Oxford University Press's Blog, page 70

September 7, 2022

Etymology gleanings for August 2022

Spelling

SpellingAfter posting the most recent essay on Spelling Reform, I received rather many comments, all of them friendly. I keep thinking that a reasonably cautions reform will meet with little opposition. Who will weep if acknowledge loses its c and build becomes bild? One can imagine a plan that will appear as a set of proposals divided into several groups, something like this:

Would you agree to changing build to bild?Would you agree to changing scold to skold?Would you agree to changing occurrence to ocurrance?Would you agree to eliminating the letter q and substituting kw for it (akwaintance, kwik) and to comitee instead of committee?And so on, about some mute letters and double letters, and many other things. This questionnaire, if published in two or three influential newspapers and online, will invite a flood of responses, both friendly and hostile. The agreement by, let us say, 70% of the public will guarantee (“garantee”) the success of the enterprise. The reformers should be pragmatic and try “to do no harm.” The public must be cajoled into accepting the change, rather than broken in. In principle, society is always against such a measure (? mezure), and no reform will satisfy all. For instance, in British English, due and Jew are usually homophones (I am horrified when I hear that I must pay my JEWS), and in American English, due is a homophone of do (and a typical letter from a student is: “When is the paper DO?”)—I have once written about this. Reform or no reform, all such problems will remain.

I may also answer some general questions submitted rather long ago. They address the connection between the written and the spoken language. In a society in which practically all people are literate, language perhaps develops more slowly than in preliterate societies. School slows down change, and we even have cases of spelling pronunciation (often, and its likes). “Received pronunciation” also has some prestige. However, at present, we are very egalitarian, the use of dialect in public is not condemned, and so on. In principle, language changes despite the best efforts of the cultural elite. The tremendous gap between written and spoken English, as we today know it, shows that spelling, the accepted norm, does not prevent language from evolving in the most radical way. This is why at least some version of spelling reform becomes necessary. Anyone will agree that it is irrational to say quire and write choir.

Umbrella and its kin Sarie Gamp and her brolly.

Sarie Gamp and her brolly.(“Harry Furniss’s study of the great comic creation for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)”, Sairey Gamp. Via The Victorian Web, public domain.)

Some time ago, I received a question about English umbrella and parasol. Why not parapluie? It seems that no one can explain why a certain word has not been borrowed, but the history of umbrella and its kin is curious. Both English words—umbrella and parasol—refer to a device meant to protect people from the sun (umbra “shade,” sol “sun”). Para– is a Romance prefix. It is the same element we see in the root of the verb prepare. Too bad, English did not make use of parapluie: in a country like England protection against bad weather (rain) is more “relevant” than a sunshade. To a northerner, German Regenschirm “rain’’ + “screen, protection” makes better sense than parasol or umbrella. Curiously, Russian zontik “umbrella” and “parasol” was borrowed from Dutch zondek “awning,” and obviously, referred to the sun (zon-), though in Russian life, too, umbrellas are mainly associated with rain.

A particularly striking development in this saga is the emergence of the word gamp “umbrella.” As is known, the word goes back to Sairey Gamp, an unforgettable nurse in Dickens’s novel Martin Chuzzlewit, a drunk and an impostor. She always carried a huge umbrella, certainly, not a “sunshade.” The final step in the degradation of umbrella is the form brolly, which I have cited more than once in this blog, to illustrate my inability to explain the change of e to o (the same in American frosh “freshman”). I am sorry that I talked so much around the question instead of answering it. If I knew the answer, I would have come straight to the point. The fact remains that English did not borrow parapluie, and probably no one knows why.

On mandibles Keep your cheeks and the rest of your anatomy away from its jowls.

Keep your cheeks and the rest of your anatomy away from its jowls.(Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The reward for my recent post (31 August 2022: “Cheek by jowl”) was two emails. I wrote, most incautiously, that jowl has almost no existence outside the idiom and was reminded that a bulldog’s jaws are called jowls. Quite true. The other letter mentioned hog jowl and black-eyed peas, the traditional dish for New Year’s Day in some southern states. Since I was the only recipient of those letters, I thought it reasonable to publicize the content of both.

Finally, a small addition. In the post, I wrote that we do not know how Shakespeare pronounced jowl but that he probably rhymed it with bowl, because such is the more archaic American pronunciation. I should have made a more definite statement. One of the spellings of jowl in Shakespeare’s texts was jole.

Sound imitation and sound symbolismThe comments on the post “The Human Aspect of Etymology” were rather numerous and very much to the point. Indeed, nothing can be predicted in this sphere. A sn- and a sl-word can be devoid of any emotional coloring, evoke pleasant emotions, or fill us with disgust. With words like drip/drop, drivel, and drizzle, we don’t expect drool to refer to anything solid. But drones don’t drivel, drums don’t drool, and driver has almost become a synonym of “human being.” I was also asked to recommend one or two books on such matters. Since each of the posts in this blog advertises my book Word Origins…, may I risk recommending chapters 3 and 4 in it? They deal with sound imitation and sound symbolism.

IdiomsOne of our correspondents wrote that she enjoyed my discussion of idioms and asked whether there would be more posts on this subject. Probably not. My dictionary of English idioms, published by the University of Minnesota Press, is due (“do”) to appear any day now, and there is no use milking it for more examples. But to illustrate how amazing the assortment of idioms is, I may cite the following.

A scene in Topsham or Warsop?

A scene in Topsham or Warsop?(Photo by Ihor Malytskyi on Unsplash, public domain)

“Do you come from Topsham”? This is or was said to those who leave the door open. Topsham is in Devonshire, but the phrase was recorded in Yorkshire (!). The name Topsham does not contain a pun, so that the origin of the question remains a puzzle. Even more puzzling is the fact that this is a migratory formula. The place name seems to be arbitrary, but the genre (the door-shutting proverb) is well-known, though I have only one more example. In Nottinghamshire, they used to say (my examples go back to the beginning of the twentieth century): “I see you come from Warsop way; you don’t know how to shut doors behind you.” I have not been able to find any explanation of such phrases in folklore. If our readers know more such phrases or are aware of their origin, their comments will be appreciated.

Featured image via rawpexels (public domain, CC0).

September 6, 2022

Unmanly men and the flexible meaning of kinaidos in Classical antiquity

The kinaidos (cinaedus in Latin) was the homosexual “bogeyman” of Greco-Roman literature: a man so willing to be sexually penetrated by other men that scholars think he was perhaps just an imaginary figure. Reading more broadly, however, we can see that men bearing this identity marker did exist in antiquity. Financial records, letters, and even a dedicatory message on a temple wall complicate our understanding of this ancient sexual and social deviant.

In fourth-century BCE Athens, the orator Demosthenes is labelled a kinaidos in the courtroom by his opponent in order to besmirch his masculinity and accuse him of shameless conduct. In the Gorgias, Plato cites the “life of the kinadoi” as being the prime example of hedonistic living. Roman authors are more detailed as to what exactly makes the cinaedus’ behaviour so wretched: Catullus, Martial, and Juvenal all portray cinaedi as desiring sexual penetration by other men and often as displaying extreme effeminacy.

The word “cinaedus” also occurs frequently in insulting graffiti on the walls of Pompeii. Appearing more than 30 times, it is often accompanied by the name of the specific individual it mocks. On occasion a little more information is provided. For instance, a graffito uncovered recently reads: NICIA CINAEDE CACATOR. Nicia, or Nicias, is a personal name, that it is Greek suggests it may have belonged to an enslaved person who had subsequently been manumitted. A cacator is a person who defecates. Therefore, this slur, “Nicias, a cinaedus and a crapper,” bluntly attacks an individual as being filthy in his social, sexual, and digestive behaviour.

Painting of a dog with the inscription NICIA CINAEDE CACATOR above it.

Painting of a dog with the inscription NICIA CINAEDE CACATOR above it.(Via pompeiisites.org)

Yet if we turn to Egypt during Ptolemaic and Roman rule, the word kinaidos is used in very different contexts and so takes on a rather different meaning. Instead of being used as a negative slur, the term appears in several financial documents as a way of identifying particular individuals. A pot sherd and a papyrus survive in which kinaidoi are recorded as paying tax contributions. More interesting, however, are the documents in which payment is made to kinaidoi and which demonstrate that they provided some form of valued service. Since their appearance in these documents is accompanied by mention of pipe players it can also be inferred that they were hired to provide some kind of entertainment be that song, dance, or some combination of the two.

The notion of the kinaidos as a specific kind of performer is corroborated elsewhere. The Roman poets Martial and Juvenal specifically associate this individual with a particular form of dance in which the cinaedus wiggles his buttocks salaciously. He is also connected with a particular kind of poetic speech that is noted by the ancients for its racy rhythms and is employed for parodic, and sometimes pornographic, content. However, in a letter to a friend complaining about such tawdry entertainment, Pliny the Younger states that such performances (though not to everybody’s taste) ought to be tolerated at other people’s parties. He writes that although “in no way does it please me if something effeminate is performed by a cinaedus”. . . “let us pardon the amusements of others so we may obtain the same pardon for our own” (9.17).

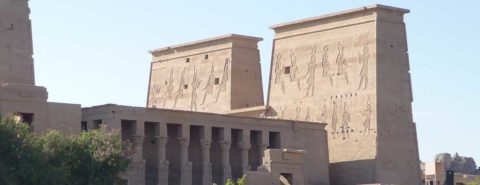

Frustratingly, all of these mentions are examples where the term kinaidos is applied externally. Only two examples of men self-identifying as kinaidoi exist in the ancient record. As with the financial documents mentioned above, this evidence comes from Egypt: at the temple of Isis at Philae located at the southern-most edge of the Roman world. In around 5 CE two kinaidoi left their names in messages scratched amongst countless others left by pilgrims to the site. Their words read: “Tryphon son of the same, the god’s kinaidos I came to Isis of Philae,”“Strouthion the kinaidos I came with Nikolaos” (I.Philae II 154–5). The names of these two individuals are also quite telling. Tryphon derives from the Greek word, tryphē, meaning “daintiness” and Strouthion from strouthos which can mean either sparrow or ostrich. Such names certainly give an impression that their bearers could have been somewhat effeminate or extravagant.

If Greco-Roman authors single out the kinaidos as a bad example of masculine behaviour across a spread of centuries, this does not necessarily provide a complete picture. As noted, graffiti from Pompei corroborate this term as being negative and carrying with it a sense of shame. However, by reading around our extant sources, another type of figure comes into view: one who pays taxes and therefore sits officially within a fiscal framework; one who is renumerated (and most likely valued) for his appearance alongside pipe players in performance settings; and finally one who exhibits a sense of pride in completing his pilgrimage to the temple of the extremely popular goddess Isis in the early years of the Roman empire.

Feature image: Isis temple from lake, Philae Island, Egypt, by Rémih from Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 1.0

September 5, 2022

Four ways machine learning is set to revolutionize breast surgery

Machine learning has grown to become quite the buzzword in clinical research. Across recent years, we’ve seen an almost exponential increase in the number of successful machine learning trials conducted, with the technology now hailed as a torchbearer for healthcare’s artificial intelligence revolution. Yet, this begs an obvious question for doctors and healthcare professionals alike—what actually is “machine learning”?

Machine learning refers to the concept of using large amounts of data to build elaborate algorithms that aim to mimic the way the human brain thinks. Whilst the ground-breaking technology has had an undeniable impact across many aspects of surgery, its implementation in breast surgery is one crucially yet to be established.

Below, we distil down four ways we see machine learning revolutionizing the day-to-day operations that a breast surgeon undertakes.

1. Planning before surgeryImaging plays a phenomenal role in planning for any major breast operation—whether it be from pinpointing the location of a breast tumour to helping a surgeon navigate complex breast anatomy. Radiologists now have access to swarms of imaging data to aid the former, thanks in part due to modern imaging techniques. Nonetheless, it can be time-consuming to process this information before a surgery is planned.

New machine learning technology aims to bring greater efficiency and accuracy to this process. Initial trials suggest that machine learning performs to the same level if not better than a radiologist in detecting cancer, and also shows a higher sensitivity (i.e. a better ability to detect cancer in an individual that actually has cancer). Not only will this provide surgeons with prerequisite knowledge to make smarter treatment decisions but will lead to reduced workloads, a reduced burden on resources, and reduced chance of error.

“Diagnosis: Biopsy: Breast,” by Linda Bartlett via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.2. Making long-term predictions

“Diagnosis: Biopsy: Breast,” by Linda Bartlett via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.2. Making long-term predictionsClinicians always want to ensure what they do is backed up by strong evidence—one of the reasons why so much time is spent applying traditional statistical ideas to monitor and predict what might happen to patients after their breast surgery operations.

Whilst a relatively new phenomenon, machine learning looks promising as a gamechanger within this field. New trials suggest it predicts five-year mortality after breast cancer operations more accurately than statistical models and have even gone on to suggest it can predict a patient’s chance of developing a complication like lymphoedema (a long-term swelling in the tissues of the body after an operation).

All of this has been down to the creation of a specific type of machine learning dubbed an “artificial neural network”—a type of machine learning modelled after a human brain cell called a neurone.

3. Holistic careWith the growing recognition of how important it is that we apply a holistic attitude to treating anyone, machine learning holds an important key. Pain following breast operations can be a debilitating experience and is often something we don’t investigate as much as we ought to. Research has suggested machine learning can allow us to predict neuropathic pain, a type of pain that results from nerve damage, more quickly after an operation. This could allow surgeons and doctors to provide more optimised support to patients in the recovery period.

4. Beyond predicting and planningThe potential applications of machine learning to breast surgery are vast and boundless, and some ideas have applied machine learning concepts in exciting and innovative ways. With advances in medical research, come a wealth of new treatments. Conceptual studies suggest that machine learning can be integrated in decision-making support systems for breast surgeons, including examples such as the “DESIREE Project”, that aim to simplify the process of choosing specific therapeutic options.

Alternatively, machine learning has predicted that the more times a breast surgeon has carried out a specific operation before improves the long-term success of their patients after surgery. It is now theorised that machine learning can be used to study the technique of more experienced surgeons and use this information in the training of inexperienced surgeons.

By vpnsrus.com, via Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

By vpnsrus.com, via Flickr, CC BY 2.0.So, where does this leave us? As exciting as this technology sounds, it is still limited by its relative infancy and hence shrouded in challenges.

It comes with no surprise that machine learning is complicated. Before any of this technology can move forward, we need to ensure breast surgeons are equipped and trained with extensive knowledge on how to utilise it. Stakeholder collaboration will form a major part of designing a practical machine learning platform ready for clinical use. In addition, machine learning is inherently driven by data and hence it is our shared responsibility to ensure any data fed into it is as reliable and representative of our target population as possible.

Nonetheless, it’s certainly an exciting time to be a breast surgeon and we can’t wait to watch machine learning’s trajectory in overhauling patient care in the not-so-distant future.

Featured image by Irwan iwe, via Unsplash.com, public domain.

September 4, 2022

Four Very Short Introductions podcast episodes to get you thinking

What does atheism mean to you? Is logic ancient history? How is Calvinism changing the world? Put your thinking cap on, earbuds in, and get listening to our curated collection of Very Short Introductions podcast episodes for thinkers.

These four episodes—each under 15 minutes long—created by our expert authors offer bite-sized introductions to four big concepts: atheism, logic, secularism, and Calvinism.

Listen to the podcast episodes below or subscribe and listen to the Very Short Introductions podcast through your favourite podcast app.

1. AtheismIn this episode, lapsed Catholic, failed Methodist, and convinced atheist Julian Baggini introduces atheism, wrongly considered to be a negative, dark, and pessimistic belief characterized by a rejection of values and purpose and a fierce opposition to religion.

But if atheism is not religion’s inverse, what does it mean to be an atheist?

Listen to Julian explain the “historical accident” of atheism’s emergence in Western civilization and how we can understand atheist worldviews and beliefs.

Or subscribe and listen to the “Atheism” Very Short Introductions podcast episode on your favourite podcast app now.

2. Logic“God, time and change, truth and existence, language and paradox… What I love about logic, personally, is the fact that it has these deep connections to profound philosophical questions.”

In this episode, Graham Priest introduces logic, an area which is often wrongly perceived as having little to do with the rest of philosophy and even less to do with real life.

Listen to Graham explain what exactly “logic” is, why it’s so integral to our everyday lives, and how he encapsulated this simultaneously ancient and modern subject in a Very Short Introduction.

Or subscribe and listen to the “Logic” Very Short Introductions podcast episode on your favourite podcast app now.

3. Secularism“[Secularism] is about the state maximizing freedom of conscience, freedom of thought, freedom of religion or belief for everyone regardless of their religion or belief, up to—and only up to—the rights and freedoms of others.”

In this episode, academic and activist Andrew Copson introduces secularism, an increasingly hot topic in public, political, and religious debate across the globe that is more complex than simply “state versus religion.”

Listen to Andrew explain why we must not neglect secularism and why debating and discussing secularism is of pivotal importance for world civilization today.

Or subscribe and listen to the “Secularism” Very Short Introductions podcast episode on your favourite podcast app.

4. Calvinism“Calvinism may seem arcane but in fact as recently as 2019, Time magazine chose Calvinism as one of 10 ideas that were changing the world. But that still may not mean people know a lot about it…”

In this episode, Jon Balserak introduces Calvinism, which has gone on to influence all aspects of contemporary thought, from theology to civil government, economics to the arts, and education to work.

Listen to Jon set out the character of Calvinist thought and offer critical assessment of it in this bite-sized introduction to the subject.

Or subscribe and listen to the “Calvinism” Very Short Introductions podcast episode on your favourite podcast app.

Want to learn more? Subscribe to The Very Short Introductions podcast and see where your curiosity takes you!

Featured image by Jusdevoyage on Unsplash, public domain

September 3, 2022

East and west the preachers mouth: St. Anne Blackfriars in early modern London

When we imagine the built environment of Early Modern London, we tend to think of the hundred or so church buildings that dotted the City as free-standing Anglo-Norman structures set within walled churchyards. But as John Schofield has demonstrated, “the majority were small, on constricted sites and often partially hidden from the street.” The church of St Anne’s Blackfriars is a good example of how actual churches might fall short of an imaginary “norm.”

St Anne’s only became a parish once Henry VIII closed the friary in 1535. Before then, non-religious residents of the ecclesiastical precinct had worshipped in part of the friars’ own conventual church. When that church was either demolished or turned into a private home, parishioners needed a new place of worship. They eventually found one in the upper story of the former chapter house. We know from contemporary sources that this “little church or chappell up stayres,” as described by law student John Manningham in 1602, was originally 50 ft in length by 30 ft in width. The church building was enlarged several times in the next century, until it measured approximately 86 ft from north to south, and 54 ft from east to west. Unlike most conventional Anglo-Norman churches in London and elsewhere, then, St Anne’s north-south axis was significantly longer than its east-west.

“The experience of churchgoing at St Anne’s was undoubtedly shaped by the unconventional layout of the place of worship, but in ways that are now hard to recover.”

This fact was clear to critics of the Puritan clergy who dominated the Blackfriars pulpit for years. One wit observed of St Anne’s that the “Church stands North and South, / And East and West the Preachers mouth.” This odd joke about the alignment of the preacher’s mouth implies that he stood facing the congregation with his back to either the north or south wall. Whether we are to picture him standing in his pulpit or in front of the communion table is unclear. The fact that parishioner Gideon Delaune was granted the “second pew to the pulpit southward” in 1618 might indicate that the pulpit was in the north of the church. It certainly implies that the pulpit—rather than the altar or communion table—was the liturgical center. Such an arrangement means that St Anne’s did not conform to the traditions of Anglican sacred space.

The experience of churchgoing at St Anne’s was undoubtedly shaped by the unconventional layout of the place of worship, but in ways that are now hard to recover. Embodied religious experience unfolds in particular spaces and on particular occasions. St Anne’s parishioners may have considered the unorthodox nature of their worship space an unhappy accident or may just as readily have imbued it with symbolic value, making it a focus of their collective identity.

Lived religion in St Anne’s was shaped not only by the interior layout of the church, but also by other buildings and institutions close by. St Anne’s churchgoers were always mindful of the nearby Blackfriars playhouse, which residents had feared before it opened would disturb divine service with the players’ drums and trumpets, even though the playhouse was to be fully enclosed in a separate part of the old friary. The churchgoers would also have been mindful of the space beneath their feet, for when they had added a new western aisle to their church, they also built “a faire Ware-house” underneath for Sir Jermone Bowes who operated a glasshouse and furnace in an adjacent vault. One wonders whether the intense heat and pungent smells ever infiltrated the church?

The warehouse under St Anne’s church was one of many examples of how secular spaces could press in on places of worship. Churches might share walls with shops or have only the narrowest of passages between them and domestic dwellings. Several churches rented out their vaults, crypts, and cellars for secular use. For instance, St Mary Colechurch on Cheapside, which like St Anne’s was entered via a staircase, was built over a crypt occupied by the Mitre Tavern. The Mitre also had rooms above the church. Could churchgoers hear the carousing customers above? We do know that near St Anne’s, where at least one tavern commanded a view of the church porch, proprietors were warned not to “carry on their trade in time of divine service.”

With shops, homes, and halls often surrounding church buildings, Londoners must have found it difficult to think of and treat sacred space as separate from and untouched by the secular realm. Inevitably, the sights, sounds, and smells of quotidian reality pressed in upon what we tend to think of as the secluded stillness of religious space. The St Anne’s preacher Stephen Egerton urged his congregation to think of their church as a “holy sanctuary.” But in many cases, this sense of the sacred as a protected sphere may have been more a wish than a reality.

Featured image: Painting by Percy William Justyne, Crypt of St Anne, Blackfriars, City of London, public domain.

September 2, 2022

Formerly incarcerated women of color face worse health in later life

In 2021, Harlem-based activist Shawanna Vaughn stated during a Forbes interview: “Walking into prison at 17 was the most traumatic experience of my life…As a person who suffers from the remnants of mass incarceration, I am very clear that the trauma starts before prison and lingers forever until there is help.”

Incarceration takes a heavy toll on one’s mental and physical health. The conditions of jails and prisons in the United States have long been known to increase risk of infectious disease and erode mental health. However, even among formerly incarcerated adults, we observe stark health disparities including higher rates of chronic diseases and premature mortality, which suggests that incarceration has far-reaching health consequences.

Starting in the 1970s, major shifts in legal policies, including harsher drug penalties, led to an explosion in the penal population. In two short decades, the number of Americans incarcerated nearly quadrupled, with disproportionate representation of racial and ethnic minorities. This rapid growth in incarceration has since been dubbed “mass incarceration.” The US now holds the distinction of having the highest incarceration rates in the world—with the vast majority of incarcerated people being convicted of nonviolent crimes.

As a result, a growing share of older adults are now aging with incarceration histories and poor health. We are just now seeing the long-term health consequences of mass incarceration policies—the “remnants” that Vaughn described. However, this trend will continue as the cohorts most affected by mass incarceration are growing older. Although men are incarcerated at higher rates, women experience greater health burdens following incarceration. This is doubly true for older women of color.

Previous research posits that women’s health declines following incarceration are attributable to institutional sexism and racism within the penal system. These health declines have been well documented in younger samples, but little research has explored whether the effect of previous incarceration varies by gender and race/ethnicity among older adults. To fill this gap in the literature, we used data from a nationally representative sample of Americans over the age of 50 to examine differences in mental health, measured as number of depressive symptoms, and physical health, measured as number of physical limitations like difficulty walking, by incarceration status, gender, and race/ethnicity. With nearly 12,000 respondents from the 2012/2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), we were able to document important health disparities among older adults.

“This research highlights how sexism and racism lead to unequal health following incarceration.”

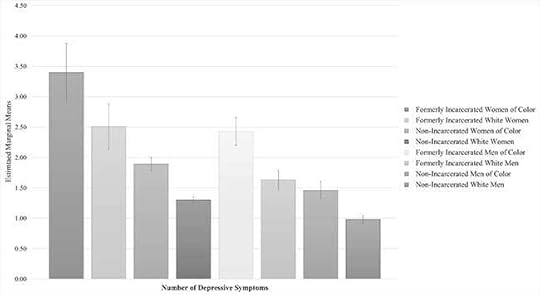

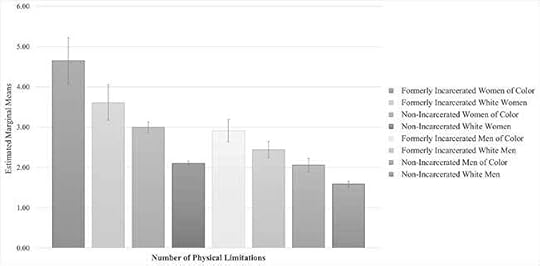

We found that formerly incarcerated older adults had worse mental and physical health than their peers who had not been incarcerated. Moreover, formerly incarcerated women reported worse mental and physical health than formerly incarcerated men—even after controlling for a host of social, economic, and early life factors. When we investigated differences by gender and race/ethnicity, we observed startling disparities among formerly incarcerated women of color. On average, formerly incarcerated women of color experienced an additional depressive symptom and physical limitation to the next highest group (formerly incarcerated white women) and more than triple the number of depressive symptoms and physical limitations as the healthiest group (non-incarcerated white men).

Figure 1. Age-adjusted estimated marginal means for number of depressive symptoms by incarceration-gender-race/ethnicity groups

Figure 1. Age-adjusted estimated marginal means for number of depressive symptoms by incarceration-gender-race/ethnicity groupsIn Figure 1, we present the age-adjusted marginal means for depressive symptoms (range=0-8) by respondents’ incarceration, gender, and race/ethnicity status. Controlling for age, formerly incarcerated women of color reported nearly three-and-a-half depressive symptoms when surveyed; whereas, formerly incarcerated white women and formerly incarcerated men of color reported about two-and-a-half depressive symptoms. A similar pattern emerged for physical limitations (range=0-9). In Figure 2, formerly incarcerated women of color reported having approximately 4.7 physical limitations. For context, the average number of physical limitations for the entire sample was two physical limitations. These high levels of depressive symptoms and physical limitations put formerly incarcerated women of color at greater risk for clinical depression and self-care disability.

This research highlights how sexism and racism lead to unequal health following incarceration. The results of this work indicate that older adults aging with incarceration histories experience worse health; however, formerly incarcerated women of color face the greatest health disadvantage among all the formerly incarcerated groups. These health inequities are the result of decades of policy choices that have disproportionately harmed women of color.

Figure 2. Age-adjusted estimated marginal means for number of physical limitations by incarceration-gender/sex-race/ethnicity groups

Figure 2. Age-adjusted estimated marginal means for number of physical limitations by incarceration-gender/sex-race/ethnicity groupsThe implications for public health policy are clear. By specifying those groups that are rendered especially vulnerable, we can better direct resources, such as targeted mental and physical health interventions for formerly incarcerated women of color. Because men are incarcerated at higher rates than women and more attention is paid to early-life incarceration experiences, formerly incarcerated older women may be an overlooked population who have not benefitted from current initiatives aimed at improving the health of formerly incarcerated adults.

Furthermore, we encourage policymakers, healthcare providers, and community organizations to take a life course perspective to incarceration and health. Re-entry or transitional programs for post-incarcerated people are often short in duration and do not recognize the need for consistent care and support into later life—possibly long after incarceration has taken place. Our work also suggests that decarceration and abolition should be key priorities for public health. Critical scholarship in the social sciences has only confirmed what post-incarcerated people like Shawanna Vaughn know from experience: that prisons do not (merely) punish crime, but also exacerbate inequality through the production of poor health.

Featured image by Ye Jinghan via Unsplash, public domain

September 1, 2022

Infinite potential: logic, philosophy, and the next tech revolution

We live in the information age, the product of the modern computer. The modern computer is itself a product of modern logic, which underwent a revolution in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This revolution was driven by logicians and mathematicians: George Boole (whose Boolean data types are so important to computing) and Augustus de Morgan in Britain, Gottlob Frege and David Hilbert in Germany, and Kurt Gödel in Austria, among many others. As well as logicians and mathematicians, these thinkers were philosophers. They revolutionised logic based on their philosophies.

About a century ago, then, our world was transformed by a logical revolution, which may broadly be called philosophical. This transformation was the key to the technological advances of the past century. When, in 1936, Alan Turing wrote the seminal article in which he introduced the idea of a “computing machine” (now known as a Turing Machine), he was responding to a question posed by one logician (Hilbert) by reworking the tools of another (Gödel).

What about today’s logic? Could current advances in logic or its philosophy lead to the sort of computer-driven technological change we’ve seen in the past hundred years?

“Could current advances in logic or its philosophy lead to the sort of computer-driven technological change we’ve seen in the past hundred years?”

In some ways, the question is easy to answer. Logic is now a huge, sprawling subject, with logicians housed in mathematics, computer science, philosophy, and cognitive science departments. It is a major branch of philosophy and a crucial component of any philosophy degree. It advances every day, and these small daily advances accumulate over time to result in significant technological change. Neural networks and deep learning are products of these changes and have already revolutionised the field of Artificial Intelligence.

As philosophers, though, our interest is in the conceptual foundations of logic. And we think that twenty-first century logic is still shackled by an understandable but erroneous assumption. This erroneous assumption is that logic is finite. Yet far from being finite, logic is infinite, as we argue in our recent monograph One True Logic. Appreciating logic’s infinitude should lead to a conceptual revolution in logic, and potentially to a technological one. Rethinking the conceptual foundations of logic could revolutionise technology in the twenty-first century just as it did in the twentieth.

Let us explain. A logic is in many ways like an ordinary language such as English, Arabic, Spanish, or Mandarin. The feature of a logic most relevant here is that it contains some vocabulary and some rules for stringing together its vocabulary—a grammar. In English, an example of a grammatical rule might be: if A is a sentence and B is a sentence, then “A and B” is a sentence; so, for example “Fido is a dog and Felix is a cat” is a sentence since “Fido is a dog” and “Felix is a cat” both are.

An exactly analogous rule applies in logic, which allows two shorter sentences to be joined by “and”—or its formal counterpart—to form a longer one. And logic provides many other ways of building longer sentences. But if logic is finite, then these sentences must be of finite length. We cannot, for example, have a sentence containing “and” infinitely.

“Twenty-first century logic is still shackled by an understandable but erroneous assumption. This erroneous assumption is that logic is finite.”

Inspired by thinkers such as Alfred Tarski and Gila Sher, we think that restricting the correct logic to finitely long sentences is a mistake. There is no chasm between finite and infinite. In fact, the correct logic is not merely infinite; it is in a sense maximally infinite. It allows the conjunction of any infinite number of sentences. It is as infinite as can be. Or so we argue in One True Logic.

There’s an interesting historical resonance to our thesis that logic is infinite. Quite a few early twentieth-century logicians, including Zermelo, Löwenheim, Skolem and even Hilbert, were all at one point happy to use infinitely long sentences. Although this aspect of the modern pioneers’ work was important at the time, it was later ignored—almost airbrushed out of logic’s official history.

What are the technological consequences of taking logic to be infinite? We don’t know for sure. Clearly, we cannot expect anything like current computers to process an infinite amount of information. But there is no reason why they couldn’t mimic reasoning with infinitely long formulas of the sort we are all capable of. An infinitely long sentence must, for example, imply itself.

What is the upshot? We know from the history of our subject that philosophical advances in logic can and do lead to technological advances, which nobody could have foreseen. We believe logic is infinite, indeed maximally so. All that remains is to find a twenty-first century Turing to show where this leads.

August 31, 2022

Cheek by jowl

I have known the phrase cheek by jowl all my life but never heard it said by anyone, and yet the history and especially the pronunciation of jowl could serve as the foundation of a dramatic plot. The word goes back to Old English, where it had the form cēafle. After a series of changes, it emerged in two forms: one rhymed with Modern English bowl and the other with fowl. The British norm adopted the second variant, but in America, both pronunciations exist. At least, such is the evidence of all dictionaries. The word has no or almost no existence outside the idiom, which appeared in texts in Shakespeare’s lifetime, but we don’t know how he pronounced it. The American pronunciation is often archaic and therefore closer to Shakespeare’s. Cheek by jowl means “cheek by cheek” (hence “in close proximity, side by side”). When such synonyms occur “side by side,” as happens, for instance, in safe and sound, alliteration reinforces the message and disguises the near-tautology.

Cheek by jowl should also have alliterated and become approximately cheek by chowl (see Old English cēafle, above; the form chawl has been recorded), and no one knows why jowl acquired a voiced initial consonant. As a general rule, English words with initial j are either of Romance origin (like joy, joust, jejune, and so forth) or upstarts with a questionable pedigree (like job, jig, jump, and the rest). The irascible Walter W. Skeat, our greatest English etymologist of the past, wrote at jowl / jole that all the forms are corruptions of Middle English chol, chaul. Nineteenth-century historical linguists constantly used the word corruption. We say alteration not because we try to sound politically correct, like the rest of the modern civilized world, but because every change “corrupts” the older form and the older state. Middle English is a corruption of Old English, Old English is a corruption of Common West Germanic, and so it goes.

A most functional ancient jaw.

A most functional ancient jaw.(Comparison of Modern Human and Neanderthal skulls from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Jowl, despite its j-, is Germanic and even West Germanic: it has a close counterpart (cognate) in Dutch. Several good dictionaries also cite cognates in Baltic, Slavic, and beyond, but those are questionable, and it is better to stay away from them. Yet some words with a different root vowel seem indeed to be related. Such is, for example, German Kiefer “jaw,” part of a rather extended family. Perhaps the ancient root was gop. Allegedly, it imitated the snapping sound made at biting and at any quick movement. I regularly and willingly trace the words discussed in this blog to sound-imitative complexes, but here, this reconstruction would be rather insecure. If, however, it is allowed to stand, then English chafer, Dutch kever, and German Käfer (explained as “gnawers”), with their pre-Germanic root gop, belong here too. After all, beetle is, from the etymological point of view, a biter, and biting is at least sometimes accompanied by the noise of moving jaws.

Cheek by jowl.

Cheek by jowl.(Photo by Anna Hecker on Unsplash, public domain)

Next to jowl, we find the similar-sounding English jaw. But jaw appeared only in Middle English, in the form iow, in which i stood for j. By the way, Old English ceaflel meant both “cheek” and “jaw”! For two reasons, it is usually believed that jaw is a borrowing from French. First, the word is late (no corresponding form occurred in Old English; it would certainly have emerged if it had existed). Second, we note the treacherous initial j, which has given us some trouble in dealing with jowl. Only Friedrich Kluge, the main German etymologist of the past, believed that jaw is a regular continuation of an Old English noun. His opinion has little to recommend it, but isn’t it amazing to find imported words for naming body parts?! Not too long ago, we wondered at leg in a similar context.

The merger of the senses “jaw” and “cheek” is of course natural, and the confusion of several similar-sounding words could be expected. In later English, we once find chaw-bone for jaw-bone! Jaws chew, and the verb chew has respectable relatives outside Germanic (for example, Russian zhevat’, stress on the second syllable). But at the moment, we are interested only in cheek and jowl.

In looking at the names of body parts, we run into all kinds of unexpected associations and often fail to find such as we expect. Not too long ago, I discussed the etymology of eye, ear, among others, and we observed how unpredictable the results turned out to be. A case in point is also English gill, the organ of respiration in fishes. It bears some resemblance to the words mentioned above. Gill turned up only in the fourteenth century, when it was borrowed from Old Norse (compare Swedish gäl and so forth). But the related Icelandic noun gjölnar means “lips,” not “gills”! The Latin for “cheek” is gena (the word very rarely occurred in the singular). If it is indeed related to Greek gōnia “angle,” then the motivation for coining this noun was that the cheeks form the sides of the face. By contrast, in English, cheek is related to choke. Such association are sometimes easy to explain but impossible to predict.

We are not always interested in chewing.

We are not always interested in chewing.(L: Photo by Mohan Nannapaneni via Pexels. R: Photo by Hana Lopez on Unsplash. Public domain)

By way of postscript, I may add that the ancient root of knee can be found in Latin genu (known to English speakers from genuflection). The common opinion is that very long ago, two different roots existed: genu-, as in Latin gena “cheek,” and genu-, as in Latin genu “knee.” Perhaps so, but knees bend, and reference to “angle” seems to underlie both “lip” as “side” and “knee” for forming an angle at bending. A look at the list of reconstructed Indo-European roots shows how many homonyms have been set up. Some of them can certainly be merged, and in the past, numerous homonyms have indeed been merged by later editors.

None of your cheek!

None of your cheek!(Photo by Sebastian Herrmann on Unsplash, public domain)

The slangy phrases none of your cheek! and none of your lip! (that is, “don’t you dare to talk back to me”), are rather baffling. The explanations one finds on the Internet do not sound too convincing, especially with regard to the first phrase. I even wonder whether cheek “insolence” and cheeky have anything to do with the side of the face. Perhaps our readers know something about this subject. Now that the summer break in the publication of “Oxford Etymologist” is over, everybody should be ready to attack the most enigmatic English words with renewed vigor.

Featured image by CC0 Community, public domain

August 30, 2022

The need for affordable and clean energy [podcast]

High gas prices. Nuclear reactors closed forever. The growth of the electric car industry. Record-breaking temperatures, and Europe’s Dependence on Russian Natural Gas. There has been no shortage in energy-related news stories this summer, and we know that they are not going to go away any time soon.

On today’s episode of The Oxford Comment, we spoke with Martin J. Pasqualetti, Professor of Geography at Arizona State University, and the author of The Thread of Energy, and Paul F. Meier, an independent clean fuels consultant and author of The Changing Energy Mix: A Systematic Comparison of Renewable and Nonrenewable Energy, on the need for affordable and clean energy (which is one of the UN’s sustainable development goals), the history of energy in the United States, and the dire implications of not changing our energy habits.

Check out Episode 75 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · The Need for Affordable and Clean Energy – Episode 75 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingTo learn more about the themes raised in this podcast, we’re pleased to share a selection of free-to-read chapters and articles:

Read the first chapter of Martin Pasqualetti’s The Thread of Energy, entitled “Discovery”.

The introduction to Paul Meier’s The Changing Energy Mix can be found here. Meier has also written numerous blog posts for the OUPblog, including “The versatility of hydrogen: storable, portable, and renewable,” “Renewable solar energy: how does it work and can it meet demand?,” and “Electric vehicles: a shift in the resource landscape for the transportation market.”

The Oxford Handbook of Energy Politics is a great resource on the energy issues relating to international relations and comparative politics. In particular, check out the chapter titled “Renewable Energy: A Technical Overview” by Kyle Bahr, Nora Szarka, and Erika Boeing.

What are the environmental consequences of natural resources and energy politics? This bibliography by Markus Kröger gathers sources relating to this topic.

Featured image: Karsten Würth, CC0 via Unsplash.

August 29, 2022

The CERN Large Hadron Collider is back

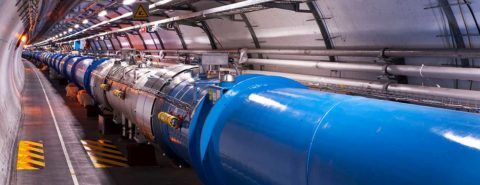

The CERN Large Hadron Collider, the LHC, is the world’s highest-energy particle accelerator. It smashes together protons with energies almost 7,000 times their intrinsic energy at rest to explore nature at distances as small as 1 part in 100,000 of the size of an atomic nucleus. These large energies and small distances hold clues to fundamental mysteries about the origin and nature of the elementary particles that make up matter.

The LHC is a high-performance machine, a Formula 1 race car, not a Toyota. As such, it needs to spend time in the shop. The previous run of the LHC ended in December 2018. Since then, scientists and technicians have installed numerous fixes and improvements to both the accelerator and the particle detectors. In mid-April, the LHC began a series of final tests and tunings, raising the collision energy from 13 TeV to 13.6 TeV, moving closer to the design energy of 14 TeV. On 5 July the new run of>Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers