Oxford University Press's Blog, page 69

September 22, 2022

10 German history titles to read this autumn [reading list]

When we think of German history, our first thoughts jump to the First and Second World Wars. These chapters in Germany’s history are incredibly important, though it can be confusing to know what to read or how to navigate the wealth of material available for a fresh exploration of the impact of the wars on society, culture, and the lives of ordinary people. It also excludes other important aspects of Germany’s history.

Below are 10 books that we recommend if you want to learn something new about Germany’s past, but don’t know where to begin.

Networks of Modernity: Germany in the Age of the Telegraph, 1830-1880This book offers insight into the origins of the “communications revolution” in nineteenth-century Germany and discusses arguably the most important technology of the time: the telegraph.

The invention of this revolutionary piece of technology impacted trade, finance, news distribution, and government in the tumultuous decades that witnessed the 1848 revolutions, the wars of unification, and the establishment of the Kaiserreich in 1871.

Learn about Networks of Modernity

The Ambivalence of Gay Liberation: Male Homosexual Politics in 1970s West Germany

Shortlisted for the RHS Gladstone Book Prize by the Royal Historical Society, The Ambivalence of Gay Liberation clears up myths about the gay pride movement and tells the stories of the groups that were part of it.

Craig Grifiths explores the ways that being queer was talked and thought about in 1970s German 1970s—a period sandwiching the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality in 1969 and the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s.

Find out more about The Ambivalence of Gay Liberation

Prostitution and Subjectivity in Late Medieval Germany

In medieval Germany, prostitutes were viewed as sinful, the risks and dangers faced by women ignored. Yet the period also saw a rise in prostitution that was tolerated by society. This book examines how prostitution in the Middle Ages allowed—and disallowed—women to exert agency within their own lives and in response to official attempts to regulate sexual behaviour.

Discover more about Prostitutions and Subjectivity in Late Medieval Germany

Our Gigantic Zoo: A German Quest to Save the Serengeti

The Seregenti has become an internationally renowned African conservation site and one of the most iconic destinations for a safari. How?

In Our Gigantic Zoo, winner of the DAAD Book Prize of the German Studies Association, Thomas M. Lekan illuminates the controversial origins of this national park by examining how Europe’s greatest wildlife conservationist, former Frankfurt Zoo director and Oscar-winning documentarian Bernhard Grzimek, popularized it as a global destination.

Find out more about Our Gigantic Zoo.

Through the Lion Gate: A History of the Berlin Zoo[image error]Through the Lion Gate is the first book in the English language to present the history of the Berlin zoo and its importance over a 150-year period.

From exciting stories about animals, including that of the hippo who survived the bombing of 1943 and consequently became an icon of Berlin, to how Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring led the Nazis to promote animal protection laws to spread their ideology, discover the history of the Berlin Zoo.

Read more about Through the Lion Gate.

Hitler’s True Believers: How Ordinary People Became Nazis

This book provides an explanation as to how and why millions of leaders and ordinary citizens in a well-educated, cultured nation adopted an extremist and murderous ideology that culminated in the Holocaust and the Second World War.

It examines the Third Reich and how ordinary people came to believe that Hitler was a “necessary leader” who could create a select “community of the people” to achieve national renewal.

Discover more about Hitler’s True Believers.

The Gestapo: Power and Terror in the Third Reich

The Nazis’ notorious secret police force, the Gestapo, was the epitome of terror and oppression. This book challenges the many myths that have surrounded the organisation, highlights just how powerful and all-knowing they were, and outlines the Gestapo’s history from its early years in the Weimar Republic, through the crimes of the Nazi era, to its demise in the post-war world.

Before the Holocaust: Antisemitic Violence and the Reaction of German Elites and Institutions during the Nazi Takeover

Following the Nazi takeover in 1933, antisemitic violence soared. It has widely been assumed that the violence, including boycotts, violent attacks, robbery, extortion, abductions, and humiliating “pillory marches”, and the escalation to grievous bodily harm and murder, occurred long after the takeover. Before the Holocaust argues that this isn’t the case: it began before.

Find out more about Before the Holocaust.

Misfire: The Sarajevo Assassination and the Winding Road to World War I

This book coherently situates the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Habsburg Empire, in a broad historical context. The author inserts the incident in the longer-term conditions of the Balkans that gave rise to the political murder, illuminating how the Bosnian Crisis and the Balkan Wars of the early twentieth century were central to European power politics.

Austria 1867-1955

Drawing on archival resources taken from diaries, administrative reports, autobiographies, diplomatic archives, and Cabinet minutes, Austria 1867-1955 is the first book to comprehensively analyse the political history of modern Austria, connecting the Imperial and Republican periods in one clear narrative. It also addresses why, after 1945, Austrians refused to come to terms with their nation’s involvement in the Nazi regime of the Third Reich.

Learn more about Austria 1867-1955.

Featured image by Dan V via Unsplash, public domain

September 21, 2022

The word “condom”

I had no intention to deal with this word, but a few days ago, one of our correspondents asked me whether the information on the etymology of condom one finds on the Internet can be trusted. The answer is “on the whole, yes.” A few websites provide debunked hypotheses, but most are reliable, especially if they cite the relevant bibliography. I may have a richer database on condom than some authors, because it contains references to such old English and German medical journals as Human Fertility, but I have not unearthed any information unknown to my predecessors. I am writing this blog post only out of deference to our reader.

For a long time, the word condom was unprintable. Neither the original OED nor The Century Dictionary (the latter a very full American reference work) featured the word. The same holds for all the other excellent thick dictionaries published a century ago and earlier. The Second Supplement to the OED does include condom. It even provides a brief note on the origin, while the OED online gives a rather detailed history of the futile attempts to trace condom to its source.

Several venues for discovering the origin of condom have been tried. It was long believed that Condom is the name of the person (presumably, a doctor) who invented the device. The English word surfaced in texts at the beginning of the eighteenth century, but we cannot be sure that the word was coined in England. Perhaps it was a borrowing from French, thus, a genuine “French letter.” In any case, the hunting of Dr or Mr Condom was not more successful than the hunting of the Snark. Words from names (Diesel, Shrapnel, Ohm, Ampere, and so forth) are very numerous, but one wonders whether anyone called Condom would relish the fame of being remembered as the inventor of such an object. Marley was dead to begin with, as Dickens informs us. So is Dr Condom, even though the family name Condom exists.

The best portrait of Mr/Dr Condom available.

The best portrait of Mr/Dr Condom available.(Photo by Chien Nguyen Minh on Unsplash, public domain)

There is a little town in France called Condom, and attempts have been made to derive the English word from this place name, especially because the town has a busy leather industry. However, in France, condoms are not called condoms (the word is préservatif; the same word is used in German and Russian, so that when French, German, and Russian speakers come to the United States and read that a certain product contains no preservatives, they are tickled to death). To be sure, in French, Condom is pronounced with stress on the second syllable and a nasal vowel, but it could have been naturalized and yielded English condom. The decisive argument against the borrowing is that the word in question does not exist in French. Such funny coincidences are not too rare. For example, there is a village in Upper Austria now called Fugging. Until 2021, the place name had ck, rather than gg, in the middle, and I have read that the inhabitants used to enjoy their fame. To be sure, in the German word, the letter u has the value of u in English put. Anyway, English condom owes nothing to the French place name.

A genuine French letter.

A genuine French letter.(Image by Karen Arnold, public domain)

It is, I think, unlikely that condom was borrowed wholesale from another language. Thus, a Persian source, an Italian word for “glove,” conundrum, and an Italian word group have been suggested as the source, to say nothing of partial homonyms in Latin that refer to entirely different objects. The argument against such ingenious derivations is the same as against French Condom. It is of course possible that a late seventeenth-century Englishman used French or Latin or Greek roots for coining the name of the new device. Think of our modern words like ibuprofen, Advil, and dozens of others (and see below!). Yet now that so much ingenuity has been wasted on discovering the etymology of condom, we should agree that the word surfaced in England.

It seems that condom has two roots: con and dom. Con (like Latin cum) means with, while dom reminds us of the Latin word for “house” and of English dome. Thus, the organ, supplied with the “dom,” had the protection of “a house.” Condoms have always been used to keep both men and women safe from venereal diseases, rather than as contraceptives, though the legend has it that Charlies II, whose court physician allegedly invented the device, began to feel annoyed at the ever-multiplying number of his illegitimate children. The emphasis may be not (or at least not only) on the male organ but also or even mainly on the vagina.

View of Condom, France.

View of Condom, France.(Photo by Oxxo, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Professor Michael Shapiro once sent me his unpublished paper on the origin of the word condom, and I have not seen it in print since that time. He pointed out that Latin vagina means “sheath” and wrote: “If the condom is a ‘sheath’, as its destination (in use), then the only difference is that between a male and a female ‘sheath’. Hence in colloquial French it is a con d’homme ‘male vagina’, whence condom is only a matter of orthography.” It is an elegant etymology, but I had (and still have) some doubts about it. According to Shapiro, the word is French and was coined by French speakers, though, as we have seen, the word’s home seems to be eighteenth-century England. However, French enjoyed tremendous popularity during the reign of Charles II, so that a French term could be easily coined by an Englishman during his reign. Though I wonder why no French etymologist has hit on such a transparent derivation, Shapiro is right that among the numerous works on the origin of condom there is not a single French title. Apparently, the word has never interested French historical linguists.

Blessed are those who need no condoms and don’t bother about etymology.

Blessed are those who need no condoms and don’t bother about etymology.(Photo by Daniel Schwen, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In this state of uncertainty, I may say that I also look on condom as a compound, possibly with reference to French con “cunnus, vagina” (or to some forgotten con word for “penis”?). It would be nice if the word meant “penis sheath” or if –dom resolved itself into d’homme “of a man,” on the assumption that condom was a French word coined in England.

Now back to the Internet. Trust only such websites that offer a survey of opinions and ignore the authors who offer a certain etymology as proven. Above, I have not given any references to the literature on the subject. Anyone seriously interested in this literature will find it in my Bibliography of English Etymology and in the book Looking for Dr. Condom by Wm. E. Kruck. (Publication of the American Dialect Society, No. 66. University of Alabama Press, 1981.) An excellent monograph; needless to say, Dr Condom is an etymological ghost now laid to rest for all times.

Featured image by Faridun Saidov, public domain

September 20, 2022

What is transparent peer review?

The peer review process is an integral part of scholarly publishing, designed to evaluate the importance, validity, and originality of a paper. There are five peer review models currently in use, all with various benefits and drawbacks. Transparent peer review is a relative newcomer and not widely used at present, but it has grown in popularity and is becoming an increasingly popular choice. The question is—why? This blog post takes a closer look at the transparent peer review process, its rise in popularity, and the challenges journals, reviewers, and editors face with this model.

What is transparent peer review?Transparent peer review is a model that showcases the full reviewing process. Alongside a published article, readers can see the full peer review history, including reviewer reports, the editor’s decision letters, and the author’s response. It is called “transparent” because this review model allows everyone to see and understand the reasons for the editor’s decision. This contrasts with some of the more traditional peer review models, which leave readers in the dark. Transparent peer review shines a light on how and why the publication decision was made.

Open and transparent peer review are like siblings—similar, but not the same. Unlike in anonymous peer review models, with open peer review the author and reviewer identities are disclosed to one another and the reader. This disclosure isn’t a requirement in transparent peer review—if a reviewer wants to reveal their identity they can do so, but the reviewer report can be published anonymously if preferred.

Popularity of transparencyThere are many reasons why this model has risen in popularity. Confidence in peer review has decreased due to untruthful practices like fake peer review and peer review bias. With the single anonymised peer review model there is sometimes concern that knowing the author’s identity can lead to bias from reviewers and editors, or unfair judgement tainting the decision-making. Because of this, authors are likely to have doubts in the peer review process. Furthermore, the high amount of confidentiality and information restriction can feed into the perception of secrecy in publishing.

Transparent peer review aims to restore trust in the integrity and fairness of the peer review process.

Transparent peer review aims to restore trust in the integrity and fairness of the peer review process. Because identities, reviewer reports, and decisions are published, the process is documented for the reader to see. There is also a hope that reviewers may spend more time on clear and constructive comments if they know they will be publicly visible and attributed to them.

Findings show that Early Career Researchers (ECRs) are choosing transparent peer review processes as it encourages constructive open feedback and facilitates discussion. This is advantageous for ECRs as it allows them to improve and progress professionally. The preference for transparent peer review can also be seen in the context of ECRs’ more general adoption of openness and collaboration in research and publishing. ECRs tend to prefer using open-source software as part of their research and write-up processes and are more likely to publish in open access journals, as these concepts complement each other. Open access papers are cited on average more than papers behind a paywall and opening up the data behind the research can lead to more openness when it comes to reproducibility. Transparent peer review is another way of achieving these goals, and it can help to identify any conflicts of interest in the peer review process, such as being a collaborator on a research project.

Transparent peer review challengesA lot of research on transparent peer review is focused on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) publications, so the outcomes and lessons could be seen as limited, especially when considering the different needs of SHAPE (Social Sciences, Humanities, and the Arts for People and the Economy) publications and peer review processes. In SHAPE, the preferred peer review method is usually a longer process and double-anonymised. According to the Publishing Research Consortium, 50-70% of the SHAPE researchers would support open peer review. However, that support would decrease to 35-55% if open peer review were to include signed reviews published with the associated article. Nevertheless, SHAPE could take advantage of the benefits of transparent peer review to facilitate dialogue and collaboration between authors.

Other challenges for transparent review may include authors and reviewers not being comfortable with their comments being shared and identities potentially disclosed. Some reviewers may alter how they are writing their reports if they know it will be published with the paper, which could introduce bias. Another challenge could be a reduction in the number of reviewers willing to work with a journal that has transparent peer review, exacerbating the current difficulties many journals face attracting and recruiting enough reviewers To counter this, many publications with transparent peer review processes offer an opt-in option. It is important to ensure clarity in journal peer review policies and that all parties provide the relevant consent. Journals should adopt policies that explain exactly what will be made available in the transparent peer review process, and authors or reviewers who are not sure about these policies should contact the relevant Editorial Office.

OUP perspectiveWe offer support and refer our editors, authors, and reviewers to the COPE Ethical Guidelines for Peer Reviewers. We do not support one system of peer review over another, but we encourage our journals to publish their peer review procedures as part of their submission guidelines.

Several of our journals offer optional transparent peer review, such as Oxford Open Immunology, Brain Communications, and FEMS Microbes. This means that the author is asked at manuscript submission whether they would like the review comments to be made available should the paper be accepted after peer review. Reviewers can also opt to reveal their identity, either by signing their review or agreeing to have their name appear on the published manuscript. Where we offer this, and the option is taken up, the peer review comments are published as supplementary files.

For more details about peer review processes, please see our Fair Editing and Peer Review guidance.

Shipwreck tales: bounty from the archives

News broke in 2022 that the royal frigate Gloucester that sank in 1682 had been located off the coast of Norfolk. The discovery excited marine archeologists and treasure hunters and drew attention to the scandal of the warship’s loss. It was bad enough that the ship hit a sandbank because of “the wrong calculation and ignorance of the pilot.” Worse was the behaviour of the Duke of York and other officers, who secured their own survival while hundreds of common seamen drowned. The episode is discussed in Shipwrecks and the Bounty of the Sea, along with dozens of accounts of maritime disasters and their consequences from the reign of Elizabeth I to the age of George II. Well ballasted with evidence, and fully freighted with references, the book engages social, legal, and maritime history, and the politics of the water’s edge where, as the proverb said, it was an ill wind that blew nobody any good.

No book is the last word on its subject, and every study is in some sense interim. I finished Shipwrecks in the midst of the pandemic, far from England and heavily reliant on internet resources and the generosity of archivists and librarians. Only in the spring of 2022, when the book was in press, was I able to return to The National Archives at Kew for the first time in several years. Following the principle of chasing every lead and leaving no stone unturned, I examined manuscripts that had not been previously accessible. Produced by different offices and agencies, they illustrate the richness of English public records for exposing the social, legal, and economic history of the coastline.

Included in this new trawl are Star Chamber complaints from 1582 that one landowner “spoiled” the goods and chattels that another claimed by right of “wrecke de mere” and that each brought followers “in most riotous and warlike manner” to battle it out on the beach. Honour and privilege were at stake, as well as the profits from wreckage.

Exchequer depositions from 1669 include reports by humble parishioners of their role in “hacking and hewing and carrying away” the “stuff and materials” of a ship cast away in Sussex. When their lord of the manor ordered them to desist, because he claimed wreck rights for himself, one of them threatened “that they would cleave his head over his shoulders.” Shipwrecks tested hierarchical authority and social discipline, though wreckers were not normally as violent as sometimes represented.

Admiralty examinations from 1673 concern the warship Algiers that wrecked on the coast of Essex. Local workmen related how they broke into the stricken vessel and made off with useful timber, ironwork, shrouds, and casks. Dozens of similar records describe the controversial transfer of resources from the sea to the land in the grey zone between salvage and plunder.

Treasury memoranda from 1694 register the recovery of seven bronze cannons from the naval flagship London that exploded in the Thames a generation earlier. They point to improvements in underwater technology, and to continuing disputes about ownership.

Chancery records from 1729 review wrecks on the shore of a Sussex manor over 50 years, and “the several anchors and cables that were seized by the said lords.” Seigneurial rights were in competition with claims by the Admiralty, the Crown, and local opportunists.

Customs agents, treating shipwrecked goods as dutiable imports, described in detail the fate of the Dutch freighter Hope, heavily laden from the Caribbean, that was cast away in Dorset in 1749. “As the ship struck the head and stern was carried off to sea, her bottom bulged that thrust in to the beach and there buried. The country people came down in great gangs and carried off what they could lay their hands on in defiance of the officers.” The tide surveyors gave their opinion that surviving crewmen “might have defended the ship from being plundered by the country mob, especially when three or four carriage guns in the remaining part of the ship pointed directly to the shore.” Once again discussion turns on ownership, obligation, opportunity, and control, as shorefolk and mariners competed for the bounty of the sea.

These fragments emerged too late for inclusion in my study. They add detail and texture, but do not alter any conclusions. No doubt the archives contain many more such gems. The Gloucester sank too far offshore for coastal villagers to scavenge its goods and fittings, so it will be up to suitably licensed divers to bring its bounty ashore.

Featured image: ‘Shipwreck’ (circa 1850), by Francis Denby, via Wikimedia Commons , public domain

September 18, 2022

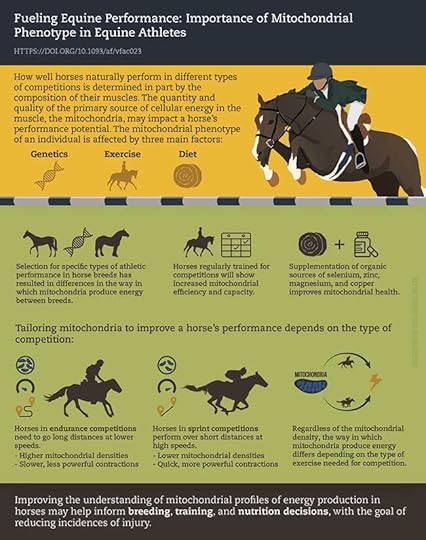

Horse power from the powerhouse of the cell [infographic]

Secretariat, Man O’War, Frankel, Bucephalus; all are incredible horses with amazing athletic abilities. But what makes a great horse great? As described by Latham et al. in a recent Animal Frontiers article, the mitochondria, or powerhouse of the cell, is at least partially responsible for athletic performance. Through a complex chain of events, mitochondria use electrons and other intracellular proteins to generate adenosine tri-phosphate, or ATP. ATP is then used by muscles and other tissues in the body as an energy source. The number and productivity of the mitochondria impact how efficiently ATP is produced, and the potential for athletic ability in the horse.

Athletic horses may perform endurance or sprinting competitions. In horses competing in endurance competitions, where they require relatively small amounts of ATP over a long period of time, there are many mitochondria present in the muscle. In contrast, horses performing in sprinting competitions have many fewer mitochondria. However, the number of mitochondria present in the muscle increases with exercise training, regardless of the type of training (sprint or endurance).

Recent work by Latham et al. has identified that different mitochondrial characteristics may cause one animal to be suited to specific types of activities. In Thoroughbred racehorses, preliminary data indicates that future sales price (a proxy for predicted success) is positively correlated with mitochondrial efficiency (Guy et al., 2020) and that race earnings as two- and three-year-olds is associated with measures of mitochondrial function (Latham et al., 2019). Initially determined by genetics, these mitochondrial characteristics may be refined by exercise and other factors (e.g., nutrition) to refine their function and improve performance.

In the future, it may be possible to use mitochondrial “type” to identify the athletic events in which you (or your horse!) are most likely to be successful.

Explore the infographic to learn more:

Further resources

Further resourcesTake a further look into what makes an athletic horse in these related articles in Animal Frontiers:

“ Osteoarthritis: A common disease that should be avoided in the athletic horse’s life ” by R. Baccarin, S. Seidel, Y. Michelacci, P. Towkawa, and T. Oliviera“ Neurologic conditions in the sport horse ” by D. Bedenice and A. L. Johnson.“ The Olympic motto through the lens of equestrian sports ” by Hobbs, S. J. and H. M. Clayton.“ Equine exercise physiology – challenges to the respiratory system ” by M. Mazan.

September 16, 2022

Alice le Fynch and new ways of seeing medieval society from below

Everyone in the village of Sedgeberrow must have known Alice le Fynch, a determined personality defending the interests of her family. She had to make decisions on her own when her husband Henry died, and she took over the management of the family land holding of 22 acres. In 1326, when she was in her fifties she planned to retire and hand the land over to the next generation. By customary law her son John should have succeeded, but she did not believe that he was capable of running the holding, and her neighbours, meeting in the manor court, agreed. Perhaps Alice persuaded them to reach that conclusion. Alice arranged for the main holding to go to her daughter Margery, observing the rule that the inherited land should not be divided. Agnes, the younger daughter was able to take over land that her father Henry had acquired, a custom that suited Alice’s ambition of providing for both daughters. The transfer cost money, as all new tenants were obliged to pay a fine to the lord of the manor. Margery, no doubt helped by her mother, had to find the large sum of £5 by borrowing, perhaps from a Tewkesbury corn merchant. The lord (or his officials) watched all this with interest, but did not intervene: the lord was gaining £5, and was reassured that a reliable tenant would pay the rents in the future. The lord and the leading villagers hoped that Margery would soon marry, as they preferred male tenants. The le Fynches were serfs, which was a burden to them in many ways, but their unfree status did not prevent Alice from taking the initiative and settling her family affairs.

This sketch of an incident in the life of rural Worcestershire does not accord with some prejudices about peasants still widely held. They were not controlled in all that they did by their lords. They were not stupid and ignorant, but manipulated law and custom in their own favour. They were not all miserably poor. They did not live in isolation, but looked outside their villages, for example to seek opportunities in neighbouring towns. Women did not lack authority, and had influence over the future of their families.

“Peasants should not be underestimated, as they were drawn into active roles in law, government, and religion, and could make up their own minds about issues in politics and religion.”

Peasants making history is about the decisions, choices, innovations, prejudices, errors, and achievements of medieval peasants. Lords had authority over them, but their spheres of activity were limited, and they were often dependent on the co-operation (sometimes reluctant) of peasants. Lords would found towns, but their subsequent growth was made possible by the migration of people from the country, who set up new businesses, or encouraged their sons and daughters to move. Once established, peasants’ sold their grain, livestock and other products in the towns’ markets, and the craftsmen and traders of the town supplied ordinary clothing, shoes and metal wares made locally. Peasant consumers were not limited to cheap local goods, but bought imports such as whetstones from Norway and millstones from Germany. Industry in the countryside, such as cloth-making, depended on a part-time peasant workforce and the skills of entrepreneurs including some of peasant origin.

These commercial developments were made possible by the output of the land, which gave the peasants their incomes. A common view is that peasants, restrained by tradition, observed unthinkingly the repeated annual cycle of sowing, harvest, lambing, shearing and dairying. But quietly and flexibly they were making important changes in the choice and rotation of crops, and in the balance between growing corn and keeping animals. They fenced off common land for private use as individuals, or on a large scale for the whole community. In adjusting their methods, they were facing the dilemma of all small-scale farming—should priority be given to supplying the household, or to sending a surplus to market?

The mindset of peasants has to be reconstructed from indirect hints in records written for official purposes, or the material remains of their settlements, houses, and possessions. Peasants should not be underestimated, as they were drawn into active roles in law, government, and religion, and could make up their own minds about issues in politics and religion. The community of the village was concerned with practical matters like regulating the fields, but also held enjoyable celebrations at which ale was drunk. We catch a glimpse of Alice le Fynch at a crucial point of making decisions that would change her family’s future. She would be able to take pleasure in village and family festivities, and would be familiar with popular games, music, stories, and drama.

Featured image by Illiya Vjestica via Unsplash, public domain

September 15, 2022

Why we all need more Lesbian Dance Theory

Last month a Member of Congress joined Fox News to claim President Joe Biden is “robbing hard working Americans to pay for Karen’s daughter’s degree in lesbian dance theory” in response to the announcement that the President was providing $20,000 in debt relief for Pell Grant recipients and $10,000 for many other borrowers. A few days later the same Member of Congress shared her belief that “Joe Biden now wants to pay for Lesbian Dance Art degrees” at a campaign event. As far as I know such degrees are not in the official academic catalog of any accredited American institute of higher learning, but I may be wrong. Perhaps new programs in Lesbian Dance Art and/or Theory are emerging as you read this right now? The Congresswoman’s use of the “lesbian dance” as a stand-in for a useless degree and as a cover to lambast academic and artistic freedom and the humanities by and large is not new (Ben Shapiro has been using it to troll and mock since at least 2015), nor a uniquely Republican tendency in American politics.

While “Lesbian Dance Theory/Art” may not be a real undergraduate degree, theorizing about lesbian dance and art is real, and it is certainly not useless, frivolous, or wasteful. Creating art and thinking about art are inherently valuable exercises: they improve our lives and broaden our understanding of ourselves and our world. For those of us lucky enough to practice, study, and teach in the arts, we see this every day. And while the Congresswoman’s remarks were most likely meant to denigrate and belittle (trafficking in homophobic and anti-intellectual tropes), Lesbian Dance Theory/Art offers us unique insight into the past and new paths into our future.

“Creating art and thinking about art are inherently valuable exercises: they improve our lives and broaden our understanding of ourselves and our world.”

Over a century ago in a Parisian suburb, a young American woman and her friends dared to imagine a Lesbian Dance Art, a uniquely queer choreography of their loves, relationships, fantasies of queer pasts, and dreams for a queer future. This woman, Natalie Clifford Barney (1876-1972) used her verve, artistic sensibilities, connections, and inherited wealth to host private spaces for lesbian women to come together, discuss art and life, and perform poetry, music, and dance. They did this at a time when public discussion of what it meant for women to love women outside of narratives of psychological pathology was relatively new, nebulous. Beginning around 1900, Barney and her dancing friends (including at various points, Mata Hari, Liane de Pougy, Isadora Duncan, Eva Palmer-Sikelianos, Penelope Duncan, and Marie Rambert) used dance to perform in the present an imagined ancient past where women were free to love women. As I discussed in my book, Performing Antiquity, they would dress in ancient Greek costumes, plucked reproductions of Sappho’s lyre, sang invented ancient Greek hymns, and danced invented ancient Greek dances as they sought to define a lesbian future where you didn’t need a man to lead. The reliance on millennia-old models (the Archaic Greek lyrics of Sappho of Lesbos, for whom lesbianism is named) was the only model Barney and her peers knew that allowed them to reimagine dance for lesbians. But they used this past to imagine a future.

As Natalie Barney’s reimagination of ancient lesbian dance art illustrates, while lesbians have been dancing for millennia, lesbian dancers and lesbian dance has historically received little theorizing or documentation. Barney had no models of lesbian dance to look to, no one to teach her the steps. This erasure of lesbian dance persists. Peter Stoneley’s 2007 book, A Queer History of the Ballet all but ignores queer women altogether focusing almost exclusively on queer male identification in ballet. More recently, Clare Croft’s 2017 edited collection, Queer Dance: Meanings & Makings takes important steps to theorize queer dance. “No single entity marks something as queer dance,” Croft asserts, “but rather it is how these textures press on the world and against one another that opens the possibility for a dance to be queer.” Lesbian dance, as part of the project of queer dance challenges and disrupts, disorients and reorients audiences, and that is perhaps its greatest power and threat. As Croft writes, “Queer performance can thwart an audience’s assumptions about bodies, desire and sex… In this way, queer performance becomes a kind of pedagogy, teaching someone what it might look like or feel like to refuse norms, particularly those related to gender and sexuality.”

“Lesbian dance… challenges and disrupts, disorients and reorients audiences, and that is perhaps its greatest power and threat.”

Take Adriana Pierce’s choreography for Daphne Willis’s pop ballad, “I Am Enough” featuring New York City Ballet’s Georgia Pazcoguin and Broadway dancer Skye Mattox. Pierce places the dancers on either side of a suspended tangle of leather ropes and straps that serves as both a permeable barrier and visual bars separating the two women. Pazcoguin watches as Mattox arabesques. They dance for each other until Mattox reaches out her hand through the tangle of ropes to make contact with Pazcoguin. They are kept apart until the second verse of the song. In the second verse of the song the dancers perform a series of turns, spinning away from the tangle of ropes and straps and into each other’s arms. They partner, following the curve of the other woman’s twisting torso with their arms, embracing, and then joining together in synchronized arabesques and pirouettes, but the classical ballet vocabulary breaks down after the song’s bridge for the final chorus as Mattox presses Pazcoguin’s hands to her heart before Pazcougin goes in for a real and passionate kiss. After all the balletic performing of passion and intimacy, the gestures of love forbidden/blocked, the metaphoric spinning out and away from the tangled ropes, the two women do something rarely done in ballet. They stop doing ballet and kiss: necks craning, backs arching, shoulders rising, hands grasping faces. In that moment this piece of Lesbian Dance Art embraces and blasts open the conventions of ballet.

While Lesbian Dance Theory might not be a real major, the work of making sense of uniquely queer ways of moving, and knowing, and claiming space, provide creative spaces to reimagine our connections to each other through movement. The very vilification of Lesbian Dance Art and Theory is a testament to its important function in upsetting norms and creating spaces for bodies to create new meanings.

Featured image: A gathering of women including Eva Palmer, Natalie Barney, and Liane de Pougy in Barney’s garden in Neuilly, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

September 14, 2022

On mattocks and maggots, their behavior and origin

The first half of the title looks like Somerset Maugham’s Beer and Skittles but has nothing to do with recreation: its subject is hard work. Those who have read my older blog posts on axe and adz(e) (see the post for 25 March 2020, with reference to an earlier publication on this subject) won’t be surprised to learn that the mattock, a simple tool, has a name troublesome to etymologists, even though, like adz(e), mattock has been known since the Old English period. In the extant texts, the forms are mattuc, meattoc, and meottoc. The variation of this type is common, because Old English preserved the pronunciation of several dialects. Also, scribes were often uncertain about the spelling of the words they knew. There is nothing particularly astounding in those forms. I am saying this because it has been suggested (wrongly, as I think) that the recorded forms look unusual, even exotic, and that therefore the word must have been borrowed from some unknown indigenous language.

References to “an unknown language” mean “substrate,” the language of the aboriginal population. Before the Germanic invasion, Britain was a Celtic-speaking country. Similar Welsh and Scottish Gaelic forms exist, but they may have been borrowed from English, rather than serving as the source of mattock. This uncertainty in dealing with Celtic and English words is typical, and opinions on the origin of mattock differ. (Also, in Celtic, such an obscure word may have been taken over from an even deeper substrate! The Celts were not the first inhabitants of the island, and nothing is known about the language of the Picts.) In any case, mattock, in its Germanic form, rather obviously consists of the root mat(t)- and the diminutive suffix –ock, as in bullock “young bull,” ballock “testicle” (regional?), hillock, and a few more nouns. One can easily understand why people form words like “little bull,” why a testicle looks like a tiny ball, and why a hill can be small, but the reference to a small mattock makes less sense than, for instance, to a small ax or a small hammer.

A still more puzzling circumstance is the isolation of mattock in Germanic. There is no word like it in Frisian, Dutch, German, or Scandinavian, and, if it is true that the Celtic lookalikes are loans from English, the origin of mattock begins to look like an insoluble puzzle. To exacerbate the problem, we discover that mattock has excellent relatives (cognates, congeners) “abroad,” namely, in Slavic: motyka, motyga, and the likes (stress on the second syllable). The meaning of the Slavic noun is the same.

Stonemasons probably do not belong to our story.

Stonemasons probably do not belong to our story.(Photo from Amman Citadel Hill, via Pxhere, public domain)

Slavic etymologists cannot agree about the word’s origin. Quite common is the derivation of the oldest form motyka from the ancient root mat– “to dig.” Sanskrit matyá “harrow” (noun),Latin mateola “rod, club, mallet,” and perhaps a few verbs meaning “to toss, mix up, etc.” may be related. A different but similar etymology of the English word connects mattock with Vulgar Latin matteūca (rather than mateola) “club, stick.” The only reference book that traces English words to reconstructed Indo-European roots is The American Dictionary of the English Language. The information there is not original. It goes back to the great dictionary by the late German scholar Julius Pokorny, who traced mattock to the root mat-, as in Latin mateola. In 1929, he even wrote a short article about this word. A few other words that may be related to mattock also exist. German Steinmetz means “stonemason.” Stein– is “stone,” but what is –metz? Is its root the same as in English mete (out) and mattock? This connection has often been suggested and denied.

Perhaps the most unexpected turn in our plot has been caused by a suggestion in the Norwegian etymological dictionary by Hjalmar Falk and Alf Torp, two distinguished Scandinavian language historians. There was a Middle English word maddock “larva,” borrowed from Old Norse and slightly reshaped. The syllable –ock is the suffix we have seen in bullock, and the root occurs in almost all the Germanic languages. Even Gothic, a fourth-century language, preserved in a masterful translation of the New Testament, had the suffix-less noun maþa “worm” (þ has the value of English th in thin). This maddock, apparently, “a little worm,” later became English maggot. The great but irascible Walter W. Skeat called that change “perversion.” Could the “perversion” be due to taboo, to the fear of calling the creature by its real name? (Mere guessing, to quote Skeat’s favorite phrase.) The origin of maþa “worm” is (of course!) unknown, but the word sounds amazingly like English moth. There must have been something in the math ~ moth syllable that the speakers of the oldest Germanic languages associated with such creatures. Obviously, mattock sounds very much like the afore-mentioned maddock.

Moth and maggot.

Moth and maggot.(L: via Pxhere, public domain; R: by Amada44, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

According to Falk-Torp, the root of maddock and mattock was approximately “to crush” (Slavic etymologists suggested dig: see above!): the mattock, maggot-wise, allegedly worms its way through the ground. Compare English hoe, a close synonym of mattock. It surfaced in English texts in the fourteenth century and has the same root as the verb hew. Scandinavian linguists (for instance, Jarl Charpentier and Ásgeir Blöndal Magnússon, the author of an etymological dictionary of Modern Icelandic) endorsed Falk and Torp’s idea, even though they gave no reference to it and offered discussion (they confined themselves to short, dogmatic statements), while English and Slavic sources do not seem to have noticed their idea.

We can easily understand why the OED and the sources depending on it state that the origin of mattock is unknown. I would prefer to say that the word’s origin is uncertain rather than unknown (as the OED online also does). No less interesting than the reconstruction of the word’s ancient root (always a dubious enterprise) is the question about why English mattock is so similar to its Slavic lookalikes and, if somewhere along the way one language borrowed from another, why, in the Germanic group, only English has mattock. As far as I understand Falk and Torp, they looked on maddock ~ mattock as native Germanic words.

Falk and Torp come to the rescue.

Falk and Torp come to the rescue.(L: Hjalmar Falk, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain; R: Alf Torp, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The names of tools are often borrowed from other languages. Medieval artisans traveled from land to land, and the names of their implements became part of what is known as lingua franca (I mentioned this fact in the post on adze). Curious blends sometimes appeared, and garbled forms came up. If Falk and Torp guessed well, that is, if the mattock got its name because it behaved (figuratively speaking) like a maggot, inching its way trough hard ground, we will still wonder at the geography of this word. Why English and Slavic? Why, almost ubiquitous in Slavic, while in the Germanic-speaking world only English? Etymology would be a dull discipline if it could answer all the questions and left nothing for us to ponder.

Featured image: “Small pickaxes in comparison with a pickax’s head” by Juan R. Lascorz, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

September 12, 2022

Ralph Vaughan Williams and the art of the amateur

Within the broad family of television programs classified as “reality shows,” some of the most engaging are those that showcase amateur performance and achievement. Part of the appeal of programs like America’s Got Talent, So You Think You Can Dance, or The Great British Bake-Off lies in being able to identify with its contestants. When we experience the vicarious thrill of watching a primary school teacher execute a perfect paso doble, or a welder turn out a flawless tray of Chelsea buns, we are reminded that ordinary people, including ourselves, can harbor extraordinary abilities.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: advocate for amateursThis was also the opinion of British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958), one of the twentieth century’s great champions of and advocates for amateur music-making. Ironically, despite his own outstanding achievements over the course of his sixty-year-long career—not just as a composer, but as conductor, teacher, writer, editor, folklorist, administrator, and philanthropist—his own long-standing affiliation with amateur performers led some critics (sympathetic and otherwise) to describe his own music as technically clumsy or awkward, despite all evidence to the contrary. Vaughan Williams himself was largely unbothered by such comments, not least because he felt that any professional musical culture worthy of the name rested on a foundation of widespread amateur participation. In his essay “Making Your Own Music” (1955), he lauded this “great army of humble music makers…sustaining those [professionals] above them and at the same time depending upon them for strength and inspiration.”

Vaughan Williams’s praise for amateur music-making was not mere lip service, as he spent a considerable portion of his career promoting, preserving, and producing music for and by non-professionals. Between 1903 and 1913, he collected some 800 English folk songs, many of which he arranged for concert performance or incorporated into new instrumental works, and was deeply impressed by the artistry he witnessed among their practitioners in the field. As musical editor for The English Hymnal (1906), Songs of Praise (1925), and The Oxford Book of Carols (1928), he sought to provide Christian congregations with accessible, engaging, and well-crafted tunes worthy of both their spiritual devotion and their often-modest musical abilities. During his service in the First World War, he directed multiple choirs and bands, even in the midst of active combat on the Western Front, in order to help maintain morale among his fellow soldiers. For nearly fifty years, he directed the amateur choirs of the Leith Hill Musical Competition (founded by his sister, Margaret, in 1905) in the Surrey village of Dorking, augmenting his efforts in later years with annual performances of Bach’s St. Matthew and St. John Passions. He wrote numerous test pieces and bespoke works for amateur choral, band, and orchestral festivals throughout England. Few composers of the first rank have contributed more to amateur musicianship throughout their lifetimes than Vaughan Williams, which speaks to his dedication in making music accessible to all.

Technically, the only thing distinguishing amateur practitioners from professionals is whether they get paid to practice their talents. However, terms like “amateurish” or “professionalism” connote qualities distinct from the financial implications of amateur or professional status—namely, what might or should be expected from the modal representative of each group. Amateurs are often assumed to be less skillful, their final products lacking polish or refinement. These latter virtues are typically associated with professionalism, a term bearing a meritocratic assumption: payment comes in recognition of ability, and those who are paid are better than those who are not. Of course, such distinctions do not always hold up. Most Olympians and college athletes are obliged to hold amateur status in order to compete; conversely, many of us have firsthand experience with co-workers, bosses, or other professionals whose salaries far outstrip their actual ability or value.

Televised talent shows: inspiring or discouraging?Competitive television shows thrive on this inherent tension between the amateur practitioner and their remarkable demonstrations of professionalism. But what implications might this carry for those watching at home? On the one hand, as Vaughan Williams argued, it could be a source of inspiration. Perhaps we too could learn magic, or enroll in a ballroom dance class, or take that cookbook off the shelf, just like the shows’ contestants do when they come home from their jobs at the end of the day. Or maybe we can see that our own talents compare favorably with those displayed on TV, giving us the confidence to share them with others. Yet the professionalism on offer can also be daunting, as Vaughan Williams addressed elsewhere in “Making Your Own Music” when discussing the importance of active musicianship among non-professionals:

Will not all this listening to superb, expert performances bring on a counsel of despair in the mind of the humble amateur, who, for example, plays the flute a little for his own amusement? Will he not feel inclined to say, “With my limited capacities, my small opportunities for practice, I cannot hope to approach the perfection which I hear. Better give up the struggle and become a merely passive listener.” If our amateur flautist thinks thus, he will have lost one of the greatest assets of his spiritual life, the vision of the ultimate realities through the making of music.

On talent programs that are carefully edited for television, we rarely see an arc of growth among participants—or if we do, it starts from an already well-developed level—and so our own early efforts in taking on a new hobby may seem, well, amateurish by comparison. This can lead to considerable soul-searching. Is it worth persevering? What do we get out of trying and failing? How can we enjoy being creative if we aren’t very good at it? In answering such questions, Vaughan Williams liked to quote his friend Gustav Holst, who “used to say that if a thing was worth doing at all then it was worth doing badly.” Reflecting on his half-century of service with the Leith Hill Musical Competition, Vaughan Williams knew full well that perseverance in the face of such challenges was the key to success:

Those who only heard the finished result [at the concert performance] knew little of the preparation period when week after week a devoted band of singers would meet in a cold but stuffy school room, half lit by two smelly oil lamps, accompanied by an astonishing machine which had once been a pianoforte. Here these hierophants struggled with music which was often in an idiom new to them, and sometimes at first incomprehensible. Occasionally the leading soprano lost her voice and could not sing, or one of the only two tenors, being the local doctor, was called out in the middle of a practice to assist at one of the joyful occasions that are so frequent in our village; leaving Mr. Smith of Kosikot to wrestle with Bach’s difficult intervals or Handel’s runs alone. And so it went on for the first few weeks. Then suddenly, as by a miracle, the music came alive and we sang on full of hope waiting for the great climax of the spring. At last it arrived. What had been a set of disintegrated units became one whole.

Vaughan Williams’s reminiscence exhorts us to take seriously our own potential as enthusiastic amateurs. The composer was fond of citing St. James in this regard: “Be ye doers of the word, and not hearers only.” Undertaking creative activities for their own sake opens us to discoveries and joys beyond the merely vicarious, even if limited to our local choir or garage band or painting class. As we observe Vaughan Williams’s 150th birthday this year, there is no better way to celebrate than by wholeheartedly embracing his idealistic vision for amateur artistry, the first step toward establishing a truly vibrant creative culture—not just one we watch on TV.

Featured image from Vaughan Williams.

September 11, 2022

Four Very Short Introductions podcast episodes on the Classical world

Did “Ancient Greece” exist? Are all Epicureans decadent dandies? What do we really know about Alexander the Great? Explore the people, places, and philosophies of the Classical world through these four podcast episodes from the expert authors of our Very Short Introductions series.

Listen to the episodes—each under 15 minutes long—below or subscribe and listen to the Very Short Introductions podcast through your favourite podcast app.

1. Ancient Greece“The title ‘Ancient Greece’ is, in a way, an obvious one but on the other hand it’s problematic. I sometimes – partly as a joke – say there was no such thing as ‘Ancient Greece.’”

In this episode, Paul Cartledge introduces Ancient Greece, a period of unmatched influence on the politics, philosophy, religion, and social relations of Western civilization.

Listen to Paul explain what is so problematic about our characterization of this diverse and sprawling era and how he set about tackling such a huge subject.

Or subscribe and listen to the “Ancient Greece” Very Short Introductions podcast episode on your favourite podcast app.

2. Homer“As far as Homer is concerned, his identity has been the subject of much speculation.”

In this episode, Barbara Graziosi introduces “the Homeric question” and explains where we are, exactly, in the search for when, how, and by whom The Iliad and The Odyssey were composed.

Join Barbara as she investigates the contemporary and continued appeal of Homer’s tales, widely considered to be two of the most influential works in the history of western literature.

Or subscribe and listen to the “Homer” Very Short Introductions podcast episode on your favourite podcast app now.

3. Epicureanism“The image of Epicureanism that comes to mind is of a rich dandy fussing over food—but all this is really off the mark. In fact, Epicureanism is a philosophy that covers every aspect of experience in a tightly integrated way and is explicitly critical of self-indulgent behaviour.”

In this episode, Catherine Wilson introduces the school of thought based on the teachings of Epicurus that promotes modest pleasure and a simple life—ideals that still hold relevance today.

Listen as Catherine dispels common misconceptions of Epicureanism and explores its “radical” theory and connections with the history and philosophy of science.

Or subscribe and listen to the “Epicureanism” Very Short Introductions podcast episode on your favourite podcast app.

4. Alexander the Great“More accounts of his life survive from antiquity than any other figure from Ancient Greek history but the paradox is that we actually know much less about about Alexander than we think we do.”

In this episode, Hugh Bowden introduces Alexander the Great, a legendary figure whose legacy permeates modern culture but about whom we still have much to discover.

Join Hugh as he pieces together the evidence to build a picture of Alexander III of Macedon—the first person in western history to have been given the title “The Great.”

Or subscribe and listen to the “Alexander the Great” Very Short Introductions podcast episode on your favourite podcast app.

Want to learn more? Subscribe to The Very Short Introductions podcast and see where your curiosity takes you!

Featured image via pxhere.com, public domain

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers