Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1025

September 6, 2012

How does the Higgs mechanism create mass?

We’re celebrating the release of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ with a series of posts by science writer Jim Baggott over the week to explain some of the mysteries of the Higgs boson. Read the previous posts: “What is the Higgs boson?”, “Why is the Higgs boson called the ‘god particle’?”, and “Is the particle recently discovered at CERN’s LHC the Higgs boson?”

By Jim Baggott

Through thousands of years of speculative philosophy and hundreds of years of hard empirical science, we have tended to think of mass as an innate property (a ‘primary quality’) of material substance. We figured that, whatever they might be, the basic building blocks of matter would surely consist of microscopic lumps of some kind of ‘stuff’.

But this is not quite how it has worked out. There was a clue in the title of one of Albert Einstein’s most famous research papers, published in 1905: ‘Does the inertia of a body depend on its energy content?’ This was the paper in which Einstein suggested that there was a deep connection between mass and energy, through what would subsequently become the world’s most famous equation, E = mc2.

We experience the mass of an object as inertia (the object’s resistance to acceleration) and Einstein was suggesting that the latter is determined not by mass as a primary quality, but rather by the energy that the object contains.

So, when an otherwise massless particle travelling at the speed of light interacts with the Higgs field, it is slowed down. The field ‘drags’ on it, as though the particle were moving through molasses. In other words, the energy of the interaction is manifested as a resistance to acceleration. The particle acquires inertia, and we think of this inertia in terms of the particle’s ‘mass’.

In the Higgs mechanism, mass loses its status as a primary quality. It becomes secondary — the result of massless particles interacting with the Higgs field.

So, does the Higgs mechanism explain all mass? Including the mass of me, you, and all the objects in the visible universe? No, it doesn’t. To see why, let’s just take a quick look at the origin of the mass of the heavy paperweight that sits on my desk in front of me.

The paperweight is made of glass. It has a complex molecular structure consisting primarily of a network of silicon and oxygen atoms bonded together. Obviously, we can trace its mass to the protons and neutrons which account for 99% of the mass of every silicon and oxygen atom in this structure.

According to the standard model, protons and neutrons are made of quarks. So, we might be tempted to conclude that the mass of the paperweight resides in the masses of the quarks from which the protons and neutrons are composed. But we’d be wrong again. Although it’s quite difficult to determine precisely the masses of the quarks, they are substantially smaller and lighter than the protons and neutrons that they comprise. We would estimate that the masses of the quarks, derived through their interaction with the Higgs field, account for only about 1% of the mass of a proton, for example.

But if 99% of the mass of a proton is not to be found in its constituent quarks, then where is it? The answer is that the rest of the proton’s mass resides in the energy of the massless gluons — the carriers of the strong nuclear force — that pass between the quarks and bind them together inside the proton.

What the standard model of particle physics tells us is quite bizarre. There appear to be ultimate building blocks which do have characteristic physical properties, but mass isn’t really one of them. Instead of mass we have interactions between elementary particles that would otherwise be massless and the Higgs field. These interactions slow the particles down, giving rise to inertia which we interpret as mass. As these elementary particles combine, the energy of the massless force particles passing between them builds, adding greatly to the impression of solidity and substance.

Jim Baggott is author of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ and a freelance science writer. He was a lecturer in chemistry at the University of Reading but left to pursue a business career, where he first worked with Shell International Petroleum Company and then as an independent business consultant and trainer. His many books include Atomic: The First War of Physics (Icon, 2009), Beyond Measure: Modern Physics, Philosophy and the Meaning of Quantum Theory (OUP, 2003), A Beginner’s Guide to Reality (Penguin, 2005), and A Quantum Story: A History in 40 Moments (OUP, 2010). Read his previous blog posts.

On 4 July 2012, scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) facility in Geneva announced the discovery of a new elementary particle they believe is consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson, or ‘god particle’. Our understanding of the fundamental nature of matter — everything in our visible universe and everything we are — is about to take a giant leap forward. So, what is the Higgs boson and why is it so important? What role does it play in the structure of material substance? We’re celebrating the release of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ with a series of posts by science writer Jim Baggott over the week to explain some of the mysteries of the Higgs. Read the previous posts: “What is the Higgs boson?”, “Why is the Higgs boson called the ‘god particle’?”, and “Is the particle recently discovered at CERN’s LHC the Higgs boson?”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Toward a new history of Hasidism

Two years ago, I agreed to serve as the head of an international team of nine scholars from the US, UK, Poland, and Israel who are attempting to write a history of Hasidism, the eighteenth-century Eastern European pietistic movement that remains an important force in the Orthodox Jewish world today. I was perhaps not the obvious choice for this role. Although I’ve written several articles and book chapters on Hasidism, it has not been my main area of research. But Arthur Green, one of the foremost historians of Hasidism and the person who was supposed to head the team, was unable to take on the role and I had had some success as the editor of a large compendium on Jewish and Israeli culture (Cultures of the Jews: A New History). And so, my colleagues convinced me to take on the organizational and editorial work on the project.

Surprisingly, given its long history and influence, no general history of Hasidism exists. The first attempt at such a history was published in 1931 by Simon Dubnow, the doyen of Jewish history in Russia. Dubnow had begun collecting materials for a history of Hasidism in the 1890s. However, his history covered only the first half century of the movement, ending in 1815, which is when he believed the creative period of Hasidism came to an end.

If I was going to direct this ambitious project, I needed to come up to speed on the bibliography of research over the last half century. I was familiar with the major works of the older generation of scholars such as Gershom Scholem, Joseph Weiss, Rivka Schatz-Uffenheimer, and Mendel Piekarz (to name some of the most important) as well as the younger generation, some of whom are members of our team (Ada Rapoport-Albert, Moshe Rosman, and David Assaf). Although the research community working on Hasidism is relatively small, there is still an impressive body of scholarly literature that has emerged over the last few decades.

Fortunately, at about the time I accepted the invitation to direct the Hasidism project, I was also approached by Oxford University Press to serve as Editor-in-Chief of Oxford Bibliographies in Jewish Studies. My first task was to prepare a sample bibliography. So, instead of taking on a subject whose sources were at my fingertips, I decided to put together a bibliography of Hasidism, killing the proverbial “two birds with one stone” (or, as the Jewish saying has it, “to dance at two weddings”).

What emerged from this immersion in the sources was the growing sense that our new history could significantly revise the earlier scholarship. In most of the earlier studies, as well as in Hasidism’s own self-conception, the movement was founded by the Baal Shem Tov, who died in 1760. But like the historical Jesus of Nazareth, the Baal Shem Tov (also known as the Besht) wrote little and probably had no intention of founding a movement. It was only later in the eighteenth century that scattered charismatic leaders (known as rebbes in Yiddish, or zaddikim in Hebrew) began to be seen (and to see themselves) as a coherent movement. But since the Hasidim organized themselves as devoted followers of specific individuals, the movement had no central core. Each of these rebbes had his own philosophy and style of leadership, so that one should speak of Hasidism in the plural.

The nineteenth century, far from a time of stagnation, as Dubnow thought, now appears to have been the golden age of Hasidism. While it is questionable whether the majority of Eastern Jews were Hasidim, the movement spread rapidly and became even more active in areas of Poland and Galicia than in the provinces of Ukraine where it originated. In the twentieth century, Hasidism underwent a sharp decline as a result of the Bolshevik Revolution, the rise of secular Jewish politics in Poland, and the devastation of the Holocaust (see The Holocaust in Poland). Following World War II, the movement rose from the ashes in North America and Israel, in exile, as it were, from its Eastern European homeland. Today, there may be as many as three-quarters of a million Hasidim (out of 13 million Jews worldwide). But a movement that presents itself and is often seen by others as devout guardians of tradition is, in reality, something new, a product of modernity no less than Jewish secularism.

David Biale, Editor in Chief of Oxford Bibliographies in Jewish Studies, is the Emanuel Ringelblum Professor of Jewish History in the department of history of University of California Davis. He is the editor of Cultures of the Jews: A New History (Schocken Books, 2002) and the author of Blood and Belief: The Circulating of a Symbol Between Jews and Christians (University of California Press, 2008).

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

September 5, 2012

Do you ‘cuss’ your stars when you go ‘bust’?

Here, for a change, I will present two words (cuss and bust) whose origin is known quite well, but their development will allow us to delve into the many and profound mysteries of r. Both Dickens and Thackeray knew (that is, allowed their characters to use) the verb cuss, and no one had has ever had any doubts that cuss means “curse.” Bust is an Americanism, now probably understood everywhere in the English-speaking world. The change of curse and burst to cuss and bust seems trivial only at first sight.

The sound designated in spelling by the letter r differs widely from language to language. Even British r is unlike American r, while German, French, and Scots r have nothing in common with Engl. r and one another. All kinds of changes occur in vowels and consonants adjacent to r. Those who know Swedish or Norwegian are aware of the peculiar pronunciation of the groups spelled rt, rd, rn, and rs. In some Germanic languages, postvocalic r tends to disappear altogether. In British English, it seems to have merged with preceding vowels some time later than the beginning of the seventeenth century, because most dialects of American English have preserved postvocalic r; in their speech, father and farther, pause (paws) and pours are not homophones.

In principle, nothing of any interest happened to Engl. r before s. But when we comb through the entire vocabulary, we occasionally run into puzzling exceptions. Thus, a common word for the waterfall is foss, an alteration of force. This force, unrelated to force “strength, might” (of French descent), is a borrowing from Scandinavian. Old Norse had fors, but in Old Scandinavian the spelling foss already turned up in the Middle Ages, and this is why I mentioned the treatment of rs (among other r-groups) in Swedish and Norwegian. Today in both of them rs sounds like a kind of sh to the ear of an English-speaker. Therefore, one could have expected Engl. fosh rather than foss. Forsch did occur in Middle Low (= northern) German, but the extant English form is only foss.

A similar case is the fish name bass. (I am very happy to return to the fish bowl.) All its cognates have r in the middle: Dutch baars, German Barsch, and so forth. The word is allied to bristle. Apparently, r was lost before s in Old Engl. bærs (æ had the value of a in Modern Engl. ban) but not without a trace, for the previous vowel was lengthened and developed into a diphthong, as in bane and its likes. In the name of the game prisoner’s base (a kind of tag with two teams, as probably everybody knows), base may go back to bars. If so, bass, the bristly fish, and base, the game in which participants find themselves behind “bars,” had a similar history. But the fish name is spelled bass instead of base, and this is one of the strangest spellings even in English (imagine lass and mass pronounced as lace and mace).

A bust of a ruler whose empire went bust.

To be sure, we have another bass “low voice,” also pronounced as base, but at least there is an explanation of that oddity. Italian basso was (quite correctly) identified with base “of low quality” and pronounced like that adjective, with the written image of the noun remaining intact. But why bass, the fish name? I could not find any discussion of this minor problem and will venture a conjecture. We have seen that in fors r was lost, and yet the preceding vowel did not undergo lengthening. Perhaps, once bærs shed r, it existed in two forms, with a short vowel (as happened in foss, from fors) and with a long one. The outcome of the compromise was to pronounce the word according to one form and to spell it according to the other. That is why English spelling is such fun. (Compare heifer: the written image reflects its development in the dialects in which the diphthong has been preserved, but the Standard form sounds heffer.)

Another fish name is dace, from Old French dars. Among the fifteenth-century English spellings we find darce and darse. It may not be due to chance that the loss of r before s occurs in words belonging, among others, to fishermen’s vocabulary and children’s lingo. Analogous cases are known from hunters’ usage. The phonetic change in question looks like a feature of unbuttoned and professional speech, for who would control the sounds of the “lower orders” and of the hunters’ jargon? The Standard treated it as vulgar. But fighting the street is a lost cause, though language does not develop from point A to B, C, and all the way to Z. It rather resembles an erratic pendulum; the norm of today may be rejected tomorrow, so that the conservative variant may prevail.

This is what happened in the history of the word first. In the pronunciation of many eighteenth-century speakers (in England), first was indistinguishable from fust- in fustian. Fust for first is not uncommon in today’s American English, but it is “substandard.” Also in the eighteenth century, nurse, purse, and thirsty occurred even in the language of the educated as nus, pus, and thustee. Shakespeare once has goss for “gorse,” and the idiom as rough as a goss has been recorded in the modern Warwickshire dialect. The devil is always worsted, but the fabric worsted is “wusted.” The place name Worstead is only for the locals to pronounce correctly. Those who are not afraid to be lost in this jungle may compare Worcester (UK), Worchester in Georgia and Massachusetts, and Wooster, Ohio. Rejoice that you are not reading a 1721 ad: “Thust things fust.”

This is then what happened to cuss and bust. Cuss, from curse, never left the low (base?) register, though everybody understands cussed and cussedness without a dictionary. Bust fared better (or worse, depending on the point of view). First (fust), its descent from burst isn’t always clear to the uninitiated, so that it became a word in its own right, rather than a shadow cast by burst. Second, although mildly slangy in the phrase go bust, it won a decisive victory in its derivative buster. (Do many people still remember that Theodore Roosevelt was called Trust Buster?) The word’s popularity was reinforced by Buster Brown, the character and the shoes. The “street” scored an important point — so much so that blockbuster is no longer slang. It may perhaps be called colloquial, but it has no synonym of equal value. A blockbuster is a blockbuster.

Perhaps someone is interested in the origin of bust, as in sculpture or in the ads for those women who suspect that their bust is inferior to that of Mrs. Merdle of Little Dorrit fame. It is a borrowing of Italian busto, a word, I am happy to report, of highly debatable etymology.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: 17th century marble bust, from Florence, Italy, of Vespasian, (9-79), first roman emperor of the flavian dynasty, on display at Château de Vaux le Vicomte, France. Photo by Jebulon, 2010. Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

An Anatomy of #Eastwooding

Clint Eastwood took the stage at the Republican convention last week and gave a… well, let’s call it a memorable performance. I’m not sure if there’s ever been such a bizarre prime time address given at a national convention. The celebrated actor/director spent eleven minutes in a mumbling debate with an empty chair representing President Obama. Political conventions are highly-scripted events. Eastwood’s extended, failed ad lib was anything but scripted.

In years past, such a performance would have provided fodder for late-night comedians, but little more. Saturday Night Live and Letterman could weigh in, while you and I were left to passively chuckle. Living in the age of social media, events unfolded at a different pace and among different participants.

Within minutes, an anonymous Twitter user registered the name @InvisibleObama. Conjuring shades of @MayorEmanuel, the participatory features of the hybrid news environment allowed formerly-passive members of the audience to swap jokes. That evening, Twitter users launched a new hashtag, “#eastwooding,” wherein individuals post pictures of themselves pointing at empty chairs. Thusly a new “meme” was born.

Within less than a day, @InvisibleObama has attracted over 55,000 Twitter followers. Newsweek/DailyBeast has posted an #Eastwooding “best of” list. CNN covered it as well. Participatory engagement with Eastwood’s odd performance made itself became the subject of news.

The President himself even weighed in, tweeting “This Seat’s Taken.”

This is all in good fun, of course. Twitter during national events adopts the texture of a giant Mystery Science Theater 3000 episode. But in the course of this distraction, one might wonder, does it actually make any difference?

I would argue that political memes and twitter games like #eastwooding have a very specific, but very limited, effect.

Let’s start with the obvious limitations: @InvisibleObama and #Eastwooding will have no direct impact on the outcome of the 2012 election. These are games played by the already-politically-engaged. 55,000 Twitter followers is a drop the ocean compared to the ~38 million total viewers of the Republican National Convention, or the 100 million+ citizens who will cast a vote in the November election. Individuals who #Eastwood are among the most attentive segments of the populace. They’re also more likely to be liberal. Conservatives have taken to defending Eastwood’s display as counter-intuitively good for Romney. #Eastwood’ers have already made up their minds, and they each only have one vote.

Secondary effects are also pretty limited. Politically-aware Twitter users tend to be connected to one another (social network theorists call this phenomenon “homophily”). We should not expect individuals who chose to ignore the RNC convention to pick up on it after-the-fact due to social media chatter.

Furthermore, memes of this sort have a pretty brief half-life. With the Democratic National Convention scheduled for this week, the hybrid media system will quickly turn its attention to a new set of images and statements. One impact of new media on political news is that the “churn” of the news cycle has sped up. Congressman Todd Akin’s outlandish claims about female biology already seem part of the distant past. By the time of the October Presidential debates, #Eastwooding will have been replaced a half-dozen times. We shouldn’t expect it to be on anyone’s mind when they enter the voting booth.

That said, the limited size and duration of these Twitter memes doesn’t render them useless. In very particular ways, this participatory nature of the new media system has an important effect on media and politics today.

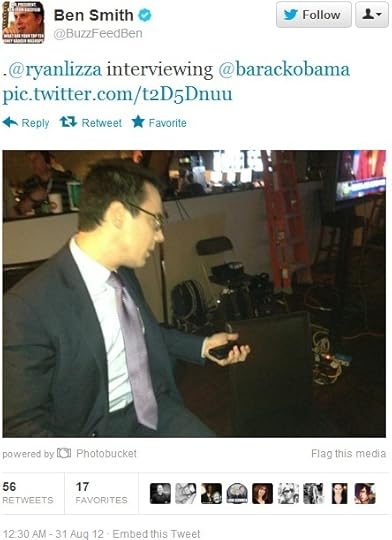

Consider this post as an example:

BuzzFeedBen is Ben Smith, formerly of Politico.com, current editor-in-chief of Buzzfeed.com. Ryan Lizza is an accomplished political journalist whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New Republic, The Atlantic, and Vanity Fair. Other journalists, such as Slate’s Dave Weigel, also joined in the fun.

These journalists aren’t revealing some hidden liberal bias through their actions; they are revealing a participatory bias. A small segment of the US population pays a lot of attention to politics. The hybrid media environment allows journalists to engage with these attentive citizens. The interactions can help shape news coverage, or (in cases where the media runs stories on #Eastwooding) become the subject of news coverage. Rather than writing about the policy details (or lack thereof) in Romney’s acceptance speech, many news outlets turned instead to Eastwood’s odd performance, and the global audience’s playful reaction. This changes the texture and content of media coverage.

The Internet didn’t cause this merger of news and entertainment. It began in the 1980s, as newsrooms sought higher ratings and larger profits. Political communication scholars raised concerns about “infotainment” before the average citizen owned a modem. Twitter isn’t the cause of this merger; it is merely the latest iteration.

The limitations of these incidents are likewise nothing new. Everyday political gaffes don’t determine the outcome of a national election. Today’s media environment churns faster, so we see more of the gaffes. It is also more segmented, so those of us who aren’t interested in seeing them can tune out more easily.

Cases like #Eastwooding provide a variation on these longstanding trends. American politics has accepted the blurring of political news and political entertainment. Social media provides a participatory element, making the entertainment aspects much more entertaining.

David Karpf is an Assistant Professor in the School of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University. He is the author of The MoveOn Effect: The Unexpected Transformation of American Political Advocacy. His research focuses on the Internet’s disruptive effect on organized political advocacy. He blogs at shoutingloudly.com and tweets at @davekarpf.

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for four weeks as the United States discusses the upcoming American presidential election, and Republican and Democratic National Conventions. Our scholars previously tackled the issues of money and politics, and the role of political conventions. This week we turn to the role of media in politics. Read the previous article in this series: “Networked politics in 2008 and 2012.” And you can see OUP’s contribution to #Eastwooding on Google Plus.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only media articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credits: Both screencaps were taken on 4 September 2012 at 11:11 am ET.

Is the particle recently discovered at CERN’s LHC the Higgs boson?

We’re celebrating the release of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ with a series of posts by science writer Jim Baggott over the week to explain some of the mysteries of the Higgs boson. Read the previous posts: “What is the Higgs boson?” and “Why is the Higgs boson called the ‘god particle’?”

By Jim Baggott

Experimental physicists are by nature very cautious people, often reluctant to speculate beyond the boundaries defined by the evidence at hand.

Although the Higgs mechanism is responsible for the acquisition of mass, the theory does not give a precise prediction for the mass of the Higgs boson itself. The search for the Higgs boson, both at Fermilab’s Tevatron collider and CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), has therefore involved elaborate calculations of all the different ways a Higgs boson might be created in high-energy particle collisions, and all the different ways it may decay into other elementary particles.

At CERN, the attentions of physicists working in the two main detector collaborations, ATLAS and CMS, have been drawn to Higgs decay pathways involving the production of two photons (which we write as H → γγ), a pathway leading to two Z bosons and thence four leptons (particles such as electrons and positrons, written H → ZZ → ι+ι-ι+ι-) and a pathway leading to two W particles and thence to two leptons and two neutrinos (H → W+W- → ι+υ ι-υ).

Finding the Higgs boson is then a matter of looking for its decay products — in this case the photons and leptons that result — at all the different masses that the Higgs may in theory possess. Just to make life more difficult, at the particle collision energies available at the LHC, there are lots of other processes that can produce photons and leptons, and this background must be calculated and subtracted from the observed decay events. Any events above background that produce two photons, four leptons or two leptons (and ‘missing’ energy, as neutrinos cannot be detected) then contribute to the evidence for the Higgs boson.

What the CERN scientists announced on 4 July was a statistically significant excess of decay events consistent with a Higgs boson with a mass between 125-126 billion electron volts, about 134 times the mass of a proton. This is definitely a new boson, one that decays very much like a Higgs boson is expected to decay. But, until the scientists can gather more data on its physical properties, they can’t say for sure precisely what kind of boson it is.

It’s also important to note that although the Higgs boson is predicted by the standard model of particle physics, there are theories that also predict the existence of a Higgs boson (actually, they predict many Higgs bosons). Until the scientists gather more data, they can’t be sure the new particle is precisely the particle predicted by the standard model.

We just need to be patient and stay tuned.

Jim Baggott is author of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ and a freelance science writer. He was a lecturer in chemistry at the University of Reading but left to pursue a business career, where he first worked with Shell International Petroleum Company and then as an independent business consultant and trainer. His many books include Atomic: The First War of Physics (Icon, 2009), Beyond Measure: Modern Physics, Philosophy and the Meaning of Quantum Theory (OUP, 2003), A Beginner’s Guide to Reality (Penguin, 2005), and A Quantum Story: A History in 40 Moments (OUP, 2010). Read his previous blog posts.

On 4 July 2012, scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) facility in Geneva announced the discovery of a new elementary particle they believe is consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson, or ‘god particle’. Our understanding of the fundamental nature of matter — everything in our visible universe and everything we are — is about to take a giant leap forward. So, what is the Higgs boson and why is it so important? What role does it play in the structure of material substance? We’re celebrating the release of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ with a series of posts by science writer Jim Baggott over the week to explain some of the mysteries of the Higgs. Read the previous posts: “What is the Higgs boson?” and “Why is the Higgs boson called the ‘god particle’?”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Avast, ye file sharers! Is Internet piracy dead?

The fact that the Internet is so hard to police — and that no single authority is in a position to dictate what it should and should not contain — should be cause for celebration for anyone with an interest in the freedom of speech, expression, and the sharing of ideas. But the Internet has two faces. For every positive exercise of those and other freedoms, there’s an act of fraud, counterfeiting, and copyright infringement. How is the law — in particular the English legal system — attempting to stem the tide of the last problem (online infringement) and take pirates down?

Attacks are being made on two main fronts in the UK. The first is via section 97A of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This permits a court to order a service provider — which could be an ISP, a search engine, or a social networking website — to block its users from accessing infringing material. To take ISPs as an example: when there are perhaps millions of infringing users in the UK using the internet access services of only six major ISPs, it’s going to be much easier to pursue those intermediaries than it is the individuals.

Although section 97A has been around since 2003, the first real attempt to use it wasn’t until 2011. The film industry brought a test case against the UK’s largest ISP, BT, seeking a court-ordered block of an infringing service called NewzBin2. BT heavily resisted the attempt, but every ground it raised was dismissed by the High Court and a block was ordered. This year it was the turn of the music industry, which sought blocks from BT and the remaining five major UK ISPs against the celebrity poster-boy of internet piracy: The Pirate Bay (TPB). With none of the ISPs willing to defend such an obviously dubious service, the High Court easily found TPB to be infringing copyright in February of this year. With little to distinguish TPB from NewzBin2, the ISPs then largely gave up the fight and dropped any opposition to a block. This was then ordered in May.

While section 97A has been making waves since its first appearance last year, the second front has been bobbing along in calm waters. Key provisions of the Digital Economy Act 2010 impose obligations upon ISPs to notify their subscribers, once those ISPs have been informed by copyright owners that those subscribers are suspected of infringing copyright, mostly likely via peer-to-peer file sharing (via sites such as TPB). Repeat offenders are put on what is effectively a “naughty list” and copyright owners can use those lists to pick juicy targets for taking further action. Two major ISPs tried to knock the Act out by launching judicial review proceedings, complaining that it offended European and human rights laws. They failed overall, but their actions have delayed the introduction of the Act’s notification regime. A final draft of the Initial Obligations Code (the Code), which sets out the details of the regime’s operation, has now been prepared by Ofcom (the UK’s communications regulator) and was put out for a consultation which ended in July. But there is a lot of work to be done before the regime begins. For example, an independent appeals body is to be created to deal with subscribers who wish to appeal an allegation of infringement. Accordingly, the Government does not expect the first notification letter to be sent until 2014. In the immediate term the Code will not provide for any real sanctions against subscribers beyond receipt of the letter, and accordingly can be criticised as lacking teeth.

While introducing the Digital Economy Act is probably better than doing nothing, the Newzbin2 and TPB cases suggest that section 97A is the far more effective weapon against piracy. Service providers may now be more motivated to assist copyright owners to police their services, if the alternative is to face the cost and bother of a section 97A application that the odds are they’ll lose. There is no direct connection, but in response to industry pressure Google (which may be the next target for a section 97A application) has recently agreed to demote websites from its search results where it has repeatedly received reports of those sites hosting infringing material. It’s a start, but it won’t remove them from its listings altogether.

The UK can’t, of course, solve this problem alone. A number of jurisdictions now have bespoke anti-file-sharing laws in place. These include France (HADOPI); Spain (Ley Sinde); South Korea and New Zealand. Others are in development. As well as being legally challenging, these sorts of measures are also proving politically controversial. Proposed legislation in the USA — SOPA (Stop Online Piracy Act) and PIPA (PROTECT IP Act) — met with huge public opposition earlier this year and are being reconsidered, but may still come to pass in some form. Before leaving power, President Sarkozy of France hailed HADOPI as hugely successful. The new government in France is reported to be less enthusiastic about the law and its multi-million Euro yearly cost.

It’s worth finishing with a note on circumvention. Very few, if any, of the measures discussed above are foolproof. Many (website blocks for example) are fairly straightforward to get around. Although a large proportion of casually infringing Internet users may not know how, a Google search for “How do I get around The Pirate Bay block?” reveals plenty of results, including several videos on Google’s own YouTube. Ironically, when I clicked on the first video in the list, I was presented with an advert for one of 20th Century Fox’s soon to be released (and no doubt, pirated) movies. Evidently, there’s still a lot of work to be done.

Darren Meale is a Senior Associate and Solicitor-Advocate at SNR Denton, specialising in intellectual property litigation and advice. He has particular expertise and interest in digital rights issues, including the way in which the Internet and new digital technologies interact with and potentially infringe intellectual property rights. His recent paper, ‘Avast, ye file sharers! The Pirate Bay is sunk’, has been made freely available for a limited time by the Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice.

JIPLP is a peer-reviewed monthly journal. It is specifically designed for IP lawyers, patent attorneys and trade mark attorneys both in private practice and working in industry. It is also an essential source of reference for academics specialising in IP, members of the judiciary, officials in IP registries and regulatory bodies, and institutional libraries. Subject-matter covered is of global interest, with a particular focus upon IP law and practice in Europe and the US.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Pirate button on computer keyboard. Photo by Sitade, iStockphoto.

September 4, 2012

Post-mortem on the RNC Convention

The Republicans’ convention bump for Mitt Romney appears to be muted. Why? There was a lot of bad luck. Holding the convention before the Labor Day weekend caused television viewership to go down by 30 percent, as did the competing and distracting news about Hurricane Isaac. The Clint Eastwood invisible chair wasn’t a disaster, but a wasted opportunity that Romney’s advisors should have vetted. Valuable time that could have been spent promoting Romney (such as the video of him that had to be played earlier) before he came out to speak on prime time, was instead spent in a meandering critique of Obama.

Obama’s first remarks about the convention was that it was something you would see on a black-and-white tv — a new spin on the Republican Party as allegedly backward, as opposed to the Democrat’s who lean “Forward.”

The most revealing thing about the convention was that President George W. Bush wasn’t asked to speak. Instead, he appeared in a video with the older Bush, possibly in a bid to mollify the presence of the younger. Republicans are still divided over Bush, which is why they continued their hagiography of Reagan in the convention. For all of Jeb Bush’s intonations for the Obama campaign to stop putting blame on the previous administration, the fact is that the convention conceded that George W. Bush was indeed a liability. “Forward” is a narrative that can work as long as the look immediately backwards isn’t too satisfying.

On the other side, Bill Clinton will of course make an appearance in Charlotte in next week. The Democrats have also wisely flooded the speakers’ list with women, to show that the Republicans’ paltry presentation of just five women represent the tokenism narrative that Democrats are trying to paint. Women are America’s numerically biggest demographic and they are more likely to turn out than men (by 4% in 2008).

In this final stretch, the gurus are gunning straight for the demographics. Campaigning has become a science, albeit an imperfect one. The Romney campaign now knows that a generic refutation of the Obama’s performance about the economy, jobs, the national debt — which we’ve been hearing for nearly four years — is not going to change the underlying tectonics of voter sentiment. This is why they tried to elevate the Medicare issue last week, and why they’re trying the personalize Romney strategy this week. The latter is more likely to work, and it should be done quickly, because next week, the DNC intends to make America fall in love with Barack Obama again.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Osama and Obama

No Easy Day, the new book by a member of the SEAL team that killed Osama bin Laden on 30 April 2011, has attracted widespread comment, most of it focused on whether bin Laden posed a threat at the time he was gunned down. Another theme in the account by Mark Owen (a pseudonym) is how the team members openly weighed the political ramifications of their actions. As the Huffington Post reports:

Though he praises the president for green-lighting the risky assault, Owen says the SEALS joked that Obama would take credit for their success…. one SEAL joked, “And we’ll get Obama reelected for sure. I can see him now, talking about how he killed bin Laden.”

Owen goes on to comment that he and his peers understood that they were “tools in the toolbox, and when things go well [political leaders] promote it.” It is an observation that invites only one response: Duh.

Of course, a president will bask in the glow of a national security success. The more interesting question, though, is whether it translates into gains for him and/or his party in the next election. The direct political impact of a military victory, a peace agreement, or (as in this case) the elimination of a high-profile adversary tends to be short-lived. That said, events may not be isolated; they also figure in the narratives politicians and parties tell. For Barack Obama and the Democrats in 2012, this secondary effect is the more important one.

Wartime presidents have always been sensitive to the ticking of the political clock. In the summer of 1864, Abraham Lincoln famously fretted that he would lose his reelection bid. Grant’s army stalled at Petersburg after staggering casualties in his Overland campaign; Sherman’s army seemed just as frustrated in the siege of Atlanta; and a small Confederate army led by Jubal Early advanced through the Shenandoah Valley to the very outskirts of Washington. So bleak were the president’s political fortunes that Republicans spoke openly of holding a second convention to choose a different nominee. Only the string of Union victories — at Atlanta, in the Shenandoah Valley, and at Mobile Bay — before the election turned the political tide.

Election timing may tempt a president to shape national security decisions for political advantage. In the Second World War, Franklin Roosevelt was eager to see US troops invade North Africa before November 1942. Partly he was motivated by a desire to see American forces engage the German army to forestall popular demands to redirect resources to the war against Japan, the more hated enemy. But Roosevelt also wanted a major American offensive before the mid-term elections to deflect attention from wartime shortages and labor disputes that fed Republican attacks on his party’s management of the war effort. To his credit, he didn’t insist on a specific pre-election date for Operation Torch, and the invasion finally came a week after the voters had gone to the polls (and inflicted significant losses on his party).

The Vietnam War illustrates the intimate tie between what happens on the battlefield and elections back home. In the wake of the Tet Offensive in early 1968, Lyndon Johnson came within a whisker of losing the New Hampshire Democratic primary, an outcome widely interpreted as a defeat. He soon announced his withdrawal from the presidential race. Four years later, on the eve of the 1972 election, Richard Nixon delivered the ultimate “October surprise”: Secretary of State Henry Kissinger announced that “peace is at hand,” following conclusion of a preliminary agreement with Hanoi’s lead negotiator Le Duc Tho. In fact, however, Kissinger left out a key detail. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu balked at the terms and refused to sign. Only after weeks of pressure, threats, and secret promises from Nixon, plus renewed heavy bombing of Hanoi, did Thieu grudgingly accept a new agreement that didn’t differ in its significant provisions from the October version.

But national security success yields ephemeral political gains. After the smashing coalition triumph in the 1991 Gulf War, George H. W. Bush enjoyed strikingly high public approval ratings. Indeed, he was so popular that a number of leading Democrats concluded he was unbeatable and decided not to seek their party’s presidential nomination the following year. But by fall 1992 the victory glow had worn off, and the public focused instead on domestic matters, especially a sluggish economy. Bill Clinton’s notable ability to project empathy played much better than Bush’s detachment.

And so it has been with Osama and Obama. Following the former’s death, the president received the expected bump in the polls. Predictably, though, the gain didn’t persist amid disappointing economic results and showdowns with Congress over the debt ceiling. From the poll results, we might conclude that Owen and his Seal buddies were mistaken about the political impact of their operation.

But there is more to it. Republicans have long enjoyed a political edge on national security, but not this year. The death of Osama bin Laden, coupled with a limited military intervention in Libya that brought down an unpopular dictator and ongoing drone attacks against suspected terrorist groups, has inoculated Barack Obama from charges of being soft on America’s enemies. Add the end of the Iraq War and the gradual withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan and the narrative takes shape: here is a president who understands how to use force efficiently and with minimal risk to American lives. Thus far Mitt Romney’s efforts to sound “tougher” on foreign policy have fallen flat with the voters. That he so rarely brings up national security issues demonstrates how little traction his message has.

None of this guarantees that the president will win a second term. The election, like the one in 1992, will be much more about the economy. But the Seal team operation reminds us that war and politics are never separated.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Pablum for profit’s sake?

When Protestant evangelicals opened a Hollywood front in the late twentieth-century “culture wars,” the result was an odd mixture of moral reproach and commercialization of religion. To no avail, they famously protested MCA/Universal over The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), and then joined conservative Catholics — outraged over the movie Priest (1995) — in a boycott of the Walt Disney Company, the world’s largest provider of family entertainment.

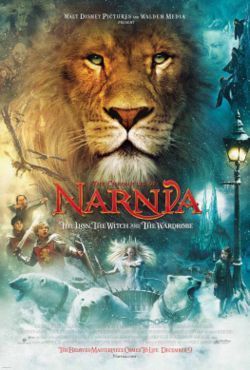

Then again, evangelicals contributed greatly to the incredible box-office success of The Passion of the Christ in 2004, and the next year called off their boycott when Disney brought The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to the screen. These box-office victories drew Hollywood’s attention to those consumers who were spending hundreds of millions of dollars on religious books, merchandise, and music. Moviemakers wanted a piece of the action. The next year, 20th Century-Fox created FoxFaith, a new home entertainment division, to go after the “Passion dollar.”

Then again, evangelicals contributed greatly to the incredible box-office success of The Passion of the Christ in 2004, and the next year called off their boycott when Disney brought The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to the screen. These box-office victories drew Hollywood’s attention to those consumers who were spending hundreds of millions of dollars on religious books, merchandise, and music. Moviemakers wanted a piece of the action. The next year, 20th Century-Fox created FoxFaith, a new home entertainment division, to go after the “Passion dollar.”

These are not isolated or unprecedented events. There is a long-standing and complicated relationship between Protestant churches and the movie industry, and put in that context, evangelical strategies actually went against the central Protestant approach to movie reform.

To establish a fitting role for the cinema, Protestants traditionally sought a measure of harmony between individual liberty, artistic freedom, and the common good. While understanding the need for film producers to make money, Protestants long believed that the cinema should be developed along the lines of artistic and social responsibility. Perceiving themselves as a countervailing force to the film industry’s incessant drive to maximize profits, they argued that by tacitly accepting the industry’s commercial ethos, the church was effectively commodifying religion and values instead of “relating itself to the arts of communication, rather than commercial selling of a product.”

Instead of nitpicking at perceived immoral incidents or being satisfied with the mere inclusion of a religious theme, Protestants focused their criticism on a movie’s overall perspective. A film that was made “decent” by deleting distasteful elements could still be dishonest (in its treatment of life) and dull (as art and entertainment). It was the film’s artistic prowess and embodied perspective that mattered most.

In a departure from this Protestant tradition, the evangelical course was really a replay of tactics pursued by the Catholic Legion of Decency. Beginning in the mid-1930s, Catholic bishops used consumer pressure to coerce filmmakers into making changes in movies prior to release in theaters. In contrast, Protestant leaders — by tradition — refused to restrict individual liberty by controlling the viewing habits of church members.

Nevertheless, after World War II some Protestants wanted to imitate the Catholics by consulting with film producers to ensure that Protestants received the same flattering treatment in movies as priests and nuns. But any aspirations that Protestants could deliver an audience large enough to redirect Hollywood’s output were dispelled by The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), a commercial and critical disaster that brought an end to the era of big-budget biblical epics like The Ten Commandments (1956).

These events apparently faded from memory, and as the evangelical consumer culture blossomed during the 1980s and ‘90s, evangelical leaders took their turn now — after mainline Protestants and then Catholics — as the nation’s custodian of movie morals. Mixing boycott threats with promises to deliver American pew sitters to movie theaters, they petitioned Hollywood for wholesome family entertainment — meaning no explicit sex, profanity, or violence (in that order of priority). As a result, in the popular perception at least, kid-friendly has become the defining feature of a “Christian” aesthetic that ultimately prizes PG-rated fare attuned to the level of children.

Evangelicals embraced profit-making as their modus operandi for movie reform with much more intensity than any of their predecessors; their appeal ultimately was to the corporate bottom line, not artistic quality or social responsibility.

This market-based strategy harbors an inherent contradiction — one that always seems to escape its adherents. The obvious assumptions are that “good” movies are somehow those that are commercially successful and that a free market will produce movie morality. On what basis then can evangelicals limit screen exploitation other than profitability? The gauge of commercial success can be used to justify family movies as much as crude teen comedies; the Christian-themed The Blind Side and raunchy The Hangover each earned over $200 million domestically in 2009.

With box-office results dictating the terms of quality, film production will always be a slave to momentary fashionable trends. But as the head of an evangelical pro-family organization put it, studio executives should just “give the public more of what it wants — for profits sake.”

William Romanowski is Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences at Calvin College. His books include Reforming Hollywood: American Protestants and the Movies, Eyes Wide Open: Looking for God in Popular Culture (a 2002 ECPA Gold Medallion Award Winner) and Pop Culture Wars: Religion and the Role of Entertainment in America Life. Watch a video where he explains protestantism in Hollywood.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe poster. Copyright Walt Disney Studios. Used for the purposes of commentary on the work. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Why is the Higgs boson called the ‘god particle’?

We’re celebrating the release of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ with a series of posts by science writer Jim Baggott over the next week to explain some of the mysteries of the Higgs boson. Read the previous post: “What is the Higgs boson?”

By Jim Baggott

The Higgs field was invented to explain how otherwise massless force particles could acquire mass, and was used by Weinberg and Salam to develop a theory of the combined ‘electro-weak’ force and predict the masses of the W and Z bosons. However, it soon became apparent that something very similar is responsible for the masses of the matter particles, too.

The way the Higgs field interacts with otherwise massless boson fields and the way it interacts with massless fermion fields is not the same (the latter is called a Yukawa interaction, named for Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa). Nevertheless, the Higgs field clearly has a fundamentally important role to play. Without it, both matter and force particles would have no mass. Mass could not be constructed and nothing in our visible universe could be.

In his popular book The God Particle: If the Universe is the Answer, What is the Question?, first published in 1993, American physicist Leon Lederman (writing with Dick Teresi) explained why he’d chosen this title:

This boson is so central to the state of physics today, so crucial to our final understanding of the structure of matter, yet so elusive, that I have given it a nickname: the God Particle. Why God Particle? Two reasons. One, the publisher wouldn’t let us call it the Goddamn Particle, though that might be a more appropriate title, given its villainous nature and the expense it is causing. And two, there is a connection, of sorts, to another book, a much older one…

Lederman went on to quote a passage from the Book of Genesis.

This is a nickname that has stuck. Most physicists seem to dislike it, as they believe it exaggerates the importance of the Higgs boson. Higgs himself doesn’t seem to mind.

Jim Baggott is author of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ and a freelance science writer. He was a lecturer in chemistry at the University of Reading but left to pursue a business career, where he first worked with Shell International Petroleum Company and then as an independent business consultant and trainer. His many books include Atomic: The First War of Physics (Icon, 2009), Beyond Measure: Modern Physics, Philosophy and the Meaning of Quantum Theory (OUP, 2003), A Beginner’s Guide to Reality (Penguin, 2005), and A Quantum Story: A History in 40 Moments (OUP, 2010). Read his previous blog post “Putting the Higgs particle in perspective.”

On 4 July 2012, scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) facility in Geneva announced the discovery of a new elementary particle they believe is consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson, or ‘god particle’. Our understanding of the fundamental nature of matter — everything in our visible universe and everything we are — is about to take a giant leap forward. So, what is the Higgs boson and why is it so important? What role does it play in the structure of material substance? We’re celebrating the release of Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God Particle’ with a series of posts by science writer Jim Baggott over the next week to explain some of the mysteries of the Higgs. Read the previous post: “What is the Higgs boson?”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers