Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1028

August 28, 2012

The battle over homework

For this back-to-school season, I would like to offer some advice about one of the most frequent problems presented to me in over 30 years of clinical practice: battles over homework. I have half-jokingly told many parents that if the schools of New York State no longer required homework, our children’s education would suffer, but as a child psychologist I would be out of business.

Many parents accept this conflict with their children as an unavoidable consequence of responsible parenting. These battles, however, rarely result in improved learning or performance in school. More often than not, battles over homework lead to vicious cycles of nagging by parents, and avoidance or refusal by children. This cycle doesn’t improve a child’s school performance and certainly doesn’t make progress toward what should be our ultimate goal. We want to help children enjoy learning, and develop age-appropriate discipline and independence with respect to their schoolwork.

Remember that the solution to the homework problem always begins with an accurate diagnosis and a recognition of the demands placed on your child. Parents should never assume that a child who resists doing homework is “lazy.”

Every child whose parents or teachers report ongoing resistance to completing schoolwork or homework, whose performance in school is below expectations based on his parents’ or teachers’ intuitive assessment of his intellectual potential, and who complains that he “hates school” or “hates reading” over an extended period of time, should be evaluated for the presence of an attention or learning disorder.

These children are not lazy. Your child may be anxious, frustrated, discouraged, distracted or angry, but this is not laziness. I frequently explain to parents that, as a psychologist, the word lazy is not in my dictionary. Lazy, at best, is a description, not an explanation.

For children with learning difficulties, doing their homework is like running with a sprained ankle. It is possible, although painful, and he will look for ways to avoid or postpone this painful and discouraging task.

A Homework Plan

Homework, like any constructive activity, involves moments of frustration, discouragement, and anxiety. If you begin with some appreciation of your child’s frustration and discouragement, you will be better able to put in place a structure that helps him learn to work through his frustration, and to develop increments of frustration tolerance and self-discipline.

Homework, like any constructive activity, involves moments of frustration, discouragement, and anxiety. If you begin with some appreciation of your child’s frustration and discouragement, you will be better able to put in place a structure that helps him learn to work through his frustration, and to develop increments of frustration tolerance and self-discipline.

Set aside a specified and limited time for homework. Establish, early in the evening, a homework hour.

For most children, immediately after school is not the best time for homework. This is a time for sports, music, drama, and free play.

During the homework hour, all electronics are turned off for the entire family.

Work is done in a communal place, such as at the kitchen or dining room table. Contrary to older conventional wisdom, most elementary school children are able to work more much effectively in a common area, with an adult and even other children present, than in the “quiet” of their rooms.

Parents may do their own “homework” during this time, but they are present and continually available to help, to offer encouragement, and to answer children’s questions. Your goal is to create, to the extent possible, a library atmosphere in your home for a specified and limited period of time. Ideally, parents shouldn’t make or receive telephone calls during this hour. When homework is done, there is time for play.

Begin with a reasonable amount of time set aside for homework. If your child is unable to work for 20 minutes, begin with 10 minutes. Then try 15 minutes the next week. Acknowledge every increment of effort, however small.

Be positive and give frequent encouragement. Make note of every improvement, not every mistake.

Be generous with your praise. Praise their effort, not their innate ability.

Anticipate setbacks. After a difficult day, reset for the following day.

Give them time. A child’s difficulty completing homework begins as a problem of frustration and discouragement, but it is then complicated by defiant attitudes and feelings of unfairness. A homework plan will begin to reduce these defiant attitudes, but this will not happen overnight.

Most families have found these suggestions helpful, especially for elementary school children. Establishing a homework hour allows parents to move away from a language of threats (“If you don’t… you won’t be able to…”) to a language of opportunities (“As soon as” you have finished… we’ll have a chance to…”).

Of course, for many hurried families, there are complications and potential glitches in implementing any homework plan. It is often difficult, with children’s many activities, to find a consistent time for homework. Some flexibility and amendments may be required. But we shouldn’t use the complications of scheduling or other competing demands as an excuse or a reason not to establish the structure of a reasonable homework routine.

Kenneth Barish is the author of Pride and Joy: A Guide to Understanding Your Child’s Emotions and Solving Family Problems and Clinical Associate Professor of Psychology at Weill Medical College, Cornell University. He is also on the faculty of the Westchester Center for the Study of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy and the William Alanson White Institute Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy Training Program. Read his previous blog posts “Helping children learn to accept defeat gracefully” and “Emotion, interest, and motivation in children.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

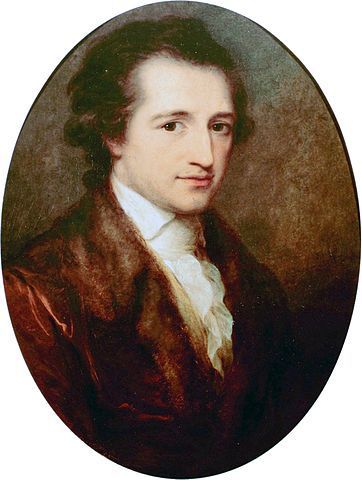

Young Goethe

Portrait of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe by Angelica Kauffman, 1787. Goethe-Nationalmuseum. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Goethe was born almost dead on 28 August 1749. He opened his eyes, he lived, only when the midwife rubbed his heart with wine. Perhaps that uncertain start awoke a determination in him to stay alive as long as possible. There’s a wry saying in German: Alle Menschen müssen sterben — ich auch, vielleicht (All men must die — me too, perhaps). And that’s how Goethe lived, cannily keeping out of the way of death, cramming as much life as he could into the time allowed.Goethe was seriously ill several times in his life and was besides disposed to depression and hypochondria. In self-defence against too many demands from too many people, he fled or withdrew. He ran from love-affairs that he felt might overwhelm him. He had a sure sense of what he must do to survive — and to survive as poet, for in following that vocation he was most himself. He had a superstitious horror of anything that touched on sickness and death — avoided funerals, even his wife’s; disliked churchyards; abhorred crucifixes; and indeed, being known among his contemporaries as “the old heathen,” he detested all the morbid and otherworldly tendencies in Christianity. He was what the Germans call diesseitig (on this side, in the here and now), not jenseitig (not over there, in the beyond). He was hard on weakness, chaos, self-destructiveness in other people. He came through his own Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress), and had no sympathy for those who didn’t come through or never grew out of theirs. In his eightieth year, hearing of the death in Rome of his hapless son August, the only one of his five children to survive much beyond birth, he said: “Over the graves then, onwards!”

Ruthlessly in favour of life, Goethe was the creator, in Werther, of the very type of person who is drawn towards and finally into death. He wrote the novel fast, in four weeks, to be rid of that dangerous possibility or temptation in himself — to be free, as he said, for the further enjoyment of life. Many of his readers didn’t feel so released; in some it fatally encouraged their own inclination to let go. And of course, there was no finality in Goethe’s remedy even for himself. Poets are incapable of “closure”; they hate the very idea of it. Again and again he found himself back in Werther’s predicament, most scandalously in 1821, in love with a seventeen-year-old. In 1824 a fiftieth-anniversary edition of Werther was published, for which Goethe, then seventy-five, supplied a poem addressing the ‘much lamented shade’ in whom he still knew himself. Goethe never did get rid of Werther. Wherever he went, throughout his life, that suicidal character shadowed him.

Like many poets — Yeats, Graves, Apollinaire come to mind — Goethe opposed death mainly by love. It is an old — the old — combat: Eros versus Thanatos, Love versus Death. Goethe was almost always in love. His rebirths, his extraordinary shifts into new poetry, all have a new love at their heart: the Sturm und Drang lyrics, the Roman Elegies, the West-Eastern Divan, the “Trilogy of Passion” — all very different, all written by the same poet, in new circumstances, in a new mode, in love again. Faust, the play he worked at, on and off, for sixty years, the very concept of it shifting as he grew, became, in Part II, a glorious celebration of Eros, the life-giver. Faust is saved, not for any good in him (he is perhaps the least likeable ‘hero’ in world literature), but through the redemptive love of Gretchen, whom he seduced and abandoned.

In Werther Goethe was more consequentially tragic than he ever would be again. A chief component of our sense of tragedy is waste. Werther’s death is a terrible waste. Such a talented young man, so in love with life, so finely alive to the beauty and changing character of the natural world, so able in his letters to bring home that beauty to others. But in circumstances that thwart and oppress him, in an increasingly partial view of his situation, he converts the chief good in him, his passion, his capacity for love, into its deadly opposite. He sides with death against himself. There is enough against him and his beloved Lotte anyway. In that society the likely fate of any man or woman of sensibility is what Elizabeth Bowen calls “the death of the heart.” Werther kills himself. And, as the narrator says, “they feared for Lotte’s life.”

Werther requires that we answer back; that we see what is going to waste in Werther and in Lotte, and that we part company from him when he cannot any longer defend himself and goes his way into death. The injunction of the novel is Goethe’s own continual injunction to himself: resist, fight back, make a life you can call your own. Side with Eros against the many and various ways of Death!

David Constantine, born 1944 in Salford, Lancs, was for thirty years a university teacher of German language and literature. He has published several volumes of poetry (most recently Nine Fathom Deep); also a novel, Davies (1985), and three collections of short stories: Back at the Spike (1994), Under the Dam (2005) and The Shieling (2009). He is an editor and translator of Hölderlin, Goethe, Kleist and Brecht. His translation of Goethe’s Faust, Part I was published by Penguin in 2005; Part II in 2009. OUP published his translation of the The Sorrows of Young Werther in 2012. He is the winner of 2010 BBC National Short Story Award. Another volume of stories is due out in September. With his wife Helen he edits Modern Poetry in Translation.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The LPO, Minis, and an Olympic afterglow

This is my last blog on the music and TV broadcasts for the 2012 Olympic games — I promise. But I just saw a new video ad that I must share.

In my last blog post, I noted the remarkable feat of the London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO), who under the baton of Philip Sheppard, recorded the national anthems of all 205 participating nations in the Olympic games in a little under 52 hours of studio time. These recordings, of course, were to be used during the 305 medals ceremonies at the games. According to Sheppard, who wrote new arrangements for each of the anthems and then conducted the groups for the recordings, the orchestra players had about 12 minutes to read and record each anthem. Not all 205 anthems were played, but all were recorded — just in case. It turns out that only 54 anthems were actually played for medals ceremonies, that is, for the countries that won the gold medal for the event. Of the 54 anthems, 19 of these were played only once.

Sheppard explained that each of the 205 recordings had to have a unique arrangement created for the Olympics for two reasons: “one is artistic – to create a faithful (version) but redesigned with a fresh spin,” and the other is legal — “you don’t want to replicate a previous arrangement.”

The anthems will also be used for the upcoming Paralympics, also held in London.

But the London Philharmonic isn’t finished with its Olympic media exposure just yet. A video ad for the British car Mini Cooper was unveiled recently that had members of the “horn” section of the orchestra step into a string of red, white, and blue 2012 Minis. This time, under the direction of conductor Gareth Newman, the players performed a rendition of “God Save the Queen” using nothing but the car horns of the Minis to play the tune, sometimes with harmony.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The ad is a brilliant marketing ploy to keep the orchestra in the media limelight. With dwindling audiences and sagging revenues for orchestras around the world, the LPO has shown it can adapt to 21st century British pop culture, and in a comical, clever way. The orchestra took a back seat to Brit pop groups in the Olympic opening and closing ceremonies, but the Mini ad puts the orchestra (or at least the LPO “horn” section) at the forefront of a TV audience’s attention.

Ron Rodman is Dye Family Professor of Music at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. He is the author of Tuning In: American Television Music, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. Read his previous blog posts “Music and the Olympic Opening Ceremony: Pageantry and Pastiche,” “Music and the Olympics: A Tale of Two Networks,” and “A Spice Girl Symphony: The Olympic Closing Ceremony.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 27, 2012

Josquin des Prez

No figure in Western music poses a greater challenge to the writing of history than Josquin des Prez (ca. 1450–1521). That’s because there is no composer of comparative fame — musicians regularly speak Josquin’s name in the same breath as Bach, Beethoven, or Brahms — about whom so very little is known. By “very little” I’m not referring to second-order stuff, like how often he composed, what his favorite dessert was, or whom he took to bed. No, with this composer we face much more basic questions: What pieces did he write? Where was he when? Who was Josquin?

The problem is one of documentation. Most of the biographical information we have about late-medieval musicians comes from pay records, account registers, and official church documents, few of which have survived. As a result, piecing together a 15th-century composer’s biography often means connecting a series of all too disparate dots, with the help of inference, conjecture, and — let’s face it — wild guesses. In the case of Josquin this picture is unusually cloudy, not least because his name was relatively common in French-speaking lands. At 500 years distance, it’s all too easy to confuse Josquin des Prez with other contemporary Josquins, among them several musicians.

By around 1500, “our” Josquin was the most famous composer in Europe and very much in the right place at the right time. Thanks to the novel technology of printing, polyphonic music was about to reach a wider audience than ever before. One might reasonably surmise that this circumstance would solve our problem. After all, we know his music traveled more widely than any composer who’d ever lived, and we still have lots of it. We know it endured longer than ever before (his works continued to be performed regularly until at least the early 17th century). And we know he was idolized by 16th-century musicians and music-lovers; this period witnessed a proliferation of anecdotes as colorful as they are rich in biographical detail. But if it’s the historical Josquin we’re after, this documentary treasure trove is deceptive. Ought we really to believe a piece is by Josquin if it first turns up in a publication printed decades after his death by someone who stood to gain financially by unleashing a new “Josquin” work to the public? And can we trust a story about Josquin’s biography — say, a tall tale about how difficult he was to work with — written by someone who couldn’t possibly have known him? Documents of this kind are invaluable as testimony to Josquin’s posthumous reception, but offer little help in accessing the historical figure.

There are several possible ways out of this conundrum. We could play one of scholarship’s dirtiest tricks: tell a fleshed-out story that conveniently neglects the tenuous assumptions that underpin it. Or we could pronounce, in a postmodern vein as anti-intellectual as it is passé, that authorship no longer matters (“who cares who wrote it?”), or that seeking information about the historical Josquin amounts to “fetishizing” him. Josquin scholarship has at times fallen into these traps, but we need not do so. We have a third option: to treat gaps in our knowledge as an opportunity to confront methodological, historiographical, and epistemological problems with uncommon candor. This means acknowledging with unprecedented openness the uncertainties that swirl around this composer while also bringing to bear the full force of our intellectual capacities in order to negotiate the line between what we know and what we don’t.

Today marks the 491st anniversary of Josquin’s death. We might take advantage of this moment to commune with the bedrock of material we do have — above all, the music that made him famous (chiefly Latin-texted sacred pieces and French chansons). Even if we confine ourselves to the works we can be all but certain he composed, Josquin continues to astonish. His compositions combine unprecedented technical wizardry with an eloquent and often deeply moving melodic style. For such eloquence one need look no further than Pater noster–Ave Maria, a six-voice setting that Josquin specified in his will should be sung outside his house for all church processions in perpetuity. Those processions have long since been forgotten. Josquin’s house no longer stands. But we can still experience the way he lingers over the last line (“Ora pro nobis peccatoribus / ut cum electis te videamus”), obsessively repeating a falling-third gesture — a Josquin trademark — with a quiet intensity no listener is likely to forget.

Jesse Rodin is Assistant Professor of Music at Stanford University. He has published widely on music of the Renaissance and his latest book is Josquin’s Rome: Hearing and Composing in the Sistine Chapel. In 2010 Rodin received the Noah Greenberg Award in recognition of his work combining scholarship and performance. Rodin directs the Josquin Research Project, a digital humanities team developing tools for accessing and analyzing Renaissance music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: a facsimile copy of the famous woodcut from Petrus Opmeer’s Opvs chronographicvm orbis vniversi a mvndi exordio vsqve ad annvm M.DC.XI. (Antwerp, 1611). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

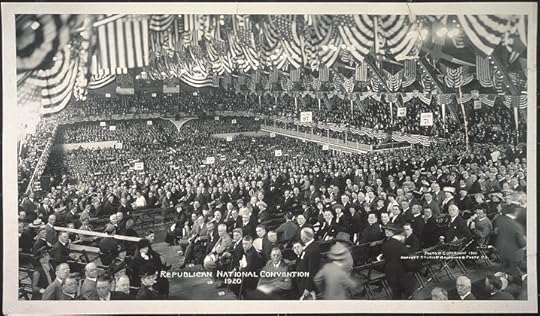

The Decline and Fall of the American Political Convention

Will you be tuning in to watch this year’s Republican and Democratic national conventions in the hope of seeing something of historic significance? The managers of both conventions are working hard to make sure that you don’t get your wish. From their standpoint, the best convention is a precooked and tightly controlled event that passes placidly and without controversy into the annals of national forgetfulness. They would vastly prefer a convention that resembles a four-day infomercial to one that includes anything unexpected or consequential.

It was not ever thus. For more than a century after the first convention of the modern Democratic Party in 1832 and of the Republican Party in 1856, the national conventions were often occasions of great drama, marked by titanic struggles among rival factions and fevered excitement around the selection of a presidential nominee and the construction of a national platform. Highlights and lowlights of that era included the 1844 Democratic convention which named Tennessee governor James Polk as the first “dark horse” presidential nominee, the 1912 Republican convention that led to the “bolt” of Theodore Roosevelt’s progressive faction, and the 1924 Democratic convention which required a record 103 ballots over nine days to nominate John W. Davis of West Virginia.

There was no necessary connection between controversy at a convention and the eventual electoral outcome. Warren G. Harding won the 1920 presidential election despite having been selected as his party’s nominee by bosses meeting in the original “smoke-filled room” at the Chicago GOP convention. Harry S. Truman carried the 1948 election despite the walkout of segregationist Southerners from the Democratic convention in Philadelphia to form the Dixiecrat Party.

Republican National Convention, 1920. Photo by Moffett Studio and Kaufmann & Fabry Co. Source: Library of Congress.

Political conventions once were raucous tribal gatherings. The 1860 GOP convention in Chicago was so noisy, according to one observer, that “A thousand steam whistles, ten acres of hotel gongs, a tribe of Comanches, headed by a choice vanguard from pandemonium, might have mingled unnoticed.” The chaos and bombast began to be reined in after television became a significant factor at the conventions. The 1940 Republican convention was the first to be televised, but television had little immediate effect on the old-time rituals since only a small percentage of Americans owned a TV set until the 1950s. The 1952 Republican convention was the last to feature fistfights on the floor, as conservatives supporting Robert Taft clashed with moderates supporting Dwight Eisenhower. But soon thereafter, both party officials and TV executives decided that the traditional divided, brawling convention was bad for business. Starting in 1956, conventions began to become more staid and scripted affairs.

It took a while, of course, for the parties to learn how to prosper in the new era of wide public attention to televised national conventions. The 1964 Republican convention was a political relations disaster. Conservatives had finally succeeded in nominating one of their own — Barry Goldwater — over the opposition of the moderates and were in no mood for conciliation. Delegates harassed the “liberal” media and howled down New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, the hated leader of the progressive faction, when he attempted to address the convention. They roared when Goldwater praised “extremism in the defense of liberty.” Millions of Americans watching the spectacle were appalled, and voted Democratic by landslide margins. Four years later, the Democrats faced their own convention debacle as Chicago police beat and gassed protestors outside the convention hall, sparking angry divisions among the delegates for all the nation to see. The spectacle likely contributed to Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey’s narrow loss to Richard Nixon in the 1968 elections.

The 1968 protests in Chicago were aimed not only at the Vietnam war but at the undemocratic system by which presidential nominees were chosen. Humphrey secured the Democratic nomination even though he had not entered a single contested primary election. Starting in 1972, most delegates to the Democratic national convention were bound to candidates who had won their states’ primary elections or caucuses; Republicans followed suit in 1976. The result of this reform was that the presidential nominees of both parties became largely determined long before the conventions. The last serious contest over a party’s presidential nomination came at the 1976 GOP gathering in Kansas City, when incumbent president Gerald Ford narrowly defeated his conservative challenger Ronald Reagan. Four years later, Democratic incumbent president Jimmy Carter fended off a similar though less formidable challenge from Ted Kennedy. Both Ford and Carter lost their reelection bids, which reinforced the party professionals’ belief that divided conventions must be avoided all costs. There hasn’t been any real division or even uncertainty about the presidential nomination at a convention for the past thirty-two years.

Illinois delegates at the Democratic National Convention of 1968, react to Senator Ribicoff's nominating speech in which he criticized the tactics of the Chicago police against anti-Vietnam war protesters. Photo by Warren K. Leffler. Source: Library of Congress.

Party conventions now seek to create hoopla around their nominees and stir up the party faithful while avoiding anything that could damage their electoral chances in the fall. They don’t always succeed. For example, the 2004 Democratic convention’s showcasing of John Kerry’s military service in Vietnam backfired as Republicans made it the basis of their “Swift Boat” attacks on Kerry’s war record. The managers of Republican conventions have to walk a fine line in trying to excite their conservative base without alienating moderates. Their most notable failure came at the 1992 GOP convention, when the party establishment behind President George H. W. Bush attempted to appease the restive right wing of the party by giving Patrick Buchanan a prominent speaking opportunity. Buchanan called for holy war against liberals, feminists, and homosexuals, thrilling social conservatives but giving the public a too-revealing glimpse of the forces of intolerance brewing inside the GOP.

Television, electoral predetermination, and the massive amounts of money riding on elections have combined to make conventions into tame, predictable, and rather boring occasions. Like most propaganda spectacles, they are hollow and unconvincing. I’m skeptical that many viewers will really believe that the GOP is a party with large numbers of minority supporters (as television coverage inside the convention hall might lead one to believe) or that the Democrats are enjoying any real resurgence in the South (despite the rhetoric of Charlotte’s boosters). I suspect that most people who follow the conventions closely are either die-hard partisans or the political equivalent of those NASCAR spectators who want to see a crash, and I doubt that any of them will come away satisfied.

To me, the only really important aspect of conventions nowadays is the behind-the-scenes negotiations that go into determining the party platforms. Granted that a presidential nominee isn’t bound by his party’s platform, the platforms are still significant as a statement of the party’s principles and governing intentions, and it says something about a presidential nominee if he chooses to stand behind them. Richard Nixon, when he was the GOP presidential choice in 1960, spent a lot of his political capital to persuade the platform committee to make the party’s civil rights plank more progressive. Will Barack Obama or Mitt Romney make any similar efforts to resist the ideological inclinations of their party bases? Stay tuned.

Geoffrey Kabaservice is a columnist for The New Republic and a former assistant professor of history at Yale University. His most recent book is Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, From Eisenhower to the Tea Party (Oxford University Press, 2012). Read his previous blog post: “Newt Gingrich, Chameleon Politician.”

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for four weeks as the United States discusses the upcoming American presidential election, and Republican and Democratic National Conventions. Last week our authors tackled the issue of money and politics. This week we turn to the role of political conventions and party conferences (as they’re called in the UK). Read the previous blog post in this series: “Romney needed to pick Ryan.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Hegel on an ethical life and the family

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was born on this day, 27 August, in 1770. Hegel’s Outlines of the Philosophy of Right is one of the greatest works of moral, social, and political philosophy. It contains significant ideas on justice, moral responsibility, family life, economic activity, and the political structure of the state — all matters of profound interest to us today. Here is an extract from Hegel’s thoughts on the family.

Third Part: Ethical Life, Sub-section 1: The Family

158. The family, as the immediate substantiality of spirit, is specifically characterized by love, which is spirit’s feeling of its own unity. Hence in a family, one’s disposition is to have self-consciousness of one’s individuality within this unity as the essentiality that being in and for itself, with the result that one is in it not as an independent person but as a member.

Addition: Love means in general terms the consciousness of my unity with another, so that I am not in isolation by myself but win my self-consciousness only through the renunciation of my independence [Fürsichsein] and through knowing myself as the unity of myself with another and of the other with me. Love, however, is feeling, i.e. ethical life in the form of something natural. In the state, feeling disappears,; there we are conscious of unity as law; there the content must be rational and known to us. The first moment in love is that I do not wish to be a self-subsistent and independent person and that, if I were, then I would feel defective and incomplete. The second moment is that I find myself in another person, that I count for something in the other, while the other in turn comes to count for something in me. Love, therefore is the most tremendous contradiction; the understanding cannot resolve it since there is nothing more stubborn than this point [Punktualität] of self-consciousness which is negated and which nevertheless I ought to possess as affirmative. Love is at once the producing and the resolving of this contradiction. As the resolving of it, love is unity of an ethical type.

159. The right which the individual enjoys thanks to the unity of the family, and which is in the first place simply the individual’s life within this unity, takes on the form of right (as the abstract moment of determinate individuality) only when the family begins to dissolve. At that point those who should be family members both in their disposition and in actuality begin to be self-subsistent persons, and whereas they formerly constituted one specific moment within the whole, they now receive their share separately and so only in an external fashion by way of money, food, educational expenses, and the like.

Addition: The right of the family properly consists in the fact that its substantiality should have determinate existence. Thus it is a right against externality and against secession from the family unity. On the other hand, to repeat, love is a feeling, something subjective, against which unity cannot make itself effective. The demand for unity can be sustained, then, only in relation to such things as are by nature external and not conditioned by feeling.

160. The family is completed in these three phases:

(a) marriage, the form assumed by the concept of the family in its immediate phase;

(b) family property and assets (the external existence of the concept) and attention to these;

(c) the education of children and dissolution of the family.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was a revolutionary German philosopher and leader in German Idealism. His penetrating analysis of the causes of poverty in modern civil society was to be a great influence on Karl Marx. Hegel shows that genuine human freedom does not consist in doing whatever we please, but involves living with others in accordance with publicly recognized rights and laws. He demonstrates that institutions such as the family and the state provide the context in which individuals can flourish and enjoy full freedom. Hegel’s study remains one of the most subtle and perceptive accounts of freedom that we possess, and this newly revised translation makes it more accessible than ever. The Oxford World’s Classics edition of Outlines of the Philosophy of Right incorporates Hegel’s lecture notes within the text and provides a glossary of key terms, up-to-date bibliography, and invaluable notes. The editor, Stephen Houlgate, is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Warwick and is the author of Hegel, Nietzsche and the Criticism of Metaphysics; An Introduction to Hegel: Freedom, Truth and History; and The Opening of Hegel’s Logic: From Being to Infinity.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Delirium in hospital: Bad for the brain

Taking an elderly friend or relative to hospital is a painful experience for most people, and is often made worse when they become confused and disorientated during their stay.

This acute confusional state is called delirium. Long thought to be thought to be little more than a temporary side effect of other illness, ground-breaking new research suggests that delirium in fact has long-lasting negative impacts on the brain.

Delirium is extremely common, affecting around 120 people in a typical 1000-bedded hospital. People with delirium can lose their bearings, forgetting where they are. They may even become very distressed because they imagine that hospital staff or even visiting relatives are part of a conspiracy to harm them. Delirium is also associated with an increased risk of new and permanent admission to a nursing home, and death. But less than a quarter of cases are formally detected in hospitals.

Delirium is the result of illness – often an infection, a reaction to medications, or an operation – but it has generally been assumed that it is short-lived and benign. This assumption is wrong. Though delirium usually ends when the underlying causes are treated, this new study suggests that it may in fact be associated with new damage to brain, accelerating the path to dementia.

The personal and societal costs of dementia are enormous. In the UK, we spend 23bn annually across health and social care – already more than expenditure on cancer and heart disease combined. There are no proven methods of preventing dementia, and treatments are only modestly effective. So any knowledge of methods of reducing the risk of dementia is extremely valuable. This study implies that delirium prevention might actually prevent or delay the onset of dementia. Importantly, delirium prevention has been well-studied, and has been shown to work.

This study from the University of Cambridge and the University of Eastern Finland investigated how delirium affected the risk of future dementia in a study of persons aged 85 and older; the study was named Vantaa85+ after the city where it was carried out.

Cognition was assessed at regular intervals over 10 years, before and after episodes of delirium. This was a major advantage, because other studies of hospital patients were unable to establish a person’s cognitive function prior to delirium and therefore be confident that the delirium was indeed associated with new changes.

Vantaa85+ reliably determined that delirium was associated with worse cognition in every way: increased risk of dementia, worsening severity if already diagnosed with dementia, and faster trajectory of cognitive decline. Delirium was also associated with greater levels of physical dependence following an episode.

The study is remarkable for specifically involving persons aged 85 and older because very old individuals are hardly ever represented in research on ageing and dementia. Another strength was that everyone of this age in the town was recruited – even if they were in institutional care, or already had dementia – so the results are generalisable to the wider population of older persons. Exceptionally, over half the participants agreed to donate their brains for autopsy. There is a continuing gratitude to the brain donors and their families for the scientific legacy they provided.

The findings from the autopsy studies were the first attempt to understand brain changes in relation to a population known to have had delirium. We know that dementia can result from a number of aberrant processes (e.g. deposition of abnormal proteins, blockages in blood vessels). However, when individuals had a history of delirium and dementia, these standard neuropathological markers were not enough to explain the dementia, raising the possibility that completely novel process led to dementia after delirium.

The work should spur on basic science research investigating the mechanisms underlying the relationship between delirium and long-term cognitive impairment.

Returning to the idea that delirium prevention may lead to dementia prevention, this should have a clinical impact on how delirium is managed in hospital. This should start with hospitals introducing formal programmes for delirium detection and prevention. On a personal note, family members should urge doctors responsible for their relatives’ care to be aware of, and try to control, delirium as a real threat to long-term health rather than a passing inconvenience.

Daniel H.J. Davis MB ChB is based at the Institute of Public Health, University of Cambridge. Brain: A Journal of Neurology has granted free access to the full paper on this topic, “Delirium is a strong risk factor for dementia in the oldest-old: a population-based cohort study“, which is co-authored by Daniel Davis.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

August 26, 2012

Romney needed to pick Ryan

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for four weeks as the United States discusses the upcoming American presidential election, and Republican and Democratic National Conventions. Last week our authors tackled the issue of money and politics. This week we turn to the role of political conventions and party conferences (as they’re called in the UK).

By David C. Barker and Christopher Jan Carman

Congressman Paul Ryan (R-WI), the new Republican vice presidential nominee, has many virtues as a candidate. He is smart, charismatic and energetic, and he hails from a competitive but usually blue-leaning state that the GOP would like to secure into the red column. But one of Ryan’s virtues stands out above the rest for the Tea Partiers and other conservatives whom Governor Romney is still trying to win over. Ryan is perceived as being a person of conviction — someone who comes to his policy positions based on his commitment to certain ideological principles, and who will not alter those positions based on changes in what his constituents may want (i.e. polls). He doesn’t shy away from the unpopular House budget from the last two years that bears his name, which would have saved billions of dollars by turning Medicare into a voucher program, among other things. And that is just one example. Conservatives admire Ryan for “sticking to his guns.”

Mitt Romney & Paul Ryan at a rally in Norfolk, VA. Photo by James Currie, 11 August 2012. Creative Commons License.

This reputation of Ryan’s stands in contrast, of course, to the reputation Romney has garnered (fairly or not) as an opportunistic flip-flopper who panders to public opinion. And this is why Romney stands to gain — with the Republican base at least — with what is otherwise being viewed as a risky, Hail Mary pass of a pick. (For all of Ryan’s political virtues, after all, he also has some drawbacks. He is quite young and relatively inexperienced for a top-of-the ticket type of candidate, and he is viewed by many as ideologically extreme and rigid.) What Romney needs more than anything else is for “his people” to trust him enough to show up in droves this November. Without that, he has no chance of beating Obama — or even coming close. And for the base to do that, they need to have someone on the ticket whom they feel like they can trust and believe in. By picking Ryan, Romney has helped his case with that all-important constituency.

If Romney were a Democrat, he probably wouldn’t have to worry about such things. After all, Al Gore, John Kerry, and Bill Clinton labored under the “pandering flip-flopper” label as well, but it didn’t hurt them with the Democratic base in the way that Romney suffers with his base. The reason is that Democrats actually tend to appreciate politicians whose policy positions evolve in service to changes in public opinion.

In other words, liberal Democrats on average tend to embrace the popular democratic vision much more readily than conservative Republicans do. On the other hand, conservative Republicans on average tend to express greater appreciation for elected officials who “lead” based on internalized principles, thus spurning capricious public opinion. What this means is that liberal, “blue” America is a different type of representative democracy than is conservative “red” America — one where citizens have much more direct, policymaking power over what their representatives do.

David C. Barker and Christopher Jan Carman are the authors of Representing Red and Blue: How the Culture Wars Change the Way Citizens Speak and Politicians Listen. David C. Barker is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Pittsburgh and Director Designate of the Institute of Social Research at California State University – Sacramento. Since receiving his PhD from the University of Houston in 1998, he has authored dozens of scholarly journal articles on the subjects of public opinion and electoral politics. His previous book, Rushed to Judgment? Talk Radio, Persuasion, and American Political Behavior, was nominated for several awards. Christopher Jan Carman is Senior Research Lecturer in Government at the University of Strathclyde. He received his PhD from the University of Houston in 2000. He is also a co-author of Elections and Voters in Britain, 3rd ed. He has served as a consultant for the Scottish Parliament and a psephologist for BBC News.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 25, 2012

Martin Kemp vs John Gittings: Icons of Peace

The world famous Edinburgh International Festival has kicked off, beginning three weeks of the best the arts world has to offer. The Fringe Festival has countless alternative, weird, and wacky events happening all over the city, and the Edinburgh International Book Festival is underway. Throughout the Book Festival we’ll be bringing you sneak peeks of our authors’ talks and backstage debriefs so that, even if you can’t make it to Edinburgh this year, you won’t miss out on all the action.

Today, John Gittings and Martin Kemp will be discussing icons of peace. Human history is dominated by war, but can we forge a different narrative? In The Glorious Art of Peace, former Guardian journalist John Gittings argues that progress depends on a peaceful environment, identifying iconic proponents of peace such as Confucius and Gandhi. Art historian Martin Kemp‘s Christ to Coke looks at the creation of some of our peacetime icons and traces the things they have in common.

By John Gittings

Images of war are familiar to us in ancient sculpture and epic literature, and it is sometimes suggested that images of peace only occur in more modern times. Yet peace has always been as much a human concern as war, and if we look carefully we will find it early on in human artistic endeavour.

Homer’s Iliad is a challenging example. Can this chronicle of the bloodiest exploits of war also reflect the human quest for peace? In fact, woven into this narrative of war, there is a counter-narrative of peace — peace frustrated but very much desired. Homer’s account of the Shield of Achilles may even be regarded as the world’s first recorded example of anti-war art.

The shield which is being prepared by the heavenly blacksmith Hephaestus for the Greek hero Achilles to carry into battle should have been decorated — as such shields in the Mycenaean age always were — with fierce images of lions or the Medusa’s head to terrify the enemy. Instead Homer depicts in vivid detail a series of images of peace and plenty: a well-governed city, festivals and dancing, ploughing and the gathering of grapes. The only scene of war is of an armed ambush which has gone disastrously wrong. Homeric scholars have puzzled over this passage but its meaning is clear. This, Homer is telling us, is the peace to be preferred to war.

In literature as in art, the argument for peace was put as strenuously as the case for war, but it can be hard to locate. Bookshops and libraries are more likely to stock The Prince by Machiavelli — or his Art of War — than The Education of a Christian Prince by his exact contemporary Desiderius Erasmus — or his Complaint of Peace. The Oxford Reader on War (1994) is easier to find than the comparable Oxford Reader on Peace Studies (2000).

Without long periods of peace, human civilisation could not have developed, yet historians often regard peace merely as the “interval between war.” Thucydides relates at length the speeches in the Athenian assembly of those advocating war with Sparta; the objections of the peace party are given in a few lines. The rich narrative of peace thought and argument from Erasmus onwards, through Rousseau, Kant, and other thinkers of the Enlightenment into the 19th century is barely known today. Victor Hugo is celebrated for his novels, but his powerful speeches and poems on peace remain untranslated.

The argument from the mid-19th century onwards for international arbitration and disarmament, and for support of the League of Nations during the interwar years, tends to be written off as utopianism or “appeasement”. During the Cold War, peace was a partisan issue and the very word became suspect. Picasso’s Guernica (1937) had been universally admired, but his Massacre in Korea (1951) was dismissed as pro-Soviet propaganda.

Guernica by Pablo Picasso, 1937. Museo Reina Sofia. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

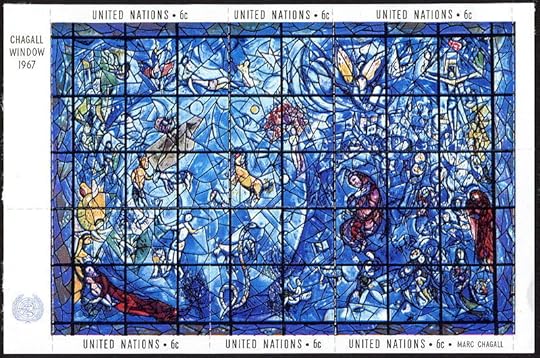

Depictions of war, with its massed arrays of weapons and warriors, are straight-forward and often routine, but peace requires more imagination. When the 1918 armistice was signed, Manet produced another of his great paintings of water-lilies. Chagall’s wonderful stained glass window in the United Nations is rich with peaceful symbolism. It is worth making the effort to discover, in our art and literature, the alternative imagery of peace.

The Chagall Window at United Nations, 1967. Source: Wikimedia Commons

John Gittings worked at The Guardian (UK) for twenty years. He is on the editorial team of the new Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace (2010) and is author of The Glorious Art of Peace: from the Iliad to Iraq (2012). Read Gittings on the real lessons of the Cuban Cold War crisis and World Humanitarian Day.

View more about this book on the

By Martin Kemp

The cliché has it that “the devil has the best tunes”. Is it the case that war has produced more varied and memorable images than peace? Hell boasts a wider range of engrossing activities than Paradise. Even Dante struggled to evoke repeated images of celestial bliss. He clearly relished the word-painting of Hell and Purgatory.

What are the great icons of peace? Picasso’s Dove for the World Congress of Advocates of Peace in Paris? John Gittings has come up with a good set of candidates. Maybe it’s less problematic with literature than the visual arts.

It’s much easier to think of famous images of war, even including the great lost and incomplete battles painted by Leonardo and Michelangelo. Christian imagery is more blessed with vivid depictions and symbols of suffering than of spiritual peace.

Photography has produced indelible records of war, not least Nick Ut’s famous photograph of the napalmed girl running down a route one in Vietnam, which has clear affinities with Picasso’s Guernica. The photo and the painting serve to show that images that promote or can be used for anti-war stances are not the same as representations of peace in its own right.

Perhaps it is the case that peace is more easily defined in terms of its negatives rather than its positives, as John Gittings acknowledges. Peace is at its most basic a lack of conflict. It’s easier to show what is happening (i.e. violence) than what is not. Of the eleven key images in Christ to Coke probably only the heart is primarily evocative of wholly positive sentiments — unless we are devoted to Coke — but even here representations of broken hearts and the bleeding heart of Christ radically undermine the positive connotations.

There may be a parallel here with contemporary political debates, in which well-being and happiness have been suggested, entirely properly, as goals for society. But they are more difficult to define and above all measure than poverty, illness, malnutrition and homelessness. Happiness and peace may best be definable by an inner sense that we recognise it when it’s there, whereas war is defined by something very tangible that lies outside us.

The most compelling images of peace may be more elliptical and associative than direct. I am thinking of a radiant Turner sunset or a Corot of a sylvan idyll. There is obviously some kind of biological basis here, invoking environments that sustain our body and delight our senses. There are likely to be all kinds of cultural differences that shape how the basics are expressed.

All in all, the art of peace is a slippery but hugely important topic. We hope the audience at Edinburgh can help.

Martin Kemp is Emeritus Professor in the History of Art at Trinity College, Oxford. He is the author of Christ to Coke: How Image Becomes Icon, The Oxford History of Western Art, Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man, Leonardo, and Seen | Unseen: Art, Science, and Intuition from Leonardo to the Hubble Telescope. He blogs at Martin Kemp’s This and That.

View more about this book on the

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits:

Logo courtesy of Edinburgh International Book Festival

Guernica by Pablo Picasso, 1937. Museo Reina Sofia. Copy of artwork used for the purposes of illustration in a critical commentary on the work. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Chagall Window at United Nations, 1967. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Stonewalling Progress

Leading British gay rights charity, Stonewall, have produced a new report into the extent of homophobia in British schools. Surveying 1,600 sexual minority youth, it finds that 55% of lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) students experience homophobic bullying, 96% hear “homophobic remarks” and that homophobia frequently goes unchallenged. This builds on their 2007 report, which argued that homophobia was “endemic” and “almost epidemic” in British schools. These are harrowing findings, but they obscure rather than reveal the social dynamics of many British schools today.

It is important to recognize that no peer-reviewed, academic research has ever documented such high levels of homophobia in the UK. Indeed, while scholars found schools to be homophobic in the 1980s and early 1990s, more recent research, including my own, has argued that there has been an erosion of homophobia in school settings. I suggest this difference in findings is the result of methodological and analytical flaws in Stonewall’s survey.

It is important to recognize that no peer-reviewed, academic research has ever documented such high levels of homophobia in the UK. Indeed, while scholars found schools to be homophobic in the 1980s and early 1990s, more recent research, including my own, has argued that there has been an erosion of homophobia in school settings. I suggest this difference in findings is the result of methodological and analytical flaws in Stonewall’s survey.

The first issue is one that always besets quantitative research on sexual minority youth — participant recruitment. Although the report itself does not document the methods of recruiting sexual minority youth, one of the authors wrote that it involved contact with “LGB groups, school and college portals, FB, a few tweets” (personal correspondence). It is well-known that the young people who attend LGB groups, and are known by teachers as LGB in schools, tend to be those who have had bad experiences, oftentimes because of their gender non-conformity. By recruiting participants from these groups, the report is biased toward hearing the horror stories — from those who have had bad experiences — and likely has more to say about gender non-conformity than sexual minorities. While bullying based on gender non-conformity is as horrific a problem as bullying for any other reason, it skews the results to be about a particular type of LGB youth.

The second problem is one of attrition. Although Stonewall have not made the survey questions available, I read through them when the survey was live. It took 15 minutes to read all of the questions, which were repetitive and asked if the participant had experienced a wide range of events (from positive acts to extreme homophobia). The long survey biases the report towards those who have had bad experiences; young people who have suffered homophobia will be far motivated to complete the survey than those whose sexuality has not been a significant issue. Highlighting this, a gay male academic colleague of mine took the survey, and reported to me that he quit half way through; it was just too long. This, of course, brings up another issue; anyone can fill the survey out and there is no method of controlling for actual school-attending youth.

None of these issues would be significant if Stonewall had tempered their claims of generalizability. The School Report 2012 is an important document to the extent that it helps illuminate the troubled lives of students who do suffer sustained homophobic harassment. In other words, it demonstrates how students who have a bad time have a bad time. What it does not and cannot do, however, is provide generalizable statistics on the experiences of LGB youth in schools. The great shame, then, is that the report consistently makes claims about the experiences of all LGB students, never recognizing the limitations of its sample.

This overstating is evident in other ways. For example, the quotes given to support statements in the report frequently appear to be exemplars of the worst case. So when the report claims that “more than half” of LGB students “experience homophobic bullying,” the accompanying quote refers to a death threat where someone would “shove a knife up my arse and in my throat.” This is sensationalist reporting and not representative research, and it serves to obscure the reality of many LGB people’s lives. Furthermore, Stonewall’s continued insistence that ‘that’s so gay’ is homophobic (discussing it in a section on bullying) demonstrates a lack of willingness to engage with contemporary debates on homophobia in school settings. And while it finds that many LGB students dislike ‘that’s so gay’, it does not account for whether the youth interpret this phrase as bullying.

The overwhelming emphasis on the negative aspects of homophobia in Stonewall’s School Reports is somewhat perplexing. After all, they have a range of publications examining changing attitudes to homosexuality in the United Kingdom, most of which document significant improvements with some negative issues. For example, in Living Together, Cowan (2007) found that 87% of British citizens report they would be comfortable with their MP being gay, and 86% would be comfortable if a close friend was gay. Yet when it comes to schools, Stonewall’s presentation of the data is unremittingly negative. It may be that Stonewall staff are unaware of the methodological and analytical flaws, or that they are influenced by their own experiences at school. Or maybe they have found an area that receives great media attention and loosens the pockets of financial donors. Whatever the reason, it is significant that The School Reports are so very negative despite seemingly positive findings located in its latter half.

It is not my argument that homophobia is no longer present in school settings. Rather, my argument is that what is needed is high quality, methodologically rigorous research to examine when and why this occurs. This would involve researchers going into schools and surveying a range of students. It would require time, money and effort on recruiting the full panoply of sexual minority youth to ensure that all their voices are heard. This takes a great deal more work than simply posting a survey online and recruiting through existing networks who are likely to have had a particular school experience. The School Report 2012 is a missed opportunity to inform the debate on homophobia in British schools, but the greater concern is that its overwhelmingly negative tone may encourage kids to stay in the closet.

Mark McCormack is a qualitative sociologist at Brunel University in England. His research focuses on the changing nature of masculinities among British youth. In The Declining Significance of Homophobia: How Teenage Boys are Redefining Masculinity and Heterosexuality, he examines how decreased homophobia has positively influenced the way in which young men bond emotionally and interact in school settings. You can follow him on Twitter @_markmccormack.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Gay Men Hands Clasped. Photo by Lisa-Blue, iStockphoto.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers