Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1048

June 25, 2012

Off the Road

Three weeks come and gone, and what do we have to show for it? Not quite 6000 new miles on the odometer. A nice, even tan across parts of my head that, in earlier years, never knew sunlight. Eleven orphaned socks. A fuel pump that wouldn’t survive the Continental Divide. Me, I’m rethinking life on the road.

The idea (my wife’s) was nothing if not efficient: the kids get their Great Western Adventure, I promote my new book, The Day in Its Color, and together we look closely at the changes that have unfolded in an American landscape documented by amateur photographer Charles Cushman, during his travels from 1938 to 1968.

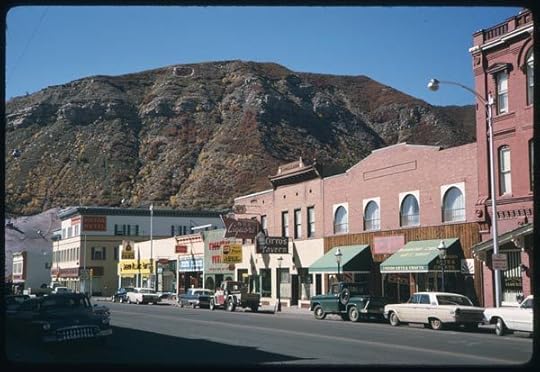

Main Ave., Durango, Colorado, 1965. Charles Cushman Photograph Collection, Indiana University.

Main Ave., Durango, Colorado, 2012. Photo by Eric Sandweiss.

Safely home, let’s review the the score sheet:

Family Enrichment: “What’s the Internet password?” is the new “Are we there yet?” The Grand Canyon could be a pretty cool place if they got decent wifi on the North Rim.

Book Promotion: Selling books is a handcrafted, one-on-one operation — like selling roses on street corners or seeking quarters for a cup of coffee. It promises profits at a similar scale.

Changes in the Land: The geological epoch of 1938-2012 has brought little change to the countours of mountainsides and valleys. Here in the world of human life-spans, small towns have either decided to attract new business by dressing themselves up to look like small towns or have withered from indifference. Central cities worked better seventy years ago, when there was plenty for bums to do, than today, when there’s not (the bums are still there, in any case, looking for something to do).

Not a bad tally of lessons learned, all in all. But the least expected insight from this multi-purpose trip is perhaps the hardest to swallow. Having traveled about one percent of the distance covered by Cushman and his wife Jean in their decades on the road, I’m already reminded of how much more of their lives yet remains hidden behind the seeming plenitude of his photographs. It’s a long, long day that yields a handful of images. Surrounding the few fractional seconds required for those pictures lie million more uncaptured images of the world that presses in on us hour after hour: pills on the sink; a used towel on the bathroom floor; the gas pump; the wrong turn; unspoken words in an unwinnable argument; the gas pump; the static on the radio; the gas pump. Do we want to remember these images? No. Do they dominate our actual experience? Absolutely.

Charles and Jean Cushman never had audio books, but my family and I allowed ourselves this modern indulgence. One of the titles we chose for the trip was Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. Thirty-five years after my first encounter with the epic, Kerouac’s prose struck me tiresome, endless — in his own word, “beat.” The narrated book unfolded in our car as if in real time, rarely omitting a bump on the road or a morning coffee break. This was part of the novelist’s point, of course: hold up a mirror to life, capture as spontaneously as possible the fullness (and even weariness) of the long journey without pausing for selection, reflection, interpretation.

Main Ave., Durango, Colorado, 1965. Charles Cushman Photograph Collection, Indiana University

Main Ave., Durango, Colorado, 2012. Photo by Eric Sandweiss.

Charles Cushman was no Kerouac, no Robert Frank. Like other amateur artists, he dared not lay his life bare for a public audience, never thought to expose some hidden essence of his soul or his world. Instead, he carefully curated himself, selecting tiny fragments of experience for posterity, burying the rest from others and, probably, himself. Through his rangefinder, he sought out what the poet Wallace Stevens (like him, a man of the nine-to-five world) called “the day in its color”: the limited world as it presents itself to our imperfect senses.

Finally pulling off the road, I am beginning to appreciate not so much how a prolific artist puts together that world, but the care with which he conceals all that lies behind it. Knowing what to leave out is as exacting and exhausting a skill as deciding what to put in. Charles Cushman — a man of many images and almost no words — has, I believe, left out a great deal. His photographs, for all their color, are all that remains to our imperfect senses of a life as full and as mysterious as any.

Eric Sandweiss is Carmony Professor of History at Indiana University. He is the author of The Day in Its Color: Charles Cushman’s Photographic Journey Through a Vanishing America, co-author of Eadweard Muybridge and the Photographic Panorama of San Francisco (winner of Western History Association’s Kerr prize for best illustrated book), and author of St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape. Read his previous blog posts “Charles Cushman and the discovery of Old World color,” “Bits and Pieces of the Mother Road,” and “Kodachrome America.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art & architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Most older pedestrians are unable to cross the road in time

The ability to cross the road safely is important for the health of older people. Those who cannot cross the road safely are less able to access to the shops, health services, and social contacts they need to stay healthy. The feeling that they will not be able to reach the other side of the road in time can deter older adults from even going out at all. People who live in pedestrian-friendly neighbourhoods are more likely to go by foot, which benefits their physical health. Having enough time is vital for crossing the road safely.

Did you know that UK pedestrian crossings require a minimum walking speed of 1.2m/s (2.7miles/hr)? On pelican crossings, the time given for the ‘clearance’ period (between the solid green man and the red man) assumes that pedestrians can walk at at least 1.2 m/s. In a recent research project, we used data from the Health Survey for England (HSE) to determine the proportion of people over 65 who are able to walk at 1.2m/s or faster. HSE is an annual survey of a nationally-representative sample of adults and children in England. Unlike previous studies, participants were not excluded on the basis of having poor health or being disabled. This means for the first time we have an accurate picture of the walking speed of the general older population who may wish to use a pedestrian crossing.

We found that the average walking speed in those over 65 years was 0.9m/s in men and 0.8m/s in women, with a decrease in speed as age increased. This means that average walking speed in older men and women was below the speed required to use a pedestrian crossing in the UK and many other countries. 84% of men and 93% of women over the age of 65 either could not walk eight feet safely or their normal walking speed was less than 1.2m/s. Our findings are consistent with studies in Ireland, the USA, South Africa, and Spain, and show that the majority of older pedestrians have insufficient time to use pedestrian crossings. We also found that women, smokers, those with poor health, and those living in deprived areas were more likely to have problems with walking safely or fast enough.

We found that the average walking speed in those over 65 years was 0.9m/s in men and 0.8m/s in women, with a decrease in speed as age increased. This means that average walking speed in older men and women was below the speed required to use a pedestrian crossing in the UK and many other countries. 84% of men and 93% of women over the age of 65 either could not walk eight feet safely or their normal walking speed was less than 1.2m/s. Our findings are consistent with studies in Ireland, the USA, South Africa, and Spain, and show that the majority of older pedestrians have insufficient time to use pedestrian crossings. We also found that women, smokers, those with poor health, and those living in deprived areas were more likely to have problems with walking safely or fast enough.

Insufficient crossing time amongst older adults may not increase the risk of pedestrian fatalities, which are uncommon at pedestrian crossings. However, it is likely to deter this group from even trying to cross the road. For older people, maintenance of mobility outside the home not only has direct health benefits, but is also an important way to maintain independence and social networks. Physical activity in older people may depend on the ability to negotiate their local environment, including crossing the road safely. The groups we identified as most likely to have walking impairment are also those least likely to have access to other, more expensive, forms of transport. The negative health impacts of inappropriate crossing timings may therefore be greatest amongst more deprived groups.

Where there are a large proportion of older residents, adjustments are made to the pedestrian crossing times to allow for this. However older pedestrians should be able to use pedestrian crossings safely wherever they go.

Promotion of physical activity is a public health priority for people of all ages and transport planning should reflect this. Furthermore, travelling by foot instead of by car is better for the environment. Transport planning should encourage walking activity; current pedestrian crossing timings may actually put people off walking.

The assumed ‘normal’ walking speed of 1.2m/s is utilised internationally as the basis for pedestrian crossing timings, yet the origin of this assumed speed is not clear. Ultimately, this excludes most of the older population in England (and elsewhere) from using pedestrian crossings: it needs revision if we are to create a healthy and inclusive environment for people of all ages. Our results show that assuming a walking speed of 0.8m/s may be more appropriate for pedestrian crossings, as this would allow the ‘average’ man or woman over 65 years sufficient time to cross.

Dr Laura Asher is a specialty registrar on the public health training scheme and academic clinical fellow at the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health at University College London. Her research interests include transport and health and mental health. She is co-author of Most older pedestrians are unable to cross the road in time: a cross-sectional study along with Maria Aresu, Emanuela Falaschetti, and Jennifer Mindell. The paper has been published by Age and Ageing journal and is freely available for a limited time.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

June 24, 2012

Pablo Picasso gives first exhibition outside Spain

24 June 1901

Pablo Picasso gives first exhibition outside Spain

On 24 June 1901, two Spanish artists joined in an exhibition of their works at the Paris gallery of Ambroise Vollard. One of these artists was Francisco Iturrino, who had lived off and on in Paris since 1895 and whom Vollard had mentored. The other was a not-yet-20-year-old named Pablo Picasso, who had been befriended by Iturrino and the gallery owner.

Portrait of Pablo Picasso by Juan Gris, 1912. The Art Institute of Chicago. Source: Wikipaintings.

The exhibition marked the first public display of Picasso’s work outside Spain (some of his work had been shown in Barcelona the year before). Impressed by the painter’s talent, French writer Max Jacob struck up a friendship. Critic Félicien Fagus commended the young Picasso in his review of the show. Ironically, the commentator cited the influence of several other artists and remarked that the painter’s “capacity for enthusiasm has left him no time to develop a style of his own.”Picasso would soon prevent any other critics from making such a claim. The death of his close friend Carles Casagemas later in 1901 led to a deep sadness that helped produce Picasso’s Blue Period, three years marked by brooding canvases and somber tones.

During this time, after traveling back and forth between Spain and Paris, Picasso settled permanently in the French capital. There he befriended avant-garde artists such as Jacob; French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who became a roommate; American writer Gertrude Stein; and Georges Braque.

It was 1907, when he completed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Women of Avignon), that Picasso put a truly distinct stamp on his art. While he didn’t show the work publicly, it represented his probing experimentation with form and presentation. Over the next few years, he worked closely with Braque to develop Cubism, revolutionizing art.

Picasso went on to a long and brilliant career, becoming the most renowned and influential painter of the twentieth century. And it all began in that small exhibit in 1901.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

Sir Robert Dudley, midwife of Oxford University Press

The life of Sir Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester (1532-1588) was every bit as opulent and complex as one of the grand dresses in which Elizabeth I was pictured wearing in her pomp, a Gloriana presiding over the vast hive of the Tudor court. Dudley knew that hive inside out: its drones, its honeyed talk and the potentially lethal stings of its intrigues, and most of all its Queen. Perhaps the most ambiguous figure in English royal history, Dudley was more than a friend but less than a full consort to his virgin monarch, a male confidant on intimate terms with the most powerful woman of her age. That his first wife had died in odd circumstances made the warmth and depth of this long friendship with Elizabeth all the more questionable. Given the queasy political climate of 16th century England, however, some things were better left unsaid. The Earl had influence, and didn’t hesitate to use it: more than one of his adversaries or associates ended up on the scaffold, including Mary, Queen of Scots. To prosper at Elizabeth’s court one needed the sweetness of a lawyer and the sharpness of hawk, and Dudley had both. “I stand at the top of the hill,” he wrote in 1576, “where I know the smallest slip semeth a fall.”

Procession portrait of Elizabeth I of England, circa 1600. Attributed to Robert Peake the Elder.

Nor did the demands on him lessen with age. In his last months, Dudley was at the heart of the preparations to repel the Spanish Armada, and arranged the queen’s extraordinary visit to Tilbury docks to mark its defeat. He was Elizabeth’s arch favourite and Master of Horse, a stoic and dainty campaigner who triumphed where others often quailed or stumbled over court intrigue. More benignly, he also used his influence to become a patron of the arts. It was in this capacity that Dudley has some claim to being the founding father — or, more accurately, the midwife — of Oxford University Press.

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, circa 1560s, by Steven van der Meulen. Source: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Appointed Chancellor of the University in 1564, Dudley spearheaded moves by Oxford to revive and formalise its printing. Printers had operated sporadically with university support since the late 15th century, but Tudor law moved against such liberty, curbing satire or works deemed heretical under the new order of Protestant rule. Printing became governed through the Stationers’ Company in London. Any other body had to petition for a license from the Crown, and that included the two universities. Cambridge made separate arrangements. In Dudley, Oxford possessed the perfect emissary for its own negotiations.Accordingly, in 1584 he was presented with a Latin “Supplication,” a brief to argue Oxford’s case with Elizabeth. Presumably drafted by an academic committee, the document makes interesting reading. For one thing, it’s an early example of Oxford’s renowned ivory tower vagueness. It cites the precedent of “a man living in Oxford fifty years ago, more or less, who used to print books”: an impression is instantly conjured up across the centuries of an august university don trying to recall some jolly tradesman in a rather obscure nook of the city. More seriously, the document also parades the Renaissance ideal of modern scholarship nourished by wisdom from a bygone age. European thought had considered it “self-evident that where there is a settlement of scholars, there should be printers, so that books can be printed … and texts most carefully collated.” A sanctioned press at Oxford would rescue “very important manuscripts foully beset by dust and rubbish” in the university’s libraries, employing English scholars to prepare new editions and so — changing the emphasis of the appeal — “blot out the charge of laziness brought against them by foreigners.” Moreover, the new printing business would provide “pure streams of improved literature” to displace “frivolous trifles,” improving the cultural life of “England, Wales, and the hitherto barbarous realm of Ireland.” Tellingly, these clauses were designed to appeal to Elizabeth’s patriotic sentiment at a time of great national uncertainty, and its framers seemed to take their success as a foregone conclusion. The text closed with a nod to fait accompli: “God prosper it!”

Their confidence was well-founded. Although Dudley obtained no official charter, Elizabeth apparently brushed aside the “Supplication” as a mere formality. Oxford moved into legally recognised printing work within months, whereas Dudley himself became entangled in the Dutch Revolt against Spain. It seems that he contracted a serious illness in the Netherlands, probably malaria. That infection proved fatal. Shortly after the defeat of the Armada, Dudley died at Cornbury in Oxfordshire — by coincidence, the future home of another Chancellor, the Earl of Clarendon, whose name was also to become associated with the Press. Though neither he nor Elizabeth lived to see it, Oxford’s printing did indeed prosper, and the sense of their own close relationship passed into folk-lore and literature. To take only one example, when T.S. Eliot decided to “do the police in different voices” and capture London as a fractured chorus of disappointment in the cut-up images of in The Waste Land (1922), he had Elizabeth and Dudley haunt the Thames on the royal barge, an apparition which could easily be imagined during the grand flotilla which has just marked the Diamond Jubilee of the present Queen. Their ghosts would no doubt be confused or distressed by much today — yet both Dudley and his Gloriana could hardly fail to be astonished by Oxford University Press. The press they helped to found has not only survived and matured, but now flourishes on an unprecedented scale around the world in this, the second Elizabethan age.

Dr. Martin Maw is the Archivist of Oxford University Press. Visit the Oxford University Press Archive online and visit the museum by appointment.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

June 22, 2012

Five things you can do about multiple sclerosis

First, the bad news. Multiple Sclerosis (MS), is a chronic, incurable, often progressive, and unpredictable neurodegenerative condition. The good news is that in the 21st century, with early diagnosis, prompt treatment, and numerous options for treating the disease and its symptoms, most people who are diagnosed nowadays can expect to lead full functional lives with MS mostly being a nuisance, rather than a source of significant permanent disability. Here are five basic strategies for not letting MS get the better of you.

1. Get smart! The best weapon against MS (or any disease) is information. What you don’t know really can hurt you. Talk with your physician and other health care professionals, and take advantage of printed matter, websites, webinars, and seminars sponsored by professional organizations such as the American Academy of Neurology, and voluntary health organizations such as the National MS Society. Information from these sources are vetted, accurate and reliable, which isn’t true of everything on the Internet. With this knowledge, you’ll have a better handle on what symptoms to watch out for, what your treatment options are, resources that are available in your area, etc. You can also find out how to access MS specialty care near you.

2. Partner with your neurologist. Gone are the days when doctors dictated how a patient’s health care would be conducted and the patient was merely a passive consumer. People with MS need to be involved in their treatment plan and actively decide what options they would like to pursue. This is because the most effective treatment for you is the one that best meets your specific needs. Be truthful when speaking to your doctor; he or she is only as good as the information they receive. For example, tell your doctor about any non-prescription supplements, vitamins, herbs, or other substances you are taking. Ask questions so you can make informed decisions. When possible, bring a partner or friend to doctors’ appointments you can be sure that all the important issues are asked about and answered.

3. Take responsibility for your health. The best medical advice in the world won’t do you any good if you don’t adhere to it. Keep regular doctor’s appointments instead of just going to the doctor when there is a problem. Try to note early symptoms that might signal an oncoming exacerbation or pseudoexacerbation (an exacerbation due to something such as an infection). Be conscientious about taking medications and following other instructions. If a medication produced a side effect or just wasn’t working, let your doctor know instead of just stopping it and not informing them. Optimal treatment for MS involves medications for both symptoms and disease modifying therapy. The former will make you feel and function better; disease modifying therapies help reduce the occurrence of relapses and new areas of nerve damage. Build a health care team. You and your neurologist can’t do it all by yourselves. Other health care professionals such as nurses, rehabilitation specialists, psychologists, other physicians (e.g. urologists) are invaluable in optimizing your care. Other professionals, such as vocational rehab experts and legal advisors, help you deal with issues such as health care directives and estate planning.

4. Live the good life. As science is elucidating more about the underlying mechanisms of MS, it is also becoming increasingly clear that lifestyle choices affect the disease substantially. While there are no dietary regimens that have been proven to modify the course of MS, a “healthy’ diet (one containing abundant amounts of fruits and vegetables, lean proteins, complex carbohydrates and polyunsaturated fats) will promote general good health and help to prevent common comorbid conditions such a hypertension and diabetes. Additionally while no vitamin or supplement has been proven to be beneficial in treating MS, data suggest that Vitamin D may be important in management and that low Vitamin D levels may increase the chance of a relapse. Ask your doctor about monitoring Vitamin D levels and what amounts of supplementation of this vitamin are appropriate. Another lifestyle choice that can affect MS is smoking. Smoking has been shown to increase the chances of MS progression and of course can cause other health problems.

5. Move it! Exercise really is your friend. Not only does regular exercise have the same health benefits for persons with MS as it does for people in general (increasing cardiovascular and respiratory fitness and bone health), but exercise has been shown to lessen some MS symptoms such as fatigue and depression, as well as increase muscle strength and flexibility. Additionally, data in animal models and a few human studies suggest that exercise might possibly ‘treat’ MS by increasing anti-inflammatory substances and increasing some nerve growth factors. So talk with your doctor or physical therapist about an exercise regimen that is right for you.

There’s certainly no good time to be diagnosed with MS, but now is a hopeful time with strategies that can help minimize the impact of MS, effective medicines that are available now, and new and more powerful treatments soon to come.

Dr. Barbara Giesser is a Clinical Professor of Neurology and Clinical Director of the Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Program at UCLA. She is the editor of Primer on Multiple Sclerosis. She has been specializing in caring for persons with MS since 1982. In addition to her clinical and research activities, Dr. Giesser has been active in educational and advocacy efforts through her work with organizations such as the National MS Society and the American Academy of Neurology. Watch Dr. Barbara Giesser interviewed on Extra.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only article on health and medicine on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Computers as authors and the Turing Test

Alan Turing’s work was so important and wide-ranging that it is difficult to think of a more broadly influential scientist in the last century. Our understanding of the power and limitations of computing, for example, owes a tremendous amount to his work on the mathematical concept of a Turing Machine. His practical achievements are no less impressive. Some historians believe that the Second World War would have ended differently without his contributions to code-breaking. Yet another part of his work is the Turing test — Turing’s answer to a momentous question: What’s essential about human intelligence?

The inspiration for the Turing test came from a conversation game in which one player (the deceiver) tries to fool another player (the detective) about the deceiver’s gender. To win, a male deceiver would need to answer the detective’s questions in a way that suggests that he, the deceiver, is female. It doesn’t suffice for the deceiver to answer direct questions about gender. He should also show good knowledge about feminine topics and get properly upset over male chauvinism. What’s more, he should use turns of phrase that are typical of women. All this without overdoing it, of course.

The inspiration for the Turing test came from a conversation game in which one player (the deceiver) tries to fool another player (the detective) about the deceiver’s gender. To win, a male deceiver would need to answer the detective’s questions in a way that suggests that he, the deceiver, is female. It doesn’t suffice for the deceiver to answer direct questions about gender. He should also show good knowledge about feminine topics and get properly upset over male chauvinism. What’s more, he should use turns of phrase that are typical of women. All this without overdoing it, of course.

Turing realised that this conversation game could be turned on its head if the role of the deceiver is played by a computer, not a person. The task for a computer deceiver is to fool the detective into believing that the deceiver is a person of flesh and blood. Analogous to the original game, the computer can win by thinking like a human. Now suppose that, playing this modified game, a computer was able to fool human detectives into believing it to be human. (A deceiver wins if the detectives are unable to get the computer/human decision correct more often than would be expected by chance.) Surely, so Turing argued, this would mean that the computer has managed to think like a human. Hence, if this happened, one would have to conclude that the computer displays real human thinking; the makers of the deceiver program would have captured human intelligence. The link between the Turing Test and intelligence has often been questioned, but the idea of the Test itself is very much alive.

Natural Language Generation (NLG) systems are computer programs that convert numerical or symbolic information into ordinary language. Weather forecasting, medical decision support, and other applications are starting to use systems of this kind. How should NLG programs be tested? No single method has all the answers, but human behaviour is still a gold standard to which many of these systems aspire. As in the Turing Test, researchers try to make their NLG systems produce text that resembles human-written text, partly because they believe that this may be the shortest route to making them effective. More and more often, NLG systems are tested in international evaluation contests that focus on one or more particular aspects of language use.

One of the most important challenges for NLG is to let computers talk in a human way about numbers. Numbers play an important role in many areas, including the medical domain. When nurses write about a patient — producing a shift report for instance — they have many numbers at their disposal (body temperature, oxygen saturation rates, etc.). However, they frequently suppress these numbers, replacing them by terms that are qualitative and vague. Instead of citing concrete oxygen saturation figures, they simply write “The SATS have remained OK”, for example. When talking about episodes of decreased heart rate, they throw in words like “temporary,” “prolonged,” and “significant.. Interestingly, doctors suppress numbers even more than nurses. Computational NLG systems in this area, by contrast, tend to stick with the numbers, producing stilted bits of text like the following: “By 10:40 SaO2 had decreased to 87. As a result, Fraction of Inspired Oxygen (FIO2) was set to 36%. SaO2 increased to 93.” The challenge is to do better, emulating human writers.

Unfortunately, the writings of doctors are rather difficult to mimic. The challenge is not just to decide when numerical information is useful. (Texts written by doctors contain numbers too, though fewer.) The hardest challenge for the NLG system is to “interpret” the numbers and this can involve difficult judgment calls, deciding whether a certain pattern of numbers should be summarized as “OK,” for instance, and deciding whether an episode of slow heart rhythm is merely “temporary” or “prolonged.” The medics’ texts are not dumbed-down versions of the computer-generated ones. They are highly sophisticated, despite their apparent simplicity. It will take research in NLG years before its computer programs stand a chance at winning a Turing Test in this area.

Kees van Deemter is a Reader in Computing Science at the University of Aberdeen. He is interested in getting computers to speak or write, and in the logical, linguistic, and philosophical issues that this raises. He is the author of approximately 120 peer-reviewed research publications. His book, Not Exactly: In Praise of Vagueness, puts the spotlight on vague and qualitative concepts, viewing them from a variety of angles and making a highly technical literature easily accessible to a wide audience. It explores how vague and qualitative concepts play a role in all areas of life, including even the exact sciences, where they are mostly unwelcome; how vague concepts fit into our current understanding of language and logic; the practical applications; and when and why vague language can be effective.

OUPblog is celebrating Alan Turing’s 100th birthday with blog posts from our authors all this week. Read our previous posts on Alan Turing including: “Maurice Wilkes on Alan Turing” by Peter J. Bentley, “Turing : the irruption of Materialism into thought” by Paul Cockshott, “Alan Turing’s Cryptographic Legacy” by Keith M. Martin, and “Turing’s Grand Unification” by Cristopher Moore and Stephan Mertens.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

June 21, 2012

Healing American Health Care

One hundred years ago the fledgling American Medical Association (AMA) and the Carnegie Foundation joined in an effort to redress the wretched state of medicine in America. Its scientific value was meager, but more important was its status as a huckster enterprise. The AMA and Carnegie sought out Abraham Flexner, a young John Hopkins graduate educator, to lead the examination. The resulting Flexner Report is widely regarded as the single most important document in the history of current medicine. Its scathing content targeted practice, training, and process. Ninety-one of the diploma mills were driven out of existence. A new model based on the Johns Hopkins example was made the prototype.

A century after this reformulation, an immense gain in medical science is in hand. Yet the medical profession again receives failing grades. It is bankrupting, unfair, dangerous, corrupt, inefficient, inconsistent, and irrelevant; it confounds our leaders. We must call for a new Flexner Report.

Thomas Kuhn, the historian from the University of Chicago, observes in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions that in order to abet a true revolution, two prerequisites must be obtained. First, there must be a general agreement among the aggrieved parties that a change is demanded. (Appeasement is futile.) Second, there must be a new paradigm available of sufficient dimension and power to replace the failing model.

For medicine, there is a growing agreement that revolution is required. Doctors and patients, labor and industry, Democrats and Republicans, the meek and the mighty, are a chorus of distress. On a recent Stanford visit, Peter Orzag said that in order for America to get on with the rest of its business, it must have a major resolution of the health care mess. The first revolutionary requirement is fulfilled.

But even more importantly, there is for the first time in history, a sturdy replacement paradigm. Our system must be framed around health, rather than disease, active rather than reactive. We know with precise metrics the determinants of health, just as we know the much more extensively studied determinants of disease. The exposition of health is immensely empowering because it validates the supremacy of prevention over repair as medicine’s MO. Heart disease, diabetes, cancer, frailty, and AIDS are rarely curable, but are securely preventable, which is vastly cheaper, fairer, and more relevant. Kuhn’s required replacement paradigm becomes “Health instead of disease, prevention instead of repair — Next Medicine.”

Current medicine fails its mission — a square peg for a round hole. Its current tools of surgery, technology, and pharmacy make little dent on the overwhelming confrontations of diabetes, obesity, and aging. It is irrelevant to the societal need. The CDC posits that ours is the first generation in the history of our republic when the children will live less long than the parents.

Health illiteracy is our biggest problem and the current model of repair cannot address this because it pays. Fully 60% of our annual medical expense of $2.7 trillion is attributable to behaviors that are preventable — nurture, not nature. Capitalism is not the problem, but its product is illness instead of wellness. The service fee model embraces sickness.Perverse incentives now prevail.

We must incent health instead of disease. We must embrace prevention instead of repair. Health must pay. Medicine’s primary job — read Asclepius and Hygeia — is health. Doctor, from docere, to teach. Learn it. Teach it. Live it. Save trillions.

Walter Bortz II, M.D., is Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine at the Stanford School of Medicine. He is the author of Next Medicine: The Science and Civics of Health, We Live Too Short and Die Too Long: How to Achieve and Enjoy Your Natural 100-Year-Plus Life Span, and Living Longer for Dummies. An authority on aging, he is also a marathon runner.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Chinese Empress Cixi declares war on foreigners

21 June 1900

Chinese Empress Cixi declares war on foreigners

On 21 June 1900, in the midst of anti-western attacks in China, the Dowager Empress of China, 65-year-old Cixi, tried to seize the chance to restore Chinese authority and declared war on all foreigners.

The conflict had been decades in building. Throughout the nineteenth century, western powers and Japan had carved up China, creating their own zones where they effectively ruled and where their nationals enjoyed privileged status. Weakened by obsolete technology and its own internal problems, China could do little to resist. China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese War in the middle 1890s underlined the nation’s weakness.

Thousands of frustrated Chinese joined a secret group called the Yihequan (“Righteous and Harmonious Fists”). The Boxers (as this group was called in the West) became more aggressive against foreigners, attacking westerners. As they abandoned another of their goals (overthrowing the imperial dynasty) and focused on anti-western attacks, the government edged toward accepting them.

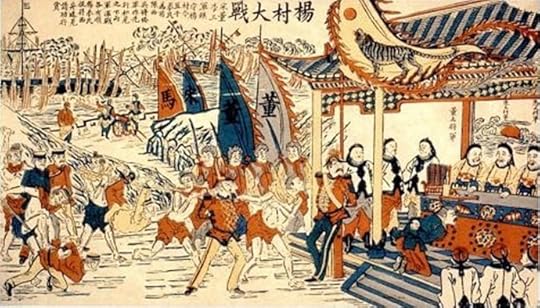

Chinese nianhua painting of Eight-Nation Alliance officers being captured by Chinese General Dong Fuxiang during the Battle of Yangcun in the Boxer Rebellion. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In January of 1900, Cixi ended the policy of suppressing the Boxers, an action that drew foreign protests. In June, Boxers and imperial troops began attacking foreign interests in Beijing and elsewhere. On 20 June, Boxers stormed the German embassy and killed the German ambassador. Other western diplomats huddled for safety in their legations in Beijing, besieged by hostile Chinese.

The next day, Cixi issued her declaration of war. Foreigners were not the only target of the Boxers — thousands of Chinese Christians were killed across China. Unfortunately for the imperial family, the effort to expel the foreigners failed as some provincial governors refused to cooperate.

In the middle of August, a foreign military force finally reached Beijing, defeated the Boxers, and liberated the trapped diplomats. The foreign troops then rampaged through the city, seizing valuables and destroying property. Cixi and the imperial court fled for safety. The fighting finally ended and the empress was forced to accept the foreigners’ conditions for peace the following year.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

Turing’s Grand Unification

Many of the central moments in science have been unifications: realizations that seemingly disparate phenomena are all aspects of one underlying structure. Newton showed that the same laws of motion and gravity govern apples and planets, creating the first explanatory framework that joins the terrestrial to the celestial. Maxwell showed that a single field can explain electricity, magnetism, and light. Darwin realized that natural selection shapes all forms of life. And Einstein demonstrated that space and time are shadows of a single, four-dimensional spacetime.

This quest for unity drives us to this day, as we hunt for a Grand Unified Theory that combines gravity with quantum mechanics. But while it is less well-known, computer science had its own grand unification in 1936, thanks to Alan Turing.

At the dawn of the 20th century, mathematicians and logicians were focused on the axiomatic underpinnings of mathematics. Shaken by paradoxes — like Russell’s set of all sets that don’t contain themselves (does it or doesn’t it?) — they wanted to re-build mathematics from the ground up, creating a foundation free of paradox. This stimulated a great deal of interest in axiomatic systems, their power to establish truth, and the difficulty of finding proofs or disproofs of open questions in mathematics.

In 1928, David Hilbert posed the Entscheidungsproblem, asking whether there is a “mechanical procedure” that can decide whether or not any given mathematical statement is true — say the Twin Prime Conjecture, that there are an infinite number of pairs of primes that differ by two. Such a procedure would complete the mathematical adventure, providing a general method to determine the truth or falsehood of any statement. To us, this sounds horribly final, but to Hilbert it was a glorious dream.

But what exactly is a “mechanical procedure”? Or, in modern terms, an algorithm? Intuitively, it is a procedure that can be carried out according to a fixed computer program, like a recipe followed by a dutiful cook. But what kinds of steps can this computer perform? What kind of information does it have access to, and how is it allowed to transform this information?

Several models of computation had been proposed, with different attitudes towards what it means to compute. The recursive functions build functions from simpler ones using rules like composition and induction, starting with “atomic” functions like x+1 that we can take for granted. Another model, Church’s λ-calculus, repeatedly transforms a string of symbols by substitutions and rearrangements until only the answer remains.

Each of these models has its charms. Indeed, each one lives on in today’s programming languages. Recursive functions are much like subroutines and loops in C and Java, and the λ-calculus is at the heart of functional programming languages like Lisp and Scheme. Every computer science student knows that we can translate from each of these languages to the others, and that while their styles are radically different, they can ultimately perform the same tasks. But in 1936, it was far from obvious that these models are equivalent, or that either one is capable of everything we might reasonably call a computation. Why should a handful of ways to define functions in terms of simpler ones, or a particular kind of symbol substitution, be enough to carry out any conceivable computation?

Turing settled this issue with a model that is both mathematically precise and intuitively complete. He began by imagining a human computer, carrying out a procedure with pencil and paper. If we had to, he argued, we could boil any such procedure down into a series of steps, each of which reads and writes a single symbol. We don’t need to remember much ourselves, since we can use notes on the paper to keep track of what to do next. And although it might be inconvenient, a one-dimensional roll of paper is enough to write down anything we might need to read later.

At that point, we have a Turing machine: a controller with a finite number of internal states, and a tape on which it can read and write symbols in a finite alphabet. Nothing has been left out. Any reasonable attempt to augment the Turing machine with two-dimensional tapes, multiple controllers, etc. can be simulated by the original model.

Famously, Turing then showed that there are problems that no Turing machine can solve. The Halting Problem asks whether a given Turing machine will ever halt; in modern terms, whether a program will return an answer, or “hang” and run forever. If there were a machine that could answer this question, we could ask it about itself, demanding that it predict its own behavior. We then add a twist, making it halt if it will hang, and hang if it will halt. The only escape is to accept that no such machine exists in the first place.

This also gives a nice proof of Gödel’s Theorem that there are unprovable truths, or to be more precise, that no axiomatic system can prove all mathematical truths. (Unless it also “proves” some falsehoods, in which case we can’t trust it!) For if every truth of the form “this Turing machine will never halt” had a finite proof, we could solve the Halting Problem by doing two things in parallel: running the machine to see if it halts, while simultaneously looking for proofs that it won’t. Thus, no axiomatic system can prove every truth of this form.

Turing showed that his machines are exactly as powerful as the recursive functions and the λ-calculus, unifying all three models under a single definition of computation. What we can compute doesn’t depend on the details of our computers. They can be serial or parallel, classical or quantum. One kind of computer might be much more efficient than another, but given enough time, each one can simulate all the others. The belief that these models capture everything that could reasonably be called an algorithm, or a mechanical procedure, is called the Church-Turing Thesis.

Turing drew the line between what is computable and what is not, if we have an unbounded amount of time and memory. Since his death, computer science has focused on what we can compute if these resources are limited. For instance, the P vs. NP question asks whether there are problems where we can check a solution in polynomial time (as a function of problem size) but where actually finding a solution is much harder. For instance, mathematical proofs can be checked in time roughly proportional to their length — that’s the whole point of formal proofs — but they seem difficult to find. Despite our strong intuition that finding things is harder than checking them, we have been unable to prove that P ≠ NP, and it remains the outstanding open question of the field.

The fact that Turing didn’t live to see how computer science grew and flowered — that he wasn’t there to play a role in its development, as he did at its foundations – is one of the tragedies of the 20th century. He received, too late, an apology from the British government for the persecution that led to his death. Let’s wish him a happy birthday, and raise a glass to his short but brilliant life.

Cristopher Moore and Stephan Mertens are the authors of The Nature of Computation. Cristopher Moore is a professor at Santa Fe Institute and previously, a professor in the Computer Science Department and Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of New Mexico. Stephan Mertens is a a theoretical physicist at the Institute of Theoretical Physics, Otto-von-Guericke University, Magdeburg, and external professor at the Santa Fe Institute.

OUPblog is celebrating Alan Turing’s 100th birthday with blog posts from our authors all this week. Read our previous posts on Alan Turing including: “Maurice Wilkes on Alan Turing” by Peter J. Bentley, “Turing : the irruption of Materialism into thought” by Paul Cockshott, and “Alan Turing’s Cryptographic Legacy” by Keith M. Martin. Look for “Computers as authors and the Turing Test” by Kees van Deemter tomorrow.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles on mathematics on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Downton Abbey and the Curse of King Tut

You must surely have been tempted on occasion to curse , if not for the script of Young Victoria, then for the creation of Downton Abbey, that death star of good old-fashioned aristocratic virtue and due deference. For a little while, all public debate seemed to be sucked through the funnel of Downton discourse, coinciding as it did with the election of all those shiny Eton boys to government in 2010. Fellowes has even had enough self-belief and ambition to become an aristocrat himself. He is now Baron Fellowes of West Stafford and sits on the Tory benches.

But don’t worry, he may already be cursed. It’s not just his obsession with the Titanic –- the sinking creates the opening crisis in Downton Abbey and this year he scripted ITV’s centenary mini-series. It turns out that there is another famous curse, ninety years old this year, which haunts Downton. The stately home that stands in for the Abbey is Highclere Castle, the family seat of the Carnarvons. And it was the fifth Earl of Carnarvon who sponsored the search for the tomb of Tutankhamun, found by Howard Carter in 1922. The Earl was present at the formal opening of the long-lost tomb in the Valley of the Kings in February 1923. Six weeks later he was dead, from pneumonia and blood poisoning, launching a frenzy of rumours and a host of mysterious deaths — allegedly. At Highclere, it was said the Earl’s three-legged dog Susie howled in misery and died at the precise moment of her master’s death. The sixth Earl, the surviving son, recalled all sorts of spooky events in the castle around his doomed father’s Egyptian adventure. There were séances and premonitions by fortune-tellers and Spiritualist mediums.

The Curse of King Tut was a monster bolted together by the tabloid press in the 1920s. It has often been called the first global media sensation, although it surely was not. But because rumours can never be denied, only ever more elaborated upon, the curse has proved remarkably persistent, evolving over the decades, claiming more and more victims. And now, it seems it has reached down to the set of Downton Abbey. The Daily Express and the Daily Mail reported recently that the set had been spooked by a series of uncanny events, associated with the museum display of artefacts from the tomb in the basement of Highclere Castle. The authoritative source for these stories, it transpires, is Shirley MacLaine, who will appear in a cameo role. MacLaine has been rather more famous for her occult and New Age beliefs than her acting in recent years. She reads auras and believes in reincarnation. She is one of many psychic sensitives who claim that they can see menacing presences swirling around Egyptian artefacts claimed from the graves of kings.

Thomas Douglas Murray. Courtesy of the London College of Psychic Science.

All of this is but the latest addition to a century of mummy curse stories associated with English collectors of Egyptian artefacts. In my book, The Mummy’s Curse, due out this autumn, I try to peel back the weird accumulation of stories to find the origin of these stories. The Curse of Tutankhamun flew off the presses in 1923, it turns out, because the way was prepared by two prior stories of Victorian gentlemen who had purchased mummy materials in the grey market of antiquities traders and suffered the consequences. The first, Thomas Douglas Murray, was a socialite well known for his parties with painters, actors, and African adventurers in his London town house in the 1870s. As a young man, he had bought a mummy case in Luxor in the 1860s, only to go hunting shortly afterwards, slip, and shoot his own arm off. He survived bearing this awesome wound of his colonial folly. The Priestess of Amen-Ra, as she was known, did all sorts of devilish things to Londoners until the case was presented to the British Museum in 1889. It resides in the Egyptian Rooms and is still known as the ‘Unlucky Mummy’, although much of the folk history attached to it has been shed along the way.

Walter Ingram. From the family collection of Anne Bricknell.

The second adventurer was the soldier Walter Herbert Ingram, who fought in the Zulu Wars and was a great hero of battles against Islamic rebels in Egypt and Sudan in the 1880s. Ingram bought a mummy case as a souvenir, only to be killed by an elephant on his next visit to Africa, prompting rumours that he had been cursed. Ingram was the youngest son of the founder of the Illustrated London News. His death, understandably, was a news sensation. The record of the lives of these extraordinary gentlemen has rested, largely untouched, in London’s eccentric archives and in family memorabilia, the fable of their curses wrapped around the true details of their lives.

Unravelling these histories tells us a lot about how Victorians and Edwardians used the supernatural to negotiate unease with colonial occupation and the traffic in ancient artefacts to the museums and private collections of the imperial metropolis. They tell us more, I’d like to think, than the clumsy way in which Downton Abbey’s Earl of Grantham and his sniffy butler are always bumping into world historical events.

Roger Luckhurst has written and broadcast widely on popular culture, specialising in science fiction and the Gothic. He is interested in the odd spaces between science and popular supernatural beliefs. He has previously written a history of how the notion of ‘telepathy’ emerged in the late Victorian period, and has published editions of Jekyll and Hyde and Dracula. He is also a regular radio reviewer of terrible science fiction films. He teaches horror and the occasional respectable novel by Henry James at Birkbeck College, University of London. The Mummy’s Curse: The true history of a dark fantasy is due to be published in late 2012.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers