Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1015

October 10, 2012

A global ingle-neuk, or, the size of our vocabulary

The size of our passive vocabulary depends on the volume of our reading. Those who grew up in the seventies of the twentieth century read little in their childhood and youth, and had minimal exposure to classical literature even in their own language. Their children are, naturally, still more ignorant. I have often heard the slogan: “Don’t generalize!” and I am not. I am speaking about a mass phenomenon, not about exceptional cases. Try the simplest experiment: walk into a room full of college students and ask: “Have you read…?” Name any book from Gilgamesh to Goodbye, Columbus (the titles have been chosen for the sake of alliteration) and see how many of those present will raise their hands. So far, I have discovered only one “text” everybody seems to know, to wit, “Chicken Little” (“The Sky Is Falling”). Given the state of the market, recent authors use only the vocabulary their public can recognize; the more primitive the language, the more copies the publisher will sell. A student complained to me once that he had difficulty understanding my colleague who teaches Russian. I was surprised because I knew the man; his Russian is excellent. “You cannot understand his Russian?” I inquired. “No,” was the answer, “I don’t understand the English words he uses.” (Both the instructor and the student were native speakers of American English.) I remember similar remarks from my own experience and have been working for years on diminishing my “word hoard.” Compare the vocabulary of Charles Dickens and George Meredith with that of the books remaining “ten weeks on the NYT Best Seller list” and draw your own conclusions.

These thoughts occurred to me when I was looking through an eleven-page glossary appended to the Oxford edition of Walter Scott’s Old Mortality (Oxford World’s Classics, 1993). It is an exemplary edition and there was every reason to supplement it with a glossary. Many of the local words in the novel were and are foreign to readers south of the border, but quite a few surprised me. Is it possible that someone who can still enjoy Walter Scott should not be able to recognize them? My examples will be relatively few. Since this is an etymological blog, occasional hints to origins are given below (the spelling in the definitions will be those of the British edition).

Besom “broom; bad-tempered woman” (common to all the West Germanic languages; cf. German Besen) Few will remember the biblical source of the figurative sense, but what about the direct sense “broom”?

Bide “wait, tolerate, endure.” Are the phrase bide one’s time and the connection between bide and abide forgotten? (In abide, a- is a prefix, as in amaze, ashamed, and so forth.) A related question can be asked about fend “protect, provide, etc.” Do the phrase to fend for oneself and the closeness of fend to defend provide no clue to the meaning of fend?

Blithe “happy” (a common Germanic word; bliss is related to it). It means “joyous,” but the distance between “joyous” and “happy” is not great. The adverb blithely seems to occur more often than the adjective.

Brogue “coarse shoe” (a noun of Celtic origin). Brogue “Irish accent” and its probable association with brogue “shoe” must be alive, at least in the UK; however, I cannot judge.

Cronie, known to me only as crony (seventeenth-century university slang, ultimately from the Greek word for “time,” as in chronology, chronicle, and others). Do only Americans speak contemptuously about Mr. X and his cronies?

Dram “a drink of whisky” (ultimately again from Greek); a very common word in nineteenth-century books.

Duds “rags; clothes” (of obscure origin). In my post on dude, I discussed its unlikely derivation from duds and took everybody’s familiarity with duds for granted. Was I mistaken?

Bartizan, Greenknowe Tower, Scottish Borders. Photo by Supergolden, 2006. (CC-BY-SA)

Bartizan “overhanging look-out turret projecting from a tower or parapet” and escalade “scaling the walls of a fortress using ladders” are like most Middle English military terms from French, though bartizan is a pseudo-archaic use of the Scots variant of bratticing (see the OED [sub req'd]), a word introduced and popularized just by Walter Scott. Obviously, vampires, witches, and wizards have ousted medieval knights from the popular imagination. Harry Potter vanquished Ivanhoe, and roaring lions are no match for silent lambs, but still…Causeway “paved road” (a Romance word; it has nothing to do with cause: the loss of l in the middle severed the tie between its root and the reflexes of Latin calx “chalk’). I doubt that the noun has fallen into oblivion.

Harry “drag by force” (Common Germanic except Gothic). Does the biblical phrase the harrying of hell shed no light on the verb?

Mad “angry.” Don’t we still say: “I am mad at you”?

Nice “discriminating.” Everybody understands that nice distinctions are not necessarily pleasant distinctions, so that the older connotations of nice have not been wholly superseded by its present day meaning. (Compare fine dust: we don’t think that such dust is excellent.)

Touzle “disarrange.” This is a variant of tousle, as in tousled hair. Wait for glosses like realise “realize” and vice versa.

Grewsome is “gruesome.” Are we such matter of fact, down to earth people that we need help even here? Another spelling “conundrum,” as learned people like to say, is shamoy leather “chamois leather,” that is, chamois.

Hoity-toity belongs to an age gone by. Consequently, the interjection hout-tout (the same meaning) is probably opaque; too bad.

Worsted “woollen thread” and hodden grey “home-spun coarse woollen cloth.” Worsted (from a place name) must be clear to everybody; hodden (of uncertain origin) often occurs in nineteenth-century fiction, and not only in the works of Burns and Scott.

I assume that the game trick-track is more familiar to modern readers that bartizan, but there is a helpful gloss here too.

I have no idea how well people in the UK know regional words:

Bannocks, we are told, are flat cakes of oatmeal baked on a griddle, and that is what they certainly are.

Ingle-neuk (neuk = nook) “chimney corner.” Neuk is rather hard to guess, but ingle, a dear old word, must be less puzzling.

Humble cow “hornless cow” will indeed look odd to some people despite the phrase’s spread in northern dialects. Humble cows are not known for their humility, and Tacitus already noted that the ancient “Germans” cultivated this breed.

The glossary explains shaw “wood, thicket.” Doing so must have been a good idea. I have often cited shaw in my classes, while explaining Old Norse skógr “forest, wood.” No one recognizes shaw (or, for that matter, its synonym copse), though everybody knows the corresponding family name. As a result, I have to point to shaggy, another cognate of skógr.

Quean “girl, wench” has also faded from memory. I know this fact from my futile attempts to use Engl. quean in teaching Old English and Gothic. (Quean is not a doublet of queen: the two words are congeners, but at one time they had different vowels, a fact imperfectly rendered by the modern difference between ea and ee.)

Guessing that lassock is a diminutive of lass might not be too hard (cf. bittock “a little bit” in the glossary), and perhaps most southerners are aware of the fact that northern -g corresponds to southern -dge, so that “translating” brigg as “bridge” (especially in context) would not have been too formidable a task.

My list (I have a few more words to discuss but can do without them) is not meant as a criticism of an admirable edition. Obviously, the editors appraised the state of people’s knowledge of English quite accurately and did the right thing. Nor am I in the habit of bemoaning “the lost treasures of English.” Words die and spring up every day. But we needn’t accelerate the death of what should stay alive. The appearance of an insurmountable barrier between older culture (I say “older,” not ancient or medieval) and modernity is always sad to watch. We have reached a stage at which our young people feel comfortable only in dealing with one another, especially when they sit in a global ingle-neuk, text from the most recent contraption, and crunch a homemade bannock. Life is beautiful, but I am afraid this is not much of a subject for congratulation.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

New York’s “Dress Wars”

In the depths of the Great Depression, TIME magazine offered readers a glimpse at New York’s “Dress Wars.” Knockoffs, TIME wrote, were everywhere in the garment industry and “dirty tricks” increasingly ubiquitous:

Among such tricks was the universal and highly developed practice of copying original styles. By the early Depression years it had gone so far that no exclusive model was sure to remain exclusive 24 hours; a dress exhibited in the morning at $60 would be duplicated at $25 before sunset and at lower prices later in the week. Sketching services made a business of it; delivery boys were bribed on their way to retailers.

The American fashion industry’s response to the widespread practice of copying was to create a guild, one that would police copying amongst its members and ensure that retailers who sold knockoffs of guild members’ designs would be shunned and sanctioned. That Depression-era system remained in place for several years. But eventually the US Supreme Court ruled the “Fashion Originators Guild” an illegal cartel.

The Court’s decision destroyed the Guild. In its wake, Maurice Rentner, the former head of the Guild, devoted himself to lobbying Congress to extend copyright protection to fashion designs. Unless Congress acted, he warned, resurgent fashion piracy following the fall of the Guild would “write finis” to the dress industry. In the 1940s Rentner urged Congress to adopt the French system of protecting garment design, lest 500,000 jobs be lost to the better-protected French, and others.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. At least, that’s true in the world of fashion copying. Just as Maurice Rentner declared that the fashion industry would be killed by the plague of knockoffs, so too do modern-day Rentners foresee a greatly diminished apparel industry — unless Congress acts quickly to stem the tide of knockoffs.

Which brings us to this fall’s Fashion Week in New York. The senior Senator from New York, Charles Schumer, used the occasion to introduce the Innovative Design Protection Act, or IDPA, which for the first time in American history would create an unusual three year form of copyright for apparel designs. In promoting the bill, the Council of Fashion Designers of America, a leading trade group, echoed Rentner’s cri de cœur from 70 years ago:

The fashion industry plays a vital role in the New York economy. The fashion industry employs nearly 200,000 people in New York City alone, generates nearly $10 billion in total wages, and generates tax revenues of $811 million. Over 800 fashion companies are headquartered in New York City, more than double the number in Paris, yet French designers have greater copyright protections…. But these jobs and this revenue for New York are currently in jeopardy because the United States does not provide any protection for fashion designers against having their designs pilfered. If Congress does not act, the US risks losing these jobs to Europe or to Japan, which offer more stringent intellectual property protections to shield the industry from design thieves.

The problem with Senator Schumer’s proposal is the same problem Maurice Rentner faced. Fashion functions very well without intellectual property protection. In fact, the fashion industry not only survives widespread copying; it thrives due to copying. Copying is, in many ways, the engine of the industry. Which is a very important reason that, in the many decades since Maurice Rentner’s apocalyptic predictions, the industry has grown and grown. Even the proponents of the IDPA can’t resist noting that there are twice as many fashion companies in (unprotected) New York than in (protected) Paris.

Fashion — and other fields that similarly exhibit creativity coupled to fashion — poses a quandary for more than Senator Schumer and the CFDA. Fashion challenges some of the central features and principles of our system of intellectual property. The primary goal of intellectual property law is to promote innovation; the primary means is to grant creators a monopoly over their designs, so that competitors cannot copy them and, it is assumed, outcompete them. What the fashion industry shows is that this relationship may be true in some cases, but it is not true in all. Copying does not always kill the incentive to create, nor do copyists always outcompete originators.

How does this work in fashion? There are two key ways.

The first rests on a key feature of the fashion cycle. That styles rise and fall is of course not a new observation. Shakespeare declared in Much Ado About Nothing that “the fashion wears out more apparel than the man.”

What Shakespeare (and Cocteau, Simmel, and many others) noticed was not merely the rise and fall of apparel designs. Instead, they highlighted the fact that the rise actually led to the fall. The fall was not merely inevitable, in the sense of a ball thrown into the air that gradually succumbs to gravity. They drew a causal connection: as fashion spreads, its distinctiveness is destroyed. That in turns destroys much of its value, because the essence of fashion is that it supplies status through distinctiveness.

Of course, not everyone seeks distinctiveness in fashion. Just look at America’s political class: for the men, an orange or purple tie is a mark of outright zaniness, and the women largely hew to pantsuits and jackets that look more like armor than fashion. But for the class of fashion early adopters, things are different. These early adopters seek to stand out, whereas the next tier of buyers seeks to “flock” to the trend. As the flockers flock, the early adopters flee.

The fashion cycle, in turn, interacts in a critical way with the legal freedom to copy. Legal rules that permit copying accelerate the diffusion of styles. That diffusion, in turns, leads to more rapid decline. And more rapid decline creates a faster, more intense appetite for new designs, which, when copied, spark the creation of new trends — and, as a consequence, new sales.

Copying, in short, is the fuel that drives the fashion cycle faster. It is essential to both the trend-making and trend-destruction processes.

The freedom to copy does something else important. It facilitates variations on the theme — what lawyers refer to as “derivative works.” These are garments that use the original design, but tweak it in some new way. Under standard copyright law, the originator has the exclusive right to make or authorize derivative works.

The legal rule for fashion is the opposite, and the many variations on a theme this makes possible means that the stores will be full of countless versions of a popular design. And that makes it easier for fashion-conscious consumers to figure out how to dress fashionably.

The key point remains the same: existing rules, by permitting this kind of copying, act as a kind of turbocharger to the fashion cycle. And that spurs designers to create anew so as to ride the next wave of trends. Far from destroying the fashion industry, the freedom to copy is a central force for innovation and growth. This has been true since the “Dress Wars” of the 1930s, and is still true today.

Kal Raustiala is Professor of Law at UCLA and the author of Does the Constitution Follow the Flag? He is the co-author of The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation with Christopher Sprigman. Visit the Knockoff Economy website for more information, or like them onFacebook.Christopher Sprigman is the Class of 1963 Research Professor at the University of Virginia School of Law. You can follow him on Twitter at @CJSprigman or on Facebook. Watch an interview with Christopher Sprigman on knockoffs in the creative economy.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Achievement, depression, and politicians

Does depression mean low achievement and social exclusion? Until recently the British law has suggested that this is the case…

‘For two or three years the light faded from the picture. I did my work. I sat in the House of Commons, but black depression settled on me.’

Starter for ten: who said this? (Apologies if you haven’t watched University Challenge). It was Winston Churchill, arguably the greatest British prime minister and certainly one who played a crucial role in guiding his nation through the Second World War. Churchill was, off and on, a sufferer of depression, which he called his ‘black dog’, following Dr Samuel Johnson, that great depressive of the eighteenth century and creator of the magnificent edifice of learning that was his Dictionary of the English Language. This particular comment by Churchill — to his doctor later on in life — refers to a bad bout of the melancholic condition in 1910. Churchill had thoughts about suicide, and was afraid of standing too near the edge of train platforms or the railings of a boat lest he be tempted to ‘end everything’. Nonetheless, Churchill managed his condition and went on — as we know — to be one of the iconic figures in British history.

This year the theme of World Mental Health Day, on 10 October 2012, is ‘Depression: A Global Crisis’. According to the World Health Organization, ‘unipolar depressive disorders’ (what we might think of as ‘major depression’ without the manic highs) were ranked as the third leading cause of the global burden of disease in 2004 and will move into the first place by 2030. There are many arguments about what exactly depression is, what might cause depression, how it might be diagnosed, and certainly many arguments about how it should be treated. Indeed there is a debate to be had about whether depression is under- or over-diagnosed. Clearly depression, like people, is a complicated phenomenon that needs to be carefully considered in the light of the circumstances of each individual, including their social world as well as the biological one.

Despite the intricacies of the depressive experience, we have some effective treatments for depression (however defined) that could help a great many people, whether they be the talking cure of CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) or the biological one of drugs like the famous Prozac (now partly superseded by newer forms of drug). Sometimes the two approaches are best combined, and sometimes more radical cures can be used. Either way, a great deal of research effort in many disciplines has been put into depression, and we are progressing, hopefully, and in fits and starts, towards a better understanding of the condition and its nuances.

It is both cheering and saddening to find, then, that at almost the same time as the WHO is promoting awareness about depression, the British parliament is going through the process of removing archaic laws that state persons who have had mental health problems are not allowed to serve as jurors, MPs, or even be a company director. Saddening, because it has taken until 2012 to get rid of laws dating from 1886, but cheering because attitudes to mental health are at last catching up with the more enlightened vision of physical disability exemplified so gloriously by the recent Paralympics.

Reading Hansard’s record of Parliamentary proceedings might not suggest itself as the most interesting activity for the average person, and many (like myself) probably share a deep suspicion of politicians in general, but when I read the 14th September debate on The Mental Health (Discrimination) Bill I was impressed by the quality of the debate and the unanimity with which the participants supported the Bill. The old laws encouraged the perception of mental health problems as abnormal and irreversible, rather than as common problems susceptible to cure and recovery.

Which takes us back to Winston Churchill, strangely unmentioned in the parliamentary debate, who is one of the best examples of how a person with depression can not merely cope with their condition but also be as successful as it is possible to be in one’s chosen profession, whether it be a politician like Churchill or man of letters like Samuel Johnson. Female examples of high-functioning depressives (to take just one mental health condition) are also legion. The parallel is not exact, but just as the paralympians have put the focus on ability rather than disability, so we have many historical and contemporary examples of people who live with mental health problems of varying severity, and yet make a huge contribution to their fellow human beings in whatever occupation. Of course depression involves suffering that we ideally wish to eradicate, but until that day comes it is crucial to remember that mental ill health, like physical ill health, is not an insuperable barrier to achievements of the highest order.

I had a black dog, his name was depression.

In collaboration with World Health Organisation to mark World Mental Health Day, writer and illustrator Matthew Johnstone tells the story of overcoming the “black dog of depression”.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Clark Lawlor is Reader in English Literature at Northumbria University, and is especially interested in the cultural history of disease. He has been publishing work on the history and representation of depression recently, partly as a result of his co-Directorship of Before Depression, a Leverhulme Trust-funded project on the nature of depression in the eighteenth century. His most recent work, From Melancholia to Prozac: a history of depression, published in early 2012. He previously published Consumption and Literature: The Making of the Romantic Disease (2006). Read his OUPblog post on imagining depression in literature.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

October 9, 2012

Obama out of practice for first debate

President Obama had a bad night. The key to succeeding in a presidential debate is recognizing that it is not a parliamentary debate. The rules, the moderator, and even the immediate audience (since they are not permitted to applaud) do not matter. Instead, candidates should bare their souls to the camera lenses. There, magic is made.

Like a legislator used to addressing the president of the chamber and not the audience, Obama was too formal that night. Obama was looking down on his notes too often when Romney was speaking. Silent moments matter too — because candidates can still connect with the audience with their eyes. Even when he was not looking down, Obama was looking at Jim Lehrer rather than at the camera most of the time.

Obama’s advisors must have, rightly, warned Obama not to lose his presidential poise. But they forgot to add that in a two-person setup, a basic modicum of aggressiveness was required. Given that Obama’s countenance is naturally already cool, he would have benefitted from a reminder that he’s back on the campaign trail, president or not. Advisors should tailor-make advice for their candidate. Next round, they should tell Obama to forget that he is president. He should look into the camera at every moment, when his talking and when he is silent, pleading for the vote. Obama should also keep an internal clock, knowing that Jim Lehrer did him no favors last debate by allowing him to ramble longer than the pre-allotted two-minute segments.

Obama tried too hard to take Romney to task on the specific numbers of his tax plan. But there are no scorers in presidential debates. It doesn’t actually matter who won the logical argument; but it does matter who passed the plausibility threshold. Mitt Romney did last night. He kept repeating the $716 billion cut from Medicare and in American politics, saying it is so, makes it so. Nobody cares about what the fact-checkers are saying today. Or about Dodd-Frank or Simpson-Bowles. Or whether rebuttals come the day after. Over 10 million tweets were shared as the debate proceeded last night, many about Big Bird, and most declaring Romney victorious.

Obama’s biggest missed opportunity was on the discussion about the role of the federal government, when Obama normally would have excelled. Romney rightly reached to the sacred scripture of the Republican Party, the Declaration of Independence, referring to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Obama failed to counter. The sacred scripture of the Democratic Party is the Preamble of the Constitution. Life, liberty and happiness matter, but so do justice, a more perfect Union, and the general welfare. Bill Clinton knew this when he gave his spectacular speech at the DNC Convention. Obama forgot his roots last night.

In terms of the horse race, this was not a game-changer; it certainly would not change the ground game in the electoral map. There were no forced errors on Obama’s part, just missed opportunities. He should be advised, however, not to go overboard the other way in the next debate, as Al Gore had done in 2000. Obama was wise not to mention the 47 percent comment or offshore bank accounts. That information is already out there and there is no need for the President of the United States to do the dirty work that his surrogates can.

Obama is a quick rebounder. He will be back in the game in the next debate, and we will have a showdown.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Reflections on the first presidential debate

As the first presidential debate recedes in the rearview mirror, we may be able to gain clearer perspective on what it means to the 2012 presidential race.

For starters, the clear winner was the news media. No one likes a one-sided presidential campaign, and that was the direction of the contest over several weeks prior to the debate. To keep the audience interested, the race has to remain reasonably close. One doesn’t need to see dark conspiracies, then, to suggest that the pundits were keen to find signs of life in Mitt Romney in the first debate. He delivered a smooth and poised performance, delivering his message clearly, and thus gave the media exactly what they most desired — a plausible comeback story to fuel popular interest over the remaining weeks of the campaign. In the wake of the debate, moreover, the opinion polls will likely tighten, too, which will contribute to the narrative of a dramatic comeback possibility. It’s the kind of horse-race story the media can cover well, far better than the issues.

Whether the comeback story is real, though, is another matter. Many observers have commented on the limited impact of presidential debates. Unless the favorable impression registered by the winner is reinforced by subsequent events, the impact tends to be fleeting. Most voters have already made up their minds (this year even more than is usually the case) and no debate performance will unsettle their convictions. They also watch the debate through a set of filters that make them root for the candidates rather than assess the arguments. President Obama’s supporters were disappointed that he missed a number of opportunities to challenge Romney’s assertions and claims, rather like football fans groaning when their team’s quarterback overthrows an open receiver in the end zone. Their team may lose, but they don’t abruptly start rooting for the other team.

In this vein, I decided to ask the students in my large American government class the day following the debate how many of them had changed their minds based on the debate. Out of roughly 170 students, two raised their hands. (I did not ask them how their views had changed.) Although hardly a scientific approach, the result was in line with much other evidence about the effects of a debate.

And my informal survey took place before other events began to reclaim the news cycle. Friday brought news that unemployment had dropped below 8% for the first time since President Obama took office. It’s only one statistic, of course, and the gain masks a number of disappointing trends such as the increase in the ranks of those who have given up looking for a job, but the unemployment rate also is one of the few numbers that everyone understands. The administration will play up the improvement as part of its narrative of a slow but definite economic recovery. Events like this can move the electoral conversation away from a debate performance very quickly.

Past presidential campaigns suggest another reason why the Republican challenger will have a hard time sustaining any momentum from the first debate. Candidates rarely repeat poor debate performances. In 1984 Ronald Reagan put on a dismal display in his first debate with Walter Mondale, briefly reviving the Democrat’s hopes while prompting concerns about his own fitness for a second term. By the second debate, Reagan’s advisors made certain he was ready; besides giving sharper answers, he dealt effectively with the age question by quipping that he did not think Mondale’s relative youth and inexperience should be held against him. The next time around Romney should find himself up against a different Barack Obama, one better prepared to attack the Republican’s lack of experience in foreign policy.

One final note, on the matter of the president’s debate style; a number of commentators described Obama as “too professorial.” That is an insult to professors, at least the good ones. In the classroom, I make an effort to state a clear thesis, present some compelling evidence without overwhelming my listeners by citing every related factoid, and respond to questions directly and succinctly. When professors speak as the president did, students tune out and surf the web. You made us look bad, Mr. President, and we don’t like it.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The triple-negative diet to fight breast cancer

In honor of Breast Cancer Awareness Month, we’ve pulled the following excerpt from Surviving Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Hope, Treatment, and Recovery by Patricia Prijatel. She provides a quick guide on how to eat healthy in order to better fight the disease.

This is the approach I take, based on the research I have done. It works for me, but you have to find what works best for you. Choose an approach you know you can stick to. Don’t try to be Super Healthy Cancer Woman — that just adds more stress. Aim to be as healthy as you can be, and allow yourself to fall off the wagon occasionally. That is the only way you will stay on long-term.

Breakfast: According to the National Weight Control Registry at Brown University Medical School, 78 percent of the people who lost more than 30 pounds and kept it off for more than a year regularly ate breakfast. I always eat breakfast; my two approaches to it:

A breakfast smoothie with blueberries (antioxidants), flax- seeds (cancer-fighting fiber), bananas, black cherry (more anti- oxidants) juice, and yogurt (bone-building and cancer-fighting calcium). This gives me two servings of fruits and one serving of calcium. Make sure you use ground flaxseed, because whole seeds just go right through you. And once they are ground, store them in the refrigerator.

Cooked oatmeal with blueberries. It’s simple—just follow the directions for one serving on the oatmeal box, and add about1/2 cup of blueberries. Oatmeal soaks up cholesterol, so it is good for your heart as well.

Mid-morning snack: A piece of fruit, 1/8 cup of seeds, and 6–8 almonds.

Lunch: Eat a hearty but healthy lunch — you should expend more calories here than at dinner. I opt for soups, salads, whole-wheat pasta dishes, or sandwiches with low-fat whole-wheat bread. I look for combinations of spinach, broccoli, asparagus, green beans, romaine, and other dark greens; low-fat cheeses or yogurt; and whole grains. Tuna or egg salad sandwiches made with low-fat mayonnaise or yogurt and low-fat whole-wheat bread; 1/2 fresh bell pepper sliced; and a spinach salad makes a nice little lunch. I often treat myself to a scoop of frozen yogurt for dessert. One scoop is enough to satisfy me. (Usually.)

Click here to view the embedded video.

Midday snack: Some of my favorites:

Broccoli and cauliflower dipped in hummus.

Whole-wheat crackers and organic low-fat cheese.

Popcorn (a whole grain that folks tend to ignore) with a light covering of sea salt. No butter.

Homemade trail mix of pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, raisins, unsweetened dried cranberries, and almonds. You need no extra salt or sugar.

Strips of bell peppers, powerful antioxidants high in vitamin C and E. (Red peppers are especially nutrient-rich; a small one contains 46 percent of your daily requirement of vitamin A and 158 percent of your vitamin C. By contrast, a green pepper of the same size has 5 percent of your daily vitamin A and 99 percent of your vitamin C.)

Juiced veggies every evening: This includes three to four carrots, one to two leaves of kale, 1/8 cabbage, one bunch parsley, one stalk celery, 1/4 apple, and 1/4 lemon. My super-juicing husband uses an auger juicer that takes the pulp out and leaves only the juice. This gives me two to three servings of veggies and is heavy on cancer-fighting cruciferous vegetables — kale and cabbage. The lemon, apple, and celery really help the taste.

Dinner: I go mostly vegetarian, with some fish and seafood.

I have come to love sushi made with avocados, eggs, cucumbers, and celery (I’m not ready to try raw fish).

Menus planned around broiled or baked fish or meat are good; combine this with steamed vegetables, brown rice, or sweet potatoes.

Stir-fry is an easy way to combine brown rice, shrimp or chicken, and veggies such as broccoli and bok choy. Avoid cheese sauces and gravy — these are delicious gutters of calories.

Soup and salad is healthy and easy. A cup of tomato soup and a spinach salad with vinaigrette gives you a couple of servings of vegetables with minimal calories. Bean soup can be a great source of protein as well as vitamins and minerals.

For dessert, consider angel food cake, frozen yogurt, or a few squares of dark chocolate, which, yes, is an antioxidant. Milk chocolate is not.

Patricia Prijatel is author of Surviving Triple-Negative Breast Cancer, published by Oxford University Press. She is the E.T. Meredith Distinguished Professor Emerita of Journalism at Drake University. She is doing a webcast with the Triple Negative Breast Cancer Foundation on 16 October 2012. Read her previous blog posts: “Just what is triple-negative breast cancer?” and “Fighting Triple-Negative Breast Cancer.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The point of no return

If a theater noob polled a group of theater fans on what classic musicals she must see to jumpstart her theater education, you would be hard pressed to find a fan without The Phantom of the Opera on their list. The show, which opened at Her Majesty’s Theatre in London on 9 October 1986, has left an undeniable impact on London’s West End, Broadway, and theater in general. I can personally attest to listening to the original cast soundtrack growing up, seeing the 2004 movie with my theater friends as soon as it came out (and proceeding to listen and sing loudly to that soundtrack on every car drive for months), to finally seeing the Broadway production in 2007 and being absolutely blown away.

In honor of the anniversary of The Phantom of the Opera opening in London 26 years ago today, we thought a mini quiz was in order.

Phantom of the Opera is based on a novel. What year was it written?

According to the novel, what is the phantom’s real name?

Who were the original actors for the characters of Phantom, Christine Daaé, and Raoul in the London production?

Which actor in The Phantom of the Opera received the Laurence Olivier Award for best actor in a musical?

When did The Phantom of the Opera open on Broadway?

How many Tonys did the Broadway version win?

True or False: The Phantom of the Opera is the longest running show on Broadway.

Phantom of the Opera is based on a novel. What year was it written?

Le Fantôme de l’Opéra by Gaston Leroux was written in 1911.

(Brewer’s Dictionary of Modern Phrase & Fable)

According to the novel, what is the phantom’s real name?

Erik. The phantom’s story in the novel is the same as in the musical; he is a man with a hideous skull-like face who lives in seclusion beneath a Paris opera house.

(Brewer’s Dictionary of Modern Phrase & Fable)

Who were the original actors for the characters of Phantom, Christine Daaé, and Raoul in the London production?

Phantom — Michael Crawford

Christine — Sarah Brightman (Andrew Lloyd Webber’s wife at the time)

Raoul — Steve Barton

(The Oxford Companion to the American Musical)

Which actor in The Phantom of the Opera received the Laurence Olivier Award for best actor in a musical?

Michael Crawford. He also had a UK Top 10 hit with “The Music Of The Night.”

(Encyclopedia of Popular Music)

When did The Phantom of the Opera open on Broadway?

It opened in the Majestic Theatre on 26 January 1988. Michael Crawford, Sarah Brightman, and Steve Barton reprised their roles in this production.

(Encyclopedia of Popular Music)

How many Tonys did the Broadway version win?

Seven: Best Musical, Actor (Michael Crawford), Featured Actress (Judy Kaye), Sets, Costumes, Lighting, and Director (Harold Prince).

(Encyclopedia of Popular Music)

True or False: The Phantom of the Opera is the longest running show on Broadway.

True. It passed Cats (another Andrew Lloyd Webber show) on 9 January 2006.

(Encyclopedia of Popular Music)

As a bonus, check out our Spotify playlist of The Phantom of the Opera songs from both the original London production and the 2004 movie. Do you have a favorite version? What’s your favorite song? Leave your thoughts in the comments.

All the answers to this quiz are sourced from Oxford Reference .

Alyssa Bender joined Oxford University Press as a marketing assistant in July 2011. She works on academic/trade history, literature, and music titles, and tweets @OUPMusic. Read her previous blog posts.

Oxford Reference is the home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing, bringing together over 2 million entries, many of which are illustrated, into a single cross-searchable resource. Newly relaunched with a brand new look and feel, and specifically designed to meet the needs and expectations of reference users, Oxford Reference provides quality, up-to-date reference content at the click of a button. Made up of two main collections, both fully integrated and cross-searchable, Oxford Reference couples Oxford’s trusted A-Z reference material with an intuitive design to deliver a discoverable, up-to-date, and expanding reference resource.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Her Majesty’s Theatre – The Phantom of the Opera. Photo by ZeroJanvier, 2005. Released to public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

October 8, 2012

Canadian Thanksgiving

Americans, think fast: pause those (no doubt) raucous Columbus Day festivities and tilt an ear to the north. Sounds from beyond the 45th parallel should emerge. These may include Molson-fueled merriment and the windswept yawning of those huge CFL end zones. That’s right, it’s Canadian Thanksgiving! Yeah, they have one too.

It’s pretty much like ours, only on the first Monday of October, presumably because gravy freezes up there in late November. Born of the same pagan-turned-Christian impulse to commemorate another death-stalling harvest, Thanksgiving in both the United States and Canada got serious during the sanctimonious back half of the nineteenth century. The US made things official in 1863, when Abraham Lincoln created a federal holiday in gratitude for “fruitful fields” and to atone for American “perverseness and disobedience”; Canadians took their first steps in 1872, giving thanks to God when the Prince of Wales got better from typhoid fever. These pious urges, however, have gone the way of whalebone corsets. Now stripped of religious significance, Thanksgiving is just another commercialized red-letter day on North America’s non-liturgical calendar.

Trying to differentiate between today’s Canadian and American holidays gets silly fast. In the short film “Crappy Canadian Thanksgiving”, for instance, actress Ellen Page (the pride of Halifax, Nova Scotia) seems destined to spend her holiday in the US among unknowing neighbors, quietly reading a Canadian translation of Twilight. But American friends come to the rescue with an “authentic” Thanksgiving complete with Canadian Club whiskey (under the influence of which Ellen says R-rated things about — gasp — Céline Dion), poutine, flipper pie, and maple syrup. Turns out, though, that the Americans cook and eat Ellen, declaring her tastier than last year’s rack of Martin Short.

The underlying jokes here are the absurdity of (a) distinctions between American and Canadian Thanksgiving, and (b) the idea that Americans would want to consume a nice Canadian. Continental sameness and good feelings reign now, but it wasn’t always the case.

Before there was Canada there was New France, and before there was New France there was Acadia, whose first settlers had some pretty wild Thanksgivings. In the late summer of 1606, a group of Frenchmen sailed up the Bay of Fundy and planted a little colony called Port Royal on the western shore of present-day Nova Scotia. Led by a would-be fur trade baron, the sieur de Poutrincourt, and the future founder of Québec, Samuel de Champlain, the French soon realized how nasty the winter was going to be. So melding their own harvest traditions with those of the local Mi’kmaq (whose “banquets” featured piles of meat, lots of smoking, and tall tales), the French founded l’ordre du bon-temps, or the Order of Good Cheer.

Beginning that November, members of the order took turns hosting Thanksgiving parties complete with music, plays, wine, fish, and game. Not to stereotype, but moose pâté and beaver tail were apparently favorites. Membertou, the bearded sagamore of the Mi’kmaq, had a place at the table, as did the heads of other clans who brought plenty of goodies to the events. Indeed, the natives “ate and drank like us,” reported one French observer: “We took pleasure in seeing them, and their absence caused us sadness.”

I like to think that the party-people reputation earned by the Order of Good Cheer had something to do with the first “American” Thanksgiving. When Puritans landed at Plymouth in 1620, the nearby Wampanoag wanted nothing to do with them. English slave-raiders had lately been active around Cape Cod, spreading disease and ill-will. When contact became unavoidable, the Wampanoag chief Massasoit talked an Abenaki visitor named Samoset into breaking the ice. Abenaki country stretched from New England to the Maritimes, so Samoset’s people were familiar with the French in Acadia, and knew English traders on the Maine coast too. So he stripped down, painted up, and walked into Plymouth, welcoming the pilgrims in their own tongue. Perhaps hoping for some French-style Good Cheer, Samoset then asked for a beer.

The next year, the Puritans held a Thanksgiving feast to celebrate their survival and to mark a treaty with the Wampanoag. It wasn’t so different from the parties Poutrincourt and Champlain held at Port Royal: natives and Europeans sat around and ate.

But from a common starting point, the French and English took different paths. The 20,000 or so migrants to the Massachusetts-Bay Colony in the 1630s demanded land, which drove the Puritans into conflict with just about all of New England’s Indians. Fewer in number, the French in Acadia and the Saint Lawrence Valley were more cautious. Everywhere they went, they built alliances with natives who helped them sustain the fur trade and fight the English. Not that they loved all Indians; ask the Iroquois or the Fox, pounded by French-led attacks for much of the seventeenth century. But the intercultural links were so enduring that the Puritans saw little distinction between “French and Indian Demoniacks.”

Through it all, Thanksgivings continued. Geopolitics, however, turned them cruel. The French in Canada celebrated Louis XIV’s European wars and native-aided victories against English colonists. In Massachusetts, Thanksgiving was folded into a calendar of religious holidays turned-royal pep rallies. By the 1690s, Cotton Mather, the ne plus ultra of Bostonian priggishness, styled Frenchmen “the worst of Harpys.” In 1760, when Montréal fell to the British, a New England minister reminded his Thanksgiving congregation that it was hardly “sinful to rejoice in the Ruin and Downfall of an unreasonable and implacable enemy.” “Tis’ our Duty,” he proclaimed, “to praise GOD when we are able to set our feet upon their necks.” These guys might not have eaten Ellen Page, but they’d have been happy to see her go.

Our dull, undifferentiated North American Thanksgivings, then, hearken back to a time when early Canadians, New Englanders, and native Americans were grateful for each other’s deaths. So tonight, I’m embracing the modern. I’ll try to get my hands on some caribou jerky and flip between Roughriders vs. Alouettes and Texans vs. Jets. And thankfully, I’ll do it in peace.

Christopher Hodson is Assistant Professor of History at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. He is the author of The Acadian Diaspora: An Eighteenth-Century History.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

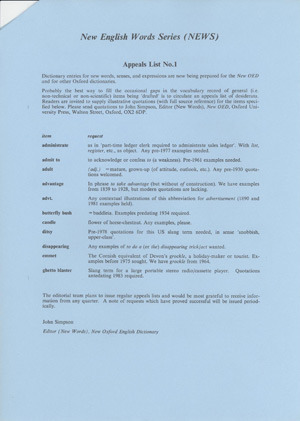

The history of the OED Appeals

The efforts of members of the public have been at the heart of the Oxford English Dictionary for over 150 years. The Dictionary couldn’t have been written without these contributions. We are calling on language lovers everywhere to help us trace the history of words whose origins are shrouded in mystery, with a brand new Appeals area of OED.com.

The OED’s record of appealing to the public for assistance stretches back to its very beginnings—to a time when the project not only had nothing to do with Oxford, but wasn’t even a dictionary.

The very first public appeal

The very first appeal to the public was made by The Philological Society in 1857.

The image above is the first formalized appeal from 1858 included in the ‘Proposal for the Publication of a New English Dictionary’. The society states “the public as well as members of the society were invited to take part in the work”.

They asked for volunteers to undertake to read particular books and copy out quotations illustrating ‘unregistered’ words and meanings — items not recorded in other dictionaries — that could be included in the proposed supplement. Several dozen volunteers came forward, and the quotations began to pour in.

Appeal for American Readers

In August 1859 the first American to become seriously involved with the project, George P. Marsh, issued another appeal for assistance, this time directed specifically at Americans. Marsh’s appeal informed his fellow countrymen that ‘the entire body of English literature belonging to the eighteenth century has been reserved for their perusal’ — on the basis that texts from earlier periods were rather harder to get hold of outside Britain.

James Murray’s new army of volunteers

In the spring of 1879 Oxford University Press undertook publication of the Dictionary with a new Editor, James Murray. He immediately realized that an army of volunteers had to be recruited, and within weeks of his appointment had issued ‘An Appeal to the English-Speaking and English-Reading Public’. Copies of the new appeal were sent to all corners of the globe, and new readers began to come forward in their hundreds, and eventually thousands.

Once again an American was persuaded to take on the task of co-ordinating the work of his compatriots; this time it was the distinguished philologist Francis March, of Lafayette College in Pennsylvania, who played an active part in the work of the Dictionary over the next thirty years.

James Murray and his ‘list of wants’

Once he began to compile actual Dictionary entries, James Murray realized that more specific help was needed. Even after the efforts of all of the voluntary readers he was sure that earlier, or later, examples of a word could be found than those which had been collected so far.

Accordingly, he wrote to the journal Notes and Queries, asking its readers to seek out quotations for nearly sixty words in the range abacist to abnormous. Soon other journals were reprinting the words on these lists—generally referred to by James Murray as his ‘lists of wants’ or ‘desiderata’—and inviting their readers to join in the hunt for quotations.

Example slips

Taken from the June 1879 appeal, this slip shows an example of a quotation submission and instructions for referencing and recording the source. After being submitted to Oxford, each quotation was written out on a small (6×4 inch) index slip, with a reference included to explain the source of the quotation. These slips were filed alphabetically according to the word noted by the reader, to be used by OED lexicographers as they proceeded to compile the Dictionary.

Taken from the June 1879 appeal, this slip shows an example of a quotation submission and instructions for referencing and recording the source. After being submitted to Oxford, each quotation was written out on a small (6×4 inch) index slip, with a reference included to explain the source of the quotation. These slips were filed alphabetically according to the word noted by the reader, to be used by OED lexicographers as they proceeded to compile the Dictionary.

Murray’s programme provided the vast majority of the quotations which appeared in the 1928 edition of the OED. After this publication, a lot of quotation evidence remained unused, so the OED editors decided to publish a single-volume Supplement. This supplementary volume was published in 1933, along with a reissued edition of the Dictionary.

Even after publication of the Supplement there were still about 140,000 quotation slips left over. These quotation slips were put into storage or donated to other historical dictionary projects, such as a project for a dictionary of Middle English in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

A new editor and the London Times

The 1933 Supplement remained the last word, as far as the OED was concerned, until the 1950s, when OUP decided that it was time to prepare a revised and expanded edition—not of the whole Dictionary, but of the Supplement.

The 1933 Supplement remained the last word, as far as the OED was concerned, until the 1950s, when OUP decided that it was time to prepare a revised and expanded edition—not of the whole Dictionary, but of the Supplement.

Once again, one of the first actions of the new Editor, Robert Burchfield, was to issue a leaflet appealing to the public to help with the collection of evidence; and once again lists of ‘desiderata’ began to appear, first as supplements to the Periodical and then in the pages of Notes and Queries.

Versions of these lists also began to appear elsewhere: the Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society, for example, asked its readers to look out for various aeronautical terms, and for several years the London Times adopted a policy of featuring selected words from the lists from time to time, which in some cases generated a lively correspondence, and often some useful antedatings.

For example, in the summer of 1960, a report that no examples of the expression mud in your eye had so far been found earlier than 1940 was followed a few days later by a letter providing an example from 1927.This is still the earliest known example of mud in your eye.

The second edition continues the appeals

In 1986, the next stage in the development of the OED was under way: the creation of the second edition of the Dictionary, in which the text of the first edition was to be combined with that of the Supplement, together with several thousand additional new entries.

The editing of this new batch of new entries was entrusted to John Simpson, who once again published ‘Appeals Lists’ asking for help with particular words, initially in the New OED Newsletter and then further afield.

balderdash and piffle

In 2005 the OED linked up with the BBC for another kind of appeal to the public. The Wordhunt asked BBC television viewers — and users of various websites — for help in finding earlier examples of a selection of 50 words and phrases; and the results were presented the following year in the television seriesBalderdash & Piffle.

The project generated considerable public interest, and some significant antedatings were found, several of them from distinctly unconventional sources, which are now quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary.

The project generated considerable public interest, and some significant antedatings were found, several of them from distinctly unconventional sources, which are now quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary.

The oED appeals today

Your Dictionary needs you!

Your Dictionary needs you!

At present the Dictionary is undergoing its first thorough revision and update. Around 70 editors, mostly in Oxford and New York, review each word in turn, examining its meaning and history, noting where meanings have changed — or where old definitions no longer suffice — and recraft the entries in the light of the most up-to-date information. The result is the current online edition of the Dictionary (in progress).

OED editor Katherine Connor Martin said, “The OED’s record of the history of English has relied on input from the public since before crowdsourcing was even a word. James Murray launched an Appeal to the public as far back as 1879, and the OED Appeals continues this long tradition of asking the public for help in our quest to record the origins of our vast, fantastic, ever-changing lexicon. After all, when it comes to the words we read, write, speak, and hear each day, every one of us is an expert.”

We are calling on language lovers everywhere to help us trace the history of words whose origins are shrouded in mystery. Could you hold the key to unlocking some of these language conundrums?

Puzzles include:

Was a ‘disco’ a dress before it was a nightclub?

When did the phrase ‘blue-arsed fly’ first appear?

If you can help, visit: www.oed.com/appeals.

This article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language. It is an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and pronunciation of 600,000 words— past and present—from across the English-speaking world. As a historical dictionary, the OED is very different from those of current English, in which the focus is on present-day meanings. You’ll still find these in the OED, but you’ll also find the history of individual words, and of the language—traced through 3 million quotations, from classic literature and specialist periodicals to films scripts and cookery books. The OED started life more than 150 years ago. Today, the dictionary is in the process of its first major revision. Updates revise and extend the OED at regular intervals, each time subtly adjusting our image of the English language.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images courtesy of Oxford University Press Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

John Lilburne, footwear, fame, and radical history

Forrest Gump’s momma famously told him that you could tell a lot about a person from their shoes. Footwear features prominently in two images of the Leveller leader John Lilburne, with both the seventeenth- and the nineteenth-century prints depicting Lilburne wearing striking leather boots. The Sunderland museum also holds a pair of boots once said to have belonged to Lilburne, though these appear to be of a rather plainer design than those that were so lovingly rendered in his 1649 trial portrait.

John Lilburne's boots, Sunderland Museums & Winter Gardens, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums. twmuseums.org.uk/sunderland

Frontispiece to Theodorus Verax (Clement Walker), The Triall of Lieut. Collonell John Lilburne (1649) British Museum AN514450001, © The Trustees of the British Museum

I included an image of these boots in a ‘guess the seventeenth century-radical’ quiz for my third-year students. Tellingly, it was the only picture that everyone identified correctly. The importance of image and personality to Lilburne’s survival in the public memory has been noted by the historian Mike Braddick. Indeed, Braddick has dubbed Lilburne ‘the celebrity radical’, seeing him as a figure whose political style provided a template for later radical figures such as John Wilkes.

Lilburne is now probably the best-known of all seventeenth-century radicals, featuring in television dramas (Channel 4’s The Devil’s Whore) and even inspiring a rock opera (Rev Hammer’s Freeborn John). However, it’s generally accepted that historical and public interest in Lilburne and the Levellers is relatively recent phenomenon, going back no further than the late nineteenth century. Then the Levellers came to be a subject for serious historical investigation through a combination of archival discoveries (the Clarke papers that contained the text of the Putney Debates) and, more importantly, the writings of liberal, socialist and Marxist scholars who saw in the Levellers either their intellectual ancestors or the agents of bourgeois revolution.

Blair Worden, whose Roundhead Reputations (2001) brilliantly traces these historiographical developments, has noted that Lilburne was alone amongst Leveller writers in receiving some public attention in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. However, according to Worden, these representations of Lilburne largely separated him from the Leveller movement and instead re-imagined him as a proto-‘Patriot’ figure.

Yet, in researching Lilburne’s eighteenth-century reputation, it became clear that both his connections to the Levellers and the details of his biography were better known than had previously been thought. Some of these eighteenth-century representations were surprisingly accurate, based on close-reading of Lilburne’s pamphlets (still the main source for biographical information on him.)

Lilburne’s life story had a tangible impact on eighteenth-century society. In his 1649 trial, Lilburne had successfully convinced the jury that they were ‘judges of law as well as fact’. This radical reinterpretation of the role of the jury was taken up by Charles James Fox in a speech laying the groundwork for the 1792 Libel Act, also known as Fox’s Act. This law, which remains in force today, expanded the role of juries in trials for libel, permitting them to give a ‘general verdict on the whole matter put in issue.’

By this point, Lilburne’s remarks in his 1649 trial had already become a rallying-point for eighteenth-century advocates of the ‘pro-jury’ position, like Lilburne’s biographer Joseph Towers. Much more unexpected for me was discovering the impact that Lilburne had on the eighteenth-century debate over slavery. The verdict in Somerset’s case of 1772 was widely seen as rendering slavery incompatible with English law. The defence lawyer Francis Hargrave employed an obscure sixteenth-century legal precedent, Cartwright’s Case, to argue that slavery had no standing in English common law. His only source for this precedent though was a reference in a seventeenth-century commentary upon the Star Chamber proceedings against John Lilburne in 1637-8. Lilburne’s idea of the ‘freeborn Englishman’ had been dramatically extended in its scope.

Lilburne’s eighteenth-century afterlife suggests that there was a greater affinity between seventeenth and eighteenth-century radicalism than is usually acknowledged. There were, of course, differences but the causes in which Lilburne was invoked (freedom of the press, the importance of the jury system, and individual liberty) were all ones that were central to his own political philosophy. Many historians are understandably wary of the idea of a single, unbroken ‘radical tradition’. But this does not mean we should ignore the intellectual influence of the English revolution upon the eighteenth century or the importance of charismatic figures such as Lilburne to later generations of radicals.

Ted Vallance is Reader in Early Modern History at the University of Roehampton and has previously taught at the universities of Sheffield, Manchester and Liverpool. He is the author of “Reborn John?: the Eighteenth-century Afterlife of John Lilburne” in the latest issue of History Workshop Journal (available for free for a limited time), A Radical History of Britain (2009), The Glorious Revolution (2006), and Revolutionary England and the National Covenant (2005).

Since its launch in 1976, History Workshop Journal has become one of the world’s leading historical journals. Through incisive scholarship and imaginative presentation it brings past and present into dialogue, engaging readers inside and outside universities. HWJ publishes a wide variety of essays, reports and reviews, ranging from literary to economic subjects, local history to geopolitical analyses.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers