Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1017

October 3, 2012

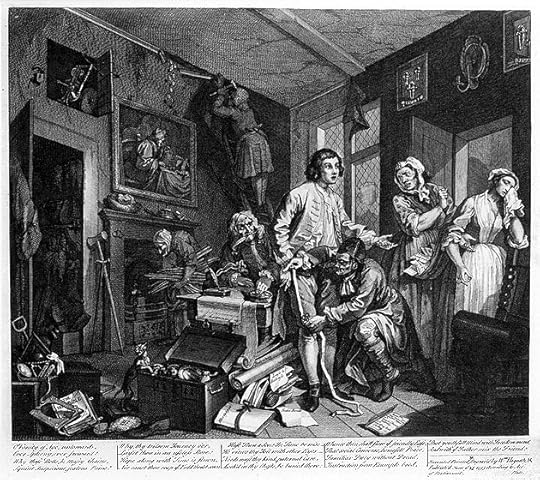

On taste and morality: from William Hogarth to Grayson Perry

The artist Grayson Perry recently completed a cycle of six giant tapestries, The Vanity of Small Differences, inspired by William Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress. In the Turner Prizewinner’s modern rendition, Tim Rakewell (like his Georgian counterpart Tom Rakewell) undergoes a social transformation from humble origins to landed gentry. In Perry’s version, Tim’s life course is transformed by university education and a self-made fortune in computers – which catapults him socially from his humble origins in a Northern council house, via the bourgeois confines of middle-class dinner tables, to owning his own country estate. Like his eighteenth-century namesake, Tim meets an untimely death — not from syphilis, but through another, more contemporary hazard resulting from a ‘fast’ lifestyle — a crash in his Ferrari. Like Hogarth, Perry ingeniously constructs a modern morality tale that captures the spirit of the age — in Hogarth’s day, advantageous marriage; in our own time, fascination with wealth and celebrity culture. One of the most compelling aspects of both artists’ work is their eye for the design of everyday objects and what they convey about their owners’ lifestyles and identities. From geegaws to grand purchases, fabrics to foodstuffs, the choices we make locate us in modern consumer culture as part of a particular tribe, group or class. Their condition, use and juxtaposition are invested with human drama and emotion. In Hogarth, a wrecked marriage is indicated by an upturned mahogany chair; in Perry, violent death is present in a smashed iPhone.

Through a riveting series of television programmes for Channel 4 about the making of his tapestries, Perry excelled in casting a non-judgmental, even quasi-anthropological eye over the habits of each ‘tribe’ he visited in search of inspiration — from grannies’ front parlours (with their china cabinets and horse brasses) and working men’s clubs in Sunderland, to the game larders of the Cotswold gentry. Among the middle classes he contrasted those he met who were affluent but who had no particular views about taste of their own — who effectively outsourced their consumer decisions to the builders of executive-style homes with luxurious magnolia interiors (ready furnished) — and those for whom ‘cultural capital’ was important. Among a certain section of bourgeois consumers, each Farmers’ Market purchase and shabby-chic item artfully placed at home becomes a marker not only of taste, but of sound morals (supporting local producers, buying Fairtrade products, demonstrating ‘good taste’). Not so those who inherit wealth in modern Britain — whose loyalty to their tribe is demonstrated by appropriate dress — consisting where possible of hand-me-downs from their great-grandparents, and favouring durability over the whims of shifting fashions. Perry depicts the latter group as a wounded stag with a human face, under threat of extinction from the harsh realities of economic change and onslaught of new money (Tim Rakewell at the gate with his chequebook).

It is a certain type of middle class person who emerges from Perry’s study as the most anxious about taste, probably because of its close association with morality among this particular tribe. ‘Bad’ taste isn’t just about choosing the wrong wallpaper if you believe that it is an expression of your cultural capital and social aspiration: it’s about whether you are a good person and the ‘right kind’ of person. In this, the twenty-first century bourgeois (southern?) English are the direct inheritors of their Georgian ancestors’ view of taste. For it was only with the rise of modern consumer society that such things came to be of consequence to people beyond the ranks of the gentry and aristocracy, who in previous generations had pretty much preserved their monopoly on consumer choices owing to their stranglehold on wealth and power. Personal preferences came to matter only when markets diversified (more stuff available), specialised (more ingenious stuff available), and produced goods that became more affordable (more cheap stuff). Added to this was better transportation by road, sea and canal — later railways (easier-to-get stuff). Novelty became a major factor in the desirability of consumer goods (exotic stuff).

Through this new world of exciting goods, ordinary people with a little more disposable income to spend (which varied according to other factors, like the price of basic foods), sought guidance on how to acquire and exercise the faculty of taste. Access to books, art, and music was no longer confined to the very wealthy. Certain rules made it easier, provided consumers boned up on where to look and what to buy from an authoritative source, like the vastly popular Spectator, published in the early years of the eighteenth century by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. As far as music went, for much of the century, Georgian consumers mostly thought that Italian music was good taste, though connoisseurs debated about which composers expressed the finest sentiments. If all else failed, and Italian opera in its earliest imported forms proved a little too florid, Handel reassured the English with royally-approved reworkings, adapted to suit the more austere taste of the Hanoverians.

Unlike Grayson Perry’s findings about contemporary Britain, where the taste of the gentry is defined by inheritance and continuity, the Georgian gentry were much more innovative and experimental, inspired often by their experiences on the Grand Tour. The great era of country house building between 1680 and 1730 brought to the British Isles new architectural styles that are still traceable in the neo-Classical porticos and faux PVC sash windows that adorn modern executive homes. Perry’s insights resist the idea that there is any such thing as bad taste — merely that taste is tribal and profoundly linked to where we come from and whither we aspire. Taste and morals aren’t necessarily linked – but perhaps, in an age of growing awareness about the finitude of global resources, the process of highlighting the political dimensions of consumption isn’t necessarily a bourgeois failing either.

Helen Berry is Reader in Early Modern History at Newcastle University. She is the author of numerous articles on the history of eighteenth-century Britain, and is the author of The Castrato and His Wife (2011), which is now available in paperback(2012). If you liked this, try Helen Berry’s OUPblog articles on why history says gay people can’t marry and an analysis of Royal weddings.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: A Rake’s Progress by William Hogarth, in public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

October 2, 2012

Obama is surging

The Obama campaign, by fortune or by wit, has peaked at the right moment. Early voting has already started in Virginia, and starts in Iowa and Ohio next week. This means that the polls telling a uniform story of an Obama surge in crucial swing states aren’t just snap-shots; they are predictive of how voters — about 35 percent of total voters — are actually starting to vote as we speak.

Republicans like Karl Rove are saying that the CBS/NYT/Quinnipiac polls are wrong because they are using the turnout model of 2008. But Gallup found similar results. So did Bloomberg. So did the Washington Post. Obama’s numbers are moving up, and it is intellectually dishonest and ultimately self-defeating for some Republicans to spin a story about over-sampling Democrats to deny the plausible reality that a triangulation of polls are pointing to. (And by the way, the over-sampling spin is rather more complicated even than what its wonkish advocates say on TV, if only because no one knows what turnout is going to be.)

So right now, it is not looking good for Romney, who has to wait until October 5th to stand toe-to-toe with Obama, and demonstrate his presidential stature. It may be too late by then, which is why the Romney campaign has finally shifted from a national strategy to a state-by-state strategy, starting in Ohio. Whether or not it was wise to wait this late to start the ground game, we will know in six weeks. The Obama campaign has 96 offices in Ohio, nearly three times as many as Romney does — a strategic bet by the Democrats that the ground game matters more than the battle over the airwaves. The Republicans are expecting, in the post-Citizens United world, that the superPACS will step up to seal the deal for Romney.

Every fumbling campaign has at least one correctable problem — the candidate. Romney and Ryan need to stop complaining about how bad it is, or at least spend as much time telling us how good we could have it in the next four years. Even independent voters don’t want to hire a doomsayer for president, and this is especially important because the alternative, Obama, is a positive, likable guy. Even if Americans don’t feel better off today than they were in 2008, the real question is whether they would be better off in 2016 under Obama or under Romney. It is not just about malaise in America, but also about morning in America. What can Americans look forward to with President Romney? For better or for worse, voters need to be flattered, and they don’t want to to be told that the only reason not to vote for a sitting president is the disaster he will bring. They also need to be inspired by someone who would awaken their better angels and lead them to greener pasture.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: President Obama Attends Town Hall Meeting In Indiana (2009). Photo by EdStock, iStockphoto.

Anatol Lieven on American nationalism

On the one hand, there is the core tradition of American civic nationalism based on the universalist ‘American Creed’ of almost religious reverence for American democratic institutions and the US constitution. On the other, there exists a chauvinist nationalism which holds that these institutions are underpinned by cultural values which belong only to certain Americans, and which is strongly hostile both to foreigners and to minorities in America which are felt not to share those values. Deprived by nationalist ideology of the ability to explain what is happening in rational terms, some people are now turning to ideologies and demonologies that contribute greatly to the paralysis of effective government in what remains the world’s most powerful and important country.

Anatol Lieven, author of America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism, examines the history of nationalism, America’s unique brand of nationalism with its varying positive and pejorative labelling, and the growing gulf between American citizens.

Nationalism and contemporary America

Click here to view the embedded video.

The American Right, religion, and the Constitution

Click here to view the embedded video.

Anatol Lieven is a Senior Research Fellow at the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C. His books include America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism; Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian Power; and The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Path to Independence, which was a New York Times Notable Book for 1993.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to American history on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Beethoven on stage in 33 Variations

A blend of past and present, art and life: Beethoven’s most challenging work for piano, the Diabelli Variations op. 120, has triggered a mania of interest on the theatrical scene. Several years ago New York playwright Moisés Kaufman visited my wife Katherine Syer and myself — the first of several visits — to shape a play on Beethoven. The resulting play, 33 Variations, focuses on Beethoven’s spectacular obsession with Anton Diabelli’s humble but sturdy waltz, and in turn our own scholarly obsession with the composition. Following a final workshop of the play at the University of Illinois and its premiere at the Arena Stage in Washington, DC, it reached Broadway with Jane Fonda assuming the central role of the musicologist Katherine Brandt, who seeks to unravel the mystery of Beethoven’s obsession by studying the composer’s sketchbooks at the Beethoven Archive at Bonn. From major stages in Los Angeles to Chicago, Berlin to Tokyo, 33 Variations is now being performed at many regional and community theaters around the country.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The intertwining of art and life goes further. Fascinated by his own visit to Bonn to examine Beethoven’s manuscripts, Kaufman set the second act of the play in the Beethoven Archive itself. (The New York production won a Tony Award for the stage set depicting the archive.) Just as the play opened, a big fundraising effort enabled the Beethoven-Haus at Bonn to acquire the autograph score of the Diabelli Variations from private hands, enabling the intriguing manuscript to join the sketchbooks already in that collection. The manuscript treasure can be viewed online through the digital archives of the Beethoven-Haus.

Playwright Moisés Kaufman, left, consulted with musicologists Katherine Syer and William Kinderman on his new play, 33 Variations. Ultimately, Kaufman developed a composite character based on the husband-and-wife consultants. Photo by L. Brian Stauffer

One level of action in 33 Variations takes place in Vienna around 1820; the other occurs in New York and Bonn in the present day. Both Beethoven and the scholar Katherine are engaged in a quest for meaning and a race against time, struggling against grave illness. In the play, Katherine doesn’t survive the action; her final scholarly paper is read by her daughter Clara. What has Katherine learnt? That a valuable, seemingly unlimited source of inspiration lies in the commonplace, accessible to us all. Diabelli’s rough “cobbler’s patch” of a theme is not to be despised. Guided by this insight, Katherine’s judgmental regard of Clara yields to a more generous, profound humanity, as she sees her daughter with new eyes, no longer treating her condescendingly like a second-rate waltz.The cast of 33 Variations requires seven actors as well as a pianist who plays many of the variations. In its sequence of scenes, the play mirrors the variation form of Beethoven’s great work with a fugue of interwoven themes and a graceful minuet finale. Kaufman’s fictional construction is sustained by Beethoven’s creative vision. In one memorable scene, Katherine is amazed to observe from Beethoven’s sketches how the composer created Variation 3 step-by step, refining a basic idea through richer successive versions. The pianist brings this creative unfolding to sound for the audience.

In my research I discovered that Beethoven conceived two-thirds of the variations in 1819 and then, unable to finish the piece, put the work aside for several years. The manuscripts reveal how he finished it, by incorporating ironic allusions to the original waltz and then radically transforming it in later variations. Beethoven absorbs into his work an encyclopedic range of contexts including references to Bach, Handel, and Mozart before capping his cycle through a fascinating self-reference to the last movement of his own last sonata.

It is rare for a play to engage so directly with musical meaning and the creative process, and gratifying how a book and recording helped generate an unanticipated harvest like 33 Variations. How one thing leads to another — sometimes quite unexpectedly — is Beethoven’s secret. Anton Diabelli requested just a single variation from Beethoven, seeking to have the famous composer’s name associated with a networking project for his fledgling publishing firm. Instead of that single variation, Beethoven instead offered after years of toil a microcosm of his art, a colossal achievement brimming with wit and brilliance but also compassionate understanding. Now, almost two centuries later, his astonishing brainstorm exerts a stronger spell than ever before. The play that started in our living room in Illinois testifies to that effect. Artworks like Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations draw people together, raise awareness, enable new friendships, and open new perspectives.

William Kinderman is Professor of Musicology at the University of Illinois and a noted pianist, whose recordings of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations and last sonatas are available through Arietta Records. Kinderman’s books with Oxford University Press include Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, Mozart’s Piano Music (2006), the comprehensive study Beethoven (expanded ed. 2009), and Wagner’s ‘Parsifal’ (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

October 1, 2012

The Giving Pledge and private foundations

By Edward Zelinsky

The Giving Pledge, founded by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, has announced that eleven more affluent families have taken the Pledge and have thereby committed to donating at least half of their wealth to charity. Among these new Pledgers is Gordon Moore, a legendary founder of Intel and the father of Moore’s Law which postulates that the number of transistors on integrated circuits doubles roughly every two years.

I am a Buffett fan and a fan of the Giving Pledge in particular. It is commendable that so many wealthy families have embraced the ethic of philanthropy. Forbes magazine recently commended this effort, and rightly so.

While the Giving Pledge deserves praise, it does raise important issues which deserve discussion. One such issue is the estate tax revenue lost when wealth is donated to charity. This is a significant problem at a time of enormous budget deficits. It is ironic that both Mr. Buffett and Mr. Gates are outspoken supporters of the estate tax, but have arranged their affairs to avoid the tax by contributing to charity.

While the Giving Pledge deserves praise, it does raise important issues which deserve discussion. One such issue is the estate tax revenue lost when wealth is donated to charity. This is a significant problem at a time of enormous budget deficits. It is ironic that both Mr. Buffett and Mr. Gates are outspoken supporters of the estate tax, but have arranged their affairs to avoid the tax by contributing to charity.

One possibility is for the families taking the Pledge to donate voluntarily to the federal Treasury a portion of their wealth equal to the estate taxes they will avoid by donating to charity.

A second and equally important issue has recently been illuminated by the Wall Street Journal. The Pledgers agree to give at least half of their assets to charity. They don’t agree to the form such charity will take. Some Pledgers may give their wealth to private foundations. And private foundations are, well, private. Given the problematic nature of some private foundations, it is particularly compelling for private foundation Pledgers to donate to the federal Treasury as well.

My wife and I started a private foundation in memory of our oldest son. The Barak Zelinsky Foundation, Inc., will never be a charitable behemoth like the Gates Foundation. However, the Foundation perpetuates our son’s name in the interests of what Judaism calls tzedekah. Barak’s foundation is truly a family enterprise: His now-adult siblings are directors of the foundation and help recommend worthy charities to receive contributions in their brother’s name. No one takes a salary or any compensation, directly or indirectly, from our family foundation or its income.

There is, however, a darker side to private foundations. In 1969, the abuse of private foundations led Congress to add to the Internal Revenue Code as series of taxes to regulate such foundations. These regulatory taxes, among other things, deter self-dealing transactions between private foundations and insiders positioned to benefit inappropriately from foundation assets. These regulatory taxes also deter private foundations from investing in undiversified fashion or in ways which jeopardize such foundations’ charitable purposes.

Even when private foundations do not undertake the kind of actions at which these regulatory taxes are aimed, it remains unclear whether the tax law should (as it does today) subsidize through favorable tax treatment enterprises with relatively little public accountability, indeed, enterprises typically controlled by the members of a single family. Advocates of private foundations celebrate their entrepreneurialism and independence. Skeptics suggest that private foundations reflect extensive tax subsidies for rich persons’ personal agendas and dynastic ambitions.

The tax subsidy of our modest private foundation is, by definition, modest. However, to paraphrase Everett Dirksen, when billions of dollars go into larger private foundations, we are talking about real money — and a real subsidy from federal taxpayers.

In light of these concerns, let me suggest a variation of my earlier proposal that the Pledgers contribute an amount to the federal Treasury equal to the estate taxes they avoid by their charitable gifts. In particular, the Pledge could distinguish between the Pledgers who donate their fortunes to publicly-controlled institutions, such as colleges, communal hospitals and museums governed by diverse boards of directors, and the Pledgers who contribute their wealth to private foundations.

Even those who believe that the Pledgers giving their wealth to public charities shouldn’t contribute to the federal fisc may conclude differently about private foundation Pledgers. Through contributions to the federal Treasury equal to the estate taxes they would otherwise owe, such Pledgers would acknowledge that, by donating to private foundations typically controlled by their families, their charity has taken a different and less publicly accountable form.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Warren Buffett attends the premiere of ‘Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps’ at the Ziegfeld Theatre on September 20, 2010 in New York City. Photo by EdStock, iStockphoto.

Violating evolved caregiving practices

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently endorsed two controversial childrearing practices: sleep training and circumcision for infants.

Both practices violate ancestral caregiving practices which we know are linked to positive child outcomes.

Over 30 million years ago the social mammals emerged, characterized by extensive on-demand breastfeeding, constant touch, responsiveness to the needs of the offspring, and lots of free play. Humans are one branch of social mammals.

Over the course of evolution, humans became the neediest newborns at full term birth, with 75% of the brain yet to grow and over 20 years of growth before adulthood. Why such a long period of growth? When humans became upright and bipedal, women’s pelvises shrank in size to make walking possible. To accommodate the shift, babies had to be born at an early stage of growth (Trevathan, 2011). In fact, according to comparisons with other animals, humans are born 9-18 months early! That means an “external womb” is needed for the rapid brain growth that occurs in the first years of life. Hence, the need for the intensive parenting that co-evolved with the neediness of infants.

The characteristics of intensive parenting among humans include:

2-5 years of on-demand breastfeeding (vital for immune system and brain transmitter systems)

Nearly constant touch (vital for building an adaptive stress response system)

Responsiveness so that the baby does not get distressed (critical for vagus nerve development, which influences all systems in the body)

Multiple adult caregivers (facilitates responsiveness in the mother)

Free play (develops all sorts of capacities including social and intellectual)

Natural childbirth — i.e., no interference with timing, no induced pain (trauma at birth leads to hypervigilance and stress reactivity)

These practices are universal among hunter-gatherer societies who sustain good health and, after age 15, live as long as we do (Fry, 2006; Hewlett & Lamb, 2005; Lee & Daly, 1999).

All these caregiving practices are known to influence development and health over the long term. The influence of caregiving occurs through the processes of epigenetics and developmental plasticity. Caregiving turns genes on and off, shapes stress response, establishing thresholds and ratios of cells in every system in the body and affecting the trajectory of growth (Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009; Meaney, 2010).

When these caregiving practices are missing or of poor quality, it impairs outcomes for the child, influencing the development of body/brain over the long term. The infant’s experience is a historical record written in his or her body/brain, which sometimes becomes apparent only later in mental and physical health outcomes (Schore, 2003a, 2003b). For example, stress reactivity eats away at mental and physical systems and makes social relations difficult.

All animals have a developmental niche for offspring. The niche for human infants is the aforementioned caregiving practices. In effect, human caregiving practices and baby needs represent an evolved developmental system (Oyama, Griffiths, & Gray, 2001). The evolved system leads to species-typical outcomes (Lickliter & Harshaw, 2010). Species-typical outcomes are seen in hunter-gatherer communities that still follow these practices where individuals have pleasant personalities, and social and intellectual acumen (Lee & Daly, 1999). However, when these practices are violated, the evolved developmental system breaks down and leads to species-atypical outcomes.

In light of evolved systems, we should not be surprised when violations of intensive parenting practices lead to poor outcomes for children on all fronts — mental, physical, social, and intellectual. Indeed, that seems to be the case as child wellbeing has been deteriorating for some decades in the USA (e.g., Heckman, 2008; UNICEF, 2007). Our aims for childbirth, childrearing and child wellbeing are too low.

Darcia Narvaez is co-editor of Evolution, Early Experience and Human Development:

From Research to Practice and Policy with Jaak Panksepp, Allan N. Schore and Tracy R. Gleason. She is an Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Notre Dame. Her research focuses on moral development through the lifespan with a particular emphasis on early life effects on the neurobiology underpinning moral functioning (triune ethics theory). Dr. Narvaez has co-authored or co-edited seven books and is editor of the Journal of Moral Education.

Evolution, Early Experience and Human Development: From Research to Practice and Policy discusses the caregiving practices mentioned above in light of their effects on child outcomes. It has chapters by the experts in each area and each scholar provides detail on how a caregiving practice influences child outcomes. The book contains a variety of perspectives beyond the one here, including some that emphasize the adaptiveness of stress reactivity.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Young mother and her baby, sleeping in bed. Photo by SvetlanaFedoseeva, iStockphoto.

Stroke: the dramatic revolution

Stroke is a devastating condition with high rates of mortality and morbidity and profound implications for health economics and resources worldwide. At present, in England alone, stroke is the third largest cause of death and the single largest cause of adult disability. Each year, approximately 110,000 people in England will have a first or recurrent stroke and more than 900,000 people are currently living with the effects of stroke, with half of these being dependent on other people for help with everyday activities. The financial repercussions of stroke are substantial, with an estimated cost to the English economy of £7 billion per year. However, this condition, which was for so long regarded as a low priority and simply a natural consequence of ageing, has undergone something of a revolution in recent times. The field of stroke medicine has seen significant advances and there is an ever increasing awareness that there are real opportunities to make a dramatic difference to stroke patients.

Despite the dramatic revolution in stroke medicine, levels of stroke knowledge amongst the general public remain surprisingly poor, and there are still significant difficulties in getting patients to access stroke services promptly. In an article from a themed collection of papers from the journal Age and Ageing which focuses on stroke, research by Stephanie Jones and her team sought to try and understand these problems. Worryingly, they found that people struggle to name even one stroke risk factor or stroke symptom, particularly when open-ended questions are used. Knowledge is especially poor in older members of the population, ethnic minority groups and those with a lower socio-economic status, but there is also a surprising lack of knowledge amongst those who have already suffered a stroke. Furthermore, there appears to be a real paradox between what people say they would do and what they would actually do in the event of a stroke; whilst at least 47% said they would contact emergency medical services if they suspected they or a relative were experiencing a stroke, only 18% of stroke patients had actually done this. There is therefore an urgent need for further public education. In light of their findings, Stephanie Jones and colleagues suggest that the ideal campaign should minimise barriers to health services and provide cues to action. Their review of previous initiatives suggests that the most effective such interventions have been stroke screening, community educational programmes and first aid training. However, these need to be repeated regularly as their effects are time limited.

Although the findings by Jones et al. are sobering, improving public awareness about stroke is a focal element of the UK Government’s National Stroke Strategy. Another key focus of the National Stroke Strategy is stroke prevention. Hypertension, obesity, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia should all be managed according to clinical guidelines, and appropriate action should be taken to reduce overall vascular risk. Moreover, all those at risk should be given information about exercise, smoking, diet, weight and alcohol.

However, despite our best efforts in stroke prevention, strokes still occur. For those patients, the single biggest intervention which will improve their outcome is admission to a stroke unit and specialist stroke care. There is strong evidence that this significantly reduces death, dependency and the need for institutional care.

The high rates of palliative needs of stroke patients should not be regarded as negative or depressing but instead as a real opportunity to make a positive difference. Furthermore, despite the apparently disheartening and mortality and morbidity rates in stroke, we can afford to be optimistic. The field of stroke medicine continues to grow and evolve and there is a wealth of stroke research occurring locally, nationally and internationally. So, what will this bring? What does the future hold? In the immediate future, we are likely to see changes to the current guidelines on thrombolysis and blood pressure management. Further education of the general public will hopefully yield great rewards in terms of faster access to specialist stroke services and thus better outcomes, and a greater understanding of neuro-plasticity is likely to bring changes in our approaches to stroke rehabilitation. Further down the line, we may see novel treatments such as stem cells being employed in the treatment of stroke, and the review by Soma Banerjee et al. provides a fascinating glimpse into this world.

For now, stroke physicians will continue to build on the core foundations of good primary and secondary preventative strategies, urgent specialist stroke care for all those affected and holistic, multidisciplinary patient-centred rehabilitation.

The revolution continues. Watch this space.

Dr. Victoria Haunton is Clinical Research Fellow and Honorary Specialist Registrar at Leicester University. Prof. Thompson Robinson is Professor of Stroke Medicine at Leicester University. They recently edited an online collection of papers on stroke medicine for the Age and Ageing journal, and this has been made freely available for a limited time.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicines articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

September 30, 2012

Traduttore traditore

By Mark Davie

It’s curious that the language I’ve mostly worked with — Italian — has provided the adage which is routinely quoted in any discussion of the challenges of translation, and yet no-one seems to know who first coined the phrase. It appears in the plural form Traduttori traditori (“translators traitors”) in a collection of Tuscan proverbs by the 19th-century writer Giuseppe Giusti; but this is an isolated occurrence which doesn’t appear to have any literary antecedents, nor is there any trace of the route by which it cut loose from its Italian origins and became a free-floating, multilingual cliché. Perhaps readers can come up with some examples that I’ve missed.

At first sight it seems surprising that the folk wisdom embodied in proverbs should concern itself with the difficulties of such a rarefied activity as translation. But I suspect that’s not what the proverb is about. It’s more plausible to see it as an expression of the wariness in popular culture of any language which is not readily understood, and specifically the distrust of those who use unfamiliar language as an instrument of power. In Italy this has meant, historically, those who used Latin to reinforce the mystique of their profession: priests, lawyers, doctors. Manzoni in I promessi sposi created two characters who have themselves become proverbial for the way they use their meagre stock of Latin catch-phrases to cheat the betrothed couple of their rights: the craven priest don Abbondio and the splendidly-named lawyer Dr Azzecca-Garbugli (for which a literal translation would be something like “coiner of confusion”; Colquhoun’s classic version renders it as “Quibble-Weaver”). Manzoni’s satire hits the mark because he accurately pins down a source of popular resentment and gives it just the right degree of comic exaggeration. The proverb expresses the same resentment, and its plural form is eloquent, as if the only conclusion to be drawn from long collective experience of translators — those who hold the key to knowledge hidden in an unknown language — is that none of them are to be trusted.

At first sight it seems surprising that the folk wisdom embodied in proverbs should concern itself with the difficulties of such a rarefied activity as translation. But I suspect that’s not what the proverb is about. It’s more plausible to see it as an expression of the wariness in popular culture of any language which is not readily understood, and specifically the distrust of those who use unfamiliar language as an instrument of power. In Italy this has meant, historically, those who used Latin to reinforce the mystique of their profession: priests, lawyers, doctors. Manzoni in I promessi sposi created two characters who have themselves become proverbial for the way they use their meagre stock of Latin catch-phrases to cheat the betrothed couple of their rights: the craven priest don Abbondio and the splendidly-named lawyer Dr Azzecca-Garbugli (for which a literal translation would be something like “coiner of confusion”; Colquhoun’s classic version renders it as “Quibble-Weaver”). Manzoni’s satire hits the mark because he accurately pins down a source of popular resentment and gives it just the right degree of comic exaggeration. The proverb expresses the same resentment, and its plural form is eloquent, as if the only conclusion to be drawn from long collective experience of translators — those who hold the key to knowledge hidden in an unknown language — is that none of them are to be trusted.

This is, of course, ironic, because translators conceive their task as being the very opposite of obfuscation; their aim is to make insights, experiences, perceptions which have been expressed in one language accessible to speakers of another. And because, by definition, this involves finding ways to express alien concepts from an alien culture, the process is necessarily imperfect, involving a succession of compromises in the search for an equivalent in the target language. All translators know this from experience, and some writers on translation have defined it, borrowing an analogy from engineering, as “translation loss.” As energy loss is an unavoidable fact of mechanics — no mechanism can be 100% efficient, and the best a designer can do is manage the loss as productively as possible — so translation loss is similarly unavoidable. A perfect translation is no more attainable than perpetual motion. So the translator’s task is not to attempt the impossible but rather to manage the losses in translation and find compensating gains. In a literary translation, it’s not hard to see that this might involve sacrificing literal accuracy for the sake of a more faithful rendering of the style or tone of the original; but a different kind of translator might well make different choices. A user of a textbook or an instruction manual, for instance, will expect the translation to be clear and unambiguous, and would consider some loss of elegance or succinctness as a price worth paying.

These reflections are prompted by my recent experience of translating Galileo, himself famously forthright — his inability to settle for bland ambiguities being what got him into trouble with the church. Among all his other activities he found time to write literary criticism, and he once commented tartly, on a line of verse by Tasso who had the misfortune to be his bête noire, that “anyone can speak obscurely, but very few clearly.” If that isn’t enough of a gauntlet thrown down for his translator, Galileo went one better by becoming, in effect, the translator of his own work. In 1610 he published in Latin, the international language of science, his account of his observations of the moon and planets through a telescope; but thereafter he wrote all his major scientific works in Italian, and for the wider, non-specialist public that this implied. The result was a prose style which had all the colloquial pungency of the vernacular while losing none of its scientific rigour, and its impact on Galileo’s contemporaries was profound. It’s a prose which requires the translator to choose how to highlight these contrasting qualities and to strike a balance between them.

In the end, my experience has been that of every translator — that for every solution that satisfies your professional pride there will be another compromise where you feel there must be a better answer if only you could find it. Or, to quote another of Giusti’s proverbs, “A tutti i poeti manca un verso.” But that’s another translator’s challenge in itself.

Mark Davie has taught Italian at the Universities of Liverpool and Exeter, and has published studies on various aspects of Italian literature, mainly in the period from Dante to the Renaissance. He is particularly interested in the relations between learned and popular culture, and between Latin and the vernacular, in Italy in the Renaissance. He is the translator of Galileo’s Selected Writings, Oxford World’s Classics edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography, language, word, etymology, and dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Photo of the Pocket Oxford English Dictionary, 10th edition, page 974, focusing on “translate.” Taken by Alice Northover with Instagram Amaro filter and radial selective focus.

September 29, 2012

Truman Capote’s artful lies

Why did Truman Capote try writing his last unfinished book, Answered Prayers? In a sometimes ruthless sautéing of jet set high society, he oddly and self-destructively scorched many of his closest friends, women like Babe Paley and Gloria Vanderbilt, among unlucky others, whom he liked to call, in a better mood, his “swans.” It turned out to be a sideways suicide. He never recovered from the fallout. His last years were a hurricane of drink, drugs, and artistic fragmentation.

In working to understand Capote — his childhood, his memories, his relational strategies — it is necessary to come to some kind of terms with a feature of his life that seemed, on its face, rather squirrely. He lied. Or to put it less baldly, he felt zero obligation to stick to the facts. The story was the thing. Getting the details of the story right came a distant second, always. So what to do? Can one write a psychobiography of a born fictionalizer, a person for whom the past is endlessly malleable, improvable?

Truman Capote. Photo by Jack Mitchell, 1980. Creative Commons License.

Take, for instance, Capote’s very first memory, the sort of thing psychobiographers routinely single out and seize on. He says he was locked in a hotel room at age two, left alone by his parents as they cavorted about town. The effect was emotional devastation. The episode crystallized a lifelong pattern of abandonment followed by rejection sensitivity. Or did it? The trouble is, every time Capote told this tale — and he did so incessantly — he altered it. Sometimes he was older than two. Sometimes it was his mother who locked him in, not both parents. The location even changed. The question then becomes: Did the incident occur at all? And more to the point, does it matter?My answer to the first question is: who knows? My answer to the second: no, it doesn’t. Now, this might seem cavalier. Aren’t psychobiographers supposed to care about the facts? Yes, facts are crucial. Facts are the instruments of revelation. I love facts. But the reality is, remembered life is itself fiction, a constantly evolving construction. That being so, the raw material one works with is best approached as a “faction” — a composite of artful narrative and quantifiable life-history. And given the unreliability of memory, especially in someone like Capote, who saw his past as perfectible, all one can do is dive into the messy blurriness.

The hotel lock-in may have been partly imaginary, it may have been entirely imaginary. In either case, it was psychologically real. Capote told the story over and over because it captured something essential about his emotional life; it summed up, in one neat mobile package, who he was and why he did what he did. Capote, no doubt, would have sided with fellow raconteur Oscar Wilde, according to whom truth was “entirely and absolutely a matter of style.”

Capote also fibbed about Answered Prayers. He exaggerated its length, described chapters that hadn’t even been written. Here again, the question isn’t did he really write it, but why he felt the need to pump it up, pretend it was more than it was. To Capote, words were power. The book had to exist, because without it, he didn’t.

In some ways the lie is more important than the truth. The lie is fantasy, and fantasy is creative product, yet another work of art to dissect and interpret. People kill themselves over false memories. That fact alone makes it clear that false is anything but. It’s a question of the value of the memory, not its accuracy.

William Todd Schultz, PhD, is Professor of Psychology at Pacific University in Portland, Oregon, and author of Tiny Terror: Why Truman Capote (Almost) Wrote Answered Prayers. Over the past two decades he’s written numerous psychobiographical articles and book chapters, on Ludwig Wittgenstein, Diane Arbus, Sylvia Plath, Oscar Wilde, Roald Dahl, James Agee, and Jack Kerouac, among others. He is editor of the Handbook of Psychobiography (Oxford University Press, 2005) and the Inner Lives series for Oxford, author of An Emergency in Slow Motion: The Inner Life of Diane Arbus (Bloomsbury, 2011), and is currently writing a biography of musician Elliott Smith.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Author photo courtesy of JJ Gonson Photography.

September 28, 2012

Did Obamacare’s court victory win over Americans’ hearts and minds too?

The Supreme Court’s decision in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius achieved a level of media coverage and public salience reached by very few Supreme Court decisions. It represented a political moment, if not a constitutional one. Although legal scholars might focus on the doctrinal importance of the decision for shaping the contours of congressional power, this unusually high profile case is also fascinating to study as an event that structured public opinion about the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Court itself. As such, it also presented a unique test for larger theories about the role of the Supreme Court as an agenda-setter for public opinion.

Perhaps more than any case in the post-New Deal period, the Health Care case evolved into a judicial referendum on a President and his signature legislative achievement. Leading up to the decision, media coverage resembled that of a sporting event or a campaign. It became clear that the case would end with a reported “win” or “loss” for the President. Coming, as it did, five months before the President would stand for reelection, the decision also threatened to frame the presidential race in unprecedented ways.

Our research examines the effect of the Court’s decision on public approval of the Court and the ACA.

The data suggest that the Court’s decision had a small but noticeable impact on attitudes toward the Court and the ACA. Although the Court found itself with historically low approval ratings before the decision, it dropped further soon after the opinion’s release. Moreover, the structure of opinion toward the Court became more polarized along partisan lines following the decision. Given the partisan split in opinion over the ACA, perhaps this should come as little surprise.

The Court gave a win to the President, so Court approval and presidential approval became more aligned following the decision. Less obvious, however, might be the effect of the decision on attitudes toward the ACA. The Court’s perceived stamp of approval for the ACA led some Americans to switch their minds about it, leading to a small increase in approval of the law following the decision. Some of this opinion transformation might simply have come from the favorable media attention heaped on the law as a “winner” at the Court. In other words, the Court’s upholding of the law sent a signal that it was objectively good policy.

For still others, the decision provided an opportunity for elite discussion and persuasion, instituted in particular by the President, who either convinced them on the law’s merits or triggered their latent approval for him by expressing newfound support for the law. In other words, precisely because the decision clearly defined the political stakes and discussion surrounding it became more politically polarized, support for the Act (which had lagged presidential approval) now became more closely correlated with it.

Andrea Campbell and Nathaniel Persily are the authors of “The Health Care Case in the Public Mind: How the Supreme Court Shapes Opinion About Itself and the Laws It Considers” which appears in the upcoming The Health Care Case (May 2013). It’s an all encompassing, ideologically diverse edited volume on the case featuring the nation’s leading lights in constitutional law.

Andrea Campbell is a professor of political science at MIT. Her interests include American politics, political behavior, public opinion, and political inequality, particularly their intersection with social welfare policy, health policy, and tax policy. She is the author of How Policies Make Citizens: Senior Citizen Activism and the American Welfare State (Princeton, 2003) and, with Kimberly J. Morgan, The Delegated Welfare State: Medicare, Markets, and the Governance of Social Provision (Oxford, 2011). She recently wrote an op-ed for the New York Times.

Nathaniel Persily is the Charles Keller Beekman Professor of Law and Professor of Political Science and the Director of the Center for Law and Politics at Columbia Law School. Professor Persily’s scholarship focuses on American election law or what is sometimes called the “law of democracy,” which addresses issues such as voting rights, political parties, campaign finance, and redistricting. he is a frequent commentator on the Supreme Court.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers