Oxford University Press's Blog, page 61

December 13, 2022

What’s next for China? Sustainability, technology, and the world’s future

The COVID-19 pandemic can safely be termed the signal event of the first two decades of the twenty-first century. And, like much else about this century, it is closely tied to China: the SARS-CoV-2 virus was first detected in the country, and it continues to wreak havoc on everyday life in the world’s second-largest economy, at considerable cost to global trade and growth.

The increasingly central role of public health and other emerging issues in China’s relationship with the world is the point of departure for my new book, China’s Next Act: How Sustainability and Technology are Reshaping China’s Rise and the World’s Future. Its central argument is that we must re-envision our thinking about China’s rise and its role in the world in terms of two newer issue areas: sustainability and emerging technology. This is both because China is increasingly indispensable to tackling shared global challenges like climate change, and because ecological and technological challenges are themselves increasingly shaping Beijing’s decision-making in areas like economic development and foreign policy.

My argument is based in large part on personal experience. Soon after finishing graduate school, I had the opportunity to complete a fellowship in the Office of Chinese and Mongolian Affairs at the U.S. Department of State, where I had a portfolio called “Environment, Science, Technology, and Health.†The focus was on climate change, but I also covered everything from nuclear waste to Ebola response to seismological monitoring. Despite the catch-all nature of these issues, two things tied them together: their increasing importance to the world, and the priority that Beijing attached to them.

“China is increasingly indispensable to tackling shared global challenges like climate change.”

I became convinced that in order to understand where China is headed and how it will affect the rest of the world in the twenty-first century, it would be essential to explore China’s response to tackling shared ecological challenges, especially climate change and public health, and to regulating emerging technologies, especially artificial intelligence and biotechnology.

In the decades ahead, both China and the world will increasingly be shaped largely by developments in sustainability and technology. The book lays out five ways in which sustainability and technology will reshape China’s rise and its role in the world, with major implications for foreign countries, businesses, universities, and other organizations:

China-linked political and economic risk will intensify. No-regrets supply chain diversification will only make more sense over time for foreign businesses.Environmental sustainability will become a bigger and bigger priority in the China market because of growing regulatory and consumer pressure. This is both in direct operations and larger supply chains.Data privacy, security, and surveillance will pose growing dilemmas for multi-national companies. Data governance is becoming more fragmented, and compliance and cross-border transfer more difficult. Firms need to prepare for “data de-globalization.â€China is becoming a more isolated, but still large and important, innovation ecosystem. How to access and leverage this ecosystem, and the talent within it, will become a bigger challenge for foreign companies, universities, and other organizations as China-global research collaborations, student flows, and other connective channels shrink.China’s frothy biotech sector is cooling but will still be a major growth driver in the decades ahead. And developments in biotech will disrupt and reshape many sectors and industries via biometrics, biomaterials, and other advancements.Three strategies for approaching ChinaIn the course of exploring these implications, I also suggest three strategies to help foreign governments, businesses, universities, and other organizations approach China in the decades ahead:

Ring fencingThis strategy involves identifying core areas of common interest and working to insulate them from tensions in other areas. This is likely to be most effective on highly specific, technical issues like nuclear security.

Coalition-buildingThis approach requires working with allies and partners to establish diverse networks in areas like technological standard-setting that can include and engage China—but prevent it from making the rules on its own terms.

Prioritizing non-state and sub-national partnershipsFor a variety of deep-seated reasons, inter-governmental relations between China and many other nations are likely to continue to worsen. Though no substitute for diplomatic action, the private sector, universities, and other non-governmental actors will have to shoulder much of the burden of working to address shared concerns in the areas of sustainability and technology.

To me, this observation leads to a final, and perhaps the most critical lesson of all from the book: despite the disruption of the past five years, engagement with China is more critical, as well as complex, than ever before.

Featured image by Nuno Alberto via Unsplash, public domain

The post What’s next for China? Sustainability, technology, and the world’s future appeared first on OUPblog.

What’s next for China? Sustainability, technology, and the world’s future

The COVID-19 pandemic can safely be termed the signal event of the first two decades of the twenty-first century. And, like much else about this century, it is closely tied to China: the SARS-CoV-2 virus was first detected in the country, and it continues to wreak havoc on everyday life in the world’s second-largest economy, at considerable cost to global trade and growth.

The increasingly central role of public health and other emerging issues in China’s relationship with the world is the point of departure for my new book, China’s Next Act: How Sustainability and Technology are Reshaping China’s Rise and the World’s Future. Its central argument is that we must re-envision our thinking about China’s rise and its role in the world in terms of two newer issue areas: sustainability and emerging technology. This is both because China is increasingly indispensable to tackling shared global challenges like climate change, and because ecological and technological challenges are themselves increasingly shaping Beijing’s decision-making in areas like economic development and foreign policy.

My argument is based in large part on personal experience. Soon after finishing graduate school, I had the opportunity to complete a fellowship in the Office of Chinese and Mongolian Affairs at the U.S. Department of State, where I had a portfolio called “Environment, Science, Technology, and Health.” The focus was on climate change, but I also covered everything from nuclear waste to Ebola response to seismological monitoring. Despite the catch-all nature of these issues, two things tied them together: their increasing importance to the world, and the priority that Beijing attached to them.

“China is increasingly indispensable to tackling shared global challenges like climate change.”

I became convinced that in order to understand where China is headed and how it will affect the rest of the world in the twenty-first century, it would be essential to explore China’s response to tackling shared ecological challenges, especially climate change and public health, and to regulating emerging technologies, especially artificial intelligence and biotechnology.

In the decades ahead, both China and the world will increasingly be shaped largely by developments in sustainability and technology. The book lays out five ways in which sustainability and technology will reshape China’s rise and its role in the world, with major implications for foreign countries, businesses, universities, and other organizations:

China-linked political and economic risk will intensify. No-regrets supply chain diversification will only make more sense over time for foreign businesses.Environmental sustainability will become a bigger and bigger priority in the China market because of growing regulatory and consumer pressure. This is both in direct operations and larger supply chains.Data privacy, security, and surveillance will pose growing dilemmas for multi-national companies. Data governance is becoming more fragmented, and compliance and cross-border transfer more difficult. Firms need to prepare for “data de-globalization.”China is becoming a more isolated, but still large and important, innovation ecosystem. How to access and leverage this ecosystem, and the talent within it, will become a bigger challenge for foreign companies, universities, and other organizations as China-global research collaborations, student flows, and other connective channels shrink.China’s frothy biotech sector is cooling but will still be a major growth driver in the decades ahead. And developments in biotech will disrupt and reshape many sectors and industries via biometrics, biomaterials, and other advancements.Three strategies for approaching ChinaIn the course of exploring these implications, I also suggest three strategies to help foreign governments, businesses, universities, and other organizations approach China in the decades ahead:

Ring fencingThis strategy involves identifying core areas of common interest and working to insulate them from tensions in other areas. This is likely to be most effective on highly specific, technical issues like nuclear security.

Coalition-buildingThis approach requires working with allies and partners to establish diverse networks in areas like technological standard-setting that can include and engage China—but prevent it from making the rules on its own terms.

Prioritizing non-state and sub-national partnershipsFor a variety of deep-seated reasons, inter-governmental relations between China and many other nations are likely to continue to worsen. Though no substitute for diplomatic action, the private sector, universities, and other non-governmental actors will have to shoulder much of the burden of working to address shared concerns in the areas of sustainability and technology.

To me, this observation leads to a final, and perhaps the most critical lesson of all from the book: despite the disruption of the past five years, engagement with China is more critical, as well as complex, than ever before.

Featured image by Nuno Alberto via Unsplash, public domain

December 12, 2022

The predictably grievous harms of Effective Altruism

Over the past decade the philanthropic ideology of Effective Altruism (EA) has grown massively both in attracting funds and in influencing young people to try to make as much money as they can and give most of it away. EA offers adherents a philosophy of charitable giving that promises to do the “most good” per dollar donated or time spent. Until recently, EA’s role in directing charitable funds had functioned stealthily, barely scrutinized by most media outlets. But a series of catastrophic financial hustles in the world of cryptocurrency has brought EA heightened attention and started to expose its dangers.

During the summer of 2022, journalists fawned over William MacAskill, one of the co-founders of EA and its offshoot “longtermism,” speaking admirably about the way he was able to cultivate sympathy for EA among tech and crypto billionaires such as Dustin Moskovitz, Sam Bankman-Fried, and Jaan Tallin. This led to securing hundreds of millions of dollars for effective altruist causes with pledges of billions more to come.

On 11 November 2022, Bankman-Fried, founder and CEO of crypto-currency exchange FTX, filed for bankruptcy, amid suspicions of fraudulent conduct reaching back several years. As Bankman-Fried’s business practices came under scrutiny, so too did his association with EA. A billionaire by age 30, he had become the poster boy for EA’s “earn to give” project. Bankman-Fried was raised a utilitarian and when he was a student at MIT, MacAskill persuaded him he could do the most good by making as much money as possible and then donating that money in an “effective” way.

Until the day before the bankruptcy filing, MacAskill had been an advisor to FTX’s charitable foundation, which had given tens of millions to EA and longtermist projects.

By mid-November, with the collapse of FTX and potential criminal charges pending, discussions of EA could be found at the top of blogs, newspapers, and podcasts in the United Kingdom, United States, and, indeed, around the world. In many of these discussions, the FTX-EA relationship was framed as a problematic alliance that provided moral cover for FTX’s conduct in exchange for hefty funding for EA. The standard line was that this will be a disaster for EA, in terms of reputation as well as funding.

The criticism that problems are inevitable when EA adherents follow the simplistic utilitarian idea that the ends justify the means, is correct as far as it goes. But the criticism says nothing about how EA is, at best, an utterly inadequate way of addressing global problems and, at worst, designed for the very sort of morally corrupt scandal in which it is now entangled. In the new collection, The Good It Promises, The Harm It Does, activists and scholars address the deeper problems that EA poses to social justice efforts. Even when EA is pursued with what appears to be integrity, it damages social movements by asserting that it has top-down answers to complex, local problems, and promises to fund grass-roots organizations only if they can prove that they are effective on EA’s terms.

Effective Altruists, like utilitarians, are committed to impartiality (each person’s good is as important as everyone else’s), welfarism (promoting well-being is the only good to be achieved), and maximization (to bring about not just good ends, but the most good, all things considered). To step inside the utilitarian frame is to accept that values that count as “good” can be abstractly quantified. Its methods leave it incapable of addressing historically sedimented structural injustices and intergenerational injuries, since these aren’t the sorts of things that can be quantified by EA-style metrics.

“EA is doing harm, in an increasingly global manner, to the work of activists for liberating causes.”

Despite the liberating intentions of many of its advocates, EA is, irredeemably conservative. It favors welfare-oriented interventions that increase countable measures of well-being and both neglects and diverts funds from social movements that address injustices and agitate for social change, particularly in marginalized communities both in the US and in the Global South.

To grasp how disastrously an apparently altruistic movement has run off course, consider that the value of organizations that provide healthy vegan food within their underserved communities are ignored as an area of funding because EA metrics can’t measure their “effectiveness.” Or how covering the costs of caring for survivors of industrial animal farming in sanctuaries is seen as a bad use of funds. Or how funding an “effective” organization’s expansion into another country encourages colonialist interventions that impose elite institutional structures and sideline community groups whose local histories and situated knowledges are invaluable guides to meaningful action.

Is it just that EA needs to avoid aligning itself with tech-bros and financial whiz-kids who may be playing fast and loose with other people’s savings, as the media narrative seems to suggest? No! EA is morally and politically wrongheaded, pernicious in its basic precepts, covering up systemic injustices embedded in the fabric of existing capitalist societies in a manner that clears the way for the perpetuation of significant wrongs. It is doing harm, in an increasingly global manner, to the work of activists for liberating causes. This point, which is barely present in the larger conversation that the implosion of FTX has triggered, is the core theme of The Good it Promises, The Harm It Does, a timely collection that deepens the criticisms of Effective Altruism beyond their sketchy financial associations.

Funny how it ain’t so funny: casting, Funny Girl, and Broadway’s body issues

Sometimes the meeting of an actor and a role produces a rare kind of alchemy that forever bonds the two… and sometimes the opposite happens. The former occurred when twenty-one-year-old Barbra Streisand was cast as famed comedienne Fanny Brice in the 1964 musical Funny Girl. The latter happened when Beanie Feldstein was cast as Brice in the 2022 Broadway revival of Funny Girl, which rather auspiciously opened on Streisand’s 80th birthday. Critics in 1964—and in 2022—hailed Streisand as Brice; her performance was the stuff of legend in a way that few match. The headline of the Los Angeles Times review announced, “‘Funny Girl’ still belongs to Barbra Streisand.” These kinds of reviews that openly compare the original star to the star of a revival are their own sub-genre of theatrical criticism and typically occur when, like Streisand-as-Brice, the performer and role are indelibly associated like Jennifer Holliday as Effie White in Dreamgirls (1981) or Ethel Merman in Gypsy (1959). Feldstein was inevitably and unfavorably compared to the legend, which was both impossible to live up to and to avoid.

Initially, Feldstein’s casting was hailed by advocates and the media as a win for authentic, inclusive, and body-positive casting—she is Jewish and is fuller-figured than most women cast as romantic leads on Broadway—upon its announcement in August 2021. But from the start the press around Feldstein’s casting also raised the specter of another actor long rumored to covet the role: Lea Michele. The New York Times reported that Michele herself tweeted congratulation to Feldstein, writing “YOU are the greatest star!!” The same article contained a history of the troubled road traveled to revive Funny Girl on Broadway at all given the show’s structural problems and the long shadow of Streisand.

Feldstein’s reception in the role was ultimately mixed. It’s almost never a good sign when reviews of a revival open with paragraphs about the original star, or, as Adrian Horton’s review in The Guardian does, opens with this humdinger: “It must be difficult to cast Funny Girl.” Most critics found Feldstein’s acting winning and her singing wanting. What was a notable shift in criticism, given her historic casting and the pervasiveness of body shaming in the industry, was that critics faulted the size of her voice and not the size of her body in regards to her shortcomings in the role. Funny Girl is itself open about the appearance-based discrimination that runs rampant in entertainment, which remains as true of Brice’s time as it was in the 1960s when Streisand became a star as it is in 2022. One of the show’s first songs is titled “If a Girl Isn’t Pretty,” and it lists a litany of reasons a girl whose looks aren’t considered up to snuff should “forget the stage and try another route.”

Critics overall received the revival as a let-down and it only scored one all-important Tony Award nomination despite brisk box office business. Feldstein announced that she would be departing the production earlier than expected and that’s where the offstage drama reached a fever pitch as rumors about who would replace her became fodder for internet gossip. This was nothing new for Funny Girl, though.

And here’s where Broadway’s history repeats itself—with an ironic twist. Actor-singer Lainie Kazan made waves as understudy to Streisand in the original Broadway run of Funny Girl when she played a two-show day due to Streisand’s absence. The Times reported that “after her day in the spotlight . . . Ms. Kazan quit the show. Such was the publicity attending the musical that newspaper articles appeared when Ms. Streisand was thought to be ill and Ms. Kazan did not go on.” Kazan’s career seemed to be gaining momentum when she was cast in the Broadway-bound musical Seesaw in 1972.

As I detail in Chapter 3 of Broadway Bodies, Kazan was fired from the show before it came to New York because “the consensus of opinion was that she didn’t look like a dancer or move like a dancer. She was also some 40 pounds overweight.” Kazan, a big, brassy belter, was replaced by her friend, the thinner, somewhat smaller-voice Michele Lee. This offstage conflict foreshadowed the onstage conflict of a later size-inclusive musical, Dreamgirls (1981), which shared a director in Michael Bennett.

Feldstein’s casting as a plus-sized romantic interest in a musical comedy was so rare that there are very few antecedents: Jennifer Holliday in Dreamgirls, Marissa Jaret Winokur in Hairspray (2002), and Bonnie Milligan in Head Over Heels (2018). The odd and certainly coincidental irony that Feldstein was replaced by Lea Michele while Kazan was booted for Michele Lee shows how body shaming has and hasn’t changed in the intervening five decades. Michele and Lee both won raves, while Kazan and Feldstein started over. To add insult to injury, Michele—and not Feldstein—even got to record the revival’s cast album, cementing her place in the show’s history.

The history of appearance-based disqualification is not just history: it is ongoing. While it was a different and exciting choice for producers to cast Feldstein, casting Michele was a sharp correction to what Broadway musicals position as the norm: small body, big voice.

Featured image: Barbra Streisand in her Oscar-winning role in “Funny Girl” (1968), via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

December 9, 2022

Leonardo and the Salvator Mundi: fame and infamy

Typing a search term into Google prompts a useful feature called “People also ask.” It’s a query expansion tool, designed to optimize high-traffic keyword searches. When people ask me about the Salvator Mundi, just like Google, I can predict the questions they will “also ask.” Top of the list: do I think the painting is a “real” Leonardo? My go-to answer paraphrases (the then) Prince Charles’s infamous equivocation about the nature of romantic love. “It’s a real Leonardo,” I say, “whatever that means.” This may sound wantonly facetious, but it’s not. What I mean is that the painting broadly corresponds, in materials, technique, and approach, to the small group of paintings accepted to be by Leonardo da Vinci; that is, the established canon of his works.

Joseph Théodore Richomme after Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Death of Leonardo da Vinci, expiring in the arms of King François I, c. 1825, etching and engraving. Is the Salvator Mundi a “real” Leonardo da Vinci?

Joseph Théodore Richomme after Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Death of Leonardo da Vinci, expiring in the arms of King François I, c. 1825, etching and engraving. Is the Salvator Mundi a “real” Leonardo da Vinci?The attribution of the Salvator Mundi to Leonardo is uncontroversial among most of the key specialists. We can plot their views on a sliding scale ranging from “execution by the sole hand of Leonardo” at one pole, to “execution by Leonardo with varying degrees of input from a studio assistant” at the other. Art historians tend to allow a degree of elasticity about such categories, in recognition of the abundant evidence of collaborative practices in the Renaissance workshop. The “market,” on the other hand, inculcates more rigid classifications. The standard glossaries and legal disclaimers of major auction houses impose a strict hierarchy organized according to proximity to a given artist’s hand. The internal categories are sharply delineated, and, accordingly, are confirmed in differentials of monetary values. A work described as by “Significant Italian Renaissance Artist” will usually achieve a higher hammer price, sometimes in the order of millions, than an otherwise equivalent work described as by “Significant Italian Renaissance Artist and Workshop.”

The intense public interest in the Salvator Mundi, and whether or not the painting should be attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, is a product not only of its re-emergence during the internet age, but also its achievement of the world record price for a work of art at public auction ($450,000,000, 15 November 2017, Christie’s, New York). A moment of spectacular congress between the Academy and the Market, the sale led many to question the process by which the canon of Leonardo is established and policed. While any new attribution to Leonardo has, since at least the nineteenth century, instigated public debate, modern media conditions—the live broadcast of the auction, the near-universal access to the internet, the algorithms designed to polarise opinion online—serve to promote and amplify controversy.

Still, the question of what exactly comprises “a Leonardo” is fascinating and imperative. It relies on the construction of his artistic persona over the course of five hundred years, in a variety of locations, and against the backdrop of gradually widening access to, and understanding of, his writings.

Why is Leonardo da Vinci the world’s most famous artist?That leads to the second question “people also ask” me: Why is Leonardo the world’s most famous artist? In one sense, it’s because he got a head start in the fame game, by writing himself into the narrative. The years he spent at the court of Ludovico Sforza in Milan (c.1483-90) were undoubtedly instrumental to Leonardo’s budding reputation. It is there that we see him jostling for place among a gaggle of official sonneteers. Embedded in the cut-and-thrust, he is an actor in the performance of paragone. He inhabits the poetry of his literary rivals and collaborators; their paeans to his portraits are littered with Neoplatonic tropes and Petrarchan allusions. Bernardo Bellincioni extols the portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (Lady with an Ermine): “the supreme talent and hand of Leonardo” rivals Nature. Gasparo Visconti remarks waspishly that in painting others, Leonardo always portrays himself. Moreover, he is easily distracted, “his brain goes wandering each time the moon wanes.” By the turn of the sixteenth century we find Leonardo not only acclaimed the “New Apelles,” but, like the famous ancient Greek painter’s rival, Protogenes, we hear that he “spends many years to complete [a panel].” We can, perhaps, detect Leonardo’s agency in these poem-portraits. They iterated the Plinian model of fame, promoted comparisons between himself and his classical forebears, and raised his profile among the select circles of the Milanese court.

Nor is the eulogizing of Leonardo in early print media unconnected to the promotion of Florentine—and Medici—interests. It is no coincidence that his chief advocates were fellow denizens of the Tuscan city. Ugolino Verino, who tutored Giovanni de’ Medici (later Pope Leo X), praised Leonardo in An Illustration of the City of Florence (1503); he was “possibly” pre-eminent among a number of prominent artists. It was Giorgio Vasari who, in his seminal biography of 1550, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, formulated the canonical Leonardo, and provided the definitive early statement of his celebrity: “the fame of his name so spread abroad that, not only was he valued in his own day, but his renown has greatly increased since his death.” Yet, while Vasari reserved his greatest praise for the “divine” Michelangelo, it is Leonardo who holds sway in the public’s mind as the most famous artist of all time. Why should this be?

“The key to Leonardo’s singular celebrity is, I think, his adaptability; he is re-invented by each era according to its particular concerns. There are many Leonardos.”

The key to Leonardo’s singular celebrity is, I think, his adaptability; he is re-invented by each era according to its particular concerns. There are many Leonardos. There is the Leonardo of Leonardo himself, the Leonardo of Bellincioni and the poets, of Vasari, Lomazzo, Richter, Pater, Freud, Clark, Gombrich, Kemp, Google. So, we have Leonardo the useful, the engineer with a side hustle as painter and sculptor. We have Leonardo the resourceful autodidact, keeping up with the humanists at the ducal, papal, and royal courts. We have Leonardo the flawed genius, incapable of finishing a task. We have Leonardo the ideal artist-scientist of the Enlightenment. We have Leonardo the universal man of modernity. We have Leonardo the queer technological visionary of post-modernity.

This phenomenon derives from Vasari’s sketch of the light and shade of Leonardo, his ingenuity, but also his “faults” (he’s easily distracted, never finishes a task). A sixteenth-century audience would have appreciated the allusions to celebrated ancient painters; later generations found the discussion of character and psychology appealing. Flaws and failings humanize Leonardo, they make him “relatable” to modern audiences.

As Martin Kemp notes in a foreword to an edition of Leonardo’s treatise on painting, The Fabrication of Leonardo da Vinci’s Trattato della pittura, (Leiden: Brill, 2018, 2 vols; vol. 1, xi.), “Inevitably we tend to project the Leonardo we know today into past eras. […] Until the late nineteenth century, ‘our’ Leonardo was not known.” The gaps and mysteries in our knowledge only serve to promote the continual reformulation of Leonardo. Paul Valéry, in his seminal 1895 essay on Leonardo, confessed that, knowing very little about him, he had invented a Leonardo of his own. Perhaps that is what everyone does.

We can credit the received canon of Leonardo’s paintings in large part to Vasari. His Life mentions 11 works (one a collaboration with Verrocchio) that are tentatively identifiable with extant paintings and drawings by Leonardo/his workshop. Of these, six can be confirmed with some conviction. This small catalogue defines what we have come to think of as “a Leonardo.” Most of all, we measure by the yardstick that is the Mona Lisa.

Why is there no account of the Salvator Mundi in early sources?Vasari does not mention a painting corresponding to a Salvator Mundi. This brings us to the other question “people also ask”: Why is there no account of this now-famous painting in the early sources on Leonardo? Does this mean he did not paint it?

The painting has become a celebrity in its own right, but it was obscure before 2011. To borrow a famous phrase, it was a “known unknown,” a “hypothetical Leonardo.” There is no mention of such a work in the early biographical sources; no eyewitness account. The first published association of the name of Leonardo da Vinci and an image of a mature, frontal Christ dates from the middle of the seventeenth century, when it was inscribed in the legend of Wenceslaus Hollar’s etching: “Leonardo da Vinci pinxit, Wenceslaus Hollar fecit Acqua forti, secundum Originale. AO 1650.”

The current fame of the Salvator is bound up with the fame of Leonardo, and indivisible from the $450,000,000 price tag. It is, therefore, a significant object in the public’s imagination. There is a natural expectation of some early record of its creation or ownership. Surely it was famous in its own day? What are we to make of the lack of documentation of the Salvator?

First, we should remind ourselves that the Last Supper is the only painting by Leonardo that has a continuous history, for reasons that are self-explanatory. Second, that plotting the movements of a small object made of wood and paint over the course of half a millennium is inescapably problematic. Third, that a canon is a construct, not a fact.

Leonardo’s canon is a citadel against which any new attribution must be attempted. Martin Kemp’s coining of the Salvator Mundi “the male Mona Lisa” deftly posited the painting in direct relation to Leonardo’s most canonical work. In doing so, he unwittingly provoked the resonant by-line annexed by Christie’s to market the painting in 2017.

Speaking to USA Today ahead of the auction, Francois de Poortere enthused, “This is the holy grail of Old Master paintings, some people call it the male Mona Lisa. People are deeply taken by this work. You could buy it and just build an entire museum around it.” His words seem to have exerted a powerful influence on the winning bidder, Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, to judge by his apparent, and ultimately frustrated, desire to have the two paintings hang side-by-side in the Louvre, and his reported plan to exhibit the Salvator in a dedicated museum in Saudi Arabia.

Discover more about Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi in this three-part blog series.

Featured image: The Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi LLC (used with permission)

December 8, 2022

The history of Ancient Rome: a timeline

From Octavian’s victory at Actium to its traditional endpoint in the West, the Roman Empire lasted a solid 500 years—one-fifth of all recorded history. The story of Rome—and the strategic planning that grounded that history—is longer and more complex than many historians haven grappled with, until now.

By employing an expansive definition of strategy and by focusing much of the narrative on crucial historical moments and the personalities involved, James Lacey provides a comprehensive, persuasive, and engaging account of the rise and fall of the Roman Empire.

Explore the key moments that shaped the empire in the timeline below:

December 7, 2022

Dude: a long history of a short word

This is an informal report of Origin of the Term ‘Dude’, a book by Gerald Leonard Cohen, Barry A. Popik, and Peter J. Reitan, self-published by Professor Gerald Cohen, at Missouri University of Science and Technology. The appearance of the book was not a surprise to me, because notes on this subject have been appearing in the monthly journal Comments on Etymology, edited and published by Cohen, for nearly fifty years. Cohen is the only professional linguist on the team, which shows how very much dedicated outsiders can contribute to the research in the history of some of our most enigmatic late words. Comments on Etymology has existed since 1971. Gradually, Cohen’s interest in word origins shifted to the history of slang, and his contributions to this area are well-known. Dude is of course also slang, though nowadays perfectly inoffensive.

Most of our readers probably know that when work on The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) started, thousands of people began to collect slips illustrating the use of each word in manuscripts and books. The citations we find in the published entries are a tiny part of what the team at Oxford has amassed. James A. H. Murray, the first editor of the OED, was interested in both words’ history and their etymology. Some such etymologies are fairly transparent, but those are an exception, rather than the rule. For instance, more than a hundred people have written about the etymology of god, but we still do not know what exactly god meant to its creators. Though this is an extreme example, some controversial words have attracted the attention of numerous philologists and amateurs. Locating and evaluating every contribution is a hard task. A few hypotheses can be discarded sight unseen, some others are worthy of attention, and still others are inspirational. Once the scholars have dug their way through this dustheap, they may look at their trophy with satisfaction, doubt, or despair. In the last case scenario, our dictionaries write “of unknown origin.” A book can be written about studying each of those intractable words.

Such books exist. Cohen himself has written two monographs about the word shyster, another monograph, titled Origin of the Word ‘Jazz’, contributed to the success of Origin of the Term ‘hot dog’ by him, David Shulman, and Barry A. Popik and the book Origin of Kibosh (by Stephen Goranson, Gerald Cohen, and Matthew Little). Now it is dude that has been documented with amazing accuracy. The new book is full of quotations from newpapers and magazines, pictures culled from the same sources, and reports of the word’s origin from multifarious sources. Among other things, we are exposed to the history of the dudification of young “swells” and “mashers” in New York and Washington D.C. about a hundred and forty years ago.

Oscar Wilde, the most famous dude ever.

Oscar Wilde, the most famous dude ever.(Library of Congress, public domain)

Origin of the Word ‘Dude’ opens with the following dedication: “To the memory of Robert Sale Hill (1850-1922), whose January 14, 1883, poem ‘The Dude’ [in the New York City newspaper The World] introduced a word which instantly became one of the most popular items in the English slang lexicon.” Three earlier examples of dude are believed to exist, but the authors question the dating of those sources and insist that dude was Hill’s coinage. The value of the book does not depend on this reference: it is the incomparable richness of the material they have amassed that will remain as a permanent monument to their labor of love. After all, every word in every language was invented by someone.

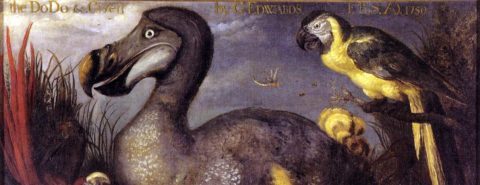

Naturally, Cohen and his companions had to decide how Hill came up with that immortal monosyllable. But let me first quote the relevant lines: “Long years ago, in ages crude, / Before there was a mode, oh! / There lived a bird, they called a ‘Dude’, /Resembling much the ‘Dodo’.” A long description of the new tribe follows. Incidentally, Oscar Wilde, who visited the United States in 1882-83, was looked upon as the quintessential dude and perhaps even reinforced the fashion, with regard to its dress code and affectations. One of the most curious stanzas sounds so: “Imported ‘dudes’ are very shy/ Now ‘Oscar’s’ crossed the ocean, / But native ‘Dudes’ soon learn to fly/ And seem to like the notion.” The book presents a picture of a long search for finding the sources. We do not only get the answer to the riddle but follow the way toward the solution. On page two, we read: “Although the word’s entire history is no doubt interesting, the focus of the present book is on the part the three co-authors have been researching.”

Robert Sale Hill.

Robert Sale Hill.(From Serious thoughts and idle moments by Robert Sale Hill via HathiTrust, public domain)

There can be little doubt that Robert S. Hill’s poem propelled the word dude into fame, but where did he get it? The book suggests two sources: the phrase Yankee Doodle (which, it has turned out, could also be used as a term to ridicule a dandy) and the British slang word fopdoodle “a silly-looking fop,” which Hill might know. Presumably, the word’s “offspring” doodle was later shortened to dude. Be that as it may, the crucial point is that Hill wrote a poem about dudes and launched the slang word into prominence. “The dudes of that era were young, vacuous, brainless, wealthy Anglomaniacs who drew widespread amusement and ridicule for their slavish imitation of British dress and speech” (page one). The authors state that the dude craze began immediately. (I can testify to the existence of similar phenomena from my experience. In the 1960s, though I am no longer quite sure of the chronology, young men in the Soviet Union began to wear very narrow trousers. The country’s rulers had no more important task than to eradicate this pestiferous western fashion. The men guilty of following that fashion were called stiliaga—stress on the syllable –liá, from stil’ “style” and a denigrating agent-forming suffix.) Hill died a century ago, and there is no one to ask whether the proposed etymology is correct, but the entire concatenation of events is typical: a word is coined, the community accepts it with rare enthusiasm, and the author is forgotten. Barry A. Popik excavated this poem, and this was a discovery of prime importance.

The book reads like a thriller. To enjoy it, one does not have to be an etymologist. Here I’ll confine myself to a few remarks. Monosyllabic words beginning and ending with the same consonant are very often expressive. Compare bib and its dialectal double beb “to drink, tipple”, bob (any meaning), dud “worthless object,” gig, kick, pap, pup, poop, boob, and their likes. Such words “pop up,” disappear, and surface again and again. German dialectal Dude also means “fool.” In American English, horse dung was called dude. Though being in big doo-doo surfaced in print only in the twentieth century, the childish word doo-doo is probably very much older. Robert S. Hill may have drawn on several sources and associations, while coining dude. After all, to abstract dude from flapdoodle and Yankee Doodle, he would have had to get rid of the syllable –le and come up with a new item of the vocabulary.

The dudiest dude.

The dudiest dude.(By Seth Doyle on Unsplash, public domain)

Such musings in no way detract from the achievement of the three authors. They have collected a ton of precious data and traced the history of dude in an exemplary way. The unearthing of Hill’s poem was indeed a major event. Etymology is not only about the act of creation. It has an important social dimension. We want to know how this or that word spread, in what strata of society it gained popularity, and what factors guaranteed its longevity. The Origin of the Word ‘Dude’ answers those questions in an exemplary way and goes a long way toward making etymology a pursuit interesting to the wide world.

Featured image by Roelant Savary, Natural History Museum London, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

December 5, 2022

Weird Moby-Dick

What does a “heart-stricken moose” sound like when it “sob[s]”? Why would someone yearn to “fist a bit of old-fashioned beef in the fore-castle”? What manner of destitute is a “butterless man”? Can I, too, get away with coining adverbs like “suckingly” and “uninterpenetratingly”? What is “the universal thump,” and why would I want to thump others–and be thumped in turn?

There are a lot of peculiar phrases in Moby-Dick. My new introduction to the second Oxford World’s Classics edition of Herman Melville’s novel highlights the startling weirdness of the book, both in its literary form and its language. Weirdness extends beyond strangeness: weirdness also invokes enchantment, fate, curiosity, and the supernatural. In other words, when I say that Moby-Dick is weird I mean that in the best imaginable way. The novel’s weirdness does not subvert its monumentalism (nor its monumental reputation!) but serves as a sly sidelight on Moby-Dick’s ambitious attempts to create meaning.

Take, for instance, the famous scene in “The Quarter-Deck” in which Ahab reveals to the crew that the true (but heretofore hidden) aim of their voyage is not a general commercial whale hunt but chasing and killing the notorious white whale known as Moby Dick, who had “dismasted” Ahab of his leg. It’s a powerful, profound scene about whether the force that controls the world—whether natural or supernatural—is a force for good, evil, or indifference.

“Weirdness extends beyond strangeness: weirdness also invokes enchantment, fate, curiosity, and the supernatural.”

But amid the powerful profundity, Ahab overwhelms the objections of his first mate not just with his rhetorical intensity, but by weirdly infecting him with something “shot from [his] dilated nostrils”; Starbuck “inhale[s] it in his lungs.” This coarsely vivid image is matched in weirdness only by Melville’s description of the sound of grief made by Ahab when speaking of his missing limb and his need for revenge in the same scene. Ahab heaves “a terrific, loud, animal sob, like that of a heart-stricken moose.” What does a “heart-stricken moose” sound like? Moby-Dick does not presume that a reader might reject the outsized improbability of this image, or dispute how that poor, sad moose might have had its heart broken. The novel instead asks us to take far-flung, incommensurate elements—a moose having a cardiac event, not to speak of a white whale bearing “inscrutable malice”—and bring them near to our understanding.

In what follows I share some more of the most delightfully weird phrases or descriptors in the novel, in rough categories. First is the playfully, animalistically weird:

“It tasted something as I should conceive a royal cutlet from the thigh of Louis le Gros [Louis VI] might have tasted, supposing him to have been killed the first day after the venison season” “anonymous babies”“a sort of badger-haired old merman”“an eruption of bears”“immaculate manliness”“the coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs”“how I wish I could fist a bit of old-fashioned beef in the forecastle”“that unaccountable cone” [the whale’s penis]Next, we have some characterological hot takes. Of the Pequod’s sailors, Melville writes:

Ahab “lived in the world, as the last of the Grisly Bears lived in settled Missouri”Starbuck’s “pure tight skin was an excellent fit” Stubb has “whale balls for breakfast” Flask is a “butterless man” Queequeg is “George Washington, cannibalistically developed”Ishmael has the “privilege of discoursing upon…the tallow-vats, dairy-rooms, butteries, and cheeseries in [the whale’s] bowels”We turn now to rhetorical devices. Melville loves litotes, or figures of speech in which a positive meaning is suggested by means of double negatives. You might say that a fair observation is “not wrong,” in an example of how litotes convey understatement. But litotes keep visible the dark side of an affirmational phrase: when I explain litotes to my students, we all agree that we would rather be thought “attractive” than be described by the litotes “not unattractive.” Moby-Dick (and indeed all of Melville’s writing) is a riot of litotes, weird ones. For example:

“his swart visage and bold swagger are not unshunned in cities”“that not unvexed subject, the skin of the whale”“an old, crutch-like, antediluvian, wheezing humorousness, not unstreaked now and then with a certain grizzled wittiness”“thy strange mummeries not unmeaningly blended with the black tragedy of the melancholy ship”My final category of weirdness is Moby-Dick’s baroque adverbs. Among other indulgences, Melville promiscuously makes and unmakes adjectives, adverbs, and nouns. His extravagance of language was noted by his contemporary reviewers as well as by today’s readers. (One review of his novel Pierre even printed a long list of “Mr. Melville’s word-combinations” that gave particular offense to the reviewer. These include “flushfulness,” “patriarchalness,” “intermarryingly,” “unemigrating,” and “uncapitulatable.” [American Whig Review, 1852]) These are my favorite adverbial word-combinations in Moby-Dick:

wastingly suckingly rivallingly inspectingly stoopingly hummingly uninterpenetratingly unmurmuringly foamingly sidlingly bamboozlingly unrustlinglyAll of these adverbs are flagged by Microsoft Word’s spell check function as ungrammatical, but all make sense to me—in fact, all produce a gloriously weird excess of sense. Such words can present a challenge or a puzzle to a reader, but they also bear voluptuous linguistic and significatory pleasure. Melville was aware that such pleasures might be fugitive, though. As he was completing Moby-Dick, he wrote to Nathaniel Hawthorne “What I feel most moved to write, that is banned, — it will not pay. Yet, altogether, write the other way I cannot. So the product is a final hash, and all my books are botches.” In words like “sidlingly” and “uninterpenetratingly” we see a glimpse of what it means to “write the other way.”

I close by passing along “the universal thump.” When Ishmael goes to sea, he tells us in the novel’s first chapter, he goes as a “simple sailor,” neither passenger nor officer. This will mean that he is ordered about or disciplined on ship. But as he explains:

“However the old sea-captains may order me about–however they may thump and punch me about, I have the satisfaction of knowing that it is all right; that everybody else is one way or other served in much the same way–either in a physical or metaphysical point of view, that is; and so the universal thump is passed round, and all hands should rub each other’s shoulder-blades, and be content.”

Ishmael turns the thump of the disciplinary blow into the soothing shoulder-rub of collective content. “The universal thump” may be a weird thing to seek out, but Melville assures us that “it is all right.”

Featured image by Stichting Rijksmuseum het Zuiderzeemuseum. 022296 via Wikimedia Commons. (Public Domain)

December 3, 2022

Becoming Emeritus

At the end of the month, I’ll retire from my teaching job. My university will add me to its list of emeritus faculty, with all the special privileges that new rank entails. Emeritus faculty retain an email account, enabling me to keep up with campus news, scintillating all-faculty debates, and student requests for recommendations. Emeritus faculty also get complimentary parking and library privileges. And emeritus faculty have the opportunity to continue to work on campus committees (I’ll pass on that one).

The emeritus title is not only used by academic institutions: you can find it in business (president emeritus, chairperson emeritus, CEO-emeritus, director emeritus), the clergy (pastor emeritus, rabbi emeritus, bishop emeritus, and now even pope emeritus), and elsewhere (archivist emeritus, judge emeritus, librarian emeritus). The usual style is for the adjective emeritus to follow the noun when it is used with a name. Emeritus works like alumnus, with the plural form emeriti and feminine forms emerita (singular) and emeritae (plural). Emeritus and emeriti are often used in a gender-neutral way but usage and personal preferences vary, so it’s wise to check your institution’s style guide or consult the emeritus individual themself.

When I received the letter from the Provost granting me emeritus status, I naturally got curious about the etymology. I knew what a demerit was and a had a vague recollection of scouting merit badges. There is also the increasingly contentious notion of meritocracy, and the totally unrelated word meretricious, a flashy way of saying “flashy” or “tawdry.”

I asked a colleague if she thought emeritus meant having extra merit. She looked at me appraisingly, shook her head, and said “No, clearly not.”

Perhaps the first letter of emeritus, the e-, was related to ex- and indicated someone formerly having merit, but now a superannuated has-been. Would I be an ex-professor? Would people be coming up to me and asking “Didn’t you used to be …?”

Finally, I went to the Oxford English Dictionary to sort all this out. It turns out that the e– in emeritus is a variant of Latin ex, but not in the sense of former like ex-president or ex-husband or ex-con. It is the ex of ex officio, ex cathedra, ex nihilo or ex libris, meaning “from” or “out of.” So, emeritus is a past participle (like retired) meaning literally “from service” or “having done sufficient service” (the OED even suggests the gloss, “having served out one’s time,” though I don’t like the connotation).

There is even a related rare and obsolete verb that the OED cites, to emerit, meaning “To obtain by service, deserve.” Just one example is given, from 1648: “The persons that … shall have emerited their pardons.”

Emerit is making something of a comeback, though as a noun: in 2022, the University of Wisconsin at Madison Faculty Senate adopted it as the gender-neutral form, as did the University of Oregon. And Oregon State University now allows faculty members to choose among emeritus, emerita, or emerit.

As for emeritus, it made its way into English in the seventeenth century, where it was used for clergy and professors. The earliest example I could spot in a newspaper data base was this, from The Caledonian Mercury in Edinburgh, Scotland in February of 1736:

Mr. Andrew Ross, of the University of Glasgow, Humanity-Professor Emeritus, being at present here, and invited by the Gentlemen of the College of Justice and Others, to give a presentation or two upon such parts of the Roman authors on which he has anything new to say;

The last few words made me smile. I, for one, am planning to have plenty of new things to say.

Featured image: “Churchill Hall, Southern Oregon U” by Finetooth. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

December 2, 2022

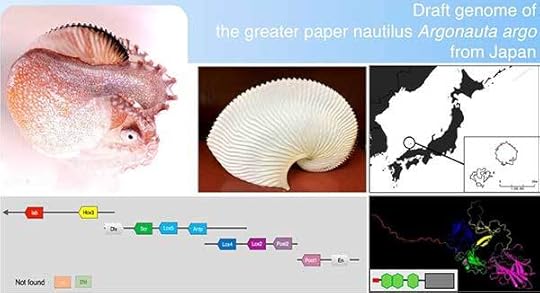

Inside the genome of the world’s weirdest octopus

The greater argonaut, Argonauta argo, has a reputation for being the world’s weirdest octopus and indeed may be one of the most unusual and mysterious creatures to roam the ocean. Unlike its relatives that live on the seafloor, this octopus has a pelagic lifestyle, meaning that it lives in the open ocean. This transition led to a host of evolutionary adaptations that make the argonaut unique among its octopod relatives.

The most obvious of these is the presence of a paper-thin, spiral-shaped structure secreted by argonaut females that is similar in appearance to the spiral shell of the nautilus (see image below). This shell-like “eggcase” protects the eggs laid inside and takes in air to maintain buoyancy in the water column; it has also given rise to a common misnomer for the argonaut: the paper nautilus. Weirder still, in order to mate, an argonaut male detaches his reproductive arm, known as the hectocotylus, and gives it to the female, who keeps it inside her shell and uses it to fertilize her eggs.

While scientists have long been interested in learning more about these unusual invertebrates, there have been relatively few studies on argonauts due to the difficulty in maintaining them in aquaria and obtaining wild-caught samples. Now, in a new study in Genome Biology and Evolution , researchers from six Japanese institutions present the first draft genome of A. argo, providing new insight into the evolution of its unusual characteristics while deepening our understanding of cephalopods (octopuses, cuttlefish, squid, and nautiluses) and mollusks.

The draft genome of the greater argonaut or paper nautilus, Argonauta argo, revealed several surprises. Shown are photographs (clockwise from top left) of A. argo and its paper-thin eggcase; a map of the location off Oki Island, Japan, where the sequenced specimen was caught; the nearly intact Hox gene cluster, which was previously thought to be fragmented in all octopuses; and a depiction of the A. argo LamininG3 protein, which is homologous to a protein in the nautilus shell but does not appear to be present in the eggcase of A. argo.

The draft genome of the greater argonaut or paper nautilus, Argonauta argo, revealed several surprises. Shown are photographs (clockwise from top left) of A. argo and its paper-thin eggcase; a map of the location off Oki Island, Japan, where the sequenced specimen was caught; the nearly intact Hox gene cluster, which was previously thought to be fragmented in all octopuses; and a depiction of the A. argo LamininG3 protein, which is homologous to a protein in the nautilus shell but does not appear to be present in the eggcase of A. argo.(CC-BY: https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evac156)

Led by corresponding authors Masa-aki Yoshida from Shimane University and Davin Setiamarga from National Institute of Technology, Wakayama College, the researchers set out to better understand the evolution of the argonaut, particularly the provenance of its shell-like eggcase.

The argonaut eggcase differs from the shell of the nautilus in its structure, composition, and method of formation. For example, rather than being secreted from the mantle (body) like the nautilus’s shell, eggcase proteins are secreted from two of the argonaut’s arms. Due to these differences, researchers had long suspected that the argonaut eggcase had evolved independently from the shell of the nautilus. According to Setiamarga, “it was not yet known how such a complex morphological trait was reacquired during evolution, particularly at the molecular level.” Luckily, the team was well-positioned to conduct a genomic study on argonauts. “Argonaut samples can be collected as bycatch from fishing nets on the shores of Oki Island in Shimane Prefecture, Japan, where one of the major authors (Yoshida) is located. Having access to fresh argonaut samples has made it possible for us to study this unusual organism.”

Analysis of the new draft genome of A. argo produced a number of surprising results. First, the A. argo genome was less than half the size of other cephalopod genomes, making it the smallest cephalopod genome known to date. Other cephalopods that have been sequenced so far exhibit relatively large genomes containing a high proportion of repetitive elements (~45% in Octopus bimaculoides). As also noted by Yoshida, “Our discovery of a species with a smaller genome size in the octopus lineage indicates that this trend [of genome expansion] is not essential for cephalopod evolution.” The authors found additional differences between the A. argo and O. bimaculoides genomes in their arrangements of Hox genes—genes critical in development whose sequence and order tend to be highly conserved—further suggesting that there is greater variation in genomic architecture among octopods than previously believed.

The authors also found highly conserved gene clusters of reflectins and tyrosinases, two gene families that they argue are associated with the argonaut’s transition to a pelagic lifestyle. Living in the open ocean, the argonaut relies heavily on its camouflage abilities to avoid predators. In particular, one of the argonaut’s arms usually wraps around its shell and reflects light using iridescent chromatophores, causing it to look like a mirror; the reflectin gene cluster likely plays a key role in this process. The tyrosinases identified by the authors are related to proteins that can be found in the shell matrix of some mollusks. Although it remains to be confirmed that these genes are involved in eggcase formation in the argonauts, the authors hypothesize that these genes were conserved in the argonaut’s non-shell-producing octopod ancestor and then repurposed for the argonaut’s shell-like eggcase.

The study’s authors also compared the evolutionary history of genes encoding eggcase matrix proteins in A. argo and those encoding shell matrix proteins in the nautilus and other mollusks. In general, eggcase matrix proteins were homologous (descended from a common ancestor) to genes present in other cephalopods and mollusks, though they were not used in shell formation in these species. Similarly, homologs of shell matrix proteins were present in A. argo, although they were not involved in eggcase production. These results “support the previously suggested hypothesis that the argonaut octopods recruited proteins unrelated to shell formation and used them for their eggcase,” according to Kazuki Hirota, a graduate student at The University of Tokyo who was also involved in the study.

The authors anticipate that their study will pave the way for future studies in several previously unexplored areas, including argonaut epigenomic regulation (changes in gene expression independent of changes in the DNA sequence), functional studies of shell and eggcase-forming genes, and ultimately analyses of the population dynamics of A. argo, a cosmopolitan species that is widely distributed throughout the Mediterranean, Australia, and the western Pacific. In addition, there is considerable interest in the sexual dimorphism of the argonauts given their unusual mode of reproduction. Unfortunately, such studies are likely to be hindered by the inability to raise and breed argonauts in captivity and the lack of accessibility to wild-caught samples. Nonetheless, as noted by Yoshida and Setiamarga, “There are a lot of intriguing questions to be addressed. We anticipate that the availability of the genome data of the argonauts will help us to understand not only this species, but also the cephalopods and mollusks in general.”

Featured image: photo taken by Masa-aki Yoshida, used with permission

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers