Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1021

September 18, 2012

The September Surprise

Mitt Romney definitely did not count on foreign policy becoming a major issue two weeks after he chose budget hawk, Paul Ryan, to be his running mate, making his the weakest ticket on foreign policy for decades.

What is even more perverse is that Romney himself chose to go off message. Instead of hammering Obama on the economy, he decided to come out to call the administration’s alleged failure to deliver a more forceful repudiation of the attacks on four Americans in Benghazi “disgraceful.” The result is that foreign policy will now dominate the airwaves even more than it would have without Romney’s provocation. It also means that foreign policy will figure more in the upcoming debates than it would have, and Paul Ryan and Mitt Romney, who know a lot more about economics than war, will have plenty of opportunity to trip up against Joe Biden and Barack Obama.

This is a continuing pattern of a campaign in constant search of an attack strategy that would work, one that willingly goes off message because for whatever reason, the message isn’t working. A merely reactive campaign waiting on the sidelines to jump on a mistake cannot have a coherent message.

The fact, anyway, is that President Obama is far more vulnerable on his economic record than he is on foreign policy. Yet he is not vulnerable enough. And this is the dilemma that the Romney team has not been able to resolve in the last couple of months. Each time they have tried a new message other than the economic declension narrative on the national debt and unemployment, they have had to ease up on the only strategy that has worked, but only to an insufficient degree. They are stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Infusing foreign policy into the campaign, however, is particularly counter-productive for the Romney campaign because foreign policy is a very poor fit with their existing economic message, unlike say healthcare reform / repeal. This is why the RNC convention barely talked about foreign policy. When voters are uncertain about their economic future, they have historically been prepared to take a leap of faith in a challenger candidate. But when voters are uncertain about global unrest, they have tended to stay the course with the incumbent. Further, Obama’s likability numbers translate most easily into his role as Commander-in-Chief. This is not an area on which he could be easily challenged, however loudly the voices of a minority in the Republican Party suggest otherwise.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

When “Stuff happens.”

The killing of US Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other American diplomats in Benghazi, Libya on 11 September 2012 serves as a vivid reminder that unexpected events often intrude on presidential elections. Sometimes these events have a significant impact on how voters view the parties and the candidates. But often the electorate shrugs off breaking news. As former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld famously put it, “Stuff happens.” For most incidents, polls might record a brief hiccup, but then voters settle back into their previous distribution of preferences. The only events that prove consequential either validate a story that one side has been telling, let one candidate appear more presidential, or suggest that a candidate lacks core presidential attributes.

Campaigns try to construct a narrative about the national condition that work to their advantage, and events may give that tale greater popular traction. As the noted historian William Gienapp explains in his study of the rise of the Republican Party in the 1850s, the new party struggled for several years to establish itself as the leading opposition coalition to the dominant Democrats. The Whig Party had suffered a stunning defeat in 1852, opening space for another major challenger. Yet in some states the Whigs refused to slink off into oblivion. Meanwhile, the American Party (sometimes called the Know Nothings) also vied to become the principal opposition, fueled by public concerns about immigration and the alleged threat it represented to American values. For many former Whigs, the Republican preoccupation with the westward expansion of slavery seemed to be of marginal relevance. Heading into the critical 1856 presidential election, then, it was not clear which opposition party — Whig, American, or Republican — would emerge as the strongest.

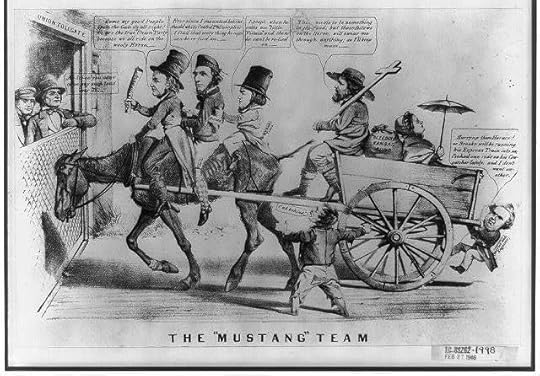

Then came what Gienapp calls the “spring breakthrough,” a set of events that seemed to affirm the Republican view. Republicans spoke of “slave power conspiracy” that had subverted American democracy by placing Southern interests ahead of national ones. On 21 May 1856, pro-slavery militants in Kansas attacked and sacked the town of Lawrence, an anti-slavery stronghold. Just one day later, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, a staunch abolitionist, was brutally caned while delivering a speech on the Senate floor by South Carolina Representative Preston “Bully” Brooks. Republicans adroitly wove together the two events — “Bleeding Kansas” and “Bleeding Sumner” — as proof of what the party had been warning about all along. The question of slavery reclaimed top billing among the opposition concerns, and the Republicans rode the wave to a strong showing in the 1856 election that established their party as the foremost challenger to the Democrats.

The "mustang" team (the abolitionist Republican presidential ticket and its supporters in the press). Cartoon by Louis Maurer, 1856. Source: Library of Congress.

Americans expect a president to be strong, not overly bellicose. On 2 August 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats and a US Navy destroyer exchanged fire in the Tonkin Gulf, followed by a report (later retracted) of a second incident. Lyndon Johnson sought and received authorization from Congress for a military response. Within days of the approval of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, American aircraft struck the torpedo boat bases and other facilities in North Vietnam. The Tonkin Gulf incident and its aftermath played directly into the president’s hands during his 1964 campaign against Barry Goldwater. Public support was strong for both the Resolution and the administration’s measured military response. Johnson demonstrated firmness against communist provocations, yet he avoided the appearance of recklessness that dogged his opponent. As for what he might do in Southeast Asia following his election, Johnson chose his words carefully to avoid any commitments.

Events also cause candidates to put on display certain character traits, breaking through the careful choreography of the modern campaign with its tightly controlled scripts. The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 turned out to be just such a moment. In the wake of the debacle and the chain reaction it set in motion on Wall Street, Senator John McCain abruptly announced he was suspending his campaign and returning to Washington until the crisis was addressed. He intended to send a message of decisive leadership. What came across instead was a powerful impression of a candidate who acted impulsively, even rashly. Coming on the heels of the dreadful interviews given by his hastily-chosen running mate, Sarah Palin, McCain’s “Lehman Moment” fed a media narrative that he lacked the steadiness for the presidency.

Most events, though, fail to alter the trajectory of the presidential campaign. Instead they reinforce existing perceptions on both sides. The recent disappointing jobs report serves as a case in point. Americans have already made their judgment about the economy, whether they believe the president is to blame for the sluggish recovery (Romney supporters) or see him coping with the challenge as well as anyone could (Obama backers). Only a succession of extraordinary economic results at this late stage might unsettle these evaluations. A single jobs report that largely confirms what people already know won’t do it.

We will learn in the next several weeks whether Mitt Romney’s quick condemnation of the administration reshapes the election. His reaction will not reinforce a story about American international weakness because his campaign has not stressed that narrative theme to this point. On the other side, the episode may help the president. The attacks let Barack Obama do one thing that every president seeking reelection wants to do — present himself as the leader of the American people, not just a partisan standard bearer. And the haste with which Romney sought to turn the tragedy to political advantage may feed a very damaging media narrative that depicts him as relentlessly opportunistic and unprincipled.

If that happens, the Republican may rue his decision not to do what Ronald Reagan did when a failed mission to free the American hostages in Iran in April 1980 resulted in the death of American military personnel. Reagan chose to offer his condolences and call on Americans to pray for the families who had lost loved ones. Sometimes the smart political move is not to look for political advantage.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Is America an empire?

Empire State Building. Photo by robertpaulyoung, 2005. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The intense controversy that this question engenders is remarkable. On the left, critics of assertive American foreign, military, and economic policies depict these policies as aggressively immoral by branding them “imperial.” On the right, advocates for an even more forceful application of American “hard power,” such as Niall Ferguson and the other members of his self-described “neo-imperialist gang,” argue that the United States should use its immense wealth and military might to impose order and stability on an increasingly chaotic world. The two positions appear to be polar opposites, but they both assume that the United States is in fact an empire. One faction argues that imperial hard power can be put to just and humane uses, while the other sees empires as inherently illegitimate and malevolent. And both sides tend to use the Roman Empire as a cautionary reference point in arguing over whether the “American Empire” is likely to fall.This debate is pointless and ahistorical. The United States is not an empire because, quite simply, there are no empires any more. By strict definition, empire meant the overt, formal, direct, and authoritarian rule of one group of people over another. Empires ruled permanently different and disenfranchised subjects, while the populations of twenty-first century nation states are, at least in theory, rights-bearing citizens. Many of these contemporary states encompass communities that have their own frustrated nationalist ambitions, but no modern government would cite empire as their reason for denying separatist groups the right of self-determination. Doing so would be an open admission of tyranny. Empire became so stigmatized over the course of the twentieth century, particularly after the 1960 United Nations resolution 1514 (XV) labeled foreign imperial rule “a denial of fundamental human rights,” that no power would admit to being one.

But there is more to the institutional demise of formal empire than the nuances of nomenclature or Cold War politics. The main reason that the United States is not an empire is because formal imperial rule is no longer possible in the transnational and increasingly interconnected contemporary world. In earlier times, when most people’s perspectives rarely extended beyond family and village, conquerors built viable and inexpensive empires by using the members of one subject community to govern and police another. The industrial revolution, which produced a sharp but temporary imbalance in global political, economic, and technological advancement, allowed western powers to acquire African and Asian empires on the cheap. But these were short-lived empires because the experience of direct, and most often oppressive, foreign rule broke down the highly localized and parochial forms of identity that were essential to imperial stability and longevity. Imperial administration required local allies, but empire was no longer possible once participation in such a system became treasonous collaboration. Moreover, the ease with which capital, migrants, weapons, and unifying ideologies now flow around the globe mean that conquered populations have the tools to thwart formal imperial rule.

So if there are no more formal empires, then why is the “American Empire” debate so pervasive and controversial? After the 2001 terror attacks, neo-conservative hawks and their academic allies made the case for invading Iraq by claiming that the supposedly liberal French and British Empires of the twentieth century showed that it was possible to use hard imperial power to “reform” and “modernize” non-western societies. This argument contained a strong current of western cultural chauvinism that was doubly appealing to rightwing thinkers, for the only way that European empire builders could reconcile their African and Asian conquests with western liberal ideals was to portray their subjects as backwards and in need of moral uplift. On the left, the opponents of the Iraq War and American unilateralism predictably reject these stereotypes, but they also hold fast to their own imperial stereotypes. Drawing on empire’s Cold War connotations, they deploy empire as an attack word to cast American policy as imperial, and thus immoral. In this sense empire loses it original historical meaning and becomes a banal metaphor for bad behavior or the deployment of hard power.

The utility and versatility of these various imperial metaphors lead both camps to react angrily to suggestions that there is no American Empire. The resulting crossfire obscures the risks of making policy on the basis of ahistorical clichés. While George Bush emphatically declared that the United States did not “seek an empire” in Iraq, his belief in the transformative power of imperial rule and the assumption that it was still possible to rule an unwilling population for an extended period of time proved disastrous.

Furthermore, the critics and defenders of American unilateralism both confuse formal empire, which belongs to an earlier age, with “informal empire” or hegemony (from the Greek hegemon, meaning preeminence or leadership). This exercise of influence and privilege without expense of conquest and direct rule remains a viable instrument of foreign policy. It was the basis of Britain’s global preeminence in the nineteenth century and the potency of the American Monroe Doctrine in Latin America. While the United States and Great Britain occasionally used military force to demonstrate their power to friend and foe alike, they were sufficiently confident in their power to resist the temptation of turning conquests into formal and permanent rule. Debates over the existence of an American Empire obscure the reality that, at least in the modern era, formal empire was an expression of insecurity and weakness.

Timothy Parsons is a Professor of African History at Washington University. He is the author many books, including The Rule of Empires: Those Who Built Them, Those Who Endured Them, and Why They Always Fall; The British Imperial Century, 1815-1914: A World History Perspective; and The 1964 Army Mutinies and the Making of Modern East Africa.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

New term / New season

It’s September, which means back-to-school in the world of education, but for classical music it’s a different start — that of the 2012-13 opera season. In the old days opera was a grand affair; the first night of a production meant black tie and opera cloaks. These days its far more relaxed, and you won’t be frowned upon if you’re wearing jeans at the Royal Opera House. Opera is loosening up and presenting itself in ways which are less daunting for the newcomer, while maintaining the high standards that keep people coming back season after season.

Two UK opera companies, who are excellent examples of this trend, are showing Oxford University Press works this season: English National Opera (ENO) and Glyndebourne Opera. English National Opera will show Vaughan Williams’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and will use OUP’s English translation for their production of Handel’s Julius Caesar. The film of Glyndebourne’s award-winning 2005 production of the same Handel opera will be shown throughout the UK this autumn.

Two UK opera companies, who are excellent examples of this trend, are showing Oxford University Press works this season: English National Opera (ENO) and Glyndebourne Opera. English National Opera will show Vaughan Williams’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and will use OUP’s English translation for their production of Handel’s Julius Caesar. The film of Glyndebourne’s award-winning 2005 production of the same Handel opera will be shown throughout the UK this autumn.

English National Opera has a strong commitment to showing the best of English Opera, and their production of The Pilgrim’s Progress follows two previous stagings of Vaughan Williams’s operas – the light-hearted Sir John in Love in 2006 and the tragic Riders to the Sea in 2008. The Pilgrim’s Progress hasn’t been fully-staged in the UK since its premiere in 1951 at the Festival of Britain, so this new production — in what feels like another festival year for the UK — will be an exciting event for November 2012. The story of the opera follows the trials and tribulations of a Pilgrim on his journey ‘from this world to that which is to come.’ English National Opera prides itself on its young audience profile and accessible ticket prices, and to extend the reach of the music still further, the BBC will broadcast one of the evening performances live on Radio 3.

English National Opera’s policy is to always singing in English and their production of Handel’s Julius Caesar, although originally composed in Italian, is no exception. The company firmly believe that removing the language barrier opens opera up for new audiences. Glyndebourne Opera takes a different approach to this issue — always singing in the original language. That they are showing the same opera, in the same season, makes a fascinating contrast. Glyndebourne will show Handel’s Julius Caesar/Giulio Cesare in its original Italian, but will remove the sometimes daunting prospect of the imposing Opera House facade by showing their version on film. It will be in selected cinemas across the UK in October and November 2012. Filmed in 2005, Glyndebourne’s production of Guilio Cesare is a stylish and sumptuous opera which veers between dark comedy and tragedy, all wonderfully staged in a production which drew inspiration from the British Raj and Bollywood.

A clip from Handel’s Giulio Cesare via Opus Arte

Click here to view the embedded video.

Danielle de Niese in Giulio Cesare

Click here to view the embedded video.

Whether you prefer your opera in grand locations or your local cinema, in the original language or in translation, there’s something for everyone in 2012-13.

Anwen Greenaway is a Promotion Manager in Sheet Music at Oxford University Press. Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about Handel’s Julius Caesar (Giulio Cesare) sheet music on the

View more about Vaughan Williams’s The Pilgrim’s Progress sheet music on the

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition.

Image credits: (1) Masks with the theatre concept. Image by Elnur, iStockphoto. (2) Usher, opens red theater curtiain revealing stage lighting…some visible noise in background. Image by joshblake, iStockphoto.

September 17, 2012

Occupied by Images

Media buzz about Occupy Wall Street’s first anniversary began by summer’s end. That colorful, disbursed social movement brought economic injustice to the center of public debate, raising questions about free-market assumptions undergirding Wall Street bravado and politicians’ pious incantations. Most watched from the sidelines, but polling had many cheering as citizens marched and camped against the corrosive consequences of an economically stacked deck. Media fascination with Occupy was easily explained: the movement offered inventive, boisterous activism — think ballet atop the bronze bull statue in the Financial District’s heart — and sensationalism, with pepper-spraying police. Coverage was giddy and censorious. Many outlets and editorialists denigrated protesters’ naiveté, painted them as anarchic or as public dependents whose theatrics sapped limited public resources.

Three-quarters of a century before, another group of men and women’s quest for economic justice grabbed national headlines. From September 1936 through May 1937, a half-million workers, including Detroit hotel maids, Hershey chocolate workers, and Times Square movie projectionists sat down on their jobs and demanded unions to better their economic lot. Workers’ epic struggle to achieve security and the explosion of visual imagery in the news, two twentieth-century social and cultural transformations, neatly coincided, feeding each other in unrecognized ways.

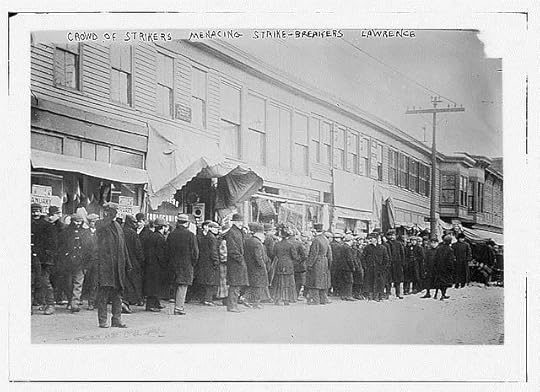

Crowd of strikers menacing strike-breakers, Lawrence (1912): Bain News Services, Call Number: LC-B2-2369-13. P&P

Labor activism had always been good copy. The expression “If it bleeds it leads” describes press coverage of labor activism from the late nineteenth century. State and local authorities often perceived union drives as anti-American and repressed them; corporations even employed in-house spies and thugs, Henry Ford’s pugilist Harry Bennett being perhaps the most infamous. As early as the 1892 Homestead steel strike, photographs were reworked as engravings for Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Press. The Graflex and the Speed Graphic cameras came later and facilitated a photographic news, as did photo agencies like Bain’s or Brown Brothers. Major confrontations between labor, such as the 1910 strike of Philadelphia trolley workers or the 1912 Lawrence, Massachusetts “Bread and Roses” strike now arrived in the pages of the Literary Digest, American Magazine, or Collier’s. The “social photography” tradition, embodied in Lewis Hine’s child labor photographs, was also found in middle-class journals. In McClure’s, articles about mining families faced with industrial disasters or working girls’ tight budgets, accompanied by documentary-style photographs, lent credence to narratives of working-class adversity. The rise of tabloids and of the rotogravure press, both in 1919, enhanced newspaper’s use of photos. That same year, when one in five workers struck, news readers could see Harvard boys with cocked guns poised to respond to Boston strikers and parading Gary, Indiana steel strikers. Even so, using photo-critic John Szarkowski’s term, news photography was “slow.”

As with Occupy, shifting technologies altered the news, and by the 1936-1937 sit-down wave photographs reached a nationwide news audience with speed. AP perfected its wire transmission system for photographs in 1935, and “for the first time in history the news picture and the news story rode the wires together,” according to one press photography text. Faster film and light-weight cameras also allowed photographers to wade into the thick of events. LIFE magazine’s “all seeing eye with a brain,” born in 1936, furthered the move to an image-saturated news. When late that year GM autoworkers in Flint, Michigan decided to sit down, Americans’ visual entrée to labor’s uprising was near immediate. Millions of Americans could see the same pictures of labor duking it out with police or corporate security.

Some media outlets seemed caught up in all the activism, celebrating it as a fad. The sit-down was LIFE’s top story in 1937. Its photo-spread on Detroit Woolworth strikers showed them bedded down on retail counters, and sliding down the store’s banisters in their “LIFE Goes to a Party” feature. But coverage also condemned. News photographs showed workers downed by tear gas, billy clubs, and even bullets — but captions and stories frequently blamed strikers for such violence. The National Association of Manufacturers capitalized on news photography’s pull, promoting a plan to foment disorder and capture photos that would, in the words of “King of Strikebreakers,” Pearl Bergoff, make unionists appear the aggressors and connect corporations to “America, free land and all that stuff.” Business often succeeded, though labor foiled such a campaign in the Chicago Memorial Day Massacre

Media coverage of labor’s mobilization provoked more activism — much as the Occupy camps, which began in Zucotti Park, a sliver of New York real estate, spread to 900 cities across the globe. Auto workers derived their 1936 sit-down tactic from Toledo workers. Following them was an avalanche. The Committee of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was inundated with requests for charters. Transit workers, pencil makers, golf-ball producers, char women, lunch delivery boys, pie bakers, glassmakers, bed-makers — all sat down to gain the upper hand with their bosses. Even regions and companies with long histories of resistance to unions saw workers rise up. In Central Pennsylvania workers were well familiar with the anti-union tactics of the steel and mining industries. One Italian immigrant had tried to bring the Wobblies to Hershey, Pennsylvania’s chocolate paradise after the Lawrence strike, but workers flinched. In the 1930s, riled up by images of sit-down successes, Hershey workers embraced the novel tactic.

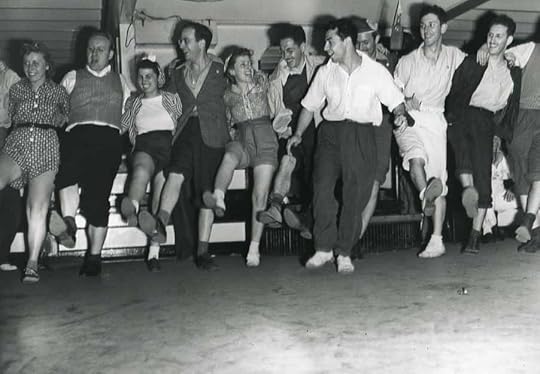

Occupiers seized on new digital technologies like video streaming and Twitter to announce their presence. Similarly, the labor movement remade a stodgy labor press filled with “grab and grin” shots of union leaders shaking hands with local luminaries. Crucial to the new labor journalism that reached nearly thirty million Americans by WWII’s end were photographs. One union even started a camera club. Local 65 United Wholesale and Warehouse Employees Union began in 1933 as a handful of white goods warehouse workers on Manhattan’s Orchard Street, but by the 1950s it had become the city’s second largest union. Its location in New York City — the nation’s publishing capital and the heart of the Popular Front — sensitized members to photography’s punch. Internationally-known photographers from the Photo League, such as Sid Grossman and Robert Capa even hung out in the union’s darkroom. Local 65 cameramen and women followed members to the streets for their picket lines, but also to their Madison Square Garden theatre performances, to the union’s penthouse nightclub, and to its Hudson River boat trips, in keeping with an organizing strategy that melded shop floor, community, and cultural activism. Even unions with less rank-and file vitality, for example the United Steel Workers of America, one of the nation’s largest unions, developed a new “mass production journalism” that illustrated in pictures the security unionization could provide.

The Fighting 65: union members kicking up their heels at the warehouse workers' union's annual Hudson River boat trip--taken by a rank-and-file camera club member. Photo courtesy of United Automobile Workers of America, District 65 Photographs Collection, Tamiment Library, New York University.

Battles over labor’s status in U.S. society took place in corporate boardrooms, at factory gates, in D.C. congressional corridors, and also in the pages of an increasingly visual mass media. Photographs re-imagined workers as part of the mainstream, but constricted labor’s promise by making strikes seem disruptive and promoting individual, private gains over collective solidarity. Today less than twelve percent of all American workers belong to unions. Organized labor pulled many out of poverty, allowing workers to conceive of themselves as middle-class. Labor’s dwindling power, including its precipitous decline since the 1980s, corresponds with growing economic inequality — hence Occupy. Its message, and its image, will have consequences.

Carol Quirke is an Associate Professor of American Studies at SUNY Old Westbury. She is the author of Eyes on Labor: News Photography and America’s Working Class. She has published essays and reviews in the American Quarterly, Reviews in American History, and New Labor Forum. She is a former community organizer, who worked on economic justice, immigrant rights, and public housing issues before receiving her Ph.D. in U.S. History.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The garbled scholarship of the American Civil War

How can we frame a discussion? What terminologies give us a basis for common understanding? While many deplore arguing semantics, it is often essential to argue the meaning of words. Scholars aren’t immune to speaking to opposite ends when they don’t share common definitions. The American Civil War does not lack for books, but they aren’t all talking on the same terms. For example, what do we mean by “strategy”?

“Strategy” — located in the precise middle of this inverted pyramid — is only a piece of the puzzle that is warfare, the most confusing and complex of human endeavors, and cannot be studied apart from its critical accompanying factors. The most important of these is “policy,” meaning the political objective or objectives sought by the governments in arms (these are sometimes described as “war aims”). Policy should inform strategy, provide the framework for its pursuit, but not dictate it. It is the goal or goals sought by the antagonists. The term “policy” is often used when what is really being discussed is “strategy” or “operations.” Civil War leaders often spoke of “military policy,” when today we would translate their words as “military strategy” or “operational warfare,” depending upon the context. “Strategy” defines how military force is used in pursuit of the political goal.

“Strategy” — located in the precise middle of this inverted pyramid — is only a piece of the puzzle that is warfare, the most confusing and complex of human endeavors, and cannot be studied apart from its critical accompanying factors. The most important of these is “policy,” meaning the political objective or objectives sought by the governments in arms (these are sometimes described as “war aims”). Policy should inform strategy, provide the framework for its pursuit, but not dictate it. It is the goal or goals sought by the antagonists. The term “policy” is often used when what is really being discussed is “strategy” or “operations.” Civil War leaders often spoke of “military policy,” when today we would translate their words as “military strategy” or “operational warfare,” depending upon the context. “Strategy” defines how military force is used in pursuit of the political goal.

Military strategy is the larger use of military force in pursuit of a political objective. Some examples include implementing blockades, attrition (wearing down your enemy’s forces), exhaustion (depleting his will and/or ability to fight), a Fabian approach (protracting the war by avoiding a decisive battle and preserving one’s forces), and applying simultaneous pressure at many points. Military power is but one of many tools nations use to achieve their political objectives. To pursue their goals in wartime states tap their economic, political, and diplomatic resources. These non-military components are sometimes lumped under the rubric of “Soft Power.” All of these (including military strategy), are therefore elements of “Grand Strategy.”

Ideally, once strategy is determined, it is then executed, and we link to strategy’s indispensible second, the operational level of war. “Operations” are what military forces do in an effort to implement military strategy. The conduct of these operations is known as “operational art” or “operational warfare,” or, if one prefers, “operational strategy.” While no one from the Civil War era would have been familiar with this exact terminology, many of the better commanders thought and fought according to this hierarchy. Though most called their operations “campaigns,” they often understood the link between the operational and strategic levels of war.

“Tactics” govern the execution of battles fought in the course of operations. In a great deal of military literature “tactics” and “strategy” are used interchangeably, and indiscriminately, even though they differ starkly.

The framework I’ve sketched offers a canvas upon which to outline the policy, strategy, and operations — and their interconnection — of the Civil War, one derived from more than a dozen years of experience teaching various versions of the U.S. Naval War College’s Strategy and Policy course. But why does this matter? It is important because when one examines a subject one should understand the basis of the discussion. The terms above give us the basis.

Battles are imperative in any study of war, including the American Civil War, but mainly as the result of larger strategic and operational efforts for prosecuting the war. The smoke of rifles and the gleam of bayonets is one thing, but the thought process of Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis in the prosecution of the war is another. How a battle was fought is the realm of tactics. Why a battle was fought is the purview of strategy.

Donald Stoker is Professor of Strategy and Policy for the U.S. Naval War College’s program at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. He is the author of The Grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Military terminology pyramid created by Donald Stoker.

How will US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan affect Central Asia?

Earlier this summer, NATO leaders approved President Obama’s plan to end combat operations in Afghanistan next year, with the intention of withdrawing all US troops by the end of 2014. The war in Afghanistan, which begun in 2001 as a response to the events of September 11, has turned Central Asia into one of the most volatile regions in the world, with the US, Russia, and China all vying for influence among the former Soviet republics.

In the video below and an op-ed in the New York Times on Wednesday 22 August 2012, Alexander Cooley, author of the new book Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia, explains the geopolitical consequences of the troop withdrawal.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Alexander Cooley is the Tow Professor for Distinguished Scholars and Practitioners in the Department of Political Science at Barnard College, Columbia University. His books include Contracting States, Logics of Hierarchy, and Base Politics. Follow him on Twitter at @cooleyoneurasia. Read his previous blog post “Afghanistan’s other regional casualty.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The mathematics of democracy: Who should vote?

An interesting, if somewhat uncommon, lens through which to view politics is that of mathematics. One of the strongest arguments ever made in favor of democracy, for example, was in 1785 by the political philosopher-mathematician, Nicolas de Condorcet. Because different people possess different pieces of information about an issue, he reasoned, they predict different outcomes from the same policy proposals, and will thus favor different policies, even when they actually share a common goal. Ultimately, however, if the future were perfectly known, some of these predictions would prove more accurate than others. From a present vantage point, then, each voter has some probability of actually favoring an inferior policy. Individually, this probability may be rather high, but collective decisions draw information from large numbers of sources, mistaking mistakes less likely.

To clarify Condorcet’s argument, note that an individual who knows nothing can identify the more effective of two policies with 50% probability; if she knows a lot about an issue, her odds are higher. For the sake of argument, suppose that a citizen correctly identifies the better alternative 51% of the time. On any given issue, then, many will erroneously support the inferior policy, but (assuming that voters form opinions independently, in a statistical sense) a 51% majority will favor whichever policy is actually superior. More formally, the probability of a collective mistake approaches zero as the number of voters grows large.

Condorcet’s mathematical analysis assumes that voters’ opinions are equally reliable, but in reality, expertise varies widely on any issue, which raises the question of who should be voting? One conventional view is that everyone should participate; in fact, this has a mathematical justification, since in Condorcet’s model, collective errors become less likely as the number of voters increases. On the other hand, another common view is that citizens with only limited information should abstain, leaving a decision to those who know the most about the issue. Ultimately, the question must be settled mathematically: assuming that different citizens have different probabilities of correctly identifying good policies, what configuration of voter participation maximizes the probability of making the right collective decision?

It turns out that, when voters differ in expertise, it is not optimal for all to vote, even when each citizen’s private accuracy exceeds 50%. In other words, a citizen with only limited expertise on an issue can best serve the electorate by ignoring her own opinion and abstaining, in deference to those who know more. Mathematically, it might seem that more information is always better, if only slightly. This would indeed be the case, except that each vote takes weight away from other votes, which may be better informed.

It turns out that, when voters differ in expertise, it is not optimal for all to vote, even when each citizen’s private accuracy exceeds 50%. In other words, a citizen with only limited expertise on an issue can best serve the electorate by ignoring her own opinion and abstaining, in deference to those who know more. Mathematically, it might seem that more information is always better, if only slightly. This would indeed be the case, except that each vote takes weight away from other votes, which may be better informed.

If voters recognize the potential harm of an uninformed vote, this could explain why many citizens vote in some races, but skip others on the same ballot, or vote in general elections, but not in primaries, where information is more limited. This raises a new question, however, which is who should continue voting: if the least informed citizens all abstain, then a moderately informed citizen now becomes the least informed voter; should she abstain, as well?

Mathematically, it turns out that for any distribution of expertise, there is a threshold above which citizens should continue voting, no matter how large the electorate grows. A citizen right at this threshold is less knowledgeable than other voters, but nevertheless improves the collective electoral decision by bolstering the number of votes. The formula that derives this threshold is of limited practical use, since voter accuracies cannot readily be measured, but simple example distributions demonstrate that voting may well be optimal for a sizeable majority of the electorate.

The dual message that poorly informed votes reduce the quality of electoral decisions, but that moderately informed votes can improve even the decisions made even by more expert peers, may leave an individual feeling conflicted as to whether she should express her tentative opinions, or abstain in deference to those with better expertise. Assuming that her peers vote and abstain optimally, it may be useful to first predict voter turnout, and then participate (or not) accordingly: when half the electorate votes, it should be the better-informed half; when voter turnout is 75%, all but the least-informed quartile should participate.

An important caveat of Condorcet’s probability analysis is that disagreements are actually illusory: if voters envisioned the same policy outcomes, they would largely support the same policies. Whether this is accurate or not is an open philosophical question, but voters seem implicitly to embrace this assumption when they attempt to persuade and convert one another via debate, endorsements, or policy research: such efforts are only worthwhile if an individual expects others, once convinced, to abandon their former policy positions, in favor of her own. Some policies also do receive overwhelming public support.

If Condorcet’s basic premise is right, an uninformed citizen’s highest contribution may actually be to abstain from voting, trusting her peers to make decisions on her behalf. At the same time, voters with only limited expertise can rest assured that a single, moderately-informed vote can improve upon the decision made by a large number of experts. One might say that this is the true essence of democracy.

Joseph C. McMurray is Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at Brigham Young University. His recent paper, Aggregating Information by Voting: The Wisdom of the Experts versus the Wisdom of the Masses, has been made freely available for a limited time by the Review of Economic Studies journal.

The Review of Economic Studies is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journals. The Review is essential reading for economists and has a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers in theoretical and applied economics.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only mathematics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Voting card. Photo by rrmf13, iStockphoto.

September 16, 2012

Nouvelle Cuisine in Old Mexico

Mexican cuisine has experienced a renaissance in the past few decades. In the United States, taco trucks and immigrant family restaurants have replaced Americanized taco shells and chili con carne with Oaxacan tamales and carne asada. Meanwhile, celebrity chefs have embraced Mexican food, transforming it from street food into fine dining.

In Mexico, exclusive restaurants once served French cuisine more often than national dishes, but beginning in the 1980s, chefs created the nueva cocina mexicana in order to reinvent traditional dishes for an upscale clientele of local notables and well-heeled tourists.

Inspiration for this gourmet movement came partly from the French nouvelle cuisine and partly from the glories of the Maya and Aztec empires. Not only did these ancient civilizations hold a romantic appeal, but also they embodied the nationalist ideology of “indigenismo,” which sought to revitalize Mexico’s indigenous heritage. Muralists such as Diego Rivera portrayed Indian heroes in monumental paintings, while archaeologists restored the pyramids of Teotihuacán and Chichén Itzá as tourist attractions.

The founders of the nueva cocina had mixed backgrounds. Some were working-class cooks from the countryside who presented the festival foods of their home communities to Mexico City diners as exotic relics of the indigenous past. For example, Fortino Rojas at Restaurante Chon is credited as the inventor of the pre-Hispanic menu. Others were cosmopolitan aristocrats such as Patricia Quintana, who trained in French kitchens and studied the native codices (sixteenth-century documents) to create menu items for her celebrated restaurant, Izote.

Yet there was an earlier version of the nueva cocina in Mexico, just as French cuisine has passed through multiple revolutions. Already in 1742, the chef known as Menon published a cookbook called Nouvelle Cuisine, which sought to simplify the artifice of medieval cuisine, with large joints of roast or boiled meats and complex spice mixtures. Menon and his colleagues established the modern French model of smaller cuts of meat, sautéed and served with a sauce of emulsified pan drippings.

Mexico’s first published cookbooks, from the 1830s, also offered what could be called a nueva cocina, which represented a curious mix of old and new, European and American. In some ways, it was closer to medieval cooking than to the new French cuisine, and it advanced a national identity that was more criollo (creole) than indigenista.

Criollos, people of European ancestry born in the Americas, formed the elite of colonial Mexico. Nevertheless, the Spanish Crown denied them political authority and instead ran the empire through viceroys and administrators parachuted in from the Iberian peninsula. Criollos therefore developed an identity distinct from their European-born cousins and rivals. These New World patriots considered themselves not the offspring of conquistadors but rather the heirs to the ancient Aztec emperors, and therefore the legitimate rulers of Mexico. Nevertheless, they looked down on living Indians as their social inferiors.

Consider the following criollo menu from the nineteenth-century: guacamole (avocado salad), mole de guajolote (turkey in chile sauce), and chiles rellenos (stuffed chiles). All of these dishes had pre-Hispanic antecedents, yet the recipes transformed indigenous ingredients with European techniques and tastes. (All recipes can be found below.)

Start with the guacamole. Today the dish features avocado, tomato, onion, chile, and cilantro, all mashed up in a sauce or mole, which comes from the Nahuatl word molli. Some fancy restaurants prepare guacamole tableside in rustic molcajetes (basalt mortar and pestle). Yet the criollo recipe is a distinctly European salad, dressed with oil and vinegar.

Next comes the main course, mole de guajolote. This will also probably come as a surprise, even to those familiar with Mexican cuisine. Today, it is considered to be mestizo dish, or a mixture of Indian and Spanish traditions. The turkey and chile peppers are from the New World, while the spices are from the Old. Yet this criollo recipe harkens back to medieval Spain not only with the complex spice mixture but also through the appearance of ham shanks and pork loin alongside the turkey.

Most interesting of all is the dessert, conservas de chiles rellenos (candied stuffed chiles), made by simmering green chiles in sugar syrup and then stuffing them jam. Although this recipe appears trendy enough for any postmodern dessert menu of the nueva cocina mexicana, it also recalls the convents of colonial Mexico, which carried on the medieval Arabic traditions of custards and candied fruits.

These three criollo recipes are quite different from the dishes of the same names that are widely eaten in Mexico today. But however strange they may appear, they also have surprising similarities with the nueva cocina of today. One could argue that culinary indigenismo is an updated version of nineteenth-century criollo cooking, combining references to the ancient Aztecs and Maya with European cooking techniques.

Avocados in guacamole.

Peel and seed the avocados, chop with a knife of silver or wood — metal gives them a bad taste and bad color — arrange on a plate and serve with oil, vinegar, onion, oregano, and chile ancho. There are persons who mash the avocados and convert them into a paste. This dish can be eaten with all sorts of grilled meats and with stew.

Source: Vicenta Torres de Rubio, Cocina michoacana (Zamora: Imprenta Moderna, 1896), 18.

Mole de guajolote (Turkey mole)

For a large turkey, use two [ham] shanks (codillos) and a real of pork loin. [Take] two reales of chile pasilla and one real of ancho, de-vein and toast on a comal (griddle) until well browned but without burning. (Note: A real was one-eighth of a peso. In colonial Mexico, prices were quoted in reversed, listing ounces per real rather than reales per ounce.) Put a real of tomatillos on to boil. Half [a real] of clove, half of cinnamon, a few grains of fine pepper, a little toasted coriander, the amount of toasted chile seeds that can be taken with three fingers of a hand, and half of sesame seed, also toasted. Grind together the spices and the chile, sprinkling with water until it is ground, and then remove [from the metate] and put in its place tomatoes and grind the seeds well. Season this mole putting a large cazuela (cooking pot) greased with pork fat on the fire, then when it’s hot, add the [divided] turkey in regular pieces [presas] and the shank and loin. After [browning], add the chile and soaking water to fry with the meat until it begins to splatter, then add the ground tomatoes and also the soaking water, and add to the meat enough water so that it remains covered and salt. Allow to simmer until the meat softens and thickens the broth. Serve with sesame seeds on top.

Source: Novísimo arte de cocina (Mexico City: C. Alejandro Valdés, 1831), 34-35.

Conservas de chiles rellenas (Conserves of stuffed chiles)

Carefully stem and de-vein [the chiles], remove the seeds, wipe and place in salted water, change on the following day, with another that has a little added salt: after half an hour, change this and return to the first water, taking care to change [the water] as may be necessary until it loses the picante [heat]. Next put on a fire and let boil, taste, and if you perceive even a bit of picante taste, add to clear water until it is removed. Clarify sugar syrup and place on a gentle fire, add the chiles so that they are conserved. When they are well conserved, fill with candied cidra, coconut, or whatever other thing, in order to cover them afterwards with their sesame seeds and orange blossom water on top.

Source: Novísimo arte de cocina (Mexico City: C. Alejandro Valdés, 1831), 194.

Jeffrey M. Pilcher is Professor of History at the University of Minnesota. He is the author of , Que vivan los tamales!: Food and the Making of Mexican Identity; The Sausage Rebellion: Public Health, Private Enterprise, and Meat in Mexico City; and Food in World History. He also edited the Oxford Handbook of Food History.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Why do people hate teachers unions? Because they hate teachers.

Like Doug Henwood, I’ve spent the last few days trying to figure out why people — particularly liberals and pseudo-liberals in the chattering classes — hate teachers unions. One could of course take these people at their word — they care about the kids, they worry that strikes hurt the kids, and so on — but since we never hear a peep out of them about the fact that students have to swelter through 98-degree weather in jam-packed classes without air conditioning, I’m not so inclined.

Forgive me then if I essay an admittedly more impressionistic analysis drawn from my own experience.

Like many of these journalists, I hail from an upper middle class background. I grew up in Chappaqua, an affluent suburb of New York. My parents moved there in 1975 for the schools, which were — and I believe still are — terrific. From elementary school through senior year, I had some of the best teachers I’ve ever encountered.

Two of my social studies teachers — Allan Damon and Tom Corwin — had more of an impact on me than any professor I ever had in college or grad school. In their classes, I read Richard Hofstadter’s Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, E.H. Carr’s What Is History?, Michael Kammen’s People of Paradox, Hobbes, Locke, Richard Hakluyt, Albert Thayer Mahan, and more. When I got to college, I found that I was considerably better prepared than my classmates, many of whom had gone to elite private schools in Manhattan and elsewhere. It’s safe to say I would never have become an academic were it not for these two men.

We also had a terrific performing arts program. Phil Stewart, Chappaqua’s legendary acting teacher, trained Vanessa Williams, Roxanne Hart, Dar Williams, and more. We put on obscure musicals and destabilizing plays like The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. Ronald Dunn, our choral teacher, had us singing Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms, Vivaldi’s Gloria, and the works of Fauré. So inspiring were these teachers that many of us went onto organize our own plays, musicals, and a cappella groups, while we were still in high school.

Despite this, many kids and their parents held teachers in contempt. Teachers were not figures of respect or gratitude; they were incompetents and buffoons. Don’t get me wrong: like most people, I had some terrible teachers. Incompetents and worse. But like most people I’ve also had some terrible friends, some terrible co-workers, some terrible neighbors, some terrible doctors, some terrible editors, and some terrible professors. Mediocrity, I’d venture, is a more or less universal feature of the human condition. But among the upper classes it’s treated as the exclusive preserve of teachers.

It’s odd. Even if you’re the most toolish striver — i.e., many of the people I grew up with — teachers are your ticket to the Ivy League. And if you’re an intellectually ambitious academic type like me, they’re even more critical. Like I said, people move to Chappaqua for the schools, and if the graduation and post-graduate statistics are any indication — in my graduating class of 270, I’d guess about 50 of us went onto an Ivy League school — they’re getting their money’s worth. Yet many people I grew up with treated teachers as bumptious figures of ridicule — and not in your anarchist-critique-of-all-social-institutions kind of way.

It’s clear where the kids got it from: the parents. Every year there’d be a fight in the town over the school budget, and every year a vocal contingent would scream that the town was wasting money (and raising needless taxes) on its schools. Especially on the teachers (I never heard anyone criticize the sports teams). People hate paying taxes for any number of reasons — though financial hardship, in this case, was hardly one of them — but there was a special pique reserved for what the taxes were mostly going to: the teachers.

In my childhood world, grown ups basically saw teachers as failures and fuck-ups. “Those who can’t do, teach” goes the old saw. But where that traditionally bespoke a suspicion of fancy ideas that didn’t produce anything concrete, in my fancy suburb, it meant something else. Teachers had opted out of the capitalist game; they weren’t in this world for money. There could be only one reason for that: they were losers. They were dimwitted, unambitious, complacent, unimaginative, and risk-averse. They were middle class.

No one, we were sure, became a teacher because she loved history or literature and wanted to pass that on to the next generation. All of them simply had no other choice. How did we know that? Because they weren’t lawyers or doctors or “businessmen” — one of those words, even in the post-Madmen era, still spoken with veneration and awe. It was a circular argument, to be sure, but its circularity merely reflected the closed universe of assumption in which we operated.

Like my teachers, I have chosen a career in education and don’t make a lot of money. Unlike them, I’m a professor. I’m continuously astonished at the pass that gets me among the people I grew up with. Had I chosen to be a high-school teacher, I’d be just another loser. But tenured professors are different. Especially if we teach in elite schools (which I don’t.) We’re more talented, more refined, more ambitious—more like them. We’re capitalist tools, too.

So that’s where and how I grew up. And when I hear journalists and commentators, many of them fresh out of the Ivy League, talking to teachers as if they were servants trying to steal the family silver, that’s what I hear. It’s an ugly tone from ugly people.

Every so often I want to ask them, “Didn’t your parents teach you better manners?” Then I remember whom I’m dealing with.

Corey Robin teaches political science at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center, and is the author of The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin. He blogs at coreyrobin.com, where this post originally appeared.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers