Oxford University Press's Blog, page 75

June 25, 2022

The perennial problem of succession [long read]

These days it is perhaps difficult to put oneself emphatically into a world in which the dynastic realm appeared for most men as the only imaginable ‘political’ system”, writes Benedict Anderson in Imagined Communities, his seminal book on the origins of modern nationalism. But this was the world a large majority of all Europeans lived in before the French Revolution and in many cases up until the First World War.

In this world, the monarch was normally a distant figure for the large majority of all men and women in society. But whether the monarch was young or old, in good health or ailing, lived or died mattered for both the grand and mighty and for the common man. Between AD 1000 and 1800, political stability in Europe revolved around what my co-authors, Andrej Kokkonen and Anders Sundell of Gothenburg University, and I have termed ”the politics of succession”. The death of monarchs created moments of insecurity and instability, which only came to an end when a new monarch had established him- or (very rarely) herself on the throne.

Successions were violent moments, marked by both civil war and international war (the numerous “wars of succession” in European history). Monarchs were sometimes deposed in anticipation of this, and new monarchs were regularly forced to call and consult parliaments to solidify their position. Successions and interregnums were dangerous periods where the powerful could lose everything, depending on who would take the throne, and where foreign powers might be tempted to intervene to back their candidate for the throne or, in rare occasions, to win it for themselves. Likewise, when a child came to the throne and was unable to govern in his right, the result was often political instability.

A good example is the death of King John Lackland in 1216 and the difficult circumstances faced by his successor, the nine-year-old Henry III, or rather his regency, dominated by the septuagenarian William Marshal, popularly known as the greatest knight of his age. On behalf of young Henry, the Marshal had to fight a civil war, which saw an aborted attempt by the French crown prince Louis (later Louis VIII of France) to take the English throne, and Henry’s regency had to give a string of political concessions, including recurrent reconfirmations of Magna Carta.

In a world of high mortality where even men in their prime would regularly die from what we today would consider trivial diseases, the spectre of succession haunted European states and made long-term investments in administrative and political institutions difficult. History shows that even great realms can make or break depending on how they dealt with the perennial problem of succession. The mighty empires established by Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and Charlemagne all fell apart as a result of succession conflicts, in Alexander’s case between his generals, in the cases of Genghis Khan and Charlemagne between their grandsons. Only by developing institutions that regulate the politics of succession is it possible for a realm to have staying power and systematically augment its administrative and military institutions.

Solving the problem of succession: introducing primogenitureLooking at the different solutions that were tried out in medieval and early modern Europe, the results are striking: the introduction of primogeniture (eldest-son-taking-the-throne) hugely increased the odds that realms would be able to cope with succession conflicts. Primogeniture originated in what is today France and Northern Spain around AD 1000 and it gradually spread to most of Western and Central Europe.

The notion that the eldest son takes the bulk of the inheritance has played such an important role in European history that many believe it is the historical normal. Recently, my fourteen-year-old son Erik seemed to assume he would one day inherit my father’s seaside cottage because he is the eldest son of an eldest son (never mind his two younger brothers, or my two younger siblings). But when it arose around AD 1000, the idea of disinheriting all family members save one was revolutionary. It was only possible because the Catholic Church had upended the traditional heirship policies and paved the way for the monogamist marriage and the nuclear family. Strict rules about legitimacy were simply a requirement for getting primogeniture to work. But once it worked, it was to have long-term consequences for European state-building.

Primogeniture replaced succession orders such as elective monarchy and agnatic seniority (eldest-brother-taking-the-throne) which caused much more instability. This calmed the troubled waters of succession, the most famous example being the 300 years of smooth and uninterrupted father-to-son successions among the French Capetians, until they died out in the direct male line in 1328.

The main virtue of primogeniture was that it addressed the catch-22 of succession: the need to, on the one hand, assure elites that the regime will be prolonged into the future and, on the other hand, avoid nurturing a dangerous rival in the form of a designated crown prince. Queen Elizabeth I of England is but one of many sovereigns who have hesitated to name a successor for fear that it could come back to haunt her. As she once told the Scottish ambassador: “I know the inconstancy of the people of England, how they ever mislike the present government and have their eyes fixed upon the person who is next to succeed.” But in the context of primogeniture, monarchs would—insofar as they were able to beget a son (or daughter where women could inherit, as in the case of Elizabeth herself) —produce automatic heirs who were by definition a generation younger and could therefore better afford to wait their turn than, say, a younger brother.

Primogeniture monarchies thereby succeeded in creating a new political theory of monarchy: the idea that while individual monarchs might die, the Monarch would live forever, symbolized in some places by the paradoxical cry, “the king is dead long live the king”. This innovation did away with the dangerous interregnum we find in succession orders such as elective monarchy and it paved the way for the spectacular state-building process that centuries later culminated in territorial states such as England and France, or our own native Denmark and Sweden. This happened despite the fact that primogeniture had one important Achilles Heel: it regularly produced heirs who were underage when coming to the throne. As historian Christopher Tyerman observes, “In monarchies where an element of hereditary succession, especially primogeniture, had become established, minorities were inevitable, paradoxical destabilizing tributes to greater dynastic stability, the right of the genetic heir overcoming the practical need for leadership.”

These minorities almost invariably created political instability but even this did not undermine the competitive edge of primogeniture. As the German-American historian Ernst Kantorowicz pointed out in his 1957 classic, The King’s Two Bodies, the result of primogeniture was the idea of an immortal royal body politic, distinct from the body natural of the individual king. According to Kantorowicz, this doctrine was ultimately derived from Christian theological thought; the corpus mysticum of the realm was a reflection or even an outgrowth of the corpus mysticum of the Church.

The problem of succession in today’s authoritarian regimesHowever, despite all the differences in context, the core problem of medieval succession politics finds echoes in the contemporary world. In today’s authoritarian regimes, the challenge is the same as in Europe’s past: to groom a successor who can placate the elites without risking that this successor will hasten the power transfer via a coup. Faced with this choice between a rock and a hard place, most contemporary authoritarian rulers choose not to groom a successor for fear of the Crown Prince Problem. One of the consequences is that many dictatorships do not outlive the death of their first leader. Successions are thus still dangerous periods in undemocratic states, where civil war is a real risk, and where the political elites fear being sidelined by whoever comes out on top in the succession conflict. A looming succession therefore often creates instability. Take the most important non-democratic state today: who is to eventually replace Xi Jinping, and how can this be done without creating chaos, now that the self-assured Chinese general secretary has done away with the rotation principle established by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s?

In many authoritarian regimes, rulers have tried to ape hereditary monarchy by grooming the eldest son for power. But as presidents such as Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and Muammar Gaddafi in Algeria learned at their peril, it is difficult to do this in a context where the dynastic realm is no longer the natural political system. To return to Benedict Anderson: “in fundamental ways ‘serious’ monarchy lies transverse to all modern conceptions of political life.” And even in today’s few remaining monarchies, successions are often high risk periods, especially where the rules governing it are vague. For instance, what will happen in Saudi Arabia when King Salman dies? Will his brutal and mercurial son, Mohammed bin Salman, be able to take the throne as he plans or will disgruntled members of the Saudi Royal family rise and seek to sideline him?

How does representative democracy compare with hereditary monarchy in the problem of succession?All of this brings us to the great modern-day alternative, representative democracy. How does it fare in comparison when it comes to power transfers and political stability? Interestingly, this regime form—unknown to Europeans in the period we analyze in The Politics of Succession—can be cast as a solution to the problem of succession. At its core, representative democracy is a recipe for recurrent and peaceful power transfers, via elections. This was the great insight of the Austrian economist Joseph A. Schumpeter’s minimalist theory of democracy, presented in the book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. To quote one of his pithy sentences: “The principle of democracy then merely means that the reins of government should be handed to those who command more support than do any of the competing individuals or teams.” This might not sound especially impressive. But as another Austrian, the philosopher Karl Popper, has emphasized, “There are in fact only two forms of state: those in which it is possible to get rid of a government without bloodshed, and those in which this is not possible…Usually the first form is called ‘democracy’ and the second ‘dictatorship’ or ‘tyranny’.”

This was starkly illustrated in the United States in the months after the presidential election in November 2020. Breaking a venerable tradition of US politics, the loser, Donald Trump, refused to concede. The result was a democratic succession conflict, where Trump, as the incumbent, tried to leverage public opinion, his party, and the presidential administration to get the result in a series of crucial “Swing States” overturned. However, the US democratic institutions stood firm—from courts of law to the top officials at the Department of Justice to the local Republican officials overseeing the election—and at the end of the day, Trump had to vacate the White House. To be sure, this only happened after months of drama, climaxing in the shocking storming of the Capitol by Trump supporters on 6 January 2021. But in other political systems, where no similar guardrails exist, a conflict like this would probably have been settled by raw violence.

If primogeniture is the second-best solution of the perennial problem of succession, modern representative democracy is thus arguably the best! That this is in fact the major contribution of democracy to modern civilization is often forgotten today because many have a hard time viewing democracy in such as mundane way, instead expecting it to solve all sorts of other problems. As our book shows, history serves to remind us of this brute and simple fact.

June 24, 2022

Almost “nothing”: why did the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand lead to war?

Shot through the neck, choking on his own blood with his beloved wife dying beside him, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Habsburg Empire, managed a few words before losing consciousness: “It’s nothing,” he repeatedly said of his fatal wound. It was 28 June 1914, in the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo. One month later, what most Europeans also took for “nothing” became “something” when the Archduke’s uncle, Emperor Franz Joseph, declared war on Serbia for allegedly harboring the criminal elements and tolerating the propaganda that prompted the assassination. The First World War began not with Gavrilo Princip’s pistols shots, but because European statesmen were unable to resolve the July [diplomatic] Crisis that ensued.

That crisis may have been short-lived, but the conflict between the venerable Habsburg Empire (Austria-Hungary) and the upstart (and far smaller) kingdom of Serbia had been brewing for decades. At its core were the South Slavs of Bosnia-Herzegovina—Muslims, Catholic Croats, and, above all, Orthodox Serbs that Serbia claimed as its rightful irredenta, its “unredeemed” peoples. Austria-Hungary had administered Bosnia since taking over from the declining Ottoman Empire in 1878. It poured enormous resources into developing the territory economically, though scant benefits were seen by peasants like Princip’s family, who resented their poverty and repression under Austrian rule as much as they had the Ottomans’ long reign. Then, in 1908, the Habsburg Empire annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina outright. For the next six months, the Bosnian [annexation] Crisis convulsed Europe. It has been called the prelude to World War I, though it by no means made that war “inevitable.” Russia, which sought control over the central Balkan region possibly through its partner state Serbia, was too weak to fight back in the wake of its defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. And while the Serbs were, literally, up in arms and made a big show of mobilizing their meager army, they stood no chance without Russian backing. Meanwhile, the annexation was accepted by the other Great Powers as a fait accompli.

It would be easy to conclude from this sparse summary of Balkan tensions that the Sarajevo assassination was driven by Serbian resentment over Austrian control of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Such an interpretation is strengthened by the fact that myriad accounts of the political murder depict Princip and his accomplices as “Serbs” or “Serb nationalists” backed by a “secret” Serbian “terrorist” organization: Unification or Death, more notoriously known as the Black Hand. It’s all very subversive and satisfying to our contemporary sensibilities. Some scholars have thus even latched onto analogies between the Black Hand “terrorist network” and today’s Islamic fundamentalists. The issue is not merely inaccuracy or exaggeration, but that it’s part of the mythology that has accumulated around the Sarajevo assassination.

It’s true that the assassins concocted their plot in Belgrade and obtained their weapons, training, and logistical support in Serbia. Yet no official Serbian organization sponsored them, and there’s no evidence that anyone but rogue rebels in the Black Hand acted to aid the Bosnians, rather than the highly nationalist military faction itself. Far closer to the truth is that Princip and his co-Bosnian conspirators needed no more motivation to organize and execute the assassination than their patent suffering under Habsburg rule, as they insisted repeatedly at their trial. Serbia, meanwhile, did not need a war with a European Great Power, particularly on the heels of its hard-fought victories in the Balkan Wars (1912/1913). The Black Hand leaders knew this, which is why there’s evidence that they actually tried to stop the conspiracy that they never initiated in the first place. Yet the demonization of official Serbia and its uncontrollable nationalist factions persists as the main explanation for the Sarajevo assassination.

This should not be surprising, and not because the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s put Serbian nationalism again on display. No, the reason the alleged Serbian backing of the Sarajevo assassination is so compelling is the war itself—for how to explain the Sarajevo assassination has become an escape hatch for the true criminals in Europe’s “civilized” capitals. Thus, the myth of Sarajevo includes the endless stereotypes of the “savage” and “war-prone” Balkan peoples, “fanatic” Serb nationalists, “terminally ill” (with tuberculosis) assassins, and that ubiquitous explanation for everything—Europe’s “fate” and Princip’s “chance.” After all, who has not heard of the “wrong turn” taken by the heir’s car after he narrowly escaped a bomb attack that very morning; or wondered why the imperial procession had even continued after the near miss; or pondered how Princip’s first bullet happened to kill the one person he wished to spare: Franz Ferdinand’s wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg? There was so much happenstance on that “cloudless” Sunday of Europe’s over idealized “last summer” that it is all too easy to forget that the initial decision for war with Serbia was taken in Vienna, not Sarajevo, and it was made with full knowledge of possible Russian intervention and, thus, European war.

The Sarajevo assassination did not “shock” the world. Nor was it a “flashbulb event” that imprinted itself on the minds and memories of all contemporaries. On the contrary, countless first-hand accounts support the relative apathy and indifference that greeted the murder—a tragedy, certainly, but not one which, as British undersecretary of state Sir Arthur Nicolson wrote eerily to his ambassador in St. Petersburg, would “lead to further complications.” What “changed everything” was not a Bosnian assassin’s poorly aimed bullets, but the historical misfire by Europe’s Great Powers, which first came to light with Austria-Hungary’s ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July 1914. By then, the Sarajevo assassination was slipping from memory—this was an age, after all, in which political murder was all too common; or, as one American newspaper casually put it, there were other Austrian heirs to replace the Archduke. But Austria-Hungary had had enough of Serbian irredentism, despite the fact that its investigators found no evidence whatsoever of Belgrade’s collusion in the Sarajevo conspiracy. And Franz Ferdinand’s final words about his fatal wound—“it’s nothing”—would never seem more ironic than when the “first shots of the First World War” were fired—not in the Bosnian capital on 28 June 1914, as myth has it, but by Austrian gunboats against Belgrade a full month later.

Featured image: from Washington Examiner, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

June 23, 2022

Guns and the precarity of manhood

This is an excerpt from chapter 6, “Enraged, Rattled, and Wronged” of

Enraged, Rattled, and Wronged: Entitlement’s Response to Social Progress

by Kristin J. Anderson.

This is an excerpt from chapter 6, “Enraged, Rattled, and Wronged” of

Enraged, Rattled, and Wronged: Entitlement’s Response to Social Progress

by Kristin J. Anderson.Manhood is precarious. Unlike womanhood, manhood is hard won and easily lost and therefore men go to great effort to perform it—for the most part for other boys and men—sometimes to their own and others’ detriment.[63] Men will go out of their way to not appear unmanly or feminine—they adhere to an anti-femininity mandate. For example, men are reluctant to take jobs that women do. Men hold out for diminishing coal-mining jobs when they should be applying for home health aid jobs. Women have been flexible and have pushed themselves into men’s jobs; men have not pushed themselves into women’s jobs.[64]

There are consequences of the investment in maintaining manhood for individual men, as well as the rest of us. Men learn to be fixated on performing masculinity which often entails aggression. Men tend to believe that aggression is more typical than it actually is—as we learned earlier. They falsely believe that women are attracted to aggressive men, when, in fact, women tend to view aggression as weak and impulsive, a loss of self-control, and not sexy or charming.[65]

Gun popularity among men is linked to threats to their gender status … How do we know? First, men with higher sexism scores believe it should be easier to buy guns; men with lower sexism scores say it should be more difficult to buy guns.

Entitlement tells White men that they shouldn’t have to bow down to those they perceive to be below them. In 2018, Markeis McGlockton, an African American man, pushed a White man to the ground because the man was yelling at his partner outside a convenience store. The man pulled out a gun and shot and killed McGlockton and was not prosecuted because of Florida’s stand-your-ground law.[66] Stand-your-ground laws and gun ownership are manifestations of feeling entitled to never back down. Gun owners often justify owning or carrying a gun with fears of violent crime however, over the same period in which gun purchases have risen, violent crime has dropped. In truth, support for gun rights for White men is linked to perceived threats to their racial privilege.[67] Gun popularity among men is linked to threats to their gender status as well. How do we know? First, men with higher sexism scores believe it should be easier to buy guns; men with lower sexism scores say it should be more difficult to buy guns.[68] Second, firearm background checks increase in communities where married men, but not married women, have lost their jobs.[69] Presumably, recently unemployed men become interested in guns at a time they feel vulnerable. In addition, when wives out earn their husbands, gun sales increase. [70] These men seem to see guns as one way to shore up masculinity. As we saw above, Jonathan Metzl’s work finds that guns are used by White men as a means of preserving racial privilege, even as Whites wind up being disproportionately harmed by the presence of guns.[71]

It turns out in laboratory studies it’s pretty easy to threaten men’s masculinity into panic that then motivates them toward compensation. It’s worth taking a second look at a study described in Chapter 4 where Julia Dahl [72] and her colleagues asked young and mostly White men to complete a “gender knowledge test.” During this test participants were asked questions such as, “What is a dime in football?” and “Do you wear Manolo Blahniks on your head or feet?” The respondents were then randomly put into either a threat condition—being told they scored similar to the average women—or a no-threat condition—being told they scored like the typical man. Their grouping had nothing to do with their actual answers on the test. Men threatened by being associated with women were more likely to feel embarrassed by their responses, angry, and wanted to display dominant behaviors. Anger predicted greater endorsement of ideologies that implicitly promote men’s power over women. Specifically, men’s social dominance orientations and benevolent sexism (and both are correlated with entitlement) increased if they were exposed to the masculine threat. How did the threatened men in this study appease that threat to their masculinity? By endorsing the legitimacy of men’s societal power over other groups, particularly women.

Featured image by Jari Hytönen on Unsplash, public domain

A caution in exploring non-Western International Relations

The past quarter of a century has seen a burgeoning scholarship on the disciplinary history of International Relations (IR). By re-examining and revealing how past intellectuals and experts wrote about “the international,” this revisionist work on IR history generates a critical gaze at the assumptions on which IR stands today. Specifically, it has highlighted the imperial, settler-colonial, racist, and gendered origins of the discipline. Consequently, foundations are being laid for IR academics to awake from that “norm against noticing” which has long characterized IR. We are beginning to realize how certain significant traditions, theories, and voices have been erased during the course of its development and are thinking about what this loss means to knowledge production in it.

At the same time, we witness a growing interest in a post-Western IR and a global IR. This trend is largely stimulated by a similar motivation: exploring those issues, concepts, and theories which have been excluded from Eurocentric IR. One of the basic approaches here is to duly acknowledge the agency of non-Western actors and experts. They are not simply the recipients of Western international system and IR, but the independent agents who have actively remolded them.

My analysis of Colonial Policy Studies (CPS) in pre-WWII Japan—in the special issue of International Affairs “Race and imperialism in IR”—not only fits into this academic tide, but also gives a caution to those scholars who engage in a post-Western IR. I show that the important origins of Japanese IR, as much as Western IR, lie in an imperial frontier, colonial rule, and racism. This can serve as a lesson for those seeking an alternative in non-Western IR. At least under the geographical division of West and non-West, non-Western IR may not totally be immune from the same pitfall as Western IR; the de-Westernization of IR may not necessarily lead to de-imperializing and decolonizing it. If we try to square an epistemic partiality, it will be necessary to think carefully about what non-Western means.

As a medium for the racialization of the worldCPS composed an epistemic industry to run the frontiers of the Japanese empire before WWII. It was instrumental in devising, authorizing, and legitimating the Japanese government’s colonial management policies. CPS also played a noteworthy role in pushing the imperial boundaries by promoting transborder migration, settlement in terra nullius or among “savages,” and overseas capital investment. Indeed, many proponents of this study area offered ideologies of settler colonialism for Japanese emigrants across the Pacific Ocean.

CPS formed a transdisciplinary area that straddled various fields, including economics, history, political science, law, and agricultural administration. It was, however, profoundly shaped by the fashionable research of the time in evolutionary biology, eugenics, and race science. CPS thus gave rise to pseudo-scientific ideas about the diversity and heterogeneity of humankind in imperial frontiers. It was this study area that constituted one of the key origins of Japanese IR, which became institutionalized after WWII. Specifically, CPS impacted on the creation of its two subfields: Area Studies and International Political Economy. This stemmed from the fact that CPS dealt with a variety of the world’s colonial regions and multiple transborder socio-economic issues such as capital flows and migration.

Given these features of CPS, it can be regarded as a parallel to early Western IR marked by imperialism and racism. As a collection of historians, including Robert Vitalis, John M. Hobson and Duncan Bell, have shown, the harbingers of Western IR—such as J.A. Hobson, Paul Reinsch, Ludwig Gumplowicz, Alfred Mahan, Halford Mackinder, Lionel Curtis, and Alfred Zimmern, to name only a few—helped racialize the modern world through their Eurocentric international theories. The proponents of CPS were East-Asian counterparts to these spokespersons for early Western IR. Specifically, they were complicit in creating racial hierarchies within non-white populations and embedded such hierarchies in non-Western knowledge. That is the oft-overlooked lacuna behind the bifurcated categories of the color-line (white and non-white).

Analysing the work of Nitobe Inazo (1862-1933) and Yanaihara Tadao (1893-1961) is useful for understanding this process. Nitobe has been famous as the author of Bushido (1899) and as a liberal internationalist committed to the League of Nations as its deputy secretary-general. At the same time, he was a key architect of CPS, holding the chair of colonial policy at the Tokyo Imperial University from 1909 to 1920. When the US ban on Japanese immigrants (the Johnson-Reed Act) was introduced in 1924, he attacked it as white chauvinism. However, such condemnation appears merely opportunistic given his racism against non-white people. Overseeing the Japanese imperial hinterland of Nan’yo (the South Seas), he theorized about multilayered racial hierarchies with the Japanese at the top, “the Malays” and “the blacks” at the bottom, and the Chinese in-between.

Yanaihara Tadao was a successor to Nitobe as the professor of colonial policy at the Tokyo Imperial University. After WWII he was closely engaged in institutionalizing IR, embodying a continuity between pre-war CPS and post-war IR. His theoretical framework for CPS was unique. Called de facto colonization (jisshitsuteki shokumin), it was a variant of settler colonialism, formulating many-sided economic and cultural interplay between transborder migrants and local populace. Some say that as Yanaihara’s colonial theory blurred the boundaries of the domestic and international, it prefigured the concept of a global civil society. However, when applied to Nan’yo, the same theory promoted racial hierarchies that discriminated against indigenous peoples. Based on a phenotypic notion of race, Yanaihara assumed that it was transnational capitals and labour of “civilized” Japanese that would modernize “underdeveloped natives” in the South Pacific. His post-war account of IR was created in the shadow of such a conception of racial stratification. When he gave lectures on IR in 1950, he posited a hierarchic globe—instead of a horizontal sovereign-states system—marked by “the advanced and backward countries.”

To a remarkable degree, early Japanese IR was instrumental in racializing people of colour. This suggests that at least in some cases, non-Western IR may also need critical inspection as has been directed to Western IR in recent years.

June 22, 2022

Long-delayed gleanings

I submitted my latest set of gleanings on 6 April. In the meantime, there has not been too much to glean; hence the delay. Now I have a full handbasket and can use it as a means of transportation in any direction, except that no new materials or ideas have come my way about the origin of soul.

IdiomsIt does seem that English is incomparably richer in phrases containing proper names (Hoppin’ John, Andrew Matin, and so forth) than other European languages. Our correspondent wrote that Russian hardly has any. Yet some such phrases did occur to me. When there is an excess of food for the guests, in Russian they say that enough seems to have been cooked for Malanya’s wedding. Characteristically, in writing, Malanya and other such names are not capitalized, and no one expects this lady to have existed. Yet the phrase must have had its origin in some situation! A very remote place is described as one to which Makar has not driven his calves. To show someone Kuz’ka’s mother means “to do the opponent great harm.” I think at one time, this idiom became famous because Khrushchev, probably in France, threatened to do exactly that to some opponent, and the French interpreter, who did not know the phrase, translated it literally with la mère de Kuzma, much to the delight of the Russians and to the utter consternation of the French. But then he also promised “to bury the West” and did not, so that Kuz’ka (which is a diminutive of Kuz’ma—stress on the second syllable) can wait. When a person is not fit for some business, they say that the cap is not for Sen’ka (the diminutive of Simon). I am sure there are more.

Hungarian has, a reader informed us, an exact equivalent of the phrase every cobbler stick to his last. I suspect that it owes its existence to the European common source, because German and French have the same idiom. By contrast, in Russian they say: “Each cricket know its stick.” (I was severely tempted to translate it with “Every cricket to its ticket.”)

Kuzma’s mother in search of sinners.

Kuzma’s mother in search of sinners.(Image via rawpixel, public domain)

A curious observation: in one of his albums, Tom Waits has so many idioms that also figure in Charles Earle Funk’s book A Hog on Ice that it probably is not a coincidence. I have no opinion, but the suggestion does not look improbable. As I once noted, modern English speakers grace their everyday speech with idioms sparingly. Apart from the common stock (to put something on the back burner and its likes), idioms are understood rather than used. (And many good idioms are not even understood.) The authors of fiction, journalists, and their colleagues are a different matter: they make a sustained effort to spice their prose with memorable phrases and often do it clumsily. Consequently, when a songwriter peppers his texts with idioms, we may indeed suspect that he used some work from which he could borrow them. Many such works exist, so that an exact source is hard to pinpoint.

Spelling and Spelling ReformThe Scripps National Spelling Bee has survived the onslaught of the pandemic and resumed its activities, and I will resume venting my impotent wrath on it, because I have always been against child abuse. A fourteen-year-old wrote correctly scyllarian, pyrrolidone, Otukian, and Senijextee. My heart goes out to her. That said, may she use those words on her first date and live happily ever after. One day she may even eclipse the character of Hans Christian Andersen’s tale “Blockhead Hans”: that youngster (not Hans) knew three years’ issue of the daily paper of the town by heart and hoped to marry a princess.

In the meantime, poor mortals fail to remember that the past tense of lead is led, while the name of the metal is lead. Never mind my students: they have more important things to learn, but even in an article published as Bloomberg Opinion we read: “This hubris is what lead the US economy into this mess.” No doubt, led is meant. Hubris indeed.

But let me remind our readers that the English Spelling Society has been active and efficient and has produced a list words that will be respelled if the Reform is accepted. Here is short sample: enuff and coff (for enough and cough); beleev, buetiful; throo (for through), kew (for queue), dyaria (for diarrhea) and bo’y (for buoy). It would be instructive to know our readers’ reaction to this sample.

Malanya’s wedding in full glory.

Malanya’s wedding in full glory.(Image by Marco Verch via Flickr, CC BY 2.0)Baby words and monosyllables

Many thanks are due to the correspondents who commented on Gothic daddjan “to breastfeed” and neatsfoot oil. Of course, I knew about this oil, but the connection with neat “cattle” did not occur to me. I may add that even such brief remarks are most helpful. I am now writing a book based on my most interesting posts (this blog is now in its seventeenth year). Not only do I rewrite the texts because separate essays and chapters in a book are different things. I also learned a lot from suggestions and corrections and incorporated them into my revised text.

Daddjan, the Gothic verb for “breastfeed.” I did consult LIV (Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben): the book stands in my office. Its etymology of daddjan is more realistic than the traditional one, but it is still different from mine. I don’t think daddjan is “Indo-European.” My risky suggestion amounts to the idea that we are dealing with a baby word like English daddy, Russian diadia “uncle,” and so forth. Such words are similar the world over, without being related: just so many mushrooms on a stump (very similar but rootless).

Dab hand. All sources agree that dab is a sound-imitative verb: one goes dab, dab, dab. Its frequentative twin dabble seems to have the same origin (even if it is a borrowing from Dutch, dab and dabble still must be related). Yet dab hand “skilled worker, apt striker (as it were)” is called a phrase of unknown origin. What exactly is unknown? Unless dab hand is a mysterious borrowing, the implication seems to be “an apt striker.” I have no literature on this phrase, and my guess is just a guess. But dab is like many other monosyllables (kick, dig, put), ancient or late, whose etymology is similar to that of dab, so that dab hand looks fully transparent.

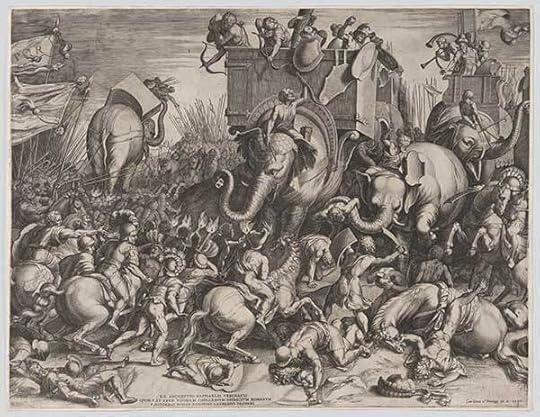

Elephants in Ancient Rome.

Elephants in Ancient Rome.(Image: “The Battle Between Scipio and Hannibal at Zama”, Cornelis Cort, via The Met, public domain)Elephants

The word elephant is a borrowing in all the European languages, too late to be part of an ancient common stock. The idea that the Romans knew elephants from the Second Punic War occurred to me too. But it is not their knowledge of Hannibal’s animals that resulted in the introduction of the word to Latin: elephpantus is a loan from Greek and, obviously, a bookish loan, because –nt– was taken over from the declined form: the Greek nominative was elephas.

Please write, send your questions, share your ideas, and voice your disagreement. Any echo in the wilderness is welcome.

Featured image via rawpixel, public domain

June 21, 2022

Moby-Dick is the answer. What is the question?

In December 2021, I was a contestant on the popular American quiz show Jeopardy! Every Jeopardy! game has a brief segment in which contestants share anecdotes about themselves, and I used my time to proselytize reading Moby-Dick. I talked about my work on the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of the novel, and emphasized that Herman Melville’s novel is unexpectedly weird, moving, and hilarious despite its monumental reputation. To my great surprise, I received scores of messages from strangers about Moby-Dick, far in excess of the notes I fielded about my actual quiz performance. Most were lovely, such as this kind email from a viewer: “your brief comments about Moby-Dick being humorous and even lighthearted at times weren’t what I was expecting…[it] led me to take another look, and to my delight, I found that you were right—right from the first page, there’s a joy and sprightliness about Melville’s writing.” Only a couple of Jeopardy! fans reached out to refute my terms (“Sexuality? Moby-Dick?” was the full text of one skeptic’s email—that correspondent, I guess, had never read as far as chapter 94, “A Squeeze of the Hand”).

To my special delight I also received an email from my middle-school English teacher, who had watched my Jeopardy! episodes and wrote about our mutual love of Herman Melville. Mr Ronkowitz—I’m assured I can call him Ken now, but I’ll retain the honorific—reads widely and generously. We’ve been corresponding over the past months about literature and teaching, and I shared with him what I wrote about Moby-Dick for the Oxford edition. My introduction focuses on the elasticity of the novel and its continued relevance for twenty-first-century readers, with new attention to Moby-Dick‘s queerness and its meditations on race, power, disability, and the environment.

In eighth grade Mr Ronkowitz had a reputation for challenging his students, and he’s still got it. “I get it that we teach literature in the context of both its time and the reader’s time,” he wrote after reading my introduction, “but to discuss Ahab’s afflictions in the context of disability studies and ‘whiteness’ in the light of critical race theory and the Black Lives Matter movement would be tough for me….My ancient undergrad study was devoid of homoerotic discussions and more about biblical and mythological allusions in the novel and tons of symbolic dimensions of the novel.” Archetypes are undeniably powerful; in a recent general public discussion of the novel that I led, readers asked me repeatedly what the whale symbolized. But unlike a quiz show, novel reading is not keyed to a single answer, or even a single question. And not everyone has Mr Ronkowitz’s willingness to do the work of questioning traditional givens.

“If Moby-Dick is the answer, then the questions asked of it are the ones that change with each new generation of readers.”

The gimmick of the game show Jeopardy! is that correct responses are given in the form of a question—the host reads the answer, and the contestants provide the question. To give one example of how the game is played: in a Moby-Dick category on the show a few years ago, the answer was “Have a cup of coffee & name this first mate aboard the Pequod”; a contestant subsequently furnished the correct question: “who is Starbuck?,” earning them $1600. Mr Ronkowitz’s acknowledgement of the difference between how Moby-Dick was taught to him in college, and how a professor like me teaches it today, shows the Jeopardy! principle in action: if Moby-Dick is the answer, then the questions asked of it are the ones that change with each new generation of readers. One of my aims for my work is to extend pathways among generations of Melville readers—past, present, future. I hope to make the case for why a potential reader might bring fresh questions to traditional understanding of Moby-Dick, and to suggest what might be the rewards of such a revisioning.

Nineteenth-century lovers of nature writing, for instance, may not have seen in Moby-Dick‘s cetological chapters an explicit alarm over extractive fossil fuel industries. Ishmael sees “honor and glory” in whaling even as he wonders—in a chapter entitled “Does the Whale’s Magnitude Diminish?—Will He Perish?”—whether “the humped herds of whales,” like the “humped herds of buffalo,” face “speedy extinction.” To present-day readers attuned to the environmental consequences of natural resource depletion, the hunt for Moby Dick stands in for the industrialized world’s self-annihilating quest for ever more elusive sources of fossil fuel to power industry.

It may be hard, as Mr Ronkowitz writes, to reopen what may have seemed to be settled questions but embracing difficulty can be generative both of new ideas and more just worlds. Throughout Moby-Dick, Melville insists that judgment, interpretation, and truth are contingent and slippery concepts, shaped by embodied experience and by the time and place of their consideration. We see this in Ishmael’s quick pivot from recoiling from Queequeg’s “cannibal” aspect to embracing him in culturally relativist marriage; in the Pequod sailors’ belief that Pip is mad rather than in possession of divine knowledge after his soul drowns; in the wildly divergent readings the crewmen offer of the doubloon that Ahab has nailed to the mast; in Ishmael’s own narrative fits and restarts. For every answer, Moby-Dick proliferates questions.

Melville justifies this promiscuity of meaning as an artistic necessity for producing a “grand” work: “small erections may be finished by their first architects; grand ones, true ones, ever leave the copestone to posterity. God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draught—nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!” The grandness of Melville’s work lies in this very incompletion, in its recognition that the hoped-for readers to come in “posterity” will continue to refurbish and build additions onto the frame that Moby-Dick provides. What I especially love about this particular passage is how Melville acknowledges that his novel is not static, not fixed in time (and hardly timeless!), but an evolving project, extending from the present of its composition in both past and future iterations.

Moby-Dick remains alive to the questions that readers might bring to it, as my reconnection with Mr Ronkowitz—Ken—reminds me. In an era of economic and educational precarity, injustice and power imbalances, violence, and environmental crisis, what better hope than to connect with others also engaged in questioning—to feel what Ishmael calls the “universal thump”—and to continue the work of building more inclusive and accessible structures

Featured image by Ray Harrison via Unsplash, public domain

June 20, 2022

How can we build the resilience of our healthcare systems?

Healthcare is an important determinant in promoting the general physical, mental, and social well-being of people across the globe. An effective and efficient healthcare system is a key to the good health of citizens and plays a significant contribution to their country’s economy and overall development. Poor health systems hold back the progress on improving health in countries at all income levels, according to a joint report by the OECD, World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Bank. The attainment of Universal Health Coverage, the overarching target that should facilitate achievement of health and non-health targets of Sustainable Development Goals, is directly concerned with the performance of the health system.

Globally, healthcare systems have experienced intensive changes and reforms over the past 30 years, which has led to improvement of healthcare. We have seen during the recent COVID-19 pandemic that the countries with robust healthcare systems were less affected compared to those with fragile health systems. However, in general, COVID-19 has also exposed weaknesses in our health systems that must be addressed. The crisis demonstrated the importance of equipping health systems with good governance and leadership, harnessing efficient human resource, maintaining uninterrupted supply chain systems, equitable allocation of financial resources, efficient information and surveillance mechanisms, along with robust service delivery to the community.

Resilience is defined as the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; or physical, mental or emotional toughness. Thomas Edison once said “I have not failed. I just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” Such is the ability of any health organization which is either not deterred by difficult circumstances or bounce back to the normal as soon as those circumstances tide off. The healthcare systems of all countries, especially low- and middle-income countries, should be resilient enough to view difficulty as a challenge and opportunity for growth, visualize the effects as temporary rather than permanent, and not let setbacks affect unrelated areas. These health organizations should invest their time and energy in strategic and operational planning; monitoring and evaluation of their key result areas; management of time, stress, and self; material, money, and man-power management; sound health information systems; undertaking innovations and developing good inter-sectoral partnerships and networking. Resilient organizations should also focus on good communication, quality assurance, patient satisfaction, health sector reforms, and building leadership and management skills among healthcare providers.

There is a dire need for training of the public health managers in low- and middle-income settings on how to build a resilient healthcare system that is not only effective and efficient in routine healthcare but also able to adapt to crisis situations. Such trainings should be provided through live examples and case studies healthcare professionals can visualize and apply in resource constrained health settings. The experiences and expertise of people working in health systems, academia, and non-governmental organizations at various levels should be harnessed in such trainings for documentation of good and replicable practices pertaining to different building blocks of health system.

There are a few forums in developing countries that aim at building the capacity of public health managers and students through developing essential skills required for strengthening healthcare systems. Besides these, there are no books on healthcare systems which are case study-based, practical, and holistically cover the subject. The current books are highly theoretical and are mostly from developed countries, the learning from which may not be fully applicable in our settings of low- and middle-income countries. The book Management of Healthcare Systems bridges the gap by providing a comprehensive, curriculum-based source of reference for faculty and students of health management and administration who are pursuing higher degrees in community medicine, public health, hospital and health management, and also to those who are practicing health and hospital management in public and private hospitals.

So, what are the key takeaways? First, the most important thing is that the health system should be resilient enough to take on the adversities upfront without frailing. Second, we need to inculcate the necessary skills among healthcare providers so that they sustain the momentum even in the stressful situations. Third, we need to allay the myth that building resilience within the organization cannot be learnt. Fourth, health organizations need to spend time and energy in building certain management and leadership skills among healthcare providers to build a resilient healthcare system.

In summary, as an industry, we need to critically look at how resilient our healthcare systems are. How can we build further resilience? What are our limitations and challenges which can be converted into opportunities and challenges? And lastly, do we have a strong healthcare system that can overcome any crisis, including COVID-19 and similar pandemics?

June 17, 2022

Eight books to read to celebrate the 1900th anniversary of Hadrian’s Wall

2022 marks the 1900th anniversary of the beginning of the construction of Hadrian’s Wall. For almost 300 years, Hadrian’s Wall was the northern frontier of the Roman empire. It was built by the Roman army on the orders of the emperor Hadrian following his visit to Britain in AD 122 and was made a World Heritage Site in 1987.

To commemorate this anniversary, we’re sharing a selection of titles exploring the history of Hadrian’s Wall, ancient Rome’s influence on British identity, the new approaches being developed in Roman archaeology, and more to read and enjoy.

1. Conquering the Ocean: The Roman Invasion of Britain by Richard HingleyThis book provides an authoritative new narrative of the Roman conquest of Britain, from the two campaigns of Julius Caesar up until the construction of Hadrian’s Wall. It highlights the motivations of Roman commanders and British resistance fighters during a key period of Britain’s history.

Read: Conquering the Ocean

2. London in the Roman World by Dominic Perring

2. London in the Roman World by Dominic PerringThis original study draws on the results of latest archaeological discoveries to describe London’s Roman origins. It offers a wealth of new information from one of the world’s richest and most intensively studied archaeological sites.

Read: London in the Roman World

3. Destinations in Mind: Portraying Places on the Roman Empire’s Souvenirs by Kimberly CassibryIn Destinations in Mind, Kimberly Cassibry asks how objects depicting different sites helped Romans understand their vast empire. At a time when many cities were written about but only a few were represented in art, four distinct sets of artifacts circulated new information—including bronze bowls that commemorate forts along Hadrian’s Wall.

Read: Destinations in Mind

4. Britain Begins by Barry Cunliffe

4. Britain Begins by Barry CunliffeBritain Begins is nothing less than the story of the origins of the British and the Irish peoples, from around 10,000BC to the eve of the Norman Conquest. Using the most up to date archaeological evidence, together with new work on DNA and other scientific techniques to trace the origins and movements of these early settlers, Barry Cunliffe offers a rich narrative account of the first islanders—who they were, where they came from, and how they interacted one with another.

Read: Britain Begins

5. Hadrian’s Wall: A Life by Richard HingleyIn Hadrian’s Wall: A Life, Richard Hingley addresses the post-Roman history of this world-famous ancient monument. This volume explores the after-life of Hadrian’s Wall and considers the ways it has been imagined, represented, and researched from the sixth century to the internet.

Read: Hadrian’s Wall

6. Boudica: Warrior Woman of Roman Britain by Caitlin Gillespie

6. Boudica: Warrior Woman of Roman Britain by Caitlin GillespieBoudica: Warrior Woman of Roman Britain introduces readers to the life and literary importance of Boudica through juxtaposing her different literary characterizations with those of other women and rebel leaders. This study focuses on our earliest literary evidence, the accounts of Tacitus and Cassius Dio, and investigates their narratives alongside material evidence of late Iron Age and early Roman Britain.

7. The Oxford Handbook of Roman Britain edited by Martin Millett, Louise Revell, and Alison MooreThis book provides a twenty-first century perspective on Roman Britain, combining current approaches with the wealth of archaeological material from the province. This Handbook reflects the new approaches being developed in Roman archaeology and demonstrates why the study of Roman Britain has become one of the most dynamic areas of archaeology.

Read: The Oxford Handbook of Roman Britain

8. Celts, Romans, Britons: Classical and Celtic Influence in the Construction of British Identities edited by Francesca Kaminski-Jones and Rhys Kaminski-Jones

8. Celts, Romans, Britons: Classical and Celtic Influence in the Construction of British Identities edited by Francesca Kaminski-Jones and Rhys Kaminski-JonesThis interdisciplinary volume of essays examines the real and imagined role of Classical and Celtic influence in the history of British identity formation, from late antiquity to the present day. Britishness is revealed as a site of significant Celtic-Classical cross-pollination, and a context in which received ideas about Celts, Romans, and Britons can be fruitfully reconsidered, subverted, and reformulated.

Read: Celts, Romans, Britons

Feature image via Pixabay

June 15, 2022

Bachelors and bachelorettes

Last month, thousands of young men and women finished high school. Some will go to college and become BA’s and BS’s, though nowadays, fewer and fewer choose this path. In any case, since May, I have been meaning to write a post about the word bachelor. There were two reasons for my procrastination: the origin of bachelor remains undiscovered, and I have nothing new to say about it. But even rehashing common knowledge is sometimes a useful procedure. So here we are.

No one doubts that bachelor came to Middle English at the end of the thirteenth century from Old French and meant “a young knight.” Some time later, the sense “university graduate” turned up. The Old French noun, the source of the English one, was bacheler “a young man aspiring to knighthood.” The other related forms are Italian baccalaro and so forth. Their common source must have sounded approximately like baccalaris, but only baccalarius, referring to some kind of peasant, and baccalaria “a kind of landed tenure” exist (see below).

Laurel berries: food for laureates and bachelors.

Laurel berries: food for laureates and bachelors.(Image by Manfred Richter from Pixabay, public domain)

Most conjectures about the etymology of this mysterious word were offered long ago. Bachelor looks like a Latin compound, possibly meaning “laurel berries,” from Latin bacca “berry” and laurus “laurel.” Samuel Johnson, the author of a famous dictionary (1755), explained: “Bachelors, being young, are of good hopes, like laurels in the berry.” Thomas Hearne, a noted antiquarian of the first half of the eighteenth century, traced bachelor to Latin baculus “stick,” because, he said, “when men had finished their exercises in the Schools, they then exercised themselves with sticks in the streets.” Did they? I have no notion. Noah Webster also considered baculus to be the etymon, but he took “stick” for “shoot,” that is, “offshoot.”

Finally, Old Irish bachlach “peasant; shepherd” (from the unattested form bakalākos), that is, “a man with a staff” was at one time pressed into service. Hensleigh Wedgwood, the main English etymologist of the pre-Skeat era, also wrote that there was “little doubt” (the most fateful turn of speech in historical reconstruction) about the Celtic origin of bachelor but cited the forms baches and bachgen: according to his hypothesis, the clue must have been hidden in Welsh bach “small, young.”

It was the French scholars Jean A. Schéler and August Brachet who put an end to this period of guess etymology. They cited the Vulgar (that is, post-Classical, popular) Latin noun baccalarius, originally “cowherd,” in which b had been allegedly replaced with v. The root turned out to be Latin vacca “cow” (Engl. vaccine, a word we now happen to know only too well, has this root.) This conjecture looked much more convincing than any of the previous ones, and Skeat accepted it in the first edition of his etymological dictionary. That dictionary, like the OED, was published in installments. By the time the entire volume had been printed, Skeat had withdrawn his positive assertion of his original idea and returned to Welsh (in the supplement Errata et Addenda).

Fighting with sticks: may bachelors enjoy themselves.

Fighting with sticks: may bachelors enjoy themselves.(Image from Old English Sports by Peter Hampson Ditchfield, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Before going on, I should state only one fact that remains undisputed: whatever the etymology of bachelor, its original and principal sense was not “an unmarried man.” It referred to the young male’s inferior social and economic status. Incidentally, the Old English word for “bachelor” has come down to us. It was hago-steald, approximately “the owner of a piece of landed property” (haga continues into Modern English in the nearly forgotten form haw, recognizable in hawthorn). It also meant “retainer, young warrior.” “Unmarried” seemingly went back to the sense “independent.” In later German, the second component, related to –stald, meant nothing to speakers, and the word was changed to Hagestolz, with stolz “proud” (!) substituted for stald. Possibly, the original reference was to the younger brother as the owner of a “haw,” while the elder son inherited the chief house. (Such is one of the more reasonable explanations.) Curiously, the Norwegian dialectal word hogstall means “widow” (a sad form of independence!).

I have mentioned hago-steald because, if the etymon “cowherd” for bachelor was right, the Romance word turns out to be a compound, somewhat reminiscent of the Germanic one, a noun with a broad range of senses, from “landowner” to “retainer” and even “a man, not burdened with property.” The idea that in the Middle Ages, someone translated the Germanic feudal term into Romance looks at least plausible. Kin terms do sometimes go back to foreign words denoting one’s social and economic status. For example, husband is a borrowing from Scandinavian, originally a compound of hús “house” and bóndi “tenant, owner.”

No longer a bachelor.

No longer a bachelor.(Photo by Jonathan Borba on Unsplash, public domain)

In 1885, the section of the first volume of the OED with the word bachelor appeared. James A. H. Murray, the OED’s editor, offered a quick survey of the older conjectures. His verdict was: “Of doubtful origin.” Skeat, in the later editions of his dictionary, followed Murray, and so did all the other authoritative sources.

A perennial benefactor.

A perennial benefactor.(Photo by Wolfgang Hasselmann on Unsplash, public domain)

We remember that there have been attempts to connect bachelor with Latin vacca “cow.” The change of v to b needed an explanation. We’ll presently return to this difficulty. The key words in our search are baccalaria “a tenure, a form of feudal real estate” and baccalarius (a noun or an adjective applied to people). The suggested development may have been from bacca “cow” to the unattested word baccalis “having relation to cows” and baccalaria, “a place having relation to cows,” with reference to a minor place of farm dependency. The baccalarius of medieval charters may indeed have been a cowherd. Cow herding in Western Europe, like sheep herding in medieval Iceland, usually the charge of young people, was looked upon as the least prestigious occupation available. Hence a possible late sense of baccalarius “adolescent.” Now back to the v ~ b problem. Characteristically, the word baccalaria “the farm dependency” most often occurred in the part of southern France in which b and v alternated in a rather haphazard way. If this phonetic handicap can be removed, Latin vacca “cow” will have its fifteen minutes of (etymological) fame.

This reconstruction, dating back to a 1911 paper in an American Festschrift, looks worthy of attention, and if it proves correct, the opaque word bachelor may lose part of its mystery. It remains for me to add that in colleges, before the fifteenth century, the word bachelor was applied to a young man in apprenticeship (!) for the degree in one of the higher colleges, that is, of theology, law, or medicine.

Featured image by Pang Yuhao on Unsplash, public domain

An enslaved Alabama family and the question of generational wealth in the US

Wealthy Alabama cotton planter Samuel Townsend invited the attorney to his home in 1853, swearing him to secrecy. His elder brother Edmund had recently died, and the extensive litigation over Edmund’s estate had made it clear to Samuel that he needed an airtight will if he wanted to guarantee that his chosen heirs would inherit his fortune. With an estate worth more than $200,000 dollars in the 1850s, Samuel was the equivalent of a modern multimillionaire. He wanted to leave this estate to his children and his brother’s daughters when he died—an ordinary enough wish. The trouble was this: all of these children were enslaved.

Like countless white men across the antebellum South, the unmarried cotton planter Samuel and his brother Edmund both fathered children with enslaved women they owned on their vast plantations. In his will, Samuel wrote that he wanted his sons and daughters to be treated exactly as though they were “white children,” giving them their freedom and an immense inheritance when he died. That was easier said than done. Because the law of slavery in the United States declared all children of enslaved women to be slaves themselves, Samuel’s five sons, four daughters, and two nieces were legally his property, and property wasn’t supposed to inherit.

The attorney Samuel hired, however, did the nearly impossible, and in 1860—four years and two lawsuits after Samuel’s death in 1856—the old planter’s will was declared valid, making the Townsend children their enslaver’s rightful heirs. Over the following decades, the Townsends would traverse the country, searching for communities where they could exercise their newfound freedom and wealth to the fullest. Through the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the rise of Jim Crow, the Townsends’ money and mixed-race ancestry granted them opportunities unavailable to most other freedpeople. Disbursements from Samuel’s estate allowed the younger Townsends, both boys and girls, to attend Wilberforce University in southern Ohio; after fighting for the Union Army in Mississippi, one son took his inheritance to the Rocky Mountains, where he used it to start a business as a barber and engage in silver mining; other members of the family homesteaded on Kansas’s Great Plains, building new lives as farmers, teachers, journalists, and lawyers. Samuel’s son Thomas Townsend even returned to Alabama and purchased part of the old plantation where his family had been enslaved—the first time one of Samuel’s former slaves would own his former master’s land. Samuel Townsend’s estate was greatly devalued by the Civil War, but the surviving Townsend children would inherit around $5,000 each, more than $130,000 each in today’s currency. Though members of the family often faced prejudice in the communities where they made their homes, this capital gave the formerly enslaved Townsends room to pursue social and economic mobility in a hostile society.

Yet the fact that the Townsends had themselves once been enslaved didn’t make their inheritance any less problematic than if they had indeed been Samuel’s “white children.” The trust fund that the Townsends drew from throughout their lives had been built on enslaved labor—their own, their mothers’, and that of the nearly 200 other African Americans Samuel had held in bondage. When Samuel died and his property was put up for auction, his lawyer wrote that “the lands sold low” while “the negroes sold high,” meaning that most of the money the Townsends inherited came from the sale of other enslaved people, men and women without the dubious privilege of being their master’s children. Though it had radical implications for their future lives, perhaps the Townsends’ inheritance wasn’t all that radical of an act on Samuel’s part. Samuel Townsend hadn’t been motivated to emancipate his children by an abhorrence of slavery; he’d made his fortune on the backs of enslaved people. Samuel simply considered the enslaved Townsends superior to other African Americans, and therefore deserving of freedom, by merit of their blood relationship to him.

When Thomas Townsend purchased a piece of his father’s old plantation, it wasn’t an example of the large-scale land redistribution that freedpeople advocated after the Civil War. It was the transfer of wealth within one elite family, a centuries-old practice with consequences that reverberate into the present day. The descendants of white elites have had generations to build their wealth, in some cases wealth originally derived from slave labor. The descendants of enslaved people, who were largely denied land ownership during Reconstruction and excluded from economic advancement during Jim Crow, have not. It’s a form of opportunity theft that Ta-Nehisi Coates termed “the quiet plunder” in his 2014 article “The Case for Reparations.”

The Townsends’ story pushes us to imagine what America might look like if more enslaved people had benefited from the same sort of generational wealth that Samuel and Edmund’s children did, and that many white Americans still do today. If the promise of “forty acres and a mule” to former slaves had been honored by the federal government. If Thomas Townsend’s purchase of his father’s land in 1860s Alabama hadn’t been the exception, but the rule. Ultimately, the Townsends press us to ask a critical question for the present day: how do we make that imagined America a reality?

Featured photo by EVGENIY KONEV on Unsplash, public domain

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers