Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1023

September 12, 2012

Computer programming is the new literacy

It’s widely held that computer programming is the new literacy. (Disagreement can be found, even among computing professionals, but it’s not nearly as common.) It’s an effective analogy. We all agree that everyone should be literate, and we might see a natural association between writing letters for people to read and writing programs for computers to carry out. We also find a historical parallel to the pre-Gutenberg days, when written communication was the purview mainly of the aristocracy and professional scribes. Computation is an enormously valuable resource, and we’re only beginning to explore the implications of its being inexpensively and almost universally available.

But is programming-as-literacy an appropriate analogy? We tend to think that basic literacy is achieved by someone who can say, “Yes, I can read and write.” Let’s see what this means in the context of programming.

Historically, programming has been a matter of writing down instructions for a computer to follow, a style now called imperative programming. This is trickier than giving instructions to a human being, though. You’re a human being, which means you know what others are capable of doing and what they will understand. For example, if you were writing down instructions as part of a recipe, you might say, “Place two cups of frozen peas in the microwave for six minutes.” You don’t bother to add that the microwave should be on for those six minutes, that the peas should be in a container, or that “cups” means the English measuring units rather than, say, two coffee mugs. The capabilities of a computer are less obvious, though, which makes instructions harder to write. Worse, they don’t “understand” anything at all, at least in the same sense that people do. In 1998, for example, the Mars Climate Orbiter was lost, because one programming team used English units, and another team used metric units. A reasonable person given a set of instructions for maneuvering through space might wonder, “Are we all clear on what we’re talking about?” A computer would need to be given instructions to do the same.

Other approaches to programming have emerged over the years, and they involve something different from writing instructions. In some environments programming has the flavor of creating a rulebook, as you might do for a new board game. Your rules aren’t directly concerned with the details of specific games: “If Jane rolls a four with her dice and moves her piece to a red square, then…” Instead, your rules govern the flow of a game — any game — at a more abstract level. “If a player lands on a red square, then…” You develop comparable rules when you write a spreadsheet macro. Your macro (a tiny program in itself) isn’t concerned with specific numbers, but more generally with the mathematical relationships between cells that contain those numbers. “The number in this cell is the sum of the numbers in these other cells.” Ideally, your program will work on cells that contain any numbers at all; it depends on the structure of a given spreadsheet rather than its specific contents. Thinking about how to express these rules, or constraints, is part of constraint-based programming.

Yet other kinds of programming are like writing out appropriate responses for workers in a customer service department. Such-and-such a request from a customer should be handled with this procedure; business rules behind the scenes govern what’s possible and what’s not. Programming a graphical user interface means thinking along similar lines. The application waits for a button press or a menu selection, runs the relevant procedure, and then responds. This is event-driven programming, in which each event triggers its own small program to do the right thing.

Does all this sound like literacy? I’d argue yes, that these are no less forms of literacy than being able to write a business plan, a compelling legal brief, or perhaps an evocative concrete poem. In these more familiar examples of writing, literate people are expressing themselves with knowledge of a set of underlying concepts, conventions, and goals. But we wouldn’t expect hundreds of thousands of people in any given year to try to become businesspeople, lawyers, or poets in their spare time. What makes programming special?

One answer comes from Alan Turing, the father of computer science. In 1950, he wrote:

This special property of digital computers, that they can mimic any discrete state machine, is described by saying that they are universal machines. The existence of machines with this property has the important consequence that, considerations of speed apart, it is unnecessary to design various new machines to do various computing processes. They can all be done with one digital computer, suitably programmed for each case. It will be seen that as a consequence of this all digital computers are in a sense equivalent.

It seems obvious that our everyday world can’t be shoehorned into a perspective that’s all about business or legal briefs or even poetry. But a computational perspective? The universality of computers makes the idea more promising. Konrad Zuse, a German computing pioneer, speculated in 1967 that all of physical existence might be interpreted in terms of computation, and this possibility has seen growing attention in the years since. Even if we can’t reprogram the basic principles of the universe, it’s a fascinating thought that the principles might be computational. That seems worth understanding, and learning how to program is one way to start.

If this isn’t compelling enough, we can be more practical. A few years ago, for example, I was curious whether the Democratic and Republican candidates for President used different words in their debate. I could have spent a few minutes looking for a text analysis application online and figuring how to use it, but instead I spent the time writing a small program of my own that counted unique words, ignoring the non-meaningful ones, and compared the results. This was easy, partly because I know how to program, but probably more because I’ve learned a useful set of concepts, strategies, and skills for solving computational problems. A side benefit of learning to program. The results my program generated were nothing unexpected, but after I was finished I felt a small, familiar sense of accomplishment. I’d built something new, by myself, rather than depending on what others had given me.

Literacy, even programming literacy, can be its own reward.

Robert St. Amant is an Associate Professor of Computer Science at North Carolina State University, and is the author of Computing for Ordinary Mortals, out this December from Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Lines of computer code in different languages with circuit board on the background. Image by tyndyra, iStockphoto.

The woes of Lascaux

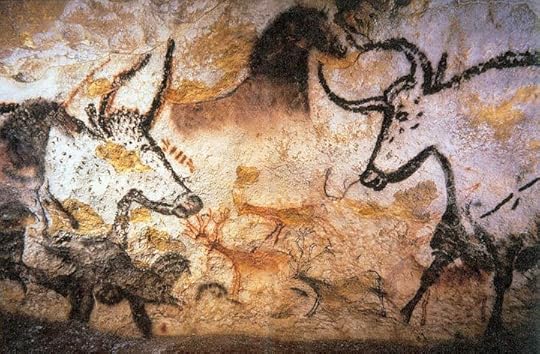

Of all decorated Ice Age caves, by far the most famous is that of Lascaux, which was discovered 72 years ago today by four boys (the hole was found by a dog on 8 September 1940, but the boys entered the cave on 12 September). It houses the most spectacular collection of Paleolithic wall-art yet found. It is best known for its 600 magnificent paintings of aurochs (wild cattle), horses, deer, and “signs,” but it also contains almost 1,500 engravings dominated by horses. The decoration is highly complex, with numerous superimpositions, and clearly comprises a number of different episodes. The most famous feature is the great “Hall of the Bulls,” containing several great aurochs bull figures — some are 5 m in length, the biggest figures known in Ice Age art.

Lascaux painting. Photo by Prof saxx, 2006. Creative Commons License. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After its discovery, Lascaux was rapidly subjected to a number of official atrocities: the widening of its entrance, the removal of its sediment without archaeological supervision, mass visitation, and the installation of an air conditioning system. The cave was closed to tourists in 1963 owing to pollution. A “green sickness” (a proliferation of algae) and a “white sickness” (crystal growth) had been noticed in the 1950s and were worsening. It was possible to reverse the effects of the algae and arrest the development of the crystals; but to ensure the survival of the cave’s art, it was necessary to drastically restrict the number of visitors and to take multiple other precautions. As compensation, a facsimile called Lascaux II was opened nearby in 1983, which permits the public to visit exact replicas of the main painted areas of the cave.

In 1999, a local firm was selected for the task of replacing the aging air conditioning equipment. It appears that they had no previous experience working in caves, and the workmen were left largely unsupervised, did not wear the sterilised footgear, and (it is said) often left the doors open. It is hardly surprising that by 2000 a new biological pollution had appeared in the cave: first a fungus Fusarium solani, characterised by white filaments, then a series of bacteria and fungi. Chemicals, while temporarily effective, could only slow the proliferation of the organisms. In 2002 France’s Ministry of Culture set up a scientific committee to tackle these problems, but very little news of its work ever reached the archaeological community, let alone the general public. The few official pronouncements were consistently optimistic, despite the terrible rumours in archaeological circles about the true state of affairs. It is known that the limitations of the chemical treatments were realized in 2003, and more sediment was removed from the cave to stop the micro-organisms from feeding off them.

What caused this sudden change in the cave? It was obvious to neutral observers that, after 40 years of stability, the shoddy work done in 1999 was to blame. Some claim that the organisms were always lurking, dormant, in the cave, and that this work merely aggravated the situation. Some have even tried to blame global warming. In any case, the responsibility lands solidly at the door of the administrators of the cave. Six different institutions have a hand in running the cave, and there seems to be little coordination.

Thanks in large measure to efforts by the International Committee for the Preservation of Lascaux (ICPL), led by French campaigner Laurence Léauté-Beasley, the true situation eventually emerged, and cave art specialists were at last able to learn the catastrophic condition of this World Heritage site. Amazingly, the scientific committee appointed by the French government didn’t feature a single rock art or cave art specialist. As the French magazine Paris Match pointed out in a ferocious article (7 May 2008), its director was inexplicably a specialist in Palaeochristian ceramics. Incredibly, the committee ignored the scientists who had cured the cave in the 1960s. It seemed that it was determined to start from scratch, and to treat the problems as if this was a new cave to be studied, playing things by ear as different factors arose. The knowledge and experience gained in the cave in the 1960s were deemed irrelevant.

The French authorities eventually organised a major conference in Paris in February 2009, advertised as a gathering of international scholars who would debate the problems of Lascaux. However, there was widespread shock when the conference programme was made public. It did not include anyone from the team who cured Lascaux in the 1960s, the ICPL, the French scholars who know the art of Lascaux best (Brigitte and Gilles Delluc, and Norbert Aujoulat) or, incredibly, a single cave art specialist. A few of the much-trumpeted international invitees from America, South Africa, Australia and elsewhere were involved in rock art research, but could contribute little to solving the very complex and unique problems of Lascaux. Under these circumstances, it is no surprise that the conference was largely irrelevant, although its deliberations were subsequently published in a lavish volume.

There was, however, one positive development: the original scientific committee was dissolved, replaced by a new one that is (theoretically) to operate independently of the non-scientific management of the cave. This met a key aspiration of the ICPL, since many of the mistakes made are seen as a direct result of managers rather than scientists making decisions about treatments of the cave. The new committee includes Spanish cave art specialists and excellent scientists. A truly independent, international group of scientists, the Lascaux International Scientific Thinktank (LIST) has also been formed, which monitors the deliberations and decisions of the official committee and offers objective information about the cave’s current condition.

Paul G. Bahn is the contributor of the popular Grove Art Online entry on Lascaux, as well as numerous other Grove articles on cave sites in France and Spain. He is the author of Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe (2nd ed. 2012, Frances Lincoln, London), and Journey Through the Ice Age (1997, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London / University of California Press, Berkeley).

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access—and simultaneously cross-search—an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Why did Milton write his theology in Latin?

John Milton wrote his systematic theology, De Doctrina Christiana, his “dearest possession,” in Latin — usual for a theological work, but with many unusual aspects.

Language was a choice, not a foregone conclusion. Continental theologians could be rendered into English (for instance, the work by Johannes Wolleb); English theologians could write in Latin (William Ames); and English philosophers could write in both tongues (Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes). So Milton chose Latin in addressing Universis Christi Ecclesiis (“the universal churches of Christ”).

The choice says much about his milieu. European education and culture were bilingual. Just as Dante used Latin to say why he wrote the Divine Comedy in the vernacular, one of the King James Version (KJV) Bible translators took his notes of their discussions of the English in Latin. Latin was the air they breathed. Milton sought a European reputation through his voluminous Latin, half his total output. When he speaks of “liberty’s defence, my noble task, / Of which all Europe talks from side to side,” that’s thanks to Latin.

The choice entails things he can and can’t say. He can avail himself of Roman eloquence and pagan allusion, or exploit the sententious brevity of Latin, its permanence and marmoreal dignitas. However, Latin can’t convey the difference between perfective and imperfective aspect (between “I write” and “I am writing”). Unlike Greek or English, the classical form of humanist Latin precludes using definite or indefinite articles. Besides being a headache for translators, Latin lumps unsubtly where splitting would be clearer and convey nuance; the same is true of patristic words.

For a theology which admits into its belief-system “solely what scripture attests,” the choice of the Junius-Tremellius-Beza (JTB) Bible needs inspection. Did he, for example, regard it as more accurate or scholarly or close to the original tongues? One teacher, Sutcliffe in 1602, recommended it for those who can’t read the original Hebrew or Greek, but stipulates that the Latin glosses and commentaries not be used. Did its voluminous notes recommend it to Milton? He does use them, and ad occasionem the Latin of the Syriac. Come to think of it, why didn’t he quote directly from the original tongues?

For a theology which admits into its belief-system “solely what scripture attests,” the choice of the Junius-Tremellius-Beza (JTB) Bible needs inspection. Did he, for example, regard it as more accurate or scholarly or close to the original tongues? One teacher, Sutcliffe in 1602, recommended it for those who can’t read the original Hebrew or Greek, but stipulates that the Latin glosses and commentaries not be used. Did its voluminous notes recommend it to Milton? He does use them, and ad occasionem the Latin of the Syriac. Come to think of it, why didn’t he quote directly from the original tongues?

Is this about readership? Did he expect his readers to read his work with the artillery of exegesis alongside? Using a later edition of the JTB (as he seems to have done) would assemble more of the full biblical materials, which indeed are the authoritative half of the evidence. The KJV provides less material, and the Geneva Bible’s materials are prejudicial.

Why didn’t he write in English? After all, he translated other people’s Latin theologies into English, for a learned clergy and many other questing spirits. These, whether within or outside the churches, are exactly the readers to whom Milton addresses himself in his ringing superscription.

So Milton’s choices include paradoxes and cross-currents. He proclaims the priesthood of all believers, in a Latin which most of them can’t read. Protestants ransack a Latin Bible, while Catholics read the Douai Bible in English. A full new edition of De Doctrina Christiana with transcription of the full and extraordinary original manuscript provides some new clues and insights.

Besides the humdrum and generic reasons, there is the negative merit of “the decent obscurity of a learned language.” Whatever “decent” means in Gibbon’s dictum, “obscurity” means it won’t get the readers it doesn’t want. I’m not being artful or anachronistic. “I am writing in Latin not English because I do not wish my words to be understood by the common people” (Latine potius scribo quam Anglice … quia quae vobis dico a vulgo nollem intelligi). Written in 1625 to attack clergy pluralism, and addressing the bishops en masse, this remark by one Theophilos Philadelphos throws a curious sidelight on De Doctrina. It was a dangerous epoch for theologians.

The waning of Latin keeps modern readers from reading Milton in his own original, chosen — often exciting or violent — words. This unlucky development deprives him even now of his “fit audience though few.” So our dearest wish is that our new edition may induce readers to venture across from the right-hand pages of the translation to the left-hand pages of the actual words of Milton, dictating to his scribes. The translation is literal and full, hence boring in itself, to encourage readers to glance across and read between. They are in for a good time. Milton is in top form, on unparalleled subjects, voicing strong opinions eloquently. In one word: enjoy!

John K. Hale holds degrees from the Universities of Oxford, Durham, Edinburgh, and Otago. He taught at the University of Manitoba before settling at the University of Otago. Besides his books and essays on Milton and Shakespeare, he has published on Aristotle, Dante, Spenser, Herbert, Bentley, Austen, and Hopkins. He writes a weekly newspaper column on language matters, ‘WordWays.’ Edited with introduction, commentary, and notes by John K. Hale, The Complete Works of John Milton: Volume VIII: De Doctrina Christiana is part of a Milton literature series and is due out in September 2012.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: John Milton, in public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

September 11, 2012

Post-mortem on the DNC Convention

The Democrats are enjoying a little bump from their convention last week, but it had little to do with Barack Obama and a lot to do with Bill Clinton. The reason why Clinton’s speech worked was because he was specifically charged to address the substance of his speech to independents and older white males. He was very successful in making his speech appear reasonable, while delivering very partisan conclusions. As such, the speech was becomingly presidential.

Obama’s speech on the other hand was predictable and tired. He seemed not to have recognized that he was in a very different position than four years ago. The language of empathy and hope falls on deaf ears when the speaker’s credibility has been tarnished. What his research team needs is a catalogue of facts, such as those presented by Bill Clinton, for making the case that the administration has made some progress on various fronts ahead of the presidential debates next month. Unlike Romney, Obama must walk a tightrope of appearing presidential when still appealing to his base. Facts, not emotions, are his best allies this time.

In the end, for better or for worse, elections are now about persons, not parties. Candidates make all kinds of promises and voters have to make their judgment calls by triangulating imperfect indices of credibility. This is why negative ads can be so damaging. But so can strategic endorsements. One of the most powerful moments in the Republican convention was when Ann Romney shed light on some of Mitt Romney’s private acts of charity.

The rest of the Democratic convention was uninspiring. The choreography of minorities conspicuously put on display and the overplaying of the abortion issue crowded out precious time that could have been spent on putting a positive spin on Obama’s record and restoring his credibility. The choice of North Carolina as the convention site was possibly also based on hubris. Most polls since May have put North Carolina in Romney’s column. The Democrats may have done better with a more defensive strategy and held their convention in states like Colorado or Virginia.

Looking ahead, the electoral dynamics are likely to change if for one reason alone. Now that Romney is the official nominee, he can dip into the RNC’s funds to add to his already formidable war-chest. He may yet be able to make up the advantage Obama enjoys in the electoral college map.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

How do you remember 9/11?

By Patricia Aufderheide

Documentary film both creates and depends on memory, and our memories are often composed of other people’s. How do we remember public events? How do you remember 9/11?

On this anniversary of 9/11, along with your own memories, you can delve into a treasure trove of international television covering the event. The Internet Archive’s “Understanding 9/11” video archive provides a record of international television news in the first week after the event, between 11-17 September 2001. (It starts about an hour before the event.) Eight international channels and 11 US channels (local and national, broadcast and cable) are available for searching, viewing and link-sharing in 30 second clips. Internet Archive made the archival material available soon after the event, and encouraged researchers to use it.

Having been out of the country (trapped for days in Canada, where a substantial portion of lower Manhattan’s population and I were grouped for the Toronto International Film Festival) for the event itself, I had missed a lot of coverage. I seized on the archive to see how my own nation’s television had covered the event while I was watching images of planes grounded on Canadian tarmac.

The theme I picked up, powerfully from Days 3-7, I called “therapeutic patriotism” in “Therapeutic Patriotism and Beyond.” I argued that TV news “assumed a public role of funeral director and mourning counselor for a nation that had, once again, had its innocence shattered.” That innocence was apparently grounded in ignorance: “A whole raft of dark new issues — Islamic fundamentalism, terrorist networks, biological warfare, diversified nuclear weaponry — suddenly seemed to fly into our range of vision just like the second airplane had on our TV sets.”

Television as therapy, I argued, was potentially expensive, because it can excuse forgetting in the name of healing:

Americans have their innocence shattered with astonishing frequency, and reconstruct it with remarkable swiftness. American innocence has been shattered, for instance, with the quiz show scandals, with the assassinations of public leaders, the Vietnam War, Iranian hostages, the Gulf War, the Oklahoma City bombing, with terrorism, computer hacking, and Y2K. And somehow it has been there to shatter again later.

This investment in our own innocence is a feature of deeply-held, widely shared, enduring values of American culture. Cultural historians and literary figures have noted among the myths of American culture the intertwined notions of American exceptionalism, a removal from the ordinary process of history, the ability to have a fresh start that wipes away the past, and anti-intellectualism that is paired with confidence in the practical and empirical. The assumption of American exceptionalism among other things exempts American citizens from perceiving the U.S. as a nation among nations, with a history of geopolitical relationships that are remembered elsewhere, and with ongoing diplomatic entanglements that preclude wiping the past away and having a fresh start. The reverence for the plain-spokenly empirical makes it easy to discount the role of ideology in shaping anyone’s worldview, especially our own.

What’s creepy, reading that at the distance of 11 years, is that television is still the nation’s amnesiac therapist. When the Aurora shooting happen, The Onion published a savage preview of the coverage to come, predicting the sentimental mourning, the calls to resist “politicization” (including discussion of gun laws), and in the words of a (fictional) interviewee, “In exactly two weeks this will all be over and it will be like it never happened.”

Since the first batch of scholarship and journalism making use of the 9/11 video archive, the archive has grown and now includes community and hyper-local video work on 9/11 as well. It’s also been enriched by conference papers and podcasts, related books, and archived websites. Tell your editor. Tell your students. Plunge in. Contribute. This resource is still a rich repository for new documentary work, of all kinds.

Patricia Aufderheide is a professor in the School of Communication at American University in Washington, D.C., and founder-director of its Center for Social Media. She received the career achievement award for scholarship from the International Documentary Association in 2006 and has served as a Sundance Film Festival juror and as a board member of the Independent Television Service. She is the author of Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction and The Daily Planet: A Critic on the Capitalist Culture Beat, among others.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only cinema and television articles on the OUPblog via via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The flatterers: Sweet-talking the American people

If there is one thing on which Mitt Romney and Barack Obama agree, it is this: We, the American people, are wonderful.

“We are the children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the ones who wanted a better life, the driven ones.” We have always been determined to “build a better life” for ourselves and our children. (Romney) “We honor the strivers, the dreamers, the risk-takers, the entrepreneurs who have always been the driving force behind our free enterprise system.” (Obama) We have the ultimate can-do spirit, “that unique blend of optimism, humility and the utter confidence that the when the world needs someone to do the really big stuff, you need an American.” (Romney)

Sometimes we go through hard times, but these never daunt us, and our leaders are quick to credit us with overcoming whatever adversity comes our way. “You did it because you’re an American and you don’t quit.” (Romney) “We don’t turn back. We leave no one behind. We pull each other up.” (Obama) Americans “haven’t ever thought about giving up.” (Romney)

There’s nothing new about this kind of political appeal, of course. And on the face of it, the rhetoric seems pretty innocuous. We should ask, though, about whether the language might have consequences for what happens after the election.

The framers of the Constitution feared the influence of demagogues in political systems that rest upon popular consent. James Madison expressed contempt for politicians (such as Patrick Henry in Madison’s home state of Virginia) who engaged in what he saw as rabble-rousing, appealing to the passions of the common people. As political scientist Jeffrey K. Tulis explains, the Constitution was designed to thwart the influence of demagogues. The system for selecting the president, for example, filtered the preferences of the public to neutralize the appeal of a popular leader.

Our image of demagogues has been shaped by politicians like Huey Long. They tend to be crude, polarizing figures whose rhetoric takes a divisive form; they single out “villains” or unpopular social groups who supposedly prey upon the people. James W. Ceaser, another political scientist, refers to these political figures as “hard” demagogues. They pander to popular fears and anxieties.

But Ceaser identifies a second type of demagogue, the “soft” variety. This one seduces the masses via flattery, extolling their virtues and their wisdom, conducting politics, as it were, by Barry White soundtrack. The soft demagogue plays on a different set of emotions than do the Huey Longs. Where the anger that undergirds hard demagoguery alarms many, the soft variety comforts and lulls the audience.

Even as political leaders court us, they hedge a bit by throwing in what might be termed “ritual disclaimers.” These are the promises of candor. For the Republicans, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie insisted that “we have become paralyzed by our desire to be loved,” so that politicians “do what is easy and say ‘yes,’ rather than to say no when ‘no’ is what’s required.” He added, “Our problems are big and the solutions will not be painless. We all must share in the sacrifice. Any leader that tells us differently is simply not telling the truth.” And the president reminded his audience, “You didn’t elect me to tell you what you wanted to hear. You elected me to tell you the truth.” But the disclaimers turn out to be empty. Christie failed to identify a single sacrifice the Republicans would impose; Obama spoke only in vague terms about cutting spending or raising taxes.

It isn’t difficult to understand why the soft demagogues cannot reconcile the messages. Flattery and pain don’t mix well. After all, if we the people have been as dedicated and selfless as our leaders tell us we are, then we cannot possibly be responsible for the mess we’re in. And if we have been so virtuous, surely we should not be asked to pay (through reduced benefits, higher taxes, or both) to clean up the situation.

The rhetoric will come back to haunt the winner, Democrat or Republican. Flattery works as a political tool, but a public that has been told only of its goodness will not understand why it should be penalized for its virtue. When the American people wake up the morning after the great political seduction, they will have a nasty hangover.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The greatest film ever made!

What is the greatest film ever made? In an attempt to answer this question the editors of the British Film Institute’s journal Sight and Sound conducts a poll of leading film critics, scholars and directors. The first poll took place in 1952, when Vittorio De Sica’s Italian Neorealist classic Bicycle Thieves (1948) was declared the winner. Sixty years later, and with nearly 850 critics, scholars and programmers contributing, the results of the 2012 poll have just been published. The greatest film is now judged to be Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), a psychological thriller about obsession, starring Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The eagerly anticipated publication of the poll has already provoked much discussion in the blogosphere. A major talking point has been the relegation into second place of Orson Welles’s masterpiece Citizen Kane (1941), which had dominated the list for the past fifty years. There has also been debate about how those polled decide which films are of the highest quality. Sight and Sound offer little by way of guidelines for their respondents but a review of the brief notes and essays written by those polled indicate that the criteria for selection that recur from one person to the next include essence (the films display something unique and particular), specificity (the films make a contribution to extending what is possible using film as an artistic medium), and maturation (the films have stood the test of time). Another criterion for selection is that the films are the work of renowned auteur directors. A number of articles published by the editors of the French film journal Cahiers du cinéma from the late 1950s celebrated the work of certain auteur filmmakers whose films displayed a stylistic consistency and coherence and offered a personal vision of the world that transcended time and place. Although very few of those polled refer explicitly to the Cahiers critics’ politique des auteurs, authorship is nevertheless central to the formation of the canon and the selection of the top ten films is heavily dependent on this way of conceptualizing film as art.

Of course, many find these criteria to be limiting in the extreme. There is distrust of the emphasis on the director, for example, especially in a medium that is predicated on creative teamwork. It is telling that the one genre film that appeared in the top ten of the 2002 poll — Stanley Doyen’s and Gene Kelly’s much-loved Hollywood musical Singin’ in the Rain (1951) — has now dropped to 20th place. The film’s lack of any clear authorial signature and perhaps an over-abundance of levity might explain its fall from grace. Another genre, the western, does make it into the top ten for the first time: The Searchers (1956), the work of celebrated American auteur, John Ford, a film appreciated even by those who don’t like westerns.

Of course, many find these criteria to be limiting in the extreme. There is distrust of the emphasis on the director, for example, especially in a medium that is predicated on creative teamwork. It is telling that the one genre film that appeared in the top ten of the 2002 poll — Stanley Doyen’s and Gene Kelly’s much-loved Hollywood musical Singin’ in the Rain (1951) — has now dropped to 20th place. The film’s lack of any clear authorial signature and perhaps an over-abundance of levity might explain its fall from grace. Another genre, the western, does make it into the top ten for the first time: The Searchers (1956), the work of celebrated American auteur, John Ford, a film appreciated even by those who don’t like westerns.

The celebration of neglected work by female and feminist filmmakers is just one example of how critics have proposed alternative canons in order to redress the inevitable Eurocentric, white, male skew of the list (the highest listed film directed by a woman, Chantal Akerman’s 1975 Jeanne Dielman…, comes in at 36th place). Other commentators have objected to the notion of a film having intrinsic aesthetic value (with the word aesthetic used here in the sense of something outside the everyday, the political, and the historical). The usurping of Kane, read by many as a scathing politicized allegory of US capitalism, by Vertigo, a film that feels dreamily disengaged from the time in which it was made, may well be a sign of this preference coming to the fore. Another lament is the dearth of contemporary films in the top ten. The most recent film, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), was released thirty four years ago, and three silent-era films — FW Murnau’s Sunrise (1927), Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1927), and the Dziga Vertov’s city symphony Man With a Movie Camera (1929) — ensure that the overall balance is tipped firmly towards the first half of the twentieth century. Wong Kar-Wai’s In The Mood For Love (2000), which appears 24th in the list, is the highest placed film made in the new century, but there is as yet no critical consensus around what qualifies as greatness in contemporary cinema.

In his book Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons, New York Times film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum makes an impassioned plea for the importance of the canon. The Sight and Sound poll and the debate it has provoked is essential for the cultivation of a vibrant film culture that is able to identify films of artistic value past, present and future and thereby resist the increasing dominance of the multiplex.

Guy Westwell is a Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at Queen Mary, University of London. He is the author of War Cinema: Hollywood on the Front Line (2006) and (with Annette Kuhn) A Dictionary of Film Studies (2012). Both authors of the Dictionary’s authors contributed to the 2012 Sight and Sound poll: Guy Westwell’s list; Annette Kuhn’s list.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Singin’ in the Rain movie poster. Copyright Turner Entertainment Inc. Used for the purposes of illustration in a commentary on the film. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

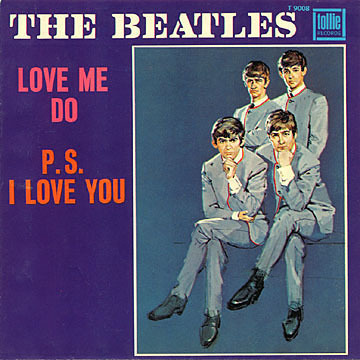

The Beatles at EMI, September 1962

Fifty years ago, the Beatles entered EMI’s recording studios on Abbey Road for their first official recording session. Their June visit had gained them a recording contract, but had cost Pete Best his position when artist-and-repertoire manager George Martin winced at the drummer’s timing. With little ceremony, Lennon, McCartney, and especially Harrison recruited the best drummer in Liverpool — a mate who sometimes subbed for Best — and left the firing of Best to manager Brian Epstein. Thus, Ringo Starr ascended to the drummer’s throne.

The band’s announcement of Pete Best’s replacement provoked outrage on the part of some fans, one of whom assaulted Harrison as he stepped off the stage at the Cavern Club. On 4 September 1962, when they flew from Liverpool to London to record, the guitarist sported a black eye for his support of Starr. They arrived at EMI with material prepared, including Mitch Murray’s “How Do You Do It?” and their own “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me.” Almost as importantly, Paul McCartney had obtained a better bass amplifier. At their June audition, balance engineer Norman Smith, with Ken Townsend, had substituted a makeshift rig from studio equipment that produced a warm, rounded bass sound, with little or no attack. McCartney’s new homemade setup punched a hole through the middle of the Beatles’ sound.

The band’s announcement of Pete Best’s replacement provoked outrage on the part of some fans, one of whom assaulted Harrison as he stepped off the stage at the Cavern Club. On 4 September 1962, when they flew from Liverpool to London to record, the guitarist sported a black eye for his support of Starr. They arrived at EMI with material prepared, including Mitch Murray’s “How Do You Do It?” and their own “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me.” Almost as importantly, Paul McCartney had obtained a better bass amplifier. At their June audition, balance engineer Norman Smith, with Ken Townsend, had substituted a makeshift rig from studio equipment that produced a warm, rounded bass sound, with little or no attack. McCartney’s new homemade setup punched a hole through the middle of the Beatles’ sound.

EMI producer Ron Richards oversaw the rehearsal, coaching them on tempo, phrasing, and their arrangement before Martin took them to dinner. When they returned, they rendered a reasonable, if unenthusiastic version of Murray’s tune before turning to their own material. Martin was convinced that “How Do You Do It?” would top the charts and he would be proved correct. Murray remembers approaching Ron Richards with the tune, who immediately recognized its potential, and when Martin heard the demo (recorded by the Dave Clark Five), he was sure the song could put the Beatles on a national footing. The Beatles have said that they convinced Martin to release their own song, but Murray has indicated that he rejected the Beatles’ version. The songwriter considered the Beatles version of his tune lackluster and he withheld permission from Martin to release it.

One of the other songs they prepared for this 4 September session was “Love Me Do,” almost the most simple item in the Lennon-McCartney catalogue with only a little over a dozen words and, for most of the song, only two chords. Back in June, their arrangement shifted between musical meters, sliding into a lazy shuffle during the harmonica solo of the second chorus; but more problematically, McCartney and Best let the tempo float faster and slower. This time, Martin recorded the instrumental backing separately from the vocals, allowing McCartney and Starr to focus on the tempo, which they hold at a faster tempo than in June, despite occasional temporal disagreements between the two musicians. In addition, McCartney’s bass dominates the mix such that Starr’s bass drum is barely audible.

With Murray rejecting their version of “How Do You Do It?,” Martin arranged for them to return on 11 September to record two more McCartney-Lennon tunes, a new song called “P.S., I Love You” and the work-in-progress, “Please Please Me.” He hoped that one of these songs could serve as the principal side of the release. However when they arrived, they found that Ron Richards, not Martin, would oversee the session and, more surprisingly, Richards had hired a session drummer: Andy White. With the Beatles having already wasted a recording session on a song that Martin could not release, he wanted no more delays. A session drummer could solve the problem.

The startled Starr remembers, “I saw a drum kit that wasn’t mine, and a drummer that most definitely wasn’t me!” Andy White remembers saying very little to the other drummer, whom Richards put to work playing maracas on “P.S., I Love You.” At this point, Starr could rationalize that they were working on a new side and that his original recording of “Love Me Do” would stand. That was before Richards called out for them to rehearse “Love Me Do.”

In the Andy White version of “Love Me Do,” his American-made bass drum and drum heads possess a presence that neither Starr nor Best had achieved, and his cymbal crash following the second chorus has warmth and sustain that shames Starr’s British equipment. More importantly, White synchs with McCartney’s playing as though the two had been born joined at the beat, the tempo standing as steady as a rock. Starr’s tambourine, which doubles White’s snare hits (even if these sometimes arrive at micro-temporally different points), serves as the most obvious way to tell the difference between the two recordings. The session would also feature another attempt at “Please Please Me,” sped up from their 4 September session, but still in need of improvements. It would wait until November.

With two sides recorded, George Martin weighed which one would be the “A” side. Ron Richards reminded him that Frank Sinatra and Dion and the Belmonts had already released another song called “P.S., I Love You” leaving Martin with “Love Me Do” as the featured recording; but which version? He set a release date of 5 October and pondered which recording to choose: Starr or White?

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Thompson’s other posts here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Cover art for the single “Love Me Do” by The Beatles. Copyright Parlophone records. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Used for the purposes of illustrating the work examined in this article.

A brief history of western music defined

Many of you may have seen the cdza video “An Abridged History of Western Music in 16 Genres | cdza Opus No. 7″ (below) that went viral this summer. (cdza, founded by Joe Sabia, Michael Thurber, and Matt McCorkle, create musical video experiments.) To complement this lively celebration of the history of western music, from ragtime to reggae and baroque to bluegrass, we thought about how we can put this music into words. Here’s a quick list of definitions, drawn from the latest edition of The Oxford Dictionary of Music, to help lead you through each genre.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Gregorian chant: Solo and unison plainsong choral chants associated with Pope Gregory I which became the fundamental music of the Roman Catholic Church.

Baroque: [Fr.] Bizarre. Term applied to the ornate architecture of German and Austria during the 17th and 18th centuries and borrowed to describe comparable music developments from about 1600 to the deaths of Bach and Handel in mid-18th century.

Classical: Music composition roughly between 1750 and 1830 (i.e. post-Baroque and pre-Romantic), which covers the development of the classical symphony and concerto; music of an orderly nature, with qualities of clarity and balance, and emphasising formal beauty rather than emotional expression.

March: (marche [Fr.], Marsch [Ger.], Marcia [It.]) Form of music to accompany the orderly progress of large group of people, especially soldiers; one of earliest known music forms.

Ragtime: Early precursor of jazz. Instrumental style, highly syncopated, with the piano forte predominant (though a few rags had words and were sung). Among the leading exponents of the piano forte rag were Scott Joplin, Jelly Roll Morton, and J. P. Johnson, with the cornettists Buddy Bolden and King Oliver.

Jazz: A term, which came into general use circa 1913–15, for a type of music that developed in the Southern States of USA in the late 19th century and came into prominence at the turn of the century in New Orleans, chiefly (but not exclusively) among black musicians.

Soul: Genre of African-American popular music. Soul music combines the emotive, embellished singing style of gospel with the rhythmic drive of rhythm and blues.

Blues: Slow jazz song of lamentation, generally for an unhappy love affair. Usually in groups of 12 bars, each stanza being three lines covering four bars of music.

Motown: American record label, founded in 1960. Name derives from its home town of Detroit (‘the motor town’). A blend of African-American pop and soul, combining dense arrangements (often featuring brass or string), emotionally direct lyrics, and songs based on prominent hooks or grooves, epitomized by such artists as the Four Tops, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, and Stevie Wonder.

Reggae: Style of Jamaican popular music; also used generically for all popular music of that country. Originated in combination of calypso, ska, and rhythm and blues. Its characteristic rhythm, a 4/4 shuffle with accented offbeats derived from ska, was codified in recordings of the late 1960s.

Bluegrass: Genre of country music that originated in rural south eastern USA in 1940s as combination of dance, entertainment, and religious folk music. Name comes from Bill Monroe’s ‘Blue Grass Boys’ group who pioneered the genre.

Disco: Genre of dance music especially popular in the late 1970s. It is generally characterized by soulful vocals, Latin percussion instruments, rich orchestra, frequent use of synthesizers, and bass drum accents on every beat.

Punk: Genre of popular music and wider cultural movement with which it was associated. Originated in America around 1975 with bands such as the Ramones and Television, who looked to the simplicity of 1960s garage rock to restore spirit of rebellion and a DIY spirit to rock and roll.

Heavy metal: Genre of rock music. First applied to style of rock featuring guitar distortion, heavy bass and drums, and virtuoso solos developed, after Jimi Hendrix, by groups such as Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin.

Rap: Highly rhythmicized, semi-spoken vocal style originating in African-American music in late 1970s.

House: Genre of electronic dance music. Originated in Chicago clubs in the early 1980s, particularly through DJ and producer Frankie Knuckles, achieving mainstream popularity by the end of that decade.

Dubstep: A form of dance music, typically instrumental, characterized by a sparse, syncopated rhythm and a strong bassline.

With over 10,000 entries, the Oxford Dictionary of Music offers broad coverage of a wide range of musical categories spanning many eras, including composers, librettists, singers, orchestras, important ballets and operas, and musical instruments and their history. Over 250 new entries have been added to this edition to expand coverage of popular music, ethnomusicology, modern and contemporary composers, music analysis, and recording technology. Existing entries have been expanded where necessary to include more coverage of the reception of major works, and to include key new works and categories, such as multimedia. In addition to print, it is available online through Oxford Music Online and Oxford Reference Online.

Tim Rutherford-Johnson has worked for the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians since 1999 and until 2010 was the editor responsible for the dictionary’s coverage of 20th- and 21st century music. He has published and lectured on several contemporary composers, and regularly reviews new music for both print and online publications. Michael Kennedy was chief music critic of The Sunday Telegraph from 1989 to 2005. He is an authority on English music of the 20th century and has written books on Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Britten, and Walton. Joyce Bourne has a lifelong interest in and love of music and has assisted Michael Kennedy with his works since 1978, both as researcher and typist.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

September 10, 2012

Work-life balance and why women don’t run

Oxford University Press USA has put together a series of articles on a political topic each week for four weeks as the United States discusses the upcoming American presidential election, and Republican and Democratic National Conventions. Our scholars previously tackled the issue of money and politics, the role of political conventions, and the role of media in politics. This week we turn to the role of family in politics.

By Kristin Kanthak

You know the national convention is over when the balloons drop and the presidential candidate’s family joins him on stage amid the cheers of the delegates. In fact, candidates’ families are a central part of their run for the presidency and for their bids for earlier elections prior to the presidency. But we’ve never had a female nominee for the presidency, and the relationship between female politicians and their families is much more complicated.

In the United States, women outnumber men both among college students and among professional and technical workers. Despite this, women lag far behind men in holding political office. Indeed, women held only 17% of the seats in the US Congress after the 2010 election, and a woman has never held the office of President of the United States. Yet political scientists know that when women run for political office, they win at least as often as men, and when they win their elections, they are at least as effective as their male counterparts. The problem, then, is simple: Women don’t run. And part of the reason they don’t run is because women have a different relationship to family than men do.

Researchers have shown that women generally have greater obligations to childcare than men. Furthermore, high-achieving women are far more likely to be married to similarly career-minded spouses than are high-achieving men. High-achieving men, then, are more likely to be married to a woman who can cover the home front, and even provide much-needed “humanity” to their husbands when they run for office. High-achieving women, on the other hand, instead tend to face concerns about how to balance their own ambitions, political or otherwise, with those of their also-ambitious husbands. Consider, for example, the controversy and backlash vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin faced when she attempted to solve the work-life balance problem she faced by allowing her children to travel with her, albeit on the taxpayers’ dime. In fact, this difficulty of navigating the work-life balance prompted former high-ranking state department official Anne Marie Slaughter to write her controversial Atlantic article, “Why Women Still Can’t Have it All.”

Suffragettes at White House. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress.

The pressure of family obligations, then, invariably weighs more heavily on the average successful woman than on the average successful man as she contemplates a potential run for political office. And of course if women don’t run, they can’t win. Furthermore, this lack of female candidates has serious consequences for politics. Most obviously, few women in Congress translates to lower representation for women and the issues that are most important to them. Women politicians as diverse as Hillary Clinton and Susan Molinari report in their autobiographies that they were forced while serving in Congress to clarify women’s perspectives to their male colleagues, and political scientists know that women legislators are much more likely to champion “family” issues than their male counterparts.

But even beyond these increases in the quality of women’s representation, there are benefits associated with having more women in legislatures. Legislatures with a higher percentage of women enjoy greater legitimacy among the people they represent, both women and men. Women approach negotiation differently from men, being more apt to see a negotiation as an opportunity to give everyone something, rather than as a zero-sum competition, an attitude that may be tremendously beneficial in today’s extremely polarized US Congress. Indeed, in my own book with George A. Krause, The Diversity Paradox, we find that increasing women’s numbers in legislatures could well mitigate the difficulties inherent in legislators working together with people of diverse ideological views.

Of course, the paucity of female candidates is not solely due to difficulties inherent in women’s work-life balance problem. We know that women who might run for office are more likely than men to declare themselves unqualified for politics, even if we control for the actual qualifications of the potential candidates. Furthermore, my colleague Jon Woon and I find that even in the social science lab, far beyond the issues of work-life balance, women remain more reluctant than men to run for election. Yet it is clear that our democracy would be better off if more women entered the political arena, and it is equally clear that familial obligations play a strong role in keeping them out. Trying to find a work-life balance may not be just good for working women and their families, but it could be beneficial for our democracy as well.

Kristin Kanthak is an associate professor of political science at the University of Pittsburgh. Her book, The Diversity Paradox, co-authored with George A. Krause, draws on leadership PAC contribution data to show that Members of Congress differentially value their colleagues based on the size of minority groups in Congress. You can follow her on Twitter at @kramtrak. Read her previous blog post: “Five things you may not know about leadership PACs.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about the book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers