Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1049

June 20, 2012

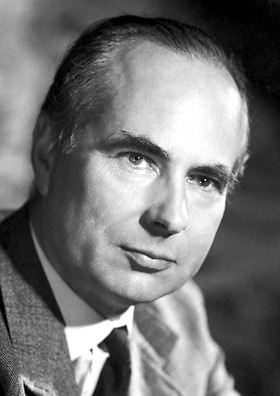

Thoughts on the Passing of Sir Andrew Huxley, OM, FRS, Nobel Laureate

With the death of Sir Andrew Huxley on 30 May 2012, the world lost not only an intellectual giant but a man respected, admired, and loved by all who knew him. Born into a most distinguished family, Andrew was at the age of 94, likely to have been the last surviving grandchild of T. H. Huxley, the Victorian scientist and educator, and the friend and champion of Charles Darwin. Andrew’s brothers (by his father’s first marriage) included Julian Huxley, the zoologist and first Director-General of UNESCO, and Aldous Huxley, the author of Brave New World. Of the many family members, it was perhaps his grandfather that Andrew had most closely resembled for both had studied medicine, been fascinated by microscopy at an early age, and had chosen physiology as their field of scientific study. Indeed, Andrew would sometimes draw on something that T. H. Huxley had written to illustrate one of his own lectures or essays.

Among physiologists, it is well known that Andrew shared the Nobel Prize with Alan Hodgkin and John (Jack) Eccles in 1963. Less well known is the fact that when Andrew and Alan Hodgkin made their first breakthrough in the study of the nerve impulse in 1939 — by recording with an electrode inside the giant axon of the squid — Andrew was only 21. When the work was continued after the Second World War, it was Andrew who got the newly-constructed voltage clamping circuit to work and carried out the complex and enormously lengthy calculations using a hand calculating machine that resulted in the famous Hodgkin-Huxley equations of nerve membrane excitation.

As if this was not a sufficient achievement, Andrew then went on to study muscle contraction, using an interference microscope of his own design, and simultaneously with Hugh Huxley (no relation) developed the sliding filament theory. He also made a critical observation as to how excitation was carried from the surface to the interior of the muscle fibre. There were many who thought that the two Huxleys should have shared a Nobel Prize for this fundamental and highly important work, which would have been Andrew’s second such award. Andrew’s last experiments were on molecular motors (such as those responsible for the sliding muscle filaments) and the table in his rooms at Trinity College Cambridge was often heaped with scientific papers on this subject from other laboratories. Interestingly, the Brunsviga calculating machine, used for the Hodgkin-Huxley equations, remained on top of a filing cabinet in a corner of the same room.

My first-hand knowledge of Andrew was gained as a young postdoctoral fellow at University College London, at the time that he was the Jodrell Professor. To us younger ones, he was like a god and it was notable that even the senior members of the physiology department would bring their research problems to him for help, despite the fact that they were outside Andrew’s own field of interest. Foolishly, some of us thought we might beat him at tennis during the annual departmental retreat at Shenley, but he was too good for us at that, too. Indeed, he remained very fit until late in life and could still run up the stairs, two at a time, well into his eighties. Later I had the privilege of being entertained by Andrew in his lovely Grantchester home. His kindness, thoughtfulness, and decency were qualities long remembered.

Finally, it was Andrew’s life and achievements that provided the inspiration for my recent book, Galvani’s Spark: The Story of the Nerve Impulse, published last August by Oxford University Press. I could not have been happier when Andrew accepted the dedication.

Andrew Fielding Huxley

22 November 1917 – 30 May 2012

Dr. Alan J. McComas was born in Bruce Rock in Western Australia and immigrated to the United Kingdom where he attended Great Yarmouth Grammar School. He received both his BSc in physiology and MBBS from Durham University in the UK and was trained at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle upon Tyne, the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases in London, and the Department of Physiology at the University College London. After successive positions at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, in 1971 he became Professor of Medicine (Neurology) at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. In 1988, he also became the Founding Chair in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at McMaster University. Since 1996 he has held the position of Emeritus Professor of Medicine.

Dr. McComas has pursued a successful career in medicine and physiology. His research accomplishments include some of the earliest microelectrode studies of muscle diseases, the electrophysiological estimation of numbers of human motor nerve fibers, and, more recently, the demonstration that magnetic stimulation of the brain may abort migraine attacks. In 2001, he achieved the Distinguished Researcher Award of the American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine. He was also awarded a Fellowship of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh in 2005. On two occasions, he has been peer-ranked in the top 2% of doctors in North America. He has authored or coauthored seven books.

Children, Etymologists, and Heffalumps

The problem with Christopher Robin’s woozles and heffalumps was that no one knew exactly what those creatures looked like. The boy just happened to be “lumping along” when he detected the exotic creature. “I saw one once,” said Piglet. “At least I think I did,” he said. “Only perhaps it wasn’t.” So did I,” said Pooh, wondering what a Heffalump was like. “You don’t often see them,” said Christopher Robin carelessly. Tracking a woozle was no easy task either. “Hallo!” said Piglet, “what are you doing?” “Hunting,” said Pooh. “Hunting what?” “Tracking something,” said Winnie-the Pooh very mysteriously. “Tracking what?” said Piglet, coming closer. “That’s just what I ask myself. I ask myself, What?” “What do you think you’ll answer”? “I shall have to wait until I catch up with it,” said Winnie-the-Pooh. Children and etymologists share a good deal of common ground; they hope to find the creatures they have never seen. It is no wonder that their chances of success are slim.

Milne coined two wonderful words (among many others). Have-a-lump, changed into heffalump, which, in turn, suggested to Christopher Robin that he was “lumping along,” or perhaps he first decided that he was “lumping” and then invented a corresponding name. In any case, the fit could not be better, for the terrible beast, as it turned out, was the bear with its head stuck fast in an empty honey jar. Pooh certainly had a lump. Woozle is a classic sound symbolic formation; the animal having such a name must be fat, furry, and possibly dangerous (or even Dangerous). I am sorry for hunting the jokes into the ground, but this is the way etymologists always behave. Most of them are like me; they are dedicated people who ply their trade in the gravest way possible. For example, an etymologist knows what shrew means (to give an arbitrary example) and tries to understand why people called the little rodent that. A child deals with words and asks how the union of sound and sense came about. In the end, they may have their moment of triumph. Probably everybody has read Winnie-The-Pooh. It is also possible that everybody has read Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking. But I am not sure that everybody remembers Pippi’s adventure in word origins. So here it is.

One day Tommy and Annika, Pippi’s friends, found her in an especially happy mood. “In any case, you should know that I found it. I, and no one else,” she announced. The children’s curiosity was piqued. What could Pippi have found? A new word, a beautiful, brand-new word — spunk. Now, the original is of course in Swedish, in which spunk means nothing (at least it does not occur in the multivolume dictionary of the Swedish Academy or the Swedish Dialect Dictionary). Whoever translates this chapter has to invent something similar and original, corresponding to the spirit of the language. (Also, Swedish u designates a sound that has no analog among English vowels and is quite unlike what one hears in Engl. spunk, junk, monk, bunk.) The English translation I have consulted suggested spink, not a bad equivalent. The Russian translator introduced kukariamba! The German version and the editions in Romance languages were not available to me, and I did not go to the trouble of ordering them. After all, this is not a treatise on the art of translating.

Tommy, naturally, asked “What does it mean?” Pippi’s melancholy answer was “If I knew,” though she felt confident that (let us say) spink did not mean “vacuum cleaner.” Annika responded that if the inventor did not know what the word means, it was of no use, a statement in which Pippi reluctantly acquiesced. But Tommy had a more important question: “Do you know who decides which words mean what?” Pippi responded that very old professors do. They had already coined a lot of useless words, while “spink” was the very treasure of a word and yet no one knows what it means, “and it was so hard to find it too!” Perhaps it is the sound one hears when one walks through deep mud? No, for that there is a different word. Also, they listened to the sound and were reassured.

What follows is slightly reminiscent of Luigi Pirandello’s plot in Six Characters in Search of an Author, though with less drama and more in the spirit of A. A. Milne. The children go from place to place in the hope of buying “spink” or at least “a spink.” First they walked into a candy store, fearful that the last piece of “spink” had been sold before they arrived. The store owner hedged for some time, pretended that quite recently she had had it, but finally confessed that she had never seen “spink.” Then they rode, for the expedition proceeded on horseback (don’t forget Pippi’s favorite horse) to a hardware store. There the owner tried to palm off a rake, but Pippi refused the bargain with indignation. She always called a spade a spade and a rake a rake and informed the man that a hundred professors knew all about it. Suddenly it occurred to her that “spink” was a disease. However, the doctor looked at her tongue, examined the rest of her very healthy anatomy, and suggested that even if she had eaten a plate of brown shoe polish and washed it down with a lot of milk, the symptoms would not have made him detect any symptoms of “spink.” Moreover, it appeared that a disease with such a name did not exist. Finally, Pippi frightened two respectable ladies out of their wits when she climbed into their room through the window and wondered whether the terrible “spink” had not hidden somewhere in their vicinity. Alas, the search produced no monster.

Disappointed, even disheartened, the children returned to Pippi’s house and Tommy almost trod on a tiny beetle, a very pretty beetle too, with green wings (incidentally, wing covers of an insect are or at one time were, for example, in Shakespeare called shards). It did not look like any beetle they had ever seen and it suddenly dawned on Pippi that this WAS the “spink.” How funny. They had looked for it everywhere while it lived close by in Pippi’s garden. The end is very much like Milne’s, but I don’t know whether the coincidence is accidental or intentional. I suspect that the numerous scholars who studied Lindgren’s works discussed this problem at boring length and even interviewed her about it. Most probably, she invented the story herself, because any close observer of children knows how revealing their linguistic awakening is. Eeyore, a great ruminator, was once caught repeating inasmuch as and asking himself: “Inasmuch as what?” Sooner or later every child begins to ask where words come from and why they mean what they do, while etymologists never grow up and keep pondering the same question as long as they live.

The one and only spink (imported from Sweden).

It may be fair to finish this story by saying that the origin of English, not Swedish, word spunk in all of its senses is obscure. In two weeks I will address Engl. spunk while riding my high etymological horse, which cannot be compared to or with Pippi’s (nor can I lift it), but it is the only beast of burden I own.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Muddling counterinsurgency’s impact

John A. Nagl, a noted commentator on military affairs, blurs many lines in his effort to claim success for counterinsurgency tactics in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. For example, he correctly observes that in Iraq in 2007 both the counterinsurgency (COIN) methods employed during the American troop surge and the Sunni Awakening helped reverse the tide of violence. Yet he quickly brushes past the impact of the latter when he asserts “[t]he surge changed the war in Iraq dramatically.” Similarly, in discussing Afghanistan, he blends COIN tactics with targeted counterterrorism strikes when he claims that “the strategy… worked to a degree” in effectively dismantling Al Qaeda. In the end, he insists, counterinsurgency gives us messy outcomes, the best we can hope for in these struggles.

Nagl leaves out a critical element contributing to the survival of US-backed regimes facing ongoing insurgencies. In both Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States has concluded credible long-term security agreements with the governments we have supported. Simply put, we are not leaving, even after our combat forces have been withdrawn. The continuing American presence assures the local government that it will not be abandoned to face its adversaries alone. They in turn must recognize that the resources of the United States will still shore up the government. Both sides thus have a greater incentive to work toward a political accommodation.

Contrast this with the endgame in Vietnam. There any American commitment to sustain the Saigon regime rested on Richard Nixon’s empty private pledge to respond with force to North Vietnamese violations of the Paris Peace agreement. He had failed earlier to secure either congressional or popular support for an ongoing security partnership. Within months, moreover, it became evident that Nixon had no intention of honoring his words.

COIN supporters, both within the military and beyond, may yet make a case that counterinsurgency methods represent a viable political-military tool that can contribute to a broader strategy to support regimes in which the United States has a vital interest. But the argument should not rest on eliding the complexities of the wars in which COIN methods have been tried or on overlooking the much more direct contribution of a binding security partnership.

Andrew J. Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read his previous blog posts: “Obama v. Romney on Afganistan strategy” and “Mitt Romney as Commander in Chief: some troubling signs.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Alan Turing’s Cryptographic Legacy

I’ve always been intrigued by the appeal of cryptography. In its most intuitive form, cryptography is the study of techniques for making a message unreadable to anyone other than the intended recipient. Why is that so intrinsically interesting to so many people?

The answer has at least something to do with our natural human curiosity. We have a fascination for puzzles and mysteries. We love secrets. Cryptography uses secrets to transform messages into puzzles which can then only be solved by anyone else sharing the original secret. To everyone else the puzzle remains a mystery. How wonderful is that?

Cryptography is, however, a deadly serious game. For centuries cryptography has been a tool deployed in times of conflict to protect military communications from being understood by “the enemy”. This is the context in which Alan Turing cut his name as a cryptographer during the Second World War. Turing worked for the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park and is most famous for his contributions to the demystification of the Enigma encryption machines that the Axis powers used to protect their communications. Turing’s contributions to cryptanalysis, the art of defeating cryptographic schemes, were insightful. In particular, he is credited as being one of the main contributors to the design of the bombe, an electromechanical machine used to search for vital Enigma settings.

The efforts of the men and women of Bletchley Park are widely regarded as having played an important role in drawing the war to a close. Bletchley Park is open to the public and a highly recommended day out. You can see a replica bombe and a striking sculpture of Alan Turing, carved from slate by artist Stephen Kettle.

Alan Turing. Sculpture by Stephen Kettle. Bletchley Park. Photo by Jon Callas. Creative Commons License.

There is much more, however, to both cryptography and Alan Turing’s cryptographic legacy.

I don’t think it’s too shallow to claim that Turing was a genius. To me the strongest evidence is the fact that his work has had significant impact across several different fields of science, cryptanalysis being just one. His work on the theory of computation, along with his Bletchley experience, inevitably drew Turing into the post-war development of early computing machines. Turing was a key player in the initial convergence of theory and practice which enabled the modern computer to emerge in the subsequent decades. Turing was there at the very start. Who knows where our computing journey will end?

What we do know is that modern life would be barely imaginable without the networks of computing devices on which we now rely. We talk, we write, we trade, we bank, we play — all on computers. Our world, which once relied on physical presence and boundaries for its security, is now an open digital one. Without the right precautions we can never be sure, for example, who is taking our money online, what amount they really are taking, and who might be listening in. It’s scary, if you think about it for too long.

The good news is that this digital world can be made secure through the use of, guess what? Cryptography! Significantly, the cryptography used today provides much more than the creation of puzzles from secrets that was first alluded to. The requirement to secure computers has necessitated the development of many different types of cryptography that go far beyond the basic encryption of secret messages that Turing so admirably wrestled with in the 1940s. Modern cryptography also provides services which help to detect unauthorised modification of data. Cryptographic mechanisms can be deployed to assure the source of a digital communication. Cryptography can even be used to create digital analogues of handwritten signatures.

Rather than being a technology only encountered by brilliant mathematicians in the most desperate of times, cryptography is now something that, without even realising, we use every day. We rely on cryptography when we chat on our mobile phones, when we withdraw cash, when we make purchases over the Internet, even when we open our car door. During the Second World War, the Allied Powers nearly didn’t prevail because of the use of cryptography. Now none of us can survive without it.

Even at mass entertainment level, there is cryptography. I smile at the popularisation of the unbreakable encryption technique known as the one-time pad. I see people every day wrinkling their brows during attempts to construct complete specifications of one-time pads from partial information in a newspaper. Perhaps you know these better as Sudoku Squares? You see, we really do love puzzles, mysteries, and secrets. The eternal appeal of cryptography is guaranteed.

I would argue that cryptography is important, useful, clever, and fun, which I think is a charmingly rare combination. I am sure that Alan Turing would agree.

Prof. Keith Martin is Director of the Information Security Group at Royal Holloway, University of London and author of Everyday Cryptography. An active member of the cryptographic research community, he also has considerable experience in teaching cryptography to non-mathematical students, including industrial courses and young audiences. Since 2004 he has led the introductory cryptography module on Royal Holloway’s pioneering MSc Information Security.

OUPblog is celebrating Alan Turing’s 100th birthday with blog posts from our authors all this week. Read our previous posts on Alan Turing: “Maurice Wilkes on Alan Turing” by Peter J. Bentley and “Turing : the irruption of Materialism into thought” by Paul Cockshott. Look for “Turing’s Grand Unification” by Cristopher Moore and Stephan Mertens and “Computers as authors and the Turing Test” by Kees van Deemter later this week.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles about technology the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

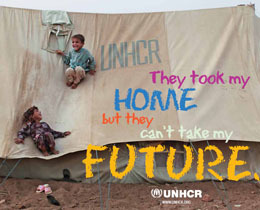

World Refugee Day: holding up the mirror?

You may be aware that today, 20 June 2012, is World Refugee Day. At one level, World Refugee Day is a time to pause and take stock of the state of international protection, to examine anew the myriad causes of refugee flows and the strengths and weaknesses of the international protection system. It is a time to reaffirm the importance of the 1951 Refugee Convention but also to ask afresh important questions: who today is in need of protection, and why?

You may be aware that today, 20 June 2012, is World Refugee Day. At one level, World Refugee Day is a time to pause and take stock of the state of international protection, to examine anew the myriad causes of refugee flows and the strengths and weaknesses of the international protection system. It is a time to reaffirm the importance of the 1951 Refugee Convention but also to ask afresh important questions: who today is in need of protection, and why?

Traditionally, the concept of “persecution” has underpinned the international protection system. A refugee is any person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country…”. While these grounds of persecution have been progressively developed to meet new protection needs, we need to ask how adequate the Refugee Convention is to meet the challenges of the contemporary context. According to UNHCR, “climate change-related movements are predicted to be one of the biggest drivers of displacement and migration over the next century.” However, climate-related displacement alone has been said to expose the inadequacy of the current protection framework to meet contemporary challenges and to point to the need for new international frameworks or instruments. (On the issue of climate change and international law, see further Jane McAdam, Climate Change, Forced Migration, and International Law). Then again, how might the current, legitimate focus on climate-related displacement blind us to other protection needs? Who is falling between the cracks of the international system? Who is left out in the cold by today’s hot topics?

Even where a person may fall within recognized refugee definitions, they may still face insurmountable hurdles in gaining admission to a state where they can claim refugee status. Though fleeing persecution, a refugee remains a non-national of any state but their own, a fact of enduring importance in a world where, international human rights law notwithstanding, states retain significant discretion in the admission of non-nationals. Access to protection remains elusive when confronted with interception policies preventing “unauthorised arrivals” by boat or other means, and “pushbacks” are unaccompanied by procedures to determine the protection needs of those on board. (Alongside these more blatant non-admission practices are those more invisible admission barriers such as strict visa regimes for nationals of “refugee producing” states and pre-embarkation checks). While non-admission policies may at times be framed as a response to people smuggling, populist politics and exploitation of security fears may also be at play. At the same time, the challenges confronting states are not to be underestimated. Consider Greece which for all its current troubles is still on one estimate the entry point for “more than 80% of all irregular entries into the EU”.

In the midst of economic crises, rising unemployment in many parts of the world, and political and social instability, one of the greatest challenges facing the international protection system – perhaps history will show it to have been the greatest of all – is the age-old recipe of human fear and insecurity mixed, more often than not, with rejection of the “other” and neglect of the weakest. If World Refugee Day prompts us to pause and examine the strengths and weaknesses of the current protection system, we are under no less of an imperative to ask of ourselves and the governments we live under those timeless and ever-timely questions of the meaning of “democracy” and “justice”, and of whether everyone has the “right to have rights”, those very questions which may recede from view in the face of the seemingly more urgent “imperatives” of “austerity” or “balanced budgets”.

In the midst of economic crises, rising unemployment in many parts of the world, and political and social instability, one of the greatest challenges facing the international protection system – perhaps history will show it to have been the greatest of all – is the age-old recipe of human fear and insecurity mixed, more often than not, with rejection of the “other” and neglect of the weakest. If World Refugee Day prompts us to pause and examine the strengths and weaknesses of the current protection system, we are under no less of an imperative to ask of ourselves and the governments we live under those timeless and ever-timely questions of the meaning of “democracy” and “justice”, and of whether everyone has the “right to have rights”, those very questions which may recede from view in the face of the seemingly more urgent “imperatives” of “austerity” or “balanced budgets”.

Are questions like these hopelessly naïve – a luxury in such times as ours? To answer that question is to hold up a mirror to one’s own society. In the words of UNHCR’s Director of International Protection, “attitudes toward international refugee protection serve as a kind of litmus test of the health of our democratic societies. The institution of asylum is itself a reflection of values such as justice, fairness and equality – its existence an indicator of the importance of these values in society as a whole.” Our attitude towards the most vulnerable in our midst and at our door may reveal more of the true values and concerns of our societies and our own lives than we care to admit. On World Refugee Day, will we hold up that mirror?

Alison Kesby researches in the area of public international law and international human rights law. Her book The Right to have Rights: Citizenship, Humanity, and International Law was published by Oxford University Press in January 2012. It examines the significance and limits of nationality, citizenship, humanity, and politics for right bearing, and argues that their complex interrelation points to how the intriguing and powerful concept of the “right to have rights” might be rearticulated for the purposes of international legal thought and practice.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

June 19, 2012

Attack ads and American presidential politics

Politics appears to have become a ‘dirty’ word not for the few but for the many. Across the developed world a great mass of ‘disaffected democrats’ seem increasingly disinterested in politics and distrustful of politicians. My sense is that the public long for a balanced, informed, and generally honest account of both the successes and failures of various political parties and individuals but what they tend to get from the media, the blogosphere, most commentators, and (most critically) political parties is a great tsunami of negativity or what I call ‘the bad faith model of politics’. Put slightly differently: public skepticism is a healthy element of any democracy, but surely we have slipped into an atmosphere that is awash with corrosive cynicism.

The American presidential race provides arguably the most far-reaching and destructive case study of the ‘bad faith model of politics’. The Republican Party plans, according to the New York Times (May 17 2012), to run a series of anti-Obama hard-line attack ads that will plum new depths in terms of what is generally known as ‘attack politics’. The Democrats, to be fair, will undoubtedly seek to frame Mitt Romney in ways that are hardly designed to flatter.

Politics fuelled by aggression has created a form of political competition akin to modern warfare (strategy, communication, troops, etc.) in which the role of political actors is to ‘attack’ anyone who disagrees with them. As such the language, discourse, and tactics of politics is generally focused on negative campaigning, personal slurs, and a view of politics that defines any willingness to engage in serious debate, offer to negotiate, or change your mind as evidence of weakness. It is bitter, short-tempered, and its ambition is to sneer and jibe mercilessly; so obsessed with winning at all costs it cannot see that a political strategy based on the use of aggression to win office can only fail in the long term.

More importantly, away from the bear pit of the legislature or television studio, political life is focused on the maintenance of a system in which ideas, conflicts, and interests are openly articulated and peacefully resolved. It is rarely glamorous or easy, it is often dull and messy, and it is generally not a profession full of liars, cheats, and scoundrels (every profession has its bad apples and politics is no different). It is, however, an increasingly hard and brutal business. It is not for the faint-hearted and although this has always been the case, there has been a step-change in recent years in relation to the intensity of the pressures, the brutality of the criticisms, the personalized nature of the attacks, and the arbitrary targeting by the media and political opponents. The storm that to some extent inevitably encircles democratic politics has for a range of reasons become more intense and toxic. My concern is that we are hollowing out the incentives that need to exist to attract the best people from all walks of life to get involved and stand for office. A process of demonization has occurred that can only end in a situation where ‘normal’ people feel inclined to walk away, leaving only the manically ambitious, socially privileged, or simply weird in their stead. In a sense we risk creating a self-fulfilling prophecy that politicians are ‘all the same’ exactly because of the climate we have created.

This narrowing of the talent pool from which politicians are increasingly drawn is directly attributable to the sheer force of the storm that is constantly breaking upon the shores of politics. Politicians must operate with an almost perpetual swirl of scandal and intrigue breaking around their heads. Many good people currently brave the storm in the hope of making a positive difference to their community, city, or country. But someone with a life, a family, interests beyond politics, and the ability to do other things, can feel deeply inclined to stick to them and leave the political storm to itself. We need to calm the storm. Attack politics in general and attack ads in particular benefit only the sellers of expensive advertising space and certainly not the public.

Matthew Flinders is Professor of Politics at the University of Sheffield. His latest book, Defending Politics: Why Democracy Matters in the 21st Century, has just been published by Oxford University Press. His book Delegated Governance and the British State was awarded the W.J.M. Mackenzie Prize in 2009 for the best book in political science. He is also the author of Democratic Drift and co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of British Politics. Read his previous blog post “It’s just a joke!” on political satire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Kodachrome America

In 1938, Charles Cushman commenced his Kodachrome journey across America. At the same time, architects and city planners began to extend the tools of historic preservation beyond their original applications. From Santa Fe to Charleston, city councils experimented with new powers, daring to extend protections once reserved for isolated battlefields, Great Men’s homes, or government buildings to include entire neighborhoods. They argued that the public benefit derived from preserving architectural character outweighed an individual owner’s rights to do with his property what he wished. Federal relief funds paid architects to measure aging buildings, writers and photographers to survey historic districts, real estate analysts to assess urban housing stock. Suddenly, the inner city seemed an interesting place.

Old Town, Albuquerque, 1963. Source: Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection, Indiana University.

Old Town, Albuquerque, 2012. Photo by Eric Sandweiss.

The preservation boom grew from the development bust. Had falling property values (particularly in the central cities) not threatened public coffers and private fortunes, it’s hard to imagine that American investors would have thought twice about the potential value of those sites that had yet survived the developer’s natural and longstanding inclination to demolish, rebuild, densify, intensify. Seeking virtue in necessity, landowners and civic officials worked on two fronts from the 1930s through the postwar years. They sought incentives for blighting and demolishing some declining properties, while they reimagined others as sites of “gracious living” and “gaslit elegance,” or as “proud reminders of a bygone era.” They counted on the new preservation ordinances to minimize the risk then associated with choosing maintenance and restoration over new construction.

200 block Main St., Los Angeles, 1952. Source: Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection, Indiana University.

200 block Main St., Los Angeles, 2012. Photo by Eric Sandweiss.

Walking the streets of Albuquerque, New Orleans, Savannah, and other aging cities in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, Cushman fixed his lens on buildings that would soon find their way into both categories. His photographic remembrance of things past took him both to future redevelopment sites and to future showcases of preservation. In recent weeks, retracing the amateur photographer’s routes through the Southwest and California, I am reminded that the two paths to midcentury urban redevelopment — preservation and demolition — more often complemented than conflicted with one another. Preservation controversies were settled as often by gentleman’s agreement in the city council chamber as they were by grassroots protest in the street.

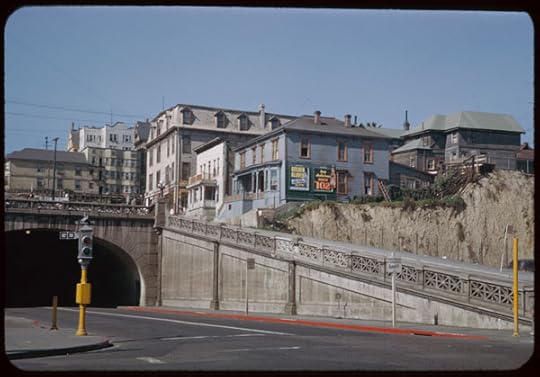

2d and Hill St., Los Angeles, 1952. Source: Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection, Indiana University.

2d and Hill St., Los Angeles, 2012. Photo by Eric Sandweiss.

Albuquerque’s Old Pueblo, protected (and fixed up) in the 1940s to expand tourist and commercial trade from the city’s distant downtown, still functions in much the way it was intended — leveraging the city’s Hispanic heritage to add commercial vigor to an aging west side neighborhood. Along San Francisco’s Embarcadero, a workday army of technology and marketing professionals crosses the pedestrian landscape of Levi’s Plaza — ground that once knew the heavy bootsteps of longshoremen and the rumble of trucks. In Los Angeles, the return of the Angels Flight funicular up the side of Bunker Hill adds a touch of historical continuity to a part of town otherwise unrecognizable from Cushman’s day, and in the process seeks to connect the commercial success of the redeveloped landscape atop the hill with the more depressed downtown zone of Hill, Broadway, and Main Streets, lying to its east.

Telegraph Hill from the Embarcadero. Source: Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection, Indiana University.

Telegraph Hill from the Embarcadero, 2006. Photo by Eric Sandweiss.

Like most Americans of his day, Charles Cushman was neither preservationist nor modernist. He enjoyed pieces of both past and present, using his camera to assemble a picture of his “day in its color,” and seldom peering incisively into the shadows of class or race inequality or environmental degradation that lay beneath its surface. Cushman does not ask that we rush to his side in defense of these sites of imminent change, but neither do his pictures suggest confidence that something better awaits. His job (and his real job, at that) was to predict where the market was headed, not to take it there.

Eric Sandweiss is Carmony Professor of History at Indiana University. He is the author of The Day in Its Color: Charles Cushman’s Photographic Journey Through a Vanishing America, co-author of Eadweard Muybridge and the Photographic Panorama of San Francisco (winner of Western History Association’s Kerr prize for best illustrated book), and author of St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape. Eric’s next and last appearance will be a book talk at Left Bank Books in Saint Louis, MO on June 21 at 7:00 p.m. Read his previous blog posts “Charles Cushman and the discovery of Old World color” and “Bits and Pieces of the Mother Road.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art & architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Turing : the irruption of Materialism into thought

This year is being widely celebrated as the Turing centenary. He is being hailed as the inventor of the computer, which perhaps overstates things, and as the founder of computing science, which is more to the point. It can be argued that his role in the actual production of the first generation computers, whilst real, was not vital. In 1946 he designed the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), a very advanced design of computer for its day, but because of its challenging scale, initially only a cut down version (the Pilot ACE) was built (and can now be seen in the Science Museum). From 1952 to 1955, the Pilot ACE was the fastest computer in the world and it went on to be sucessfully commercialised as the Deuce. In engineering terms though, none of the distinctive features of Turing’s ACE survive in today’s computer designs. The independent work of Zuse in Germany or Atanasoff in the US indicates that electronic computers were a technology waiting to be discovered across the industrial world.

What distinguished Turing from the other pioneer computer designers was his much greater philosophical contribution. Turing thought deeply about what computation is, what its limits are, and what it tells us about the nature of intelligence and thought itself.

Turing’s 1936 paper on the computable real numbers marks the epistemological break between idealism and a materialism in mathematics. Prior to Turing it was hard to get away from the idea that through mathematical reason, the human mind gained access to a higher domain of Platonic truths. Turing’s first proposal for a universal computing machine is based on an implicit rejection of this view. His machine is intended to model what a human mathematician does when calculating or reasoning, and by showing what limits this machine encounters, he identifies constraints which bind mathematical reasoning in general (whether done by humans or machines).

From the beginning, he emphasises the limited scope of our mental abilities and our dependence on artificial aids — pencil and paper for example — to handle large problems. We have, he asserted, only a finite number of ‘states of mind’ that we can be in when doing calculation. We have in our memories a certain stock of what he calls ‘rules of thumb’ that can be applied to a problem. Our vision only allows us to see a limited number of mathematical symbols at a time and we can only write down one symbol of a growing formula or growing number at a time. The emphasis here, even when he looks at the human mathematician, is on the mundane, the material, the constraining.

In his later essays on artificial intelligence Turing doesn’t countenance any special pleading for human reason. He argues with his famous Turing Test that the same criteria that we use to impute intelligence and consciousness to other human beings could in principle be used to impute them to machines (provided that these machines communicate in a way that we can not distinguish from human behaviour). In his essay ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence,’ he confronts the objection that machines can never do anything new, only what they are programmed to do. “A better variant of the objection says that a machine can never ‘take us by surprise’…. Machines take me by surprise with great frequency. This is largely because I do not do sufficient calculation to decide what to expect them to do, or rather because although I do a calculation, I do it in a hurried, slipshod fashion, taking risks.”

Turing starts a philosophical tradition of grounding mathematics on the material and hence ultimately on what can be allowed by the laws of physics. The truth of mathematics become truths like those of any other science — statements about sets of possible configurations of matter. So the truths of arithmetic are predictions about the behaviour of actual physical calculating systems, whether these be children with chalks and slates or microprocessors. In this view it makes no more sense to view mathematical abstractions as Platonic ideals than it does to posit the existence of ideal doors and cups of which actual doors and cups are partial manifestations. Mathematics then becomes a technology of modeling one part of the material world with another. In Deutch’s formulation of the Turing Principle, any finite physical system can be simulated to an arbitrary degree of accuracy by a universal Turing machine.

Paul Cockshott is a computer scientist and political economist working at the University of Glasgow. His most recent books are Computation and its Limits (with Mackenzie and Michaelson) and Arguments for Socialism (with Zachariah). His research includes programming languages and parallelism, hypercomputing and computability, image processing, and experimental computers.

OUPblog is celebrating Alan Turing’s 100th birthday with blog posts from our authors all this week. Read the previous post in our Turing series: “Maurice Wilkes on Alan Turing” by Peter J. Bentley. Look for “Alan Turing’s Cryptographic Legacy” by Keith M. Martin, “Turing’s Grand Unification” by Cristopher Moore and Stephan Mertens, and “Computers as authors and the Turing Test” by Kees van Deemter later this week.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only mathematics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Lady/Madonna: Profits and perils of the same song

We’ve all had the experience: you’re listening to the radio on your morning commute or walking through the mall one Saturday afternoon when a tune catches your ear. There’s something familiar about it, but upon further listening you know that it’s a new song. What about it sounds the same as the song already in your head?

One of the biggest knocks against pop music is that it lacks originality. Not only does it seem as if every song is about love — or its less exalted cousins — but the music itself is remixed, reused, and recycled. By its very nature, pop music is designed to appeal to the lowest common denominator of our musical taste and attention. It’s meant to catch and to keep our ear from the very first note.

Beat- and hook-driven, and usually clocking in at three or four minutes, pop songs comprise the perfect soundtrack for the Information Age. Whereas orchestral performances and jazz sets demand a certain studied attention, even an attitude of repose, pop tunes are meant to accompany our daily lives. You can drive, text, drive and text, run on the treadmill, or accomplish any number of other activities while you listen.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The opportunity costs of listening to Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe,” the number one song on this week’s Billboard Hot 100 chart, are modest as are, it might be argued, its rewards. On the other hand, Felix Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony or Duke Ellington’s Black, Brown, and Beige, require some understanding of their respective conventions and a mind free to engage them at length. The price of the ticket is high, but the rewards are generous.

Though pop songs are almost always general admission tickets and though their aesthetic rewards may sometimes be limited, we underestimate their value at our own detriment. For it is in the realm of popular music that some of the most daring artistic innovations are now taking place. To appreciate pop, however, we must rid our minds of one hidebound assumption about artistic creation — that art’s primary identifying quality is originality.

I write in praise of same songs, songs that borrow and even steal. I write in praise of lists made for kisses and eyes of tigers. I’m here to tell you that no pleasure is guilty and that there’s good reason that Led Zeppelin, REM, and Depeche Mode have never had a number one single while Rihanna has ten. You see, when it comes to pop listening pleasure, originality matters surprisingly little.

Imagine a sliding scale of imitation that runs from the cover song on one side to copyright infringement on the other. At one extreme, we have the cover, a new and credited version of an existing song. Covers run the gamut from the kind of slavish imitation that makes you wonder why it was done at all, to reinventions that eclipse the artistry of the original. In 1932 the Ray Noble Orchestra scored a modest hit with a torch song called “Try a Little Tenderness.” More than thirty years later, Otis Redding did a cover of it so exquisite and soulful that all other versions now exist as footnotes.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Given that music is above all a business, however, the act of enforcing copyright has become a zealous pursuit of record labels and rights holders. Artists from Michael Jackson to The Verve, Michael Bolton to Johnny Cash have all been sued for breach of copyright for allegedly stealing songs from other songwriters. These, and other cases like them, are often settled out of court. When they are litigated, however, it opens up a fascinating discussion about art and originality. Take the case of The Chiffons vs. George Harrison, in which the 1960s girl group sued the Beatle for allegedly cribbing the melody for his 1971 solo hit “My Sweet Lord” from their 1962 hit “He’s So Fine.” The judge finally ruled that George Harrison was guilty of “subconscious plagiarism” and Harrison was forced to pay over a half million dollars to the plaintiffs.

This case points to the complex relationship between influence and imagination in pop music and in art in general. Most often same songs find themselves somewhere in between conscious cover and criminal copyright infringement in the ungoverned territory of imitation and inspiration.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Just last month, we saw a dramatic illustration of this. During rehearsals in Tel Aviv for her worldwide tour, Madonna was secretly recorded performing a mashup (a seamless aggregation of two songs) of her 1989 hit “Express Yourself” and Lady Gaga’s doppelganger hit from 2011 “Born This Way.” (The clip has since been removed by Warner Chappell (Madonna’s label) and UMPG Publishing (both Madonna and Lady Gaga’s publishing company), but you can see her performing it before a crowd here.) To drive her point home, the Queen of Pop then segued into a song from her 2008 album, Hard Candy, entitled “She’s Not Me.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Gossip sites were quick to pick up on this diva dust-up and millions watched the clip on YouTube. Gaga responded with incredulity, saying she considered Madonna an inspiration but the song as wholly her own. “It sometimes makes people feel better about themselves to put other people down or make fun of them or maybe make mockery of their work,” the 26-year-old singer told a crowd in New Zealand while on her own world tour. “And that doesn’t make me feel good at all.”

For her part, the 53-year-old Madonna was at first flattered — “What a wonderful way to redo my song” — then indignant to discover that “Born This Way” was far from a cover. “When I heard it on the radio,” Madonna told ABC’s Cynthia McFadden, “I said that sounds very familiar. It feels reductive.” Perhaps she meant derivative, and it certainly is… in part. Listen to the two hooks and one hears a near note-for-note recapitulation in the vocal melodies. But that is where the similarities — striking though they are — end.

That some people talk about “Born This Way” and “Express Yourself” as the same song says at least as much about how we listen to pop music as it does about the songs themselves. It demonstrates our unconscious emphasis on chords and harmonies over rhythms. Rhythmically, the songs couldn’t be more different. The vocal lines too stand out as distinct, save for those few precious seconds of Gaga’s imitation.

Madonna is upset that Gaga’s song was neither a strict cover nor enough of a theft to be a breach of copyright. Appropriately, then, she responded with a mashup that morphs into a cover that morphs into an outright complaint. For the rest of us, though, the similarities in the two songs speak to a much more fundamental fact about how we listen to music. Madonna struck upon a catchy hook, the echoes of which help propel Gaga’s tune to pop success some twenty years later. What matters is the pattern.

Humans are pattern-seeking creatures. All music, pop music perhaps most especially, plays into our desire to find patterns with its hooks and straight-forward melodies and harmonies. But pattern alone is not enough. We thrive equally upon surprise. We want familiarity, but with just enough difference. We want to be reminded of a strain of music locked somewhere in the recesses of our mind even as we the song takes us in a new direction.

As a consequence, pop music relies upon the slippery state of influence that set Madonna and Lady Gaga on a sonic collision course. The resulting tension opens up questions about originality and influence, art and authenticity, and the nature of voice.

Same song? Perhaps. But, then again, who cares? In this age of hip hop, with its complex sampled soundscapes and lyrical allusions, it should now be a given that great music need not be made solely of new parts. It never really was. From the start, pop has been the music of remixing and repurposing, of parody and pastiche. Baby, it was born this way.

Adam Bradley is an associate professor of English at the University of Colorado, Boulder and the author or editor of several books. He is presently at work on a study of popular song lyrics. He recently contributed an article on hip-hop to the Oxford African American Studies Center.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

June 18, 2012

Can a child with autism recover?

The symptoms of autism occur because of errors, mostly genetic, in final common pathways in the brain. These errors can either gradually become clinically apparent or they can precipitate a regression, often around 18 months of age, where the child loses previously acquired developmental skills.

Can a child harboring such a genetic error ever recover? The answer in each case depends upon a combination of educational and medical factors. Because there are so many different underlying disease entities, each of which has a subgroup of children with autistic features, there are a great variety of clinical patterns seen in autism. There are children who recover spontaneously, children with temporary reversibility of symptoms, children who have major recovery or improvement due to intervention, and children who do not respond to currently available treatments. If possible, it is relevant to identify the underlying disease entity; for example, there is spontaneous recovery seen in the dysmaturational/Tourette autism syndrome. New approaches are revealing the autistic features and underlying diagnosis in younger and younger children. However many children with autism have yet to receive an underlying diagnosis.

Can a child harboring such a genetic error ever recover? The answer in each case depends upon a combination of educational and medical factors. Because there are so many different underlying disease entities, each of which has a subgroup of children with autistic features, there are a great variety of clinical patterns seen in autism. There are children who recover spontaneously, children with temporary reversibility of symptoms, children who have major recovery or improvement due to intervention, and children who do not respond to currently available treatments. If possible, it is relevant to identify the underlying disease entity; for example, there is spontaneous recovery seen in the dysmaturational/Tourette autism syndrome. New approaches are revealing the autistic features and underlying diagnosis in younger and younger children. However many children with autism have yet to receive an underlying diagnosis.

Regarding education, there are several different educational approaches to teaching young children with autistic features. Since autism encompasses so many different genetic errors and disease entities, an instruction program needs to be created for each child individually, taking weaknesses and strengths into consideration. The successful ones share the following features: (1) Starting as young as possible as soon as the autism diagnosis is given and (2) Having a significant amount time spent by the child one-to-one with the teacher. The children need a basic emphasis on learning social and language skills. The majority of individuals with classic autism also suffer from intellectual disability, so many children need additional help with cognitive advancement. To supplement the educational program, control of anxiety and improving the ability to focus are often indicated yet not always achievable.

Regarding medical therapies, attempts to medically treat all individual with autistic features with one drug has generally been a failure. However therapy for some non-core symptoms of autism, such as seizures, can be efficacious. Currently under intensive study with some limited therapies available are sleep disorders, food and gastrointestinal problems, and self-injurious behavior.

There are a few, extremely rare, known etiologies of autistic behavior where established medical/neurosurgical therapies already exist. These include biotinidase deficiency, creatine deficiency syndromes, dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, phenylketonuria, and Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome.

Thanks to DNA/RNA studies, hope for future treatments is now on the horizon due to the creation of rodent models of the disease entities with autistic subgroups. Although mice are not humans, there is a chance that the effectiveness and possible side-effects of putative therapies in these animals may become relevant. Such models already exist for Angelman syndrome, deletion 22q13.3 syndrome, fragile X syndrome, myotonic dystrophy type 1, neurofibromatosis type 1, PTEN disease entities, Rett syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis. Preliminary reports of therapeutic trials in some of these rodent models are promising and may extend to human clinical trials.

In the end, one of the most important interventional aspects in the field of autism and related disorders is the change of societal attitudes. Acceptance, understanding, and support for these children and adults with autism has been slow in coming, but largely thanks to a number of strong and amazing parents it’s underway.

Mary Coleman MD is Medical Director of the Foundation for Autism Research Inc. She is the author of 130 papers and 11 books, including six on autism. Her latest book is The Autisms, Fourth Edition co-authored with Christopher Gillberg MD. Read her previous blog post “Is there an epidemic of autism?”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers