Oxford University Press's Blog, page 57

February 15, 2023

A new beginning: the verb “start”

A new beginning: the verb “start”

Last week (8 February 2023), I discussed the murky etymology of the verb begin. As pointed out there, begin is a rather abstract concept. There must have been some concrete idea, inspired by people’s everyday activities, that underlay begin in the remote past. To make this suggestion more convincing, we may examine the history of the verb start, because in trying to discover the origin of a problematic word, it is always useful to look at the history of its synonyms. What ifat least one of them throws a dim light on begin? Alas and alack, in our case, this hope wanes only too soon. For instance, initiate (from French, from Latin) goes back to in (a preposition) and īre “to walk”; commence has the same root. And start is even more obscure than begin. It has an interesting history, but the paths of the two verbs never cross. Therefore, we will have to examine start for its own sake, with only sometimes throwing a side-glance at begin.

Riddles appear at once. We know the verb startle. The suffix –le is said to be frequentative, that is, to refer to a repeated action. A similar explanation will satisfy us in dealing with twinkle, giggle, and fiddle–faddle (among many others). Surely, startle does not mean “to start many times.” However, the Old English for start meant “to jump, leap.” “To jump more than once” (in fear, when frightened?) makes good sense. This then is at least one way the concept “begin” can develop (from jumping, from initiating movement).

A new beginning.

A new beginning.Photo by Andrea Piacquadio (public domain)

While looking for cognates of start, we notice Dutch storten and German stürzen “to fall precipitously; rush, etc.” Such senses also accord reasonably well with “begin,” but nothing in the root –gin suggests the idea of a rapid movement. The group gin is not sound-imitative, and no one will sense the smallest trace of sound symbolism in it. The complex st-r is another matter: it “produces vibrations” and makes one think of vigorous efforts. Here is a short list of native and borrowed str-words in English (without an intervening vowel): straight, strain, strangle, strap, stream, strict, stride, strident, strife, strike, strip, strive, stroke, strong, and strut.

Symbolism in the emergence of start and its family was noticed long ago. In 1908, Heinrich Schröder, an astute and bold historical linguist, wrote an article about Germanic words having the roots stel– (which won’t interest us) and ster-. The article appeared in a leading German periodical. Schröder cited dozens of such words and argued that they were sound-symbolic and sometimes sound-imitative. Consequently, he made the same point I made above, but I jumbled together native and borrowed words, to emphasize the panhuman role of the group in question. In his view, the combinations str– suggested the idea of strength, precipitation, and the like. Forty years later, J. H. van Lessen, another astute scholar, this time a Dutch one, searched dictionaries for similar words and came to the same conclusions. Apparently, Van Lessen missed Schröder’s work. This is not said to belittle my distant predecessor’s achievement. Researchers have a hard time finding the relevant literature on word origins Outside Greek/Latin, Finnish, and now English, etymological bibliographies do not exist, and some of those that exist are woefully outdated.

Startling news.

Startling news.Photo by Andrea Piacquadio (public domain)

What then is the closest kin of start? First and foremost, we notice Dutch storten and German stürzen “to rush, plunge; fall.” All the rest is less clear. These are the Modern English words Schröder mentioned in his paper: stark, start “tail” (outside dialects, extant only in the name of the bird name redstart) and stork. The meaning of some of them goes back to the idea of immobility (a precipitous movement results in a fall!). He also listed stroke, strut, strumpet (!), and starve. The problem is that in dealing with sound symbolism, one seldom knows where to stop. However, only one word in the list given above merits our attention, namely, redstart or, rather, its second component, start “tail.” Here, you can see this bird in a picture. Its tail is nothing out of the ordinary, but straight it certainly is.

Skeat wrote at start “to move suddenly” that some even (!) connect it with Old Engl. steort “tail.” This even was not said in disapproval: he simply could not decide whether the connection is valid. The Century Dictionary, a major American contribution to lexicography in the early nineteen-hundreds, stated: “The explanation given by Skeat that the verb [start] meant originally ‘turn tail’ or ’show the tail’, hence turn over suddenly… is untenable.”

Here is a redstart, tail and all.

Here is a redstart, tail and all.Photo by Charles J. Sharp via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

This is a strong statement, considering the dependence of that dictionary on Skeat. Charles P. G. Scott was an excellent etymologist, and such a curt verdict (“untenable”) without any arguments was not typical of him. Also, start “tail” and start “turn” can be allied in more ways than one. Henry Cecil Wyld, an outstanding philologist, to whose dictionary I refer with great regularity, noted cautiously that perhaps (!) start and the Old English word for “tail” share the same root. Likewise, Elmar Seebold, the modern editor of Kluge’s German etymological dictionary, wrote at stürzen that the meaning “fall” may have developed from Sterz “tail,” but that this is not very probable (!). One should be cautious when it comes to etymology: the land underfoot is in most cases boggy.

Thus, the ultimate origin of start is not quite clear, but perhaps it meant something like “to fall or rise precipitously, jerk,” hence “to set in motion” and “begin.” More definite is the etymology of stark–naked, which I am adding to my today’s story for good measure and for the sake of entertainment. English stark, like German stark, once meant “strong,” then “rigid, stiff; sheer, absolute,” and finally, “naked” in “stark-naked.” But stark-naked is a curious alteration of start-naked, as if “naked to the tail.” A stark-naked redstart might serve as an emblem created for this blog post. Despite all the uncertainty about the main question, our ramblings have not been quite fruitless. We can say with confidence that the impulses behind coining words for “begin” are various and hard to discover. Start is sound-symbolic and perhaps partly sound-imitative. Begin will continue languishing in its partial obscurity.

Stark-naked indeed.

Stark-naked indeed.Image by Karen Arnold (public domain)

I have more than once expressed my doubts about the existence of some ancient roots to which it is customary to trace the words recorded in Old Germanic and Indo-European. As an example, I may cite the case of the putative root ster-. There were allegedly five such homonymous roots. From one of them, meaning “stiff,” we are told to have stark, stork, strut, start, startle, and starve. The other four yielded strew, star; steal, and stirk “a yearling heifer or bullock.” If, motivated by a sound-symbolic complex like str, people created the words mentioned in this post, one cannot help doubting the existence of an ancient unifying root, and my perennial metaphor of mushrooms on a stump (similar but rootless units) may look like a more viable metaphor of word creation in the remotest past and also in the present, especially when slang is at play.

To conclude: begin remains without a convincing etymology, while start, if we accept its symbolic past, seems to be less problematic. Some of their synonyms, including enter, are transparent metaphors.

Featured image by Andrew Thomas via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Explore environmental history in eight books [reading list]

![Explore environmental history in eight books [reading list] - OUPblog, Oxford University Press](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1676553762i/33947129.jpg)

Explore environmental history in eight books [reading list]

Environmental history only emerged a few decades ago but has already established itself as one of the most innovative and important new approaches to history—one that bridges the human and natural world, the humanities and the science, and is truly international in its approach.

To understand the field better and showcase some of the recent research, we’re sharing eight of our latest titles in environmental history for you to explore, share, and enjoy.

1. Sweet Fuel: A Political and Environmental History of Brazilian Ethanol by Jennifer EaglinAs the hazards of carbon emissions increase and governments around the world seek to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, the search for clean and affordable alternate energies has become an increasing priority in the twenty-first century.

However, one nation has already been producing such a fuel for almost a century: Brazil. Its sugarcane-based ethanol is the most efficient biofuel on the global fuel market, and the South American nation is the largest biofuel exporter in the world.

2. Scars on the Land: An Environmental History of Slavery in the American South by David SilkenatBuy Sweet Fuel

A comprehensive history of American slavery that examines how the environment fundamentally formed enslaved people’s lives and how slavery remade the Southern landscape.

Over two centuries, from the establishment of slavery in the Chesapeake to the Civil War, one simple calculation had profound consequences: rather than measuring productivity based on outputs per acre, Southern planters sought to maximize how much labor they could extract from their enslaved workforce.

3. Unredeemed Land: An Environmental History of Civil War and Emancipation in the Cotton South by Erin Stewart Mauldin

An innovative reconsideration of the Civil War’s profound impact on southern history, Unredeemed Land traces the environmental constraints that shaped the rural South’s transition to capitalism during the late nineteenth century.

Bridging the Antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction periods, Unredeemed Land powerfully examines the ways military conflict and emancipation left enduring ecological legacies.

4. Panda Nation: The Construction and Conservation of China’s Modern Icon by E. Elena SongsterBuy Unredeemed Land, new in paperback

Panda Nation links the emergence of the giant panda as a national symbol to the development of nature protection in the People’s Republic of China.

The panda’s transformation into a national treasure exemplifies China’s efforts in the mid-twentieth century to distinguish itself as a nation through government-directed science and popular nationalism.

The story of the panda’s iconic rise offers a striking reflection of China’s recent and dramatic ascent as a nation in global status.

5. Frozen Empires: An Environmental History of the Antarctic Peninsula by Adrian HowkinsBuy Panda Nation

Perpetually covered in ice and snow, the mountainous Antarctic Peninsula stretches southward towards the South Pole where it merges with the largest and coldest mass of ice anywhere on the planet. Yet far from being an otherworldly “Pole Apart,” the region has the most contested political history of any part of the Antarctic Continent.

Since the start of the twentieth century, Argentina, Britain, and Chile have made overlapping sovereignty claims, while the United States and Russia have reserved rights to the entire continent. The environment has been at the heart of these disputes over sovereignty, placing the Antarctic Peninsula at a fascinating intersection between diplomatic history and environmental history.

6. Valuing Clean Air: The EPA and the Economics of Environmental Protection by Charles HalvorsonBuy Frozen Empires

The passage of the Clean Air Act and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 marked a sweeping transformation in American politics. In a few short years, the environmental movement pushed Republican and Democratic elected officials to articulate a right to clean air as part of a bevy of new federal guarantees.

Valuing Clean Air examines how the environmental concern that propelled the Clean Air Act and the EPA coincided with economic convulsions that shook the liberal state to its core.

7. The Southern Key: Class, Race, and Radicalism in the 1930s and 1940s by Michael Goldfield

The Southern Key charts the rise of labor activism in each and then examines how and why labor organizers struggled so mightily in the region.

Drawing from meticulous and unprecedented archival material and detailed data on four core industries—textiles, timber, coal mining, and steel—Michael Goldfield argues that much of what is important in American politics and society today was largely shaped by the successes and failures of the labor movements of the 1930s and 1940s.

8. The Making of Our Urban Landscape by Geoffrey TyackBuy The Southern Key, now new in paperback

Britain was the first country in the world to become an essentially urban county. And England is still one of the most urbanized countries in the world.

The town and the city is the world that most of us inhabit and know best. But what do we actually know about our urban world—and how it was created?

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan: the past’s resemblance to the present

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan: the past’s resemblance to the present

On a cold, sunny afternoon, a host of delegates entered the General Assembly of the United Nations in Manhattan. When everyone had found their seats and settled in, the assembly’s president called the room to order. After holding a minute of silence for prayer and meditation, he quickly ran through a handful of administrative issues before turning to the matter that had brought the assembly together that day.

This was an emergency session. At its heart were questions about state sovereignty, political self-determination, and the nature of international relations. The United States’ representative declared: “Today we are faced with a challenge to the principles of the [UN] Charter as grave as any that necessitated our meeting during previous crises.” Another state representative told the gathered crowd:

While most of us, for decades, had our very physical, cultural and social existence flouted, some of the founders of the United Nations have never known foreign subjugation, the denial of their very being or the situation of the dominated with no other right than that of submission … The issue before us today, in its brutality, seems to us to be shaking the foundations of our present-day civilization.

In the final vote, the General Assembly overwhelmingly passed a resolution condemning foreign invasion and calling for “the immediate, unconditional and total withdrawal of foreign troops.”

Current observers would be forgiven for thinking this exchange refers to the meeting of the UNGA that took place on 2 March 2022, in which an emergency session debated the Russian invasion of Ukraine and passed a resolution condemning Russian military action. In fact, this exchange took place more than 40 years ago, at the UN’s sixth emergency session, 10-12 January 1980, which focused on the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, December 1979Soviet troops had entered Afghanistan in late December 1979 to shore up the struggling Marxist regime, headed by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan. Soviet troops, the Politburo insisted, were upholding a Soviet-Afghan treaty of friendship in the face of concerted attacks by Afghan resistance fighters and their Pakistani, Chinese, and US allies. However, as critics were quick to point out, the Soviets put in place a new ruler, Babrak Karmal, who had been exiled from the previous government and had been nowhere near Kabul in the run up to the intervention.

“Many of the issues discussed in 2022 resembled those in 1980: sovereignty, self-determination… foreign intervention, the nature of nationhood, and the power of nationalism.”

Many of the issues discussed in 2022 resembled those in 1980: sovereignty, self-determination, international legal debates about foreign intervention, and the nature of nationhood and the power of nationalism. However, the response to events in Afghanistan was more unified. China and the United States notably were in full agreement in decrying Soviet army movements (and in providing covert aid to the regime’s opponents). States across the Global South likewise were highly critical. For them, the Soviet invasion, coming as it did in the declining years of European decolonization, represented a dangerous precedent. In effect, it appeared as the re-colonization of a non-Western state that had struggled to and succeeded in gaining its independence. Consequently, states of the Global South showed a largely united front in criticizing Soviet activities.

Over the course of the 1980s, the collective anger of the General Assembly resulted in a series of motions demanding a Soviet withdrawal and the return of Afghan sovereignty. It also forced the UN to take a key mediating role. Over the next nine years, UN diplomats worked with their counterparts in Moscow, Washington, Islamabad, and Kabul to negotiate a Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan. That withdrawal would not be complete until February 1989, and even then, fighting in Afghanistan would not stop for another forty years. Notably the UN-led negotiations did not invite the perspectives of Afghan resistance groups. In turn, talks offered little scope for a concrete political settlement, given that Afghanistan was the site of a civil war between Afghans, not just a foreign intervention.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan: a global conflictThe Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was part of a fundamentally global conflict. In part, this was due to the Cold War context in which it took place. Soviet decision-making necessitated a response from the United States. So, while the Soviets supported the Afghan Marxists, the Carter and Reagan administrations chose to aid its opponents, the Afghan resistance groups who fought to overthrow the socialist regime. However, Cold War conflict reveals only one aspect of the civil war’s inherent internationalism. The UN’s diplomatic intervention reveals another, in which international organizations played a key role. Examining the motivations and activities of different Afghan interest groups reveals a host of other global connections, both ideological and practical.

“The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was part of a fundamentally global conflict.”

The Afghan civil war of the 1980s was the culmination of a much longer conflict over the nature of politics in Afghanistan (and across the decolonizing world more broadly). Afghans sought to fundamentally reshape Afghan political, social, and economic dynamics, not only looking to local circumstances but couching their ideas in far more universalist terms and drawing in ideas circulating across the decolonizing world. Afghan Marxists thus linked their political and economic endeavours to those undertaken in Vietnam and Ethiopia or Cuba. Afghan Islamists, meanwhile, were tied into transnational Islamic networks and created their own offices across Europe and North American to lobby for political and financial support.

By exploring some of the nodes across the world in which decisions made and networks created shaped the subsequent civil war in Afghanistan, what becomes clear is that the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan cannot be understood purely through the perspective of state actors, great power decision-making activities, or in the realms of interstate relations. It was a complex war that involved a wide range of interest groups, each of which had different aims: winning the Cold War, returning to earlier status quo in international relations, reshaping the relationship between religion and politics in state and international politics, reconfiguring Afghan nationhood and the broader relationship between nation and state. It was simply impossible for all these different motivations to be reconciled—by the UN’s negotiators or in bi- or multilateral relations.

Select from numbers 1 to 13 on our interactive map to explore these nodes across the world:

Click here to view the accessible version of this interactive content

February 13, 2023

After Burns: recovering Scottish poetry

After Burns: recovering Scottish poetry

Scottish poetry produced in the long eighteenth century might strike you as at once familiar and unknown. Familiar because it includes among its ranks one of the world’s most iconic bards, Robert Burns, as well as one of the most influential novelists of all time, Sir Walter Scott. Unknown because Burns and Scott still overshadow their peers, some of whom have been out of print for decades, even centuries.

Struggling to make an impact on the cultural scene of their age, for a variety of personal and social reasons, some of these poets and songwriters published only a single and often small selection of works. A lot of the pieces even appeared posthumously, for the first time, years after the writers’ deaths. Some who were successful at the time, whether critically or commercially, have long fallen out of public view. A younger contemporary of Scott, Thomas Campbell has largely been sidelined, even though he once enjoyed great prestige across continental Europe—statues and clubs were raised in his honour. Largely forgotten, the Falconar sisters produced two joint collections of highly sophisticated poems when they were barely teenagers. What became of them after 1791 remains a tantalising mystery.

A hugely popular weaver poet, Robert Tannahill had a stylistic range that far extended beyond the admittedly unmissable influence of that ingenious fellow labouring poet, Burns. At the other end of the class spectrum, Lady Bury had her own thoughtful songs that will long stay with you (“On Seeing Some Withered Roses Thrown Away”: “Wipe off the yet impassion’d tear, / And turn my heart to peace”). Poets from all walks of life honoured their entire nation (under the labels of “Scotland”, “Scotia”, or “Caledonia”); others focused on local communities, whether it’s Lord Byron’s Aberdeenshire, Alexander Douglas’s Fife, Robert Fergusson’s Edinburgh (“Auld Reekie”), Richard Gall’s Ayrshire, Alexander Geddes’s Linton, John Mayne’s Glasgow, David Vedder’s Orkney, or Margaretta Wedderburn’s Dalkeith. Universal literary and real-world themes sustained their attention, just as they sustain ours, whether it’s the seasons (James Thomson’s “Winter”, Michael Bruce’s “Elegy: To Spring”, or Eóghann MacLachlainn’s “An t-Earrach”), nature (Duncan Ban Macintyre’s “Seachran Seilge” or Jean Glover’s “O’er the Muir Amang the Heather”), marriage (Janet Graham’s “Wayward Wife”, Joanna Baillie’s “Song, Woo’d and Married and a’’, or Robert Lochlore’s “Marriage and the Care o’t”), or—the ultimate one—death (Robert Blair’s The Grave or Burns’s “Death and Doctor Hornbook”).

“Scottish poetry was—and is—a living tradition open to all.”

This period in literary history generated many leading songwriters whose lyrics were designed to be sung in the taverns, churches, or clubs, and even at events. Even popular songs needed a lot of help to reach print. “Auld Robin Gray” had appeared in David Herd’s indispensable Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads, Etc. in 1776, and remained a fixture of Scottish anthologies throughout the ensuing decades. Not until Walter Scott produced an authoritative edition for the Bannatyne Club in 1825, having quoted it in his 1823 novel The Pirate, did its author Lady Anne Barnard receive the credit due to her. A conventional love ballad in some ways, its unfurling of plot over repeated units of sound creates an utterly captivating effect:

My heart it said na, and I look’d for Jamie back;

But hard blew the winds, and his ship was a wrack;

His ship was a wrack! Why didna Jenny dee?

Or, wherefore am I spared to cry out, Woe is me!

Another popular songwriter, Anne Hunter, had a canny knack for inhabiting all sorts of voices—among them, Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots (“I Sigh, and lament me in vain”) and even a mermaid (“Come with me, and we will go / Follow, follow, follow me”). A mainstay of nineteenth-century anthologies though she composed anonymously, Carolina Oliphant, Lady Nairne had set many of her most memorable songs to traditional tunes:

Sweet’s the laverock’s note and lang,

Lilting wildly up the glen;

But aye to me he sings ae sang,—

Will ye no come back again?

(“Will ye no come back again?”)

Scottish poetry was—and is—a living tradition open to all. The unduly neglected Christian Milne excelled in this sort of seemingly artless but highly artful metapoetry. Printed in the disarmingly titled collection Simple Poems, on Simple Subjects (1805), her epistle “To a Lady who said it was Sinful to Read Novels”, begins “To love these Books, and harmless Tea, / Has always been my foible”, immediately pulling us onside against the bibliophobes. Apparent artlessness has caused us to overlook all sorts of quiet innovators. The hymnist James Montgomery and Margaret Maxwell Inglis penned charmingly solemn verses that more than merit renewed attention from historians of religion and poetry alike—“a purer glow of feeling / Has bid me to rejoice”, writes Inglis (“A Morning Sabbath Walk”). Among other achievements, Bean Torra Dhamh, marketed as The Religious Poetess of Badenoch, produced unconventional hymns with strong social commentary, as evidenced in “Beachd Gràis air an t-Saoghal” (“The Vantage Point of Grace”).

Framed within the category of Scottish literature, these and other writers ought to be considered in the overlapping contexts of British, Irish, European, North American, and other literatures. They are at once Scots and citizens of the world, inhabiting multiple literary languages at once—Scots, English, and Gaelic, above all, as well as French, German, Italian, and Latin, among others. The pseudo-ancient Ossian poems “translated” into modern English prose by James Macpherson became a worldwide phenomenon amid a broader Celtomania that thrived in the second half of the eighteenth century and beyond—readers as diverse as Thomas Jefferson and Napoleon Bonaparte were avid fans. Reading Macpherson’s prose poems anew alongside contemporary Gaelic verse, as well as Scots and English imitations, reveals new things about the ebb and flow of literary culture across the Lowlands, Highlands, and Islands—indeed, the entire world.

Anthologies have long platformed the traditional “big six” male Gaelic poets of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, led by the colossally talented Alastair mac Mhaighstir Alastair (Alexander MacDonald). But non-Gaelic readers and scholars should become more aware of the genius of the alternative big six of female Gaelic writers, Cairistìona NicFhearghais (Christiana Fergusson) among them. Indeed, hundreds of poets, balladists, and songwriters born or raised in Scotland throughout the long eighteenth century need to find new readerships. Their time has come.

Featured image by Connor Mollison via Unsplash (public domain)

February 11, 2023

New perspectives on the American Civil War [reading list]

![New perspectives on the Civil War [reading list] from Oxford University Press](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1676553762i/33947140.jpg)

New perspectives on the American Civil War [reading list]

The Civil War is without question one of the seminal moments in US history—fundamentally reshaping the political, social, racial, and economic structures of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. New research continues to illuminate how we understand both the events of the war and how its legacy continues to impact our modern world.

Here are seven titles that provide new perspectives on the war and its legacy.

1. Of AgeOf Age by Frances M. Clarke and Rebecca Jo Plant explores the enlistment of minors on both sides of the US civil war, and how Americans responded. This comprehensive study offers military, legal, medical, social, political, and cultural perspectives as well as demographic analysis of this important aspect of the war.

Underage enlistees comprised roughly 10% of the Union army and likely a similar proportion of Confederate forces. These boys served as musicians, messengers, and medical assistants, but they also took up arms and died in both armies.

An original and sweeping work, Of Age convincingly demonstrates why underage enlistment is such an important lens for understanding the history of children and youth and the transformative effects of the US Civil War.

2. Teacher, Preacher, Soldier, Spy

A former Methodist preacher and Missouri schoolteacher, John R. Kelso served as a Union Army foot soldier, cavalry officer, guerrilla fighter, and spy. Driven by an intense desire for revenge, Kelso was hailed as a hero by Union newspapers and called a monster by Confederate sympathizers. After the war, he served in the House of Representatives and was one of the first to call for the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson.

In Teacher, Preacher, Soldier Spy by Christopher Grasso, Kelso’s life story offers a unique vantage on dimensions of nineteenth-century American culture that are usually treated separately: religious revivalism and political anarchism; sex, divorce, and Civil War battles; freethinking and the Wild West.

3. A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood

A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood offers a new perspective on the crucial role the Bible played in the Civil War, what scriptures were most popular at the time, and the impact they had on military conflict in early American history.

In this insightful narrative author James P. Byrd explores the many ways the Bible was important to the Civil War. Soldiers fought with Bibles in hand, and both sides called the war just and sacred. With approximately 750,000 fatalities, the Civil War was the deadliest of the nation’s wars, leading many to turn to the Bible not just to fight but to deal with its inevitable trauma.

A fascinating overview of religious and military conflict, A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood draws on an astonishing array of sources to demonstrate the many ways that Americans enlisted the Bible in the nation’s bloodiest, and arguably most biblically-saturated conflict.

4. Rebels in the Making

Rebels in the Making is a narrative-driven history of how and why secession occurred. In this work, senior Civil War historian William L. Barney narrates the explosion of the sectional conflict into secession and civil war.

By examining the political developments in each of the fifteen slave states and how they culminated in secession, Rebels in the Making seeks to bring together the economic, social, and political circumstances affecting the southern states for a unique and comprehensive understanding of a pivotal point in American history.

Barney draws together the voices of planters, non-slaveholders, women, the enslaved, journalists, and politicians. This is the definitive study of the seminal moment in Southern history that culminated in the Civil War.

5. Happy Dreams of Liberty

In 1856, when Samuel Townsend died on his Alabama plantation he left his estate to his five sons, four daughters, and two nieces—all of them his slaves. Happy Dreams of Liberty is the poignant, multi-generational saga of a mixed-race family in the US West and South from the antebellum period through the rise of Jim Crow.

In this deeply researched, movingly narrated portrait of the extended Townsend family, R. Isabela Morales reconstructs the migration of this mixed-race family across the American West and South over the second half of the nineteenth century.

Happy Dreams of Liberty draws from hundreds of unpublished letters to narrate an intimate history of one family’s experiences in slavery and freedom, and addresses changing societal perceptions of mixed-race individuals from the fluidity of the antebellum period through the hardening racial lines of the early twentieth century.

6. Only the Clothes on Her Back

What can dresses, bedlinens, waistcoats, pantaloons, shoes, and kerchiefs tell us about the legal status of the least powerful members of American society? Only the Clothes on Her Back raises this question through its unique examination of ordinary women and men’s economic and legal status in American history through their clothing.

Author Laura F. Edwards, these textiles tell a revealing story of ordinary people and how they made use of their material goods’ economic and legal value in the period between the Revolution and the Civil War. The work uncovers forgotten practices, nuanced laws around the valuation of textiles, and how they affected the new republic’s economy and governing institutions.

Based on painstaking archival research from fifteen states, Only the Clothes on Her Back reconstructs this hidden history of power in antebellum America, tracing it from the governing order of the early republic in which textiles’ legal principles flourished to the textiles’ legal downfall in the mid-nineteenth century when they were crowded out by the rising power of rights.

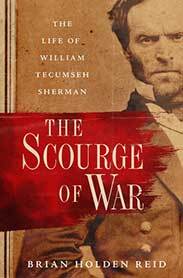

7. The Scourge of War

In The Scourge of War, preeminent military historian Brian Holden Reid offers a deeply researched life and times account of William Tecumseh Sherman, one of the best-known generals in the Civil War.

The book seeks to foster an understanding of Sherman, examining various key points in his life, from his childhood and education, to his business ventures in California, his antebellum leadership of a military college in Louisiana, and much more. The Scourge of War shows how unlikely his exceptional Civil War career would seem and demonstrates how crucial his family was to his professional path.

A definitive biography of a preeminent military figure by a renowned military historian, The Scourge of War is a masterful account of Sherman’ life that fully recognizes his intellect, strategy, and actions during the Civil War.

February 10, 2023

How to define 2022 in words? Our experts take a look… (part one)

How to define 2022 in words? Our experts take a look… (part one)

Now the dust has settled on another eventful year, it’s time to look back on some of the words that characterised 2022.

In December, we announced goblin mode as our Word of the Year for 2022, decided by public vote for the first time ever. A type of behaviour which is unapologetically self-indulgent, lazy, slovenly, or greedy, typically in a way that rejects social norms or expectations, goblin mode captured imaginations globally, with Stephen King joining in on Twitter, a discussion on the Late Late Show with James Corden, and online conversations spanning Europe, Asia, and America. While the lifting of pandemic restrictions was a relief for many, for some people, the social pressures like going out and returning to the office that came along with it were less welcome, and the idea of goblin mode captured a desire to escape those pressures as society returned to a new and different “normal.”

But when our experts analysed our corpus of 19 billion words, as well as finding candidates for the 2023 Word of the Year, they also looked at trends in how certain words were used at different points throughout the year.

Over this series of articles, we will take a month-by-month look at the words—excluding the three candidates for Word of the Year: goblin mode, metaverse, and #IStandWith—that captured a moment and saw peaks in usage in 2022.

From existing words that surged in popularity, like booster and queue, to brand-new words, such as Platty Joobs, and others making a comeback (did you know the word partygate was first used in the 1990s?), the language we use can tell us a lot about the last 12 months, the issues that have resonated, and the experiences we have shared.

JanuaryCast your mind back to this time last year and it was COVID-19 vaccinations that dominated the headlines. Our Word of the Year for 2021 was vax, and this conversation rumbled on into the New Year, with healthcare at the forefront of our minds in the wake of the pandemic and continuing to shape the language we use.

With that in mind, our experts have chosen booster as the word that best represents January 2022.

By no means a new word, booster was first recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) in 1890, with the sense “a dose or injection of a substance that increases or prolongs the effectiveness of an earlier dose or injection” first recorded in 1950.

It experienced a spike in frequency in December 2021 and January 2022 and was used more than 12 times more frequently in January 2022 than the same time the previous year.

Unsurprisingly, this increase in usage was caused by the push to ensure people across the world had received a booster jab of the COVID-19 vaccine. We can see this from looking at the other words used near booster. In January 2021, these showed the variety of its uses: morale booster and rocket booster for instance, alongside vaccine-related terms such as booster dose. In January 2022, however, while other uses were still prevalent, they were overwhelmed by vaccine-related terms, such as receive a booster, eligible for a booster, booster programme, and many others.

FebruaryFrom a well-known word that exploded in use to a hardly-known word bursting back onto the scene, our word for February is monobob.

Monobob is the first-ever female-only Winter Olympic sport, introduced at the Winter Olympics last year in Beijing. It is a solo version of bobsleigh, and it has significantly increased women’s participation in the sport.

Usage of the term monobob can be dated back to at least the 1930s in reference to a one-person bobsleigh. A dramatic entry in The Daily Telegraph on 18th January 1935 commented:

“The mishap occurred at a turn. Mr. Dugdale was on a mono-bob and it was noticed that he took the turn wrongly. His bob swung rapidly from side to side and he was thrown off.”

But the inaugural Olympic monobob competition led to a spike in usage of the term, with monobob used almost 12 times as much in February 2022 than February 2021.

The term monobob was used all around the world, but we saw two nations adopt the term more than others: Canada and Jamaica. The spike in Jamaican usage reflects the popularity of bobsled sports on the island nation: the unexpected entry of a Jamaican team in the 1988 Winter Olympics inspired the 1993 film Cool Runnings. Over 30 years later, Jamaica remains one of only three Caribbean nations to send bobsled teams regularly to the Winter Olympics, qualifying for a record three competitions last year, and sending Jazmine Fenlator-Victorian to compete in the new monobob event. The increase in Canadian usage might reflect the fact that Canada’s Christine de Bruin took Bronze in Bejing, coming behind US gold and silver medallists in the new event.

MarchFollowing the country’s invasion by Russian forces at the end of previous month, the word for March unsurprisingly was Ukraine.

The word Ukraine was used over 75 times more frequently in March 2022 than the previous year, and over 5.5 times more frequently in March 2022 than February 2022.

There is no denying that this spike in usage was due to the invasion, as shown by a number of other words experiencing an uplift in usage, relating both to the situation—invasion, invade, bombardment, besieged, unprovoked, and war-torn—and the international reaction—humanitarian, sanction, and oligarch.

In the past, the name Ukraine was frequently used in English with the definite article—the Ukraine—but this usage decreased after the country gained independence in 1991 after the dissolution of the former Soviet Union. Usage of the Ukraine, in proportion to overall uses of Ukraine, dropped further from March last year as the media and the public took conscious action to avoid using Russo-centric language to describe the region—a trend also seen with the media (for the most part) referring to the capital using the Ukrainian Kyiv rather than the Russian Kiev.

Coming soonThat’s all for this first instalment of the year in words. Keep an eye on the blog as we explore the rest of 2022 in words, including partygate, monkeypox, and more…

February 8, 2023

The murky beginning of the verb begin

The murky beginning of the verb begin

This is an unfinished story of the word begin. A look at the numerous papers devoted to the etymology of begin and at what dictionaries say about this subject creates the impression that as time goes on, we know less and less about our verb. The first volume of The Oxford English Dictionary was published in 1884. Though James A. H. Murray, the OED’s editor, realized that begin is an opaque word, he risked writing a detailed entry and suggested a solution. Most of the later reference works stress the verb’s opaqueness. Such is perhaps the true path of all dependable scholarship: don’t say anything unless you are sure, don’t be sure of anything unless all the facts are known, and remember that all the facts will never be discovered. This is a safe but sad approach.

As far as begin is concerned,two circumstances immediately alert the historical linguist to the trouble ahead. First, we notice that though the verb sounds almost the same and means the same in most of the Germanic languages, it never occurs without a prefix, and the prefixes vary. For example, the Old English for “begin” was on-ginnan (the most common form) and ā-ginnan (ā designates “long a,” as in Modern Engl. spa). Beginnan occurred in Old English very rarely. The verb’s cognate in fourth-century Gothic was du-ginnan. In Old High German, biginnan and inginnan turned up. The second problem concerns two n’s in the root –ginn. Double consonants (they are called geminates) were extremely rare in the oldest form of Germanic. When they occurred, they were either expressive or the result of assimilation. (An example of assimilation: Latin illegalis from inlegalis “illegal.”) It seems that “in the beginning,” the root ginn– was gin- with some other consonant after it. What was that consonant? Another n? What was its function?

The great pochin, with Lenin bringing up the rear.

The great pochin, with Lenin bringing up the rear.(By Alexey Savelyev, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

All attempts to understand the origin of begin turn around the mysterious meaning of –gin. About a dozen interpretations exist, and this multitude of opinions does not augur well for the sought-for answer. Let me “begin” at the end. According to a conjecture by the famous Norwegian philologist Sophus Bugge (1833-1907), begin has a good Slavic cognate. Allegedly, Russian po-chin “beginning” (stress on the second syllable; chin from kin; po– is a prefix) contains the root that provides the desired semantic fit. But non-Germanic (here, Slavic) k does not normally correspond to Germanic g. Bugge’s suggestion has been neither forgotten nor endorsed in modern scholarship, and at the end of this post, we will see that the idea behind it is quite clever, even though it hardly provides a solution to our etymology. One wonders: Is it possible that Germanic –gin developed from –hin? If it did, the matter will be perfect.

Slavic linguists are not in a hurry to endorse the –kin ~ -gin idea, but it occasionally appears in our reference books. (At one time, all Soviet citizens knew the word pochin, because Saturday, 1 May 1920, witnessed the first display of voluntary (?) enthusiasm: people decided to spend a free day doing community service: removing trash, and so on. Lenin participated in the activity. Pictures of him carrying a log were ubiquitous, and so was his phrase velikii pochin “a great initiative.” Later, pochin became a buzzword, and subbotniks [the Russian for Saturday is subbóta, that is, Sabbath] became obligatorily voluntary.)

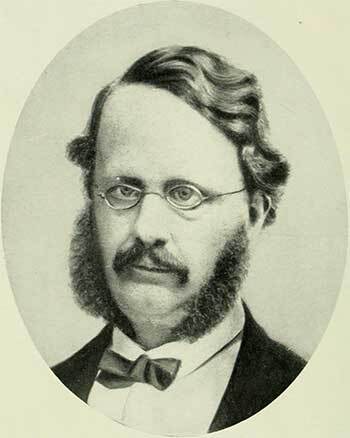

Sophus Bugge, Norwegian philologist.

Sophus Bugge, Norwegian philologist.(Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

To return to Germanic g from h. Latin prae-hen-d-ere “to seize” (compare English reprehensible) looks like a fairly good phonetic match, and the senses (“begin” versus “seize”) are not incompatible. A Sanskrit verb meaning “to drive on” perhaps belongs here too. A year ago, on 19 and 26 January 2022, I discussed the origin of the verbs hear and see and attempted to show how hard it is to reconstruct the earliest form and sense of such basic words. The same holds for begin.

According to the usual assumption, the sought-for initial sense of such words was absolutely tangible, concrete (“to seize,” “to touch,” “to follow,” and the like). But begin is a rather abstract concept. Only in Albanian, a verb meaning “to begin” and sounding like –gin– has been found. This precious find leads nowhere. Should we assume that both Albanian and Germanic borrowed their verb from some unknown, pre-Indo-European substrate language? Naturally, this idea occurred to some etymologists, but it is another version of the painfully familiar verdict “origin unknown.” What is that mysterious pre-Indo-European language? Where was it spoken? What did the word that interests us mean in it?

An old hypothesis, favored by JamesA. H. Murray, connects –gin– with the root of the verb that has become Modern English yawn (that is, to “open widely”). The root of that verb had two variants: one with a short vowel (gin) and one with a long one (gīn). The name of the ginnungagap of Scandinavian mythology, the void in which the world was created (thus, a vague analog of our black hole), reminds us of that verb. Murray wrote that the transition of sense from “open up” to “begin” is a common one and cited to open speech, to open fire, and to open up negotiations. Indeed, opening remarks are “beginning remarks.” In 1932, that is, half-a century after Murray, Henry Cecil Wyld, in his excellent The Universal Dictionary of the English Language, half-heartedly endorsed Murray’s reconstruction but followed Friedrich Kluge, the main authority on German etymology, and referred to Bugge’s Slavic cognate.

Elmar Seebold, the latest editor of Kluge’s dictionary, in the entry on German beginnen, cited German an–packen and an-fassen “to begin,” in which the root means “to seize.” Also, Latin in-cipere “to begin” (which left its trace in English incipient) is related to a verb of seizing (capio). Seebold compared beginnen with Latin pre-hend-ere “to seize, grasp” (English speakers recognize it from prehensile, and comprehend). This is an acceptable analogy. As a parallel, I may refer to Icelandic byrja “to begin,” which seems to have developed from the sense “to raise.” Seizing, raising, lifting an object from the ground looks like a feasible starting point in the development of the more abstract sense “to begin.”

The beginning or the end?

The beginning or the end?(By A R on Unsplash, public domain)

A certain mystery surrounds the idea of beginning. In quite a few cases, “beginning” is indistinguishable from “end.” Indeed, if messengers are sent to the four ends of the town, those are ends only if one looks at them from the center, but, from the point of view of the person entering the town, the “ends” are the beginnings. I am returning to Bugge. The root gin– bears a strong similarity to the root kon– in Russian kon-ets, related to the aforementioned po-chin, but this fact sheds no light on the origin of the root.

Slavic kon– is phonetically incompatible with Germanic –gin, unless there was some migratory word that traveled from language to language and meant something like “an outer point.” Such fantasies are not productive, but one thing is clear. The word that has come down to us as begin must have referred to some movement. Hence the multitude of prefixes: the movement could be toward or around, or away from an object. “Open” versus “close”? “Seize” versus “let go”? The words related to Icelandic byrja display an amazing multitude of meanings. Begin is much less colorful. It does not seem to go back to Indo-European, but the impulse behind its creation may have been the same as witnessed in the history of byrja.

Featured image via Hippo PX (CC0 – public domain)

February 7, 2023

Is Le Fanu’s Uncle Silas an Irish novel?

Is Le Fanu’s Uncle Silas an Irish novel?

When Sheridan Le Fanu’s Uncle Silas appeared in 1864, its author was best known as the proprietor of the Dublin University Magazine (DUM) and a writer of Irish historical novels. Yet, as advised by his publisher, Richard Bentley, Le Fanu had produced a work of fiction situated not in the Irish past but the English present. Uncle Silas, then, offers a strange mix of Irish concerns—not least a past that will not go away—with English people and places. But what do the novel’s Derbyshire locations and English characters have to do with the Ireland in which Le Fanu lived and worked?

Among Le Fanu’s earliest writing is “Passages in the Secret History of an Irish Countess”, one of a series of linked stories published in the DUM between 1838 and 1840. It contains the outline of Uncle Silas’s plot—a brother suspected of murder, a curious will, a niece in peril, an evil Frenchwoman—but it is set in Ireland, with houses located in Cork and Galway.

The DUM, where that earlier story appeared, brings into view the particular Irish context from which Uncle Silas emerged. The magazine occupied a curious cultural space in pre-Famine Ireland. Its overall tone was gloomy and pessimistic, expressive of failed Tory hopes in the face of Whig reforms. Yet even as it decried moves towards weakening of the Union and reform of the Church of Ireland, the DUM published original Irish fiction and poetry by authors with diverse political opinions. Writers including William Carleton, James Clarence Mangan, and Le Fanu himself could move between the DUM and the culturally nationalist Young Ireland publication, the Nation. Ireland’s Great Famine (1845–1852) and the efforts at revolution that swept Europe in 1848—including a Young Ireland rebellion—caused divisions to harden. A moment of potential cultural innovation closed down, not to reopen until the decades after Le Fanu’s death with the Literary Revival spearheaded by W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory in in the 1880s and 1890s.

Long before the appearance of Uncle Silas in 1864, Ireland had begun to exhaust British audiences, as suggested in 1848 when Henry Colburn wrote to Anthony Trollope to advise him that “readers do not like novels on Irish subjects as well as on others.” Famine fatigue, it would seem, had literary repercussions. Harriet Martineau spelled it out in 1853 when she observed that “The world is weary of the subject of Ireland; and, above all the rest, the English reading world is weary of it. The mere name brings up images of men in long coats and women in long cloaks; of mud cabins and potatoes; the conacre, the middlemen and the priest; the faction fight, and the funeral howl.” Martineau did not doubt the suffering experienced during the Famine but expressed a kind of painful indifference: “The sadness of the subject has in late years increased the weariness.” Irish difficulties, she said, were “too real and practical to be an intellectual exercise or a pastime—to serve as knowledge or excitement. Something ought to be done for Ireland; and, to readers by the fireside, it is too bewildering to say what.”

“Elizabeth Bowen, living in London at the height of the Blitz… did not hesitate to describe it as ‘an Irish story transposed to an English setting.’”

So, when Le Fanu got Uncle Silas into the hands of his fireside readers, they found no references to the Ireland of the day. And yet when Elizabeth Bowen, living in London at the height of the Blitz, wrote an introduction to the novel in 1947 she did not hesitate to describe it as “an Irish story transposed to an English setting.” She found her evidence in a social milieu redolent of the author’s Anglo-Irish background: “the hermetic solitude and the autocracy of the great country house, the demonic power of the family myth, fatalism, feudalism and the ‘ascendency’ outlook”, all “accepted facts of life for the race of hybrids from which Le Fanu sprang.” “For the psychological background of Uncle Silas”, she wrote, “it was necessary for him to invent nothing.”

But it is not only psychology that can unlock the Irish resonances of Uncle Silas. A more materially grounded understanding of the lines of connection between Uncle Silas and the politics of Le Fanu’s day can be found in a sub-plot concerning the cutting of the trees on the estate of the endangered heiress, Maud. Her wicked uncle Silas has been “cutting down and selling the timber, and the oak-bark, and burning the willows, and other trees that are turned into charcoal.” The environmental consequences and legal wrongs of extraction are explained: “It is all waste.” Le Fanu draws on a resonant arboreal language that stretches back to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Irish-language poetry. The eighteenth-century elegy Cill Cais asks “Cad a dhéanfaimid feasta gan adhmad? / Tá deireadh na gcoillte ar lár … What shall we do for timber? / The last of the woods are down”. Later, in Maria Edgeworth’s The Absentee (1812), the Anglo-Irish Lord Colambre pinpoints the link between political and environmental responsibility when he informs his mother of the costs of her London lifestyle: “For a single season … at the expense of a great part of your timber, the growth of a century – swallowed in the entertainments of one winter in London! Our hills to be bare for another half century to come!”

With a reputation for having influenced both Charlotte Bronte and James Joyce, Le Fanu’s writing can be seen to encompass cultures, times, and places. Charlotte Bronte read his “Chapter in a History of a Tyrone Family” (in which an estranged and incarcerated wife lives on the upper floors of a Gothic mansion) in the October 1839 issue of the Dublin University Magazine and may have had it in mind when she gave us her own version of the “spouse in the house” plot in Jane Eyre (1847). Meanwhile references to Le Fanu’s Dublin novel, The House by the Churchyard (1863), resonate throughout Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939). In the postmodernist masterpiece, a description of the graveyard of a “creepered” Church of Ireland building makes play with Le Fanu’s name in the description of “the ghastcold tombshape of the quick foregone on the loftleaved elm Lefanunian abovemansioned”. A reference to “Unkel Silanse” elsewhere in the Wake expresses an essential secrecy that remains central to any reading of this enigmatic novel.

Featured image by Yan Ming via Unsplash (public domain)

February 5, 2023

Do nouns have tense?

You may have seen the 2021 BBC story with the heading “Nirvana sued by the baby from Nevermind’s album cover.”

The 1991 album cover showed the then-baby nude and swimming toward a dollar bill on a fishhook. Not long ago, the thirty-ish grown-up baby sued the former members of Nirvana and the estate of Kurt Cobain, accusing them of child pornography and of causing him emotional damage. But the headlines make it sound like a baby is suing. CBS News tried for tortuously clarity, offering “Man shown as a baby on Nirvana’s Nevermind album appeals ruling in band’s favor.”

The clunkiness of both attempts is a reminder that English noun phrases have something called a “temporal interpretation.” That’s linguist-speak for how we understand their place in time relative to the tense of the verb. You can think of it as a time stamp on a noun phrase.

There is a robust academic literature on temporal nouns and some excellent articles, dissertation, and books by scholars such as Irene Heim, Murvet Enç, Renate Musan, and Judith Tonhauser, among others.

The basic point is that a noun can be understood as existing at a different time than the verb. For example, a tired mom might elbow her partner in the middle of the night and grumble, “It’s your turn to feed the baby.” The baby and the feeding are both in the present. But an adult showing old family photos might comment that “The baby in that picture is me.” The baby is in the past. And a pregnant mother-to-be would be likely to say that “The baby was kicking all day,” using baby rather than fetus or baby-to-be. The baby is in the not too distant future.

“A noun can be understood as existing at a different time than the verb.”

We often gloss over the alignment or misalignment of a noun’s time stamp with its predicate. If I say that “A student of mine was named to the board of Tesla,” it can be understood as referring to a current student or a former student. University students are not typically on corporate boards (even Elon Musk’s), so the likelihood is that I mean a former student. A listener gets that, even if I choose not to make things unambiguous by adding former.

Modifiers like former or current help to place a noun phrase in time, giving nuance: a current student, a former Governor, a sitting Senator, an erstwhile roommate, a past lover, a one-time contender, an old professor, the present administration, and so on.

Former baby sounds a bit odd, since babyhood is something that one naturally grows out of, like being a high school student. So, consider a sentence like “A high school student invented a new type of telescope.” The phrase high school student suggests a temporality, so just a date will do. Adding former would confuse matters.

Other nouns have similar temporal limitations: Murvet Enç’s clever example “Every fugitive is now in jail” means that those who were formerly fugitives are now jailed, since fugitive implies flight. And nouns like captive and hostage can be used to refer to those who have been recently released or freed, though after a certain interval former seems necessary. “Every incumbent is running again” is fine, but with current added, we get redundancy.

Sometimes the mismatch of verb tense and noun temporal interpretation jumps out at us, like when a baby files a lawsuit. Sometimes it slips right by. The lesson here is to keep an eye on both the tense of verbs and the time stamp of nouns.

Featured image by Sonja Langford on Unsplash (public domain)

February 3, 2023

The everyday work of chaplains: hidden around the edges

The everyday work of chaplains: hidden around the edges

From 1947 to 1979, people who died at Metropolitan State Hospital or the Fernald School were buried at Metfern Cemetery in Waltham, Massachusetts. Many lived with mental and/or developmental disabilities before they died. My family and I stumbled across this cemetery recently while walking in Beaver Brook Reservation. We were drawn to the flat gravestones labeled P or C for Protestant and Catholic. A Buddha statue—clearly placed there more recently—looks down from the small hill where people are buried. As my kids wondered about the people buried here, I thought about those who did the burying—the chaplains at Metropolitan State Hospital and the Fernald School.

I know about these chaplains through research I conducted for my latest book, Spiritual Care: the Everyday Work of Chaplains. I saw the names of Catholic and Protestant chaplains who worked in these institutions in the archives I visited during the research. I also met an older priest who worked at the Fernald before it closed in 2015. “You can pick the building up and move it, but we own the land” is what the priest remembered being told as he tried to figure out how to close the chapel as its last day approached. “We examined picking the building up, but the way it was built, you couldn’t move it. It would have collapsed. So that was just abandoned eventually and torn down.”

Much like this chapel, chaplains—in Boston and across the country—tend to fly below the radar with little attention outside of emergency situations. While the public profiles of chaplains increased during the early months of the pandemic, they have long been present in the military, healthcare organizations, prisons, colleges and universities, and a range of other settings. In my research, I’ve found that chaplains play an important—if overlooked role—in local religious ecologies particularly as they serve more and more people who are not religiously affiliated or members of local congregations. They support people around end-of-life issues, through transitions, and in moments of intense vulnerability. While that work is rarely in public view, it is and has long been an important part of the care religious leaders provide across the country.

“Chaplains play an important—if overlooked role—in local religious ecologies particularly as they serve more and more people who are not religiously affiliated.”

Historically, most chaplains were local clergy who worked as chaplains on the side. Before 1945, most chaplains in Boston were Protestant or Catholic men who served hospitals, prisons, and colleges and universities. The Boston Fire Department welcomed its first chaplain in 1906 and many chaplains were active in military and veteran contexts in Boston after World War II. Father Richard Cushing, the first Boston-born Catholic Archbishop, built workmen’s chapels at Logan Airport (Our Lady of the Airways), South Station (Our Lady of the Railways), the port (Our Lady of Good Voyages), and other settings that were also tended to by chaplains.

With time, more full-time positions for chaplains emerged in healthcare organizations including hospice, the military, prisons, and colleges and universities. As fewer people are religiously affiliated and traditional congregations close, more theological schools have started degrees specifically for those interested in chaplaincy and spiritual care. Chaplains are diverse religiously, racially, and in terms of gender and sexuality today. In Boston, chaplains serve staff and patients in major medical centers as well as those who are unhoused, who are grieving the loss of pets, and who are working with victims of violence.

Much of what chaplains do is hold space for people; “there is a tenderness and a kind of noticing that chaplains do,” one who works in healthcare reflected, “that can make a world of difference for a patient moving through the chaotic and fast-paced medical center…. that stillness and presence of mind and soul is really… important in this setting.” She continued telling me, “There are liminal moments for patients who are facing a crisis of some sort and family members and having a person—and if it’s me, having the opportunity to be the person—who creates a bit of a holding space and can validate what a person is feeling and give them some sense of hope or stability in the midst of chaotic times… that is an extremely valuable contribution.” Chaplains see themselves making a difference not by answers they share about life’s difficult questions but in the spaces they name and help people hold. It is in these spaces, most believe, people can come to their own answers eventually.

“Chaplains see themselves making a difference not by answers they share about life’s difficult questions but in the spaces they name and help people hold.”

People who are religious and those who are not both engage with chaplains. Chaplaincy is a service accessed broadly by a wide range of people according to a national survey we conducted in March 2022 at Brandeis in partnership with the polling firm Gallup. The survey found that one quarter of Americans have had contact with a chaplain, the majority through healthcare settings including hospitals, hospices, and palliative care.

It is in end-of-life situations that chaplains are most frequently present—helping people prepare to die, being present as they die, caring for loved ones after a death, and helping to manage death for institutions. “We were a bridge,” one chaplain told me reflecting on a recent death, sometimes to notions of God or the holy and others time to bigger questions of meaning and purpose that have guided people on their journeys. While I do not know how many of those buried at Metfern Cemetery were tended to by chaplains—in life and in death—some were and their names, like so much else related to chaplains’ work, live on in institutional records and in the stories I tell in my book.

Featured image used with permission from MetFern Cemetery.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers