Oxford University Press's Blog, page 67

October 14, 2022

Rumi’s subversive poetry and his sexually explicit stories

Rumi, the thirteenth-century Muslim poet, has become a household name in the last few decades, even becoming the best-selling poet in North America thanks to translations of his work into English. Verses of his poetry are used to begin yoga sessions, religious ceremonies, and weddings, and are ubiquitous throughout social media, in addition to actual sales of his books. His universalist perspective means that his poetry is quoted by practitioners in various traditions but with little Persian Sufi poetry readily available to compare it with, Rumi’s approach as a poet is completely unknown to most readers. This is a great pity since he was a subversive innovator.

Two things make Rumi’s lyrical poetry stand out. First is the deliberately childlike language used in many of his poems, including “Yar mara”—meaning “I have a beloved”—a much-performed poem in which “you are” is repeated 29 times in just eight couplets. And second, the breaking of the limits of genres: among his lyrical poems are mystical exegeses of the Qur’an and a famous homily on the Hajj pilgrimage with the refrain “O pilgrims on the Hajj, where have you gone? The Beloved is right here—come back!” Rebelliousness in the message should come as no surprise for a poet who innovates subversively with the form of his poems in a tradition of writing where strictly following the refined conventions of love poetry was expected.

Rumi’s subversive MasnaviRumi’s magnum opus is The Masnavi (literally, “The Rhyming Couplets”). This poem is so revered in the Muslim world that it is commonly referred to as “The Qur’an in Persian.” The Masnavi is also probably the longest single-authored mystical poem ever written in any civilization at approximately 26,000 verses across its six volumes. It contains the highest frequency by far of citations from the Qur’an among poems in the masnavi form, but its sources are wide-ranging, including religious scriptures, folklore, and works on astronomy and medicine.

Similar to his lyrical poetry, Rumi’s Masnavi is predictably subversive. It does not begin with the standard religious phrase used to start all other Muslim books (“In the Name of God…”), and instead presents 18 verses that begin and end with the same letters as that phrase begins and ends with, the Arabic alphabet’s equivalent of “b” and “m”. The poem also contains numerous lyrical passages traditionally excluded from the didactic masnavi form in which the poet does not normally refer to himself directly. Rumi breaks off from his narratives and homilies in this poem at will, explaining that he demands his readers’ immediate attention and does not want them to anticipate how plots might end.

“Of all Persian poets, it should be no surprise that Rumi should be the one trying something new and controversial.”

The most notorious of all Rumi’s poetic innovations is his inclusion of sexually explicit stories alongside the exegesis of scripture and stories about prophets. These stories are extraordinary in their own genre because, while other masnavi poems have stories about sexual encounters, Rumi provides all the crude details about genitals and bodily fluids. Book Five of The Masnavi includes most of these passages. The most talked about of the stories is probably the one about the mistress of a house who discovers that her maid has secretly been having sex with her donkey. Her reaction is to send the maidservant on an errand so she can secretly try the donkey herself. Not having learnt from the latter the need to use a contraption to prevent full penetration, the encounter ultimately kills her. Other more straightforward sexually explicit stories tend to be about fornication, with one comical example depicting a religious shaikh as standing up and performing the Muslim ritual prayer when interrupted from sex with his maidservant by his own wife.

Most commentators on Rumi’s sexually explicit stories have bashfully avoided discussing them. In the context of Book Five of The Masnavi, it is not too difficult to see that they warn about hidden corruption, similar to many stories in that volume that are not sexual in content. But the real mystery for most people is why Rumi should have used this kind of content at all. Of all Persian poets, it should be no surprise that Rumi should be the one trying something new and controversial. Moreover, when one observes his poetic innovations closely, one comes to the conclusion that they consistently serve to amplify the effect of his words.

Not satisfied with refinement of expression, Rumi was a poet who sought to shake his audience into action, hence his interactive involvement in his poems against all conventions, the often-childlike level of language, and heavy repetition. There is nothing more shocking than sexually explicit content—and also nothing as memorable. Moreover, the degree of shame involved in having one’s sexual activity exposed in crude detail serves as the most powerful warning of all against nurturing hidden corruptions rather than enduring the process of full purification on the Sufi path. Rumi was a master of keeping his audience engaged and receptive to the transformation his teachings could bring about inside them. For him, the ends justified the means, regardless of the rules, conventions, and taboos that they might break.

Featured image by Hulki Okan Tabak via Unsplash, public domain

October 13, 2022

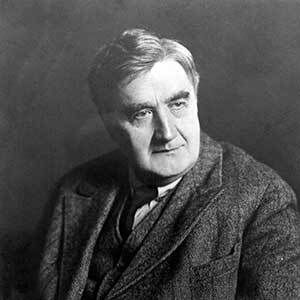

Ralph Vaughan Williams: preserving the publishing legacy

For any classical music publisher working up until the middle years of the twentieth century, and even later in many cases, paper was the primary means of dissemination for the sheet music and scores. Digital, and even photocopying, were still far ahead on the horizon, and making copies of anything required manual labour and pen and ink. All composers would write their compositions out by hand on music manuscript paper (the “autograph manuscript”); copies required for the first and other early performances would be copied out by music copyists, again on manuscript paper; a music engraver would work either from the autograph manuscript or from a marked-up copyist’s score to produce the plates required for printing; proofs would be produced, run off from the plates; and finally, after any corrections had been made, paper copies would be printed and bound, for sale or for hire. If the composition involved an orchestra the separate orchestral parts required for individual players would also be copied out, by hand, and in many cases later engraved and printed.

Much of the material produced for these processing purposes was regarded as ephemeral (the copyists’ scores, the proofs), but where it survives the items collectively will often shed fascinating light on the story of the music’s composition and the early performances—how a particular work journeyed from the mind and imagination of the composer into the hands of players for a live performance, and something of the individuals that enabled that to happen (the editors, the conductor, the performers). There is a “geological layer” aspect to much publishing ephemera, stories quietly sitting and awaiting discovery and telling.

Ralph Vaughan Williams

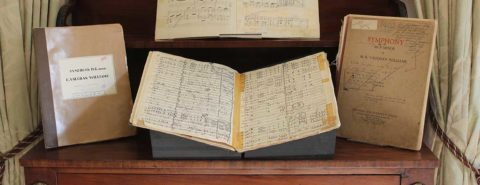

Ralph Vaughan WilliamsRalph Vaughan Williams was one of the most celebrated British composers of the twentieth century, and Oxford University Press was his principal music publisher from 1925 until his death in 1958. For Vaughan Williams, OUP published six of his nine symphonies, choral and instrumental works, hymns, carols, operas, and ballet—all of this music was initially made available using the processes described. After Vaughan Williams’s death, much of the surviving archival material was retained by OUP and held in storage.

In October 2022, as musicians across the world mark the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth, these materials are to be moved to the British Library, where they will join the Library’s existing world-class collection of Vaughan Williams autograph manuscripts, papers, letters, photographs, and other materials—the most comprehensive collection relating to this composer in the world.

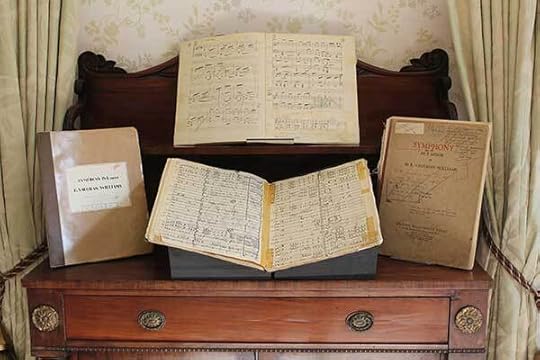

The OUP donation covers approximately 60 items, each one of these demonstrating some part of the publication process. Here, we explore a selection of the items, each telling a story from Vaughan Williams’s musical career.

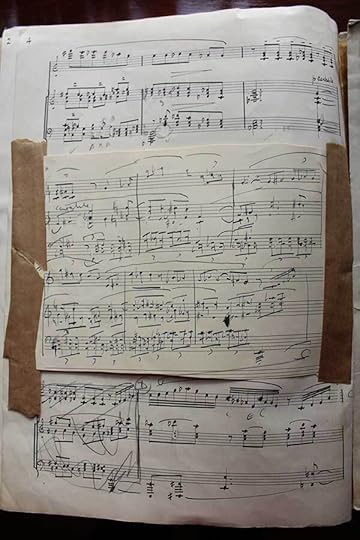

A “copyist’s copy” of the full score of “Symphony No. 4” (1934) has evidently passed through many hands: the composer’s (a sheet of his Dorking headed notepaper, with the title written in his hand, is used as a label on the cover, and his amendments are visible throughout the score); various conductors (performance markings, often in coloured crayon, are self-evident); the publisher (markings show the “plan” and pagination for the engraved and printed edition); and the engraver (queries for the publisher or composer are raised in pencilled notes). Furthermore, cuts and changes to the musical notation are shown, probably agreed between the conductor and the composer during the initial rehearsals.

A “copyist’s copy” of the full score of “Symphony No. 4” (1934) has evidently passed through many hands: the composer’s (a sheet of his Dorking headed notepaper, with the title written in his hand, is used as a label on the cover, and his amendments are visible throughout the score); various conductors (performance markings, often in coloured crayon, are self-evident); the publisher (markings show the “plan” and pagination for the engraved and printed edition); and the engraver (queries for the publisher or composer are raised in pencilled notes). Furthermore, cuts and changes to the musical notation are shown, probably agreed between the conductor and the composer during the initial rehearsals.  A surviving manuscript score of the piano reduction of the ballet “Job: A Masque for Dancing” (1930) shows hurriedly made cuts and changes, made during rehearsals—these amendments subsequently found their way into the matching full score and orchestral parts.

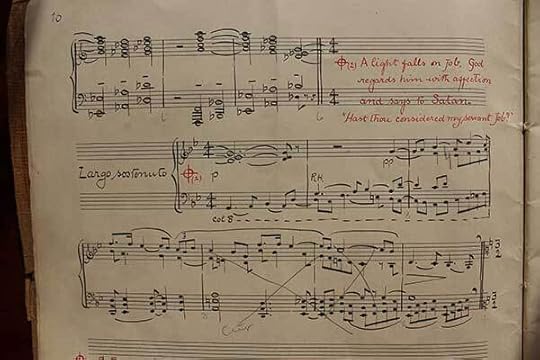

A surviving manuscript score of the piano reduction of the ballet “Job: A Masque for Dancing” (1930) shows hurriedly made cuts and changes, made during rehearsals—these amendments subsequently found their way into the matching full score and orchestral parts.  The smaller “Romance for Harmonica and String Orchestra”, written for Larry Adler in 1951, tells its story through a hand-copied piano reduction replete with pasted-over correction slips in the hand of Vaughan Williams (what lies beneath these paste-overs?).

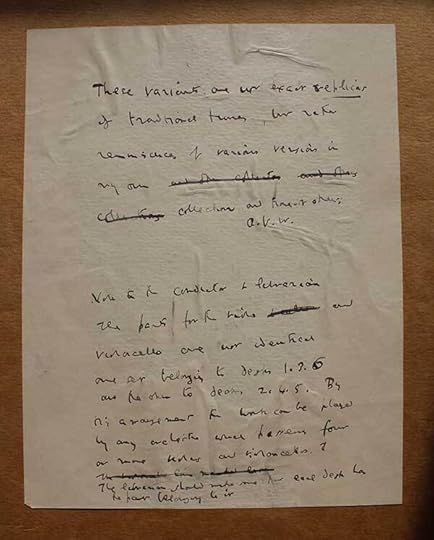

The smaller “Romance for Harmonica and String Orchestra”, written for Larry Adler in 1951, tells its story through a hand-copied piano reduction replete with pasted-over correction slips in the hand of Vaughan Williams (what lies beneath these paste-overs?).  This note, by Vaughan Williams and in his handwriting, is found pasted inside the cover of the pre-publication copyist’s full score of “Five Variants of ‘Dives and Lazarus’”, a work written for the 1939 New York World’s Fair (this score was also used by the conductor Adrian Boult at the first performance, in Carnegie Hall). The note, which explains both the provenance of the folk tune “Dives and Lazarus” and its use in this piece, and also the unusual “divisi” of violas and cellos required, was eventually transcribed and printed verbatim in the published full score (1940)—this paste-in is its original source.

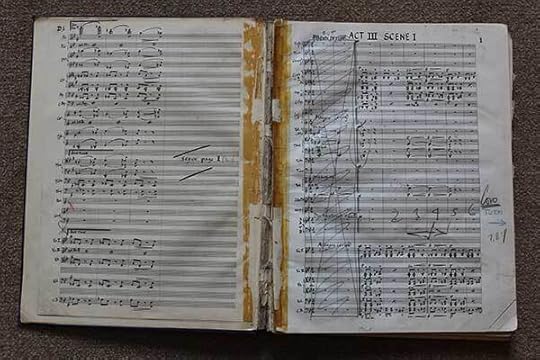

This note, by Vaughan Williams and in his handwriting, is found pasted inside the cover of the pre-publication copyist’s full score of “Five Variants of ‘Dives and Lazarus’”, a work written for the 1939 New York World’s Fair (this score was also used by the conductor Adrian Boult at the first performance, in Carnegie Hall). The note, which explains both the provenance of the folk tune “Dives and Lazarus” and its use in this piece, and also the unusual “divisi” of violas and cellos required, was eventually transcribed and printed verbatim in the published full score (1940)—this paste-in is its original source.  The OUP donation includes the full score (in five volumes) of the opera (“Morality”, as the composer preferred to call it) “The Pilgrim’s Progress” (1951) used at the Covent Garden first performances, and then by Sir Adrian Boult for his 1971 EMI recording (a surviving tape from the recording sessions reveals Boult’s annoyance that the scores did not lie flat—and they still don’t).

The OUP donation includes the full score (in five volumes) of the opera (“Morality”, as the composer preferred to call it) “The Pilgrim’s Progress” (1951) used at the Covent Garden first performances, and then by Sir Adrian Boult for his 1971 EMI recording (a surviving tape from the recording sessions reveals Boult’s annoyance that the scores did not lie flat—and they still don’t). Still photos taken by J. Black © Oxford University Press

October 12, 2022

Do you blather when you skate?

The origin of the word blatherskite ~ bletherskate “foolish talk; foolish talker” is supposedly secure. All the dictionaries and websites copy the entry from the OED. Below, I’ll reproduce the current explanation and slightly enlarge it. The same second element as in blatherskite (skite– ~-skate) occurs in cheapskate “miser.” Cheapskate, unlike blatherskite, is still a fairly well-known word, at least in American English, but it appeared in texts much later than blatherskite. A song attributed to the seventeenth-century Scottish poet Francis Sempill (or Sempel),?1616-1682, became popular during the American War of Independence. In this song, a young lady, accosted by a wandering piper, rebuffs his advances: “Right scornfully she answered him, / Begone, you hallanshaker, / Jog on your gait ye bletherskate, / My name is Mary Lauder.” The unfortunate jogger, as we see, had no reward for his pains.

Hallanshaker must probably refer to the raucous sounds made by the wooer (they make the hall shake), while bletherskate (the word that interests us) means, as far as I can understand, “a blathering piece of shit.” No sources I have consulted (mainly amateurs indulging in guesswork, but a few dictionaries too) derive skite from shit. They call the word obscure or connect skate ~ skite with shoot, squirt, Scandinavian skata “magpie” (that is, a chatterbox), skat “tax, tribute” (compare German Schatz “treasure”), and even with the fish name skate. A correspondent to the popular British biweekly Notes and Queries (8th series, XI, 1903, p. 335) compared –skite and skit. None of those suggestions inspires confidence. Shit goes back to the form with a long vowel in the root (ī), and I see no serious objections to my idea.

A classic cheapskate.

A classic cheapskate.(“L’Avaro” by Antonio Piccinni (1878), British Museum, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

By way of postscript, it should be added that on the American continent, bletheramskite and its Dutch double blathenschuyt have also been recorded. The Dutch form looks like bletheramskite produced by a Dutch speaker in New Amsterdam. The middle element (am) must be an insert of the same nature as de, a, and maw in tatterdemalion “a ragged person,” hobbledehoy, Flipper-de-gibbet “the name of a fiend,” cock-a-doodle-doo, and dialectal gamawdled “tipsy” (from gaddle “to drink greedily and hastily”). Betheramskite resembles one of such (usually humorous) extended forms. The German term for them is Streckformen, and German linguists explored them in depth, while in English scholarship, they attracted almost no attention, the only exception being such modern coinages as fan-damn-tastic. Thus, our word resolves itself into blether-am-skite. The variation a ~ i in the last syllable is a well-known dialectal phenomenon. (Some of our readers may have seen a cartoon, probably from Australia, with a smiling nurse saying to an elderly woman: “Congratulations, Mrs. Smith, you are going home todie.”)

Blather also deserves our attention but poses fewer problems. It may cause surprise that I so often refer to sound imitation and sound symbolism. But this happens because both factors play an outstanding role in language evolution, especially in the history of slang and conversational words. The more emotional a word is, the more striking its form should be. I have often mentioned the role of fl- in English. This initial consonant group appears in numerous verbs denoting inconstant or erratic movement: flitter, flutter, flicker, but also in fly, flow, flip, and many others like them. Perhaps flatter belongs to this group too. We note that fl– may alternate with bl– and that bl-verbs belong more or less to the same group as flitter, flatter, and their likes.

Jog on your gait.

Jog on your gait.(Photo by Isaac Wendland on Unsplash, public domain)

A typical example is Old Icelandic flaðra (ð has he value of th in English the). It seems to have meant “to beat about the bush.” In the modern language, flaðra means “to fawn on one, jump around someone (especially around a master), cringe before one, flatter.” We also observe that Old Icelandic blaðra was a synonym of flaðra and conclude that initial bl– may be as “symbolic” as fl-, even though it occurs in fewer words (but all conclusions about sound symbolism, even though valid, rest on a rather flimsy foundation).

English blather ~ blether is a borrowing from Old Norse. Thus, blatherskite is half-Scandinavian, half- Scottish. If my idea that skite is related to shit has any merit, then the second component may also be from Scandinavian (Old Icelandic for the verb shit was skíta), but in Scottish, as in the Scandinavian languages, the initial group sk– did not become sh– (that is why we don’t say Shotland or Shandinavia). Given my etymology of –skite, bletherskite can be, from a historical point of view, fully Scandinavian. But there is no certainty.

Sheep always express themselves sheepishly but symbolically.

Sheep always express themselves sheepishly but symbolically.(Photo via Pixabay, public domain)

It may now be worth our while to throw a quick look at some bl-words in Modern English. We first notice blah-blah-blah, which, amusingly enough, has been the subject of some etymological research (it is an American coinage). Blah resembles bleating, even though in English, the sheep “says” baa. In any case, bl– has firmly established itself in words whose meaning is quite “suggestive”: blab, blabber, blague “humbug,” blare, bleat, blither, blubber, and blob. There is little doubt that Icelandic blaðra is a member of the same family.

Just why bl– and fl– carry the overtones so obvious to us remains a puzzle. The initial bl– group occurs in numerous words in which it may have performed the same sound-symbolic function long ago (so, for instance, in blood, as well as blow “puff air, etc.” and blow “a hard stroke”). The same holds for fl-, but referring to this factor in etymology is risky. At present, the more such nouns, adjectives, and verbs we have, the stronger the impression is that they form a cohesive group, but in trying to discover the past of very old words (like blood, for instance), we cannot decide whether the associations so obvious to us existed two or three thousand years ago. Sound imitation is more or less universal. Cows and cats “say” the same everywhere, and people hear something like moo and meow in all places and at all times. The history of sound symbolism is hard to reconstruct.

To conclude, a bletherskite is, to my mind, a blathering shitter, whether he speaks, pipes, or is sent packing.

Featured image by cottonbro via Pexels, public domain

October 11, 2022

Towards climate justice: the role of cross-disciplinary Open Access research

Climate change is a global problem requiring global solutions. To find ways to mitigate for the huge environmental and societal impacts we are facing across the world, scientists and scholars, policy makers, governments, and industry leaders need to connect and collaborate effectively.

Open access publishing has a role to play in facilitating the discourse needed, by ensuring that the most up-to-date research is accessible, re-usable, and available to a wide audience quickly. At OUP, our flagship open access series, Oxford Open, includes several journals which connect researchers working in fields relevant to climate justice and which foster wider, more interdisciplinary collaboration. Below we hear from several of our Oxford Open Editors who elaborate on what this year’s Open Access Week theme “Open for Climate Justice” means to them.

“Expanding our discourse on climate change”: Eelco J. Rohling, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, Oxford Open Climate Change “Climate justice calls for multidisciplinary approaches in energy”: Peter D. Lund, Oxford Open Energy “Addressing the climate crisis will also avoid a global health crisis”: Rachael J.M. Bashford-Rogers, Oxford Open Immunology“Connecting health and infrastructure for climate justice”: Evelyne de Leeuw, PhD, and Patrick Harris, PhD, Editors-in-Chief, Oxford Open Infrastructure and Health “Fair and responsible consumption of materials”: Robert Vajtai, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, Oxford Open Materials Science “How can neuroscientists contribute towards achieving climate justice?”: Sam Gilbert, PhD, Senior Editor, Oxford Open Neuroscience Eelco J. Rohling, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, Oxford Open Climate ChangeAustralian National University, Australia, and University of Southampton, UK

Expanding our discourse on climate changeClimate justice calls for “a shift from a discourse on greenhouse gases and melting ice caps into a civil rights movement with the people and communities most vulnerable to climate impacts at its heart” (Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland, 2019). This call is even more pertinent now, after a further three years of climate extremes, alongside rampant global pollution and overexploitation, as well as ceaseless social inequality, poverty, conflict, and displacement. Holistic solutions are needed that span across at least several of these global problems.

In view of quote above, however, I would argue that we need an expansion of the discourse on climate change, rather than a shift. It would not be helpful to shift away from the discourse on climate change because that assumes that we fully understand the impacts and timescales of climate change on global and regional scales. We don’t. This is why IPCC projections keep moving; every new bit of evidence hones our understanding, but also opens new questions. Moreover, human adaptation responses are not uniform across the world, but depend on geography, cultural background, and economic viability.

“We need an expansion of the discourse on climate change; every new bit of evidence hones our understanding, but also opens new questions.”

In the physical sciences, there are especially major questions around the likelihood of crossing so-called climate “tipping-points,” which are abrupt shifts from one climate state to another when a certain threshold value is surpassed. And these tipping points have enormous implications for society—especially vulnerable communities—because they are so poorly predictable, and because the adjustment will be completely disproportional to what has gone on before. We have very good examples in recent geological history that these tipping points are very real and that they have critical environmental implications on hemispheric to global scales.

So, let’s not shift away from the climate change discourse as if we know what’s coming and how rapidly it will come. Let’s instead expand the climate change discourse and bring our knowledge to bear to meaningfully help vulnerable communities both deal with what we know is coming and prepare for what may happen if some of the critical tipping points get surpassed. We need a holistic approach, not a shift from one silo to another. At the new journal Oxford Open Climate Change, we aim to achieve this by reaching across the entire multi-disciplinary climate change research community.

Peter D. Lund, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, Oxford Open EnergyAalto University, Finland

Climate justice calls for multidisciplinary approaches in energyClimate justice as a concept has many facets and is accompanied with different nuances. For me working in energy, the dimension linked to intergenerational justness is of particular concern: our generation’s responsibility to take care of its fair share of reducing the greenhouse-gas emissions without shifting the burden and the unprecedented consequences to the next generations. Climate justice therefore represents here a kind of moral crossway choosing between a just and unjust energy path.

As fossil fuels are in the heart of the global climate crises standing for most of the emissions, transforming our energy systems into emission-free systems is urgent. To limit the adverse effects of the human-caused climate change, carbon neutrality needs to be achieved by the middle of this century. Rapid progress in many clean technologies such as wind power, solar energy, and batteries gives new hope that reaching this challenging goal could be feasible.

“The complexity of the energy question in the climate justice context cannot be mastered by one discipline only.”

But the energy transition ahead is not just leading to a paradigm shift from fossil to clean energy. It will also trigger a huge societal transition affecting almost everything around us from legislation and business models to consumer behaviour, educating users, and more—that is, affecting in practice each and every one of us. To be successful, the clean energy transition has to consider simultaneously the technical, economic, social, and policy layers of the change. These need to advance without friction to accomplish a successful transition much in the same way as the gears in a clockwork need to be “synchronized” to move the clock hand forward. Such “synchronization” touches, for example, complex socio-political questions around the ability of developing countries and vulnerable groups in our societies to afford and manage such a big transition in a relatively short time. It should go without saying that stronger climate solidarity will be required, meaning that those with greater power and resource must ensure everyone can stay aboard in the transition. In energy, that would mean developing affordable, safe, and clean energy for all.

The complexity of the energy question in the climate justice context cannot be mastered by one discipline only. For science to provide relevant solutions and to deliver content with wide societal impact in response to the climate justice, we need much stronger interdisciplinary research that spans more than one energy discipline.

Rachael J.M. Bashford-Rogers, PhD, Associate Editor, Oxford Open ImmunologyWellcome Centre for Human Genetics, Oxford, United Kingdom

Addressing the climate crisis will also avoid a global health crisisThere are multiple direct and indirect factors linking climate change with human health. Although the extent of human (and animal) vulnerability to infectious disease caused by changes in climate have not been fully quantified, there is widespread agreement that we are already observing changes in pathogenic patterns. The shifts in the geographical ranges of pathogens and their vectors are clear ecological indicators of climate change and are already requiring significant changes to health care service infrastructures to efficiently diagnose and treat these diseases, with over half of known infectious diseases affecting humans reported to be aggravated by climate change through multiple mechanisms.

For example, changes in temperature, rainfall, and humidity are associated with an expanded range of vectors, such as mosquitoes, ticks, birds, fleas, that are implicated in the increased outbreaks of viruses, bacteria, protozoan, and animal-meditated diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, plague, Lyme disease, West Nile virus, Zika, malaria, trypanosomiasis, and echinococcosis. Warmer temperatures at higher latitudes results in pathogens and their vectors surviving winters and therefore aggravating outbreaks, for example in dengue and Zika. In 2020, nearly half of the world’s population was at risk of malaria causing ~627,000 deaths annually and significant morbidity worldwide. With climate change, we are seeing the proliferation of the malaria-carrying mosquitoes at higher latitudes and altitudes, resulting in an increase in malaria transmission in areas that were previously malaria-free. In areas where malaria is already endemic, warmer temperatures alter the growth cycle of the parasite in the mosquito enabling it to develop faster and therefore increasing transmission and disease burden.

There is both hope and caution with the impact of some of these diseases. Will the development of effective malaria vaccines outweigh increased drug resistance and pathogen evolution? Will we learn from the COVID-19 lockdown periods to replace unnecessary travel with technology-aided communication? Will we build housing and infrastructure that will reduce carbon and pollution emissions whilst also maintaining an improved living environment for us all? However, the climate crisis and its accompanying health crisis cannot be solved by scientist and clinicians alone.

Evelyne de Leeuw, PhD, and Patrick Harris, PhD, Editors-in-Chief, Oxford Open Infrastructure and HealthUniversity of New South Wales, Sydney

Connecting health and infrastructure for climate justiceHumanity strives to and achieves progress through infrastructure. Infrastructure provides the hardware, tools, and services for a connected and functioning planet. Those connections are not just for humans but whole ecosystems. But climate change, especially with a justice lens, challenges infrastructure to be bold in scope and ambition, dynamic and adaptive, and full of vision and aspiration. Infrastructure for climate justice is not just engineering and building projects but is inclusive of the range of factors and dynamics between the planetary and nano-particle. Above all, the new era of the Anthropocene requires infrastructure that emphasises big connections for wellbeing.

“Climate change, especially with a justice lens, challenges infrastructure to be bold in scope and ambition, dynamic and adaptive, and full of vision and aspiration.”

Those big connections are the intent of Oxford Open Infrastructure and Health (OOIH). Our vision for the journal stems from decades of research and practice working at the interface of health, broadly defined, with societal challenges that have congealed around what infrastructure does and can do. Infrastructure that is poorly thought through and planned, and therefore impossible or slow to adapt, is proving to be a devastating cause of climate injustice globally and locally. Institutionalised inertia is core to the problem with limited accountability from governments and industry for the infrastructure they fund and build to the people and the environment.

The gap between the various manifestations of infrastructure and human, planetary, and ecological wellbeing has been researched for years now. But filling that gap requires a scholarly and policy platform. OOIH intends to step in. Connections between big boundary-spanning ideas like the Sustainable Development Goals are foundational. Linking those ideas across sectors and disciplines to foster connections for progress is the journal’s necessary function. And above all, our aim is to challenge the status quo to be bolder, better, innovative, adaptive, and accountable.

Robert Vajtai, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, Oxford Open Materials ScienceRice University, USA

Fair and responsible consumption of materialsIt is an interesting and paradoxical fact that—despite our best effort and intentions—scientific and engineering advancement often comes with a big footprint: we pursue a more convenient life, at the cost of high energy consumption, and more materials used and wasted. For example, advances in efficient computer and mobile phone processors do not only result in previously bulky equipment now shrinking into pocket-sized devices, but also much greater demand for smartphones and constantly updating to newer models, even in low-income environments. A state-of-the-art phone has a much larger memory and higher computational power than the computers which delivered humans to the Moon. Looking at mining, production, and waste management for the vast quantities of personal electronics demonstrates this point.

“The responsibility of all materials scientists and nanoengineers is to focus on advancement in the direction of a safer and better world at large.

Having this said, the responsibility of all materials scientists and nanoengineers is to focus on advancement in the direction of a safer and better world at large. Staying with the example of computers, we are working on improving the efficiency of computations; using quantum materials and neural networks to build computers that predict the pathway of hurricanes more accurately and earlier or bring us to a liveable Mars. Our mission is to develop materials for higher-efficiency solar energy conversion, highly efficient and selective nanocatalysts, high volumetric and specific capacity batteries, and—in my opinion—the most environmentally-friendly energy storage: hydrogen economy. We must do all of this to make sure that clean energy, clean air, and clean water are available for every citizen of Earth, in order to deliver climate justice.

Sam Gilbert, PhD, Senior Editor, Oxford Open NeuroscienceInstitute of Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London, United Kingdom

How can neuroscientists contribute towards achieving climate justice?We can start by limiting, where possible, the impacts of our own activities: the emissions caused by wet labs and tools such as MRI scanners, the carbon footprint of computationally-intensive methods and data centres, the harm caused by air travel to academic conferences and meetings. But the concept of climate justice highlights another issue. The countries that have contributed least to global emissions are also the least well-equipped to deal with the impacts and will suffer the most severe consequences. Those countries that have historically emitted the most therefore bear the greatest responsibility to act.

A similar argument can be made about our individual role as neuroscientists. Those of us who have built successful careers on decades of air travel can most afford to cut back now and are best placed to argue for climate action in our own institutions. One welcome consequence of a neuroscience community less reliant on frequent air travel to promote and disseminate research would be a reduction to the barriers faced by students, early-career researchers, and those from parts of the world historically under-represented within our field. Neuroscientists, particularly those at the highest levels of seniority, have the skills, influence, and the responsibility to advocate for change.

Oxford Open is the flagship series of open access journals published by Oxford University Press. Journals in this series further OUP’s mission to support excellence in research, scholarship, and education.

Find out more about the Oxford Open series.

The intertwined history of state lotteries and convenience stores

This past summer, millions of Americans were transfixed by the prospect of becoming billionaires. After weeks with no winner, the jackpot for the multi-state lottery game Mega Millions rose to $1.3 billion before being won by an as-yet-unnamed gambler who purchased the winning ticket at a Speedway gas station in Des Plaines, Illinois. Or, more specifically, at the convenience store portion of the gas station, where customers can purchase gas, food, drinks, cigarettes, and, of course, lottery tickets.

It is unsurprising that the winning ticket was purchased at a gas station convenience store. As recently as 2020, nearly 70% of total lottery sales nationwide were made at convenience stores (including convenience stores attached to gas stations). What may be surprising is just how intertwined the history of state lotteries is with the history of the American convenience store. The two emerged at roughly the same time, convenience stores helped lotteries become a $90 billion-a-year industry, and lotteries helped convenience stores secure their place at the heart modern American commerce.

The first wave of state lotteries spread over the Northeast and Rust Belt in the 1960s and 1970s, where states initially strove for respectability. Tickets were sold in a variety of retail businesses and nonprofit organizations, from barbershops to union halls. This strategy was born of necessity: states wanted to meet potential players where they already gathered and to legitimize a consumer product that had long been underground and associated with organized crime.

The rise of the convenience store changed the game for state lottery commissions. In 1959, there were just 900 convenience stores across the entire United States. By 1977 there were 27,000 and in 1990 there were 71,000. A number of factors contributed to the quick rise of quick shopping. Convenience stores opened earlier and closed later than grocery stores. As more women entered the workforce, households compensated by making fewer grocery trips and picking up goods at a corner market, even if the prices were somewhat higher.

Another factor was the consolidation of the grocery store industry. In Chicago, the number of grocery stores declined from over 13,000 in 1954 to 3,600 by 1987. A result was entire communities with little access to healthy food, known as “food deserts.” For many, especially in minority urban neighborhoods, the choice to patronize a newly-opened convenience store was a last resort born of financial and logistical necessity.

The spread of convenience stores was especially significant for state gambling officials because these retailers shared a primary customer base with lotteries. Convenience store clientele consisted primarily of blue-collar men, many of whom were drawn to the stores’ prepared foods, their expanded operating hours, their large number of locations, and their sale of alcohol and tobacco. Nationwide, as many as 70% of 7-Eleven’s customers in the late 1970s were men. Similarly, studies show that men are more likely than women to play the lottery, and, on average, they gambled more.

It should come as no surprise, then, that lottery tickets were a major convenience store item. By 1997, roughly 65% of convenience store customers nationwide purchased lottery tickets at least occasionally, and 55% said the availability of lottery tickets was important to their choice of shopping destination. In 1984, administrators from nine state lotteries were asked their preferences for type of lottery retailer. Liquor and convenience stores were the most preferred, followed by drug stores and newsstands

For their part, retailers were more than happy to add lottery tickets to their inventory. Stores receive a cut on each ticket sold, generally around 5%. While the margin on lottery tickets is lower than for most other products, and though periods of lottomania created havoc at overwhelmed ticket counters, lottery players typically purchased other goods when they bought their tickets.

As a result, in some states, convenience store chains helped lobby for the passage of lottery legislation. In Virginia, 7-Eleven provided 22% of the funding for the state’s 1987 lottery referendum.

The profits explain why. In Virginia, 7-Eleven account for over 30% of total lottery sales in 1991, amounting to over $14 million in commission profits. In the mid-1990s, convenience stores in the nation’s 37 lottery states sold $18 billion worth of lottery tickets. By contrast, tobacco sales at convenience stores across all 50 states totaled $17 billion.

State lotteries, then, might not be as big as they are without convenience stores, and convenience stores owe much of their continued profitability to the enduring popularity of lottery tickets. While the nation waits with bated breath to see who—if anyone—will come forward with the winning ticket, all we know about this lucky person is that they visited an Illinois Speedway in late July. Their patronage of this outlet represents another reminder of how both lottery tickets and convenience shopping have only in the last few decades became ubiquitous parts of the American commercial landscape.

October 10, 2022

Eight composers whose music we should know

In 2022, the BBC Proms commissioned more music by female composers than music from male composers. 2022 also saw the first Black female composer write a score for the New York City Ballet company. We can celebrate that contemporary programming is increasingly embracing a wider range of voices. For historic reasons, attitudes to female education and racial prejudice among them, the arts have missed out on the rich repertoire and creativity from earlier times of many female and ethnically diverse musicians and composers—but times are changing. Here are eight composers whose music is coming into the light.

Amy Marcy Cheney Beach, 1867-1944.

Amy Marcy Cheney Beach, 1867-1944.(Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)1. Amy Beach

Amy Beach (1867-1944) may not have received the same opportunities as her male counterparts but despite this she became the first successful female American composer of large-scale classical music. Her “Gaelic” symphony, first performed in 1896, was the first symphony to have been written by a female American composer. Among her compositions are a Piano concerto, a string quartet, and piano pieces. Her music is tuneful and elegant, as can be heard in this arrangement for cello and piano from her Op. 25. No. 2 (Columbine).

2. Florence PriceFlorence Price (1887-1953) was an African American student at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. It is said that she passed herself as Mexican in order to avoid the racial discrimination of the times. A prolific output of more than 300 works, including four symphonies, a piano concerto, choral compositions, and works for piano and organ have secured her reputation as an early twentieth century composer of note.

3. Amélie-Julie CandeilleThe French child prodigy Amélie-Julie Candeille (1767-1834) was something of a super-star; she not only composed music but achieved success as a singer, pianist, actor, and playwright! Her music for keyboard, often written for her own performance, is virtuosic and lies firmly in the Classical style.

4. Cécile Chaminade Teresa Carreño

Teresa Carreño(Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The father of the French pianist and composer Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944) disapproved of her receiving a musical education. Despite this, she began studying music with her mother and became a student at the prestigious Paris Conservatoire. She wrote predominantly for the piano and had considerable success as a performer at the start of the twentieth century, giving recitals in the United States and England.

5. Teresa CarreñoNot many people can say they have a crater on Venus named after them, or that they performed at the White House for President Abraham Lincoln, but the Venezuelan pianist and composer Teresa Carreño (1853-1917) can! She enjoyed an international career as a virtuoso pianist, giving concerts world-wide. She composed works for voice and piano, some chamber music, but wrote mainly for piano. Her music is sometimes virtuosic in style but she also had a gift for lyrical melody as heard in this expressive elegy.

6. Elfrida AndréeThe Swedish composer and conductor Elfrida Andrée (1841-1929) was one of the first female organists to be appointed in Scandinavia. She was active in the women’s movement and campaigned for a change in the law to allow women to apply for the position of cathedral organists. She wrote chamber and orchestral music, choral, and instrumental works, and two organ symphonies. Her musical style is lyrical and expressive.

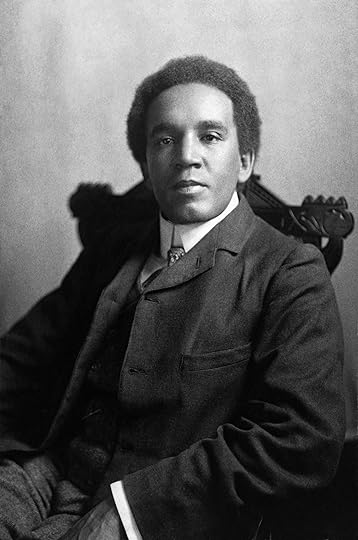

7. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor(Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The English composer and conductor Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) was nicknamed the “Black Mahler” by some white American musicians due to his considerable musical success. His cantata, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, was hugely popular and was performed frequently in Britain and around the world. He was born in London to an English mother and a father originally from Sierra Leone. In his music, for example in 24 piano pieces based on spirituals Op. 59, he aimed to integrate traditional African music into the classical tradition in the same way as composers such as Brahms had done with Hungarian folk music.

8. Francesca LebrunA female composer who was an exact contemporary of Mozart, Francesca Lebrun (1756-91) was a German composer and opera singer famous for her vocal range and virtuosity. It is said that she could sing the A three octaves above middle C. Her compositions include works for violin and harpsichord and they display many features of the Classical style: fast scale and arpeggio passages and straightforward phrasing and harmony.

The list could, of course, go on—Clara Schumann, Nathaniel Dett, Lucien Lambert, and many more. Indeed, now is the time to celebrate that so many previously over-looked or forgotten composers are coming into the light. In compiling Solo Time for Cello, we have endeavoured to bring this music to a wider audience in the hope that students may be inspired and encouraged to discover more.

Featured image: Portrait of Francesca Lebrun (1756-1791), via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Click the icon below to listen.

October 8, 2022

Being a careful reader

My local supermarket was offering frozen vegetables—French fries actually—with the sign “Buy two—get one free.” I was shopping for frozen peas, but on impulse I also grabbed two bags of fries and tossed them in my cart. When I got to the checkout stand, the cashier charged me for both bags of French fries. “I thought the second one was free,” I said.

“You have to buy two,” the cashier replied, emphasizing the words buy two, “and the next one is free.” I misread the sign, went back for a third bag, and ended up with more frozen potatoes than I wanted.

My friends and family had little sympathy for my mistake. After all, “Buy one—get one free” has been around for so long it has its own abbreviation BOGOF. The word free got my attention, but my mistake was thinking that “get one free” referred to one of the two bags in my cart rather than to a third one. I should have thought it through. After all, if “Buy two, get one free” meant the same thing as “Buy one, get one free,” then two meant one.

But I was tempted by the promise of salty carbs. I’m probably not the only person misled by this discount language. The next time I went the store, I noticed that the sign read: “Buy two. Third one free.”

When we are moving briskly though a supermarket, skimming ads, or focusing on a big purchase, it’s easy to be a less-than-careful reader.

“PROVEN TO SAVE UP TO 47% ON YOUR HEATING AND COOLING BILLS!” That sounds good, but if doesn’t meant that YOU will save 47%. Yet a Federal Trade Commission study conducted by Manoj Hastak and Dennis Murphy found that 36% of subjects misread that as saying they would save the maximum. Another research study on a sample home equity loans with interest “as low as 5.1% APR” found that almost 29% of respondents thought the ad meant everyone would get the 5.1% rate.

Modal verbs like could are also easily misread. If a weight loss program claims you could lose ten pounds in a week, that might be true of some people, but not everyone and not necessarily you. They are counting on careless reading and wishful thinking.

And look out for products with asterisked footnotes to their bold claims. A 40-ounce container of dish soap announces “33% MORE SOAP*.” The footnote clarifies that it is “compared to the 30-ounce size.” Well, okay. Thanks for the math refresher.

My favorite was the bag of flavored pretzel nuggets saying “50% LESS FAT PRETZEL PIECES” followed by the footnote “Than the Leading Brand of Regular Potato Chips.”

Reading a supermarket sign, an ad, a bottle of soap, or a bag of pretzels, we do not always ponder language as carefully as we might. A sign catches our attention and we make assumptions about its meaning. Sometimes those assumptions don’t match what is being actually said.

As scholars, it’s important to read texts charitably. But as consumers, we should read skeptically, and on a full stomach.

Featured image: “Clark’s Super Market, Jacksonville, Florida” by John Margolies. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

October 7, 2022

Reframing an aging policy agenda for the AAPI community

Over the past few years—often but not always driven by the COVID-19 pandemic—we have had great discussions and debates over societal inequalities in our nation’s infrastructure, and hopefully these in turn will result in policy changes. Aging, too, is having such a review as we think through how older people of color face disparities in key needs such as financial security, housing, and healthcare.

Also striking within this debate is an elevation of challenges facing the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community in these policy debates. AAPIs have a complex history in the United States with the spectrum running from being signaled out for outright exclusion from immigration laws to then being branded as a model minority and consequently a wedge for identity politics. In particular, the “model minority” myth inflates AAPIs’ socio-economic status and economic success, suggesting that older AAPIs may not need services and supports to help them successfully age well.

Events during the pandemic shined a light on barriers facing AAPIs that were previously ignored or invisible. First, COVID-19 has had disproportionate effects among AAPIs. From a health perspective, the Government Accountability Office noted that certain AAPI populations are overrepresented among COVID-19 cases but underrepresented in vaccinations. From an economic perspective, the pandemic has devastated sectors where AAPIs are overrepresented such as retail and hospitality.

Second, individual AAPIs faced violent attacks due to misperceptions and racist beliefs on COVID-19’s origins. The Pew Research Center found that nearly four in five AAPI adults believed violence against them is increasing, and nearly a third of AAPI adults feared being threatened or physically attacked. These attacks, including horrific shootings in Atlanta and Indianapolis, led Congress to pass the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act, which will improve data collection on hate crimes and provide additional educational resources through the federal law enforcement and health agencies. Several incidents of violent attacks on older AAPIs highlighted gaps in key aging services—transportation, financial security, caregiving resources, and in-language services, among others—that should be part of building our community’s policy agenda.

Regardless of why the discussion is happening, having it is critical to understanding how policies and systems should adapt to meet the needs of the fastest growing demographic in the United States. The AAPI designation though is incredibly diverse with nearly all of the Asian American community tracing its origins to 19 different countries. In the 2020 census, the Asian American community grew by 81%. At such a rate, one analysis predicted that the Asian American population could more than triple by 2060 and will be the largest immigrant group by 2055. Just like the United States overall, the AAPI population will age, too: the Administration for Community Living notes that the number of older Asian Americans also will triple from 2.5 million in 2019 to nearly 8 million in 2060.

“When AAPIs are viewed as a whole, differences can be difficult to notice, but when data is disaggregated, significant variation and health disparities become visible.”

But the larger movement toward greater inclusion of communities of color has not come without criticism. For instance, a Wall Street Journal editorial decried “how woke politics is about to infect medical education.” But at the same time, the editorial acknowledges that understanding relationships between race and disease or recognizing social determinants can help with patient outcomes. It fails, however, to connect that acknowledgment with how having some understanding of the role of existing systems—including the healthcare system—can reinforce, rather than reduce, health disparities and inequities. Connecting these dots could help provide a constructive dialogue on educational curriculum for health and aging professionals.

For AAPIs, seeing professionals who have a better understanding of issues facing our community would lead to improved outcomes and better conditions. For example, the editorial’s conclusion laments that newly-trained physicians will be too overwhelmed “attend[ing] to their guilt” to make a cancer diagnosis, but if health professionals learn to be aware of disparities such as disproportionate rates of cancers among different Asian ethnicities, they may consider screening an AAPI patient differently. In other words, when AAPIs are viewed as a whole, differences can be difficult to notice, but when data is disaggregated, significant variation and health disparities become visible. Tools like artificial intelligence could alert a physician, too, to such disparities.

This example also highlights a unique phenomenon facing the AAPI community in its advocacy. While the increase of AAPIs should lead to its growing clout within policymaking, AAPIs’ rich diversity creates a challenge in developing policies that can neatly fit their needs. As noted, AAPIs are often grouped together as a “model minority,” but they come from numerous different countries with their own language, culture, religions, and other characteristics, making it difficult to articulate an AAPI view on critical issues like aging. While we can gain strength from positioning ourselves as a single collective, failing to recognize differences can lead policymakers—often incorrectly— to see us as not needing assistance, especially if we do not advocate for it.

As we emerge from the pandemic, we must learn from the despair that it has caused to make our social services, including our aging services, more equitable. We can restructure aging services and supports to be not only more responsive to our country’s needs but also more equitable for AAPIs and communities of color writ large.

Featured image by RODNAE Productions via Pexels, public domain

October 6, 2022

Which library should you visit? [Quiz]

Looking for some new bookish destinations to tick off your bucket list? Are you a lover of libraries or just looking for somewhere new to explore? Or do you simply want a bit of literary escapism? Get some inspiration for your next trip by taking this short quiz and finding out which library you should visit!

Make sure to tweet us your results at @OUPLibraries, and follow for more inspiration with our #LibraryOfTheWeek series.

For all the latest library news, quizzes, offers and products, follow us on Twitter @OUPLibraries.

Think your library should be featured in our #LibraryOfTheWeek? Email us and tell us what makes your library special or send us a message via Twitter.

Featured image by Matthew Feeney via Unsplash, public domain.

October 5, 2022

Noises off? A guarded tribute to onomatopoeia and sea-sickness

While trying to solve etymological riddles, we often encounter references to sound-imitation where we do not expect them, but the core examples hold no surprise. It seems that nouns and verbs describing all kinds of noises should illustrate the role of onomatopoeia, and indeed, hum, ending in m, makes one think of quiet singing (crooning) and perhaps invites peace, while drum, with its dr-, probably evokes the idea of the noise associated with this instrument. Most helpfully, some dictionaries inform us that humdrum is a word of unknown etymology. Perhaps so, but if both hum and drum refer to acoustics, why is one’s humdrum existence so devoid of gentle sound and noble fury?

We should probably admit that the origin of even the simplest words describing sound may pose problems. Abú, used in Irish battle cries, ended up in English as part of the word hubbub, an onomatopoeia of course, but with a history that had to be reconstructed. A similar case is English babble, gurgle, rattle, prattle, crash, crush, and their likes. Though their nature is obvious, each has a history in need of reconstruction. Some have unmistakable cognates in other Germanic languages and even beyond them. Compare the post on trash (24 March and 31 March 2021). One often wonders whether such words can be borrowed. Multiple examples show that they can. Compare raucous. This adjective is a late borrowing from Latin, which means that the distance between primitive sound imitation and the word we know and use increases. I have also more than once pointed out how bookish and “unnatural” our interjections are (ah, bah, oh, eh, oops, let alone the upsy–daisy stuff).

At full blast.

At full blast.(Photo by Jason Rosewell on Unsplash, public domain)

An especially instructive case is ruckus “a noisy fight; row.” The word has been “known” (that is, current in texts) for about a century and a half. It surfaced in American English, but no one knows where it came from. Nor do too many people care about its shady heritage, if I can judge by the absence of ruckus and its kin (rumpus “disturbance,” ruction “brawl,” and rumbustious “boisterous, violent”) in my huge database of English etymology, which, otherwise, is full of the most exotic regional words (compare ruzzom “an ear of grain,” rykelot “a bird,” and rynt “to get out of the way”) and of course slang. For ruckus I have only a popular note in The Atlantic Monthly (1991). The original OED often used the epithet fanciful about such formations, and fanciful they indeed sometimes are.

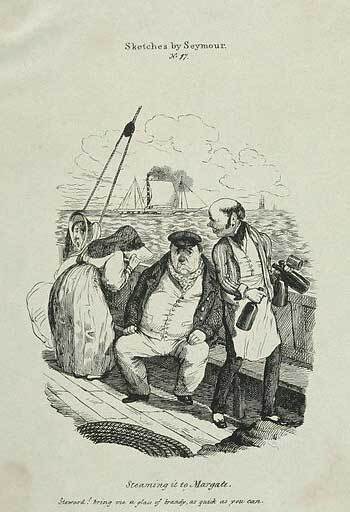

(Image: “People suffering from seasickness on board a steam boat.” Reproduction of an etching after R Seymour, via Look and Learn, CC BY 4.0)

(Image: “People suffering from seasickness on board a steam boat.” Reproduction of an etching after R Seymour, via Look and Learn, CC BY 4.0)The word that, for a long time, has been uppermost in my mind and whose history is the topic of this blog post is noise. A classic case of sound imitation? Not at all! The word’s etymology is supposedly “known,” but its development poses many questions. Greek had two forms corresponding to English “sea-sickness” (pay attention to the “sea” component!): nausía and nautía. Latin borrowed the second of them (we recognize its root in English nautical; and remember Captain Nemo’s Nautilus “little ship”). The word remained in all the modern Romance languages and reached English in the form nausea, but in Old (and Modern) French it also yielded noise “outcry, disturbance” and was taken over by Middle English. Elsewhere in the Old Romance languages, the meanings are “harm, dispute; injury” and even “dung” (so in Old Italian).

Friedrich Diez, the founder of Romance philology and the author of the first etymological dictionary of the Romance languages (1853), suggested that noise had been derived from Latin nausea “sea-sickness, disgust,” with “disgust” yielding “loud outcry.” All students of English etymology seem to have accepted this idea. The direct source of noise (already so in Middle English) was Old French noise ~ nose. Incidentally, the English adjective noisome was formed from Middle English noy, for anoy, a borrowing of Old French anoi “vexation.” Thus, English annoy seems to have nothing to do with noise. However, it may be worthwhile to consult The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia.

This multivolume work had the ill luck to be launched when the first volumes of the OED began to appear and was thus destined to fall into oblivion. Today, few people open it, but it is an excellent reference work. One of its many editors was Charles Scott, responsible for etymology. His detailed explanations deserve high praise, and consulting them often pays off. This is what he wrote about noise:

Lamentation.

Lamentation.(By Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1538, via WikiArts, public domain)

“…according to some, from Latin nausea ‘disgust, nausea….’; according to others, from Latin noxia ‘hurt, harm, damage, injury…’; but neither explanation is satisfactory in regard to either form or sense. Confusion of form and sense with some other words, as those represented by noisome [‘hurtful, mischievous, noxious’ (obsolete)] and noisant [‘harmful, troublesome’; obsolete], annoy, noy [‘trouble, affliction’ also obsolete], noysome, etc. seems to have occurred.”

It was the distinguished philologist Leo Spitzer who made the most serious attempt to trace the way from some Romance word to French and English noise. The Old French source of English noise already had the meaning we know. The earliest Romance texts show that the idea of “illness, languor” often led to “grief,” and here comes Spitzer’s main point: in the extant medieval texts, grief is inseparable from lamentations. Thus is English wail related to woe (by many steps, but the connection is safe). Throughout the Middle Ages, we find ritual wailing, that is, scenes of violent lament following the death of a relative. It should be added that this custom of inviting professional mourners (“weepers”) to the family gathering of a deceased person has been recorded in many countries, and we have vivid descriptions of the rite going back to as late as the twentieth century. In Spitzer’s words, “We may…assume that noise in the meaning ‘noise’ originated from the background of loud wailing or mourning.”

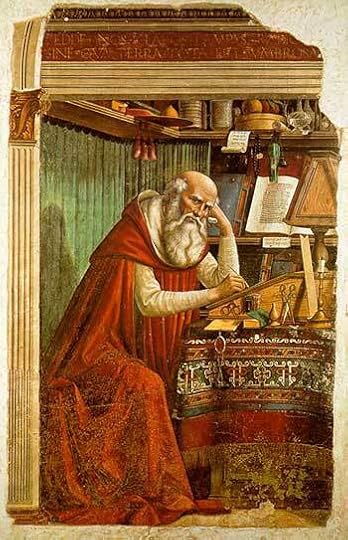

St. Jerome at work.

St. Jerome at work.(By Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1480, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The word’s evolution, as Spitzer presents it, incurred the following steps: “sea-sickness, vomiting,” going together with “disgust, boredom” (so in Classical Latin), “illness” or “grief” (so in the canonical text of St. Jerome’s Bible, known as the Vulgate), and finally, “(loud) lament” and “quarrel, strife, discord; noise.” He cited a partly parallel development in Portuguese nojo: from “disgust, vomiting” to “grief” and “mourning.” This is an impressive example of reconstructing the otherwise incomprehensible semantic change. Perhaps one may ask why the starting point of the long way he (as well as Diez and nearly everybody) envisioned was such an unexpected concept as sea-sickness. My doubt pertains to Old French rather than to Middle English, because, as noted, English borrowed the French word wholesale. It is partly up to Romance scholars to decide whether Charles Scott’s doubts were in some way justified. At this stage, we won’t contest Spitzer’s etymology and won’t be annoyed by a few noisant details.

Featured image by Rafael Ishkhanyan on Unsplash, public domain

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers