Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1035

August 8, 2012

Two English apr-words, part 2: ‘Apricot’

Fruits and vegetables travel from land to land with their names. Every now and then they proclaim their country of origin. Such is the peach (though of course not in its present-day English form), whose name is a borrowing of Old French peche (Modern French pêche), ultimately from Latin Persicum malum “Persian apple.” It follows that the noun peach began its life as an adjective. To a modern speaker of French and English the distance between pêche ~ peach and persicum (with its phonetic pit gone) is unbridgeable, but Swedish persika, Dutch perzik, and Russian persik are quite transparent. Likewise, quince goes back to malum cotoneum ~ cydoneum, from Greek (Cydonea, now Canea). Even apple, the most often discussed name of a fruit, has been traced to the Italian place name Abella, but today few Indo-European scholars share the traditional view, even though the origin of this common European word remains a matter of dispute.

English etymological lexicography began with John Minsheu (Latinized as Minshæus), the author of a dictionary published in 1617. He wasn’t ahead of his age and few of his proposals present interest to us. Nor does anyone today outside the extremely narrow circle of language historians consult his dictionary. But when Minsheu’s name turns up in modern works, it sometimes makes people wonder or even feel indignant at his naiveté. For example, he told the often-quoted and universally derided story of a London boy who had no notion of what a horse looked like (!). When he saw or rather heard one, he asked his father about the source of neighing. Some time later he heard a rooster (in those days roosters were usually called cocks) and inquired: “Does the cock neigh too?” And such is allegedly the origin of the word cockney, signifying a dunce (this must have been a popular anecdote). Cockney is still a word of doubtful etymology, so we have relatively little to boast of.

Minsheu rather cautiously (much to his credit) suggested that apricot was derived quasi from Latin in aprico coctus “ripened in a sunny place.” (Apricus, along with Middle High German æbre, was mentioned in the post on April.) It all happened four hundred years ago. The learned lexicographer (and he was undoubtedly a learned man) could have run into Shakespeare in the street, with one of them listening to a neighing horse and the other warming himself in a sunny place. At that time, scientific etymology had to wait at least two centuries before it made its first steps, but Stephen Skinner, the author of the next etymological dictionary of English (1671), already wrote a good entry on apricot. Let it also be noted that abr- in apricot changed to apr- for no obvious reason (b didn’t have to become devoiced before r). Eduard Müller (or Mueller), a reliable nineteenth-century German etymologist, and The Century Dictionary, the latter with reference to Minsheu, admitted the possibility that the change was due to an association with apricus, and thus a product of folk etymology. Be that as it may, in one respect Minsheu was right; apricot is not a native name. It is a classical migratory word, a Wanderwort, as the Germans say, or to use a more elegant French term, un mot voyageur. The beginning of the story takes us to Ancient Rome.

Still Life by Paul Cézanne. Source: wikipaintings.org.

The Romans first called the fruit malum (or prunum) Armeniacum “Armenian apple (or plum)” and after that malum praecoquum “early ripening apple” (compare Engl. precocious) because apricots were considered to be a kind of peaches, but they ripen first. Latin coquere means “cook” (the English verb is a borrowing of it). Consequently, praecoquere means “cook, boil beforehand.” Our precocious children are (figuratively speaking) ready for use (cooked) too soon. The Greeks pronounced the Latin adjective as praikókon, but in Byzantium it changed to beríkokkon. In this form it became known to the Arabs, who shortened it and added the definite article. The result was al-burquq and al-barquq. The Modern Romance names of the apricot owe their existence to Arabic: Spanish albaricoque, Portuguese albricoque, Italian albercocca, albicocca (in dialects often without the Arabic article), and French apricot. It may seem more natural to suppose that the point of departure was the East rather than Rome, but things probably happened as described above.

English and French (French perhaps via Provençal) got this word from Portuguese or Spanish. The earliest recorded French form (1512) is aubercot and the earliest English one (1551) abrecock. Modern Engl. apricot (never mind the ways the first vowel sounds in America) was altered to adjust partly to French abricot (a usual procedure), but in French final t is mute. In some European languages, the name of the apricot ends in -s: German Aprikose, Dutch aprikoos (in Minsheu’s days it was still abrikok), Swedish and Norwegian aprikos, Danish abrikos, and Russian abrikos. The origin of final -s in the lending language is unclear (from the French plural? Rather unlikely). The vernacular Arabic name of the fruit is mishmish and mushmush. The recollection of the “Armenian apple” is not quite lost in modern languages. We discern the Armenian echo in Italian armillo, in southern German marille (with many variants), and in Dutch dialectal merelle ~ morille “sour cherry,” apparently under the influence of Latin amarellus “sour” (familiar to us from the sweet (!), but almond-flavored liqueur amaretto (Latin amar means “bitter”)). Swiss barelelli and barillen are reminiscent of the Italian dialectal bar- names. The index to Bengt Hasselrot’s detailed study of the linguistic geography of the apricot contains close to four hundred variants of the names used for this fruit.

If Leo Spitzer guessed well, there is one more trace of the apricot’s name beginning with ber-. French s’emberlucoquer ~ s’emberlificoter means “to feel confused” and when the verbs were not reflexive, they had the sense “deceive, seduce.” (Today they may be glossed as “have crazy ideas in one’s head.”) Fruits and plants whose form makes people think of genitals (and there is very little in the world that doesn’t) often become slang words for penis and vagina; the date, mandragora, and the fig are notorious in this respect. The apricot, as Spitzer pointed out, once stood for both “vulva” and “stupid.” He reconstructed the Old French noun birelicoq “blockhead” going back to Italian biricoccola ~ bericocola. The family name Billicozzo, recorded in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Tuscany, and Billicocco, the name of a devil occurring in Dante, allegedly contain the same root. (Regrettably, scurrilous allusions did not spread beyond the Romance speaking world. Otherwise, Shakespeare would not have missed such a chance, especially in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where the word occurs as part of a list; in Richard II, the context is sad and non-erotic.)

The peregrinations of the apricot through Europe become more and more exciting at every step. But even without a brief stay in Tuscany, the way of the fruit is memorable: Rome — Greece — Byzantium — Arabia — the Iberian Peninsula — Italy, France, Germany, England, and the rest of the continent, from Scandinavia in the north to Russia in the east. The word, as Skeat put it, reached us in a very roundabout manner. In his Concise Dictionary, in which all words were supposedly expected to shrink, the manner is called indirect.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

How exactly did Mendeleev discover his periodic table of 1869?

The Periodic Table

By Eric Scerri

I just returned home from being interviewed for a new Nova program on the mystery of matter and the search for the elements. It was very gratifying to see how keen the film-makers were on understanding precisely how Mendeleev arrived at his famous first periodic table of 1869. This in turn meant that I had to thoroughly review the literature on this particular historical episode, which will form the basis of this blog.

The usual version of how Mendeleev arrived at his discovery goes something like this. While in the process of writing his textbook, The Principles of Chemistry, Mendeleev completed the book by dealing with only eight of the then known 63 elements. He ended the book with the halogens, including chlorine, bromine and iodine. On moving on to the second volume he realized that he needed an organizing principle for all the remaining elements. Before arriving at any new ordering principle he started volume 2 by discussing another well-known group of elements, the alkali metals that include lithium, sodium and potassium.

Mendeleev then wondered what elements should be mentioned next and toyed with the idea of turning either to the alkaline earth metals like calcium, barium and strontium or perhaps some intermediate elements including zinc and cadmium which share some but not all the properties of the alkaline earths. Another possibility which he contemplated was a group containing copper and silver which show variable valences of +1 or +2 and so could represent a stepping stone between the alkali metals and the alkaline earths which display oxidation states of +1 and +2 respectively.

Then on 17 February 1869, Mendeleev’s world virtually stood still and it continued to do so for a further 2 or three days during which he essentially arrived at his version of the periodic table and the one that had the greatest impact on the scientific community. It is generally agreed that this was the discovery of the periodic table, although at least five other versions had been previously published, albeit rater tentatively.

Figure 1. Mendeleev’s sketched notes on the back on the invitation to visit a local cheese co-operative. The lower figures show his calculations of the differences between the atomic weights of sodium and lithium (23 – 14* = 9), potassium and magnesium (39 – 24 = 15), rubidium and zinc (85 – 56 = 20), cesium and cadmium (133 – 112 = 21). The lowest line of numbers is Mendeleev’s comparison of his own calculations with the previously published equivalent weights of Dumas, namely lithium (7), magnesium (12), zinc (32) and cadmium (56).

*In fact Mendeleev is using twice the value of the atomic weight of lithium which is seven, hence the value of 14. This seems to be an afterthought since the numbers written underneath 14 and 9 seem to be 7 and 16 in which Mendeleev considered the actual value of lithium, namely 7.

On the 17th of February Mendeleev decided against going on a consultancy visit to a local cheese co-operative in order to stay at home to work on his book. It appears that at some point in the morning he took the invitation to the cheese co-operative and turned it over in order to sketch some ideas about what elements to treat next in his book (figure 1). This document still exists in the Mendeleev Museum in St. Petersburg and it is frequently brought out of the coffers for visiting documentary film-makers wanting to capture Mendeleev’s crucial moment of discovery.

The sketched symbols suggest that Mendeleev’s first attempted to compare the alkali metals with the intermediate group containing zinc and cadmium. He calculated differences between pairs of elements belonging to each of these groups in the hope of finding some significant pattern. But he appears to have been disappointed because the differences between the corresponding elements he considered show no regular pattern.

Nevertheless, Mendeleevdid not quite dismiss the idea of following the alkali metals by the group containing zinc and cadmium because this is precisely what he did in a second classic document in which he now included many more known groups of elements in the first of two tables of elements which appear on the same sheet of paper (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Mendeleev’s two preliminary periodic tables. In the lower table the alkali metals have been raised from the bottom of the table and placed between the halogens and the alkali earths.

Figure 3. Clarification of figure 2. The alkali metals have moved from close to the bottom of the upper table to a place between the halogens and the alkali earths in the lower table. This suggests Mendeleev’s decision to no longer place the intermediate elements (Cu, Ag or Zn, Cd) after the alkali metals as shown in the upper table.

Whereas the upper table shows the zinc and cadmium group directly above the alkali metals, the lower of the two tables shows a rearrangement in which Mendeleev has decided to place the typical alkaline earth metals next to the alkali metals by moving the alkali metals up the table as an entire block. The net result is that the halogens are followed by the alkali metals, which in turn are followed by the alkali earths. The consequence of this move is that the sequence of atomic weights now appears more orderly than it did in the earlier upper table on the same page. As a result of this simple change Mendeleev appears to have realized that a successful periodic table requires not only a correct grouping of elements in adjacent rows but also a set of smoothly increasing sequences of atomic weights.

Here then is Mendeleev’s ‘aha’ or ‘eureka moment’. Here is where he first sees that the periodic table is a display of chemical periodicity that is itself a function of the variation of atomic weight. For example, note the atomic weight sequence of Cl (35.5), K (39) and Ca (40) in the lower table as compared with the less pleasing, although still increasing sequence of S (32), Cl (35.5), Ca (40), in the upper table that he had arrived at earlier in the day. Alternatively, consider the placement of K (39) which seems out of place next to Cu (63) in the upper table as compared to its proximity with elements of similar atomic weights in the lower table.

The essential point seems to be that Mendeleev began by considered groups of chemically similar elements and that the notion of ordering according to atomic weight came to him later. And this document appears to be precisely where he arrived at this conclusion.

Interestingly, the current director of the Mendeleev Museum, Professor Igor Dimitriev, disagrees with this account of the development. He believes that the document sketched on the back of the invitation from the cheese co-operative (figure 1), did not precede the two-tables on a single sheet document (Figures 2 and 3). He does not believe that the document shown in figure 1 had such an influence of the development in Mendeleev’s thought process as has generally been supposed.

Dimitriev’s objections are based on his proposal that groups of elements were not widely recognized at this time and that it was rather the sequence of atomic number values that led the way for Mendeleev in the course of his discovery of the periodic table. But this may be a little short-sighted in my view, because if one looks further afield at the earlier evolution of the periodic table among other chemists, working in other countries, one finds that groups of elements had been well recognized for a long time prior to Mendeleev’s work. This includes the work of Döbereiner, Gmelin, Lenssen, Pettenkoffer, De Chancourtois, Newlands, Odling, Hinrichs, and Lothar Meyer just to mention a few relevant names.

There is little doubt in my own mind that the notion of groups of chemically similar elements was well rather established and that it would have been natural for Mendeleev, who followed the above named authors, to begin with this notion. On the other hand the idea of using the sequence of increasing atomic weights to order the elements was nowhere near as well-established and it had only been a few years since the Karlsruhe conference of 1860 at which atomic weights had been unified and rationalized to produce a more or less definitive list of values that every chemist agreed with.

But you the reader may now be thinking, “but surely Dimitriev knows all of this?”. I think the answer to this question is both yes and no. I suspect that his custodianship of the St. Petersburg museum and archives may have led Dimitriev to concentrate upon the work of Mendeleev above that of all others. Finally, could it be that Dimitriev, who like Mendeleev is a Russian, may have allowed national pride to influenced his judgment of the issue and to perhaps downplay the contributions of foreign scientists.

But let’s return to Mendeleev’s discovery. What did he do after he had produced the lower table in figure 2? The popular story is that he then set about playing a game of chemical solitaire or ‘patience’ using a set of cards that he had carefully made-up to include the symbols for all the known 63 elements and their atomic weights. The aim of this well-known game is to arrange the cards in two senses. First of all the cards must be in separate suits and secondly they must be in order of decreasing values starting with king, queen, knave, ten and so on reading from left to right. Unfortunately no such set of cards has ever been found among Mendeleev’s belongings which raises the question as to whether the story may be merely apocryphal. (The plot thickens further when one learns that Mendeleev kept almost everything as soon as he realized that he would become famous. No such cards have ever been found, although it could just be that Mendeleev had not quite realized his impending fame at this stage.)

But I don’t think it really matters whether the story of the cards is actually true or not. The game of chemical solitaire provides such a good analogy that it is more important to focus on that than trying to determine whether Mendeleev actually used this approach or not. In the case of the periodic table, there is a beautiful analogy given that the elements are arranged in groups as opposed to suits, and along another direction they are arranged in order of increasing values of atomic weights, as opposed to decreasing values on cards.

Although Mendeleev was a true genius for discovering the periodic table, there is a real sense in which the periodic system is inevitable and provided by Nature itself. It was just a matter of uncovering this profound truth. What I am trying to get at is that Mendeleev did not have any choice in how to arrange the elements. At the end of the day they had to be arranged in the same way as a deck of playing cards must be arranged in the game of patience. There is no two ways about it. When the game is completed everyone can see it.

It is the same with the arrangement of the elements. Although the pattern could only be dimly seen at the beginning this was partly because of inaccurate values of atomic weights and because the correct ordering principle had not yet been recognized. Once it was recognized the game was virtually over and it became a matter of filling-in the remaining details. Of course these details were not quite as trivial as I may be implying. They included an entire group of missing elements that neither Mendeleev nor anyone else had predicted — the noble gases. They included the discovery of several missing elements, many of whose properties Mendeleev succeeded in predicting rather well. They also included the vexing fact that atomic weight doesn’t provide the optimal ordering principle.

If atomic weight ordering is followed strictly as many as four pairs of elements occur in reversed positions. In order to clear up this further issue it had to wait until the discovery of atomic number in 1913 and 1914 but that will be the topic of a future blog. The broad outline of chemical solitaire was worked out by Mendeleev above all other contributors and it was first glimpsed on that famous day of 17 February 1869. (This is the date according to the older Julian calendar that was used in Russia at this time. It differs from the more recently developed Gregorian calendar that was introduced to many other western countries in 1582. In 1869 the difference between the two calendars amounted to 12 days.)

Eric Scerri is a chemist and philosopher of science, author and speaker. He is a lecturer in chemistry, as well as history and philosophy of science, at UCLA in Los Angeles. He is the author of several books including The Periodic Table, Its Story and Its Significance, Collected Papers on the Philosophy of Chemistry, Selected Papers on the Periodic Table, The Periodic Table: A Very Short Introduction, and the upcoming A Tale of Seven Elements. You can follow him on Twitter at @ericscerri and read his previous blog post “The periodic table: matter matters.”

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Figures 1 & 2 from Mendeleev’s two incomplete tables of February 17, 1869.

Figure 1 source: Igor S. Dmitriev, “Scientific discovery in statu nascendi: The case of Dmitrii Mendeleev’s Periodic Law,” Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences, Vol. 34, No. 2, 2004.

Figure 2 source: B. M. Kedrov and D. N. Trifonov, Zakon periodichnosti…, Moscow: Izdatel’stvo “Nauka,” 1969 (via Heinz Cassebaum and George B. Kauffman, “The Periodic System of the Chemical Elements: The Search for Its Discoverer,” Isis, Vol. 62, No. 3, 1971).

Figure 3 Smith, J. R. (1975) ‘Persistence and Periodicity’, unpublished PhD thesis, University of London. Source: Eric Scerri.

Cyber War and International Law

It seems both timely and necessary to question whether public international law adequately protects states from the threat of cyber attacks. This is because states have become increasingly dependent upon computer networks and the information that they hold in order to effectively regulate their societies. It is therefore unsurprising that hostile states, individuals and non state actors have sought to attack computer networks of target states with greater frequency and ferocity. This is exemplified by the much-discussed cyber attacks against Estonia (2007), Georgia (2008) and Iran (2010). Indeed, a day barely seems to pass without the media reporting that a state has been a victim of a cyber attack.

Cyber attacks can of course take many different forms. On the one hand, a cyber attack can cause physical damage comparable to that caused by conventional weapons. A cyber attack can corrupt the operating system of a power plant and cause a nuclear meltdown, for example, or shut down civil aviation systems thus causing civilian aircraft to crash. On the other hand, a cyber attack may not cause any physical damage. Consider, for example, a cyber attack that appropriates sensitive data or causes key websites to cease functioning. However, this does not mean that cyber attacks causing non-physical damage does not affect adversely the security of a state. Indeed, the damage they can produce can be extremely serious. A good illustration would be a cyber attack that cripples a state’s financial sector or disables military defence systems.

The question then becomes whether international law is able to protect states against such cyber attacks that impact upon state security. Sure, international law has long sought to construct an international legal framework to protect states from hostile attacks from abroad: the jus ad bellum, as it is known. However, the jus ad bellum was created in the aftermath of the Second World War when the overwhelming threat to state security was represented by conventional weapons such as guns and bombs. An international legal framework, broadly represented by the United Nations (UN) Charter, was therefore constructed to address this type of threat: the threat of kinetic force. For example Article 2(4) UN Charter, which prohibits the threat or use of force among states, is generally regarded as encompassing only those acts that produce physical damage; namely, damage to physical property or death or injury to people. Similarly Article 51, which confirms a state’s inherent right to self-defence where an armed attack occurs, can only be engaged in those situations where there has been a grave use of force i.e. only where serious kinetic damage has been caused.

The conclusion, then, is that a cyber attack producing non-physical damage would seem to fall outside of the legal regime established by the UN Charter. The ability of the jus ad bellum to protect states from cyber attacks is therefore called into question. International lawyers must therefore dedicate attention to the application of the jus ad bellum to cyber attacks, seeking to reveal the deficiencies of the current legal framework and suggesting proposals for reform.

It is also important to consider the application of international humanitarian law (IHL) to cyber war. Crucially, IHL applies when there is an armed conflict. According to IHL, an armed conflict exists when there is exchange of hostilities between one or more parties. However, the question that arises is whether cyber hostilities that do not involve the use of kinetic force can give rise to an ‘armed conflict’ and, if they do, whether they need to reach a certain threshold. Even if cyber hostilities give rise to an armed conflict, the next question is whether the armed conflict is international or a non-international in character. This is because IHL maintains a firm distinction between these types of armed conflict and, more importantly, applies different legal regimes. The status of non-state entities or organisations and their links with states is also of paramount importance in this regard.

Cyber hostilities challenge many other established principles of IHL such as the principles of distinction and proportionality. These principles hold that civilians and civilian objectives should be distinguished from combatants and military objectives and that the action should be proportional to the military objective sought. However, in interconnected computer systems, adherence to these principles may prove difficult. For example, a cyber attack on a military computer system may incidentally but inevitably cause disproportionate damage to connected civilian systems and, consequently, may cause death or injury to civilians. A more intricate question is the status of those civilians who are involved in the design, installation or operation of cyber weapons. If it is concluded that they directly participate in hostilities they can be directly targeted. However, IHL’s definition of when an individual directly participates in hostilities was crafted in order to address situations such as when civilians chose to ‘farm by day, fight by night’ or provided ad hoc medical assistance to combatants. The point is that the application of this test to a qualitatively different scenario, such as those installing or operating computer systems, is very difficult.

These questions represent some of the most serious challenges that cyber war poses to IHL. As with the jus ad bellum, the role of the international lawyer is to question the adequacy of the application of IHL to cyber war and, where deficiencies are found, to postulate proposals for reform.

Dr. Russell Buchan is a lecturer in international law at the University of Sheffield and is an expert in the field of cyber war. Nicholas Tsagourias is Professor of International Law and Security at the University of Glasgow and has published widely in the area of international peace and security. Together they have worked on a special issue for the Journal of Conflict and Security Law. You can access the special issue, Cyber War and International Law, via Oxford Journals.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: information weapon, keyboard grenade. Photo by -antonio-, iStockphoto.

August 7, 2012

In memoriam: Robert Hughes

Oxford University Press is saddened to hear of the passing of Robert Hughes.

Robert Hughes was born in Australia in 1938 and lived in Europe and the United States since 1964. He worked in New York as an art critic for Time Magazine for over three decades from 1970 onward. He twice received the Franklin Jeweer Mather Award for Distinguished Criticism from the College Art Association of America. He is the author of numerous books, including Culture of Complaint: The Fraying of America, which Oxford University Press published in 1993. Publishers Weekly called it a “a withering, salubrious jeremiad.”

Robert Hughes is survived by his wife, two stepsons, brother, sister, and niece.

Robert Hughes

28 July 1938 – 6 August 2012

Vice Presidents at War

Much of the attention to Mitt Romney’s choice of a running mate will focus on whether the selection will influence the outcome of the election in November. (The short answer is probably not, unless he suddenly decides to think outside the proverbial box.) We might do better to spend more time considering how a vice president influences policy. I find that vice presidents have sometimes played a role in policy debates, but it is never decisive.

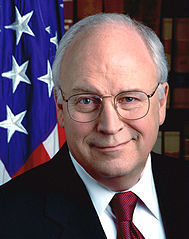

Dick Cheney stands out as the most visible vice president in the shaping of war policy, but visibility and influence should not be confused. After 9/11, Cheney’s was one of a number of voices in George W. Bush’s inner circle claiming that Saddam Hussein posed a risk to the United States. The vice president worried about another catastrophic attack and exaggerated the very slender evidence of connections between Saddam’s intelligence organization and al Qaeda. On August 26, 2002, he went so far as to claim that the administration had firm proof that Saddam possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD): “The Iraqi regime has in fact been very busy enhancing its capabilities in the field of chemical and biological agents, and they continue to pursue the nuclear program they began so many years ago.” His words caught the president and others off guard. Still, they adopted Cheney’s alarmist view — not because they believed he was correct but because it suited their purposes as they sought to build public support for military action. Cheney did not lead Bush to war. The decision, and the responsibility, rested with the president.

Dick Cheney stands out as the most visible vice president in the shaping of war policy, but visibility and influence should not be confused. After 9/11, Cheney’s was one of a number of voices in George W. Bush’s inner circle claiming that Saddam Hussein posed a risk to the United States. The vice president worried about another catastrophic attack and exaggerated the very slender evidence of connections between Saddam’s intelligence organization and al Qaeda. On August 26, 2002, he went so far as to claim that the administration had firm proof that Saddam possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD): “The Iraqi regime has in fact been very busy enhancing its capabilities in the field of chemical and biological agents, and they continue to pursue the nuclear program they began so many years ago.” His words caught the president and others off guard. Still, they adopted Cheney’s alarmist view — not because they believed he was correct but because it suited their purposes as they sought to build public support for military action. Cheney did not lead Bush to war. The decision, and the responsibility, rested with the president.

Following the invasion, Cheney continued to make reckless statements and give poor advice. He claimed in June 2005 that the insurgency was in its “last throes,” even as the scale of violence continued to increase. Perhaps Cheney’s most damaging intervention occurred after Bush won reelection in 2004. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld offered to resign, but the vice president persuaded Bush to retain Rumsfeld lest his dismissal be seen as an expression of doubt about the course of the war. That kind of reassessment was exactly what the situation required. But, again, the final call was made by the president. He stubbornly refused to reexamine his war policy for three years as the violence in Iraq worsened. A different vice president might have urged another course of action, but there is no evidence that Bush would have listened. He ignored all other calls to rethink his approach, both from within the administration (by, for example, Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice) and from without.

In contrast to Cheney’s hawkish stance, at least two vice presidents have cautioned presidents against military intervention or escalation, and they were overruled. During the debates within the Johnson administration about whether to send U.S. troops to Vietnam in 1965, Hubert Humphrey joined George Ball, the undersecretary of state, and Clark Clifford, Johnson’s longtime confidant, in arguing against direct American military intervention. In July 1965 Clifford and Humphrey warned the president that the American people would never back the kind of war he proposed to fight. But their views represented a small minority within the administration. In the atmosphere of the Cold War and in view of Johnson’s conviction that “aggression” had to be resisted at the earliest opportunity (the lesson he derived from Munich), moreover, Humphrey’s objections carried little weight.

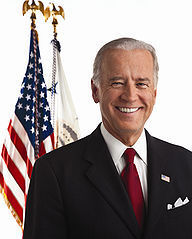

Joe Biden also adopted a dissenting stance during Barack Obama’s 2009 deliberations over an Afghanistan surge. Biden argued for an emphasis on counterterrorism, targeting al-Qaeda leaders in particular, while the military recommended sending enough troops (and keeping them there long enough) to mount a sustained counterinsurgency campaign. Obama insisted that Biden argue his case, but the vice president’s view was a minority position, much like Humphrey’s. On the other side stood Defense Secretary Robert Gates, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and the Joint Chiefs. The President chose a version of the surge option (albeit with fewer troops than the military preferred and for a shorter time).

Joe Biden also adopted a dissenting stance during Barack Obama’s 2009 deliberations over an Afghanistan surge. Biden argued for an emphasis on counterterrorism, targeting al-Qaeda leaders in particular, while the military recommended sending enough troops (and keeping them there long enough) to mount a sustained counterinsurgency campaign. Obama insisted that Biden argue his case, but the vice president’s view was a minority position, much like Humphrey’s. On the other side stood Defense Secretary Robert Gates, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and the Joint Chiefs. The President chose a version of the surge option (albeit with fewer troops than the military preferred and for a shorter time).

The record suggests that vice presidents may be heard, but presidents listen to a circle of advisers and then make the final decision. If a vice president takes a stand close to the president’s position, it may appear that the veep had a significant role. But it makes more sense, when we try to explain presidential war policy, to look at the president’s own predisposition and at the dominant view in his inner circle. Occasions when the number two carried the day are rare. Harry Truman put it correctly when he said of the presidency that “the buck stops here.”

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Official White House Photo of US Vice President Dick Cheney by Karen Ballard, 2001. Official White House Photo of US Vice President Joe Biden by Andrew Cutraro, 2009.

Are small farmers in developing countries stuck on stubble?

No-till agriculture, a resource conserving technology which increases the amount of organic matter in the soil, offers many benefits to farmers and society. Because farmers don’t plow their fields before planting, equipment, fuel, and labor costs are reduced. These reduced costs should appeal to cash-poor farmers in developing countries. Furthermore, no-till has been shown to increase and stabilize crop yields, conserve water in the soil and protect the crop from mild drought, prevent soil erosion, and mitigate climate change through carbon sequestration. Yet despite the benefits, small farmers in developing countries aren’t adopting no-till en masse.

The potential explanations for the lack of no-till adoption are numerous. There are the usual suspects: Poor farmers lack education and training, they generally resist change, they are highly risk-averse, or they lack access to the necessary equipment and extension services. Another major barrier to no-till adoption is that farmers can’t afford the stubble. When farmers produce cereal, they not only produce grain that is consumed by humans and livestock, but also produce residue byproducts. Straw is the portion of the residue that is baled and taken off the field after the harvest, and stubble is the portion left on the ground .

The potential explanations for the lack of no-till adoption are numerous. There are the usual suspects: Poor farmers lack education and training, they generally resist change, they are highly risk-averse, or they lack access to the necessary equipment and extension services. Another major barrier to no-till adoption is that farmers can’t afford the stubble. When farmers produce cereal, they not only produce grain that is consumed by humans and livestock, but also produce residue byproducts. Straw is the portion of the residue that is baled and taken off the field after the harvest, and stubble is the portion left on the ground .

No-till requires farmers to keep stubble on the field after each harvest, so that it adds organic matter to the soil. But farmers in developing countries usually raise livestock in addition to cultivating crops, and stubble is an important source of livestock feed. The need to use the stubble for feed is particularly strong for small and isolated farmers without good alternatives. Farmers therefore face a tradeoff between leaving stubble in the field for no-till or feeding it to their livestock. The question then becomes, how steep is this tradeoff between the benefits of no-till agriculture and the cost of feeding one’s livestock?

Doug Larson, Ed Taylor, and I set out to quantify this tradeoff to see if small farmers are indeed stuck on stubble when it comes to no-till adoption in Morocco. In Morocco, Rachid Mrabet and others have shown no-till to perform as well as conventional methods when rainfall is good, and better than conventional methods when rainfall is poor (which occurs regularly in this drought-prone country). However, no-till adoption is scarce among small farmers, who almost always also raise sheep, goats, and cows. Employing unique livestock data gathered from the same farmers during a good rainfall year and a bad one, we found the economic value of stubble to farmers to be around one quarter of the total value of cereal production in a good year. In a drought year, when grain production was lower and livestock feed scarce, the value of crop stubble accounted for three quarters of the total value of cereal production. In either case, the value of stubble as feed exceeded the upfront savings of no-till for most farmers.

There are many reasons why small farmers in developing countries tend to cultivate crops and raise livestock. Where infrastructure is poor, buying and selling livestock feed is costly, so it helps to be both a producer and consumer of feed. Diversification allows farmers to invest their earnings in livestock and manage risk when financial markets fail. Farmers can consume or sell off livestock after a poor harvest (although they are reluctant to do so). Diversification also helps farmers self-insure; in drought years, when alternative feed is scarce, farmers generate some feed even if the crop fails. Somewhat ironically, when the benefits of no-till stand to be highest (in times of drought) the costs of implementation are also much higher.

Because farmers vary in their demand for livestock feed, supply of stubble, and access to other feeds, their individual economic valuation of stubble also varies. We find that small farmers derived more value per hectare of crop stubble than large farmers. So did farmers who were better able to enforce property rights over crop stubble on their land and keep others from grazing their animals there.

On a larger scale we also see evidence of the how differences in the availability of feed influences no-till adoption. Diego Valbuena and colleagues found that in multiple sites across Africa and South Asia demand for crop residues is higher where grazing land is poorer. And generally, no-till adoption is more common among small farmers in South America — where more plant matter is available as feed — than elsewhere. Understanding which farmers place the highest value on stubble as feed will help better target extension, and better design policies that improve access to alternative feed sources. The high value of stubble as feed can pose a barrier to other technologies as well. For instance, some cereal varieties developed during the Green Revolution allocate more plant matter to grain and less to residue. High value crops like fruits and vegetables for export may fetch a higher price than cereal, but don’t always produce residues that can be used as feed. Certain machinery may even be rejected because it renders residue unusable as feed, as was the case with a Brazilian peanut harvester brought to Senegal.

No-till and other technologies could still be profitable to small farmers in the long run, and can certainly be beneficial to society considering the environmental impacts. However, small farmers in developing countries often discount long-term benefits when compared with short term needs, such as livestock feed. Efforts to disseminate no-till and other technologies to small farmers in developing countries should therefore focus on identifying and alleviating the constraints that result in crop stubble being so valuable as feed to these farmers. Otherwise the cost of no-till adoption of no-till technology may simply be too high.

Nicholas Magnan recently joined the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Georgia, Athens. He was a research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute in Washington, DC studying various aspects of agricultural technology adoption. He is the co-author of “Stuck on Stubble? The Non-market Value of Agricultural Byproducts for Diversified Farmers in Morocco” in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, which is available to read for a limited time. It examines the value of agricultural byproducts, such as crop stubble, to crop-livestock farmers who produce both cereal and crop residue, where the latter can be used as livestock feed. To properly assess the cost of introducing new technologies into such systems, one must value the implicit cost of byproducts.

The American Journal of Agricultural Economics provides a forum for creative and scholarly work on the economics of agriculture and food, natural resources and the environment, and rural and community development throughout the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Farmer crouched down picking wheat in his field. Photo by ilaskey, iStockphoto.

Excelling Under Pressure

The Olympics are in full swing, and we’re bound to witness some athletes who triumph and others who choke under the stress of performing. What differentiates those two groups?

I’ve been probing that question for decades from the perspective of a musician and educator. Through my research and experience, I’ve come to appreciate that, for athletes and musicians alike, the primary distinction between those who excel under pressure and those who crack lies in how they prepare to perform.

As an illustration, before we look at athletes, let’s juxtapose two pianists:

Pianist 1 performs a solo and feels his heart rate accelerate and his hands start to quiver. Unnerved by the odd sensations, he fumbles a couple of passages. Then, in an attempt to reclaim the relaxed groove he prizes, he imagines that he’s playing on a tropical beach, but that only distracts him further, provoking several memory slips. He exits the stage bewildered because he played flawlessly in the practice room.

Pianist 2 plays a comparable piece and experiences similar adrenaline-fueled jitters. In response, she breathes deeply, releases her shoulders, and focuses on expressing each phrase. Her hands remain cool, but her execution is secure and she projects the joy in the music. As the closing chord sounds, her audience erupts in applause.

Pianist 1 underperformed because, in practice, he would play his piece over and over until it “just came out.” Problem is, such automated learning requires automated recall, which readily breaks down under stress. As his hands became unsteady, he groped for control but there weren’t any guideposts for his mind to latch onto because he ingrained his piece mindlessly.

Pianist 2 encountered parallel sensations but directed herself in tactical ways. Furthermore, when she practiced her piece, she absorbed its structure in detail, allowing her to track her place in the musical landscape. Her memory and performance skills were assured, so she could devote herself to making art.

What distinguishes mindful performers, like Pianist 2, is that they operate from a place of awareness and never run on autopilot. That’s not to say that they over-think. Instead, they rely on what psychologist Ellen Langer terms “soft vigilance” (The Power of Mindful Learning, p. 43-44).

In practice, they take in their material from multiple perspectives, and then they do mock performances, applying maneuvers that boost creativity and quell nervousness. On stage, their mindful habits enable them to trust in their preparation, provided that their preparation is truly thorough.

Thorough performance preparation spans three categories codified by Glenn Wilson in Psychology for Performing Artists: person, task, and situation (p. 211). Here are some quick examples:

Person: Mindful performers learn to regulate their emotions. They monitor their inner states and rally themselves into practice or performance mode.

Task: They attain the inclusive skills needed to execute securely in high-stakes conditions. On good days, they perform easily but maintain filaments of awareness connecting everything they do. On tougher days, they exert more effort, expanding those filaments into high-bandwidth channels to bring things under control.

Situation: They rehearse dealing with diverse performance settings so that they can focus regardless of the circumstances.

I don’t mean to oversimplify; deep-seated personal issues can impede performers in insidious ways. But when it comes to high-stakes performance, mindfulness is indispensable. In Langer’s words, “Learning the basics in a rote, unthinking manner almost ensures mediocrity” (p. 14).

Now, let’s hear from an athlete. In a July 27 multimedia post on the New York Times website, US Olympic swimmer Dana Vollmer contrasted her approach to the butterfly stroke with that of less-accomplished swimmers:

“People pull on the water with all their might or they really kick down with their legs and they’re thinking that that is what makes you go fast. It’s much more about feeling the flows off of your body that make you go fast.”

Mindless swimmers pull “with all their might,” but Vollmer, a mindful athlete, feels herself flow through the water. She notices. She responds.

Mindful performers also stay open to discovering new things, which feeds their drive to practice. Here again is Vollmer on swimming the butterfly (on July 29 she won gold in the 100 meter competition, setting a new world record):

“I feel like I learn something new about myself and about swimming and just about life in general every time I do it.”

Vollmer epitomizes the fascination with craft that motivates athletes and musicians to work. And when they work mindfully, regardless of whether they win medals, performers go forward knowing that they’re doing their best.

Gerald Klickstein (@klickstein) is author of The Musician’s Way: A Guide to Practice, Performance, and Wellness (Oxford 2009) and posts regularly on The Musician’s Way Blog. Director of the Music Entrepreneurship and Career Center at the Peabody Conservatory, he previously served for 20 years on the faculty of the University of North Carolina School of the Arts. His prior contribution to the OUP blog is titled “The Peak-Performance Myth.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

August 6, 2012

Public pensions’ unrealistic rate of return assumptions

By Edward Zelinsky

Ten years ago, the financial problems of public employee pensions concerned only specialists in the field. Today, the underfunding of public retirement plans is widely understood to be a major problem of the American polity. Underfinanced public pensions threaten the ability of the states and their localities to provide basic public services while paying the retirement benefits promised to state employees.

Most public pensions mask their underfunding by assuming unrealistically high rates of return for pension assets. The longer the underfunding of state retirement plans is ignored in this fashion, the more difficult will be the ultimate adjustments required of state employees and taxpayers.

When public pensions earn less than the rates of return they assume, taxpayers must pay more to provide public employees their promised retirement benefits, or such benefits must be curbed to reflect reduced funding — or some combination of taxpayer financing and benefit curtailment must bring pension obligations into line with lower pension assets. Elected officials often prefer to perpetuate unrealistic rate of return assumptions rather than confront these painful choices.

To take one prominent example, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) is the Golden State’s main pension plan for state and local employees. By some measures, CalPERS is the nation’s largest pension plan for public employees. In March of this year, the board of CalPERS purported to confront economic reality by reducing CalPERS’ assumed rate of return on its investments by .25%. Specifically, the CalPERS’ board reduced the plan’s assumed rate of return from 7.75% to 7.5%.

We live in a time when stock markets are performing erratically and short-term interest rates are effectively zero. Nevertheless, California’s pension plan unrealistically claims that its assets will earn an average annual return of 7.5%.

We live in a time when stock markets are performing erratically and short-term interest rates are effectively zero. Nevertheless, California’s pension plan unrealistically claims that its assets will earn an average annual return of 7.5%.

The troubling nature of this assumption recently became apparent when CalPERS reported that it actually earned only 1% over the preceding 12 months. Despite this dismal performance, CalPERS still asserts that it will earn 7.5% on the investment of its pension assets.

CalPERS’ defenders can note that the annual investment return of 7.5% is a long-term assumption and that CalPERS’ dismal investment performance this year was balanced by better investment returns in earlier years. Neither of these defenses is comforting.

We are likely to be in a low-interest rate environment for the indefinite future. Although interest rates will increase at some point in the future, it is unlikely that they will bounce back any time soon to the levels postulated by CalPERS. Public pension plans like CalPERS ignore this reality by assuming investment returns of 7.5%.

The problem of unrealistically high rate of return assumptions is not limited to the Golden State’s pension for its public employees. The problem is ubiquitous throughout the nation.

For example, the Maryland State Retirement and Pension System has just announced that its investment returns for the twelve months ending on June 30th was even worse than CalPERS’ performance. The Maryland pension plan earned just 0.36% on its assets, even as it promises annual investment returns of 7.75%.

A distinguished task force chaired by Paul Volcker and Richard Ravitch has recently highlighted the seriously unfunded condition of public pensions nationwide. This systemic underfunding, the Volcker-Ravitch task force concludes, is hidden by unrealistically high assumptions about public pensions’ rates of return: “The most significant reason for pension underfunding is that investment earnings have fallen far short of previous assumptions.”

Even using public pensions’ overly-optimistic return assumptions, the Volcker-Ravitch task force tells us, such pensions are unfunded nationwide in the amount of one trillion dollars. Bad enough. Using more prudent, i.e., lower, assumptions about expected rates of return, the nationwide underfunding of public pensions may be as large as three trillion dollars.

The implications of these numbers are sobering. Tax money must be diverted from vital public services such as police, fire, and education to finance pensions promised to public employees but not properly funded.

The problem of underfunded public pensions cannot be solved until it is acknowledged. Unrealistically high rate of return assumptions, like those embraced by CalPERS and other public retirement plans, mask the magnitude of the underfunding of public pensions. The refusal to confront the problem of pension underfunding may help state officials to get re-elected by kicking the proverbial can past the next election, but the problem cannot be ignored indefinitely. The longer the problem of underfunded state pensions is ignored, the more difficult will be the ultimate adjustments required of state taxpayers and state employees.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Pension pension or retirement concept with word on business office folder index. Photo by gunnar3000, iStockphoto.

Funding and Favors at the Olympics

Public funding for sports events was a fact of life for the Greeks and Romans. So was private funding, and both the Greeks and the Romans knew what the benefits and what the pitfalls associated with either might be. Can we be certain that the organizers of the London Olympics are quite so clear about this?

The widely advertised donation (amounting to thirty-one million dollars) by pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) of testing facilities for 6,250 blood samples taken from athletes (testing for 62% of contests, up from 45% at Beijing) could raise that question. The Olympic Committee, while a private organization, works hundreds of governments that provide public funds for Olympic sports and must regulate GSK’s products. The fact that GSK has recently offered to pay a three billion dollars settlement to one of three governments that doesn’t provide public funds to its Olympic athletes (that of the United States) for deceptive advertising might make people wonder about the definition of “drug cheat” at these games.

The Ancient Greeks, by and large, tended towards the use of public funds for major athletic events. Even before they developed the western world’s first system of coinage, they were aware of the impact of wealth on public decision-making. The first reference to bribery occurs in one of the earliest Greek poems, and one of the earliest surviving documents from the ancient Olympic games indicates deep concern about shady financial transactions on the part of the bigwigs who were in attendance.

The city of Elis, in whose territory Olympia was located, paid for the administration of the games (a colossal pain in the neck then as now). Elis appointed a board of officials every four years to make sure everything worked. The board advertised the games, appointed the officials, oversaw the training of the athletes before the opening ceremonies to make sure that the competitors were legitimate, and made sure that the facilities were in decent shape. Since venues like stadium were only used every four years, there was always a lot of deferred maintenance. We have a fascinating document, albeit connected with another major festival, detailing payments an organizing committee was making to local contractors to do things like clean trash out of the venues, provide the best surfaces, and so forth.

Big spenders from elsewhere were always welcome. In time, some of them did build splendidly self-commemorative structures at the site of the games, but those buildings were never central to the games themselves. They tended instead to cater to the needs of fans who were by and large drawn from the class of people who could afford to take a few weeks off work to go to the games. Elis never sold naming rights to the stadium and made it clear that the rich and powerful, even if sponsoring athletes (often the case) weren’t connected with the way the games ran.

The Romans took the opposite approach. Quick to recognize the political benefits of a good show, Roman politicians moved away from a publically-funded model of entertainment, which existed for hundred of years in conjunction with chariot racing, to a private model at about the same time that Rome became the dominant power in the Mediterranean World (the end of the third century BC). From then on the rise in privately funded spectacles tracks very closely the transformation of Rome from democracy to autocracy.

The corrosive effect of private funding model becomes immediately clear when we see a staunch defender of the traditional political system (Marcus Cicero) in the business of hiring out gladiators to other politicians and receiving extensive correspondence from a friend about the importance of providing some panthers for games that he will put on. If only Cicero, then governor of a province where the desired beasts resided, would hurry up and catch a few! Cicero himself noted that the massive spectacle put on by one of Rome’s aspiring autocrats failed because the events were either too familiar, or, in the case of the slaughter of some elephants, too distressing. The man who ultimately brought the Roman democracy crashing down, Cicero’s contemporary Julius Caesar, was a major gladiatorial contractor who made many friends by helping people fund things that they couldn’t afford. There may perhaps be no more powerful statement of the linkage personal funding of sports events and non-democratic government than one of Rome’s most important monuments. The building we know as the Colosseum was actually built as “The Flavian Amphitheater,” named for the family of the emperor who paid for it with the money he took from the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD.

The Olympic movement provides amazing spectacles, drawing the world together just as the ancient games once did. It gives athletes the chance to excel on a unique stage and us a chance to watch astonishing achievements in awe. At the same time we need to be conscious, as the original founders of the games were, of where the money comes from and just what is being bought.

David Potter is Francis W. Kelsey Collegiate Professor of Greek and Roman History and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of Greek and Latin in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan. He is the author of The Victor’s Crown: A History of Ancient Sport from Homer to Byzantium, Ancient Rome: A New History and Emperors of Rome, and two forthcoming OUP titles, Constantine the Emperor and Theodora. Read his previous blog posts: “The Ties That Bind Ancient and Modern Sports,” “The Money Games,” and “Sports fanaticism: Present and past.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Making prisoners work: from hulks to helping victims

In July 2012, two prisoners lost their application for judicial review of two Prison Service Instructions that implement the Prisoners’ Earnings Act 1996. This Act demands that a deduction of up to 40% from the wages of prisoners in open prisons is imposed. In response to the prisoners’ argument for discretion to be applied to each individual’s circumstances, Mr Justice Sales said that deductions are justified:

“They have been promulgated in order to promote a legitimate public policy objective (that prisoners should make a contribution to support victims of crime) and they are formulated in a way which is proportionate to that objective. There is a strong interest in keeping the rules simple and clear, so as to keep the costs of administering them within reasonable bounds.”

This case — which in effect upholds the policy of the Coalition Government to use opportunities for (more) work in prisons as both rehabilitation and reparation — may seem a far cry from the cover image of the third edition of Sentencing and Punishment: The Quest for Justice. However, we chose this cover, which reproduces a painting of a prison hulk and prisoners at work moving timber in Woolwich in 1777, to highlight the current issue of provision of constructive activities for prisoners. It also reflects upon the problem, critical at the end of the eighteenth century and now, of dealing with overcrowding.

Cover of Sentencing and 'Punishment: The Quest for Justice'

Further, the jacket image has a personal resonance. A Woolwich hulk ‘housed’ a convict named Isaac from 1800 to 1804 and we’ve discovered that he was probably married to one of our great-great-great-great grandmothers. Isaac was sentenced to transportation by Derby Quarter Sessions for ‘obtaining money etc, at the head of a mob’ (Derby Mercury, 1800).

So why were convicts in hulks on the Thames in 1777 and 1800? Prison hulks have a long history in Britain, being used to deal with prison overcrowding. The 1718 Transportation Act enabled courts to order transportation as punishment. However, the outbreak of the war with America in 1776 meant that convicts could no longer be transported to North America. In that year, their punishment was to be hard labour — not rehabilitative work — on a hulk. While a new destination for transportees was considered (eventually Australia), pressure for reform and the building of new prisons intensified, especially after the Gordon Riots in 1780 led to the destruction of several London prisons. The Penitentiary Act was passed in 1779 and a new Transportation Act in 1784 was enacted after the end of the American War.

The first prison ship in England was moored at Woolwich and the ship depicted on the book cover is probably the Justitia. It was followed by a long line of ships including the Censor, the Ganymede and decommissioned naval ships including HMS Warrior and HMS Temeraire. Hulks were also used in Portsmouth and Plymouth. The Act of Parliament in 1776, which authorised their use, intended them as a temporary measure to be adopted for two years, but in fact they remained in use until 1857, and then reappeared 140 years later in 1997. HMP Weare was moored off Portland but closed in 2005.

Private companies ran the original hulks, were paid a fee by the state for their services, and fell under the purview of the justices of the peace. They provide an early illustration of the operation of the penal system as a commercial enterprise. The Justitia was owned and run by Duncan Campbell, a leading penal entrepreneur, also involved in the penal transportation industry, and an uncle-in-law of Captain Bligh. The inmates included young boys as well as elderly inhabitants, and occasionally women were also held on the hulks. Many of the inmates were sentenced for very minor thefts.

Conditions on board the hulks were harsh and squalid. Some prisoners were held for the duration of their sentence or while awaiting transportation, but others didn’t survive their incarceration or the outbreaks of disease on board. However, in some respects they were more humane than subsequent early Victorian prisons. As the picture illustrates, prisoners benefited from working with others, in the open air, in contrast to the psychological deprivation of the silent prisons of the early nineteenth century, or indeed the conditions found in modern supermax prisons in the United States and elsewhere. The Thames was a favoured site for prison labour as it provided work opportunities such as dredging the river and driving in posts to prevent erosion of the riverbank. Prison labour was also used to develop Woolwich Arsenal and to maintain the hulks themselves.

While prisoners suffered the stigmatisation of carrying out their work under the scrutiny of the public, the visibility of the hulk and its inmates highlighted to the public the problems of imprisonment, with the conditions on board attracting criticism and accelerating demands for reform and the resumption of transportation. Critics also highlighted the high running costs of the hulks and the fact that their use appeared to have no noticeable effect on crime rates.

To return to Isaac (the convict sentenced in 1800), he was also sent to a hulk at Woolwich because he could not be shipped straight away to a foreign land. The reason didn’t lie in Australia or North America but, rather, in the lack of available sea-worthy ships in England. The ships were all away blockading ports and fighting Napoleon’s navy. Isaac started his ‘imprisonment’ on Stanislaus and was moved to Retribution in 1803 before he was pardoned in May 1804 to serve in the army. Whether Isaac survived to fight Napoleon — certainly not a soft option — and what happened to him next is as yet unknown.

Susan Easton and Christine Piper are the authors of Sentencing and Punishment: The Quest for Justice. Susan Easton is Reader in Law at Brunel Law School. She has a particular research interest in prisoners’ rights and the experience of imprisonment. Christine Piper is Professor of Law at Brunel Law School. Her current research interests include issues in youth justice and the impact of punishment on families.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image: cover of Sentencing and Punishment: The Quest for Justice: Third Edition, Oxford University Press (2012)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers