Oxford University Press's Blog, page 65

October 30, 2022

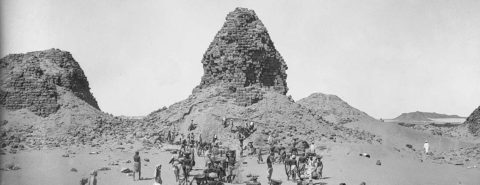

Exploring Ancient Egypt with Carter, Reisner, and Co. [interactive map]

The Ancient Egyptian civilization is regarded as one of the most iconic civilizations in history. It lasted for over 3,000 years, with the Nile River serving as a lifeline for small, independent city states to bloom along the river due to its agricultural predictability. As the fertile valley produced surplus crops, large populations thrived, leading to greater social development and culture.

Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign in 1798 inspired a burst of Egyptomania in Europe. Ever since then, many world scholars have attempted to discover the riches of the land, including American George Reisner, Egypt’s premier archaeologist of his era, and British Howard Carter, who discovered the Boy King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Travel back in time to Ancient Egypt and explore pyramids with hidden burial chambers, colossal royal statue, miniscule gold jewelry, and much more. Explore the interactive map below.

Featured image: Figure 14.3 from Walking Among Pharaohs by Peter der Manuelian. Excavations at Nuri Pyramid 6, looking local west, November 11, 1916. HU-MFA B2859 NS; Mohammedani Ibrahim.

Modern tantra and the global history of religion

For good reasons, tantra often stands at the center of debates about cultural appropriation and the commodification of religious practices. Through nineteenth-century orientalist studies and missionary polemics, it became associated with sexual licentiousness and abhorrent rituals before it was refashioned as a way to sexual liberation and individual freedom. While it is difficult to define what exactly “tantra” means, experts agree that it forms an integral and prominent part of Hinduism, another hard-to-grasp category encompassing a vast variety of teachings and practices. Clearly, the sensationalist and commercialized takes on “tantra” are at odds with the historical and doctrinal depth of the subject. Critics from the spectrum of postcolonial studies and classical Indology alike have thus rightfully pointed out the many flaws in common perceptions of tantra.

Yet, while postcolonial criticism in particular contributed to our understanding of how the meaning of tantra was shaped under the conditions of colonialism, it sometimes tended to eclipse “non-Western” actors in ways similar to Eurocentric scholarship, which assumed Europe at the center from which “modernity” diffused to a mostly passive “rest.” This issue is mirrored by the elusive subject of religion, the worldwide application of which is often perceived as the result of Western projection, Orientalist imagination, and (epistemic) violence. Are present-day understandings of religion and tantra the result of Western colonialism? Was “traditional,” precolonial tantra disconnected from its modern variant?

The situation is more complicated. Of course, understandings of tantra were significantly shaped within a colonial context, and it is crucial that our historiographies reflect that circumstance. Yet, those Indian (and other) actors who participated in debates about the meaning of tantra were not the passive recipients of Western knowledge. While most scholars today would subscribe to this statement, modern tantra is an instructive example of how “non-Western” actors are still often not taken into consideration in their own right.

“Modern tantra is an instructive example of how ‘non-Western’ actors are still often not taken into consideration in their own right.”

Today, tantra would hardly be as prominent—both among practitioners and academic scholars—without the writings of a pseudonymous “Arthur Avalon,” who established tantra as a serious object of inquiry from the 1910s until the 1930s. For long, it was thought that the British judge, John Woodroffe (1865–1936), had been responsible for this project. However, it was in fact a team of learned South Asians, mostly Bengalis, who did the work and happily presented Woodroffe as its figurehead. While many are aware of this fact, this local background of the Avalon collaboration has never been examined in its own right.

Doing so reveals a picture of complex and often ambiguous cultural exchanges. The region of Bengal, with its famous centers of learning such as Navadvip and Krishnagar, was in itself a rich cultural sphere where various Hindu, Muslim, and later European currents mingled: this is where Chaitanya heralded devotional Vaishnavism, where Shaiva-Shakta traditions elevated Kali and Durga to major deities of Bengal, where Mughal culture prospered, and where orientalists such as William Jones were trained. The tantras formed an integral part of learning in Bengal. In the nineteenth century, the pandit Shivachandra Vidyarnava (1860–1913) was among its most prominent defenders, praising tantra as the core of sanātana dharma, the unchangeable and eternal truth of the Vedas. Shivachandra was not only the guru of Woodroffe himself, but of several of the collaborators on the Avalon project—among its first publications was Principles of Tantra (1914/16), a translation of Shivachandra’s magum opus, Tantratattva.

“If we understand that present (re-)negotiations of ‘tantra’ or ‘religion’ are global, then we must acknowledge that their histories are, too.”

At the same time, those who collaborated on Avalon were not only shaped by this cultural sphere but also by British-European education and ideas. They engaged with prominent contemporary movements, such as the Theosophical Society. Again, previous scholarship has viewed the activities of this society, which had been founded in New York in 1875 and shortly after relocated to India, in terms of a diffusion of “Western esotericism.” However, Theosophy entered a complex intellectual landscape and became subject to Indian debates. Its search for the origin of “Aryan civilization” in India led to a particular interest in tantra, which Shivachandra and his disciples presented as the “esoteric” essence of the Vedas. Not least through Theosophical and other “esoteric” channels, tantra and related subjects like yoga were transmitted to Europe and elsewhere, leading to the prominence it enjoys today.

This was not the result of a “meeting between East and West,” nor a conflict between modernity and tradition. Nor was it the outcome of a romanticized, peaceful process, as these exchanges did unfold within the context of colonialism and went hand in hand with nationalism, struggles, and the ambiguity of racial theories such as Aryanism. The activities of the Bengali tantrics behind Avalon illustrate how we need to take into account both local, diachronic developments reaching back to the precolonial period and the global connections that continuously shaped them. If we understand that present (re-)negotiations of “tantra” or “religion” are global, then we must acknowledge that their histories are, too. The approach of global religious history is one attempt to grasp these complexities.

Featured image used with the author’s permission.

October 29, 2022

Vernon Lee, history, and horror

Some of the most acclaimed films to come out of the horror mini-boom of the past decade—Robert Eggers’s Witch (2015) and The Lighthouse (2019), Ti West’s X and its prequel Pearl (both 2022), and Goran Stolevski’s You Won’t Be Alone (2022) come to mind—mix history and horror in disconcerting ways. Of course, these are not the first scary movies or stories do this. In the early twentieth century one thinks, for instance, of weird fiction by Marjorie Bowen, M. R. James, and William Hope Hodgson, among others. But when, and how, did horror first get historical?

Interestingly, history and horror, it might be said, were born at the same time, fraternal but far from identical twins gestated some 250 years ago in the womb of the European Enlightenment. This needs qualification. I refer on the one hand to modern historiography—as an emergent discipline bringing new methods and standards, as well as a new emphasis on cultural production, to bear upon the study of the past—and on the other to the Gothic novel, a genre which appeared as a kind of counter-reaction to the prevailing rationalism of the age. Gothic fiction was similarly obsessed with, and often set in, the historical past. But “history” is a murkily imprecise thing indeed in the novels of Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe, and their successors—miles away from the rigorous conception of history evident in the works of such contemporary figures as (say) Voltaire and Edward Gibbon. Over the next century or so, both historiography and early horror fiction continued to evolve both separately and, gradually, in conjunction, as a few writers attempted to integrate a nineteenth-century historical consciousness into the writing of weird fiction (Elizabeth Gaskell is one such pioneer).

Enter Vernon Lee. Born Violet Paget in 1856 on the French coast of the English Channel, Lee grew up in France, Switzerland, Germany, and Italy, and apart from a brief childhood visit, she did not travel to England until she was in her mid-twenties. She began writing in her early teens, and never stopped: by the time of her death in 1935, she had authored essays and books on art, language, psychology, travel, and myriad other subjects, as well as works of fiction and drama. In short, Lee was a true polymath, who over the course of a long writing career produced outstanding work in a wide range of intellectual fields.

It is primarily her (relatively infrequent) forays into the Gothic and fantastic, however, for which Lee is remembered today. She has long been highly rated by connoisseurs of the horrible—Montague Summers wrote in 1931, “Hauntings is a masterpiece of literature, and even [Sheridan] Le Fanu and M. R. James cannot be ranked above the genius of this lady”—but her nonpareil Gothic tales have never really broken through to a wider audience; nor has she ever been given her due as an influencer (as we say today) within the genre. It is often pointed out that she was influenced by her friend (or better, to use another twenty-first-century epithet, frenemy) Henry James, but it seems to me possible—even probable—that James’ “The Master” was inspired by Hauntings, which Lee had sent him in 1890, as he declared it “gruesome, graceful, genialisch [ingenious]”, and helped a return to fantastic writing after a decades-long hiatus. His 1897 masterpiece The Turn of the Screw in particular has a great deal in common with Lee’s earlier novella A Phantom Lover—also known as Oke of Okehurst—not least its disconcerting ambiguity (are its ghosts real, or the psychological projections of a disturbed mind?).

“She sought to reproduce in her stories that same sense of total immersion into a vanished past.”

But first, and arguably foremost, she was an historian: her first book, published when she was only 24 and titled Studies of the Eighteenth Century in Italy (1880), was a deeply learned, insightful, and well-received example of the new discipline that we call “cultural history,” a branch of historiography pioneered by the Swiss historian Jakob Burckhardt, whose great study The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy (1860) was a major influence on the young Violet Paget. She had first become obsessed with the art, music, literature, and history of eighteenth-century Italy while rambling through Rome and Bologna with her childhood friend John Singer Sargent (the future painter) and his family, writing later of her profound immersion in that lost world: “The eighteenth century existed for me as a reality, surrounded by faint and fluctuating shadows, which shadows were simply the present.”

It is little wonder, then, that when Lee turned her hand to supernatural fiction, she sought to reproduce in her stories that same sense of total immersion into a vanished past, particularly that of her beloved Italy. Sometimes, as with the conte cruel “A Wedding Chest”, a scrupulously reimagined historical moment serves as setting for the tale; other stories, such as “The Virgin of the Seven Daggers” and “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady”, blend history and fable with often ironic effect (one might call these “historified” fairy tales).

Lee’s richest and most unsettling fictions, on the other hand, tend to shuttle between past and present, featuring modern protagonists whose engagements with history end in disaster. In this category we would place, for instance, her first attempt at a Gothic tale, the rather awkwardly titled “A Culture-Ghost; or, Winthrop’s Adventure” (first published in Fraser’s Magazine in 1881), as well as her thorough revisioning of the story, “A Wicked Voice”, which originally appeared as “Voix Maudite” in the French journal Les Lettres et les Arts in 1887. Both stories center upon a modern (i.e. late nineteenth-century) protagonist who finds himself the victim of an uncanny voice from the past, haunted by the bewitching song of a castrato singer from the previous century (loosely modelled after the superstar soprano Carlo Broschi, AKA Farinelli). Then there is the protagonist of “Amour Dure”, a young historian engaged in researching the counterfactual city-state of Urbania, who finds himself ensnared by a long-dead femme fatale, the Renaissance beauty Medea di Carpi, who reaches out to him across the centuries through a variety of media, dragging him to his doom.

The past (as the old saw has it) is a foreign country—they do things differently there. At its best, historical horror foregrounds this strangeness, exploiting the radical otherness of the past to establish and intensify a potent atmosphere of dread and unease. And no one, before or since, has ever been able to do this with as expert a hand as Vernon Lee.

Featured image by Bee Felten-Leidel via Unsplash, public domain

LGBTQ+ Victorians in the archives

The first challenge that confronts researching LGBTQ+ Victorians in the archives is the question: where to look? Typically, we know of LGBTQ+ people from medical records and legal transcripts, neither of which can be read as value-neutral. Even at the time, advocates recognized this difficulty. In his privately-circulated A Problem in Modern Ethics from the 1890s, for instance, John Addington Symonds worried that our understanding of homosexuality skewed towards what we now think of as situational (as opposed to congenital) same-sex experience because one of the most accessible populations to survey were those in prisons. The poet and activist Edward Carpenter similarly felt that groundbreaking work in Germany by the psychiatrist Albert Moll over-emphasized the presence of cross-gender expression because the police had steered him towards male prostitutes as his study’s main cohort.

The situation is, if anything, worse when we try to find people in the archives that could now be considered transgender. To the extent that we know of such people—some figures I focus on include Eliza Edwards, Frederike Blank, Fanny Park, and Stella Boulton—their existence is dependent on legal records and the documentation of physical exams, sometimes post-mortem, as the only evidence that each was affirmed male at birth. What we don’t and can’t know about is the quietly successful lives of those who accomplished a social transition and were never exposed—a point that Jen Manion has made in her excellent recent study of female husbands, who were only known after somebody registered a complaint and initiated an inquiry into their gender at birth.

Among other things, this reliance on medical and legal archives casts the entire topic in the mode of tragedy, promoting the idea that all queer people were eventually found out and punished. It doesn’t help if we see the nineteenth century as progressing inexorably towards the trial and conviction of Oscar Wilde, which conveniently occurred in the last half decade of the century. 1895, I argue, has become a fixed terminus around which we’ve tended to organize LBGTQ history. This can blind us to ways that the law wasn’t always triumphant, as I document in recording two striking failures.

“Reliance on medical and legal archives casts the entire topic in the mode of tragedy, promoting the idea that all queer people were eventually found out and punished.”

The first is the libel suit brought by two Edinburgh schoolteachers, Jane Pirie and Marianne Woods, who were accused of “unnatural” sexual relations while in loco parentis, a counter-charge which (in stark contrast to Wilde’s) was ultimately successful. The other is the trial of Boulton and Park, who were accused of conspiracy to commit sodomy based mainly on their cross-gender presentation. Their exoneration underscored the important legal conclusion that gender expression was not in itself an actionable offense—but you wouldn’t know this from historians of sexuality who have tended to assume a) that they were guilty as changed, and b) that the embarrassment caused by their victory led to a tougher legal approach in the case of Wilde, which took place a quarter century later. Disentangling the two cases from each other, however, can help us to see that they have little to do with each other. However, we can only do so if we can understand that Fanny and Stella are better understood as embodying very different people in the LGBTQ+ coalition: not cross-dressing gay men but something much closer to modern trans women.

I make this argument based mainly on more “private” documents (especially letters between them) that indicate what we’d now see as a persistent, consistent, and insistent desire to live as women—though ironically, those letters are also accessible to us now only as evidence in their trial! This of course highlights the paradox and difficulty of doing this work of archival reconstruction: without the trial, such letters would almost certainly been lost to history; because they exist, however, they form the earliest OED entries for the word “drag”.

That this is a fragile archive should be obvious, and it’s in many ways a miracle that some of it has survived. I think of Anne Lister’s diaries, which have upended what we know about nineteenth-century lesbianism and are now part of Unesco’s “Memory of the World” registry—as well as the source for the successful TV series Gentleman Jack. Lister wrote her diaries in part in a cryptic code she could never have imagined anyone would crack, and she hid them in a paneled room where we had no right to find them—much less begin a process of transcription over a century later that is still ongoing. Similarly, Symonds’ memoirs were written in secret and given to a friend with directions only to publish if they wouldn’t cause offense to his wife and daughters. Like the Lister diaries, they were locked away, waiting and hoping against the odds for a future moment when we would be interested enough to disinter and make use of them.

Featured image: cover jacket from Simon Joyce’s LGBT Victorians: Sexuality and Gender in the Nineteenth-Century Archives

October 28, 2022

The March on Rome: commemoration or celebration?

Despite subsequent legend, in military terms the March on Rome was a shambles. In the pouring rain, poorly armed and badly organized, the fascist blackshirts cut a sorry figure as they trooped, unopposed, through the streets of the Italian capital. But politically the March was a bomb-shell, the explosion of which resonated not only in Italy but throughout Europe. Certainly, in other countries armed and violent militias had sprouted in the confusion of post-First World War Europe, but none had succeeded in gaining power so dramatically. When the king—Vittorio Emanuele III—decided not to invoke the intervention of the army, he effectively capitulated to the mob and thereby ensured Mussolini’s success (and, 24 years later, the end of the monarchy in Italy).

Some historians have tended to downplay the importance of the March on Rome—”little more than choreography” according to some, and, of course, the absence of open battles gives weight to this point of view. However, the March should be seen in its full context. It was the crucial ratification of the fact that much of Italy had been out of the control of the authorities of the liberal state for many months. In many provinces of northern and central Italy, the fascists already exercised almost complete de facto control. As Italo Balbo, the leader of the fascists of Ferrara, boasted in early 1922, “The prefect does what I tell him.” In the hours preceding the March this position of strength was made evident with blackshirts occupying prefectures, police stations, post offices, telegraph offices, and railway stations throughout much of Italy. They faced little opposition. What the March really tells us is that the government of the liberal state—that is, the political system that had governed Italy since Unification—had abdicated power to an eversive movement, not because of a military confrontation, but because the enormous stress of the war had severely weakened the capacity of the state to withstand the challenge posed by the fascists. In a society radically changed by the experience of the war, the old politics of pre-1914 found itself lacking.

“The March was the crucial ratification of the fact that much of Italy had been out of the control of the authorities of the liberal state for many months.”

Not that the nature of the challenge was obvious to many. Fascists waved the national flag, sang patriotic songs, swore loyalty to the crown; many continued to wear their army uniforms. Creating disorder as they killed, maimed, and forced opponents (particularly socialist opponents) into exile, they claimed persistently to be the representatives of order. Inevitably police and regular army officers tended to be complicit with the creeping take-over of power that the fascists had affected from 1921 onwards. Who was going to shoot at ex-combattents with strings of medals pinned to their chests? Only a few, more far-sighted commentators, among them Antonio Gramsci, saw that Mussolini was moving towards dictatorship.

The March on Rome would become one of the great founding “myths” of the fascist movement, with a glorification which went far beyond its rather ramshackle reality. It was presented by fascist propaganda as the moment of the fascist “revolution,” the watershed between the old and the new politics, between the drab past of “little Italy” and the dazzling future of what was going to be a new great power on the European scene. Throughout the twenty years of the regime the March remained central to fascist mythology; it was the event that most expressed the fascist spirit, the event that sustained the legend of the heroic blackshirts saving Italy from the Bolshevik hordes. Its success constituted the legitimation of fascist violence. As a watershed between eras it was also used to distinguish between fascists; there were those who had belonged to the movement before the March, who merited particular respect and enjoyed appreciable privileges, and those who were post-March. Such was the prestige of the pre-Marchers that, by the mid-1930s, there was a lively market in false party cards dated to the months before October 1922.

Throughout Europe reaction to the March was, inevitably, mixed, with some appalled by the violence and the total disregard the fascists showed for parliamentary politics, while others—such as those among British conservative opinion—thought that the fascist government would bring much-needed “order” to what they condescendingly saw as typically Mediterranean chaos. Many right-wing European politicians looked on Mussolini and to his mode of achieving power with admiration. One man in particular was greatly impressed by the March on Rome and even hoped to emulate it. This was Adolf Hitler.

“The March on Rome would become one of the great founding “myths” of the fascist movement, with a glorification which went far beyond its rather ramshackle reality.”

Where are we now—a hundred years on? Certainly the bookshops are full of new books on the fascist seizure of power; interest (at least among publishers) is not lacking. But, at a broader level, within Italy, reactions seem muted. There is little sense that the March represented the begining of the tragedy that cost Italy more than half a million dead. It has become a historical event that remains, somehow, with few reverberations. This lack of reaction mirrors a wider phenomenon, which is the increasingly indulgent attitude evident in Italy towards the fascist regime and, in particular, towards its leader. It is apparent in such phrases as “Mussolini did many good things,” “Mussolini was not like Hitler,” or “Mussolini made one mistake” (referring to the alliance with Hitler). There has been, as one Italian historian has put it, a “defascistization of fascism” in popular memory—a tendency that draws sustenance from the way in which the regime continues to be seen by many through the lens created by the propaganda of the regime itself. Drained marshlands, trains on time, and (heavily organized) mass rallies trump violence, corruption, and war every time. And Mussolini seems to be regaining some of his undoubted charisma. The picture of fascism currently present in many quarters is often comforting, even nostalgic, rather than alarming. It evokes the virtues of the “strong man” and the “firm hand”—the apparent virtues of authoritarian government. Small wonder that, in the confusions and uncertainties of the contemporary world, these “virtues” are increasingly appealing.

October 27, 2022

Transparency in open access at OUP

Open access (OA) delivers many benefits—chief amongst them immediate access to the latest research and the ability to liberally re-use and build upon that research. The recent White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) memorandum signified a major push towards opening up federally-funded research in the United States. In outlining the potential impact of increasing access to research, the OSTP stated that the policy would “likely yield significant benefits… from environmental justice to cancer breakthroughs, and from game-changing clean energy technologies to protecting civil liberties in an automated world.” Over the last 10 years the promise of these benefits, and the demonstrable impact of open research in (for example) aiding the quick development of COVID-19 vaccines, has helped make open access the dominant factor in the discourse around the future of journals publishing.

A culture of openness does not end with access. As the core benefits of OA have become generally accepted, there has increasingly been more focus turned to accompanying discussions around openness in research and what that means not just for how research is disseminated, but how it is described, conducted, validated, and funded. All of these lead naturally to a conversation about transparency.

The change of publishing model from subscriptions to OA presents an opportunity to start afresh, with open information available about how OA journals and publishers operate and charge. A clear example of this is the ESAC database—which hosts details, and often the actual contracts of more than 500 “transformative” agreements between academic institutions and publishers. The ESAC database represents the opening up of previously confidential information about sales agreements in support of greater transparency and enables anyone to understand how publishers’ “transformative” or “read and publish” agreements with academic customers work.

As a not-for-profit university press which publishes over 75% of its journals on behalf of scholarly societies and other organisations, OUP is committed to a transparent approach to OA. The transition to OA can appear opaque, steeped in jargon and complexity, and we see a major part of our role in the move to OA as being as open and clear as possible. For example:

We fully support institutions making our transformative agreements available on ESAC. You can find details and contracts of 25 OUP agreements on the database.Our article processing charge (APC) pricing is simple and is transparently available on our website. We have one main price per journal, in one currency. Some journals offer discounted rates for members or shorter article types. Authors who wish to pay in another currency can do so at the current exchange rate. We have an extensive and clear APC waiver policy. Corresponding authors from more than 100 low and middle-income countries are eligible for a 100% waiver of their APC on our fully OA journals. We also offer discretionary waivers for authors who are not based in these countries, but who are unable to pay APCs for their article. Working with our society partners and our customers, we seek to demystify transformative agreements and the move to OA by providing clear and transparent reporting, both of publishing and financial data.Through our participation in Coalition S’s transformative journals programme, we provide annual reporting on the progress of these journals to OA. Five of the six journals included in the programme have already changed into fully OA journals, or will do so in 2023. Over 400 of our journals have data availability policies in place, ranging from asking authors to publicly release the data underlying their paper, to requiring them to do so as a condition of publication.We realise there is much more to do, and over the coming weeks and months we aim to further increase the information available. The following are six steps we’ll be taking to share our work toward transparency in OA:

In the last quarter of this year we will begin moving our transformative agreements, OA licensing, and publication charges to Aptara’s SciPris platform. A crucial focus of this move is to simplify and clarify the OA experience for our authors. Reporting more regularly on the number of papers for which we waive APCs and for what reasons. With a large portfolio of individually managed journals, this information has not always been easy to prepare, but we want to push through the challenges of data collection as this is an important and underreported area of OA publishing.More frequent blog posts on our transition towards open access, sharing our experiences.Updating our webpages to more easily guide authors and users to information about our OA and open research programme.Expanding our data availability policies to more journals, and to higher levels of availability. Continuing to engage with initiatives in research transparency such as publishing registered reports and transparent peer review, building on the success of journals already adopting these initiatives within our portfolio.OUP publishes over 500 high-quality journals, the large majority of which are published on behalf of scholarly societies or other academic organisations, and all of which undertake extensive and rigorous peer review to ensure the highest quality of research.

As we realise the benefits of open access, we want to do so in a way which protects the long-term sustainability of our journals, our customers, and the societies we work with. Balancing our desire to be as open as possible with the complexities of changing the business model of our journals is of course a challenge—but it’s an exciting challenge, with a very positive end goal. We see transparency as an important way in which we can meet that challenge, and look forward to continuing to share information over the coming years.

Featured image by Ralph Chang, via Pexels, public domain

October 26, 2022

Hue and cry, or the mystery of red gold

As a student, I read Homer in English and ran into the phrase wine-colored sea. At that time, I did not know that in Old English, waves were sometimes called brown and only wondered what kind of wine the Ancient Greeks drank. No one in my surroundings could enlighten me. Since that time, I have read many articles and books on the history of color perception and in 2014 even reviewed a treatise on this subject in Old Icelandic. I had already known that in old literature, the most exotic colors could describe the objects around us. I had also met two scholars specializing in the use of color words in old literature and was thus no longer a greenhorn. In this blog, our readers will find my posts on brown à propos in a brown study, at one time slang, later used even by Huck Finn (!), and today probably remembered mainly by speakers of British English (Agatha Christie often referred to Hercule Poirot being in a brown study), and gray ~ grey (the posts for 8 January 2014 and 24 September 2014).

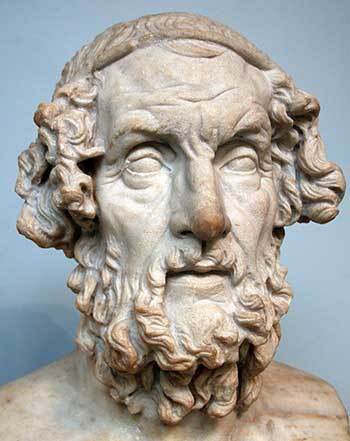

Homer, a man of rare vision.

Homer, a man of rare vision.(British Museum, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

In addition to those essays, I have always wanted to write about the enigmatic phrase red gold. It is ubiquitous in Old Germanic and in Slavic poetry. For a long time, I have kept an article on this subject in my etymological database, and today I’ll retell it. My source is “The Semantic Puzzle of ‘Red Gold’” by Earl R. Anderson (English Studies 81, 2000, 1-13). There can be little doubt that the structure of the human eye has not changed since the days of Homer. It is unimaginable that such a dramatic event in the evolution of the human eye should have happened so recently. But even if there was any merit in that hypothesis, it would be unable to explain why gold was called red. Our characterization of color is a matter of culture, not physiology.

It is equally obvious that people can distinguish any number of hues. Also, sometimes oblique associations produce unexpected results. Thus, nearly everybody believes that livid means “red” because the only context in which we use livid is livid with fury (rage, anger). But livid means “bluish gray.” In Old Norse, the moon was once called red, and butter emerged as green. While studying English idioms, I failed to find an explanation of the phrase once in a blue moon. I have a long list of such curiosities, which should not be confused with obvious metaphors, such as green (= “young”) years.

For starters, in order to increase our puzzlement, let us bear in mind the fact that from a historical point of view gold (in Germanic and beyond) has the same root as the adjective yellow, rather than red. In Russian, it is rudá “ore” (with cognates elsewhere in Slavic) that shares the root with Germanic red (which makes sense). And yet gold, not ore, in defiance of common sense and etymology, was called red.

This is ocher.

This is ocher.(Marco Almbauer via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Some investigators believed that the phrase red gold was a mere poetic convention. Sure enough, this phrase functioned as a formula, but gold was often called red also in prose. Moreover, the formula did not die with the demise of old alliterative poetry. The locution bothered no one even in thirteenth-century rhyming texts (Old Germanic poetry depended on alliteration and the rhythmic patterns that did not outlive the oldest period; with one exception, it did not rhyme). Gold in the Middle Ages, it has also been argued, was often alloyed with copper, resulting in reddish coloration. However, it is improbable that such a similarly unimportant fact could engender a standard, universally accepted formula.

Long-lived and stable is also the notion that color words in old languages referred to brightness, rather than hues: supposedly, red gold meant “bright gold.” According to this notion, white, brown, and fallow (I am citing the modern forms of the Old English adjectives) also emphasized the sheen produced by the objects described. In addition to Earl R. Anderson’s objection, I wonder why Old English (and many other Germanic and non-Germanic languages) needed so many color words to refer mostly to brightness. Red, as Anderson notes, was applied in Old English to boundary stones, cliffs, ditches, a ridge, a path or road, a wallow, a spring, a ford, and a pool. He draws an important conclusion: in all such cases, red evokes an earthen or mineral color. I’ll skip some other solutions whose discussion would require a detailed analysis of rather obscure arguments and mention only one more. Allegedly, very long ago, red referred to a covering exemplified by gilt, paint, and ocher dust. In the phrase red gold, we are told, the essential idea is that gold is a covering, with its chromatic value being secondary. This observation is true, but not all the occurrences of red in old texts can be explained with this reference.

Many happy returns of the day.

Many happy returns of the day.(Photo by PxHere , public domain)

Anderson concentrated his attention on the role of ocher in the history of civilization. “For Paleolithic and Neolithic cultures, ocher was just as important in the material culture as was the use of tools: the objects themselves, and knowledge of the technology associated with them, were preserved with care and passed from one generation to another.” He drew the conclusion that red was mainly earthen, mineral, or metallic in its focus, while yellow focused on the colors of vegetation and thus resembled green. For modern speakers, he continues, red evokes the idea of blood, while in olden times, it made people think of ocher. In old texts, blood was called red, among other things, but gold was always known as red. The paper ends on a note of caution: Anderson was fully aware of the difficulties of the theme he discussed. I find his reasoning most interesting but still wonder why gold has the same root as yellow. It may also be that I missed the subsequent discussion of the paper, though I have looked through the entire set of the journal in which it was published.

The purpose of this post is once again to call the attention of our readers to one of the most enigmatic questions of culture, namely, the use of color words in the history of civilization. What follows is an embarrassing anticlimax. Three times in the periodical Notes and Queries (in 1880. 1888, and 1927) and once in Scottish Notes and Queries (1905), the aforementioned idiom once in a blue moon was discussed. No hypotheses about its origin were proposed, except that the phrase might be coined as an example of an absurdity, like the “belief” that the moon is made of green cheese.

Left: Cambridge Blue. Right: turquoise.

Left: Cambridge Blue. Right: turquoise.I hope that the roots of this odd phase run at least an inch deeper than that, but at the moment, I can reproduce only the following excerpt: “The Times of June 14 [1927] says in speaking of the delayed arrival of the monsoon at Bombay— ‘A curious and rare phenomenon was observed last night when the moon was seen to be distinctly blue. The Times of India says that the colour appeared to be between Cambridge blue and turquoise’. Can it be said that the expression ‘once in a blue moon’ has its origin in the rareness of this phenomenon?” The OED does not seem to have a pre-1833 citation. Thus, with this phrase we are certainly not in the Middle Ages, and one wonders why this idiom has become so well-known. Incidentally, idioms with blue are rather numerous. Perhaps some meteorologists among our readers will enlighten us on this subject. The OUPblog will repay their help with the red gold of eternal gratitude.

Featured image: The Fishpool Hoard, photo by Colin McLaughlin, British Museum, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

October 25, 2022

Egyptology at the turn of the century [podcast]

On 1 November 1922, Egyptologist Howard Carter and his team of excavators began digging in a previously undisturbed plot of land in the Valley of the Kings. For decades, archaeologists had searched for the tomb of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun with no success, and that November was to be Carter’s final attempt to locate the lost treasures. What Carter ultimately discovered—the iconic sarcophagus, the mummy that inspired whispers of a curse, and the thousands of precious artifacts—would shape Egyptian politics, the field of archaeology, and how museums honor the past for years to come.

On today’s episode, we discuss the legacy of early twentieth-century Egyptology to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

First, we welcomed Bob Brier—one of the world’s foremost Egyptologist, and an expert in mummies who is one of a few scholars who have had the opportunity to investigate Tutankhamun’s mummy—as he discusses his new book Tutankhamun and the Tomb that Changed the World and the 100 years of research that have taken place since the tomb’s discovery. We then spoke with Peter Der Manuelian, the author of Walking Among Pharaohs: George Reisner and the Dawn of Modern Egyptology, to discuss Reisner’s life, the rise of American Archaeology in Egypt, and the archeological field’s involvement in nationalism and colonialism.

Check out Episode 77 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Egyptology at the Turn of the Century – Episode 77 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingTo learn more about the themes raised in this podcast, we’re pleased to share a selection of free-to-read chapters and articles:

Earlier on the OUPblog, we shared an interactive map showing some of Reisner’s and Carter’s key discoveries. Included in the map are photos of some of the amazing artefacts as well as excerpts from Tutankhamun and the Tomb that Changed the World and Walking Among Pharaohs: George Reisner and the Dawn of Modern Egyptology.

From The Oxford Handbook of Egyptology, read about the nature of history and Egyptology.

You can read about the exploration of the Valley of the King’s prior to the late Twentieth Century in The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings.

To learn more about the phenomenon of Egyptomania that has spread through the 20th and 21st centuries, you can read a chapter from Ian Shaw’s book Ancient Egypt: A Very Short Introduction.

Learn more about the discovery of Howard Carter’s letters confirming the theft of artefacts in this recent piece from The Guardian.

The greywacke statue of King Menkaura and the painted coffin of Djehutynakht, two of George Reisner’s discoveries mentioned by Peter Der Manuelian, can be viewed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Lastly, Bob Brier mentioned one of the most famous Saturday Night Live skits, Steve Martin’s “King Tut” song from 1978:

Featured image: “Howard Carter in the King Tutankhamen’s tomb, circa 1925” by Harry Burton, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

COVID-19 and the London restaurant: a Victorian perspective

The last two years have proved the restaurant business is nothing if not adaptable. In my residential London neighbourhood, a popular Indian restaurant quickly moved to take-away meals once the first wave of the pandemic hit, a pattern many other businesses followed in a fight for survival. Theirs is a small-scale, family operation; factors that helped them weather the storm, especially once the pattern of work and schooling became home-based. Reopening was initially arms-length, socially distanced dining in whatever outdoor space could be provisioned, accompanied, in the case of my local pizzeria, by air-kisses and fist bumps from Salvatore, the head waiter there. Two years on, the pizzeria is flourishing again. However, across the street, another restaurant never reopened, and remains a forlorn spectacle of stacked dining room chairs and a single faded menu displayed on a grubby window facing the high street. Such contrasting fortunes were repeated across London, and indeed the rest of the country.

The crisis created by COVID-19—coinciding as it did with the dislocation caused by Brexit—dramatized in extreme form the volatility that is ubiquitous in the restaurant sector. This is as true of the historical past as it is of the present.

In Victorian London, when the restaurant in its modern form evolved, public eating was always a precarious enterprise. When Steffano Gatti, owner of a chain of refreshment rooms, died in 1906, he left an impressive estate of around £220,000, while Edwin Levy of the J. Lyons and Co. chain had an estate valued at £260,000 on his death in 1895. By contrast, restaurants were a regular presence on the auction block. Size, longevity, and capitalisation were no guarantees against restaurant closure. Lucas’s Luncheon and Dining Salon in Westminster closed in 1890 after Mr Lucas occupied the premises for 30 years. The Daily, which opened in the City in 1877, was already on the auction block a year later. The elaborate fitting and redecoration of the Tivoli on the Strand in 1888 was insufficient to see off its demise three years later. As is the case today, a major cause of restaurant closure was the expiry of leases and rising rents, but establishments also fell afoul of changing tastes, and the attention of health and hygiene inspectors.

Victorian London’s innovative restaurant sceneAs in the present, Victorian restaurant proprietors negotiated this dizzying culture of risk and reward by constant emphasis on adaptation and innovation. While some modest dining establishments seemed to have dodged the vicissitudes of the market, rarely changing either their fare or furniture, the dominant trend was to remain contemporary and, where applicable, modish. The range of initiatives taken to attract and retain customers by Victorian restaurant owners and managers was remarkable and bears comparison to the ways in which restaurants today align themselves with shifts in popular culture and exploit the novel opportunities of the digital age.

Technological innovations in the Victorian restaurant included the increased use of refrigerators in kitchens and electric lighting in dining rooms. The current fad for allowing diners to order and pay for their meal using an electronic tablet or mobile phone might be seen as little more than another stage in a practice that began with the widespread deployment of the cash register in the last years of Victoria’s reign. The cash register was imported from the United States, not only to expedite payment by customers, but to allow proprietors to uncover fraud among their employees.

The appliance that most fully registered the intersection of the expanding restaurant sector with modernity was obviously the telephone, which not only facilitated easier contact with suppliers, but also allowed customers to book tables. Nathaniel Newnham-Davis, usually identified as the first modern restaurant reviewer, used the telephone to make a booking at the Savoy, even if he felt it necessary to immediately take a cab there to ensure that both the table and the menu would be satisfactory when he returned later that evening with a female companion. As the cash register and the resort to electric kitchen appliances imply, innovation was as much about reducing overheads as it was about satisfying the comfort and convenience of customers. Restaurant proprietors rose to the challenge of the rising cost of provisions, especially meat. The restaurant behemoth Spiers and Pond offered the most dramatic response to this problem by setting up its own slaughterhouses in Deptford and Islington.

The “celebrated chef” in Victorian LondonApplying the term “celebrity chef” to the nineteenth century is unhelpful, not to say anachronistic. The most rarefied professional cooks—such as Antonin de Carême, Alexis Soyer, and Auguste Escoffier—were more likely to be found at state banquets, royal palaces and aristocratic townhouses than they were in restaurants. However, we should acknowledge the significance of what was termed in the 1890s the “celebrated chef.” Men such as Louis Peyre, who migrated from the grand hotels of Paris and the Riviera to London, restored the degraded reputation of the Charing Cross Hotel by modernising its cuisine. Diners at the Circus restaurant in Oxford Street were undoubtedly attracted by the presence of head chef Gabriele Maccario, an esteemed figure in the world of Italian cookery.

The presence of foreign chefs underlines the fact that London’s restaurant cuisine was remarkably polyglot, and it would be wrong-headed to assume that the dynamism and heterogeneity of the capital’s restaurant culture is a novel product of post-WWII immigration and early twenty-first-century globalization. If London’s inhabitants were offered meals with an international hybrid inflection, conversely restaurants were no less alert than they are today to the rewards of attracting visitors from abroad. Restaurants advertised in published guides to London, newspapers (in a variety of languages), and on handbills available at major hotels.

More generally, restaurants with name recognition, such as the Trocadero or the Holborn restaurant, embraced what was already being termed in the 1880s the “science of advertising,” publishing their own in-house illustrated souvenir booklets. Novel advertising initiatives included projecting lantern slides onto adjacent buildings or displays of live turtles in restaurant windows (to be made into turtle soup later).

Unprecedented challenges in the restaurant sector?The restaurant sector remains a highly volatile element within the service economy, characterised by an often-breathless cycle of opening, expansion, contraction, and closure. However, it clearly wasn’t that much different in the past. The magnitude of the challenges posed by COVID-19 and Brexit might seem unique. In fact, the restaurant sector confronted a no less seismic event in 1914 when the outbreak of the First World War not only disrupted patterns of supply and consumption, but more specifically led to an exodus of foreign-born staff and management (specifically, from the Continent), who had been such a vital component of London’s dining culture in the late Victorian period.

We need to be wary of those who overstate the novelty of the times in which we live. To take one final (but illustrative) example: the popularity in recent years of the food truck is undoubtedly a growing recognition of the street food cultures of the Americas, Asia, and Africa. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the food truck was a beneficiary of the requirements of social distancing and the narrowing of the gap between restaurant income and rents. However, we should not forget that the food truck is also the heir to the pie-man, coffee stall, and Italian ice cream sellers of nineteenth-century London.

Featured image from the cover of The London Restaurant, 1860-1914.

October 24, 2022

The Mahatma and the Policeman: how did George Orwell view Gandhi?

In the mid-1920s, in Burma, a young officer of the Imperial Police was reading in an Indian newspaper an instalment of the autobiography of the most famous man in India. Years later, he remembered the moment and his mixed feelings:

At about the time when the autobiography first appeared I remember reading its opening chapters in the ill-printed pages of some Indian newspaper. They made a good impression on me, which Gandhi himself, at that time, did not.

It is no surprise that Gandhi himself was not popular with British officials in the Raj. He, and the Congress Party with which he was associated, had for years been a thorn in the side of the imperial authorities, and were in the vanguard of the movement to force the British to quit India. In British Burma, nationalists looked to India for inspiration and sometimes support in their own struggle. Every imperial policeman in Burma was aware of Gandhi as the figurehead of this rebellious spirit, as well as a wily political operator who kept finding new ways to get under the skin of the government of British India and its disciplinary forces. If Gandhi did not make a good impression on the young policeman, whose name was Eric Blair, that hostile perception was maintained, for the most part, throughout the subsequent career of George Orwell, the writer he became. Yet on the face of it, this was surprising.

Gandhi and Orwell were implacable enemies of the injustice of imperial rule and worked to change the minds of those who sustained it. This campaign came to a climax with the end of British rule in India in 1947, which both lived to see. So what was it that prevented Orwell from seeing in Gandhi a kind of ally, a comrade in arms, even a hero? Through his career, in which he wrote a good deal about Gandhi, he expresses suspicion, hostility, irritation, “a sort of aesthetic distaste,” and at best a grudging respect for the older man. Why?

The socialist anti-imperialist George Orwell did not cease (though he tried) to be an Anglo-Indian in many of his instincts and responses. Particularly when war came in 1939, he rediscovered in himself what he called “the spiritual need for patriotism and the military virtues.” Later, in 1942, when Britain and its empire were beleaguered, with victorious Japanese forces sweeping through Burma to the gates of India, he was exasperated that Gandhi and his allies would not co-operate in the defence of the country, instead demanding that the British quit India without delay. Orwell believed this would be tantamount to handing India over to the Emperor of Japan. The British immediately locked up Gandhi and the Congress leaders, setting back by several years the possibility of co-operation over India’s future.

Orwell also thought that, in the 1940s, a pacifism like Gandhi’s was culpably naïve. Civil disobedience was all very well against the British in India, “an old-fashioned and rather shaky despotism,” but would be a hopeless tactic against a ruthless dictator. What action would Gandhi have recommended for the European Jews? The answer was on the record. “The Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher’s knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs.” This, in Gandhi’s view, would have aroused the world to the evils of Hitler’s violence.

Orwell said he remembered that, during his time in the Indian police, many Englishmen thought Gandhi was actually useful to the Raj. His advocacy of non-violence, they argued, always worked against translating anti-British resistance into any effective action, and meanwhile he “alienated the British public by his extremism and aided the British Government by his moderation.” Besides, Orwell found his religious views suspect, and in the end coercive. Gandhi was like Tolstoy, he grumbled, a utopianist whose basic aims were anti-human and reactionary.

Yet at the end of the day, he had to admit Gandhi was more responsible than anyone else for bringing about the end of British rule in India, the first and crucial step in the relatively peaceful dismantling of the empire. Orwell the anti-imperialist had desired this above all, and knew it could only be brought about by the action of imperial subjects, while Orwell the Anglo-Indian had never quite believed that the subject peoples themselves could ever make it happen. Even after the death of the Mahatma in 1948, Orwell couldn’t really make up his mind. In his last essay on Gandhi, written just a year before his own death in January 1950, he was still confessing that Gandhi inspired in him “a sort of aesthetic distaste”—and yet, “compared with the other leading political figures of our time, how clean a smell he has managed to leave behind!”

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers