Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1011

October 24, 2012

Is the George Washington Bridge a work of art?

Happy 81st Birthday, George Washington Bridge! The French architect Le Corbusier reportedly said you are “the most beautiful bridge in the world” – you “gleam in the sky like a reversed arch.” But are you really a work of art?

"George Washington Bridge. New York City." By Arthur Rothstein, 1941. From the Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection at The Library of Congress.

The designer Othmar H. Ammann certainly was conscious of the need to make beautiful bridges. In 1958 he wrote: “Economics and utility are not the engineer’s only concerns. He must temper his practicality with aesthetic sensitivity. His structures should please the eye. In fact, an engineer designing a bridge is justified in making a more expensive design for beauty’s sake alone.”

Apart from its obvious elegance, I think that the George Washington Bridge (GWB) is notable perhaps for four reasons. First, at 3,500 feet it was nearly twice the span of the longest bridge at the time — the Ambassador Bridge at 1,850 feet. Second, Ammann was able to make huge cost savings by reducing the estimates of live load (i.e. due to traffic and trucks etc.) and relying on a relatively new so called ‘deflection theory’ to design the bridge. Third, the bridge was built during the Great Depression, but there wasn’t enough money — a cause of a change in appearance because the now famous steel towers were due to be faced in concrete and stone. Fourth, Ammann designed the bridge so that it could be added to, though that didn’t come about until 1962. With its 14 lanes of traffic it is now one of the busiest bridges in the world.

Given later events such as the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge — the famous ‘galloping Gertie’ which Ammann actually investigated — one could argue that Ammann’s design was ‘brave’. Large changes from what has gone before, as at Tacoma, can be challenging. It is interesting therefore that as a young man Ammann made his name early by writing a report on another famous bridge disaster — the Quebec Bridge that collapsed during construction in 1907. At the time the Quebec Bridge was also to be a very large span at 1800 feet, rivalled only by the Forth Railway Bridge in Scotland with main spans of 1710 feet and built in 1890. Ammann would have seen and learned how the many errors in the design and execution led to the downfall of Quebec. He would have contrasted that experience so strongly with the way Sir Benjamin Baker and Sir John Fowler took meticulous care with the Forth after they had witnessed the collapse of the Tay Bridge in Scotland in 1879. I suspect that he learned much from those experiences.

Suspension bridges are complex because the flow of forces in the structure is not easily calculated; engineers call them statically indeterminate. Only now with large computers can we model their behaviour with any confidence. Ammann was taught in Zurich at ETH by Wilhelm Ritter, the engineer who laid the basis for the new, but still rather approximate, deflection theory in 1877. Indeed Ritter taught arguably two of the greatest bridge designers of the early 20th century, Ammann and Robert Maillart, who was responsible for some beautifully elegant early reinforced concrete bridges in Switzerland including the world famous Salginatobel Bridge near Schiers. Ritter’s influence on two of his most accomplished pupils is clear in their work. Ritter emphasised the importance of visualising the flow of forces in the bridge and its relationship with aesthetics. Josef Melan improved the new deflection theory in 1888 and Leon Moisseiff used it to design the Manhattan Suspension Bridge in 1908. The theory was so-named because it took account of the deflections of the structure under live loads (i.e. the moving traffic, etc.). Moisseiff was confident that the theory was accurate but he later was to design Tacoma Narrows.

Perhaps Ammann was more aware of its limitations than some commentators, such as Henry Petroski, have intimated. He knew that the theory was based on quite severe simplifying assumptions. Darl Rastofer has written that Ammann was a reserved, self-effacing, and meticulous man, but one with a quiet inner confidence that meant he could hold his own. He was as comfortable at dealing with detail as well as taking an overview. Like others before him such as Thomas Telford at Menai Bridge in North Wales, Baker and Fowler at Forth, Ammann used theory. But unlike Theodore Cooper at Quebec and Sir Thomas Bouch at Tay, perhaps he was very careful to check and control the detail. I suspect that he was diligent in making sure he understood the flow of forces even if he knew he couldn’t calculate them precisely. I suspect that is why he went on to be so successful in leaving his mark on New York City with five major bridges that bear so much of the traffic flow to and from the city, and with his help on the high profile Golden Gate in San Francisco.

General view of North Side of Bridge from NJ Side of River. From the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

So is the GWB a work of art? Art is difficult to define but we can say it is a power of the practical intellect, the ability to make something of more than ordinary significance. Is the GWB an extraordinary bridge? Did Ammann achieve aesthetic sensitivity? He certainly achieved practicality; no-one can fail to be impressed. Le Corbusier liked it, so that is good enough for most of us. But of course Le Corbusier was a modernist, so he liked functionality; for example he saw buildings ‘as machines for living in’. All in all I think it is no accident that suspension bridges are some of the most beautiful structures we see around us. The graceful curves of the cables are the defining feature and they are entirely natural structures. They are the best examples of harmonious form and function. The GWB is one of the best as was Othmar Ammann.

Emeritus Professor David Blockley is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Bristol, UK. He has won several awards including the Telford Gold Medal of the Institution of Civil Engineers. He has written over 160 technical papers and 7 books – the latest of which are Bridges: The Science and Art of the World’s Most Inspiring Structures and Engineering: A Very Short Introduction. Read his previous blog post: “The ingenious problem-solving of the modern-day engineer.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Armed conflict: using unmanned aerial vehicles

Class I unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) of the US Army

During the ten years since an unmanned aerial vehicle, or UAV, was used to target Qaed Senyan al-Harthi in Yemen in 2002, attack of ground targets from unmanned platforms in the air has gone from a novelty to mainstream. The United States sees such technology as a vital element in its fight against international terrorism, and such military operations are routinely conducted from the airspace above Afghanistan, Pakistan and elsewhere. The aircraft are unmanned in the sense that instead of having a pilot on board, a UAV operator, to whom information is fed from sensors aboard the vehicle and from other sources, steers the vehicle and controls its use of the weapons it carries. He will do this from a ground station which may be located nearby or far from the scene of the resulting violence, even in a different continent.

These operations arouse controversy at a number of levels. At the time of writing, former international cricketer turned senior Pakistani politician Imran Khan and his supporters are undertaking a protest march against US drone (as some insist on inaccurately labeling them) strikes in that country. In the minds of many, this use of UAVs is inextricably linked with notions of targeted killing, a subject which Nils Melzer has discussed in depth in his scholarly work and which has been the subject of extensive legal, human rights and political debate.

And yet, when employed in the course of an armed conflict, there are no particularly novel issues raised by UAV operations to attack ground targets. The established customary rules that bind all States, irrespective of which treaties they may have adopted, apply equally to attack operations using UAV technology. So the UAV operator who steers and controls weapons release, the ‘man in the loop’ as the jargon goes, must comply with important rules. He or she must maintain a distinction at all times between combatants (principally members of the armed forces) and civilians who do not participate directly in the hostilities, and between military objectives and civilian objects, making only combatants, directly participating civilians, and military objectives the object of attack. He or she must only undertake attacks that discriminate appropriately between these classes of person and object because a specific rule prohibits indiscriminate attacks. He or she must not attack persons and objects entitled at law to special protection and must take the precautions the law requires as a means of seeking to ensure that these rules are not breached.

It is these precautionary requirements that will be in the forefront of a UAV operator’s mind. He must, in very general terms, take constant care to spare civilians and civilian objects, must do all he can to verify that it is lawful to attack the target (for example, that the combatant has not been rendered hors de combat, or out of the fight, due to wounds or sickness), must do all he can to check that his chosen method of attack minimizes dangers to civilians and civilian objects, and must refrain from or cancel attacks that may be expected to cause injury or damage to civilians or civilian objects that would be excessive in relation to the anticipated military advantage from the attack.

But these are the same rules as a pilot of a manned aircraft must comply with and the data made available to the UAV operator is likely to be similar to that which a pilot would receive, so there do not seem to be any unique legal issues raised by these ‘man in the loop’ operations.

[image error]

MQ-1B Predator unmanned aircraft

Now go one stage further in the direction in which technological advance seems to be leading us, namely towards autonomous attacks. Here we dispense with the UAV operator, or at least we take him out of ‘the loop’. The unmanned platform, which may be an aircraft, a land vehicle or a marine craft, may navigate itself autonomously, but that is not the legally interesting aspect. Rather, it is when the machine is designed to decide which targets to attack and how to undertake the attack that important legal issues start to arise. The sensors on the platform may well enable it to differentiate between, say, a civilian truck and an artillery piece or a tank, and having recognized the military vehicle, to attack it.

But how can a machine determine that the attack will be discriminate, that the collateral damage to be expected is not excessive in relation to the anticipated military advantage, and how can the machine differentiate between, for example, an able-bodied combatant whom it is lawful to attack and a combatant who is hors de combat and the attack of whom would be unlawful?

All States that develop or acquire new weapons must consider whether their use would in some circumstances at least breach the law applying to the relevant State. It follows that the existing rules of distinction, discrimination, precautions, and proportionality to which we referred earlier will have to be applied to any future plans to develop autonomous attack technologies. Only if the technology is compatible with compliance with those rules should it be fielded and used.

But irrespective of what the law may say, is a process that removes people entirely from direct involvement consistent with our view of what war ought to be all about? If Homer considered fighting at a distance to be unheroic and therefore unacceptable, is wholesale delegation of attack decision-making to machines what we want to see? It may not be war as we know it, Jim, but is it war as we want to see it? The cynic in me suspects the answer is yes, provided ‘we’ benefit, however temporarily.

Bill Boothby is the former Deputy Director of Legal Services for the Royal Air Force. He is currently engaged as a member of the core group of international law experts preparing a Manual on the International Law of Cyber Warfare and also published Weapons and the Law of Armed Conflict (OUP, 2009).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credits:

XM156 Class I UAV of the US Army. By US Army [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

An MQ-1B Predator unmanned aircraft from the 361st Expeditionary Reconnaissance Squadron takes off July 9 from Ali Base, Iraq, in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. By Tech. Sgt. Sabrina Johnson [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

October 23, 2012

On the second presidential debate

The second presidential debate tells us about the candidates’ readings of their own campaigns. Both Romney and Obama were fighting for airtime, trying to break out of the impasse of “he-said-she-said.”

Women were mentioned about 30 times in the debate because Romney knew that he had to close the gender gap. Obama joined in on the China bashing because Romney has started to gain traction with workers in Ohio with his attacks on China’s trade violations.

Obama knew that he had to deflate the Libya story, so he took full responsibility for what happened in Benghazi, even though Secretary Clinton had given him an out. Obama’s taking offense at Romney’s charges wouldn’t have gained him any Republican converts, but undecided voters are usually willing to give the benefit of the doubt to the Commander-in-Chief because nobody has access to intelligence information the way the president does. The good news for Obama is that the next debate (on foreign policy) will shield him from his weakest link, the economy.

Where Romney will continue to have the benefit of the doubt is his proposed handling of the economy. His strongest moment in the second debate was when he pulled up statistics on the number of people unemployed, on food stamps, the size of the national debt, etc. This was Republican version of Bill Clinton’s “arithmetic” speech. Obama tried to characterize Romney’s economic plan as a “sketchy deal.” The problem is that he doesn’t exactly start off with a whole lot of credibility.

Emboldened by his last debate performance, Romney might have been too enthusiastic in the second debate. At times, he may have been snarkier than he should have been. Undecided voters, who already don’t like negativity, would not have liked Romney’s smack-down of Obama. (“That wasn’t a question; that was a statement.”)

Overall, Obama did much better in this debate than in the last, but he didn’t do enough to make up the ground he lost, in part because of the town hall format. A victory when a candidate is standing beside his opponent and sparring with him directly is more compelling than a (possible) victory when both are directing their comments to a small group of voters. The town hall format is just less interesting to watch, and I won’t be surprised that audiences were bored and channel-surfing during the second debate.

As far as the horse race goes, Obama still has more paths to 270. Romney is looking good in Florida, but Obama leads in Virginia and Ohio. The Romney team knows that their campaign needs to put Pennsylvania, Michigan, or Wisconsin in play in case they lose Ohio. Watch for a re-nationalized campaign strategy from Team Romney if they see movement in these previously leaning-Democrat states.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Changing evangelical responses to homosexuality

Although popular culture war depictions have often presented evangelical elites as intransigent in their opposition to homosexuality, authors of a new study published by Sociology of Religion find that during the last several decades, evangelical elites have actually been subtly but significantly changing their moral reasoning about homosexuality. Based on content analysis of the popular evangelical magazine Christianity Today, authors Jeremy N. Thomas and Daniel V. A. Olson identify the shifts that compose this change, and propose that various combinations of these shifts align with and map onto four overarching responses to homosexuality — biblical intolerance, natural intolerance, public accommodation, and personal accommodation. They suggest that the development of these responses demonstrates a trajectory of change that portends the increasing liberalization of evangelical elites’ positions and attitudes on public policy debates related to homosexuality. Thomas and Olson argue that these changing responses are largely the result of underlying shifts in the sources of moral authority to which evangelical elites have been appealing when making arguments about homosexuality.

The article “Evangelical Elites’ Changing Responses to Homosexuality 1960–2009” investigates how divergent views of moral authority have played into disagreements and debates about homosexuality, specifically from the perspective of evangelical Christians, a group that James Hunter, author of the controversial culture wars thesis, and many others have frequently identified as being one of the prime constituencies of cultural conservatism. In particular, the authors investigate how the moral reasoning of evangelical elites has been changing with regard to homosexuality during the 50-year period from 1960 to 2009. They seek to understand not only how evangelical elites have been shifting the sources of moral authority to which they have been appealing when making arguments about homosexuality, but also the corresponding shifts that have been occurring with regard to their assessments of the personal morality of homosexuality, and with regard to their positions and attitudes on public policy debates related to homosexuality.

Thomas and Olson believe that this investigation is important for at least three reasons. First, it helps clarify the history of one of the most contentious topics in American cultural life. Second, it challenges the culture wars thesis and potentially paints a new and perhaps counter intuitive picture of contemporary evangelical elites’ moral reasoning about homosexuality, which may, in turn, have significant implications for considerations of evangelicals’ civic and political engagement. Third, it identifies a key mechanism by which many generally conservative religious groups may find themselves subtly shifting toward more progressive positions and attitudes on a variety of public policy debates. As suggested throughout the article, when generally-conservative religious groups engage in public policy debates, they are often tempted to shift the sources of moral authority to which they appeal in order to make arguments that they believe others will find more convincing. However, once they grant legitimacy to these new sources of moral authority, such religious groups become increasingly subject to the possibility that competing interpretations of these new sources may be persuasively used to convince them to adopt more progressive positions and attitudes.

While evangelical elites have certainly not embraced this change, they have not been immune to it either. Instead the authors suggest that evangelical elites have been responding to America’s growing acceptance of homosexuality by subtly but significantly changing their moral reasoning. In particular, they observe three shifts. First, evangelical elites have not only been reducing the frequency of their appeals to biblical sources of moral authority when making arguments about homosexuality, but they have also regularly been making appeals to other less orthodox sources, particularly science, medicine, and the natural order. Second, evangelical elites have been reducing the frequency of their negative assessments of the personal morality of homosexuality. Third, although they remain largely committed to traditional positions on public policy debates related to homosexuality, a growing proportion of evangelical elites have been demonstrating more tolerant and/or pluralistic attitudes both toward popular depictions of these debates and toward gay persons on the other sides of these debates.

The authors go on to conclude that the connection between moral authority and public policy has significant implications for considerations of how other generally-conservative religious groups may find themselves responding to various cultural changes when they are located in and attempting to influence a surrounding culture that discounts the validity of orthodox sources of moral authority. Their research suggests that sociologists of religion should give further consideration to the ramifications of moral authority and especially to the ways that generally-conservative religious groups may be tempted to shift the sources of moral authority to which they appeal — and in doing so — may find themselves also shifting their positions and attitudes on a variety of public policy debates. The research further suggests that even though Hunter’s culture wars thesis has been largely and correctly discredited, his idea of explaining cultural conflict through underlying differences in moral authority remains an important insight and a powerful analytic tool. Although this investigation has been limited to evangelicals and homosexuality, the findings indicate that the workings of moral authority provide a key mechanism for interpreting and predicting a wide range of cultural conflicts and related cultural changes.

Scott Schieman is the Editor of Sociology of Religion and Professor of Sociology at the University of Toronto. Jeremy N. Thomas is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Idaho State University and Daniel V. A. Olson is Associate Professor of Sociology at Purdue University.

Sociology of Religion, the official journal of the Association for the Sociology of Religion, is published quarterly for the purpose of advancing scholarship in the sociological study of religion. The journal publishes original (not previously published) work of exceptional quality and interest without regard to substantive focus, theoretical orientation, or methodological approach.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

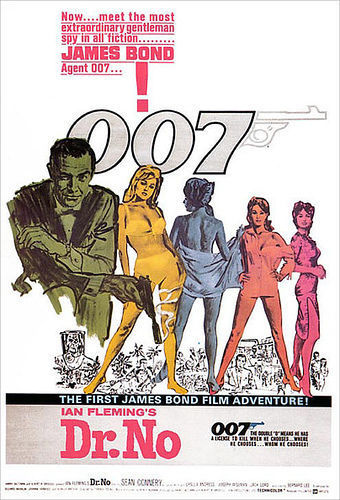

James Bond: the spy we love

Premiering today, 23 October 2012, Skyfall is the 23rd film in the highly successful James Bond film series. It has been 50 years since the release of the first Bond film, Dr. No, in 1962. Over the decades, there have been many Bond adventures and we have seen six different actors portraying the MI6 agent, as well as many Bond villains, and the famous Bond girls who don’t seem to be able to resist Bond’s charms. With roughly one new film coming out every two years over the past fifty years, generations all over the world have grown up with this quintessentially British export, who has repeatedly rescued the world from evil, including power-crazy media moguls, gold smugglers, and mad scientists. Like it or not, James Bond has become a British cultural institution and is probably the most famous fictional secret intelligence agent in history. To celebrate this achievement, let’s have a closer look at who James Bond is and what it is that makes him ‘Bond, James Bond’.

From paper to screen – James Bond in the making

Ian Fleming (1908 – 1964) created Bond as a fictional character in his famous spy novels. Before working as a writer and journalist, Fleming had himself served as a Naval Intelligence Officer in the Second World War and was involved in the planning of several operations, including ‘Operation Mincemeat’ and ‘Operation Golden Eye’. It’s rather obvious why only the latter was used as a title for one of the films in the Bond series. Fleming’s first Bond novel was Casino Royale, published in 1952, followed by another 11 Bond novels and two short story collections. Fleming, a keen birdwatcher, named his hero after the leading American ornithologist James Bond (1900-1989). Some sources cite Fleming as saying that he picked the name because it sounded particularly dull and boring, which is what he was looking for. True or not, James Bond has developed into more than just a name, and is now a brand in itself. Other authors later followed in Fleming’s footsteps and penned further Bond novels: Kingsley Amis (as Robert Markham), Christopher Wood, John Gardner, Raymond Benson, Sebastian Faulks, and Jeffery Deaver.

Originally using Fleming’s plots in full or in parts, the film franchise has had to develop its own material in the past years. The highly successful film series is produced by EON Productions, which was founded in 1961 by Albert Broccoli and Harry Saltzman and is still owned by the Broccoli family. It is based in London and operates from Pinewood Studios, where most of the indoor scenes for the Bond films are shot. Over the years, it has become increasingly difficult to finance the production of the lavish Bond films. The production of the new film Skyfall actually had to be put on hold for financial reasons, and filming could only be resumed after securing sponsorship deals with high-profile companies like the Dutch beer producer Heineken.

007

But who is this MI6 agent on Her Majesty’s secret service? Let’s start with his code name, 007. This indicates Bond’s status within the Secret Intelligence Service MI6. Like all the other 00 agents, Bond has the famous ‘licence to kill’ in the field as he sees fit – and anyone who has seen a Bond film knows that he makes ample use of this privilege. It is never revealed how many 00 agents exist in total, but several have been featured in the films, including 006 Alexander Trevelyan, featured in the 1995 film Goldeneye.

James Bond has been portrayed by six actors within the Bond film series. Sean Connery was the first to play 007 in the 1962 film Dr. No, returning to the screen as Bond five times (six times including the non-EON production Never Say Never Again). He is still considered by many to be the best Bond. George Lazenby, Australian actor and model, gave a one-off guest performance as Bond in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), and Roger Moore holds the record of starring as Bond seven times between 1973 and 1985. He was followed by Timothy Dalton (twice) and Irishman Pierce Brosnan, filling the role four times before Daniel Craig took over as Bond in 2006. Craig will play Bond for the third time in Skyfall. Every actor has given his own touch to the character, but the proverb ‘old habits die hard’ certainly holds true.

James Bond has been portrayed by six actors within the Bond film series. Sean Connery was the first to play 007 in the 1962 film Dr. No, returning to the screen as Bond five times (six times including the non-EON production Never Say Never Again). He is still considered by many to be the best Bond. George Lazenby, Australian actor and model, gave a one-off guest performance as Bond in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), and Roger Moore holds the record of starring as Bond seven times between 1973 and 1985. He was followed by Timothy Dalton (twice) and Irishman Pierce Brosnan, filling the role four times before Daniel Craig took over as Bond in 2006. Craig will play Bond for the third time in Skyfall. Every actor has given his own touch to the character, but the proverb ‘old habits die hard’ certainly holds true.

Bond wouldn’t be Bond without some constants within the series. One of the most famous lines in the Bond films and cinema history in general, is Bond’s introduction. When asked for his name, Bond’s usual response is a very cool and nonchalant ‘Bond, James Bond’. Connery uses this line for the first time in Dr. No, and it has been a characteristic feature of the series ever since. Apart from that, Bond is truly a man of pleasure, not only with respect to women, but also in terms of alcohol and cigarettes. ‘Shaken, not stirred’ is how he drinks his martini, and this line has developed into a catchphrase over the years. Sean Connery was the first Bond to utter the phrase on screen in Goldfinger (1964). Casino Royale stands as a notable exception to this: when asked whether he wants his martini shaken or stirred after having lost millions in a poker game, Bond sulkily snaps at the waiter ‘Do I look like I give a damn?’.

Being the adrenaline junkie that he is, Bond has made cars into a stylish accessory. This is of course helped by the fact that his cars come with various clever modifications like state-of-the-art weapons and anti-pursuit systems. It seems that a suave secret agent like Bond needs to travel in style. Thus, Bond has driven many fashionable cars, including brands like Aston Martin, Bentley, Lotus, Rolls-Royce, and BMW. Other more unusual modes of transport featured in the Bond films include a moon buggy (Diamonds are Forever, 1971), various motorcycles, a space capsule (You Only Live Twice, 1967), a space shuttle (Moonraker, 1979), a hot air balloon (Octopussy, 1983), submarines (You Only Live Twice, 1967; The Spy Who Loved Me, 1977), and an alligator boat (Octopussy, 1983). All of these are of course highly instrumental in the famous battles between Bond and the villains.

One of the perks of Bond’s dangerous and life-threatening job is that he gets to travel. Bond is a true globetrotter and he has taken us on adventures to all parts of the world. Ranging from the ordinary to the exotic, featured locations include Jamaica, Turkey, Mexico, Egypt, Lebanon, Italy, Brazil, Morocco, Pakistan, Russia, China, Vietnam, North Korea, South Korea, Cuba, Uganda, Madagascar, and Bolivia. But, naturally, the world is not enough; in Moonraker Bond even travels to outer space to rescue the world from evil.

‘I expect you to die’

Speaking of evil, every heroic spy needs an evil antagonist and James Bond has certainly fought plenty of them. After all, a good villain is just as important as a good Bond. Memorable villains include Dr. Julius No, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, Auric Goldfinger, Francisco Scaramanga, fellow MI6-agent-turned-villain Alec Trevelyan, and LeChiffre. Some of them are power-crazy, others just crazy, and yet others are just pure evil.

In terms of the missions Bond is being sent on, it is notable that every Bond film is very much a product of its time and a reflection of the political, historical, and cultural events of a certain period. Thus, earlier films are set during the Cold War and the plots often revolve around topics such as the space race between the US and the USSR or nuclear weapons/bombs. Other themes include gold and diamond smuggling, drug trafficking, deadly viruses, opium trade, and more generally the manipulation of world politics.

Bond’s interference with their evil plans, makes him the villains’ number one target, but Bond wouldn’t be Bond if he didn’t manage to rid the world of all the Goldfingers, Blofelds, and LeChiffres out there. Over the years, we have seen action-filled fights and stunts, usually ending in defeat for the villains. And let’s not forget that – to add momentum – villains need to be disposed of in a spectacular fashion. Accordingly, Goldfinger (Goldfinger) gets sucked out of a depressurising plane, Dr. Kananga (Live and Let Die) inflates and explodes after Bond forces a compressed gas capsule down his throat, Hugo Drax (Moonraker) is ejected into outer space, Max Zorin (A View to A Kill) plummets from the top of the Golden Gate Bridge, and Renard (The World Is Not Enough) is impaled by a plutonium rod.

‘Oh James’

Killing naughty villains isn’t Bond’s only speciality; he is also very well-versed in the seduction of women. His rather promiscuous lifestyle and general attitude towards the female sex have often met with criticism. ‘Sensitive’ and ‘respectful’ are not adjectives that come to mind. Bond girls are typically young, thin, and beautiful, and, whereas they may try to resist Bond, they eventually give into the temptation and fall prey to the rogue charms of the strong, attractive, and apparently irresistible secret agent. Although often independent and intelligent women with a (criminal) career on their own, they have repeatedly been turned into sex objects. This isn’t helped by the fact that some of them have rather suggestive names, such as Pussy Galore or Plenty O’Toole.

You could even say that Bond is the epitome of a man with commitment issues. He only falls in love twice within the whole film series. Thus, he gets married to Countess Tracy de Vicenzo in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, but his wife is killed shortly after, conveniently freeing him for the next non-committal affair. In Casino Royale, Bond even gives up his work at MI6 to be with his girlfriend Vesper Lynd, only to find that she’s betrayed him. The only female constant in his life seems to be M’s secretary Moneypenny. Albeit flirtatious, her relationship with Bond is purely professional. With Judi Dench taking on the role of M in 2005, another female character has entered Bond’s on-screen life. Their relationship is somewhat ambiguous in that they seem to despise each other. She is the first and only female authority figure in Bond’s life and openly shows her hostility towards his attitude, calling him a ‘sexist, misogynist dinosaur; a relic of the Cold War’ (GoldenEye, 1995).

‘Got a Licence to Kill’

Almost as famous as the films themselves are the Bond theme songs. “The James Bond Theme”, composed by Monty Norman and first performed by John Barry, features in all the films, but famous artists have lent their voices to the opening credits of each Bond film. Welsh singer Shirley Bassey sang the theme songs for Goldfinger, Diamonds Are Forever, and Moonraker, Paul McCartney performed Live and Let Die, Duran Duran contributed A View to A Kill, and Nancy Sinatra performed You Only Live Twice. Other notable performers include Louis Armstrong (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service), A-ha (The Living Daylights), Tina Turner (GoldenEye), Garbage (The World Is Not Enough), and Madonna (Die Another Day). The theme song for Skyfall, recorded by Adele, was released on 5 October 2012 and is the highest charting James Bond theme song in the history of the UK Singles Chart.

The hype around the release of every new Bond film suggests that the film format still appeals to cinema-goers out there. It certainly is a franchise of superlatives being both one of the longest-running film series in history (50 years) and the second-highest-grossing film series behind Harry Potter (let’s just ignore the fact that there are significantly fewer Harry Potter films), with Casino Royale (2006) being the highest-grossing film of the series at $594 million. It remains to be seen, however, whether Skyfall will be able to meet expectations. Sorry Bond, but in this case we’d prefer to be stirred, not shaken.

Cornelia Haase is an Assistant Commissioning Editor for General Reference at Oxford University Press.

Oxford Reference is the home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing, bringing together over 2 million entries, many of which are illustrated, into a single cross-searchable resource. Newly relaunched with a brand new look and feel, and specifically designed to meet the needs and expectations of reference users, Oxford Reference provides quality, up-to-date reference content at the click of a button. Made up of two main collections, both fully integrated and cross-searchable, Oxford Reference couples Oxford’s trusted A-Z reference material with an intuitive design to deliver a discoverable, up-to-date, and expanding reference resource.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Skyfall movie poster from 007.com used for the purposes of illustration. (2) Dr. No movie poster used for purposes of illustration.

Sounds of the swing era

The sound of a big band in full flight must surely rank as one of the defining timbres of twentieth century music. It continues to be preserved by, among many others, Wynton Marsalis’ Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, remixed by DJs and artists like Matthew Herbert, re-popularised by stars including Michael Bublé, rejuvenated for a new teen audience by West Coast composer Gordon Goodwin (whose charts have become staple repertoire for high school bands), and represented on mainstream television shows such as Strictly Come Dancing and, until recently, X Factor. In all these guises and more, the big band sound continues to delight and sets toes tapping.

Return to recordings from the ‘golden age of swing’, however, and the hisses, pops and mono sound mean that performances from yesteryear can lack the appealing lustre of their modern counterparts. As my colleagues and I found out some years ago when undertaking a teaching and learning project, the sound quality of early jazz recordings was a significant barrier to our students’ engagement with the music. In his 1999 remastering of clarinettist and bandleader Benny Goodman’s Famous 1938 Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert, producer Phil Schaap embraces the full gamut of documented sounds from the musicians, audience and the recording process itself. In the liner notes he urges listeners that:

The greatest noise reduction device is your brain. Trust it to work with your ears to hear music that would otherwise have been excised if a computer did the work. This is the truth [Schaap, Liner notes to The Famous Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert, Columbia/Legacy C2k 65143 1999 : 38].

Schaap’s approach is the polar opposite to that of Bill Savory, who engineered the original 1950 LP release of the Goodman’s concert to present a ‘clean’ version of the material. Indeed, while Schaap was keen to include every sound captured on the master discs, Savory made edits in the interest of an aesthetically-pleasing end product. When faced with the choice between the two versions, most reviewers have concluded that it was desirable to own both: the original for the quality of the listening experience and the remaster as the ‘complete’ historical documentation of the live event. (On closer inspection the complete omission of different musical material from both versions further complicates the comparison.) Since 1999, other remasterings have offered a compromise between these two approaches. But whichever version we choose, recordings continue to leave us distant from the experience of ‘being there’ at the time of the event, particularly frustrating in the case of a ‘live’ (as opposed to studio) performance.

The most prolific live recordings from the swing era were made by enthusiastic amateurs from their radios. The popularity of this practice among fans has enabled D. Russell Connor to produce invaluable discographies of Benny Goodman which extend well beyond his studio work and allow the full scale of his career to be appreciated. Many of these ‘air checks’ are now commercially available which testifies to our continued desire to capture the ephemeral. But what do such recordings, often profoundly dissatisfying as sonic artefacts, have to offer beyond functioning as mere momentos providing some tangible grasp on the otherwise transient nature of musical performance?

Perhaps Schaap has a point. Embracing the imperfections of unedited live recordings and air checks provides perspective on the released studio recordings that are easy to view as definitive in retrospect, especially as they are often technologically superior. As with Connor’s discographical work, we can gain a better appreciation how particular moments of performance that were captured in the studio fit into the relentless everyday existence of a band at the height of the swing era. Through close analysis of series of performances it is possible to develop a deeper understanding of performance practice in its widest sense, including an appreciation of underlying processes such as rehearsal and the evolution of interpretation which remain largely undocumented in any other way.

In the case of a Goodman classic — Fletcher Henderson’s arrangement of Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies” — such analysis exposes the 1935 studio recording as a ‘safe’ rendering which was subsequently developed and refined. By 13 September 1938, when Goodman broadcast the number from the Congress Hotel in Chicago, “Blue Skies” had been comprehensively redefined as up-tempo swing. Jeffrey Magee has analysed this number in detail in his book , but on this broadcast Henderson joins Goodman and the band to perform his own analysis of a short section of the piece.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The band demonstrates the brass and saxophone parts from the beginning of the second chorus of “Blue Skies” separately and then together, to which the rhythm section is subsequently added. This is remarkably similar to trumpeter Chris Griffin’s description of Goodman’s rehearsal process:

First we’d run the chart down as a group, then the brass and reed sections would rehearse separately. Finally the two sections would rehearse the number together, over and over, without the rhythm section. None of the other leaders I worked with rehearsed a band in this way — without the drums, bass, guitar and piano. We had to keep time and make the tune swing by ourselves. Benny’s idea was that, in this way, the band would swing better and have a lighter feel. If you didn’t depend on the rhythm section to swing, you would swing that much more when the rhythm section finally was brought in. [Deffaa, Swing Legacy 1989 : 45–46]

There can be no clearer demonstration of the synergy between arranger and bandleader which was so vital to Goodman’s success. Indeed, as Goodman recalled in his autobiography, the introduction of Henderson’s arrangements demanded rapid development of the band’s performance style which was to prove formative.

It was one of the biggest kicks I’ve ever had in music to go through these scores and dig the music out of them, even in rehearsal. We still didn’t have the right band to play that kind of music, but it convinced me more than ever which way the band should head — and it was up to us to find the men who could really do a job on them. [Goodman and Kolodin, The Kingdom of Swing 1939 : 157]

The Henderson-Goodman partnership produced a defining sound of the swing era which continues to influence and inspire musicians. But even today there can be no substitute for live recordings to help us to understand this music as the soundtrack to an era for those fortunate enough to be present at the hotels and ballrooms where the Goodman band played, and equally, for those that tuned in and captured these moments for posterity.

Catherine Tackley is Senior Lecturer in Music at The Open University, UK. She is the author of Benny Goodman’s Famous 1938 Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert and The Evolution of Jazz in Britain, 1880-1935 (Ashgate, 2005), and is a co-editor of the Jazz Research Journal (Equinox). Catherine is Director of Dr Jazz and the Cheshire Cats Big Band.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

October 22, 2012

Should we want a business leader in the White House?

During the first two presidential debates, Governor Mitt Romney repeatedly invoked his business experience as a key qualification for the White House. He uttered phrases such as “I know how to make this economy grow” and “I know how to grow jobs” at least a half dozen times in his second debate with President Barack Obama. The notion that a business leader would bring to the presidency a uniquely useful skill set, especially in a period of sluggish economic growth, has a certain appeal.

[image error]

But we ought to look at the claim more critically. On the one side, Romney appears to be an effective manager, at least under certain circumstances. If he wins, he won’t be another George W. Bush. On the other side, some aspects of his managerial style should raise concerns about whether he can make very difficult decisions about the people around him. More than that, we need to ask how significant his business background and management style would be in a possible Romney administration.

Recent media analyses give us a good picture of Romney as a business person and as a manager. Peter Joseph, a longtime participant in private equity ventures, offers a close look at Romney’s role at Bain Capital and describes him as a financier who was very effective at securing a return for his investors. Still, Joseph worries “whether the time [Romney] spent in single-minded pursuit of profit as a financial intermediary has prepared him to tackle the complex problems facing America, which can’t be reduced to a financial model.” Fair enough, but one might question whether any career track really prepares a person to be president. Certainly Barack Obama had a thin resumé before he entered the Oval Office. When we add in Romney’s time as governor of Massachusetts, his record looks no worse than that of other recent presidents. As a business leader, moreover, he appears to have achieved a record far superior to that of George W. Bush, who was propped up by friends in the corporate world while he stumbled through the early phases of his political career.

Certain elements of Romney’s managerial approach also suggest he would not commit the kinds of mistakes that marred Bush’s tenure in the Oval Office. Bush declared himself to be the first CEO president, by which he meant that he would organize his administration to reflect what he saw as the best practices of modern corporate America. In particular, he preached delegation and accountability: he would establish the broader vision for his team, grant his senior managers latitude in how to carry out to realize that vision in their areas of responsibility, and then hold them accountable for their performance.

The execution of this approach led to disaster in the Iraq War. Bush permitted Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld to exercise too much discretion in the run up to the invasion in 2003, resulting in belated and inadequate planning for the postwar stability operations. Then the president compounded his initial mistakes by failing to hold Rumsfeld accountable for the failure to respond effectively to a mounting insurgency over the next two years. Bush ought to have accepted Rumsfeld’s resignation in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal or after the 2004 election. Instead, Rumsfeld lingered, despite indicators that Iraq was on a downward spiral and despite the widening gap between his desire to extricate American troops from the lead role in combating the insurgency and Bush’s avowed determination to stay the course.

In a careful account of Romney’s management style, Michael Barbaro, Sheryl Gay Stolberg, and Michael Wines depict a man who is far more hands-on than Bush 43. Romney comes across as detail-oriented, prepared to get down into the weeds and question carefully the ideas of his subordinates. This approach, too, carries risks. The Romney decision process they describe is deliberate and may bog down the person at the top in minutiae. In the White House, crises hit often and decisions have to be made quickly, often based on imperfect information. That said, it is hard to see Romney permitting a situation to drift the way Bush did in Iraq.

More troubling is Romney’s reluctance to jettison key subordinates who become liabilities. As Barbaro, Stolberg, and Wines point out, the governor sometimes boasts of his toughness by noting his willingness to fire workers when downsizing makes economic sense for a company. But he didn’t know these workers—they were nothing more than numbers on a balance sheet. When it comes to the people around him who fail to perform or embarrass the organization, he has found it far more difficult to toss them aside. The human sentiment is praiseworthy. A president, though, needs a degree of ruthlessness, both to achieve policy results and to contain the damage from political scandals that plague every administration.

The larger question is whether management style matters much in presidential success. Presidents have succeeded with different styles ranging from detail-oriented to big-picture focused; they have also failed with the same styles. For those who think Romney’s willingness to bore down into the fine details of policy would work well in the White House, we have the sobering example of Jimmy Carter, who let his determination to grasp the specifics swallow his presidency. Romney’s business experience also would count for less in the White House than he would like us to believe. Graham Allison, a distinguished public policy scholar, put it well when he argued that public management and private management are alike in all unimportant respects.

Thus the governor’s track record in Massachusetts is far more relevant in assessing his qualifications for the presidency than his leadership of Bain Capital. In that vein, voters might be chagrined to learn that Massachusetts ranked 47th in the nation in job creation in the Romney years. And growing a national economy is even more challenging that bolstering that of a single state. From this perspective, the governor’s boast that he knows how to grow jobs looks pretty empty.

In the end, management style and experience constitute just one element in successful presidential leadership. Other personal attributes matter, too, as scholars such as Fred Greenstein have observed. I would argue that presidents also faced varying “opportunity structures” when they take office, shaped by a broad range of factors that include whether their party commands a working majority in Congress (increasingly this has meant sixty seats in the Senate), their public approval rating, how much world events absorb their attention, whether they have campaigned in a way that lets them claim a mandate to push ahead on their agenda, and more. This opportunity structure doesn’t remain static, either, so things that may be possible on day one of a new presidency won’t be doable a year later. Barack Obama discovered that he could do a great deal in his first year and very little once the Republicans reclaimed the House, an outcome driven in part by the very policy successes he had achieved.

Recognizing the shifting limits of the possible remains the central challenge for a president. Mitt Romney may be able to master it. But nothing his business record demonstrates that he would do so effectively.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Nucleic Acids Research and Open Access

In 2004, when the internet was pervading every aspect of science, the Executive Editors of Nucleic Acids Research (NAR) made the momentous decision to convert the journal from a traditional subscription based journal to one in which the content was freely available to everyone, with the costs of publication paid by the authors. There was great trepidation, by the editors and Oxford University Press, that authors would refuse to do this and instead would choose to publish elsewhere. Indeed there were certainly some authors who withdrew their submissions when informed of the new policy, but surprisingly many fewer than had been feared. An even greater fear was that the libraries who subscribed to the journal would immediately unsubscribe, thereby reducing the income that had traditionally supported the journal. Had that happened en masse, Nucleic Acids Research would probably not have survived those first tumultuous years. However, during that period open access publication was receiving a great deal of support within the scientific community and movements such as the Public Library of Science, arguing in favor of this approach to scientific publishing were very persuasive for many scientists. Nucleic Acids Research, being the first well-established, subscription-based journal to choose this path meant that we provided a forum whereby authors could show their support for the movement. Furthermore, libraries help immensely by not immediately cancelling their subscriptions.

As chief US Editor of Nucleic Acids Research at the time I felt quite strongly that this move to open access would be a very positive move for the journal and that rather than deterring authors it would be viewed in a very positive light. After all, one of the reasons for publishing is so that new scientific advances can be disseminated as widely as possible, thereby enhancing the reputation of the authors and of the journal. Despite the fact that all major universities would be subscribers to the journal, there were many scientists — in companies, in the developing world and many of the small teaching colleges — who would not have subscriptions and so would lack any sort of access to the papers appearing in our journal prior to our move to open access. Furthermore, Nucleic Acids Research had always been a leader in innovation — we were one of the first journals to demand that authors of sequence papers must deposit those sequences in GenBank — and so this could provide yet another example of our forward-looking policies. I am happy to report that not only did NAR survive those first few years, but both the quantity and the quality of submissions have steadily risen ever since.

Already, open access is widely seen to be the model of choice for scientific publication and it seems implausible that ten years from now our scientific children would choose to publish in any other way. They will probably look back and wonder how it was even possible that subscription-based publication could have been viewed as an appropriate way to disseminate scientific findings once the internet became a reality. Those journals that fail to embrace open access may discover that they have become obsolete. Nature and Science, two journals that could have greatly speeded the acceptance of open access publication had they been truly interested in the good of science, instead of being profit-driven, may be looked upon as dinosaurs of a previous age. While Nucleic Acids Research almost immediately made all of their back content freely available to everyone, one of the great challenges going forward will be to convince all journals that they should behave likewise. Only then will we truly have the “GenBank” of the scientific literature that was envisioned at the opening of the 21st century.

Rich Roberts is a Nobel Prize winning biochemist and molecular biologist, and is currently Chief Scientific Officer and New England BioLabs Inc. Rich was Chief US Editor at NAR between 1987 and 2009, and was instrumental in NAR’s transition to open access in 2004.

Nucleic Acids Research (NAR) publishes the results of leading edge research into physical, chemical, biochemical and biological aspects of nucleic acids and proteins involved in nucleic acid metabolism and/or interactions.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Place of the Year 2012: Behind the longlist

Last week, we launched Place of the Year 2012 (POTY), a celebration of the year in geographical terms. As Harm de Blij writes in Why Geography Matters: More than Ever, “In our globalizing, ever more inter-connected, still-overpopulated, increasingly competitive, and dangerous world, knowledge is power. The more we know about our planet and its fragile natural environments, about other peoples and cultures, political systems and economies, borders and boundaries, attitudes and aspirations, the better prepared we will be for the challenging times ahead.”

With this in mind, let’s take a look at the 2012 POTY nominees that highlight the history and culture of the year and that give insight into the future.

This year, Africa has been ripe with change. In March 2012, Kony 2012, a short film by Invisible Children, Inc., dominated the social media sphere, calling attention to Ugandan guerilla groupleader and indicted war criminal Joseph Kony. The film and its backlash sparked a closer look at East Africa. One year following the Arab Spring, it’s important to note developments in post-revolution Egypt and Libya. The destruction of Timbuktu’s most sacred sites, designated UNESCO World Heritage sites, this summer points to growth of Islamist groups in Mali.

Elsewhere, Myanmar (also known as Burma) began a slow process of reform and Syria spiraled into civil war. Turkey, the fastest growing tourist destination, is a key player in the Syrian conflict and Middle East affairs as a whole. Amid concerns over Iran’s nuclear weapons capabilities, will regional and international conflict explode? In another corner of the world, island disputes embroil Japan, China, Taiwan, and South Korea. As Japan, China, and Taiwan debate control over the Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands, tensions are flaring between South Korea and Japan over the Dokdo or Takeshima Islands. While Greece struggles with economic disaster, Shanghai, China’s financial center, might soon become the financial capital of the world.

Politics and economics aside, 2012 has been a remarkable year for science. Between the likely discovery of the Higgs boson at CERN in Switzerland and NASA’s Curiosity Rover mission on Mars, scientists have given the public a renewed sense of wonder about the world. Not all discoveries are worth celebrating; the continued effects of global warming in the Arctic Circle, unfortunately, are a cause for concern — and a territorial race to claim previously inaccessible oil and natural gas deposits. The environmental changes will reverberate around the world.

In the United States this year, Pass Christian, Mississippi, a post-hurricane phoenix, is hometown to Robin Roberts, Good Morning America anchor and inspiration to cancer survivors everywhere. The Barnes Collection now joins the Phillies, the Eagles, the Flyers, Rocky, and cheesesteaks as children of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In Washigton, DC, maintaining the constitutionality of Obamacare and rejecting Arizona’s policies towards immigrants are only two of the historic decisions made by the United States Supreme Court this year. With affirmative action and possibly California’s Proposition 8 on the Supreme Court’s docket, history will continue to be made in the coming term.

On these chilly fall days, there are some Oxford employees who dream of pie à la mode from the dessert’s hometown in Cambridge, NY or a vacation to Belize’s beautiful beaches and mountains. Others wistfully imagine a bellini at Harry’s Bar in Venice or curling up on the couch to watch “Keeping up with the Kardashians,” set in Calabasas, CA, or “The Wire,” set in Baltimore, MD, home to Michael Phelps, the world’s most decorated Olympian. And if you’re not hanging out in Bed-Stuy, Montauk, or at The Standard Hotel in West Hollywood, then where is your “cool” hangout?

Use the voting buttons to make your choice, or leave a nomination in the comments. Check back here weekly to get insights into geography, and stay tuned for the short-list announcement on November 12th.

What should be the place of the year in 2012?

AfricaMyanmar/BurmaSyriaIranGreeceEgyptBelizeTimbuktu, MaliLondon, United KingdomCalabasas, California, USABenghazi, LibyaIstanbul, TurkeyShanghai, ChinaMontauk, New York, USABaltimore, Maryland, USAPass Christian, Mississippi, USAPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania, USABed-Stuy, Brooklyn, New York, USACERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), Switzerland Supreme Court of the United States, Washington, DC, USABryant Park, New York City, USAThe Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands, contested by Japan, China, and TaiwanCambridge, New York, USAOne World Trade Center, New York City, USAArctic CircleHalf Moon Island, Antarctica MarsThe Standard Hotel in West Hollywood, California, USAHarry's Bar, Venice, ItalyThe Dokdo or Takeshima islands, contested by South Korea and Japan

View Result

Total votes: 53Africa (0 votes, 0%)Myanmar/Burma (3 votes, 6%)Syria (3 votes, 6%)Iran (0 votes, 0%)Greece (2 votes, 4%)Egypt (0 votes, 0%)Belize (1 votes, 2%)Timbuktu, Mali (0 votes, 0%)London, United Kingdom (14 votes, 26%)Calabasas, California, USA (2 votes, 4%)Benghazi, Libya (0 votes, 0%)Istanbul, Turkey (3 votes, 6%)Shanghai, China (0 votes, 0%)Montauk, New York, USA (0 votes, 0%)Baltimore, Maryland, USA (1 votes, 2%)Pass Christian, Mississippi, USA (0 votes, 0%)Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA (1 votes, 2%)Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, New York, USA (0 votes, 0%)CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), Switzerland (7 votes, 13%)Supreme Court of the United States, Washington, DC, USA (1 votes, 2%)Bryant Park, New York City, USA (0 votes, 0%)The Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands, contested by Japan, China, and Taiwan (1 votes, 2%)Cambridge, New York, USA (0 votes, 0%)One World Trade Center, New York City, USA (0 votes, 0%)Arctic Circle (1 votes, 2%)Half Moon Island, Antarctica (0 votes, 0%)Mars (12 votes, 23%)The Standard Hotel in West Hollywood, California, USA (0 votes, 0%)Harry's Bar, Venice, Italy (0 votes, 0%)The Dokdo or Takeshima islands, contested by South Korea and Japan (1 votes, 0%)

Vote

And don’t forget to share your vote on Twitter, Facebook, Google Plus, and other networks:

“I voted [my choice] for Place of the Year http://oxford.ly/poty12 #POTY12 via @OUPAcademic”

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

October 20, 2012

The unshackled cultivation of Rimbaud

By Martin Sorrell

Among the enfants terribles of literature, Rimbaud holds a pre-eminent place. But he’s been made famous against his will. If he had his way, everything he wrote — save perhaps his factual letters from Africa and elsewhere about trade and the dodgy deals he was trying to clinch – would have been destroyed. All the astonishing poetry that has made him an icon burnt on a bonfire of vanities, but fortunately it was saved. He issued his order to burn at the ripe age of roughly 21, by which time he was through with all artistic pretentions. As he put it in one of the Illuminations, he’d seen and done it all (‘Assez vu… Assez eu… Assez connu’). If, he implied, he’d had the gall to think he could do great things with poetry, change the world no less, now he’d been disabused. Henceforth, for the 16 odd years of life left to him, the book of poetry was resolutely shut. No more chasing the Vision; now, just the ledgers of commerce.

Arthur Rimbaud was born in 1854 in Charleville-Mézières, N.E. France. His relationship with his parents was deeply troubled. His mother was cruel and had no time whatsoever for his scribblings. Fortunately, a couple of his enlightened school teachers did. They saw the precocity, the budding genius of a boy scarcely into his teens who was writing impeccable Latin verse exercises, soon followed by truly original French poems of his own: unique, technically brilliant, disturbed, and dissatisfied poems of restlessness, yearning, and reaching for the unknown; sharp, angular poems such as the satirical ‘A La Musique’, the merciless ‘Les Assis’, the political jab of ‘Rage des Césars’.

Aged 17, Rimbaud had had enough of Mézières, so he walked to Paris, met Verlaine, behaved like a lout, and seduced the weak-willed Verlaine off to London, Brussels, and prison (that’s a whole other story). By now, Rimbaud’s poetry had moved on and was breaking new ground as he left behind his predictable bourgeois targets, and went soaring and sailing among his visions. In ‘Le Bateau ivre’ (the Drunken Boat), he’s left us a masterpiece. Read it and at the same time read his famous ‘Lettre du voyant’ (the Visionary’s Letter). Both date from 1871. If the letter talks of visions, the poem is the Vision. The letter calls for a whole new way of being no less, individually, and by happy extension, collectively. It sets out how the true poet must work pitilessly on himself to become a visionary. There must be a dérèglement de tous les sens, the unshackled cultivation of all sensory experience. Swallow poison, cover yourself in ulcers, turn your body and mind into a laboratory of experiments, pay no heed to personal discomfort and damage. And if you’re half-destroyed in the process, so be it. The reward will be that you arrive at The Unknown.

But the dazzling ambitions of the letter were in the end more illusion than illumination. That’s how the defeated Rimbaud saw it anyway. Alongside the magnificent poems in verse, alongside those enigmatic bulletins from the Unknown, the Illuminations, encrypted in irreducible prose, you have to read Une Saison en enfer, the 19-year-old Rimbaud’s season in hell. It’s his bitter farewell to his old self, a disgusted note of poetic suicide. Goodbye to the Unknown, to his boast that he could lead us there. It’s goodbye to his partner-in-poetry Verlaine, goodbye to the dark land of his mother, goodbye to Europe and what he calls its ‘ancient parapets’, and a scornful, self-castigating goodbye to poetry, to reading and writing and thinking about the stuff. From the collapse of the dream to his premature and wretched death in 1891, aged 37, lying riddled with cancer in a Marseille hospital, minus an amputated leg, Rimbaud plunged into the solitary, peripatetic life of soldier, deserter, circus act, quarry foreman, and gun-runner. He walked everywhere, across Europe and into the Horn of Africa, intent only on securing the material things of this mercantile world. From the poet with the wind in his heels, as Verlaine once described him, Rimbaud finished up a dealer in death, trying to sell rusting rifles to an African king.

The sad and exemplary defeat of Art, apparently. Yet, because certain people neglected to do his bidding and burn his writings, Rimbaud has an unwished-for place in the high temple of literature. The density and power of his work are out of proportion to its modest dimensions. He’s become a secular god, an inspiration for so many other great artists as well as hopeless and hapless idealists. Not a benign god, you sense. If this lean and self-punishing ascetic limped back, he’d have little time for our self-indulgent ways. We’d have to keep our precious copies of his poetry out of sight of those piercing blue eyes; he’d be sure to burn them.

Martin Sorrell is a Professor of French and Translation Studies at the University of Exeter and the editor and translator of Arthur Rimbaud’s Collected Poems, Oxford World’s Classics edition.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers