Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1013

October 16, 2012

Chauvinism and idealism in American nationalism

When the Bush administration launched its campaign to gather US public support for the invasion of Iraq, I was especially struck by the way in which they managed to mobilise on the one hand chauvinist nationalist hostility to the outside world in general and Muslims in particular, and on the other hand a civic nationalist belief in America’s mission to spread democracy and freedom to those same Muslims. Often, meeting neoconservatives in particular, I would find a belief in the spread of democracy in the Middle East, and hatred and contempt for Arabs, strangely mixed in the very same people. I was also struck — and I have to say, horrified — by the way in which the promise of spreading democracy allowed the Bush administration, for a while at least, to co-opt a number of liberals whose other traditions and personal histories should have inclined strong opposition to the war.

America’s shared national ideology can act in certain circumstances to impose a kind of democratic, consensual suppression of independent and critical thought — a perception repeated by observers of the United States since Tocqueville. Louis Hartz (a great, almost forgotten analysts of American political culture) and others in the 1950s (including the great Richard Hofstadter) examined the McCarthyite phenomenon of chauvinist hysteria and repression in the name of democracy. These thinkers represent a great American intellectual and moral tradition.

Developments in the USA after 9/11 made me deeply committed to doing my best in a small way to revive it. I became fascinated by the relationship of the apparently incompatible elements of chauvinism and idealism in American political culture and their deep roots in American history. This exploration led to an analysis of the whole complex of features which goes to make up American nationalism and American national identity.

As I dug further, other elements also came to the fore: the importance of conservative religion in the United States, and the ways in which since the very origins of the English colonies, it has become linked to hostility both to godless foreigners and godless American elites; and the deep racial fears of the old core white population in the face of blacks, Native Americans, and alien immigrants. This in turn led to an examination of the way in which successive waves of immigrants have been integrated into the United States in part through formal adherence to US political values and institutions, but also through joining with the former core groups in hostility to racial minorities or other, later waves of immigration.

I found myself analysing how American attitudes to race have shifted in recent decades (a question I had been fascinated by ever since spending time as a student in small-town Alabama in 1979). I call this America’s transition from “Herrenvolk (master race) democracy” to what I call a “civilizational empire”, comparable to those of Rome and China. White middle-classes in America have become more accepting of people of other colour (at least in public), without by any means necessarily becoming more tolerant of people of other culture. Successful integration still requires assimilation to conservative middle class values, including nationalism and religion.

Tax Day Tea Party Rally in Wisconsin, 2011. Photo by WisPolitics.com. Creative Commons License.

Indeed, what surprised me about Barack Obama’s election as president was not that a black man was elected, but that he was not a retired US general or admiral; in other words someone who could convince the white middle classes of his complete adoption of their culture. The sometimes feral and irrational hatred of Obama among conservatives, while it certainly derives in part from old racial fears, seems above all to reflect a sense of cultural difference. This has led to the mobilisation against Obama of two other sentiments on the Right: on the one hand, the belief that he is a “Black radical” (he has even been accused, grotesquely, of sympathy for the Black Panthers) who will tax whites to favour blacks; on the other, that he is part of a “liberal elite” which despises the values of ordinary Americans. Finally, on the wilder shores of conservative religion there is the belief that he is the Antichrist.

America’s magnificent “self-correction mechanism”, the power of its democratic values and institutions has repeatedly brought the country back to democratic stability and tolerance after episode of chauvinist hysteria like McCarthyism. I express however two fears in this regard: that this self-correction mechanism could be wrecked either if the United States suffered another really shattering terrorist attack like 9/11, or if the social and economic decline of the white middle classes (already apparent in 2004) continued indefinitely.

The first threat has, thank God, not yet come about, and the fears expressed in this regard after 9/11 seem to have been exaggerated. The decline of the white middle classes has however not just continued but intensified drastically as a result of the economic recession beginning in 2008. And because this decline is largely rooted in what look like inexorable global economic shifts, it is likely to continue (albeit in slower form) even if the economy as a whole recovers — or that at least was the pattern of the generation before 2008.

I was not therefore surprised by the rise of the Tea Party movement in recent years, nor by the way in which Tea Party supporters have combined deeply irrational politics with a fanatical adherence to a Constitution rooted in the ideas of the Enlightenment. Albeit in this highly specific American way, the Tea Parties represent one facet of lower middle-class radical conservative politics with troubling echoes in the European past. To judge by the history of the past 40 years, even if the Tea Parties fail to seize control of the Republican Party as a whole, and if Mitt Romney is defeated in November, they will still — like US radical conservative movements since the 1970s – leave the party several notches to the Right from where they found it. Indeed, as has been remarked, Ronald Reagan’s Republican programme in the 1980 presidential elections would be regarded by Republicans of today as dangerously liberal — and is indeed close in spirit to Obama’s approach.

This tendency has helped polarise US politics, and combined with the complex system of checks and balances in the US Constitution to make it very difficult to push through desperately needed economic reforms. By the same token, the fanatical version of civic nationalism espoused by the Tea Party makes it inconceivable that the Republican Party would agree to even the kind of limited constitutional amendments of the past, so as to bring the 18th Century Constitution into line with 21st Century needs. I am deeply worried that as a result of the features I have mentioned, the United States may be entering an era of profound crisis, the outcome of which cannot be foreseen.

Anatol Lieven is a professor in the War Studies Department of King’s College London and a senior fellow of the New America Foundation in Washington DC. He is the author of America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism, recently published in its second edition. Anatol Lieven recently took part in a panel discussion on the 2012 US election and Asia at the Australian National University in Canberra (view footage of the event).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to American history on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

American football on TV and the music of the night

Monday Night Football has been a staple of American television for over forty years. The first Monday night broadcast aired on the ABC network on 21 September 1970, with a game between the New York Jets and the Cleveland Browns. Ever since, Monday Night Football (MNF) broadcasts have rarely been topped in the Nielsen ratings. After a storied run on ABC, MNF moved to the popular sports cable network, ESPN, in 2006. That same year, NBC instituted Sunday Night Football, which became the marquis game of the week for the National Football League.

Nighttime TV broadcasts of professional football in the USA have been about much more than just the game. From its beginnings in 1970, ABC sports producer Roone Arledge hired controversial New York broadcaster Howard Cosell, former Dallas quarterback (“Dandy”) Don Meredith, and (a year later) ex-NY Giant player Frank Gifford as the broadcast team. Still later, ex-Detroit Lions player Alex Karras joined the crew. The team jelled behind Cosell’s bluster, Meredith’s southern “down home” style, Gifford’s boyish good looks, and Karras’ comedy. Besides the chemistry of the broadcast team, MNF also regularly featured celebrity guests such as Vice President Spiro Agnew, singers Plácido Domingo and John Lennon, President Bill Clinton, actor and California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, and even Muppet Kermit the Frog. The 9 December 1974 broadcast was especially notable as it featured interviews of both John Lennon and California Governor Ronald Reagan during the game. As the game progressed, the broadcast featured Reagan explaining the rules of American football to Lennon off-camera.

MNF Theme Music throughout its History

To reflect the carnivalesque nature of the show, MNF has been introduced by musical themes that have been light, bouncy, pop-oriented pieces. The first introduction to MNF in the 1970s featured images of broadcasters Cosell, Meredith, and Gifford getting ready to go on the air, giving way to animated scenes of football players in action. This opening was accompanied by Charles Fox’s tune called “Score,” recorded under the alias, ‘Bob’s Band.’ “Score” is a bit of light 1970s soul-jazz, with the quintessential Hammond electric organ playing lead, along with a Hollywood-style brass section layering the top.

Click here to view the embedded video.

By 1976, the theme to MNF was replaced by “ABC’s Monday Night Football Theme,” by composer Joe Sicurella.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The piece retains the light, swingy entertainment aspect of the show, reminiscent of 1970s Philly Soul in the style of The Temptations or MFSB. The theme underwent another transformation in 1982. Apparently, Sicurella’s theme was re-scored by Robert Israel of Score Productions for ABC, for which Sicurella unsuccessfully sued for copyright infringement.

In 1989, MNF switched to a new theme song, entitled “Heavy Action” by British composer and pianist, Johnny Pearson. ABC actually acquired the song in 1978, but did not use it for the show until the late 1980s.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The theme opens with a descending four-note motive, which some bloggers say is “the most recognizable four notes in all of television.” This motive is followed by a chromatically rising line in the strings, punctuated by brass “stabs,” reminiscent of 1970s disco or even “Blaxploitation” film music.

“Heavy Action” continues as the current theme for MNF, but has been remixed with a slightly harder “edge,” featuring a “heavy metal” guitar mixed in with the strings and brass:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Music, Football, and Ethnicity

All the musical themes used for MNF are upbeat, light pieces, signifying a fun, light entertainment for its audience. All the themes also tap into the pop idioms of the time, and thus represent a departure from the “college march” pieces of football broadcasts of earlier eras, like this 1957 footage:

Click here to view the embedded video.

In addition, each of the MNF themes carries with it a mixture of stylistic elements that seeks a wide, diverse audience. The themes all demonstrate a virtuosic blend of pop/rock, some Hollywood style “TV music” (usually expressed in the brass writing), along with aspects of funk, soul, and even disco; musical genres that are frequently historically associated with urban black artists and audiences. No one musical style dominates within any of the themes, but elements of several genres reach across lines of race and ethnicity and combine into the harmonious whole of each piece.

In short, the theme music played on MNF throughout the years does what TV theme music should do, that is, to reach out to as many audience demographics as it can and summon them to the small screen. But in doing so, the MNF themes have also reflected back the racial and sociographic diversity of the football players on the show, as well as its fan base.

The Shape of Things to Come: Sunday Night Football

NBC has taken a decidedly different tact with its Sunday Night Football theme. The theme is by the famous (and ubiquitous) film composer, John Williams (who also composed theme music for NBC’s broadcast of the Olympics), and departs from the light entertainment model of the ABC/ESPN theme.

As one blogger puts it, the theme is “Football’s Imperial March.” Williams’ theme implies a militant march rather than a light, harmonious entertainment piece of MNF. This is a new trend in the perception of football and its athletes, who were once considered entertainers, but are now perceived as gladiators.

In memoriam, Alex Karras, 1935-2012. Rest in Peace.

Next month: More NFL football music!

Ron Rodman is Dye Family Professor of Music at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. He is the author of Tuning In: American Television Music, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. Read his previous blog posts on music and television.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

October 15, 2012

Announcing the Place of the Year 2012 Longlist: Vote!

As the year winds down, it’s time to take a look back. Alongside the publication of the 19th edition of The Atlas of the World, Oxford University Press will be highlighting the places that have inspired, shaped, and challenged history in 2012.

We’re also doing things differently for Place of the Year (POTY) in 2012. In addition to our regular panel of geographers and experts, we’re opening up the choice to the public. Use the voting buttons below to vote for the place you feel deserves the glory. If we’ve forgotten the location that has inspired or provoked this year, leave us your nomination and the reason why you chose it in the comments.

Nominations can be as large or small of a landmass as you like — from your favorite diner to a news-making country to an entire planet. London, for example, has had a lot to celebrate this year between the Queen’s Jubilee and a breathtaking Olympics. Shall we let London celebrate a POTY victory as well? Or, take a look at Mars: it might not be part of Earth, but NASA’s Curiosity Rover has shared its discoveries with the world and made space a little less alien. Maybe you’re drawn to the sites of revolution in Syria, or to the Calabasas, California base of the Kardashians. Whatever your flavor, we want to hear from you!

Your votes and nominations will help drive the shortlist announcement on November 12th. And after another round of voting from you the public and further consultation with OUP’s panel of geographers and experts, we’ll announce the winners on December 3rd. Until then, check back here weekly for more insights into geography and Place of the Year 2012. Happy voting, geographers!

What should be the place of the year in 2012?

AfricaMyanmar/BurmaSyriaIranGreeceEgyptBelizeTimbuktu, MaliLondon, United KingdomCalabasas, California, USABenghazi, LibyaIstanbul, TurkeyShanghai, ChinaMontauk, New York, USABaltimore, Maryland, USAPass Christian, Mississippi, USAPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania, USABed-Stuy, Brooklyn, New York, USACERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), Switzerland Supreme Court of the United States, Washington, DC, USABryant Park, New York City, USAThe Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands, contested by Japan, China, and TaiwanCambridge, New York, USAOne World Trade Center, New York City, USAArctic CircleHalf Moon Island, Antarctica MarsThe Standard Hotel in West Hollywood, California, USAHarry's Bar, Venice, ItalyThe Dokdo or Takeshima islands, contested by South Korea and Japan

View Result

Total votes: 0Africa (0 votes, 0%)Myanmar/Burma (0 votes, 0%)Syria (0 votes, 0%)Iran (0 votes, 0%)Greece (0 votes, 0%)Egypt (0 votes, 0%)Belize (0 votes, 0%)Timbuktu, Mali (0 votes, 0%)London, United Kingdom (0 votes, 0%)Calabasas, California, USA (0 votes, 0%)Benghazi, Libya (0 votes, 0%)Istanbul, Turkey (0 votes, 0%)Shanghai, China (0 votes, 0%)Montauk, New York, USA (0 votes, 0%)Baltimore, Maryland, USA (0 votes, 0%)Pass Christian, Mississippi, USA (0 votes, 0%)Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA (0 votes, 0%)Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, New York, USA (0 votes, 0%)CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), Switzerland (0 votes, 0%)Supreme Court of the United States, Washington, DC, USA (0 votes, 0%)Bryant Park, New York City, USA (0 votes, 0%)The Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands, contested by Japan, China, and Taiwan (0 votes, 0%)Cambridge, New York, USA (0 votes, 0%)One World Trade Center, New York City, USA (0 votes, 0%)Arctic Circle (0 votes, 0%)Half Moon Island, Antarctica (0 votes, 0%)Mars (0 votes, 0%)The Standard Hotel in West Hollywood, California, USA (0 votes, 0%)Harry's Bar, Venice, Italy (0 votes, 0%)The Dokdo or Takeshima islands, contested by South Korea and Japan (0 votes, 0%)

Vote

And don’t forget to share your vote on Twitter, Facebook, Google Plus, and other networks:

“I voted [my choice] for Place of the Year http://oxford.ly/poty12 #POTY12 via @OUPAcademic”

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Friend, foe, or frontal lobe?

In a scene from the movie The Shadow, the evil villain Khan, the last descendant of Genghis Khan, is defeated by the Shadow who hurls a mirror shard deep into his right frontal lobe. Khan doesn’t die, but awakens in an asylum, confused as to how he got there and discovering that his powers no longer work. The doctors saved his life by removing the part of his brain that harbored his psychic abilities — his frontal lobes. Unknown to Khan, the doctor is an agent of the Shadow who has ensured that Khan is no longer a threat.

Even in “B” movies, there is a general acceptance that damage to the frontal lobes can produce dramatic changes, including remarkable alterations in personality. The most famous example of this is the well-known and publicized case of Phineas Gage. Phineas was working on building a railroad in Vermont in the mid-1800s when an accidental dynamite discharge sent a long iron tamping bar through his left cheek and into his frontal lobes. Gage lived but Harlow, who reported the case in 1868, concluded that after the accident he was “no longer Gage”. The change was so dramatic that the essence of his personality appeared to be different. This case is so striking it has been documented on the TV series “Ripley’s Believe it or not”.

The history of brain research has called the frontal lobes a mystery, this brain region a riddle. But solving such mysteries is the joy of frontal lobe researchers. If the frontal lobes are so important…

Why has it taken so long for the study of the frontal lobes to permeate deeply into cognitive neuroscience research, particularly considering it represents 25-33% of the entire brain?

Can an individual have a very high IQ even when the frontal lobes are significantly damaged?

Why do researchers have so much difficulty understanding the role of different regions of this brain region?

How can we use our knowledge of frontal lobe functioning, to help direct our rehabilitation and compensation efforts?

If the frontal lobes are so developed in humans why is there so much interpersonal and societal violence?

The writer or producer of The Shadow focused on one particular region of the frontal lobes, as if they knew the importance of one region over the next. The potential localization of function within the frontal lobes has been a contentious theoretical issue for years. Glad to know that movies have solutions to our questions.

Donald T. Stuss and Robert T. Knight are the authors of Principles of Frontal Lobe Function, newly released in its second edition. Donald T. Stuss, Ph.D., C. Psych., ABPP-CN, Order of Ontario, FRSC, FCAHS, is the founding (2011) President and Scientific Director of the Ontario Brain Institute; a Senior Scientist at the Rotman Research Institute of Baycrest Centre; University of Toronto Professor of Medicine (Neurology and Rehabilitation Science) and Psychology; founding Director of the Rotman Research Institute at Baycrest 1989 – 2008. Robert T. Knight, MD, received a degree in Physics from the Illinois Institute of Technology, an MD from Northwestern University Medical School, obtained Neurology training at UCSD and did post-doctoral work at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. He was a faculty member in the Department of Neurology at UC Davis School of Medicine from 1980-1998 and moved to UC Berkeley in 1998 serving as Director of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute from 2001 until 2011. He founded the UC Berkeley-UCSF Center for Neural Engineering and Prosthesis in 2010.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine questions on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The Day Parliament Burned Down in real-time on Twitter

To mark the anniversary of a now little-remembered national catastrophe – the nineteenth-century fire which obliterated the UK Houses of Parliament – Oxford University Press and author Caroline Shenton will reconstruct the events of that fateful day and night in a real-time Twitter campaign. Here’s the story so far. Join us tomorrow, 16 October 2012!

View the story “#ParliamentBurns” on Storify

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Read Caroline Shenton on OUPblog: London’s Burning! Ten Fires that Changed the Face of the World’s Greatest City.

Tennyson in 2012

2012 has been a good year for the Victorian novel. The dizzying number of adaptations, exhibitions, and readings which have been organised to celebrate the bicentenary of the birth of Charles Dickens testify to the ongoing popularity of nineteenth-century fiction, and of this most famous of Victorian novelists in particular. It’s fair to say that, both in the nineteenth century and now, Victorian poetry has struggled to match the popular profile and commercial appeal of the novel. But the writings of one Victorian poet, possibly the only poet who could compete with novelists like Dickens for fame and success during the nineteenth century, seem to have been cropping up everywhere in 2012. It’s been a good year, too, for Alfred Tennyson.

2012 has been a good year for the Victorian novel. The dizzying number of adaptations, exhibitions, and readings which have been organised to celebrate the bicentenary of the birth of Charles Dickens testify to the ongoing popularity of nineteenth-century fiction, and of this most famous of Victorian novelists in particular. It’s fair to say that, both in the nineteenth century and now, Victorian poetry has struggled to match the popular profile and commercial appeal of the novel. But the writings of one Victorian poet, possibly the only poet who could compete with novelists like Dickens for fame and success during the nineteenth century, seem to have been cropping up everywhere in 2012. It’s been a good year, too, for Alfred Tennyson.

May 2012 saw the publication of the paperback of Alan Hollinghurst’s novel The Stranger’s Child, which takes its title from In Memoriam, Tennyson’s 1850 elegy for his best friend Arthur Henry Hallam:

Till from the garden and the wild

A fresh association blow,

And year by year the landscape grow

Familiar to the stranger’s child;

As year by year the labourer tills

His wonted glebe, or lops the glades;

And year by year our memory fades

From all the circle of the hills.

In the first part of Hollinghurst’s novel these lines are read at a family gathering in the summer of 1913. The rest of the book records the damage inflicted on its characters by the First World War, and traces their fortunes across the rest of the twentieth century. The Stranger’s Child employs Tennyson’s writing as the starting-point for a meditation on grief, the fragility of love, and the impermanence of memory, which “fades” and transforms “year by year.” For Hollinghurst, it seems, Tennyson’s poetry is nostalgic, melancholy, painfully sensitive to the ravages of time.

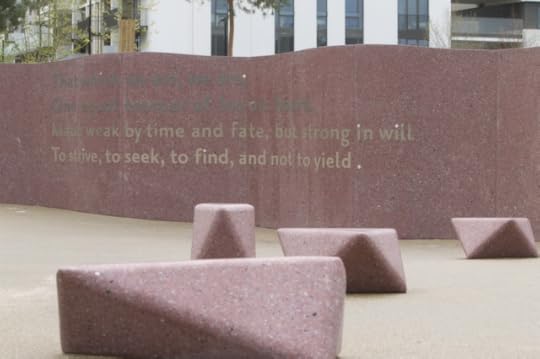

A different side of Tennyson was brought out when his poetry was used in an event even bigger than the Dickens bicentenary: the London Olympic and Paralympic games. As part of the Winning Words initiative, the closing lines of Tennyson’s dramatic monologue “Ulysses” were chosen as the inscription for a wall in the athletes’ village:

that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

These lines, it was hoped, would motivate athletes to strive for glory in their events, and although it’s hard to judge how much credit we should give Tennyson for the widespread success of British athletes in the games, his poetry was wholeheartedly embraced as a source of inspiration in some quarters. The last line of “Ulysses,” especially, was adopted as a sort of unofficial Olympic motto, to rival “faster, higher, stronger.” The poet Daljit Nagra, one of the judges who chose the Tennyson inscription, described the line as “a clarion call to the best parts of our searching, inquiring selves, which is just as suited to a gold-medal winner as it is to an ordinary worker in their daily round.” This clarion call was heard again and again throughout the summer, as the words “to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield” were quoted in a speech by David Cameron, and in editorials and opinion pieces in The Sunday Times and The Telegraph. In each case, the line was held up as an exemplary statement of perseverance, aspiration, and optimism, a fit epigraph for games that were widely considered to be an unqualified success.

Despite their apparently firm resolve, however, the lines from “Ulysses,” like those from In Memoriam, are also preoccupied with the transience of life and the depredations of time. However “strong in will” he might be, the Ulysses of Tennyson’s poem is an old man, and his will faces some tough opposition in the intractable forces of “time and fate.” As many readers and critics have noted, it’s difficult to read that last line without worrying that he might, in the end, “yield” after all. In Memoriam and “Ulysses” are two of Tennyson’s most nuanced reflections on the psychological experiences of memory and hope, and the quotations from the two poems reveal a deeply ambivalent writer, torn between optimism for the future and regret for the past. This ambivalence, a confidence undercut by doubt and self-questioning, is arguably characteristic of Victorian culture more generally, and the visibility of Tennyson’s words in 2012 suggests that Victorian poetry, although not as immediately well-known as the Victorian novel, has retained much of its cultural relevance and emotional resonance. It can still move and inspire; just ask the Olympic medal-winners.

Despite their apparently firm resolve, however, the lines from “Ulysses,” like those from In Memoriam, are also preoccupied with the transience of life and the depredations of time. However “strong in will” he might be, the Ulysses of Tennyson’s poem is an old man, and his will faces some tough opposition in the intractable forces of “time and fate.” As many readers and critics have noted, it’s difficult to read that last line without worrying that he might, in the end, “yield” after all. In Memoriam and “Ulysses” are two of Tennyson’s most nuanced reflections on the psychological experiences of memory and hope, and the quotations from the two poems reveal a deeply ambivalent writer, torn between optimism for the future and regret for the past. This ambivalence, a confidence undercut by doubt and self-questioning, is arguably characteristic of Victorian culture more generally, and the visibility of Tennyson’s words in 2012 suggests that Victorian poetry, although not as immediately well-known as the Victorian novel, has retained much of its cultural relevance and emotional resonance. It can still move and inspire; just ask the Olympic medal-winners.

Gregory Tate is Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Surrey. His book, The Poet’s Mind: The Psychology of Victorian Poetry 1830-1870, will be published by Oxford University Press in November 2012. You can follow him on Twitter @drgregorytate.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credits:

1: John Everett Millais’s portrait of Lord Alfred Tennyson, in public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

2: Photograph of Tennyson’s Olympic epigraph by Adriana Marques. By kind permission of the Olympic Delivery Authority and Forward Arts Foundation.

October 14, 2012

Watch your cancer language

People who have lived through cancer just want to get on with their lives — head into the future like everybody else, free of cancer, free of its memory. That’s why the labels others affix to us can make us especially testy.

Take, for example, the label survivor. Please. It look me a while after diagnosis to understand why this word annoyed those who have survived. Finally, when I started to be lumped into that category, I got it. The word defines us by our disease. And how can we move past this diagnosis if we are forever labeled according to it?

Some women prefer the word thriver, and I get that. It is active; it shows we are fully engaged in life. It’s a positive, affieming word. Survivor, by contrast, means we exist. We didn’t die. Not dying is a good thing — an extremely good thing — but it is not the only thing. If it is, then we are not really living, are we?

Still, I need no label. I am Pat. I had breast cancer and I, thank God, got over it.

What do we call survivors of heart attacks? I call them Hank and Herb and Mike. What do we call survivors of strokes? I call them Jean and Gary. Cancer need not be in a category of its own — the big scary disease. Those of us who have weathered its storms want to move beyond it. We’re wives, mothers, daughters, grandmothers, aunts, sisters, friends, lovers. We’re proud of these roles and find these labels wonderful. They make us fit in, feel a part of the world, of society, of our families, our communities.

Survivor sets us apart, and we’re tired of being special in a cancer sort of way.

We’re also writers, doctors, teachers, editors, students, artists, photographers, computer specialists, managers, volunteers, and tote a laundry list of other accomplishments. We have worked to earn these labels and encourage you to see us for what we have done, not what was done to us.

Then there is the issue of our courageous battle. I had several people tell me that I was so courageous while I went through treatment. Really? It is not courage to put one foot in front of another and just do what you need to do, usually while terrified and confused. Some of us do it with less complaint than others, but that is not courage. It is just good luck: a positive attitude, perhaps a better diagnosis, smoother response to treatment, or a support system that keeps us grounded.

To me, courage refers to soldiers in Afghanistan, or the person who jumps into a raging river to save a woman whose boat has capsized, or politicians voting for what they know is right but might not get them reelected.

And, frankly, it applies more to our caregivers like my husband, who never let me say, “I have cancer,” correcting me to, “You had cancer.” Or the parents of children with cancer who have to fight for proper care and deal with the financial hit while supporting a confused and sick child. Or the children watching their mother lose her hair and reminding her how beautiful she is and how much they love her, all the while hiding their own fear.

The problem with calling cancer patients courageous, again, is that it sets us apart from everybody else. We are the Person with Cancer. How scary. How tragic.

Does an obituary say a person died of a courageous battle with heart disease? Why not? Why is cancer elevated to such a stage? And why does it bother us?

It’s a problem because when you are constantly told you need courage to get through this journey, it makes the road seem that much rougher, the climb that much steeper, the destination that much less clear. What’s more, what happens if we don’t beat the disease? Were we not brave enough? Did we not fight hard enough? Are we the biggest of the big losers?

All we want is to be normal again. To be just a person who once got sick but hopes not to get sick again. Someone who is trying to move on, leaving cancer far behind, kicking dust in its nasty old face.

Patricia Prijatel is author of Surviving Triple-Negative Breast Cancer, published by Oxford University Press. She is the E.T. Meredith Distinguished Professor Emerita of Journalism at Drake University. She will do a webcast with the Triple Negative Breast Cancer Foundation on 16 October 2012. Read her previous blog posts on the OUPblog or read her own blog “Positives About Negative.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

October 13, 2012

Gifting the mind

Neuroscience today is high tech: fantastic imaging machines churn out brain scans of the living, thinking brain, and computers crunch data to highlight patterns that may or may not fit the latest theory about how the mind works. How far we have come from the studies of the great neurologists and psychiatrists of the 19th century who relied on clinical descriptions of individual patients to further our knowledge of the brain and its mind. Or have we?

Often, the latest neuroscience article summarizing a mass of brain imaging data seems to tell us something we have known for a hundred years or more. Paul Broca, in his 1861 article describing his patient Tan, concluded that Tan’s loss of fluent speech was related to the lesion found at post-mortem in the third frontal gyrus of the left frontal lobe of his brain. High-tech experiments continue to support Broca’s discovery, albeit with greater precision (neuron by neuron), and the finding that there are variations across individuals in the extent of the brain area involved in fluent speech. But the central fact that this area of the brain is specialized for expressive language remains unchanged.

There is no argument about the limitations of single cases from the past; they couldn’t tell us which neurons were firing and which neurotransmitter was missing. So in these important ways neuroscience has made giant strides, leading to new treatments and prevention of neurological disease. But even in today’s world the clinical case study deserves considerable credit for laying the foundations for more “sophisticated” studies.

Case studies, often almost novelistic in tone, also play a role in engaging the non-neuroscientist in what could otherwise be a daunting topic. The experiences of patients with damaged brains and disordered minds are intrinsically interesting to many people, perhaps because we can all relate in some small way to forgetting important information, not being able to say a word although we know we know it, or becoming clumsy and inefficient when we are overtired or intoxicated. Neurological disorders of one sort or another are common, and few people reach midlife without being touched by a family member or close friend with a head injury, dementia, stroke, or other neurological problem.

The Russian neurologist, Alexandr Luria (1902-1977), is considered by many to be the “father” of neuropsychology, and one of his greatest contributions was his belief that the brain and mind were influenced not only by biological factors but also by social factors. Modern neuroscience having for many years dismissed such an idea now embraces it. Luria was a prolific researcher and published numerous comprehensive studies on language, perception, and memory, but it is his case studies that have stood the test of time. Whereas theories change as new data are gathered, carefully described clinical cases remain forever current. Luria’s intimate biographical studies, The Mind of a Mnemonist and The Man with a Shattered World, documented his patients’ lives and thoughts, not just over a few weeks, but over decades, an achievement that has perhaps been equaled recently by the most famous neuropsychological case of current times.

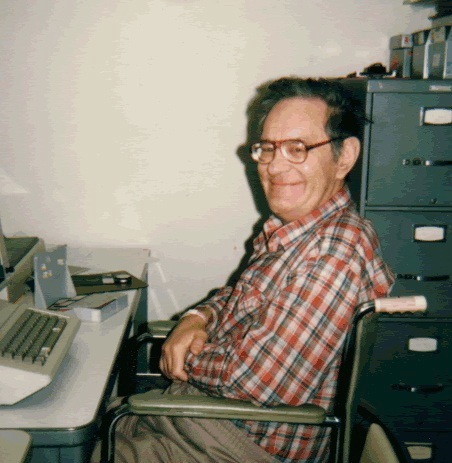

Henry Molaison, aged 60, enjoying an unmemorable memory experiment at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Photo by Jenni Ogden, 1986.

Henry Molaison lost his memory on an operating table in a Connecticut hospital in August 1953. He was 27 years old and had suffered from epileptic seizures for many years. His neurosurgeon, William Beecher Scoville, stood above an awake Henry and suctioned out the hippocampus — the seahorse-shaped structure lying within the temporal lobe — on both sides of the brain. Henry would have been drowsy and probably didn’t notice his memory vanishing as the operation proceeded. The operation was successful in that it significantly reduced Henry’s seizures, but it left him with a dense memory loss. Up until then it had not been known that the hippocampus was essential for making memories, and that if we lose both of them, we will suffer a global amnesia.

Montreal Neurological Institute neurosurgeon, Wilder Penfield, and neuropsychologist, Dr. Brenda Milner, quickly realized that Henry’s dense amnesia, his intact intelligence, and the precise neurosurgical lesions, made him the perfect experimental subject. For 55 years, Henry willingly (at least in the moment before each study) participated in numerous experiments, primarily in Dr. Suzanne Corkin’s laboratory at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Many patients with memory impairments have since been assessed, including a small number with amnesias almost as dense as Henry’s, but it is to him we owe the greatest debt. He has featured in almost 12,000 journal articles, making him the most studied case in medical or psychological history. Henry died on 2 December 2008, at the age of 82. Until then, he was known to the world, including thousands of psychology students, only as HM.

In another world-first, the Brain Observatory at UCSD dissected Henry’s tragically unique brain into 2401 paper-thin tissue sections during a 53-hour procedure (the whole process streamed live online) and digitized it as a three-dimensional brain map that could be searched by zooming in from the whole brain to individual neurons. The classic single case study fused with the very latest technology to provide, while the internet-savvy world watched, a unique data base for neuroscientists to use into the future.

Henry gave neuroscience the ultimate gift: his memory. Since the classic studies of neurological patients were published by Broca and Luria, thousands of people who have suffered brain damage, whether through accident, disease or a genetic quirk, have given priceless treasures to science by agreeing to participate in psychological, neuropsychological, and medical studies, often at a time when they are struggling with a serious illness. Many go a step further and donate their brains to science after their deaths. Our knowledge of brain disease and how the normal mind works would be greatly diminished if it were not for the generosity of these people. So next time you marvel at the latest high-tech brain imaging study, or benefit from a new treatment or procedure for a neurological condition, spare a thought for the patients, past and present, who made it possible.

Jenni Ogden is a clinical neuropsychologist and writer, who has a particular interest in the personal experiences of people who suffer brain damage. Her latest book, Trouble In Mind: Stories from a Neuropsychologist’s Casebook, focuses on 15 of her patients, each with a different disorder. You can read more on her personal website, Writing Off-Grid, or on her Psychology Today Trouble In Mind blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

October 12, 2012

Joyce Carol Oates at OUP NYC

OUP has just published the second and revised edition of The Oxford Book of American Short Stories, and we were happy to welcome Joyce Carol Oates into our Madison Avenue offices recently to sign stock, and to meet staff. Here are some photos of her with OUP employees.

Thomas Sullivan waits patiently

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Marketing Assistant, Publisher Services

Karen Omer rushes to get a place in line

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Editorial Assistant, Higher Education

Caroline Osborn speaks with Joyce as Allison Janice waits in the wings

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Both Editorial Assistants, Higher Education

Ross Yelsey and Joyce Carol Oates

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Executive Assistant to the Publisher, Higher Education

Lauren Mine and Joyce Carol Oates

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Development Editor, Higher Education

Joyce's hands never tire

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Kendra Frierson and Joyce Carol Oates

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Publications Controller, US Stock Planning

Ninell Silberberg and Joyce Carol Oates

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Assistant Marketing Manager, Law

Rob Repino and Joyce Carol Oates

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Editorial Assistant, Reference

Joyce Carol Oates and the Publicity Team

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Jonathan Kroberger, Alana Podolsky, Joyce Carol Oates, Coleen Hatrick, Aryana Chan

');

');tid('spinner').style.visibility = 'visible';

var sgpro_slideshow = new TINY.sgpro_slideshow("sgpro_slideshow");

jQuery(document).ready(function($) {

// set a timeout before launching the sgpro_slideshow

window.setTimeout(function() {

sgpro_slideshow.slidearray = jsSlideshow;

sgpro_slideshow.auto = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.nolink = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolinkpage = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.pagelink="self";

sgpro_slideshow.speed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.imgSpeed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.navOpacity = 25;

sgpro_slideshow.navHover = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.letterbox = "#000000";

sgpro_slideshow.info = "information";

sgpro_slideshow.infoShow = "S";

sgpro_slideshow.infoSpeed = 10;

// sgpro_slideshow.transition = F;

sgpro_slideshow.left = "slideleft";

sgpro_slideshow.wrap = "slideshow-wrapper";

sgpro_slideshow.widecenter = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.right = "slideright";

sgpro_slideshow.link = "linkhover";

sgpro_slideshow.gallery = "post-29308";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbs = "";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbOpacity = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.thumbHeight = 75;

// sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.spacing = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.active = "#FFFFFF";

sgpro_slideshow.imagesbox = "thickbox";

jQuery("#spinner").remove();

sgpro_slideshow.init("sgpro_slideshow","sgpro_image","imgprev","imgnext","imglink");

}, 1000);

tid('slideshow-wrapper').style.visibility = 'visible';

});

All are welcome at our New York City event on 15 October 2012 at 7 pm: WRITERS ON WRITERS, a Barnes & Noble literary event series where prominent writers discuss other writers whom they admire and/or have influenced their own work. Joyce Carol Oates will be talking with Edmund White.

Joyce Carol Oates is the National Book Award-winning author of over fifty novels, including bestsellers We Were the Mulvaneys, Blonde, and The Gravedigger’s Daughter, and the Roger S. Berlind Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at Princeton University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Intersections of sister fields

In March 2012, there was a discussion on the public folklorists’ listserv Publore about the evolution of oral history as a defined discipline and folklorists’ contribution to its development. As an observer and participant in both fields, I see overlap today. The leaderships of both national associations — the Oral History Association (OHA) and the American Folklore Society (AFS) — frequently collaborate on large-scale projects, like the current IMLS-funded project looking at oral history in the digital age. Their annual meetings regularly take place back-to-back. I often joke with colleagues when they ask me about the difference between the two conferences by suggesting that at OHA you might have a librarian or a rocket scientist who practices oral history, and at AFS you would have a folklorist working as a librarian or a rocket scientist.

When Alan Jabbour, former director of the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, started this 12-day listserv discussion, an interesting dialogue emerged around the distinction between ethnographers’ use of oral history and the relatively new emergence of oral history as a distinct field. As an oral historian by job title and function with academic and public training in folklore, I wonder: Where do folklore and oral history intersect? How do they intersect? Are they now interrelated, independent or completely disconnected?

These aren’t new questions. Richard M. Dorson was asking them in 1971. Folklorists, anthropologists and other ethnographers have all written about their discipline’s specific evolution — and oral historians have done the same. To some degree, the discussions of what early oral history did and didn’t look like mirror historic discussions of what folklore did and didn’t look like: ivory towers and armchairs vs. 50-lb. audio recorders and a hike through the woods.

The Publore discussion was really kicked off by countering the claim that the discipline of History “invented” oral history, citing early uses of the term by ethnographers like Alan Lomax and collections developed during the Federal Writer’s Project (FWP). I would guess many people today, no matter the background, immediately think of the 1937-1939 FWP effort to document the stories of ex-slaves as an early version of formalized oral history. This effort, led by John Lomax (folklorist and ethnomusicologist), documented on paper about 2,300 narratives.

There is no question that similar work was being done before journalist/historian Allan Nevins formed the first modern oral history archives at Columbia University in 1948. The claim that Nevins was the “father-figure,” or formalized starting point, for the discipline of oral history leaves out a lot of historical context. In fact, Jerrold Hirsch has written about this in the Oral History Review article “Before Columbia: The FWP and American Oral History Research.” While this event was a milestone in the solidification of oral history as a specialized field of study, it was by no means the beginning. As a responding Publore post from Jeff Todd Titon correctly suggests, the difference between Nevins and many of the ethnographically-trained precursors and contemporaries was that he was focused on a “top-down” approach.

Does that mean that folks practicing and participating in the development of the discipline of oral history all focused on the big shots? I would argue, no. Although it is true many of the institutionalized oral history offices that followed Columbia did take this “top-down” approach until the late 1960s, Don Ritchie attributes the first wide-spread popular culture use of the term “oral history” to a New Yorker article in 1942. This piece profiled efforts by Joseph Gould (a.k.a. Professor Sea Gull) to collect “an oral history of our time” in which Gould claims to “put down the informal history of shirt-sleeved multitudes.”

It is also worth noting that Nevins was a journalist-turned-historian. Traditional academic historians, for the large part, had discredited oral history/oral testimony as a reliable source of history by the mid-19th century with the popularization of the German school of scientific history (Von Ranke’s source-based history). It was really journalists, ethnographers, folklorists, anthropologists and less traditional, academy-based historians who were developing the framework for oral history as it is known today.

In “The History of Oral History” from the Handbook of Oral History, Rebecca Sharpless attributes the early- to mid-20th century legitimization of oral history to the FWP, the published works of folklorists like B.A. Botkin, and WWII military historians like Colonel S.L.A. Marshall and Forrest C. Pogue. Honestly, there is so much information out there, I am going to quit trying to cite it all — in fact, Tim Lloyd just posted an essay to OHDA discussing the differences between folklore and oral history. Instead, I’ve started a point-by-point timeline of the two disciplines. I hope the OHA and AFS conference attendees will comment on the timeline, or on anything they hear or discuss regarding the oral history/folklore dynamic.

Timeline of Oral History and Folklore

1859 — New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley conducts a publicized interview with Brigham Young

(influencing a trend in newspaper interviews).

1870 — California publisher, Hubert Howe Bancroft documents living memories of early pioneers to California and

the American west.

1878 — Thomas Edison promotes the first phonograph.

1888 — American Society is founded.

1890s — US Bureau of Ethnology sends researchers to record Native American stories/songs on to wax

cylinders.

1928 — Archive of Folk Culture is created.

1935 — Works Progress Administration hires unemployed writers to document the lives of ordinary citizens.

1936 — John Lomax, first WPA/Federal Writer’s Program folklore editor, instigates the ex-slave narrative project,

which will later be published under direction of B.A. Botkin.

1942 — The New Yorker publishes an article about Joseph Gould’s “Oral History of Our Time.”

1942 — The first commercial wire-recorder is marketed to the US military (estimated date).

1944 — World War II post-combat interviews are recorded just off the battlefield.

1948 — The first American-made tape recorders are launched (though not widely available until years later).

1948 — Columbia University Oral History Research Office is created.

1953 — The first US folklore PhD degree awarded to Warren Roberts at Indiana University.

1954 — The University of California at Berkeley begins the Regional Oral History Office.

1959 — The University of California Los Angeles’ Center for Oral History Research is institutionalized.

1960 — Harry S. Truman Library becomes the first presidential library with an oral history program.

1963 — The University of Pennsylvania awards its first PhD in folklore to Kenny Goldstein.

1967 — The Oral History Associationis founded.

1976 — The American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress is created.

1987 — The International Oral History Association is founded.

Get your comment posting frenzy on below!

Sarah Milligan has been the administrator for the Kentucky Oral History Commission since June 2007. She has a master’s degree in folk studies from Western Kentucky University’s Department of Folk Studies and Anthropology. She worked as a folklife specialist for the Kentucky Folklife Program before joining the Commission. During her time with the KFP, she worked as the statewide community scholars’ coordinator, and she continues to find enjoyment in working with communities by developing oral history projects. As administrator for KOHC, Milligan assists with a statewide oral history preservation effort, as well as encourage new and exciting oral history documentation in Kentucky.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview and like them on Facebook to preview the latest from the Review, learn about other oral history projects, connect with oral history centers across the world, and discover topics that you may have thought were even remotely connected to the study of oral history. Keep an eye out for upcoming posts on the OUPblog for addendum to past articles, interviews with scholars in oral history and related fields, and fieldnotes on conferences, workshops, etc.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers