Oxford University Press's Blog, page 64

November 6, 2022

The spell of spelling

English spelling can be endlessly frustrating. From its silent letters (could, stalk, salmon, February, and on and on) to its nonsensical rules (i before e except ….), to the pronunciation of ough (in cough, through, though, and thought). The messiness comes from layers of history, by way of the Anglo-Saxons and Norse and the French, with the help of Renaissance wordinistas and a slew of printers, typesetters, and spelling reformers. And from about 1400 to 1750, the Great Vowel Shift played musical chairs with the long vowels: the pronunciations shifted even though spellings were already locked into place.

It’s still possible to find some regularities: the silent e often signals the length of the vowel in a preceding syllable, yielding kit and kite, led and lede, fat and fate, dote and dot, cute and cut. Double vowels tend to be long as well: read and red, laid and lad, road and rod. But while it is important to understand the patterns of English spelling, we should celebrate some of the quirks and creativity of orthography.

In that spirit, here are five things about English spelling worth knowing.

1. Nouns used to be capitalized if a writer wanted to emphasize themTake a look at the Declaration of Independence, for example, which capitalizes Life, Liberty, and Happiness, among many other words. But the first-person I is the only pronoun we capitalize. Some people imagine that this capitalization is an act of self-importance. But the more likely explanation involves typography. The one-letter I developed from earlier ic or ich. When the consonants dropped away, the remaining letter was elongated to give it more visibility and eventually became a capital. It’s only egocentric after the fact.

2. Writers have endless license to add letters to intensify sound effectsA comic book KABOOOM has capitals, and a surplus of O’s to make for a big, loud sound. Similarly, an ooooh or wheee is a more intense exclamation that a mere ooh or whee. An ummm is more hesitant than an um, and an aah is a happier sound that ah. The more letters the more feeling. And don’t forget brrrr, zzzzz, and aaargh.

3. Rhetorical respellings can highlight a word’s intended effect in other ways as wellThe waggish respelling of ass-backwards as bass-ackwards reinforces the meaning of the term while also providing a bit of cover—a tiny bit—lest anyone be offended by the word ass. There are plenty of such rhetorical respellings from the political (the Yippie movement’s Amerika or feminists’ grrrl and womyn) to the commercial(Netflix, Kwik Kopy, eBay, or lite anything).

4. The apostrophe is more a matter of spelling than grammarLinguist Geoffrey Pullum considers the apostrophe the twenty-seventh letter of the English alphabet. We see this spelling function clearly in contractions and in eye dialect forms like goin’ and workin’, L’il Abner, ‘cause, and ‘nuff. When and is reduced to n sometimes only the first apostrophe is used and sometimes both are. The market Shop ‘n Kart in my town has a single apostrophe but gets points for wordplay since shop’n sounds like a reduction of shopping. Maybe they got the idea from Dunkin’ Donuts.

5. Finally, let’s celebrate the hyphenThat’s the mark used to indicate compounds. The rule for using hyphens with compound adjectives is straightforward (though not always observed): compound adjectives before a noun get the hyphen but after a verb they do not (so This is a fragrance-free building has the hyphen, but This building is fragrance free does not).

For compound nouns, the situation is more fluid. Just as spelling becomes simplified over time, compound nouns tend to lose their hyphens: bumblebee, crybaby, lowlife, and email. Some words resist the de-hyphenization, like ice cream and snow cone. But snowball has lost its hyphen as have most sports: baseball, football, basketball, even volleyball. Superman and Batman are hyphen-less but Spider-Man and Ant-Man have the hyphen. Iron Man has a hyphenless space.

Spelling can be frustrating. But for my money, the best way to approach it is to enjoy and explore its quirkiness. Let yourself fall under the spell of spelling.

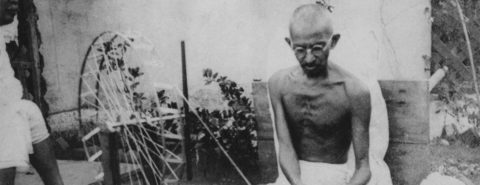

Gandhi weaves: lyrical beauty in Mahatma Gandhi’s writing

I have a favourite volume of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG): number 98, the Index of Subjects. I’ve made my way through it often over the past few years—sometimes purposefully; sometimes without an agenda—coming away more firmly convinced each time of one simple truth: Gandhi is the binary opposite of a monolith. No single story can ever contain the multitudes he was and continues to be to those of us who flock to him still. He retains the ability to surprise with the catholicity of his interests, and—to my mind, exquisite—ability to synthesise copious amounts of information and ideas gleaned with scant regard for trifles like academic disciplines or geographies.

To illustrate this, one example should suffice. While working on Walking from Dandi: In Search of Vikas, I spent some time with volume 98 when I was attempting to decipher the aesthetics of Gandhi’s walks. I started by reading through the entries under “art” (according to the CWMG, he doesn’t seem to have used the term “aesthetics”). The first entry under this heading—indexed perfectly as pertaining to art and “beauty”—fairly took my breath away. Now I’ve read my Gandhi: admired and argued in equal measure with the obduracy (and didactic albeit prophetic quality) of Hind Swaraj (1909/1910); read on in fascination as the page-turning entertainer that is Satyagraha in South Africa (1928) played itself out; walked with him in growing companionship through the aching honesty of the Autobiography, which I read in Mahadev Desai’s soaring translation (1929), and while I’ve always found his writing incredibly coherent and often inspired, I haven’t necessarily thought of it as lyrical. I realise now that this is because I had not known where to look for such a vein tapping into the sublime before I found the entry on art and/as “beauty.”

The setting is this: it is early 1925, and Gandhi is undertaking multiple “tours” around the Gujarat region. The following extract is from his “Notes” about a series of conferences he has recently attended around Vedchhi. He goes into what can only be described as raptures over the arrangements for the Kaliparaj Conference:

I cried out unwittingly: “I have seen many conferences, but in point of unstudied beauty, I have not seen one like this.”…It seemed as if nature herself had invisibly arranged everything. In my opinion, true art consists in learning from nature without struggling against it…Ordinarily a field is chosen as the site of the Conference. Our artists looked around and chose a spot which was filled with natural beauty. A river named Valmiki flows near Vedchhi. It dances along between rows of hills adorned by trees…The main rostrum was placed in the flowing water and, just as branches spring out of a tree, the seats for the delegates were arranged in front of the main rostrum. As it was winter, and, moreover, as the water was cool, this artistic expert argued that not only did the delegates not require any shade but the afternoon sun at 2.00 p.m. would be welcome to them, hence the golden sky provided the dome of the pavilion and the river sand, the seats…The canopy above the rostrum was made of bamboos and green leaves. A broad pathway led right up to the rostrum. Bamboos had been used for this purpose too and creepers of the arum plant had been entwined on the path. The first step leading to the rostrum was made of a sack filled with sand. There was not a single picture here and not a single strand of cotton was used for decorative purposes. One need not add that even decorations made of yarn cannot enhance the beauty of such a spot. Yarn is man-made and is in place in a house. Where the sky is the ceiling and sand the ground, only trees and leaves harmonize with the scene.

(CWMG 26: 41-42; emphases mine)

Who is this poet, even? There is nothing staid or inscrutable about the writer’s feelings. This passage is why, when I read about Gandhi (even as he was beautifully described as a proto-environmentalist) as being someone who was too “practical” to have the kind of feel for the natural world which marks the work of other writers who have thought closely about this earth, and all us upon it (Guha and Martinez-Alier make this argument in their seminal Environmentalism of the Poor), it struck me as sounding incomplete. It is true that Gandhi isn’t given to routine outbursts such as the one I cite above. But they are there, if we follow the strand that leads us from art as one node to nature as another, with beauty as the bridge that brings them into conversation.

In this conception, nature is not a background against which life is lived and conferences are organised; neither is it merely a “resource” to be extracted for human “use.” To read these downright poetic invocations is to trace the webs of Gandhi’s weaving. This we can do when the light catches these seemingly diaphanous motifs just so, stretching out in the form of volume 98, for example. They are how we get from Henry Salt (proponent of animal rights and ethical vegetarianism who befriended Gandhi as a young student in London) to Dandi; from Ruskin—whose Unto This Last was fundamental to Gandhi’s conception of the self-sustaining social unit—to Sabarmati ashram; the Bible to the Gita; and, “true music” being implicit in “khadi and the spinning wheel,” which Gandhi said in a speech for the National Music Association in 1926. They are how we learn that there is also music in walking, and that to walk is to think and en-act change which can only come from “turning the searchlight inward” (the title—and thrust—of one of Gandhi’s most evocative Dandi March speeches in 1930)—for what is the worth of “raj” of any kind without the necessity of owning up to the self-reflexive “swa” prefacing it? There is music in his swaraj, and this is what it sounds like.

Anyone who would walk with the old man awhile would do well to play with Volume 98. What is uncertain is where you’ll go. Or how you’ll get there. But wander yet, for there are to be found here domes of golden skies, and if you’re lucky, trees and leaves harmonizing with the scene, reminding us to tread lightly upon this earth, and bidding us that we calibrate anew our relationship with kin, in all forms of life.

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

November 5, 2022

Five tips to improve your research culture

With principal investigators facing work, life, mental health and career challenges, time is often a limiting factor. But creating a healthy environment helps all achieve and feel well.

A typical principal investigator (PI) must overcome many challenges and has a great deal to learn. The experience was accurately portrayed in a recent Twitter post with the caption “Transitioning from a post-doc fellowship to PI of a lab…” In it, the “PI” sets off across a muddy terrain to reach a stable foothold with unexpected and humorous results. Reading the comments, the clip appears to resonate well with academics and researchers alike.

The example reflects other transitions as well, including tenure, promotion, and taking on further organizational and research leadership responsibilities. On top of balancing various roles, along with one’s health and wellbeing, PIs must regularly figure out what research questions to pursue, how to win highly competitive funding, and manage their research career, as well as how to build and sustain a healthy team. There is a growing need to support and equip researchers with skills to shape their environments.

At the heart of this challenge is research culture and team leadership. Research culture encompasses the behaviours, values, expectations, attitudes, and norms of a given community. Culture emerges from many factors: past history, explicit and implicit expectations, values and cultural norms as well as the relational dynamics and power systems. That said, each individual can and does impact their culture in subtle and overt ways. If we want to create a research ecosystem that is diverse, healthy, and more inclusive, we must recognize that every person in research can make a positive difference.

Lately, funders and policy makers are paying increasing attention to this agenda. Principal investigators are well placed to help and have much to gain from it. If you are on your way to being a PI or already in the role, the five practical tips below will help you reflect on, explore, and begin to proactively manage a healthier research culture.

Five practical tips for a healthier research culture1. Get curious about the research culture you have now“If we want to create a research ecosystem that is diverse, healthy, and more inclusive, we must recognize that every person in research can make a positive difference.”

Imagine an unexpected visitor staying in your group for a week. What would this person see? For example, what is the nature of interactions between different members of your group? What is and isn’t talked about? What tends to get rewarded and celebrated? Who succeeds here and who tends to struggle? How is help given? How are errors and learning shared? Are people tense or on edge? When a junior researcher speaks or presents their work, do senior researchers show up and listen? Your answers to these questions will help reveal more about the culture you have. From this place, you can more easily consider what would be the best scenario and how to bridge the current set up with this vision.

2. Establish your key valuesWhat makes values so useful is that they guide behaviour and culture. For example, if a given team values results, some people may interpret this to mean “results at all cost.” But when we value teamwork and results, the way we get to the finish line matters. Decide on a small number of values that are key to your team’s collective and individual success and wellbeing. Consult your team. Here are some ideas for what could be valued: trust, honesty, excellence, teamwork, healthy debate, or even conflict that is effectively resolved. Talk about your values with the team and use them to guide how everyone works and behaves.

3. Focus on fostering good communicationResults have inherent value but sometimes they can come at a cost. This could be health, well-being, work quality, motivation, and teamwork. Pay special attention to how you and others communicate. How are people supported and guided? What happens if someone does something wrong? Is everyone invited to speak and is their view fully considered? Is there enough compassion and healthy curiosity in the system? How is conflict handled and resolved? What sort of career support can one expect to receive at the start, mid-way through and towards one’s next career step?

One of the most practical ways to improve communications is by asking people about what they need, how they feel, what they notice, and what would be better. Your job as a leader is to open and guide these conversations. Sharing your views is important but their greatest effect often comes when they are shared at the end of these conversations, along with a mutually agreed action plan.

4. Major in curiosity over criticismAvoid confusing rigour with criticism however much you intend to help. Uninvited negative evaluation risks damaging people’s confidence, motivation, and morale. This can quickly turn a healthy culture into one where fear inhibits everyone’s full potential. To counter this, adopt the following positive intention when speaking with others and holding meetings: “I am here to discover and learn.” Seek to first understand rather than jump to premature conclusions. Treat conversations as a worthwhile time investment as clear, mutual understanding is foundational to healthy results and relationships.

5. Celebrate and be curious about differenceOne of the best way to nurture and support diversity is to be curious and welcome difference. If you speak less and inquire about other people’s experience, needs, and desires, you will be better placed to ensure everyone’s success. Along the way you will develop genuine trust and respect and inspire others to follow your lead. The possibility to make this better exists in every interaction with much room to get things wrong and learn. Through conscious positive intention, regular reflection. and feedback, you will create the sort of culture that delivers top results and where everyone thrives.

Is all this worth it? Absolutely!

The ideas here can be worked into one-to-one meetings, regular group discussions, annual retreats, and appraisals, as well as countless informal interactions. Start small and you will feel and notice a big difference in little time. Your team and visitors will too.

Referencesshow moreCanti, L et al. Research culture: science from bench to society. Biology open vol. 10, 8 (2021).Kwok, R. How lab heads can learn to lead. Nature 557, 457-459 (2018).Maestre, F. T. Ten simple rules towards healthier research labs. PLOS Computational Biology, 15 (4), (2019).Notman, N and Woolston, C. Fifteen to one: how many applications it can take to land a single academic job offer. Nature 584, 315 (2020).Rossi, L. I felt overwhelmed as a new professor—until I hired a personal coach. Science, 373, 1546 (2021). Smith, D. K. The race to the bottom and the route to the top. Nat. Chem. 12, 101–103 (2020). Van Noorden, R. Some hard numbers on science’s leadership problems. Nature 557, 294–296 (2018).Woolston, C. The scientific workplace in 2021. Nature 600, 765-766 (2021).show less

November 4, 2022

When can you refuse to rescue?

You can save a stranger’s life. Right now, you can open a new tab in your internet browser and donate to a charity that reliably saves the lives of people living in extreme poverty. Don’t have the money? Don’t worry—you can give your time instead. You can volunteer, organize a fundraiser, or earn money to donate. Be it using money or time, there are actions you can take now that will save lives. And it’s not just now. You can expect to face such opportunities to help strangers pretty much constantly over the remainder of your life.

I doubt you are morally required to help distant strangers at every opportunity, taking breaks only for food and sleep. Helping that much would be enormously costly. It would involve a lifetime of sacrificing your well-being, freedom, relationships, and personal projects. But even if you are not required to go that far, surely there are some significant costs you are required to incur over the course of your life, to prevent serious harms to strangers.

For starters, you are morally required to rescue a stranger drowning right in front of you, even if it involves a significant sacrifice of money or time. Rescuing distant strangers by donating to charity is different in several ways: the strangers are far away, you can’t see them, and many others can help them. But none of these differences precludes a moral requirement to aid distant strangers. Consider an imaginary case in which someone is drowning thousands of miles away. While you cannot see them, you have excellent evidence that you can save them by pressing a button that would instantly put a lifebuoy within their reach. Many others can help, including governments who are both morally and legally required to rescue those imperilled on their territories. However, you’re confident they will not help, even if you try to get them to. In this imaginary case, it still seems you are morally required to press the button, even if it involves a significant sacrifice of money or time.

“At what point are you morally permitted to refuse to rescue distant strangers?”

Next suppose we add to this imaginary case that you’ll face an indefinite sequence of opportunities of this sort. Once an hour, you will face another opportunity to save another distant drowning stranger by pressing the button once more, each hour at the cost of a bit more money or time. Now it seems that, even if the cost you’d incur on each occasion is slight, you’re not morally required to help on each occasion. The total cost over the course of your life would be enormous. But even if you are not required to incur an enormous lifetime cost, there are still some significant costs you are required to incur in responding to opportunities to prevent serious harms to strangers, whether they are near or far.

At what point are you morally permitted to refuse to rescue distant strangers? How much must you give over the course of your life? These are extremely difficult questions. First, what you are required to give depends on what you have. Those with plenty of resources and well-being can be required to incur greater costs over their lives than those with little. Second, even holding fixed one’s resources and well-being, it is unclear where to draw the line: you’re required to sacrifice an hour to save a life, but you’re not required to sacrifice a decade—where’s the cutoff in between?

“How much must you give over the course of your life?”

In chapter six of my book The Rules of Rescue, I explore the surprisingly neglected question of when you are required to help. Existing literature tends to focus on how much you are required to help. For example, suppose that you’re required to use at least roughly 10% of your lifetime resources (money and time) helping distant strangers. But does this mean you must spend the first several years of your adult life saving strangers, taking breaks only for food and sleep, until you’ve reached the 10% mark? Presumably not. According to a more promising interpretation of this lifetime requirement, it is permissible not to help on any given occasion if it remains possible for you to give 10%. But what if you are quite unsure whether you will help enough later, if you don’t start helping now? It is plausible that a morally decent person would help now rather than delaying. I would argue that you are permitted not to incur a cost in helping now, if you reasonably expect you’ll have incurred a great enough lifetime cost in helping others. At least, under these conditions you needn’t incur a cost now to act as a morally decent person would.

This invites further questions. What if you’re a saint in your 20s, sacrificing and helping much more than you could be required to do over the course of your life? It may seem implausible that you could then spend the rest of your life chilled out sipping margaritas. Moreover, even if charitable giving is like the drowning stranger case in that each situation can generate requirements to aid strangers, might there still be morally relevant differences? Can you permissibly let a stranger drown right in front of you, whenever you reasonably expect that you’ll have incurred a great enough lifetime cost in helping others? Imagine telling a drowning stranger that you’re giving so much money and time to charity already that you refuse to incur the small additional cost of saving their life. Most of us share the intuition that this is morally different from the case of refusing to give more to charity. But is this intuition rationally defensible?

I look at these questions and more in chapter six of my book. Other chapters explore such topics as: requirements to help more people rather than fewer, the praiseworthiness of altruism, special connections to those we can help, and whether we’re morally required to be effective altruists. The book is open access, and a PDF will be freely available upon its release this winter.

Featured image by Gábor Kulcsár on Unsplash, public domain

November 3, 2022

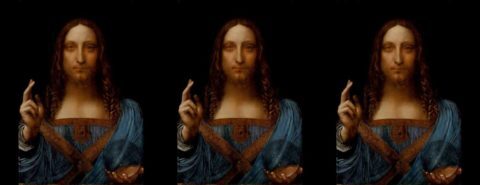

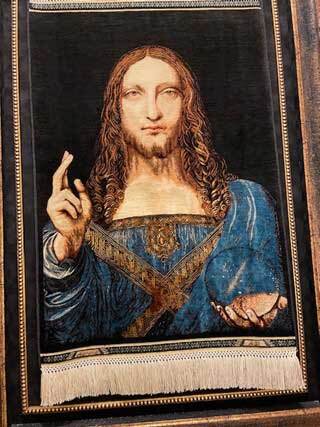

Salvator Mundi: poor picture, poor Leonardo

What does “SM” stand for in the context of Leonardo da Vinci? The obvious answer is the $450 million painting of the frontal Salvator blessing with one hand while the other cradles a rock-crystal sphere of the mundus (actually the cosmos rather than the customary globe). In reality, as happens with Leonardo’s productions, our visual engagement with the painting has been skewed by fictionalised stories, lurid journalism, and attributional vitriol. For me, SM now stands for “Sensationalised Mess.” How the painting actually works as a devotional image, what it means, and how it embodies Leonardo’s science and art have become lost.

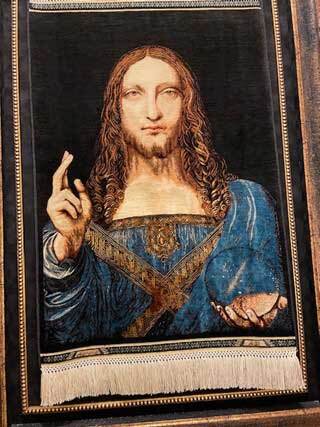

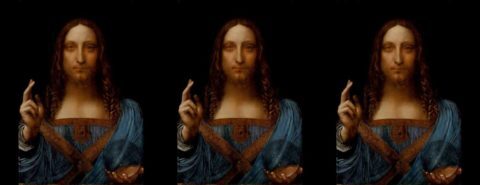

It is beginning to be appropriated in the public mind alongside the Mona Lisa. It is remarkable how far in the few years since its sale it has caught up on that most iconic of portraits. Humorous and pious rip-offs appear in increasing numbers, bearing witness to the power of the image. There is a lot of merchandise. We find it featuring impressively on an Anatolian rug, and for those with deeper pockets a micro-mosaic version is available for €180,000!

The Salvator Tapeti

The Salvator Tapeti(Courtesy of Bazar 54)

Of the filmed and TV productions, pride of place goes to Andreas Koefoed’s stylish The Lost Leonardo. It begins and continues with cleverly staged shots, not least of mysterious interiors, often damp and penumbral, featuring grotesque figures from the art world, self-caricatured even beyond Daumier’s imagination. The star ego is that of Jerry Saltz, who declares triumphantly that all the known Leonardo’s are “heavily documented.” This is spectacularly untrue. We only need think of the Munich Madonna, which came into the Museum off the streets and was initially thought be by Verrocchio. Later in the film, Saltz brandishes a stiff rod to beat a reproduction of the Salvator in an act of ugly theatre, shouting that it is a “marked-up piece of junk.” I was astonished to discover he is a prize-winning critic.

Andreas’s film is populated by clusters of monster egos, a good number of whom attribute the present appearance of the picture to Dianne Modestini, the conservator who diplomatically ensured that areas of paint loss did not destroy the effect of the picture. “Most of the painting is re-made”—or variations of this claim—emerge repeatedly through ignorant mouths. In reality it is less “re-made” than the Last Supper.

Not the least bizarre figure is that of Yves Bouvier, maestro of free-ports (taxation-free havens for “investments”), whose self-confessed bending of the truth when he sold the painting to Dmitri Ryboloflev with a $ 47.5 million markup, is matched by his skills on a monocycle.

It is news when a loud-mouth can claim that the world’s most expensive picture is not by the master. It is news when it is seemingly in the luxury liner of a mega-rich Arab. It is not news when Leonardo’s authorship is recognised with rational arguments. Not much prominence was given to the scientific examinations conducted for the Louvre in advance of the great exhibition in Paris. This evidence is presented in an impressive book printed for the Louvre but not officially released when the museum failed to borrow the Salvator. I have a PDF of this rarest book, in which the director, Jean-Luc Martinez, declares unequivocally that the Salvator Mundi, from the former Cook collection and now owned by the Ministry of Culture of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, was studied by the museum and C2RMF in 2018. The results of the historical and scientific study presented in this book fully confirm the attribution of the work to Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo’s picture continues to stray beyond the media devoted to the arts. Not the least of the stories is the continuing court case that pits Rybolovlev against Bouvier. The dealer-cum-free-porter, Bouvier, seems to thinks that all is fair in love and the art jungle. His Russian customer believes he has been taken for an illegal ride.

Perhaps the most important question is the current whereabouts of the painting. The statement by Martinez seems to be true, and it is likely that the masterpiece will be housed in a Saudi museum within the next two years.

My overwhelming feeling is “poor picture.” It deserves better.

Featured image: The Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci

Salvatore Mundi: poor picture, poor Leonardo

What does “SM” stand for in the context of Leonardo da Vinci? The obvious answer is the $450 million painting of the frontal Salvator blessing with one hand while the other cradles a rock-crystal sphere of the mundus (actually the cosmos rather than the customary globe). In reality, as happens with Leonardo’s productions, our visual engagement with the painting has been skewed by fictionalised stories, lurid journalism, and attributional vitriol. For me, SM now stands for “Sensationalised Mess.” How the painting actually works as a devotional image, what it means, and how it embodies Leonardo’s science and art have become lost.

It is beginning to be appropriated in the public mind alongside the Mona Lisa. It is remarkable how far in the few years since its sale it has caught up on that most iconic of portraits. Humorous and pious rip-offs appear in increasing numbers, bearing witness to the power of the image. There is a lot of merchandise. We find it featuring impressively on an Anatolian rug, and for those with deeper pockets a micro-mosaic version is available for €180,000!

The Salvator Tapeti

The Salvator Tapeti(Courtesy of Bazar 54)

Of the filmed and TV productions, pride of place goes to Andreas Koefoed’s stylish The Lost Leonardo. It begins and continues with cleverly staged shots, not least of mysterious interiors, often damp and penumbral, featuring grotesque figures from the art world, self-caricatured even beyond Daumier’s imagination. The star ego is that of Jerry Saltz, who declares triumphantly that all the known Leonardo’s are “heavily documented.” This is spectacularly untrue. We only need think of the Munich Madonna, which came into the Museum off the streets and was initially thought be by Verrocchio. Later in the film, Saltz brandishes a stiff rod to beat a reproduction of the Salvator in an act of ugly theatre, shouting that it is a “marked-up piece of junk.” I was astonished to discover he is a prize-winning critic.

Andreas’s film is populated by clusters of monster egos, a good number of whom attribute the present appearance of the picture to Dianne Modestini, the conservator who diplomatically ensured that areas of paint loss did not destroy the effect of the picture. “Most of the painting is re-made”—or variations of this claim—emerge repeatedly through ignorant mouths. In reality it is less “re-made” than the Last Supper.

Not the least bizarre figure is that of Yves Bouvier, maestro of free-ports (taxation-free havens for “investments”), whose self-confessed bending of the truth when he sold the painting to Dmitri Ryboloflev with a $ 47.5 million markup, is matched by his skills on a monocycle.

It is news when a loud-mouth can claim that the world’s most expensive picture is not by the master. It is news when it is seemingly in the luxury liner of a mega-rich Arab. It is not news when Leonardo’s authorship is recognised with rational arguments. Not much prominence was given to the scientific examinations conducted for the Louvre in advance of the great exhibition in Paris. This evidence is presented in an impressive book printed for the Louvre but not officially released when the museum failed to borrow the Salvator. I have a PDF of this rarest book, in which the director, Jean-Luc Martinez, declares unequivocally that the Salvator Mundi, from the former Cook collection and now owned by the Ministry of Culture of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, was studied by the museum and C2RMF in 2018. The results of the historical and scientific study presented in this book fully confirm the attribution of the work to Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo’s picture continues to stray beyond the media devoted to the arts. Not the least of the stories is the continuing court case that pits Rybolovlev against Bouvier. The dealer-cum-free-porter, Bouvier, seems to thinks that all is fair in love and the art jungle. His Russian customer believes he has been taken for an illegal ride.

Perhaps the most important question is the current whereabouts of the painting. The statement by Martinez seems to be true, and it is likely that the masterpiece will be housed in a Saudi museum within the next two years.

My overwhelming feeling is “poor picture.” It deserves better.

Featured image: The Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci

November 2, 2022

Interview with Dr Molly Morgan Jones, Director of Policy at the British Academy on SHAPE

At OUP, we are the largest university press publisher of SHAPE (Sciences, Humanities, and the Arts for People and the Economy) disciplines. Back in 2021, we joined the SHAPE initiative along with the British Academy, LSE, the Arts Council, and other key partners to show our support and advocacy for these vitally important areas of research and scholarship.

We recently caught up with Dr Molly Morgan Jones, Director of Policy at the British Academy, to find out more about the future of the programme and to hear why she believes SHAPE must be considered in alignment with STEM to further society.

What is your role at the British Academy and your involvement in SHAPE?I head up the Academy’s policy programmes. Through our policy work, we mobilise SHAPE research from across the sector and bring rigorous, authoritative, and independent perspectives to the major policy challenges facing us globally, nationally, and locally—be it reaching our net zero targets or how to harness the power of all disciplines to achieve economic growth. I was involved early on in SHAPE, which was borne from a group of us who wanted to try to develop a stronger and more coherent narrative for the disciplines at a time when there was increased negative rhetoric (the phrase “dead-end” courses used by some in Government at the time) and what seemed to be a low understanding of the contribution of our disciplines to the major societal and economic challenges of the day.

This is all despite our services-driven economy here in the UK and the ever-growing success of industries such as the creative sector. It seemed “science” was increasingly used in a narrow sense and however much we were reassured it was science in the German sense of wissenschaft, it was evident that science was increasingly becoming the shorthand for STEM and we wanted to try to change that in a positive way.

Why did the British Academy launch the SHAPE initiative and why does it continue to support SHAPE?“For me, the principles of SHAPE and STEM working together to foster deeper meaning and understanding for society and for human culture are just in my DNA.”

We hadn’t intended to develop an acronym but felt that it seemed to work when the idea came to us—it’s a verb and a noun so wonderfully flexible and reflects what we do. It’s an inspiring word, more so than previous efforts such as HASS, SSAH, or STEAM where Arts is just shoe-horned in the middle. And it complements STEM and I think the two together paint a wonderful picture of how they can both work so nicely together, which is exactly what the disciplines do every day out in the world. It also enables storytelling, which is important for our disciplines as so often the data doesn’t tell the full picture.

For example, the data that shows where graduates end up after leaving university doesn’t show that over time SHAPE graduates tend to be able to be more flexible and resilient in their career choices in response to a dynamic economy. It also doesn’t show that out of the 10 fastest growing sectors in the UK economy, eight employ more SHAPE graduates than STEM. Our new SHAPE Skills at Work report brings this data to life and features a series of case studies of how graduates with a SHAPE degree are adding value to society and different sectors in a variety of ways.

What are your plans to further activate the initiative? How do you envision organizations such as OUP continuing to support SHAPE?The acronym is really the vehicle—what is crucial is getting the underpinning evidence base right and the overall narrative. That’s where my team come in. We have launched and will be further developing the SHAPE Observatory over the course of this year. Through this evidence hub, we will help to play a co-ordinating role in gathering the evidence and narratives and monitoring the health of the disciplines, making this available for others to use. We are also working on a more proactive stream of work that we are bringing together under the banner of a SHAPE Vision for 2030. With programmes of work looking at the people, principles, and place-based aspects of the research and higher education system, we hope to bring all of this together to help co-create a more strategic vision for the role of our subjects in society and their place in the research and innovation ecosystem.

The Academy is also using SHAPE now as the default term for our disciplines in the hope that others will do so too. We were pleased that SHAPE got its first mention in parliament last year and has its own Wikipedia page. Anyone and everyone should use the name. No one owns it.

“We want everyone in the community to feel they can use SHAPE in ways that work for them to celebrate and champion our subjects.”

As the largest university press publisher of SHAPE disciplines and one of the founding signatories, we are of course pleased to have OUP onboard not only through the promotion of the initiative but through real action in publishing cutting-edge research in the humanities and social sciences. We want everyone in the community to feel they can use SHAPE in ways that work for them to celebrate and champion our subjects.

Could you tell us in your own words why you think SHAPE subjects are important and what the initiative means to you personally?I did a biology degree at university and although I love the actual science, I have always been more drawn to understanding how science interacts with society in wider ways. For me, the principles of SHAPE and STEM working together to foster deeper meaning and understanding for society and for human culture are just in my DNA, so to speak. It’s part of how I have always approached my own learning, my own thinking, and my own career. We need engineers to build a bridge, but why are we building a bridge in the first place? To connect ourselves as human beings. Economic growth and prosperity need all the disciplines working together and if we are successful in getting this recognised in policy audiences and in the sector, I think we will be all the stronger for it.

Featured image by Silas Baisch on Unsplash, public domain

In one’s stockinged feet

This is a story of the word stocking. Silk stocking districts, bluestockings, and Christmas stockings will not interest us today. Stockings, just plain stockings, Sir, as one of Dickens’s characters might say. One does not need to be an etymologist to suggest that stocking consists of stock- and –ing. The trouble is that though –ing occurs in some nouns (for instance, in offing and inkling), it looks odd in stocking (compare some phrase like stocking the cupboard with food, where it seems to be perfectly in place). Also, few English words have more seemingly incompatible senses than stock. Our great authority and the author of the ever-green English etymological dictionary Walter W. Skeat made short shrift of that variety. He wrote (so in the latest Concise version): “The old sense was a ‘stump; hence a post, trunk, stem, a fixed store, fund, capital, cattle, stalk, butt-end of a gun, &c.” It is the &c. that looks especially troublesome. For example, in the etc. region, we find a flower called “stock.” The flower is beautiful but not particularly “stocky.” Even the path from “stump” to “fund, capital” is far from trivial. Stock means “stick, staff” and is related to German Stück “piece” and its cognates elsewhere in Germanic. The proliferation of senses in such an outwardly simple noun may be left for another occasion. We only wonder how stocking got its name.

This is the flower called “stock.” Does anyone know the origin of the name?

This is the flower called “stock.” Does anyone know the origin of the name?(Photo by wildfeuer via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

It is possible to begin from afar and, in search of clues and analogs, look at the history of the word hose. To modern speakers the most predictable image hose evokes is one of a water pipe, but a hosier does not deal in pipes! That person’s merchandise consists of things known commercially as legwear, and indeed, German Hosen (plural) means “trousers, breeches,” while the singular form Hose refers not to a trouser leg but rather to what we today call “stocking.” Stockings, as we know them, are a late invention. In the past, men also wore some sort of tights or pantyhose, that is, a single piece, and it is no wonder that the word stocking, which refers to a separate article of clothing, emerged in English relatively late, namely, at the end of the sixteenth century. I have a quotation, whose source is not given in my source, but it looks genuine: “…our knit silke stokes and Spanish leather shoes.” We note: stokes, not stockings.

Apparently, stockings were first called just stocks, and that is why the suffix –ing in the modern word is puzzling. In older texts, –ing alternates with –in, but this –in does not look like a familiar phonetic variant of –ing, as in I am comin’ and so forth. More likely, there was an adjective stocken (with the same suffix as in woolen and silken), misunderstood as or confused with the present participle stockin’. This is my guess. Yet similar substitutions sometimes occur with other endings. For instance, the adjective stubborn may go back to stubbing. Though such a form has not been recorded, the Icelandic cognate of stubborn (the only one that exists) ends in –inn (English –orn remains a riddle). Other than that, –in and –ing once varied in many words and today occur in nouns, obviously not connected with any verb (cf. shilling and farthing).

A trunk hose in its untruncated glory.

A trunk hose in its untruncated glory.(Image: “Sir Walter Ralegh”, National Portrait Gallery, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Amid all this uncertainty, one thing arouses no doubts: stocking has the root stock “trunk, stem, stump.” A telling parallel is German Strumpf “stocking,” in some way related to the adjective stumpf “blunt,” an unquestionable cognate of English stump. The earliest meaning of Strumpf was indeed “stump.” A stocking and a trouser leg evoked associations with a stick, truncated tree, and the like. The English word trunk hose (trunk-!) makes the association between a stocking or a trouser leg with a stump especially clear.

I am quoting part of the definition of trunk hose from The Century Dictionary: “Properly, that part of the hose which covered the trunk or body, as distinguished from those parts which covered the limbs….” This is the comment by Ernest Weekley: “Professor Skeat suggests ‘trunked (i.e. truncated) hose’. The use of stock, stocking, and German Strumpf, all meaning properly ‘stump’, ‘trunk’, suggests that trunk hose is a similar formation.” Trunk was borrowed from French, but we are interested in the imagery, rather than the source of the word, and in our attempt to understand the imagery behind stocking, the word trunk hose looks as though it has been made to order. There is even no need to refer to truncate or truncated here.

Stockings were such a noticeable innovation that, for example, the Russian name of this article of apparel (chulók) was borrowed from the East. By contrast, socks have been known since very old times. In Old English, the word meant “light shoe” (!). Yet even sock traveled to the Germanic languages (and to the Celts) from Greek via Latin. (This may be the right place to note that words related to clothes travel easily all over the world, change along the way, become domesticated, but often hopelessly opaque from an etymological point of view. Incidentally, one of such words is shoe.) The distant source of sock has no recoverable etymology and may too have been a borrowing from some Oriental language. The suggestion sounds reasonable. Since the shoes known as socks were often made of cloth, the name was easy to transfer to what we today do call socks.

Buskin: neither bus nor kin. An almost forgotten object and an almost forgotten word.

Buskin: neither bus nor kin. An almost forgotten object and an almost forgotten word.(Image by Pearson Scott Foresman, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The Greek word, whatever its origin, became widely known, because comedians wore socks, unlike tragic actors, whose boots (buskins) were known as cothurni. I am pleased to add that buskin is a word “of much disputed origin.” As emphasized above, article of clothes and their names travel freely from land to land. Those who would like to harvest something on native soil, may find solace in the fact that the idiom to blow (knock) one’s socks off “to perform an astonishing feat” was coined in the American south and has a possible pugilistic origin. It was apparently known as early as the middle of the nineteenth century but suddenly became popular (read: overused) in the 1980s and soon traveled overseas.

Such is the unfinished history of the word stocking, with a few thoughts on the origin of sock, thrown in for good measure.

Featured image: Paolo da Visso – The front of a cassone with three scenes from Boccaccio’s Teseida (1440), by cea+ via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

November 1, 2022

Is publishing sustainable?

What do you picture when you think of academic research? You might imagine an academic sifting through a pile of hefty books in a university library, looking for the evidence they need to unlock their argument. The shift towards digital content means this picture is changing.

Increasingly, researchers no longer need to leaf through books to find the information they need—it’s easily accessible from anywhere in the world at the click of a mouse. Significantly, this shift towards digital also brings environmental benefits that will help to reduce publishing’s contribution to the climate and nature emergencies.

How does print publishing impact the environment?Printing books consumes Earth’s natural resources—wood pulp, water, and fossil fuels, to mention a few. Available data indicate that the production of printed publications accounts for around three-quarters of OUP’s carbon footprint, with nearly half coming from the forestry and mill operations needed to produce paper alone.

Wood pulp, for making paper, board for book covers, and packaging, comes from forests in countries ranging from Brazil to Finland. Commercial forestry for timber and pulp contributes to deforestation and forest degradation, a leading driver of biodiversity loss that also accounts for around a tenth of global greenhouse gas emissions. Publishers can reduce their impact by sourcing certified sustainable paper.

Agricultural products often have a high impact on the natural world. Land use change for soy cultivation, which is used in the production of vegetable-based inks, is a major cause of deforestation. However, it is worth noting that most soy is used for cattle feed and biofuels, and that vegetable-based inks are deemed better for the environmental than petroleum-based inks.

Water: depending on the mill, it can take up to 13 litres of water to produce a single sheet of paper. Impact on the local environment and communities varies according to the degree of climate and water risk where the mill or printer is located. India, for example, generally has a higher water risk than Scandinavia.

Metals, including aluminium to produce printing plates and gold and copper for foil stamping, are currently required in print publishing. Mining for metals causes biodiversity loss, soil erosion, and contamination of water and soil.

Fossil fuels, currently essential for most mill and printing operations, as well as for product transport, cause climate change. As we are now all too aware, the burning of fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases which trap heat in the Earth’s atmosphere, driving up temperatures and disrupting the balance of ecosystems worldwide.

What is OUP doing to make print publishing more sustainable?At OUP we have set three initial sustainability targets to be achieved by 2025:

1. Carbon neutrality from our operationsOur initial focus is on reducing energy use at our office and warehouse facilities, as well as business travel, however we are also making plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from our upstream paper, printing, and freight supply chain.

One of the most impactful things we can do is to reduce print volumes. Doing this while continuing to deliver world-class academic and educational content will require us to change the way we do business—for example, by using print-on-demand to cut wastage from over-ordering and by switching to digital where appropriate.

2. 100% certified sustainable paperAs well as being the main driver of a publisher’s carbon footprint, paper use is the publishing industry’s biggest impact on biodiversity through deforestation. Anything we can do to source paper more responsibly will be of huge benefit to the natural world. OUP is proud to have set a target to use 100% certified sustainable paper by 2025 and, as members of the Book Chain Project industry collaboration, we will be making use of newly available tools to better understand the biodiversity impact of paper-sourcing decisions. We are also supporting Book Chain Project research into the comparative environmental impacts, including carbon footprints, of different paper types.

3. Zero waste to landfillWe are working to reduce waste from our global operations, and to achieve zero waste to landfill in markets where the necessary infrastructure exists. This includes the responsible disposal of any surplus, unsaleable stock—but of course in an ideal world, there wouldn’t be any waste stock needing disposal. We’re taking steps to reduce book waste from our warehouses, and the digital transition will support this: with online books and journals there is zero risk of over-ordering.

How does digital publishing impact the environment?While we know that digital publishing has a lower footprint than print, it is not impact-free. Developing, hosting, and using digital content requires computing and server power, and most of this worldwide currently comes from burning fossil fuels. Over time, the impact should lessen as access to renewable electricity ramps up globally, for cloud data providers and consumers alike.

The production of laptops and e-readers has a notable environmental impact of its own, though this is arguably outside the publishing industry’s sphere of influence.

How do the carbon footprints of print and digital publishing compare?One rough estimate is that carbon emissions associated with the production, hosting, and use of an e-book are around one-tenth that of its printed equivalent. The industry collaboration DIMPACT is working on finding out the answer in precise detail.

OUP joined the collaboration in April 2022, and we will be using the DIMPACT calculator to estimate emissions from the Oxford Academic platform. From there we can compare the footprints of all our digital products. Once we know the facts, we’ll be looking for ways to reduce the impact of our digital publications, so they tread as lightly as possible on our planet.

October 31, 2022

Civil war and the end of the Roman Empire

In AD 400, the Roman Empire encircled the entire Mediterranean and looked, for all the world, as if it would continue to do so indefinitely. By AD 500, the Western portion of that Empire was no more. In its place stood some half dozen new kingdoms whose names—the kingdoms of the Franks, the Burgundians, the Vandals, the Saxons, the Goths—linked them not to the old Empire but to the world beyond its frontiers, the world of Germanic Europe. Given this, and given the images of wars and violence that colour almost every narrative of the period, ancient and modern, it has always been hard to escape the conclusion that the blame for Rome’s fall lies squarely with the ravening barbarians at the gates.

Barbarians there were, of course, but the truth of how they came to be at the gates is a little more complex. Since the second century BC, with the defeat of its greatest rival, Carthage, Rome had been the only show in town. For some six hundred years no power had existed that could rival Rome’s economic and military might. The Romans, however, faced a different military problem. Their Empire was simply too big: 1,500 miles north to south, 2,500 miles east to west, broken by mountain ranges, and spread across three of the world’s seven continents. As Augustine lamented in the early fifth century in his vast magnum opus, The City of God “the very breadth of the Empire has brought forth wars of a worse sort—social or rather civil wars” (19.7).

“Since the end of the second century AD, competition to dominate the vast apparatus of the Roman state had created conditions of almost endemic civil war.”

Since the end of the second century AD, competition to dominate the vast apparatus of the Roman state had created conditions of almost endemic civil war. Of the 29 decades between the year 190 AD and the year 480 (the year in which the last man claiming the title of Roman emperor in the West died), only two passed unmarked by Roman civil war. The third century, particularly during the so called “third century crisis” of 235-284 AD, is often seen as the high point of this trend, a period in which more than 80 emperors claimed power in short, bloody reigns, all but four of which ended with the emperor dying violently at Roman hands. Yet if in the fourth century the frequency of civil war declined, its intensity, if anything, increased. Five times between 300 and 400 AD, wars were fought that pitted the entire military manpower of the Eastern Empire against that of the West, wars settled in terrifyingly bloody pitched battles at which tens of thousands of Roman soldiers died. In 357, the emperor Julian led a small Roman army of 12,000 men against a coalition of Alemannic kings at Strasbourg, at which battle—a crushing Roman victory—Julian lost only 243 men. Six years before, when the emperors Constantius and Magnentius met in battle at Mursa, so says the historian Zonaras, 54,000 Roman soldiers died.

The entire military architecture of the Roman Empire was built around the fact that the greatest danger a Roman emperor faced was other Romans. Faced with a war on two fronts—one civil, one foreign—emperors invariably abandoned their foreign campaign (provincials in the threatened regions be damned)! and marched to fight their Roman enemy. Nor were Germanic “barbarians” merely spectators to these civil wars. Across the fourth century, Germanic tribesmen were recruited more and more actively to serve as foot soldiers in the armies that rival emperors would fling at one another. From the reign of the emperor Constantine (306-37 AD), men of Germanic extraction were, for the first time, granted access not only to service in Rome’s armies, but to command of them. By the late fourth century, senior military posts across the Empire were increasingly filled by men who—like Bauto, Richomer, Arbogast, Stilicho, Gainas, and others—had been born outside the Empire or were the children of people who had. Alaric, the “Goth” who sacked Rome in 410, spoke Latin, had lived his life within the Roman Empire, and led his soldiers in two bloody campaigns that the Eastern Empire waged upon the West, in 388 and 394. The line separating a barbarian king from a Roman general in the fourth and fifth century was frequently not a matter of culture, language, or ethnicity but merely a question of whether or not they were in imperial employ.

“The entire military architecture of the Roman Empire was built around the fact that the greatest danger a Roman emperor faced was other Romans.”

As military crisis on Rome’s borders worsened in the fifth century, prompted in part by the creation of a Hunnic Empire in middle Europe, competing Roman courts continued to worry, above all, about how to manage their Roman rivals. The Goths who sacked Rome under Alaric were not defeated in battle; they were rewarded by the emperor Honorius with lands in the south of Gaul in the beautiful and fertile valley of the Garonne river, in order to help protect the Italian court from Roman usurpers in Spain and Gaul. The Vandals, who crossed into Africa in 427 and founded there a kingdom that, at a stroke, deprived the Western Empire of its agricultural heartlands and the breadbasket of the city of Rome, were invited into the province by a disgruntled Roman commander who expected to use them to wage war upon his rivals in Italy. The Romans hated barbarians with a visceral passion, but in that hatred lay a contempt that led the Romans to treat them—as Varro once famously said of slaves—as “speaking tools.” Germanic barbarians, it is true, began to shear land and wealth from the Romans as the fifth century progressed. But they had been trained how to do it by the Romans themselves.

Feature image: “Constantine the Great” from Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers