Oxford University Press's Blog, page 79

May 2, 2022

Social work in the anti-science era: how to build trust in science-based practice

Over the past five to seven years there has been an increase in anti-science rhetoric and ideas which look to replace the reliance on science with misleading theories and discredit scientific experts. Unfortunately, non-scientific beliefs gained traction during the pandemic and show no signs of slowing. This post-truth and anti-science movement places the field of social work at an important crossroads.

Social workers are expected to explain diagnoses and treatment options to clients and deliver services based on empirical research. Practitioners frequently need to challenge unhealthy behaviors and distorted beliefs which impede clients’ progress. At the mezzo level, we seek to change stereotypical beliefs and inaccuracies about diverse groups based on facts gleaned from research. In addition, social workers advocate for changes or additions in legislation based on findings from science.

But the current skepticism toward scientific research has become entwined with politics, angst, and anger. Many citizens and political leaders have taken a large step back from science and critical thinking because they are following political groups’ opinions of science and truth—or worse social media’s perspectives. Moreover, students are entering social work programs with few critical thinking skills, and an unhealthy distrust and resistance to science and research.

This isn’t a new problem for our field; understanding and using evidence-supported practices has long been debated and students often enter social work programs believing we do little else than use our instincts to “talk to people.”

“But if science isn’t ‘believed’ or valued, then what comes next for professions which are based on science?”

But if science isn’t “believed” or valued, then what comes next for professions which are based on science? Roles like physician, dentist, dietician, and social worker, that apply or practice science—by which I mean evidence-supported assessments and interventions—might not be needed. The field of social work could return to the days of being “friendly visitors” or be discarded for para-professionals.

So, what can be done when clients, students, and politicians are suspicious of and hostile to science, its findings, and the professionals who use it?

Social workers hold key positions in pivotal places to answer questions, educate, clarify, and return value to truth and science. The field of social work will need to make assertive efforts to address these anti-science sentiments and hone our tactics to assist clients, social work students, as well as the public in enhancing their understanding of science and research. Staying silent about anti-science beliefs is not an option, so let’s work together to counter the movement.

Seven strategies social workers can apply to build trust in science-based practiceRemove the veil that hides and mystifies the research process and scientific methods by openly and frequently explaining the process to students, clients, and the public. Discuss the dangers of not using research-supported treatment in service to clients and the benefits of using it. However, avoid arguments, trying to scare, or becoming emotional when you talk with someone who disbelieves science. Try to find common ground.Increase social work students’ critical thinking skills through skill-based activities that teach thinking fallacies and cognitive distortions throughout their curriculum.Re-envision BSW, MSW and Doctoral-level training regarding an emphasis on science and research. We can do this by increasing the number of research studies available, teaching empirically-supported interventions, and focusing on the evidence-based process throughout all programs.Train students, faculty, and social workers to communicate scientific findings clearly with jargon-free language to provide useful and practical public presentations of science (for example, TEDx events, radio, podcasts, YouTube videos, etc.). Give credit to academics for these public presentations towards tenure and promotion.Social work professionals need to stay up-to-date on current theories, assessment, intervention, policies, diversity, and social problems, reading empirical findings and utilizing evidence-supported practices. They need open access and reasonably priced resources.Keep an open-mind to the constant changes in knowledge coming forth via research and recognize that science isn’t free of errors, bias, and/or limitations.Silence and time are not our allies in this struggle, post-truth and anti-science rhetoric are gaining momentum and impact our work and our profession. If the public and clients don’t value science; they won’t value a science-based profession like ours. We can strategically act to re-build trust in science and value in truth. But we will need to work collaboratively, use effective tactics and take action now.

Featured image by Mario Purisic on Unsplash (public domain).

April 28, 2022

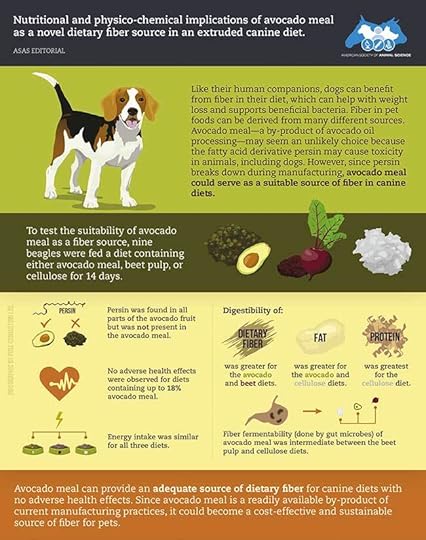

How avocados may boost dog health [infographic]

Like all of us, dogs need fiber. In fact, canines will seek it out, and it’s no shock to see a dog gnawing on a carrot or crunching down apple-based treats. A high-fiber diet also helps dogs lose weight and maintain a healthy gut microbiome.

In a new Journal of Animal Science study, researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign report that avocado meal, a readily available by-product of avocado oil processing, can boost the fiber content of dog food without leading to health issues.

Beagles in the 14-day experiment were given diets with either avocado meal, beet pulp, or cellulose as a fiber source. Although the cellulose diet was higher in protein, the researchers found that the avocado meal made for a good fiber, fat, and energy source. They also confirmed that gut microbes are able to effectively break down the fiber in avocado meal.

Importantly, the researchers put to rest the fear that avocado meal may contain a harmful fatty acid derivative called persin. Their analysis shows while persin is present in all parts of the avocado, the act of processing breaks down persin—so no persin ends up in avocado meal.

Looking forward, the animal scientists think a diet containing up to 18% avocado meal may be a good option for dogs—and further studies will show if other pets could benefit too.

Explore the infographic to learn more:

Related articles

Related articlesTake a further look into this topic with related articles from the Journal of Animal Science:

“Weight loss and high-protein, high-fiber diet consumption impact blood metabolite profiles, body composition, voluntary physical activity, fecal microbiota, and fecal metabolites of adult dogs“Thunyaporn Phungviwatnikul, Anne H Lee, Sara E Belchik, Jan S Suchodolski, Kelly S Swanson, Journal of Animal Science, Volume 100, Issue 2, February 2022, skab379 “Organic matter disappearance and production of short- and branched-chain fatty acids from selected fiber sources used in pet foods by a canine in vitro fermentation model“

Renan A Donadelli, Evan C Titgemeyer, Charles G Aldrich, Journal of Animal Science, Volume 97, Issue 11, November 2019, Pages 4532–4539

Featured image via Pixabay (public domain)

April 27, 2022

On being lazy, loose, empty, and idle

Some of the most common words appeared in English late. Yet their origin is obscure. Of course, while dealing with old words, we also encounter unexpected solutions. Consider the adjective empty. Those who have studied Latin will remember that the supine of emo “to sell” (or “to bribe,” that is, “to buy”!) is emptum. Someone may say: “Oh, empty meant ‘sold out’ or ‘no longer in existence’”! Alas, no, though it is a good guess. It is good because in both English and Latin, the sound p is a “parasite,” an excrescent product of assimilation. Something, occasionally pronounced as sompthing, provides a clue to the nature of this insertion. Likewise, Simpson and Thompson are illegitimate children of Simson and Tomson. Those interested in other words with inserted consonants may also consider gambler (from game!), kindred (from kin!), and sumptuous, whose Latin source underwent a similar change. Thus, no: empty is not a borrowing from Latin.

Empty goes back to Old English ǣmetta “leisure,” that is, to the hours of idleness. (Hours of Idleness was the title of Byron’s first book of poetry, published in 1807.) In the ancient (reconstructed) noun ā-mōt-iþa, ā must have been a negative prefix, mōt a noun meaning “meeting,” and the rest was a suffix. Moot in a moot point is related to that mōt, though “arguable, fit for a debate at a meeting,” rather than “empty.”

Emptiness and freedom loom large in the etymology of loose. The form of the adjective was destined to become leese, but the Old English word lēas gave way to its Scandinavian doublet lauss, which, among other things, also meant “empty.” This kind of substitution happened not too seldom. After the Vikings conquered two thirds of England, language mixture and, to use the phrase of the famous historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, an amalgamation of races became common. A cognate of this root is known to all of us as the suffix –less (German –los). But the German adjective leer “empty,” deceptively similar to the words being discussed here, goes back to another source. It is probably related to the Germanic verb meaning “to collect, pick out,” often in connection with harvesting. Hence also the German verb lesen “to read” and the punning title of books like Lesefrüchte “The fruits of reading and of the harvest.” A similar pun is used in Dutch titles. (Reading presupposes literacy, but the verbs read, lesen, and their synonyms elsewhere were coined long before people began to use letters. “To read” meant approximately “to advise,” while lesen referred to some sort of collecting.)

An empty threat.

An empty threat.(Photo by Scochran4 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0 US)

German ledig “free” (today also and mainly “unmarried”) also seems to have developed from “empty.” Whenever we encounter words of this group, we notice that “empty” and “free; unbound” go together. Ledig, it has been suggested, is related to German Glied “limb; member.” G- in Glied is a remnant of an old prefix. The whole may have meant “easily movable,” because this is exactly what Old Icelandic liðugr “unrestricted” means (ð has the value of th in English the). This idea will come in useful at the end of our today’s investigation.

English lazy is one of many late words of unclear origin. It turned up only in the sixteenth century and has counterparts all over northern German dialects (that is, in Low German). The meanings are the same everywhere (“idle, languid,” and so forth). Walter W. Skeat referred lazy to loose, mentioned above in connection with Scandinavian lauss. The vowels match badly. The corresponding Dutch verb had eu in the root. But this word may have been slang, a term of (mild) abuse, and as such perhaps existed in several forms, a common case in unbuttoned speech. This is, unfortunately, guesswork, but the proximity of lazy to some of the words mentioned above is rather obvious.

Vikings in England, new words and all.

Vikings in England, new words and all.(“The Barbarians Invade England”, Life of St Edmund, via Store Norske Leksikon, public domain.)

I may now add that the great German philologist Friedrich Kluge believed that lazy is a borrowing of Latin lassus “tired, weary, exhausted.” Kluge was an outstanding expert in the area of German etymology and all things Germanic. Quite naturally, while discussing German words, he often encountered their English cognates. In 1899, a slim book titled English Etymology appeared under the names of Friedrich Kluge and Frederick Lutz. As far as I can judge, the book was written by Kluge and only translated into English by Lutz, about whom I could not find any information. Though the book is now in open access, I never see references to it. Kluge is too important a figure to be ignored. I doubt that his hypothesis has value (a solid etymology of lazy should account for the origin of its Low German lookalikes), and yet referring to it will harm no one. Anyway, lazy does not look like a bookish word.

Another obscure adjective is idle. A thirteenth-century word, it emerged with the sense “empty” among a few others. This adjective has related forms all over West Germanic (that is, in Frisian, Dutch, German, and Old Saxon). Their senses are: “lazy; thin; bare.” In Modern German, eitel means “mere; worthless; vain;” and Dutch ijdel is rather “vain; useless; frivolous.” Most probably, the non-figurative meaning “empty” underlies the figurative ones. Modern dictionaries have nothing to say about the word’s origin. A rather uninspiring game consists in attempts to find some ancient root to which an opaque word can be traced. In the not too remote past, idh– “to burn,” was chosen as such a putative root, with the development from “burning” to “appearing.” A less convincing hypothesis would be hard to imagine.

Indo-European ei “to go” perhaps holds out greater promise. Since idleness and emptiness seem to refer to the idea of being unrestricted, moving freely, the connection looks rather reasonable, except that the process of selecting ancient roots as candidates for the etymons of modern words is always a precarious venture. Greek itamós “bold, impetuous” and Lithuanian eiklùs “quick, precipitous” are supposed to go back to this root. Idle may perhaps be related to them. There was also an uninspiring attempt to connect idle and Greek itharós “pure, clear.” A curious look-alike is Hittite idalu-s “bad, angry,” but when a certain word has been recorded only in part of Germanic and a remote Indo-European language, one cannot help wondering why it did not turn up anywhere in the intervening regions.

An idling motor is not idle.

An idling motor is not idle.(Photo by J Torres on Unsplash, public domain.)

We should probably leave the etymological motor idling and step aside to examine the results of our wanderings. Words like loose and idle may go back to the adjectives referring to unrestricted movements or freedom from restraint. Viewed in this light, our attempts have not been quite futile. English lazy and idle will remain adjectives of unknown or uncertain origin because it is unclear what should be done to discover their sources. Yet the suggested etymology of empty looks promising. The scholars who offered their musings on the origin of idle are the American historical linguist Francis A. Wood, a prominent member of the once illustrious Chicago philological school, and the Dutch linguist Nicolaas van Wijk, an outstanding specialist in Slavic, Baltic, and Indo-European linguistics. Outside the profession, their names mean nothing, which is a pity, considering how many unnecessary names everybody remembers and how beneficial it is to know the origin of the words we use.

Featured image by Konstantin Evdokimov on Unsplash (public domain)

April 25, 2022

The role of DNA research in society [podcast]

Since its discovery in 1953, DNA has revolutionized our world in many ways. From medical research to paternity tests to solving crimes, thanks to DNA, we now have a better understanding of who we are, how we have developed, and how we can heal.

For today’s episode of The Oxford Comment, we’re commemorating National DNA Day in the United States by considering the role that DNA plays in our society. First, we welcome Amber Hartman Scholz, co-author of the article “Myth-busting the provider-user relationship for digital sequence information”, looking at how genetic resources are actually used and shared across the globe. We discuss the surprising findings of this research as well as the important implications for policy makers. We then interview Dee Denver, the author of The Dharma in DNA: Insights at the Intersection of Biology and Buddhism, to talk about the significance of DNA research and what the lay person should know about the uses and findings of DNA. We also talk about another aspect that is much less well known: the role that DNA plays at the intersection of spirituality and science. Underlying both interviews is the question of open science and why it matters, specifically, for DNA research.

Check out Episode 71 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · The Role of DNA Research in Society – Episode 71 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingAmber Hartman Scholz’s aforementioned GigaScience article can be found here. For further context on the provider-user relationship for digital sequence information, please see the companion article “Quantitative monitoring of nucleotide sequence data from genetic resources in context of their citation in the scientific literature“.

To learn more about Dee Denver’s work, please enjoy Chapter 1: Water from The Dharma in DNA. He is also the author of numerous journal articles, such as “Sex and Mitonuclear Adaptation in Experimental Caenorhabditis elegans Populations” in Genetics and “Adaptive Evolution under Extreme Genetic Drift in Oxidatively Stressed Caenorhabditis elegans” and “Comparative genomics of a plant-parasitic nematode endosymbiont suggest a role in nutritional symbiosis” in Genome Biology and Evolution.

Featured image: @rabbit_in_blue, CC0 via Unsplash.

April 23, 2022

Rough Walkers: the true story of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders

Theodore Roosevelt will no longer lord over the entrance of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. The statue of Roosevelt, on horseback, flanked by an indigenous person and man of African origin, both on foot, was removed recently. Calls for its removal cited that its hierarchical depiction of the three represented societal white dominance. A competing viewpoint by supporters of retaining the statue claimed the statue showed Roosevelt leading minorities forward.

This is not the forum for settling that argument. The statue has been removed.

The depiction of Roosevelt on horseback, however, reinforces the historical image that many Americans grew up with, that of the leader of the “Rough Riders” in the Spanish-American War of 1898.

American schoolchildren learn about the charge up San Juan Hill in the Battle for the San Juan Heights, leading to victory in that brief war. The mental image, sometimes supplemented by creative artwork, is one of the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, nicknamed the “Rough Riders,” racing uphill on horseback and vanquishing the defending army.

Not true. At least not the main parts of the story.

Certainly, the members of the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry had been selected for their ability to ride, and they had been trained to shoot from the saddle. Many were cowboys and other outdoorsmen recruited from the hot, dry American southwest. In May 1898, more than 1,000 of them and an even larger number of horses and mules shipped to Tampa, Florida, where they were to set sail for Cuba. Due to a variety of issues, including illness from malaria, yellow fever, and typhoid fever, the troop numbers were greatly reduced. Compounding those losses, other miscues by the Army resulted in only a fraction of the number of troops and very few horses and mules to make the trip aboard the steamship Yucatan.

When they landed at Cuba, the “Rough Riders” became the “Rough Walkers.”

The cavalry men were accustomed to carrying their supplies on horseback or by mule train. Having neither, they had to make long marches, in the heat and humidity—very unlike the dry American southwest—and carry their own weapons, munitions, and inadequate food. They were ill-prepared for this turn of events.

Fighting in the heavy jungle in the run-up Battle of Las Guasimas would have precluded the cavalry from fighting on horseback, anyway. But the thick jungle, steep terrain, and hot, humid conditions also led to many unprepared cavalry-turned-infantry troops into quitting the battle. Still, the remainder, bolstered by the larger number of Buffalo Soldiers from the 10th US Regular Cavalry, fought their way uphill and led the Spanish army to withdraw.

For the next six days, the Rough Riders rested, refreshed, took care of the wounded, and buried the dead. During that week-long lull before the two sides would meet again in the San Juan Heights, an unvanquished enemy stole its way into the American camps. That same, non-partisan enemy also visited the Spanish encampments. This enemy would prove more difficult to fight, impervious to the American troops’ Springfield Krag carbines or the 7mm rifles of the Spanish.

Mosquitoes. Armed with weapons that outgunned the troops, American and Spanish alike—yellow fever and malaria. Not ones to choose sides, the mosquitoes equally attacked troops of both armies. By some accounts, more than 16,000 Spanish troops had already fallen before the first bullet had been fired; their war against yellow fever and malaria was already being fought before the invasion by American troops.

The battles in the San Juan Heights, first at Kettle Hill, followed by the brief Battle of San Juan Hill, were largely over open terrain. The cavalry troops could have made their charge on horseback, but they were now Rough Walkers, with the only horse being that of Lt. Col. Roosevelt. The lone Rough Rider.

The victory at the San Juan Heights, followed by victory at Santiago and defeat of the Spanish Navy in Santiago Bay, made the short war even shorter. Battle casualties were few. Well, battle casualties from Spanish weapons were few, but battle casualties were not. Only about 10% of the 3,000 US casualties were from battle weapons, the vast share of the remainder due to yellow fever and malaria, carried by mosquitoes.

Surviving Rough Riders returned to the US, not to Florida, but to eastern Long Island, New York. There, convalescence brought them back to health. Isolation on Montauk Point was intentional to try to prevent the troops from bringing back yellow fever and spreading it among the civilian population, because, despite the all-too-real knowledge of yellow fever’s mortality, the vector, the mosquito Aedes aegypti, was still not associated with the disease. It would take other heroes fighting in the heat and humidity of Cuba to win that battle—none of them remembered by statues, none of them on horseback.

Feature image by Ian Sane, via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

April 22, 2022

The problem with self-driving cars is not technology, the problem is people

The prospect of autonomous cars in aiding, even replacing, human drivers, is exciting. Advertised benefits include reduced commuter stress and improved traffic flow. The prospect is also alarming. The growing number of accidents involving self-driving technology tests the risk appetites of even the most enthusiastic adopters. The challenges are real. Uber, an early adopter of self-driving car technology, recently abandoned its ambitions of full autonomy. The recent $2.5 billion fine against Boeing due to the 737 Max disaster exposes the underlying vulnerabilities associated with the introduction of technology.

There has been ample review of the underlying technology, but there are far too few discussions about the role of people. What happens when we replace human judgment with technology, a situation that psychologists call “cognitive offloading”? Cognitive offloading has become more common with the introduction of new technologies. Do you rely on your phone to store phone numbers you once memorized? Do you use GPS navigation instead of memorizing your driving routes? Then you know the benefits of cognitive offloading. Cognitive offloading transfers routine tasks to algorithms and robots and frees up your busy mind to deal with more important activities.

In an upcoming edition of the peer reviewed journal, Human Performance in Extreme Environments, I review the unintended consequences of cognitive offloading in industries like aviation and aerospace. Despite its many benefits, cognitive offloading also introduces a new set of problems. When we offload activities, we also offload learning and judgment. In one study, researchers asked a group of subjects to navigate the streets of London using their own judgment. A second group relied on GPS technology as their guide. The GPS group saw significantly less activity in the brain associated with learning and judgment. In the instance of self-driving cars, drivers may see their driving skills degrade over time.

Two primary deficits can accompany cognitive offloading. First, cognitive offloading can lead to forgetfulness or failure to learn even basic operating procedures. The problem becomes acute when equipment fails, when the weather is harsh, and when unexpected situations arise. In aviation, even carefully selected and highly trained pilots can experience these deficits. Pilots failed to perform basic tasks in the Air France 447 disaster. An airspeed sensor failed, and autopilot disengaged. The pilots were now in control of the plane but had never learned, or forgot, how to regain control of the aircraft as it quickly descended into disaster.

Second, cognitive offloading also leads people to overestimate the value of offloading, and this can lead to overconfidence. People may fail to grasp how offloading may degrade their abilities or how it may encourage them to apply new technologies in unintended ways. The result can be consequential. The Boeing 737 Max incidents were attributed, in part, to overconfidence in the technology. One pilot even celebrated that the new technology was so advanced, he could learn to master the newly equipped aircraft by training on a tablet computer. But the technology and engineering proved to be far more complicated to operate. This same type of overconfidence has led to accidents in self-driving cars. Some drivers of self-driving cars have slept at the wheel and others have left their seat completely, despite warnings that the driver should always be aware and engaged when in autodriving mode.

“When we offload activities, we also offload learning and judgment.”

Commercial aviation offers lessons for ways to address these deficits. Technological innovation has fueled remarkable gains in safety. The fatality rate in commercial airlines has been cut in half over the last decade. Importantly, implementation of new technology goes hand in hand with extensive training in human factors. Human factors consider the limitations of human decision making, motor skills, and attention. The safe implementation of new technologies requires extensive training and constant updating that helps pilots understand the limits of the technology.

Proposed solutions to the human factor problem in self-driving cars are promising but have yet to reach an acceptable level of transparency. Tesla’s Safety Score Beta, for example, monitors the driving habits of Tesla owners and only activates the self-driving feature for drivers who meet their criteria on five factors: number of forward collision warnings, hard breaking, aggressive turning, unsafe following, and forced autopilot engagement. But much of the data lacks transparency, there is no ongoing training, and there is growing discontent among drivers who fail to make the safety cut after shelling out nearly $10,000 for the self-driving feature.

The widespread adoption of self-driving cars will require more than just technology. Extensive human support systems such as oversight and reporting, training, and attention to human limitations must also be addressed. The ultimate success of self-driving cars will depend on improving technology, but also on educating the drivers behind the wheel.

April 20, 2022

From the ridiculous to the sublime: from “monkey” to “elephant”

Animal names are a familiar topic in this blog, and more than once have we seen how hard it is to discover the origin of even such simple words as bunny, dog, cob, calf, and their likes. Only bow-wow and oink–oink pose few or no problems. Some names seem to be baby words, others are loans from distant languages, and more often than not we have to admit that their ultimate sources remain a matter of uncertainty. Excellent books and articles have been written about the etymology of animal names. Among my favorites are the outdated but invariably inspiring ones by August Pott (1802-1887), an almost supernaturally prolific scholar. By the way, it was he who showed that, contrary to what everybody says, dog has cognates outside English. Recently I have reread his essay on the word elephant and decided to write something about this word. I have nothing original to say about it and depend on two works: an excellent book in Italian and a detailed essay in English. Not everybody may have read them; hence my inroad on this convoluted problem.

A few things are not controversial. Elephant reached Middle English in the thirteenth century from France in the form olifa(u)nt. In Dutch, the form olifant has stayed, while in English only the Oliphant family points to that variant of the word’s French ancestry. The circumstances that led to the rise of the ancient but odd surname Oliphant are not known. I lost interest in the origin of such names long ago, after I ran into a mention of Mr Heifer. Not improbably, Oliphant is a folk etymological reshaping of Oliphard and thus has no relation to “a huge pachydermatous quadruped with a trunk,” as some dictionaries define elephant.

One thing is clear: the name of the elephant became known to the West Europeans before they ever saw that quadruped. Alas, Europeans have always been interested in ivory, rather than in the animal and succeeded in bringing that noble beast to the brink of extinction. “Hathi never does anything till the time comes, and that is one of the reasons why he lives so long.” Etymologists should certainly heed this habit. Hathi, you will remember was the wise elephant in The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling. And you may have read Kipling’s Just So Story about how the elephant got its trunk.

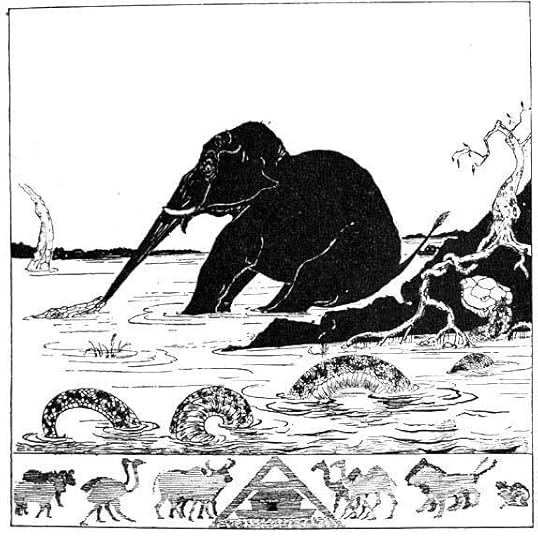

This is how the elephant got its nose, but nothing is said about the tusks.

This is how the elephant got its nose, but nothing is said about the tusks.(Illustration for Rudyard Kipling’s “The Elephant’s Child” in Just So Stories, p. 63. 1926. Scanned image by George P. Landow via Victorian Web.)

In Homer, eléphâs means “ivory”; “elephant” is a later sense of this word in Greek. From Greek the word spread to Latin, and from Latin to the rest of Western Europe. Other people have other names for this animal, such as Russian slon. It is the ultimate source of the Greek word that constitutes the problem, but there are other complications. For example, in the fourth-century translation of the New Testament from Greek into Gothic, a Germanic language, the word ulbandus occurs. It is reminiscent of the Greek name for the elephant, but it means “camel”! Ulbandus occurs in the familiar verse: “For it is easier for a camel to go through a needle’s eye, than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God” (RV, L 18. 25). Bishop Wulfila, the translator into Gothic,came across Greek kámelos and, apparently, knew its equivalent in his native language, regardless of whether he had ever seen a camel. The resulting confusion is typical of the names of large exotic animals: for instance, here elephant, there camel. In similar fashion, the above-mentioned Russian noun slon “elephant” is probably an alteration of Turkic arslan “lion.” (This word for the lion yielded the name of the hero Ruslan; stress on the second syllable.) Slavic speakers knew as little about lions and elephants as did the Goths. Most researchers believe that ulbandus and elephant are variants of the same word, and there is good reason to share this belief. Anyway, ulbandus traveled peacefully to the eastern Slavs and became vel’bliud ~ verbliud “camel” in Ukrainian and Russian.

Ruslan in full glory.

Ruslan in full glory.(By Nikolai Ge via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

There are two ways to look at the origin of the word elephant. Since, in the remote past, it was not the animal but the ivory that interested those who coined the word, it may be that the root of elephant is the same as that of ivory. Now, ivory goes back, ultimately, to Latin ebur (the same meaning), related to Egyptian ābu and especially Coptic ebou ~ ebu, which meant both “elephant” and “ivory.” The Coptic language represents the final stage of Ancient Egyptian. Conversely, there are many words in Indo-European with the root el– “horn,” as in English elk. Elephants do not have horns, but the same root does occur in the word for “tusk” in several old languages. Worthy of note are also the attempts to connect elephant with Luwian lahpa “ivory” and Hittite lahma “? elephant.” (Both Hittite and Luwian are ancient, now dead Indo-European languages of the Anatolian group; my transcriptions have been simplified.)

Are you sure it is an elephant?

Are you sure it is an elephant?(Photo by Megan Schultz on Unsplash, public domain)

Outside Indo-European, the Semitic root ‘alp “ox” has been discussed since the seventeenth century as a possible source of elephant. August Pott traced elephant to the phrase aleph Hindi “Indian ox.” But perhaps el- in elephant is an Arabic article! The rest of the word would then mean “ivory” and the whole word “the ivory.” For the record: the Copts called the elephant and ivory eb(o)u, and the Sanskrit word for “elephant” is íbhas. The Hebrew form shenhabbim is not too far away either, but perhaps this word was an alteration of the phrase shēn-hābrum “ivory and ebony.” What a lot of clues and of very intelligent guessing! We are undoubtedly dealing with a migrant word.

Obviously, the origin of elephant remains undiscovered (or we may say, no derivation has been recognized as definitive), partly, as pointed out above, because the word became known long before the Europeans saw the animal for the first time. Yet the confusion or the union of the words for “elephant” and “ivory” in at least some languages is certain. Though the word may have an ascertainable Indo-European root, all the existing hypotheses in this direction are shaky. Nor are the attempts to trace elephant to some North African language fully convincing, even if the non-Indo-European source of our word is probable.

The list of the etymologists who over the centuries have dealt with the elephant looks like WHO IS WHO IN HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS. In it we find, among many others, Adolphe Pictet, August Pott, Max Müller, Ferdinand de Saussure, Paul Kretschmer, Jaan Puhvel, and Viacheslav Ivanov. You may never have heard those names. The reason is that etymologists are not famous public figures. Ecstatic fans do not shower them with flowers, and their salaries are modest. They usually teach at colleges and universities and prevent our culture from falling into desuetude. Also, following Hathi’s example, they work slowly (eat an elephant one bite at a time, as it were).

A celebration of an etymological discovery?

A celebration of an etymological discovery?(Photo by Hayley Seibel on Unsplash, public domain)

Featured image by Craig Stevenson on Unsplash (public domain)

April 18, 2022

Dance “crazes” and plagues: a precedented phenomenon

Lockdown raves, dodging people in the street, no more hugs, then hugs, then no more hugs, then hugs; confinement within the home worthy of house arrest—and the language of self-isolation, shelter, safety… all the makings of a sci-fi horror film depicting the world at an end. Or a history book, which is what this pandemic has felt like to me at times, having spent well over a decade thinking about historical epidemiology, specifically in relation to ideas about dance.

What came in the nineteenth century to be known as the “Black Death,” or bubonic plague, decimated somewhere between a third and half of the population of most towns and villages, cities and countrysides in the middle decades of the fourteenth century. It returned in bouts for centuries afterwards. At the same time, people, it seemed, were dancing; this gaiety in turn drew the attention of moralists who thought no one should be doing anything of the sort. Sometimes, these dancing people were travelling pilgrims, as I realised, digging through the archives of this medieval lore. Sometimes, they were hippie-like characters who wore wreaths in their hair and hung out in makeshift campsites outside town. By the time these stories came through to nineteenth-century colonial eyes, this started to look like what was being observed of rebellions—often dancing, sometimes no—all over the colonial world. In Madagascar, people were “possessed” by the dead queen, Ranavalona I, who was being called upon to help depose her puppet son; this too was described in medical literature as a dancing “plague” or epidemic. And yet as I realised, looking into this further, this actually constituted a perfectly legitimated form of governmental riposte. And the examples proliferate.

What today’s choreographies of gathering and distanciation show is that far from being “unprecedented,” today’s times, as it were, have a long history of precedent in ways of moving and ways moving bodies have been imagined or understood. Disorderly bodies—those that appear not to adhere to rules of good conduct—tend to be likened to the diseased, the contagious; tend to be seen as “contagious” themselves. At the same time, as we know well now after two years of pandemic life, quarantine has long been a proven measure of bringing infections down. During times of severe contagion that risk compromising the most vulnerable people’s health and lives, and in effect make everyone far more vulnerable than would be the case in more “normal” times, we shift our choreographies, shift our ways of understanding what is a convivial way of moving or what is right; shift also ways we see the present moment.

What I like to think of as the feeling of historicity describes this feeling of finding something uncanny, or comfortable, in the sense that the experiences of the present will be gotten through… that something not unlike this has been lived through before. Or, and these are not mutually exclusive, that something might radically change—a hope many have nurtured, especially in the early days of the current pandemic, in thinking that perhaps relationships to work, to family, or to climate, will finally transform. The feeling of historicity—perhaps the converse to the sense of these times being “unprecedented”—allows for a measure of proximity to other people, places, and times. “Crisis” becomes relativized.

“What today’s choreographies of gathering and distanciation show is that far from being ‘unprecedented,’ today’s times have a long history of precedent in ways of moving and ways moving bodies have been imagined or understood.”

Of course, the crisis is also very real, and felt presently, no matter how “precedented” it may be in some ways. A lot of what takes place is release from pent-up tension and strain: dance “crazes” sweeping TikTok or Instagram play—unwittingly, perhaps—on a very old trope, the expression of convivial energetic release and even “madness” of a sort, that comes with being cooped up for too long. In a great “case” of so-called “dance madness” or epidemic contagion I read about in the eighteenth-century Shetland Islands, some people were more or less climbing the walls with “cabin fever”; other “cases” in the Middle Ages involve girls and boys bored in church being told to go outside and dance forever, to their deaths. Many stories came of this sort of lore: familiar today includes Hans Christian Andersen’s moralizing version in his story of the “red shoes”—too much fixation on worldly things will drive one mad. The Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell film remake of The Red Shoes in 1948 featured a young woman (Vicky Page, played by Moira Shearer) who was so obsessed with dancing she eventually drove herself to insanity and ultimately death. Many different moralizing perspectives can be drawn from this, including, as I see it, a relationship to over-commitment or overzealousness with work, to institutional pressure (her dancing master is a slave-driver of a sort, and she is driven by her own passion, but also spurred on by this culture of “better, more” to the point that it harms).

With crowd gatherings mimicking madness, or with the many remakes of “mad” dance scenes filmed at home or in studios during lockdown, the desire for embodying “madness” seems never to have been so strong. What these moments teach us, and what I was able to explore in my book well before the current pandemic hit, was how the figure of dancing epidemics, or contagious dance, or dance madness are nothing if not enduring, and often accompany xenophobic or sexist prejudice associated with bodies apparently in disarray. Just as true is the fact that “madness” as such is at best a very volatile affair, often composed of a highly serious wish to let loose and “go a bit crazy,” together with a sense one has genuinely a bit of a screw loose. To dance quite literally allows for stomping out some of the tension, laughing, bonding with those around one, and opening up the chest or neck, among other basic physical or physiological things. Nothing is very “mad” about that, though to talk of this as madness or as a craze translates depreciatively in hindsight—only if we take this dancing too literally as an expression of entire populations or groups being “sick.” On the contrary, it is wellness they’re seeking and expressing, and this wellness is of course, when the world has gone a bit bonkers—when it has become unrecognisable, one has lost one’s coordinates, one is confused and unmoored—comprised of a solid portion of humour, joy, and sheer reprieve.

This does not for a moment downplay the seriousness of actually contagious illness; doctors dancing for their patients in covid wards, in videos that have themselves gone viral, know this well. The two go hand in hand: when tensions rise, so does the need to assuage them. The challenge today is to do this nevertheless safely—to legalise gatherings so safety measures can be put into place, for example, as municipal authorities did in Strasbourg in the early 16th century, in an “episode” of dancing that has been grossly sensationalized, rather than to drive gatherings far underground. Across from my flat in London, enormous crowds gathered while clubs were closed. This was outdoors, in park space. Not an ideal measure given spread takes place even in open air; but the energy gathered kept some people going for a while. As I discovered writing my book, there is, as I’ve also noted here, nothing “manic” or “contagious” about this; but there is a long history of judgment, demonization in some cases, and medicalization from the sidelines—the sense that these young people should shut up and keep still (that their dancing itself was a plague). These are survival mechanisms of a sort, on a global level as well as on a local one. Survival comes in many forms, most of them, in the case of pandemic conditions, involving distance and masking, sanitation and further precautions; at the same time, if what we’re looking at is the history of underground culture and of rebellion, it is important, I think, to realise is that the need to dance, or the feeling of needing to join together with others in a release of energy which produces more energy in turn, has come at times with criminalization. For Native American Ghost Dancers in the 1890s, dancing in the face of genocidal conditions brought a sense of gathering and so collective force, even though crops and land were decimated through governmental treaty abuse. The dancing becomes a cipher for other tensions and culture wars, for other forces of judgment about who is allowed to move, why, when, and where.

April 15, 2022

The Bible and American history

The recent American presidency illustrates why Scripture has been both a polarizing and a constructive force in the nation’s history. On 1 June 2020, Donald Trump made an overtly political point when he cleared peaceful demonstrators from Lafayette Square, who were protesting police violence against unarmed Black men, so that he could pose for a photograph clutching the Bible in front of a church near the White House.

A different motive inspired George W. Bush when on 1 February 2003, he quoted from the biblical prophet Isaiah to memorialize the astronauts killed when the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated on reentry into Earth’s atmosphere: “Lift your eyes and look to the heavens. Who created all these? He who brings the starry hosts one by one and calls them each by name.” The president went on, “The same Creator who names the stars also knows the names of the seven souls we mourn today.”

Similarly, on 26 June 2015, Barack Obama began his eulogy for Clementa Pinckney, a Charleston pastor and legislator murdered by a white supremist during a prayer meeting at his own church, by reading from the eleventh chapter of the New Testament book of Hebrews: “They were still living by faith when they died.” His eulogy, which ended with the president leading the assembled throng in singing “Amazing Grace,” drew on generations of African American sermons to remind listeners that only “the power of God’s grace” could transform tides of violence into healing for individuals and hope for the nation.

The history behind these presidential moments explains the United States’ enduring, though anything but simple, engagement with the Bible. When the colonists broke from Britain, they threw off European Christendom, especially the tight interweaving of church and state. Yet America’s overwhelmingly Protestant population not only remained loyal to the King James Bible inherited from Protestant Britain, they energized that attachment by fusing it with the principles of American democracy.

“How else could a democracy with no monarchy, state church, or powerful universities sustain the personal virtue without which republics failed?”

When in the 1790s Tom Paine, a hero of the Revolution, published an incendiary attack on Scripture, Jeffersonian populists and Federalist conservatives set aside their deep differences to mount an all-out defense. Through the next generation, energetic Baptists and Methodists relied on “the Bible alone” to spark a remarkable Christianization of the population (church adherence rose much more rapidly than the remarkably swift rise of the population). More staid churchmen, joined by a growing number of active church women, used voluntary means to create American civil society. In its efforts to make the Scriptures available to all citizens, the American Bible Society (1816) pioneered mass publishing and national distribution of print. In New York, Massachusetts, and Ohio, reformers eager to create schools serving the entire population agreed that students should read from the King James Version every day. How else could a democracy with no monarchy, state church, or powerful universities sustain the personal virtue without which republics failed?

Soon, however, Protestant hopes for a free and democratic Bible civilization faltered. When the rising number of Catholic citizens rejected Protestant impositions, like mandatory reading of the Protestant Bible in tax-supported schools, the contest began over the place of religion in public life that has never ceased. Jews, Protestants not of British background, citizens wanting no truck with religion, and eventually adherents of many world religions have kept that particular pot on boil.

Even more, early Protestant hopes for a Bible civilization collapsed because Protestant Bible believers disagreed so strenuously among themselves. Although some of their disputes reprised older European debates, fundamental differences over the Bible and slavery did the most to destroy those hopes. By brandishing Scripture to defend (or attack) the American slave system, white Protestants made the Civil War almost as much a religious war as a conflict over sovereignty and basic human rights.

Even as they did so, free Blacks and an array of enslaved African Americans were reading the Bible for themselves. While reformers like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth inspired Black Americans, they were little noticed at the time. Yet their conviction that Scripture treated physical liberation and spiritual liberation as indivisible would one day contribute to the postwar Civil Rights Movement that rivetted the nation’s attention.

“The Bible that has done so much to shape American history is in turn a book thoroughly shaped by that history.”

If the Bible civilization of the early republic’s Protestants did not last long, the Bible certainly remained a national fixture. Abraham Lincoln quoted it strategically in his incomparable Second Inaugural Address. Robert Ingersoll became a celebrity by subjecting it to ridicule. Frances Willard of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union stood by it as resolutely as Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Woman’s Bible questioned its hold. Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Jennings Bryan mastered its vocabulary to promote their differing versions of American civil religion. And so it continues into the twenty-first century of Bush, Obama, and Trump.

Scripture obviously remains central for weekly observances in churches and synagogues, as in the private lives of countless families and individuals. But even these realms are touched by a history as rich as it is complex—where Bible believers have fed the hungry, educated the unlettered, protected the unprotected, and hammered at the chains of physical bondage. But also, where they have forged the chains of physical bondage, sanctioned partisanship, defended privilege, and exploited racial difference. The Bible that has done so much to shape American history is in turn a book thoroughly shaped by that history.

Featured image by Aaron Burden on Unsplash. Public domain.

April 14, 2022

Electric vehicles: a shift in the resource landscape for the transportation market

The massive US and worldwide transportation sector are fueled mostly by crude oil. Although ethanol and compressed natural gas (CNG) have grown to 6% and 2%, respectively of the US total, gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel account for more than 90% with very little from electric vehicles (EVs) using electricity or fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) using hydrogen. Before the worldwide pandemic, worldwide crude oil consumption was more than 100 million barrels per day (MM BPD), and the US consumed 20.5 MM BPD, with 9.3 MM BPD of gasoline and 3.0 MM BPD of diesel. These fuels support a vehicle market of 278 million serving a population of 331 million. Worldwide, the number of vehicles exceeds one billion.

The original founding members of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries), including Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela, currently control 58% of the worldwide crude oil reserves, estimated to be about 1.7 trillion barrels. Canada is also a large player, controlling 10% of worldwide reserves but the US has less than 3%.

Therefore, at this time the critical resource for the transportation industry is crude oil, the energy source needed to power vehicles. This could change, however, as some parts of the world move away from fossil fuel driven vehicles and towards battery electric vehicles (BEV). For example, the European Union is targeting at least 30 million zero-emission vehicles on its roads by 2030. Also, China, currently the world’s largest auto market, plans to have BEVs make up 20% of new car sales by 2025 and 50% by 2035. In addition, even if there was no growing trend to move away from fossil fuels, proven reserves and worldwide consumption for crude oil suggest we have enough left for 47 years. Certainly, this number could decrease if developing countries increase consumption, or increase if more reserves are discovered from deep-water oil and fracking technologies. Nevertheless, these factors would increase crude oil production costs and potentially shift the market towards BEVs.

If the world moves to a transportation market dominated by BEVs, the big change is that the key resource will shift from an energy source (i.e., crude oil) to the metal resources needed to make batteries. Certainly, energy in the form of electricity will still be needed but a rough estimate shows the entire 278 million US vehicle fleet would represent 25% of the amount of electricity currently generated. The transition would be slow, and the basic infrastructure of electric plants and electric grid already exist, so the main infrastructure needed would be charging stations.

How does a battery work?A detailed discussion of how a battery works is beyond the scope of this blog post, but it is important to understand the basics in order to understand the resources needed for making batteries. At this time, most BEVs use lithium (Li) ion batteries consisting of three major parts including a cathode and an anode which are separated by an electrolyte. When charging, Li ions transfer from the cathode to the anode and this process is reversed during discharging. The most common cathodes used today are lithium manganese oxide (LMO), lithium iron phosphate (LFP), lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC) and lithium nickel cobalt aluminum (NCA). Also, the most common anode used is graphite, a crystalline form of carbon arranged in a hexagonal structure.

“If the world moves to a transportation market dominated by BEVs, the big change is that the key resource will shift from an energy source to the metal resources needed to make batteries.”

The resources needed for a BEV depends on the choice for the cathode and anode, but driving range is an important consideration. At this time, BEVs come in a variety of ranges from a low end of less than 100 miles to about 300 miles, depending on the size of the battery system. If the BEV is to become more than a commuter vehicle, 300 miles seems like a minimum value for road trips and this will require a battery with an energy content of around 100 kWh.

The types and compositions of batteries for BEVs is still in flux but typically batteries use 160 g Li/kWh, so a 100-kWh battery would use about 16 kg Li. On this basis, some of the other metals can be estimated by composition. For one version of the NMC battery, NMC333, the battery would need 45 kg nickel (Ni), 42 kg manganese (Mn), and 45 kg cobalt (Co). Co has some issues, to be discussed later, so there is another version of this battery, NMC532, with a lower Co content. For this composition, Ni is now 68 kg, Mn is 38 kg, and Co is 27 kg. Similarly, for a typical composition of the NCA battery, the number of metals would be 114 kg of Ni, 16 kg of Co, and about 3 kg of aluminum (Al). For the anode, the amount of graphite will be more than 60 kg for a 100-kWh battery pack.

Which countries are rich in resources for batteries?Which countries are rich in these metal resources? First, it is important to note that there are both “proven reserves,” reserves that can be economically mined, and “probable reserves,” reserves which are less likely to be recovered. Also, current production may not necessarily match a country’s standing with proven reserves. For this blog post, proven reserves will be used based on United States Geological Survey (USGS) data. When it comes to Li, Chile, China, Argentina, and Australia control most of the proven reserves. Chile, Argentina and Bolivia (which has probable reserves) make up the so-called Lithium Triangle, an area in the Andes bordering these three countries. Co is controlled by the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Australia, and the DRC has nearly 50% of worldwide reserves. Unfortunately, much of the Co comes from artisanal mining, and this mining is done in hazardous conditions and even with child labor. Mn is mostly found in South Africa, Ukraine, and Australia and these three countries control 70% of the reserves. And for Ni, almost 50% is controlled by Australia, New Caledonia, Cuba, and Indonesia with Australia at 24% of worldwide reserves. Finally, China is by far the biggest producer of graphite for the anode, producing around two-thirds of worldwide supplies.

Therefore, if the world shifts to a transportation fleet of BEVs, the control of critical resources will change from OPEC countries to countries in South America as well as China, Australia, and the DRC. This could be an economic opportunity for these countries, but external exploitation, social issues, and environmental concerns will have to be managed to reap the full benefits of production.

Featured image by Ather Energy on Unsplash. Public domain.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers