Oxford University Press's Blog, page 73

July 29, 2022

Public trust in model-based science: moving beyond the “view from nowhere”

Never more than during the COVID-19 pandemic, the public has been reminded of the importance of science and the need to trust scientific advice and model-based public health policy. The delicate triangulation among scientific experts, policymakers, and the public, which is so central to fight misinformation and mistrust, has shone a light on a well-entrenched “view from nowhere” that science is often identified with. Will the public trust new vaccines produced through innovative technologies? Will the public comply with policy advice informed by scientific models? What if the models get it wrong and end up either overestimating or underestimating the number of cases in their projections? Why trust experts and their model-based policy anyway?

In recent decades, there has been a flourishing literature in philosophy of science about the nature and role of scientific models, their limits, and promises. Scientific models play a key role in public health policy, climate policy, economic forecasts, biomedical discoveries, and the search for new physics beyond the Standard Models, among many other examples. They make possible explanations, predictions, projections. Often several models are at work in delivering an outcome as with multi-model ensembles for climate projections. And very often, several seemingly incompatible models are available to study particular target systems. Why trust models then, one might ask? How can anyone ever hope to know how things really are (about the course of a pandemic, or of global warming or similar) by using models?

The problem with the public’s mistrust of model-based policy is not necessarily the modelling itself, but a certain image of model-based science intended to deliver a “view from nowhere.”

Model pluralism in science—or better, a specific variety thereof which I call perspectival modelling—is key to delivering reliable knowledge of particular phenomena. Moreover, it is the driving engine of how one comes to know the world and to open “windows on reality,” to borrow an expression from art historian Erwin Panofsky. The problem with the public’s mistrust of model-based policy is not necessarily the modelling itself, but a certain image of model-based science intended to deliver a “view from nowhere.”

Such a view usually finds its expression in the broad idea that scientific models mirror or map onto the way the world is by capturing or ascribing essential properties to the target system. Unsurprisingly, in areas of science where there is more than one model about the same target system and they seem to offer incompatible images of it, the question of “why trust models?” naturally arises.

To use a classic example from nuclear physics, one might ask “what is the atomic nucleus?” and find themselves entangled into a number of different models, whereby the atomic nucleus is described as a liquid of incompressible nuclear fluid, or as a set of shells/orbitals where nucleons sit in special (so-called “magic”) numbers, or as a bunch of quarks exchanging gluons. Which of these is the true model? And if there is only one true model, what are the others doing exactly?

Perspectivism enters the scene. Can different models be regarded as offering different perspectives on the same target system? How to make sense of this colloquial claim in a way that is neither trivial nor fraught with further inconsistencies? Models are part of wider scientific practices which are historically and culturally situated—what I call “scientific perspectives” following a tradition in philosophy of science. These wider practices do not just include particular models, but also specific experimental and technological tools and techniques available to situated epistemic communities to harvest data and use the models to make>Su San Lee on Unsplash, public domain

July 27, 2022

Returning to some of the shortest words in English

Five years ago, I discussed the origin of several very short words, the most troublesome of which were if and of (2 August and 9 August 2017). In a recent email, a correspondent asked me to return to that group, saying (quite correctly, as I think) that one can find hardly any information about its etymology on the Internet and in dictionaries. Our sources are reticent for a reason. As a rule, the origin of those verbal midgets is beyond reconstruction. As an example, take personal pronouns. She, for instance, has been the object of long and fruitful research, and some latest stages in its history have been clarified (she seems to go back to a demonstrative pronoun), but the word’s sought-for ultimate origin remains unknown. We cannot explain why once upon a time just this combination of sounds was chosen to refer to a certain class of nouns. I, he, we, you, and it fare no better. Their history has been traced, but their origin remains a puzzle, though the hypotheses on the rise of pronouns read like a thriller. The same holds for prepositions.

The family of in has been reconstructed quite well. Not only Latin in (from en) and Greek en are related to it. Even Slavic v (the same meaning) turned out to be a stub of vun. But let me repeat what I have said so many times: a list of cognates is interesting only as long as it leads to a solution. Why did people, in a huge belt of Indo-European, use a sound complex like en(i) for conveying the meaning it has? When one comes to think of it, language does not even need such a preposition. It is much easier to have a so-called locative case: add some vowel to the word and get the meaning you need. Say domi (Latin: nominative dom-us), and you will find yourself “at home,” literally, “in the house.” Compare the use of English ward (as in homeward). In a rather tasteless stylization of the character’s speech, Kipling (in the novel Kim) wrote: “My thoughts were threeward.”

It is me (it’s I).

It is me (it’s I).(By World’s Direction, via Flickr, public domain)

With conjunctions we can sometimes go a bit farther than with prepositions. For instance, Old English had the word alswā “also,” clearly a compound. Its surviving stub is Modern English as, while German has retained als “than,” going back to a related form. Than and then are two offspring of the same word. German, too, has similar forms, while Dutch dan combines both meanings. On the whole, we may say that we know a good deal about the history of our shortest words but hardly anything about their etymology (that is, origin).

Perhaps the most interesting story (as concerns conjunctions) can be told about the word and. This word looks different from Latin et “and” and Greek énti “still.” By contrast, Gothic and “toward; along; opposite” and Sanskrit anti “over against” are its obvious cognates, even though their sphere of reference is different. And, or rather its ancestor, is, unexpectedly to most, hidden in English answer, from and-swaru (swaru is of course the root of answer). Originally, answer referred to a solemn affirmation in rebutting a charge. On such legal matters see the post for 21 July 2021. Very probably, Latin ante “before” and Greek anti, known from such loanwords as English antibiotic and antidote (antediluvian, as shown by the vowel, is from Latin) are related to and. The somewhat vague spatial sense of the adverb resulted in even greater vagueness in Germanic. The German for “and” is und, the same word on a different grade of by ablaut (compare began versus begun). While reading German poems of the Middle Ages, one notices with surprise that und sometimes means “but.” Of course, if the ancient sense of the word was “over against,” why should its later cognate not mean “but”?

He and she. Totally beyond reconstruction.

He and she. Totally beyond reconstruction.(By d i e g o Authentic on Unsplash, public domain)

References to spatial relations are behind many conjunctions, and this is natural: space around us is visible and relatively easy to describe. Later, concrete senses may yield unexpected abstractions. Thus, but (which once had a long vowel) is a sum of the prefix be– and the word that has become Modern English out: from “outside” and “unless” to an adversative conjunction (“if…not”).

I remember mentioning in some other connection the fact that subordinate conjunctions are a late addition to modern languages. In the not too remote past, people were quite satisfied with joining sentences the way children do (“I went out, and I saw Bob, and he said, and I said…”). This syntax (coordination) is called parataxis. Its opposite (subordination, hypotaxis) is of the type “When I went out, I saw Bob, and, while I tried to say hello,” etc. It owes its development to the influence of bookish culture. The result is that such conjunctions are ambiguous. English as means “when” and “because,” to say nothing of its use in comparison (as good as). It goes back to al-swā “also,” with as being all that remains of that compound, even though also has (also) survived. German als “when” and “as well as” has the same history, while German also means “so; therefore; that is, etc.” Another result is that we have monstrous conjunctions like inasmuch as and notwithstanding. (Perhaps one can write an essay on the longest—and therefore useless—words in our language. The adjective valetudinarian comes to mind.)

The origin of valetudinarian, as opposed to the origin of in, is curious but obvious. We may even say that the longer the word, the more transparent its history. I have once researched the etymology of English yet and found myself in a veritable morass. For the modern form yet Old English had gīt(a), gīet(a), gȳt(a), and gēn(a), all of them obscure compounds (that much was clear). This clear obscure has been often but to no effect compared with Greek éti “still.” As a cognate, the Greek word does not fit the English one, because both have t (by the First Consonant Shift, Germanic t should correspond to non-Germanic d, as seen in English two versus Latin duo). The literature on the origin of yet is huge and hard to assemble, but once I came across a remark by Erich Berneker, a German student of Slavic and Baltic. He, at that time a man of 25 years old, compared English yet and German jetzt “now” (the latter from je zuo; t was added to the German adverb later) and traced both to the combination iu-ta, in which iu means “already” and ta is a particle having numerous secure congeners outside Germanic.

A cagey bird in the locative.

A cagey bird in the locative.(By Peter Griffin via PublicDomainPictures.net, public domain)

I’ll skip all details, partly because they are too technical and partly because there are too many of them. If professional language historians ever happen to read this blog and if they find themselves interested in the origin of yet ~ jetzt, they will discover the entire story in my 2008 book An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology. But before I finish, I will make my favorite point. The literature on the history of English, Frisian, Dutch, German, and Scandinavian words is enormous (the true word is German unübersehbar “un-over-see-able”) and someone who dares enter the field and even offer an opinion should be informed of everything that has been done in the field. Everything is a hard word. Yet (!) isn’t it shocking to find the most reasonable explanation of an English word among the remarks by a budding specialist in Slavic and Baltic! It was made in 1899 in an article whose title had nothing to do with either yet or jetzt. No wonder, even the best specialists missed it.

Such is in a nutshell the story of the etymology of our shortest words. If someone has more questions, you know where to find me.

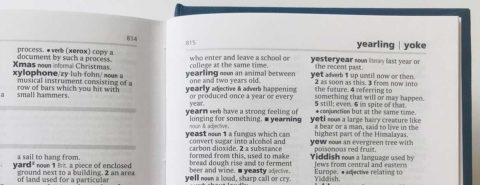

Featured image: a photo of The Little Oxford English Dictionary.

24 hours in revolutionary Paris: 9 Thermidor [timeline]

The day of 9 Thermidor in the French Republican calendar (27 July 1794) is universally acknowledged as a major turning-point in the history of the French Revolution. At midnight, Maximilien Robespierre, the most prominent member of the Committee of Public Safety, which had for more than a year directed the Reign of Terror, was planning to destroy one of the most dangerous plots that the Revolution had faced.

By midnight at the close of the day, following a day of uncertainty, surprises, upsets, and reverses, Robespierre’s world had been turned upside down. He was an outlaw, on the run, and himself wanted for conspiracy against the Republic. He felt that his whole life and his Revolutionary career were drawing to an end. As indeed they were. He shot himself shortly afterwards. Half-dead, the guillotine finished him off in grisly fashion the next day.

The Fall of Robespierre by Colin Jones provides an hour-by-hour analysis of these 24 hours. Explore each of those hours across the 24 hours of 9 Thermidor by following the white circles, then black circles, and finally the blue circle in the interactive timeline below.

July 26, 2022

Equity in health care [podcast]

There are many factors that affect our ability to be healthy and we unfortunately do not all have the same access to care. Barriers can be related to cost, discrimination, location, sexual orientation, and gender identity – to name just a few.

On today’s episode of The Oxford Comment, we complement Oxford Academic’s extensive “Health Equity” collection of journal articles, book excerpts, and online resources by speaking with two medical experts, Dr Jon Rohde, formerly of the South Africa EQUITY project, and Dr Don Dizon, Director of the Pelvic Malignancies Program at Lifespan Cancer Institute, Head of Community Outreach and Engagement at The Cancer Center at Brown University, and Director of Medical Oncology at Rhode Island Hospital. In addition to caring for patients, they have each dedicated their careers to addressing inequity in public health.

Check out Episode 74 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Equity In Health Care – Episode 74 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingTo learn more about the themes raised in this podcast, we’re pleased to share a selection of free-to-read chapters and articles:

We have curated content from OUP’s many books, journals, and online resources on equity and health care, which can be found in this “Health Equity” collection. The collection is further broken down into the categories “Social Determinants of Health” and “Physical Access.” We will be sharing a collection on Law and Policy later this summer. Follow Oxford Medicine on Facebook and Twitter for updates.

Dr Jon Rohde’s article “Ten Lessons From a Career in Global Health” Guidance to Those Considering a Life Working With the Poor Countries of the World” can be found in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health.

Dr Don Dizon has written numerous blog posts for The Oncologist, including “Cancer Care an Ocean Away: Support and Engagement all the same”, “When a Pandemic Hits Your Homeland”, “Home is Where the Heart Is”, and “Caring for Transgender Patients with Cancer.”

Lastly, we recommend these two Open Access articles, “The Health Inequalities Assessment Toolkit: supporting integration of equity into applied health research“ from the Journal of Public Health and “Trends in the Incidence of Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers by County-Level Income and Smoking Prevalence in the United States, 2000-2018“ from JNCI Cancer Spectrum, as well as the chapter “Needs of child refugees and economic factors“ from the Oxford Textbook of Migrant Psychiatry.”

Featured image: Oluwaseyi Johnson, CC0 via Unsplash.

July 25, 2022

Cut out characters and cracky plots: Jacob’s Room as Shakespeare play

In April 1919, Virginia Woolf (née Stephen) published “Modern Novels” in the TLS, the first of her series of essays taking issue with Arnold Bennett, John Galsworthy, and H. G. Wells, whom she termed “materialists.” In Woolf’s view, these contemporary novelists, Bennett in particular, described villas and carriages when they should describe the “myriad impressions” a mind receives daily; they gave the spaces in which life happens when they should give life itself, by way of psychology. It is therefore striking that Woolf’s first experimental novel, Jacob’s Room, published in 1922, should so determinedly avoid the inner life. In light of Woolf’s quarrel with the materialists, the book’s title reads almost as a joke, a reductio ad absurdum of Bennett’s error, implying I won’t even pretend to give you a character; here is yet another dwelling. The form of the novel exists to create character, Woolf asserts in many essays throughout her life. And she is well-known for revealing characters by “tunneling” (her word) into their thoughts. But this innovation did not come until her next book, Mrs. Dalloway (1925). Jacob’s Room is its inversion, its shadow, an exploration of what the novel can be when centred on someone unknowable.

The novel traces the life of Jacob Flanders from age six, when he captures a crab on a Cornish beach, to 26, when he is absent from his room in the midst of World War I. But “trace” is not the right word; it is more like a “connect-the-dots” pattern that invites the tracing line. Each dot is a scene from the life of Jacob or those around him. These vignettes are laid next to each other like paint swatches or slabs of different rocks. (It is a book whose structure provokes simile.) Nothing is told directly, and we are never in Jacob’s mind. We get Jacob’s words only when he shares them with someone else—in conversation, in correspondence—and they are fragments: a curse, a brief quotation, the start of a joke, the end of an argument. We see Jacob through the eyes of others: his mother, the man and the several women who are in love with him, and the mercurial narrator—female, ten years older (so she tells us on p. 98), by turns a distant observer and a stalker, veering between diffidence and confidence in her self-appointed task. Others’ love for Jacob, not Jacob himself, warms us to him.The narrator’s quest is our own; with this tender, sardonic, voyeuristic woman we keep pursuing Jacob, as though we expect a revelation. The narrator describes the feeling: “something is always impelling one to hum vibrating, like the hawk moth, at the mouth of the cavern of mystery, endowing Jacob Flanders with all sorts of qualities he had not at all [ . . . ] what remains is mostly a matter of guess work. Yet over him we hang vibrating” (74). At the novel’s end, as Jacob’s mother and his friend Bonamy stand in his room, guess work is indeed what remains. Bonamy wonders, “What did he expect? Did he think he would come back?” And Jacob’s mother, holding out her son’s shoes, asks, “What am I to do with these, Mr. Bonamy?” (186-7). Jacob escapes them, and us, but he does not escape the fate his surname had foretold.

The motives for mysteryWhy, within the world of the novel, is Jacob unknowable? Partly because he is a type: the young man with a confident grasp of English and Classical literature, ready to assume his place among the English institutions for which he has been prepared by his Cambridge education. Were he allowed to grow old, his individuality would grow more pronounced. The fact that he is a type allows him to stand for many besides himself. That we can never know him better indicts the system that sent hundreds of thousands of young men to their deaths. Further, the stymied effort to know Jacob casts doubt on all that seemed, before the war, known or knowable. Jacob is also impenetrable because, to some extent, everyone is, even the old. And he is a cipher, finally, because a person does not exist in isolation; others compose us, as the narrator suggests (“part of this is not Jacob but Richard Bonamy,” 73).

But there is another reason, a reason outside of the novel, that Jacob is unknowable. He is the hero of a Shakespeare play.

On 5 November 1901, Virginia Stephen writes a letter to her older brother Thoby, studying at Cambridge, about her new reverence for Shakespeare. I transcribe her writing exactly, here and later.

I have been reading Marlow, and I was so much more impressed by him than I thought I should be, that I read Cymbeline just to see if there mightnt be more in the great William than I supposed. And I was quite upset! Really and truly I am now let in to [the] company of worshippers—though I still feel a little oppresed by his—greatness I suppose. I shall want a lecture when I see you; to clear up some points about the Plays. I mean about the characters. Why aren’t they more human? Imogen and Posthumous and Cymbeline—I find them beyond me—Is this my feminine weakness in the upper region? But really they might have been cut out with a pair of scissors—as far as mere humanity goes—Of course they talk divinely. I have spotted the best lines in the play—almost in any play I should think—

Imogen says—Think that you are upon a rock, and now throw me again! and Posthumous answers—Hang there like fruit, my Soul, till the tree die [Cymbeline V.v.262-5]. Now if that doesn’t send a shiver down your spine, even if you are in the middle of cold grouse and coffee—you are no true Shakespearian! [ . . . . ] Of course Shakespeares smaller characters are human; what I say is that superhuman ones are superhuman. Just explain this to me—and also why his plots are just cracky things [ . . . .] (L1, 45-46)

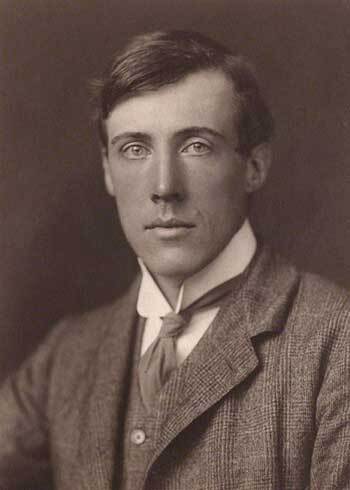

Portrait of Thoby Stephen by the British photographer George Charles Beresford (1864-1938). 1902-1906.

Portrait of Thoby Stephen by the British photographer George Charles Beresford (1864-1938). 1902-1906.(Courtesy of the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. Crown Copyright expired. Via Wikimedia Commons.)

In Jacob’s Room, Woolf gives some of this language to an English painter whom Jacob befriends in Paris, Cruttendon. “I’ll tell you the three greatest things that were ever writen in the whole of literature,” Cruttendon says, and offers the first: “‘Hang there like fruit my soul’”. Jacob replies, “I’m with you there,” and declaims the line dramatically. He then says the line at the same time as Cruttendon, which sets them laughing (132). In Cymbeline, the exchange Virginia Stephen quotes marks the lovers’ reunion: Posthumus had thought Imogen dead, but here she revives from what was only a temporary sleep. When Imogen says “Throw me again,” her stage direction reads, “[Embracing him.]”

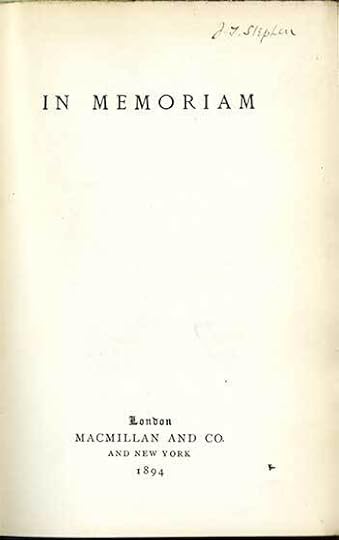

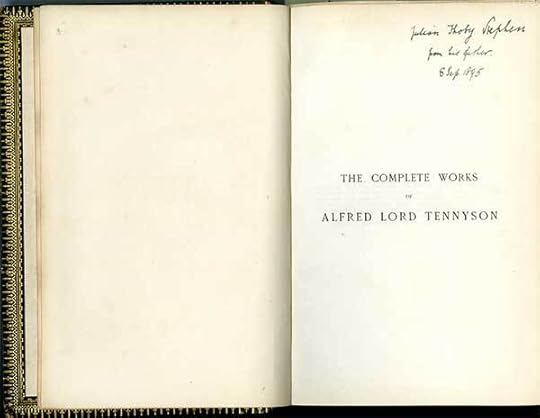

Thoby Stephen’s other worldAs is well known, Woolf’s private model for Jacob was Thoby (born Julian Thoby), who died at 26 from typhoid contracted on a trip they took to Greece in the fall of 1906. Like Jacob, Thoby played on the beach of St. Ives as a child, attended Cambridge, and was given to bold declarations. Like Jacob, Thoby had close male friends, romantic entanglements with women, a lanky and handsome figure, and a certain reserve and gloominess. Jacob’s literary taste is Thoby’s: both admire Homer, Virgil, Lucretius, Aristophanes, Marlowe, Donne, Fielding, Shelley, Tennyson—and Shakespeare above all.

Title page of In Memoriam, by Alfred Lord Tennyson (London: Macmillan, 1894). Signed “J. T. Stephen.”

Title page of In Memoriam, by Alfred Lord Tennyson (London: Macmillan, 1894). Signed “J. T. Stephen.” (Library of Leonard and Virginia Woolf, Washington State University, Holland-Terrell Libraries, Manuscripts and Special Collections, PR5562.A1 1894.)

Half-title page of The Works of Alfred Lord Tennyson, Poet Laureate (London: Macmillan, 1894). Inscribed “Julian Thoby Stephen / from his father. / 8 Sep. 1895.”

Half-title page of The Works of Alfred Lord Tennyson, Poet Laureate (London: Macmillan, 1894). Inscribed “Julian Thoby Stephen / from his father. / 8 Sep. 1895.” (Library of Leonard and Virginia Woolf, Washington State University, Holland-Terrell Libraries, Manuscripts and Special Collections, PR5550.E94.)

Jacob plans to read a Shakespeare play while sailing to the Scilly Isles, but his ambition is thwarted: he takes a brief swim, and, on his return to ship, accidentally knocks Shakespeare overboard (46-47). The reader and his book are twinned—both plunge into the sea—and the loss of one prefigures the loss of the other. For Woolf, Thoby and Shakespeare were likewise twinned. Late in her life she wrote of her brother, “Shakespeare was to him his other world; the place where he got the measure of the daily world” (“A Sketch of the Past,” 138-9). After her brother’s death, Woolf looked to Shakespeare as if to Thoby, as when she conjured up Judith Shakespeare, William’s younger sister with a “genius . . . for fiction,” in A Room of One’s Own (1929). Voicing her youthful judgment of Shakespeare through Cruttendon, Woolf revives not only Imogen, but also Thoby. She continues her conversation with her lost brother; she is again “embracing him.” And he says, “I’m with you there.”

I wrote in my book Virginia Woolf and Poetry of Virginia Stephen’s letter to Thoby that inspired the exchange with Cruttendon, and I’ve written elsewhere about Woolf’s growing identification with Shakespeare in the late 1920s. I would now add that the whole of Jacob’s Room might be seen as a Shakespeare play; the novel matches Virginia Stephen’s bardolatrous criticism almost point by point. Jacob’s Room shows, along with the 1917 short story “The Mark on the Wall” and the 1920 public letter “The Intellectual Status of Women,” that Woolf already takes Shakespeare as a model.

“Why aren’t they more human?” Virginia Stephen asks her brother of Shakespeare’s characters. “Why isn’t he more human?” readers of Jacob’s Room have wondered. Jacob is a peripatetic silhouette, as though “cut out with a pair of scissors.” He is “superhuman” in the sense that he is a generic hero, a compelling example (though he does not “talk divinely”), exceeding individuality and our understanding. Like Imogen and Posthumus, in Virginia Stephen’s estimation, he does not seem fully real. But the “smaller characters are human,” such as Betty Flanders, Jacob’s mother, and Clara Durrant, a thoughtful young woman in love with him. As in Shakespeare, the minor characters are sometimes the stars of a scene that lacks the hero, and, as in Shakespeare, there are so many minor characters. Woolf wrote, a decade or so later, that she relished Shakespeare’s “crowd of minor lesser people” (manuscript draft of “A Letter to a Young Poet,” qtd. p. 235 in Virginia Woolf and Poetry). And the plot of Jacob’s Room, as Virginia Stephen wrote of Shakespeare’s plays, is certainly “cracky.”

“Poor Jacob,” Clara’s mother observes at a social gathering, “They’re going to make you act in their play” (62). “They” is the young ladies who have been making costumes. More remotely, it is the political leaders who will later cast Jacob as a soldier in the war. The line’s Shakespearean undertones—“All the world’s a stage, / and all the men and women merely players”—sound lounder when we have in mind Virginia Stephen’s 1901 letter. Indeed, the “seven ages” detailed in As You Like It by Jaques (II.vii.139-66) chart the life, or would-be life, of Thoby Stephen and “judicial” Jacob Flanders (132): “the infant,” “the whining schoolboy,” “the lover,” “a soldier,” “the justice [who] plays his part,” “shrunk” old age, and “second childishness.” Blending this speech and Fortinbras’s on the death of Hamlet (Hamlet V.ii.397-8), Woolf would write of Thoby, “I felt he scented the battle; was already, in anticipation, a law maker; proud of his station as a man; ready to play his part among men. Had he been put on, he would have proved most royally” (“A Sketch of the Past,” 139).

Woolf rereads her letters to ThobyA favorite theme of the narrator of Jacob’s Room is the need and failure of letters. They consume tremendous time and often do not last; they clutch at intimacy and misrepresent reality. And yet, “These are our stays and props. These lace our days together and make of life a perfect globe” (96). The world is a stage and letters our props, Jacob’s Room as though acted in Shakespeare’s Globe. The exchange with Cruttendon is not reported in Jacob’s letters to his mother. Of his friendship, perhaps romantic, with Cruttendon and Cruttendon’s friend Jinny Carslake, the narrator avows, “No—Mrs. Flanders was told none of this” (137). But what Jacob does not write to his mother, Virginia Stephen wrote to Thoby. Echoing her 1901 letter makes public, and permanent, what the siblings shared in private.

Clearly Woolf reread her correspondence to Thoby as she wrote Jacob’s Room. The word “room” recurs in these letters, since she imagines Thoby’s Trinity apartment or mentions his empty bedroom at their family home. She asks, for instance, “did [you] say really that you wanted a kitten for your rooms” (L1 45, [Oct.? 1901]).” And a letter of July 1901 begins, “Your Bill was not in your room [but I found it] on the writing table in the drawing room” (L1 42). At the end of Jacob’s Room, Bonamy is “standing in the middle of Jacob’s room.” He exclaims, “All his letters strewn about for any one to read,” and then: “Bonamy took up a bill for a hunting-crop. ‘That seems to be paid,’ he said” (186). Again Woolf becomes a friend of Jacob’s. When Thoby was alive, she searched his room for bills; after his death, she sets his affairs in order, including by preserving his letters. And although the stories letters tell may be trivial, partial, or distorted, of such stories a more significant, replete, and honest one can be made.

In January 1903, for her 21st birthday, Virginia Stephen asks Thoby if he could “ask David [a bookseller] to try and get a Hollinshead, not black letters, for me some time?” (L1 67, [25? Jan. 1903]. Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles, first published in 1557, was the major source for many of Shakespeare’s plays. Puzzled by Shakespeare’s “cut out” characters and “cracky” plots, Virginia Stephen pursued a historical source for the work. If we are puzzled by Jacob’s Room, we are helped by pursuing an epistolary one.

Works citedshow moreShakespeare, William. The Riverside Shakespeare: The Complete Works. Gen. Eds. G. Blakemore Evans and J. J. M. Tobin. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997.Woolf, Virginia. The Letters of Virginia Woolf, Volume 1: 1888-1912. Edited by Nigel Nicolson and Joanne Trautmann. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975. Abbreviated L1.Woolf, Virginia. “The Intellectual Status of Women.” 1920. In The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume 2: 1920-1924. Edited by Anne Olivier Bell, assisted by Andrew McNeillie. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978. Appendix III: 339–42.Woolf, Virginia. Jacob’s Room. 1922. Annotated with an introduction by Vara Neverow. Gen. Ed. Mark Hussey. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, 2008.Woolf, Virginia. “A Letter to a Young Poet.” MS draft. Accession # MA 3333. The Morgan Library & Museum, Dept. of Literary and Historical Manuscripts, New York.Woolf, Virginia. “The Mark on the Wall.” 1917. In The Complete Shorter Fiction of Virginia Woolf. Edited by Susan Dick. 2nd edn. San Diego, CA: Harcourt, 1989. 83–89.Woolf, Virginia. “Modern Novels.” 1919. In The Essays of Virginia Woolf, Volume 3: 1919-1924. Edited by Andrew McNeillie. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1988. 30–37.Woolf, Virginia. “A Sketch of the Past.” In Moments of Being: A Collection of Autobiographical Writing. Edited by Jeanne Schulkind. 2nd edn. San Diego, CA: Harcourt, 1985. 61–159. Composed 1939–40.show less

July 24, 2022

Birth: when was Shakespeare’s birthday?

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.When was Shakespeare’s birthday?

In this OUPblog series, Lena Cowen Orlin, author of the “detailed and dazzling” The Private Life of William Shakespeare, explores key moments in the Bard’s life. From asking just when was Shakespeare’s birthday, to his bequest of a “second-best bed,” to his own funerary monument, you can read the complete series here.When was Shakespeare’s birthday?Shakespeare made his first entrance into history on 26 April 1564, the day he was christened in the parish church of Stratford-upon-Avon. Most of us want to know the birthdate, not the baptism, but unfortunately our only clue to the birthdate is the baptism. By the middle of the eighteenth century, consensus had begun to form around a 23 April nativity. Later biographers were bent on proving the theory to be true.

In 1848, James Orchard Halliwell Phillips observed that the Tudor astrologer John Dee had four children, two of them baptised three days after birth. “Three days was often the period which elapsed between birth and baptism,” Halliwell Phillipps declared. Those who came after him called the three-day interval “common practice.” In 1904, Charles Isaac Elton advised that “we should go by the rule in the Prayer-book.” According to the authorized Book of Common Prayer, baptism “should not be ministered but upon Sundays and other holy days.” Since Shakespeare was not baptized on 23 April, which was a Sunday in 1564, it follows that he cannot have been born before 23 April. Elton disposed of the inconvenient fact that the next holy day after 23 April was 25 April, dedicated to St Mark, by suggesting that the christening would have been delayed until 26 April because St Mark’s Day was known to be unlucky, “prolific in superstitions.” For more than a century now, Elton’s “rules” have been repeated in Shakespeare biographies.

Learned as they appear, however, these pieces of “evidence” are not really evidentiary. What John Dee’s family did two times out of four cannot be said to be statistically significant. With a record base constituted almost exclusively of baptisms and few known birthdates to correlate them to, it is impossible to demonstrate larger patterns. Meanwhile, if we reconstitute the calendar for 1564 and return to the Stratford parish register, we find that the 1559 Book of Common Prayer was more honoured in the breach than the observance. Of 48 baptisms in 1564, just nine occurred on Sundays and five on other holy days. In 1561, the infant Mary Beard was taken to the Stratford baptismal font on a supposedly inauspicious 25 April. At least seven additional St Mark’s Day christenings would be performed before the turn of the century.

How is it that the Book of Common Prayer had inspired biographers to abandon common sense? Since they already knew that 23 April was a Sunday in 1564, they should also have known that 26 April was not a Sunday. Nor was 26 April celebrated as a feast day on the English calendar. Authorized restrictions to “Sundays and other holy days” had no bearing on Shakespeare’s baptism.

The prayer book favoured days when “the most number of people may come together.” Holy-day christenings “testify the receiving of them that be newly baptized into the number of Christ’s church,” and “in the baptism of infants every man present may be put in remembrance of his own profession made to God in his baptism.” In other words, sanctioned practice was about the godly community more than the spiritual or physical health of the individual child. We should not be surprised that many families went their own ways. Shakespeare’s parents, for example, had already lost at least one daughter by 1564, if not two, and they may have hastened to christen their son immediately for fear of repeated infant mortality. Equally, however, they may have decided to delay till midweek in order to avoid a Sabbath assembly that, as with any crowd, would have seemed to increase their newborn’s risk of exposure to contagious disease. Or they may have chosen a sacramentally inconsequential Wednesday for no other reason than that they would be busy on Thursday, which was market day in Stratford. Gloves and other leather goods, which the Shakespeares produced, were among the town’s leading market products.

Why were Halliwell-Phillips, Elton, and their followers so eager to drive the evidence to that 23 April birthdate? For two reasons. First, according to his funerary monument, Shakespeare died on 23 April—a marvellous symmetry. Second, 23 April was the feast day of England’s patron saint, St George—a marvellous portent. The eighteenth-century editor and biographer Edmond Malone had deemed it “a happy presage, as it should seem, that his name and reputation should for ever be united with that of England.” Others would conclude that there was a divinity that shaped Shakespeare’s beginnings.

By now, we have all agreed to celebrate his birthday on 23 April. This is probably a necessary convenience. But the only thing we can know from available evidence is that Shakespeare was born on or before 26 April 1564.

Featured image: A booke of Christian prayers … Day, Richard, b. 1552. FSL collection (CC BY-SA 4.0).

July 22, 2022

How well do you know Mary Shelley? [Quiz]

Mary Shelley was an English writer born in 1797. She is best known for her novel Frankenstein. But there’s much more to Shelley’s life than meets the eye.

How well do you know Mary Shelley? Take this short quiz to find out and put your knowledge to the test. Good luck!

Featured image: by Sofia Ivarinen from Pixabay, public domain

Quiz cover image: Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley by Richard Rothwell (National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

July 20, 2022

Pulling the whole length of one’s leg

Our most recent discussion, two weeks ago, concerned the word toe. I would like to go all the way up to the hip and show that the entire area is (at best) a mildly promising etymological morass. We’ll begin with the title of this post. Today, most English speakers will recognize the idiom: to pull one’s leg means “to deceive playfully, to tease.” Though the phrase looks old, no pre-1821 record of it has been found. Some people apparently knew it in India in the 1850s, but in England, even in 1913, the correspondents to Notes and Queries believed that this somewhat impolite idiom was recent. Its origin has not been discovered.

In my forthcoming dictionary of English idioms, I usually stay away from guesswork, but in a blog, vague conjectures may not do anyone any harm. As we know, in Victorian England, the word leg was unpronounceable, so much so that one avoided mentioning even the legs of a piano: limb was the genteel substitute for it. Leg, so indecent, so vulgar! We don’t always recognize the true meaning of the popular tales dealing with this limb. Cinderella was discovered in her obscurity, because her foot matched the shoe. Well, the foot is part of the leg, isn’t it? Naturally, the prince was interested in his prospective wife’s legs. Likewise, Skathi, one of the giantesses of Old Norse mythology, was allowed to choose a husband among the gods, but they stipulated that she might see them only below the waist—again a wise provision for a bridal quest. She admired a pair of beautiful legs but made an almost fatal mistake: the legs belonged to a god who turned out to be a wrong match for her. This is an old myth, but it sounds like an echo of a humorous or aetiological folk tale, the more so as the two later separated, an unusual situation in folklore (the newlyweds are supposed to live happily ever after).

The fact that the idiom was known in India may suggest that it is a facetious rephrasing of some sentence in Hindi, as probably happened to that’s the cheese (see the post for 24 December 2014), even though, to repeat, it occurred as early as 1821 in a text by a British author. Another, more probable, scenario is that pull one’s leg began its life as slang or even thieves’ cant. If so, our chances of discovering the origin of the phrase are vanishingly small.

Pulling his leg.

Pulling his leg.(Photo by Carine06 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Now back to etymology. We’ll begin with the word leg itself. It is almost unbelievable that such an important word is a borrowing. Yet it is a loan from Scandinavian. The Old English word for “leg” was sceanca, still known in the form shank, which today denotes only the part from the knee to the ankle. This noun is also preserved in such family names as Cruikshank. German Schenkel “thin bone” is related. Apparently, the word’s root meant “distorted, lame,” as opposed to the root of shin, which may have meant “a straight stick” or something like it and be ultimately related to a verb for cutting. Shindy, earlier shinty “spree, great commotion” and “a game resembling hockey” seems to go back to the cries used in the games “shin ye, shin t’ye.” Amusingly, German Schinken “ham” has the same root, but English ham also means “bend of the knee” (hence hamstring “tendon at the back of the knee”; when it is cut, one is hamstrung), “thigh of a hog used for food,” and the universally known food word ham. (The origin of German Bein “leg,” related to English bone, is shrouded in almost impenetrable mystery.)

George Cruikshank (1792-1878), the world-famous illustrator of Dickens’s novels.

George Cruikshank (1792-1878), the world-famous illustrator of Dickens’s novels.(National Portrait Gallery collection, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.)

The previous exposition mentioned thigh and leg. Though leg is of obscure origin,it is certainly related to the Scandinavian word for “thigh.” All the rest is doubtful, and equally doubtful is the origin of thigh (perhaps the word referred to the “thick” part of the extremity). The uncertainty attending the etymology of all such words need not surprise us: the division of the body into separate parts is to a certain extent arbitrary, as shown by the worn to death reference to the fact that not all languages recognize the difference between “arm/hand” and “leg/foot” (see the old posts on breast, bosom, etc. for 13 April, 20 April 2016). It is also characteristic that none of the words discussed briefly above (leg, shank, thigh, shin) has direct cognates outside Germanic and sometimes even outside West Germanic. The same holds for body (compare it with Latin corpus! German did borrow the Latin word; hence Körper; with regard to body see the post for 14 October 2015). If you look up the old discussion of eye and ear in this blog, you will realize that both words, even though they are not confined to Germanic, have a history full of unexplained details. All over the place, we are dealing with individual coinages. Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin words for “leg” and the rest are quite different.

The lower extremity is “a bodily organ of support and locomotion” or “a limb of an animal used especially for supporting the body and for walking.” Such are the admirable definitions of leg in our dictionaries, and, apparently, leg might be named for any of those characteristics or metaphorically (a stick, a column, a support, something straight, and so forth). Associations and transfers of names in this sphere are often unpredictable and puzzling. For example, the Slavic word for “leg” (and “foot”—one word for both! Russian noga, etc.) is related to English nail and German Nagel. The reference must have been to an object resembling a claw or a talon, and, if so, at one time, the word referred only to the foot. Such a change of focus is possible. For instance, the Slavic word for “finger” originally seems to have designated the toe.

This is a leg of mutton sleeve, and this is a real leg of mutton.

This is a leg of mutton sleeve, and this is a real leg of mutton.(L: by David Ring, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain; R: by Jan in Bergen, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Occasionally, as long as we remain in the shelter of the leg, some cognates outside Germanic do show up. For example, ankle (with its typical diminutive suffix l) has a related form in Sanskrit. Latin angulus “angle” may belong here too. By the way, English ankle is also a borrowing from Scandinavian, though a similar native noun (a compound) existed; its second syllable resembled the word for “claw.” English seems to stand rather firmly on Scandinavian legs. But of course, the greatest (and the only!) example of Indo-European connections in this area is foot. We expect that non-Germanic forms will begin with p (as in father ~ pater) by the First Consonant Shift, and so they do. Here, related forms are all over the place: Latin pes, pedis (as in pedal, pedestrian, pedicure, pedigree, and others), Greek poús (the root is pod-; hence podagra “gout” and podiatrist), as well as numerous related forms elsewhere. Old English also had fæt “step,” still discernible in fetters and fetlock. If the ancient root was pod-, it must have been sound-imitative. One walked pod-pod-pod five thousand years ago, just as we walk pad-pad-pad. English path seems to be close by. Is hip connected with the verb hop? Some people think so, but who has seen people hopping on hips?

Journalists like to finish their pieces with a pun. Do you think that the etymology, with its constant prevarication and verdicts “origin unknown/uncertain/doubtful,” has no leg to stand on? If so, relent. A good deal has been discovered, and the fact that few conclusions are final only shows that etymology is a serious branch of scholarship, rather than legerdemain, that is, a sleight of hands, but hand is a special subject.

Featured image by Lucrezia Carnelos on Unsplash

July 18, 2022

A summer playlist inspired by Oxford World’s Classics

Well, as George Gershwin penned it, it is “summertime and the livin’ is easy.”

… If not easy, at least the sun is shining brighter! Our summer wish for you is to stay cool, whether it be lounging by a refreshingly blue pool, the sun-kissed ocean, or a tiny blow-up pool in your backyard. Make sure to apply a thick layer of sunscreen and, of course, have a good book in hand and tunes blasting through your speakers!

To help curate your summer playlist and reading list, here are 10 songs and Oxford World’s Classics we recommend you add to your rotation:

Based on the 1847 gothic tragedy Wuthering Heights written by Emily Brontë, “Wuthering Heights” by Kate Bush is sung from the perspective of the ghost of Catherine Earnshow, or “Cathy” as self-referenced to in the song.

As in the song, the book centers around the story of Catherine and Heathcliff who share an unrequited love, where Cathy is longing for Heathcliff to let her in, alluding to something more than physical. The ghostly tone of voice and dream-like melody is sure to put you in the book’s setting of Wuthering Heights.

Read: Wuthering Heights

2. “Love Story” by Taylor Swift and Romeo and Juliet by Shakespeare

Just what is it about unrequited love? Swifties (a moniker for Taylor Swift fans) will immediately know which classic story this song is referencing, but Taylor Swift doesn’t leave the rest of us guessing for long. In the second verse, Swift introduces two familiar names—Romeo and Juliet. The song is sung from the perspective of Juliet, but unlike the tragic ending for Juliet in Shakespeare’s 16th-century play, Romeo and Juliet, Swift’s Juliet has a happy ending to her love story.

Read: Romeo and Juliet

3. “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” by Elton John and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

One of Elton John’s greatest hits borrows its title from the yellow brick road, a fictional element in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, published in 1900. In the book, the yellow brick road leads the protagonist Dorothy, her dog, and friends from Oz to meet the Wizard of Oz.

In the song, the yellow brick road symbolizes a path to fame and riches, but the young boy whom John sings about would rather bid adieu to the road and go back home to his farm. Although the song and book follow different storylines, the yellow brick road serves as an important element to finding one’s way home.

Read: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

4. “The Man in the Iron Mask” by Billy Bragg and The Man in the Iron Mask by Alexandre Dumas

Based on the story of a prisoner of state who went by the pseudonym, “Eustache Dauger,” The Man in the Iron Mask has been a prominent figure in many works of art. Most famously, he was featured in Alexandre Dumas’ novel from the late 1840s. There are many theories, rumours, and legends surrounding the man in the iron mask, and Dumas made this real life individual into a mysterious sensation when he was featured in a section of his novel, The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later, the final installment of his D’Artagnan saga. In the book, the man in the iron mask is depicted as Louis XIV’s identical twin, whereas the song takes a less literal approach where the narrator uses the metaphorical “iron mask” to hide their true feelings.

Read: The Man in the Iron Mask

5. “Portrait of a Man” by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

Published in 1891, The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde was his only novel, and one that garnered much controversy during his lifetime, but is now revered as a gothic classic. The story of Dorian Gray is about youth and beauty as Gray does not want any of his woes, pain, sin nor suffering to be reflected on his face, so Gray expresses a desire to sell his soul via a portrait of himself. As the story progresses, Gray witnesses the portrait growing old and decaying with every year that passes and every sin he commits. The song takes on a meditative and self-reflective route where the narrator talks about a portrait that he is painting, and that the portrait is of himself.

Read: The Picture of Dorian Gray

6. “Love Song for a Vampire” by Annie Lennox and Dracula by Bram Stoker

Dracula is an epistolary novel written by Bram Stoker published in 1897. The story centers around Count Dracula’s move from his hometown of Transylvania to the English seaside as he searches for victims, and the actions of Professor Abraham Van Helsing and his cohort who are on the hunt for the Count.

“Love Song for a Vampire” by Annie Lennox was the theme song for the 1992 movie “Bram Stoker’s Dracula.” Lennox said that her inspiration was to dive deeper into the vampire trope in a psychic and psychological manner, and to incorporate this dark essence into the song.

Read: Dracula

7. “Ophelia” by The Lumineers and Hamlet by William Shakespeare

Ophelia is, by now, a house-hold name, and one that is frequently associated with one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies, Hamlet. Although Ophelia is not the titular character of the story, she is one of the most memorable, and arguably endured the most tragedy out of all involved.

In the song by The Lumineers, Ophelia is a metaphor for fame; how fame can love someone intensely, but how it will always move on.

Read: Hamlet

8. “Moby Dick” by Gurr and Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

The story of Moby-Dick is regarded as a “Great American Novel” as it seemingly adjusts its perspective according to the reader. Written in 1851 by Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, or, The Whale, is a sailor’s narrative of the captain of a whaling ship’s quest for revenge against Moby Dick, a white sperm whale. The song by Gurr under the same name is a catchy, fun, yet moody musical rendition of the story, seemingly from the perspective of someone who is watching the darkness of the sea unfold from the shore.

Read: Moby-Dick

9. “Over at the Frankenstein Place” from “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” and Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

Infused with both the Gothic and Romantic movements, Frankenstein is a novel written in 1818 by Mary Shelley. It tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who brings to life a man-made creature, a monster who develops to be sensitive and emotional, and seemingly only has one goal: to share his life with another sentient being. The song “Over at the Frankenstein Place” is from the 1975 cult musical, “Rocky Horror Picture Show,” where Dr Frank N. Furter also brings to life a sentient being.

Read: Frankenstein

10. “Virginia Woolf” by Indigo Girls and A Room of One’s Own by Virginia WoolfA Room of One’s Own is a long-form essay by Virginia Woolf that was first published in 1929. The essay uses many metaphors to illustrate and explore social injustices, especially about the lack of freedom of expression for women. She famously wrote, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction”—Woolf’s most essential point in the essay. The song by Indigo Girls titled “Virginia Woolf” alludes to many key moments in the author’s life from A Room of One’s Own, to Woolf’s abusive family, and to her ultimate demise.

Discover: Virginia Woolf

Listen to our Oxford World’s Classics-inspired playlist on Spotify →

Featured image by Joyce McCown. Public domain via Unsplash.

July 11, 2022

Were you prepared for this pandemic?

Did you have a stock of fitted, unexpired N95 masks in your closet and a six-month supply of non-perishable foods in the pantry? Pretty much nobody was fully prepared, including me. Were you relying on the healthcare system to keep supplies on hand? In this case, the healthcare system was itself rapidly overwhelmed and close to collapse. Should we expect better preparedness from ourselves and our society?

“Way back” in 2003/4, with the SARS outbreak in Toronto, we were also surprised. We were not at all fully prepared for an outbreak of these proportions. Justice Archie Campbell, in his investigation of this, pointed out deficiencies in the system. These were not recommendations for treatment of patients. He made specific recommendations regarding systemic improvement. These improvements were only partially implemented, and the COVID-19 pandemic was as much a surprise in Ontario as it was elsewhere. His most important recommendation/suggestion/warning was that the precautionary principle was needed in future, in that “reasonable efforts to reduce risk need not await scientific proof.”

It may be that an expectation of full coordination, cooperation, communication, and logistical nimbleness is too much to ask of healthcare, public health, and societal systems that are not as much of an organized “system” as is believed. So, let’s leave that out of the discussion for now, and focus on the precautionary principle as the most important element of preparedness, as Campbell suggested.

In 2003 in Toronto, we were initially advised to take full airborne precautions; we wore N95 masks, with gowns and gloves. Why? Because the organism and the disease were totally unknown, and public health was taking few chances. What of the precautionary principle 19 years later? An article in Nature in April 2022 by D. Lewis pointed out several reasons why it took the World Health Organization (WHO) two years to declare that COVID-19 is airborne. A number of these reasons invoked a failure to use the precautionary principle. This required significant disregard for the WHO’s own documents and recommendations from two decades earlier. Ministers of both Health and Environment, for the Member States in the WHO European Region “way back” in 2004 declared: “We reaffirm the importance of the precautionary principle as a risk management tool, and we therefore recommend that it should be applied”. As well, another WHO publication from 2004 dealing entirely with the precautionary principle stated that, “If used intelligently, imaginatively and daringly, the precautionary principle will support efforts to strive towards a healthier and safer world”.

“At its simplest, the precautionary principle means that when there is serious risk, one should not wait for scientific confirmation before taking action.”

The precautionary principle had its origins in environmental protections in the 1970s. Although there is no universal definition, at its simplest, the precautionary principle means that when there is serious risk, one should not wait for scientific confirmation before taking action. There is a mistaken impression that the precautionary principle calls for jumping from the frying pan without scientific evidence of the characteristics of the fire. One may take action without waiting for scientific confirmation of the size of the fire, the number of BTUs produced, and the radius of the fire ring, if the frying pan is getting hot. Without full knowledge, there is indeed a risk of landing in the fire. However, if there is an estimate of the fire, then jumping may be a much safer alternative than waiting in the frying pan. The truth is that the precautionary principle is a clarion call for scientific evidence, as noted by Dr Martuzzi: “Thus, precaution requires more and better science.”

It seems reasonable to make preparations for catastrophe, if there is some evidence of impending catastrophe, even if the precise nature and extent of the catastrophe is not yet fully delineated. Should it turn out that there was no catastrophe, or that the risk was not great, “minimizers” look brilliant, having predicted the outcome correctly. As bets go, that would be a good bet—catastrophes are rare. In the process, they manage to fully protect the comfort of many people by minimizing danger and worry. More importantly, they also fully protect their budgets. A Forbes article in 2020, called the precautionary principle “Anti-Science” on the basis that it held up developments of medical advances whose releases were postponed, awaiting more scientific proof. This article, or its ilk, are worth consideration, but I do not agree that it is cause to outright reject the precautionary principle.

Should, in the end, there be no catastrophe, those who issued warnings using the precautionary principle will be assailed on the basis of having disturbed both comfort and budgets. On the other hand, should it turn out that the catastrophe was inevitable, those who used the precautionary principle do look very good. Regarding COVID-19, in January 2020, I said to my hospital staff “here we go again—maybe—take care.” A year later, the nurses were asking, “how did you know?” I knew because of my experience in Toronto in 2003/4. The accurate prediction of the possibility brought me no joy. I didn’t know the precise risk, but I knew there was a risk, and I thought information using the precautionary principle was important to communicate.

Why does the precautionary principle apply to pandemics? Because the downside of refusing to apply the precautionary principle to pandemics is dire. We have not yet left the current COVID-19 pandemic behind us, but it is a certainty that the next pandemic is coming. We don’t know where or when, but it is coming. Are you prepared? Are we all prepared? Are we prepared to face the costs of being prepared?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers