nevada in the West. If you live in one of those states, the campaigns for President are ubiquitous. If you live Alabama or Mississippi, New York or New Jersey, Illinois or Minnesota, California or Washington, or most of the other states, you will see few television ads, few candidate appearances, and the campaigns will seem all but invisible. (Some states are at the margins of candidate interest, e.g. Pennsylvania or Michigan, but the pattern is clear.) This emphasis may seem undemocratic to some, especially to non-Americans, and I would not disagree. But in observing the election, it is important to understand the context as it exists, not as it should exist.

Voter turnout. For Americans, voting is a right or a privilege, not an obligation. In fact, affecting turnout is an important campaign strategy. Each party tries to energize its base of supporters to vote; some claim that parties also try to discourage the other party’s supporters from voting. Democrats claim that voter suppression, not fraud reduction, is the goal of Republican efforts to make it more difficult for voters to cast their ballots.

Nate Silver of the New York Times predicts that if all registered voters actually voted, President Obama would receive approximately 4-5% more of the two-party vote than he will actually receive. But we know that fewer than 60% of eligible voters will in fact cast ballots on November 6th. Again, you can question if this is good or bad — well, actually it is hard to argue that it is good — but what is important is to understand that low turnout is a fact and has electoral consequences.

Viewing the 2012 election with these few contextual facts in mind makes understanding the campaigns’ strategies somewhat easier. When observing the election, don’t just focus on what a candidate is saying, but also think about why he is saying it and where he is saying it. The strategies will quickly become much clearer.

L. Sandy Maisel is the William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Government, Colby College, Waterville, Maine and author of American Political Parties and Elections: A Very Short Introduction. A former candidate for Congress, Maisel is the author or editor of 15 books on political parties and elections and is a frequent commentator on contemporary politics.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

New BBC drama ‘The Paradise’ & Oxford World’s Classics

Tonight sees the start of a major new drama series on BBC 1, The Paradise. Adapted from Zola’s novel The Ladies’ Paradise (Au Bonheur des Dames) and set against the backdrop of the spectacular rise of the department store in the 1860s and 70s, the story follows the fortunes of a young girl from the provinces who starts work as a salesgirl in the shop, and her entanglement with the charismatic owner. The model for the store in Zola’s novel, set in Paris, is the Bon Marché, but there were parallel developments in the explosion of retail opportunities in the United States and England, and the BBC has relocated the action to the north of England.

There is a great cast of characters, a powerful love story, all the social intrigue of the staff’s relationships and rivalries, as well as some fascinating comparisons with modern-day retail practices: Mouret (Moray in the television adaptation), the business genius behind the shop’s success, is an arch manipulator who uses every marketing trick in the book to seduce his female customers, and tramples over smaller rivals on the way. Oxford World’s Classics is delighted to publish the tie-in edition of Zola’s novel, in a compelling translation by Brian Nelson. In this extract from chapter two, Denise has arrived for her interview with the formidable head of Ladieswear, Madame Aurélie (played by Sarah Lancashire as Miss Audrey in the TV series):

Denise had not dared before to venture into the silk hall; its high glazed ceiling, sumptuous counters, and church-like atmosphere frightened her. Then, when she had at last gone in, to escape the grinning salesmen in the linen department, she had stumbled straight into Mouret’s display; and though she was scared, the woman in her was aroused, her cheeks suddenly flushed, and she forgot herself as she gazed at the blazing conflagration of silks.

‘Hey!’ said Hutin crudely in Favier’s ear, ‘It’s the tart we saw in the Place Guillon.’

Mouret, while pretending to listen to Bourdoncle and Robineau, was secretly flattered by this poor girl’s sudden fascination with his display, as a duchess might be by a brutal look of desire from a passing drayman. But Denise had raised her eyes, and she was even more confused when she recognized the young man she took to be the head of a department. She thought he was looking at her sternly. Then, not knowing how to get away, quite distraught, she once again approached the nearest assistant, who happened to be Favier.

‘Could you tell me where I can find Madame Aurélie, please?’

Favier gave her an unpleasant look and replied curtly:

‘On the mezzanine floor.’

Denise, anxious to escape from all these men who were staring at her, thanked him and was once more walking away from the staircase she should have climbed, when Hutin yielded to his natural instinct for gallantry. He had called her a tart, but it was with his most amiable salesman’s smile that he stopped her.

‘No, this way, miss … If you would be so good as to…’

He even went with her a little way to the foot of the staircase in the left-hand corner of the hall.

There he bowed slightly, and smiled at her with the smile he gave to all women.

‘Upstairs, turn left … The ladieswear department is straight ahead.’ […]

‘You’re too kind … Please don’t trouble … Thank you so much, sir …’

Hutin had already rejoined Favier, to whom he said under his breath, in a crude tone:

‘She’s skinny, eh!’

Upstairs the girl found the ladieswear department straight away. It was a vast room with high cupboards of carved oak all round, and plate-glass windows facing the Rue de la Michodière. Five or six women in silk dresses, looking very smart with their chignons curled and their crinolines sweeping behind them, were moving about, talking to each other. One of them, tall and thin, with an elongated head which made her look like a runaway horse, was leaning against a cupboard, as if she was already tired out.

‘Madame Aurélie?’ Denise repeated.

The saleswoman looked at her without replying, with an air of disdain for her shabby dress; then, turning to one of her companions, a short girl with a pasty complexion, she asked in an artless, wearied manner:

‘Mademoiselle Vadon, do you know where Madame Aurélie is?’

The girl, who was in the process of arranging long cloaks in order of size, did not even take the trouble to look up.

‘No, Mademoiselle Prunaire, I don’t know,’ she said rather primly.

A silence ensued. Denise stood there, and no one took any further notice of her. However, after waiting a moment she plucked up enough courage to ask another question.

‘Do you think Madame Aurélie will be back soon?’

Then the assistant buyer of the department, a thin, ugly woman whom she had not noticed, a widow with a prominent chin and coarse hair, called to her from a cupboard where she was checking price tickets:

‘You’ll have to wait if you want to talk to Madame Aurélie personally.’

And, addressing another saleswoman, she added:

‘Isn’t she in the reception office?’

‘No, Madame Frédéric, I don’t think so,’ the girl replied. ‘She didn’t say anything; she can’t be far away.’

Denise remained standing. There were a few chairs for customers, but as no one told her to sit down she did not dare to take one, although she felt that her legs might drop off with fatigue. These young ladies had clearly sensed that she was a salesgirl coming to apply for a job, and they were staring at her, stripping her naked, out of the corners of their eyes, with the veiled, ill-natured hostility of people seated at table who do not like moving up to make room for those outside who are hungry. Her embarrassment grew; she crossed the room very quietly and looked out into the street, just for something to do. Just opposite, the Vieil Elbeuf with its rusty frontage and lifeless windows seemed to her so ugly, so wretched, seen thus from the luxury and life of her present vantage-point, that her heart was wrung with something akin to remorse.

‘I say,’ whispered tall Mademoiselle Prunaire to little Mademoiselle Vadon, ‘did you see her boots?’

‘And her dress!’ murmured the other.

Émile Zola was the leading figure in the French school of naturalistic fiction, of which Thérèse Raquin (1867) is his earliest example. The first volume (La Fortune des Rougon) of his principal work, Les Rougon‐Macquart, which he termed the ‘natural and social history of a family under the Second Empire’, appeared in 1871; in 19 more volumes (including L’Assommoir, 1877; Germinal, 1885; La Terre, 1887; La Bête humaine, 1890; La Débâcle, 1892), Zola produces an extraordinary panorama of mid‐19th‐cent. misery, poverty, and the violence of human instinct. The Ladies’ Paradise (Au Bonheur des Dames) was published in 1883 and is the eleventh novel in the series.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Henry Cowell’s imprisonment

Many people begin a conversation about Henry Cowell by telling me why he spent four years in San Quentin. Although I prefer to dwell on Cowell’s enormous accomplishments as a composer, theorist, performer, and educator, there is no need to run from the matter.

The misinformation begins with the idea that he was convicted of a morals charge. He was not convicted; there was no trial. Cowell, who did not trust lawyers, pleaded guilty without advice of counsel, to the accusation that he had engaged in a single act of oral sex. No one had ever been prosecuted under the relevant law and the district attorney doubted that Cowell would have been either. Unfortunately, as he put it, Cowell’s plea set the wheels of justice rolling and there was no way to stop them.

Cowell was accused of violating section 288a of the penal code, which made oral sex punishable by one to fifteen years in prison. Both participants were to be prosecuted; homosexuality isn’t mentioned. The other participant was a young adult, part of a crowd of youths that Cowell had allowed to build a swimming pool in his back yard. The young man with whom he had oral sex was never arrested; he later said was to have been attempting to blackmail Cowell to get him to turn over his car. A claim that Cowell had been set up because of his leftist sympathies was a fantasy of his communist friends.

Cowell’s first problem was the press. The local Hearst paper made the arrest a front-page, banner headlined story. Another newspaper printed vicious attacks on Cowell after failing to blackmail him. The press coverage reduced any probability of mercy.

At the sentencing hearing, the discussion revolved almost entirely around homosexuality, despite not being mentioned in the law. Even a prison psychiatrist spoke in favor of probation, emphasizing his belief that Cowell wasn’t truly homosexual. Unfortunately, the local probation officer alluded to a similar incident (of questionable relevance and amicably disposed of) in another community many years earlier, and proclaimed Cowell incurable. In an awkward position because the law offered only prison or probation, but not counseling, the judge felt compelled to respect the probation officer’s judgment and commit Cowell to prison.

The final decision about the length of imprisonment was made by the Board of Prison Terms and Paroles — a group of unqualified political appointees, not the court — at the end of the minimum term, which was one year. Sentencing Cowell to the fifteen years reflected their “gut” reaction to a case blown out of proportion by ongoing hysteria about sex criminals. Constant attempts to win parole garnered enormous support but the three Board members were true hardliners. Cowell’s prospects finally changed in 1938 when a new governor addressed the scandalous conditions in the California penal system and replaced the Board. In 1940, he was paroled after spending four years in San Quentin.

There he had written a theoretical treatise and numerous articles, composed as much as time allowed, and gave music classes to thousands of inmates. His performances won him the respect and admiration of many prisoners, and the protection of the ranking murderer in the prison — the violinist-conductor of the prison band. His more than 200 visitors included celebrities like Percy Grainger and Martha Graham. Cowell never complained, but while his placidity was a mark of his extraordinary character, all prisoners knew that guards liked to beat up complainers. The one fear he expressed was that he and his music would be forgotten.

When Cowell was offered an important job in the war effort, he couldn’t accept it without being pardoned. His new wife Sidney Robertson then undertook the huge job of campaigning for the pardon. Although everyone — including the hearing judge and the district attorney — signed on to the pardon, Governor Olson declined to consider the application. Sidney then called in the heaviest of her heavyweights, who asked the governor to give it a chance and at least read it. Henry Cowell was issued the pardon just before Olson left office at the end of 1942.

Regrettably, the whispering about him persists to this day.

Joel Sachs is Professor of Music History, Chamber Music, and New Music Performance at The Juilliard School, where he conducts the New Juilliard Ensemble. He is the author of Henry Cowell: A Man Made of Music. Read his previous blog post: “Unravelling the life of Henry Cowell without unravelling the biographer.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

September 24, 2012

Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age camel

On 24 September 1896, F. Scott Fitzgerald was born. While remembered today for his masterpiece The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald made his living off short stories. He chronicled life of the 1920s and 30s with unparalleled versatility, whether as parody, tragedy, fantasy, or romance. His attitude to the charisma and vices of America’s privileged was complex and often ambivalent. This dichotomy is reflected in the following excerpt from “The Camel’s Back.”

A grunt from the hump acknowledged this somewhat dubious compliment.

“Honestly, you look great!” repeated Perry enthusiastically. “Move round a little.”

The hind legs moved forward, giving the effect of a huge cat-camel hunching his back preparatory to a spring.

“No; move sideways.”

The camel’s hips went neatly out of joint; a hula dancer would have writhed in envy.

“Good, isn’t it?” demanded Perry, turning to Mrs. Nolak for approval.

“It looks lovely,” agreed Mrs. Nolak. “We’ll take it,” said Perry.

The bundle was stowed under Perry’s arm and they left the shop. “Go to the party!” he commanded as he took his seat in the back. “What party?”

“Fanzy-dress party.” “Where’bouts is it?”

This presented a new problem. Perry tried to remember, but the names of all those who had given parties during the holidays danced confusedly before his eyes. He could ask Mrs. Nolak, but on looking out the window he saw that the shop was dark. Mrs. Nolak had already faded out, a little black smudge far down the snowy street.

“Drive uptown,” directed Perry with fine confidence. “If you see a party, stop. Otherwise I’ll tell you when we get there.”

He fell into a hazy daydream and his thoughts wandered again to Betty — he imagined vaguely that they had had a disagreement because she refused to go to the party as the back part of the camel. He was just slipping off into a chilly doze when he was wakened by the taxi-driver opening the door and shaking him by the arm.

“Here we are, maybe.”

Perry looked out sleepily. A striped awning led from the curb up to a spreading gray stone house, from which issued the low drummy whine of expensive jazz. He recognized the Howard Tate house.

“Sure,” he said emphatically; “ ’at’s it! Tate’s party to-night. Sure, everybody’s goin’.”

“Say,” said the individual anxiously after another look at the awning, “you sure these people ain’t gonna romp on me for comin’ here?”

Perry drew himself up with dignity.

“ ’F anybody says anything to you, just tell ’em you’re part of my costume.”

The visualization of himself as a thing rather than a person seemed to reassure the individual.

“All right,” he said reluctantly.

Perry stepped out under the shelter of the awning and began unrolling the camel.

“Let’s go,” he commanded.

Several minutes later a melancholy, hungry-looking camel, emitting clouds of smoke from his mouth and from the tip of his noble hump, might have been seen crossing the threshold of the Howard Tate residence, passing a startled footman without so much as a snort, and heading directly for the main stairs that led up to the ballroom. The beast walked with a peculiar gait which varied between an uncertain lockstep and a stampede — but can best be described by the word “halting.” The camel had a halting gait — and as he walked he alternately elongated and contracted like a gigantic concertina.

Often overshadowed by his major novels, Fitzgerald’s short stories demonstrate the same originality and inventive range, as he chronicles with wry and astute observation the temper of the hedonistic 1920s. Oxford offers the only critical edition of Tales of the Jazz Age available in paperback as first published. Editor and Fitzgerald scholar Jackson R. Bryer provides an in-depth appreciation of the stories and examines the making of the volume and its reception.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Immigration policy debates in the 2012 election

Popular concern about US immigration policy has increased dramatically over the past two decades. During this period, the resources and technologies for enforcement of immigration law have also increased considerably. The remainder of US immigration policy — particularly questions of how many immigrants the United States should admit, who should be eligible to immigrate, and what should be done about immigrants resident in the United States who reside in the country without legal status — see much less consensus. President Obama and Governor Romney propose starkly different immigration policies, particularly on this final question of what to do about unauthorized immigrants resident in the United States.

In the 2008 presidential race, candidate Obama made a commitment concerning immigration that he didn’t fulfill. In that promise, however, can be found the roots of the 2012 Obama campaign’s approach to immigration policy. The promise was he would propose “comprehensive immigration reform” in his first year as president. The exact meanings of comprehensive reform weren’t defined, but broadly included additional enforcement particularly enforcement focused on employers, legalization for many of the unauthorized immigrants resident in the United States, guest worker programs, and perhaps, a change to the foundation of eligibility for legal immigration to the United States. The specifics proved irrelevant as Obama didn’t make immigration reform a priority in his first two years of office. In the next two years, Republican control of the House of Representatives made unlikely any major immigration legislation that could receive support from the Republican House majority and the Obama administration. Obama and the Democrats did seek to pass a limited form of legalization that targeted young adults who had been brought to the United States as children and had graduated from high school (the DREAM Act). Although this bill passed the House and received support from a majority of US Senators, it was unable to overcome a filibuster in the US Senate led by the Republicans.

Monumento a los migrantes muertos al cruzar la Línea, Tijuana-San Diego. Photo by Tomás Castelazo, 2006. Creative Commons License.

Realizing that comprehensive reform was unlikely, Obama increasingly used executive branch authority to focus enforcement efforts away from the young adults who would potentially benefit from the DREAM Act as well as away from unauthorized immigrants who had legal immigrant- or US citizen-family members. In the months before the election, the Obama administration established a two-year legal status that would allow young adults who had migrated without authorization to the United States as children to be able to remain in the country legally and to work. These efforts were criticized by advocates of immigration restriction, but serve as a core of the Obama approach to immigration in the 2012; Obama calls for an immigration system that is more “fair, efficient, and just.” These positions don’t reflect a move away from a call for comprehensive immigration reform, but instead a tactical recognition that, in the contemporary political environment, neither party will compromise on immigration. Obama also used the power of the presidency to oppose state laws that sought to use state police to enforce immigration law and to challenge these state efforts in the federal courts.

Going into the campaign, Governor Romney didn’t emphasize his positions on immigration policy. These included largely non-controversial positions such as using legal immigration to attract more highly skilled immigrants and to make guest worker programs more efficient for employers, with few specifics on how he would achieve either goal. The Republican Party primaries, however, shifted immigrant enforcement and support for state efforts to enforce immigration law to the center of the Romney immigration agenda. At the core of Romney’s positions is his support for “self-deportation,” the proposition that laws and public policy should make life so difficult for unauthorized immigrants to live in the United States that they will voluntarily return to the their countries of origin. Central to this notion of making life more difficult for the unauthorized is support for state laws to empower state and local authorities to enforce immigration law. Many states have passed such laws over the last several years. Perhaps the best known is Arizona’s SB 1070, which was the subject of Supreme Court review in 2012. Romney has also promised to veto the DREAM Act should it come to his desk as president.

The immigration debate between the two candidates, then, largely turns on the question of what to do about unauthorized migrants resident in the United States. Neither candidate has concrete positions on whether the standards for legal immigration — which results in more than one million immigrants to the United States each year — should be changed as some have proposed, or whether the United States should expand its programs to allow for short-term guest worker migrations to the United States (other than Romney’s call to make them more efficient). Each of these policy debates would need to be part of any serious reform of US immigration policy.

Louis Desipio is a Professor in the Departments of Political Science and Chicano/Latino Studies at the University of California, Irvine. His research interests include Latino politics, the process of political incorporation of new and formerly excluded populations into U.S. politics, and public policies shaping immigrant incorporation such as immigration, immigrant settlement, naturalization, and voting rights. He is the author of numerous scholarly books and articles including Counting on the Latino Vote: Latinos as a New Electorate (University of Virginia Press, 1996) and “Immigrant Incorporation in an Era of Weak Civic Institutions: Immigrant Civic and Political Participation in the United States.” (American Behavioral Scientist, 2011). He is also the author of the forthcoming article “Naturalization,” which will be included at the launch of Oxford Bibliographies in Latino Studies.

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Here’s to a wet New Orleans

In the aftermath of Hurricane Isaac, Jack Payne of Delacroix, which is a tiny fishing village in the wetlands of the Mississippi delta below New Orleans, explained to Bob Marshall of the Times-Picayune, that “Everything I rebuild will either be on pilings or wheels. It’s gotta be higher than storm surge, or something I can pull outta here. This is our future, man. We know it’s gonna happen again and again — and just get worse.” Marshall used his report on Payne as an opportunity to admonish his readers: “Storms like this are to New Orleans what blizzards are to Chicago and heat waves are to Phoenix. Get used to it — or move.”

The people of New Orleans used to be used to it. In the 1849 flood, probably the worst until the post-Katrina flood of 2005, certainly people carried on as if they were used to it. People donned outwear made of India rubber — what the locals called caoutchouc — and waterproof “California” boots, and trudged through the water. Elderly women propped themselves in front porch rocking chairs and knitted, their houses surrounded by three feet of water. Elderly men fished out windows. Young gentlemen rowed young ladies about on outings and sightseeing excursions through city streets. Children played with snakes. Not all was fun and games, of course. Hundreds fled the city, including many renters, though they faced lawsuits for breaking leases. Many lost all they owned to water damage. Food prices rose dramatically at local markets. The poor suffered the most because they lived in the lowest-lying areas, but all New Orleanians were inconvenienced, to say the least.

Still, they persevered, many with a smile. Under the heading “Yachting in the Inundated District,” The Daily Delta observed that surprisingly few had in fact left the city, none who had upper stories, and that everyone seemed resigned to the flood. Commenting at some distance on reports from the flooded city, an editor for the Savannah, Georgia Republican concluded that “The people of New Orleans, though doomed to a sort of amphibious existence, are not overwhelmed by the flood that threatens to submerge them. On the contrary, they bear the inconveniences of the present situation with a most commendable spirit, and exhibit a faculty of adapting themselves to circumstances.”

In centuries past, native inhabitants of the lower Mississippi Valley responded to periodic flooding by packing up and moving to higher ground, returning when the water receded, just as Jack Payne plans to do. In French colonial Louisiana, people set their homes on pillars, above tidal surges and spring floods. In the city, those who could afford it built two-storey homes and lived upstairs when necessary. They may never have gotten used to floods, but in the past few were surprised by them. Floods in New Orleans were, as Bob Marshall says, like blizzards in Chicago and heat waves in Phoenix.

So what happened to transform the people of New Orleans from environmental realists to dreamers? Engineers, urban planners, and politicians promised to keep the city safe from water, to make New Orleans permanently dry. And people bought it, in large part because those who made the promises delivered on them. Regular flooding ceased. The city flooded occasionally, of course, but occasional floods began to seem like avoidable accidents. A dry New Orleans became the new normal. Suburbs spread out into wetlands re-imagined in the new normal as dry lands. Houses came down to the ground because there was no need for stilts or second stories in a dry city. Shot-gun shacks on the ground or close to it became the new “traditional” style of home, although many eschewed tradition and built homes that looked just like those of suburban Chicago or Phoenix or any other dry American city. But New Orleans was not dry, never has been, never will be. Delacroix, not New Orleans, is what is normal.

However, there are some indications of change in New Orleans. The often-maligned Make It Right homes in the Lower Ninth Ward, also known as the Brad Pitt homes, came through Isaac all right. Like homes from earlier eras, they are elevated, although there was little flooding in the Lower Ninth this time, and they are sturdy. With Kevlar window covers, they are built to withstand high winds and blowing debris. A few of the homes were up and running when Hurricane Gustav hit New Orleans in 2008, and according to residents they performed as promised. One resident told me after Gustav that she was actually quite thrilled to watch from within her well-elevated and dry home as Gustav’s water rose over her bottom step.

The homes may be an aesthetic affront to those who prefer New Orleans architectural styles of the twentieth century, when the city was told it could be dried, but in important respects — elevation, sturdy construction, and on some a steeply pitched roof — they resemble homes from days when New Orleans flooded regularly. There are new houses less controversial in design than the Brad Pitt homes, the Habitat homes of Musicians’ Village in the Upper Ninth, for example. They too are elevated and sturdy, built for the natural environment of the delta. So let the debate over aesthetics continue. But let the new homes of whatever style be built with the expectation that there will be high winds and lots of water in the city’s future. Let the debates continue over whether to dismantle existing levees and restore wetlands, or build new ones that are bigger and stronger than ever. So long as all understand that big levees or no levees, New Orleans is a wet and often a very windy place. Rebuild a New Orleans for which hurricanes and the frequent presence of great amounts of water are the new “old” normal. And may the people of New Orleans learn to accept and live with that new “old” normal.

Christopher Morris is Associate Professor of History at the University of Texas at Arlington. He is the author of The Big Muddy: An Environmental History of the Mississippi and Its Peoples from Hernando de Soto to Hurricane Katrina and Becoming Southern: The Evolution of a Way of Life, Vicksburg and Warren County, Mississippi, 1770-1860.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to environmental and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Looking southeast down the flooded and aptly named Canal Street in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Photo by joeynick, iStockphoto.

What’s in a literary name?

Names and naming are topics of perennial interest, but until recently there were few general discussions of names as a literary feature. This is strange, since questions about names keep coming up in criticism. How are character names chosen? Are literary names always meaningful, or are some characters named quite casually? Does each genre have a list of first names available only for that sort of writing? Corydon, a stock-name for a shepherd, is obviously pastoral, whilst Hodge is clearly georgic. (Thomas Hardy wrote of the farm labourer ‘personified by the pitiable picture known as Hodge’.) Is it necessary for fictional characters to be named at all? After all, in romances a name can be withheld for much or all of the story. When it does emerge it may not be a full name. (Full names, complete with surname, have a history of their own and deserve a dedicated blog post in their own right.)

Some writers, such as George Bernard Shaw, have been able to get going without deciding on names for their characters, simply drafting dialogue for anonymous characters. Others, though – Charles Dickens and Henry James for example, couldn’t begin without the right names. They used to keep lists of possible names for future use. They collected them from previous literature, newspapers, official lists, or even advertisements on the side of vans, and agonized over which was the most appropriate name for a character. It was as if they had to know the true name before the character came into focus, or into existence; as if only one name was exactly right for the character’s personality and social standing. A casual choice might have been inconsistent. When he came to choose, Dickens rightly rejected Young Innocent (too explicitly allegorical), Copperstone, and Stonebury (implausible). He seems to have looked for associations that weren’t obvious. Steerforth suggests a bold and facile person, but doesn’t spell out boldness explicitly. Hard Times‘ Gradgrind perfectly suits the unimaginative utilitarian, with his daily grind of graduated educational tasks. Even the structure of the word is repetitive. The reader may think of Gradgrind as grinding the faces of the poor.

Some writers, such as George Bernard Shaw, have been able to get going without deciding on names for their characters, simply drafting dialogue for anonymous characters. Others, though – Charles Dickens and Henry James for example, couldn’t begin without the right names. They used to keep lists of possible names for future use. They collected them from previous literature, newspapers, official lists, or even advertisements on the side of vans, and agonized over which was the most appropriate name for a character. It was as if they had to know the true name before the character came into focus, or into existence; as if only one name was exactly right for the character’s personality and social standing. A casual choice might have been inconsistent. When he came to choose, Dickens rightly rejected Young Innocent (too explicitly allegorical), Copperstone, and Stonebury (implausible). He seems to have looked for associations that weren’t obvious. Steerforth suggests a bold and facile person, but doesn’t spell out boldness explicitly. Hard Times‘ Gradgrind perfectly suits the unimaginative utilitarian, with his daily grind of graduated educational tasks. Even the structure of the word is repetitive. The reader may think of Gradgrind as grinding the faces of the poor.

Every name has a history of political and social associations. In Victorian times some thought it wouldn’t do for their servants to have more impressive names than their own. Both in real life and fiction they gave servants new names, from a fairly small pool that changed with the fashion. Servants, like slaves, were made to go by names chosen by their masters and mistresses. Often these imposed names were associated with particular duties. A coachman was quite likely to be called James, a lady’s maid Abigail. In literature, choosing names is of course only one aspect: the development of a name is often more significant.

Some novelists and poets have been specially interested in naming – Spenser, Milton, Dickens, Joyce, and Nabokov, for example. It’s well known that Edmund Spenser conveys much of the meaning of The Faerie Queene through his character names, which have a grammar of their own. Sansfoy, Sansloy, and Sansjoy exhibit related deficiencies – faithless, lawless, joyless. So too the sisters Perissa and Elissa contrast an excess and deficiency of desire. Great writers are brilliant in naming as in everything else. They make naming enter into their plots, as when Milton changes the fallen angels’ names in Paradise Lost as a consequence of their Fall – using Satan only for the fallen character, Lucifer for the unfallen. In Finnegans Wake, the ever-changing names reiterate acrostic patterns that are one of our best guides to Joyce’s universal themes – besides being a source of much of the fun. The universal Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker ranges through history and geography, becoming now Haroun Childeric Eggeberth, now Hung Chung Egglyfella, now Howth Castle and Environs.

Some novelists and poets have been specially interested in naming – Spenser, Milton, Dickens, Joyce, and Nabokov, for example. It’s well known that Edmund Spenser conveys much of the meaning of The Faerie Queene through his character names, which have a grammar of their own. Sansfoy, Sansloy, and Sansjoy exhibit related deficiencies – faithless, lawless, joyless. So too the sisters Perissa and Elissa contrast an excess and deficiency of desire. Great writers are brilliant in naming as in everything else. They make naming enter into their plots, as when Milton changes the fallen angels’ names in Paradise Lost as a consequence of their Fall – using Satan only for the fallen character, Lucifer for the unfallen. In Finnegans Wake, the ever-changing names reiterate acrostic patterns that are one of our best guides to Joyce’s universal themes – besides being a source of much of the fun. The universal Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker ranges through history and geography, becoming now Haroun Childeric Eggeberth, now Hung Chung Egglyfella, now Howth Castle and Environs.

Names are focal points of more literary works than most people recognize. Until the end of the seventeenth century, names were often concealed below the overt, grammatical surface of writing. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, many literary names were hidden away in acrostics, anagrams, and similar devices. If they could be brought back into critical discourse we might have a better hold on literature’s political content. In Spenser’s case, it might lead to restoration of the politics of The Faerie Queene. And in Joyce the dismantling and reassembling of names restores many of his best satiric jokes. Every reader of Dickens has enjoyed some of his grotesque names, like Quilp, or Uncle Pumblechook. But that’s only the beginning of criticism. His familiar names – Oliver Twist and the rest – have often developed further associations as time has gone by. Many associate ‘Oliver Twist’ with asking for more, without perhaps reflecting that ‘twist’ is Cockney slang for ‘appetite’ – and already was so in Dickens’s time. Nabokov tells us what the variants of “Lolita” mean; but what about the many other names – the motels, the places, the school register? In literature, names are often doors to meaning, and words giving glimpses of the writer’s intentions.

Alastair Fowler is Regius Professor Emeritus of Rhetoric and English Literature at the University of Edinburgh and was previously Professor of English at the University of Virginia. For many years he divided his time between the United States and Britain, where he now lives. His publications include Literary Names: Personal Names in English Literature, an annotated edition of Paradise Lost (1968), Kinds of Literature (1982), Renaissance Realism (2003), and How to Write (2006). His interest in literary names goes back to his Witter Byner lecture at Harvard in 1974.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credits: Charles Dickens woodcut, via ZU_09, iStockphoto.

Finnegans Wake, Oxford World Classics jacket cover

September 22, 2012

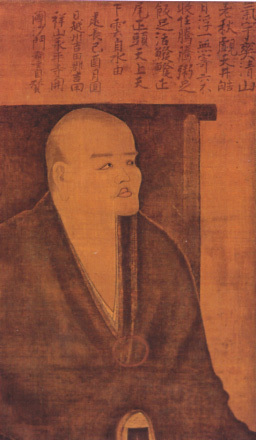

Remembering Dogen’s death

As the founder of Soto Zen, one of the major Buddhist sects in Japan, the birth and death anniversaries of Dogen Zenji (1200-1253) are celebrated every fifty years. It was amply demonstrated at the beginning of the millennium through the outpouring of new publications and media productions, including a kabuki play and TV show as well as manga versions of his biography, that these events help to disseminate the master’s teachings to a worldwide audience yet also turn him into a commercial commodity that is somewhat misrepresented.

Of the two celebrations, according to an article by William Bodiford in Dogen: Textual and Historical Studies, it is the death memorial of patriarchs and saints that has traditionally gained greater attention in Japanese culture. This is in part because of the way all forms of Buddhism are closely associated with the performance of funerals and bereavement ceremonies for the dead. In pre-modern times, the anniversary of Dogen’s demise was marked on the twenty-second day of the ninth lunar month according to the ancient Chinese calendar. Now this date, like so many other annual occasions from New Year to the Buddha’s birthday, is regularized to the Western solar calendar.

Of the two celebrations, according to an article by William Bodiford in Dogen: Textual and Historical Studies, it is the death memorial of patriarchs and saints that has traditionally gained greater attention in Japanese culture. This is in part because of the way all forms of Buddhism are closely associated with the performance of funerals and bereavement ceremonies for the dead. In pre-modern times, the anniversary of Dogen’s demise was marked on the twenty-second day of the ninth lunar month according to the ancient Chinese calendar. Now this date, like so many other annual occasions from New Year to the Buddha’s birthday, is regularized to the Western solar calendar.

For most of his career, Dogen was among the most vigorous and productive of Buddhist teachers. Born to an aristocratic family but tragically forced to grieve the loss of his parents while still a young child, the orphan took the tonsure at age 13 and studied at various temples of both the Tendai and Zen schools, which had just recently gained a footing on Japanese soil. At 23, Dogen left Japan and spent four years traveling in China, where he gained enlightenment under the tutelage of Rujing, a master of the Caodong school.

On returning to his native country, he established his first temple in the outskirts of the capital in Kyoto and then at age 43, he led a small band of followers to the remote mountains of Echizen province. Although the reasons for this move are obscure, it is likely that Dogen made what was at the time an arduous trek by foot lasting about a week in the mountains north of the capital in order to escape persecution by religio-political rivals. Eiheiji temple was built in Echizen with the financial support of Dogen’s samurai patron, and a new and growing movement was born that eventually became the largest of the medieval Buddhist sects.

During the period lasting about twenty years where he managed temples first in the capital and then in the countryside, Dogen was a prolific writer who produced several major texts largely based on collections of sermons that were delivered in both classical Chinese and vernacular Japanese. A few years after he returned to Eiheiji in the spring of 1248 (from a six-month visit to the temporary capital in the town of Kamakura, where he turned down the abbacy of a new temple that was offered by the shogun), Dogen became ill.

Following this unfortunate development in the winter of 1252, his productivity slowed considerably, and he attended primarily to the matter of choosing a successor to lead the temple. In August of 1253, Dogen was convinced by his disciples to visit Kyoto to seek medical assistance. This proved to be his final journey before he died in the seated-meditation (zazen) posture, and his remains were later taken back to Eiheiji, where they are still venerated in rites of worship today.

It is said that Dogen composed two Japanese waka (31-syllable poems) during the trip to Kyoto, which I have translated in The Zen Poetry of Dogen: Verses from the Mountain of Eternal Peace. Both poems demonstrate his agility with language in expressing a sense of equanimity and calm in the face of a deep sense of frailty and vulnerability due to the vicissitudes of ephemeral human existence. The poems, which evoke feelings of nostalgia and remorse for having left the capital while Dogen steadies himself for inevitable fate, are rare examples of personal emotions suggested by the otherwise stoic Zen master, who is mainly known for his puritanical adherence to monastic rules and ethical regulations.

According to a verse from the time he began the trip titled “On the harvest moon in the year of Dogen’s death”:

Mata minto Just when my longing to see

Omoisho toki no The moon over Kyoto

Aki dani mo One last time grows deepest,

Koyoi no tsuki ni The moon I behold this autumn night

Nerare yawa suru Leaves me sleepless for its beauty.

In this poem Dogen expresses a desire to see his hometown while realizing that this will be the last time. The second waka, written just prior to his death, on “The [final] journey to Kyoto,” reads:

Kusa no ha ni Like a blade of grass,

Kadodeseru mi no My frail body

Kinobe yama Treading the path to Kyoto,

Kumo ni oka aru Seeming to wander

Kokochi koso sure Amid the cloudy mist on Kinobe pass.

The verse uses alliteration in the first syllable of each line as well as natural imagery evoking a difficulty mountain pass that has to be crossed in order to evoke a powerful awareness of the unavoidability of evanescence. The verses reveal the literary genius of Dogen’s approach to appropriating the standpoint of Zen meditation in his personal life.

Steven Heine is an authority on Japanese religion and society, especially the history of Zen Buddhism and the life and works of Dogen. He is the editor of Dogen: Textual and Historical Studies. He has published two dozen books, including Did Dogen Go to China? (2006); Zen Skin, Zen Marrow (2010); and Zen Masters (2010). Read his previous blog post “Four myths about Zen Buddhism’s ‘Mu Koan.’”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Dōgen watching the moon. Hōkyōji monastery, Fukui prefecture, circa 1250. Fukui Prefectural Archives. Image via Shii, Wikimedia Commons.

Oktoberfest

Today the tents will open at the most famous beer festival in the world: Oktoberfest. That’s right, it starts in September. For those of us who can’t make it to a Munich beer tent between now and the end of the festival on October 6th, here’s the Oktoberfest entry by Conrad Seidl in The Oxford Companion to Beer, edited by Garrett Oliver.

Oktoberfest, locally just called “Wiesn” (meaning “the meadow”), is Germany’s largest folk festival, staged for 16 to 18 days on the 31-ha (77-acre) Theresienwiese in Munich from the last 2 weeks of September into the first weekend of October. Since the first Oktoberfest in 1810, it has grown into the most famous beer festival in the world, hosting about 6 million visitors every year (with a record of 7.1 million in 1985). The Munich Oktoberfest has spawned similar festivals from Cincinnati, Ohio, to Blumenau, Brazil. The original festival’s popularity is inextricably tied to its large beer tents, many with up to 10,000 seats. Each tent has its own unique décor and character. Schottenhamel (serving Spaten beer) seats 6,000 people inside and 4,000 in the adjoining outdoor beer garden, Hacker-Festhalle seats 6,950 in the beer hall but only 2,400 in the garden, and Hofbräu seats 6,898 inside and 3,022 in the garden. The smaller tents are the relatively cozy Hippodrom (3,200 inside, 1,000 outside) and the posh Käferzelt that seats 1,000 people, usually Munich’s high society. Beer is served in the iconic 1-l glasses (the so-called masskrug) only — in an average 16-day season beer sales amount to 6.5 million servings. The image of a woman wearing the traditional Bavarian dirndl and cheerfully carrying several giant “Mass” glasses in each hand is an image recognized almost anywhere.

Interior view of Löwenbräufestzelt. Photo by Andreas Steinhoff, 2005. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

There are strict regulations regarding the beer served at the Oktoberfest. Only the large breweries that brew inside Munich’s city limits are allowed to deliver beer to the Oktoberfest — these are Augustinerbräu München, Hacker–Pschorr, Hofbräu, Löwenbräu, Paulaner, and Spaten-Franziskaner-Bräu. The smaller breweries (including Forschungsbrauerei and brewpubs like Union Bräu) as well as those from outside town are banned. The ban on out-of-town beer once raised royal ire; Prince Luitpold of Bavaria, until recently the owner of the “Kaltenberg-brewery” south of Munich, made several attempts to bring his own beer to Oktoberfest. Although he was Prince of Bavaria, the rules held fast and his complaints were in vain, but they did make for some excellent public relations for Kaltenberg’s König Ludwig beer brand.

There is a popular myth that there is one distinctive style of beer brewed for Oktoberfest — but historical evidence shows that there have been many changes in the beers served at the festival in the past. In the first 60 or so years the then popular Bavarian dunkel seems to have dominated the festival. As is often the case, the historical record makes note of the common beer only when something notably different is introduced. This was obviously the case in the year 1872, but the following story was only reported in a pamphlet 35 years later (and quoted in many Oktoberfest publications ever since). In that particularly hot late summer Michael Schott enhamel, owner of Spaten’s tent on the Wiesn, had run out of the traditional dark lager beer — and considered dispensing beer from a different brewery. Joseph Sedlmayr, owner of Spaten-Leistbräu, desperately fearing to lose the contract suggested he sell a strong version of a Vienna-style lager brewed by his son Gabriel. T is beer was in fact an 18°P bock beer and at a probable 8% alcohol by volume (ABV) it was sold at a premium price. It may not have been “traditional” but it proved to be popular and for several years — up until World War I — bock-strength beers dominated the Wiesn. The strength of the beer has changed several times since (being at its lowest point in 1946 and 1947 at two “unofficial” and reputedly illegal Oktoberfest beer bars aft er World War II) and is now in a range between 5.8% and 6.3% ABV. For decades the reddish–brown marzenbier ruled the tents, but in recent years the style has changed yet again. Since 1990 all Oktoberfest beers brewed in Munich have been of a golden color and a slightly sweetish malty nose, with medium body and a low to moderate bitterness. According to European Union regulations, no beers except those brewed by the authorized large breweries of Munich are allowed to be labeled “Oktoberfest,” yet many American breweries brew their own versions of Oktoberfest beers. Boston Beer Company (Samuel Adams) claims to be the largest brewer of Oktoberfest beer because no single brewery in Munich brews more of the festival beer than their American competitor.

Coachman of a brewery carriage in traditional costume next to a decorated horse. Photo by Hb3. Creative Commons License. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Oktoberfest is not just a beer festival and showcase for Munich’s breweries; it is also a sort of pop-up amusement park. The popular funfair features some spectacular fairground attractions, from roller coasters to a real flea circus with live fleas performing amazing tricks that can only be seen only through a magnifying glass. The Oktoberfest is also a part of living Bavarian history. It originated in the year 1810 when Bavaria’s king Maximilian I. Joseph organized a 2-day festival (on October 13 and 14) to celebrate the wedding of his son, Crown Prince Ludwig (later Ludwig I) and Princess Therese of Sachsen-Hildburghausen. On this occasion free beer and free food were offered at four different locations in Munich and a horse race was organized in what was to become Theresienwiese (named after the princess). At the raceground innkeepers from downtown Munich had set up tents where food and beer were sold. The entire spectacle was popular enough to make a tradition out of the festival, a tradition kept alive for 200 years and only discontinued in times of war and cholera. It is often forgotten that the first Oktoberfest was a political manifestation to demonstrate national unity during and after the Napoleonic wars (when Bavaria was fighting on the side of the French). This politicized character has been revived several times — during German unification in the 1870s, under the Nazi regime in the 1930s, and after German reunification in the 1990s. And for practical (i.e., weather) reasons, the festival was moved forward in the calendar from early to mid-October in the first decades to the last 2 weeks of September in the 1870s, with only a couple of days reaching into the actual month of October. On noon of the first day of Oktoberfest, the mayor of Munich taps the first keg and proclaims “O’zapft is!” (“It is tapped!”) and the world’s largest beer party comes to life.

Bibliography

Bauer, Richard, and Fritz Fenzl. 175 Jahre Oktoberfest. Munich, Germany: Bruckmann, 1985.

Conrad Weidl is a journalist and author with extensive expertise on beer. You can follow him on Twitter at @Bierpapst.

The Oxford Companion to Beer is the first major reference work to investigate the history and vast scope of beer, featuring more than 1,100 A-Z entries written by 166 of the world’s most prominent beer experts. It is first place winner of the 2012 Gourmand Award for Best in the World in the Beer category, winner of the 2011 André Simon Book Award in the Drinks Category, and shortlisted in Food and Travel for Book of the Year in the Drinks Category.

Garrett Oliver, editor of The Oxford Companion to Beer, is the Brewmaster of the Brooklyn Brewery and author of The Brewmaster’s Table: Discovering the Pleasures of Real Beer with Real Food. He has won many awards for his beers, is a frequent judge for international beer competitions, and has made numerous radio and television appearances as a spokesperson for craft brewing.

Read previous Oxford Companion to Beer blog posts and watch videos: “A pint of Guinness” ; “Nothing says ‘holidays’ like beer & cheese” ; “Another lesson from Garrett Oliver: rice in beer” ; “Hosting a holiday party with special guest Christmas ale” ; “We also give thanks for beer” ; “Everything you ever wanted to know about Prohibition” ; and “The Great American Beer Festival”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

September 21, 2012

5 things we should know about the Libyan and Egyptian demonstrations

1. We must start first by condemning the violence and killing of diplomats and civilian people. Whatever we may feel, however we may be hurt by the video, it cannot justify in any way the killing of people. Such actions are simply anti-Islamic and against Muslim values. The demonstrations were in fact first organised by a tiny group of Salafi literalists who were attempting to direct popular emotions against the United States and the West in order to gain for themselves a central religious and political role. We should not confuse this tiny minority who are using a populist religious discourse, with the millions of Arabs, and mainly Muslims, who took to the streets during the Arab uprisings in a non-violent way to call for freedom, justice and dignity.

2. We should try now, after the Arab uprisings, to get a better understanding of the dynamics within Muslim-majority countries. Here we are witnessing a power struggle between Salafi literalist movements and other Islamist groups (such as the Nadha in Tunisia, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and even the Sufi trends). The Salafis are attempting to destabilise the democratisation process and make themselves seen to be the true real religious authority within their society. They are utilizing these emotional popular reactions towards the recent video and nurturing the numerous frustrations of the people to fuel an anti-American sentiment and rejection — indeed they have succeeded in gathering a minority of people who then acted out of control.

We need to add to this internal tension one of the most important challenges for the future of the Middle East and that is the fracture between the Sunni and the Shi’a. We cannot understand the rationale behind the demonstrations by only considering the popular reaction to the video. There are internal political and religious challenges that we must consider and understand.

3. Whilst nothing can justify the popular violence, we must try to understand why the people are reacting so intensely. One can see that American and European Muslims, through the successive controversies in Denmark, The Netherlands, France and now the United States, are not reacting violently. Instead they take a peaceful, critical stance in spite of feeling hurt by the cartoons or the video. However that in the Southern Muslim-majority countries, the majority of people face poverty, unemployment, corruption and sometimes lack of social and political hope. From day-to-day they rely very much on their belief, the meaning of their life and the sacred in order to survive, so when they see the ‘rich and comfortable’ people of the West mocking and ridiculing what they consider to be sacred, they are doubly offended. We should not dismiss or underestimate these socio-economic factors. The whole controversy relates to many causes, rather than singularly, religion.

4. We heard the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) calling for new laws on blasphemy. I wouldn’t suggest such a way, for I don’t think that this will solve the problem. We don’t need more laws, rather each and every one of us needs more education and more understanding about the way in which we deal with our rights, our responsibilities and our living together. Pluralism is not only about legal regulations; it is about knowledge, education, ethics and respect. This is the common challenge for all our educational systems. We still may continue to be obsessed with our rights, neglecting in fact that our world asks for each of us to become more responsible.

5. If we look at what is happening with the West today and the Muslim-majority countries, the great majority of citizens are caught between two populisms. We can see now that in the United States as well as in Europe we have the tea party, the neo-conservatives, and the new evangelists that are now creating a new enemy of Islam and the Muslims — portraying them as “a cancer”, aliens and foreign citizens, outsiders within, who are threatening the very essence of Western culture. All the rhetoric is based upon fear, racism, bigotry and very often Islamophobia. On the other side we have minority Muslim groups who are indulging in a similar religious populism, advocating the fact that “we are more Muslim when we are non-Western” or clearly against the West. There is no other way but to enter into a kind of ‘clash’. The media are covering these highly visible and vocal stances and so we get a vicious circle, where each side makes the headlines, nurturing upon each other, and ending up as objective allies in this ‘clash’ of civilisations.

It is therefore critical today for the citizens caught in between these two populisms to become more vocal themselves, to create a kind of new ‘we’ in the name of the same values they advocate: proactive coexistence, mutual respect, and knowledge of one another. The common challenges are education, poverty, social justice, and understanding. The people should not be misled nor fool themselves into recognising those who are truly in the wrong. This is the very message of the Arab Muslims. Millions of people in the South are showing that they cherish the same values as Western citizens. Let us celebrate this in a reasonable way and not be driven by blind emotions.

Tariq Ramadan is Professor of Islamic Studies at Oxford University, and is President of the European Muslim Network in Brussels. His books include Islam and the Arab Awakening; What I Believe; Radical Reform: Islamic Ethics and Liberation; In the Footsteps of the Prophet: Lessons from the Life of Muhammad; Western Muslims and the Future of Islam; and Islam, the West, and the Challenges of Modernity.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers