Oxford University Press's Blog, page 62

November 30, 2022

How to identify a scientific fact

When do we have a scientific fact? Scientists, policymakers, and laypersons could all use an answer to this question. But despite its obvious importance, humanity lacks a good answer. The renowned biologist Ernst Mayr was one scientist—probably one of many—frustrated by the fact that philosophers of science haven’t developed an account of the transition from theory to fact*. And recently an IPCC Special Report author explicitly asked, “Where is the boundary between ‘established fact’ and ‘very high confidence’?”. The truth is, nobody really knows.

And it matters. We want governments to base policies on scientific facts, insofar as that is possible. And the IPCC Report writer needs to know whether they are allowed to simply state something, or if they need to include a clause in brackets at the end of their statement: “(very high confidence)”. Moreover, in a world where we have no account of “scientific facts,” it is no wonder we encounter so much scepticism regarding even the most secure scientific claims.

The lack of an account is surprising, and needs explaining. Why haven’t science scholars devoted time to this issue? Within professional philosophy of science, one reason is the continuing influence of Thomas Kuhn and Karl Popper. These are possibly the two biggest names in twentieth-century philosophy of science. But neither Kuhnian nor Popperian philosophies allow room for “scientific facts.” On the Kuhnian picture, we are always interpreting reality from inside a particular “paradigm.” One might speak of facts within a paradigm, but these facts are “soft”—following a scientific revolution a new paradigm will emerge, with different facts. And whilst Popper disagreed with Kuhn about many things, his philosophy also denied that science can ever deliver truth; for Popper, even the most solid scientific claims could be falsified at any moment.

“In a world where we have no account of ‘scientific facts,’ it is no wonder we encounter so much scepticism regarding even the most secure scientific claims.”

If the two most famous philosophers of science of the twentieth century ruled out “scientific facts,” perhaps we should take that very seriously. And it has been taken seriously: for several decades, philosophy departments around the world have taught their undergraduates Kuhn and Popper, and generally have not taught the idea that there are genuine “future-proof” scientific facts. Indeed, it has been more fashionable to teach the virtues of epistemic humility. We all know that humility is a virtue. That would apparently make a belief in future-proof scientific facts a vice, tantamount to arrogance or hubris. Certainly some would consider it unprofessional, for example because it reflects a “shocking ignorance of the history of science,” a history where scientific ideas have so often been overturned by shifts in thinking, and even grand large-scale revolutions.

This story ends with an extraordinary clash of perspectives. In 2015, a doctoral student at the LSE—educated in the classic tradition of philosophy of science—surveyed geologists. He asked them, “Because we cannot directly observe entities and processes in the geological past, some philosophers of science contend that they cannot be said to exist in reality. Do you think they are correct?” Now, professional geologists know—without any doubt—that the Earth has experienced past ice ages. Some geologists dedicate their entire career to specialising in the details of a particular ice age, such as the Late Paleozoic Ice Age. Imagine, then, how such a geologist would react to the idea that many philosophers of science muse that such ice ages probably didn’t exist and are just “nice ideas” that are currently popular amongst scientists who have been indoctrinated into a particular paradigm. Indeed, the doctoral student behind the survey reports, “Some were affronted by the suggestion that what they were studying might not be real in some way.”

The truth is, there are many established scientific facts, and scientists know this well. The claim that dinosaurs roamed the Earth many millions of years ago is one such example. This was already beyond reasonable doubt 100 years ago; today, in 2022, it is far beyond reasonable doubt. It is only uncertain in the tedious, academic sense that one can doubt almost anything if one tries hard enough. And there are many such examples: scientific ideas that were once hypotheses, and gradually transitioned—as a result of scientific labour—to become far beyond reasonable doubt. The fact that the Sun is a star, continental drift, and the high-school textbook account of human respiration, are three very obvious examples.

Since there are examples of facts, it is high time we developed a serious theory, a set of criteria that are sufficient for a scientific claim to count as an established scientific fact. The story is a long one, but for now let’s skip to the end: future-proof, established scientific facts can be identified via a solid (>95%) international scientific consensus, born of scientific labour, in a community that is large and diverse. In the entire history of science, no claim meeting these criteria has ever been overturned, despite enormous opportunity for that to happen (if it were ever going to happen). Or so I argue in Identifying Future-Proof Science.

*With thanks to Paul Hoyningen-Huene for directing me to this.

Featured image by Joel Filipe on Unsplash, public domain

Say cheese, or l’esprit d’escalier neglected and forgotten

As everybody knows, the phrase in the title, l’esprit d’escalier, refers to a good thought occurring too late. Now that my explanatory and etymological dictionary of English idioms has been published, I keep looking it through and often regret missed opportunities. Why didn’t I search for such and such phrase on the Internet? If I had done so, I would have added a nice explanation or two. But I’ll let my prospective reviewers upbraid me and today will only write about a few curiosities in the corpus.

In 1888, the regional phrase to join giblets was known (perhaps it still is). I am writing this blog post during the Thanksgiving week, and turkeys (giblets and all) occupy a prominent place in newspapers. The explanation I ran into sounds so: “The phrase denotes a close partnership in Yorkshire but has an offensive meaning in Lincolnshire.” The oldest meaning of the phrase was “to marry,” and the OED uncovered a 1681 citation of the odd idiom. I assume that “the offensive meaning” is “to have sex,” the giblets being a euphemism for the genitals. The next idiom—join you flats! “do your business properly”—is more innocent, and, if I am not mistaken, it cannot be found in the OED. Flats are the halves as are formed by two equal parts pushed from the sides of the stage and meeting in the center. The phrase seems to go back to an incident in the Old Vic, when the back scenes would not meet and somebody shouted from the gallery: “We don’t expect no grammar, but you might let the scene meet,” quoted from James Robinson Planché’s Recollections and Reflections (1872), I: 127. A century ago, some people understood this phrase.

Giblets: join them, join them!

Giblets: join them, join them!(Joel Abroad, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

All of us realize that that the OED is huge, while everybody’s mastery of the vocabulary is poor, but it is still surprising how some seemingly popular phrases fall into disuse. I have once written about this phenomenon. No one whom I have “polled” recognized the idiom let George do it, that is, “let somebody else do it,” though I knew someone called George who had a repair shop and called it accordingly. He meant himself and apparently expected to be understood, but was he? Decades ago, I was warned that the phrase keep your pecker up is fairly innocent in England (pecker “nose”) and obscene in America. Again, no one I asked in Minnesota (where I live) knew the phrase, though everybody understood the reference to pecker.

Since my database depends on the notes by contributors to the popular press for roughly three centuries, it could be expected that many old idioms would be incomprehensible today, but it turned out that even some fairly modern phrases make no sense to us. For instance, butter out of a dog’s mouth, which means “you can’t retrieve what you have lost.” I admire another brilliant phrase that seems to have been coined by some wit, though its author has not been discovered. The phrase is new terror to death, which means “a posthumous biography published soon after the person’s death and vilifying him.” Swift knew it as early as 1703, and one shudders at its eternal aptness. De mortuis aut bene aut nihil? Alas, the Roman injunction not to speak ill of the dead has always been wishful thinking.

Sometimes the commentary of a century or so ago sounds surprising to us. What could be wrong with the phrase to return thanks? But read the exchange in Notes and Queries for 1902: “One of the oddest and most out-of-place phrases is that of ‘returning thanks’ which appears in tradesmen’s business announcements and notices. It is understood to be the tradesman’s way of thanking his customers for their past favours. Giving thanks would, perhaps, be better, for his customers would scarcely thank him for allowing them to deal with him.” However, this statement was rebuffed by another correspondent: “A return may be made that is not a return in kind; and I hold that a customer has often as much occasion to thank the tradesman for his attention he has given to his wants as the tradesman has to thank the customers for his patronage.” Other than that, the OED cites the phrase to return thanks from the end of the sixteenth century! Old as the hills, right?

Tace!

Tace!(sudheerinfo99, via PixaHive, public domain)

Some “locutions” are mysterious despite the many attempts to explain them (including today on the Internet). Such is, for example, “Tace is Latin for a candle,” known from books, according to the OED, since at least 1605. Swift, Fielding, and other good authors used the phrase in their writings. Did they understand its hidden (or implied?) meaning, and did they know its origin? Amassing quotations will not explain anything, because tace is Latin for “be silent!” (the imperative of tacēre), rather than “candle”! It has been suggested that the mysterious phrase has its roots in some rites of the Catholic church. If a candle is thrown, it will be extinguished, and darkness (“silence”) will be the result. Or a guttering candle might be an image of a dying man. Those suggestions are not quite improbable. The OED refers only to a humorously veiled hint to anyone to keep silent about something. True enough, and the use of the phrase by Swift reinforces the idea of humor, but still, what does the phrase mean? On the surface, it is absolutely meaningless.

Sometimes modern usage seems to confirm a questionable etymology. Under the weather may go back to the phrase under the wind, that is, “protected from the wind” (though I can detect no logic here!), but more important is the suggestions that the phrase originated in American English. The suggestion seems to be correct. Like any other instructor, I constantly receive letters from my students informing me that they are indisposed and will have to miss the class. It most cases, they say that they are under the weather. If this nautical (?) phrase was coined in America, it may explain why it is so popular there.

That’s the cheese!

That’s the cheese!(Alexander Maasch on Unsplash, public domain)

The stray notes above have only one aim. I wanted to remind our readers that the history of idioms is as complicated and as worthy of attention as the origin and fortunes of individual words. Specialists have no doubts on this point. There is a European society for the study of idioms, and there are linguistic journals devoted to this subject. People have been collecting proverbs and curious phrases for centuries. Erasmus was keenly interested in the subject, but for language lovers idioms are an inexhaustible source of curiosity and pleasure. If you ask me about idioms (and I hope you will), I’ll answer: “That’s just the cheese!” My phrase has, most probably, an Anglo-Indian origin, but why the real thing is called “cheese” is something no one knows for sure. (However, as one of my colleagues used to say on similar occasions, there has been a lot of research on this subject). Stay turned!

Featured image by MrsEllacott, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Bringing the Church back in: European state-formation, AD 1000-1500 [long read]

Popes are fascinating, whether invented or real. A few years ago, the TV-series The Young Pope, starring Jude Law in the title role, was a big hit both in Europe and in America. In 2019, The Two Popes, a film based on the relationship between former Pope Benedict XVI and the present Pope Francis, received numerous accolades among critics.

I like it, too; I watched it during one of the Danish COVID-19 lockdowns. The next day, I remember thinking that if I were at my office, I would have swung by some of my colleagues to put them a question I am sure they have not gotten before: Who is your favourite pope of all time? Instead, I tried to google the sentence but got no unique hits.

Of course, the answer depends on what kind of pope you want. For some diehard conservatives (not sure I could find one among my colleagues at the department), it might be Pius IX, whose Syllabus of Errors from 1864 openly denounced modern liberalism and who presided over the First Vatican Council in 1869-70 and its proclamation of the twin principles of papal primacy and infallibility. For liberals, it might be Pope John XXIII who called the Second Vatican Council, which in the years 1962-65 reformed the Church and reconciled it with democracy and political liberalism. For those who emphasize social justice, Pope Francis—taking his papal name after St Francis, patron saint of the poor—seems a good bet. And despite all the negative stuff I have been reading about his stint as Jesuit provincial superior in Argentina during the 1970s, Francis or Jorge Mario Bergoglio, played by Jonathan Pryce, comes off as very likeable in The Two Popes.

However, the importance and eccentricities of these contemporary or near-contemporary popes pale when compared to some of their predecessors. In a new book, co-authored with Jonathan Stavnskær Doucette, we have looked at the real thing: the great medieval lawyer-popes, who dominated the European political and religious scene in an era where all roads literally led to Rome. My own favourite (thank you for asking) would be Innocent III, a Roman nobleman and canon lawyer who became pope at the tender age of 37, and whose papacy from 1198 to 1216 left several important legacies.

A lot of what Innocent did, we would today consider unsavoury—especially the way he directed crusades against what he considered heretics and infidels. But our book mainly looks at the way his papacy affected political institutions and the multistate system.

We could not have done this were it not for the insights of generations of medieval historians, including Walter Ullman, R.W. Southern, Gaines Post, H.E.J. Cowdrey, Francis Oakley, Harold Berman, Richard Kay, Chris Wickham, Colin Morris, Robert Bartlett, and R.I. Moore. As they have shown, separating the religious sphere from the secular sphere is not really meaningful when we analyse political developments in medieval and early modern Europe.

One of the prime examples of this is how during Innocent’s watch the Roman Church adopted the principles of representation and consent, which were to leap quickly to the secular sphere, there to lay the foundation for medieval representative institutions or parliaments, and hence for the European tradition of representative government. These were arguably the two greatest political innovations of the middle ages and, as virtually all other intellectual innovations in this period, they hail from the Church.

The internal balancing act of European state-formationIn our book, we show more generally how the medieval Church bolstered what we term the internal balancing act of European state-formation: vibrant social groups matching or at least constraining rulers. Besides inventing representation and consent—and hence the medieval parliaments which spread to almost all polities in Western and Central Europe in the period 1200-1500—we locate the origin of urban self-government in interactions between ecclesiastical institutions and townsmen.

This story takes us back to the so-called Cluniac reforms, which began in southern France in the tenth century and the aim of which were to secure the freedom of the Church by fighting simony (selling ecclesiastical offices) and clerical inchastity (nicolaitism). The core recruits of the Cluniac reform coalition were monks; the name itself comes from the monastery of Cluny in Bourgogne.

“We locate the origin of urban self-government in the interactions between ecclesiastical institutions and townsmen.”

But the coalition included laymen, often fervent believers, as the monks depended on secular arms to police the freedom of the Church. For this reason, the Cluniac reforms came to engulf towns across much of France, northern Spain, the Rhineland, and northern Italy. Townsmen inspired by the reforms came to realize that they had to take political power to implement the Cluniac reforms in the face of resistance from unreformed lord-bishops and their followers. The result was urban political autonomy or self-government, which first spread in the vicinity of Cluniac monasteries and which mainly affected bishop towns.

The Dominican mendicant monastic order spread the principle of representation to towns further afield after its founding in 1216. The Dominicans were crucial vessels of representation because they were so prominent in the townscape. As opposed to the Cluniacs, their influence also extended to the peripheral areas of the Latin west, including Scandinavia.

Finally, a more general aspect of the internal balancing act was that the Church itself established political independence. European state-formation would have looked very different if rulers did not constantly have to negotiate with a strong clergy, independent townsmen, and the nobility over, inter alia, the wherewithal for warfare, succession, and public peace.

How the medieval Church reshaped European societyBut the medieval Church shaped European societies in other ways than this. It was the one institution of late antiquity that survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century, and it carried the torch of the Roman world after the Empire collapsed. In Edward Gibbon’s unkind but strangely apt metaphor, the medieval papacy was “the Ghost of the deceased Roman Empire, sitting crowned upon the grave thereof.”

During the early middle ages, it was only within monasteries that men of letters survived to tell posterity of their thoughts and to preserve a flickering light of learning. In the words of British sociologist Perry Anderson, the Church constituted “the main, frail aqueduct across which the cultural reservoirs of the Classical World now passed to the new universe of feudal Europe, where literacy had become clerical.” This towering intellectual position allowed the medieval Church to reshape European societies in fundamental ways.

“Virtually all intellectual innovations in the middle ages hail from the Church.”

Perhaps most consequentially, its doctrines about heirship and marriage transformed European family structures. In the early Middle Ages, the Church forbade a series of hitherto common heirship practices, including consanguineous marriages (for instance between cousins), divorce and remarriage, adoption, and concubinage. Children born out of wedlock were treated as illegitimates who could not inherit property or the family name. The first prohibitions seem to have been introduced at the Council of Neocaesaria in 314 but it was only in the eleventh and twelfth century that the Church started to actively enforce them. This gradually paved the way for the monogamous marriage and the nuclear family—or, as British sociologist Jack Goody put it, for “out-marriage” to replace the “in-marriage” that had characterized even the Roman world, and which is still common in the Middle East and India today.

In this way, the Catholic Church set the stage for primogeniture, the succession order where the eldest son inherits the patrimony. In another book published by OUP, I and my two co-authors, Andrej Kokkonen and Anders Sundell, have analyzed the consequences of this for political stability. Jonathan and I instead look at how it affected the international system. We develop an insight made by the German historian Otto Hintze almost a century ago, in an essay where he identified the competition between religious and lay power as the root cause of the European multistate system.

In context: from “bad popes” to papal reformTo understand this, we need to place medieval lay-religious relations in context. Until the second half of the eleventh century, Western European monarchs, such as the German emperor, controlled ecclesiastical institutions in their own realm. Most important was the right to appoint bishops and abbots, who made up a kind of surrogate state apparatus in a situation where there was no organized lay administrative structure.

This control of ecclesiastical institutions was merely one aspect of a more general model of “sacral monarchy.” According to historians, European monarchies in this period approximated the “Byzantine” model variously termed ceasaropapism or Rex-Sacerdos, where religious and lay power are fused rather than divided. Monarchs were even seen as the vicars of Christ, while the papacy was all but powerless, mired in scandal and corruption and controlled by Roman noble families or German emperors who took the trouble to travel across the Alps and visit Rome. Indeed, the 900s have come to be known as the century of the “bad popes”, or even the “pornocracy” of the papacy.

”The competition between religious and lay power [is] the root cause of the European multistate system.”

However, this changed after AD 1050 with the papal reform program. What happened was that the Cluniac reforms, described above, were transplanted to decadent and impious Rome. In the first place, the aim was therefore to fight simony and nicolaitism, not only locally but within the ecclesiastical hierarchy more generally. This cleaning of the papal house was sponsored by the strong and pious Salian Emperor Henry III, who in 1046 deposed three rival popes and in 1049 appointed the first reform pope, his relative Bruno of Egisheim-Dagsburg, henceforth known as Pope Leo IX (r. 1049-1054).

Leo was followed by a string of other reform popes, and the push for church reform climaxed in 1073 with the election of another mercurial pope, Gregory VII (r. 1073-1085). Gregory famously threw down the gauntlet to Henry III’s eldest son and heir, Henry IV. The result was the Investiture Controversy from 1075 to 1122, which centred on whether popes or emperors had the right to appoint bishops. The story about the uncompromising conflict between Gregory and Henry is the stuff great fiction is made of. It includes Gregory’s affinity for and debt to Henry’s pious parents, the vainglorious young king’s chastening at Canossa in 1077, and Pope Gregory’s humiliating flight from Rome in 1084 and later death in exile in Salerno in 1085.

Gregory thus lost the last battle against Henry, but he may be said to have won the war, posthumously at least. Later reform popes such as Pope Urban II, the initiator of the crusades, shored up the reform coalition and an exhausted Henry V, son of Henry IV, who he deposed on the last day of the year 1105, came to terms at Worms in 1122.

This great conflict sowed the seeds of the European multistate system. To weaken Henry IV, Gregory attempted to call on and bolster other Christian monarchs, even in the newly Christianized northern European periphery. As the medievalist H.E.J. Cowdrey puts it:

Gregory sought to foster among the nations something like a balance of power: more distant peoples were to be established in their independence from outside political supremacy and in the habit of obedience to the papacy; by such means, the power especially of the Salian monarchy in Germany might be kept within bounds.

Or as Pope Gregory himself described it in a letter to Danish King Sweyn Estrithson: “the king of a distant realm was, by strong and righteous rule, to compensate for the unreliability of rulers who were nearer to Rome.”

”The medieval Catholic Church was the engine behind the power pluralism of European state-formation, the crucial precondition for modern states, the market economy, and modern democracy.”

Later reform popes would continue this divide-and-conquer policy. This development climaxed around 1200, where popes such as the aforementioned Innocent III proclaimed the principle “the king is emperor within his own realm” (Rex in regno suo imperator), the complete opposite of the old theory of the emperor lording over the Church and other monarchs. In this way, the Church stimulated what we term the external balancing act of European state-formation. In another new book, Sacred Foundations, Anna Grzymala-Busse further documents these religious roots of the modern state and state system in a very convincing way, enlisting other new historical data.

The medieval Catholic Church was thus the main engine behind the power pluralism—within polities and between polities—that came to characterize European state-formation, seen by generations of scholarship as the crucial precondition for the later development of modern states, the market economy, and modern democracy.

These developments were obviously not intended; they were unanticipated consequences of popes fighting to secure their own political, religious, or even personal interests. This, of course, is exactly why popes are so fascinating. Most of them have probably been fervent believers, convinced that they pursued the ends of the Church—paving the way for the vita religiosa—not their own self-interested concerns. But they have also been humans of flesh and bone; sometimes callous, oftentimes jealous men with sympathies and antipathies, ready to rationalize their mundane actions and needs with religious arguments. The annals of papal history contain the kind of drama of novels which are difficult to put down. At different times, popes have performed miracles of law-making and statecraft. At other times, vanity and folly have led them astray, and the number of backstabbing popes is legion. What’s not to like!

Featured image by ArtHouse Studio, via Pexels, public domain

November 29, 2022

Looking into space: how astronomy and astrophysics are teaching us more than ever before [podcast]

It’s been 500 years since the first circumnavigation of the globe, and few could have predicted then that we would see detailed images of stars, galaxies, and exoplanets like the ones produced by the James Webb Space Telescope this year.

On today’s episode of The Oxford Comment, we’re looking at what these recent discoveries mean to our understanding of the universe. Why should we all know about distant galaxies? How will this learning impact us? And what role will artificial intelligence and machine-learning play in the wider astronomy field in the coming years?

The questions are big, the area is even bigger, and we are delighted to be joined by two eminent fellows from the Royal Astronomical Society to review this expansive subject.

First, we welcome Claudia Maraston, Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Portsmouth, and an expert in theoretical astrophysics, in particular the calculation of theoretical spectra for stellar populations. She also sits on the editorial board of Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Our second guest is Jonathan Tennyson, Massey Professor of Physics at University College London, whose research specialises in the accurate quantum mechanical treatments of both the spectroscopy and collision properties of small molecules, with an emphasis on the provision of data for other research areas. Jonathan is also Editor-in-Chief of the Open Access Royal Astronomical Society Techniques & Instruments.

Check out Episode 78 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Looking Into Space – Episode 78 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingTo learn more about the themes raised in this podcast, we’re pleased to share a selection of free-to-read chapters and articles.

If you would like to find out more about recent discoveries in observational astronomy, why not start with a title in our Very Short Introductions series, Observational Astronomy: A Very Short Introduction, by Geoff Cottrell?

You may also be interested in Astronomy: The Human Quest for Understanding by Dale A. Ostlie, which looks at how science operates practically in relation to astronomy, leading the reader down a path to our present-day understanding of our Solar System, stars, galaxies, and more.

If you’re interested in the role ordinary people taking part in cutting-edge science and what humans can bring to interpreting big data which smart machines can’t, The Crowd and the Cosmos: Adventures in the Zooniverse by Chris Lintott highlights that “You, too, can help explore the Universe in your lunch hour.”

Articles by our guests Claudia Maraston and Jonathan Tennyson can be found in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Tennyson also co-wrote this introductory article to RAS Techniques and Instruments earlier this year.

Discover more about the James Webb Telescope on Oxford Academic through our range of journal articles, many of which are Open Access. This range includes Royal Astronomical Society articles such as the following:

“Hiding in plain sight: observing planet-starspot crossings with the James Webb Space Telescope” by Giovanni Bruno et al.“Conditions for detecting lensed Population III galaxies in blind surveys with the James Webb Space Telescope, the Roman Space Telescope, and Euclid” [Open Access] by Anton Vikaeus et al.Featured image: “NASA’s Webb Reveals Cosmic Cliffs, Glittering Landscape of Star Birth,” July 2022. NASA/ESA/CSA, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

November 26, 2022

Excommunication in thirteenth-century England: a volatile tool

The Becket Leaves, a set of thirteenth-century drawings depicting the life of Thomas Becket, include an image of the archbishop pronouncing an excommunication. Becket himself is depicted in the act of throwing a candle to the ground. On the right of the picture, a group of men and women react to this fearsome spectacle. Some of these onlookers, notably the man in the green hat, appear to be cowering in fear. Yet others, at least to a modern eye, look as though they have only contempt for the archbishop and his sentence of excommunication. The image, albeit anachronistically interpreted, encapsulates the varying responses to excommunication in thirteenth-century England. Excommunication was the medieval church’s most severe sanction, but reactions varied from fearful to indifferent to defiant.

Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Via Wikimedia Commons, public domainThe censure implied an afterlife spent in hell: “as this candle is extinguished, thus let excommunicates’ souls be extinguished in hell.” It was not to be taken lightly. Indeed, evidence suggests that the spiritual power of excommunication was not rejected in principle in thirteenth-century England. Dying excommunicate was a terrifying prospect. Adam le Warner, for instance, sought absolution explicitly because he had fallen ill and was afraid to die without having obtained absolution. The problem, however, was that for most excommunicates, the risk of dying was not an immediate one: absolution could be put off. Before falling so suddenly and deathly ill, Adam had been defying the bishop of Lincoln; his attitude changed only when death loomed. Other excommunicates refused to seek absolution from those they believed to be acting unjustly. Llywelyn the Great of Wales eloquently explained his contempt for his own excommunication in 1234: “we prefer to be excommunicated by man, than to do anything against God, with our conscience condemning us.”

Individuals’ own responses to their sentences is only part of the story, however. The entire “communion of the faithful” was supposed to ostracise them. Yet an excommunicate’s associates could deem sentences unfair too. Llywelyn incurred his sentence because he continued to support his ally, Falkes de Bréauté (a rebel against the English king), whom he did not consider excommunicated “as far as God is concerned” (usque ad deum). How excommunications were received by the wider community has been understudied. In many more cases, communities who were supposed to enforce excommunications by avoiding those under the ban failed to do so. The many excommunicates who were able to live while under the church’s ban were only able to do so because their friends and neighbours were not ostracising them as canon law required. Ecclesiastical authority and judgements were often questioned.

The expectation of communal enforcement also meant that excommunication was necessarily a very public matter. Sentences had to be extensively publicised, generally in parish churches on Sundays and feast days. Widely disseminated sentences were an important means through which the laity was informed about local and political disputes. The sentences solemnly publicised also needed to convince people to shun excommunicates, so could be extremely vitriolic. For this reason, excommunicates worried about the defamatory aspects of being under the ban. On the other hand, the publicity attached to sentences also launched the sometimes-questionable behaviour of clerics into the public eye, to be discussed and condemned. This exposed not only individual clergymen to ridicule and derision, but potentially the church’s authority as a whole. The risk of scandal was particularly acute when clergy fought amongst themselves: as the bishop of Hereford observed in 1275, clergy who were mutually excommunicating each other throughout the city risked causing the laity to treat these excommunications no more seriously than they would a jester’s anathema.

Its public nature was thus simultaneously a considerable incentive to use excommunication, and its greatest liability. An especially venomous dispute between the archbishop of Canterbury and the monks of Christ Church in the 1230s, recorded in the monks’ own chronicle, demonstrates this. The monks themselves repeatedly appealed not against their excommunications, but to prevent denunciations, which they treated as a separate issue to excommunication itself. The archbishop’s fellow bishops, meanwhile, tried to dissuade him from publicising his sentence so extensively, seemingly worrying that it would bring the church into disrepute by airing its dirty laundry in public. The citizens of Canterbury, clerical and lay, continued to support the monks, flouting the archbishop’s commands. They were accordingly chastised, but the disputes effects were more widespread. Such a great scandal had been generated by the archbishop’s unreasonable public measures that merchants and pilgrims were avoiding the city entirely.

Excommunication remained a powerful, albeit it volatile, tool. It was certainly best to avoid being sentenced. Yet churchmen using excommunication had limited control over how their sentences played out. The populace could play ball, more or less willingly (those who communicated with excommunicates themselves faced censure, usually interdicts and minor excommunications) or they could render the sanction toothless by refusing to enforce it. Excommunication’s use risked turning the people against the church, potentially causing reactions like those seemingly depicted in the Becket Leaves. The study of excommunication provides a window into medieval attitudes, loyalties, and mass communication.

Featured image by Jaakko Kemppainen via Unsplash, public domain

November 24, 2022

Pursuing deliberative democracy through scientific testimony

Science skepticism is a central threat to deliberative democracy. Generally speaking, scientific investigations based on collaboration between scientific experts are far more reliable than individual efforts when it comes to finding the truth about complex matters. So, since public deliberation is better off when it rests on science, deliberative democracy requires a reasonably high degree of public uptake of science communication. However, there is a great deal of public skepticism toward science communication about polarizing issues (e.g., vaccine safety, climate change). Just consider slogans such as the conspiracy organization QAnon’s “do your own research.”

In my book Scientific Testimony, I identify some causes of science skepticism and consider some strategies for addressing it. Importantly, science skepticism is typically selective. Few people are wholesale science skeptics. Rather, science skepticism typically concerns the science about polarizing issues such as climate change, vaccine safety, gender biases, etc. Consequently, empirical research suggests that motivated cognition is a central source of (selective) science skepticism. Roughly, motivated cognition is the inclination to privilege or discard information in ways that favor those of one’s antecedent views that one is motivated to preserve. When these views are central to the subject’s social identity, the variety of motivated cognition is called identity-protective reasoning. The result is that a group will be resistant to science communication if they perceive it to be in tension with their social identity. Of course, there are many other sources of science skepticism, such as polluted information environments, which include online platforms with their algorithmic filter bubbles, microtargeting, and echo chambers. Further sources of science skepticism are public misunderstandings about the nature of science and folk epistemological biases that go beyond motivated cognition. Likewise, organized science skepticism is a serious threat. Science communication should be sensitive to all these factors.

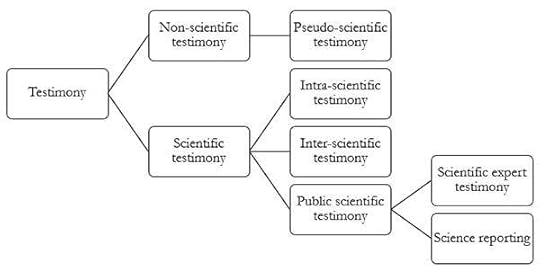

To see which aspects of scientific testimony I will consider on this occasion, have a look at this map of types of testimony from the book:

From Scientific Testimony by Mikkel Gerken

From Scientific Testimony by Mikkel GerkenI argue that scientific testimony differs from other types of testimony in that it is properly based on scientific justification (in Scientific Testimony, chapter three). The category which I focus on in this blog post is public scientific testimony. This is scientific testimony that is directed at laypersons. This category includes scientific expert testimony that is provided by scientific experts as well as science reporting that is provided by non-experts such as science journalists. Both species of public scientific testimony are critical to the pursuit of deliberative democracy.

So, I have developed some general science communication strategies and norms that aim to alleviate these problems for deliberative democracy. For example, the following Justification Explication Norm (JEN):

JEN

Public scientific testifiers should, whenever feasible, include appropriate aspects of the nature and strength of scientific justification, or lack thereof, for the scientific hypothesis in question.

The argument that JEN is a sensible presentational norm for public scientific testimony is supported by both philosophical reflection and empirical research on science communication. For example, some empirical evidence suggests that explicating scientific justification may increase the uptake of polarizing hypotheses across the political spectrum. Moreover, I argue that JEN promotes long-term trust in science and may contribute to the public’s science literacy.

However, explicating scientific justification need not have the ambitious aim that the layperson recipients come to understand the intricacies of the scientific justification. A more reasonable aim is often to provide a basis for what I call laypersons’ appreciative deference to public scientific testimony. Appreciative deference can be based on a rudimentary understanding of the relevant scientific justification. But it may also be based on something even less demanding – namely, an appreciation that public scientific testimony is the most reliable source on the issue. In both cases, appreciative deference to public scientific testimony is generally rational for laypersons.

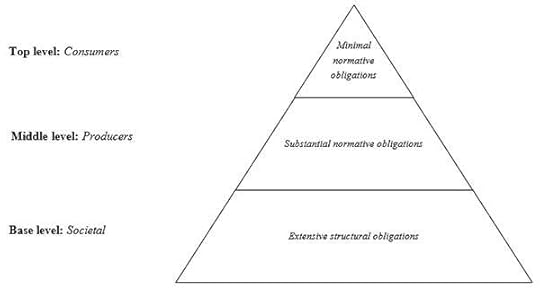

On the basis of these ideas, I have developed epistemic norms for both the producers and consumers of public scientific testimony. I will not discuss the details of these norms here (which are outlined in chapters five and six of Scientific Testimony). Rather, I will discuss a question that they raise: Whose responsibility is it that laypersons appreciatively defer to public scientific testimony? In Scientific Testimony, I argue for the following distribution of normative requirements:

Fairly minimal requirements for the individual layperson consumers of public scientific testimony. Fairly demanding requirements for the individual providers of public scientific testimony. Fairly comprehensive requirements for the society that enables the individual testifiers and recipients to meet the requirements that they are subject to.The idea is that since the layperson recipients are the least equipped to assess public scientific testimony, it is important that they are only minimally burdened. In contrast, stronger requirements for providing public scientific testimony are reasonable since those who are in the business of providing it are generally qualified to do so. However, it is a societal structural task to ensure that the individual providers and consumers of public scientific testimony are able to meet the normative requirements that accrue to them. This division of normative labor may be illustrated by the following Testimonial Obligation Pyramid (TOP):

From Scientific Testimony by Mikkel Gerken

From Scientific Testimony by Mikkel GerkenAccording to the TOP structure, selective science skepticism should be treated as a structural problem that requires societal interventions. That is, the pyramid structure illustrates two things: First, the noted distribution of normative labor. Second, the idea that the individual norms that apply to public scientific testifiers and their recipients must rest on a structural foundation that society is obliged to secure. For example, even impeccable public scientific testimony from scientists and journalists will be severely compromised in an informational environment that is polluted with pseudo-scientific testimony that is indiscernible to laypersons.

In consequence, the foundational societal obligations involve curating the information environment, advancing scientific literacy, and training public scientific testifiers in communicating science about polarizing issues. The TOP illustration, then, provides a warning of individualizing structural problems. More generally, Scientific Testimony is a book that exemplifies how empirically informed philosophy may contribute to diagnosing and addressing science skepticism and similar threats to the pursuit of deliberative democracy.

Featured image by Hansjörg Keller, via Unsplash (public domain)

November 23, 2022

Was it murder? Why a US Navy hanging resonates nearly 200 years later

One hundred and eighty years ago, Captain Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, in command of the United States Navy’s brig Somers, hanged three of his crew on the high seas in the mid-Atlantic. The captain accused the three of mutiny, of conspiring to kill him, his officers, and many of his crew, most of whom were boys. A ship full of pre-teens and teenagers, led by a few adults, Somers was no ordinary warship. It was a floating experiment, a school ship, sent out on this, its first voyage, in 1842 to train boys to become men, to become sailors. But the voyage went badly. It ended with death, recriminations, trials, and law suits, and controversy that continues today.

The “Somers Affair” shocked a nation then in the midst of an economic depression that had lasted for five long years, ruining families and filling the streets with homeless families and orphaned or abandoned children. National arguments over the nature of what it meant to be American, how Americans should live their lives, and most importantly, the direction the country should go in were the subject of intense debate. This was a time marked by the birth of movements seeking to reform the moral character and nature of American society, with arguments for public schools, equality for women, an end to slavery, and a national move to ban alcohol. Unhappy with organized religion, a number of Americans were turning to newly defined faiths. Protracted political turmoil was threatening the hold of old political alliances and parties. There were fears that a vast conspiracy led by the Masonic Order was acting as a cabal to run (and ruin) the nation. All of this made the United States in 1842 a nation as divided and fearful of its future, some might say, as it is in 2022.

Then came the “Somers Affair.” It was more than a scandal that played out in the press of its time. Somers had been built as a vessel to reform the navy through the adoption of social experiments then being argued for by social and religious reformers. The experiment on Somers as a “proper” ship run to the principles sought by those reformers had dramatically failed. The executions shockingly demonstrated the failure of authority; the Captain had been on the brink of losing his ship, or he had never fully asserted his command through leadership, and only took control through violence in the name of stopping violence.

The questions that were debated and litigated centered on both whether Mackenzie possessed the authority to do what he did, but also on the question of if he had the authority, did he do the right thing? The answer is he had the authority, but that he failed in his command to do the right thing long before the hangings. The executions were his tacit admission of failure and of weakness, not of strength. While he had powerful defenders, Mackenzie also had powerful and intelligent detractors, including John Canfield Spencer, the Secretary of War, himself the son of the former Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court. The lead “mutineer” Mackenzie had hanged was the Secretary of War’s 19-year-old scapegrace son, Philip Spencer. As an anguished but enraged father, John Canfield Spencer penned a widely published letter damning Mackenzie’s near-panicked, “unmanly” hanging of the three “mutineers,” and for good reason. He made a case that Mackenzie could have asserted his authority without executions and brought the “mutineers” home to face trial. Mackenzie was not alone in his failure to have avoided the terrible consequences of the voyage of Somers.

Philip Spencer also bore a heavy responsibility for his own execution as well as that of the other two “mutineers” and the arrest of a number of other boys. Philip Spencer arrived on Somers with a long history of misbehavior and petty crimes. As the youngest, coddled son of a distant and harsh father and an adoring mother, early introduced to alcohol by his older brothers, he was wont to flaunt the rules and defy authority wherever he went and whenever he pleased. He had nearly been thrown out of the US Navy twice, but his father’s influence had kept him in. Assigned to Somers, newly built as a sail training vessel to take boys considered “the sweepings of the street,” including orphans and the poor sons of a nation ravaged by a long economic depression, Philip Spencer did not fit in to a small, over-crowded vessel run by a captain in his first sea-going command, with a group of young officers, nearly all family or friends, and insufficient older hands to teach the boys—and properly discipline them.

The voyage of Somers was one of exceedingly harsh discipline, with boys beaten for infractions that ranged from not being fast enough, or disorderly and not clean or neat enough, for rebellious adolescent behavior, and for masturbation. Spencer was disliked by his fellow officers but admired by a number of the boys, for whom he made a show of mocking the captain behind his back, calling Mackenzie a humbug and an ass. He gave boys alcohol and tobacco, both of these forbidden by a morally indignant Mackenzie, and likely had sex with at least one or more of the boys.

In that, Spencer was not alone; there were liaisons between some of the boys with older men on the crew, as well as among themselves. Better to send a son to prison, one social reformer would write, than into the Navy of that time. It was that type of Navy that Mackenzie and other reformers were seeking to put an end to, with education, discipline, religious studies and personal cleanliness, as well as an end to “filthiness,” the term used in Somers’ log book for masturbating, and the frequent reason for floggings of the boys.

In the end, Spencer’s undoing was being on a ship too small for both the “base” son of a prominent man who Mackenzie strongly felt had squandered his social advantages, and Mackenzie, a self-made son of a working-class soap and candle merchant. Mackenzie had risen to his rank through his marriage into a prominent naval clan, engaged in a career as a writer of “witty” travelogues, and changed his name to inherit the fortune of a maternal uncle. Mocked, disobeyed and undermined by a 19-year-old who defied authority, and who was quietly his social “better,” Mackenzie, when confronted with a tale of Spencer confiding a secret plan to seize Somers and turn it into a pirate ship, at first could not believe the tale and then confronted the lad with a cold, increasing fury born of indignation and deep personal insult.

“It was but a joke,” Spencer averred, but as the captain noted, joking on a forbidden subject and one that could cost Spencer his life. John Canfield Spencer would later argue that this was the “heedless romance” of a school boy, not a capital crime. Seeing evidence of conspiracy all around him—Mackenzie believed Spencer had corrupted both some of his men and a number of the boys—Mackenzie hastily assembled a shipboard court martial and badgered his officers until they voted to convict Spencer and two other older men, Elisha Small and Samuel Cromwell, as leading conspirators, and then quickly hanged them.

The events on Somers inspired strong reactions, bitter arguments, and also led to Herman Melville, cousin of Mackenzie’s chief officer, Lt. Guert Gansevoort, to utilize Somers as the background of his novella, Billy Budd. The “Somers Mutiny” led the Navy to assign Somers to regular sea duty and in time to create the United States Naval Academy. Seemingly cursed and reputed to be haunted by the ghosts of the three hanged men, Somers sank in sudden gale off the coast of Mexico in 1846 with a number of the crew. While the story of the ill-fated cruise and the clash between Spencer and Mackenzie continually resurfaced in news stories and books for more than a century afterwards, it was a matter of professional courtesy that naval officers of the period never discussed the case. It became a forbidden, “secret” subject. Nonetheless, the story perseveres, because what is past is prologue, and as I assert in my book, the struggles and arguments of nineteenth-century America are not so distant or different from the America of the twenty-first century.

Featured image by Oscar Keys on Unsplash, public domain

Some premature gleanings

It is a bit too early for November gleanings, but on the other hand, before you can say Jack Robinson, everybody will be too busy to ask questions, and the questions will become stale. Therefore, I decided not to wait another week, let alone another four weeks, and discuss the notes and queries from my mail. As usual, I won’t comment on the remarks that contained no questions and will only express my gratitude to those who have read the posts, added their observations, or corrected my mistakes. Today, I am a bit out of my depth, with Sanskrit and Sumerian among the topics. But I regularly use Sanskrit for my etymology and tell the students who take my folklore and mythology courses about Gilgamesh, which I like very much and know well. Therefore, I risked answering even those questions but will be pleased to receive comment by real specialists in both areas.

English home and its Sanskrit lookalike ōm

Sanskrit OM

Sanskrit OM(Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

In the past, I have discussed the origin of both house and home (see “Our habitat: House” and “Our habitat: one more etymology brought ‘home’”). The question I received concerned the hypothesis that home might be a borrowing of Sanskrit om. In the old blog post, I tried to stay away from discussing the putative reconstructed forms: this is dry stuff, and few of our readers are interested in it. But to address the Sanskrit form, I must touch on Germanic and Indo-European prehistory. When it comes to Old Germanic, the most important recorded form is usually the one preserved in fourth-century Gothic. The Goths called home haims. Germanic h corresponds to non-Germanic k (compare English what, from hwæt [æ has the value of a in Modern English at] and Latin quod, that is, kwod). Thus, the Germanic so-called protoform began with k-. In the Slavic languages, Germanic h corresponded to s, rather than k: compare English hundred, Latin centum (pronounced as kentum), and Russian sto.The indubitable cognate of Gothic haims “home” is Russian sem’ia (stress on the last syllable) “family.”

The difference in meaning between “home” and “family” is of decisive importance for answering the question that inspired this discussion. However unclear the most ancient meaning of house might be, the word certainly designated some structure, but “home” refers not only to the building in which we live but also to its inhabitants. Home, sweet home does not mean “house, sweet house.” In Gothic, haims was declined differently in the singular and in the plural, and there is a rather telling parallel to this anomaly in Sanskrit. This anomaly has been explained in many ways. Most probably, a distinction was made between the place (“house”) and those who lived in it (“family”). The Modern English idiom out of house and home (especially in to eat someone out of house and home) may convey the same idea that was once expressed by grammatical means.

As regards Sanskrit, I can have no independent opinion and will only repeat what has been said by others, though some details about ōm (with long o, as in British English aw) are well-known even outside the narrow circle of sanskritologists. Ōm is the contraction of aum, with au being a true diphthong, as in English out. The sense of aum ~ ōm is very broad, one of the meanings being “universe.” “Universe” and “home” are not incompatible, but we would like to know which form Germanic speakers are supposed to have borrowed, in what environment, when, and where. In any case, the Indo-European form began with a consonant. Even Germanic h developed from kh, while the Sanskrit word never began with a guttural consonant. Therefore, with the information at my disposal, I fail to see the posited connection.

A minor universe?

A minor universe?(Photo by cottonbro studio, public domain)

In ancient Sumerian texts, the word “king” has been translated as “god.” Is this correct?

I am not sure which translation and which context are meant. In the translations of Gilgamesh I have consulted, “king” is not translated as “god.” To answer this question, I need a more definite context.

Kidney

Our correspondent writes: “Conventional explanations of the work kidney associated the second element with Middle English ey “egg” or Middle English nere “kidney” but do not endeavor to combine the two ideas. It long ago occurred to me that a plural kidn(e)ren might have been misconstrued as kidneyren and a new singular kidney formulated therefrom.”

Kidney, a word of contested etymology

Kidney, a word of contested etymology(Created by vectorportal.com, public domain)

See my old post“Are You of My Kidney?” for 11 April 2018. In it, I discuss the many problems connected with the etymology of this word. The trouble with “misinterpretation” is that it looks probable but cannot be “proved.” On the other hand, nothing in the history of this word can be demonstrated with certainty. Hard proof is in general a rare commodity in etymology. I can detect no fatal flaw in our reader’s hypothesis.

A question about two deceptively similar German words

German Landsmann is a person from the same land, while Landmann means “farmer, peasant.” The difference is rather old, but what is its origin? Everyone who has studied German knows how capricious compounds are: the connecting s is either present or absent for the reasons that cannot always be accounted for. Land– does very well without the connecting element (Landvolk “country people,” Landrat “an administrative body,” and so forth), and yet a meeting of all the citizens of a canton in Switzerland is called Landsgemeinde. Also compare Landwehr “territorial army” (without s) and Bundeswehr “army.” In any case, nouns with Land that refer to local institutions (like Landesbank “regional bank” and Landeshauptstadt “capital of a province”) more often have s, while when land means “soil” no s is present (Landhaus “country house” and the like). This vague rule may account for the difference between Landsmann and Landmann. The most detailed German grammars cite more or less intuitively justified lists of compounds with and without the connecting s and then add lists of exceptions.

German Schar “crowd, throng, horde,” used contemptuously by a great Middle High German poet, and British English slang shower “a group of worthless individuals.”

The question was whether the two words could be related. It is indeed amusing that shower fits that context so very well, but this is a coincidence. As usual with slang, its origin is hard to discover. The guesswork, like Eric Partridge’s suggestion that the source of this shower is shower of shit, is one of his nice fantasies, though the origin of shower (slang) in some phrase like shower of… is not improbable. I would look for some sexual hint here, but this is pure guesswork. In any case, English shower (slang) has nothing to do with German. The English word is not particularly old and must have native roots.

Spring showers bring questionable etymologies

Spring showers bring questionable etymologies(© Copyright Kenneth Mallard, via Geograph, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Usage: couple versus couple of

This is an old chestnut. No doubt, a couple of things is correct, while a couple things looks bare and even odd. Apparently, those who leave out the preposition treat a couple like any other numeral (two things, five things, etc.), though couple is a noun (compare a lot of things, a multitude of things, and so forth). But let me repeat what I always say on such occasions: any usage is correct that has become prevalent, let alone universal. If in the future, most people decide to leave out the preposition, this new norm will become correct, and editors will stop adding of. This is how language changes. To be part of this change is always heart-breaking.

Featured image: “Gilgamesh and Enkidu slaying Humbaba at the Cedar Forest“ by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

November 21, 2022

Boss Tweed and the “Forty Thieves” of New York City

Though tall and imposing—he would top more than 300 lbs.—William Magear Tweed could be a subtle charmer with a friendly smile, firm handshake, twinkling blue eyes, and an uncanny memory for faces and names. With the backing of the Democratic-controlled Tammany Hall, the former fireman won election to New York’s Common Council, taking his seat as an alderman in January 1852. There he started his education in patronage building. It got him what he wanted. For Tweed, money, not the civic good, was always the desired reward. The lessons he learned in the Common Council helped him establish his Tweed Ring, allowing that group to dominate New York’s politics and ravage the city’s treasury in the years after the Civil War.

The Common Council’s 20 Aldermen and 20 Assistant Aldermen had the power to appoint policemen and precinct commanders, judge criminal trials, and license saloons. Such responsibilities filled many of their pockets with kickbacks and bribes. And while not everyone in Tweed’s class of 1852 qualified as a grifter, the group ushered in the most corrupt council the city had ever seen. Their nefarious ways earned the aldermen the nickname the “Forty Thieves.”

Tweed boasted that he and his colleagues “know the virtue of a $50 bill when it is wisely employed, and the echo that it will produce.” And there was a vast and steady amount of money that could be had through appropriations and contracts for widening, paving, and extending streets; prison and school construction; streetcar and ferry franchises and selling real estate. Tweed served on the Law, Ferries and Repairs and Supplies committee and the Broadway Paving Committee, and with the help of his colleagues orchestrated shady land sales. When the city-owned Gansevoort Market—one of New York’s most valuable bits of land—went up for sale, bids came in for $225,000 and $300,000. The alderman, though, accepted an offer of $160,000, with the men earning between $40,000 to $75,000.

To receive the right to run ferry lines from New York to Brooklyn, applicants shelled out thousands of dollars in under-the-table payments in the hope of securing the deal. Railroad franchises for such throughfares as Third and Eighth Avenues were especially enticing. Most of all, the Forty Thieves salivated over the idea of a line along Broadway, the city’s most fashionable road. When lawyer Jake Sharp and others requested the right to run one, they offered a paltry $20 license fee per car. An overwhelming majority of the street’s landowners sought to squelch Sharp’s plan by making their own. Department store owner Alexander Stewart proposed a per-car license fee of up to $1,000 a year, while hotelier David Haight offered $10,000. Sharp, though, distributed bribes, and not surprisingly, Tweed and his colleagues granted him the franchise. When Stewart and others protested Sharp’s selection, Mayor Ambrose Kingsland vetoed the franchise.

Despite the setback, Tweed had his eyes on an even larger prize, winning a seat in congress. But Washington proved very different from New York. As a junior representative, Tweed possessed little power, could not finagle extra cash, and failed to be renominated. Back in the city he bided his time, and in 1855 received a spot on the Board of Education, where he raked in kickbacks from the sale of textbooks and on the purchase of furniture.

Then in 1857, the state legislature in Albany established a new Board of Supervisors. After the misdeeds of the Forty Thieves, the state hoped that the group would force good governance on local politicians by auditing expenditures and overseeing taxation and public improvements. Seeking fairness, Albany balanced the board’s makeup with six Democratic and six Republican representatives. Yet the parties filled the positions with loyalists like Tweed. When the board earned the power to pick election inspectors, Tweed used bribery to tilt the votes, and Democrats secured a say over 550 of the 609 slots, thus allowing them to decide election outcomes.

William Tweed would continue his climb to citywide power and wealth. He would take on such roles as Grand Sachem of Tammany, president of the Board of Supervisors, and chairman of the Democratic Central Committee of New York County. With so much control, he would become known as “Boss,” a title derived from the Dutch word bass for “master.” To consolidate his position, he formed his infamous ring with such like-minded cronies as Richard B. Connolly, A. Oakey Hall, and Peter B. Sweeny. The men orchestrated massive voter fraud, used patronage and bribery to sway judges, drained the city’s coffers, and made money through such shady deals as faked leases and selling overpriced products and services to the city. As commissioner of public works, Tweed oversaw street openings. This let them to know of development plans so they could buy up land where new streets and avenues were about to be created, thus allowing them to profit greatly.

What has become the most visible sign of Boss Tweed’s wicked ways sprouted in the early days of the Civil War. In December 1861, the cornerstone for the New York County Courthouse was laid on Chambers Street. The grand Italianate building took some two decades to complete, with Tweed purchasing a marble quarry in Massachusetts to supply a large share of the stone. As work progressed, nearly every contractor associated with its construction profited from inflated payments. All this ballooned the cost of what become infamously known as the Tweed Courthouse from the original $250,000 budget to some $12 million.

Many sought to end the control held by Tweed’s ring. In 1871, the New York Times published a series on the group’s malfeasance. Future governor Samuel Tilden, who served as chairman of the New York State Democratic Committee, started an investigation. And Harper’s Weekly political cartoonist Thomas Nast ran biting caricatures of Tweed and his friends. The Nast images especially irked Tweed who once exclaimed “Stop them damned pictures. I don’t care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures!”

All helped turn public opinion against Tweed and his ring. By then they had drained the city of between $30 million and $200 million. Sentenced for larceny and forgery, Tweed fled to Spain. There he was captured, partly because locals recognized him from Nast’s drawings. He would die in the Ludlow Street jail in April 1878 at age 55.

Feature image by Thomas Nast, published 1876, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

November 20, 2022

Salvator Mundi: the journey of a false saviour

Discovering the provenance of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi formed a significant part of the book that I co-authored with Margaret Dalivalle and Martin Kemp. Determining which records and references pertained to the original and which to the many copies and derivations of the painting required the unraveling of dozens of documentary threads, intertwined and occasionally knotted, stretching across the centuries.

While Leonardo’s original was the focus in the book, a look at one of the rejected threads can provide insight into the changing state of connoisseurship of the artist’s paintings, as well as the art market (and its occasionally hyperbolic promotional language) during the nineteenth century.

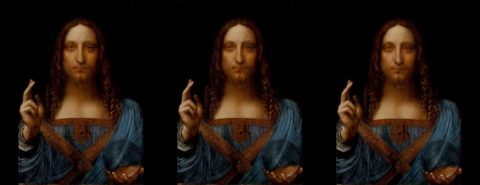

Left: Leonardo da Vinci: Salvator Mundi (Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia)

Left: Leonardo da Vinci: Salvator Mundi (Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia)Right: After Leonardo da Vinci: Salvator Mundi (Detroit Institute of Arts)

The earliest mention of the handsome Salvator Mundi now in the Detroit Institute of Arts was at a Christie’s auction on 16 June 1821, where it was described as follows:

L. Da Vinci, The Salvator Mundi—This rare and admirable performance of the great master was painted for Francis the First, and was formerly preserved in the Abbaye de St. Denys, near Paris.

Since it was widely known that Leonardo died at Francis I’s court in Amboise (legendarily in the King’s arms) while serving as his “first painter and engineer,” it would seem quite plausible that such a clearly devotional painting could have descended to the Cathedral of St-Denis, the traditional burial site of French royalty (including Francis I). The destruction and looting of the interior of St-Denis during the French Revolution, which had occurred less than 30 years prior to the auction, provided both an explanation for the painting’s appearance in London and perhaps an enticement for an opportunistic purchaser.

The cover of the sale catalogue described the consignor as “a well-known amateur, who has indulged his taste in collecting for a series of years, by selecting from the most distinguished cabinets offered in this country, besides purchasing abroad, and who is about to leave England for the Continent.” The catalogue further advises, “Many of these pictures have never before been seen in this country: among them … [in a larger font and all caps] “A SALVATOR MUNDI BY L. DA VINCI, A RARE AND PRECIOUS SPECIMEN OF THE HIGHEST MERIT.”

An annotated copy of the catalogue designates the “well-known amateur” as a Mr Parke—identifiable as John Parke, a celebrated oboist (1745-1829) and sometime dealer, truly a marchand amateur, who was a frequent buyer and seller at auction from the 1790s on. The painting was lot 63 in the sale and was “put up at 800 guineas,” according to the annotated catalogue, but was unsold. This was an extraordinary price, worthy of a Leonardo original, especially when compared with the top lot in the sale, Rembrandt’s Dismissal of Hagar, which sold for 105 guineas. (That painting, now considered to be from Rembrandt’s workshop, is in the Victoria & Albert Museum).

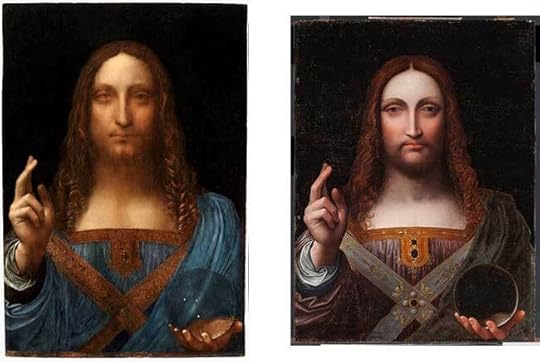

Thomas Hickey: Portrait of John Parke (London, Daniel Hunt Fine Art)

Thomas Hickey: Portrait of John Parke (London, Daniel Hunt Fine Art)We do not know whether John Parke in fact left for the Continent as advertised or whether the sale was a consequence of Parke’s indebtedness, which would lead to his imprisonment two years later in the Marshalsea, the notorious debtor’s prison in Southwark. In any case the painting remained in Parke’s possession, and following his death in 1829, it appeared in an 11 March 1835, auction at the “directions of the Executor of the late John Parke, Esq., of Dean-street.” The auction, by George Robins of Covent Garden, was advertised with a kind of timeless hype: the paintings offered were “reserved gems of the highly-gifted owner and which it had been intended should descend to posterity. Circumstances now direct their submitted, without the aid of any fancy or protecting price, to the liberal patronage of those who delight in the fine arts, and more especially that portion that prefer the old school.” Step right up, ladies and gentlemen!

The catalogue entry for the painting spared no praise:

Leonardo da Vinci, Head of Christ. The sublime aspect of the Saviour, so placid—so serene—and yet so firm in intellect, indeed with a mind more than human, yet compassionating human infirmities—superior to all, but disregarding none. These, as far as pencil can portray, Da Vinci has represented. The glass globe held in the Saviour’s hand, at once the emblem of universality, and of that mind to which the Universe itself is but a transparent bubble, is indeed a sublime idea, and the direct front view of the figure gives a majesty which proclaims the original far above human frailty. The coloring of this picture is so deep and rich, and yet so true to nature, that it leaves other works, even of the same artist, at an unreasonable distance; and the exquisite drawing and finish of every part place it among the most extraordinary performances in existence. This picture was in the collection of the King of France, at St. Denis, before the Revolution, and is carefully described in the catalogue now preserved in the French library. It was engraved by Hollar, and an impression (now very rare) is seen with the picture. The picture was purchased by Mr. Parke, in October 1826, from a French gentleman who then brought it from the Continent, and it has never before been offered for public sale.

While the entry added another inviting detail—that the work was that engraved by (Wenceslaus) Hollar, as the original indeed was—that information, like the fact that the painting had never been offered at auction before and that it was purchased in 1826 (we know that it was offered for sale five years earlier) was as false as the statement that there was no “protecting price”—that is, a reserve price—at the auction. All five paintings remained unsold.

They reappeared a year later at Christie’s (26 March 1836) but were withdrawn and re-offered on 7 May 1836, this time designated as the property of Henry Parke, John’s architect son, who had died in 1835. Henry began his career as a marine painter but is largely known as one of the principal draughtsmen in the employ of Sir John Soane. Again, none of the paintings sold, and we can only suspect that the family’s conviction that their Salvator Mundi was Leonardo’s original and deserving of a commensurate price (and auction reserve) was not shared by the collecting public.

The paintings presumably passed to Henry’s daughter Katherine Parke, but there is no further record of the Salvator Mundi until 1865, when it appeared in an auction of “pictures removed from Mr. Cox’s British Gallery”—a commercial art gallery operated for 40 years by William Cox. A notice sounding very much like an advertisement in the Pall-Mall Gazette of 11 December 1865, stated “Mr. Cox’s British Gallery in Pall-Mall, which is composed of the works of old masters and deceased British artists, and is one of the permanent attractions of the metropolis, will afford the curious visitor an hour’s special entertainment. Here he may find scarce works and early performances of distinguished painters; and many mature efforts of great power and renown. Some which have passed through many hands, and whose very history is romantic, may be seen in this collection.”

The sale, held by Foster on 13-14 December 1865, presented the Salvator Mundi as lot 107, described as by Leonardo da Vinci, with the following note:

From the Collection of Mr. Parkes [sic]. This Picture was procured from a French gentleman by Mr. Parke and remained in the possession of his heirs until purchased by Mr. Cox; it was bought in at a public auction in 1821 for 800 guineas. Engraved by Hollar, and mentioned in the Catalogue of the French Library as belonging to the Kings of France until the period of the Revolution in 1789. Size 26 ½ in. by 19.

An annotated copy of the catalogue states that the painting had sold for 100 guineas, but that seems to have been misdirection to obscure yet another auction failure, as the painting reappeared 24 years later at a Christie’s sale comprising paintings consigned by Mrs. Cox, presumably William’s widow. Lot 134 in the 6 April 1889 sale was simply listed without the earlier promotional persiflage: “L. Da Vinci…Salvator Mundi / From the Collection of Mr. Park [sic], 1821”). It was sold to a certain Dean or Deacon, who purchased the painting on behalf of the publisher and philanthropist James E. Scripps. The price paid was 62 guineas (£65-1), far from the 800 guinea reserve of 1821. By contrast the National Gallery had purchased Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks from the Earl of Suffolk for £9,000 in 1879, then the highest price paid for a work of art, even though occurring at a historic low point in the art market.

The British-born Scripps had moved to America at an early age, become a journalist and founded what was to become the Detroit News. His experience and travels, especially following a five-month trip through Europe in 1881, emboldened him to form a collection of representative Old Master paintings, which he would donate to the newly-formed Detroit Museum of Art (now Detroit Institute of Arts) in 1889. In the catalogue that Scripps himself wrote, and in subsequent museum catalogues, the Salvator Mundi was listed with pride but due caution as “attributed to Leonardo da Vinci.”

Later scholarly opinion placed the painting among Leonardo’s students and associates. Berenson attributed it to Marco d’Oggiono, then Giampietrino. Others have suggested Leonardo’s acolyte Salaì, though Giampietrino is most frequently cited as the painting’s author and is how the painting is currently catalogued by the museum. However, recent dating of the picture through analysis of the growth rings of its Baltic oak support (dendrochronology) have established that the earliest felling date of the tree from which it came was 1569, and the earliest likely date for the painting (following travel and seasoning) would be 1571—long after the demise of Giampietrino and Leonardo’s other students.

The precise repetition of several details from Leonardo’s painting in the Detroit Salvator Mundi suggests that its author had direct knowledge of the original—likely in France in the early seventeenth century. Still there remain evident compositional differences between the two: the later Christ has a fuller beard, normalized and symmetrized features, and changes in color and ornament to the costume that likely reflect contemporary stylistic and devotional preferences. While this Salvator may lack some of the power, aura, and subtlety of Leonardo’s painting, it retains a remarkable appeal, both as a reflection of the original and as an effective work of art. It is gratifying to know that after many years in storage at the Detroit Institute, this “rare and admirable performance” has recently returned to public view.

Discover more about Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi in this three-part blog series.

Featured image: The Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi LLC (used with permission)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers