Oxford University Press's Blog, page 60

December 22, 2022

What do we know about the effect of gut microbiome in diet and exercise on brain health?

The gastrointestinal tract is one of the most densely populated microbial habitats on earth, containing more cells than those that make up the human body and 150 times the number of genes than exist within the human genome. An unhealthy gut environment is characterized by a reduction in the diversity of bacteria and increased gut barrier permeability, leading to the release of toxic metabolites into the blood stream that negatively impact the brain. Lifestyle factors such as healthy diet and exercise improve the diversity and function of the gut microbiome, which may represent a therapeutic target for lowering dementia risk.

How are exercise and diet thought to impact the brain via the gut microbiome?Diets high in saturated fats and simple sugars are associated with reduced microbiome diversity and increased intestinal permeability and inflammation. By contrast, diets high in fruits and vegetables, legumes, nuts, and fish are associated with improved gut microbiome diversity, intestinal health, and a reduction in inflammation. Potential mechanisms include metabolites such as short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which help to maintain the integrity of the gut barrier and exhibit neuroprotective properties.

Aerobic exercise has been shown to improve microbial diversity and intestinal barrier integrity, leading to a reduction in systemic and neural inflammation. Potential mechanisms include increases in SCFAS and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). The effects of diet and exercise on brain health may be mediated by changes to the gut microbiome, however, very few studies have examined these relationships in a clinical setting.

What evidence is out there?We conducted a literature review of diet and exercise interventions, which included both microbiome and cognitive outcomes. We found 22 completed trials, almost all which were rodent studies, mostly utilizing detrimental-type diets. Of the studies that investigated beneficial diets, most used single nutrient interventions such as fiber, PUFAs, and polyphenolic compounds. One diet intervention included older adults and studied the effects of a “Mediterranean” diet on gut microbiota and cognition. Very few exercise interventions were identified (n=3).

Review of the findingsDiet and exercise interventions consistently altered the gut microbiome. Detrimental diets led to impaired memory performance, which was associated with decreases in neurotrophic factors and increased local, systemic, and neural inflammation. On the contrary, beneficial diets and aerobic exercise resulted in improved memory and reductions in age- and AD-related impairments, and were associated with increased SCFAs, neurotrophic factors, and reductions in local, systemic, and neural inflammation.

Following high adherence to a “Mediterranean” diet in older adults, altered microbiota were associated with changes in overall cognition. In rodents, microbiota changes were found to precede cognitive improvements resulting from a high-fiber diet intervention and diet-associated cognitive improvements were reversed when rodents were administered antibiotics intended to disrupt gut microbiota. In a novel microbiota transplant design, mice who had their microbiome depleted with antibiotics were transplanted with fecal matter from mice fed a high fat diet or normal chow diet. The high-fat diet fecal transplant altered microbiome diversity and composition, increased permeability and inflammation, and lowered memory performance. These studies provide evidence for the mediating role of the microbiome, but are limited by heterogeneous rodent strains, mostly male rodents, narrow selection of cognitive tests, and lack of proper mediation analyses.

Areas requiring further investigationOur review of the trials and findings indicates three key research areas requiring further investigation:

1. Human trialsThe role of the microbiome in the effects of diet and exercise on cognition is emerging from pre-clinical trials, but the relevance to humans, especially in the context of dementia prevention is uncertain. There is a need for more human trials, in particular those that include at-risk older adults. Due to the frequent use of maze testing and fear conditioning paradigms to assess memory in rodents, little is known about other cognitive domains that can be differentially impaired in humans experiencing dementia.

2. Whole dietsThe effects of beneficial whole diets on microbiota and cognition are also underexplored. The general consensus is that the combined attributes of a diet are more important than individual components for brain health. Thus the effects of whole diets high in fruits vegetables, legumes, nuts, and fish on gut microbiota and cognition are recommended for future studies in this area.

3. Exercise type and intensityThe number of exercise trials in this area is limited and little is known about how exercise type and intensity influence gut-brain communication. For instance, the effects of resistance exercise, or high intensity aerobic exercise such as HIIT training. As multicomponent interventions including diet and exercise in older adults are increasingly common, it is of interest whether synergistic effects on the microbiome are present. Factorial designs comparing diet, exercise, and both combined are required.

In conclusion, the intervention literature supports the notion that the gut microbiome mediates diet and exercise effects on cognition. The evidence is mainly derived from rodent studies and there are several gaps in the research that require further investigation. There are numerous studies investigating the effects of diet and exercise on cognition in older adults, but lacking investigation into the microbiome. We encourage researchers working on these studies to attempt to include simple, cost-effective measures of microbiota composition, diversity, and function, and measure potential mediating factors such as SCFAs, BDNF, and local and systemic inflammation. This effort would help to elucidate the mechanisms by which lifestyle modification affects cognition and possibly help to better tailor interventions for dementia prevention in older adults.

December 19, 2022

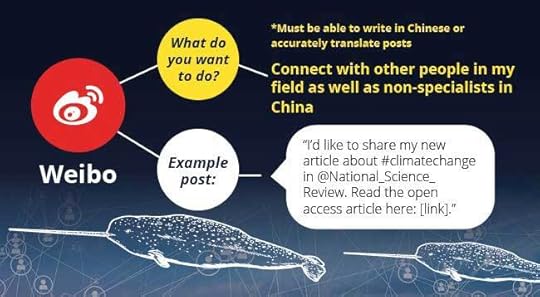

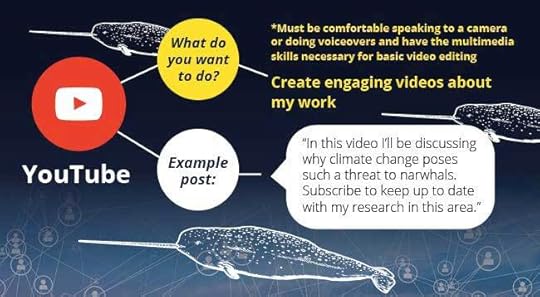

Social media at a glance: for academics

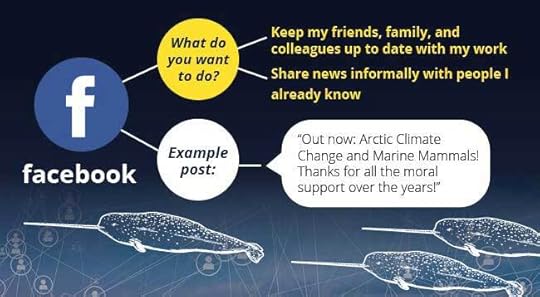

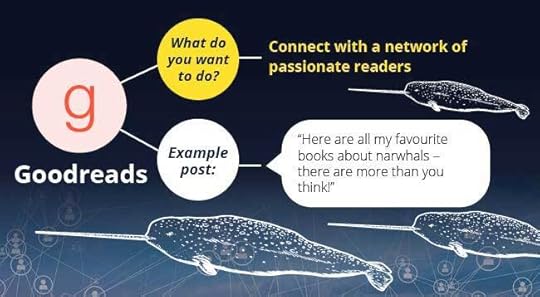

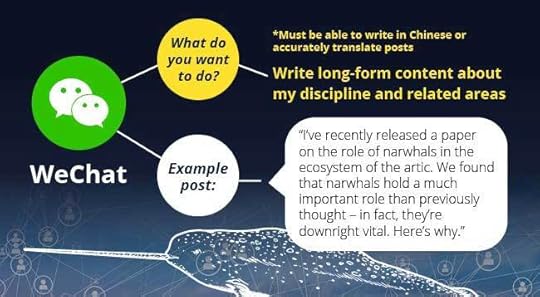

There are dozens of social media platforms, each with a distinct personality and purpose, so it can be difficult to know which social media platforms are the most useful for academics to engage with. That’s why we’ve put together this how-to guide to help you decide which social media platforms are the best fit for your goals as an academic—whether that’s engaging with fellow researchers in your subject area, promoting your latest research paper or monograph, or just celebrating your achievements with friends and family.

How to choose a social media platformNot sure which social media platform is the one you want to dedicate your time to? Use our “social media at a glance” guides for each of the main social media platforms to help you decide. Look at each guide and identify which platform best aligns with your goals. Check out the example post for some inspiration of the kind of content you could create and share on each social media platform.

FacebookGoodreadsInstagramLinkedInRedditTwitterWeChatWeiboYouTubeFacebook Goodreads

Goodreads Instagram

Instagram LinkedIn

LinkedIn Reddit

Reddit Twitter

Twitter WeChat

WeChat Weibo

Weibo YouTube

YouTube How to use social media to promote your work

How to use social media to promote your workSo, now you’ve chosen your social media platform. How should you best make use of it? Learn more about what’s expected of you on each platform, as well as information about how to use hashtags and a few example posts, in our more detailed Social Media Guide for Authors.

What are my other options for promoting my work?

Social media is not the only way to promote your work. If you don’t have the time to build up your own social media profile, why not approach your institution or alumni association about sharing your work on their accounts? If your research is relevant to current events, have you considered writing an opinion article to share your findings with a wider audience?

If you only have an hour or two to dedicate to promoting your latest article, chapter, or book, there are still things you can do. Check out our tips for promoting your work, with suggestions such as adding links to your email signature, recommending your book to your institutional librarian, or requesting a flyer with a free chapter or discount code.

Featured image by Austin Distel, via Unsplash, public domain

December 17, 2022

The cost of crises on human rights

With crises such as climate change and pandemics permanently on our minds, it seems a pertinent time to reflect on how these challenges impact on human rights. Specifically, it is essential to think about whether the way in which we are governed through these challenging time impacts on human rights.

International Human Rights Law 4th edition contains critical discussion by leading experts on international human rights. Its final section, aptly named “Challenges”, focuses in on the intersection between human rights and times of crises. With four excerpts from these final chapters, this blog post opens up the discussion around the impact of governing through times of strife.

PovertyA powerful justification for human rights in the anti-poverty agenda relates to the proposition that human rights define the same objective as pro-poor development, for which human development is a convenient proxy. From the capability perspective, both human development and human rights increase freedom. From the utilitarian perspective, both enhance human well-being. However, the similarity is diminished if development is defined merely in terms of growth in production and consumption of goods and services […]. Growth is desirable but not as an end in itself; it is a means towards various possible ends. If the end is the enrichment of the few at the expense of the many and of the planet, then it will not help the poor. If it is a means toward sustainable and equitable development, then it must be governed so as to reach that end. […]

Thus, the first step in clarifying in practical terms the meaning of poverty in the context of human rights is to note that pro-poor human development, like human rights, is a process that enables choices by all people to lead a life they value and, thus, enhances their well-being. Human rights are also about creating an environment in which people can develop their full potential and lead creative lives by, in the words of the [Universal Declaration of Human Rights], assuring “the dignity and worth of the human person” and promoting “social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom”. The ultimate objective of both human development and human rights is, therefore, well-being as understood in both fields. The greatest obstacle to those choices is poverty, which is both capability deprivation and a measure of the denial of human rights.

Stephen P Marks is the François-Xavier Bagnoud Professor of Health and Human Rights at the Harvard T H Chan School of Public Health, where he directs the Program on Human Rights in Development.

Read Chapter 30: Poverty in full →

PandemicsThe pandemic has exposed the fault lines of inequality and gaps in implementation of human rights in every state irrespective of its level of wealth and development. It has revealed systemic weaknesses in investment in health and social security systems. Its impacts, whether in relation to health effects and mortality or negative economic consequences, fall disproportionately on those who already face marginalization and discrimination. Restrictions that were imposed by states to contain the public health emergency have impacted the enjoyment of a range of human rights. Furthermore, several governments have used the pandemic as a pretext to severely curtail freedom of speech, persecute critics, and roll back social, environmental, or labour rights safeguards.

“The key challenge in ensuring preparedness for pandemics is the unwillingness of governments to address longer term problems which are less visible to electorates.”

There are numerous proposals on the table for reforms to global health governance to improve the international system for pandemic preparedness and response, including the adoption of a new treaty on pandemics. However, the main lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic is not that we need entirely new international obligations but better implementation of existing obligations. Any reform process needs to engage in far greater depth with the underlying factors that have resulted in decades of lack of prioritization and compliance with obligations, particularly those related to fulfilment of economic, social, and cultural rights. […] The key challenge in ensuring preparedness for pandemics is the unwillingness of governments to address longer term problems which are less visible to electorates. […]

The economic impacts of the pandemic are likely to be felt for many years and, for the human rights legal framework to offer meaningful protection, there has to be far greater scrutiny on how governments allocate resources. This requires a systemic focus on resources and structures which determine distribution of resources both at the national and international levels, such as taxation. Lawyers and NGOs have often shied away from this area as it requires greater interdisciplinary collaboration and engagement with economic models and questions of redistribution. The pandemic has brought this challenge strongly to the fore and the nature of the response will determine whether the international human rights legal framework continues to be perceived as relevant and useful.

Meghna Abraham is a human rights lawyer and consultant who has worked with NGOs in India, UK, and Switzerland.

Terrorism

Particularly in the long aftermath of 9/11, governments have increasingly resorted to vague and broad definitions of terrorism. While this may have been triggered partly by a desire to respond to an unspecific threat, all too often governments intended to target individuals or groups that do not deserve to be labelled as terrorist, such as political opposition groups, radical trade unions, vocal but non-violent separatist movements, indigenous peoples, religious minorities, or even human rights defenders. The global consensus about the imperative of combating terrorism was so compelling that authoritarian governments could get away with their repressive practices whenever they renamed their opponents as “terrorists.” […]

Governments have often departed from ordinary laws, normal procedures, or the fundamental rights of the individual when confronted with acts of terrorism or the threat of them. Since 9/11, unprecedented waves of special legislation or special powers have emerged all over the world, and practically all human rights have been under attack or ‘reconsideration’. While most human rights are not absolute but allow for some limitations to protect public security, in many cases governments have gone beyond these permissible limitations, resulting in human rights violations. […]

Even if the damage to human rights triggered by the terrorist acts of 9/11 was acknowledged and the process of repairs started, any new incidents of terrorism tend to cause the pendulum to swing back again. Even where important steps have been taken to depart from human-rights-hostile practices, those lessons learned are not necessarily permanent.

Martin Scheinin is British Academy Global Professor at the University of Oxford and part-time professor at the European University Institute in Florence.

Climate change

“Applying a human rights lens to climate impacts has helped national courts to hold governments to account for the ambition (or lack thereof) of climate actions.”

The breathtaking pace of developments at the intersections of climate change and human rights—across international human rights and climate change legal regimes as well as in national, regional, and increasingly international courts—has led to integration and mainstreaming of human rights approaches to climate impacts across regimes. It has also led to the understanding that compliance with the provisions of international climate change instruments does not necessarily guarantee compliance with human rights obligations, and that compliance with the latter might require states to take more stringent and ambitious climate actions directed at more ambitious global goals than those identified in climate change instruments.

The growing practice of applying a human rights lens to climate impacts has helped national courts to hold governments to account for the ambition (or lack thereof) of climate actions, thereby catalysing policy change that will likely have ripple effects across jurisdictions. While these are positive developments, it remains to be seen how an international climate change regime that favours national determination and contains limited avenues for the protection of substantive human rights can stabilize climate change at levels sufficient to protect human rights.

Lavanya Rajamani is a Professor of International Environmental Law at the Faculty of Law, University of Oxford, and a Yamani Fellow in Public International Law at St Peter’s College, Oxford.

If you would like to get involved in the discussion around human rights, visit @OUPLaw on Twitter for more posts during National Human Rights month.

Domestic violence: deconstructing the “gender paradigmâ€

Until well into the 1980s, the problem of domestic violence, often referred to as intimate partner violence, or IPV, was considered a private matter, rarely talked about in public spaces, and under-prosecuted by law enforcement. Since then, laws have been enacted to protect victims and hold perpetrators accountable, and society has taken the problem more seriously, as evidenced by the proliferation of news stories on the topic.

Earlier this year, it was the trial of the actor Johnny Depp that caught our attention. This time, surprisingly, we learned about violence perpetrated by the female partner in the relationship. Violence within their relationship appeared to be bilateral (wherein both disputants participate in abusive behavior). Despite all the conflicting evidence of abuse and a judicial finding of culpability, Depp’s partner, Amber Heard continues to portray herself as the primary victim. In some quarters, the court’s findings were seen as a miscarriage of justice, a step backward in our common efforts to end domestic violence. Among others, it was proof that allegations of domestic violence cannot be trusted, especially by women, who are inclined to lie. So, which side is right?

The only reason for such polarization in a case that otherwise should never have gotten such scrutiny, is because most people—and not just the average citizen but, sadly, most policy makers and other stakeholders—hold mistaken and distorted beliefs about IPV. This is what some call the “gender paradigm,†which the Depp-Heard case put into question. This set of assumptions views IPV as a gendered problem, of men using physical and psychological aggression to dominate their female partners, either to maintain “male privilege†or due to jealousy or unresolved mental health issues. It also regards IPV as a unitary phenomenon of chronic, usually life-threatening assaults rather than the complex, heterogenous problem that it is. Most people don’t realize that the lifetime prevalence of IPV is 47.3% for women and 44.2%. Moreover, lifetime rates of IPV among gender minorities are similar or higher to that of heterosexual couples. Bisexual men and women experience the highest rates of IPV, and almost 44% of lesbians and 26-50% of gay males experience IPV. Moreover, while data on transgender individuals is scant, current research finds transgender and gender nonconforming individuals are 1.7 times more likely to experience any form of IPV compared to cisgendered and over two and a half times more likely to experience physical and sexual IPV over 50% have experienced IPV. Sexual minority youth have rates of physical and sexual IPV victimization higher than cisgender, heterosexual youth.

“The most accurate, up-to-date, statistics available indicate that in the United States, the UK, and Canada, women and men perpetrate physical and psychological IPV at similar rates.”

How is this an issue of male privilege or a gendered problem when rates of IPV are similar across gender, sexual orientation, or gender identity? Given the pervasiveness of the gender paradigm, it should be of no surprise that the reflexive response to the Amber Heard verdict among many who have dedicated their lives to protect female survivors of domestic abuse was to say, “They don’t get it.†Or: “victims should always be believed.â€

Around the time that football player Ray Rice assaulted his wife in an elevator, an assault that was televised to millions, another NFL football player was stabbed in the neck with a screwdriver by his girlfriend, and almost no one heard about this incident. Most of us know some man, maybe even a family member, who has secretly been the target of abuse from a partner, who would be reluctant to share their experiences with anyone, much less initiate a call to the police. No surprise, therefore, that in some quarters the response to the Heard verdict has been to dismiss domestic violence as simply rich people arguing, and to regard all accusations as suspect and motivated by deceit. In other words, don’t believe women. Polarized reactions around domestic violence may now be akin to how our society has become politically divided in the broader sense.

Neither response is correct. The case of Johnny Depp and Amber Heard merely demonstrates that, indeed, women are capable of abusing their partners, and that like many men in denial, they often lie about it and attempt to portray themselves as victims. Although women are arrested at rates far less than men, the most accurate, up-to-date, statistics available indicate that in the United States, the UK, and Canada, women and men perpetrate physical and psychological IPV at similar rates, and that they are motivated for the same reasons—to control, out of frustration, to get revenge, and sometimes in self-defense. The research also finds that women and sexual minorities are far more likely to be sexually assaulted and, importantly, to incur the large majority of life-threatening injuries. It is also true that men, on the whole, due to cultural messaging requiring them to present a brave façade, are reluctant to identify as victims. It doesn’t help that when they do seek help, their concerns are typically dismissed or questioned. Similarly, sexual minorities face even greater obstacles such as heterosexist discrimination and are less likely to report IPV.

One may wonder, why is it such a big deal if a 6’2†guy is slapped by his 5’2†wife during a marital spat? Can’t he defend himself? If you put an average man in a boxing ring with an average woman, doesn’t the man “win†every time? The obvious problem with this analogy is that the settings and context in which couples argue, and sometimes come to blows, is far different. Most men are loathe to hit women, much less seriously injure them, due to codes of chivalry and the repercussions that would follow—not just the legal ones, but their diminished standing at home and in the community. While abusive men can instill greater fear of physical harm in their female victims, abusive women can, and do, instill in their male victims fear of being incarcerated, publicly humiliated, losing the children, and most of their assets in a divorce action. Furthermore, an abusive woman has the advantage of knowing that society is far more accepting of her behavior, and that she is far less likely to be arrested than a man for the same level of crime. Moreover, sexual minorities face additional fears. For example, gay couples involved in an IPV incident are often the same size and gender. Without the size and status differences, this often leaves law enforcement at a loss when trying to identify the primary or dominant aggressor, and unsurprisingly leads to more dual arrests. Sexual minorities also face a double dose of discrimination in terms of their sexual minority status and often fear reporting abuse will lead to their abusers “out†their sexuality or be treated poorly by law enforcement who rarely trained to respond effectively in such IPV incidents.

Still, if some domestic violence victims don’t get as seriously injured as their female counterparts, and often choose not to report assaults perpetrated against them, why should we care? Get to know the facts and you will know why. Without the same access to the peer-reviewed journals as university professors, the average person can look up the Partner Abuse State of Knowledge Project (PASK). In Gender and domestic violence: Contemporary legal practice and intervention reforms, the authors draw on the PASK findings, and other contemporary research sources, to explain why IPV is a human problem, not a gender problem, and why we should indeed care very much about male victims and female perpetrators. Here are some of the reasons:

Men, too, feel pain. A punch to the face may not hurt as much, but it still hurts, and an aggressive abuser can make up for their lesser size and strength by using weapons or assaulting their partners when they are vulnerable (e.g., intoxicated, asleep). About 20-25% of IPV homicide victims are male.All victims are citizens with legal rights, and those rights are violated when law enforcement officers make an arrest in cases involving exaggerated or fabricated charges. Even victims with the financial means with which to fight these cases face a legal system and juries predisposed to find them guilty, often because they do not fit our stereotype of what an IPV victim is. The average heterosexual male or sexual minority defendant is usually advised to take a plea deal, with or without jail time, and a conviction on their record that may prevent them from obtaining further employment or securing custody time with their children. A disproportionate percentage of these individuals are people of color.All victims, despite gender or sexual minority status, say that they are more impacted by psychological abuse, particularly when it is chronic and severe. The research indicates that women perpetrate serious, chronic psychological abuse as often as do men. Being called a “loser†in front of your children, or having your sexual performance ridiculed in front of your friends, is for male victims the equivalent of a woman being called a “slut,†and just as humiliating. Similarly, sexual minorities experience the stigma and share of not fitting into our heterosexist society, and often experience humiliation associated with internalized homophobia.Children who witness their mother physically or emotionally abuse their father are just as likely to perpetrate similar acts in their dating and adult intimate relationships as if they witnessed dad’s abuse towards mom. This is because of the principle of observational learning, which does not depend on size and strength.Even if one discounts the legal, health, and intergenerational consequences of the gender paradigm in IPV, one should be concerned with the implications for women’s safety. A primary risk factor for men’s abuse of their female partners is being a victim of abuse in that same relationship—in other words, when women assault their male partners, they put themselves, and their children, in greater danger.Reducing rates of domestic violence in our communities requires a mutual effort on the part of all stakeholders involved, and it must be based on research and best practices. Proceeding otherwise is to show contempt for civil rights, putting a political agenda ahead of the well-being of children and families.

The post Domestic violence: deconstructing the “gender paradigm†appeared first on OUPblog.

Domestic violence: deconstructing the “gender paradigm”

Until well into the 1980s, the problem of domestic violence, often referred to as intimate partner violence, or IPV, was considered a private matter, rarely talked about in public spaces, and under-prosecuted by law enforcement. Since then, laws have been enacted to protect victims and hold perpetrators accountable, and society has taken the problem more seriously, as evidenced by the proliferation of news stories on the topic.

Earlier this year, it was the trial of the actor Johnny Depp that caught our attention. This time, surprisingly, we learned about violence perpetrated by the female partner in the relationship. Violence within their relationship appeared to be bilateral (wherein both disputants participate in abusive behavior). Despite all the conflicting evidence of abuse and a judicial finding of culpability, Depp’s partner, Amber Heard continues to portray herself as the primary victim. In some quarters, the court’s findings were seen as a miscarriage of justice, a step backward in our common efforts to end domestic violence. Among others, it was proof that allegations of domestic violence cannot be trusted, especially by women, who are inclined to lie. So, which side is right?

The only reason for such polarization in a case that otherwise should never have gotten such scrutiny, is because most people—and not just the average citizen but, sadly, most policy makers and other stakeholders—hold mistaken and distorted beliefs about IPV. This is what some call the “gender paradigm,” which the Depp-Heard case put into question. This set of assumptions views IPV as a gendered problem, of men using physical and psychological aggression to dominate their female partners, either to maintain “male privilege” or due to jealousy or unresolved mental health issues. It also regards IPV as a unitary phenomenon of chronic, usually life-threatening assaults rather than the complex, heterogenous problem that it is. Most people don’t realize that the lifetime prevalence of IPV is 47.3% for women and 44.2%. Moreover, lifetime rates of IPV among gender minorities are similar or higher to that of heterosexual couples. Bisexual men and women experience the highest rates of IPV, and almost 44% of lesbians and 26-50% of gay males experience IPV. Moreover, while data on transgender individuals is scant, current research finds transgender and gender nonconforming individuals are 1.7 times more likely to experience any form of IPV compared to cisgendered and over two and a half times more likely to experience physical and sexual IPV over 50% have experienced IPV. Sexual minority youth have rates of physical and sexual IPV victimization higher than cisgender, heterosexual youth.

“The most accurate, up-to-date, statistics available indicate that in the United States, the UK, and Canada, women and men perpetrate physical and psychological IPV at similar rates.”

How is this an issue of male privilege or a gendered problem when rates of IPV are similar across gender, sexual orientation, or gender identity? Given the pervasiveness of the gender paradigm, it should be of no surprise that the reflexive response to the Amber Heard verdict among many who have dedicated their lives to protect female survivors of domestic abuse was to say, “They don’t get it.” Or: “victims should always be believed.”

Around the time that football player Ray Rice assaulted his wife in an elevator, an assault that was televised to millions, another NFL football player was stabbed in the neck with a screwdriver by his girlfriend, and almost no one heard about this incident. Most of us know some man, maybe even a family member, who has secretly been the target of abuse from a partner, who would be reluctant to share their experiences with anyone, much less initiate a call to the police. No surprise, therefore, that in some quarters the response to the Heard verdict has been to dismiss domestic violence as simply rich people arguing, and to regard all accusations as suspect and motivated by deceit. In other words, don’t believe women. Polarized reactions around domestic violence may now be akin to how our society has become politically divided in the broader sense.

Neither response is correct. The case of Johnny Depp and Amber Heard merely demonstrates that, indeed, women are capable of abusing their partners, and that like many men in denial, they often lie about it and attempt to portray themselves as victims. Although women are arrested at rates far less than men, the most accurate, up-to-date, statistics available indicate that in the United States, the UK, and Canada, women and men perpetrate physical and psychological IPV at similar rates, and that they are motivated for the same reasons—to control, out of frustration, to get revenge, and sometimes in self-defense. The research also finds that women and sexual minorities are far more likely to be sexually assaulted and, importantly, to incur the large majority of life-threatening injuries. It is also true that men, on the whole, due to cultural messaging requiring them to present a brave façade, are reluctant to identify as victims. It doesn’t help that when they do seek help, their concerns are typically dismissed or questioned. Similarly, sexual minorities face even greater obstacles such as heterosexist discrimination and are less likely to report IPV.

One may wonder, why is it such a big deal if a 6’2” guy is slapped by his 5’2” wife during a marital spat? Can’t he defend himself? If you put an average man in a boxing ring with an average woman, doesn’t the man “win” every time? The obvious problem with this analogy is that the settings and context in which couples argue, and sometimes come to blows, is far different. Most men are loathe to hit women, much less seriously injure them, due to codes of chivalry and the repercussions that would follow—not just the legal ones, but their diminished standing at home and in the community. While abusive men can instill greater fear of physical harm in their female victims, abusive women can, and do, instill in their male victims fear of being incarcerated, publicly humiliated, losing the children, and most of their assets in a divorce action. Furthermore, an abusive woman has the advantage of knowing that society is far more accepting of her behavior, and that she is far less likely to be arrested than a man for the same level of crime. Moreover, sexual minorities face additional fears. For example, gay couples involved in an IPV incident are often the same size and gender. Without the size and status differences, this often leaves law enforcement at a loss when trying to identify the primary or dominant aggressor, and unsurprisingly leads to more dual arrests. Sexual minorities also face a double dose of discrimination in terms of their sexual minority status and often fear reporting abuse will lead to their abusers “out” their sexuality or be treated poorly by law enforcement who rarely trained to respond effectively in such IPV incidents.

Still, if some domestic violence victims don’t get as seriously injured as their female counterparts, and often choose not to report assaults perpetrated against them, why should we care? Get to know the facts and you will know why. Without the same access to the peer-reviewed journals as university professors, the average person can look up the Partner Abuse State of Knowledge Project (PASK). In Gender and domestic violence: Contemporary legal practice and intervention reforms, the authors draw on the PASK findings, and other contemporary research sources, to explain why IPV is a human problem, not a gender problem, and why we should indeed care very much about male victims and female perpetrators. Here are some of the reasons:

Men, too, feel pain. A punch to the face may not hurt as much, but it still hurts, and an aggressive abuser can make up for their lesser size and strength by using weapons or assaulting their partners when they are vulnerable (e.g., intoxicated, asleep). About 20-25% of IPV homicide victims are male.All victims are citizens with legal rights, and those rights are violated when law enforcement officers make an arrest in cases involving exaggerated or fabricated charges. Even victims with the financial means with which to fight these cases face a legal system and juries predisposed to find them guilty, often because they do not fit our stereotype of what an IPV victim is. The average heterosexual male or sexual minority defendant is usually advised to take a plea deal, with or without jail time, and a conviction on their record that may prevent them from obtaining further employment or securing custody time with their children. A disproportionate percentage of these individuals are people of color.All victims, despite gender or sexual minority status, say that they are more impacted by psychological abuse, particularly when it is chronic and severe. The research indicates that women perpetrate serious, chronic psychological abuse as often as do men. Being called a “loser” in front of your children, or having your sexual performance ridiculed in front of your friends, is for male victims the equivalent of a woman being called a “slut,” and just as humiliating. Similarly, sexual minorities experience the stigma and share of not fitting into our heterosexist society, and often experience humiliation associated with internalized homophobia.Children who witness their mother physically or emotionally abuse their father are just as likely to perpetrate similar acts in their dating and adult intimate relationships as if they witnessed dad’s abuse towards mom. This is because of the principle of observational learning, which does not depend on size and strength.Even if one discounts the legal, health, and intergenerational consequences of the gender paradigm in IPV, one should be concerned with the implications for women’s safety. A primary risk factor for men’s abuse of their female partners is being a victim of abuse in that same relationship—in other words, when women assault their male partners, they put themselves, and their children, in greater danger.Reducing rates of domestic violence in our communities requires a mutual effort on the part of all stakeholders involved, and it must be based on research and best practices. Proceeding otherwise is to show contempt for civil rights, putting a political agenda ahead of the well-being of children and families.

December 16, 2022

A Winter Breviary: Q&A with poet Rebecca Gayle Howell

A Winter Breviary is a triptych of eco-carols with music by Reena Esmail and words by Rebecca Gayle Howell. We caught up with Rebecca to find out a bit more about the process of writing a carol text, the significance of the solstice, nature and wildlife in the story, and how she collaborated with the composer to create something that would speak to choirs of different traditions and faiths.

What is the setting of this poem?A Winter Breviary is a triptych of carols that tells the story of a person walking in the woods on solstice night. This pilgrim—she, he, they—searches for hope, the hope they cannot name, or hear or see. And still, they walk deeper and deeper into the dark.

Solstice night is the longest night of the year. Or, as John Donne put it, “the year’s midnight.” Its lightlessness stretches out past our assumptions. On such a night, a person might feel it will never not be night again, that day is done. But the truth is, for us to awaken again to spring’s glory, the day must come to us differently. And, so it does.

In writing A Winter Breviary, Reena Esmail and I both wanted to write an interfaith celebration of these cold and holy days, something that could offer choirs of different traditions an epiphany journey toward the divinity that surrounds us all.

Can you explain the title, “A Winter Breviary”, and what each of the movement subtitles, such as “Evensong & Raag Hamsadhwani” refer to?Time theory in Indian classical music suggests that raags (pitch frameworks) should be sung at specific times in the day. Similarly, in the Christian contemplative tradition, we find a sequence of prayers that are to be recited at specific times of day. (The latter are collected in liturgical books called breviaries.)

For more than a thousand years, across the world and often without knowing, these two spiritual traditions have met, together, in song. Both raags and canonical prayers offer a constancy that marks a life by the well-loved day; they both act as kind of clock for the soul. The story of A Winter Breviary is organized around three canonical night prayers: evensong, matins, and lauds. These same hours have corresponding raags, which organize the triptych’s music: Evensong & Raag Hamsadhwani; Matins & Raag Malkauns; Lauds & Raag Ahir Bhairav.

The image of a sparrow appears throughout the text at different moments. Can you explain the significance of this image?I am a writer, translator, and editor of place-based literature. I want to tell stories that value our membership in the natural world, in which people learn from an earthen intelligence larger than their own. When Reena and I began our collaboration on these carols, we started asking each other what it might be like to write a series of carols celebrating the rebirth of our Earth. This is how the idea of an “eco-carol” came to be.

In A Winter Breviary, our pilgrim is joined by a house sparrow on their journey. From the very beginning of the first carol, “We Look for You (Evensong – Raag Hamsadhwani),” it’s clear the sparrow is our pilgrim’s companion, yes, but also their guide. “She looks with me, / We look for You” she is undaunted, even as the woods close in all around.

“Winter is, Winter ends, So the true bird calls”

The house sparrow is the kind of bird that most of us would not even notice—her feathers are tree bark brown, her body smaller than a person’s palm. But in this story, she is the one who knows that the Earth continues to team and turn and so do we, if we just tune ourselves to it.

In the second carol, “The Year’s Midnight (Matins – Raag Malkauns),” it’s revealed that all the Earth rejoices, by simply being. Here, the beasts pray by doing what is most natural to them in winter, by sleeping. Here, the trees pray by standing, branches raised. As the song advances, the pilgrim asks, “Hush, hush / Can I hear them? / Can I hear what is not said?” The pilgrim’s little bird, she has no need for words. She was made to fly, and so she does not falter in her flight.

What is the message at the end of the poem?In the third carol, “The Unexpected Early Hour (Lauds – Raag Ahir Bhairav)” dawn breaks. We are rushed by bells of gratitude—“Praise be! Praise be!”—the spirit’s shock that light indeed arrives. And in the dawn, the substance of things hoped for are, surprisingly, seen: the darkness did not stop the river from flowing, it did not keep the fields from growing. The Earth’s hope and our place in it cannot be found, because it was not ever lost. Change itself is the gift.

I feel the cold wind leaving, gone

I feel the frost’s relief

My tracks in the snow can still be erased

In us, the sun believes.

Featured image by Caroline McFarland via Unsplash, public domain

December 14, 2022

Skin-deep: wrinkle, pimple, and mole

I have a hearty dislike for “cute†newspaper titles and yet constantly invent them for my posts. The temptation to produce a cheap but presumably memorable pun is stronger than my aversion to flashy journalism. Anyway, on 17 February 2021, I wrote a short blog post, titled “The skin of etymological teeth.†The post, which dealt with skin, hide, and leather, was inspired by a question from a reader. This time, though no one asked me about what happens on the skin, I decided to volunteer my services.

The story of wrinkleThe origin of wrinkle is full of unexpected turns and twists, but, as I have known for a long time, words tend to live up to their meaning. How could the history of wrinkle be straightforward? The word is old, that is, its history goes back to Old English. Dictionaries are reticent about its etymology. The problem is that the Old English past participle gewrinclod “winding†has numerous look-alikes but no obvious cognates. A short digression is required here. Etymology became a more or less dependable area of knowledge (as opposed to intelligent and unintelligent guessing) after the discovery of sound correspondences between and among languages, but language is a capricious mechanism, and every time dependable correspondences fail us, we are lost.

Long ago, a few excellent scholars introduced the concept of rime-words (rime stands for rhyme). I’ll mention only three names: Heinrich Schröder (a German), Francis A. Wood, and Leonard Bloomfield (Americans). It so happens that some words rhyme and also denote more or less the same thing, though their initial sounds do not match. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology offers no origin of wrinkle. In contrast, Skeat mentions Danish rynke and Swedish rynka (the same meaning), both of which once began with hr– (not wr-!). The German for wrinkle (noun) is Runzel. It, too, probably once began with hr-. And we may remember English crinkle “to make small wrinkles.†Old English crympan “to curl†is its next-door neighbor. As always, the mysterious “movable s†(s-mobile) is round the corner. The adjective scrimp “scanty,†a doublet of shrimp also refers to something small. (See the post “A scrumptious shrimp with a riddle†for 18 April 2012.)

A pumpkin by any other name would not smell as sweet.

A pumpkin by any other name would not smell as sweet.(Photo by Olivia Kulbida on Unsplash, public domain)

Are German Runzel and English wrinkle related? Friedrich Kluge believed that they are. Those who edited his German etymological dictionary were not so sure. Neither are the authors of English dictionaries. Our answer depends on the readiness (or the lack thereof!) to admit that close synonyms influence one another or that they even generate one another by varying or swapping their initial consonant groups: wr– ~ hr– ~ kr– ~ skr-. Such variants fit words of various emotional spheres. In Middle English, wrinkle meant not only “a fold†but also “winding†(in general). The past participle (ge)wrinclod has been glossed as “winding.†The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, to which I referred above, a manual derivative of the great OED, has a rather unexpected entry, namely wr-. It says that this consonant combination occurred initially in many words implying twisting or disruption, the earlier of which often have cognates in other Germanic languages.

Such cases have been explored in depth by linguists studying iconicity, that is, ties between sound and meaning. In this blog series, sound-imitative and sound symbolic words are mentioned in almost every post. Obviously, if you can wriggle, you can also “(h)riggle,†“kriggle,†“piggle-wiggle,†“skriggle,†and of course “niggle†and “squiggle†(the latter, allegedly, a blend of squirm and wriggle). Some students of iconicity isolate such initial groups and compare them to ancient prefixes. (I have little enthusiasm for this procedure.) Not improbably, language was once “iconic†in all its elements, but we are so far removed from that remote epoch that no definite conclusions are possible. Apparently, some languages (for instance, Semitic) lend themselves to this type of reconstruction better than others. On this note, we may say that wrinkle does have relatives but only by marriage, rather than by birth. Having satisfied ourselves with this dubious solution, we may go on to pimples.Â

The iconic pimple An iconic pimple.

An iconic pimple.(Photo by Anna Nekrashevich via Pexels, public domain)

Pimples are not only unpleasant: they are also iconic. The substance of what I am going to say was discussed very long ago in my two posts: “On pimps and faggots†and “On faggots and pimps†(6 June and 13 June 2007), so that I’ll be brief. (I have to repeat my plea to those who happen to read the posts years after their publication: don’t leave your comments there, for how can I know that they exist? Add your notes to the most recent post or at least call my attention to the relevant blog post!). The root of pimp refers to something small and insignificant. Pimp denoted (and perhaps still denotes) a youngster in a logging camp or in a mine. The closed vowel i refers to a diminutive size. A pimple is not insignificant but tiny (teeny-weeny). Perhaps you want to feed your child, so that the youngster may become big and fat. Then pamper the beloved offspring and demonstrate the fruit of your endeavors with due pomp. If the verb pimper had existed, it might have meant “to spoon-feed†or “to starve to death.†Pomp and pump also command respect: their root vowels evoke a picture of something big and significant (think of pumpkin). Pumpernickel, we are told, is a word of unknown etymology. I believe that the etymology is known but will bring no one any joy: you eat this food, distend your stomach, and produce a big pump(f).

A pimpernel. An extra letter has done it no harm.

A pimpernel. An extra letter has done it no harm.(Jan Buchholtz, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This, by the way, is not my fanciful idea. I hasten to protect myself, because researchers are afraid of only two things: of saying something novel (and thus becoming a target of the opponents’ abuse) and repeating something that is already known (and thus being ridiculed for offering a trivial idea). This etymology of pumpernickel is not mine, but it is not fully trivial, so that I hope to escape the vituperation from both sides. If you have no more important things to deal with, consider the plant name pimpernel. The Romance etymon was presumably piperīnella, whose root is Latin piper “pepper.†Whose caprice was responsible for inserting m into this root?

Mole: a victim of taboo?Before we wind up, let us not forget moles on the skin. Mole has a cognate not only in older German but also in fourth-century Gothic, where it glossed Greek rutīs. Thus, “wrinkle†(and, incidentally, “any physical defect!). The German verb with this root meant “to stain†and later “to soil.†Perhaps the original meaning of the Germanic noun was “blemish.†Numerous words beginning with m have been proposed as presumably shedding light on mole, but none is close enough to clinch the argument. The names of diseases often fall victim to taboo: people were afraid to call something dangerous by its name and invented innocent-sounding substitutes. Moles are usually brown or black. Did the dark color frighten the superstitious? Were the original moles only black? Quite often, such stains on the skin brought forth associations with the Devil’s mark, and before the conversion to Christianity perhaps with the mark of evil forces. Let us draw a curtain of charity (as Mark Twain put it) of this horror.

A mole, black and innocuous.

A mole, black and innocuous.(Pixabay, public domain)

Yes, and what about German Mal “stain†and English mole, an animal name? Both are partly obscure, but neither is related to mole “spot on the skin.†I wish I could refer to something “symbolic†to save the innocent animal from its dark habitat and to remove a stain from a list of German unsolved cases, but I cannot.

The Oxford Etymologist wishes you happy holidays and a less tempestuous year than the one we are leaving behind. See the next post on Wednesday 11 January 2023.

Featured image by Moe Magners via Pexels, public domain

The post  Skin-deep: wrinkle, pimple, and mole appeared first on OUPblog.

Skin-deep: wrinkle, pimple, and mole

I have a hearty dislike for “cute” newspaper titles and yet constantly invent them for my posts. The temptation to produce a cheap but presumably memorable pun is stronger than my aversion to flashy journalism. Anyway, on 17 February 2021, I wrote a short blog post, titled “The skin of etymological teeth.” The post, which dealt with skin, hide, and leather, was inspired by a question from a reader. This time, though no one asked me about what happens on the skin, I decided to volunteer my services.

The story of wrinkleThe origin of wrinkle is full of unexpected turns and twists, but, as I have known for a long time, words tend to live up to their meaning. How could the history of wrinkle be straightforward? The word is old, that is, its history goes back to Old English. Dictionaries are reticent about its etymology. The problem is that the Old English past participle gewrinclod “winding” has numerous look-alikes but no obvious cognates. A short digression is required here. Etymology became a more or less dependable area of knowledge (as opposed to intelligent and unintelligent guessing) after the discovery of sound correspondences between and among languages, but language is a capricious mechanism, and every time dependable correspondences fail us, we are lost.

Long ago, a few excellent scholars introduced the concept of rime-words (rime stands for rhyme). I’ll mention only three names: Heinrich Schröder (a German), Francis A. Wood, and Leonard Bloomfield (Americans). It so happens that some words rhyme and also denote more or less the same thing, though their initial sounds do not match. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology offers no origin of wrinkle. In contrast, Skeat mentions Danish rynke and Swedish rynka (the same meaning), both of which once began with hr– (not wr-!). The German for wrinkle (noun) is Runzel. It, too, probably once began with hr-. And we may remember English crinkle “to make small wrinkles.” Old English crympan “to curl” is its next-door neighbor. As always, the mysterious “movable s” (s-mobile) is round the corner. The adjective scrimp “scanty,” a doublet of shrimp also refers to something small. (See the post “A scrumptious shrimp with a riddle” for 18 April 2012.)

A pumpkin by any other name would not smell as sweet.

A pumpkin by any other name would not smell as sweet.(Photo by Olivia Kulbida on Unsplash, public domain)

Are German Runzel and English wrinkle related? Friedrich Kluge believed that they are. Those who edited his German etymological dictionary were not so sure. Neither are the authors of English dictionaries. Our answer depends on the readiness (or the lack thereof!) to admit that close synonyms influence one another or that they even generate one another by varying or swapping their initial consonant groups: wr– ~ hr– ~ kr– ~ skr-. Such variants fit words of various emotional spheres. In Middle English, wrinkle meant not only “a fold” but also “winding” (in general). The past participle (ge)wrinclod has been glossed as “winding.” The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, to which I referred above, a manual derivative of the great OED, has a rather unexpected entry, namely wr-. It says that this consonant combination occurred initially in many words implying twisting or disruption, the earlier of which often have cognates in other Germanic languages.

Such cases have been explored in depth by linguists studying iconicity, that is, ties between sound and meaning. In this blog series, sound-imitative and sound symbolic words are mentioned in almost every post. Obviously, if you can wriggle, you can also “(h)riggle,” “kriggle,” “piggle-wiggle,” “skriggle,” and of course “niggle” and “squiggle” (the latter, allegedly, a blend of squirm and wriggle). Some students of iconicity isolate such initial groups and compare them to ancient prefixes. (I have little enthusiasm for this procedure.) Not improbably, language was once “iconic” in all its elements, but we are so far removed from that remote epoch that no definite conclusions are possible. Apparently, some languages (for instance, Semitic) lend themselves to this type of reconstruction better than others. On this note, we may say that wrinkle does have relatives but only by marriage, rather than by birth. Having satisfied ourselves with this dubious solution, we may go on to pimples.

The iconic pimple An iconic pimple.

An iconic pimple.(Photo by Anna Nekrashevich via Pexels, public domain)

Pimples are not only unpleasant: they are also iconic. The substance of what I am going to say was discussed very long ago in my two posts: “On pimps and faggots” and “On faggots and pimps” (6 June and 13 June 2007), so that I’ll be brief. (I have to repeat my plea to those who happen to read the posts years after their publication: don’t leave your comments there, for how can I know that they exist? Add your notes to the most recent post or at least call my attention to the relevant blog post!). The root of pimp refers to something small and insignificant. Pimp denoted (and perhaps still denotes) a youngster in a logging camp or in a mine. The closed vowel i refers to a diminutive size. A pimple is not insignificant but tiny (teeny-weeny). Perhaps you want to feed your child, so that the youngster may become big and fat. Then pamper the beloved offspring and demonstrate the fruit of your endeavors with due pomp. If the verb pimper had existed, it might have meant “to spoon-feed” or “to starve to death.” Pomp and pump also command respect: their root vowels evoke a picture of something big and significant (think of pumpkin). Pumpernickel, we are told, is a word of unknown etymology. I believe that the etymology is known but will bring no one any joy: you eat this food, distend your stomach, and produce a big pump(f).

A pimpernel. An extra letter has done it no harm.

A pimpernel. An extra letter has done it no harm.(Jan Buchholtz, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This, by the way, is not my fanciful idea. I hasten to protect myself, because researchers are afraid of only two things: of saying something novel (and thus becoming a target of the opponents’ abuse) and repeating something that is already known (and thus being ridiculed for offering a trivial idea). This etymology of pumpernickel is not mine, but it is not fully trivial, so that I hope to escape the vituperation from both sides. If you have no more important things to deal with, consider the plant name pimpernel. The Romance etymon was presumably piperīnella, whose root is Latin piper “pepper.” Whose caprice was responsible for inserting m into this root?

Mole: a victim of taboo?Before we wind up, let us not forget moles on the skin. Mole has a cognate not only in older German but also in fourth-century Gothic, where it glossed Greek rutīs. Thus, “wrinkle” (and, incidentally, “any physical defect!). The German verb with this root meant “to stain” and later “to soil.” Perhaps the original meaning of the Germanic noun was “blemish.” Numerous words beginning with m have been proposed as presumably shedding light on mole, but none is close enough to clinch the argument. The names of diseases often fall victim to taboo: people were afraid to call something dangerous by its name and invented innocent-sounding substitutes. Moles are usually brown or black. Did the dark color frighten the superstitious? Were the original moles only black? Quite often, such stains on the skin brought forth associations with the Devil’s mark, and before the conversion to Christianity perhaps with the mark of evil forces. Let us draw a curtain of charity (as Mark Twain put it) of this horror.

A mole, black and innocuous.

A mole, black and innocuous.(Pixabay, public domain)

Yes, and what about German Mal “stain” and English mole, an animal name? Both are partly obscure, but neither is related to mole “spot on the skin.” I wish I could refer to something “symbolic” to save the innocent animal from its dark habitat and to remove a stain from a list of German unsolved cases, but I cannot.

The Oxford Etymologist wishes you happy holidays and a less tempestuous year than the one we are leaving behind. See the next post on Wednesday 11 January 2023.

Featured image by Moe Magners via Pexels, public domain

December 13, 2022

Nine literary New Year’s resolutions

Do you need some inspiration for your New Year’s resolutions? If you’re in a resolution rut and feeling some of that winter gloom, then you’re not alone. Most New Year’s goals fit into the predictable categories of losing weight, taking more holidays, reading more, drinking less alcohol, and giving up smoking. Despite the day-to-day nature of these aspirations, most people go back on their New Year’s resolutions by the end of the first week of January!

To help you on your way to an exciting start to the year, we’ve enlisted the help of some of history’s greatest literary and philosophical figures–on their own resolutions, and inspiring thoughts for the New Year.

1. Count your blessings“Very many things to be grateful for, since then, however. Increased reputation and means—good health and prospects. We never know the full value of blessings ’till we lose them (we were not ignorant of this one when we had it, I hope) but if she were with us now…I think I should have nothing to wish for, but a continuance of such happiness.”

– Charles Dickens writes a poignant diary entry on 1 January 1838, regarding the death of his sister-in-law. She had briefly lived with the Dickens, and died in his arms after a brief illness in 1837 reminding us to count our blessings whilst they’re still with us.

2. New Year, new start“Cheer up! Don’t give way. A new heart for a New Year, always!”

– A more positive resolution from Dickens’ The Chimes, prompting us to take courage as a new start is always just around the corner.

3. Treat yourself! “La morte di Seneca, Musée du Petit-Palais, Parigi” by Jacques Louis David (1773). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“La morte di Seneca, Musée du Petit-Palais, Parigi” by Jacques Louis David (1773). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“We went nowhere without figs and never without notebooks; these serve as a relish if I have bread, and if not, for bread itself. They turn every day into a New Year which I make ‘happy and blessed’ with good thoughts and the generosity of my spirit.”

– Take a lesson from Seneca and remember to treat yourself this January. Romans traditionally exchanged gifts of figs and dates on New Year’s Day, and they still symbolise prosperity and security to this day.

4. Go with the flow“I opened the new year with what composure I could acquire…and I made anew the best resolutions I was equal to forming, that I would do what I could to curb all spirit of repining, and to content myself calmly—unresistingly, at least, with my destiny.”

– In stoic fashion on 1 January 1787, Frances Burney (the English satirical novelist) resolves to content herself with her destiny. If you’re struggling to retain your composure this January, “be like Burney” and go with the flow.

5. Rise early“I have risen every morning since New Year’s day, at about eight; when I was up, I have indeed done but little; yet it is no slight advancement to obtain for so many hours more, the consciousness of being.”

– Samuel Johnson reminds us of the pleasures of early rising. He notes that waking early is not just to get more done in the day, but to extend the pleasure of our own “consciousness of being.” Why not join Dr Johnson, and add an extra hour to your days?

6. Seize the moment“‘A merry Christmas, and a glad new year,’

Strangers and friends from friends and strangers hear,

The well-known phrase awakes to thoughts of glee;

But, ah! it wakes far different thoughts in me.

[…] I, on the horizon traced by memory’s powers,

Saw the long record of my wasted hours.”

Portrait of William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott (1792), from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott (1792), from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

– Amelia Alderson Opie’s Epistle to a friend on New Year’s Day finds the author wishing she’d seized the moment the previous year. Take some inspiration from Opie, and Carpe Diem this year!

7. Think of others first“I dread always, both for my own health and for that of my friends, the unhappy influences of a year worn out; but, my dear Madam, this is the last day of it, and I resolve to hope that the new year shall obliterate all the disagreeables of the old one. I can wish nothing more warmly than that it may prove a propitious year to you.”

– The poet William Cowper (who suffered from periods of depression and mental illness) wishes his friend an auspicious new year. If you were faced with “disagreeables” over the last year, try sending out the positive vibes this January.

8. Leave the past behindRing out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow:

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.

– Forming part of Tennyson’s In Memoriam A.H.H., a poem lamenting the death of his beloved friend, these lines remind us that time waits for no man—and neither should we.

9. Don’t forget ‘dry January’

“Thanks be to God, since my leaving drinking of wine, I do find myself much better and to mind my business better and to spend less money, and less time lost in idle company.â€

– On 26 January 1662, Samuel Pepys is thankful that he has kept his resolve with a seventeenth century dry January. If the old ones really are the best, why not follow in his footsteps and participate in a January dryathlon?

Featured image credit: “Budapest, Parliament, Fireworks” by 733215. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Nine literary New Year’s resolutions appeared first on OUPblog.

Nine literary New Year’s resolutions

Do you need some inspiration for your New Year’s resolutions? If you’re in a resolution rut and feeling some of that winter gloom, then you’re not alone. Most New Year’s goals fit into the predictable categories of losing weight, taking more holidays, reading more, drinking less alcohol, and giving up smoking. Despite the day-to-day nature of these aspirations, most people go back on their New Year’s resolutions by the end of the first week of January!

To help you on your way to an exciting start to the year, we’ve enlisted the help of some of history’s greatest literary and philosophical figures–on their own resolutions, and inspiring thoughts for the New Year.

1. Count your blessings“Very many things to be grateful for, since then, however. Increased reputation and means—good health and prospects. We never know the full value of blessings ’till we lose them (we were not ignorant of this one when we had it, I hope) but if she were with us now…I think I should have nothing to wish for, but a continuance of such happiness.”

– Charles Dickens writes a poignant diary entry on 1 January 1838, regarding the death of his sister-in-law. She had briefly lived with the Dickens, and died in his arms after a brief illness in 1837 reminding us to count our blessings whilst they’re still with us.

2. New Year, new start“Cheer up! Don’t give way. A new heart for a New Year, always!”

– A more positive resolution from Dickens’ The Chimes, prompting us to take courage as a new start is always just around the corner.

3. Treat yourself! “La morte di Seneca, Musée du Petit-Palais, Parigi” by Jacques Louis David (1773). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“La morte di Seneca, Musée du Petit-Palais, Parigi” by Jacques Louis David (1773). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.“We went nowhere without figs and never without notebooks; these serve as a relish if I have bread, and if not, for bread itself. They turn every day into a New Year which I make ‘happy and blessed’ with good thoughts and the generosity of my spirit.”

– Take a lesson from Seneca and remember to treat yourself this January. Romans traditionally exchanged gifts of figs and dates on New Year’s Day, and they still symbolise prosperity and security to this day.

4. Go with the flow“I opened the new year with what composure I could acquire…and I made anew the best resolutions I was equal to forming, that I would do what I could to curb all spirit of repining, and to content myself calmly—unresistingly, at least, with my destiny.”

– In stoic fashion on 1 January 1787, Frances Burney (the English satirical novelist) resolves to content herself with her destiny. If you’re struggling to retain your composure this January, “be like Burney” and go with the flow.

5. Rise early“I have risen every morning since New Year’s day, at about eight; when I was up, I have indeed done but little; yet it is no slight advancement to obtain for so many hours more, the consciousness of being.”

– Samuel Johnson reminds us of the pleasures of early rising. He notes that waking early is not just to get more done in the day, but to extend the pleasure of our own “consciousness of being.” Why not join Dr Johnson, and add an extra hour to your days?

6. Seize the moment“‘A merry Christmas, and a glad new year,’

Strangers and friends from friends and strangers hear,

The well-known phrase awakes to thoughts of glee;

But, ah! it wakes far different thoughts in me.

[…] I, on the horizon traced by memory’s powers,

Saw the long record of my wasted hours.”

Portrait of William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott (1792), from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott (1792), from the National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.– Amelia Alderson Opie’s Epistle to a friend on New Year’s Day finds the author wishing she’d seized the moment the previous year. Take some inspiration from Opie, and Carpe Diem this year!

7. Think of others first“I dread always, both for my own health and for that of my friends, the unhappy influences of a year worn out; but, my dear Madam, this is the last day of it, and I resolve to hope that the new year shall obliterate all the disagreeables of the old one. I can wish nothing more warmly than that it may prove a propitious year to you.”

– The poet William Cowper (who suffered from periods of depression and mental illness) wishes his friend an auspicious new year. If you were faced with “disagreeables” over the last year, try sending out the positive vibes this January.

8. Leave the past behindRing out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow:

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.

– Forming part of Tennyson’s In Memoriam A.H.H., a poem lamenting the death of his beloved friend, these lines remind us that time waits for no man—and neither should we.

9. Don’t forget ‘dry January’

“Thanks be to God, since my leaving drinking of wine, I do find myself much better and to mind my business better and to spend less money, and less time lost in idle company.”

– On 26 January 1662, Samuel Pepys is thankful that he has kept his resolve with a seventeenth century dry January. If the old ones really are the best, why not follow in his footsteps and participate in a January dryathlon?

Featured image credit: “Budapest, Parliament, Fireworks” by 733215. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers