Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1029

August 24, 2012

Paul Ryan, Randian? No, just another neocon

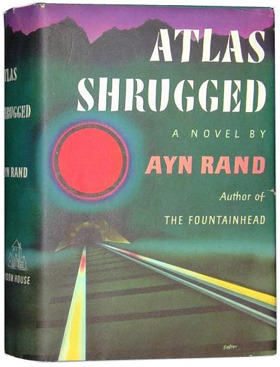

Paul Ryan — possible future Vice President of the United States — calls Ayn Rand one of his principal inspirations. He once claimed (and later denied) that Atlas Shrugged was required reading for his staff. He even gives copies of Atlas Shrugged as Christmas presents, which is a touch ironic, since Rand was an ardent atheist.

Are we just one heart attack or gunshot away from an Ayn Rand presidency? No. As the saying goes, actions speak louder than words. Paul Ryan’s voting record speaks loudly. He is no Randian libertarian. Rather, he is just another run-of-the-mill big government neoconservative. Ryan’s rise isn’t the ascent of Ayn Rand, but the return of George W. Bush.

Are we just one heart attack or gunshot away from an Ayn Rand presidency? No. As the saying goes, actions speak louder than words. Paul Ryan’s voting record speaks loudly. He is no Randian libertarian. Rather, he is just another run-of-the-mill big government neoconservative. Ryan’s rise isn’t the ascent of Ayn Rand, but the return of George W. Bush.

Ayn Rand believed people should be free to anything they please, so long as they don’t trample on the rights of others. She advocated a minimal, night-watchman state. She believed a just government would provide protection, law courts to settle disputes, and nothing else. Rand didn’t advocate low taxes, but no taxes. She believed a just government would collect fees for services rendered.

Rand would regard our current government as an unjust, rights-violating, bloated monstrosity. It is a monster Paul Ryan helped create. Ryan may admire Ayn Rand. He may quote F. A. Hayek in interviews. Yet his voting record is right out of the neocon playbook.

Rand opposed government bailouts and subsidies. Yaron Brooks, director the Ayn Rand Institute, said the bailouts were “national socialism of the financial markets.” In contrast, Ryan voted for the bank bailouts. He broke with party leadership and the majority of his fellow republicans by voting for the auto bailouts. He supported TARP.

Rand famously opposed government welfare and social insurance. Ryan voted for Medicare Part D, which subsidizes prescription drugs for seniors. Thus, Ryan was instrumental in producing the largest expansion of the welfare state since Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society.

Ryan supported the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The Watson Institute at Brown University estimates that these wars have already cost the federal government $3-4 trillion. These wars will be paid for by taxes, which Ayn Rand regarded as theft. Rand opposed having the US act as the world’s policeman.

Ryan has a reputation as a hardcore budget cutter, but the House Committee on the Budget says his budget plan would still allow the federal budget to grow at over 3% a year. If Ryan’s plan would balance the budget at all, it would do so only by 2040, when our children have grey hair. So much for a Randian small government.

Libertarians like Rand believe immigration restrictions expose the world’s poor to abuse and exploitation, and condemn them to poverty and death. (Rand herself may have been an illegal immigrant.) In contrast, Ryan voted against the Dream Act. He voted in favor of making the border more secure and of expanding the fence on the Mexican border.

Rand, an ardent opponent of totalitarianism, would have hated the Patriot Act. Ryan voted in favor of the Patriot Act and supports making it permanent. Rand would have opposed creating the Department of Homeland Security, which Ryan helped create.

Libertarians like Rand are famous for their “legalize everything” opposition to the War on Drugs. Paul Ryan is a drug warrior.

On social issues, Ryan’s Catholicism dominates his Randianism. Ryan calls himself an “unwavering foe of abortion rights” and co-sponsored a bill that would grant full legal rights to fertilized eggs. Ayn Rand said, “Abortion is a moral right — which should be left to the sole discretion of the woman involved; morally, nothing other than her wish in the matter is to be considered.” She said that for many of the struggling poor, “pregnancy is a death sentence… [which would] condemn them to a life of hopeless drudgery, of slavery to a child’s physical and financial needs.” She would say of Ryan what she said of Reagan, i.e., that Ryan threatens to “to take us back to the Middle Ages, via the unconstitutional union of religion and politics.”

Paul Ryan votes like a neoconservative, not a Randian. Neoconservatives, such as George W. Bush or Dick Cheney, talk the small government talk but walk the large government walk. They charge the US government with exporting democracy and the American way of life to the rest of the world. They charge the government with guarding the moral and sexual virtue of citizens. They want government to champion and support big business.

If you want to be scared by Paul Ryan, be scared of what he does, not what he says.

Jason Brennan is Assistant Professor of Ethics, Economics, and Public Policy at Georgetown University. He is the author of Libertarianism: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2012), The Ethics of Voting (Princeton University Press, 2012), and co-author of A Brief History of Liberty (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). He blogs at BleedingHeartLibertarians.com.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Atlas Shrugged, first edition, book cover. Copyright Random House. Used to illustrate an article concerning the book in question. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Early intervention for children with reading difficulties

“My child will be starting school in two weeks. I can’t believe summer is almost over. I’m beginning to worry. Ellie still has trouble reading simple words and she does not like to read. I had problems with reading at her age. I wonder if I should wait till December to have her assessed or do it right now.”

“Katie’s teacher raised a flag last year. Katie will be in the third grade in a few weeks. I think she has a problem with reading and attention.”

Getting ready to go back to school can be a challenge. It is even more of a challenge when you suspect something is not quite right with your child. As parents, we do not want our child to have problems. We deeply want our child to be o.k. in everyday life. When our child suffers, we suffer as well.

What Ellie and Katie’s parents do not know is that their children are at risk for dyslexia. Dyslexia refers to “unexpected” difficulty in learning to read. In other words, reading fails to develop in the child despite their intelligence, education, motivation, and exposure to reading instruction in school. By the end of kindergarten, a child should be naming the letters of the alphabet, writing letters of the alphabet, learning that letters are associated with sounds, and even decoding simple sight words. A child should be reading and spelling words correctly at their grade level in first grade. Unfortunately, many parents tell me that their child will grow out of the problem. In fact, Katie’s father also acknowledged he had problems with reading. Ellie is voicing much frustration because reading words is difficult. Reading clearly isn’t fun. At the same time, Ellie’s mother thinks it is the lack of structure in the classroom that is causing the problem.

As parents, we need to trust our gut when things are a little off. The keys to recognizing a possible disorder could exist are the frequency, intensity, and pervasiveness of the behaviors:

Frequency: How often is your child exhibiting these behaviors?

Intensity: How severe are the behaviors compared to that of other children their age?

Pervasiveness: Are the behavior(s) occurring in many situations? For example, are the behaviors exhibited during classroom instruction, tests, and homework time?

What are some of the warning signs when a child is exhibiting troubles with reading in kindergarten? You may notice the following challenges:

Pronouncing words

Reciting popular nursery rhymes

Recalling the names of letters

Recognizing the names of letters

Recognizing common sight words

Voicing frustration when sounding out simple words

Sustaining attention and concentration when reading a story or when you are reading a story

You and the teachers may also recognize the following warning signs in elementary school:

Relies on memorizing words

Rushes and substitutes words when reading

Problems spelling words

No problems understanding text when read to orally

Voices frustration and complains of fatigue when reading

Complains about rereading material

Problems remembering what was read

Difficulty completing tests and in-class work on time

Dreads reading in front of the class

Stumbles over words and has trouble thinking of the right word when conversing with others

Early intervention is the key to unlocking the reading process for the child before frustration and anger sets in. A child’s reading problem must be addressed as soon as possible because the research indicates the younger child will react more positively to the reading intervention. Kindergarten and first grade are critical points as most long-term problems with reading can be prevented. We know that approximately 95 percent of children who have difficulties in reading can reach grade level if they are helped within the first two years of elementary school. Unfortunately, the gap between struggling readers and typical readers widens after the second grade. As a result, it is more difficult to remediate a reading problem once a child falls behind.

Ellie and Katie’s parents initially sought help from their pediatrician. Their physical, vision, and hearing examinations were normal. Their second step was to consult with me, a neuropsychologist. I told Ellie’s parents that their daughter lacked the ability to distinguish sounds within words and syllables. Ellie had trouble processing the sounds of speech, called phonemes. Katie’s father was told his daughter struggled when blending sounds together and she had problems sounding out unfamiliar words. She also exhibited problems with attention, which made reading even more difficult. I suggested help from a reading specialist. The parents learned there were many reading programs that were evidence-based (programs that work) and explicit and systematic in their approach. We know that both students will benefit from early intervention.

We can truly help our children if we intervene at an early age. Trust your gut if you think something is “a little off.” You know your child best of all. Voice your concerns to your child’s teacher and pediatrician. Remember: helping your child at a young age will save you and your child much frustration in the years to come.

Karen Schiltz is the co-author of Beyond The Label: A Guide to Unlocking a Child’s Educational Potential and Associate Clinical Professor (volunteer) at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Behavior at the University of California, Los Angeles. She has over 26 years of experience assessing children and young adults with developmental, medical, and emotional disorders and maintains a private practice in Calabasas, California. She blogs for Psychology Today at “Beyond the Label.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The Roman Republic: Not just senators in togas

The Roman Republic: A Very Short Introduction

By David M. Gwynn

When we gaze back at the ancient world of the Roman Republic, what images are conjured in our minds? We see senators clad in togas, and marching Roman legions. The Carthaginian Hannibal leading his elephants over the Alps into Italy, Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon and his murder on the Ides of March. These images are kept fresh by novels and comic books, and by television series like Rome and Spartacus: Blood and Sand. Nor are we the first to seek inspiration in Republican Rome. The last years of the Republic gave life to two of Shakespeare’s most compelling plays, Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra, and perhaps the most famous speech in the Shakespearean canon (‘Friends! Romans! Countrymen! Lend me your ears’). The Founding Fathers of the United States of America took Rome as their model in drafting the US Constitution, while the French Revolution drew upon the same ideals with dramatically different results. Across two thousand years, each passing generation has turned to the Roman Republic in search of lessons to apply to their own times.

When we gaze back at the ancient world of the Roman Republic, what images are conjured in our minds? We see senators clad in togas, and marching Roman legions. The Carthaginian Hannibal leading his elephants over the Alps into Italy, Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon and his murder on the Ides of March. These images are kept fresh by novels and comic books, and by television series like Rome and Spartacus: Blood and Sand. Nor are we the first to seek inspiration in Republican Rome. The last years of the Republic gave life to two of Shakespeare’s most compelling plays, Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra, and perhaps the most famous speech in the Shakespearean canon (‘Friends! Romans! Countrymen! Lend me your ears’). The Founding Fathers of the United States of America took Rome as their model in drafting the US Constitution, while the French Revolution drew upon the same ideals with dramatically different results. Across two thousand years, each passing generation has turned to the Roman Republic in search of lessons to apply to their own times.

Click here to view the embedded video.

At the heart of history’s fascination with the Roman Republic lies a paradox. After the expulsion of the last of its legendary seven kings in 510 BC, Rome evolved a unique constitution intended to prevent any return to tyrannical autocracy. Power was shared between the elected magistrates who ran the daily business of government, the popular assemblies which conducted elections and approved laws, and the Senate which debated all major decisions and was in effect the Republic’s ruling body. The result was a stable, conservative, but adaptable form of government that far surpassed the city-states of contemporary Greece. The Republic wasn’t a democracy and far less vulnerable to popular whims than classical Athens, and possessed a practical flexibility that the equally militaristic Spartans lacked. On the battlefield the Roman legion in turn superseded the Greek phalanx, and one by one Rome defeated Carthage and the Hellenistic successors to Alexander the Great. When we think of conquering Roman legions we tend to think of the Roman Empire, but it was the Republic that brought the Mediterranean under Roman rule.

Yet this juggernaut, the most powerful state that the ancient world had ever known, collapsed under the burden of its own success. The fall of the Republic was not due to external attack, for no enemy remained that posed a serious threat to Rome. On the contrary, the Republic’s collapse was driven by the same forces that underlay its triumph. The senatorial aristocracy who dominated Republican life competed from birth for prestige and to surpass the achievements of their ancestors. Desire for dignitas and gloria, the cardinal values of the Roman elite, became ever greater as Rome expanded and the stakes of competition increased. At the same time, the vast wealth amassed through Rome’s conquests brought social and economic crisis that gave ambitious nobles new opportunities. Warlords commanding private armies duelled for supremacy, from Gaius Marius and Cornelius Sulla to Pompeius Magnus and Julius Caesar, and the Republic disintegrated into chaos and civil war.

Like all great historical epics, the Republic’s fall was not a story of inevitable or irreversible decline. Republican champions sought to turn back the tide. The Gracchi brothers aspired to social and economic reform, and were murdered for their pains. Cicero raised Roman oratory and philosophy to new heights and offered moral guidance to restore stability to the Republic, although in his priceless letters he reveals a more personal and at times vindictive side (‘How I should like you to have invited me to that most gorgeous banquet on the Ides of March’). Ambition and desire for power, however, proved too strong. Julius Caesar took the title dictator after defeating Pompeius Magnus, and Caesar’s murder by Brutus and the ‘Liberators’ in 44 BC merely plunged Rome into another decade of conflict. Finally, Caesar’s adopted son Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus defeated Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BC, and four years later took the name Augustus. The Roman Republic, a state whose very raison d’être had been to prevent autocracy, had given way to the Roman Empire.

Like all great historical epics, the Republic’s fall was not a story of inevitable or irreversible decline. Republican champions sought to turn back the tide. The Gracchi brothers aspired to social and economic reform, and were murdered for their pains. Cicero raised Roman oratory and philosophy to new heights and offered moral guidance to restore stability to the Republic, although in his priceless letters he reveals a more personal and at times vindictive side (‘How I should like you to have invited me to that most gorgeous banquet on the Ides of March’). Ambition and desire for power, however, proved too strong. Julius Caesar took the title dictator after defeating Pompeius Magnus, and Caesar’s murder by Brutus and the ‘Liberators’ in 44 BC merely plunged Rome into another decade of conflict. Finally, Caesar’s adopted son Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus defeated Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BC, and four years later took the name Augustus. The Roman Republic, a state whose very raison d’être had been to prevent autocracy, had given way to the Roman Empire.

In the modern world where change comes ever more rapidly, it is hardly surprising that our attention is drawn above all to the drama of the Republic’s final years. But there was more to the Republic than senators and legions. To understand ancient Rome we need to look deeper: at the women whose crucial roles our male-dominated sources conceal, at the slaves upon whose labour Roman society depended, at the religious values and customs that defined what being Roman meant. Popular culture no less than academic scholarship can play an essential role in bringing the Roman Republic to life, and in doing so allow us to seek our own lessons from the triumphs and tragedies of the Republic and Rome’s transformation into Empire.

David M. Gwynn served as Tutor in Greek History at Auckland University (1998) and as Lecturer in Greek and Roman History at Massey University (1998-9), before coming to Oxford to commence doctoral studies in 1999. Gwynn’s doctoral thesis, on the polemic of Athanasius of Alexandria and the “Arian Controversy”, was completed in 2003. He then took up a Junior Research Fellowship at Christ Church, Oxford, which he held until 2007. During that time he taught a number of courses in the Faculties of Classics, Modern History, and Theology, and published his thesis with the OUP as the monograph The Eusebians. Upon leaving Oxford in 2007 Gwynn took up the post of Lecturer in Ancient and Late Antique History at Royal Holloway, University of London, where he remains to this day. He was promoted to Reader early in 2012. The Roman Republic: A Very Short Introduction publishes this month.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 23, 2012

Into the arena: Defending politics at the Edinburgh International Book Festival

The world famous Edinburgh International Festival has kicked off, beginning three weeks of the best the arts world has to offer. The Fringe Festival has countless alternative, weird, and wacky events happening all over the city, and the Edinburgh International Book Festival is underway. Throughout the Book Festival we’ll be bringing you sneak peeks of our authors’ talks and backstage debriefs so that, even if you can’t make it to Edinburgh this year, you won’t miss out on all the action.

By Matthew Flinders

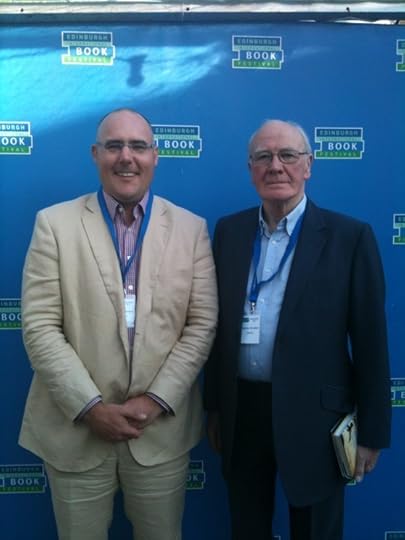

Matthew Flinders and Sir Menzies Campbell

“It is not the critic who counts,” Theodore Roosevelt famously argued, “not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena…who spends himself in a worthy cause.” The arena in question was The Guardian’s ‘Rethinking Democracy’ debate at the Edinburgh International Book Festival and my ‘worthy cause’ was an attempt to defend democratic politics (and therefore politicians) from the anti-political environment in which it finds itself today.

With Sir Menzies Campbell at my side, I drew upon Bernard Crick’s classic In Defence of Politics to suggest that although politics is — like life — inevitably messy, it remains an innately civilizing activity that deliver far more than many ‘disaffected democrats’ appear to recognize. Too be honest I went too far; I dared to suggest that some sections of society had become ‘democratically decadent’ in the sense that they took their democratic rights and the fruits of collective engagement for granted. If politics is failing, could it be that the public is demanding too much and contributing too little?

Many people disagreed. (Indeed, I would have been disappointed if they had not and the subsequent debate would have been far less enjoyable!) And yet what was arguably more interesting was the degree of general agreement about the need to rethink the boundaries and limits of politics. Boundaries in the sense of how we recruit and what we expect from our politicians; the capacity of the nation state in an increasingly globalised and inter-dependent world; the challenges of climate change, resource depletion and population growth; and the general public’s willingness and capacity to engage in policy-making and debate. Beyond boundaries and limits, however, The Guardian’s ‘Rethinking Democracy’ debate underlined the simple fact that the public do not ‘hate’ politics. It is closer to the truth to suggest that what is needed are deeper and more energetic ways of revitalizing democracy. We need brave politicians and journalists who reject the belief that ‘only bad news sells’; and we need to reject the faux democracy offered by the brave new ‘on-line digital democracy.’ Democratic politics is hard and its tiresome. It revolves around squeezing collective decisions out of a range of competing and irreconcilable demands. It grates and it grinds and is, to some extent, always destined to disappoint. And yet it remains a quite beautiful social activity.

So… to the woman who said I’d made her so angry she wanted to “punch me on the nose,” I can only apologize and smile in equal measure; to the man who bemoaned the rise of career politicians I can only sympathize and agree; and to the young woman who asked me about whether she might pursue a career in politics I can only say that we need more people like her with the courage and conviction to ‘step into the arena.’

In case you missed the debate: in this video, Matthew Flinders takes the fight to those who say politics is broken.

Matthew Flinders is Professor of Parliamentary Government & Governance at the University of Sheffield. His book Delegated Governance and the British State (Oxford University Press, 2008) was awarded the W.J.M. Mackenzie Prize 2009 for the best book in political science published that year, and since then he has acted as an advisor to the Government of Thailand on behalf of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and also held a Visiting Fellowship in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Sydney. Author of Defending Politics (2012), he is also co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of British Politics (2009) and author of Multi-Level Governance (2004) and Democratic Drift (2010). Read Michael Flinders’ previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Logo courtesy of Edinburgh International Book Festival

Did the government invent the Internet?

Did the government invent the Internet? In a 23 June 2012 Wall Street Journal article, journalist L. Gordon Crovitz answered “no.” “It’s important to understand the history of the Internet,” Crovitz contended, “because it’s too often wrongly cited to justify big government.” Crovitz gave the credit instead to researchers at Xerox PARC who in the 1970s developed the Ethernet to link different computer networks. Their goal was to make it easier to make copies on Xerox’s photocopying machines. The earlier computer network that the US Defense Department had built (the ARPANET) is not “the Internet” because it linked computers, not computer networks.

Is Crovitz right? Only if you anachronistically confine the Internet narrowly to applications popularized since its commercialization in 1995. The basic idea — the linkage in a network of heterogeneous computers that had originally been designed as standalone devices — had been a goal of engineers at the US Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) since 1969. ARPA made a public demonstration of its network in 1972.

Why ARPA wanted to link computers is a complicated story. Computer memory in 1969 was scarce (remember Y2K — two digits for years instead of four?) and the long-distance Bell telephone network was underutilized (largely as a result of government regulation). Government engineers, working in tandem with government contractors, speculated that, if it were possible to link together the computational power of computers hundreds of miles from each other (which at the time were stand-alone machines that operated independently of each other), it might be possible to facilitate the calculations necessary to guide intercontinental ballistic missiles.

They also thought it would be fun to try.

The commercialization of the Internet — which no one envisioned at the time — was an unintended, though largely happy consequence of this government decision. The historian of technology Thomas P. Hughes put it this way: “Throughout the history of ARPANET, we shall discover government funding playing a critical role in one of the opening acts of the so-called computer and information age. The part played by the government, namely the military, in this historical technological transformation raises a perplexing question: is government funding needed to maintain the revolutionary development of computing and is government funding needed to generate other technological revolutions in the future?”

Richard R. John is a Professor at Columbia University in the City of New York and a contributor to To Promote the General Welfare: The Case for Big Government, edited by Steven Conn. He is a historian of communications who specializes in the political economy of communications in the United States. His publications include many essays, two edited books, and two monographs: Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (1995) and Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications (2010).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Money and politics: A look behind the news

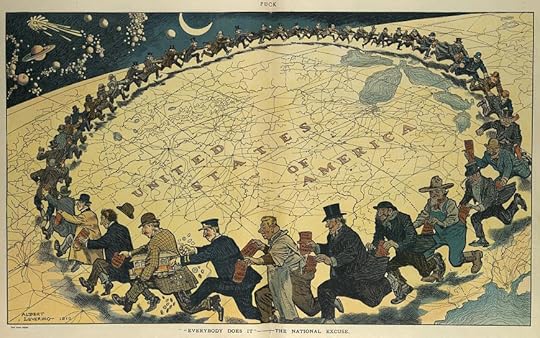

In the final months of a presidential election campaign, the prevailing political talk, amid an ambience of cynicism and indignation, turns unhesitatingly to money. American voters understand that economics and politics remain interpenetrating. Whatever happens in either one of these seemingly discrete realms, especially when money is involved, more or less substantially impacts the other.

Still, if scholars and politicos were to look behind the talk, beyond the ritualized economic and political orthodoxies of the moment, they could uncover something genuinely vital, stunningly obvious, but somehow also still neglected. The core problems of generalized economic weakness and expanding social inequality, they would discover, are not truly fiscal, but human.

Personal consumption comprises an overwhelmingly disproportionate amount of the GDP growth rate. By itself, however, this is not newsworthy. Yet by simple deduction, Wall Street’s volatility and fragility, and therefore America’s politics and elections, are ultimately a product of a society that ‘requires’ hyper-consumption.

Below the tangible surfaces of timeless and widespread manipulations, America’s underlying market difficulties are rooted in a deep dependence upon Main Street’s craving for goods. From the standpoint of any needed economic recovery, and therefore also the political fortunes of our current presidential candidates, this skillfully choreographed pattern of desire will always prove to be relevant, or even determinative. Depending upon the particular candidate and political party, of course, it will turn out to be more or less helpful.

We Americans are presumed to be what we buy. There is nothing remotely controversial about this demeaning assertion. Earlier, Adam Smith and Thorsten Veblen, among others, established the blurry nexus between money and self-esteem as an integral part of their respective economic theories. This corrosive linkage is now indispensable to our political campaigns, both at the utilitarian level of successfully marketing each candidate to the most voters, and also with regard to each candidate’s explicitly wealth enhancing or income-related promises.

This crude orientation to money and politics isn’t distinctly American. Rather, the universal problem of hyper-consumption is the embarrassing foolishness of linking feelings of self-worth to ownership of shiny goods. In any society where one’s perceived value is determined by observable consumption, the derivative economy and polity are inevitably built upon sand.

Do we want a genuinely fair and democratic society? Do we prefer that our presidential candidates be animated by more than a visceral political inclination to pledge greater personal wealth to every voter? If so, then we must first reorient our American system from its thoroughly corrupted ambience of mass taste, and toward a more conscientiously cultivated environment of thought and feeling.

Adam Smith had argued, in his Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), that a system of “perfect liberty” could never be based upon “mean rapacity” and “needless” consumption. On the contrary, said Smith, who remains a fashionable mainstay of conservatives, the laws of the market, driven by competition and a consequent “self-regulation,” demand a principled disdain for all vanity-driven consumption. For Adam Smith, “conspicuous consumption” — a phrase that would be used far more devastatingly later by Thorsten Veblen — could never be a proper motor of economic or social improvement, yet it is now offered as a solution to economic woes and an inducement for political support.

Wall Street and Washington remain wholly dependent upon the self-destructive imitations of mass society. Such a mutually corrosive dependence can never succeed, either in economics or in politics. Instead, we must first create conditions whereby each American can somehow feel important and alive without abjectly surrendering to manufactured images of power and status. If we fail, the most blatantly injurious connections between money and politics will continue to proliferate.

Without appropriately altered conditions, millions of Americans will continue to seek refuge from the excruciating emptiness of daily life in mind-numbing music, mountains of drugs, and oceans of alcohol. Insidiously, without any political impediments, the resultant brew will swell and overflow, drowning entire epochs of political theory, art, literature, and even sacred poetry.

Despite the endless infusions of money into politics, America is now a palpably unhappy society, one where the citizens can rarely find authentic meaning or personal satisfaction within themselves. Only this socially crushed individualism can become the starting point for repairing what is fundamentally wrong with our politics and society. All else, including fiscal contaminations of democratic politics, is epiphenomenal. All else is merely what philosophers, since Plato, have called “shadows of reality.”

Were he alive today, Plato would recognize our problems of money and politics as a “sickness of the soul.” The solution to these problems, he would have understood, is not simply to elect new leaders, or identify additional statutory limits on political contributions and donations. Instead, it must be to make the souls of the citizens better.

Louis René Beres was educated at Princeton (Ph.D., 1971), and is Professor of International Law at Purdue University. The author of ten major books on world affairs, his columns appear often in major American, European and Israeli newspapers. Dr. Beres was born in Zürich, Switzerland, on 31 August 1945. He is a frequent contributor to OUPblog.

To learn more on this subject, check out The Oxford Handbook of Political Philosophy, edited by David Estlund. Even though political philosophy has a long tradition, it is much more than the study of old and great treatises. Contemporary philosophers continue to press new arguments on old and timeless questions, but also to propose departures and innovations. The field changes over time, and new work inevitably responds both to events in the world and to the directions of thought itself. The latest edition includes new issues in political philosophy, such as Race, Historical Injustice, Deliberation, Money and Politics, Global Justice, Human Rights, and Ideal and Non-Ideal Theory.

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for the next four weeks in anticipation of the Republican and Democratic National Conventions, and American presidential race. This week our authors are tackling the issue of money and politics. Read the previous post in this series: “The Declaration of Independence and campaign finance reform” by Alexander Tsesis, “Money for nothing? The great 2012 campaign spending spree” by Andrew Polsky, and “Five things you may not know about leadership PACs” by Kristin Kanthak.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about The Oxford Handbook of Political Philosophy on the

Richard Causton, the EUYO, and the Cultural Olympiad

Composer Richard Causton worked with the European Union Youth Orchestra on Twenty-Seven Heavens, premiering in the UK tonight at Usher Hall in Edinburgh as part of the Edinburgh International Festival.

Causton composed the work, which he describes as a Concerto for Orchestra, for the 2012 Cultural Olympiad festivities celebrating the UK, London, and the Olympics. The orchestral work is one of 20 new pieces specially commissioned for the occasion from some of the UKs finest musical talent, and it is the first new work ever commissioned by the European Union Youth Orchestra.

Twenty-Seven Heavens takes inspiration from the writer William Blake’s epic poem, Jerusalem. Jerusalem is very much rooted in London, drawing parallels between aspects of the poet’s mythological world and various districts of London — a particularly appropriate idea for a work celebrating the culture of the 2012 Olympic host city!

The world premiere of Causton’s exciting new orchestral composition took place in Amsterdam on 20 August 2012, with the UK premiere following tonight in Edinburgh on 23 August, and a third performance in Darmstadt, Germany on 25 August, each with Gianandrea Noseda conducting.

In the following film by Black Swan, composer Richard Causton and members of the European Union Youth Orchestra reveal the collaborative process between composer and performers in the creation and preparation of a new piece of music.

Click here to view the embedded video.

In this film for the Edinburgh International Festival, composer Richard Causton explains the connections between musicians and athletes, and writing a piece for the Cultural Olympiad.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Richard Causton was born in London in 1971 and studied at the University of York, the Royal College of Music and the Scuola Civica in Milan. He has worked with world renowned performers such as the BBC Symphony Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Sinfonieorchester Basel, London Sinfonietta, and the Nash Ensemble. He has been the recipient of several awards, including First Prize in the International ‘Nuove Sincronie’ competition, the Mendelssohn Scholarship, a 2004 British Composer Award in the Best Instrumental Work category for Seven States of Rain in 2004, and the 2006 Royal Philharmonic Society Award for Chamber-Scale Composition for Phoenix. In September 2012 he will take up the post of Professor of Composition at Cambridge University.

Anwen Greenaway is a Promotion Manager in Sheet Music at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this sheet music on the

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition.

Image credit: Richard Causton. Photo by Katie Vandyck.

Short answers to snappy questions about sports doping

The world famous Edinburgh International Festival has kicked off, beginning three weeks of the best the arts world has to offer. The Fringe Festival has countless alternative, weird, and wacky events happening all over the city, and the Edinburgh International Book Festival is underway. Throughout the Book Festival we’ll be bringing you sneak peeks of our authors’ talks and backstage debriefs so that, even if you can’t make it to Edinburgh this year, you won’t miss out on all the action.

By Chris Cooper

Largely because of the furore about the Chinese swimmer, Ye Shewin, I have spent a lot of time in TV and radio studios recently. My book, Run, Swim, Throw, Cheat is really about the science of doping now and what could happen in the future. But of course I get asked a lot of more general questions as well:

1. What drugs do athletes use and do they work?

I usually answer this with the unholy trinity: anabolic steroids for power events like sprinting, blood doping for endurance events, and amphetamines (or similar) to prevent fatigue. If pressed I say that the strongest evidence for benefit is using blood doping (whether transfusions or EPO injections) and anabolic steroids, especially in female athletes.

2. How many athletes dope?

Always a tricky one: the number that test positive is around 0.5 – 1%. Although this could be an overestimation, as testers target the more suspicious athletes, I think it is more likely to be an underestimation. It would be safe to say that somewhere between 1 and 10% have tried doping in their career at any time. Of course, this number varies dramatically between sport and country. But I don’t think it is a majority and we need to recognize that.

3. Who is winning the war on doping?

I always say this is impossible to answer; how would we know if the dopers were using an undetectable compound? But it is likely the dopers and testers are on top at different times. Given the identity of all elite athletes is known — and their number is relatively small compared to all criminals in the world — if enough money and police intelligence was thrown at the problem it would make it very hard for the dopers to succeed routinely. But maybe this money is better spent on building a new hospital or improving our schools instead?

4. Are athletes gene doping?

Although theoretically possible, like most scientists I think it very unlikely this is successfully being used at present. There are likely more effective, and cheaper, ways to cheat anyway.

5. Why not stop spending all this money in an unwinnable anti-doping war and let athletes do whatever they want to succeed?

I answer this, by saying, that we should be careful what we wish for. The best example is anabolic steroid use in female athletes. Unrestricted use led to the health problems we saw in East German athletes. We may not like the look of the competition we create. If we allow steroid use under controlled medical supervision we may have healthier competition for those obeying the rules. But there will still be a few who want to go further. How can we check this without an effective anti-doping regime? The same system needs to be in place, just working with a different set of goalposts.

6. Why not have an Olympics competition for “normal” athletes and another for those using whatever they can to be the best that they can be?

This is an easy answer. Some of the methods tried in the “doping” games would involve illegal drugs. Many of the athletes would live shortened lives in the pursuit of victory. Which competition do you think Coca-Cola or McDonalds would sponsor? Which would the BBC or US networks cover? This kind of question is philosophically valid to ask, but practically a waste of time to think about. It ain’t going to happen.

I will be talking about this, and more, including my demonstration of blood doping using red wine, at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on August 27.

Chris Cooper is Head of Research, Sports and Exercise Science at the University of Essex and the author of Run, Swim, Throw, Cheat: The Science Behind Drugs in Sport. He is a distinguished biochemist with over 20 years research and teaching experience. He was awarded a PhD in 1989, a Medical Research Council Fellowship in 1992, and a Wellcome Trust University Award in 1995. In 1997 he was awarded the Melvin H. Knisely Award for ‘Outstanding international achievements in research related to oxygen transport to tissue’ and in 1999 he was promoted to a Professorship in the Centre for Sports and Exercise Science at the University of Essex. His research interests explore the interface of scientific disciplines. His current biochemical interests include developing artificial blood to replace red cell transfusions. His biophysics and engineering skills are being used in designing and testing new portable oxygen monitoring devices to aid UK athletes in their training for the London 2012 Olympics. In 1997 he edited a book entitled Drugs and Ergogenic Aids to Improve Sport Performance.

Chris Cooper on: The Science Behind Drugs in Sport. See also this quiz: Test Your Smarts on Dope.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Logo courtesy of Edinburgh International Book Festival

Image credit: ‘Pills’ by Ayena [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

August 22, 2012

Rethinking Europe: Do we need a European Community anymore?

The world famous Edinburgh International Festival has kicked off, beginning three weeks of the best the arts world has to offer. The Fringe Festival has countless alternative, weird, and wacky events happening all over the city, and the Edinburgh International Book Festival is underway. Throughout the Book Festival we’ll be bringing you sneak peeks of our authors’ talks and backstage debriefs so that, even if you can’t make it to Edinburgh this year, you won’t miss out on all the action.

By David Ellwood

At first sight it looked like an incongruous debate for Edinburgh. The only debate dedicated to Europe included three unusual debaters. Matthias Politycki is a distinguished German novelist and literary critic, whose latest book portrays London, its pubs, and its culture of real ale. José Rodrigues Dos Santos is one of Lisbon’s best-known political commentators, but also a man who writes novels which are part-spy thrillers, part-science fiction. (Both authors enjoy English translations of at least some of their work.) And finally myself, on the promotional tour for The Shock of America, on the history of Europe’s effort to cope with America’s power as a force for innovation — from Buffalo Bill to Google, from Hollywood to Obama, etc. How to reconcile such different impulses and points of view?

Knowing that Book Festival audiences are discreet and tolerant folk, I tried to introduce the notion that the history of European integration couldn’t be understood without its American dimension. I pointed out that it was the Marshall Plan which turned European integration into a serious political and economic project, in fact it was the string attached to Marshall aid. Why? Because the Americans thought by caging Europe’s evil genie — nationalism — in a tight federal cage they would neutralize once and for all the forces which had produced two world wars and three totalitarianisms. They also thought that a united western Europe would be one best equipped to fight Soviet communism with economic weapons. I went on to point out that the Americans have always supported European integration and still do.

European flag outside the Commission. Photo by Xavier Häpe, 2006. Creative Commons License.

But I also tried to show that this great American push had ended up dividing Europeans more than uniting them, and that the dividing forces have indeed proven stronger than the uniting ones. This is largely because of the attitude of the British. As long as the British have remained so doggedly negative about the process in general, while the French and Germans have been so dedicated to it, the whole project has been hobbled. The British have long preferred their American connection, even as the Americans have told them, decade after decade, to stop moaning and get on the European bus.

However, I pointed out that Britain’s stubbornness on sovereignty was only the most extreme version of a form of behavior the rest in the EU all practice at some time or other. Specifically Paris and Berlin share with London the conviction that Brussels must never acquire more power than they imagine they possess as single nations in the world. This explains why the Euro project was born so misshaped, and why the Germans and the French hesitate still to take the decisive step towards combining their fiscal and monetary policies (and so re-launch their common currency).

Our Portuguese colleague, however, would have none of this. For him the Euro scheme was born from a wicked trade-off between the French and the Germans at the end of the Cold War. François Mitterand had got support for his pet idea for relaunching French hegemony in Europe: monetary union. In return the French gave their consent to Helmut Kohl’s plan for instant German re-unification. The whole thing had only kept going by bluff and throwing cheap money at indigents like the Greeks, Italians, Spanish & co. The result was massive public debt, which would only be solved by defaults or massive inflation. No wonder the admirable German central bank said ‘no’ to such a prospect, with German memories of hyper-inflation (90 years ago). Only proper political unification could cope with such dilemmas, and this seemed totally unlikely as politicians were animals who only thought of the next election and their short-term advantage.

Like myself, Matthias Politiycki tried to add a broader, cultural dimension to all the efforts. This inevitably meant counting in the American challenge in all its forms, including popular and trash culture. He insisted that the Germans had long dreamed of a ‘United States of Europe’, but feared that they had wound up with their own version of Americanisation. Why some German poets even write in English, unapologetic for the rubbishy results they produced. There would always be an American question as well as a European one in Germany’s never-ending identity debates. The great shame was that Britain never offered any help in this search to create an alternative to the American pole. Always so negative and detached vis à vis Europe, when it came to the US, the Brits looked one of Donald Duck’s over-eager nephews. The best hope lay in the new generations which went through the Erasmus project, who travelled everywhere on low-cost airlines or rail tickets, who looked for work wherever it could be found.

When given its chance the audience — with very few of the afore-mentioned young people in it — soon supplied prompts for more debate. Wasn’t the EU a bureaucratic monster? Why couldn’t the whole thing be more democratic? What if Greece did default? Shouldn’t the Germans keep on shouldering the EU burden to expiate their guilt for the world wars they’d caused? (There were cries of “shame, shame” from other audience members when this thought was aired.) Between politics, monetary affairs and cultural questions, it was hard to find a central unifying thought or theme among all the notions. Perhaps a certain bemusement had crept in by the end. How could three such ‘experts’, all basically in favour of the European project, have come up with such disparate, even dissonant accounts of what had gone wrong and what the prospects might be? Let’s hope next year’s Book Festival can face a cheerier, clearer prospect when it looks across the Channel to Europa.

David Ellwood is the author of The Shock of America: Europe and the Challenge of the Century, Rebuilding Europe: Western Europe, America and Postwar Reconstruction, and Italy 1943-1945: The Politics of Liberation. The fundamental theme of his research – the function of American power in contemporary European history – has shifted over the years to emphasise cultural power, particularly that of the American cinema industry. He was President of the International Association of Media and History 1999-2004 and a Fellow of the Rothermere America Institute, Oxford, in 2006.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Logo courtesy of Edinburgh International Book Festival

Meles Zenawi: In his own words

In the rush to judgement on the record and the legacy of Meles Zenawi as Ethiopia’s leader for the past two decades, the man himself has barely left the shadows. Yes, he achieved record economic growth for his country, and yes, he was a force for stability and an ally in the West’s ‘war on terror,’ and no, he was certainly not a liberal democrat.

He was also a much more attractive and significant figure than these achievements and positions suggest. His work rate was punishing enough to have cost him his health (he was only 57) and his political predominance owed as much to an extraordinary intellect as to his control over the apparatus of party and state. Reflecting his country’s tradition of independence and its inclination to keep foreigners in their place, he articulated a vision of an Africa where the West no longer ruled the world.

Educational attainment is no indicator of political capacity, but Meles’ academic exploits were exceptional. At 19 he dropped out of his medical degree in Addis Ababa to become a guerrilla fighter. Seventeen years later he took up his studies again (and insisted most of his young cabinet do the same) through the Open University, and got one the best business degrees they have ever awarded. He went on to a master’s degree at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, an undertaking inconveniently interrupted by the war with Eritrea.

His thesis, appropriately, was on the functioning of African economies. As he explained to me, it “was primarily intended for our own local consumption to see if our policies could stand up to the rigour of some academic scrutiny.” He got his Master’s in 2004.

Meles famously had no small talk. Chris Mullin, as a junior Foreign Office Minister, tells how he was ushered into his office after a dramatic flight across the country from the Red Sea coast. “Spectacular country, Prime Minister,” ventured Mullin, to break the ice. Meles smiled and said nothing. “It must be very difficult to govern,” offered Mullin in desperation. “Spectacularly difficult,” replied Meles. They then got down to business.

What he lacked in small talk he made up for in willingness to debate and argue, more enthusiastically with foreigners than with Ethiopians. In researching Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia since Live Aid, I trailed Meles to a series of ‘Farmers’ Festivals’ where he would give up a day to listen to speeches and hand out prizes. I heard him lecture on African development to several hundred economists, foreigners and Ethiopians, and then take questions for more than two hours.

It was after one of these occasions that I got my introduction. I told him who I was, what I was doing, and said I wanted to conduct extensive interviews with him. He beamed good-naturedly. “I would be honoured,” he said in as subtle a lack of formal commitment as I have ever received as a journalist. In the event I saw him for a total of four hours, and was free to tackle all the awkward questions, from Ethiopia’s image around the world to democracy and human rights and his plans to hand over power.

Here are some of the more surprising and challenging observations that Meles made to me. They help account perhaps for the regard in which he was held by fellow leaders in Africa and beyond.

On the shame and embarrassment of his country’s association with hunger and starvation:

“Humiliation can be a very powerful motivation for action and therefore I don’t hate the fact that we get humiliated every day so long as it’s based on facts. If we feel we deserve to be treated like honourable citizens of the world, then we have to remove that source of shame.”

On the failure to respond effectively to the 2008 famine in southern Ethiopia:

“That was a failure on our part. We were late in recognising we had an emergency on our hands. We did not know that a crisis was brewing in these specific areas until emaciated children began to appear.”

On how western aid agencies were also to blame:

“They did not respond quickly. They didn’t have the means to respond quickly. But they were exaggerating, and it appears to us that they were deliberately exaggerating. My own interpretation is because they have to shock and awe the international community to get money.”

On the 2015 deadline for realizing the main Millennium Development Goal:

“As far as halving poverty is concerned, we will achieve it. I have no doubt about it. I believe by 2025 we will be a middle income country with a per capita income of at least $1,000 a year and at around that time, slightly before perhaps, we will be completely free of aid of any variety.”

On the merits and limitations of democracy:

“We believe that democracy, good governance and transparency and fighting corruption are good objectives for every country, particularly for developing countries. Where we had our differences with the so-called neoliberal paradigm is first on the perception that this can be imposed from outside. We do not believe that is possible. Internalization of accountability is central to democratisation. The state has to be accountable to the citizens, and not some embassy or foreign actor.”

On the pressure from western aid donors to adopt free market economics:

“Our argument has been that the neoliberal model does not work in Africa. In developed countries it is a perfectly legitimate alternative (or it was — it needs serious modifications now). In the case of under-developed economies without the push of the state, an effective developmental state, it is very unlikely that the markets that do exist are going to function efficiently and push the country forward.”

On the restrictions imposed on foreign-funded Non Government Organisations:

“These NGOs were initially seen as an antidote to what was seen as the main problem in Africa — the bloated state. This was supposed to be an alternative. You reduce the role of the state, including your social services, and you encourage NGOs to provide as much of the public services as possible. In the end we argue that the NGOs have turned out to be alternative networks of patronage. NGOs have not provided an alternative good governance network.”

On his wish to step down from power:

“It’s not just about Meles. It’s about the old generation of leadership, the armed struggle leadership. There is consensus that the leadership has to go. Sometime during the next term [2010-2015] the whole leadership has to go.”

Meles’ work was not quite done. It is still unclear how far the transition to a new, younger leadership has progressed. It is still less clear whether sufficiently strong party and state institutions are in place to withstand the shock of his departure and the challenges that the new hierarchy will face. The ultimate objective, he told me in 2009, had always been for the ruling party to make itself redundant. Was that still the aim? “If it doesn’t do that, it has failed absolutely — miserably failed in its objective.”

Meles Zenawi Asres

8 May 1955 – 20 August 2012

Peter Gill is the author of Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia since Live Aid, now in paperback. He has specialized in developing world affairs for most of his career, an interest that began as a VSO teacher in Sudan and his first visit to Ethiopia in the 1960s. In the 1970s he was South Asia and Middle East Correspondent for The Daily Telegraph. For TV Eye and This Week, he made films in Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation, in Gaza and Lebanon, in South Africa under apartheid and in Uganda, Sudan, and Ethiopia during the famine years. He made Mr. Famine for ITV about corruption at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation and Clare’s New World about Clare Short, DFID and its first White Paper, Eliminating World Poverty. From 1999-2003, he headed the India office of the BBC World Service Trust. His first project partnered Indian broadcasters in leprosy campaigning that brought 200,000 patients forward for cure; this led to a L5 million project on HIV/Aids awareness. He has is author of Drops in the Ocean, A Year in the Death of Africa and Body Count.

Image credit: DAVOS/SWITZERLAND, 26 JAN 12 – Meles Zenawi, Prime Minister of Ethiopia speaks during the session ‘Africa — From Transition to Transformationy’ at the Annual Meeting 2012 of the World Economic Forum at the congress centre in Davos, Switzerland, January 26, 2012. Copyright by World Economic Forum. Creative Commons License. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers