Oxford University Press's Blog, page 71

August 29, 2022

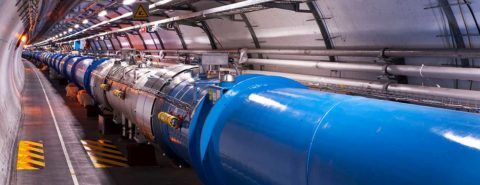

The CERN Large Hadron Collider is back

The CERN Large Hadron Collider, the LHC, is the world’s highest-energy particle accelerator. It smashes together protons with energies almost 7,000 times their intrinsic energy at rest to explore nature at distances as small as 1 part in 100,000 of the size of an atomic nucleus. These large energies and small distances hold clues to fundamental mysteries about the origin and nature of the elementary particles that make up matter.

The LHC is a high-performance machine, a Formula 1 race car, not a Toyota. As such, it needs to spend time in the shop. The previous run of the LHC ended in December 2018. Since then, scientists and technicians have installed numerous fixes and improvements to both the accelerator and the particle detectors. In mid-April, the LHC began a series of final tests and tunings, raising the collision energy from 13 TeV to 13.6 TeV, moving closer to the design energy of 14 TeV. On 5 July the new run of>Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

August 26, 2022

Disappearing animals, disappearing us: what can Classics teach us about the climate crisis?

In the 1950s, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss reflected that phenomena tend to elicit academic attention just as they are disappearing. Then (as memorably recalled by Emily Martin), he was writing about the world of the “primitive” in human culture, at that time in its last throes of resisting the spread of globalisation. But read against the current proliferation of research on animals across the sciences and the humanities, his observation could not be more depressingly poignant. The now globalized capitalist exploitation of the natural world is precipitating the most urgent crisis humans and other animals have ever known. “If humans killed each other at the same rate we kill animals,” one shocking statistic declares, “we’d be extinct in 17 days” (see Crary and Gruen).

In fact as the West has typically approached the question of the human, the story of the disappearing “primitive”—the variety of human once naively thought closest to “nature”—has always been structurally interwoven with the story of the disappearing animal. Early-modern and modern European attempts to understand others remain indebted to Classical imaginings that deal with the issue of difference by constructing axes of inclusion and exclusion in order to read human diversity in the mirror of the animal. Linnaeus’ foundational enlightenment act of defining the human species as Homo sapiens (the “man who knows” from the Latin sapere) both placed man into the animal kingdom and differentiated him, following Aristotle, as the unique “reasoning” species (Linnaeus playfully appended the imperative nosce te ipsum, the Latinization of the ancient Greek philosophical dictum gnōthi seauton “know yourself,” to the genus heading his list of species, challenging his readers to recognize themselves in the beings of non-sapient others). Even in the nascent strands of nineteenth-century ethnology and anthropology that contested the theory of races which Linnaeus’ taxonomy of the Homo (amongst other sources) inspired, the emergence of fully realized humankind from the animal was conceived as the concomitant of the emergence of ever more complex forms of culture from a primal animalistic nature.

“European attempts to understand others remain indebted to Classical imaginings that deal with the issue of difference by constructing axes of inclusion and exclusion.”

As early anthropology reused that Classical idea, the lives of indigenous others—pursued and so best observed in the “field”—offered a first coordinate in the wider story of humankind’s universal struggle to ascend from the level of the beast. Yet as anthropology’s language of “fieldwork” implied, written into the ambition to find universalities connecting all humans writ large in humanity at its “simplest” was–even amongst the most generous critics—the relegation of indigenous others to states of quasi-animality. Long before the stadial theories of the enlightenment and social evolutionism of the nineteenth century hierarchized humans according to their relative social development (or degree of “progress”), European colonialism had invoked the same idea to justify its expropriation of the labour and rights of indigenous peoples. At the centre of the European exploitation of the New World which (importing African slaves) initiated global capitalism, lay the issue of the humanity or otherwise of the Amerindians, and with their relegation to irrational Aristotelian “natural slaves” by the invaders, so also white settlers’ rights to dehumanize, kill, and exploit for profit.

In our late capitalist modernity, the same binary structures of inclusion and exclusion, power and disenfranchisement, continue to exert themselves: as scientists of the Anthropocene plot disappearing biodiversity and seek to conserve the natural world as if an open resource of benefit to humans, those most economically and socially vulnerable (most famously, the low income, largely migrant workforce working in close proximity in the US’s industrial meat processing plants (see also Crary and Gruen)), suffer soaring rates of infection from COVID-19 (itself, likely a viral by product of the capitalist exploitation of animals). Exemplified by the epochal concept of the Anthropocene (“the new age of the anthrōpos”), which sophistically repurposes a Classical Greek (sophistic) nature-culture antagonism in order to recast a specifically modern capitalist violence as a general human one, the scientific worldview at the foundation of current environmental thinking remains wedded to the prevailing “naturalism” of Western modernity, which authorizes the same human exceptionalism that has long authorized violence against others. We are all implicated in this system by which we are driving ourselves to extinction.

“We need above all else to think differently about difference, and anthropologically about the world we think we already know.”

So how can studying the Classics now possibly matter?

The insidious role of Classical ideas in Western thought about the human and in the pernicious ways of dealing with difference that continue to sustain our unsustainable capitalist lives, should tell us. It should teach us that if we are to find and do better in this existential crisis, our first steps must lie in defamiliarizing our disastrous axiomatic Western contentions, recognizing their Classical contingency, and thinking beyond the structures of thought informing our present deleterious ways of relating to the world. We need above all else to think differently about difference, and anthropologically about the world we think we already know. We will not be the last of the world’s disappearing animals, but we are the only one responsible for its own ruin. Enough of the path we have forged from these Classical beginnings. Now is the time to learn from the possibilities of others.

Featured image taken by Ashley Clements, used with permission.

August 22, 2022

From navigation to architecture: how the brain interprets spaces and designs places

How do our brains help us learn about the spatial relationships in our world and then use them to find our way from one place to another? And how might answering this question offer new insights into how architects design?

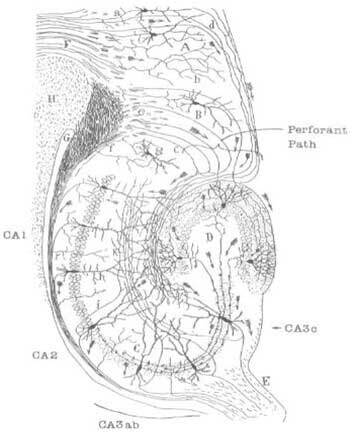

One possible answer to the first question came from the Nobel-prize winning discovery by John O’Keefe and his colleagues that linked navigation to the hippocampus of the rat brain. O’Keefe discovered neurons whose firing encoded where, in its small world, the animal found itself. More specifically, if the animal moved around a small box or simple maze, there were neurons—he called them place cells—that fired only when the animal was in a small region that he called the place field of the place cell.

The “seahorse” cross section of hippocampus showing a schematization of core neural circuitry, as drawn by the Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1899).

The “seahorse” cross section of hippocampus showing a schematization of core neural circuitry, as drawn by the Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1899).But pause a moment. The word “place” can mean somewhat different things. In response to the question “Where did you meet Luigi?”, the natural answer would be, perhaps, “On the Belvedere of the Villa Cimbrone.” But place could also require detail like “30 meters from the left end of the Belvedere and 50 centimeters back from the balustrade.” So, going forward, let’s distinguish a significant or memorable place from a metrically defined place, and reserve the word place for the first usage and location for the second.

Cognitive mapping and navigationNote that “knowing where you are” is very different from “being able to navigate.” A billboard on which there is an “x” with the legend “you are here” and is otherwise blank, is not a map. A map must encode all the places that matter to us and the paths we need to find a route from where we are to where we want to be, even if we have never before travelled between these two places. If the map is “in our head” we call it a cognitive map. The alternative to figuring out a path is simply to follow a route—whether a habitual route or one specified by a friend or smartphone.

In 1975-6, Israel Lieblich and I developed a computational account of how rats could find satisfactory paths through mazes depending on whether they were hungry, thirsty, or fearful. We modeled a cognitive map as a structure with nodes to represent significant places and with edges for the direct paths between them. We called this structure a World Graph (WG), but there are many such graphs at very different scales—whether encoding the places where food, water, or fearful stimuli can be found in a rat’s maze; the stations and connecting lines in a subway map; or the route maps of airlines that are indeed maps of the world—that differ in what constitutes a significant place when employing the map. Thus, we may have multiple WGs for the same territory.

The Bridges of Königsberg problem: Is there a walk through the city that would cross each of its seven bridges (shown at Left) once and only once? (Right) The graph generated by Leonhard Euler (1736) as the basis for a general mathematical theorem which implies that no such walk exists. Each land area becomes a node, while each bridge becomes an edge.Cognitive mapping and architectural design

The Bridges of Königsberg problem: Is there a walk through the city that would cross each of its seven bridges (shown at Left) once and only once? (Right) The graph generated by Leonhard Euler (1736) as the basis for a general mathematical theorem which implies that no such walk exists. Each land area becomes a node, while each bridge becomes an edge.Cognitive mapping and architectural designJust as a cognitive map is different from a set of fixed paths, so the cognitive scientist’s sense of script is very different from the script of a play, where who says what and when is prescribed in advance. Consider the “birthday party” script: the guests must bring presents, someone must prepare a cake with candles, and the candles must be lit before the birthday-honoree blows them out, etcetera. But whether the presents are opened before or after the cake ceremony, and what other activities are part of the party is not prespecified. Let’s just add that, when a party is held, the activities specified in the script require places in which they occur.

The implication for architecture is that a building is designed to serve multiple purposes and the architect must envisage how the building will support inhabitants in their performance of relevant scripts. The significant places for a building (or a city) are not only those where one can perform one’s own versions of the practical scripts that the architect has considered, but also those where one can appreciate a particular view, whether from the outside or within. Moreover, a building may succeed not only by satisfying the planned scripts—consider the highly scripted activities that distinguish schools, hospitals, and churches—but also by providing opportunities for users to explore.

This positive sense of exploration is what we might call waylosing:

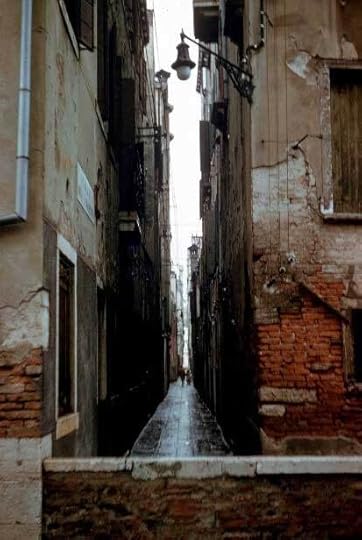

I am not advocating waylosing on the way to the maternity ward, but in less stressed situations it can be great fun. Waylosing is … one of the great attractions of Venice … finding something unexpected and useful when looking for something else. (Per Mollerup, 21 April 2014.)

I thought I had coined the word waylosing before I found this citation and had indeed applied it to the absolute delight of exploring Venice in a random way, far from the madding crowd in Piazza San Marco.

Waylosing in Venice, 1957. (Author’s photo).From scripts to cognitive maps to architecture

Waylosing in Venice, 1957. (Author’s photo).From scripts to cognitive maps to architectureAll this led to a new perspective on architectural design, incorporating insights from brain imaging, neuropsychology, and computational modeling.

One challenge was to show how fragments of the architect’s memories can morph and combine in the design of forms that will afford new experiences to the future user. This required examining available studies of the role of the hippocampus in episodic memory (recalling past episodes, rather than contributing to a cognitive map) and how it also forms part of larger systems engaged in imagination. When we perform a script within a building, we are developing and exploiting cognitive maps to proceed from place to place within the satisfaction of that script, rather than simply seeking a path from start point to goal. In my book When Brains Meet Buildings, I thus analyzed what it means for the designer, imagining the experiences and behaviors of users of the forthcoming building, to in some sense “invert” the process whereby each user will form their own cognitive maps (note the plural) for the satisfaction of a range of scripts, and as the basis for forming new scripts for their own exploration and enjoyment of the building.

In sketching ideas for a building, the architect will develop ideas of the form, function, and feeling of the various spaces within and around it. The present discussion focuses on how ideas for different places envisaged to serve practical and aesthetic functions help define the places that will actually be constructed in and around the building. Ideas for these notional places must develop during the design process. These places may satisfy goals within diverse scripts—a focus on the feel of the kitchen might yield a script that demands a place for admiring the view of a garden, another for the meal-preparation script will demand a place to put the oven. At early stages of design, there will be multiple scripts, with each script having its own set of places that define the nodes of what we might call a script-WG. These specifications of the roles of inter-related places complement the architect’s sketches of the form of the building’s spaces, with limited specification of where and how the nodes will be linked to locations in the 3D Euclidean space defined around the site where the building will be constructed. Edges in a preliminary script-WG will simply mark transitions that will occur from one place to another in executing the corresponding script.

Waylosing in Venice, 1957. (Author’s photo).

Waylosing in Venice, 1957. (Author’s photo).All this leads to study of melding diverse scripts as a crucial process: a design that specifies separate places for each node of each script may be both uneconomical and inconvenient. For example, the scripts for food preparation and dishwashing in a home would normally involve using the same sink, whereas in a restaurant they might not. As design proceeds towards construction drawings, the various nodes must become anchored in that Euclidean space. This can include decisions to map certain nodes in distinct script-WGs to the same location, and this entails that the two script-WGs become merged into one as shared nodes inherit their properties and the edges of their progenitors. This in turn requires assessing whether features of one script do or do not block features of the other script as the new WG is refined to accommodate both scripts. The process of working this out may reflect back to modify the “what connects to what” of design at the WG level but also the aesthetics of form that marks the architect’s individual signature in shaping the building.

The implications of this work are to push understanding of architecture beyond the views offered by glossy photographs in magazines and on websites to engage with a deeper understanding of how people act and interact in the spaces that architects provide. This has implications for linking neuroscience (broadly conceived to include cognitive science and biology more generally) to a deeper understanding of human well-being. It also offers invitations to scientists to extend their studies from the laboratory to the built environment as the basis for fruitful conversations between architecture and neuroscience. To paraphrase John Fitzgerald Kennedy, “Ask not only what neuroscience can do for architecture, but also what architecture can do for neuroscience.”

August 21, 2022

Monument: what did Shakespeare look like?

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.What did Shakespeare look like?

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.What did Shakespeare look like?When we picture Shakespeare, we usually think of the “Droeshout portrait,” the engraved frontispiece for the volume that collected all “Mr William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies.” But the First Folio, as it is known, was published in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, and there is little evidence that the engraver, Martin Droeshout, ever saw Shakespeare. We console ourselves that people who did know Shakespeare seem to have accepted the likeness (Ben Jonson said Droeshout had “hit” it).

The same argument has been applied to the demi-figure sculpture of Shakespeare on his funerary monument in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon: it must have been approved by his survivors. Now, however, it is possible to conclude that the monument was created during his lifetime, as one-third of early modern monuments were, and was commissioned by Shakespeare himself from a sculptor he met in person.

[Wm. Shakespeare], the second impression [graphic] / Martin Droeshout, sculpsit- Droeshout, Martin, b. 1601, printmaker

. FSL collection (CC BY-SA 4.0).

[Wm. Shakespeare], the second impression [graphic] / Martin Droeshout, sculpsit- Droeshout, Martin, b. 1601, printmaker

. FSL collection (CC BY-SA 4.0). Two years before Shakespeare died in 1616, his friend John Combe was buried in Holy Trinity. In his will, Combe directed that “a convenient tomb of the value of threescore pounds . . . be set over me . . . within one year after my decease.” According to the Warwickshire antiquarian Sir William Dugdale, the man who made Combe’s monument was named Johnson. Dugdale thought “Gerard” Johnson, but the more likely artisan was Gerard’s son Nicholas. It was Johnson family practice to establish residence for a week or two to oversee the “placing” of their larger commissions, and the Combe monument featured a life-size effigy laid on a marble tomb chest and sheltered by a great arched canopy, the whole structure anchored to a chancel wall. Shakespeare is said to have authored two verse epitaphs for Combe, a satirical one for Combe’s own enjoyment in his last years and a kinder one after Combe died. By then retired to Stratford, he would almost certainly have visited Nicholas Johnson at work. This may also have been when he commissioned his own monument and when Johnson saw his next subject in the flesh.

We once believed that Shakespeare’s monument was installed around 1623, the date of the First Folio, but newer evidence suggests that the antiquarian John Weever saw it in place as early as 1617 or 1618. Notably, the memorial inscription was likely painted in two stages. Shakespeare’s date of death and his age at death appear to have been added to a poetic tribute that was probably inscribed before his death. Unlike Combe, Shakespeare left no directions in his will; if the monument had been completed in early 1616, there was no need.

At the time, three-dimensional figural representations were generally of three types: effigies lying recumbent in death and looking upward towards heaven (like Combe), figures kneeling in preparation for death and looking inward or towards prayer books, and half-height figures sheltered in architectural niches and looking outward towards their viewers. Shakespeare’s was of the last type, which had a limited vogue between about 1610 and 1640. Nicholas Johnson is known to have produced at least one other example that survives in London. Radically, it made a memorial less about death than about a life of accomplishment.

One variation on the demi-figure type was at first seen only in the college chapels of Oxford University: figures with cushions terminating their torsos. Shakespeare’s cushion has sometimes been mistaken for a woolsack, but it was a conventional attribute for men of learning. Cushions were the settings for books, not only as required for the Bible-bearing pulpits of English parish churches, but also as used by university lecturers. At the time of Shakespeare’s death, all the cushioned monuments in England had Oxford connections.

Shakespeare’s biographers have long fretted over the fact that he never attended university. This should not have been surprising at a time when divinity was the subject for most advanced education. But local oral history tells us that during those years that Shakespeare lived and worked in London, he returned home to Stratford at least once a year. It was a three- or four-day trip with Oxford a common stopping place. He is said to have stayed in the house of an Oxford couple who maintained drinking rooms for university folk. This was before there were college common rooms and before colleges were closed off with fences and gates. In early-seventeenth-century Oxford, Shakespeare would have been free to mingle with Oxford’s most distinguished scholars. The Oxford cushion on his monument suggests that he attended sermons in the college chapels where their monuments were mounted. He seems to have been inspired to take the form for himself.

If Shakespeare commissioned his own monument, we see him as he wanted to be seen: in a life portrait, wearing “a black gown like an undergraduate’s at Oxford” (as William Aubrey observed around 1640), holding a quill in one hand, resting another hand on a sheet of paper, and poised to write.

Featured image: Shakespeare-holy-trinity-18.jpg , via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

August 19, 2022

Policing direct democracy under US state constitutions: the Massachusetts example

The United States Constitution does not contemplate the possibility of lawmaking via direct democracy. Almost every US state constitution, on the other hand, does. This means that every state supreme court must address questions about whether initiative proposals adhere to the state constitutional requirements governing ballot questions, and about whether these proposals run afoul of some substantive limitation contained elsewhere in the state constitution. In such cases, state high courts must confront the extent to which they can—or should—police the mechanisms of popular lawmaking.

A recent decision by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) is illustrative. In Koussa v. Attorney General, the SJC put an end to an initiative proposal that would have asked voters to determine whether ride-share drivers should be classified as independent contractors or as employees. The court’s decision, as reported here, brought to a halt “what was primed to be an enormously expensive ballot campaign that was already gaining national attention.”

As is true in many states, modern initiative proposals under Article 48 of the Massachusetts Constitution are often controversial. It was not always so. Voters agreed to add Article 48 to the state constitution more than a hundred years ago “in the hopes,” as Jerold Duquette and Maurice T. Cunningham have explained, “that the power of citizens could overcome an unresponsive legislature and pass legal measures to meet the people’s needs.” As Duquette and Cunningham note, it has only been in the last two decades that the initiative process in Massachusetts has become the focus of “interest group battles and the playground of the well-heeled rather than a wellspring of citizen action.” The underlying controversy in Koussa over how to classify ride-share drivers exemplifies this development. By the end of 2021, Uber, Lyft, and other gig economy companies had devoted almost $18 million to promote the ballot question; for their part, opponents of the proposal had raised more than $1 million. The $13 million contribution from Lyft apparently was the largest in Massachusetts history.

Given the stakes, there should be little surprise that the ride-share proposal’s proponents immediately criticized the SJC’s decision in Koussa as the result of litigation designed to “subvert the democratic process.” In fact, Koussa is better understood as simply an effort by the SJC to enforce existing checks on Article 48’s initiative process—to ensure that the provision continues to reflect both the hopes of the citizens who framed and ratified Article 48, and the provision’s role in the constitutional scheme of Massachusetts government. The unanimous opinion of the court emphasizes the importance of the constitutional requirement that initiative petitions contain “only subjects … which are related or which are mutually dependent.” This requirement recognizes that voters, unlike legislators, cannot make changes to a proposal via the initiative process, as legislators can through the traditional lawmaking process.

The SJC ultimately concluded that the Massachusetts Attorney General erred in applying this requirement when she certified the ride-share proposal for inclusion on the ballot. As the court explained, when a proposal contains multiple subjects, they must share a common purpose. That common purpose cannot be so broad that the proposal’s subjects are only distantly related to one another. Rather, the purpose must be sufficiently coherent across all of the proposal’s various provisions that voters can view them together as a coherent and unified statement of policy. The court specifically concluded that the ride-share proposal violated the relatedness requirement by presenting voters with “two substantively distinct policy decisions”—one addressing the relationship between ride-share drivers and the companies they work for, and one seeking to limit those companies’ potential liability to third parties who suffer injuries as the result of conduct by ride-share drivers.

“Judicially enforceable rules regarding the ballot process … reflect an effort … to uphold the bounds of popular lawmaking via Article 48.”

So understood, the decision in Koussa makes logical sense. As the SJC acknowledged, there is not necessarily a relationship between a provision that would define a ride-share driver’s employment status and a provision that would insulate ride-share companies from certain legal liability—the latter is not dependent on the former.

It is worth keeping in mind, moreover, that judicially enforceable rules regarding the ballot process, such as the relatedness requirement, reflect an effort not just to maintain the integrity of the initiative process, but to uphold the bounds of popular lawmaking via Article 48. [RC1] In other words, these requirements seek to maintain Article 48 as a constitutional exception, not the rule. This is in keeping with the history of the initiative in Massachusetts as a mechanism for lawmaking aimed at particular instances in which the legislative process has failed to match the popular will—and not as a means to supplant the constitutional preference for deliberative lawmaking that John Adams envisioned for the Commonwealth when the citizens of Massachusetts adopted the state charter in 1780.

The history and role of direct democracy are not unique to Massachusetts, of course, and state courts may learn much from one another. The SJC, older than any other court in the nation and interpreting the oldest written constitution in the world, may yet have lessons to impart to other courts looking to police the processes of popular lawmaking embraced by their state’s constitutions.

Featured image by NASA via Unsplash, public domain

August 18, 2022

Has Russian journalism returned to Soviet era restrictions?

“As Vladimir Putin’s leadership enters its third decade, time will tell whether the despair of the current generation will be replaced by a renewed sense of journalism’s power to effect change.” That was how I ended the epilogue of News From Moscow, my monograph on post-war journalism in the Soviet Union. When I wrote those words, the situation for Russian journalists was already dire: journalists who contradicted the Kremlin line were regularly harassed, and independent publications were forced to register as “foreign agents.” But Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February has made a bad situation immeasurably worse. Sooner than expected, the dismal future of Russian journalism is becoming clearer.

Before I discuss the war’s effects on Russian journalists, it is important to begin this post by acknowledging the even-worse fate of Ukrainian journalists, at least 30 of whom have been killed in the conflict, either as frontline reporters or victims of Russian bombing. Occupying forces have deliberately targeted the press: countless Ukrainian journalists have been kidnapped, tortured or “disappeared,” while their families have also been threatened. But it is thanks to these journalists that audiences around the world have learned about Russian war crimes. Despite threats to silence them, Ukrainian journalists continue to search for the truth about a war Russian journalists cannot even name.

“Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February has made a bad situation immeasurably worse.”

The intensification of the so-called “special military operation” became a pretext for a crackdown on independent media across Russia. Officials threatened to prosecute those who described events in Ukraine as a war, while the state’s media watchdog Roskomnadzor blocked access to the websites of many independent outlets. As a result, the Russian news landscape has become a state-controlled landscape, with news outlets including Meduza and Mediazona only accessible through a VPN. Staples of the liberal 1990s, such as the radio station Ekho Moskvy and the newspaper Novaia gazeta closed their doors in March, having been threatened by Roskomnadzor. The latter’s editor, Dmitri Muratov, was attacked with red paint on a train to Samara, an assault which underlines the dangerous conditions for anti-war journalists, who now face 10-15 years in jail for disseminating “fake news.”

When, in June 2021, Muratov was awarded the Nobel Prize, the committee’s statement mentioned the newspaper’s “fundamentally critical attitude towards power” as well as its “fact-based journalism and professional integrity.” But how can journalists working within the Russian mediascape maintain their integrity in a climate that seems to mitigate against truth, and which calls for moral compromises rather than ethical principles?

For some Russian journalists, the invasion presents an opportunity. Russian television now offers a ready platform for various regime loyalists, nationalists, and conspiracists to launder their pet theories, including Vladimir Solovyov, a media pundit famous for his increasingly-deranged rants on Channel One. For others, the invasion became the straw that broke the camel’s back. State media was hit with a stream of resignations, while most of the non-Russian staff who had run the various versions of RT, the Russian state’s foreign broadcasting arm, rapidly jumped ship. The most high-profile act of dissent was the protest of Maria Ovsyannikova, an editor on the Channel One news, who famously crashed the channel’s evening news broadcast carrying an anti-war banner. Ovsyannikova was feted by western media and subsequently accepted a post with the German newspaper Die Welt. That decision was met with consternation from journalists and activists, who wondered why Ovsyannikova, who had for many years worked to disseminate the Kremlin’s narrative, had suddenly become a poster child for dissent.

“Are journalists automatically tainted by association with a discredited regime or can they point to positive actions they had taken to mitigate its impact?”

These discussions of complicity recall debates taking place after 1991, at which point journalists were understandably keen to deflect accusations of having been Soviet propagandists. They raise a wider question about journalism in authoritarian conditions: are journalists automatically tainted by association with a discredited regime, or can they point to positive actions they had taken to mitigate its impact?

I am sometimes asked about parallels between the present-day Russian journalism and the press of the Soviet era: are we back in the USSR? The journalists at Dozhd’ suggested as much when they broadcast footage of Swan Lake in March, an allusion to Soviet TV broadcasts of the ballet during emergencies. One must, however, acknowledge the differences: independent media in the Soviet Union ended with the Decree on the Press of 9 November 1917, which effectively mandated the closure of all non-Bolshevik newspapers; after the Soviet collapse, it has never been illegal for journalists to start a new newspaper, nor to express opinions that differ from those of the regime. The Kremlin authorities have preferred to dismantle these freedoms piece by piece rather than with a single legislative act. The key point is that for much of the Soviet Union’s existence, journalists had no memory of the pre-1917 past, nor any expectation of being able to act independently. Today’s journalists, by contrast, are the children of Perestroika and the 1990s, and had, until recently, been able to speak truth to power. For that reason, there is a sense of loss.

Good journalism meant different things in each period. Soviet journalists were never free to contradict the Party line, nor to break important news stories, which were always approved at high levels. Journalists’ work was always tied to the overarching goal of building communism. Nevertheless, this still left them with space for creativity—especially after Stalin’s death. For journalists in the 1950s and 1960s, a period I examine in detail in my book, journalists helped popularise new pedagogical initiatives and even inaugurated the country’s first polling institute. Doing so, they hoped, would unleash untapped energies from below that would enable the building of communism. At the same time, they helped smooth the regime’s rough edges. Newspapers received thousands of letters every week, complaining of various ills of Soviet life, from a leaking roof to wrongful imprisonment. These letters became the source material for articles which could reverse a sentence, secure long-awaited housing, or expose official wrongdoing. It is this spirit of public service that allows Soviet journalists to claim that they were public servants, even if much of the material in their newspapers was geared towards the Party’s goals.

In the present day, the Kremlin’s constant attacks on independent journalists mean the hard-won freedoms of 1991 have shrunk to almost nothing. Top-level journalists at leading state broadcasters operate under constraints that recall Soviet conditions, including daily memorandums giving details of subjects to be covered and those to be avoided. The majority of journalists, who form the staff of regional television stations and newspapers, are increasingly squeezed between the requirements of their employers, their advertisers, and the demands of local politicians. In this climate, as Elisabeth Schimpfössl and Ilya Yablokov have noted, good journalism boils down to adekvatnost’: an ability to understand the “rules of the game” in the face of political and commercial restrictions and to operate effectively within those parameters.

“The disappearance of independent media will only intensify the feeling that Russian journalists are providers of propaganda and distraction.”

Adekvatnost’ could similarly describe the work of Soviet journalists who operated in a hostile political climate that severely restricted their freedom. Indeed, one of the most iconic accounts of the Soviet press came from the émigre novelist Sergei Dovlatov, whose comic novella The Compromise (1981) details the daily accommodations with authority that marred a young journalist’s career. Yet some Soviet journalists remained hopeful about the communist future and even when that future horizon receded, retained a belief that journalism could serve the public. Present-day Russian journalists, by contrast, have imbibed the Putin’s era’s trademark cynicism. The disappearance of independent media will only intensify the feeling that Russian journalists are providers of propaganda and distraction rather than contributors to the public good. Nevertheless, there remain journalists—many outside Russia, some, bravely, within it—who have continued to question the official line via Twitter, YouTube, Telegram, or blog posts. As Farida Rustamova, an exiled journalist whose Substack offers a perceptive view of Russian politics, told Meduza: “I started writing, among other things, to keep my hands and my head busy and to be of at least some use, describing what I can discover. I don’t want Russian speakers, especially in Russia, to be left alone with Putin’s propaganda”.

Featured image by Jeremy Bishop via Unsplash, public domain

August 16, 2022

Epiphanies: an interview with Sophie Grace Chappell

Sophie Grace Chappell is Professor of Philosophy at the Open University, UK, and her new book Epiphanies: An Ethics of Experience, has just been published by OUP. In this interview, Sophie speaks with OUP Philosophy editor Peter Momtchiloff on exploring the concept and experience of epiphanies.

Some readers might not have the concept of an epiphany. Do you think your book might help these people to appreciate something about their experience that they haven’t previously had a way of framing?

As the author of Genesis understood, and also Sigmund Freud, there can be a kind of power in naming things. Tools for classifying our own experience are tools for understanding our own experience, and so for understanding ourselves. Very often this has a political aspect. For example, Miranda Fricker’s notion of epistemic injustice has a pleasing reflexivity about it. If you suffer from what Fricker calls hermeneutic epistemic injustice, that means that you lack the descriptive and expressive tools to say what is wrong with your situation. But then, one of the key tools that you need is the concept of hermeneutic epistemic injustice itself. Being able to name your situation as one of hermeneutic epistemic injustice is a key means to escaping that situation.

On the other hand, there are ways of framing ourselves that aren’t genuinely explanatory at all: they don’t pick up anything real about us, so they don’t offer any genuine insight into anything. Saying you’re a Sagittarius or an endomorph or that your birthstone is jasper is like this. So is saying you’re an introvert, probably; or at the very least this last classification needs a lot more clarification and precision.

And again, there are classifications that we should positively avoid, because what they do is underwrite ways of thinking and seeing ourselves that are inherently oppressive. American English used to have the words “quadroon” and “octaroon”, for two different degrees of being mixed-race; just imagine what a society would have to be like, for us even to have a use for this distinction. Or closer to hand, think of the ideology familiarly buried in terms like “ladylike” and “manly” and indeed a term I’ve sometimes used myself: “master-concept”.

“With the concept of an epiphany I am hoping to latch onto a genuinely explanatory way of framing our experience.”

So yes, with the concept of an epiphany I am hoping to latch onto a genuinely explanatory way of framing our experience, not a bogus one. And I would hope a liberatory framing too, and not an ideologically conservative or reactionary one.

You talk about an epiphany as an insight or experience that is given to the person who experiences it. Does that imply a giver?

I am studiedly ambiguous about this. I am a Christian theist myself, so I suppose in one way that gives you your answer. But I think as soon as people start casting this issue as an issue in philosophy of religion, there’s a tendency for some rather uninspiring positive conceptions of God to get a grip, on both sides. And these positive conceptions put people off exploring the issues that epiphanies raise with fully open minds—either because they’re inclined to reject religion, and so introduce into the discussion a rather plaster-cast image of God that they want to reject, or because they’re sympathetic to religion, but for that reason are only too keen on the plaster-cast image.

When you’re known to be a believer, as I am, you tend to find yourself confronted with the kind of atheist who apparently thinks it very important that every believer should know that they’re an atheist. I quite often feel like telling that sort of atheist “I don’t believe in the God that you don’t believe in either.”

Hence the ambiguity. I just want to say, both to believers and to unbelievers: Well, hold on a bit. Don’t shut things down too fast with positive affirmations. Be prepared to be a little bit apophatic, to wait and see where things go in experience before you have formulated any particular intellectual verdict on what hasn’t even happened yet.

What do you think it means for someone if they don’t have epiphanic experiences?

Sometimes? Or at all? I talk a lot in the book about how natural it is for anyone only to experience epiphanies sometimes—and at other times to experience not only humdrum normality, but also troughs, lows, depressions. That’s natural enough; but could someone just never have epiphanies at all?

In one way the answer seems to be “Surely not.” I invite my reader to think of epiphanies as peaks in the line of experience over time, and it seems very unlikely that someone’s experience would have no peaks in it—would just be a flat line, straight or tilted. (It’s an interesting question, of course, what it is for something to be a peak in experience at all, or for that matter a line of experience or a level of experience, and the book talks about that, but I won’t try and answer it here.)

Or maybe someone might never experience epiphanies in the sense that though there are peaks, yet none of those peaks is objectively high enough to count as an epiphany? Well, that’s possible, but it doesn’t seem very likely from talking to real people. What seems much likelier to me is that people do have epiphanies, but don’t have the concept of epiphanies—they lack the descriptive tools to put it that way. Which loops us back to an answer I gave earlier.

Thinking about the philosophers you most admire: does their philosophy work through something like poetic expression?

“In my view, the real objective is not the epiphanies, the experiences of value, but the value itself, the world itself that the epiphanies are experience of.”

In some cases yes: Murdoch and Plato and Augustine are all obvious examples. In other cases no: Williams, MacIntyre, Aristotle, Aquinas, Descartes, Locke, Mill. It should hardly need saying that philosophy isn’t poetry and shouldn’t try to be. But for at least some philosophy, especially ethics, it seems right to say that if you don’t say it the right way, then you don’t say it at all; we treat style as mere adornment, but in some inquiries it’s a lot more than that—the style shapes the character of the inquiry itself. Again, at least some philosophy is—sometimes—about capturing the nature of human experience, and capturing that from the inside. Since this is exactly what poetry does, at least much of the time, there are clearly places where philosophy and poetry overlap.

Do you think philosophy should itself aim to offer or stimulate epiphany?

I think there are words to be said in warning about the danger of making epiphany into a directly pursued objective. The danger is that we make experience a kind of idol. We can pursue epiphany, maybe, but a certain indirection is necessary. In my view, the real objective is not the epiphanies, the experiences of value, but the value itself, the world itself that the epiphanies are experience of. Walter Pater famously said that “not the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end”; when he talks about “burning with a hard, gem-like flame” he means that he wants us to concentrate on our experience and ignore what it’s experience of. I couldn’t disagree more. That way, I think, lies a perversion of our faculties, a subjectivisation and a kind of solipsism of dilettantiste pleasure. This is why the last words in my book are Rainer Maria Rilke’s: No feeling is final.

But with those warnings in place, I think the answer to your question is that if any kind of writing should aim to offer epiphany, then philosophy should; why not?

Featured image by Zach Lucero on Unsplash, public domain

August 15, 2022

The nuclear egg: challenging the dominant narratives of the atomic age

While researching early Egyptian perspectives on nuclear weapons, I repeatedly came across the symbol of the egg. The atomic bomb, and atomic technology more broadly, was frequently imagined and drawn as an egg in the period after August 1945 in Egyptian magazines and popular science journals. Cartoonists, journalists, and even some scientists narrated the dawn of the atomic age through this recurring visual. The atomic bomb, some authors suggested incorrectly, was the size of an egg. The description of the atomic bomb as tiny likely emerged because of the association of atoms as miniscule, though others have offered more scientific explanations for the visual. Today, this visualization has largely faded, though it is still invoked in some jokes.

The image of the egg can be contrasted with other unrealistically small depictions, such as Albert Camus’s description of the bomb being the size of a football. However, it is notable that the mushroom cloud, considered to be the uncontested image of the nuclear age, barely featured in early Egyptian accounts of nuclearization. By going beyond this iconic image, which reflects the specific vantage point of the US, we can better understand the agency of actors typically seen as lying beyond the scope of nuclear politics. In a recent article published in a special section of International Affairs, dealing with Feminist Interrogations of Global Nuclear Politics, I discuss the implications of the visual of the egg, alongside several other images and metaphors that featured in Egyptian nuclear imaginations. In doing so, the article challenges the dominant narratives, histories, and aesthetics of the atomic age.

To begin with, the egg is associated with fertility and femininity. The reliance on the egg to describe the nuclear age, therefore, challenges the long-standing association between masculinity and nuclear weapons. The link between these two has become conventional wisdom in feminist nuclear literature since the publication of Carol Cohn’s article “Sex and Death” in 1987, which is based on an analysis of US military strategists, who use phallic imagery to discuss nuclear politics. But perhaps this link is unique to states that possess nuclear weapons. My research on Egyptian nuclear imaginations reminds us that for nuclear technology to be desirable, it does not necessarily have to be encoded within masculine symbols.

“The reliance on the egg to describe the nuclear age … challenges the long-standing association between masculinity and nuclear weapons.”

Nationalist modernizers in Egypt, like elsewhere, were enthusiastic about the atomic age. They used the symbol of the egg to highlight the promise of nuclear energy and nuclear technology for postcolonial nation-building. The symbol of the egg was used to highlight atomic technology’s usefulness in the creation of a modern nation. Atomic science was described through its potential applications for energy, architecture and urban planning, fertility and medicine.

In contrast with the visual of the football, the metaphor of the egg implies life within. Intellectuals embraced the dichotomy of nuclear energy as life-giving and nuclear weapons as life-taking. Despite their enthusiasm for nuclear technology, nuclear weapons were unsurprisingly associated with colonial violence. There was a stark distinction between how intellectuals depicted nuclear technology at the national level and how they saw it on the international level. When describing international nuclear politics, the bomb was drawn as a monster, a devil, or a rocket—scarier images that highlight the threat nuclear weapons posed to the decolonizing world. Through these depictions, global powers were depicted as irrational, immature, irresponsible—inverting the patronizing discourse of colonies being unprepared for self-rule.

“Nationalist modernizers in Egypt … used the symbol of the egg to highlight the promise of nuclear … technology for postcolonial nation-building.”

The bomb’s lethality was simultaneously linked to anxieties about women. The atomic bomb was likened to the “woman of the future”—described as slim, sleek, small; beautiful though also dangerous. Indeed, by the early 1950s, the atomic bomb had become part of everyday life and language in Egyptian popular culture. The 1951 film “My mother-in-law is an atomic bomb” capitalized on the sensationalism of the atomic bomb and popular interest in the subject. The film does not deal with nuclear war, and the term “atomic bomb” is only heard once throughout the film, as a metaphor of destruction. The film follows a power struggle between a man and his mother-in-law. It invokes her desire to be “the man of the house” as threatening and emasculating. Yet, the film ends with the mother-in-law subdued, suggesting that the couple was successful at taming and controlling her, a metaphor for nuclear technology.

Through these early images, we can obtain a more nuanced picture of nuclear histories in the Global South, which have long been overlooked. People in the Global South have participated in the production of the nuclear condition, but also in contesting and reshaping its parameters. Drawing links between gender, race, and the nuclear order, they have sought to imagine alternatives to the contemporary nuclear order. This is crucial for us to remember as we consider the long-lasting implications of the bombings of Japan, along with the legacy of nuclear testing, and amid continuous disputes over the Non-Proliferation Treaty, ahead of the 10th review conference.

August 14, 2022

Bequest: why did Shakespeare bequeath his wife a “second-best” bed?

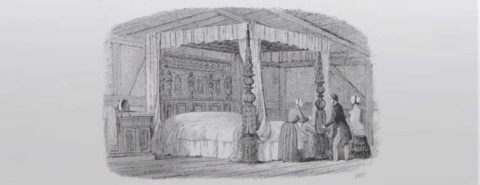

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.Why did Shakespeare bequeath his wife a “second-best” bed?

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.Why did Shakespeare bequeath his wife a “second-best” bed?One of the Shakespeare myths is that we have proof he despised his wife: when he died, he left her nothing more than “my second-best bed.” The story developed in part because of an early transcription error. For the 1763 Biographia Brittanica, Philip Nichols published a version of Shakespeare’s will taken from the official probate copy. He misread the handwritten text as “my brown best bed.” Thirty years later, Edmond Malone encountered the original will on which the probate copy had been based. Perhaps written at Shakespeare’s deathbed, the document was full of revisions and additions. For Malone, the original revealed two guilty secrets. First, the bequest to Anne Shakespeare was inserted like a grudging afterthought. Second, she received not a brown best bed but a second-best one. Malone believed that his paleographical skills had led to an explosive discovery about the Shakespeare marriage.

Malone also suspected that with the bed Shakespeare disinherited Anne, as if he had cut her off with a shilling. This Shakespeare could not do. Dower law ensured that for the length of her life Anne received one-third of all income from the substantial properties the couple had purchased during their marriage. Because dower could be overturned only when widows themselves surrendered their rights, many testators tried to bribe their wives to accept instead a capital sum of money or life tenancy in a room in the family home. As these wills show, dower had to be invoked in order to be revoked and, by declining to mention it, Shakespeare let it stand. His daughter Susanna and her husband John Hall later sold some of his land rights, but they had to wait until 1624, the year after Anne died. Until then, Susanna controlled just two-thirds of those rights because her mother held the remaining third.

To this legacy already settled in law, Shakespeare added a bed. In the wills of his time, beds and their accoutrements appeared frequently and were often pictured in loving detail. Since Shakespeare does not describe the bedframe, mattress, sheets, pillows, or coverlet, his family undoubtedly already knew which bed he meant. A best bed might have a full headboard and a mattress stuffed with feathers, while the second bed would have a half-headboard and a mattress stuffed with flocks. “Best” and “second best” were common ways of identifying beds; one man dictated that “I bequeath to John my said son the best featherbed and to Joan my wife the second, to Robert my son the third, and to Joan my daughter the fourth featherbed.” With “second-best” a testator did not insult his legatee; not even “worst” could do that. A principal heir might receive a valuable horse, a best cloak, a whole house, and a worst bed. Nor was the best bed always bestowed in affection. Some men who gave their best beds to their widows did so only if the women agreed “not to meddle nor make with no part of my goods.” Or the best bed might be conferred on condition that the widow vacated the family home within weeks of the testator’s death.

Since best beds were often reserved for guests, it could be that Shakespeare’s second-best bed was the marital bed. Alternatively, the bed could have belonged to Anne before the wedding. In a will in which a man assigns “three of my beds that were hers the said Margaret at our marriage,” we hear the reverberation of coverture—that is, property law for Tudor husbands and wives. What had been “hers” had become “mine” by virtue of “our” marriage. We cannot know whether this was true for the Shakespeares. He adopted the first-person possessive, “my second-best bed,” because that established his authority to make the bequest, but he gave the bed no biography.

Like any man of property, Shakespeare devoted most of his will to distributing lands and houses, not furniture or objects. The few exceptions were his wearing apparel, a silver-gilt bowl, his sword, and the bed. Although these seem like random bequests, eventually I found myself wondering whether they shared a painful connection.

Shakespeare’s only son, Hamnet, died at age 11. Once, Shakespeare would have expected the boy to grow into his apparel. He gave the clothing to his nephews instead. He had achieved gentle status, and, since only gentlemen were entitled to wear swords, he would have anticipated passing both the status and its symbol to Hamnet. He gave the sword to the son of a gentleman friend. Pieces of plate were baptismal gifts for people of substance. Shakespeare gave the silver-gilt bowl to the twin who was baptized with Hamnet, Judith. Was the second-best bed the bed in which Hamnet was born, even the bed from which he was taken to his grave? If so, the “random” bequests were all about the lost Hamnet, as every member of Shakespeare’s family—including Anne—would have known.

Featured image: 1850 living room and bedroom in Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, CC-BY-NC-ND Image Courtesy of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

The not-so-great caramel debate

I’m intrigued by the not-so-great debate over the pronunciation of caramel, which is instructive both socially and linguistically. Is the word pronounced with that second a, as caramel or without it, as carmel?

People rarely object to the first pronunciation, but the second is often cause for a scolding. The pronunciation carAmel follows the spelling, we are told. Don’t you see the a in the middle? Pronouncing the word as carmel means something different, a place in California, another objection goes. And fans of the three-syllable pronunciation will tell you that it is older and is connected etymologically to the French word caramel (meaning “burnt sugar”).

These are bogus objections to the two-syllable pronunciation, often raised by people looking to pick a linguistic fight. Plenty of English words have pronunciations that do not match their spelling, as any silent letter will tell you. And the existence of a city called and spelled Carmel. Many words can be pronounced in more than one way. The French etymology is a fun fact too, but history is no guide to a word’s contemporary pronunciation. We eat breakfast, not “break-fast,” and use handkerchiefs not “hand-kerchiefs.”

What about dictionaries? The three-syllable pronunciation of caramel is the only one given in the 1934 Webster’s Second International Dictionary. However, both options appear in the 1961 Webster’s Third, though the two-syllable one is marked with an obelus (a ÷ sign). That signaled the dictionary editors’ feeling that it was “a pronunciation variant that occurs in educated speech but that is considered by some to be questionable or unacceptable.” The current online Merriam Webster gives both the two-syllable and three-syllable variants. So, dictionary-wise, the expert opinion today is that either pronunciation is fine.

“History is no guide to a word’s contemporary pronunciation.”

The carmel-caramel issue sometimes comes up in regional dialect studies. Bert Vaux’s 2003 Harvard Dialect Study crowdsourced opinions about 122 variable features of English pronunciation, grammar, and word usage. Of the 11,609 people who responded to his question about caramel, 38.02% said they pronounced it with two syllables (as “car-ml” in his prompt) and 37.66% said they pronounced the word with three syllables (as “carra-mel”). Vaux documented some regional variation, with respondents in New England, the Mid-Atlantic states, and the South tending to have more three-syllable pronunciations and those in the West, the Midlands, and the inland North having more two-syllable pronunciations. Some of the respondents also said they used both pronunciations interchangeably—17.26% of them.

There is another wrinkle as well. Some speakers have told me that the two- and three- syllable pronunciations actually have different meanings. In my experience, they tend to be people who know their way around a kitchen and have some experience baking. For them, the two-syllable version refers to caramel in its solid form—the little square candies made by Kraft, or the glaze on caramel corn or a caramel apple. Three-syllable caramel is the liquid form or the flavoring, I’m told. Bert Vaux’s survey also noticed that nearly 4% of his respondents said that the two forms had different meanings, but he did not report what the difference was.

If you add together the folks who can pronounce caramel either way and the ones who make a semantic distinction between solid and liquid, that comes to about 21%. The rest of the those surveyed seem to have a preference. But that’s all it is at this point: a preference.

The not-so-great caramel debate has been around for a while. If you search newspaper databases for “pronounce caramel,” you’ll find worried readers asking about the so-called correct pronunciation of caramel as early as the 1950s. Perhaps this was because radio and television’s Kraft Music Hall promoted its caramels using an announcer who was a two-syllable man. Lexicographer Bergen Evans, answering a 1959 query about the word, explained that the two-syllable version “is used by so-many well-educated American that it must be accepted as a permissible alternative.”

It’s worth noting too that some people also worried about whether chocolate should have two or three syllables.

What do you say?

Featured image: “Beautiful sunset at Carmel by the Sea” by David Balmer. CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers