Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1038

July 28, 2012

Olympic confusion in North and South Korea flag mix-up

Do North and South Korea belong to the same country? Are they the same race sharing the same history and language? The answers to these questions are far from clear even to the Koreans themselves. It depends on the day really or the Olympics. In the 2000, 2004, and 2006 Olympics the two countries joined together at the games’ opening ceremonies and marched in matching uniforms behind the Korean Unification Flag.

Not surprisingly it was easy for Scottish officials to put up the South Korean flag when North Korea’s women’s team played a match against Columbia at Hampden Park in Glasgow. The team refused to play until their flag with the red star was replaced on stadium screens. On Thursday, North Korea’s Olympic team accepted repeated apologies, including one from Prime Minister David Cameron.

Even so everyone has continued calling the country North Korea, even though the country should be referred to as the Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea (DPRK) while South Korea is the Republic of Korea (ROK). In reality the DPRK does not officially recognize the ROK’s existence as a separate country but regards it as part of the DPRK under American control. The South Korean government is therefore a puppet regime and an enemy of Pyongyang which should be destroyed if necessary by an attack.

The North Koreans don’t in fact believe they are still the same people. The founder of the DPRK, Kim Il Sung, is believed to have created a new nation, loyal to him and his family. Every effort has been made since 1946 to create a separate history and culture which has little in common with either pre-1946 or the culture of the South. The North Koreans don’t even use the vocabulary or write with the same alphabet. If they are ever unified under the rule of the Kim family, the South Koreans would be forced to undergo a complete brainwashing and learn to become obedient subjects of the Kim dynasty.

During the heyday of constructive engagement under two South Koreans left-wing presidents, relations between the two halves were relatively friendly. After Kim Dae-jung introduced his ‘Sunshine Policy’ in 1998, Pyongyang allowed the two teams to march together. Ten years later the South Korean electorate, wearied by a policy which delivered too few gains, elected President Lee Myung-Bak in February 2008. Bilateral relations worsened and the North made a series of military attacks and has continued to threaten to turn Seoul into a sea of fire.

At the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the two countries refused to march together, a move International Olympic Committee President Jacques Rogge called a “setback for peace.” There were no talks of marching together in 2012 either. But this is where the story gets interesting.

Kim Il Sung’s Swiss-educated grandson, Kim Jong Un, is now in power and has just ousted the military chief Vice Marshal Ri Yong-ho. Many are now hoping that the 28-year old leader, who has been showing himself in public with his new wife, is going to abandon the military first policies of his father. Surely by now, he must realize that Pyongyang will have to change if the Kim dynasty is to survive as more than a tool of Chinese foreign policy.

The fact that it was so easy for the Olympic host nation to put up the wrong flag it will be another reminder of how few friends the North Koreans now have. The country is only being kept afloat with Chinese money. As one commentator in the Daily Telegraph wrote, they team might as well be walking behind the Chinese flag. A series of recent diplomatic blunders such as the attempted missile launch earlier this year, in defiance of the whole international community including China, has only deepened its isolation. Sooner, rather than later, Pyongyang will have to start rebuilding its ties with Seoul, Tokyo and Washington. But many in the Korean Peninsula are hoping that Kim Jung Un will be willing to start a whole new game.

Jasper Becker, an award-winning author, has worked as a foreign correspondent for twenty-five years, including fifteen years based in Beijing. He is author of Rogue Regime: Kim Jong Il and the Looming Threat of North Korea, Hungry Ghosts, The Chinese, and City of Heavenly Tranquility: Beijing in the History of China. An expert on East Asian history and politics, Becker’s work has been featured in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, New Republic, The London Review of Books, National Geographic, and Time Asia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

July 27, 2012

How to Teach a Successful Medical Class

Recently the second year-medical students (Class of 2014) at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine honored me with the L.D.H. Wood Pre-Clinical Teaching Award. This occasion prompted me to reflect on what made the Medical Neurobiology class that I taught in the fall of 2011 so successful. I believe that the following were key to the class’s success:

Give every lecture yourself. Reducing the number of instructors (particularly to one) is a sure-fire way to increase continuity, decrease redundancy, and generally improve the reception of any course. My single-authored textbook written specifically for medical students, Medical Neurobiology, was published by OUP in May 2011. I wanted to figure out if the book ‘worked,’ so I needed to teach the whole course.

Make certain students always know where they are and where they are going. My lectures went in the same order as the chapters of the book and virtually everything in my lectures was in the book. This allowed students to listen and try to understand in real time rather than focus on taking notes.

Make certain students always know where they are and where they are going. My lectures went in the same order as the chapters of the book and virtually everything in my lectures was in the book. This allowed students to listen and try to understand in real time rather than focus on taking notes.

Address clinical issues at the first moment students could possibly understand a disease, disorder, or therapeutic approach. I opened the class with a discussion of locked-in syndrome and closed it with a comparison between locked-in syndrome and global amnesia, touching on several clinical issues in every class in between.

Focus on topics that any physician, regardless of specialty, needs to learn and remember in 25 years. Hammer home important points repeatedly. At least some of the students felt prepared enough for the midterm that they spent the preceding days studying for their other class’s midterm to be held several days later.

Explain everything simply. Anything, even very complex topics, can be explained simply. Peppering my lectures with metaphors, I wanted the material to make sense to the students, obviating the need for memorization beyond the bare minimum (viz. vocabulary).

Emphasize links between neurobiology and diseases that are not under the traditional purview of neurology. Building on lecture examples, students were asked to try their own hand at it in an extra credit assignment. The resulting essays discussing how neurobiology relates to internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, geriatrics, oncology, rehabilitation medicine, and so on were gratifying.

Quiz the students early and often. The class was intense, covering all of neurobiology in six short weeks. As I planned for the course, I worried a great deal about the potential for students to fall behind. Every laboratory was followed immediately by a short practical quiz. Every week there was a quiz on the lecture material. Consequently students were tested 2-3 times each week. Whether because of these draconian measures or just because the students were outstanding, I don’t know, but no one in the class fell behind. And everyone passed with plenty of room to spare.

Get students to ask questions. Students asked many questions, every class, and these were great questions — not a single one was of the “will this be on the test?” variety. Questions of clarification allowed me to know when I was losing some portion of the students so that I could find another way to convey the material. Questions of interest revealed the personalities of the students, which in turn rendered the class more personal and actually, quite fun.

Make the class as good for you as it is for the students. As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi argues in Flow (Harper & Row Publishers, 1990), optimal experience is not just about being successful; optimal experience also requires accomplishing something that is difficult. The students learned a ton — enough to render the neurology portion of their Clinical Pathophysiology and Therapeutics class simply a matter of conceptual review (plus a bit more vocabulary). The fact that the students succeeded paired with the challenging material is what made this class satisfying for the students. The class was just as satisfying for me because not only did I find out that my book ‘worked’ (which was gratifying) but I successfully communicated a great deal of material in a short time.

In the end, my experience tells me that teaching is about far more than a transfer of knowledge. Such a transfer can be accomplished by reading a book or even an internet site. However, when a teacher and students occupy the same physical space, something mysterious, magical and wonderful can happen: communication and learning! The students will learn readily if they feel like the teacher is a full partner. Students respond to energy with energy. And teachers are in turn energized by engaged students. In the fall of 2011, the students and I were mutually and actively engaged in a collective effort. They worked hard. I worked hard. It paid off. And we had fun. The outstanding students, the Pritzker class of 2014, were my invaluable partners and I treasure my experience with them.

Peggy Mason was educated at Harvard (BA ’83, PhD ’87) and did postdoctoral work at the University of California-San Francisco. Since 1992, she has been on the faculty of the University of Chicago and has taught neurobiology to medical students. She is now Professor of Neurobiology and the author of Medical Neurobiology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Multiracial medical students wearing lab coats studying in classroom. Photo by goldenKB, iStockphoto.

British Olympic lives

The London Games have unsurprisingly stimulated renewed interest in Britain’s Olympic heritage. The National Archives has made available online records of the modern Olympic and Paralympic Games. Chariots of Fire (1981), the film which tells the story of the sprint gold medals won in Paris in 1924 by Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell, has been re-released. English Heritage commemorative blue plaques have recently been unveiled in London at the homes of Abrahams and his coach Sam Mussabini. Historians meanwhile have been uncovering the roots of Olympianism in Britain, and tracing its relationship to national sporting traditions.

The challenge for the latest update to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford DNB) has been both to tap into this scholarship and to extend it. Of course, the best-known figures already have entries: Robert Dover, the Gloucestershire lawyer who organized the Cotswold Olimpick Games in the early seventeenth century, is currently in a special feature on the history of the Olympics; and the life story of William Penny Brookes, a Shropshire medical practitioner who founded the Wenlock Olympian Games in the mid-nineteenth century, is available as an episode on the Oxford DNB’s free podcast. A new addition to the dictionary, however, is Robert Laffan, a schoolmaster and clergyman, whose advocacy of a moral dimension to sporting competition impressed the founder of the modern Olympic movement Pierre de Coubertin.

Another embodiment of Olympianism is the RAF officer Don Finlay, whose significance is established by Tony Mason, author of a recent study of Sport and the Military. Never a gold medallist, and therefore not accounted among the all-time greats, Finlay began his long and eventful Olympic career with a hurdling bronze at Los Angeles in 1932, having originally been placed fourth. Experimental use of high-speed cameras revealed that he had in fact crossed the line third, and after the medal ceremony the American who had been awarded bronze sportingly handed over their medal to him. As captain of the British athletics team in Berlin in 1936 he took part in the ‘eyes right’ gesture adopted by the British during the parade at the opening ceremony as an alternative to the Nazi salute, and he went on to take silver in the men’s hurdles. Then, after combat as a Spitfire ace in World War II, he took the Olympic Oath on behalf of the competitors at the London Games in 1948 only to stumble and fall in sight of the finishing tape in the qualifying heat of his own event.

‘Firsts’ are represented by Leicestershire textile worker and swimmer Jennie Fletcher, whose bronze in the 100 metres freestyle at Stockholm in 1912 (the first Olympiad where women’s swimming was part of the programme) was the first individual women’s swimming medal by a British competitor. She was also a gold medallist in the British 4×100 metre freestyle relay team, two of whose legs were swum by women from Scotland and Wales — a precursor, as sports historian Jean Williams points out, to the modern concept of Team GB. Jack London, born in British Guiana but resident for most of his life in the UK, foreshadowed another trend. Like Don Finlay, London never achieved gold, but his silver in the 100 metres in Amsterdam in 1928 — described by Martin Polley, author of the English Heritage book The British Olympics — made him the first black British medallist.

As research progressed, another significant and paradoxical story emerged: those sportspeople who didn’t or couldn’t take part in the Olympic Games. In a recent blog post, incoming general editor of the American National Biography, Susan Ware has observed that sporting biographies can reveal national complexity and diversity. This is well illustrated by those excluded from the Olympic movement on account of their gender. Pioneers of women’s sport have emerged as perhaps the most striking group of subjects to have been brought to light by research for the Oxford DNB’s latest update.

British competitors at the Women’s World Games of 1922, prior to the inclusion of women’s athletics in the Los Angeles Olympics (1932). Source: Mirrorpix .

With a governing body dating from 1896, women’s hockey was a major success story in English sport, yet it was not included in the Olympic programme until 1980. Men’s hockey had found a place in 1908. Instead, an ambitious programme of international competition was promoted by the administrators of women’s hockey, notably Edith Thompson, whose life reveals an imperial dimension to her sporting activity.

Calls for the inclusion of women’s athletics into the Olympic programme were rebuffed and alternative games were held between 1921 and 1934, variously named the Women’s Olympiad, Women’s Olympic Games, and Women’s World Games. In a collective entry on the first generation of women in Britain to participate in official organized athletic events, Mel Watman, the historian of the Women’s Athletic Association, recovers their track and field records, and their lives — many of which ended in obscurity, their fame in the 1920s largely forgotten by the time of their deaths in the late twentieth century. They include the team of five women sprinters who set out from London in 1932 to represent Great Britain at the Los Angeles Games, where they took bronze in the relay.

Even more of an outsider, and an exemplar of what Philip Carter has described as the type of ‘unknown’ life, was the woman marathon runner, Violet Piercy. Her long-distance runs, undertaken decades before the women’s marathon was admitted to the Olympic programme (1984), have regularly been cited in histories of distance running, while she herself remains highly visible on newsreel archive sites. But who was she, and how authentic were her runs? The most fully documented account of her life and career has been compiled for the update by crime writer and athletics historian Peter Lovesey. It reveals both the substantial nature of her achievement and yet the continuing mystery of much of her life, largely spent in the urban anonymity of South London. She was not herself an Olympian, but she blazed a trail a solitary trail for those who were.

Mark Curthoys is research editor at the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. To mark the London Olympics, the Oxford DNB has a special feature highlighting 22 historical British Olympians from the Athens Games of 1896 to Mexico City in 1968.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of men and women who have shaped British history and culture, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Dictionary offers concise, up-to-date biographies written by named, specialist authors. It is overseen by academic editors at Oxford University, UK, and published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Where penguins live, and other reasons why the Antarctic is not the Arctic

The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction

By Klaus Dodds

Let’s start with some salient facts:

Fact 1: The Antarctic is not the Arctic, no matter how often toy makers and television programming routinely confuses the geographical distribution of polar bears and penguins. Penguins are to be found in Antarctica.

Fact 2: The Antarctic is comprised of a large polar continent surrounded by ocean. The Arctic is an ocean surrounded by continents and islands.

Fact 3: The Antarctic is colder, drier, windier and higher than the Arctic.

Fact 4: The Antarctic does not have an indigenous human population.

Fact 5: The Antarctic is remote and far removed from centers of population.

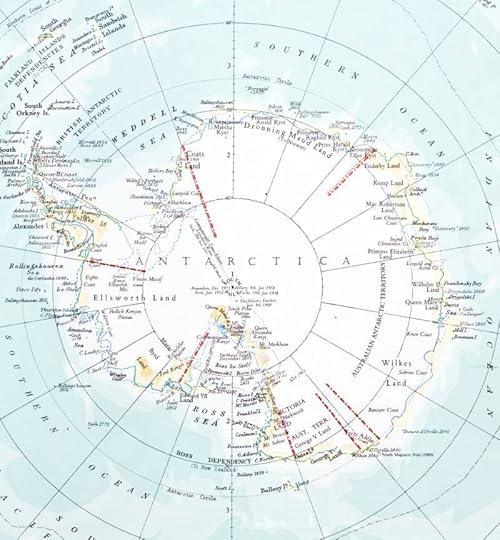

But why does the Antarctic matter? And why should we take an interest in this apparently distant, remote and unpopulated space? Does the Antarctic hold vast and largely untapped resources? Will countries and other stakeholders ever go to war over their ‘rights’ to territory and resources? It might sound mad but the Antarctic is caught up in the politics of nationalism and national pride. You only have to look at a map of the Antarctic and read the place names.

These kinds of questions were routinely posed in the 1940s and 1950s when it was unclear as to what kind of future faced the Antarctic. At that stage there were seven countries (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the UK) that believed that they enjoyed sovereign rights in the Antarctic. Unfortunately for this particular G7, the United States and the Soviet Union rejected those claims and reserved the right to make their claim to the vast and poorly mapped polar continent.

These kinds of questions were routinely posed in the 1940s and 1950s when it was unclear as to what kind of future faced the Antarctic. At that stage there were seven countries (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the UK) that believed that they enjoyed sovereign rights in the Antarctic. Unfortunately for this particular G7, the United States and the Soviet Union rejected those claims and reserved the right to make their claim to the vast and poorly mapped polar continent.

As the Cold War gripped the Arctic region, there was a strong likelihood that superpower competition might migrate southwards. And it did. In the form of science and scientific endeavor rather than military posturing and war gaming. Science, by the International Geophysical Year (1957-1959), was the mechanism by which rivalries flourished. Fearing the worst 12 countries agreed upon an Antarctic Treaty to help regulate behavior.

Over the next five decades, interest in the Antarctic has grown steadily inspired by scientific, resource and strategic drivers. Science remains the dominant activity and a growing number of nations invest in national and multi-national programs designed to better understand below and above the surface of the polar continent. Resource exploitation, especially via fishing and controversially whaling, is pivotal in shaping the management of the Southern Ocean. Strategically, despite efforts to ensure that territorial claims do not become a subject of dispute, all the claimant states including the UK behave as if they enjoy a sovereign presence in the Antarctic.

The manner in which the Antarctic is managed is controversial. For non-governmental organizations, there remain complaints that the dominant powers are not regulating sufficiently well fishing and a growing tourism sector. Commercialization is blamed for corrupting the scientific ethos of the Antarctic Treaty. Rising powers such as India and China are now more visible on the ice and within the corridors of polar power. Their presence routinely cited for unsettling established Antarctic powers such as Australia, which maintains a vast claim to the Antarctic. India and China have understood the ‘rules of the game’ and built research stations and undertaken scientific firsts such as establishing bases in more remote places of the polar continent.

This tendency to emphasize the idea of performance reminds us that the Antarctic has been a very gendered place. This was a space, ever since the Edwardian era, for men to test themselves against nature. Scott and his party may have died on their return from the South Pole in 1912 but they did so heroically. Women were nowhere to be found. Or if they were present then it was more likely to located on a map. The exploration and scientific study of the Antarctic was largely a man’s world. This has now changed but that gendered legacy remains. The Antarctic continues to attract men eager to show off their equipment and study, exploit and play.

Should we worry about the Antarctic? One enormous cultural shift has occurred in the manner in which we engage with this region. In the nineteenth century, it was common to read stories about how the polar realm inspired awe and fear. The ice was to be feared, and there has been no shortage of explorers and novelists ready to sustain such an unsettling vision of place. But now it is the ice that should be scared of us. Ice, snow, and the cold are the new frontline of human anxiety pertaining to a changing world.

Increasingly scientists and policy-makers speak of the Antarctic as no longer remote in any sense. The Antarctic is connected to planet Earth, and contemporary research recognizes that so much of the world’s climate is tied to the southern continent and surrounding Southern Ocean. And vice versa. What remains to be understood is how rising temperatures, and the rise is not uniform across the Antarctic, is having varied consequences for ice cap stability and biodiversity.

What to do? The governance of the Antarctic is so much more complicated than it once was in the 1950s. In the late 1950s, the Antarctic Treaty stood largely untroubled by other kinds of international legal entanglements. This is no longer the case. The Antarctic is ensnared in a complex mix of legal regimes involving terrestrial and marine environments. The Antarctic is no longer exceptional in that regard, and that troubles claimant states and even non-claimants such as the United States.

The good news is that all the parties working in the Antarctic accept that there should be no mineral exploitation. This ban is in place for at least three decades. There is no evidence that mining is coming any time soon. The Arctic is on the front line in that regard.

The bad news is two fold. Scientists worry that the Antarctic ice sheet is being destabilized by ongoing climate change. This will have consequences for the region and the wider world. And political co-operation might be undermined if states and other stakeholders continue to make money from Antarctic related activities. No one agrees on the question “Who owns the Antarctic?” And that will remain the case for this century.

Klaus Dodds is Professor of Geopolitics at Royal Holloway, University of London. He is author of a number of books including Geopolitics: A Very Short Introduction (2007) and The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction (2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Adelie penguin on Paulet Island, Antarctica. Photo by nailzchap, iStockphoto.

Antarctica map. Photo by 1905HKN, iStockphoto.

July 26, 2012

Dispelling the myths of emancipation

The story of the Civil War has never been simple: from slavery to states rights, liberation to sharecropping, the loss of life on the battlefield with bullet wounds to in the camps with illness. As new scholarship for the sesquicentennial emerges, many myths are shattering. One such myth is exactly how liberating emancipation was.

Jim Downs, author of Sick From Freedom, examined the role of illness, conscription, labor, and organization during the Civil War and Reconstruction. He illustrates the freedmen and freedwomen’s struggle for survival with the story of Joseph Miller. After enlisting to gain protection, food, and shelter for his family, Miller found the promises of Union soldiers weren’t kept. An unprecedented mobile population, unsanitary conditions, inadequate medicine, and war combined to spread illness and sickness among soldiers and refugee slaves. The government and military struggled to cope with the emancipation and reintegration former slaves during the Civil War and Reconstruction, and the same men and women deployed in the Freedmen’s Bureau to help former slaves worked on the relocation and reservation system for Native Americans.

The brief life of former slave Joseph Miller

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Rapid Spread of Illness During the Civil War

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Government Response to Emancipation: Labor, Contraband, and Refugees

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Freedmen’s Bureau and the Native American Reservation System

Click here to view the embedded video.

James Downs is an associate professor of history at Connecticut College and author of Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction, and editor of Taking Back the Academy: History of Activism, History as Activism and Why We Write: The Politics and Practice of Writing for Social Change. Read Jim’s previous blog post “Color blindness in the demographic death toll of the Civil War.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The Victory Odes of Pindar

As the Olympic Games kick off tomorrow, Mayor of London Boris Johnson has ensured that London 2012 retains its ties to the ancient world. Trained as a classicist and fond of reciting Latin (particularly in debate), he commissioned an ode by Armand D’Angour in the style of the Ancient Greek poet Pindar, which was recited at the Olympic Gala at Royal Opera House on July 24th. Oxford University classicist Dr Armand D’Angour’s Olympic Ode will be installed at the Olympic Park in East London, but you can discover Pindar’s verses on the blog today. Here’s an excerpt from the introduction by Stephen Instone to The Complete Odes by Pindar, translated by Anthony Verity:

The victory odes are divided into Olympians, Pythians, Nemeans, and Isthmians after the four great ‘panhellenic’ games that were open to all Greeks. All athletics games in ancient Greece were part of a religious festival in honour of gods or heroes. The Olympic games were the oldest and most prestigious, held in Elis in the western Peloponnese in honour of Zeus. There had been a sanctuary to Zeus there even before the traditional date for the founding of the games (776 BC). Athletics competitions provided an additional way of honouring the god, the winner owing his victory to the help of the god and in consequence thanking the god. The festival lasted five days and took place, as nowadays, every four years. On the first day Zeus apomuios or ‘averter of flies’ was invoked to keep the sacrificial meat fly-free, and on the third day a hundred oxen were sacrificed to Zeus. The programme of events developed and changed during time.

In the fifth century, when Pindar was writing, there were

three running events: the stadion (a sprint the length of the stadium), the diaulos (there and back), and the dolichos (twelve laps);

a race when the runners wore armour and carried a large shield (there and back);

boxing, wrestling, and the pancration (‘all power’, in which virtually any method of physical attack was permitted);

the pentathlon (long jump, sprint, discus, javelin, and wrestling).

Most of these events had separate age-categories for men, youths, and boys. There were also horse an horse-with-chariot races held in the hippodrome. For a few Olympics there was a mule race (Olympian 6 is for a winner in this event); mules were bred in Sicily, and the Sicilian tyrants may have played a part in establishing this event. The Pythian games were held in honour of Apollo at Delphi. The programme was broadly similar to that of the Olympics, but included music competitions (for Apollo the god of music); Pythian 12 is for a winner in the pipe-playing competition. They were traditionally founded in 573, took place every two years at Nemea on the east of the Peloponnese. They were also in honour of Zeus. The Isthmian games, traditionally founded 582, also took place every two years. They were held in honour of the sea-god Poseidon at the Isthmus, the strip of land that then connected the Peloponnese with mainland Greece. In his victory odes Pindar generally refers to the god presiding over the games where the victory had been gained and sometimes the myth relates to the particular games (for example, in Olympian 1 the myth concerns Pelops who had a hero-cult at Olympia).

These four games formed a circuit for athlete, as the Olympics, World Championships, European, and Commonwealth Games do for some athletes today. A few outstanding athletes, such as Diagoras of Rhodes for whom Pindar composed Olympian 7, won at all four (like the British decathlete Daley Thompson who in the 1980s simultaneously held Olympic, World, Commonwealth, and European titles). In most events the athletes competed naked (probably because of the heat). Several times in his odes for victors from Aegina Pindar praises the trainer. Generally, he concentrates on the implications of victory rather than the winning itself, but occasionally he provides interesting athletics details.

In winning at the Olympics both the stadion race and the pentathlon Xenophon of Corinth achieved, according to Pindar, what had never been done before (Olympian 13.29-33). In Pythian 5 (lines 49-51) Pindar says that the charioteer of the victor, the king of Cyrene, was in a race in which forty charioteers fell. The dangers inherent in the equestrian events meant that the mean who entered those events, and who were crowned victors, did not themselves usually ride or drive but employed jockeys and charioteers; but in Isthmian 1 for a chariot-race victor, Pindar says that the winner, Herodotus of Thebes, held the reins himself (line 15), as if this was exceptional. In Isthmian 4, for a Theban pancratiast, Pindar rather surprisingly says that the victor was of puny appearance (line 50) – perhaps a joke for a fellow Theban, The ordering of the odes, Olympian, Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian, reflects the order of the games in terms of their importance; within each group of odes those celebrating victories in the chariot race generally come first because it was the event held in great esteem. No Olympian or Pythian odes is for a victor in the pancration, whereas three Nemeans and Isthmians are; conversely, eleven Olympians and Pythians, but only give Nemeans and Isthmians are for chariot – and horse-race victors. At the major games Pindar focused on the major events.

The Greek poet Pindar (c. 518-428 BC) composed victory odes for winners in the ancient Games, including the Olympics. He celebrated the victories of athletes competing in foot races, horse races, boxing, wrestling, all-in fighting and the pentathlon, and his Odes are fascinating not only for their poetic qualities, but for what they tell us about the Games. Pindar praises the victor by comparing him to mythical heroes and the gods, but also reminds the athlete of his human limitations. The Odes contain versions of some of the best known Greek myths, such as Jason and the Argonauts, and Perseus and Medusa, and are a valuable source for insights on Greek religion and ethics. Pindar’s startling use of language, including striking metaphors, bold syntax, and enigmatic expressions, makes reading his poetry a uniquely rewarding experience.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The tiger: a sad tale of declining numbers

International Tiger Day, also known as Global Tiger Day, is an annual celebration held annually on 29 July. The initiative of the Saint Petersburg Tiger Summit, the day raises awareness of tiger conservation, promotes opportunities for discussing the tiger’s natural habitats, and encourages support for ongoing conservation efforts. Ahead of International Tiger Day this Sunday, we take a look at the threats tigers face today with this amended extract from The Encyclopedia of Mammals.

From the villainous Shere Khan in Kipling’s Jungle Book to the protective “guardian of the west” of Korean mythology, tigers play a more vivid role in the human psyche than perhaps any other animal. Latterly they have become a symbol for conservation, and their survival on the planet has come to represent the human struggle to balance our conflicting needs and desires.

The “Tyger, tyger, burning bright” of William Blake’s famous poem is growing dim. Of the nine recognized subspecies, the three smallest and most isolated are now extinct. The Bali tiger was the first to go – the last reliable sighting was in 1939 – followed by the Caspian and Javan tigers, last seen in 1968 and 1979 respectively. Today, South China tigers are considered to be functionally extinct in the wild by many scientists, and all the others are severely threatened. The best available figures suggest that tiger numbers worldwide declined from perhaps 100,000 at the beginning of the 20th century to approximately 5,000–7,500 at its end. Current estimates of the surviving populations suggest around 1,850 Bengal tigers left in the wild, along with an estimated 500 Malayan tigers, 450 Amur tigers, less than 400 Sumatran tigers, and 300 Indo‐Chinese tigers.

Surviving tigers face three main threats: direct poaching, habitat loss, and prey depletion. The growing demand for tiger bones for traditional Asian medicines, and for skins as trophies, has resulted in ever‐growing losses. The greatest exporter of tiger‐bone products is China, which distributed over 27 million items from 1990 to 1992. Japan, Hong Kong, and South Korea are the largest importers: South Korea took delivery of nearly 9,000kg (20,000lb) of tiger bone between 1970 and 1993. Attempts to control this illegal trade have had results, but it remains substantial.

The threat to habitat comes from the degradation and fragmentation that ensue as human populations grow. As tiger populations become isolated and reduced, the fragmented remnant populations grow increasingly susceptible to extinction. Inventive land‐use plans have been proposed for such countries as Nepal, Thailand, and Russia, seeking to link protected areas via a network of conservation units and ecological corridors that aim to maintain the integrity of entire metapopulations. Such schemes have become more effective with the use of geographic information systems (GIS) that rely on remotely sensed satellite imagery and allow analyses of multiple elements of the landscape, including forest cover, prey densities, and human impacts. Successful habitat restoration projects in Nepal provide incentives to villagers in return for the protection of communal lands.

Even if habitat is successfully protected, sufficient prey must be present. Many tracts in Asia that would otherwise be suitable are devoid of tigers today because of a shortage of large ungulates. An adult tiger can eat 18–40kg (40–88lb) of meat at a sitting, and must kill 50–75 large ungulates a year. For those ungulate populations to persist, predation and other causes of death should not account for more than 30 percent of their numbers annually, and in many cases densities are not high enough to support tigers. In other parts of the tiger’s range, prey only survive in sufficient numbers in protected areas; in the Russian Far East, for example, numbers are often 3–4 times higher inside protected zones. Better controls on ungulate harvest in unprotected areas, along with the elimination of hunting in the protected ones, could benefit both tiger and human populations with the potential for a sustainable harvest.

Ultimately, tigers will survive only if local people find it in their interest to preserve and protect them. Local people in many parts of the tiger’s range regard the animal as a compelling and necessary component of their environment, however much they may fear it. Seeking means to meet the needs of tigers and humans in remaining forest tracts will be the key to the animals’ survival.

Adapted from the entry on ‘Tiger’ in The Encyclopedia of Mammals edited by David MacDonald. Copyright © Brown Bear Books 2012. David MacDonald is Founder and Director of Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles about environmental and life sciences on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Tiger goes into the water. Photo by Schnuddel, iStockphoto.

July 25, 2012

Puzzling heritage: The verb ‘fart’

It cannot but come as a surprise that against the background of countless important words whose origin has never been discovered some totally insignificant verbs and nouns have been traced successfully and convincingly to the very beginning of Indo-European. Fart (“not in delicate use”) looks like a product of our time, but it has existed since time immemorial. Even the nuances have not been lost: one thing is to break wind loudly (farting); quite a different thing is to do it quietly (the now obscure “fisting”). (This fist has nothing to do with fist “clenched fingers” and consequently isn’t related to fisting, a sexual activity requiring, as we are warned, great caution and a lot of tender experience. This reminds me of the instruction Sergei Prokofiev gave to his First Piano Concerto: “Col pugno,” that is ‘with a fist’.)

Both words for the emission of wind (fart and fist) were current in the Old Germanic languages. Frata and físa (the accent over the vowel designates its length, not stress) turned up even in Old Icelandic mythological poems. According to a popular tale, the great god Thor was duped by a giant and spent a night in a mitten, which he took for a house. He was so frightened, as his adversary put it, that he dared neither sneeze nor “fist.” In another poem, the goddess Freyja, notorious for her amatory escapades, was found in bed with her brother and farted (apparently shocked by the discovery).

The words were as vulgar then as they are today. Yet even grammar proves their antiquity. Some verbs (they are called strong) form their principal parts by changing the root vowel, for instance, write/wrote/written, sing/sang/sung. Others (they are called weak) add a dental suffix (d or t) in the preterit and the past participle, for example, beg/begged/begged, look/looked/looked, wait/waited/waited. Strong verbs belong to the most ancient part of the Germanic vocabulary. Fart was one of them; however, it occurred in several forms. Modern German has retained farzen (now a weak verb) and Furz (a noun). In the older period, German also had furzen and ferzan. Engl. fart goes back to ferten, an exact congener of ferzan. Although it was recorded only in the verbal noun ferting, its existence can be taken for granted. I assume that the group er in it changed to ar in the same way in which person yielded its doublet parson and clerk became Clark (in British English, clerk and Clark are homophones).

Icelandic freta and frata were the product of metathesis, that is, the vowel and the consonant r switched places in them. Freta remained a strong verb, but frata became weak. Fortunately, our frat boys seldom if ever take Old Icelandic and are spared the embarrassment. On the other hand, they might enjoy the double entendre. Although part of the oldest stock, the verb for breaking wind was “popular,” even “low,” and this may have been the reason its shape varied so widely. Compare even such more dignified but “common” names as scrimmage and scrummage, mentioned in the June “gleanings,” part 2, and the names recorded for a wagon or cart: lorry, lurry, rolly, and rully, all meaning “trolley.”

An even more surprising thing is that fart is not only ancient Germanic but Common Indo-European. It has cognates from Lithuanian to Sanskrit and Greek, but naturally they begin with p and have d after r (compare Sanskrit pard-, Russian perdet’ with stress on the second syllable, and so forth) because according to a well-known law, Germanic consonants underwent a shift and that is why Latin pater and duo correspond to Engl. father and two.

The most famous plate of The Image of Irelande by John Derrick (1581) shows the chief of the Mac Sweynes seated at dinner and being entertained by a bard and a harper. Note the two other entertainers (braigetóirí or professional farters) on the right. The Image of Irelande by John Derrick, published in 1581. Source: Edinburgh University Library.

The history of fist (to break wind quietly) is similar to that of fart. Vowels in this verb also varied, as evidenced by the Dutch noun veest “fisting”, with ee (pronounced like e in Engl. vest but prolonged!) from ai. Icelandic físa preserved the oldest form, without the suffix t appended to the root. It too has excellent cognates. Apparently, alongside Indo-European perd-, the near synonymous root pezd- existed (another instance of variation!). It must have been current in Proto-Latin. The sought-for cognate in that language is pedo, with long e (its length is a “compensation” for the loss of z). The amazing thing is that the cognates are such a perfect match. For example, Russian bzdet’, as well as its Lithuanian congener, are exact glosses of German fisten and Icelandic físa, namely “break wind without making a noise.” Seeing how broad the range of meanings among cognates usually is, one can only wonder at absolute precision in such a word. In Old French, the reflex of ped- was pet-; hence petard.

If perd- and pezd- arose as variants of the same root, fart and fist are ultimately related and sound imitative, even though in the world of onomatopoeia relatedness is a rather vacuous concept. It may seem that perd and pezd do not render the sound of breaking wind. However, pezd- is rather obviously related to several verbs for whistling and hissing. It appears that everything began with pezd (quiet fisting), which developed into perd, that is, the sound increased in volume (from z to r). At least one eminent language historian set up the ancient root perzd- and allowed the recorded forms to have lost either r or z, but this is a self-serving reconstruction. Such is the tentative history of Indo-European farting, and only one addition is in order here. In Indo-European, many words have variants with and without s- at the beginning. If Latin spiro “blow” (as in Engl. inspire) is one of them (s-piro), it may be allied to the Germanic F-words discussed above.

Those interested in the subject and not only in words may want to read the book by Valerie Allen On Farting: Language and Laughter in the Middle Ages (Palgrave 2007), but should skip the short section on etymology with its erroneous conclusion. Here I will comment on several etymologies about which I have often been asked. Latin perditio (from its oblique case, via Old French, English has perdition) is not allied to the words discussed above. Perdition goes back to the past participle of the verb perdere “destroy; (hence) lose.” It has the prefix per-, and the root -der-, so that r and d do are separated by a morphemic boundary. But if Latin perdix had the ancient root with r, preserved in Old French perdriz, then its English continuation partridge belongs here. According to the usual explanation, a partridge makes a sharp whirring sound when flushed (and thus behaves not unlike a petard – not an overly convincing etymology).

Engl. petition and petulant, from Old French, have the root of Latin petere “seeks; attack. Pet “peeve” should probably be dissociated from collywobbles and the rest, but for Engl. wolf’s fist ~ wolves’ fist and German Bofist ~ Bovist (originally vohenvist “fox’s fist”) “puffball” reproduce Greek lykóperdon “wolf’s fart” and allegedly like partridge, owe their origin to the sound they make when pressed). Few people will remember that in the days of Nikita Khrushchev the only woman in the Soviet Politburo was Ekaterina Furtseva, the minister of culture. That family name made every mention of her in German media a rude joke, for the Germans of course spelled Furzeva or Furtzeva. However, it was derived from the proper name Firs, not from the German verb.

Scatological words are always embarrassing to discuss. But linguists are like doctors: desensitizing makes them indifferent to many things that excite others. In the office they are professionals, and words are just words to them. Other than that, they are normal people.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Genocide and identity conflict

Genocide doesn’t burst out unannounced. It is preceded and prepared by identity conflict that escalates from social friction to contentious politics, from politics to violence, and eventually to targeted mass killing. The United Nations in 1946 defined genocide as “a denial of the right of existence of entire human groups” and redefined it in 1948 as “acts committed with intent to destroy in whole or in part a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” It can be carried out by rebel movements, but it is more frequently the work of the sovereign state.

More strikingly, it is generally not an aggressive but a defensive reaction — pathologically defensive, against a perceived existential threat. Instigators of identity conflict feel themselves targeted, ultimately for extinction, by another identity group whom they feel must be defeated and ultimately exterminated,. So, in a security dilemma, they themselves target the perceived threateners for extinction. Whether this fear is realistic or not is irrelevant; often it is not, usually it has some grain of evidence taken out of proportion, and sometimes it is at least ostensibly accurate. But the point is that political entrepreneurs sell this fear to their client public to gain their support. Peacemakers have the challenge of removing the potential tinder before the arsonist gets to throw a match at it.

Options to prevent this situation are fraught with dilemmas. What is required is a separation of the political entrepreneurs from the public, a move presenting dilemmas in free societies. Democratic rights of free association and speech provide such entrepreneurs with space to mobilize their public (the tinder), overtly or covertly, around identity markers. Removing the fears of identity groups and protecting identity diversity separate the public from the political entrepreneurs’ appeals. This means a return to (or toward) the ideal condition of normal politics, where government responds to the fears, needs, and demands of all of its citizens and the citizens regularly review the record of the government in adequately providing this response.

However, such fears are often deep-rooted, and trust in constitutional arrangements and agents of authority is shallow. Alternative actions to create social, economic, and political conditions that reduce the need and opportunity to mobilize around identity markers are expensive and may alienate other parts of society. If the motivating fears cannot be exorcized, then measures must be taken to disarm those who mold them and render them incapable of causing damage. This is a necessarily intrusive challenge, especially when the political entrepreneur is the government. Telling governments (or rebel movements) that their fears are groundless and that they should be nice to their minorities is not an easily welcomed message.

Obviously, not all identity conflicts end in genocide, so it becomes important to understand the mechanism by which some do. Conflict doesn’t necessarily mean “violent conflict”; the violent stage is an escalation from the initial, political stage of incompatible demands and cannot be understood in isolation from it. The non-violent stage of demonized conflict is the predecessor of genocide itself. Most identity conflicts go through the usual conflict evolutions to victory, stalemate, or fatigue. One side wins, the conflict reaches an impasse and turns to negotiation, or the demonizers weary of their efforts and leave their images in their public’s subconscious for a later day’s use. But some go on, ever escalating the images of the Other until they reach the ultimate confrontation, confirming the fears of the opponents.

Entrapment is the motor of the mechanism. Leaders become entrapped vis-à-vis their public. They have identified the scapegoat and now they must do something about it. Leaders become entrapped vis-à-vis each other; they enter into spirals of outbidding that force them into action. Leaders and followers alike become entrapped vis-à-vis the Other; they must increase their defenses against fear and threats and so enter into the security dilemma and a “spiral of vengeance.” Followers become entrapped vis-à-vis each other; they must follow the mass paroxysm of their neighbors or become its victims. Thus, it isn’t enough to understand the mechanics of genocide; one must understand where it comes from and the mechanics of its origin.

What can negotiation do in such a situation? And what can external parties do to foster negotiation of the measures that are necessary to prevent conflict escalation down the slippery slope toward mass killing and genocide? Blocking that slide means first listening for the frequent early warnings and taking early action. What is needed is a process that removes the feelings of zero-sum threat and fear, and that process has to come from positive interaction between the parties.

That means negotiation, including dialog, ripening, and preemptive accountability, to forestall identity conflict escalation. Intervention when the slide is temporarily arrested (“lest it happen again”) includes monitoring and reconstruction, followed by reconciliation and remediation, once the violence has been brought under control. The blockage of such interaction is what makes the conflict; removing the blockage is the first step towards managing escalation, and the nature of the blockage or conflict imposes its requirements on the substance of the negotiations. Two types of contributions to a solution are available: structural and attitudinal, with continual interrelations between the two. Attitudinal changes are necessary to embark on structural solution searches; effective structural solutions give confidence to parties that there are systems in place to protect identities and make structures stick. They are symbiotic.

I. William Zartman is Jacob Blaustein Professor Emeritus at The Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in Washington DC. His books include Cowardly Lions: Missed Opportunities to Prevent Deadly Conflict and State Collapse and Negotiation and Conflict Management. He is the co-editor of The Slippery Slope to Genocide: Reducing Identity Conflicts and Preventing Mass Murder with Mark Anstey and Paul Meerts. All three editors are on the Steering Committee for the Processes of International Negotiation Network at the International Institute for Applied Systems.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Rosalind Franklin: the not-so-dark lady of DNA

By Jenifer Glynn

If Rosalind Franklin had lived, she would have been 92 today. But she died at 37, five years after the discovery of the structure of DNA had been announced by Watson and Crick. As Crick confessed later (but never confessed to her): “the data which really helped us to obtain the structure was mainly obtained by Rosalind Franklin.” She had been marginalised, and might have been forgotten if Watson hadn’t later portrayed her so unkindly in The Double Helix. The book was enormously successful, but the caricature of Rosalind, appearing ten years after she had died, moved many to rally to her defense. Now, instead of being forgotten, she has become something of a feminist heroine, a symbol of a downtrodden woman scientist. But she was far from being a feminist or being downtrodden.

She was a strong character who was a passionate and fine scientist; she would not have thought of herself as a ‘woman scientist’, fighting for the rights of women. Before she went to work on DNA at King’s College, she had worked in London and Paris on the structure of coals and carbons, producing papers that are still admired and cited. And after King’s she moved to Bernal’s lab at Birkbeck College, working with great success with Aaron Klug on viruses. One fairly safe prediction is that she would have moved with him and the rest of her group to the new Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. She is famous because of her DNA work, but that only took just over two years of her brief life. She had other scientific distinctions, and she had other interests – a love of travel, a love of mountains, and a lively enjoyment of friends.

She was a great letter-writer, and we are lucky that a large pile of her letters survive, with stories of her travels and plans or observations on people and places and politics. Her uninhibited and conversational style of writing is full of her character, from childish enthusiasms and indignation – “I only got B to B+ for that essay, which is very bad (I told you she was an old pig)” – to adult travels – “we started out in cloud at 4.30 a.m. and the cloud lifted suddenly at sunrise, just as we came onto the glacier…. I cannot describe the effect. I can only tell you that the sheer beauty of it made me weep.”

And she was sympathetic to the problems of post-war Paris, “the lower-paid workers have little more than starvation wages, and the urge for increase is an equivalent to an appeal for enough to eat…. My co-workers who have no private means are either in rags or wear clothes sent by friends in America.” She felt herself lucky, for “I find life interesting, I have good friends… and I find infinite kindness and good will among the people I work with. All that is far more important than a larger meat ration or more frequent baths.” “Almost every one I have met,” she wrote, “has spent the war in hiding… but their concentration on the present enables them to start a new life”. Paris, in its recovery from wartime occupation and shortages, was a stimulating place to live, “far and away the best city in the world.” It gave her “a fresh thrill every day when I walk to or from my work along by the Seine.”

Back from vibrant optimistic Paris to grey boring bomb-scarred London she was less ready to be sympathetic. This was of course the time of her famous work, but for her it didn’t start as a happy time. Life was far better at Birkbeck and her virus research there was going wonderfully when her fatal cancer struck.

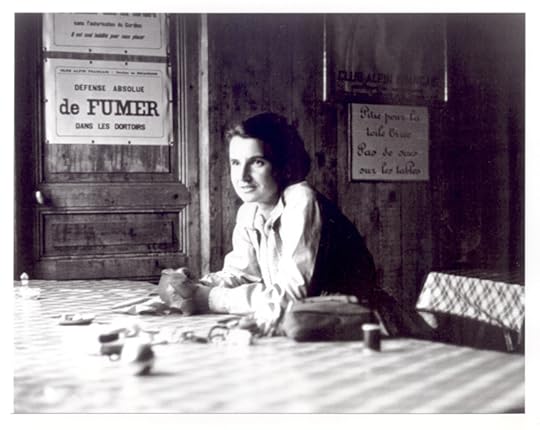

I can’t imagine her at 92. She had packed a lot into her 37 years. My favourite picture of her was taken in 1950 or so, when she was sitting, full of energy and obvious enthusiasm, in this mountain hut in the Alps.

Jenifer Glynn followed her sister Rosalind to St Paul’s school and to Newnham College, where she read history. She started writing when her children had grown up, and is the author of My Sister Rosalind Franklin: A Family Memoir which published this year. Her previous work includes Prince of Publishers, A Biography of the Great Victorian Publisher George Smith; Tidings from Zion, Helen Bentwich’s Letters from Jerusalem 1919-1931; The Life and Death of Smallpox (written with her husband, Ian Glynn); and The Pioneering Garretts.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography has granted free access for a limited time to Rosalind Franklin’s biography. You can also listen to Franklin’s biography as an episode in ODNB’s free biography podcast series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers