Oxford University Press's Blog, page 59

January 19, 2023

What is “normal” anyway? How reading changes our thinking about mental health

My generation in my part of the Western world seemed to have got away with it: for decades it was mainly peace, relative prosperity, good general health. The last few years, I need hardly say, have done away with these often-unearned securities of which we had unthinkingly thought ourselves assured. It has been like losing a layer of mental skin, though already it is growing back. We run for cover to the false security of words—the secondary language of explanation and exhortation—when we don’t really know what is going on or how we are doing.

Increasingly I’ve lost faith in public words, public discourse, especially in relation to those personal and private matters described as mental health issues. All I have any trust in now are attempts at human specifics, however flawed and partial: examples that somehow ring an inner bell, ahead of knowing what exactly they are examples of. Reading literature is a good model for this way of thinking. One of Dickens’s struggling young men, David Copperfield, says of his experience that he does not know how far it is particular to him, and how far general to other people too. This messy in-between area is the only holding-ground I know.

From within that area I am going to describe some case-histories arising out of work done by the Centre for Research into Reading, Literature and Society (CRILS) at the University of Liverpool, to which I have belonged.

Josh is aged 26 and taking a Masters degree in engineering. Autistic and of mixed race, all his life, he told our researcher at interview, he has felt that his parents have pressured him to try to fit in, to integrate socially, by teaching him how to behave normally, like a “neurotypical.” That was his second-hand, pre-prepared script for life. But, as part of a study, he volunteered to read a chapter from Dickens’s Great Expectations where the boy Pip on his first visit to the house of Miss Havisham feels overwhelmed, lower-class, a clumsy misfit. This is a quite different script:

I was so humiliated, hurt, spurned, offended, angry, sorry —I cannot hit upon the right name for the smart — God knows what its name was—that tears started to my eyes.

People with autism are told that they do not understand feelings. Josh himself speaks of being unable to “attach” to an experience the name of one distinct emotion. He has not got the skill to be automatically normal. But neither has the boy Pip, and I have seen the manuscript of Great Expectations where Dickens worked hard to accumulate that set of struggling words. Josh felt like Pip—in many situations still, he said, even those he was meant to be used to; never feeling secure or at home. All he could do in place of not having a single grounding term of explanation, he now realized, was to imagine a person and a situation through literature, and memory re-activated by reading.

Nobody seems to have told anyone that what Josh could do here on the inside of experience was finer—more emotionally intelligent, linguistically more subtle—than the routine skill of single-word definition that he was supposed to aspire to. Neuro-bloody-typical, I’d say, of our educational system throughout: no admission that so-called inabilities and insecurities can go much deeper than the easy norms.

Literature has us think differently, with a subtler emotional lexicon. Here, from another CRILS research study, is a mixed community group in a local London library reading Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre aloud together. “Get out of the room; return to the nursery” says the unkind aunt to the orphaned child, on the brink of sending her away to boarding school. “I got up, I went to the door,” Jane recalls, and then, “I came back again.” Instead of going on seamlessly as normal, she will not cross the threshold into her new future before coming back again to do justice to her past:

Speak I must … ‘I will say the very thought of you makes me sick, and that you treated me with miserable cruelty.’

‘How dare you affirm that, Jane Eyre?’

‘How dare I, Mrs. Reed? How dare I? Because it is the truth. You think I have no feelings, and that I can do without one bit of love or kindness; but I cannot live so.’

Jack, a 50-year-old born in the West Indies, says a moment after:

She was on her way out, then she thought, ‘No I’m going to tell, to come back and just tell her.’ I don’t think she thought through whatever she was gonna say but … she’d actually been hurt — it’s not physical but like it — certain things that they say, rock your inner core [puts fist onto chest] … but she said back what … what was in her mind, and the words kept flowing.

Then, through all of an immigrant’s experience, he adds: ‘I don’t see her as a 10-year-old girl.’ The almost physical identification across race, class, age, culture, and history, is a surprise—more powerful than something more determinedly relevant.

“Speak I must” (not simply, “I must speak”) were the words that stuck with another group-member. Anne is a quiet middle-aged woman, saying some months after at an interview:

I am a little bit better at being confident now. If my partner says anything to me, I can talk back to him. Last Wednesday when I went into hospital he said, ‘You’re a disgrace as a woman.’ So when he sat down I said, ‘Do you get some pleasure out of…’ I wouldn’t have said it to him before, ‘Do you get some pleasure out of hurting me …?’

It wouldn’t have been so telling if she had not been able to point to those three particular words that helped get this out of her. Nor would it have been so powerful if she hadn’t had that stuttering difficulty in articulating “hurting me.” If these things seem smaller to you than the big themes, I don’t agree. “Nobody knows,” says Brontë in Jane Eyre, “how many rebellions besides political rebellions ferment in the masses of life which people earth.” A little bit better at being confident now is very careful.

I could go on with more such examples of humans achieving expressive dignity for themselves in the face of their vulnerability and insecurity. But suffice to say this: I feel as if for language I only want literature now, or whatever is more like literature. By that I mean not something fancy or arty; but whatever in the way of feeling, thought, and language helps people to speak more out of the less secure, less normalized parts of themselves. Or there is no health in us.

Featured image by Karolina Grabowska via Pexels (public domain)

January 18, 2023

Monosyllabic moping

About nine years ago or, to be exact, on 17 December 2014, I posted an essay with the title “Moping on a Broomstick.” It was devoted to the idioms to cry mapsticks and like death on a mapstick. Those are exotic phrases, but the verb mope is common, and few people realize how opaque (or rather unpromising) from an etymological point of view many, if not most, monosyllabic verbs are. Look up rip, rap, nip, nap, flip, flap, flop, and others like them, and at best, your unflappable dictionary will cite a few words sounding similarly in other languages or shrug off your curiosity with the all too familiar verdict: “Origin unknown” / “Possibly sound-imitative.” Respectable words (that is, respectable from an etymological point of view) need more than one syllable.

Mop (a kind of broomstick), we learn, has been known since the fifteenth century (that is, already in Middle English), and it surfaced first in nautical use in the form mapp(e). Apparently, those people coined or borrowed this word who mopped the deck. It is curious that mop is cited in a serious dictionary as a variant of mapp(e) without any further comment. Indeed, mop or map, sop or sap, lop or lap—who cares? Incidentally, Latin mappa “cloth; map; (!) napkin” is also a word of unknown origin, perhaps a borrowing. English napkin should have become mapkin. The change of initial m to n has parallels, but an explanation for this change is lacking (-kin is a diminutive suffix, as in lambkin “little lamb”).

There also is a tautological phrase mops and mows (it is tautological, because both components mean the same, that is, “grimace”). Dutch has moppen “to pout” and mop(s) “pugdog” (mops “pug” also occurs in German, and it made its way into Russian). It is natural to assume that mope is a sound-symbolic word: when one sulks and pouts, the lips are in a position to produce mp. Hence also the verb mump and the name of the disease mumps. Both turned up in English texts in the sixteenth century. Mumble made its way into English texts two centuries earlier in the form momele, derived from mum (as in keep mum), but the intrusive b in the middle made it look like mump and the rest.

A classic mop, mopsy and lovable.

A classic mop, mopsy and lovable.(Via PxHere, public domain)

Nothing would be more natural than to say that we are dealing with a bunch of sound-imitative or sound-symbolic words and that the mpm~ mbm complex (a certain “sound gesture”) serves for conveying pouting, puffing, and the like. Characteristically, this complex is not limited to any one language. In Icelandic, the verb mumpa means “to take into the mouth”; it corresponds to Norwegian dialectal mumpa “to chew with one’s mouth full.” In Dutch, we find mompen and mompelen “to mumble,” while German has mumpflen (there is a typo in this form in The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology) and mumpfen “to mumble in eating.”

When an old word like father or come has numerous related forms, historical linguists reconstruct an ancient root from which the recorded forms have sprung up. But it would be unrealistic to expect that, for example, Icelandic mumpa and English mumps are two offspring of some ancient protoroot, even though some such words are rather old (medieval). Can we imagine that words like mope are borrowed from language to language? Dictionaries prefer not to commit themselves to any solution. Sometimes they tell us to “compare” the recorded forms or say nothing.

For the idea of borrowing to make sense, the etymologist should explain where and under what circumstances the word was carried from one speaking community to another. That is the reason dictionaries are so evasive. Indeed, Icelandic mumpa and English mumps sound very much alike, and their meanings are compatible, but the two communities had no contacts in the recent past. German and Dutch, Dutch and English are a different matter. The words mentioned above are not bookish. Parallel development is unlikely. This is the trickiest part of an etymology being discussed here.

Muffs are no longer so popular, or are they?

Muffs are no longer so popular, or are they?(Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

English muff “an awkward person, fool,” etc., which first surfaced in Dickens, resembles Danish mof “clown.” English muff (verb) “to mumble” looks like a borrowing of German muffeln “to sulk” (especially well-known is the German adjective aufmümpfig “aggressively defiant”). Besides, we find German Muff “stench” and of course German and English muff “a cover for the hands,” all of which are “of unknown origin.” Finally, let us not forget how often we are miffed or even driven into a miff. English speakers have been in this state since the seventeenth century. German Mief means “fug, stale atmosphere, stench.” Presumably, English miff and German Mief are “of one blood,” as Mowgli might have put it.

It looks as though in the late medieval and especially in the early postmedieval period, the speakers of Dutch and German began to produce multiple words from the roots mump ~ mump(f) ~ muff ~ miff and that the interminable wars and migrations of that period, with masses of mercenaries and itinerant workers moving from country to country, resulted in the coining of short sound complexes, which, in principle, might mean almost anything, from a puffed-up face (and the emotions associated with it) to a warm glove. Gradually they became known all over the countries in which a Germanic language was spoken. Sometimes such words spilled over into the Romance—and more rarely into Celtic-speaking countries. Italian muffa “mildew” has cognates in several Romance languages. Muff “glove” resembles French moufle and Italian mufti, allegedly from Medieval Latin muff(u)la, a word of unknown (!) origin. It would not be too risky to suggest that muffula came to Medieval Latin from Germanic. The great German philologist Theodor Wilhelm Braune (1850-1926) derived numerous Romance words from Germanic, but his etymologies have been treated with undue caution or ignored.

Words sometimes propagate like mushrooms.

Words sometimes propagate like mushrooms.(Via PxHere, public domain)

I began my story with map and mop. Mope is not far behind. Rather than discussing each word in more detail, I would like to draw some conclusions from the picture offered above. We have a panoply of short m-p and m-f words, seemingly or even obviously belonging together and all of them of unknown origin and spreading like mushrooms. This may be an analog of the most ancient process of word creation: no roots. (I have little trust in the ancient meu ~ mu root.) Rather, sound-symbolic and sound-imitative monosyllables multiplied in a process resembling spore germination. It may be that the “unknown” etymology of such humble words as map, mop, mope, miff, and muff gives us a fairly transparent picture of how things started many thousand years ago. This “model” did not have to be the only one, but its importance need not be ignored. In its sources, language must have been “descriptive.” Abstract meanings, derived forms, and grammaticalized alternations like ablaut (get ~ got, give ~ gave) came later.

All this being said, one should not forget the puzzling fact that the more ancient a language at our disposal is, the longer its words are. “Primitive languages” have words of inordinate length. Language history cannot be reduced to a set of easy rules, and the facts at our disposal contradict one another. Knowing all this, I still think that the map ~ mop ~ mope model is worthy of consideration.

Featured image by Ben Lelis via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

January 17, 2023

OUP celebrates their BMA 2022 Award winners

As we look forward to 2023, let’s take a moment to look back at 2022 and highlight our superb British Medical Association Medical Book Awards 2022 winners.

The Contagion Next Time by Sandro GaleaSpecial category 2022: COVID-19 winner

“Dr. Galea’s book proves it is possible for us to build a healthier world after Covid-19—and the first step is to protect the most vulnerable, whether they’re in our own neighborhoods or across the globe. The Contagion Next Time is truly a must read.”

Katie Couric, award-winning journalist

“The Contagion Next Time looked in depth at the policy context and how COVID-19 exploited the fractures in society. The interdisciplinary approach here, as well as the incremental and intersectoral determinants of the current pandemic (and beyond!), with actionable solutions presented in a lucid yet evidence informed manner are all the reasons this is very appealing as a 360-degree on cumulative learning for a better future.”

Comment from BMA Awards 2022 Panel

In a few short months, COVID-19 devastated the world and, in particular, the United States. It infected millions, killed hundreds of thousands, and effectively made the earth stand still.

Yet America was already in poor health before COVID-19 appeared. Racism, marginalization, socioeconomic inequality—our failure to address these forces left us vulnerable to COVID-19 and the ensuing global health crisis it became. Had we tackled these challenges twenty years ago, after the outbreak of SARS, perhaps COVID-19 could have been quickly contained. Instead, we allowed our systems to deteriorate.

Following on the themes of his award-winning publication Well, Sandro Galea’s The Contagion Next Time articulates the foundational forces shaping health in our society and how we can strengthen them to prevent the next outbreak from becoming a pandemic. Because while no one could have predicted that a pandemic would strike when it did, we did know that a pandemic would strike, sooner or later. We’re still not ready for the next pandemic. But we can be—we must be.

In lyrical prose, The Contagion Next Time challenges all of us to tackle the deep-rooted obstacles preventing us from becoming a truly vibrant and equitable nation, reminding us of what we’ve seemed to have forgotten: that our health is a public good worth protecting.

Browse The Contagion Next TimePurchase The Contagion Next TimeFix IT: See and solve the problems of digital healthcare by Harold ThimblebyGeneral Medicine category winner and BMA medical book of the year runner-up

“This is an extraordinary book: a potent and engaging compendium of revelatory stories, bold insights, wise advice, and fresh thinking.”

Daniel Jackson (Professor of Computer Science, MIT)

“It is such an important book. Our ability to help patients is so reliant on IT and digital solutions. It has the broadest appeal and has achieved something quite impressive. It is not just medically-focused in presenting solutions. A real strength is that it takes examples from outside of healthcare and translates them into healthcare. It should be read by all healthcare staff.”

Comment from BMA Awards 2022 Panel

New technologies like AI, medical apps and implants seem very exciting but they too often have bugs and are susceptible to cyberattacks. Even well-established technologies like infusion pumps, pacemakers and radiotherapy aren’t immune.

Until digital healthcare improves, digital risk means that patients may be harmed unnecessarily, and healthcare staff will continue to be blamed for problems when it’s not their fault.

This book tells stories of widespread problems with digital healthcare. The stories inspire and challenge anyone who wants to make hospitals and healthcare better. The stories and their resolutions will empower patients, clinical staff and digital developers to help transform digital healthcare to make it safer and more effective.

This book is not just about the bugs and cybersecurity threats that affect digital healthcare. More importantly, it’s about the solutions that can make digital healthcare much safer.

Watch Harold Thimbleby discuss his book:

Positive Medicine: Disrupting the Future of Medical Practice by David BeaumontPrimary Care category winner

“We found it thought provoking, challenging conventional thinking without seeking to debunk all conventional wisdom. Every chapter was interesting and different, and the anecdotal style meant the reader was engaged throughout. The book explains how we can help people manage illness and disease, and to enhance their own health. It is a refreshing insight into modern medical thinking.”

Comment from BMA Awards 2022 Panel

When Ivan Illich published Medical Nemesis in 1975, he offered a withering critique of the medical profession and the medical model. “The medical establishment has become a major threat to health,” he said. Nearly half a century has elapsed since then, and things have got worse. In the UK, only 5% of the health budget is spent on prevention. The system is so strained that the rule is often ‘one problem per consultation’. Disease management takes precedence over disease prevention, and a wider perspective on health and wellbeing is largely absent. At least once a month, one third of GPs consider leaving the profession. Patients are referred to secondary care simply because primary care cannot cope.

But doctors want to practise differently.

People also want more. The global health and wellness industry has stepped into the gap. It offers more holistic and whole-person approach that people seek. And it’s big business. It is now estimated to be worth $4.2 trillion per annum.

In this book, David Beaumont proposes a better approach. The current healthcare system is a deficit model. It attempts to address and correct the absence of health, so it is therefore more correctly termed a disease-care system. Positive medicine is an abundance model. It aims not only to help people manage illness and disease, but to enhance their health. Although this book is very specifically about doctors and patients, it will resonate with all healthcare professionals.

Browse Positive MedicinePurchase Positive MedicineJanuary 13, 2023

You are what you eat. Or is your immune system what you eat? [infographic]

You may not immediately connect the food you eat with how your body responds to inflammation. However, over the past decade, researchers have been identifying interactions between the immune system and metabolism, or, how what you eat changes your immune response. These interactions are especially important during times of high energy use, such as during growth or lactation, as activation of the immune system may cause nutrients (energy) to be redirected away from growth or lactation to the immune response (and therefore, survival; Davis, 2022).

As described in a recent Animal Frontiers article, studies in livestock have led to several key insights in this field. The immune and metabolic systems within specific tissues are capable of responding to different environmental cues, allowing individuals to adapt to changing conditions. First used to describe the relationship between obesity and inflammation, “immunometabolism” is defined as the interaction between the immune system and the metabolic system. Importantly, the inflammation related to metabolic conditions is different from that associated with disease.

The interaction between the immune and metabolic systems occurs at several levels, with key cell types and tissues that communicate to coordinate the responses. Fatty acids and reactive oxygen species generated within cells are some of the best-known triggers of immunometabolic adaptations. The liver and fat have been most frequently studied, as these tissues play important roles in both metabolism and immune responses. However, the role of gut microbiota in both inflammation and metabolism has emerged as an important area of study. Antioxidants and other nutrients may be able to regulate the immunometabolic reactions. Thus, nutrition and the immune response are intricately linked with implications for health and performance in both livestock and in humans.

Further study is needed to understand how climate change and other environmental variables will influence immunometabolism, as well as which nutrients most effectively control immunometabolic reactions for optimal health.

Explore the infographic to learn more:

Recommended articles

Recommended articlesTake a further look into immunometabolism in these related articles in Animal Frontiers:

“Immunometabolism and inflammation: a perspective on animal productivity” by Ellen Davis“Immunometabolism in livestock: triggers and physiological role of transcription regulators, nutrients and microbiota” by Juan Loor and Ahmed ElolimyJanuary 11, 2023

Eight classic novels to inspire your New Year [reading list]

Are you searching for inspiration to help further your goals this new year? Reading books offers an easy yet effective way to help navigate life, so who better to turn to than authors of some well-loved Oxford World’s Classics!

To help get you in the right mind space for the new year ahead, here are eight books we recommend to help inspire…

Adventure Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne, translated with an introduction and notes by William ButcherFirst published in 1872 during major technological innovations, Around the World in Eighty Days has been a best-seller for over a century for good reason. The adventure novel offers a post-romantic reality where its modernism lies not in science fiction, but instead, in the experimental technique and the author’s unique ability to twist time and space. The story focuses on Phileas Fogg of London and his valet Passepartout from France embarking on an 80-day journey to circumnavigate the known world on a wager of £20,000.

Read: Around the World in Eighty Days

The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas, edited with an introduction and notes by David CowardPerhaps this is the year to embrace your inner swashbuckler—someone who goes on daring, romantic adventures with bravado—for whom The Three Musketeers will be just the right inspiration! Written in 1844, the historical adventure novel is set between 1625 and 1628 and recounts the quest of a young man named d’Artagnan who leaves his home in Paris in pursuit of joining the Musketeers of the Guard. Although d’Artagnan is unable to join the guard immediately, he befriends Athos, Porthos, and Amis—three of the most formidable musketeers.

Read: The Three Musketeers

Mindfulness Sayings of the Buddha: New Translations from the Pali Nikayas , translated by Rupert GethinWith its origins rooted in 5th century BCE North India, Buddhism, also known as Buddha Dharma, is a philosophical tradition attributed to the teachings of Buddha. One of the main sources for knowledge from the Buddha is the four Pali Nikayas or “collections” of his sayings. The original Nikayas are written in Pali, an ancient Indian language. This edition is a reliable modern translation offering some of Buddha’s most important sayings and reflects the full variety of material contained in the Nikayas: the central themes of the Buddha’ teaching, including his biography, philosophical discourse, instruction on morality, meditation, and spiritual life, and a range of literary styles including myth, dialogue, narrative, short sayings, and verses.

Read: Sayings of the Buddha

Daodejing by Laozi, translated by Edmund Ryden and introduction by Benjamin PennyWritten around 400 BC, the Daodejing is a Chinese classic text that is traditionally credited to the semi-legendary and sage philosopher Laozi. This is the founding text of Daoism and is a fundamental Chinese text that combines philosophy and religion to promote harmony in life. The Daodejing enables the individual, and society as a whole, to find balance, to let go of useless grasping, and to live in harmony with the great unchanging laws that govern the universe and all its inhabitants.

Read: Daodejing

Romance Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen; introduction by Christina Lupton and edited by James KinsleyPublished in 1813, Pride and Prejudice is a novel of manners and one of the most famous love stories of all time. With the arrival of eligible bachelors in the neighbourhood, the lives of Mr and Mrs Bennet and their five daughters are turned inside out and upside down. As the title suggests, a mixture of pride and prejudice deters the two love interests from pursuing each other, and so, misconceptions and hasty judgements bring heartbreak and scandal. But where many conventional love stories go, as does Pride and Prejudice; true understanding, self-knowledge, and love eventually come about.

Read: Pride and Prejudice

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë; introduction by Juliette Atkinson and edited by Margaret SmithWritten in an intimate first-person narrative, this Victorian love story centers on the titular character Jane Eyre. The story reveals the intricacies, importance, and impact of valuing the self, first and foremost. As the love story between Jane and Mr. Rochester unravels deceit, madness, and betrayal, it eventually leads to understanding, self-worth, and deep love. More than being a love story, however, Jane Eyre is an emotionally charged narrative of valuing dignity and freedom through one’s own terms.

Read: Jane Eyre

Courage Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, edited with an introduction and notes by Valerie AldersonLittle Women is a coming-of-age novel that was originally published as two volumes; one in 1868 and the other in 1869. The story follows the lives of four sisters—Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy—as they struggle to support their family’s meager income and actualize their individual dreams. Despite being poor and argumentative, the March sisters are loving and optimistic and are supportive of each other. The characters display high degrees of strong will and independence in their determination to control their own destiny.

Read: Little Women

Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, translated by Charles Jarvis and edited with an introduction and notes by E. C. RileyOriginally published in two parts, the first in 1605 and the second in 1615, Don Quixote de la Mancha was an instant and colossal success. As the years go by, the mythic status of this story strengthens. The story centers on Don Quixote, a poor gentleman from La Mancha, Spain, who seeks romantic honor through absurd adventures. Thanks to his imagination, everyday objects are turned into heroic opponents and serve as stepping stones to greater glory. Ultimately, Don Quixote is a master of being courageous in the face of adversity.

Read: Don Quixote de la Mancha

Featured image by Siora Photography via Unsplash (public domain)

2023 and adventures in the idiom wonderland

2023 is apace, and The Oxford Etymologist welcomes you to another year of adventure and suspense. Please read, wonder (for what else is the wonderland for?), and comment on what you have read, whereas I’ll pick up where I left off in December. How many of our readers know enough about the production of dictionaries? Unfortunately, Samuel Johnson’s definition of the lexicographer (“a harmless grudge”) has been trodden to death and evokes a wan smile at best. No, not a drudge and considering how often people argue about words (that is, engage in logomachy), not necessarily harmless.

Now that my book of idioms (Take My Word for It) has appeared, I decided to say something about its history. For several decades, among other things, I have been busy working on a new dictionary of English etymology. While searching for the relevant literature, I sometimes ran into words that today exist only as components of phrases. Where in the world is the lurch in which we are so often left? How heavy is the brunt one occasionally bears? What does the kibosh look like, and what exactly does one put it on? All was grist that came to my mill, and in the course of the years, I have amassed a sizable collection of articles on such words. This part of the database lay fallow in my office, and I finally decided that it was worth being expanded and published.

Left in the lurch.

Left in the lurch.(Via PxHere, public domain)

The number of idiomatic phrases is incalculable, and any attempt to cover all or most of them would resemble an attempt similar to damming up Niagara with a pitchfork or mopping up the Atlantic. In 1901, Thomas Ratcliffe, an active folklorist, wrote: “The old gossips still use hundreds of unrecorded sayings” (Notes and Queries, 9/VIII, 1901: 14). I may add: “Thousands, rather than hundreds, and not only old gossips.” And no one knows who coined them.

I looked through dozens of so-called weather proverbs (like make hay while the sun shines) and countless misogynistic sayings. It is impossible to decide how old they are. For example, a wicked reference to a whistling woman and a crowing hen (both are supposedly evil) surfaced in print late. My earliest citation goes back to 1850, and the same date appears in the OED. Who coined it and when? Not in 1850! A similar phrase, as it turned out, exists in French. Perhaps we are dealing with a translation from that language. And who was the first French hen-and-woman hater? Hens do sometimes crow, and they supposedly bring bad luck. This is a common superstition. People tend or tended to kill such hens. Incidentally, a correspondent from Cheshire (in northern England) pointed out in 1873 that crowing hens lay eggs quite well. It is beyond my comprehension why whistling compromises a woman. What superstition accounted for that taboo? Or was such a woman considered to be not “feminine” enough? Singing, yes; whistling, no?

Some stories of idioms are truly amazing. Take the phrase fox’s wedding. The reference is to the phenomenon of simultaneous rain and sunshine. Numerous phrases describing this situation exist in the languages of the world. Fox’s wedding (and sometimes jackal’s wedding!) originated in India. Rain and sunshine meet, and the idea of a union makes sense, but what does the fox have to do with it? All kinds of events are described in weather sayings about this “wedding.” They feature animals, the Devil, and human beings, among whom cuckolds and tailors predominate. Tailors, it will be remembered, are traditional figures of fun and disparagement in oral tradition and popular sayings.

However, some languages have innocuous descriptions of “fox’s wedding.” For example, in Russian, people speak of gribnoi dozhd’, that is, literally, “mushroom rain,” implying that after such a shower, mushrooms will pop up in great quantities. A learned 1957 monograph on “Fox’s Wedding” and its analogues was written by the Finnish scholar Matti Kuusi, half the world across Eurasia from India. A study of idioms is not less attractive than a study of words. I may add that one of the rather obscure tales in the Grimms’ collection (No. 38) is called “The Wedding of Mrs. Fox.” A garbled echo of the same tale? Perhaps some student of oral tradition will be able to enlighten us.

Where is the fox?

Where is the fox?(By Lance via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In etymological work, serendipity plays a noticeable role. This is true of both word and phrase history. Once I encountered the odd phrase that beats Akebo (an expression of great surprise). John Hotten, the author of an important slang dictionary (1864), knew it. Judging by this citation, Akebo (or Akeybo) was someone who outwitted the Devil. But why Akebo? I had no clue. As luck would have it, Notes and Queries enjoyed such popularity that almost every county launched its analog (the periodical American Notes and Queries also exists). My small team and I looked through all of them, including the excellent Devonshire and Cornwall Notes and Queries (DCNQ). There, in the 1872 volume, I found the phrase: “That beats Ackytoashy, and Ackytoashy beats the Devil.” (Serendipity!) Another variant has Acky Baugh instead of Ackytoashy. Acky, as I read, seems to be short for Hercules and Archalus, both names having been occasionally used in the county and sometimes confused. Acky Baugh looks like a variant of the name Akebo that puzzled me. I saw the first ray of light that illumined the glom, as Dickens might put it. The light is dim, but beggars can’t be choosers.

The idiom with Ackytoashy occurred in the 1922-23 volume of DCNQ. I wonder whether the correspondent to that volume knew that in the London Notes and Queries for 1872, the alliterative phrase That bangs Banagher, and Banagher beats the world had been discussed in four letters. Banagher resembles Baugh, however slightly, and the legend about the hero who reportedly beat the Devil (a very common plot) was indeed current. Akebo lost all interest. Apparently, we need a hero whose name begins with a B. Strangely, the name of the Russian trickster who outwitted a whole family of devils also begins with a B (Balda, stress on the second syllable; no etymology of the name is known). All this goes a long way toward confirming my belief that before discussing the origin of a word or a phrase, researchers should know everything ever said about it. Otherwise, they are doomed to surprise one another with the news of Queen Anne’s death.

A common or garden grig.

A common or garden grig.(By Riccardo Zampieri via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

By the way, for old or universally known news, my database has three phrases: duck’s news, Piper’s news, and Roper’s news. The world of idioms is amazingly picturesque. For the time being, I am done with it, and I am as merry as a pismire or as a grig. Not everybody knows what pismire and grig mean, and my spellchecker underlined grig. The word, most probably, means “cricket” and has nothing to do with Greek.

A short postscript is perhaps in order. Today, any author of an etymological dictionary faces a formidable difficulty. Anyone can google for an interesting item and get an answer, reliable or suspicious, as the case may be. It is difficult to outwit the computer. I fought this enemy throughout the time it took me to write the dictionary, but it is of course not up to me to decide whether I succeeded in defeating the virtual Akebo, a.k.a. as Baugh and Banagher.

A Happy New Year!

Featured image via PxHere (public domain)

January 9, 2023

Six books from 2022 to add to your 2023 reading list

With the new year unfolding before us and resolutions for the days ahead being made, it’s a good time to reflect on the pivotal moments and people that captured the attention of many in the last year.

Here are six books from 2022 that reviewers and critics loved that you should add to your 2023 reading list:

1. Dancing on Bones: History and Power in China, Russia, and North Korea by Katie StallardDancing on Bones is a deeply researched examination with first-hand reporting on the ground in North Korea, Russia, and China of how the leaders of these three countries manipulate the past to serve the present and secure the future of authoritarian rule. Stallard argues that if we want to understand where these three nuclear powers are heading, we must understand the stories they are telling their citizens about the past.

Dancing on Bones was included in the New Statesman list of Best Books of 2022, in the Financial Times Best Politics Books 2022, and The Sunday Times 15 Best Books on Political and Current Affairs 2022.

2. The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order by Gary Gerstle

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order is a sweeping account of how neoliberalism came to dominate American politics for nearly a half century before crashing against the forces of Trumpism on the right and a new progressivism on the left. Gerstle argues that the condemnations neoliberalism has thus far received fail to reckon with the full contours of what neoliberalism was and why this worldview had such a persuasive hold on both the right and the left for three decades.

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order was shortlisted for the Financial Times as Best Business Books of the Year, and was included in the Financial Times Best Books of 2022, Prospect magazine’s books of the year, and in Le Grand Continent 15 Books to Read in April 2022. It also received coverage in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Republic, New York Review of Books, the New Statesman, Oprah Daily, Los Angeles Review of Books, Daily Kos, and The Nation.

3. La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern by Lynn GarafolaOrder your copy of The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberalism Order →

This is the first biography of twentieth-century ballet’s premier female choreographer, Bronislava Nijinska. Nijinska experienced the transformative power of the Russian Revolution and created her greatest work—Les Noces—under the influence of its avant-garde. Nijinska’s career sheds new light on the modern history of ballet and of modernism and reveals the sexism pervasive in the upper echelons of the early- and mid-twentieth-century ballet world—barriers that women choreographers still confront. La Nijinska was included in the New Yorker Best Books of 2022 So Far, in The Times 7 Best Film and Theatre Books 2022, and received coverage in The Telegraph, The Washington Post, The Nation, The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Spectator.

4. Mussolini in Myth and Memory: The First Totalitarian Dictator by Paul Corner

Corner looks at the brutal reality of the Italian dictator’s fascist regime and confronts the nostalgia for dictatorial rule evident today in many European countries. By linking past history and present memory, Corner’s analysis constructs a picture of the realities of the Italian regime and examines the more general problem of why people look for strong leadership and take refuge in the memory of past dictatorships.

The Economist declared “seldom is the publication of a book more topical,” and The Financial Times observed the book is “timely, balanced, succinctly argued and thoroughly convincing.” Mussolini in Myth and Memory was also included in Financial Times Best History Books 2022 and in History Today Best Books of the Year 2022.

5. Disorder: Hard Times in the 21st Century by Helen Thompson

Thompson explains the historical origins of the political shocks of the past decade, and why we live in the political times we do in Disorder. This book recounts three histories—one about geopolitics, one about the world economy and one about western democracies—and explains how in the years of political disorder prior to the pandemic the disruption in each became one big story.

Disorder was shortlisted for Financial Times Best Business Books of the Year award, selected as one of the New Statesman Best Books of 2022, the Financial Times Best Summer Book in Economics, and Five Books Best Business Books of 2022, along with coverage in The New York Times, New Yorker, The Spectator, The Times, Literary Review, and Prospect.

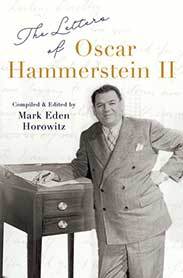

6. The Letters of Oscar Hammerstein II by Mark Eden Horowitz

This epistolary book is a collection of letters from and to American musical theater’s greatest innovator, Oscar Hammerstein II. It provides an entertaining look behind the scenes of Broadway. Hammerstein II basically invented the modern American musical, first with Show Boat, and then in his celebrated collaborations with composer Richard Rodgers on Broadway classics like Oklahoma!, Carousel, and The King and I that continue to captivate audiences today.

The Letters of Oscar Hammerstein II was included in NPR Best Books 2022 and was recommended by Lin Manuel Miranda.

January 6, 2023

Which book matches your New Year’s resolution? [Quiz]

Are you setting goals for 2023? Take our quiz to find out what your resolution should be for the new year. Whether you’re looking to stress less or spend more time outside, we have books that can help you reach your goals this year.

What’s your New Year’s resolution?Stress Less

The past few years haven’t exactly been easy, that’s for sure. With that in mind, it’s no wonder you’re looking to lower your stress levels. If you want to stress less and chase more happiness this year, Living for Pleasure would be a good place to start. This easy-to-read and approachable addition to the Guides to the Good Life Series offers a lively, jargon-free tour of Epicurean strategies for diminishing anxiety, achieving satisfaction, and relishing joys.

Readers will walk away knowing more about an important school of philosophy, but moreover understanding how to get what they want in life–happiness–without the anxiety of striving for it.

Incorporate More Self-Care Into Your Life

When life is always on the go it can be hard to take care of yourself. In the coming year you aspire to incorporate more self-care into your life, and you deserve to! After all, people are naturally drawn to information on how to improve self-care, create a richer circle of friends, develop and maintain a healthy perspective, and the New Year is a great time to focus on “alone-time,” not simply as forced isolation but a venue for new personality development. The newest edition of Bounce presents a readable and useful discussion of resilience in stressful times and will be the perfect companion to you on your self-care journey.

Enriching the balance and meaning of life by better understanding stress and creating your own self-care protocol, Bounce shows you how to live life to the fullest.

Embrace Spirituality

You’d like to get in touch with your spiritual side this year! This is a rewarding and somewhat difficult resolution, but Our Hearts Are Restless can help make the journey a little smoother. This new title acts as a guided tour of spiritual autobiography that grants readers new insights and appreciation of the genre.

The author, Richard Lischer, is a perceptive reader and an engaging guide in the art and craft of spiritual writing. Our Hearts Are Restless shows readers how history’s most brilliant spiritual writers have sought and found a pattern of meaning in the face of tragedy, conflict, and the responsibilities of daily life.

Get Outside More

Public spaces are vital to a healthy civic life, there’s no argument there. And, as the eminent scholar of public space Setha Low argues in Why Public Space Matters, even fleeting moments of visibility and encounter in these spaces tend to foster a broader worldview and our willingness to accept difference. Such experiences also enhance flexible thinking, problem solving, creativity, and inclusiveness.

That’s why we think you should absolutely read Why Public Space Matters if your 2023 resolution is to get out more! Let this thought-provoking title inspire you to get out there and experience all that’s out there to enjoy.

Sharpen Your Mind

We’d all like our minds to be a little sharper, right? Whether you want to be less forgetful or are looking for an edge in your next academic pursuit, Why We Forget and How to Remember Better will give you the tools you need to optimize your brain!

This informative new title uses the science of memory to empower you with the knowledge you need to remember better, whether you are a college student looking to ace your next exam, a business professional preparing a presentation, or a healthcare worker needing to memorize the 600+ muscles in the human body.

Pick a drink

Where would you book your dream vacation?

What is your favourite way to relax?

Choose a wordWhat is one habit you’re trying to stop?

You would describe yourself as:How do you see the new year?Quiz Maker – powered by Riddle

January 5, 2023

Infectious disease in the twentieth century

Now that COVID-19 seems to be gradually and painfully transitioning from a pandemic to an endemic disease, it would be instructive to place its appearance in the history of infectious disease during the twentieth century.

In the first half of the century, the three great killers among endemic diseases—smallpox, malaria, and tuberculosis—raging around the world (we think today of malaria as a tropical malady but in the 1920s there were outbreaks as far north as Siberia) were each responsible for more deaths than the 80 million who died in both world wars. Innovations stemming from the Second World War, an immense hothouse of technological progress, made it possible to contemplate combatting infectious disease on a global scale. A whole new class of drugs, the anti-microbials, were brought to production during the war, as was chloroquine, a very effective anti-malarial. Another product introduced during the war, the insecticide DDT, opened the prospect of eliminating or at least greatly reducing mosquitoes, carriers of infectious diseases, especially malaria.

In the three decades following 1945, wartime innovations would be used to combat infectious disease on a global scale. Anti-microbials would kill the bacteria responsible for a wide range of infectious diseases; public health measures, including combatting mosquitoes with DDT, would eliminate the conditions for others to spread. Antimicrobials had no effect on viruses, but by taking up the previously existing practice of vaccination on a much larger scale, and introducing new vaccines, viral diseases could be eliminated.

“In the first half of the twentieth century, smallpox, malaria, and tuberculosis were each responsible for more deaths than both world wars.”

A combination of antibiotics made it possible to cure tuberculosis, which had previously been impossible. (In the 1930s, half the patients released from English tuberculosis sanitoria as cured or greatly improved died within five years.) The UN’s World Health Organization launched a global campaign to eliminate smallpox entirely, supported by both the Western Powers and the Eastern Bloc—a true rarity during the Cold War!—with the last case of the disease recorded in 1977. A similar WHO campaign, the Malaria Eradication Program, combined massive spraying of DDT to kill mosquitoes with mass distribution of chloroquine in the hope of disrupting the complex life-cycle of the protozoan that causes malaria. Unlike smallpox, malaria was not eradicated, but in the three decades after 1945 its presence was greatly reduced in southern and eastern Europe, and in the more temperate or drier regions of Asia, the Americas, and Africa. Overall, infectious disease mortality rates plummeted and life expectancy rose rapidly around the world between 1945 and 1975/80. By the 1970s, it seemed that infectious diseases had been marginalized as a threat to human life; medical research moved on to tackling degenerative diseases, particularly cancer and arteriosclerosis, and elucidating the social conditions and practices, the so-called “risk factors,†that encouraged their appearance.

The last two decades of the twentieth century saw a completely unexpected return of infectious disease. One reason was the growth of hitherto unknown, new forms of viral disease, above all HIV/AIDS, which spread rapidly across the world in the 1980s, bringing in its wake wild fears, xenophobia, and conspiracy theories about its origin. The second was the appearance of resistance on the part of bacteria and insects against drugs and chemicals that had previously been so effective against them. The number of cases of malaria expanded rapidly in the tropics; antibiotic resistant strains of tuberculosis began to make an appearance, as did the so-called “super bugs,†MRSA, methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. Infectious disease mortality rates rose, and the increase in life-expectancies slowed to a crawl. By the 1990s, there were growing expectations of a global infectious disease apocalypse in these new conditions.

For three decades, the apocalypse never came to pass. AIDS remained restricted to demographic niches and never spread among the general population. A new class of drugs, the anti-retrovirals, turned the disease from a death sentence into a treatable chronic condition. Africa was the great exception to these conditions and the wide spread of the illness, especially in conjunction with tuberculosis and malaria, as well as the inability to afford the very expensive antivirals, resulted in something on the order of 15 million deaths. Even in Africa, the number of both new cases and deaths has been gradually declining over the last 20 years, largely because Brazilian and Indian pharmaceutical manufacturers ignored the patents on anti-retrovirals and made them available for much lower prices.

By the second decade of the twenty-first century, it seemed that infectious disease had been deglobalized, restricted to the world’s poorest countries, whose inhabitants might fear contracting AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, or Ebola, while in the Americas and most of Eurasia, lifestyle issues, such as smoking cigarettes, eating fast food, and not getting enough exercise, leading to deaths, often at advanced ages, from cancer, heart disease, or type-two diabetes, appeared as far greater public health risks. COVID-19 seems to have changed that, the disease spreading worldwide within a few months of its outbreak in Wuhan and bringing in its wake fears, xenophobia, and conspiracy theories, reminiscent of the appearance of HIV/AIDS during the 1980s. A consideration of the victims shows a different story: disproportionately the elderly and those suffering from life-style-related conditions, including high blood pressure, smoking, obesity and type-two diabetes. Excess mortality rates (the best measure of the disease, since its diagnosis, especially at the outset, was very uncertain) have been highest in globally lower-middle-income countries, such as Peru or Serbia, where these lifestyle conditions exist to a much greater extent than in the world’s poorest and—perhaps surprisingly—most affluent countries. COVID-19 has been an odd hybrid illness, a pandemic caused by a virus, spreading most strongly in countries and social groups where the risk factors for degenerative disease were greatest.

None of this history provides any certainty, of course, about the future nature and course of diseases around the world or in any of its regions. But global experiences with infectious disease over the last century do suggest that seemingly irreversible trends—like the post-1945 decline of infectious disease—are indeed reversible and that an increase in globalization, that is in capital, goods, ideas and people crossing national borders, continents and oceans, does not necessarily lead to the homogenization of conditions around

Featured image by Martin Sanchez on Unsplash, public domain

The post Infectious disease in the twentieth century appeared first on OUPblog.

January 1, 2023

Can you itch an itch?

Reading Dan Chaon’s novel Sleepwalk last summer, I noticed his use of the verb itch to mean scratch. The main character makes observations like these:

“I think, and itch my beard thoughtfully.”

“I itched the band that held my ponytail”

“I reached down to itch my thigh”

I imagined that the choice of the nonstandard itch was part of the author’s fleshing out of the character, a fifty-year-old mercenary with many aliases. (Dan Chaon, if you are reading this, feel free to weigh in).

The use of itch for scratch reminded me of the way that learn gets substituted for teach, as in “That’ll learn you.” Learn for teach used to be common and it goes way back. It occurs in Much Ado about Nothing where Claudio says, “Sweet prince, you learn me noble thankfulness,” and the Oxford English Dictionary gives examples of learn meaning teach in the Wycliffe and Coverdale Bibles. By the time of Webster’s 1928 dictionary, however, the usage was considered “inelegant” and “improper.” The Dictionary of American Regional English dubs it “somewhat old-fashioned” and “especially frequent among speakers with grade school education or less.”

Then there is the use of borrow for lend. The Dictionary of Regional American English identifies it as “scattered” through the country but used especially around the Great Lakes area and especially “among young speakers and speakers with grade school education.”

The use of itch for scratch is not widely documented in dictionaries. It is mentioned in The Random House Unabridged, which lists it as informal, with the meaning “to scratch a part that itches.” The American Heritage Dictionary gives the meaning “to scratch (an itch)” without any usage label. But the scratch sense is absent from both the Dictionary of American Regional English and the Dictionary of Americanisms on Historical Principles, and it isn’t noted in the Oxford English Dictionary, Webster’s Second, or Webster’s Third. My colleague Kirk Hazen noted a 1947 OED entry where itch seems much like scratch: “With long sensuous strokes he smoothed a patina of paint down the chairlegs, then itched with fussing dabs the corners and underneath.” The OED gives the meaning as “to cause an itch,” but “scratch” seems just as likely.

David Minger, a linguist who uses itch and scratch interchangeably, suggests the two words are “welded at the hip semantically” and have similar sounds as well. That makes sense. If some article of clothing feels scratchy to us, we say that it itches. We also say itch when we get poison ivy or bug bites. Sharp objects, like cat claws or rough wood, don’t itch, they scratch.

It’s not hard to imagine language learners sorting out the semantics of itches and scratches with scratching as external (from cats) while itching includes both skin irritations and the remedy as well.

As people gain exposure to the standard usage, they may adjust their usage accordingly, scratching pushing out itching. But some people may not adjust to the standard. And some may use both forms, sometimes scratching an itch sometimes itching it.

I did some targeted listening. One speaker who ordinarily uses scratch switched to itch to refer to a recurring irritation. That got me thinking about that some people may use itch for persistent itches and scratch for less persistent ones.

I asked a former student of mine, Emily Negus, who has a particularly good ear for informal language. Emily said her mom uses “don’t itch it” when telling her not to scratch at poison oak. Emily came to the same conclusion as me about itch and scratch:

When I hear the phrase “he scratched it” I think of someone scratching at an itching spot a couple of times. But when I hear the phrase “he itched it” I think of someone repeatedly scratching an itchy area. Thus “itching it” has a longer duration of scratching than “scratching it.”

It’s possible too to find suggestive textual examples, like this from a 1925 New York State worker’s compensation case involving dermatitis. The arbitrator comments that:

The evidence is, from the witness here, that he did suffer from a skin disease and itched himself, as some people call it, or rubbed himself on account of that disease so much that his fellow employees complained…

And there are plenty of examples of dogs and other animals referred to as persistently “itching themselves.” I’ll spare you those examples.

It’s beginning to look like there is more to the itch-versus-scratch difference. Dictionaries have barely scratched the surface on this.

Featured image by FOX via Pexels, public domain

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers