Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1032

August 16, 2012

Even more facts about the Silk Road

The “Silk Road” was a stretch of shifting, unmarked paths across massive expanses of deserts and mountains — not a real road at any point or time. I previously examined the historical documents and evidence of the silk road, but here are a few more facts from camels to Marco Polo on this mysterious route.

When were the peak years of the Silk Road trade?

The peak years of the Silk Road trade were between 500 and 800 C.E., after the fall of the Han dynasty and Constantinople replaced Rome as the center of the Roman empire. The Tang dynasty stationed troops in Central Asia and many Iranians came to the Tang territory at that time.

Who were the most important traders on the Silk Road?

Government officials were very important. Rulers strictly supervised the movement of people and trade, and played a major role as the purchasers of goods and service. During the periods when the Chinese stationed troops in Central Asia — primarily during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220 C.E.) and the Tang (618-907 C.E.) — trade boomed. When they did not, trade declined. Most of the private traders were peddlers who traveled on small circuits, selling many locally produced goods.

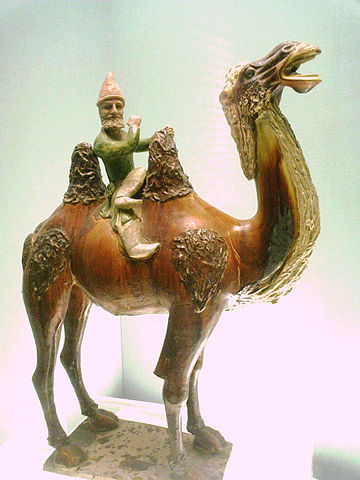

Westerner on a camel, Chinese Tang Dynasty (618-907). Shanghai Museum. Photograph by PHG. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Was the camel the most frequently used animal?No, donkeys and horses always outnumbered camels. Camels could carry loads across the desert, but they were difficult and irascible, and most travelers preferred to ride horses and donkeys or to travel in carts drawn by them along dirt roads.

How far did most people travel on the Silk Road?

Most individual travelers moved in small circuits along the Silk Road of perhaps a few hundred miles (around 500 km) between their home and the next oasis. The Silk Road trade was a trickle trade mainly between adjacent towns, and almost never involved large camel caravans crossing great distances. The most famous exception — if not the most reliable traveler — was Marco Polo (1254-1324) who claimed to travel all the way from Europe to China by land and to return home by sea.

What is the legacy of the Silk Road?

The Silk Road provided an avenue for the transmission of ideas, technologies, and artistic motifs, and not simply trade goods. Silk Road oasis towns didn’t engage in “trading” so much as translating, absorbing, and in many instances, modifying the belief systems that passed through them. Religious practitioners, scholars, and a number of remarkable linguists in these Silk Road communities contributed to the accessibility of Buddhism, which originated in India and enjoyed genuine popularity in China, but Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, and the Christian Church of the East (based in Syria) all gained followings. Before the coming of Islam to the region, members of these different communities proved surprisingly tolerant of each other’s beliefs. Individual rulers might choose one religion over another and strongly encourage their subjects to follow suit, yet they permitted foreign residents to continue their own religious practices.

Valerie Hansen is Professor of History at Yale University. Her books include The Silk Road: A New History, The Open Empire: A History of China to 1600, Negotiating Daily Life in Traditional China: How Ordinary People Used Contracts, 600-1400, Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127-1276, and, with Kenneth R. Curtis, Voyages in World History.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

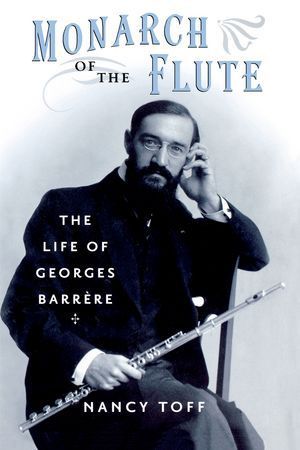

A double life: Leading flute historian and history editor Nancy Toff

One of our history editors here at Oxford University Press (OUP) has a unique second life. She is the author of two of our best-selling flute books on our music list, The Monarch of the Flute, recently released in paperback, and The Flute Book, a staple in the field and now out in its third edition. This editor is our very own Nancy Toff, and to celebrate these releases — as well as her receiving the National Flute Association’s 2012 National Service Award at the annual convention this past weekend — we sat down with Nancy for a Q&A.

How many years have you devoted to studying the flute?

I’ve been playing since the fifth grade. Who’s counting?

What drew you to the instrument?

In the fifth grade I wanted to join the band, all my friends were playing the flute, and I guess it was the right size.

Did you have any memorable music instructors? How did they influence your music career?

My main flute studies were with Arthur Lora, who had been first flutist of the NBC Symphony under Toscanini and of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. We had a total meeting of the minds; he recognized my historical interests early on and he structured lessons accordingly. Of course he gave me a very firm foundation in all the technical aspects as well. In college I studied with James Pappoutsakis, who taught me a great deal about sound production and orchestral interpretation. He was of the “monkey hear, monkey do” school and hearing him play for me once a week was a tremendous learning experience. At Harvard, Luise Vosgerchian was my professor for keyboard harmony, a real trial by fire, but I came away with a thorough grounding in harmonic analysis. What’s more, it was Luise who suggested that I write my undergraduate honors thesis on the history of the flute — and that turned into my first book, The Development of the Modern Flute.

I’ve heard that you attended Harvard along with a very famous cellist. Care to elaborate on that?

Yo-Yo Ma was a classmate of mine. He played as a section cellist in the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra — freshman year, at least — and we played together in many concerts in the residential houses. Of course he was the soloist and I was in the orchestra. He has always been a delightful, modest person despite his star qualities — a real model for young musicians (and the rest of us).

What some fans of your books might not know is that in addition to being a leading flute historian, you are an executive editor for our history list at OUP. What brought you down that career path?

A series of happy accidents. For my very first job, I wanted to work in Washington so I’d have access to the Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection in the Library of Congress. I found a job as a picture researcher for Time-Life Books, where I learned how to publish illustrated history books. After that, I held several other music and publishing jobs in New York. In 1991 OUP hired me to set up a new department to publish history books for middle school and high school students, and for a few years I also ran the trade reference department, where much of the list was in history. I did that for 15 years, and then in 2006 I moved to the academic/trade department to publish history for adults.

The Flute Book has become a classic amongst flutists since it was first published in 1996. Have there been any moments in the book’s 15+ year history that stand out as particularly memorable to you?

The Flute Book has become a classic amongst flutists since it was first published in 1996. Have there been any moments in the book’s 15+ year history that stand out as particularly memorable to you?

The fact that the cultural historian Jacques Barzun invited me to write it certainly stands out! Through the good offices of a family friend, Henry Graff, I had gone to talk with him about the possibility of writing a biography for Scribners, where he was a literary advisor. Instead, he asked me to write a companion volume to one they already had on the clarinet. Meeting Mr. Barzun was an awesome and ultimately life-changing experience.

Then it’s always fun to hear from flutists who have used the book. They come up to me at National Flute Association conventions and they send me emails. It’s always gratifying to hear that my book helped them pass their oral exams or write their program notes or find repertoire for a concert. It’s quite amazing how often it’s quoted in doctoral dissertations on the flute.

In addition to The Flute Book, you also have the paperback version of Monarch of the Flute coming out this month. Why Barrère for your first biography?

In addition to The Flute Book, you also have the paperback version of Monarch of the Flute coming out this month. Why Barrère for your first biography?

I got to “know” Barrère through Frances Blaisdell, who studied with him beginning in 1928 and wanted to do something to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of his death in 1994. I worked with her on assembling The Barrère Album, a collection of his arrangements, and did some research to learn more about him. That led to an exhibition at the New York Public Library, and I was quickly persuaded that he was a seminal figure in both French and American woodwind music, and a major figure in American musical life in general, deserving of a full biography. He had a huge influence on American flute playing and repertoire.

Do you have plans to research any other famous flutists?

Right now I’m looking into the work of Louis Fleury, Barrère’s successor as director of his Paris woodwind society. It’s too early to say if this will turn into a book, but at the very least Fleury will be the subject of several articles. The fun has just begun!

Finally, to make me feel like an underachiever, you are the archivist and past president of the New York Flute Club, have served on the National Flute Association’s board of directors, served as consultant to the Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection in the Library of Congress and the Department of Musical Instruments of the Metropolitan Museum of Art , were the curator of an exhibition on Georges Barrère at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and are the recipient of the National Flute Association’s 2012 National Service Award, along with being at full-time editor at OUP. Where do you find the time??

I make the time! Anyway I’m not the type to sit on a beach (though I do swim several miles a week in the pool). It’s a great balance — and balancing act — to have two different lives, and sometimes they overlap in neat ways. For example, one of my authors is married to a longtime member of the New York Flute Club, who owns a well-used copy of The Flute Book. He knew who I was long before I met him through OUP. Also, my travel for Oxford sometimes gets me to archives that I might not otherwise have time to visit.

And travel you certainly do! Thanks for taking the time for this Q&A, and congratulations on your award!

Alyssa Bender joined Oxford University Press as a marketing assistant in July 2011. She works on academic/trade history, literature, and music titles (and has thus worked on the marketing for Nancy’s history titles, as well as for Nancy’s own flute books!), and tweets @OUPMusic.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about The Monarch of the Flute on the

View more about The Flute Book on the

Image: Nancy Toff at a signing at the National Flute Association’s 40th Annual Convention. Photo courtesy of Nancy Toff.

Bereavement: the elephant in the room

For most of us the death of a child is unimaginable and when it happens to someone close to us, or in our community, we may have no idea of how to respond. If you’re a grandparent or close family member you may well be dealing with your own sense of loss as well as thinking about how to support the bereaved family and it’s the latter that people typically struggle with.

If you bring a group of bereaved parents together one certain thread of conversation will be about them feeling unsupported by friends and family. It’s clearly not the case that people do not care, but often they simply do not know what to say or do and there is a worry about making things worse. The starting point in trying to support bereaved parents is that the worst has already happened. There is little you can say or do, which will match the pain they are already experiencing.

You can help them by acknowledging what has happened and talking about their son or daughter, sharing your own memories of them. If you do not feel able to do this in person, send a card or a letter.

Offer practical help and support, but do not make any assumptions about what a grieving Mum or Dad might need. Check out with them whether it would be helpful to provide meals, do the garden, field calls or whatever you feel you can offer, that allows them to save their limited energy for what matters to them.

Similarly make no assumptions about how long the parents might grieve for. It will take longer than you and possibly they anticipate. Avoid the ‘still’ and ‘yet’ kind of questions, as in ‘Are you still visiting the grave every day?’ or ‘Have not you gone back to work yet, or cleared his room yet?’ These kinds of questions suggest that there is a time line for grief, which the parent isn’t quite adhering to and they can sound judgemental.

Expect a testy response to comments such as ‘it’s for the best’. Few bereaved parents would ever agree with you on that and however sensible it seems to you, don’t suggest that another baby will make the parents feel better. Whether or not parents do go on to have another child, no one will ever replace the child who has died and parents will resent the suggestion that another child could ever do that.

If there are surviving siblings you can perhaps help by supporting them, again either emotionally or practically. Many siblings are sensitive to their parents’ grief and will try to protect them from their own sadness or anxieties. A grandparent, aunt or uncle, who has a good relationship with the child, could perhaps be a sounding board for them. Alternatively maybe you could help with homework or driving to school or other activities.

Holidays, birthdays and anniversaries will need especial care. Again do not make any assumptions about how parents may want to mark these days. Check out with the bereaved parents what they want to do on these dates and try to accommodate them as much as possible. They may want family and friends involved on a birthday or anniversary, but equally may want to spend it alone. Whether or not your physical presence is wanted, do not ignore the significant dates and do not ignore the child who has died. The first Christmas after Tom died, Tracy binned every card which didn’t acknowledge him in some way. It’s really important to parents to know that just as they have not forgotten their son or daughter, neither have you. And it’s not just the big events, which may be painful. Watching their son or daughter’s cousins or peers move from primary to secondary school, learn to drive or get married may well reinforce the absence of their own child. What may be a cause for celebration for you, may be bittersweet for bereaved parents.

Try to remember that there is no right or wrong way to grieve and do not judge or tell the bereaved parents how to do it. The most important thing to keep in mind is that no matter how much you may want to, you can’t fix this for them.

What you can do though is simply be there for them and continue to be there as the months go by.

Christine Young has been Associate Director of Grief Support for the Young in Oxfordshire since the beginning of 2011. Prior to that she was Head of Family Support and Bereavement at Helen and Douglas House, the pioneering children and young adult’s hospice.

Tracy Dowling is currently actively involved in peer-to-peer support at Helen and Douglas House and is also a volunteer with The Child Bereavement Charity in some of their training programmes in the capacity of a bereaved parent.

Parents and Bereavement: A Personal and Professional Exploration of Grief (OUP, 2012) brings together latest research and practice from the pioneering children and young adults’ hospice Helen and Douglas House, alongside the personal experience of a parent.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 15, 2012

Frank Close and Peter Higgs at the Edinburgh International Book Festival

The world famous Edinburgh International Festival has kicked off, beginning three weeks of the best the arts world has to offer. The Fringe Festival has countless alternative, weird, and wacky events happening all over the city, and the Edinburgh International Book Festival, is underway. Throughout the Book Festival we’ll be bringing you sneak peeks of our authors’ talks and backstage debriefs so that, even if you can’t make it to Edinburgh this year, you won’t miss out on all the action.

As you may know, our author Frank Close spoke with Peter Higgs on Monday. We put out a call for questions earlier on the blog, but didn’t anticipate the warm enthusiasm of the crowd over Twitter (follow Frank Close on Twitter at @CloseFrank). Thank you for all your updates, pictures, and encouraging comments. Here’s a quick recap:

View the story “Frank Close and Peter Higgs at #edbookfest” on Storify

And author Frank Close also sent us these two pictures:

Thank you to everyone for making this a great event!

Frank Close is a particle physicist, author, and speaker. He is Professor of Physics at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford. He is the author of several books, including The Infinity Puzzle, Neutrino, Nothing: A Very Short Introduction, Particle Physics: A Very Short Introduction, and Antimatter. Close was formerly vice president of the British Association for Advancement of Science, Head of the Theoretical Physics Division at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and Head of Communications and Public Education at CERN. Read more of what Frank Close has to say about neutrinos here and here. Read Frank’s reflections on the Nobel Prize nominations for the 4 July discovery.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Logo courtesy of Edinburgh International Book Festival

I been, I seen, I done

The forms in the title are substandard but ubiquitous in conversational English, and the universally understood reference to the genre called whodunit (it originated about seventy years ago) testifies to its partial victory. I have often heard the question about their origin and will try to answer it, though my information is scanty and to the best of my knowledge, a convincing theory of whodunit (the construction, not the genre) is lacking, which does not augur well for a detective story.

The English perfect (has) had a checkered career. First of all, it is used according to the rules partly different from those in the other Germanic languages. In no variety of English is it possible to say Dickens has died in 1870, while in every other Germanic language, in some contexts, this would be a legitimate sentence. Imagine the following exchange: “We have all read The Tale of Two Cities. But what was Dickens’s attitude toward the Paris Commune?” “He could not know anything about it. That event took place in 1871, while Dickens died in 1870!” To emphasize (or “foreground”) the date, rather than the fact of Dickens’s death, a speaker of German and of any Scandinavian language will use the perfect here. English prohibits this choice. The only concession to the “Eurozone” is the vacillation with the adverbial in the past. Depending on the circumstances, one can say: “It happened in the past” and “It has happened in the past.”

Three little kittens lost their mittens; And they began to cry, "Oh! mother dear, we really fear that we have lost our mittens!" "Lost your mittens! You naughty kittens! Then you shall have no pie." "Mee-ow, mee-ow, mee-ow." "No; you shall have no pie." "Mee-ow, mee-ow, mee-ow, mee-ow." The Three Little Kittens by R. N. Ballantyne, 1858. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Second, the present perfect seems to have increased its sphere of influence in British English since the colonization of the New World. The more usual American correspondences of British I have never seen it and she has just left the room are I never saw it and she just left the room. Even the anthologized picture of a boy weeping at the sight of the mischief he has done/did (it is supposed to illustrate a classic use of the present perfect as opposed to the simple past) — “Mother, I have broken a plate!” — leaves American speakers cold, for most of them would say in this situation: “Mother, I broke a plate!” Finally, our main theme: the affront of the omitted auxiliary in I been, seen, done. (I am almost tempted to apologize for the use of the term auxiliary ; everybody around me says help verb, which is probably fine.)The origin of grammatical phenomena is no easier to trace than the origin of words and idioms. So few things are certain in the history of I been/seen/done that it may be useful to mention them at once. I been and the rest are not imports from Black English (though some people think so) and they are not Americanisms (as most people believe). Another tempting hypothesis should also be dismissed. The auxiliary have is usually shortened to ’ve: we’ve met before, you should’ve come earlier, and so forth. This ’ve is meaningless even to such an enlightened segment of our population as college students, who write you should of come earlier. So why not leave it altogether? No, things don’t happen this way.

The omission of have produces strange sentences. What is do in I done? A participle or a new preterit? The same question may be asked about been and seen in I been and I seen. The past and the past participle of weak verbs always coincide: helped/helped, robbed/robbed, shredded/shredded. (This also holds for such irregular weak verbs as hear/heard/heard, feed/fed/fed, and keep/kept/kept.) Even a few strong verbs behave in a similar way: find/found/found, grind/ground/ground. (A point of information. Those who have forgotten the meaning of the terms weak and strong, as applied to verbs, are kindly requested to read the post for July 25, where this theme is developed in connection with the etymology of fart.) It could therefore be argued that the non-discrimination of principal parts by weak verbs influenced even such verbs as be (which is historically irregular), see (strong), and do (irregular). But then why do other strong verbs stand their ground so well? No one seems to say we eaten, I taken, and he spoken. Be, see, and do are the most common English verbs. However, the greatest frequency may even be a hindrance to change.

The only analog of I been/seen/done is I got for I’ve got. Here are a few examples from the 1978 article by the late Russian linguist G. S. Shchur. “What you got there, grandma?”; “There is no necessity of rushing it unless you want to, because we got to get more save up and everything arranged right”; “I got a right to know what she said, haven’t I?” (This is an especially interesting sentence because it shows that the speaker is aware of the unpronounced auxiliary.) However, I’ve got is an idiom, while I been/seen/done is not. A similar situation occurs in the following dialogue: “’What you got there,’ he asked Cameron, ‘run?’ — ‘We did have’ Cameron said drily.”

Been, seen, and done without have turn up in the novels and plays by Kingsley, Dickens, Joyce, Shaw, and others. “…they never got nothing but fourteen shilling, and I seen um both a-hanging in chains by Wisbeach river, with my own eyes” ; “Yer lie, I don’t owe yer nothing; I never seen yer” ; “Though I say it, I’m better than the best collector he ever done business with” ; “God knows we done all we could, as poor as we are.” Not all the speakers quoted above are low class characters. American authors (Sinclair Lewis, Steinbeck, and many others) recorded the same grammar: “What you been doing with yourself?” ; “I been checking up” ; “Any of you boys seen Curley?” Pre-nineteenth century examples exist, with a few (very few) going back to Middle English, but whatever the origin of I seen and the rest may be, its spread is recent and a continuous development from an early epoch to the present cannot be observed.

Judging by the not too copious data at our disposal, I been/seen/done arose in Irish English and the influx of Irish immigrants can account for their popularity in the United States. Perhaps the wide use of the have-less perfect in America had repercussions for British English (as happened to subjunctives like I insist you do it, without should, in Australia and New Zealand). But this suggestion does not carry too much weight, for no one says I done and I been on the American TV on a regular (or even irregular) basis, let alone write so in newspapers. Nor do northern English and Scots constructions of the type we done got this far, with done serving as an auxiliary, shed any light on the usage that interests us here. In the southern American states, “among the persons of assured social position,” one often hears “I’(ve) done told you this three times,” apparently, a relic of British usage brought there from the old country. (Southern I used to can ~ I used to could are also of Scottish provenance.)

As we can see (“as we seen”), the games with the perfect are many, but it is hard to detect a unifying thread. The Old Germanic languages did not have the perfect of the modern type or of the type known from Latin and Greek. This tense developed in the full light of history, and the development did not follow a straight line. Several auxiliaries have been tried, and sometimes the participle was considered sufficient for the form. Irish English seems to have been particularly radical in that respect. We probably owe the I been/seen/done construction to it. It was exported to America and became more widely used there than in the old country, but the virtual absence of pre-nineteenth attestation remains a mystery.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Julia Child at 100

One hundred years ago today, a legendary and influential American chef was born: Julia Child. With the introduction of fine food into every American home with books and television appearances, her unpretentious and enthusiastic attitude welcomed many to the art of cooking. We’re celebrating Julia Child’s life and work with an extract by Lynne Sampson from The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink.

Julia Child (1912–2004) became the most celebrated American cook and an important cultural figure in a public career spanning more than forty years. Her appealing blend of education and entertainment in the groundbreaking television series The French Chef introduced classical cooking techniques, exotic ingredients, and specialty equipment to mainstream America in the 1960s and 1970s. As a popular television personality, cookbook author, and mentor, Child elevated the status of cooking, shaped modern notions of food, and contributed to the development of the culinary profession throughout the second half of the twentieth century.

Child’s success as a media star was often attributed to her charming wit and uninhibited nature. The oldest daughter of a well-to-do family, Julia McWilliams was born in Pasadena, California, and graduated from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1934. A position with the Office of Strategic Services during World War II took her to posts in Asia, where she met her husband, Paul Child, who later became her collaborator. Her culinary career began at the age of thirty-seven, when the Childs moved to Paris and she enrolled in the Cordon Bleu cooking school.

Child’s first cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, was the product of her collaboration with two Frenchwomen, Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle. The three were partners in a Paris cooking school called L’Ecole des Trois Gourmandes, and its insignia decorated the blouse Child later wore on The French Chef. The book’s long route to publication is part of publishing lore. Ten years in the making and rejected by Houghton Mifflin, its contracted publisher, Mastering the Art of French Cooking was ultimately published by Knopf in 1961 to great acclaim. The best-selling cookbook was the first to popularize the principles of French cooking to a broad-based American audience. Thorough instructions and consideration of available ingredients set a new standard in cookbook writing, a model for the many cookbooks on ethnic cuisines that followed in the 1970s.

Child achieved her greatest influence through television. Although it was initially broadcast on a Boston public television station, The French Chef quickly became a national sensation, watched by men and women, noncooks and cooks, and won the first of its five Emmy Awards in 1965, a landmark event for educational television. Its popularity was due in part to Child’s sense of humor and the mistakes she handled with aplomb. Statuesque, with an unmistakable warbling voice, her manner and gaffes were frequently exaggerated and widely parodied. The French Chef, which aired from 1963 to 1973, created the celebrity called ‘‘Julia’’ and institutionalized the televised cooking show.

Her role as an educator was paramount to the show’s success and popularity. She approached haute cuisine with a sense of fun and fearlessness and emphasized simplicity over snobbery. Although she strayed from French cooking in successive series, she remained devoted to teaching home cooks the pleasures of preparing a meal—and to public television. She was also instrumental in the development of the American Institute of Wine and Food and the International Association of Culinary Professionals. She became a mentor to many chefs and was a role model for women in the field.

Soon after receiving the French Legion of Honor and just before her ninetieth birthday, Child left her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the famous kitchen that was the set for her last three cooking shows to return to southern California. In recognition of her role in American social history, the Smithsonian Institution acquired her original kitchen with nearly all of its contents, including the pegboard wall of pans and the Garland stove, and reinstalled it in the National Museum of American History in 2002.

Bibliography

Beck, Simone, Louisette Bertholle, and Julia Child. Mastering the Art of French Cooking. New York: Knopf, 1961.

Fitch, Noël Riley. Appetite for Life: The Biography of Julia Child. New York: Doubleday, 1997.

Greenspan, Dorie. Baking with Julia. New York: Morrow, 1996.

A sweeping reference work on food and drink in America, with fascinating entries on everything from the history of White Castle to the origin of the Bloody Mary, The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink provides more than a thousand concise, authoritative, and exuberant entries, beautifully illustrated with hundreds of historical photographs and sixteen pages of color plates. Editor Andrew F. Smith teaches culinary history and professional food writing at The New School University in Manhattan. He serves as a consultant to several food television productions (airing on the History Channel and the Food Network), and is the General Editor for the University of Illinois Press’ Food Series. He also edited the highly acclaimed 2-volume Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America and has written several books on food, including The Tomato in America, Pure Ketchup, and Popped Culture: A Social History of Popcorn in America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles about food and drink on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Edgar Allan Poe and terror at sea

The wife of Edgar Allan Poe, Virginia Clemm Poe, was born 15 August 1822. She lived a brief life, marrying Poe at 13 (he was 27) and dying of tuberculosis at 24. Poe worked hard to support their marriage and in 1838, three years into their marriage, Poe wrote his only novel: The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. While many of Poe’s works after his wife’s death were marked by the deaths of young women, terror clearly fascinated him from an early stage. Here Arthur Gordon Pym recounts a frightening incident at sea:

The wind, as I before said, blew freshly from the southwest. The night was very clear and cold. Augustus had taken the helm, and I stationed myself by the mast, on we deck of the cuddy. We flew along at a great rate — neither of us having said a word since casting loose from the wharf. I now asked my companion what course he intended to steer, and what time he thought it probable we should get back. He whistled for a few minutes, and then said crustily, ‘I am going to sea — you may go home if you think proper.’ Turning my eyes upon him, I perceived at once that, in spite of his assumed nonchalance, he was greatly agitated. I could see him distinctly by the light of the moon — his face was paler than any marble, and his hand shook so excessively that he could scarcely retain hold of the tiller. I found that something had gone wrong, and became seriously alarmed. At this period I knew little about the management of a boat, and was now depending entirely upon the nautical skill of my friend. The wind, too, had suddenly increased as we were fast getting out of the lee of the land; still I was ashamed to betray any trepidation, and for almost half an hour maintained a resolute silence. I could stand it no longer, however, and spoke to Augustus about the propriety of turning back. As before, it was nearly a minute before he made answer, or took any notice of my suggestion. ‘By and by,’ said he at length — ‘time enough — home by and by.’ I had expected such a reply, but there was something in the tone of these words which filled me with an indescribable feeling of dread. I again looked at the speaker attentively. His lips were perfectly livid, and his knees shook so violently together that he seemed scarcely able to stand. ‘For God’s sake, Augustus,’ I screamed, now heartily frightened, ‘what ails you? — what is the matter? — what are you going to do?’ ‘Matter!’ he stammered, in the greatest apparent surprise, letting go the tiller at the same moment, and falling fornrard into the bottom of the boat — ‘matter! — why, nothing is the-matter — going home — d-d-don’t you see?’ The whole truth now flashed upon me. I flew to him and raised him up. He was drunk — beastly drunk — he could no longer either stand, speak, or see. His eyes were perfectly glazed; and as I let him go in the extremity of my despair, he rolled like a mere log into the bilge-water from which I had lifted him. It was evident that, during the evening, he had drunk far more than I suspected, and that his conduct in bed had been the result of a highly-concentrated state of intoxication; a state which, like madness, frequently enables the victim to imitate the outward demeanor of one in perfect possession of his senses. The coolness of the night air, however, had had its usual effect, the mental energy began to yield before its influence, and the confused perception which he no doubt then had of his perilous situation had assisted in hastening the catastrophe. He was now thoroughly insensible, and there was no probability that he would be otherwise for many hours.

It is hardly possible to conceive the extremity of my terror. The fumes of the wine lately taken had evaporated, leaving me doubly timid and irresolute. I knew that I was altogether incapable of managing the boat, and that a fierce wind and strong ebb tide were hurrying us to destruction. A storm was evidently gathering behind us; we had neither compass nor provisions; and it was clear that, if we held our present course, we should be out of sight of land before daybreak. These thoughts, with a crowd of others equally fearful, flashed through my mind with a bewildering rapidity, and for some moments paralyzed me beyond the possibility of making any exertion. The boat was going through the water at a terrible rate — full before the wind — no reef in either jib or mainsail — running her bows completely under the foam. It was a thousand wonders she did not broach to — Augustus having let go the tiller, as I said before, and I being too much agitated to think of taking it myself. By good luck, however, she kept steady, and gradually I recovered some degree of presence of mind. Still the wind was increasing fearfully; and, whenever we rose from a plunge forward, the sea behind fell combing over our counter, and deluged us with water. I was so utterly benumbed, too, in every limb, as to be nearly unconscious of sensation. At length I summoned up the resolution of despair and, rushing to the mainsail, let it go by the run. As might have been expected, it flew over the bows, and, getting drenched with water, carried away the mast short off by the board. This latter accident alone saved me from instant destruction. Under the jib only,* I now boomed along before the wind, shipping heavy seas occasionally, but I relieved from the terror of immediate death. I took the helm, and breathed with greater freedom, as I found that there yet remained to us a chance of ultimate escape. Augustus still lay senseless in the bottom of the boat; and, as there was imminent danger of his drowning (the water being nearly a foot deep just where he fell). I contrived to raise him partially up, and keep him in a sitting position, by passing a rope round his waist, and lashing it to a ringbolt in the deck of the cuddy. Having thus arranged everything as well as I could in my chilled and agitated condition, I recommended myself to God, and made up my mind to bear whatever might happen with all the fortitude in my power.

Hardly had I come to this resolution, when suddenly a loud and long scream or yell. as if from the throats of a thousand demons, seemed to pervade the whole atmosphere around and above the boat. Never while I live shall I forget the intense agony of terror I experienced at that moment. My hair stood erect on my head — I felt the blood congealing in my veins — my heart ceased utterly to beat, and, without having once raised my eyes to learn the source of my alarm, I tumbled headlong and insensible upon the body of my fallen companion.

Edgar Allan Poe’s only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket is a pivotal work in which Poe calls attention to the act of writing and to the problem of representing the truth. It is an archetypal American story of escape from domesticity tracing a young man’s rite of passage through a series of terrible brushes with death during a fateful sea voyage. Included are eight related tales which further illuminate Pym by their treatment of persistent themes — fantastic voyages, gigantic whirlpools, and premature burials — as well as its relationship to Poe’s art and life.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

15 August 1040: Macbeth kills King Duncan I of Scotland

Susan Sontag wrote that having a photograph of Shakespeare would be like having a piece of the True Cross. We don’t have a photograph, of course, and even the portraits that we do have are unreliable, but in his plays he left snapshots of a different kind. Since we know with some precision — thanks to the diligence of many scholars — the sources he relied upon in writing the plays, we are able to trace his creativity by a simple contrast. By paying attention to what he retains from his sources, and what he changes, we may produce — like developing a photograph from its negative — a portrait of Shakespeare at work.

The principal source for the plot of Macbeth is the massive Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, compiled by Raphael Holinshed and first published in 1577. Holinshed narrates how Macbeth was “sore troubled” by King Duncan’s nomination of his son Malcolm as heir to the throne, and “he slue the king at Enuerns, or (as some say) at Botgosuane, in the sixt year of his reigne,” on 15 August 1040. Macbeth is, according to Holinshed, not immediately a tyrant: “governing the realme for the space of ten yeares in equall justice,” he becomes increasingly paranoid and murderous, and eventually “He was slaine in the yeere of the incarnation 1057” by Malcolm, who assumes the throne.

Macbeth and Banquo encountering the witches. Holinshed Chronicles, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

No dates are given in Shakespeare’s play, but the dramatic version of events is far more rushed than the seventeen years narrated in the Chronicles. The play opens in civil war and in a flurry of action: messengers sent back and forth, the battle, and the arrival of King Duncan as a guest at Macbeth’s castle. That night, Macbeth kills Duncan, and the body is discovered in the morning; Macbeth becomes king, murders Banquo, holds a feast, and sees a ghost. Malcolm flees to England and returns to depose Macbeth.This compression of seventeen years into what feels like only weeks isn’t incidental to the play. The central character is obsessed with the rushing passage of time. The witches promise Macbeth that he shall be king, but they also show him a vision of the eight kings that will follow him, all of whom are the heirs of Banquo. “What!” he declares, “will the line stretch out to th’crack of doom?” He is horrified that Banquo’s family will rule until, it seems, the end of time, while his kingship is only temporary. Later, when he hears of the death of his wife, he says:

She should have died hereafter,

There would have been time for such a word.—

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time.

He longs for eternity, for the endless deferral of the present, but he is like all of us trapped inside too-short human time.

15 August reveals much about this play and its author. Shakespeare’s is an art of intensification. He condenses years into moments, bitter rivals into lovers, and in particular the tragedies hinge upon the shortness of time. In both Romeo and Juliet and King Lear, messages are delivered only moments too late and cause deaths. “The weight of this sad time we must obey” says Edgar at the end of King Lear, and in Othello — another play whose timespan Shakespeare has drastically reduced from his source — the hero echoes this line: “We must obey the time.”

Battle of Dunsinane by John Martin. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Shakespeare disobeyed the time given by his source. He denies Macbeth the seventeen years for which the historical king ruled. He is, after all, writing tragedy, not faithful history, but August 15 might have taught him how to do this. According to other chronicle accounts of this period — although not Holinshed — the date when Macbeth was killed in 1057 was also 15 August. The day of his accession to the throne was also the day of his death, and the historical original, like his dramatic counterpart, simply ran out of time.

Daniel Swift is Senior Lecturer for English at the New College of the Humanities. His first book Bomber County: The Poetry of a Lost Pilot’s War was long-listed for the Guardian First Book Award and the Samuel Johnson Prize. His latest work, Shakespeare’s Common Prayers: The Book of Common Prayer and the Elizabethan Age is scheduled for publication in the autumn.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 14, 2012

10 questions for Suzzy Roche

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selection while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 21 August, Suzzy Roche leads a discussion on The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton, and will perform it at the end.

Suzzy Roche. Photo by Irene Young.

What was your inspiration for this book?I had written a short story called “Love” and that turned out to be an outline for my book Wayward Saints (although I didn’t know it at the time). I never thought I’d be able to write a novel. It was a miracle, a blessing, and a mysterious event in my life.

Where do you do your best writing?

In my living room or anywhere I can be alone.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

Because I’ve been a songwriter and performer most of my life, I think writing just became a part of my daily routine. When I was young, I wrote stories and poems, having no idea I would or could ever write a book.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

Charlotte Brontë.

What is your secret talent?

Problem-solving and dreaming while awake.

What is your favorite book?

Too hard! Currently House of Mirth by Edith Wharton because that’s the one I’ve been studying for the Word for Word book discussion.

Who reads your first draft?

My friend and superb author Meg Wolitzer has been a wonderful reader for me, and mostly because we’ve exchanged work. But now I have a writing group and I have a special writing buddy, Harriet Goldman, who is also working on a novel. I think it’s enormously helpful to get a glimpse into other writer’s processes. Sharing work requires trust, though, and it’s not possible or even a good idea to trust everyone.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

No, just like I never listen to my CDs after they are done. But I would like to re-write my book and re-record all my CDs.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

Computer. My handwriting is egregious.

What book are you currently reading? (Old school or e-Reader?)

I just read Christopher Isherwood’s My Guru and His Disciple. A very pure book.

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing?

The word seemed. I’ve come to detest the word in my own writing. I noticed that Edith Wharton used the word “disinterestedness” an enormous amount. I’ve never heard that word before.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

I wish I could work one-on-one with children who are shy and lonesome.

Along with her sisters, Suzzy Roche is a founding member of the beloved singing group the Roches, whose debut recording was named Album of the Year by the New York Times in 1979. She has appeared on Saturday Night Live, the Late Show with David Letterman, and the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Roche lives in New York City, and Wayward Saints is her first novel.

Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about The House of Mirth on the

The great silence: Afghanistan in the presidential campaigns

From time to time, political commentators bemoan the fact that we don’t debate the war in Afghanistan in our political campaigns. Back in 2010, Tom Brokaw complained that in the heated mid-term elections neither party showed any interest in arguing about the best course to pursue in the ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. He chalked this up to the fact that most Americans could opt out of military service, so the wars touched few families. In a recent column, Rajiv Chandrasekaran, who has written provocative books about both wars, laments the silence on Afghanistan from both the Obama and Romney campaigns. With almost 80,000 troops in Afghanistan and a cost to taxpayers this year of almost $100 billion, he insists, Americans need to weigh the implications of our ongoing commitment to the Afghan government. He finds the candidates’ vague words on the pace of the drawdown of American troops disturbing. Similarly, Jackson Diehl points to the deaths of 46 US and coalition troops in July as an ominous sign of Taliban revival. Yet, despite the fact that important decisions are pending on the future role of the United States in the conflict, Diehl objects that “this may be the first presidential campaign in US history in which an ongoing war fails to produce a significant debate.”

US Marines listen to a briefing before beginning a security patrol along the Helmand River near Combat Outpost Ouellette, Helmand province, Afganistan, March 3, 2011. The Marines are with 1st Platoon, Lima Company, Battalion Landing Team, 3rd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment, Regimental Combat Team 8, 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit. (US Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Jesse J. Johnson/Released). Source: Department of Defense.

Odd though it may be in historical terms, there are good political reasons for the campaigns to eschew a discussion of Afghanistan. The war represents a no-win issue. Neither candidate stands to gain votes by dwelling on his position. (And, for that matter, it isn’t clear what Romney’s stance is, as I’ve noted.) Indeed, to speak about war could easily cost Obama or Romney votes.The president has a two-fold campaign strategy that calls for appealing to centrist voters while mobilizing the Democratic base. That base has been conspicuously unenthusiastic about the Afghanistan conflict from the moment Obama assumed office. His conduct of antiterrorist operations, especially drone attacks, has provoked criticism from the political left. Liberals want to see the United States exit Afghanistan as quickly as possible, an important element in reducing defense outlays. Although other voters don’t share the left’s antipathy for the conflict, they also show no enthusiasm for it. Silence is the prudent political course.

For Romney, the political math isn’t significantly different. He, too, needs to stir his party base while winning independent voters. Polls reveal that even Republicans have lost their taste for the war. Certainly this isn’t an issue on which to mobilize die-hard conservatives, an ongoing problem for his campaign. Romney has made occasional noises about listening to the generals in the field before withdrawing combat troops. That may sound like a “tough” commander in chief, but the two-thirds of independent voters who disapprove of the war won’t be impressed. Here, too, saying nothing is the prudent political course.

Possibly during the presidential debates this fall, one of which is reserved for foreign policy, the candidates will be pressed on their Afghanistan policies. If so, alas, I would expect nothing more than a reiteration of the general statements they’ve made to date. Obama will praise the progress made on the ground and speak of “transitioning out” of a combat role by 2014, while Romney will insist that Obama made a mistake by revealing to the Taliban the American withdrawal schedule when he first decided on a surge. None of this will shed much light on the future.

But politics aside, there is another reason why we’re not debating Afghanistan in this campaign. The actual policy space remaining for the United States, whoever is in the Oval Office come Inauguration Day 2013, is very limited. American troops will be coming home over the next two years. Whether the pace is the one Obama prefers or the slightly slower rate that some field commanders might like to see, the difference to the long-term future of Afghanistan will be insignificant. The Afghan Army and police may not be able to stand on their own — there are serious doubts — but either way American troops won’t stay or return.

Likewise, the president has committed the United States to a long-term security partnership with the Kabul government that would cost the United States $4 billion per year for a decade. That is a large sum of money, in an era when Congress will be looking to cut expenditures. But it is a lot less than the war itself has been costing. Moreover, neither party would want to be saddled with responsibility for a repetition of the collapse of the Saigon government in 1975, which could be a political liability down the road. The money would serve as a kind of political insurance policy.

No political upside, very few policy options — it isn’t hard to see why the candidates continue to shun Afghanistan in their campaigns. The American people want to see the war ended, but don’t want a collapse of the Kabul government to follow. Although a “Who lost Afghanistan?” debate wouldn’t have much political traction, neither party would want the blame. The war will grind on, drawing the occasional headline, the cost borne by troops and their families, in political silence.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers